Submitted:

22 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- the challenges inherent in the modelling of ‘data generating mechanisms’, and ‘dataset generating processes’, whenever either of these are incompletely understood or poorly theorized; and

- the troublesome cognitive tendencies that accompany the application of all analytical tools, in which their ease of use and practical utility seems to obviate the discipline required to identify, evaluate and acknowledge all prevailing uncertainties and assumptions – particularly those that might prove irreducible.

2. The Strengths of Directed Acyclic Graphs in Applied and Theoretical Epidemiology

2.1. Transparency

- the analysts concerned – who might have: been unaware of these uncertainties; not intended to make such assumptions; or overlooked their implications; and

- third parties and others, including peers, reviewers and end-users – who are then able to examine, comprehend and evaluate the implications of these uncertainties and assumptions for the design and outputs of associated causal inference analyses.

2.2. Simplicity

2.3. Flexibility

- involve a number of very different (and potentially contested and contradictory) considerations; and

- be used in both hypothetical and more practical applications.

2.4. Methodological Utility

2.4.1. Hypothesizing

2.4.2. Sampling

2.4.3. Data Availability/Collection

2.4.4. Data analysis

- are, together, likely to capture the most variance in confounding; and

- have been measured with the greatest accuracy and precision (so as to reduce the risk of residual confounding – this being the proportion of confounder bias remaining, even after conditioning/adjustment, that is contributed by measurement error [2]).

2.4.5. Interpretation

- where one or more potential confounders have not been, or cannot be, measured; or

- where conditioning on one or more colliders is unavoidable, unintended or deemed necessary or desirable.

- any non-comprehensive sampling procedures will be capable of generating absolutely representative samples that do not (unintentionally) condition on potential colliders;

- any covariate adjustment set will include all potential confounders (given a comprehensive list of confounders will include many that are: conceivable yet unmeasured or unmeasurable variables; and hitherto inconceivable and therefore unmeasured or unmeasurable variables);

- all (measured) confounders that have been subjected to conditioning (through sampling, stratification or inclusion in the multivariate models’ covariate adjustment sets) will have been measured with absolute precision (‘residual confounding’, as we have already seen, being that proportion of confounder bias remaining – despite conditioning/adjustment – that is contributed by measurement error); and

- all covariates will be accurately classified as potential confounders, mediators or consequences of the outcome so that conditioning on those classified as potential confounders includes only those that genuinely are.

2.4.6. Critical Appraisal and Synthesis

- endogenous selection bias/unrepresentative sampling (collider bias);

- under-adjustment for potential confounders (confounder bias – and particularly when these involve confounders measured by, or available to, at least some of the studies examined); or

- over-adjustment for consequences of the outcome mistaken as competing exposures (whether unintentionally or intentionally to enhance precision) or mediators (whether unintentionally or intentionally to generate naïve estimates of direct causal effects), or indeed, when either consequences of the outcome or mediators are mistaken for bona fide confounders, and vice versa [49,50]).

2.5. Consistency Evaluation

- the conditioning decisions made – such as the study’s sampling and stratification procedures, and the covariate adjustment sets used in each of the study’s multivariable statistical analyses (all of which should be consistent with the risks of collider bias and confounding evident in the DAG); and

- the conditional or contingent nature of any inferences drawn on the basis of these decisions and analyses – such as acknowledging the possibility or likelihood of: unadjusted/unmeasured and residual confounding; and both intentional and unintentional/irreducible collider bias.

