Submitted:

12 January 2023

Posted:

16 January 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

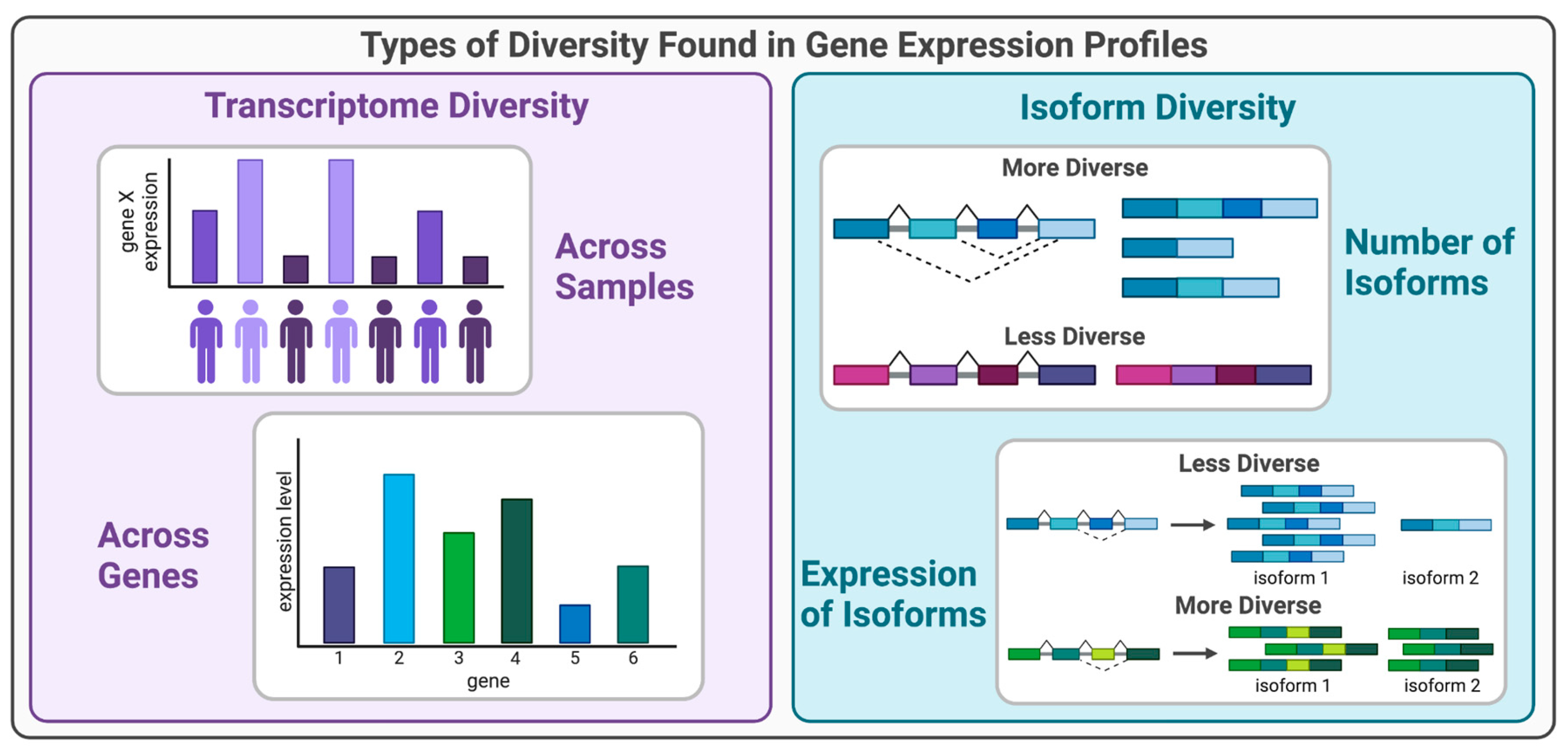

2. Transcriptome Diversity in Gene Expression Profiles

2.1. Biological Processes that Lead to Transcriptome Diversity

2.2. Methods for Quantifying Transcriptome Diversity

3. Isoform Diversity in Gene Expression Profiles

3.1. Biological Processes that Lead to Isoform Diversity

3.2. Methods for Quantifying Isoform Diversity

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Mantione, K.J.; Kream, R.M.; Kuzelova, H.; et al. Comparing bioinformatic gene expression profiling methods: microarray and RNA-Seq. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 2014, 20, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedringhaus, T.P.; Milanova, D.; Kerby, M.B.; et al. Landscape of next-generation sequencing technologies. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 4327–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, R.; Grzelak, M.; Hadfield, J. RNA sequencing: the teenage years. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, A.; Engel, J.; Teichmann, S.A.; et al. A practical guide to single-cell RNA-sequencing for biomedical research and clinical applications. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, A.M.; Peluso, P.; Rowell, W.J.; et al. Accurate circular consensus long-read sequencing improves variant detection and assembly of a human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branton, D.; Deamer, D.W.; Marziali, A.; et al. The potential and challenges of nanopore sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarasinghe, S.L.; Su, S.; Dong, X.; et al. Opportunities and challenges in long-read sequencing data analysis. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.T.; Knop, K.; Sherwood, A.V.; et al. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing maps the complexity of Arabidopsis mRNA processing and m6A modification. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Jabbari, J.S.; Thijssen, R.; et al. Comprehensive characterization of single-cell full-length isoforms in human and mouse with long-read sequencing. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Al-Eryani, G.; Carswell, S.; et al. High-throughput targeted long-read single cell sequencing reveals the clonal and transcriptional landscape of lymphocytes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, S.A.; Hu, W.; Joglekar, A.; et al. Single-nuclei isoform RNA sequencing unlocks barcoded exon connectivity in frozen brain tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melé, M.; Ferreira, P.G.; Reverter, F.; et al. Human genomics. The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science 2015, 348, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manczak, M.; Park, B.S.; Jung, Y.; et al. Differential expression of oxidative phosphorylation genes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: implications for early mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage. Neuromolecular Med. 2004, 5, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown J 3rd, Theisler, C.; Silberman, S.; et al. Differential expression of cholesterol hydroxylases in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34674–34681. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Smyth, G.K. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4288–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcu, E.; Sadler, M.C.; Lepik, K.; et al. Differentially expressed genes reflect disease-induced rather than disease-causing changes in the transcriptome. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, N.J.; Dalrymple, B.P.; Reverter, A. Beyond differential expression: the quest for causal mutations and effector molecules. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squair, J.W.; Gautier, M.; Kathe, C.; et al. Confronting false discoveries in single-cell differential expression. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; et al. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D457–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology resource: enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D325–D334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente, A. From ‘differential expression’ to ‘differential networking’ – identification of dysfunctional regulatory networks in diseases. Trends Genet. 2010, 26, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, S.; Võsa, U.; van der Graaf, A.; et al. Gene co-expression analysis for functional classification and gene-disease predictions. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panwar, B.; Schmiedel, B.J.; Liang, S.; et al. Multi-cell type gene coexpression network analysis reveals coordinated interferon response and cross-cell type correlations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, K.; Huttenhower, C.; Quackenbush, J.; et al. Passing messages between biological networks to refine predicted interactions. