Submitted:

26 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

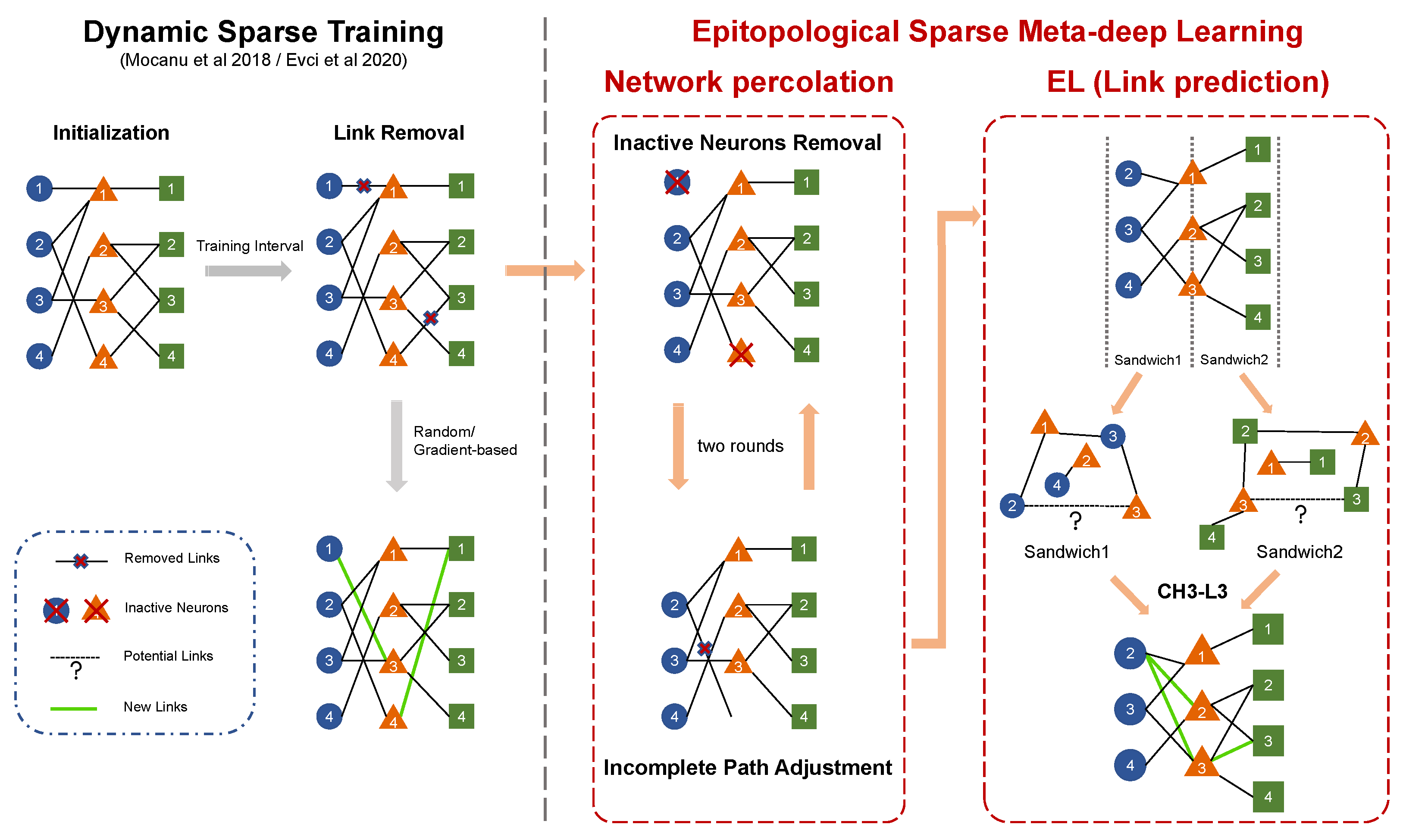

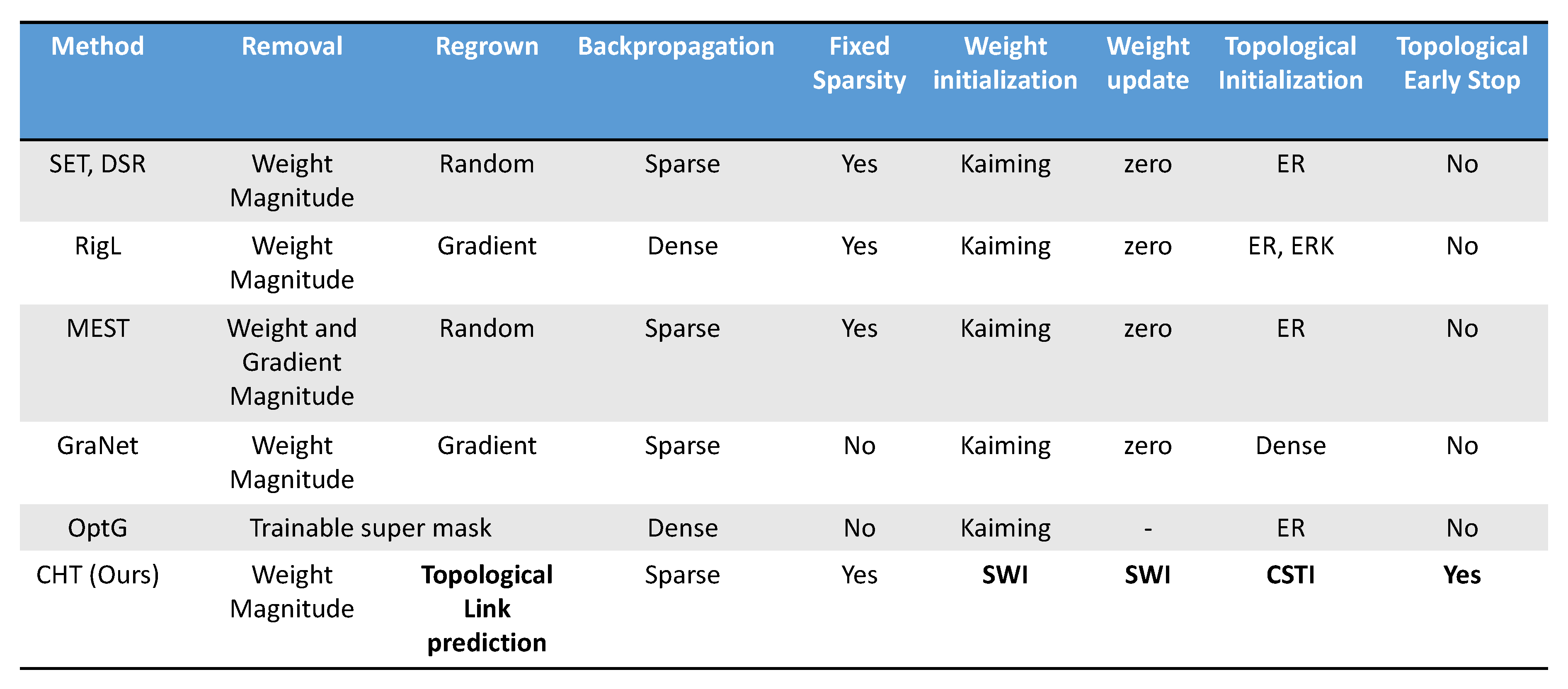

2.1. Dynamic sparse training

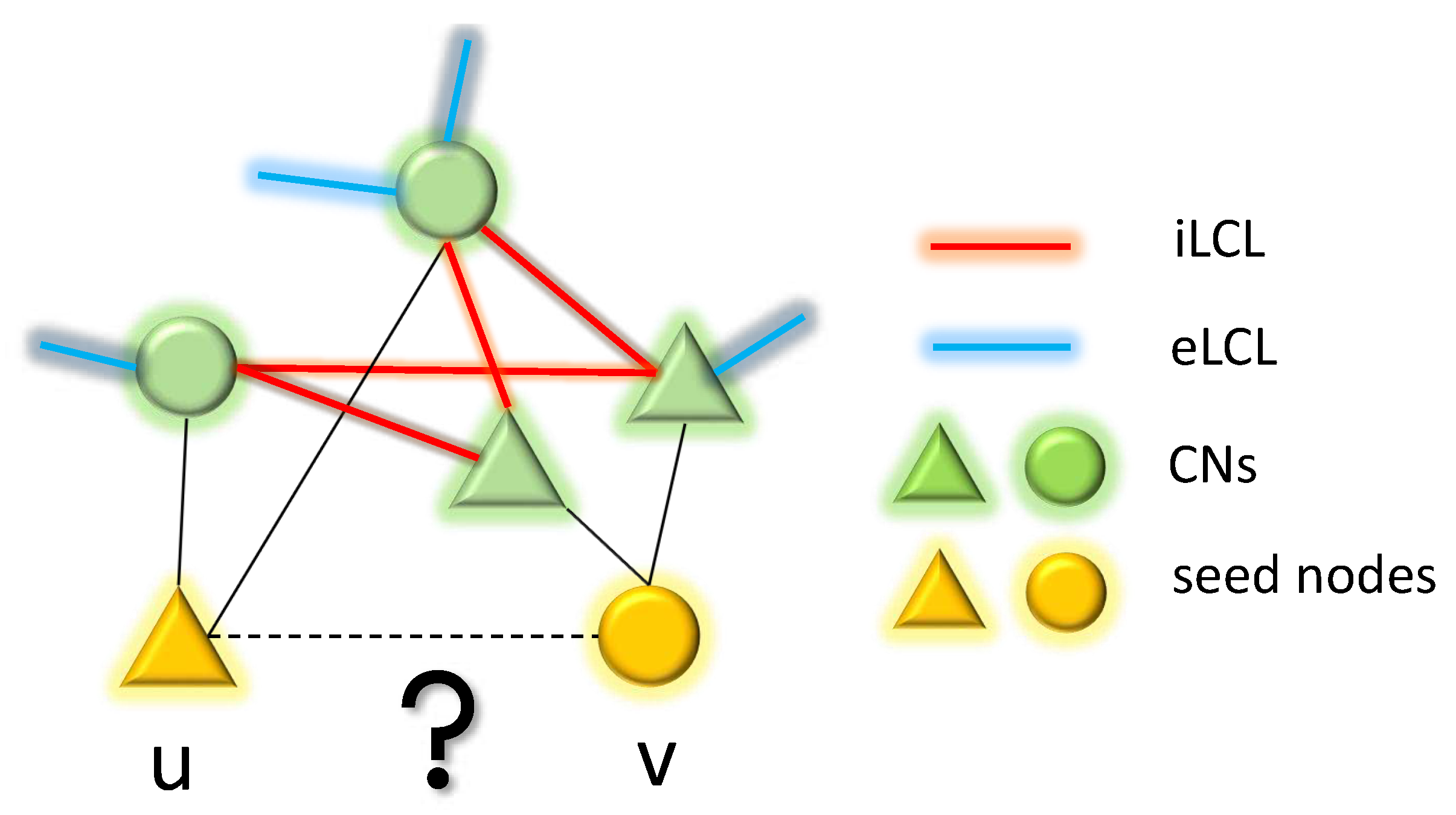

2.2. Epitopological Learning and Cannistraci-Hebb network automata theory for link prediction

3. Epitopological sparse meta-deep learning and Cannistraci-Hebb training

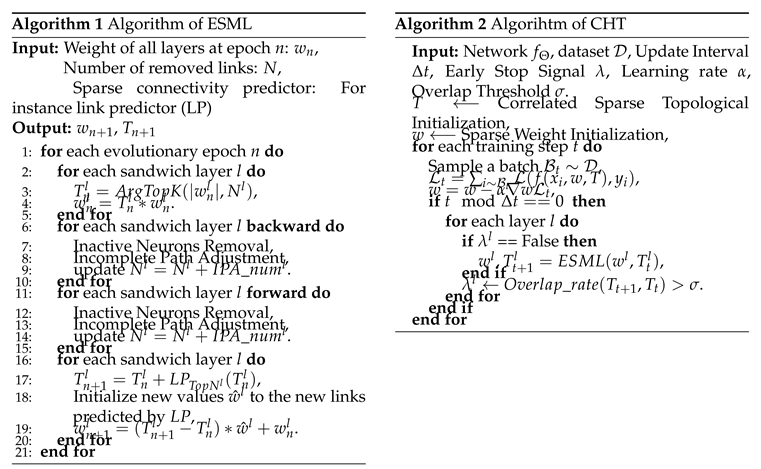

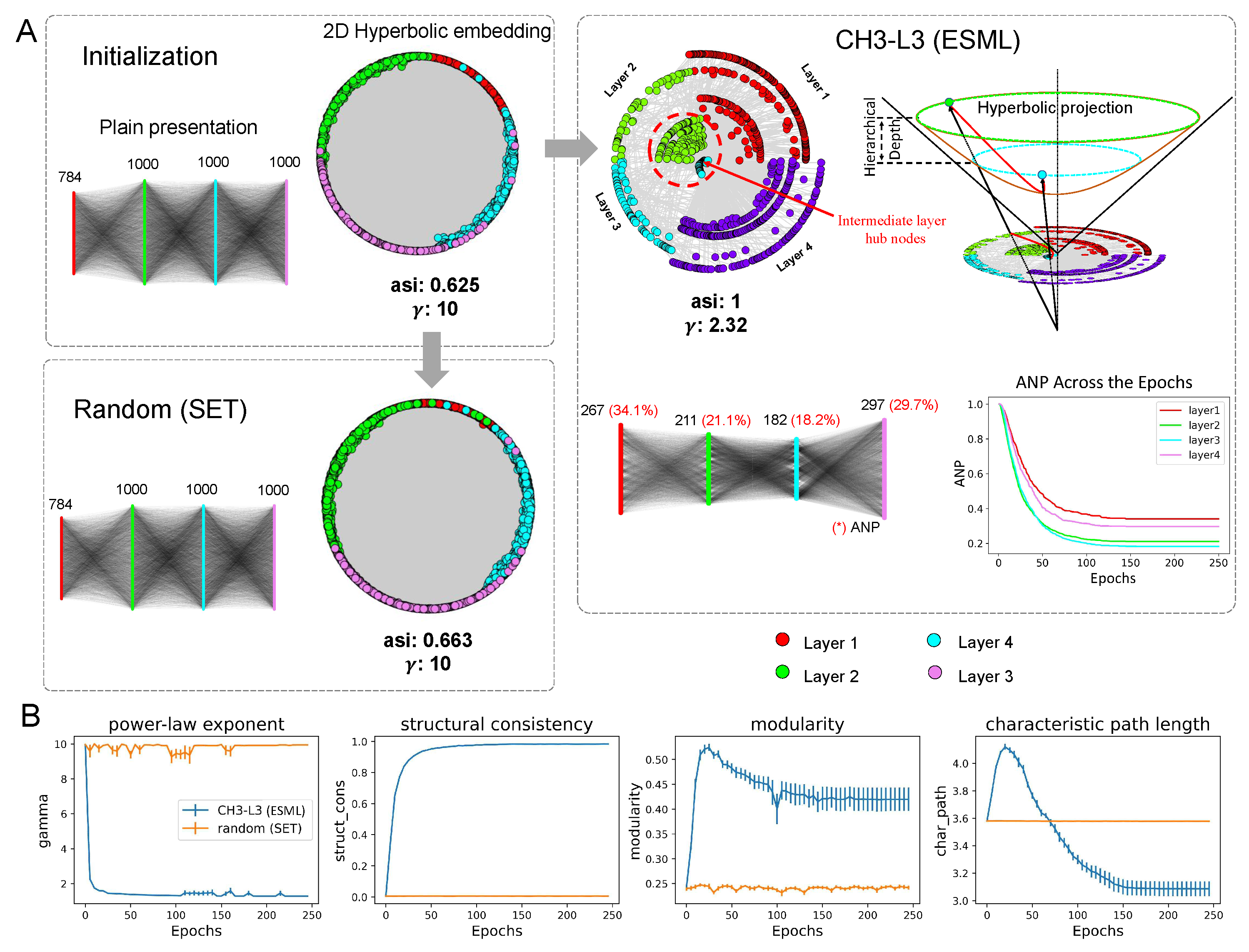

3.1. Epitopological sparse meta-deep learning (ESML)

3.2. Cannistraci-Hebb training

