0. Introduction

As part of the implementation of a new optional substance use disorder (SUD) training program for final year medical students, we wanted to assess its impact on students in terms of skills development (pre and post-test evaluation). To evaluate the impact of the educational program of trainee’s representations and attitudinal skills development we looked for a questionnaire to assess their attitudes towards SUD adapted to our criteria. Various instruments were found in the literature in French and English, but they had a number of limitations for our study. The first was that most of them focused on either illicit drugs or alcohol and/or perceptions of professional attitudes (e.g. Drug and Drug Problems Perception Questionnaires and Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire [

1,

2] and we wanted to be able to assess both. Others were not culturally transferable to our context (e.g. Attitudes Mental Illness Questionnaire [

3], some were limited in the dimensions they explored (e.g. The Addiction Beliefs Scale [

4], Short Understanding of Substance Abuse Scale [

5], Attitudes and Opinions Survey [

6], or were difficult to use on a large scale given their qualitative or vignette analysis approach. Many also had limited «validity» and «reliability», not having been used beyond the study itself. On this basis, we selected the Substance Abuse Attitude Survey (SAAS) developed by Chappel et al. in 1985 [

7]. Even though this questionnaire was developed more than thirty years ago, it was still relevant in our context. Indeed, it was designed to evaluate educational programs in the framework of initial or continuing education [

8] and allows to explore 5 dimensions (also called factors). These are “Permissiveness” (implies accepting substance use within a continuum of normal human behaviour), “Treatment intervention” (relates to an individual’s orientation toward perceiving substance use/misuse in the context of treatment and intervention), “Non-stereotypism” (relates to a person’s non-reliance on popular societal stereotypes of substance use and substance users), “Treatment optimism” (relates to an optimistic perception of treatment and the possibility of a successful outcome) and “Non-moralism” (linked to an individual’s absence or avoidance of moralistic perspective when considering substance use and substance users). This questionnaire has been validated and used in many previous studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In our study, we selected its short version, the “Brief SAAS” [

14] to maximise its completion since in our program it was administered in parallel with a knowledge test. Since an adaptation to our cultural and societal context was necessary, we named this new questionnaire the “bSAAS”( See Appendix A). The first objective of this study was to carry out an exploratory factor analysis of our bSAAS questionnaire in view of its adaptation to ensure its good internal consistency and structure. The second was to identify whether student’s representations were influenced by certain socio-demographic characteristics.

1. Materials and Methods

Questionnaire

The SAAS questionnaire validated widely by the literature consists of 50 items. For our study, we preferred its brief version, the Brief SAAS, which is used by Yale School of Medicine to evaluate their SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment) training programs and which is limited to 25 items. We adapted it to the Belgian context through consultation with various experts (including 3 general practitioners working in addiction medicine, 2 medical researchers, a SUD expert psychiatrist, 2 health sociologists and a professor of psychology). We removed the questions about marijuana experimentation among young people and Alcoholics Anonymous, which are less present in Belgium than in the U.S. We added a question on paramedical professionals who are much more involved than para-professional counsellors in our context. After consensus, we split the questions on alcohol and drugs to be able to assess whether there were different attitudes according to the substances consumed. This resulted in a questionnaire with 29 items (

Table 1 and

Table S1). We assumed that perceptions of legal and illegal substances might differ. Indeed, a common perception of the Belgian population is that the term “drugs” refers de facto to illegal drugs. This difference has been highlighted in studies conducted among Belgian doctors [

15,

16]. Each item was coded according to a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To ensure the cross-cultural validity of the questionnaire, we used bilateral translation by 2 certified translators and pretested the questionnaire with trainees and medical doctors from different professional backgrounds and with lay people.

In order to characterise our population and to better understand the factors favoring the students’ representations, we included several socio-demographic data (sex, age, origin); data related to the personal and professional background linked to substance use; data related to the type of professional orientation (choice of specialty); as well as data related to the perception of their own health (we wanted to evaluate whether this influenced the way in which addicts are perceived). This questionnaire, which was called “bSAAS” by our research team, has already been used in a previous study to evaluate the attitudes of medical students towards substance use in pregnancy and showed a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77) [

17].

