1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is projected to be the second leading cause of cancer death by 2030 after lung cancer in the United States[

1]. The management of pancreatic cancer is multifaceted, comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, with the choice of treatment mainly depending on the type and stage of the disease [

2]. The benefits of chemotherapy, the most common systemic therapy for various cancers, have been masked by high drug toxicities, adverse reactions, and drug resistance [

3,

4]. The cancer burden worldwide has necessitated modern approaches that ensure safer, targeted, and efficient delivery of drugs to the tumor site. One such approach is using nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery to overcome the challenge of low drug concentration reaching tumors [

5,

6].

Nanoparticles range in size from between 1 and 1000nm [

7]. Their composition includes phospholipids and other polymeric materials [

8]. The size and design of nanoparticles increase the ease at which they permeate tumors, enhancing the deposition of a higher concentration of therapeutic agents in the tumors. Nanoparticles work by targeting cancer cells, tumor environment, or the immune system [

7]. Liposomes, dendrimers, and polymeric micelles are nanoparticles used to treat cancer and other disease conditions by acting as carriers for various drugs [

4]. These nanoparticles offer the advantage of increased water solubility of drugs, targeted drug delivery, improved stability, better circulation time, and benefits in tumor imaging, ultimately making them suitable carriers in cancer therapy [

3,

4]. Nanoparticles have been around for over five decades. However, their use in cancer treatment has become more popular over the last three decades.

Liposomes, the first nanoparticle to be approved as a carrier in cancer therapy, were discovered about six decades ago [

4,

9]. Liposomes are spherical vesicles that comprise lipid concentric bilayers enclosing an aqueous core [

10]. The lipid bilayer of liposomes resembles the bilayer of mammal cells, facilitating better interaction and cellular uptake [

3]. Liposomes are classified based on their size and number of bilayers as either small or large unilamellar or multilamellar vesicles. [

7] Some characteristics of liposomes that make them ideal candidates as nanocarriers are that: they are biodegradable, biocompatible, allow for the incorporation of both aqueous and lipid-soluble drugs, sustained drug action, and targeted drug delivery [

11]. Doxil (liposomal-based Doxorubicin) was the first liposomal anticancer formulation approved by the Food and Drugs Authority (FDA) for treating AIDS-related Kaposi Sarcoma and ovarian cancer [

12]. The introduction of this novel formulation generated a heightened interest in liposome research which subsequently led to the development and approval of other liposomal formulations. Such formulations include Daunoxome – Daunorubicin (indicated for AIDS-related Kaposi Sarcoma and Acute Myeloid Leukemia), Myocet-Doxorubicin (indicated for metastatic breast cancer), and Onivyde -Irinotecan (indicated for metastatic pancreatic cancer) [

3].

Some liposomal formulations are undergoing clinical evaluation for cancer treatment. An example is EndoTAG-1 (liposomal Paclitaxel) for treating pancreatic cancer (the third deadliest cancer in the United States) [

9,

13]. Liposomes have been used in several studies as nanocarriers to determine the efficacy of novel and standard cancer drugs in various tumors [

10]. Matsumoto et al. demonstrated the superior cytotoxic effects of a novel liposomal Gemcitabine formulation (FF-10832) in mouse xenograft tumor models over the unmodified drug in pancreatic cancer cells [

14]. In that study, liposomal Gemcitabine significantly reduced tumor size in mice with Capan-1 and BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer tumors compared to Gemcitabine Hydrochloride [

14]. Also, Xu et al. demonstrated the potential of pH-sensitive liposomes in overcoming Gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer management [

15]. In addition, Inkoom and colleagues also demonstrated the effectiveness of Gemcitabine stearate nanoparticle in suppressing tumors using patient-derived xenograft mouse models [

16].

An approach to further increase the cytotoxicity of liposomes in tumors is by conjugating to large molecular weight compounds such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) [

10,

17]. The concept behind this approach is the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect (EPR), in which high–molecular weight compounds accumulate in tissues with high vascular permeability, such as cancer tissues [

10]. This accumulation results in increased bioavailability, sustained drug action, and higher cytotoxic effects. Kim et al. conducted a study comparing the efficacy of free cromolyn to pegylated liposomal cromolyn(PEG-lipo-cro) in BXPC-3 tumor-bearing mice [

18]. PEG-lipo-cro significantly inhibited tumor growth compared with free cromolyn (p < 0.01) due to an increase in the compound's half-life leading to higher cytotoxicity [

18].

Many novel cancer drugs never make it to clinical use due to differences in efficacy and safety data between animal and human studies. Traditional cancer models or 2-dimensional (2D) models have the major shortcoming of the inability to mimic the actual tumors effectively. This has led to inconsistencies in in-vitro, in-vivo, and human studies data, subsequently accounting for the deficient number of cancer drugs that make it to clinical use. Organoids were introduced into cancer research to mimic patients' tumors better and increase the likelihood of more drugs moving from clinical trials to bedside treatments [

19]. Cancer organoids are 3-dimensional (3D) models of cancer cells that mimic the morphological and histopathological features of patient tumors [

20,

21] Organoids have improved the understanding of the heterogeneous nature of tumors and also somewhat overcome the shortcomings of 2-dimensional (2D) cancer models [

20]. For example, pancreatic cancer organoids have been used to demonstrate the different sensitivities to various chemotherapeutic agents (76 drugs), initially undocumented in 2D models, further substantiating the benefits of organoids in personalized therapy [

22].

The shortcoming of standard chemotherapeutic agents has led to increasing research involving modified forms of these drugs. One common approach is conjugating long-chain hydrocarbons to traditional medicines leading to the formation of lipophilic prodrugs [

23,

24]. The conjugation confers properties such as increased membrane permeability, bioavailability, and extended duration of action, ultimately leading to higher cytotoxic effects [

16]. The present study details the design of a liposomal formulation (LnP), cell viability studies with 5-FU analog previously synthesized (1,3 bistetrahydrifuran-2yl-5-FU (MFU)) [

25] against Panc-1 and MiaPaCa-2 cancer cells using 2D and 3D models (spheroids and organoids) respectively, tumor efficacy studies using patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse model with ectopic tumors and evaluating the tissue biodistribution of Gd-Hex-LnP

in vivo.

3. Discussion

Pharmaceutical nanoparticle delivery systems are ideal for transporting anti-cancer drugs and reducing unwanted distribution and side effects to healthy cells. These nanoparticles protect anti-cancer drugs from first-pass metabolism and enzymatic degradation. In addition, these delivery systems generally improve the drug's enhancement properties, prolong systemic circulation, and increase drug entrapment and loading capacity [

3,

34]. Furthermore, for cancer, nanoparticles as anticancer drug delivery systems are generally designed to improve, for example, high drug loading capacity, prolonged systemic circulation, the ability of the nanoparticle to accumulate specifically in the required pathological zone, and the nanoparticle’s ability to resist degradation in high environmental temperatures [

35].