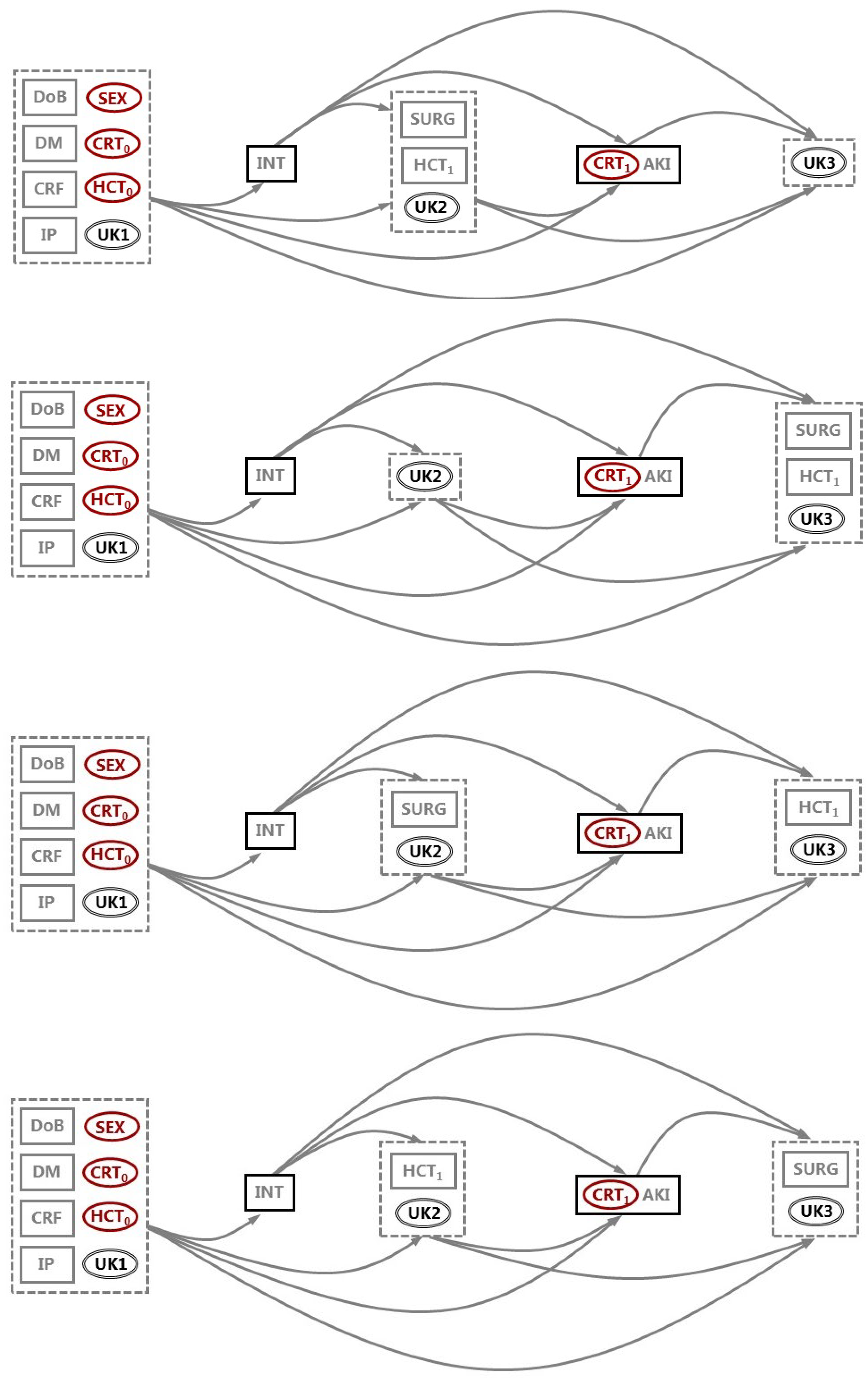

- evaluate whether the DAGs that analysts have developed and specified on theoretical, speculative and temporal/probabilistic grounds might actually, and in any way, reflect the real-world data they are intended to represent – assuming, of course, that the analysts’ DAGs were intended to accurately represent the data generating mechanism(s) and dataset generating process(es) involved (which may not be the case if the DAGs were intentionally hypothetical or experimental [13,15,25]; see 3.4 and 3.6, below); and

- identify the full range of DAGs that might be parametrically plausible for the dataset(s) at hand – thereby prompting subsequent consideration of the basis on which one (or more) of these DAGs might actually – and optimally – reflect the underlying data generating mechanism(s) and dataset generating process(es) involved.

2.6. Epistemological Credibility

3. The Weaknesses of Directed Acyclic Graphs in Applied and Theoretical Epidemiology

3.1. Transparency

3.2. Simplicity

3.3. Flexibility

- (i)

- DAGs can be developed on the basis of theoretical knowledge, speculation, temporal/ probabilistic considerations, or a combination of all three; and

- (ii)

- the rationales involved in DAG development and specification impose constraints on their intended – and likely – application(s) – and their associated internal validity and external generalizability.

- help others (peers, reviewers and end-users) assess the consistency of a DAG’s design-related decisions with its intended application(s), and with the rationale(s) on which the DAG was developed and specified; but might also

- prompt analysts to more carefully reflect on: the intended application(s) of their DAGs (to ensure these are ‘fit for purpose’); and any (explicit and implicit) uncertainties, assumptions and potential inconsistencies incurred by the rationale(s) used to develop and specify these.

3.4. Methodological Utility

- their internal validity (i.e., whether, as specified, these accurately reflect the uncertainties and assumptions involved, the rationale[s] on which they were derived, and the application[s] they were intended to support); to

- their external validity (i.e., whether, as applied, these DAGs support meaningful analyses, findings and insights).