Data Collection

The questionnaire was presented to 923 final year medical students in three consecutive years (2019, 2020 and 2021). It was administered face-to-face to final year medical students in 2019 and online in 2020 and 2021 given the context of the Sars-Cov-2 crisis. A total of 657 students completed the questionnaire with an average response rate of 71.1%. 80 students completed the questionnaire at the time of enrollment in the theoretical addictology course. We considered questionnaires with fewer than 10 responses, those with responses for only one of the two substances and those with no socio-demographic data to be invalid. On this basis, 615 questionnaires were retained.

Statistical Methodology

First, we analysed the correlations between the 29 items and performed Bartlett’s test of sphericity to ensure that a factor analysis was appropriate. Several items were highly correlated (r > 0.30) and the Bartlett test was significant (p <0.001). The Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.71 and, our sample including 615 subject was large enough to perform factor analyses. The factor analysis was carried out in 3 steps and we decided to retain the factors with eigenvalues > 1 and with kat least 3 items with a weighting > |0.40|, while keeping a sufficiently high % of variance explained (75%) [

18,

19]. Five items (

Table S1) and one item (

Table S1) were not retained after the first and second factor analysis respectively. The final factor analysis included 23 items and three factors were retained. Factor scores were obtained for each of these factors, retaining for each factor only those items with a weight > |0.30| and taking the mean of these items. Five items were found in two factors, in this case the item was assigned to the factor with the highest loading or if the loadings were nearly equal, to the one that most closely matched the content of the factor. The mean scores were analysed according subject’s characteristics using Student’s t-tests or one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Where appropriate, ANOVA was followed by multiple comparison tests with Bonferroni’s correction or a linear trend test. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the consistency of the 23 items included in the analysis as well as the consistency of the items selected for each factor separately. All analyses were performed with STATA SE v16.1 software.

Ethics Committee

The research protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethics Committee of ERASME-ULB) on February 25, 2019, ref: P2019/156. Informed consent was obtained from all participants who filled out and returned the questionnaire.

2. Results

Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80 for all 23 items. Considering the items with a weighting > |0.30|, the Cronbach’s alphas were 0.8, 0.70 and 0.59, respectively for the 10 items of factor I, the 9 items of factor II and the 4 items of factor III. We kept the same factor name for Factor I as mentioned by Jenkins et al. [

9], i.e. “Stereotypes and moralism”, because the items correlated with this factor reflected value judgments. As in that study conducted on secondary school students, which retained only three factors (stereotypes and moralism, treatment and permissiveness), the students in our study did not seem to differentiate between stereotype and moralism items.

The name “Treatment optimism” for Factor II found in Chappel et al., 1985 and Jenkins et al., 1990, has also been retained. As in the first study, we find here negative correlations in relation to this factor since we have kept these items stricto senso (not recoded in the other direction). This also enabled us to define this factor well with items correlated negatively and therefore opposed to optimism, such as the item “An alcoholic who has had several relapses is unlikely to be treated”.

Factor III differed from the baseline studies [

7,

9] and seemed to be clearly marked by the specialised domain, with items correlated to hospital and specialist management in the field. We therefore named it “Specialised treatment”. These different factors and the corresponding items are shown in

Table 1.

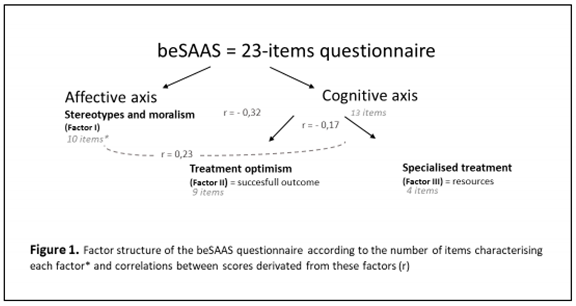

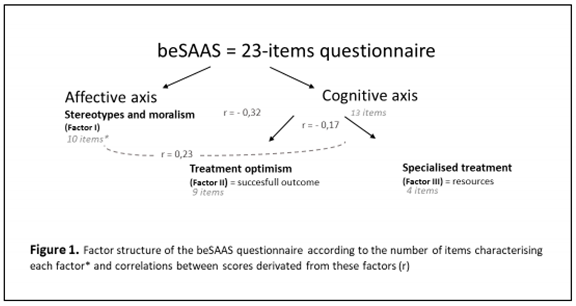

Concerning the 3 dimensions or factors retained in our final analysis: “Stereotypes and moralism”, “ Treatment optimism” and “Specialised treatment”, we separated them into 2 axes based on the 3 major learning domains conceptualised by Benjamin Bloom in 1956 (cognitive, affective and psychomotor) and further developed thereafter [