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Phillips, C.A.; Rogers, G.L.; et al. Differential Shannon entropy and differential coefficient of variation: alternatives and augmentations to differential expression in the search for disease-related genes. Int. J. Comput. Biol. Drug Des. 2014, 7, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.D.; Madeoy, J.; Strout, J.L.; et al. Gene-expression variation within and among human populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leek, J.T.; Storey, J.D. Capturing heterogeneity in gene expression studies by surrogate variable analysis. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, 1724–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfield, M.L.; Sherlock, G.; Saldanha, A.J.; et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 1977–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lahens, N.F.; Ballance, H.I.; et al. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: implications for biology and medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 16219–16224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viñuela, A.; Snoek, L.B.; Riksen, J.A.G.; et al. Genome-wide gene expression regulation as a function of genotype and age in C. elegans. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viñuela, A.; Brown, A.A.; Buil, A.; et al. Age-dependent changes in mean and variance of gene expression across tissues in a twin cohort. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfelder, S.; Fraser, P. Long-range enhancer-promoter contacts in gene expression control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nott, A.; Holtman, I.R.; Coufal, N.G.; et al. Brain cell type-specific enhancer-promoter interactome maps and disease-risk association. Science 2019, 366, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.E.F.; Kadonaga, J.T. The RNA polymerase II core promoter: a key component in the regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 2583–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danino, Y.M.; Even, D.; Ideses, D.; et al. The core promoter: At the heart of gene expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1849, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Xu, J.; Zeng, D.; et al. Natural Variation in the Promoter of GSE5 Contributes to Grain Size Diversity in Rice. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubi, T.A.; Van De Ven, W.J. Regulation of gene expression by alternative promoters. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Gallagher, J.; Arevalo, E.D.; et al. Enhancing grain-yield-related traits by CRISPR–Cas9 promoter editing of maize CLE genes. Nature Plants 2021, 7, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, K.; Mijakovic, I.; Jensen, P.R. Synthetic promoter libraries--tuning of gene expression. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, P.J.; Davies, I.W.; Attfield, P.V. Facilitating functional analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome using an EGFP-based promoter library and flow cytometry. Yeast 1999, 15, 1747–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.-T.; Corces, V.G. Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerji, J.; Rusconi, S.; Schaffner, W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell 1981, 27, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, M.D.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S. The Post-GWAS Era: From Association to Function. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacita, A.M.; Fullenkamp, D.E.; Ohiri, J.; et al. Genetic Variation in Enhancers Modifies Cardiomyopathy Gene Expression and Progression. Circulation 2021, 143, 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.A.; Jolma, A.; Campitelli, L.F.; et al. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 2018, 172, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavassiliou, A.G. Molecular medicine. Transcription factors. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, M.; Powell, M.J.; Tone, Y.; et al. IL-10 gene expression is controlled by the transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.J.; Goodman, S.J.; Kobor, M.S. DNA methylation and healthy human aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.A. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eijk, K.R.; de Jong, S.; Boks, M.P.M.; et al. Genetic analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression levels in whole blood of healthy human subjects. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlić, R.; Chung, H.-R.; Lasserre, J.; et al. Histone modification levels are predictive for gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 2926–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Yan. K.-K.; Yip, K.Y.; et al. A statistical framework for modeling gene expression using chromatin features and application to modENCODE datasets. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R15.

