Submitted:

24 January 2023

Posted:

25 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and skin lesion samples

2.2. Immunostaining for Mφ characterization and Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethical aspects

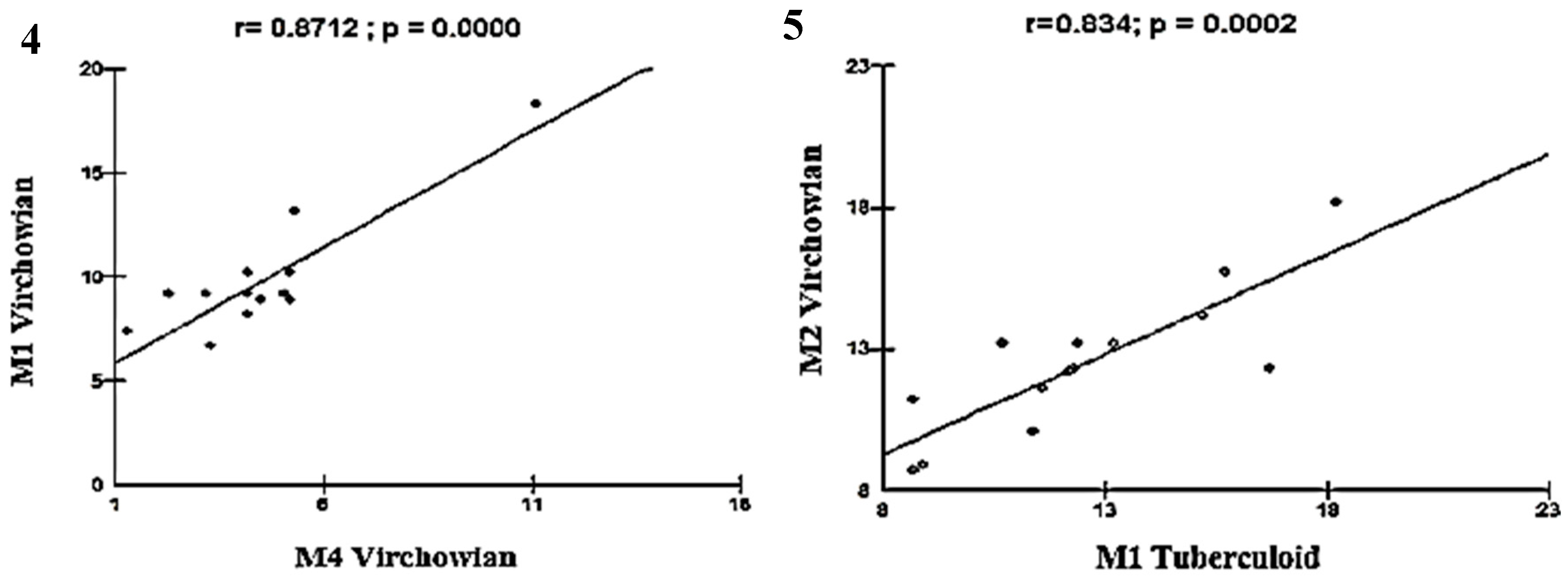

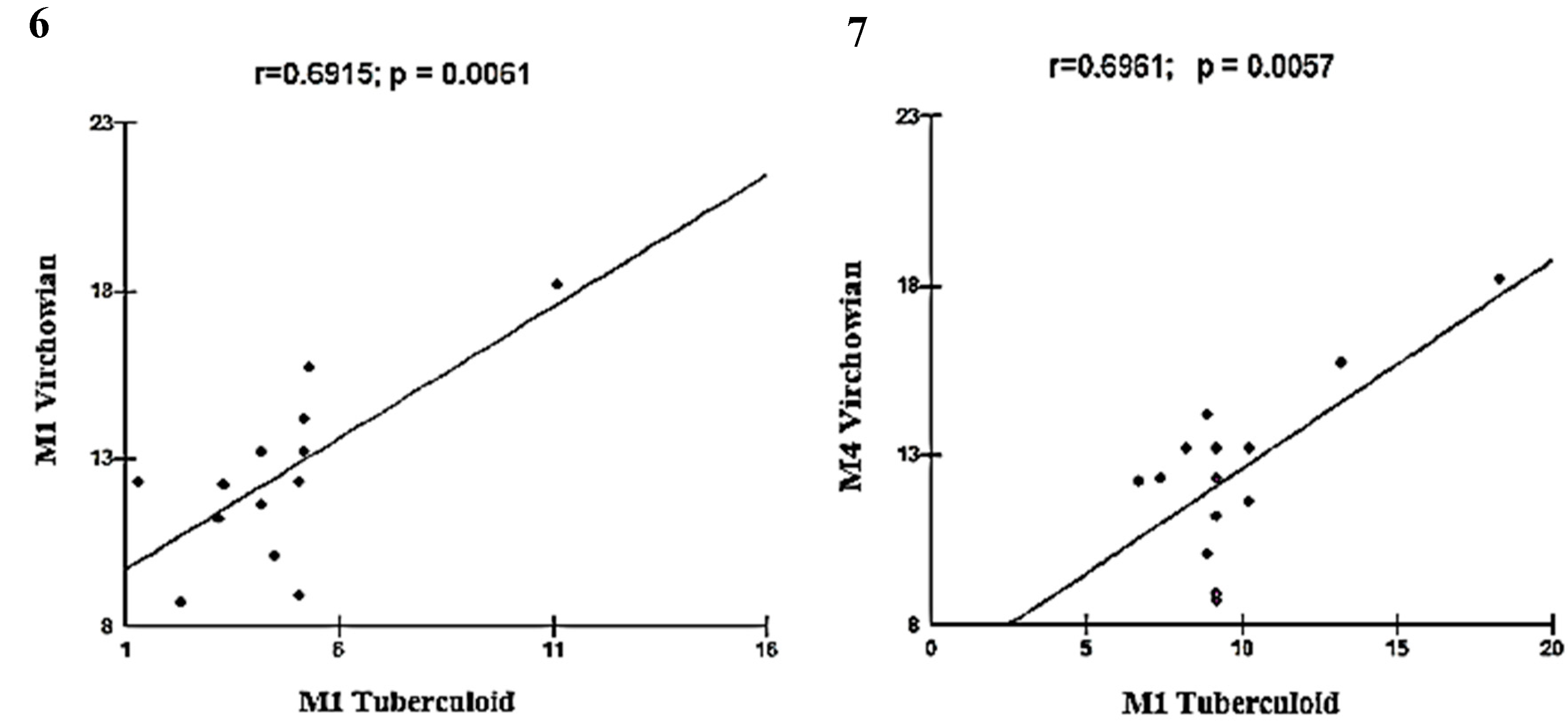

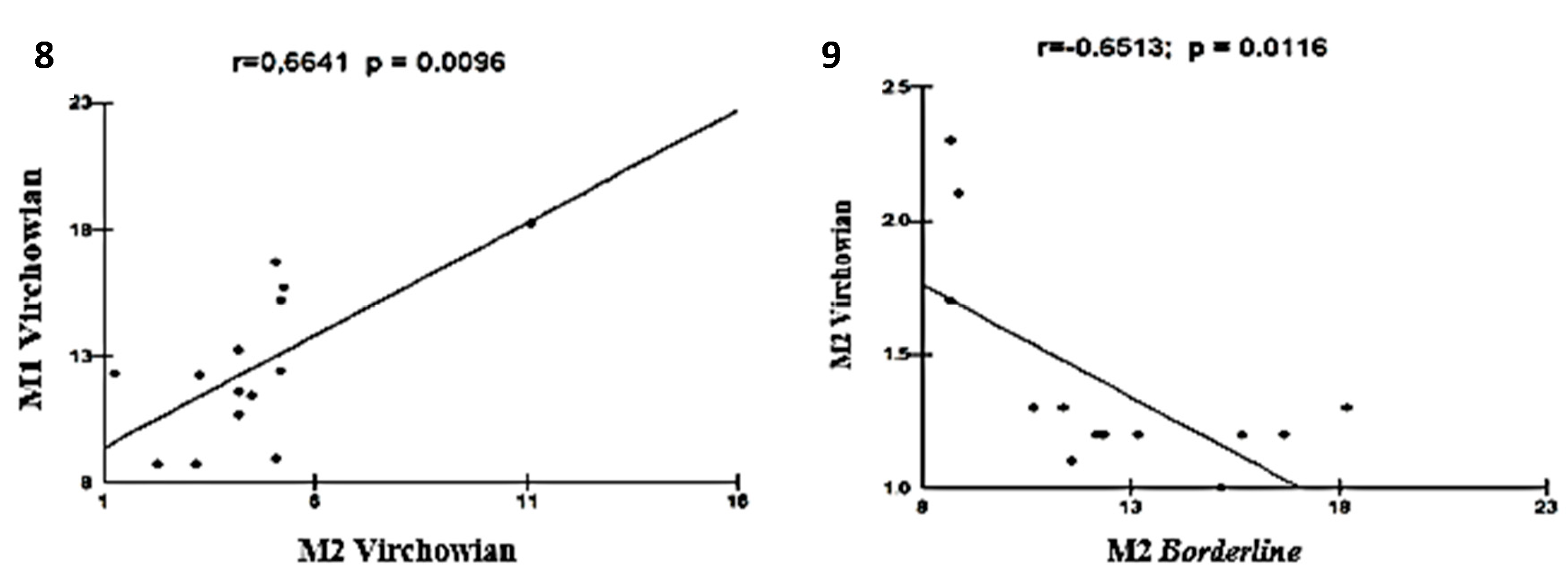

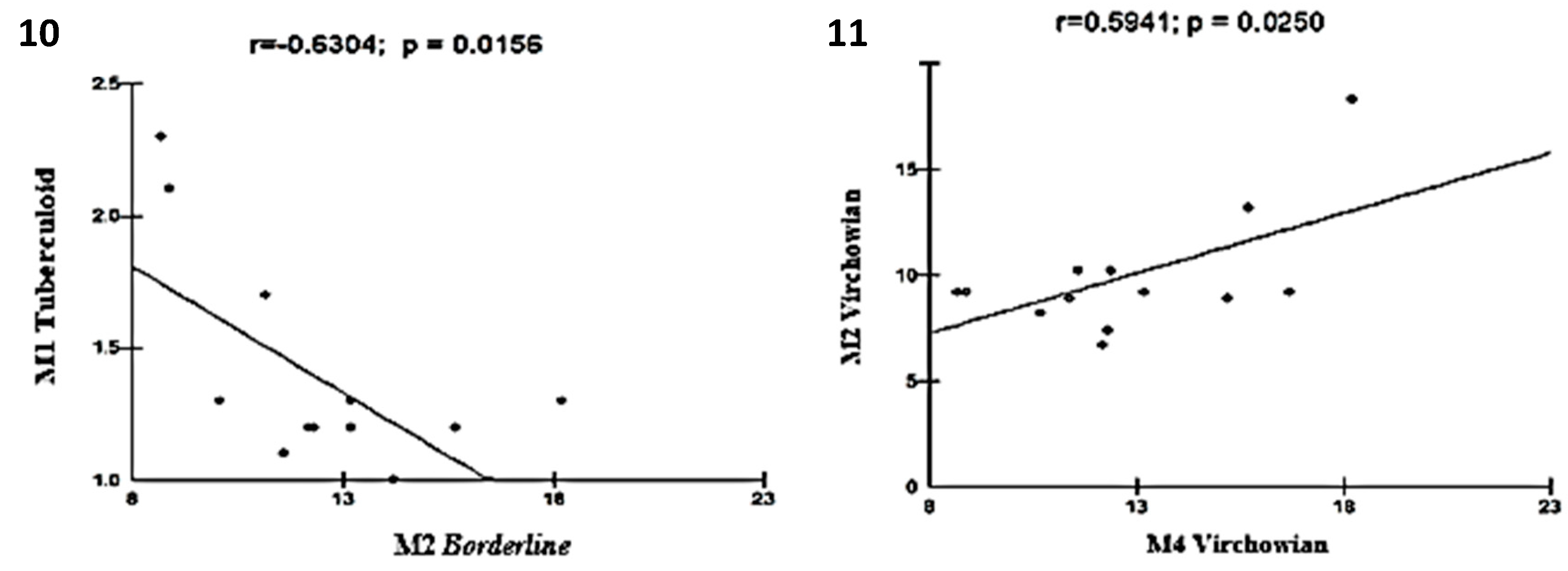

3. Results

|

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lastória JC, Abreu MAMM. (2014). Etiopathogenic aspects – Part 1. Brazilian Annals of Dermatology. 89 (2): 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Woods JA, Lu Q, Cedddia M. (2000). Exercise-induced modulation of macrophage function. Immunology and Cell Biology. 78: 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Kedzierska KE, Crowe SM. (2014). The role of Monocytes and Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 9: 1893-1903. [CrossRef]