20,

21]. On one hand, we identified a psycho-affective axis, based on moral judgments, and on the other, a cognitive axis, linked to the perception of health care skills. The latter includes Factor II, which evaluates a dimension linked to results (the perception of the effectiveness of the treatment, “successful outcome”) and Factor III concerning the perception of the needed resources (material and human resources). The correlations between the scores derived from these factors (r = -0.32, 0.23 and -0.17 for score 1 and score 2, score 1 and score 3 and score 2 and score 3 respectively) were weak to moderate, which is an additional argument for maintaining a three-dimensional questionnaire. The score “Stereotypes and moralism” was positively correlated with the “Specialised treatment” score and negatively correlated with the “Treatment optimism” score. The score “Specialised treatment” was positively correlated with “Stereotypes and moralism” score and negatively correlated with “Treatment optimism” score (see Figure 1).

To be noted that the items dealing with the same content for drugs and alcohol had good or excellent correlations (r =0.55-0.85).

Secondly, we analysed the factor scores according to the different socio-demographic data collected (

Table 2). There was a significant increase in the mean score for “Stereotypes and moralism” (Factor I) with age. This mean score was also statistically significantly higher for male respondents (P=0.037). The differences in the average score “stereotypes and moralism” according to “subject-parent” origin were significant (p=0.005), among people of non-European origin, we observed a higher average score than that of people of Belgian or Belgian-European origin. Subjects who didn’t consume substance had a higher “Stereotypes and moralism” mean score than people who had consumed but the differences were at the limit of statistical significance (p=0.065). Conversely, the average score of those who had ever used cannabis was low. This was also the case for those who had been in contact with patients with SUD in specific centers (e.g. addiction centers, harm reduction centers, prisons, etc.) or who had enrolled in the optional SUD training, who differed significantly from the other respondents in having very low average scores on “Stereotypes and moralism”. There was no statistically significant difference in the average factorial I scores according to the perception of one’s own health and SUD in the environment. The same was true for the choice of specialty, although students who wanted to go into gynecology had a lower average score. There was no statistically significant difference in the mother’s level of education either, although for this last variable, the average score was higher for those whose mother’s level of education was low.

For Factor II, “Treatment optimism”, the average score remained close to the mean of the total sample (2.94) across the different socio-demographic characteristics. This means that there was a tendency, independent of subject characteristics, to be optimist towards treatment and possible interventions. However, the 23 respondents who had no contact with people with SUD at work showed a clear tendency towards low optimism about treatment (average score lower than the others, NS).

In relation to Factor III, which assessed attitudes towards specialised treatment of SUD, male respondent had a significantly lower mean score (p=0.035). People whose origin was outside Europe had a significantly higher mean score than Belgian-European (p=0.019) or European (p=0.049). We also found a tendency for people with no contact with SUD patients, or with contact in hospitals, to be in favor of “Specialised treatment” (NS). On the other hand, those who went to general practice did not seem to be in favor of “Specialised treatment”. The same was true for respondents enrolled in addiction training (p=0.031). Details of these results can be found in

Table 2.

3. Discussion

Our study, through the adaptation of a short version of the Substance Abuse Attitude Survey questionnaire administered to medical students in Belgium, allowed us to select a 23-item questionnaire with good face validity and content validity (via experts panel and pre-test), construct validity (via exploratory factor analysis, convergent correlations between alcohol and drugs items and discriminatory correlations between factor scores) and very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80). That allowed us also to highlight interesting results concerning influencing factors of medical students attitudes regarding SUD. The three dimensions selected: “Stereotypes and moralism”, “Treatment optimism” and “Specialised treatment”, which we have divided into two axes (affective and cognitive), are useful for exploring the learning objectives pursued in our educational system. These results can also guide us in the methodological choices to be made to achieve these objectives.