To resolve some of the issues mentioned above, we synthesized and characterized MFU from our previous studies [

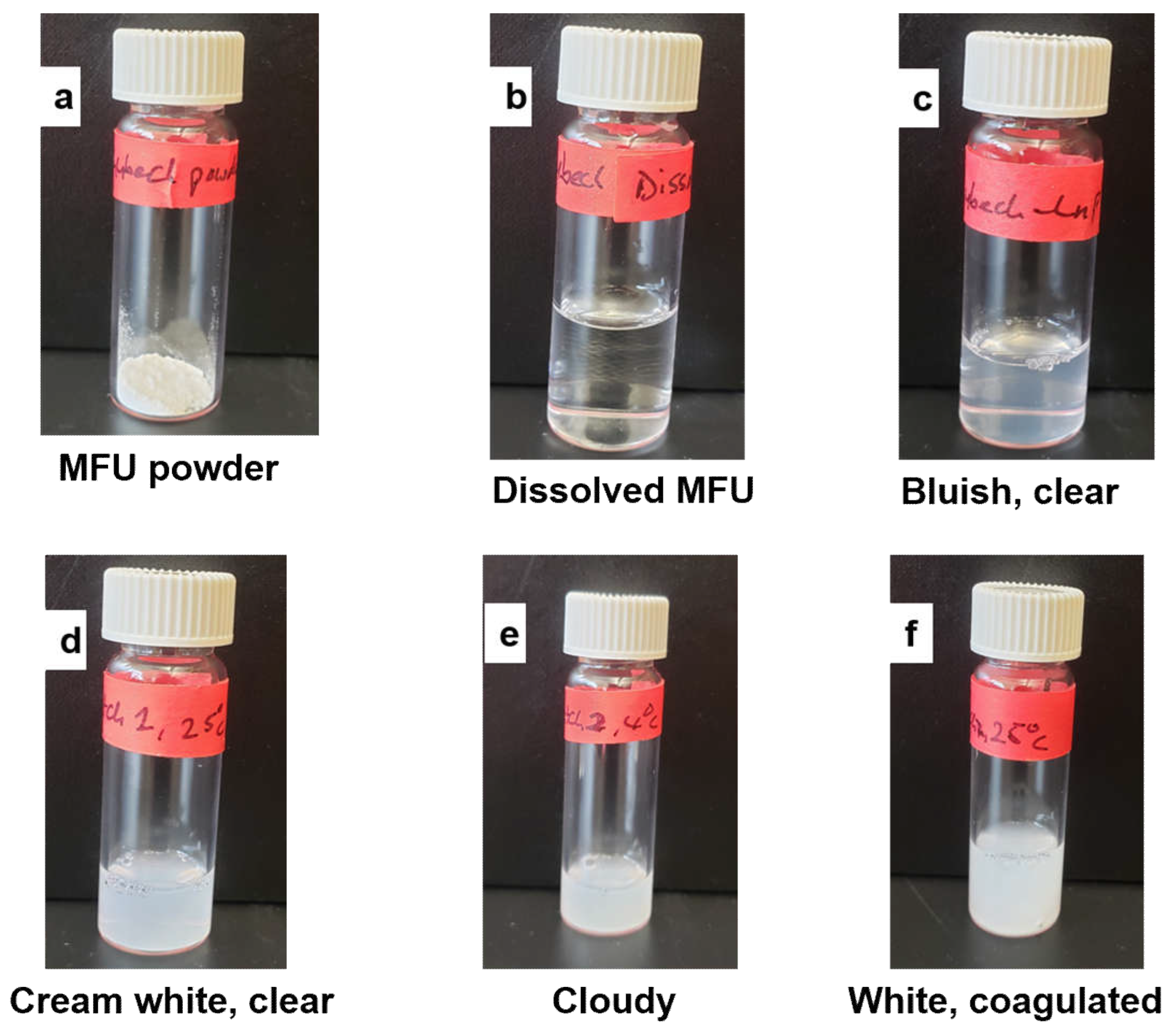

25], loaded it to LnP (together called zhubech) with the surface modified with/ DSPE-PEG_2000 to enhance stability in systemic circulation and improve the therapeutic efficacy of MFU. One of the unique features of zhubech is that it is very stable at room temperatures; hence does not need any particular temperatures for storage [

36]. Also, LnP was prepared with DPPC; MPPC; Cholesterol, and DSPE-PEG_2000, and particle size <200nm has been reported to have a considerable decrease in the leakage of entrapped lipophilic content like MFU due to conjugation into the lipids [

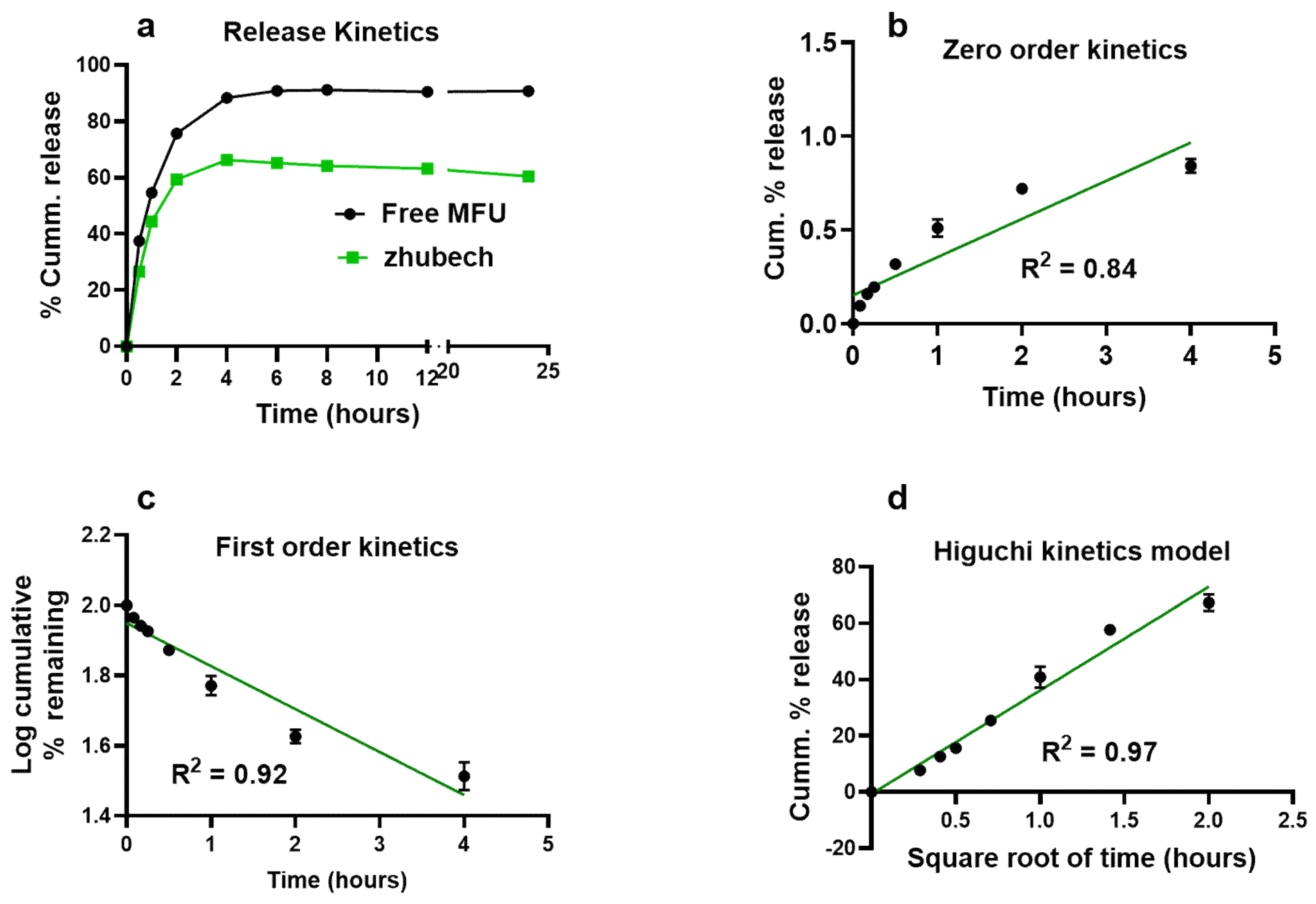

37]. The release characteristics of MFU from zhubech follows the Higuchi release model suggesting that the formulation zhubech behaves like a matrix system with release characterized by diffusion [

38]. This assumes that the initial drug concentration in the matrix is much higher than drug solubility, with drug diffusion taking place only in one dimension, drug particle much smaller than system thickness and matrix swelling and dissolution are negligible. Further assumptions are that drug diffusivity is constant with perfect sink condition in place [

39].