- Quaresma JAS. (2019). Organization of the Skin Immune System and Compartmentalized Immune Responses in Infectious Diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 32: e00034-18. [CrossRef]

- Mège JL, Mehraj V, Capo C. (2011). Macrophage polarization and bacterial infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 24: 230–234. . [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Brumell JH. (2014). Bacteria–autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 12 (2): 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Liehl P, Zuzarte-Luis, V.; Mota MM. (2015). Unveiling the pathogen behind the vacuole. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 13 (9): 589–598. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C. (2014). Secretory products of macrophages: twenty-five years on. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 10: 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Solinas G, Germano G, Montovani A. (2009). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major player of cancer-related inflammation. Journal of Leukocyte biology. 86: 1065-1073. [CrossRef]

- De Sousa JR, Da Costa Vasconcelos PF, Quaresma JAS. (2019). Functional aspects, phenotypic heterogeneity, and tissue immune response of macrophages in infectious diseases. Infect Drug Resist. 12: 2589-2611. [CrossRef]

- Quaresma JAS, Lima LW, Fuzii HT, Libonati RM, Pagliari C, Duarte MI. (2010). Immunohistochemical evaluation of macrophage activity and its relationship with apoptotic cell death in the polar forms of leprosy. Microb Pathog. Oct;49(4):135-40. [CrossRef]

- De Sousa JR, De Sousa RP, Aarão TL, Dias LB JR, Carneiro FR, Fuzii HT, Quaresma JAS. (2016). In situ expression of M2 macrophage subpopulation in leprosy skin lesions. Acta Trop. May; 157:108-14. [CrossRef]

- De Sousa JR, Sotto MN, Quaresma JAS. (2017). Leprosy As a Complex Infection: Breakdown of the Th1 and Th2 Immune Paradigm in the Immunopathogenesis of the Disease. Front Immunol. Nov 28; 8:1635. [CrossRef]

- Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, et al. (2014). Macrophage Activation and Polarization: Nomenclature and Experimental Guidelines. Immunity. 41: 14-20. [CrossRef]

- Hirai KE, De Sousa JR, Silva LM., Junior LBD, Furlaneto IP, et al. (2018). Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Markers and Their Possible Implications in leprosy's Pathogenesis. Dis Markers. 16: 7067961. [CrossRef]