- Araki, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zang, C.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of histone methylation reveals chromatin state-based regulation of gene transcription and function of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 2009, 30, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidantsis, K.; Giantsis, I.A.; Vratsistas, A.; et al. Correlation between intermediary metabolism, Hsp gene expression, and oxidative stress-related proteins in long-term thermal-stressed Mytilus galloprovincialis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020, 319, R264–R281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasthanasombut, Paisarnwipatpong. Expression of OsBADH1 gene in Indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) in correlation with salt, plasmolysis, temperature and light stresses. Plant Omics.

- Zhang, T.Y.; Labonté, B.; Wen, X.L.; et al. Epigenetic mechanisms for the early environmental regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in rodents and humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hsu, P.J.; Chen, Y.-S.; et al. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Febbo, P.G.; Ross, K.; et al. Gene expression correlates of clinical prostate cancer behavior. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar, J.C.; Matigian, N.A.; Mackay-Sim, A.; et al. Variance of gene expression identifies altered network constraints in neurological disease. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komurov, K.; Ram, P.T. Patterns of human gene expression variance show strong associations with signaling network hierarchy. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, E.Y.; Carl JW Jr, Corrada Bravo, H.; et al. Determinants of expression variability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 3503–3514.

- Bashkeel, N.; Perkins, T.J.; Kærn, M.; et al. Human gene expression variability and its dependence on methylation and aging. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonovsky, E.; Schuster, R.; Yeger-Lotem, E. Large-scale analysis of human gene expression variability associates highly variable drug targets with lower drug effectiveness and safety. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 3028–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igolkina, A.A.; Armoskus, C.; Newman, J.R.B.; et al. Analysis of Gene Expression Variance in Schizophrenia Using Structural Equation Modeling. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, G.; List, M.; Zhang, J.D. Tissue heterogeneity is prevalent in gene expression studies. NAR Genom Bioinform 2021, 3, lqab077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachtiary, B.; Boutros, P.C.; Pintilie, M.; et al. Gene expression profiling in cervical cancer: an exploration of intratumor heterogeneity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 5632–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervouchine, D.D.; Djebali, S.; Breschi, A.; et al. Enhanced transcriptome maps from multiple mouse tissues reveal evolutionary constraint in gene expression. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breschi, A.; Djebali, S.; Gillis, J.; et al. Gene-specific patterns of expression variation across organs and species. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Davidson, N.M.; Wan, Y.K.; et al. A systematic benchmark of Nanopore long read RNA sequencing for transcript level analysis in human cell lines. bioRxiv 2021; 2021.04.21.440736.