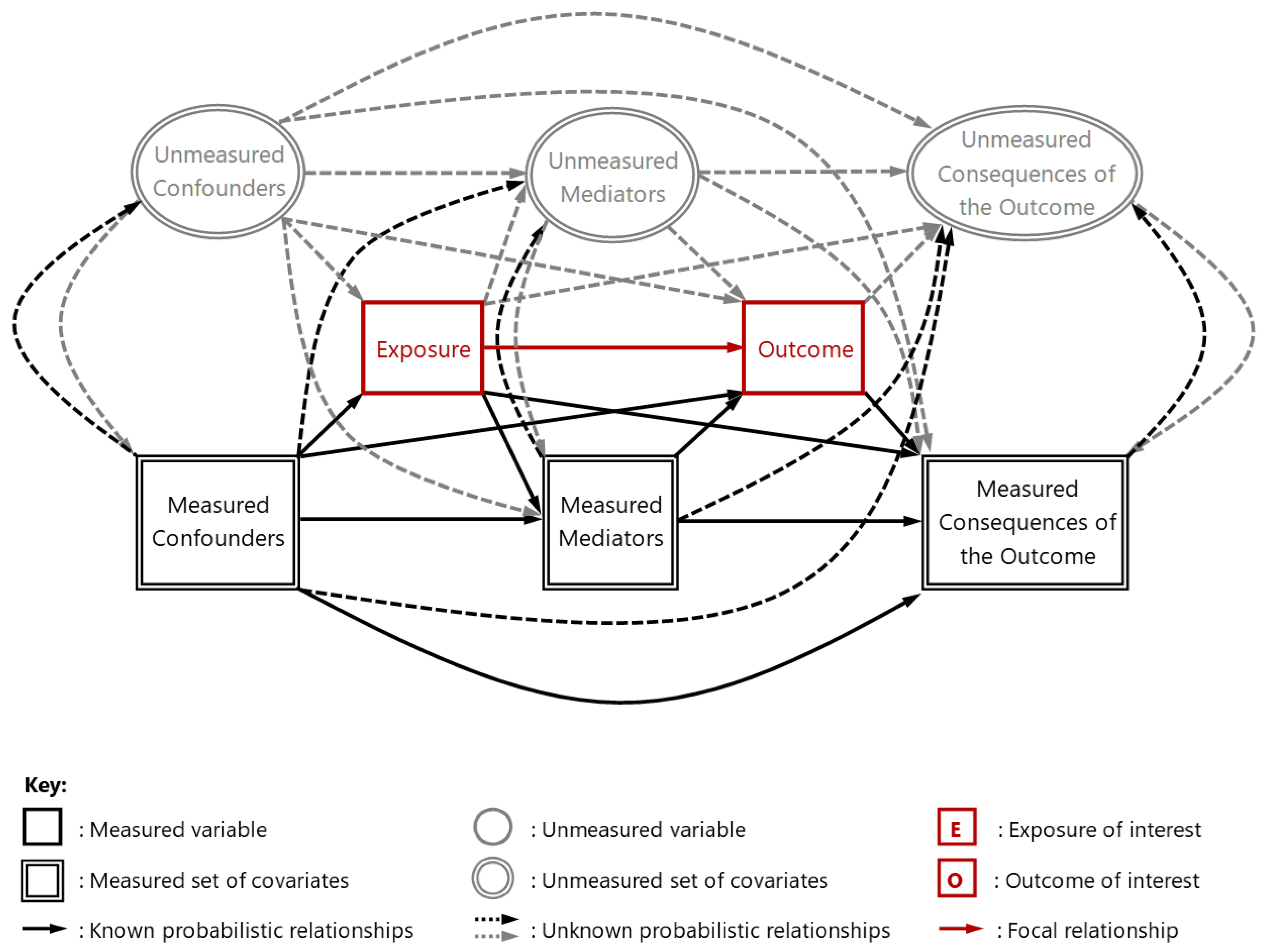

- First, it requires that all DAGs intended to represent uncertain, real-world data generating mechanisms are ‘saturated’ (i.e., contain all of the permissible paths that directionality and acyclicity allow) such that each variable is assumed to cause all subsequent variables [70] – except, that is, in those rare instances where there is unequivocal evidence that supports the omission of one or more paths.

- Second, it eliminates the possibility that any variables might operate independently of (all) preceding variables – except, that is, for those variables situated at the very beginning of the causal pathways examined, where any preceding cause(s) are unlikely to have been measured/measurable.