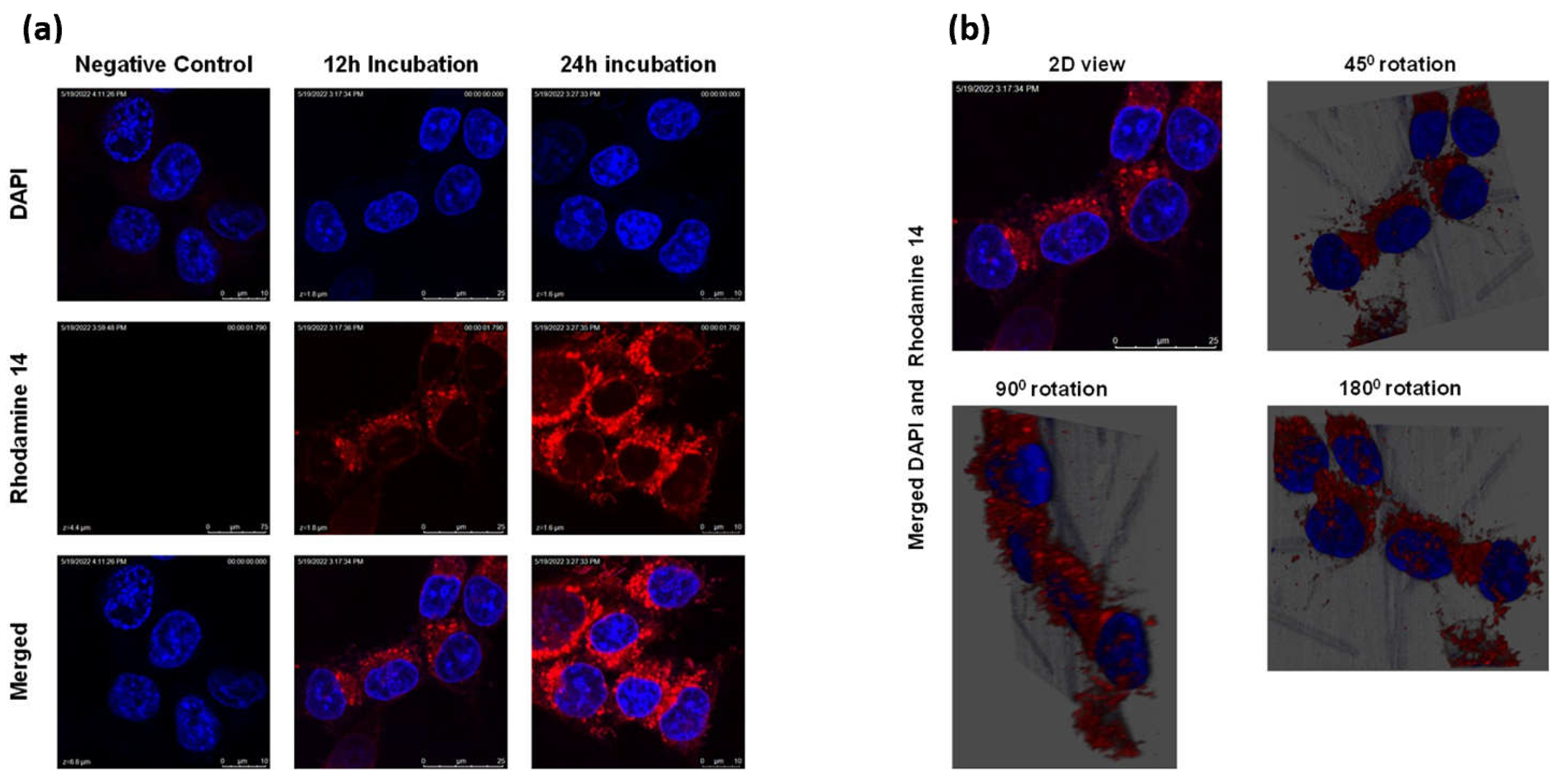

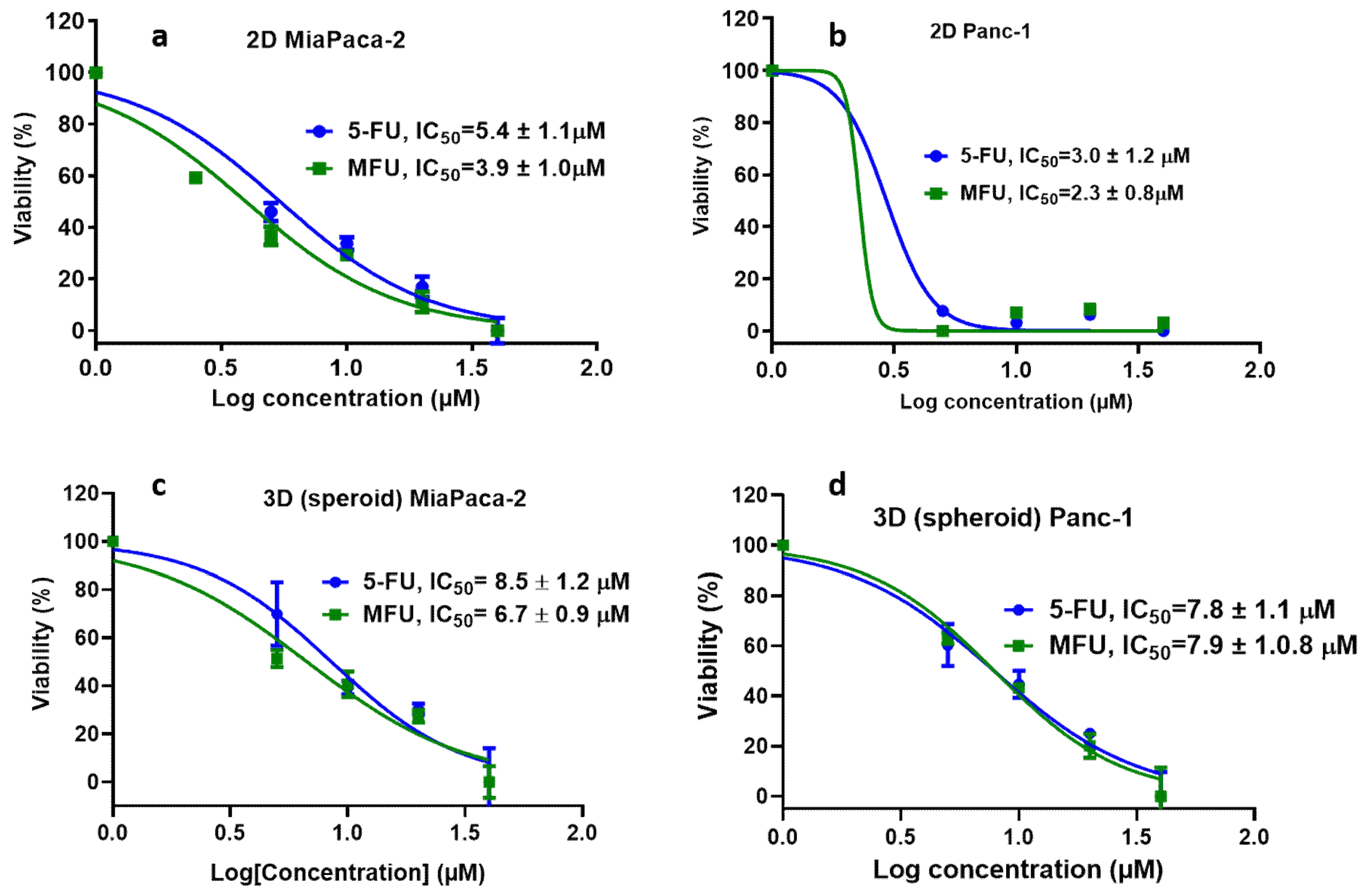

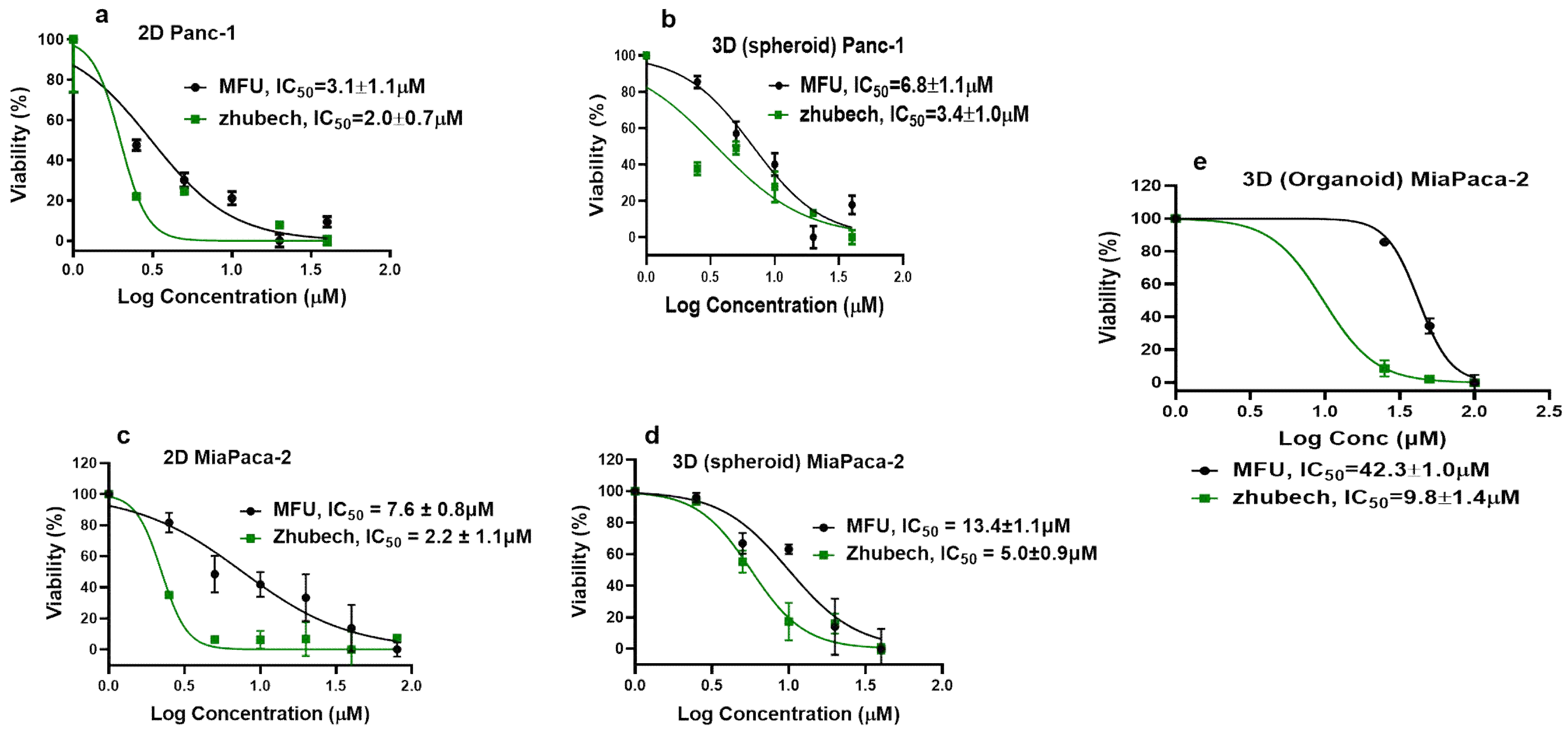

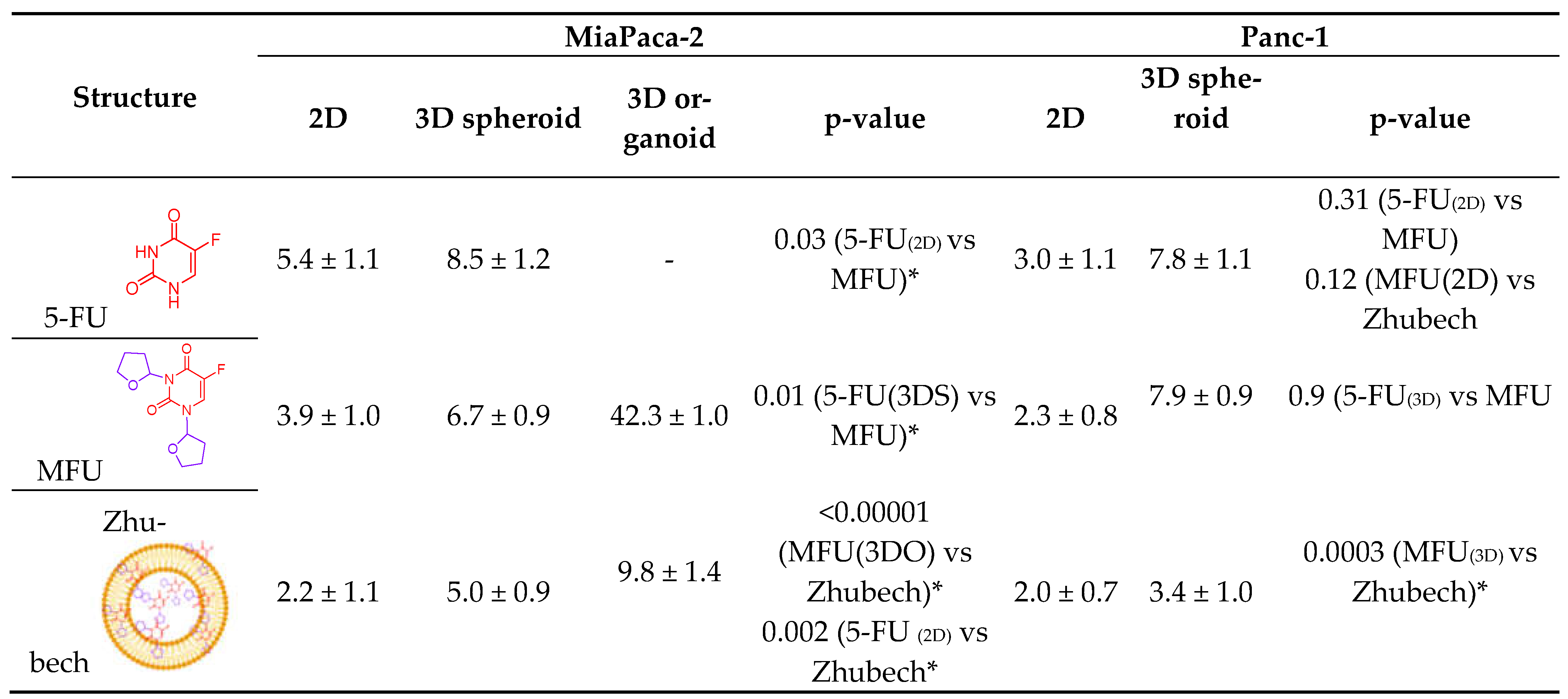

In in vitro cell viability study, we assessed the effects of MFU and 5-FU on MiaPaca-2 and Panc-1 cell lines in 2D and 3D spheroid models which demonstrated superiority of MFU compared to the parent drug 5-FU in cytotoxicity. We also demonstrated the effects of MFU and zhubech on Panc-1 (2D and 3D spheroid models) and MiaPaca-2 (3D organoid model) cell lines. Cells were exposed to the blank liposome (LnP), MFU, or zhubech for 48 hr, a sufficient period to assess inhibition. LnP was well tolerated