Results and Discussion

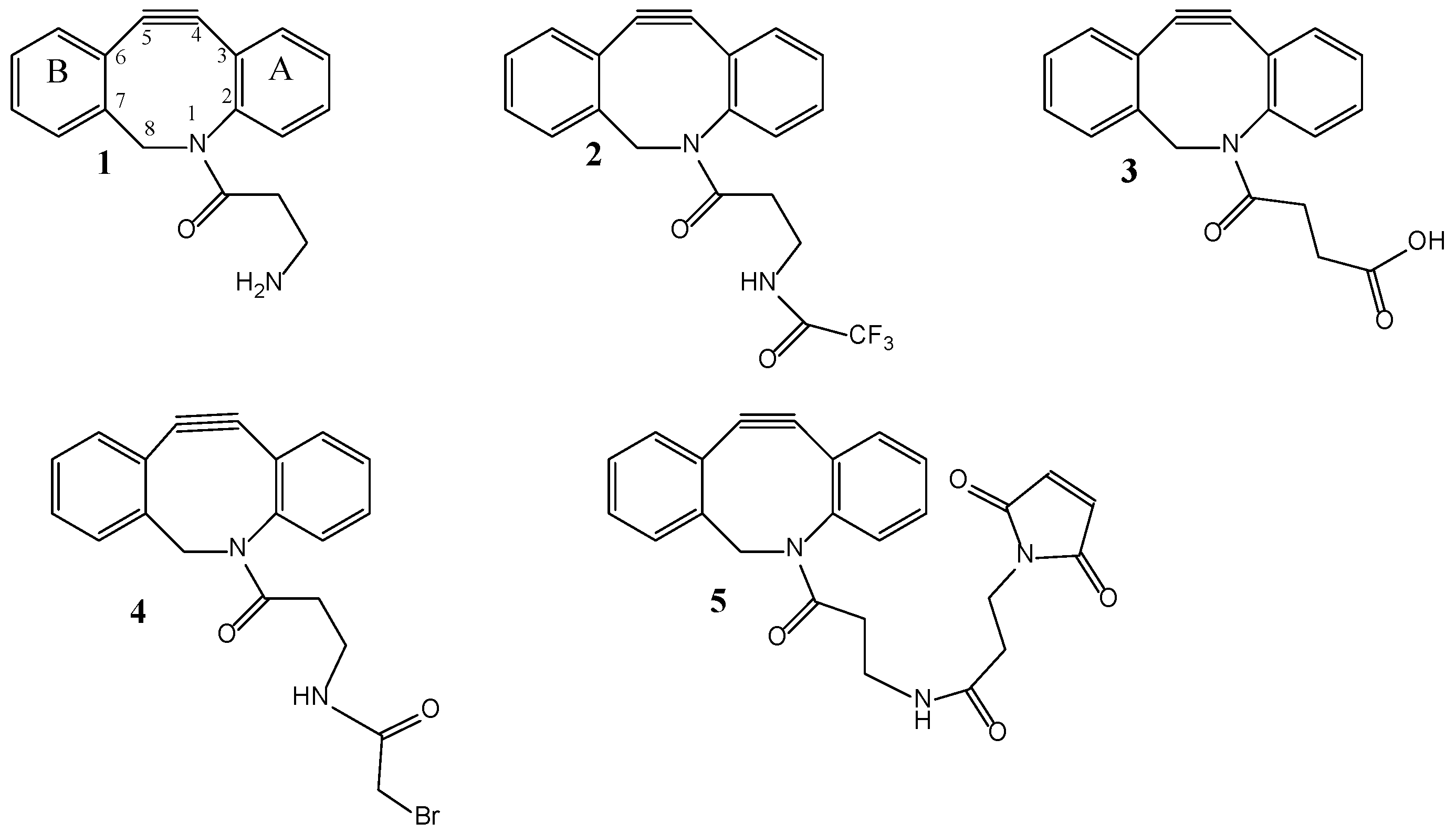

Here we report a detailed structural and dynamic study of

1-5 DiBenzoCyclooctynes (

DBC,

Scheme 1) and of their triazole adducts with simple azides (

Scheme 2).

For the exploratory survey of key experimental structural features of cyclooctynes we employed compound 2 as the test substrate.

