Submitted:

08 January 2023

Posted:

10 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

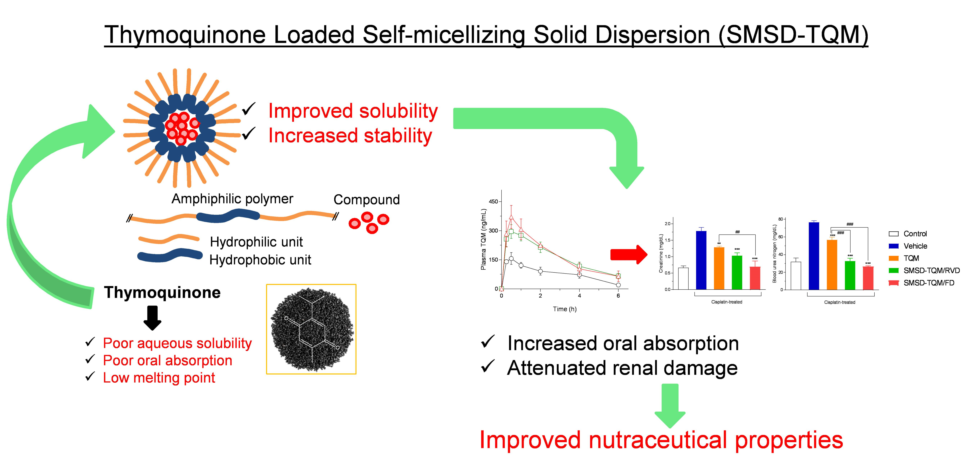

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Standard Curve Preparation and TQM Content Analysis

2.3. Phase Solubility Study

2.4. Preparation of SMSD-TQM

2.5. Dissolution Study

2.6. Surface Morphology

2.7. X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD)

2.8. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.9. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

2.10. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.11. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.12. Storage Stability Study

2.13. Animals

2.14. Pharmacokinetic Studies

2.15. Nephroprotective Effect of TQM Samples

2.15.1. Rat Model of Nephropathy

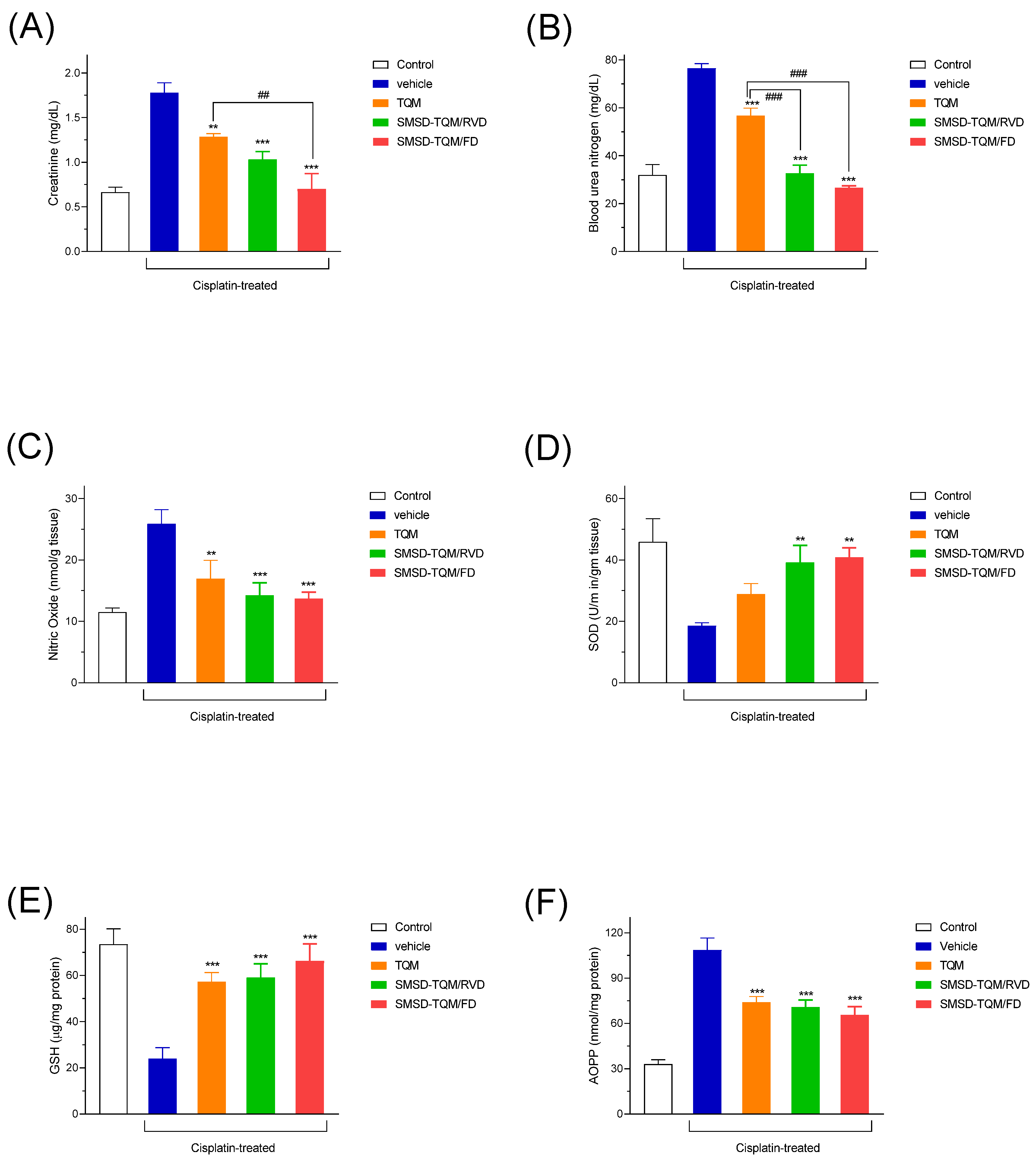

2.15.2. Nephrotoxic Biomarkers

2.15.2.1. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN)