- Jablonski KA, Amici SA, Webb LM, Ruiz-Rosado JDED, Popovich PG, et al. (2015). Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS One. 23;10 (12): e0145342. [CrossRef]

- Biagioli M, Carino A, Cipriani S, Francisci D, Marchianò S, et al. (2017). The Bile Acid Receptor GPBAR1 Regulates the M1/M2 Phenotype of Intestinal Macrophages and Activation of GPBAR1 Rescues Mice from Murine Colitis. J Immunol. 15:199 (2): 718-733. [CrossRef]

- Santos DO, Miranda A, Suffys P, Rodrigues CR, Bourguignon SC, et al. (2007). Current Understanding of the Role of Dendritic Cells and Their Co-Stimulatory Molecules in Generating Efficient T Cell Responses in Lepromatous leprosy. Current Immunology Reviews. 3 (1): 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Okwor I, Uzonna JE. (2016). Pathways leading to interleukin-12 production and protective immunity in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Cell Immunol. 309: 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Von Stebut E, Belkaid Y, Jakob T, Sacks DL, Udey MC. (1988). Uptake of Leishmania major amastigotes results in activation and interleukin 12 release from murine skin-derived dendritic cells: implications for the initiation of anti-Leishmania immunity. J Exp Med. 188 (8): 1547–1552. [CrossRef]

- Von Stebut E, Ehrchen JM, Belkaid Y, Kostka SL, Molle K, et al. (2003). Interleukin 1alpha promotes Th1 differentiation and inhibits disease progression in Leishmania major-susceptible BALB/c mice. J Exp Med. 198 (2): 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Park AY, Hondowicz BD, Scott P. (2000). IL-12 is required to maintain a Th1 response during Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 165 (2): 896–902. [CrossRef]

- Stobie L, Gurunathan S, Prussin C, Sacks DL, Glaichenhaus N, et al. (2000). The role of antigen and IL-12 in sustaining Th1 memory cells in vivo: IL-12 is required to maintain memory/effector Th1 cells sufficient to mediate protection to an infectious parasite challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sei USA. 97 (15): 8427–8432. [CrossRef]

- Park AY, Hondowicz B, Kopf M, Scott P. (2002). The role of IL-12 in maintaining resistance to Leishmania major. J Immunol. 168 (11): 5771–5777. [CrossRef]

- Novoselov VV, Sazonova MA, Ivanova EA, Orekhov AN. (2015). Study of the activated macrophage transcriptome. Exp Mol Pathol. 99: 575–580. [CrossRef]

- Sica A, Erreni M, Allavena P, Porta C. (2015). Macrophage polarization in pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 72: 4111–4126. [CrossRef]

- Tomioka H, Tatano Y, Maw WW, Sano C, Kanehiro Y, et al. (2012). Characteristics of suppressor macrophages induced by mycobacterial and protozoal infections in relation to alternatively activated M2 macrophages. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012: 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y, Khan FA, Pandupuspitasari NS, Zhang S. (2017). Immune evasion strategies of pathogens in macrophages: the potential for limiting pathogen transmission. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 21:21–40. [CrossRef]

- Borlace GN, Jones HF, Keep SJ, Butler RN, Brooks DA. (2011). Helicobacter pylori phagosome maturation in primary human macrophages. Gut Pathog. 3: 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, SM. (2021). Evaluation of macrophage polarization in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori and in relation to host susceptibility. Thesis (Doctorate in Health Sciences) - São Luís, Federal University of Maranhão, 2021. 171p. Available online: https://tedebc.ufma.br/jspui/bitstream/tede/3187/2/SELMA-MALUF.pdf.