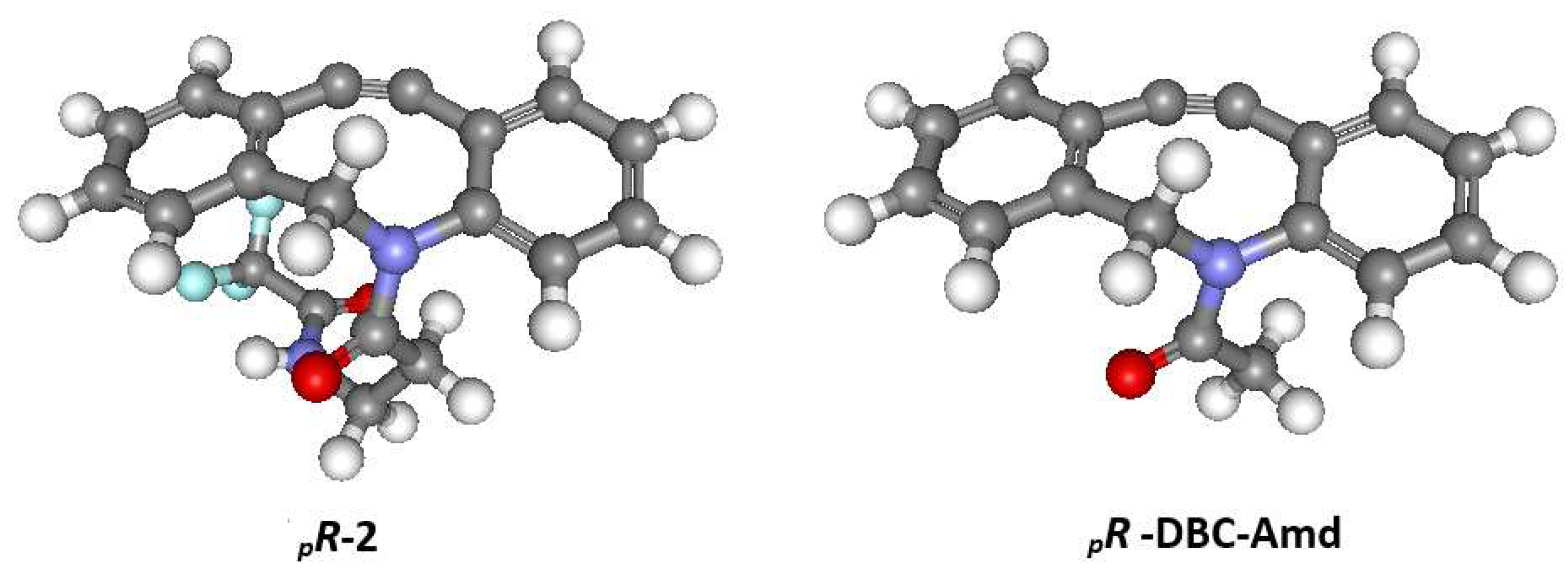

Conformational analysis of

2, performed at the molecular mechanic level of theory with the MMFF94 force field [

11], showed that this one is a conformationally rigid molecule in its tricyclic framework including the amide group (hereafter denoted with the acronim

DBC-Amd), with the carbonyl oxygen of this latter one projected above the phenyl ring A and pointing towards one of the hydrogens on C8 in 99.7% of the populated conformations, inside an energetic gap of 3.6 kcal/mol. In particular, the cyclooctyne core adopts a chair conformation, with the alkyne C4, C5 carbon atoms and the ring nitrogen atom almost coplanar with phenyl ring A, whereas C8 and ring B lye below the A ring plane (

Figure 1).

The angle between the planes containing the two phenyl rings A and B is about 16°. Due to non-planarity of the

DBC-Amd framework and to its asymmetric substitution pattern,

1-5 are devoid of any reflection type symmetry element and are thus chiral. It is anticipated that enantiomer interconversion can occur in these molecules by a ring flip process. Thus, in order to theoretically analyze the stereodynamic pathways for enantiomer interconversion (enantiomerization) of the synthesized

1-5 dibenzocyclooctynes, on the simplified structure common to all these ones (i.e. on the

DBC-Amd scaffold), we performed DFT optimization of both ground and transition states related to its ring flipping pathway, carried out at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) [

12] level of theory. Indeed, it is reasonable to expect that the amide arms linked to the

DBC-Amd framework in derivatives

1-5 cannot significantly influence their stereochemical lability. The estimated enantiomerization energy barrier, ΔE

en#, is of 24.1 kcal/mol, to which correspond a half-life time around 58 h at room temperature. Based on this information, which indicates a rather large enantiomerization barrier, we were able to plan the experimental conditions to physically separate the enantiomers of

1-5. Accordingly, the enantiomers of

1-5 were easily resolved by HPLC using the Pirkle-type (

R,

R)-Whelk-O1

13 chiral stationary phase. Elution with hexane/CH2Cl2/MeOH 80:20:2 gave two nicely resolved peaks corresponding to the (

pR)- and (

pS)-enantiomers of

2, with elution times of 8.0 and 11.5 min, respectively. When monitored by CD detection at 290 nm, bisignate peaks of equal area were observed, as expected for a racemate.

The large enantioselectivity values (α = 1.80-x.xx, Supporting Information, pages 2–4) obtained at analytical level on a 250 · 4.6 mm column, and the good solubility of 1-5 in the eluent allowed for a simple scale up at preparative levels on the 250 × 10 column. Enantioselectivity and peak shapes remained unchanged even at high column loading (15 mg per run) thus enabling very efficient fraction collection in terms of speed of separation, enantiomeric purity and overall yield. As a result, about 20 mg of each enantiomer of 1-5 were obtained after iterative HPLC separations and solvent removal from the pooled fractions. The individual enantiomers collected by chiral HPLC showed enantiomeric excesses greater than 99.5%, as determined by analytical HPLC.

