Submitted:

10 January 2023

Posted:

13 January 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Delphi Panel

2.2. Prisma research

2.3. Statements drafting

3. Results

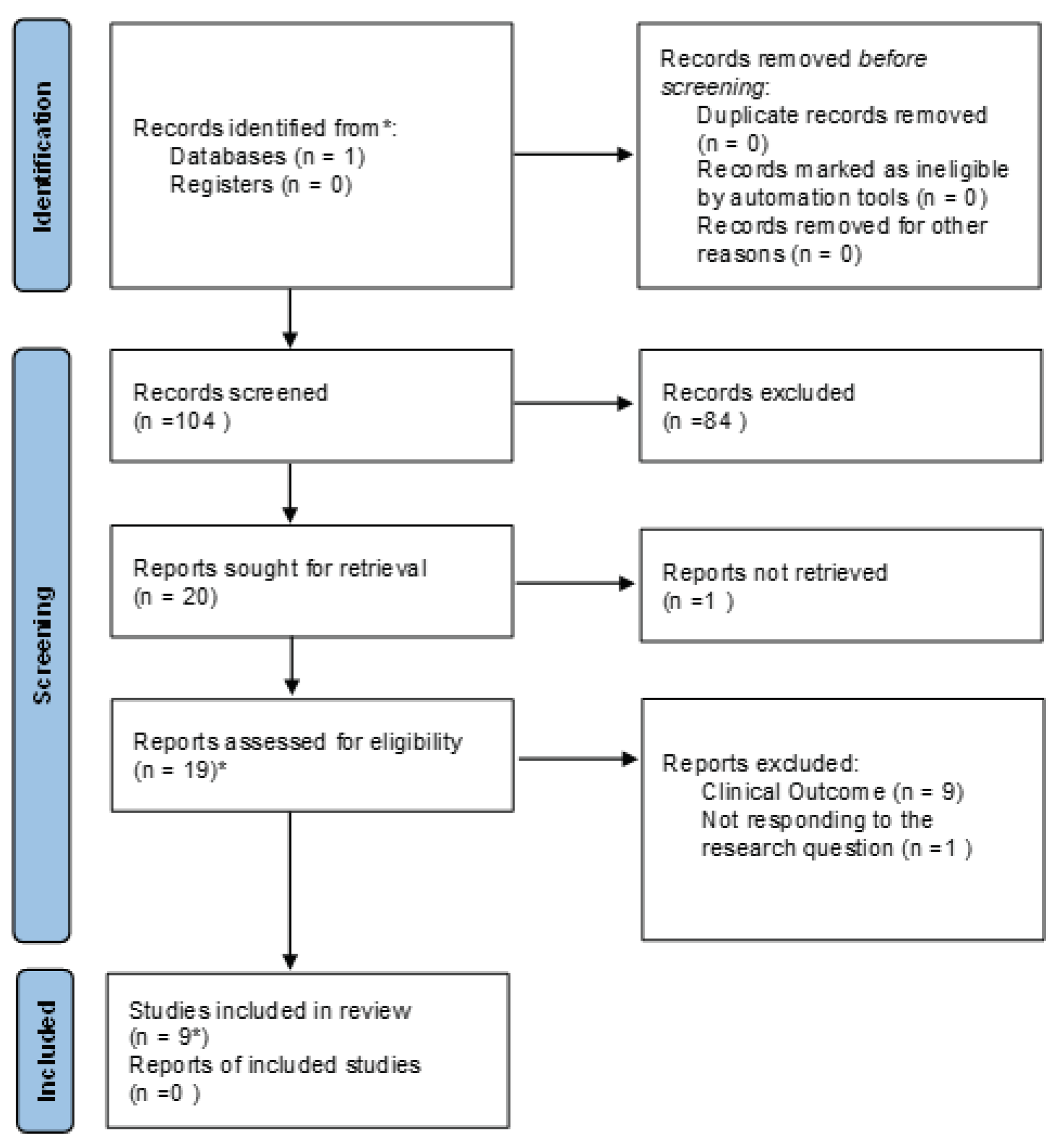

3.1. Prisma results

3.2. Delphi Panel results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 |

Article 2, MDR 2017/745: For the purposes of this Regulation, the following definitions apply:

|

References

- Cooper, T.E.; Teng, C.; Howell, M.; Teixeira-Pinto, A.; Jaure, A.; Wong, G. D-Mannose for Preventing and Treating Urinary Tract Infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022, 8, CD013608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ala-Jaakkola, R.; Laitila, A.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Lehtoranta, L. Role of D-Mannose in Urinary Tract Infections–a Narrative Review. Nutrition Journal 2022, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mydock-McGrane, L.K.; Cusumano, Z.T.; Janetka, J.W. Mannose-Derived FimH Antagonists: A Promising Anti-Virulence Therapeutic Strategy for Urinary Tract Infections and Crohn’s Disease. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2016, 26, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglione, F.; Musazzi, U.M.; Minghetti, P. Considerations on D-Mannose Mechanism of Action and Consequent Classification of Marketed Healthcare Products. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 636377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alton, G.; Hasilik, M.; Niehues, R.; Panneerselvam, K.; Etchison, J.R.; Fana, F.; Freeze, H.H. Direct Utilization of Mannose for Mammalian Glycoprotein Biosynthesis. Glycobiology 1998, 8, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Chia, C.; Jiao, X.; Jin, W.; Kasagi, S.; Wu, R.; Konkel, J.E.; Nakatsukasa, H.; Zanvit, P.; Goldberg, N.; et al. D-Mannose Induces Regulatory T Cells and Suppresses Immunopathology. Nat Med 2017, 23, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, R.H. Mannose Metabolism. II. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1971, 24, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durán, J.M.; Cano, M.; Peral, M.J.; Ilundáin, A.A. D-Mannose Transport and Metabolism in Isolated Enterocytes. Glycobiology 2004, 14, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, N. Carbohydrates as Future Anti-Adhesion Drugs for Infectious Diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006, 1760, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Ichikawa, M.; Freeze, H.H. Mannose Metabolism: More than Meets the Eye. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2014, 453, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European_Community MANUAL ON BORDERLINE AND CLASSIFICATION IN THE COMMUNITY REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR MEDICAL DEVICES. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/35582 (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Capone, L.; Geraci, A.; Giovagnoni, E.; Marcoaldi, R.; Palazzino, G. Elements of assessment and discernment between medical devices and medicinal products. Rapporti ISTISAN - Istituto Superiore di Sanità 2012, 65 pp.