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, O.; Reyes-Valdés, M.H. Defining diversity, specialization, and gene specificity in transcriptomes through information theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 9709–9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameri, A.J.; Lewis, Z.A. Shannon entropy as a metric for conditional gene expression in Neurospora crassa. G3 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman, S.; Cunningham, M.J.; Wen, X.; et al. The application of shannon entropy in the identification of putative drug targets. Biosystems. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schug, J.; Schuller, W.-P.; Kappen, C.; et al. Promoter features related to tissue specificity as measured by Shannon entropy. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, R33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado T, J. A. Shannon Entropy Analysis of the Genome Code. Math. Probl. Eng. 2012, 2012.

- Monaco, A.; Amoroso, N.; Bellantuono, L.; et al. Shannon entropy approach reveals relevant genes in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0226190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dérian, N.; Pham, H.-P.; Nehar-Belaid, D.; et al. The Tsallis generalized entropy enhances the interpretation of transcriptomics datasets. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C.; Gate, R.; Lee, D.S.; et al. memento: Generalized differential expression analysis of single-cell RNA-seq with method of moments estimation and efficient resampling. bioRxiv 2022; 2022.11.09.515836.

- Zhang, J.D.; Hatje, K.; Sturm, G.; et al. Correction to: Detect tissue heterogeneity in gene expression data with BioQC. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Phillips, C.A.; Saxton, A.M.; et al. EntropyExplorer: an R package for computing and comparing differential Shannon entropy, differential coefficient of variation and differential expression. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzberg, S.L. Open questions: How many genes do we have? BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 2004, 431, 931–945. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Morais, N.L.; Irimia, M.; Pan, Q.; et al. The evolutionary landscape of alternative splicing in vertebrate species. Science 2012, 338, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.T.; Sandberg, R.; Luo, S.; et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.J.; Smith, C.W.J.; Jiggins, C.D. Alternative splicing as a source of phenotypic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alasoo, K.; Rodrigues, J.; Danesh, J.; et al. Genetic effects on promoter usage are highly context-specific and contribute to complex traits. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berget, S.M.; Moore, C.; Sharp, P.A. Spliced segments at the 5′ terminus of adenovirus 2 late mRNA*. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1977, 74, 3171–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, E.; Buckley, M.; Yang, Y.H. Estimation of data-specific constitutive exons with RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, M.C.; Will, C.L.; Lührmann, R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell 2009, 136, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graveley, B.R. Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world. Trends Genet. 2001, 17, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.W.; Valcárcel, J. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: the logic of combinatorial control. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baralle, F.E.; Giudice, J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtis, K.C.; Baker, B.S. Drosophila doublesex gene controls somatic sexual differentiation by producing alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding related sex-specific polypeptides. Cell 1989, 56, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, L.M.; Bono, L.M.; Genissel, A.; et al. Sex-specific expression of alternative transcripts in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, R79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.B.; Boley, N.; Eisman, R.; et al. Diversity and dynamics of the Drosophila transcriptome. Nature 2014, 512, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibilisco, L.; Zhou, Q.; Mahajan, S.; et al. Alternative Splicing within and between Drosophila Species, Sexes, Tissues, and Developmental Stages. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naftaly, A.S.; Pau, S.; White, M.A. Long-read RNA sequencing reveals widespread sex-specific alternative splicing in threespine stickleback fish. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 1486–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, T.F.; Palmer, D.H.; Wright, A.E. Sex-Specific Selection Drives the Evolution of Alternative Splicing in Birds. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekhman, R.; Marioni, J.C.; Zumbo, P.; et al. Sex-specific and lineage-specific alternative splicing in primates. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabzuni, D.; Ramasamy, A.; Imran, S.; et al. Widespread sex differences in gene expression and splicing in the adult human brain. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlebach, G.; Veiga, D.F.T.; Mays, A.D.; et al. The impact of biological sex on alternative splicing. bioRxiv 2020; 490904.