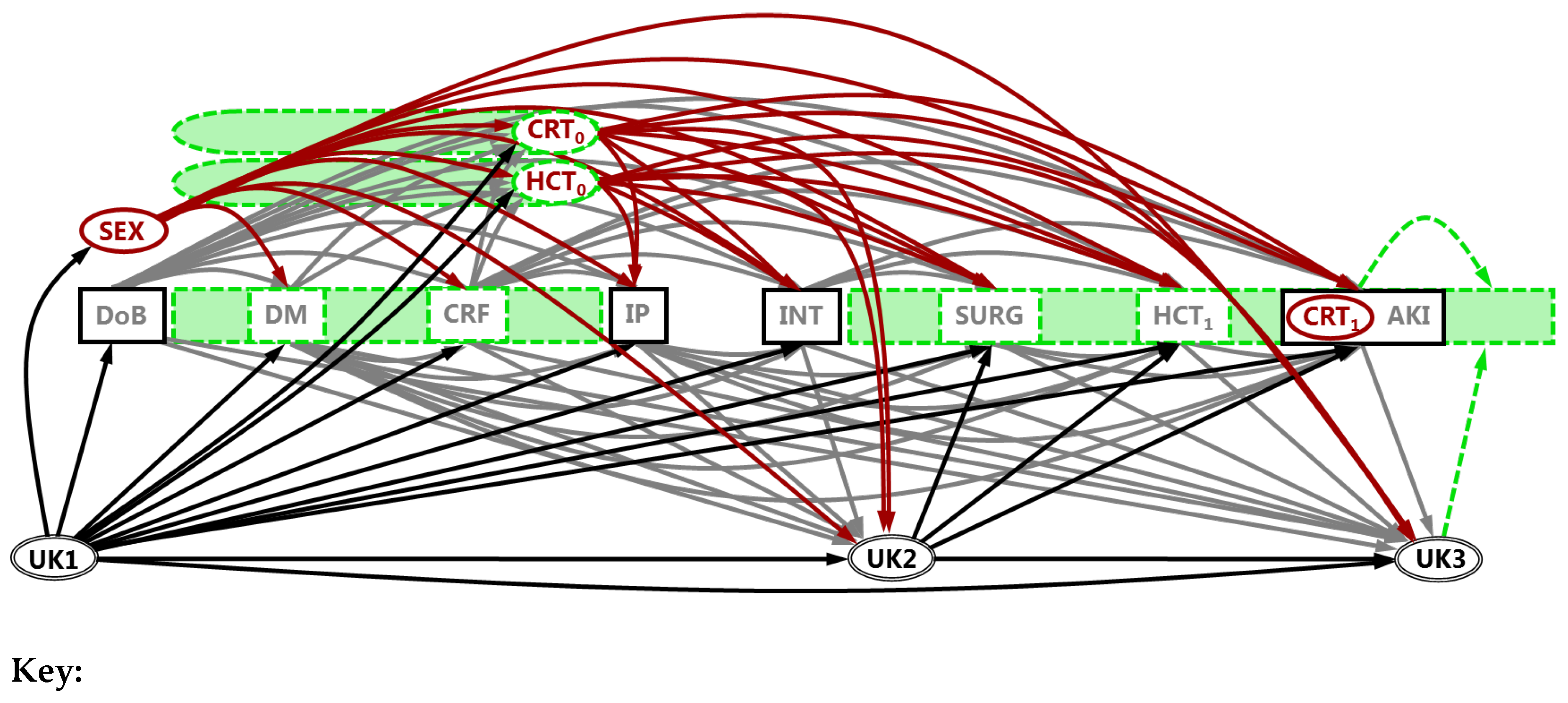

3.4.1. Causal Inference Modelling

- First, that many competing exposures will actually be the probabilistic consequences of any measured and unmeasured variables that occur before these variables (including any preceding mediators, the specified exposure and, thereafter, all potential confounders).

- Second, that some variables considered competing exposures might actually occur/crystallize after the outcome and might therefore prove to be probabilistic consequences of the outcome.

3.4.2. Prediction Modelling

3.5. Consistency Evaluation

- prepared to speculate (or at least consider the possibility) that one or more of the permissible causal paths – i.e., those that directionality and acyclicity allow – are actually missing; or

- confident that definitive and unequivocal (empirical, experiential or theoretical) knowledge exists to support such a possibility.