- Asim M, Chaturvedi R, Hoge S, Lewis ND, Singh K, et al. (2010). Helicobacter pylori induces ERK-dependent formation of a phospho-c-Fos c-Jun activator protein-1 complex that causes apoptosis in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 285:20343–20357. [CrossRef]

- Algood HMS, Cover TL. (2006). Helicobacter pylori persistence: An overview of interactions between H. pylori and host immune defenses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 19 (4): 597–613. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto Y, Blanchard TG, Drakes ML, Basu M, Redline RW, et al. (2005). Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and resolution of gastritis in the gastric mucosa of IL-10-deficient mice. Helicobacter. 10 (5):407-15. [CrossRef]

- Quaresma JAS, Almeida FA, Aarão TLS, Miranda Soares LPMA, Nunes IMM, et al. (2012). Transforming growth factor β and apoptosis in leprosy skin lesions: possible relationship with the control of the tissue immune response in the Mycobacterium leprae infection. Microbes and Infection. 14 (9): 696–701. [CrossRef]

- Aarão TLS, Esteves NR, Esteves N, Soares LP, Pinto DDAS, et al. (2014). Relationship between growth factors and its implication in the pathogenesis of leprosy. Microbial Pathogenesis. 77: 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Moura DF, Mattos KA, Amadeu TP, Andrade PR, Sales JS, et al. (2012). CD163 favors Mycobacterium leprae survival and persistence by promoting anti-inflammatory pathways in lepromatous macrophages. European Journal of Immunology. 42 (11): 2925–2936. [CrossRef]

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, Van Meijgaarden KE, Bekele Y, Zewdie M, et al. (2014). T-Cell Regulation in Lepromatous Leprosy. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (4): 2773. [CrossRef]

- Cunha LD, Yang M, Carter R, Guy C, Harris L, et al. (2018). LC3-Associated Phagocytosis in Myeloid Cells Promotes Tumor Immune Tolerance. Cell. 4;175(2):429-441.e16. [CrossRef]

- Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM. (2009). Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 5;458 (7234):78-82, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Dejani NN, Orlando AB, Niño VE, Penteado LA, Verdana FF, et al. (2018). A.I. Intestinal host defense outcome is dictated by PGE2 production during efferocytosis of infected cells. PNAS. 115 (36): E8469–E8478. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio AR. (2005). Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis: interaction of mannose-binding lectin with surface glycoconjugates and complement activation. An antibody-independent defence mechanism. Parasite Immunol. 27: 333-340. [CrossRef]

- De Miranda Santos IKF, Costa CHN, Krieger H, Feitosa MF, Zurakowski D, et al. (2001). Mannan-binding lectin enhances susceptibility to visceral leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun, 69: 5212-5215. [CrossRef]

- Carmo RF, Neves JRL, Oliveira PRS, Vasconcelos LRS, Souza CDF. (2021). The role of Mannose-binding lectin in leprosy: A systematic review. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 93. [CrossRef]

- Forestier CL, Gao Q, Boons GJ. (2014). Leishmania lipophosphogly can: how to establish structure-activity relationships for this highly complex and multifunctional glycoconjugate? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 4: 193. [CrossRef]

- Brandonisio O, Panaro MA, Marzio R, Marangi A, Faliero SM, et al. (1994). Impairment of the human fhagocyte oxidative responses cause by Leishmania lipophosphoglycan (LPG): in vitro studies. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 8 (1): 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Sales JS, Lara FA, Amadeu TP, Fulco TO, Nery JAC, et al. (2011). The role of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase in lepromatous leprosy immunosuppression. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 165 (2): 251–263. Available online: https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/bitstream/icict/44255/2/mylena_pereira_ioc_mest_2020.pdf.