- European Commission MDCG 2022 – 5 Guidance on Borderline between Medical Devices and Medicinal Products under Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on Medical Devices 2022.

- Leone, M.G. Medical Devices Made of Substances: A New Challenge. Frontiers in Drug Safety and Regulation 2022, 2, 952013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loblaw, D.A.; Prestrud, A.A.; Somerfield, M.R.; Oliver, T.K.; Brouwers, M.C.; Nam, R.K.; Lyman, G.H.; Basch, E. Americal Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines: Formal Systematic Review-Based Consensus Methodology. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 3136–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and Quantification of Content Validity. Nursing research 1986, 35, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S.; Craig, J. Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research: ENTREQ. BMC medical research methodology 2012, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- France, E.F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E.A.; Jepson, R.G.; Maxwell, M.; Roberts, R.J.; Turley, R.L.; Booth, A. Improving Reporting of Meta-Ethnography: The EMERGe Reporting Guidance. BMC medical research methodology 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Journal of the European Union L 117 - Volume 60. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2017:117:FULL&from=EN (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- DIRECTIVE 2001/83/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL OF 6 NOVEMBER 2001 ON THE COMMUNITY CODE RELATING TO MEDICINAL PRODUCTS FOR HUMAN USE. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/directive-2001/83/ec-european-parliament-council-6-november-2001-community-code-relating-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- European Commission REGULATION (EU) 2017/745 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 5 April 2017 on Medical Devices, Amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and Repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC; 2017.