3.6. Epistemological Credibility

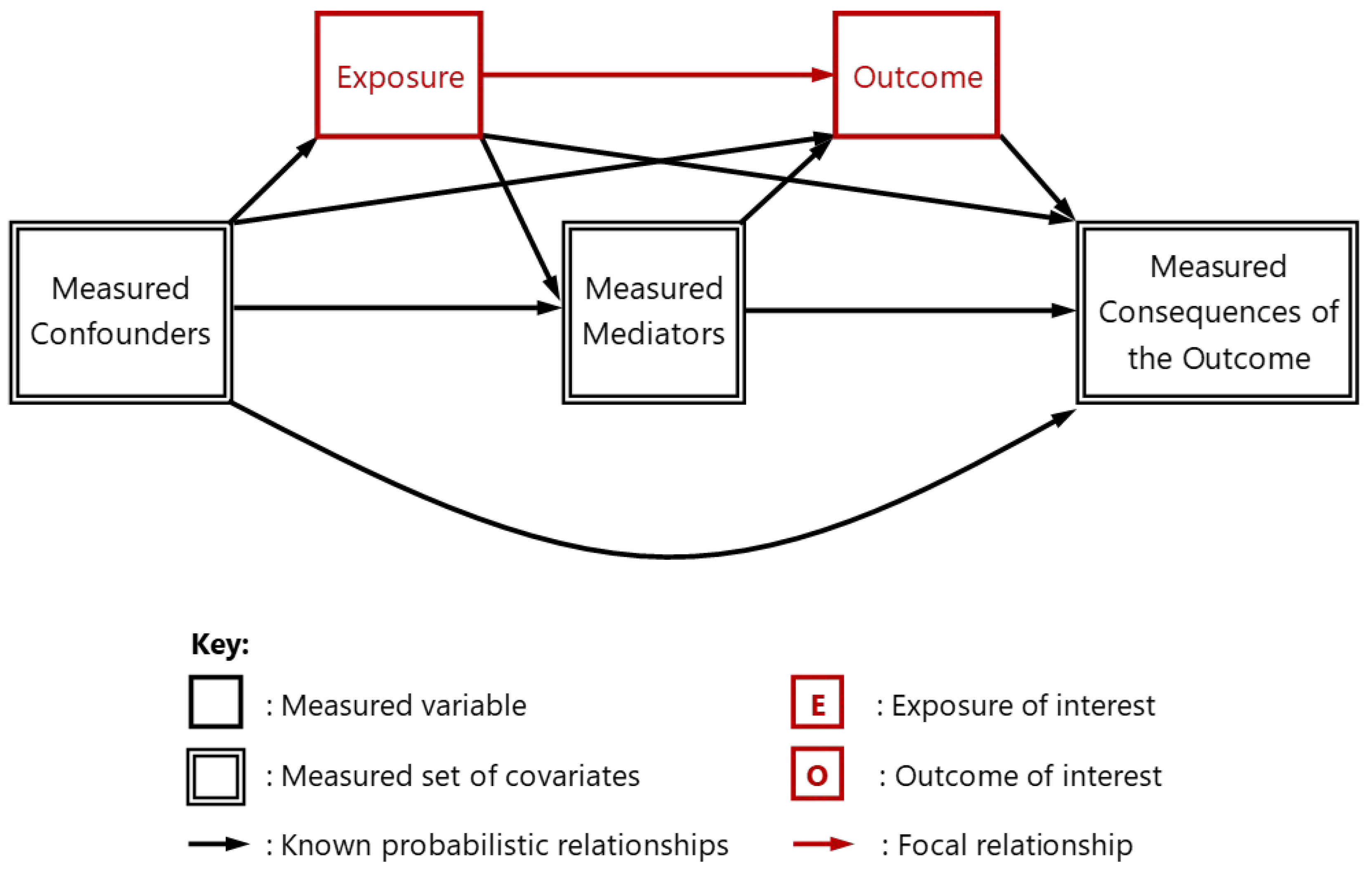

- map all of the potential additional roles that covariates might play within an otherwise simplistic and unsaturated DAG – i.e., one that simply includes: a specified exposure and a specified outcome; and one or more confounders, mediators and consequences of the outcome;

- and to evaluate both:

- the potential risk of bias that each of these additional roles might pose when estimating the focal relationship between a specified exposure and specified outcome; and

- the likely occurrence of these additional roles in real-world contexts – based on understanding informed by theoretical knowledge, speculation and temporality/probabilistic considerations.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Use of AI Tools Declaration

References

- Biggs, N.L.; Lloyd, E.K.; Theory, R.J.W.G. , 1736-1936. Oxford University Press, (1976), 1-239. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/graph-theory-1736-1936-9780198539162?cc=gb&lang=en&.