by Panc-1 cells in 2D and 3D spheroid cell cultures, and MiaPaca-2 3D organoids. MFU, and zhubech showed a dose-dependent inhibitory effect with zhubech demonstrating a more significant reduction in cell viability in all culture models. This suggests a higher cellular uptake of liposomal form leading to a greater internalization of MFU.

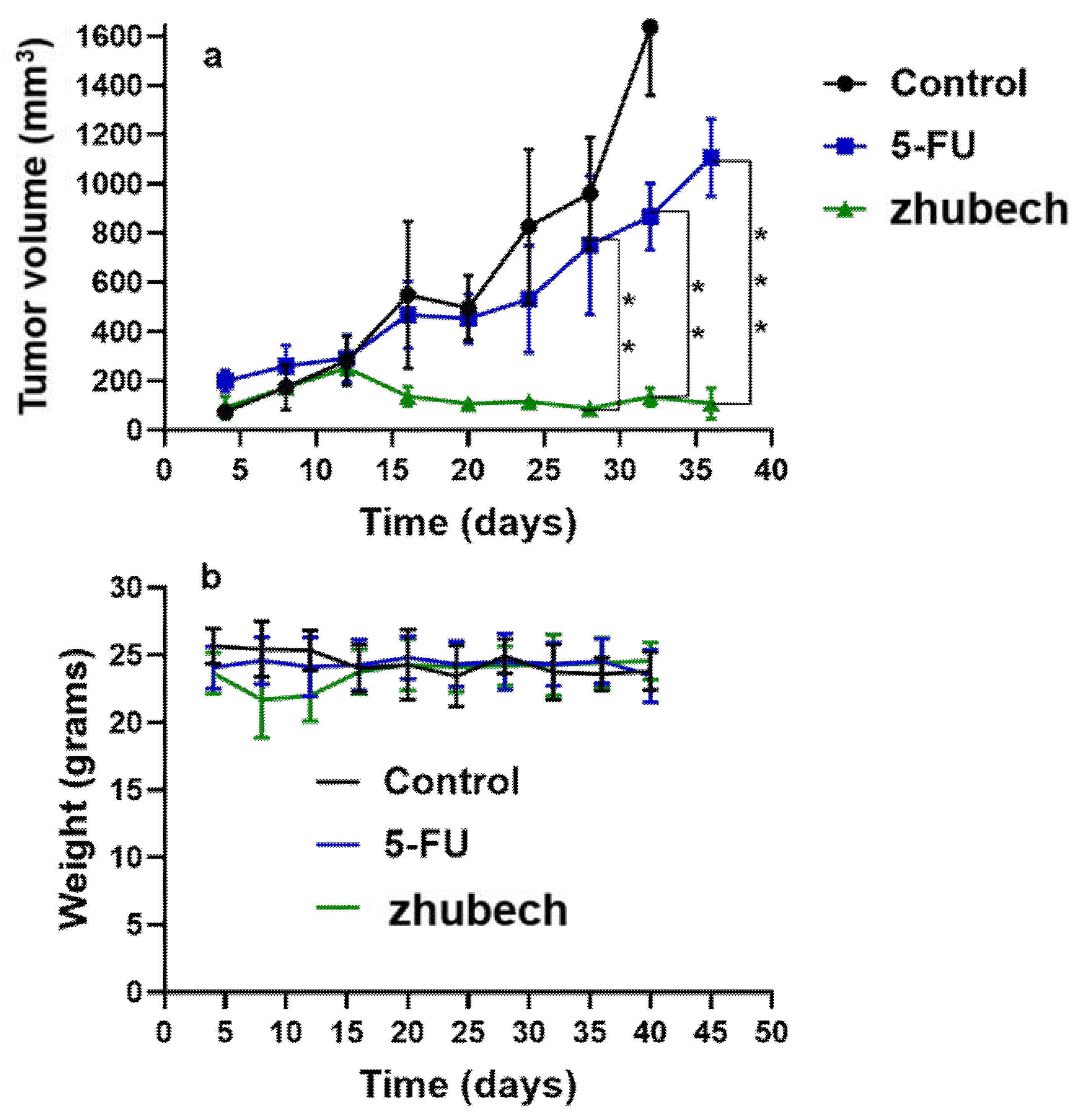

In vivo anti-tumor activity of zhubech after the 15th day exhibited a significant inhibition of tumor growth compared with 5-FU. There was a significant decrease in tumor volume for zhubech-treated mice (108 ± 13.5 mm3) compared to 5FU-treated mice (1107 ± 116.2 mm3) at the end of the studies (P-value<0.001). This extraordinary tumor efficacy of Zhubech could be explained by three major factors: i) absence of free NH2-group on free MFU which rendered the dihydropyrimidnne dehydrogenase (DPD) enzyme ineffective to metabolize zhubech. This event most likely allowed for prolong circulation, increased bioavailability and improved therapeutic efficacy of MFU and ii) conjugation of THF to 5-FU may have imparted some degree of lipophilicity to MFU which may have facilitated its delivery to cancer cells and iii) probably loading MFU in zhubech might have increased the half-life, increase permeability to tumor site and improved stability in circulation.