We can see some differences with the reference studies [

7,

9]. As the latter pointed out, the factor structure logically changes according to the characteristics of the people completing it. Our target population and questionnaire were somewhat different from those of the first study, conducted on different profiles of already experienced professionals (non-clinicians, clinicians not in the field, and clinicians in the field) and those of the second study conducted on college students (first degree of university). This may partly explain the difference in the factors observed.

In our sample, which also seems to be representative of our target population with a good response rate (71.1%) given the circumstances (Sars-Cov-2 crisis) and the survey carried out partly online, we find an over-representation of women, which corresponds to the feminisation of medicine over the last few years and is in line with the latest gender report from our university [

22], which reports 62% female students in medicine. We also see that 72.7% of students have a mother with a high level of education. These attitudes are therefore reflecting a selected population of future caregivers who are very likely to differ, also by the number of years between these studies, from the populations studied in previous articles and from the general population at the socio-demographic level (gender imbalance and particularly high educated population).

With regard to the factors, it is firstly interesting to note that the dominant factor in our study (explaining 40.3% of the variance) was, like that of the college students, the factor relating to “Stereotypes and moralism”. This differs from the case of Chappel et al., 1985, where it was the factor relating to permissiveness. The predominance of this affective dimension in a medical student audience can be explained in different ways. Firstly, we hypothesise, as the SUD topic being little taught in the formal curriculum, that their representations are at this stage still based on representations conveyed by society or by their community. These representations are probably also influenced by their internship experience, where the impact of role modelling (defined here as “

a teaching by example and influencing students in an unintentional, unaware, informal and episodic manner” [

23] is documented on students [

23,

24]. Students may integrate both positive and negative behaviors of their role models and mentors, perhaps more so in the context of choosing a career path, where they are looking for identifying models. The informal and hidden curricula play a key role in the transmission of attitudes and values [

24]. This is consistent with the study of Kidd et al. in 2020 [

25], which justified the fact that students tended to adopt more negative attitudes over time by the potential impact of the «hidden curriculum» through which students internalise the “negative” attitudes of their supervisors. The hidden curriculum includes “

a set of values, behavioral norms, attitudes, skills, and knowledge that medical students learn implicitly” [

26]. In our study, the (non) place of contact seemed to play an important role on stereotypes and moralism, the latter being particularly marked if there was no contact or if it took place only in the hospital system. Conversely, scores were low if students had had multiple contacts or in specific settings for patients with SUD such as SUD centres. This demonstrates the importance of varied and supervised experiences to reduce stereotypes. The fact of never having used substances on one’s own also seemed to encourage these stereotypes. All these elements are in line with the literature [

17,

27,

28].

The difference between the factors emerging from our study and our reference articles can also be explained by the fact that in our final analysis we no longer had any of the items correlated with the “Permissiveness” factor initially present in the study by Chappel et al. Some of those items were not included in the “Brief SAAS”, some of which differed from the initial questionnaire, and other items were removed from the “bSAAS” because they were not adapted to our context, such as experimental marijuana use among young people, or were not retained during the 2nd or 3rd stage of the factor analysis leading to the “beSAAS” (See Appendix B).

In relation to the 3

rd factor that we have named “Specialised treatment”, it seems to be well characterised in our study by the 4 items correlated with it (referring to care by specialists and in hospital) and thus seems to be better defined here rather than in previous studies where they were associated with the notions of stereotypes and moralism among other items. Nevertheless it does seem to be stereotypical to believe that the complexity of the situations should be dealt with by the second line of care. Recent studies on opiate use disorders show, on the other hand, that primary care setting is the most appropriate [

29,

30], although this is more controversial for alcohol, even if its role of early detection and intervention is essential [

31]. The fact that in our study this emerges as a factor in its own, in contrast to the two studies mentioned above, is indicative of our target population. Here we can also see the impact of the “hidden curriculum” on medical students, as mentioned by Sc. Mahood in 2011 [

32]. Indeed, in the medical curriculum of our Faculty, the importance and primacy of specialties is regularly emphasised outside the formal curriculum. The training being mainly hospital-centered as well. The fact that general medicine is not sufficiently valued in the learning process is certainly internalised by the students, especially a few months before the final exams and selection for career choice, and may influence these stereotypical representations (these two scores being positively correlated in our study, albeit moderately so).