With discrete amounts of the single enantiomers of 1-5, we performed thermal racemization experiments to evaluate their stereochemical stabilities.

Thermal racemization of the enantiomers of 1-5 in the HPLC eluent at 50 °C was monitored by HPLC following the decay of the enantiomeric excess over time, and racemization rate constants value between krac = 0.0033 min−1 and krac = 0.0087 min−1 (T = 50 °C) were determined (Supporting Information). A statistical transmission coefficient γ = 0.5 was used in the calculation of the free energy barrier ΔG⧧ from the rate constant of the process. This gave values of racemization activation energies between 24.82 ± 0.1 kcal/mol and 24.20 ± 0.1 kcal/mol at 50 °C and are consistent with the computational study.

These barriers translate into half-lives between 1.5 and 4 days at 25 °C, thus indicating that 1-5 are atropisomeric at room temperature.

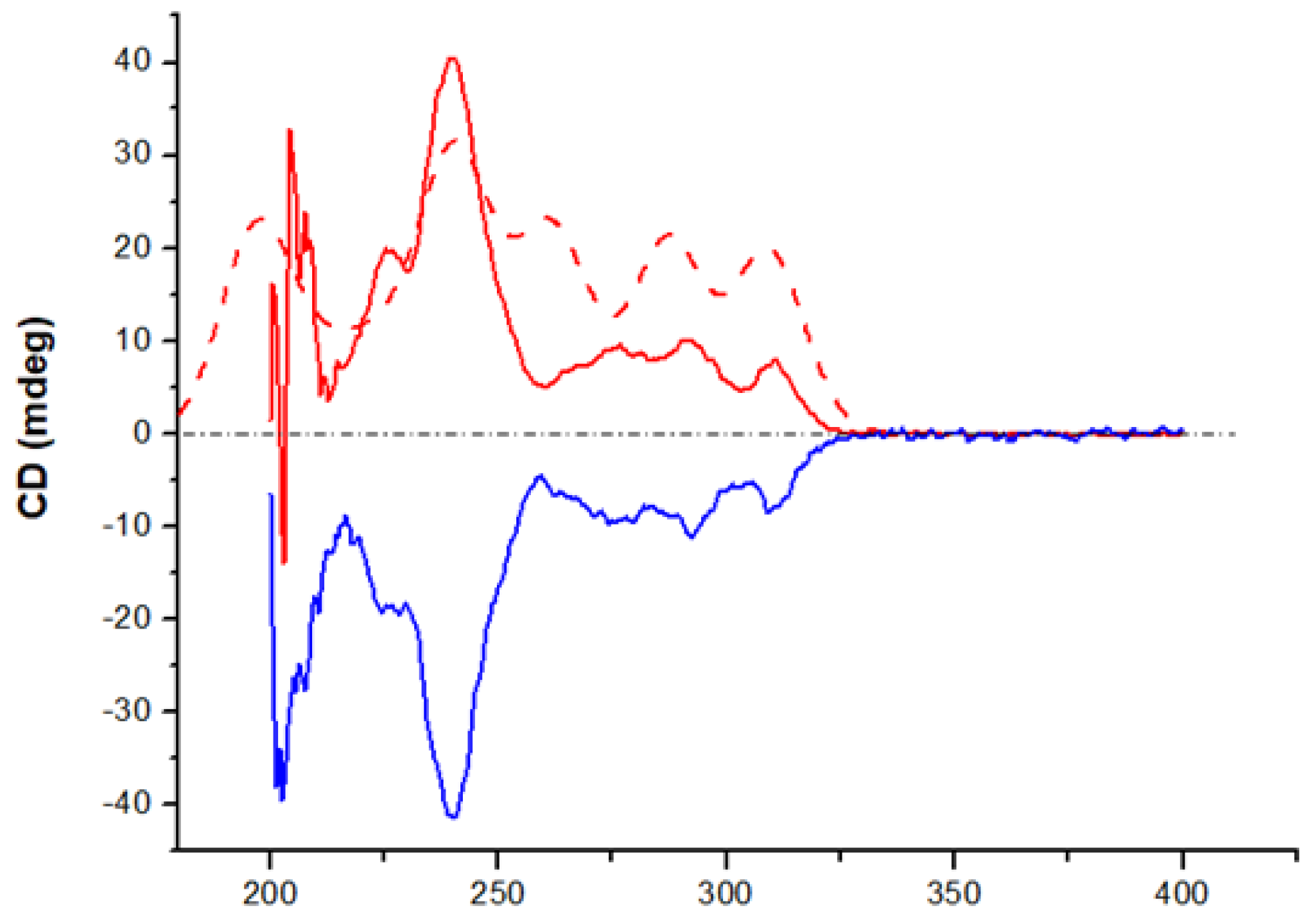

The pure enantiomers of

1-5 were characterized by polarimetry and electronic circular dichroism spectroscopy. The first eluted enantiomers of

1-5 give positive rotation at the sodium D line in chloroform solution, e.g (+)-

2: [α]

30D = +319. Its circular dichroism spectrum (methanol solution) exhibits positive bands at 233 nm and 270-320 nm, the last showing vibronic signature. The second eluted enantiomer gives a mirror image CD spectrum (

Figure 2) and negative rotation at the sodium D line in chloroform solution, (-)-

2: [α]

30D = −319.

The electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra of 1-5 are very similar, showing the same pattern of positive bands for the first eluted enantiomers having positive optical rotations at the sodium D line (see Supporting Information).

Starting from these results, the absolute configuration (AC) of

2 was determined by comparing the experimental ECD spectra of its two chromatographically resolved enantiomers with the one assessed for the

pRoptical isomer of the above quoted

DBC-Amd framework, a methodology used previously in determining the ACs of chiral-chromatography-resolved enantiopure molecules

14. This was carried out by submitting the

pR-

DBC-Amd structure to new optimization and, next, to frequencies calculation at a suitable density functional level of theory (DFT), which led to the computed ECD spectrum shown in

Figure 2.

The predicted ECD spectrum of

pR-

DBC-Amd is in excellent qualitative agreement with the experimental ECD spectrum of

(+)-2, leading to the conclusion that the absolute configuration of this enantiomer (and therefore, also of the (+)-enantiomers of the other

DBC derivatives) is unambiguously

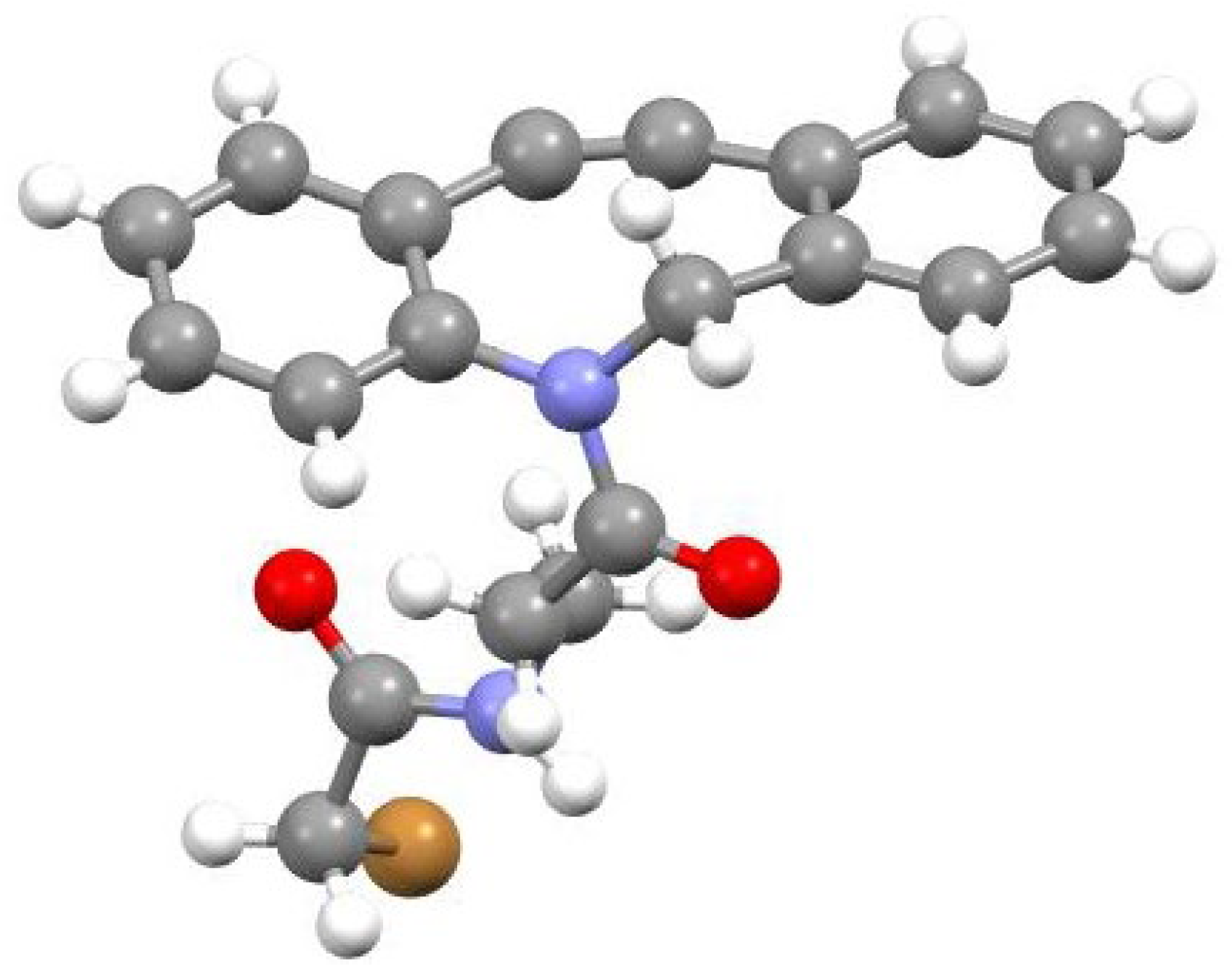

(+)-pR. Further support for the reliability of the DFT calculations for

2 is provided by the X-ray structure of

4. Crystals of the second eluted enantiomer (-)

4, [α]