- Law, G.R.; Green, R.; Ellison, G.T.H. , Confounding and causal path diagrams. In Modern Methods for Epidemiology, (ed.s Y-K. Tu, D. C. Greenwood), Springer (2012), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Müller, M. , Depth-first discovery algorithm for incremental topological sorting of directed acyclic graphs. Inf Process Lett 2003, 88, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, I.A. Path partition in directed graph–modeling and optimization. New Trend Math Sci 2013, 1, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, P.W.G.; Murray, E.J.; Arnold, K.F.; Berrie, L.; Fox, M.P.; Gadd, S.C.; Harrison, W.J.; Keeble, C.; Ranker, L.R.; Textor, J.; Tomova, G.D.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Ellison, G.T.H. , Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol 2021, 50, 620–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, G.T.H. , Using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to represent the data generating mechanisms of disease and healthcare pathways: a guide for educators, students, practitioners and researchers, Chapter 6 in Teaching Biostatistics in Medicine and Allied Health Sciences (eds. R. J. Medeiros Mirra, D. Farnell), Springer Verlag (2023), 61-101. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M., A. Kuerbis. An overview of causal directed acyclic graphs for substance abuse researchers. J Drug Alcohol Res 2016, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, B.; VanderWeele, T.J. , Use of directed acyclic graphs, in Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User’s Guide, (ed.s P. Velentgas, N. A. Dreyer, P. Nourjah, S. R. Smith, M. M. Torchia), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2013), 177-183. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126190/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK126190.

- Knight, C.R.; Winship, C. , The causal implications of mechanistic thinking: Identification using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), in Handbook of Causal Analysis for Social Research, (ed. S. Morgan), Springer (2013), 275-299. [CrossRef]

- Laubach, Z.M.; Murray, E.J.; Hoke, K.L.; Safran, R.J.; Perng, W. , A biologist’s guide to model selection and causal inference. Proc Biol Sci 2021, 288, 20202815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digitale, J.C.; Martin, J.N.; Glymour, M.M. , Tutorial on directed acyclic graphs. J Clin Epidemiol 2021, 142, 264–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, H.; Wakabayashi, T.; Kato, R. , The dawn of directed acyclic graphs in primary care research and education. J Gen Fam Med 2023, 24, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S. , DAGs in data engineering: A powerful, problematic tool. Shipyard Blog, /: (2024). https://web.archive.org/web/20240823202053/, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R.A.; Cosgrove, J.A.; Lee, B.R. , Directed acyclic graphs in social work research and evaluation: A primer. J Soc Social Work Res 2024, 15, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakant, K., G. Piwowarek. Practical Applications of Directed Acyclic Graphs. 2024 Mar 18. https://www.baeldung.com/cs/dag-applications.

- Elwert, F. , Causal Inference with DAGs, Population Health Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison (2011). https://web.archive.org/web/20210727162641/https://dlab.berkeley.edu/training/causal-inference-observational-data.

- Gilthorpe, M.S.; Tennant, P.W.G.; Ellison, G.T.H.; Textor, J. , Advanced Modelling Strategies: Challenges and Pitfalls in Robust Causal Inference with Observational Data. Society for Social Medicine Summer School, Leeds Institute for Data Analytics, University of Leeds (2017). https://web.archive.org/web/20240823190804/https://lida.leeds.ac.uk/events/advanced-modelling-strategies-challenges-pitfalls-robust-causal-inference-observational-data/.

- Hernán, M.A. , Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, TH Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, MA; 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20210117065704/.

- Roy, J.A. , A Crash Course in Causality: Inferring Causal Effects from Observational Data, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Rutgers University (2018). https://web.archive.org/web/20180310140518/.

- Hünermund, P. , Causal Data Science with Directed Acyclic Graphs, Copenhagen Business School, University of Copenhagen (2021). https://web.archive.org/web/20200523155727/.

- Aneshensel, C.S. , Theory-Based Data Analysis for the Social Sciences, Sage (2002), 1-282.

- Pearl, J. , Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems, Elsevier (1988), 1-152. [CrossRef]

- Frieden, T.R. , Evidence for health decision making—beyond randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 465–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccininni, M.; Konigorski, S.; Rohmann, J.L.; Kurth, T. , Directed acyclic graphs and causal thinking in clinical risk prediction modelling. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020, 20, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Sperrin, M.; Jenkins, D.A.; Martin, G.P.; Peek, N. , A scoping review of causal methods enabling predictions under hypothetical interventions. Diagn Progn Res 2021, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msaouel, P.; Lee, J.; Karam, J.A.; Thall, P.F. , A causal framework for making individualized treatment decisions in oncology. Cancers 2022, 14, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, J.; Piccininni, M.; Konigorski, T.K.S. , Assessing the transportability of clinical prediction models for cognitive impairment using causal models. BMC Med Res Meth 2023, 23, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRRS (Committee on Reproducibility and Replicability in Science), Reproducibility and Replicability in Science, National Academies Press, (2019), 1-256. [CrossRef]

- Alfawaz, R.A.; Ellison, G.T.H. , Using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to enhance the critical appraisal of studies seeking causal inference from observational data: An analysis of research examining the causal relationship between sleep and metabolic syndrome (MetS) between 2006-2014, medRxiv, (2024), submitted.