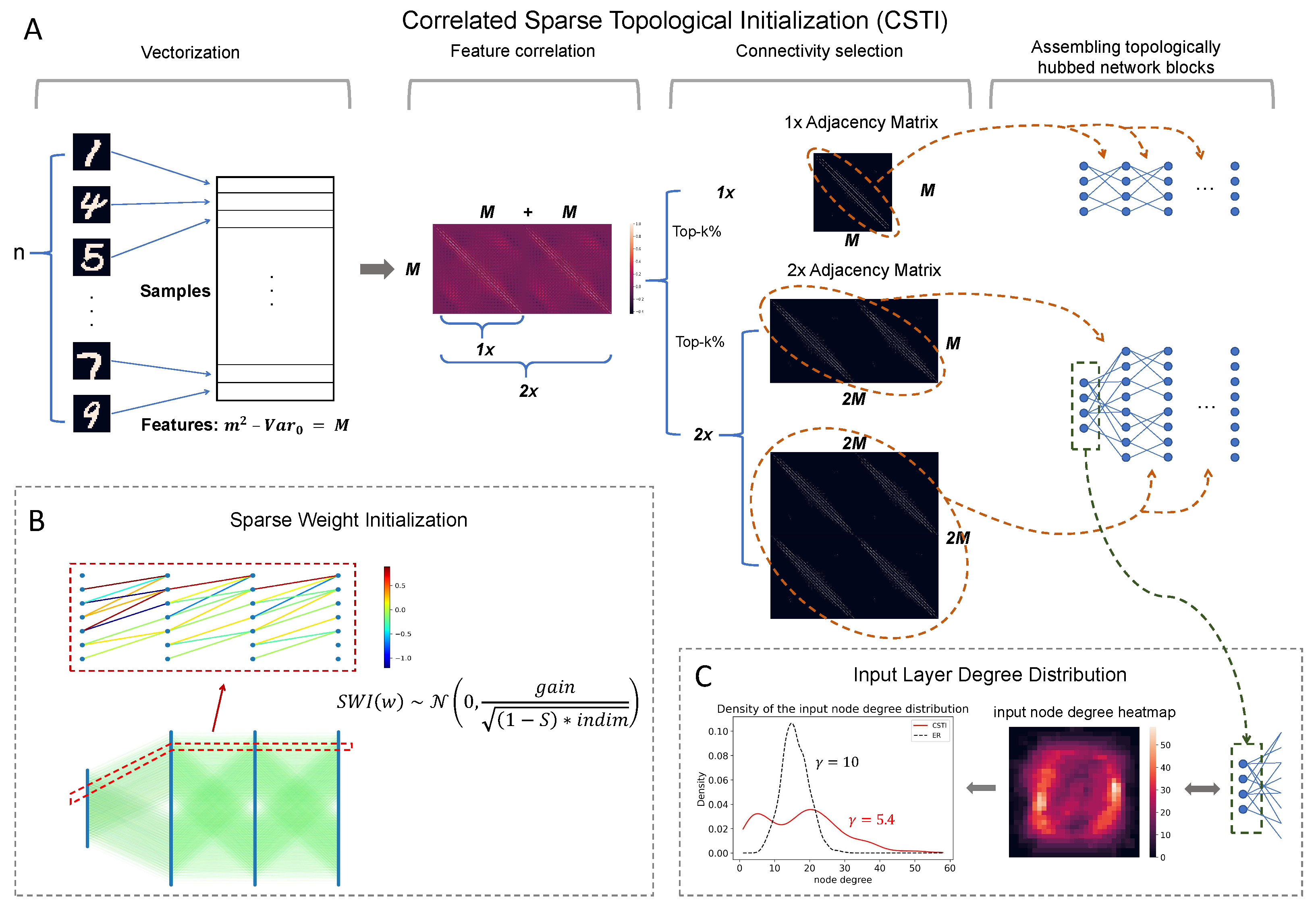

- Correlated sparse topological initialization (CSTI): as shown in Figure A4, CSTI consists of 4 steps. 1) Vectorization: During the vectorization phase, we follow a specific procedure to construct a matrix of size , where n represents the number of samples selected from the training set. M denotes the number of valid features, obtained by excluding features with zero variance () among the selected samples. 2) Feature selection: Once we have this matrix, we proceed with feature selection by calculating the Pearson Correlation for each feature. This step allows us to construct a correlation matrix. 3) Connectivity selection: Subsequently, we construct a sparse adjacency matrix, where the positions marked with “1" (represented as white in the heatmap plot of Figure A4) correspond to the top-k% values from the correlation matrix. The specific value of k depends on the desired sparsity level. This adjacency matrix plays a crucial role in defining the topology of each sandwich layer. The dimension of the hidden layer is determined by a scaling factor denoted as ‘×’. A scaling factor of implies that the hidden layer’s dimension is equal to the input dimension, while a scaling factor of indicates that the hidden layer’s dimension is twice the input dimension which allows the dimension of the hidden layer to be variable. In fact, since ESML can efficiently reduce the dimension of each layer, the hidden dimension can automatically reduce to the inferred size. 4) Assembling topologically hubbed network blocks: Finally, we implement this selected adjacency matrix to form our initialized topology for each sandwich layer.