- Mendonça VM, Costa RD, Melo GEBA, Antunes CM, Teixeira AL. (2008). Leprosy immunology. Review article. An. Bras. Dermatol. 83 (4). [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar SV, Patil SB, Shetty VP. (2021). Neuropathies of leprosy. J Neurol Sci. 15;420: 117288. [CrossRef]

- Save MP, Shetty VP, Shetty KT, Antia NH. (2004). Alterations in neurofilament protein(s) in human leprous nerves: morphology, immunohistochemistry and Western immunoblot correlative study. Neurophatology and Applied Neurobiolog. 30 (6): 635-650. [CrossRef]

- Shetty VP, Antia NH, Jacobs JM. (1988). The pathology of early leprous neuropathy. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 88 (1–3): 115-131. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs JM, Shetty VP, Antia NH. (1987). Teased fibre studies in leprous neuropathy. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 79 (3): 301-313. [CrossRef]

- Salina ACG. (2020). Activation of M1/M2 macrophages by epherocytosis of infected apoptotic cells. Thesis (Doctorate in Science) – Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, 2020.155p. https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/17/17147/tde-25082020-090635/publico/ANACAROLINAGUERTASALINAco.pdf.

- Quaresma JAS, Lima LW, Fuzii, HT, Libonati RMF, Pagliari C, et al. (2010). Immunohistochemical evaluation of macrophage activity and its relationship with apoptotic cell death in the polar forms of leprosy. Microbial Pathogenesis. 49 (4): 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Moraco AH, Kornfeld H. (2014). Cell death and autophagy in tuberculosis. Seminars in Immunology. 26: 497-511. [CrossRef]

- Siva LM, De Sousa JR, Hirai KE, Dias LBJR, Furlaneto IP, et al. (201). The Resist. 12 (11):.2231-2240. [CrossRef]

- Fulco TO, Andrade PR, Barbosa MGM, Pinto TG, Ferreira PF, et al. (2014). Effect of apoptotic cell recognition on macrophage polarization and mycobacterial persistence. Infection and Immunity, 82: (9) 3968–78. [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov NG, Kornienko VY, Karagodin VP, Orekhov AN. (2015). Macrophage activation in atherosclerosis. Message 1: Activation of macrophages normally and in atherosclerotic lesions. Patol Fiziol Eksp (3):128-31 Russian. [PubMed]

- Luo F, Sun X, Qu Z, Zhang X. (2016). Salmonella typhimurium-induced M1 macrophage polarization is dependent on the bacterial O antigen. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 32: 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Gleissner CA. (2012). Macrophage phenotype modulation by CXCL4 in atherosclerosis. Front Physiol. 3 (1). [CrossRef]

- Boyle JJ, Johns M, Lo J, Chiodini A, Ambrose N, et al. (2011). Heme Induces Heme Oxygenase 1 via Nrf2 Role in the Homeostatic Macrophage Response to Intraplaque Hemorrhage. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 31: 2685–2691. [CrossRef]

- Colin S, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Staels B. (2014). Macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerosis. ImmunologyReviews, 262: 1600-065X (Electronic): 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Gleissner CA, Shaked I, Little KM, Ley K. (2010). CXC chemokine ligand 4 induces a unique transcriptome in monocyte-derived macrophages. J Immunol. 84: 4810–4818. [CrossRef]

- Reibel F, Cambau E, Aubry A. (2015). Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of leprosy. Med Mal Infect. 45 (9): 383-93. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca ABL, Simon MV, Cazzaniga RA, Moura TR, Almeida RP, et al. (2017). The influence of innate and adaptative immune responses on the differential clinical outcomes of leprosy. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 6 (1): 5. [CrossRef]

- Elamin AA, Stehr M, Singh M. (2012). Lipid Droplets and Mycobacterium leprae Infection. Journal of Pathogens. 2012: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kaur G, Kaur J. (2017). Multifaceted role of lipids in Mycobacterium leprae. Future Microbiol. 12: 315-335. [CrossRef]

- Mattos KA, Lara FA, Oliveira VG, Rodrigues LS, D'avila H, et al. (2011). Modulation of lipid droplets by Mycobacterium leprae in Schwann cells: a putative mechanism for host lipid acquisition and bacterial survival in phagosomes. Cell Microbiol. 13 (2): 259–273. [CrossRef]