As for the results of the factor scores, we can see that the characteristics of the subjects with higher scores for stereotype and moralism are similar to those who were in favor of punishing substance use during pregnancy (alcohol/drugs) in our previous study [

17], these 2 items being the most «weighted» in this first factor.

In conclusion, it is interesting to note that the people who enrolled in the SUD training scored lower on stereotypes and moralism compared to those who did not decide to attend, but there wasn’t a statically significant difference in terms of optimism about treatment between the two groups which was a tendency to be in favour. This leads us to the conclusion that in this optional training, we will especially focus on improving their perception of treatment outcomes through the sharing of positive experiences and teaching a vision of recovery and long-term support for this chronic pathology (“care vision”) rather than focusing on curing the individual (“cure vision”) as is commonly taught in medicine. This study also reveals the interest and necessity of making a SUD training program compulsory for all medical students, in addition to the basic SUD education, to improve attitudes, access and quality of care for people with SUD, which all these future caregivers will have to face [

27,

33,

34]. It should be noted, however, that the fact that the people taking part in the training were rather not in favour of specialised treatment for this group can be explained by the way in which this training is offered by the Department of General Medicine and students that are heading for general medicine are the more likely to take part.

Although this study made it possible to validate at least a questionnaire for evaluating representations in French that could be used to evaluate educational systems, it does have certain methodological limitations. Indeed, we were not able to ensure its external validity by measuring its correlation with the basic instrument or other related instruments. Nor have we assessed its reliability in terms of repeatability (test-retest) and reproducibility on other profiles. It would also be useful to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis on the basis of our new 23-item questionnaire (bSAAS) to validate its construct. Further studies could be conducted in the future to do this. It is also a questionnaire filled by the students themselves which has its limits in terms of assessment of students’ attitudes in real practice and may have social desirability bias.

4. Conclusions

The adaptation of the Substance Abuse Attitude Survey to our cultural context and our target population of medical students seems to have good validity and internal consistency. The questionnaire selected, beSAAS with 23 items and its three-dimensional interpretation through 2 axes: affective and cognitive, seems useful and relevant to evaluate the impact of a pedagogical program on students’ representations. This study was able to highlight certain factors influencing stereotypical representations such as age, gender, personal or professional experience with substance use. The factor evaluating the interest of “Specialised treatment” clearly emerged in our study and seems to be explained by our target population and its representations influenced by the formal, informal and hidden curriculum. The study highligthed also interesting findings for improving medical education to provide better care for SUD people. Further studies are needed to complete the validity and reliability of the questionnaire.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

LR contributed to the conception and design of the study, she proceeded to the data collection. She wrote the original draft of the manuscript. She was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. MDW had the lead in the analysis and interpretation of the data and was a major contributor in revising the manuscript. NK intellectually contributed to the study process and CK co-supervised the study and the content. All authors read, commented and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethics Committee of ERASME-ULB hospital; medical board’s approval number: OM 021) on February 25, 2019, ref: P2019/156. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

An informed consent was obtained from all participants who filled out and returned the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Committee of Experts who helped to build the new questionnaire and Sarah Nouwynck for the intellectual input on the Manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Watson H, Maclaren W, Kerr S. Staff attitudes towards working with drug users: development of the Drug Problems Perceptions Questionnaire. Addiction. 2007 Feb;102(2):206-15. [CrossRef]

- Richardson GB, Smith R, Lowe L, Acquavita SP. Structure and longitudinal invariance of the Short Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020 Aug;115:108041. [CrossRef]

- Luty J, Fekadu D, Umoh O, Gallagher J. Validation of a short instrument to measure stigmatised attitudes towards mental illness. Psychiatr Bull 2006;30:25760. [CrossRef]

- Schaler, JA. The Addiction Belief Scale. Int J Addict. 1995 Jan;30(2):117-34. [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K., Greenbaum, M. A., Noke, J. M., & Finney, J. W. (1996). Reliability, validity, and normative data for a short version of the Understanding of Alcoholism Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10(1), 38-44. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg M, Vergara C, Wild-Wesley R, Gruman C. Physicians-in-training attitudes toward caring for and working with patients with alcohol and drug abuse diagnoses. South Med J. 2006 Jan;99(1):28-35. [CrossRef]