-

Sparse Weight Initialization (SWI): In addition to the topological initialization, we also recognize the importance of weight initialization in the sparse network. The standard initialization methods such as Kaiming He et al. (2015) or Xavier Glorot & Bengio (2010) are designed to keep the variance of the values consistent across layers. However, these methods are not suitable for sparse network initialization since the variance is not consistent with the previous layer. To address this issue, we propose a method that can assign initial weights in any sparsity cases. SWI can also be extended to the fully connected network, in which case it becomes equivalent to Kaiming initialization. Here we provide the mathematical formula for SWI and in Appendix B, we provide the rationale that brought us to its definition.The value of gain varies for different activation functions. In this article, all the models use ReLU, where the gain is always . S here denotes the desired sparsity and indicates the input dimension of each sandwich layer.

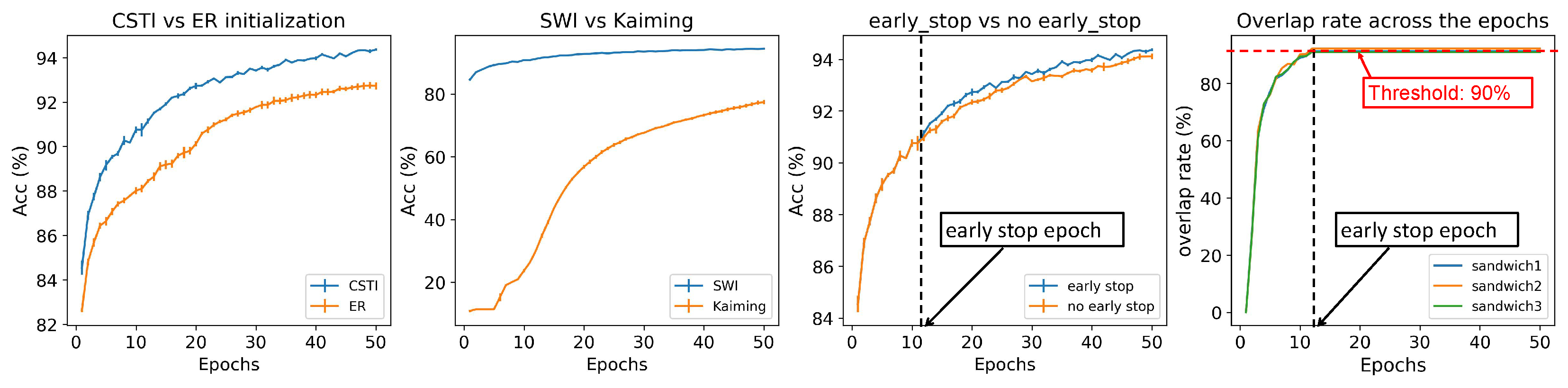

- Epitopological prediction: This step corresponds to ESML (introduced in Section 3.1) but evolves the sparse topological structure starting from CSTI+SWI initialization rather than random.

- Early stop and weight refinement: During the process of Epitological prediction, it is common to observe an overlap between the links that are removed and added, as shown in the last plot in Figure A2. After several rounds of topological evolution, the overlap rate can reach a high level, indicating that the network has achieved a relatively stable topological structure. In this case, ESML may continuously remove and add mostly the same links, which can slow down the training process. To solve this problem, we introduce an early stop mechanism for each sandwich layer. When the overlap rate between the removal and regrown links reaches a certain threshold (we use a significant level of 90%), we stop the epitopological prediction for that layer. Once all the sandwich layers have reached the early stopping condition, the model starts to focus on learning and refining the weights using the obtained network structure.