- Erbel C, Tyka M, Helmes CM, Akhavanpoor M, Rupp G, et al. (2015). CXCL4-induced plaque macrophages can be specifically identified by co-expression of MMP7+S100A8+ in vitro and in vivo. Innate Immun. 21: 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Rojas J, Salazar J, Martínez MS, Palmar J, Bautista J, et al. (2015). Macrophage Heterogeneity and Plasticity: Impact of Macrophage Biomarkers on Atherosclerosis. Scientifica (Cairo). 2015: 851252. [CrossRef]

- Brizzi MF, Tarone G, Defilippi P. (2012). Extracellular matrix, integrins, and growth factors as tailors of the stem cell niche. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol..24: 645–651. [CrossRef]

- Mcmahan RS, Birkland TP, Smigiel KS, Vandivort TC, Rohani MG, et al. (2016). Stromelysin-2 (MMP10) Moderates Inflammation by Controlling Macrophage Activation. J Immunol. 1;197 (3): 899-909. [CrossRef]

- Koller FL, Dozier EA, Nam KT, Swee M, Birkland TP, et al. (2012). Lack of MMP10 exacerbates experimental colitis and promotes development of inflammation-associated colonic dysplasia. Lab Invest. 92 (12): 1749-59. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Steen PE, Husson SJ, Proost P, Van-Damme J, Opdenakker G. (2003). Carboxyterminal cleavage of the chemokines MIG and IP-10 by gelatinase B and neutrophil collagenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 24;310 (3): 889-96. [CrossRef]

- Manicone AM, Mcguire JK. (2008). Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19: 34–41. [CrossRef]

- Dalby E, Christensen SM, Wang JY, Hamidzadeh K, Chandrasekaran P, et al.(2020). Immune Complex- Driven Generation of Human Macrophages with Anti-Inflammatory and Growth-Promoting Activity Journal of immunology. 205 (1): 102-112. [CrossRef]

- Sousa JR, Dias F, Neto L, Sotto MN, Quaresma, JAS. (2018). Immunohistochemical characterization of the M4 macrophage population in leprosy skin lesions. BMC Infect Dis. 18: 576. [CrossRef]

- Chiu YH, Ritchlin CT. (2016). DC-STAMP: a key regulator in osteoclast differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 231: 2402–2407. [CrossRef]

- Zeng XX, Chu TJ, Yuan JY, Zhang W, Du YM, et al. (2015). Transmembrane 7 superfamily member 4 regulates cell cycle progression in breast cancer cells. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 19: 4353–4361. [PubMed]

- Sawatani Y, Miyamoto T, Nagai S, Maruya M, Imai J, et al. (2008). The role of DC-STAMP in maintenance of immune tolerance through regulation of dendritic cell function. Int. Immunol. 20: 1259–1268. [CrossRef]

- Sanecka A, Ansems M, Prosser AC, Danielski K, Warner K, et al. (2011). DC-STAMP knock-down deregulates cytokine production and T-cell stimulatory capacity of LPS-matured dendritic cells. BMC Immunol. 12: 57. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso CC, Pereira AC, De Sales Marques C, Moraes MO. (2011). Leprosy susceptibility: genetic variations regulate innate and adaptive immunity, and disease outcome. Future Microbiol. May;6(5):533-49. [CrossRef]

- Marin A, Huss CV, Corbett J, Kim S, Mohl J, et al. (2021). Human macrophage polarization in the response to Mycobacterium leprae genomic DNA. Current Research in Microbial Sciences. 2: 10001. [CrossRef]

- Teles RM, Graeber TG, Kruitzik SR, Montoya D, Schenk M, et al. (2013). Type I interferon suppresses type II interferon-triggered human anti-mycobacterial responses. Sciense. 3 (339): 1448–1454. [CrossRef]

- Cervantes JL, Oak E, Garcia J, Liu H, Lorenzini PA, et al. (2019). Vitamin D modulates human macrophage response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA. Tuberculosis (Edinb). May116S:S131-S137. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).