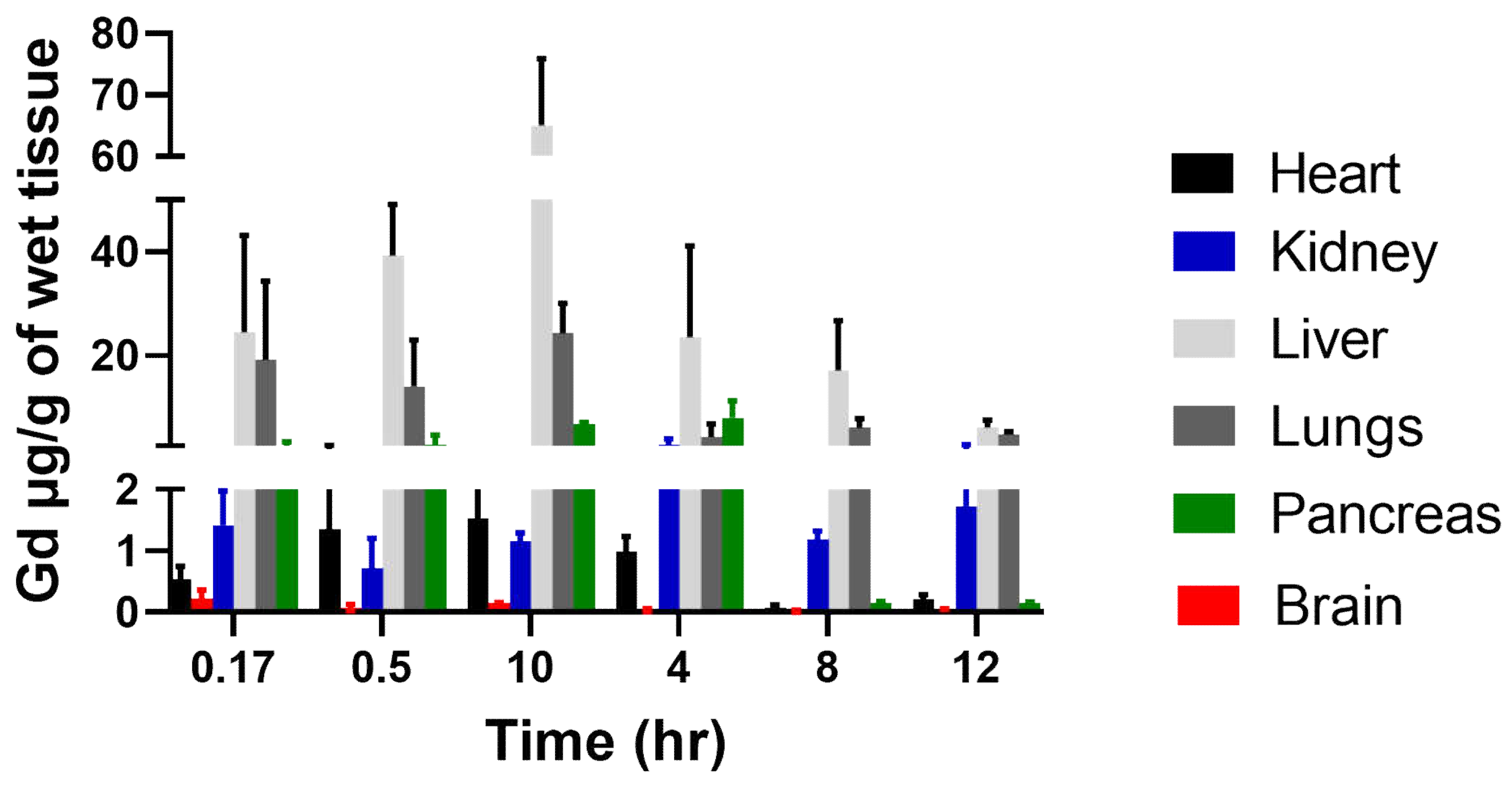

Nanocarriers are very useful in drug delivery because of their ability to alter the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. For the biodistribution study, Gd-Hex delivered to a mouse by LnP (Gd-Hex-LnP) was significantly higher in the liver, lungs, and pancreas after 1h and 4 h, respectively. The mechanism of delivery by LnP could be attributed to higher enhanced permeability and retention effect where nanoparticle size carriers are distributed in tissues with rich blood supply and retained there at high concentrations for a long period. In contrast, free drugs are not retained but return to circulation by diffusion [

40,

41,

42]. In addition, environmental temperature did not influence the stability of zhubech (

Table 2), possibly improving delivery of Gd-Hex to tissues [

43,

44].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethyleneglycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000), Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), 1-Myristoyl-2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (MPPC), Cholesterol (chol), lipids were all purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA). All the chemicals, including 5-FU and reagents, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Pca cell lines (Panc-1 and MiaPaca-2) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All other chemicals used were of an analytical reagent grade.

4.2 Preparation of stealth LnP

LnP was prepared by thin film hydration technique [

45]. Briefly, MPPC, DPPC, Chol, and DSPE_PEG -2000 was dissolved in 2 mL of chloroform and mixed at a molar ratio of (25:50:20:5) in a round bottom flask. The chloroform was removed using a rotary evaporator at 75° C for 30 minutes until a thin, dry film was formed. Samples were then placed under a high vacuum where the lipid sample formed a "swollen" film that was held under vacuum for 2-3 hours to remove residual chloroform. These dried, swollen lipid films were hydrated with the PBS in which the drug is dissolved and held at 65-70 °C (slightly above the transition temperature) and homogenized using a NanoDeBEE at a pressure of 30000 PSI for 20 cycles—sonicated for 5-10 minutes. Then the formulation was extruded 10 times through stacked polycarbonate filters with a pore size of 100 nm (Nuclepore Track-Etch membrane) at 65-70 °C using an extruder (Avanti®, Birmingham, AL).

4.3 Physical characterization:

4.3.1 Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential determination

The particle size (hydrodynamic diameter) of liposomes was determined by dynamic light scattering using a particle sizer (NICOMP ™ 380 ZLS, Santa Barbara, CA). All measurements were performed at room temperature. Before each measurement, samples were diluted with deionized water at a ratio of 1:10. Polydispersity index (PDI) and Zeta potential were measured using the same instrument [

46]. Zhubech formulations were divided into 3 batches (corresponding to duration of study) and kept at different temperatures for modified real time and accelerated stability studies at 1,2 and 3 months measuring hydrodynamic diameter, MFU content in zhubech and physical appearance [

28,

47].

4.3.2: HPLC analysis

The Waters HPLC alliance e2695 system with a PDA detector was used to analyze MFU at a wavelength of 270 nm. The mobile phase was water (pH adjusted to 2.5 with phosphoric acid) and methanol at a ratio of 90:10 (v/v). The mobile phase flow rate was maintained at 1.0 ml/min. MFU retention time was 19.6 minutes. The injection volume was 50 μl. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using empower software (Waters Corporation, MA). The calibration curve (peak area vs. concentration) was generated over the range of 1–100 μg/ml and was found to be linear with a correlation coefficient of 0.9998. Before analysis, the reverse phase column was equilibrated with the mobile phase made up of water and methanol in a ratio of 90:10, and the pH was adjusted to 2.5. Isocratic elution was performed throughout the entire analysis, including internal standards.

4.3.3 Entrapment Efficiency:

The supernatant obtained after centrifugation of Zhubech was analyzed for unentrapped MFU by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Waters, USA) using a C18 column. The mobile phase consisted of H20 at a pH of 2.5 and methanol at v/v of 90:10. The injection volume was 50 μL, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min. The EE% was calculated according to the equation:

4.3.4. Release Studies:

The release of MFU from zhubech was studied by a dialysis method. The dialysis bags were soaked in distilled water at room temperature for 12 h to activate the dialysis bag and remove the preservative, and then rinsed thoroughly in distilled water.

In vitro release of the MFU from zhubech was performed by dialysis in a dialysis bag (14,000 MW cut off; Sigma-Aldrich) containing 150 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and methanol at a ratio of 3:1 v/v (PBS; pH 5.6). Two bags were prepared containing the Zhubech and the control containing free MFU. Equivalent amounts of Zhubech and free MFU concentrations were added to a dialysis bag. Both bags were prepared and tested together with the liposomal dispersions. The bags were suspended in a suitable solvent flask so that the part of the dialysis bag containing the formulation was immersed in a buffer solution (PBS/methanol). The flask was held on a magnetic stirrer (Matrex), and stirring was maintained at 200 rpm and a] temperature of 37°C. Samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h while maintaining sink conditions throughout [

48].