- Xu, Q.; Modrek, B.; Lee, C. Genome-wide detection of tissue-specific alternative splicing in the human transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3754–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, A.R.; Gomes, A.Q.; Barbosa-Morais, N.L.; et al. Tissue-specific splicing factor gene expression signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 4823–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Castle, J.; et al. Defining the regulatory network of the tissue-specific splicing factors Fox-1 and Fox-2. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 2550–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buljan, M.; Chalancon, G.; Eustermann, S.; et al. Tissue-specific splicing of disordered segments that embed binding motifs rewires protein interaction networks. Mol. Cell 2012, 46, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, M.H.; Wu, X.; et al. Cell-Type-Specific Alternative Splicing Governs Cell Fate in the Developing Cerebral Cortex. Cell 2016, 166, 1147–1162e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.P.; Wilks, C.; Charles, R.; et al. ASCOT identifies key regulators of neuronal subtype-specific splicing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Botvinnik, O.B.; Lovci, M.T.; et al. Single-Cell Alternative Splicing Analysis with Expedition Reveals Splicing Dynamics during Neuron Differentiation. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 148–161.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalek, A.K.; Satija, R.; Adiconis, X.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals bimodality in expression and splicing in immune cells. Nature 2013, 498, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Pham, M.H.C.; Ko, K.S.; et al. Alternative splicing isoforms in health and disease. Pflugers Arch. 2018, 470, 995–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, M.M.; Swanson, M.S. RNA mis-splicing in disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczak, M.; Reiss, J.; Cooper, D.N. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum. Genet. 1992, 90, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.Y.; Alipanahi, B.; Lee, L.J.; et al. RNA splicing. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science 2015, 347, 1254806. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voineagu, I.; Wang, X.; Johnston, P.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature 2011, 474, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Shai, O.; Lee, L.J.; et al. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steijger, T.; Abril, J.F.; Engström, P.G.; et al. Assessment of transcript reconstruction methods for RNA-seq. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsari, B.; Guo, T.; Considine, M.; et al. Splice Expression Variation Analysis (SEVA) for inter-tumor heterogeneity of gene isoform usage in cancer. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Akerman, M.; Sun, S.; et al. SpliceTrap: a method to quantify alternative splicing under single cellular conditions. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 3010–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, J.P.; Klinck, R.; Bramard, A.; et al. Identification of alternative splicing markers for breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 9525–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, G.A.; Conesa, A.; Fernández, E.A. A benchmarking of workflows for detecting differential splicing and differential expression at isoform level in human RNA-seq studies. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soneson, C.; Matthes, K.L.; Nowicka, M.; et al. Isoform prefiltering improves performance of count-based methods for analysis of differential transcript usage. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty, M.L.; Underwood, J.G.; Nelson, B.J.; et al. Transcriptional fates of human-specific segmental duplications in brain. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharon, D.; Tilgner, H.; Grubert, F.; et al. A single-molecule long-read survey of the human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.D.; Soulette, C.M.; van Baren, M.J.; et al. Full-length transcript characterization of SF3B1 mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals downregulation of retained introns. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sim, A.; Wan, Y.; Goeke, J. bambu: Reference-guided isoform reconstruction and quantification for long read RNA-Seq data. 2022.