4. Results

4.1. Setup

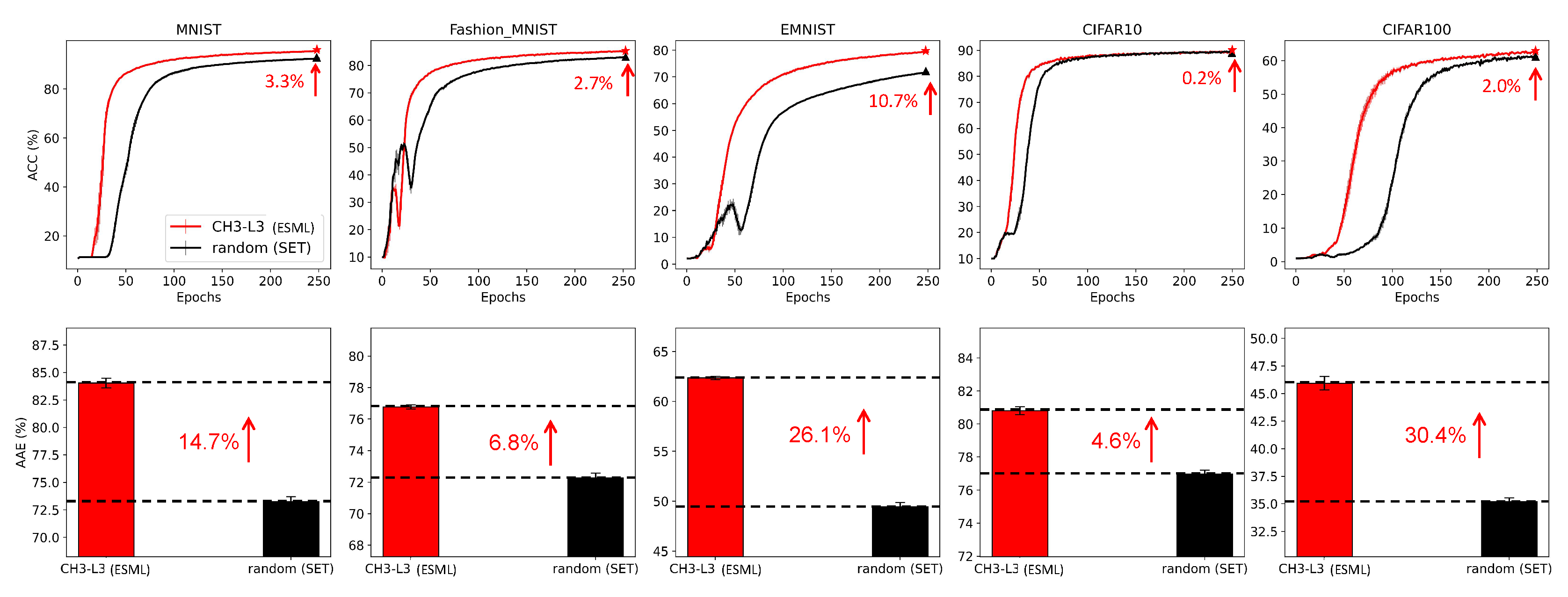

4.2. Results for ESML and Network analysis of epitopological-based link regrown

4.2.1. ESML prediction performance

4.2.2. Network Analysis

Network percolation.

Hyperbolic hierarchical organization.

Hyperbolic community organization.