4.3.5: Release models:

The release kinetics of 5-FU from the heat-sensitive liposomes was investigated to predict the possible mechanism of release using mathematical models. The release order was determined using zero order (Eq.

1a) and the first-order kinetic model, as shown below.

where C0 is the initial amount of drug, C is the % cumulative MFU released (zero order) or first order (Eq. 1b) at time “t,” and K0 is the zero-order release constant, and K1 is the first order release constant.

Korsmeyer-Peppas (Eq.

2) and Higuchi (Eq.

3) models were used to determine whether the release mechanism follows the polymeric system (power law) or Fickian diffusion, respectively, as shown below:

Where Ct/C∞ is the fraction of drug release at time, t, K is the rate constant, and n is the release exponent. While for the Higuchi model, C is the % cumulative MFU release at the time, and t and KH is the Higuchi constant.

4.4 Cell viability Studies:

These in-vitro viability studies were performed on pancreatic and colorectal cancer cell lines. MiaPaca-2 was incubated in DMEM with high glucose, and L-glutamine and Panc-1 were incubated in McCoy 5A modified media, both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PenStrep) and 2.5% 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES). Cells were plated in a T75 flask for culture and later seeded into 96 well plates.

4.4.1. 2D Cell Viability Studies:

MiaPaca-2 and Panc-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/well and incubated in 5% CO2 and a temperature of 37°C. A stock solution of Zhubech and free LnP were prepared in molar concentrations and serially diluted with the growth medium to prepare different concentrations: i.e., 80, 40, 20, 10, and 5μM. All cells were treated with 200 μL of each drug concentration in quintuplicate and incubated for 48h. At the end of the treatment, 20 μL of 0.15% resazurin sodium salt (Alamar blue®) was added and incubated for four hours under optimal conditions (5% CO2, 37 °C). Fluorometric analysis was determined at an excitation wavelength of 560/580 nm and an emission wavelength of 590/610 nm, and the percentage of viable cells per concentration was calculated.

4.4.2. 3D Cell Viability Studies:

MiaPaca-2 and Panc-1 cells were seeded in a special Nunclon Sphera® 96-well plate at a density of 5000 cells/ L, and then 100 μL of fresh complete media was added to obtain 200 μL in each well. Then the plates were centrifuged at 1500 rpm and incubated at 5% CO2 and a temperature of 37°C for 24 hours to allow spheroid formation. During treatment, 100 μl of the supernatant was replaced with the drug in the growth medium prepared as described in 2D viability studies. At the end of the treatment, 50 μl of 0.15% resazurin sodium salt (Alamar blue®) was added to each well and carefully dispersed by pipetting and incubated for 4 h. The drug was then added to the growth medium. Fluorometric analysis was measured as described above.

4.4.3. Organoid Cell Viability:

The MiaPaca-2 cell pellets were suspended in collagen and Matrigel (transglutaminase) mixture (20:1), as previously documented [

49]. Then transfer the cells to a 48 well plates and incubate at 5% CO

2, 37°C for 40 min. The Matrigel (transglutaminase) helps solidify collagen through cross-linking to form organoids. Then 10 μL of the mixture was seeded into the 48 well plates and rested in the incubator for 40 min to solidify. Once the mixture was solidified, it was given to the supplements as media for 24 hours. Allowed the organoid to develop over 48 hours, followed by treatment with Zhubech and free MFU as control over 7 days. Organoids were digested with 0.25% trypsin over 40 minutes, and an MTT assay was used to quantify cell viability.

4.5 Cellular uptake studies:

Panc-1 cancer cells were grown in 6-well plates (with coverslips) at a cell density of 2 × 10

3 for 24 h at 37 °C. The cells were then treated with Rhodamine-labeled LnP in growth media. After 12 and 24 h, Rhodmaine-LnP was removed, and the cells were gently washed twice with PBS. Next, 5 μg/ml of DAPI dye was added for nuclear staining; the cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, then mounted and imaged using Leica SP2 Multiphoton system [

26].

4.6 Animal study

Ethics statements: Eight-week-old mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The mice were housed in a virus-free environment with indoor light and temperature controlled and provided access to food and water ad libitum for one week before treatment started. All procedures with mice were in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. This was approved by the Florida A&M University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tumor transplantation: Tumor tissue was surgically implanted in the left flank of immune-compromised mice as previously described [

50]. A viable portion of resected tissue was isolated immediately following resection of primary pancreatic cancer specimens to minimize critical ischemia time. The pancreatic cancer tissue was then implanted subcutaneously into 8-week-old mice (n=15). Xenografts were allowed to grow to a maximum of 1.5 cm before implantation to the flank of the new host.

Tumor efficacy studies: In this study, mice bearing surgically implanted tumors were randomized into groups as control, 5-FU and zhubech (n = 5/group) once tumor volumes became palpable and reached a range of 70 –100 mm3. Baseline tumor volumes were established, and dosing initiation began with intravenous administration of 40 mg/k 5-FU and zhubech (with 5-FU equivalent doses) twice weekly for 6 weeks. Tumor measurements were performed every other day. Tumor volumes were measured using calipers and calculated using the following equation: V = (L*(W)2)/2, where V is volume (mm3), W(width) is the smaller of two perpendicular tumor axes and the value L (length) is the larger of two perpendicular axes. Tumor growth volumes were calculated for each treatment group.

Euthanization: Carbon dioxide (CO2) flow to the chamber was adjusted to 3 liters per minute for 2 to 3 minutes and observed each mouse for lack of respiration and faded eye color. The CO2 flow was maintained for a minimum of 1 minute after respiration was ceased and followed by decapitation with scissors. The tumors were then incised and prepared for immunohistochemistry studies.

4.6.1. Synthesis of Gadolinium Hexanoate (Gd-Hex) LnP

A mixture of GdCl3 (2.88 g, 10.9 mmol), Hexanoic acid (3.8 g, 32.7 mmol), ammonium hydroxide (4 mL) in H2O (20 mL) was heated at 80˚C for 2h (Figure

a). The white solid was collected, and washed with acetone (20 mL), Et2O (20 mL). The solid was dried under a vacuum for 24h. The same technique for zhubech formulation was used to prepare Gd-Hex-LnP formulation and particle size measured (Supplementary Figure 7).

4.6.2. Tissue biodistribution

Nude mice (n=18) were allowed to acclimatize for one week, followed by studies. Mice were grouped into six groups (n=3 each) corresponding to each time point (10, 30, 60, 240, 480- and 720-minutes). Mice received 0.05mmol/kg Gd-Hex-LnP intravenously through the tail vein and sacrificed at various time points and tissues obtained and weighed.

After weighing, the organ samples were pre-treated with aqua regia (HNO3: HCl) in a 3:1 v/v ratio and allowed to stand overnight in a fume hood; the pre-treated samples were further diluted with 2% nitric acid (70%, v/v) in distilled water, centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min and finally filtered to remove debris [

27]. The final sample solutions were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to determine the quantity of Gd in each sample solution.

Figure 1.

Physical appearance of Zhubech over time. (a) powdered appearance of MFU after synthesis, (b) MFU dissolved in distilled water to form a solution, (c) bluish, clear appearance after formulating Zhubech, (d) cream white, clear appearance of batch1 formulation at all temperatures, (e) cloudy appearance of batches 2 and 3 stored at 4 degrees, and (f) white coagulated appearance of batches 2 and 3 stored at 40 degrees.

Figure 1.