- Chappel JN, Veach TL, Krug RS. The substance abuse attitude survey: an instrument for measuring attitudes. J Stud Alcohol. 1985 Jan;46(1):48-52. [CrossRef]

- Chappel JN, Veach TL. Effect of a course on students’ attitudes toward substance abuse and its treatment. J Med Educ. 1987 May;62(5):394-400. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins SJ, Fisher GL, Applegate RL. Factor analysis of the substance abuse attitude survey with college undergraduates. Psychol Rep. 1990 Feb;66(1):331-6. [CrossRef]

- Pinikahana J, Happell B, Carta B. Mental health professionals’ attitudes to drugs and substance abuse. Nurs Health Sci. 2002 Sep;4(3):57-62. [CrossRef]

- Puskar K, Gotham HJ, Terhorst L, Hagle H, Mitchell AM, Braxter B, Fioravanti M, Kane I, Talcott KS, Woomer GR, Burns HK. Effects of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) education and training on nursing students’ attitudes toward working with patients who use alcohol and drugs. Subst Abus. 2013;34(2):122-8. [CrossRef]

- Muzyk AJ, Tew C, Thomas-Fannin A, Dayal S, Maeda R, Schramm-Sapyta N, Andolsek K, Holmer S. Utilizing Bloom’s taxonomy to design a substance use disorders course for health professions students. Subst Abus. 2018;39(3):348-353. [CrossRef]

- Muzyk A, Mullan P, Andolsek KM, Derouin A, Smothers ZPW, Sanders C, Holmer S. An Interprofessional Substance Use Disorder Course to Improve Students’ Educational Outcomes and Patients’ Treatment Decisions. Acad Med. 2019 Nov;94(11):1792-1799. [CrossRef]

- Brief Substance Atittude Survey. Available online: https://medicine.yale.edu/sbirt/curriculum/modules/medicine/brief_substance_abuse_attitude_survey_100733_284_13474_v1.pdf.

- Hoffman A. The support of drug users by general practitioners. 15 years after ... Santé conjugué n°46. Fédérations des Maisons Médicales. 2008;46:8-10.

- Ketterer F, Symons L, Lambrechts M-C, Mairiaux P, Godderis L, Peremans L, et al. What factors determine Belgian general practitioners’ approaches to detecting and managing substance abuse? A qualitative study based on the I-Change Model. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:119. [CrossRef]

- Richelle L, Dramaix-Wilmet M, Roland M, Kacenelenbogen N. Factors influencing medical students’ attitudes towards substance use during pregnancy. BMC Med Educ. 2022 May 2;22(1):335. [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch RL. Exploratory Factor Analysis: Its Role in Item Analysis, Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997; 68:3, 532-560. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. Using Multivariate Statistics (5th ed.). New York: Allyn and Bacon. 2007.

- Bloom, B.S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. Taxonomy ofeducational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.1956.

- Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Com-plete edition). New York: Longman. 2001.

- ULB Gender Report. Available from: https://www.ulb.be/fr/egalite-des-genres/dernier-rapport-genre-disponible-rapport-2020-2021.

- Burgess A, Oates K, Goulston K. Role modelling in medical education: the importance of teaching skills. Clin Teach. 2016 Apr; 13(2):134-7. [CrossRef]

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modelling--making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ. 2008 Mar 29;336(7646):718-21. [CrossRef]

- Kidd JD, Smith JL, Hu MC, Turrigiano EM, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Levin FR. Medical Student Attitudes Toward Substance Use Disorders Before and After a Skills-Based Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Curriculum. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020 Jun 30;11:455-461. [CrossRef]

- Sarikhani, Y., Shojaei, P., Rafiee, M. et al. Analyzing the interaction of main components of hidden curriculum in medical education using interpretive structural modeling method. BMC Med Educ 20, 176 (2020). [CrossRef]

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Jul 1;131(1-2):23-35. [CrossRef]

- Goodyear K, Chavanne D. Sociodemographic characteristics and the stigmatization of prescription opioid addiction. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2):150-5. [CrossRef]

- Rowe TA, Jacapraro JS, Rastegar DA. Entry into primary care-based buprenorphine treatment is associated with identification and treatment of other chronic medical problems. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:22. [CrossRef]

- Buresh M, Stern R, Rastegar D. Treatment of opioid use disorder in primary care. BMJ. 2021 May 19;373:n784. [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, S.A., Conigrave, J.H., Saitz, R. et al. Evidence based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 21, 260 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mahood SC. Medical education: Beware the hidden curriculum. Can Fam Physician. 2011 Sep; 57(9):983-5. PMID: 21918135; PMCID: PMC3173411.