- European Commission (2015a). Guidance Document on the Demarcation between the Cosmetic Products Directive 76/768 and the Medicinal Products Directive2001/83 as Agreed between the Commission Services and the Competent Authorities of Member States. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/13032/attachments/1/translations (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- European Union Court (2012). Judgment C-308/11–Chemische Fabrik Kreussler and Co. GmbH v Sunstar Deutschland GmbH, Formerly John O. Butler GmbH. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:62011CJ0308&from=GA (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Hung, C.-S.; Bouckaert, J.; Hung, D.; Pinkner, J.; Widberg, C.; DeFusco, A.; Auguste, C.G.; Strouse, R.; Langermann, S.; Waksman, G. Structural Basis of Tropism of Escherichia Coli to the Bladder during Urinary Tract Infection. Molecular microbiology 2002, 44, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, J.; Berglund, J.; Schembri, M.; De Genst, E.; Cools, L.; Wuhrer, M.; Hung, C.-S.; Pinkner, J.; Slättegård, R.; Zavialov, A.; et al. Receptor Binding Studies Disclose a Novel Class of High-Affinity Inhibitors of the Escherichia Coli FimH Adhesin. Mol Microbiol 2005, 55, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusumano, C.K.; Pinkner, J.S.; Han, Z.; Greene, S.E.; Ford, B.A.; Crowley, J.R.; Henderson, J.P.; Janetka, J.W.; Hultgren, S.J. Treatment and Prevention of Urinary Tract Infection with Orally Active FimH Inhibitors. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sager, C.P.; Eriş, D.; Smieško, M.; Hevey, R.; Ernst, B. What Contributes to an Effective Mannose Recognition Domain? Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2017, 13, 2584–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eris, D.; Preston, R.C.; Scharenberg, M.; Hulliger, F.; Abgottspon, D.; Pang, L.; Jiang, X.; Schwardt, O.; Ernst, B. The Conformational Variability of FimH: Which Conformation Represents the Therapeutic Target? ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Kleeb, S.; Lemme, K.; Rabbani, S.; Scharenberg, M.; Zalewski, A.; Schädler, F.; Schwardt, O.; Ernst, B. FimH Antagonists: Structure–Activity and Structure–Property Relationships for Biphenyl A-d-Mannopyranosides. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 1404–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharenberg, M.; Schwardt, O.; Rabbani, S.; Ernst, B. Target Selectivity of FimH Antagonists. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2012, 55, 9810–9816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, J.E. Screening of Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli for Expression of Mannose-Selective Adhesins: Importance of Culture Conditions. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 1981, 13, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofek, I.; Mosek, A.; Sharon, N. Mannose-Specific Adherence of Escherichia Coli Freshly Excreted in the Urine of Patients with Urinary Tract Infections, and of Isolates Subcultured from the Infected Urine. Infection and Immunity 1981, 34, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, G.; Brooks, H.J. In Vivo Attachment of E Coli to Human Epithelial Cells. N Z Med J 1984, 97, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hultgren, S.J.; Schwan, W.R.; Schaeffer, A.J.; Duncan, J.L. Regulation of Production of Type 1 Pili among Urinary Tract Isolates of Escherichia Coli. Infection and immunity 1986, 54, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, J.; Schrettenbrunner, A.; Schröter, G.; Düvel, H.; Schmidt, G.; Goebel, W. Characterization of Escherichia Coli Wild-Type Strains by Means of Agglutination with Antisera Raised against Cloned P-, S-, and MS-Fimbriae Antigens, Hemagglutination, Serotyping and Hemolysin Production. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Mikrobiologie und Hygiene. Series A: Medical Microbiology, Infectious Diseases, Virology, Parasitology 1986, 261, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.H.; Pinkner, J.S.; Roth, R.; Heuser, J.; Nicholes, A.V.; Abraham, S.N.; Hultgren, S.J. FimH Adhesin of Type 1 Pili Is Assembled into a Fibrillar Tip Structure in the Enterobacteriaceae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995, 92, 2081–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronald, L.S.; Yakovenko, O.; Yazvenko, N.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Aprikian, P.; Thomas, W.E.; Sokurenko, E.V. Adaptive Mutations in the Signal Peptide of the Type 1 Fimbrial Adhesin of Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 10937–10942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Hung, C.S.; Pinkner, J.S.; Walker, J.N.; Cusumano, C.K.; Li, Z.; Bouckaert, J.; Gordon, J.I.; Hultgren, S.J. Positive Selection Identifies an in Vivo Role for FimH during Urinary Tract Infection in Addition to Mannose Binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 22439–22444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribano, D.; Sarshar, M.; Prezioso, C.; Lucarelli, M.; Angeloni, A.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; Ambrosi, C. D-Mannose Treatment Neither Affects Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli Properties nor Induces Stable FimH Modifications. Molecules 2020, 25, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcon, J.; Schubert, S.; Stief, C.G.; Magistro, G. In Vitro Efficacy of Phytotherapeutics Suggested for Prevention and Therapy of Urinary Tract Infections. Infection 2019, 47, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribić, R.; Meštrović, T.; Neuberg, M.; Kozina, G. Proposed Dual Antagonist Approach for the Prevention and Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli. Medical Hypotheses 2019, 124, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalas, V.; Pinkner, J.S.; Hannan, T.J.; Hibbing, M.E.; Dodson, K.W.; Holehouse, A.S.; Zhang, H.; Tolia, N.H.; Gross, M.L.; Pappu, R.V.; et al. Evolutionary Fine-Tuning of Conformational Ensembles in FimH during Host-Pathogen Interactions. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1601944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhomkar, P.; Materi, W.; Semenchenko, V.; Wishart, D.S. Transcriptional Response of E. Coli upon FimH-Mediated Fimbrial Adhesion. Gene regulation and systems biology 2010, 4, GRSB S4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatton, N.E.; Baumann, C.G.; Fascione, M.A. Developments in Mannose-Based Treatments for Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli -Induced Urinary Tract Infections. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, B.; Ofek, I.; Clegg, S.; Abraham, S.N. Type 1 Fimbrial Shafts of Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella Pneumoniae Influence Sugar-Binding Specificities of Their FimH Adhesins. Infect Immun 1994, 62, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, J.; Pu, Y.; Zhang, Z.-T.; Hasty, D.L.; Wu, X.-R. Tamm-Horsfall Protein Binds to Type 1 Fimbriated Escherichia Coli and Prevents E. Coli from Binding to Uroplakin Ia and Ib Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 9924–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.J.; Kalas, V.; Pinkner, J.S.; Chen, S.L.; Spaulding, C.N.; Dodson, K.W.; Hultgren, S.J. Positively Selected FimH Residues Enhance Virulence during Urinary Tract Infection by Altering FimH Conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 15530–15537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Mo, W.-J.; Sebbel, P.; Min, G.; Neubert, T.A.; Glockshuber, R.; Wu, X.-R.; Sun, T.-T.; Kong, X.-P. Uroplakin Ia Is the Urothelial Receptor for Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli: Evidence from in Vitro FimH Binding. Journal of cell science 2001, 114, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feenstra, T.; Thøgersen, M.S.; Wieser, E.; Peschel, A.; Ball, M.J.; Brandes, R.; Satchell, S.C.; Stockner, T.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Rees, A.J.; et al. Adhesion of Escherichia Coli under Flow Conditions Reveals Potential Novel Effects of FimH Mutations. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017, 36, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, E.K.; Chmiel, J.S.; Plotkin, B.J.; Schaeffer, A.J. Effect of D-Mannose and D-Glucose on Escherichia Coli Bacteriuria in Rats. Urol. Res. 1983, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pani, A.; Valeria, L.; Dugnani, S.; Senatore, M.; Scaglione, F. Pharmacodynamics of D-Mannose in the Prevention of Recurrent Urinary Infections. Journal of Chemotherapy 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenger, S.M.; Bradley, M.S.; Thomas, D.A.; Bertolet, M.H.; Lowder, J.L.; Sutcliffe, S. D-Mannose vs Other Agents for Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection Prevention in Adult Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2020, 223, 265.e1–265.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranjčec, B.; Papeš, D.; Altarac, S. D-Mannose Powder for Prophylaxis of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. World J Urol 2014, 32, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakides, R.; Jones, P.; Somani, B.K. Role of D-Mannose in the Prevention of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections: Evidence from a Systematic Review of the Literature. European Urology Focus 2021, 7, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nunzio, C.; Bartoletti, R.; Tubaro, A.; Simonato, A.; Ficarra, V. Role of D-Mannose in the Prevention of Recurrent Uncomplicated Cystitis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CURIA - European Union Court (2009). Judgment C-140/07. Available online: https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=76342&doclang=EN (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- CURIA - European Union Court (2012). Judgment C-308/11. Available online: https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?%20numC-308/11&languageEN (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- MEDDEV 2. 1/3 Rev 3. MEDICAL DEVICES: Guidance Document - Borderline Products, Drug-Delivery Products and Medical Devices Incorporating, as an Integral Part, an Ancillary Medicinal Substance or an Ancillary Human Blood Derivative.