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liśkiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T.H. , Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int J Epidemiol 2016, 45, 1887–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Campos, M.D. , The algebra of directed acyclic graphs, in Computation, Logic, Games, and Quantum Foundations. The Many Facets of Samson Abramsky (eds. B. Coecke, L. Ong, P. Panangaden), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer, (2013), 37-51. [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, S.; Richardson, S. ; Best, Adjusting for selection bias in retrospective, case–control studies. Biostatistics 2009, 10, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, G.T.H. , Might temporal logic improve the specification of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs)? J Stat Data Sci Educ 2021, 29, 202–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafti, A.; Shmueli, G. , Beyond overall treatment effects: Leveraging covariates in randomized experiments guided by causal structure. Inf Syst Res 2020, 31, 1183–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, F.E.; O’Keeffe, T.; Chockler, H.; Lawrence, A.R.; Stemberga, T.; Franca, A.; Sipos, M.; Butler, J.; Ben-Haim, S. , Causal analysis of the TOPCAT trial: Spironolactone for preserved cardiac function heart failure. arXiv 2022, 2211, 12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, G.J.; Morris, T.T.; Tudball, M.J.; Herbert, A.; Mancano, G.; Pike, L.; Sharp, G.C.; Sterne, J.; Palmer, T.M.; Smith, G.D., K. Tilling. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudgens, M.G.; Halloran, M.E. , Toward causal inference with interference. J Am Stat Ass 2008, 103, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. , The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations, J Pers Soc Psychol 1986, 51, 1173–82. 51. [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J. , A unification of mediation and interaction: a four-way decomposition. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 749–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenwold, R.H.; Palmer, T.M.; Tilling, K. ; To adjust or not to adjust? When a “confounder” is only measured after exposure, Epidemiology 2021, 32, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Berkman, N.D.; Dryden, D.M.; Hartling, L. , Assessing Risk of Bias and Confounding in Observational Studies of Interventions or Exposures: Further Development of the RTI Item Bank, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, (2013), 1-49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 1544. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jewair, T.S.; Pandis, N.; Tu, Y.-K. , Directed acyclic graphs: A tool to identify confounders in orthodontic research, Part II. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2017, 151, 619–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zander, B.; Liśkiewicz, M.; Textor, J. , Constructing separators and adjustment sets in ancestral graphs. Proc Conf Causal Inf Learn Pred 2014, 1274, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland, S.; Pearl, J.; Robins, J.M. , Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwert, F.; Winship, C. , Endogenous selection bias: The problem of conditioning on a collider variable. Ann Rev Sociol 2014, 40, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dondo, T.B.; Hall, M.; Munyombwe, T.; Wilkinson, C.; Yadegarfar, M.E.; Timmis, A.; Batin, P.D.; Jernberg, T.; Fox, K.A.; Gale, C.P. , A nationwide causal mediation analysis of survival following ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart 2020, 106, 765–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, D.A. , On regression adjustments to experimental data. Adv Appl Math 2008, 40, 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; D’Addario, M.; Egger, M.; Cevallos, M.; Dekkers, O.; Mugglin, C.; Scott, P. , Methods to systematically review and meta-analyse observational studies: a systematic scoping review of recommendations. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, O.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Cevallos, M.; Renehan, A.G.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M. , COSMOS-E: guidance on conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies of etiology. PLoS Med 2019, 16, e1002742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, G.; Patorno, E.; Yuan, H.; Guo, J.J.; Bennett, D.; Wen, X.; Zullo, A.R.; Largent, J.; Panaccio, M.; Gokhale, M.; Moga, D.C. , Framework for the synthesis of non-randomised studies and randomised controlled trials: a guidance on conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis for healthcare decision making. Brit Med J Evid Based Med 2020, 27, 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankan, A.; Wortel, I.M. Testing graphical causal models using the R package “dagitty”. Curr Protocols 2021, 1, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, P.; Miratrix, L.W. , To adjust or not to adjust? Sensitivity analysis of M-bias and Butterfly-bias. J Caus Inf 2015, 3, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J. , Commentary: Resolutions of the birthweight paradox: competing explanations and analytical insights. Int J Epidemiol 2014, 43, 1368–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, S.J.; Collier, T.J.; Dandreo, K.J.; de Stavola, B.L.; Goldman, M.B.; Kalish, L.A.; Kasten, L.E.; McCormack, V.A. , Issues in the reporting of epidemiological studies: a survey of recent practice. Brit Med J 2004, 329, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Egger, M. , The scandal of poor epidemiological research. Brit Med J 2004, 329, 868–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, A.; Stewart, P.; Lubin, J.H.; Forastiere, F. , Methodological issues regarding confounding and exposure misclassification in epidemiological studies of occupational exposures. Am J Ind Med 2007, 50, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detweiler, B.N.; Kollmorgen, L.E.; Umberham, B.A.; Hedin, R.J.; Vassar, B.M. , Risk of bias and methodological appraisal practices in systematic reviews published in anaesthetic journals: a meta-epidemiological study. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 955–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, T. , Continuing to advance epidemiology, Front Epidemiol 2021, 1, 782374. 1. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, G.T.H. , COVID-19 and the epistemology of epidemiological models at the dawn of AI, Ann Hum Biol 2020, 47, 506–13. 47. [CrossRef]