2.15.2.2. Creatinine

2.15.3. Preparation of Tissue Homogenates and Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Markers

2.15.4. Study of Antioxidant Activities

2.15.5. Histopathology Procedure

2.16. Data analysis

3. Result and Discussion

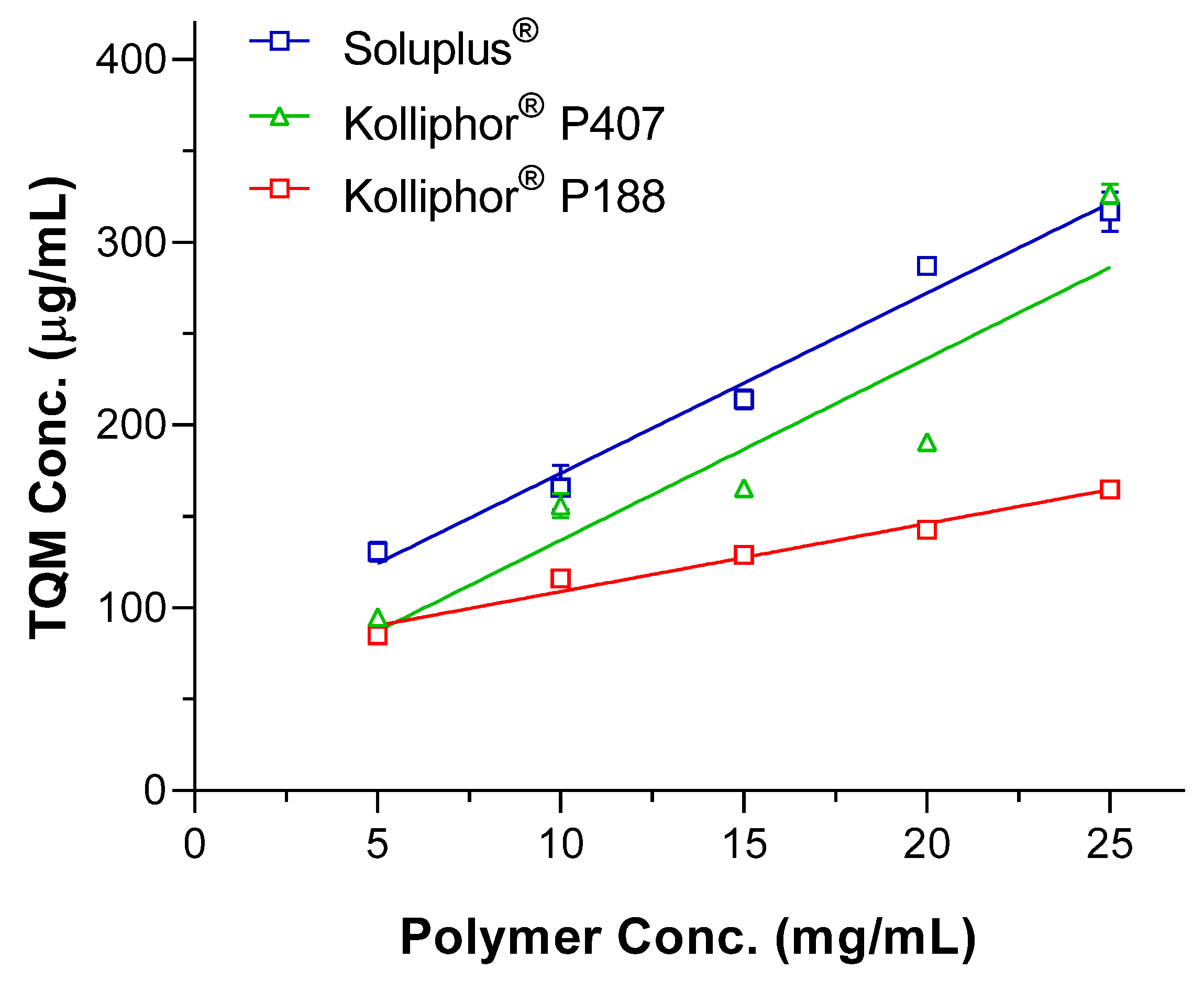

3.1. Selection of a suitable Polymer for SMSD System

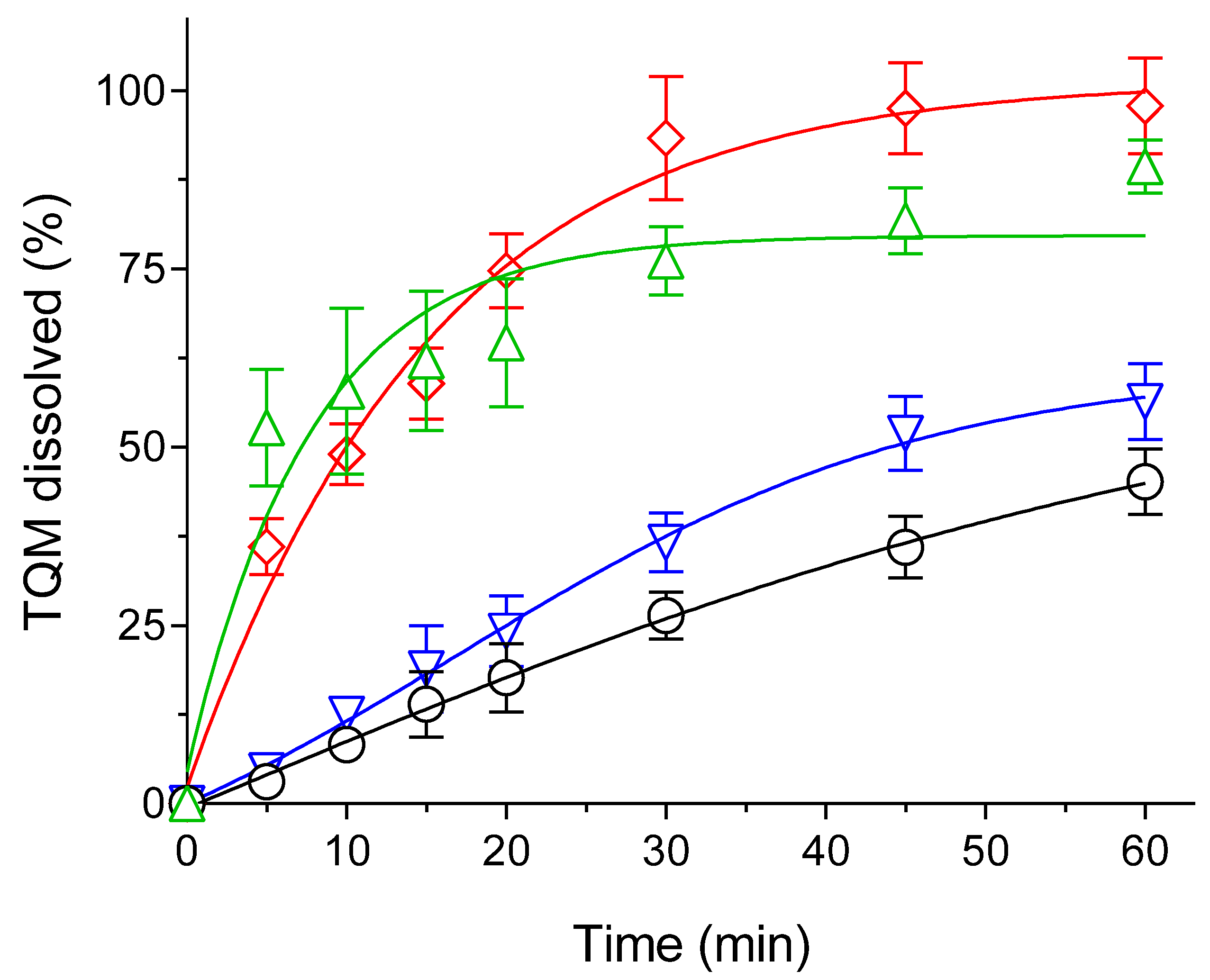

3.2. Optimization of TQM Loading Amounts through Dissolution Studies

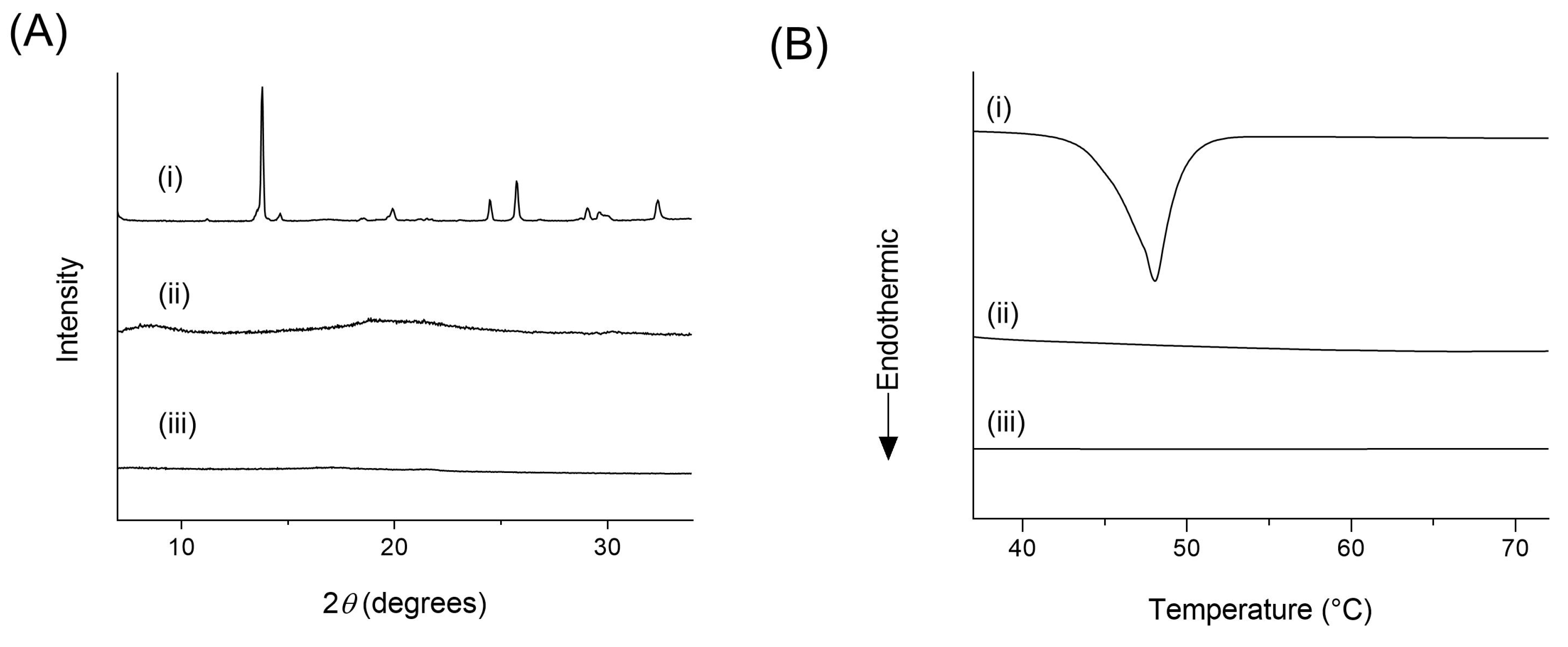

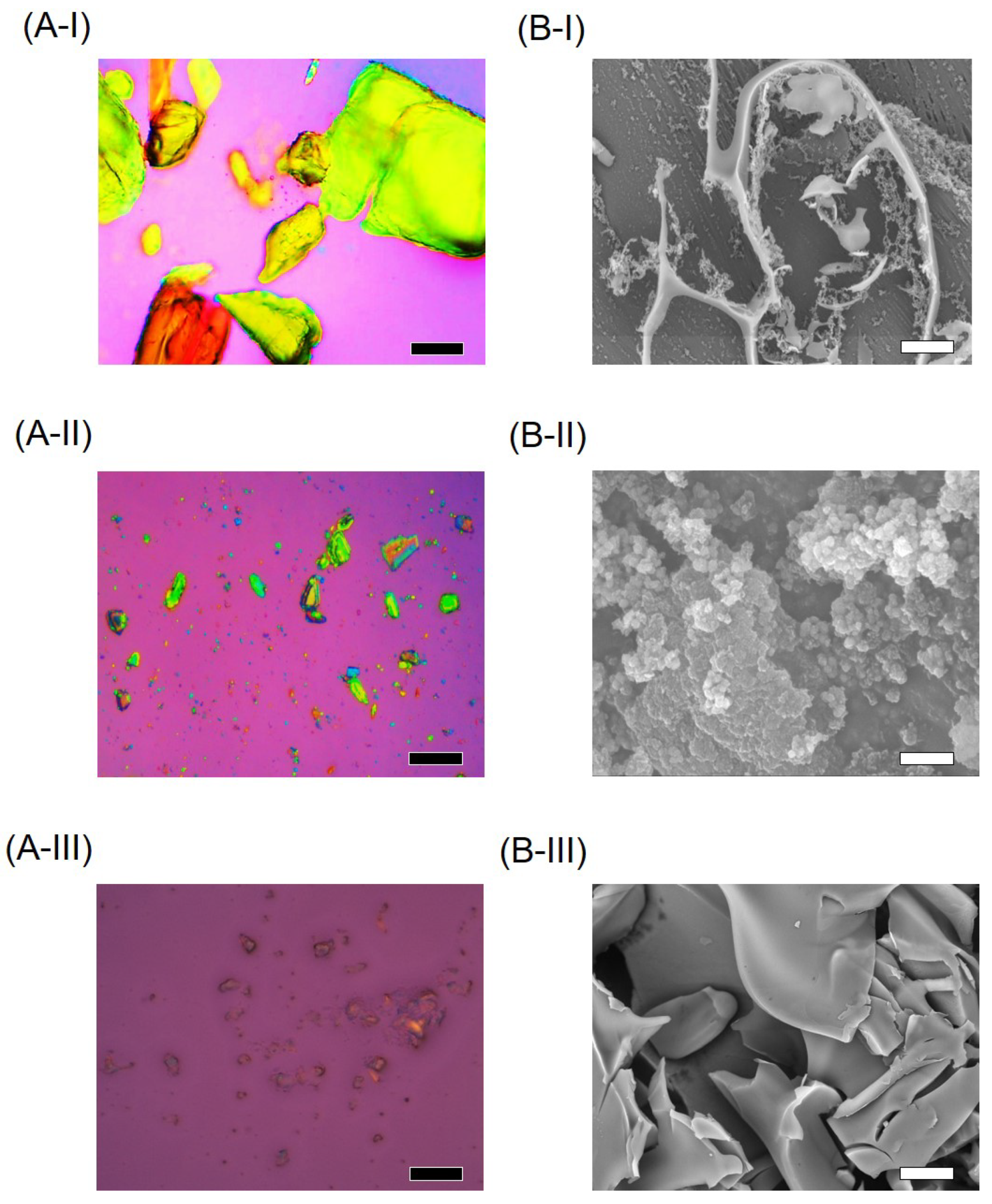

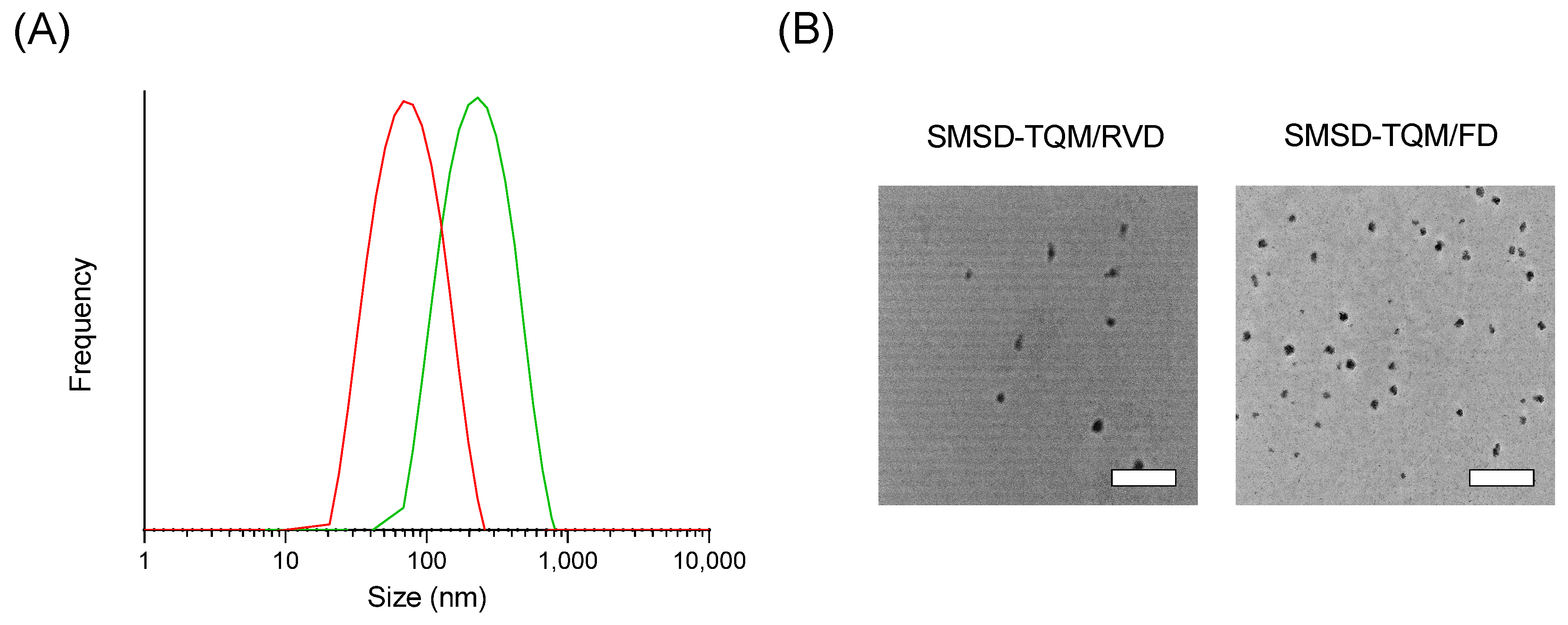

3.3. Physicochemical Characterizations

3.4. Dissolution Behavior of the Optimized Formulation in Comparing the Effect of Drying in the Preparation of SMSD-TQM

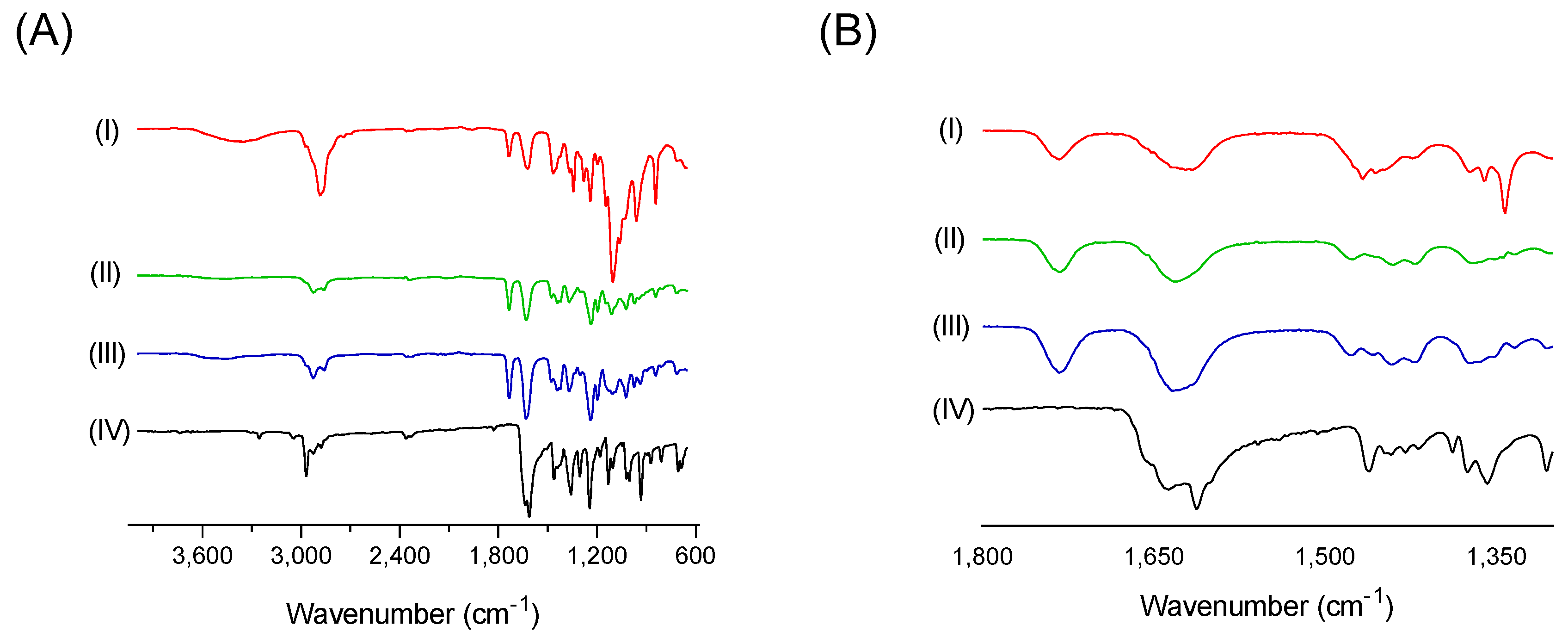

3.5. Drug Polymer Interactions

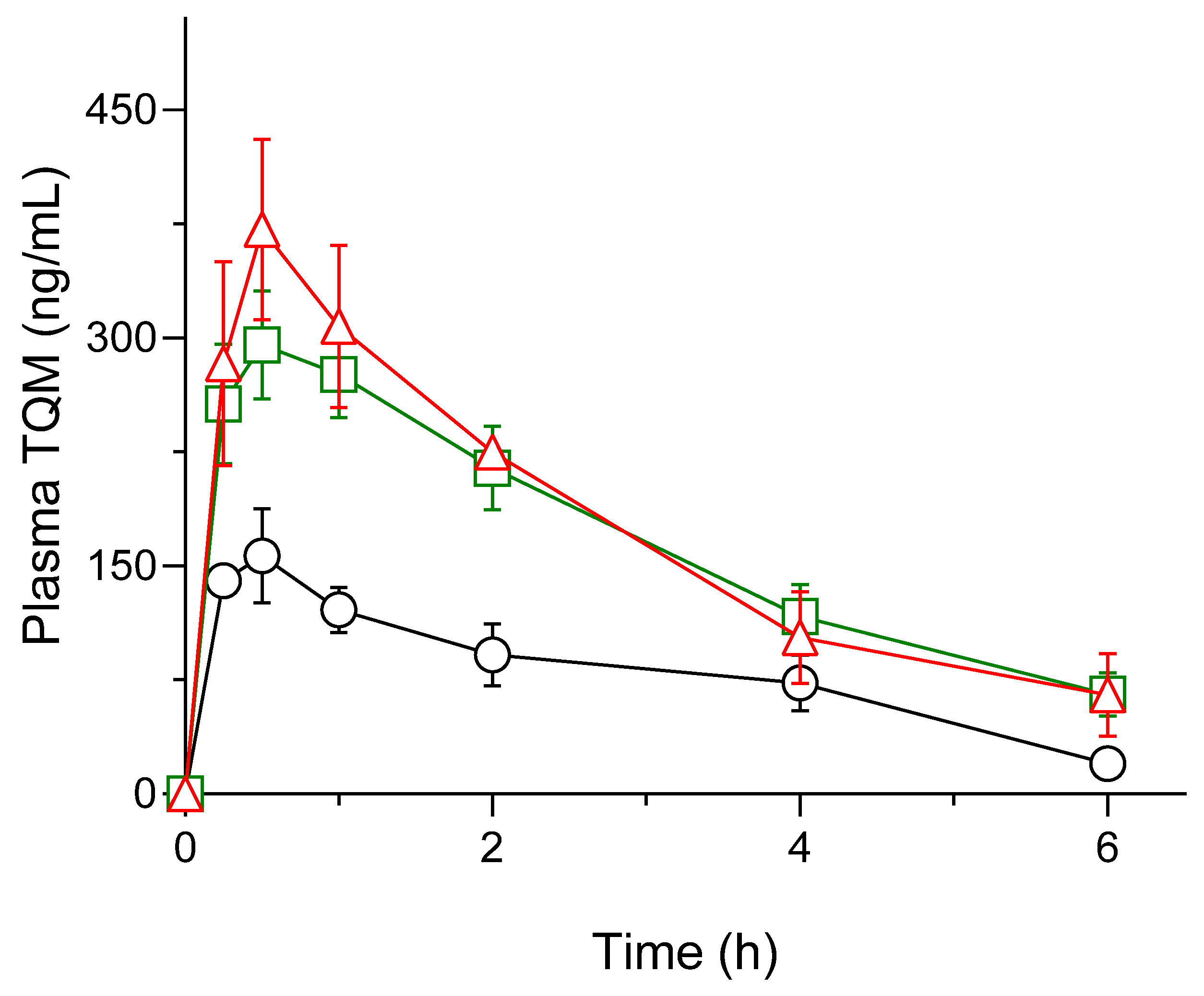