- Official Journal of the European Union, L 136, 30 April 2004 EUR-Lex - L:2004:136:TOC - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AL%3A2004%3A136%3ATOC (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Union, P.O. of the E. Case C-109/12: Judgment of the Court (Fourth Chamber) of 3 October 2013 (Request for a Preliminary Ruling from the Korkein Hallinto-Oikeus — Finland) — Laboratoires Lyocentre v Lääkealan Turvallisuus- Ja Kehittämiskeskus, Sosiaali- Ja Terveysalan Lupa- Ja Valvontavirasto (Reference for a Preliminary Ruling — Approximation of Laws — Medical Devices — Directive 93/42/EEC — Medicinal Products for Human Use — Directive 2001/83/EC — Right of the Competent National Authority to Classify as a Medicinal Product for Human Use a Product Marketed in Another Member State as a Medical Device Bearing a CE Marking — Applicable Procedure), CELEX1. Available online: http://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a3223c0a-54cf-11e3-8945-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Kleeb, S.; Jiang, X.; Frei, P.; Sigl, A.; Bezençon, J.; Bamberger, K.; Schwardt, O.; Ernst, B. FimH Antagonists: Phosphate Prodrugs Improve Oral Bioavailability. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 59, 3163–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statement on definitions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N# | Statement | References | ROUND I | ROUND II |