- Tomić, V.; Buljan, I.; Marušić, A. , Perspectives of key stakeholders on essential virtues for good scientific practice in research areas. Account Res 2021, 29, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J.; Hardt, J.; Knüppel, S. , DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J. , DAGbase: A database of human-drawn causal diagrams, Proc Eur Causal Inf Mtg, (2020). https://web.archive.org/web/20240617185756/https://dagbase.

- Stacey, T.; Tennant, P.W.G.; McCowan, L.M.E.; Mitchell, E.A.; Budd, J.; Li, M.; Thompson, J.M.D.; Martin, B.; Roberts, D.; Heazell, A.E.P. , Gestational diabetes and the risk of late stillbirth: a case–control study from England, UK. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol 2019, 126, 973–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, N. , The Concept of Physical Law (Second Ed.), Cambridge University Press (2003), 1-220. https://www.sfu.ca/~swartz/physical-law/cpl-all.

- Box, G.E.P. ; Science; statistics. J Am Stat Ass 1976, 71, 791–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GTH, G.T.H.E.; RB, M.; Rhoma H; Wet T, D. , Economic vulnerability and poor service delivery made it more difficult for shack-dwellers to comply with COVID-19 restrictions. S Afr J Sci 2022, 118, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, D. , A Treatise of Human Nature, John Noon; 1738.

- Barrows, M.; Ellison, G.T.H. , ‘Belief-Consistent Information Processing’ vs. ‘Coherence-Based Reasoning’: Pragmatic frameworks for exposing common cognitive biases in intelligence analysis. Preprints, 0240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, G.A.; Burks, D.; Abate, M.R.; Faramawi, M.F.; Ali, A.T.; Lyons, L.C.; Moursi, M.M.; Smeds, M.R. , Risk of acute kidney injury after percutaneous pharmacomechanical thrombectomy using AngioJet in venous and arterial thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg 2017, 42, 238–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraita, R.; Spallek, J.; Zeeb, H. ; Directed acyclic graphs, in Handbook of Epidemiology (eds. W. Ahrens, I. Pigeot), Springer (2014), 1481-1517. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.J.; Altman, D.G. , Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Brit Med J 1986, 292, 746–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-K.; Gunnell, D.; Paradox, M.S. Simpson’s Paradox, Lord’s Paradox, and Suppression Effects are the same phenomenon–the reversal paradox. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2008, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schisterman, E.F.; Cole, S.R.; Platt, R.W. , Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2009, 20, 488–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richiardi, L.; Bellocco, R.; Zugna, D. , Mediation analysis in epidemiology: methods, interpretation and bias. Int J Epidemiol 2013, 42, 1511–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, K.J.; Lash, T.L. , Epidemiologic study design with validity and efficiency considerations, Chapter 6, in Modern Epidemiology (ed.s T. L. Lash, T. J. VanderWeele, S. Haneuse, K. J. Rothman), Wolters Kluwer (2021), 161-213.

- Castelletti, F. , Bayesian model selection of Gaussian directed acyclic graph structures. Int Stat Rev 2020, 88, 752–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, Q. , Bayesian multi-task variable selection with an application to differential DAG analysis. J Comput Graph Stat 2024, 33, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Unmeasured variables are often termed ‘unknown’, ‘unobserved’ or ‘latent’ variables; while measured variables are occasionally termed ‘known’, ‘observed’ or ‘manifest’ variables |

| 2 | ‘Permissible paths’ are those paths that are consistent with directionality and acyclicity

|

| 3 | Although the aims of causal inference and prediction are very different – the former being concerned with mechanistic processes, the latter with classification/estimation – the temporal and contextual stability of many causal mechanisms makes understanding of these very useful for designing, developing and utilizing predictive algorithms in contexts/at times where the data-set generating processes might vary [24–27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).