Physical appearance of Zhubech over time. (a) powdered appearance of MFU after synthesis, (b) MFU dissolved in distilled water to form a solution, (c) bluish, clear appearance after formulating Zhubech, (d) cream white, clear appearance of batch1 formulation at all temperatures, (e) cloudy appearance of batches 2 and 3 stored at 4 degrees, and (f) white coagulated appearance of batches 2 and 3 stored at 40 degrees.

Figure 2.

In vitro release kinetics of Zhubech. (a) In vitro cumulative release of MFU from zhubech at 24h, in which free MFU was the control. (b) Release profile of MFU exhibiting zero-order kinetics, the release followed a non-linear pattern with R2=0.84. (c) Release profile of MFU showing first-order kinetics; the release followed an inverse linear pattern with R2=0.92. (d) Release profile of MFU exhibiting Higushi release model, the release shows a linear pattern with R2=0.97.

Figure 2.

In vitro release kinetics of Zhubech. (a) In vitro cumulative release of MFU from zhubech at 24h, in which free MFU was the control. (b) Release profile of MFU exhibiting zero-order kinetics, the release followed a non-linear pattern with R2=0.84. (c) Release profile of MFU showing first-order kinetics; the release followed an inverse linear pattern with R2=0.92. (d) Release profile of MFU exhibiting Higushi release model, the release shows a linear pattern with R2=0.97.

Figure 3.

Cellular uptake of LnP. (a) cellular uptake of Rh0-14-loaded LnP in Panc-1 cells over 12h and 24h with DAPI used as a nuclear stain. (b) 3D view of the colocalization of LnP within the cytoplasm of the cells after 12 h of incubation with Rh0-14-loaded LnP.

Figure 3.

Cellular uptake of LnP. (a) cellular uptake of Rh0-14-loaded LnP in Panc-1 cells over 12h and 24h with DAPI used as a nuclear stain. (b) 3D view of the colocalization of LnP within the cytoplasm of the cells after 12 h of incubation with Rh0-14-loaded LnP.

Figure 4.

In vitro studies comparing the efficiency of 5-FU and free MFU. a) 2D culture of MiaPaca-2 cells, b) 2D culture of Panc-1 cells, c) 3D culture of Miapaca-2 cells and d) 3D culture of Panc-1 cells.

Figure 4.

In vitro studies comparing the efficiency of 5-FU and free MFU. a) 2D culture of MiaPaca-2 cells, b) 2D culture of Panc-1 cells, c) 3D culture of Miapaca-2 cells and d) 3D culture of Panc-1 cells.

Figure 5.

Cell viability: Effects of Zhubech formulation on Panc-1 and MiaPaca-2 cell growth after 48 h exposure. (a) % viability of Panc-1 in 2D culture. (b) % viability of Panc-1 in 3D spheroid culture. (c) % viability of MiaPaca-2 in 2D culture. (d) % viability of MiaPaca-2 in 3D spheroid culture and (e) % viability of MiaPaca-2 in 3D organoid culture (after 7 days of exposure with MFU and Zhubech formulation).

Figure 5.

Cell viability: Effects of Zhubech formulation on Panc-1 and MiaPaca-2 cell growth after 48 h exposure. (a) % viability of Panc-1 in 2D culture. (b) % viability of Panc-1 in 3D spheroid culture. (c) % viability of MiaPaca-2 in 2D culture. (d) % viability of MiaPaca-2 in 3D spheroid culture and (e) % viability of MiaPaca-2 in 3D organoid culture (after 7 days of exposure with MFU and Zhubech formulation).

Figure 6.

In-vivo efficacy of zhubech in PDX mouse model and chronic toxicity. (a) Tumor growth curves of 5-FU and zhubech treated mice bearing pancreatic PDX tumor and (b) body weight during treatment. Asterisks represents level of significance between control and treatment group (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). All data represents mean ± SD, (n=4/group).

Figure 6.

In-vivo efficacy of zhubech in PDX mouse model and chronic toxicity. (a) Tumor growth curves of 5-FU and zhubech treated mice bearing pancreatic PDX tumor and (b) body weight during treatment. Asterisks represents level of significance between control and treatment group (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). All data represents mean ± SD, (n=4/group).

Figure 7.

Biodistribution of Gd-Hex-LnP in different tissues (Heart, Kidney, lungs, brain, liver, and pancreas) at different time points (0.17, 0.5, 1, 4, 8, and 12 hours) after IV injection of 0.05mmol/kg of Gd-Hex-LnP in nude mice. Data represent mean ± SD, number of mice per group = 3.

Figure 7.

Biodistribution of Gd-Hex-LnP in different tissues (Heart, Kidney, lungs, brain, liver, and pancreas) at different time points (0.17, 0.5, 1, 4, 8, and 12 hours) after IV injection of 0.05mmol/kg of Gd-Hex-LnP in nude mice. Data represent mean ± SD, number of mice per group = 3.

Table 1.

Characterization of LnP and Zhubech.

Table 1.

Characterization of LnP and Zhubech.

| |

Lipid composition |

Molar ratio |

Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) |

PDI |

Zeta potential (mV) |

E.E (%) |

| LnP |

DPPC: MPPC: Chol: DSPE-PEG_2000 |

50:25:20:5 |

90.0 ± 0.65 |

0.39 ± 0.01 |

0.02 |

- |

| Zhubech |

DPPC: MPPC: Chol: DSPE-PEG_2000 |

50:25:20:5 |

124.9 ± 3.2 |

0.16 ± 0.005 |

-30.3 ± 12 |

97.2 ± 0.9 |

Table 2.

Physical stability of Zhubech over time

Table 2.

Physical stability of Zhubech over time

| Day |

Temperature |

Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) |

PDI |

MFU content in LnP (%) |

Physical appearance |

| 0 |

25 ± 1.5˚C |

124.9 ± 3.2 |

0.16 ± 0.005 |

97.2 ± 0.9 |

Bluish, clear |

| 30 (Batch 1)

|

4 ± 1˚C |

117 ± 2.0 |

0.18 ± 0.04 |

95.2 ± 2.7 |

Cream white, clear |

| 25 ± 2˚C |

127.4 ± 2.3 |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

93.4 ± 3.7 |

Cream white, clear |

| 40 ± 3˚C |

126.8 ± 0.9 |

0.47 ± 0.06 |

91.9 ± 0.2 |

Cream white, clear |

| 60 (Batch 2)

|

4 ± 1˚C |

129.4 ± 0.6 |

0.27 ± 0.013 |

90.1 ± 1.1 |

Cloudy |

| 25 ± 2˚C |

135 ± 6.1 |

0.63 ± 0.031 |

87.1 ± 2.1 |

White, coagulated |

| 40 ± 3˚C |

142.7 ± 2.5 |

0.36 ± 0.021 |

90.3 ± 4.3 |

Cream white, clear |

| 90 (Batch 3)

|

4 ± 2˚C |

146.7 ± 1.6 |

0.39 ± 0.07 |

71.1 ± 0.8 |

Cloudy |

| 25 ± 2˚C |

162.2 ± 16.0 |

0.42 ± 0.02 |

88.2 ± 3.7 |

White, coagulated |

| 40 ± 3˚C |

169.1 ± 2.1 |

0.15 ± 0.01 |

67.9 ± 6.4 |

Cream white, clear |

Table 3.

Comparing the IC50 values of 5-FU compared to MFU and Zhubech in MiaPaca-2 and Panc-1 cell lines.

Table 3.

Comparing the IC50 values of 5-FU compared to MFU and Zhubech in MiaPaca-2 and Panc-1 cell lines.