| 1 |

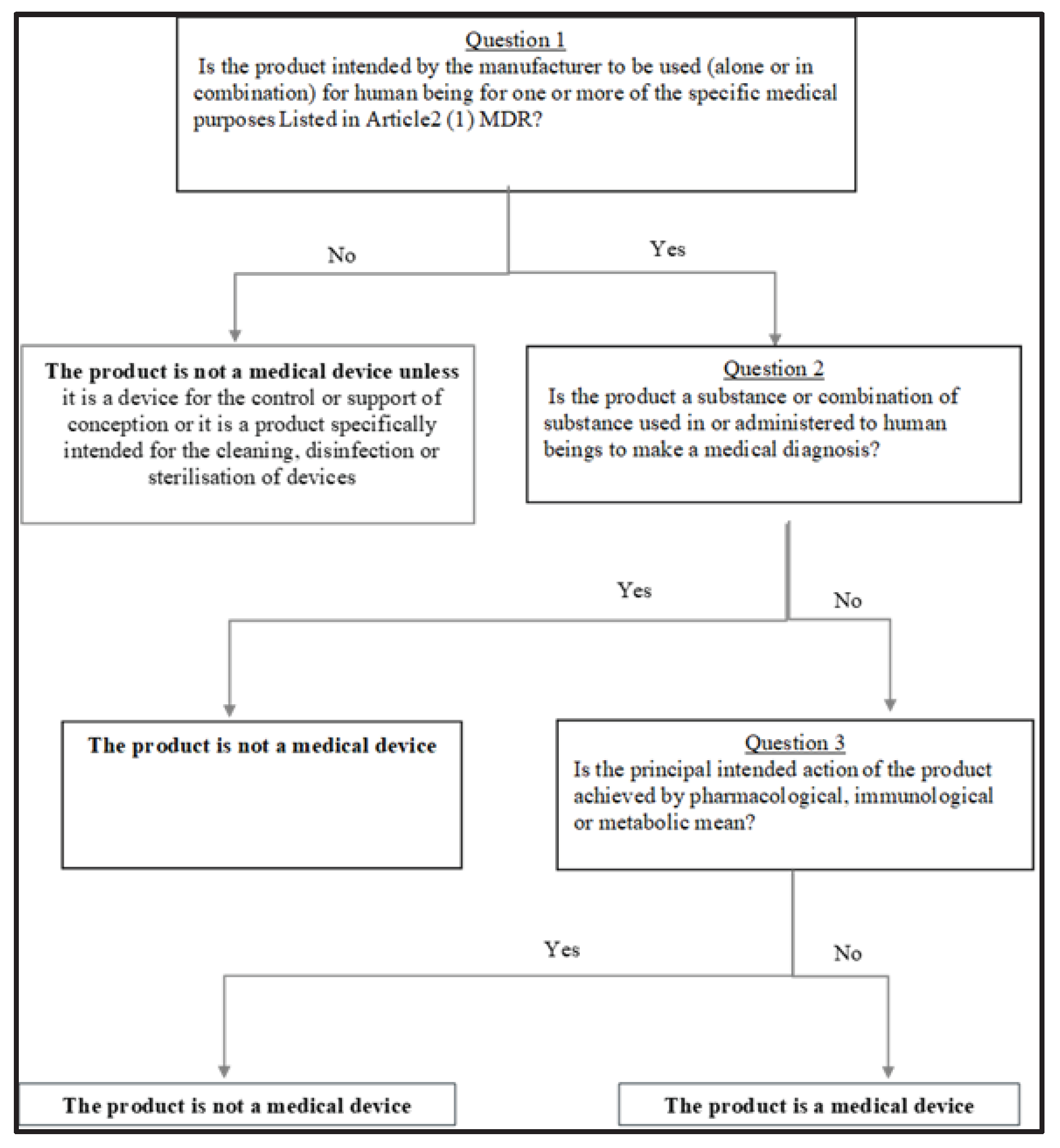

Regulatory perspective regarding Medicinal Device According to the panel, the pharmacological definition of drug is included in the regulatory perspective on medicinal product: a) any product or combination of products presented as having properties for treating or preventing disease in human beings; b) any product or combination of products which may be used in or administered to human beings either with a view to restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action, or to making a medical diagnosis. Therefore, the MDGC definition insists on mechanism of action by which the medicinal products produce its activity. Regulatory perspective regarding Medical Device The MDCG 2022-5 guidelines adds a relevant aspect: it indicates that medical device does not achieve its principal intended action by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means, in or on the human body, but which may be assisted in its function by such means. |

MDCG 2022-5 European Parliament and Council [13]. Directive 2001/83/EC of 6 November 2001 on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use n.d.[21] Directive 2001/83/EEC Art. 1.2 Directive 93/42/CEE European Parliament and Council (2017). Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending directive 2001/83/EC, regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing council directives 90/385/EEC and 93/ 42/EEC n.d [22] |

6 | 8 |

| 2 |

Pharmacological action According to the MDCG 2022-5, the pharmacological action is an interaction at a molecular level between a product or its metabolites and a constituent of the human body which results in initiation, enhancement, reduction or blockade of physiological functions or pathological processes. Examples of constituents of the human body may include, among others: cells and their constituents (cell membranes, intracellular structures, RNA, DNA, proteins, e.g. membrane proteins, enzymes), components of extracellular matrix, components of blood and components of body fluids. Moreover, the EU jurisprudence clarified that in order for a product to be regarded as having a 'pharmacological action', an interaction with any cellular component present in the user's body (e.g. bacteria, viruses, or parasites) is enough, if this influences positively the physiological functions of the human body. Although not a completely reliable criterion, the presence of a dose-response correlation is indicative of a pharmacological effect. |

MDCG 2022-5 MedDev 2.1/3 rev 3 (GUIDELINES RELATING TO THE APPLICATION OF: THE COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 90/385/EEC ON ACTIVE IMPLANTABLE MEDICAL DEVICES THE COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 93/42/EEC ON MEDICAL DEVICES [13] European Parliament and Council (2001). Directive 2001/83/EC of 6 November 2001 on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use n.d.[21]. European Commission (2015). Guidance document on the demarcation between the cosmetic products directive 76/768 and the medicinal products directive 2001/83 as agreed between the commission services and the competent authorities of member states[23]. European Union Court (2012). Judgment C-308/11–chemische fabrik kreussler and Co. GmbH v sunstar deutschland GmbH, formerly John O. Butler GmbH [24]. |

7 | 8 |

| 3 |

Immunological action According to the MDCG 2022-5The immunological action is initiated by a product or its metabolites on the human body and mediated or exerted (i.e. stimulation, modulation, blocking, replacement) by cells or molecules involved in the functioning of the immune system (e.g. lymphocytes, toll-like receptors, complement factors, cytokines, antibodies). |

MDCG 2022-5 [13] | 7 | 8 |

| 4 |

Metabolic action According to the MDCG 2002-5, the metabolic action involves an alteration, including stopping, starting or changing the rate, extent or nature of a biochemical process, whether physiological or pathological, participating in, and available for, function of the human body. |

MDCG 2022-5 [13] | 8 | 8 |

| Statements on D-mannose | ||||

| 5 | D-mannose is indicated to prevent the recurrence of cystitis and other uncomplicated infections of the lower urinary tract uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections (uncomplicated UTI) | 7 | 7 | |

| 6 | D-mannose is not indicated to prevent the acute episode of recurrence of cystitis and other uncomplicated infections of the lower Urinary Tract (uncomplicated UTI). | 8 | 8 | |