25D = −319, suitable for X-ray analysis, were grown from a hexane/CH

2Cl

2 solution. The 2-bromoacetyl group was chosen to facilitate the AC assignment by the X-ray diffraction analysis. The molecular structure revealed by the X-ray diffraction study is reported in

Figure 3. The general geometrical features of (-)-

4 are very similar to those obtained by calculation for

2. The second eluted, (-)-

4, exhibits a slightly distorted chair conformation of the eight-membered ring, with the nitrogen and C4 and C5 atoms almost coplanar with the phenyl ring and the carbonyl oxygen projected away from the phenyl ring and pointing towards one of the H atoms of the C8 methylene unit (amide adopting the

E configuration). The absolute configuration is unambiguously determined as

(-)-pS, in agreement with the AC determined by comparison of experimental and calculated ECD spectra (Figure X).

Having addressed the general structural properties of cyclooctynes 1-5 and having established their atropisomeric nature at room temperature, we were in a position to investigate the structural properties of the corresponding triazole obtained by reaction with simple azides.

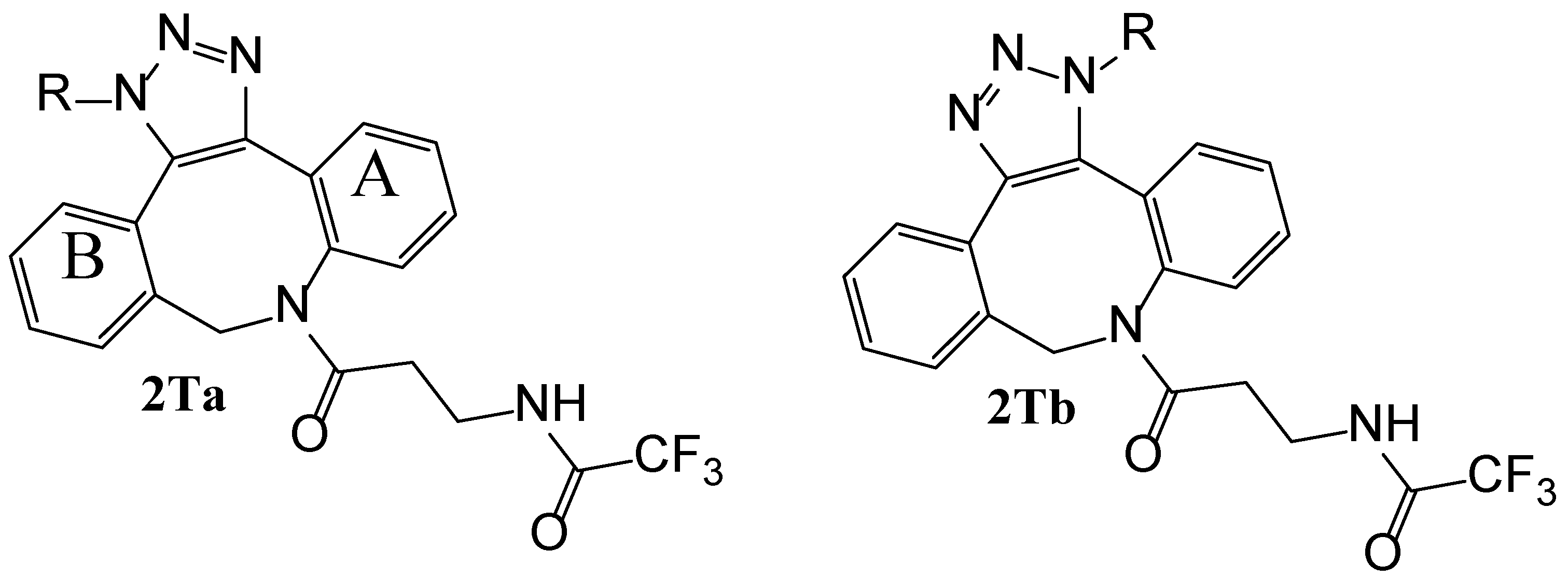

Reaction of cyclooctynes 2 with either phenyl (Ph) or benzyl (Bz) azides proceeds smoothly to yield the two regioisomeric triazoles 2Ta (2TaPh with R=Ph and 2TaBz with R=Bz) and 2Tb (2TbPh with R=Ph and 2TbBz with R=Bz) (Scheme 2).