The emergency of meta-depth

4.2.2.5. Network measure analysis

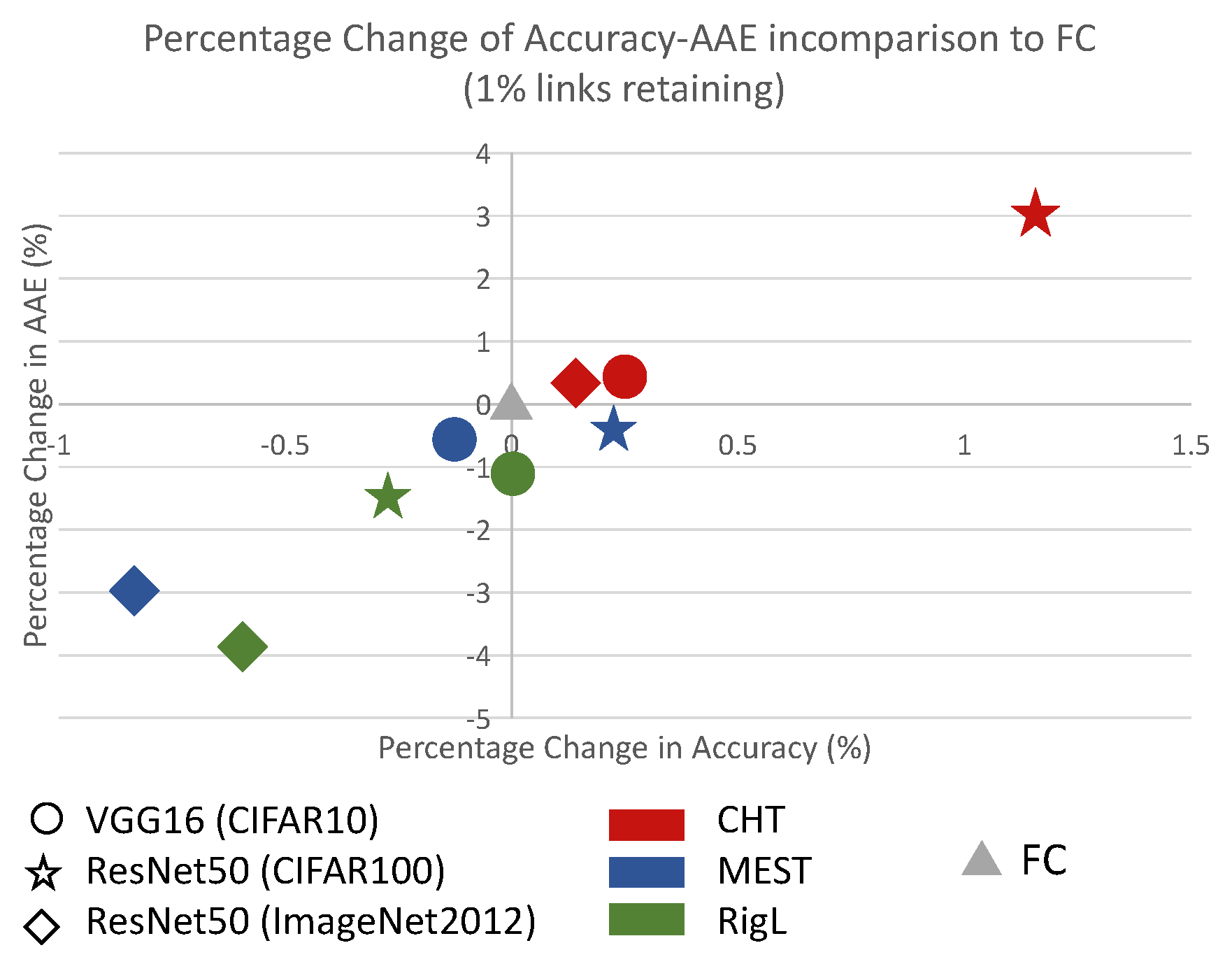

4.3. Results of CHT

4.3.0.6. Main Results.

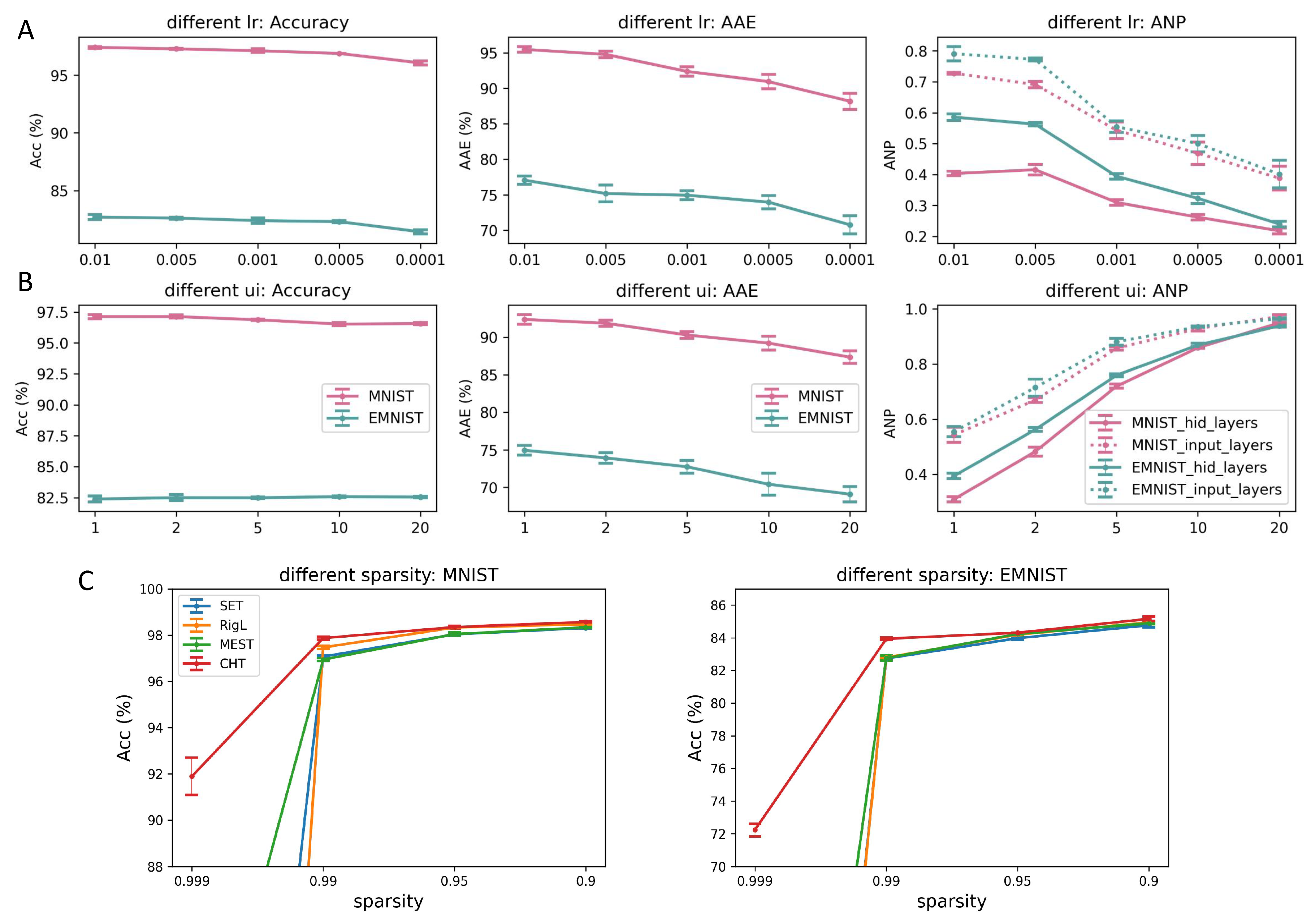

Sparsity.