| 7 |

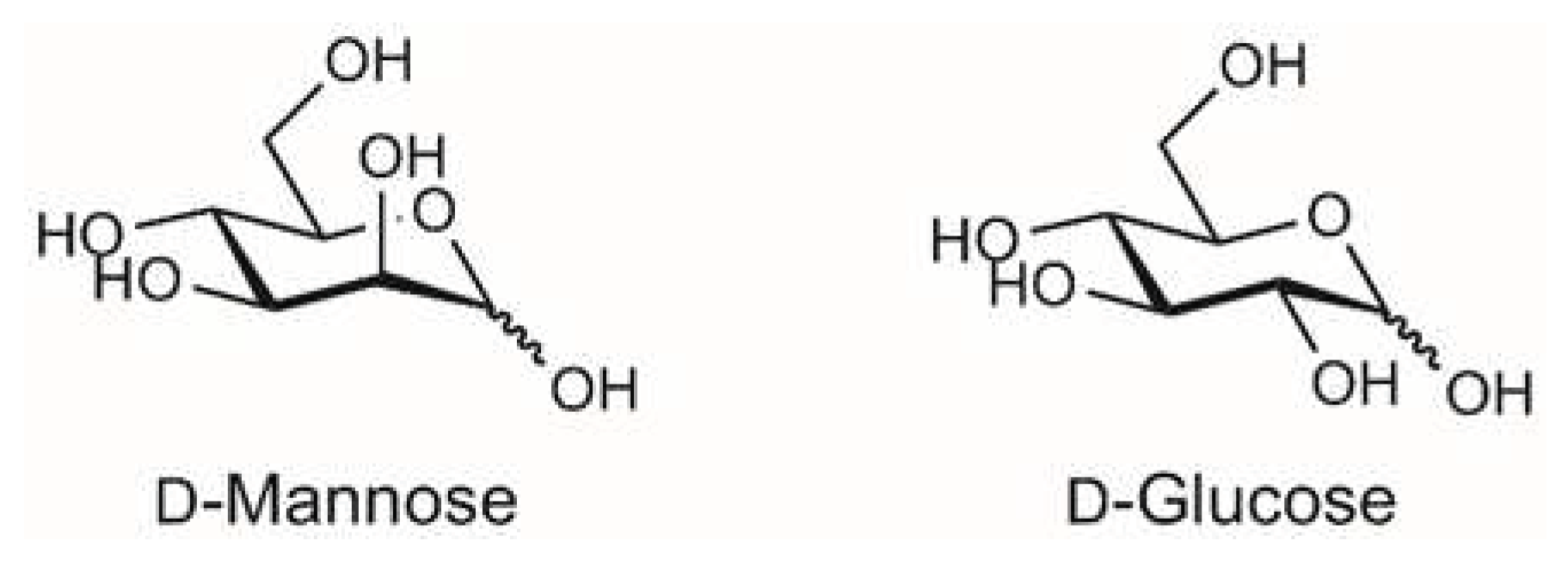

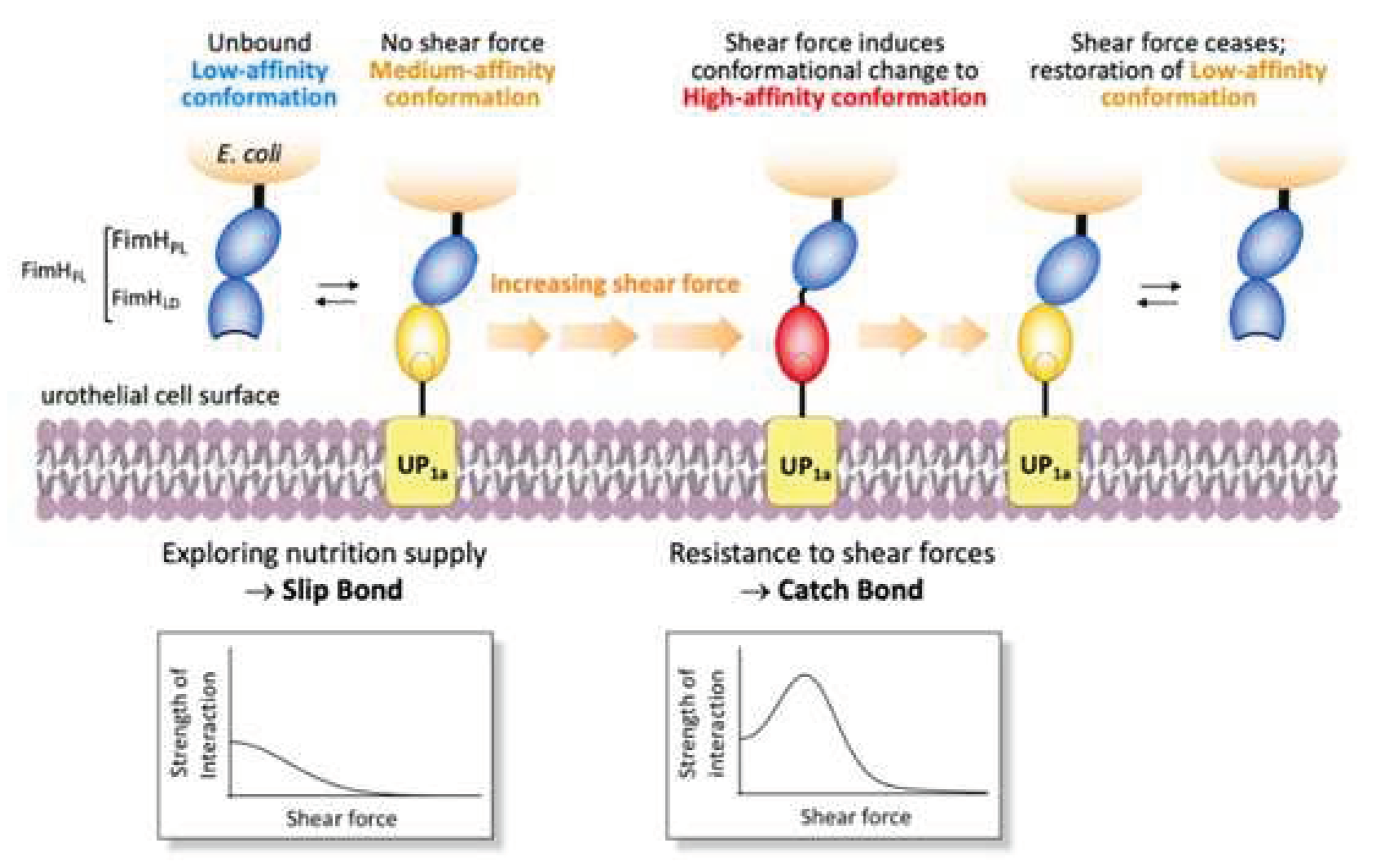

D-mannose binds the bacterial FimH adhesin and prevents interaction with mannsylated proteins or lipids on urothelial cells. The interaction of the uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) with mannosylated proteins on the bladder epithelium is the main mechanism to initiate the infection (Box 2). This interaction occurs via the FimH adhesin located at the tip of the type I fimbria of E. coli, which is the virulence factor in UTI pathogenesis (See box 1 for details). Accordingly, FimH was identified as a therapeutic target in the late 1980s, a substantial body of research has been generated focusing on the development of FimH-targeting mannose-based anti-adhesion therapies. The rationale to the use of D-mannose in UTIs prophylaxis is therefore based on its competitive inhibition of bacterial adherence to mannosylated urothelial cells [9,25,26]. In other words, FimH on E. coli can no longer bind to urothelial cells, preventing the adhesion abilities of the bacterium. The inhibition of the adhesion step thus blocks the invasion of urothelial cells and avoids the requirement for antibiotic, reducing the risk of resistance [27]. Antiadhesive FimH antagonists provide a therapeutic opportunity to prevent UTIs because they result in selection pressure on UPEC. FimH is therefore a suitable therapeutic target. Most of the information regarding the mechanism (crystal structures) are coming from evidence on mannosides. However, crystal evidence demonstrates that the binding pocket is identical [3,9,28,29,30]. As far as D-mannose, it was reported to bind FimH with a KD value of 2.3 uM [26]. Furthermore, Scharenberg [31] compared different FimH antagonists (including D-mannose), belonging to different compound families and their affinities for FimH and eight human mannose receptors. D-mannose showed inhibition of binding for all proteins tested, including FimH, at a concentration of 50 mM (more than 90% inhibition). Results demonstrated that affinity between carbohydrates and pathogen is predominantly caused by the combined strength of multiple interactions with ligands: multivalent carbohydrates on the host cell and multimeric and/or clustered receptors on pathogens greatly support binding between the interaction partners [31]. |

Fein 1981 [32] Ofek 1981 [33] Sharon 2006 [9] Reid 1984 [34] Hultgren 1986 [35] Hacker 1986 [36] Jones 1995 [37] Ronald 2008 [38] Chen 2009 [39] Hung 2002 [25] Cusumano 2011 [27] Scribano 2020 [40] Mydock-McGrane 2015 [3] Marcon 2019 [41] Ribić 2019 [42] Scharenberg 2012 [31] Pang 2012 [30] Kalas 2017 [43] Bhomkar 2010 [44] Eris 2016 [29] Hatton 2020 [45] Bouckaert 2005 [26] Sager 2017 [28] Madison 1994 [46] Pak 2001 [47] Schwartz 2013 [48] Zhou 2001 [49] |