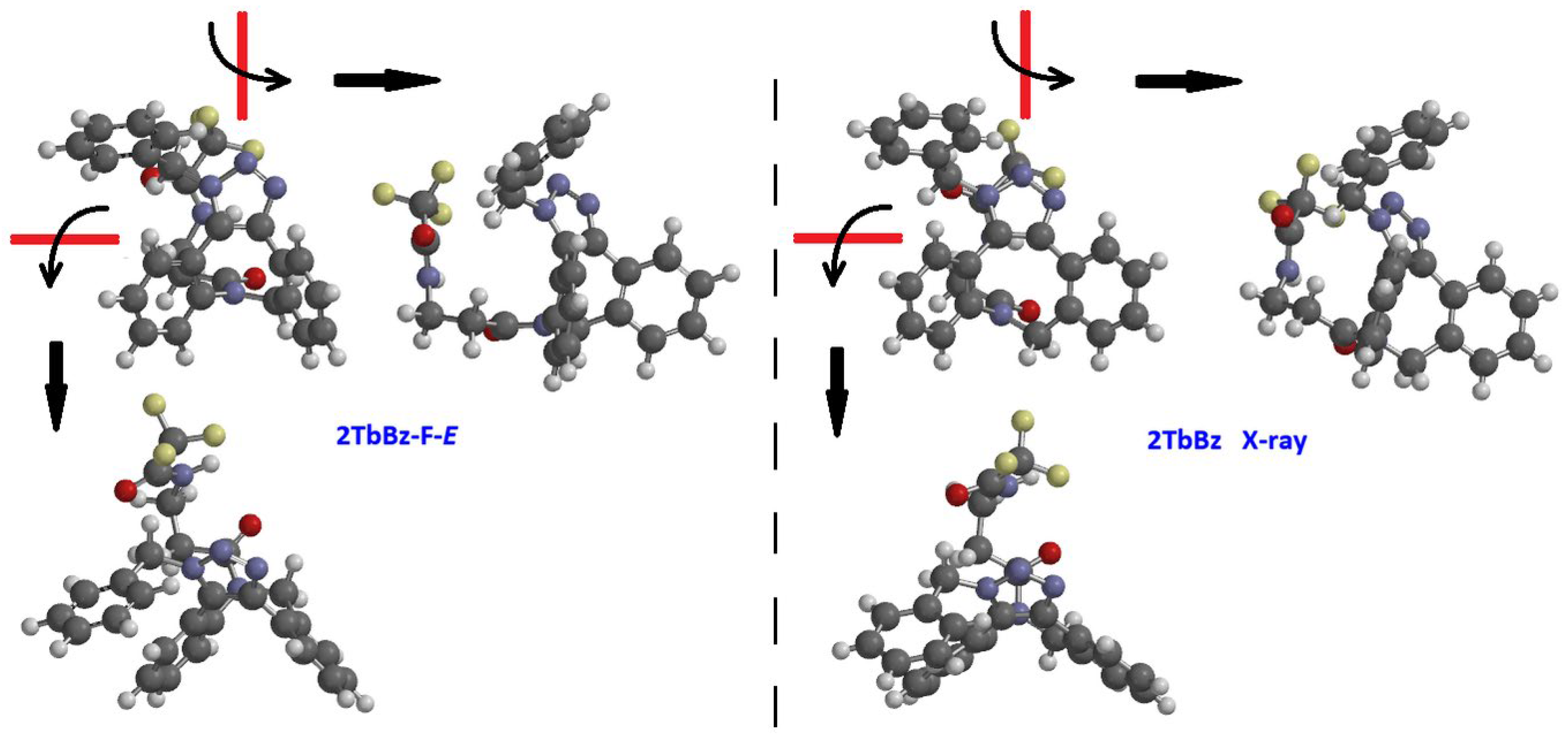

Conformational analysis, carried out in three steps, first by molecular mechanics search method, next by further optimization of all the obtained conformations at a low Hartree-Fock level of theory and, finally, by single point energy evaluation of all the geometries at the Density Functional B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of Theory (DFT), showed 2TbBz to be a conformationally flexible molecule that enjoys a greater conformational freedom compared to its precursor 2. Compound 2TbBz adopts a structure that is chiral as well for the presence of an asymmetry plane related to its tetracyclic framework that also includes the amide group and the Bz substituent (a structural fragment hereafter denoted with the acronim DBCT-Amd-bBz). Cycloaddition reaction released the angle strain of the starting cyclooctynes, resulting in a minimum energy conformation with a bent structure, the angle between the phenyl planes now amounting to about 80°. Inspection of the energy landscape of 2TbBz showed the presence of four different conformations available to the DBCT-Amd-bBz framework: the two more stable ones have very similar energetic stability (within 0.34 kcal/mol) but different spatial disposition of Bz with respect to the triazole plane (in front of, 2TbBz-F, or behind of such plane, 2TbBz-B), with the amide group always showing E disposition (2TbBz-F-E and 2TbBz-B-E); the other two have the structure similar to the previous couple about the Bz spatial disposition, but show the amide group flipped in Z configuration (2TbBz-F-Z and 2TbBz-B-Z, respectively). This configurational-change of the amide portion increases by 1.6 kcal/mol the instability computed passing from the 2TbBz-F-E to the 2TbBz-F-Z structure and of 3.8 kcal/mol from 2TbBz-B-E to 2TbBz-B-Z (the Boltzmann populations for the global E and Z configurations of 2TbBz are 96% and 4%, respectively).