3.6. Pharmacokinetic Assessment

3.7. Nephroprotective Effect of TQM Samples in Cisplatin-treated Rats

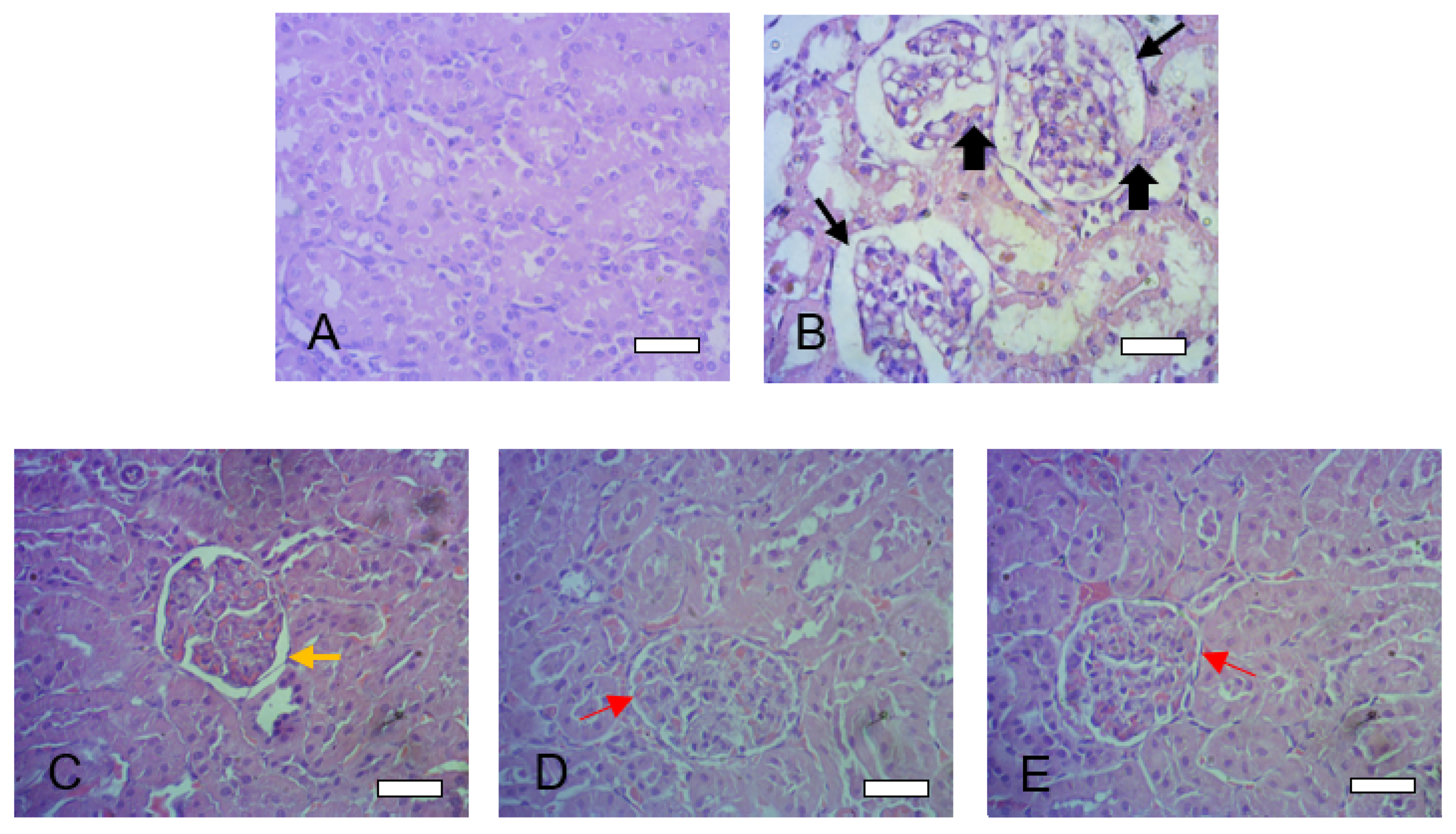

3.8. Histopathological Assessment

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interests

References

- Dera, A. A.; Rajagopalan, P.; Alfhili, M. A.; Ahmed, I.; Chandramoorthy, H. C. Thymoquinone attenuates oxidative stress of kidney mitochondria and exerts nephroprotective effects in oxonic acid-induced hyperuricemia rats. BioFactors 2020, 46, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, S.; Ghosh, A. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Bangladesh: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, S. N.; Prajapati, C. P.; Gore, P. R.; Patil, C. R.; Mahajan, U. B.; Sharma, C.; Talla, S. P.; Ojha, S. K. Therapeutic potential and pharmaceutical development of thymoquinone: A multitargeted molecule of natural origin. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaterzadeh-Yazdi, H.; Noorbakhsh, M.-F.; Samarghandian, S.; Farkhondeh, T. An Overview on Renoprotective Effects of Thymoquinone. Kidney Dis. 2018, 4, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqui, Z.; Shahid, F.; Khan, A. A.; Khan, F. Oral administration of Nigella sativa oil and thymoquinone attenuates long term cisplatin treatment induced toxicity and oxidative damage in rat kidney. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ali, A.; Alkhawajah, A. A.; Randhawa, M. A.; Shaikh, N. A. Oral and intraperitoneal LD50 of thymoquinone, an active principle of Nigella sativa, in mice and rats. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2008, 20, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Elmowafy, M.; Samy, A.; Raslan, M. A.; Salama, A.; Said, R. A.; Abdelaziz, A. E.; El-Eraky, W.; El Awdan, S.; Viitala, T. Enhancement of Bioavailability and Pharmacodynamic Effects of Thymoquinone Via Nanostructured Lipid Carrier (NLC) Formulation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, H. M.; Khardrawy, Y. A.; Abd-El Daim, T. M.; Elfeky, A. S.; Abd Rabo, A. A.; Mustafa, A. B.; Mostafa, I. T. Thymoquinone-encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles coated with polysorbate 80 as a novel treatment agent in a reserpine-induced depression animal model. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 222, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shire, S. J. Formulation of proteins and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). In Monoclonal Antibodies; 2015; pp. 93–120 ISBN 9780081002964.

- Yoshioka, M.; Hancock, B. C.; Zografi, G. Crystallization of Indomethacin from the Amorphous State below and above Its Glass Transition Temperature. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994, 83, 1700–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, S.; Joseph, L.; Mathew, G. Improvement in solubility of poor water-soluble drugs by solid dispersion. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2012, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. A.; Ali, R.; Al-Jenoobi, F. I.; Al-Mohizea, A. M. Solid dispersions: a strategy for poorly aqueous soluble drugs and technology updates. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012, 9, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzoate, E. Application of Solid Dispersion Technique to. 2019, 1–18.