7 | 8 |

| 8 | D-mannose binding occurs via reversible hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions not altering the protein conformation. Evidence confirmed binding of D-mannose. A function of the hydrophobic edge around the binding pocket of FimH may be to direct the sugar into the pocket in a manner that facilitates polar interactions. More specifically, the mannose ring makes 10 direct hydrogen bonds to the side-chains of residues Asp54, Gln133, Asn135 and Asp140, and to the main chain of Phe1 and Asp47, and indirect water-mediated hydrogen bonds via O2 to the side-chain of Glu133 and to the main chain oxygen of Phe1 and Gly14 [26]. The alpha-anomeric hydroxyl group O1 of mannose is involved in a hydrogen-bonding water network with the Asn138 and Asp140 side-chains, through a water molecule [26]. Crystallographic studies showed that all hydroxyl groups of the D-mannose sugar ring bind in a negatively charged pocket of FimH making ten direct hydrogen-bonds with residues in the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) [25]. Moreover, Tyr48 and Tyr137 residues are positioned so as to form a “tyrosine gate” to which dimannoside/oligomannosides form van der Waals interactions [25,26,42]). These interactions do not change the conformation of FimH or surface bacterial structures [4,40]. The lack of downstream effects or changes in FimH is demonstrated by crystallographic evidence demonstrating that the binding of D-mannose to FimH does not alter the protein conformation [26]. Blocking the adhesion of FimH to cell receptors impedes the following invasion process and facilitates the bacterial removal with the urinary flux |

Hung 2002 [25] Bouckaert 2005 [26] Feenstra 2017 [50] Ribić 2019 [42] Scribano 2020 [40] Scaglione 2021 [4] |

5 | 7 |

| 9 |

The interaction between D-mannose and the bacterial FimH delineates a classical drug-receptor interaction, and thus a pharmacological action. Evidence shows that the contact between D-mannose and FimH is due to specific interactions between specific atoms of the D-mannose and specific amino acids residues in a specific binding region of the adhesin [42,50]. On the other side, such an interaction does not result in conformational changes of the bacterial protein leading to activation of intracellular pathways important for the intended effect, i.e. there is no activation of a signalling pathway which is a condition for a pharmacological effect of the receptor-ligand interaction. |