Chromatography on silica allowed to resolve the two regioisomeric triazoles

2TaBz and

2TbBz. Crystals suitable for

X-ray analysis were grown for the first eluted regioisomer

2TbBz from a hexane/CH

2Cl

2 solution. Such

X-ray-diffraction determination revealed the presence in the analyzed crystal of the structure reported in

Figure 4 (right side), which is very similar to the species

2TbBz-F-E, that is to say, to one of the two more stable conformers obtained by computation, the one displaying the benzyl ring in front of the triazole plane and the amide group in

E configuration (

Figure 4, left side).

Theoretical assessment and experimental determination of the activation barriers governing the enantiomerization of compounds 2TaPh, 2TaBz, 2TbPh and 2TbBz: enantiomers of 2TaPh, 2TaBz, 2TbPh and 2TbBz are not atropisomeric at room temperature.

Experimental Determination of ΔGen# Activation Barriers

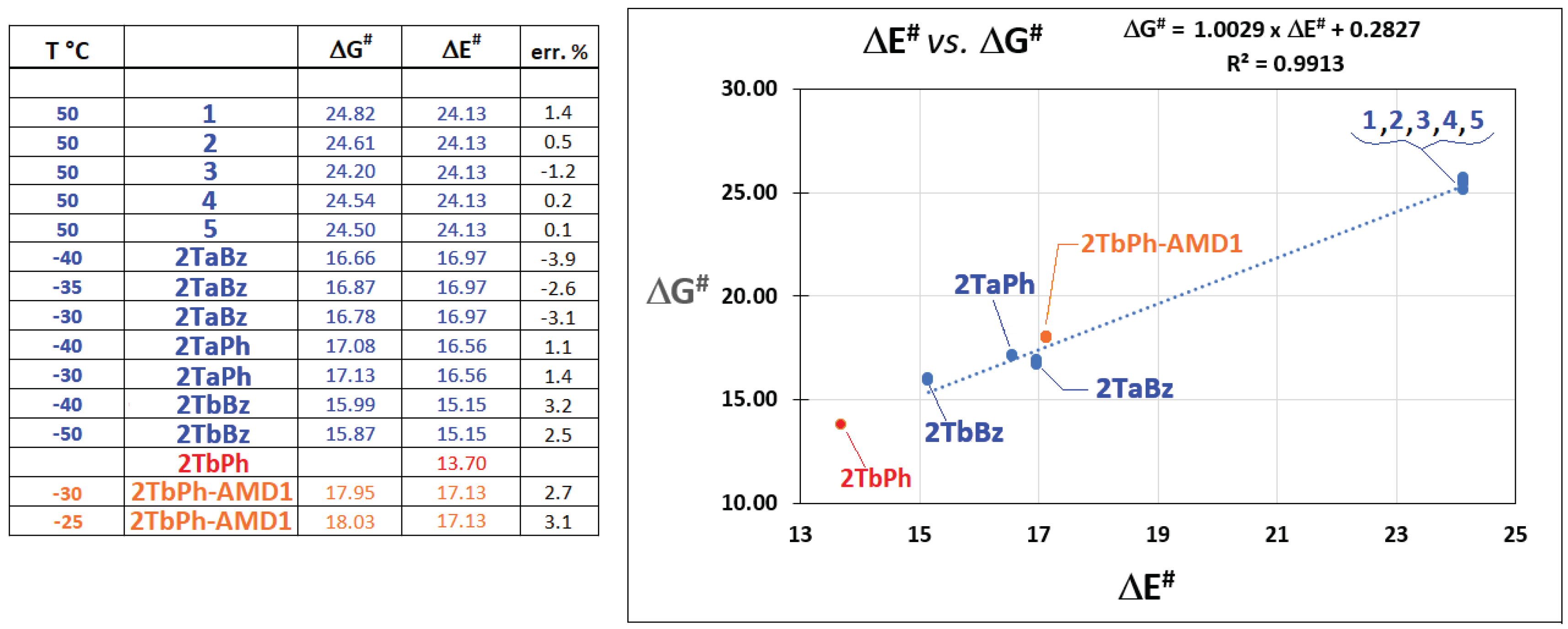

Coherently with the theoretical assessments quoted in the above subparagraph, the attempted HPLC resolution of the enantiomers of 2TaPh, 2TaBz, 2TbPh and 2TbBz at room temperature on the Welk-O1 chiral stationary phase failed due to fast on column enantiomerization. However, after reduction of the column temperature up to −50 °C, deconvolution and split peaks for the enantiomers of 2TaPh, 2TaBz and 2TbBz, but not for 2TbPh, were observed, with the generation of dynamic chromatograms in which, between the resolved peaks, classical plateau zones are clearly visible (see Supporting Information). This behavior is consistent with the t1/2en values estimated for the frameworks 2DBCT-Amd-aPh, 2DBCT-Amd-aBz, 2DBCT-Amd-bPh and 2DBCT-Amd-bBz at the temperature of −50 °C: 41 min; 104 min; 0.06 min; 2 min, respectively. Thus, simulation of the exchange deformed peaks via stochastic model yielded the apparent rate constants, and so, also the related free energy barriers for the on-column enatiomerization [15−20], which at −40 °C correspond (in kcal/mol) to 16.08 for 2TaPh, 16.66 for 2TaBz and 15.99 for 2TbBz (see Supporting Informationrmation for results obtained at other temperatures). Taking into consideration that for the monomolecular flipping process of the DBCT tetracyclic frameworks it is not expected a significant entropy variation, it is also expected that the experimental ΔGen# values are scarcely affected by changes of temperature, and that therefore, within a restricted range of temperature, these data may directly approach the relevant enthalpy changes, ΔHen#. This should make the existing relationship among experimental ΔGen# and computed ΔEen# quantities relatively independent of temperature.

Interestingly, the experimental values of ΔG

en# determined for

2TaBz at the temperatures of −30 °C (16.78 kcal/mol), −35 °C (16.87 kcal/mol) and −40 °C (16.66 kcal/mol) resulted substantially not influenced by these changes, thus giving direct evidence of a negligible entropy effect. On the base of all these evidences and considerations, ΔG

en# values achieved at all the explored temperatures for compounds

2, 2TaPh,

2TaBz and

2TbBz have been plotted against the relevant computed ΔE

en# values (

Figure 5).