- Rodriguez-Aller, M.; Guillarme, D.; Veuthey, J. L.; Gurny, R. Strategies for formulating and delivering poorly water-soluble drugs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 30, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, R. B.; Thipparaboina, R.; Kumar, D.; Shastri, N. R. Co amorphous systems: A product development perspective. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 515, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoue, S.; Yamada, S.; Chan, H. K. Nanodrugs: Pharmacokinetics and safety. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoue, S.; Suzuki, H.; Kojo, Y.; Matsunaga, S.; Sato, H. Self-micellizing solid dispersion of cyclosporine A with improved dissolution and oral bioavailability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 62, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kojo, Y.; Yakushiji, K.; Yuminoki, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Onoue, S. Strategic application of self-micellizing solid dispersion technology to respirable powder formulation of tranilast for improved therapeutic potential. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 499, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, S.; Suzuki, H.; Seto, Y.; Sato, H.; Onoue, S. Megestrol acetate-loaded self-micellizing solid dispersion system for improved oral absorption and reduced food effect. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N. Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lai, H. W.; Xiao, X.; Feng, B.; Qi, X. R. Self-micellizing solid dispersions enhance the properties and therapeutic potential of fenofibrate: Advantages, profiles and mechanisms. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 528, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avsar, S. Y.; Kyropoulou, M.; Leone, S. Di; Schoenenberger, C. A.; Meier, W. P.; Palivan, C. G. Biomolecules turn self-assembling amphiphilic block co-polymer platforms into biomimetic interfaces. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N. S.; Kaus, N. H. M.; Szewczuk, M. R.; Hamid, S. B. S. Formulation, characterization and cytotoxicity effects of novel thymoquinone-plga-pf68 nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T.; Connors, K. A. Phase Solubility Studies. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instrum. 1965, 4, 117–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bergonzi, M. C.; Vasarri, M.; Marroncini, G.; Barletta, E.; Degl’Innocenti, D. Thymoquinone-loaded soluplus®-solutol® HS15 mixed micelles: Preparation, in vitro characterization, and effect on the SH-SY5Y cell migration. Molecules 2020, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amidon, G. E.; Secreast, P. J.; Mudie, D. Chapter 8 - Particle, Powder, and Compact Characterization. In Developing Solid Oral Dosage Forms; Qiu, Y., Chen, Y., Zhang, G. G. Z., Liu, L., Porter, W. R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2009; pp. 163–186. ISBN 978-0-444-53242-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, F. G.; Williams, G. R. Advanced Approaches to Effective Solid-State Analysis: X-Ray Diffraction, Vibrational Spectroscopy and Solid-State NMR. ChemInform 2011, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarachi, A. Differential Scanning Calorimetry: A Review. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharm. Technol. 2020, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential – What they are and what they are not ? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malatesta, M. Transmission Electron Microscopy as a Powerful Tool to Investigate the Interaction of Nanoparticles with Subcellular Structures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Cong, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, N. Applications of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to pharmaceutical preparations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Khan, R. M. A.; Alkharfy, K. M.; Raish, M.; Al-Jenoobi, F. I.; Al-Mohizea, A. M. Effects of thymoquinone on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glibenclamide in a rat model. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Parvardeh, S.; Asl, M. N.; Sadeghnia, H. R.; Ziaee, T. Effect of thymoquinone and Nigella sativa seeds oil on lipid peroxidation level during global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat hippocampus. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; Xie, S. PKSolver: An add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2010, 99, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choie, D. D.; Longnecker, D. S.; del Campo, A. A. Acute and chronic cisplatin nephropathy in rats. Lab. Invest. 1981, 44, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sampson, E. J.; Baird, M. A. Chemical inhibition used in a kinetic urease/glutamate dehydrogenase method for urea in serum. Clin. Chem. 1979, 25, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihei, T.; Sato, H.; Onoue, S. Biopharmaceutical characterization of a novel sustained-release formulation of allopurinol with reduced nephrotoxicity. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2021, 42, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shill, M. C.; Bepari, A. K.; Khan, M.; Tasneem, Z.; Ahmed, T.; Hasan, M. A.; Alam, M. J.; Hossain, M.; Rahman, M. A.; Sharker, S. M.; Shahriar, M.; Rahman, G. M. S.; Reza, H. M. Therapeutic potentials of colocasia affinis leaf extract for the alleviation of streptozotocin-induced diabetes and diabetic complications: In vivo and in silico-based studies. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, W. R.; Tse, J.; Carter, G. Lipopolysaccharide-induced changes in plasma nitrite and nitrate concentrations in rats and mice: pharmacological evaluation of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 272, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Witko-Sarsat, V.; Friedlander, M.; Capeillère-Blandin, C.; Nguyen-Khoa, T.; Nguyen, A. T.; Zingraff, J.; Jungers, P.; Descamps-Latscha, B. Advanced oxidation protein products as a novel marker of oxidative stress in uremia. Kidney Int. 1996, 49, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, H. P.; Fridovich, I. The Role of Superoxide Anion in the Autoxidation of Epinephrine and a Simple Assay for Superoxide Dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1972, 247, 3170–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jollow, D. J.; Mitchell, J. R.; Zampaglione, N.; Gillette, J. R. Bromobenzene-Induced Liver Necrosis. Protective Role of Glutathione and Evidence for 3,4-Bromobenzene Oxide as the Hepatotoxic Metabolite. Pharmacology 1974, 11, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.; Marques, S.; Sarmento, B. The biopharmaceutical classification system of excipients. Ther. Deliv. 2017, 8, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, A.-R.; Griffin, B. T.; Vertzoni, M.; Kuentz, M.; Kolakovic, R.; Prudic-Paus, A.; Malash, A.; Bohets, H.; Herman, J.; Holm, R. Exploring precipitation inhibitors to improve in vivo absorption of cinnarizine from supersaturated lipid-based drug delivery systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 159, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangarde, Y. M.; T. K., S.; Panigrahi, N. R.; Mishra, R. K.; Saraogi, I. Amphiphilic Small-Molecule Assemblies to Enhance the Solubility and Stability of Hydrophobic Drugs. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 28375–28381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoue, S.; Kojo, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Yuminoki, K.; Kou, K.; Kawabata, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Hashimoto, N.; Yamada, S. Development of novel solid dispersion of tranilast using amphiphilic block copolymer for improved oral bioavailability. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 452, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezzi, M.; Pescina, S.; Padula, C.; Santi, P.; Del Favero, E.; Cantù, L.; Nicoli, S. Polymeric micelles in drug delivery: An insight of the techniques for their characterization and assessment in biorelevant conditions. J. Control. Release 2021, 332, 312–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J. M.; Mejia-Ariza, R.; Ilevbare, G. A.; McGettigan, H. E.; Sriranganathan, N.; Taylor, L. S.; Davis, R. M.; Edgar, K. J. Interplay of Degradation, Dissolution and Stabilization of Clarithromycin and Its Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 4640–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, E.; Baek, I.; Cho, W.; Hwang, S.; Kim, M. Preparation and evaluation of solid dispersion of atorvastatin calcium with Soluplus® by spray drying technique. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 2014, 62, 545–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. Y.; Kang, W. S.; Piao, J.; Yoon, I. S.; Kim, D. D.; Cho, H. J. Soluplus®/TPGSGS-based solid dispersions prepared by hot-melt extrusion equipped with twin-screw systems for enhancing oral bioavailability of valsartan. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015, 9, 2745–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Qu, M.; Deng, L.; Gong, T.; Zhang, Z. A (polyvinyl caprolactam-polyvinyl acetate-polyethylene glycol graft copolymer)-dispersed sustained-release tablet for imperialine to simultaneously prolong the drug release and improve the oral bioavailability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 79, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, D.; Yu, H.; Tao, J.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Gan, Y. Supersaturated polymeric micelles for oral cyclosporine A delivery: The role of Soluplus-sodium dodecyl sulfate complex. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2016, 141, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yu, H.; Luo, Q.; Yang, S.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, B.; Tang, X. Increased dissolution and oral absorption of itraconazole/Soluplus extrudate compared with itraconazole nanosuspension. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakova, E. V; Kabanov, A. V Pluronic block copolymers: Evolution of drug delivery concept from inert nanocarriers to biological response modifiers. J. Control. Release 2008, 130, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, Y. Quantitative polarized light microscopy using spectral multiplexing interferometry. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 2622–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoue, S.; Suzuki, H.; Kojo, Y.; Matsunaga, S.; Sato, H.; Mizumoto, T.; Yuminoki, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Yamada, S. Self-micellizing solid dispersion of cyclosporine A with improved dissolution and oral bioavailability. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 62, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, B.; Soo, J.; Kang, S.; Young, S.; Hong, S. Development of self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS) for oral bioavailability enhancement of simvastatin in beagle dogs. 2004, 274, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoue, S.; Nakamura, T.; Uchida, A.; Ogawa, K.; Yuminoki, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Hiza, A.; Tsukaguchi, Y.; Asakawa, T.; Kan, T.; Yamada, S. Physicochemical and biopharmaceutical characterization of amorphous solid dispersion of nobiletin, a citrus polymethoxylated flavone, with improved hepatoprotective effects. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 49, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serajuddln, A. T. M. Solid dispersion of poorly water-soluble drugs: Early promises, subsequent problems, and recent breakthroughs. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Wang, Y.; Armenante, P. M. Velocity profiles and shear strain rate variability in the USP Dissolution Testing Apparatus 2 at different impeller agitation speeds. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 403, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoumetzidis, A.; Macheras, P. A century of dissolution research: From Noyes and Whitney to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 321, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoue, S.; Kojo, Y.; Aoki, Y.; Kawabata, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Yamada, S. Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic characterization of amorphous solid dispersion of tranilast with enhanced solubility in gastric fluid and improved oral bioavailability. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2012, 27, 379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M. M.; Jaipal, A.; Charde, S. Y.; Goel, P.; Kumar, L. Dissolution enhancement of felodipine by amorphous nanodispersions using an amphiphilic polymer: insight into the role of drug–polymer interactions on drug dissolution. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2016, 21, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariare, M. H.; Khan, M. A.; Al-Masum, A.; Khan, J. H.; Uddin, J.; Kazi, M. Development of Stable Liposomal Drug Delivery System of Thymoquinone and Its In Vitro Anticancer Studies Using Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgen, M.; Bloom, C.; Beyerinck, R.; Bello, A.; Song, W.; Wilkinson, K.; Steenwyk, R.; Shamblin, S. Polymeric Nanoparticles for Increased Oral Bioavailability and Rapid Absorption Using Celecoxib as a Model of a Low-Solubility, High-Permeability Drug. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, K.; Chopra, S.; Dhar, D.; Arora, S.; Khar, R. K. Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems: An approach to enhance oral bioavailability. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, Y.; Wada, K.; Nakatani, M.; Yamada, S.; Onoue, S. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: Basic approaches and practical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojo, Y.; Matsunaga, S.; Suzuki, H.; Sato, H.; Seto, Y.; Onoue, S. Improved oral absorption profile of itraconazole in hypochlorhydria by self-micellizing solid dispersion approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 97, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, S.; Sato, H.; Onoue, S. Self-micellizing solid dispersion of atorvastatin with improved physicochemical stability and oral absorption. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 68, 103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marullo, R.; Werner, E.; Degtyareva, N.; Moore, B.; Altavilla, G.; Ramalingam, S. S.; Doetsch, P. W. Cisplatin induces a mitochondrial-ROS response that contributes to cytotoxicity depending on mitochondrial redox status and bioenergetic functions. PLoS One 2013, 8, e81162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, H.; Kaminski, D.; Gangaraju, R.; Adebiyi, A. Cisplatin-induced oxidative stress stimulates renal Fas ligand shedding. Ren. Fail. 2018, 40, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, M. F.; Abdel-Moneim, A. M. H.; Alsharidah, A. S.; Mobark, M. A.; Abdellatif, A. A. H.; Saleem, I. Y.; Rugaie, O. Al; Mohany, K. M.; Alsharidah, M. Thymoquinone lowers blood glucose and reduces oxidative stress in a rat model of diabetes. Molecules 2021, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complex/Parameter | S0 (g/mol) | Slope | R2 | Ks (M-1) | C.E. |