Bouckaert 2005 [26] Ribic 2019 [42] Feenstra 2017 [50] |

- | 3 |

| 10 |

D-mannose does not achieve its effect on pathogen adhesion by antibiotic-like bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity. In vitro tests show that, once D-mannose is removed from the urine, or once exogenous D-mannose is washed away from the culture broth, the bacterium regains its full ability to grapple to epithelial cells. This fact clearly indicates that D-mannose does not impair vitality of the microbe, and therefore is not a biocide [27]. No bacteriostatic or bactericidal effects were observed in the strains tested in Marcon [41]. In addition, it is well demonstrated that, unlike antibiotics and antiseptics such as nitrofurantoin, D-mannose does not induce resistance [9], also after long-term use [40]. No alteration of FimH could be observed in vitro after removal of the D-mannose, nor in the D-mannose-treated bladder cells [40]. D-mannose just prevents the bacterial binding to mannosylated eukaryotic receptors. In this sense, the 2012 EU Court stating that chlorhexidine 0.12% shall not be considered as a cosmetic [24], since the mechanism of action of chlorhexidine is pharmacological because killing the bacteria, is here not applicable. |

Scribano 2020 [40] Cusumano 2011 [27] Sharon 2006 [9] Marcon 2019 [41] |

7 | 7 |

| 11 |

D-mannose shows a concentration-dependent effect. According to the MDC 2022-5 guidelines [13], although not an exhaustive criterion, the presence of a dose-response correlation is indicative of a pharmacological, metabolic or immunological mode of action. D-mannose action is dose-dependent [4,51]. The IC50 for the anti-adhesive efficacy and anti-invasion activity of D-mannose were 0.51 mg/mL and 0.30 mg/mL, respectively, both with concentration-dependent inhibition [52].D-Mannose efficiently blocked the adhesive properties of all type 1 fimbriae-positive isolates in low concentration (0.2%, 2 mg/mL) [41]. Evidence demonstrated that no differences in bacterial growth were observed for D-mannose concentrations up to 10% (10 mg/mL)[40]. Besides, the effect of a high dosage (1.5%) of D-mannose on human epithelial cells was also evaluated and no macroscopic differences in the bladder epithelia cells were assessed (shape, integrity, adhesiveness, cytoplasmic vacuolization, proliferation, or cytotoxic effects) [40]. |

Michaels 1983 [51] Scribano 2020 [40] Scaglione 2021 [4] Marcon 2019 [41] Pani 2022 [52] |

6 | 6 |

| 12 |

The interaction between FimH and D-mannose does not result in an immunological answer with regard to the main effect. The specific effect of D-mannose is not directly connected to a specific interaction with antibodies, immunocompetent cells or other components of the human immune system but occurs in the bladder once D-mannose is excreted into the urine. There D-mannose acts creating a chemical barrier on FimH which prevents the adhesion, i.e. chemically impeding the FimH [2,40]. D-mannose has positive immunoregulatory effects on T-cells in mice with autoimmune diabetes and airway inflammation, which however are not relevant for its effects to prevent urinary tract infections [6]. |

Scribano 2020 [40] Ala Jaakkola 2022 [2] Zhang 2017 [6] |

6 | 6 |

| 13 | The intended effect of D-mannose does not involve metabolic responses downstream its interaction with FimH. D-mannose prevents interaction between the body's urothelial cells and UPEC by binding to bacterial FimH. The binding between FimH and the D-mannose does not trigger downstream metabolic processes in the bacterium and the host cell. The lack of downstream effects is demonstrated by the full reversion of the binding activity of E. coli in the agglutination assay, since FimH remains unmodified. Moreover, in addition to its binding inhibitory activity, D-mannose is scarcely used to sustain bacterial growth. Scribano et al. 2020 demonstrated that, in D-glucose deficiency, a second hierarchy in bacterial growth rates was shown encompassing D-fructose/L-arabinose followed by D-mannose [40]. As a matter of fact, during infection E. coli has sufficient glucose in the bladder to sustain its metabolism and, thus, the high administered doses of D-mannose for prevention of UTIs have no effects on bacterial metabolism and growth [40]. Besides, D-mannose does not interfere with the antibiotic activity and does not change bacterial morphology or motility compared to untreated bacterial cells [40]. Analysis of the therapeutic efficacy of various phytotherapeutics and their antimicrobial compounds demonstrated that D-mannose showed no bacteriostatic effect at 10% (100 mg/mL) while efficiently blocking the adhesive properties of all type 1 fimbriae-positive isolates at much lower concentration (0.2%, 2 mg/mL) and showed no bacteriostatic effect [41]. Evidence also shows that removal of D-mannose from FimH by applying mechanical forces left the adhesin fully proficient to bind to human urothelial mannosylated receptors [40]. Scribano et al. demonstrated that the clinical regimen of D-mannose to prevent acute UTIs (3 g/day for three days, then 1.5 g/day for 10 days) does not lead to FimH mutations that modify bacterial adhesiveness [40]. No macroscopic differences in the bacterial shape, integrity, adhesiveness, cytoplasmic vacuolization, proliferation, or cytotoxic were observed in vitro with D-mannose [40]. As already reported, D-mannose interaction with the FimH adhesin neither causes nor blocks signal transduction and subsequent biochemical reactions. |

Bhomkar, 2010 [44] Scribano 2020 [40] Marcon 2019 [41] |

7 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).