Inspection of this plot clearly highlights the very good linear correlation existing among the ΔGen# and ΔEen# data, characterized by R2 = 0.9913, a result that strongly supports the reasons in favor of enthalpy-driven enantiomerization processes. In addition, the same good fit also affords a clear indication about the excellent reliability afforded by the chosen DFT calculations in predicting the activation barriers of enantiomerization involved within the here studied typology of molecules.

The dynamic HPLC plot of

(4?)2TbPh is more complex than expected. On the Welk-O1 column

(4?)2TbPh shows only a single averaged peak at near room temperature, which splits in two peaks of strongly different areas at lower temperature (i.e., interconversion between non-enantiomeric species, according to the very low ΔE

en# of 13.70 kcal/mol estimated for this species by calculation), in slow exchange regime, with a visible plateau that connect the two species in the temperature range -10 ÷ -20°C. The existence of two interconverting species is also confirmed by HPLC on silica, where two peaks of unequal intensities (2.9 ratio at T=-60°C) were observed at low temperature, that eventually coalesce in a single peak at higher temperatures. Simulation of HPLC plots obtained either on the chiral or achiral column gave the rate constants of interconversion k

dr1-2 /k

dr2-1 and the related ΔG

#dr1-2/ΔG

#dr2-1 values for the first and second eluted diastereomers (chiral column: T= −40 °C; k

1-2= 0.32 min

−1, ΔG

# = 15.95 ± 0.1kcal/mol, k

2-1= 0.266 min

−1, ΔG

# = 15.99 ± 0.1kcal/mol, achiral column: T= −25 °C; k

dr1-2 = 0.040 min

−1, ΔG

#dr1-2 = 18.03 ± 0.1 kcal/mol; k

dr2-1= 0.100 min

−1, ΔG

#dr2-1 = 17.62 ± 0.1 kcal/mol; T= −30 °C; k

dr1-2= 0.022 min

−1, ΔG

#dr1-2 = 17.95 ± 0.1 kcal/mol; k

dr2-1= 0.057 min

−1, ΔG

#dr2-1 = 17.50 ± 0.1 kcal/mol) (see Supporting Informationrmation). Such diastereomeric interconversion could be attributed, in principle, to the change from the

E to the

Z configuration of one of the two amide groups within the arm linked to the

2DBCT-Amd framework of

(4?)2TaPh, that which is part of the tetracyclic structure (

AMD1), the other located at the terminal of chain (

AMD2). Information on this has been obtained by theoretical approach. Activation barrier of diastereomerization for the change from the

E to the

Z configuration of both the

AMD1 and

AMD2 amide groups (ΔE

#dr1-2 values), within the

2TbPh structure, has been assessed by DFT optimization (again performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory) of the both ground and transition states relevant to the processes. The obtained results indicated that isomerization of

AMD1 has an activation barrier 4.2 kcal/mol smaller than that of

AMD2 (i.e., 17.13 against 21.31 kcal/mol, respectively), presumably thanks to the conjugation that this can be established with the tetracyclic structure of which it is part. Through comparison of these ones with the experimental ΔG

#dr1-2 values determined at −25 and −30 °C (

Figure 5), it seems completely reasonable to affirm that the observed diastereomerization of

2TbPh is attributable to the

E to

Z flip of the

AMD1 amide group, conclusion that is also supported by the good fit that the values of ΔG

#dr1-2 and ΔE

#dr1-2 show in the above already discussed linear correlation reported in

Figure 5.