- Leung, S.K.; Jeffries, A.R.; Castanho, I.; et al. Full-length transcript sequencing of human and mouse cerebral cortex identifies widespread isoform diversity and alternative splicing. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 110022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.R.; Liu, C.S.; Romanow, W.J.; et al. Altered cell and RNA isoform diversity in aging Down syndrome brains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, W.; Granjeaud, S.; Puthier, D.; et al. Entropy measures quantify global splicing disorders in cancer. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguchi, Y.; Ozaki, Y.; Abdelmoez, M.N.; et al. NanoSINC-seq dissects the isoform diversity in subcellular compartments of single cells. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padonou, F.; Gonzalez, V.; Provin, N.; et al. Aire-dependent transcripts escape Raver2-induced splice-event inclusion in the thymic epithelium. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e53576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Trapnell, C.; Donaghey, J.; et al. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne-Weiler, T.; Weatheritt, R.J.; Best, A.J.; et al. Efficient and Accurate Quantitative Profiling of Alternative Splicing Patterns of Any Complexity on a Laptop. Mol. Cell 2018, 72, 187–200.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankó, B.; Szikora, P.; Pór, T.; et al. SplicingFactory-splicing diversity analysis for transcriptome data. Bioinformatics 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, J.E.; Dehghannasiri, R.; Salzman, J. The SpliZ generalizes ‘percent spliced in’ to reveal regulated splicing at single-cell resolution. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekath, T.; Dugas, M. Differential transcript usage analysis of bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data with DTUrtle. Bioinformatics 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, J.; Leger, A.; Prawer, Y.D.J.; et al. Accurate expression quantification from nanopore direct RNA sequencing with NanoCount. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Mahfouz, A.; et al. A spatially resolved brain region- and cell type-specific isoform atlas of the postnatal mouse brain. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiberi, S.; Robinson, M.D. BANDITS: Bayesian differential splicing accounting for sample-to-sample variability and mapping uncertainty. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, R.; Humphreys, D.T.; Janbandhu, V.; et al. Sierra: discovery of differential transcript usage from polyA-captured single-cell RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froussios, K.; Mourão, K.; Simpson, G.; et al. Relative Abundance of Transcripts ( RATs): Identifying differential isoform abundance from RNA-seq. F1000Res. 2019, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trincado, J.L.; Entizne, J.C.; Hysenaj, G.; et al. SUPPA2: fast, accurate, and uncertainty-aware differential splicing analysis across multiple conditions. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.I.; Knowles, D.A.; Humphrey, J.; et al. Annotation-free quantification of RNA splicing using LeafCutter. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitting-Seerup, K.; Sandelin, A. The Landscape of Isoform Switches in Human Cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Hill, A.; Packer, J.; et al. Single-cell mRNA quantification and differential analysis with Census. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Sanguinetti, G. BRIE: transcriptome-wide splicing quantification in single cells. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, M.; Robinson, M.D. DRIMSeq: a Dirichlet-multinomial framework for multivariate count outcomes in genomics. F1000Res. 2016, 5, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero-Garcia, J.; Barrera, A.; Gazzara, M.R.; et al. A new view of transcriptome complexity and regulation through the lens of local splicing variations. Elife 2016, 5, e11752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, L.D.; Cao, Y.; Pau, G.; et al. Prediction and Quantification of Splice Events from RNA-Seq Data. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, J.D.; Hu, Y.; Prins, J.F. Robust detection of alternative splicing in a population of single cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irimia, M.; Weatheritt, R.J.; Ellis, J.D.; et al. A highly conserved program of neuronal microexons is misregulated in autistic brains. Cell 2014, 159, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Park, J.W.; Lu, Z.-X.; et al. rMATS: robust and flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from replicate RNA-Seq data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, E5593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapnell, C.; Hendrickson, D.G.; Sauvageau, M.; et al. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschoff, M.; Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; Glatting, K.-H.; et al. SplicingCompass: differential splicing detection using RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; Reyes, A.; Huber, W. Detecting differential usage of exons from RNA-seq data. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Y.; Wang, E.T.; Airoldi, E.M.; et al. Analysis and design of RNA sequencing experiments for identifying isoform regulation. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Package | Year | Bulk or Single Cell | Transcriptional Diversity Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| memento [84] | 2022 | Single cell | Variability |

| BioQC [85] | 2017 | Bulk | Shannon Entropy |

| EntropyExplorer [86] | 2015 | Bulk | Differential Shannon Entropy |

| Package Name | Year | Bulk or Single Cell | Differential Analysis Type: Exon/Transcript or Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpliZ [142] | 2022 | Single cell | DEU (PSI) |

| DTUrtle [143] | 2021 | Both | DTU |

| NanoCount [144] | 2021 | Bulk | DTU |

| SplicingFactory [141] | 2021 | Bulk | Other - Diversity |

| scisorseqr [145] | 2021 | Single cell | DTU (modified) |

| ASCOT [113] | 2020 | Single cell | DEU (PSI) |

| BANDITS [146] | 2020 | Bulk | DTU |

| Sierra [147] | 2020 | Single cell | DTU |

| RATs [148] | 2019 | Bulk | DTU |

| SUPPA2 [149] | 2018 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| LeafCutter [150] | 2018 | Bulk | Other - Intron Excision |

| Whippet [140] | 2018 | Bulk | DTU |

| SEVA [123] | 2018 | Bulk | Other - Variability |

| IsoformSwitchAnalyzeR [151] | 2017 | Bulk | DTU |

| Census/Monocle [152] | 2017 | Single cell | DEU (PSI) |

| BRIE [153] | 2017 | Single cell | DEU (PSI) |

| DRIM-Seq [154] | 2016 | Bulk | DTU |

| JunctionSeq | 2016 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| MAJIQ [155] | 2016 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| SGSeq [156] | 2016 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| SingleSplice [157] | 2016 | Single cell | DTU |

| Limma (diffSplice) [18] | 2015 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| VAST-TOOLS [158] | 2014 | Bulk | DTU |

| rMATS [159] | 2014 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| CuffDiff2 [160] | 2013 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| SplicingCompass [161] | 2013 | Bulk | DTU |

| DEXSeq [162] | 2012 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| SpliceTrap [124] | 2011 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

| MISO [163] | 2010 | Bulk | DEU (PSI) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).