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(1):39-50. [CrossRef]

- Wood E, Samet JH, Volkow ND. Physician education in addiction medicine. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23;310(16):1673-4. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

bSAAS: factors, weights, eigenvalues and explained variance.

Table 1.

bSAAS: factors, weights, eigenvalues and explained variance.

| Items |

Factor I: Stereotypes and moralism |

Factor II: Treatment optimism |

Factor III: Specialised treatment |

| Drug addiction is associated with a weak will |

0.60 |

|

|

| A drug dependent person cannot be helped until he/she has hit rock bottom |

0.39 |

|

|

| Drug abusers should only be treated by specialists in that field |

|

|

0.44 |

| A physician who has been addicted to narcotics should not be allowed to practice medicine again |

0.36 |

|

|

| A drug addicted person who has relapsed several times probably cannot be treated |

|

-0.37 |

|

| Long-term outpatient treatment is necessary for the treatment of drug addiction |

|

0.30 |

|

| Paramedical professionals (psychologists, nurses, social workers,…) can provide effective treatment for drug abusers |

|

0.43 |

|

| Paraprofessional counselors (trained volunteers, previous drug users) can provide effective treatment for drugs abusers |

|

0.40 |

|

| Drug addiction is a treatable illness |

|

0.46 |

|

| Group therapy is very important in the treatment of drug addiction |

|

0.53 |

|

| A hospital is the best place to treat a drug addict |

|

|

0.51 |

| Most drug dependent persons are unpleasant to work with as patients |

0.38 |

|

|

| Pregnant women who use drugs should be punished |

0.76 |

|

|

| Coercive pressure, such as threat or punishment, is useful in getting resistant patients to accept treatment |

0.48 |

|

|

| Alcoholism is associated with a weak will |

0.65 |

|

|

| An alcohol or drug dependent person cannot be helped until he/she has hit rock bottom |

0.44 |

|

|

| Alcohol should only be treated by specialists in that field |

|

|

0.53 |

| A drug addicted person who has relapsed several times probably cannot be treated |

|

-0.45 |

|

| Alcoholism is a treatable illness |

|

0.53 |

|

| Group therapy is very important in the treatment of alcoholism |

|

0.61 |

|

| A hospital is the best place to treat an alcoholic |

|

|

0.56 |

| Most alcohol dependent persons are unpleasant to work with as patients |

0.42 |

|

|

| Pregnant women who use alcohol or other drugs should be punished |

0.76 |

|

|

| Eigenvalues |

4.0 |

1.7 |

1.3 |

| Cronbach’s alpha |

0,80 |

0,71 |

0,64 |

| % of variance explained |

40.3 |

17.1 |

12.6 |

| % of total variance explained: 70.0 |

Table 2.

Factor scores$ according to subject characteristics.

Table 2.

Factor scores$ according to subject characteristics.

| Variable |

|

Stereotype and moralism |

|

Optimism about treatment |

|

Specialised care |

|

| |

n (%) |

Mean (SD) |

Pa

|

Mean (SD) |

P |

Mean (SD) |

P |

| Total |

615 (100) |

2.07 (0.55) |

|

2.94 (0.40) |

|

2.55 (0.67) |

|

Age (years)

< 25

25-29

30 and over |

327 (54.8)

242 (40.5)

28 (4.7) |

2.04 (0.51)

2.09 (0.56)

2.28 (0.62) |

0.025b

|

2.93 (0.39)

2.96 (0.39)

2.85 (0.42) |

0.347 |

2.54 (0.65)

2.53 (0.68)

2.67 (0.66) |

0.594 |

Type

F

M |

390 (65.1)