| TQM-Soluplus® | 0.001428 | 0.0099 | 0.9831 | 1161.5 | 0.010 |

| TQM-Kolliphor® P188 | 0.0037 | 0.9735 | 427.1 | 0.004 | |

| TQM- Kolliphor® P407 | 0.01 | 0.8441 | 1149.4 | 0.010 |

| Composition of SMSD-TQM (w/w %) |

Initial dissolution rate (hr-1) |

% dissolved at 60 min | ||

| TQM | Soluplus® | |||

| Crystalline TQM | 100 | - | 0.767 ± 0.03 | 45.2 ± 4.6 |

| SMSD-TQM/5 | 5 | 95 | 1.128 ± 0.10 | 73.9 ± 6.2 |

| SMSD-TQM/10 | 10 | 90 | 1.062 ± 0.21 | 89.3 ± 6.6 |

| SMSD-TQM/15 | 15 | 85 | 0.770 ± 0.14 | 66.7 ± 12.6 |

| Parameters | Crystalline TQM (10 mg/kg; p.o.) |

SMSD-TQM/RVD (5 mg-TQM/kg; p.o.) |

SMSD-TQM/FD (5 mg-TQM/kg; p.o.) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 165.5 ± 23.3 | 298.2 ± 32.6 | 425.1 ± 11.2** |

|

Dose normalized Cmax (ng/mL) |

16.55 ± 2.33 | 59.64 ± 6.52 | 85.02 ± 2.23 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 0.67 ± 0.16 | 0.41 ± 0.08 |

| AUC0–6 (ng・h/mL) | 488.1 ± 89.7 | 1,002.5 ± 122.3 | 1,049.3 ± 44.44* |

| AUC0–∞ (ng・h/mL) | 554.6 ± 79.6 | 1,230.5 ± 184.3 | 1,349.9 ± 262.6* |

|

Dose normalized AUC0–∞ (ng・h/mL) |

55.46 ± 7.94 | 246.09 ± 36.87 | 269.98 ± 52.51 |

| MRT (h) | 2.25 ± 0.05 | 2.23 ± 0.03 | 2.08 ± 0.23 |

| Vd (L) | 0.061 ± 0.02 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.025 ± 0.005 |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.3 ± 0.36 | 2.34 ± 0.16 | 2.38 ± 0.96 |

| Ke (h-1) | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.10 |

| Absolute BA (%) | 2.8 | 12.5 | 13.7 |

| Relative BA (%) | 100 | 443 | 487 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).