209 (34.9) |

2.04 (0.53)

2.14 (0.56) |

0.037 |

2.94 (0.38)

2.94 (0.43) |

0.885 |

2.59 (0.66)

2.47 (0.68) |

0.035 |

Maternal education level

Low

Medium

High |

48 (8.3)

110 (19.0)

421 (72.7) |

2.12 (0.53)

2.10 (0.60)

2.06 (0.52) |

0.438b

|

2.96 (0.35)

2.92 (0.39)

2.95 (0.40) |

0.684 |

2.16 (0.64)

2.06 (0.54)

2.06 (0.52) |

0.460 |

Subject-parent origin

Belgium

Mixed BE

Mixed BHE

Europe

Outside Europe |

280 (47.6)

86 (14.6)

53 (9.0)

99 (16.8)

70 (11.9) |

2.03 (0.52)

2.00 (0.54)

2.08 (0.49)

2.09 (0.63)

2.29 (0.52) |

0.005c

|

2.93 (0.39)

2.93 (0.37)

2.88 (0.44)

2.98 (0.40)

2.98 (0.39) |

0.526 |

2.58 (0.65)

2.42 (0.58)

2.52 (0.65)

2.46 (0.72)

2.75 (0.73) |

0.015d

|

Substance consumption

No

Cannabis

Multiple |

331 (55.8)

190 (32.0)

72 (12.1) |

2.12 (0.53)

2.01 (0.56)

2.03 (0.54) |

0.065 |

2.94 (0.38)

2.94 (0.38)

2.95 (0.46) |

0.970 |

2.60 (0.68)

2.48 (0.66)

2.53 (0.62) |

0.123 |

SUD in the entourage

No

Alcohol

Cannabis

Alcohol-cannabis

Other drugs |

222 (37.8)

83 (14.1)

41 (7.0)

95 (16.2)

147 (25.0) |

2.09 (0.54)

2.08 (0.50)

2.04 (0.50)

2.05 (0.52)

2.09 (0.61) |

0.958 |

2.92 (0.40)

2.99 (0.39)

2.91 (0.35)

2.91 (0.38)

2.96 (0.41) |

0.561 |

2.58 (0.69)

2.56 (0.61)

2.65 (0.57)

2.49 (0.59)

2.52 (0.73) |

0.638 |

Health perception

Excellent

Very good

Good-satisfactory |

111 (27.7)

191 (47.6)

99 (24.7) |

2.02 (0.53)

2.07 (0.55)

2.01 (0.52) |

0.617 |

2.97 (0.47)

2.93 (0.38)

2.99 (0.36) |

0.466 |

2.60 (0.70)

2.61 (0.63)

2.49 (0.71) |

0.310 |

Choice of medical specialty

MG

Mint

Ped

Gyn

Other |

159 (25.9)

78 (12.7)

41 (6.7)

41 (6.7)

296 (48.1) |

2.08 (0.50)

2.05 (0.60)

2.06 (0.52)

1.96 (0.53)

2.08 (0.56) |

0.752 |

2.96 (0.38)

2.94 (0.38)

2.92 (0.36)

3.02 (0.36)

2.91 (0.42) |

0.384 |

2.44 (0.65)

2.54 (0.68)

2.59 (0.68)

2.46 (0.63)

2.61 (0.67) |

0.103 |

Contact with SUD people

No

Hospital

Multiple

Specific contact

MG |

23 (3.9)

203 (34.0)

300 (50.3)

49 (8.2)e

22 (3.7) |

2.32 (0.63)

2.12 (0.58)

2.06 (0.51)

1.82 (0.48)

2.10 (0.50) |

0.001e

|

2.84 (0.58)

2.92 (0.39)

2.97 (0.36)

2.92 (0.45)

2.94 (0.42) |

0.503 |

2.66 (0.58)

2.64 (0.64)

2.50 (0.69)

2.58 (0.64)

2.34 (0.63) |

0.093 |

SUD Training subscription

No

Yes |

553 (89.9)

62 (10.1) |

2.09 (0.54)

1.92 (0.55) |

0.024 |

2.93 (0.40)

2.99 (0.36) |

0.280 |

2.57 (0.66)

2.38 (0.68) |

0.031 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).