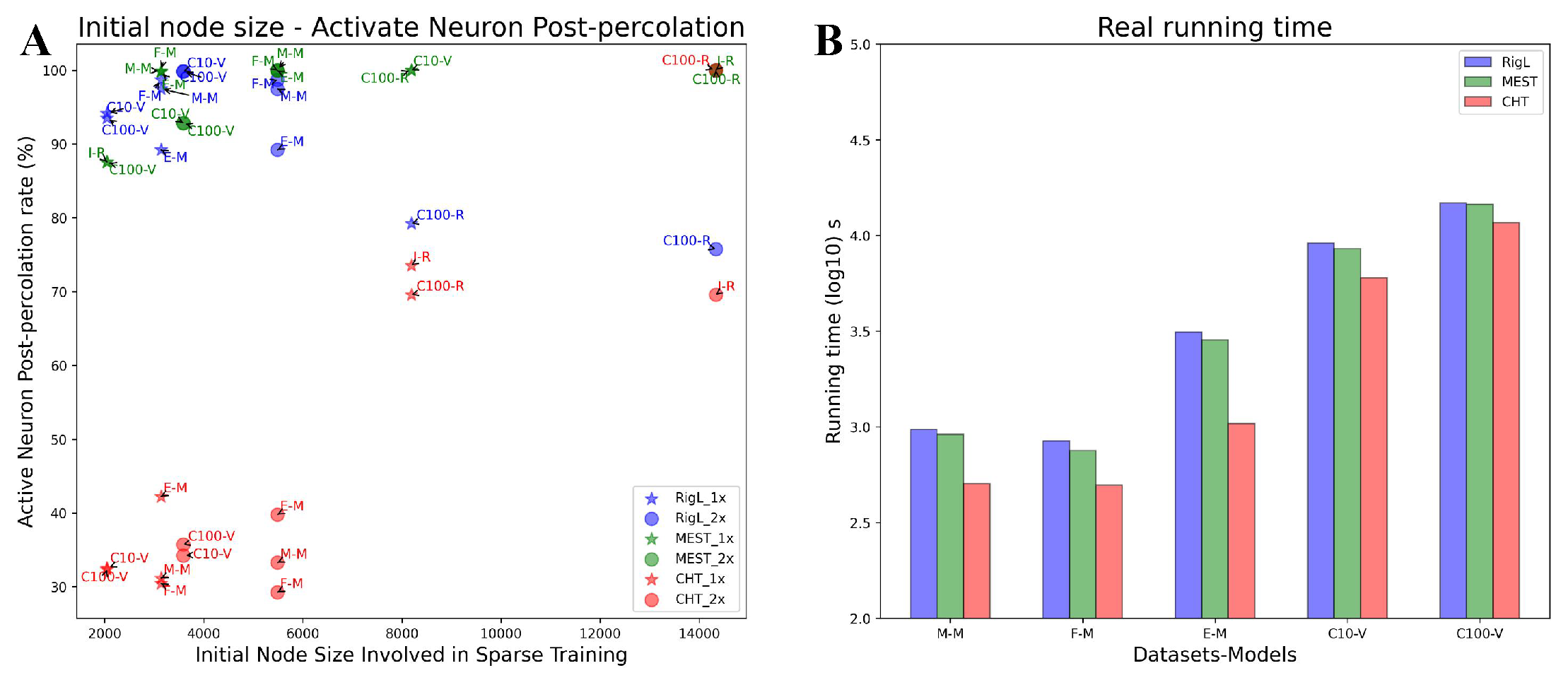

Running time analysis.

Adaptive Percolation.

5. Conclusion

Appendix A Dynamic sparse training

Appendix B Sparse Weight Initialization

Appendix C Limitations and future challenges

Appendix D Link Removal and Network Percolation in ESML

Appendix E Results on the other tasks

| CIFAR10(Vgg16) | CIFAR100(ResNet50) | ImageNet(ResNet50) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC (%) | AAE | ACC (%) | AAE | ACC (%) | AAE | |

| Original_Network | - | - | 79.763 | 68.259 | - | - |

| FC1× | 91.52±0.04 | 87.74±0.03 | 78.297 | 65.527 | 75.042 | 63.273 |

| RigL1× | 91.60±0.10* | 86.54±0.14 | 78.083 | 64.536 | 74.540 | 60.876 |

| MEST1× | 91.65±0.13* | 86.24±0.05 | 78.467* | 65.266 | 74.408 | 61.418 |

| CHT1× | 91.68±0.15* | 86.57±0.08 | 79.203* | 67.512* | 75.134* | 63.538* |

| FC2× | 91.75±0.07 | 87.86±0.02 | 78.490 | 65.760 | 74.911 | 63.517 |

| RigL2× | 91.75±0.03 | 87.07±0.09 | 78.297 | 64.796 | 74.778 | 61.805 |

| MEST2× | 91.63±0.10 | 87.35±0.04 | 78.447 | 64.982 | 74.756 | 62.048 |

| CHT2× | 91.98±0.03* | 88.29±0.10* | 79.253* | 67.370* | 74.936* | 62.998 |

| MNIST(MLP) | Fashion_MNIST(MLP) | EMNIST(MLP) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC (%) | AAE | ACC (%) | AAE | ACC (%) | AAE | |

| FC1× | 98.69±0.02 | 96.33±0.16 | 90.43±0.09 | 87.40±0.02 | 85.58±0.06 | 81.75±0.10 |

| RigL1× | 97.40±0.07 | 93.69±0.10 | 88.02±0.11 | 84.49±0.12 | 82.96±0.04 | 78.01±0.06 |

| MEST1× | 97.31±0.05 | 93.28±0.04 | 88.13±0.10 | 84.62±0.05 | 83.05±0.04 | 78.14±0.07 |

| CHT1× | 98.05±0.04 | 95.45±0.05 | 88.07±0.11 | 85.20±0.06 | 83.82±0.04 | 80.25±0.20 |

| FC2× | 98.73±0.03 | 96.27±0.13 | 90.74±0.13 | 87.58±0.04 | 85.85±0.05 | 82.19±0.12 |

| RigL2× | 97.91±0.09 | 94.25±0.03 | 88.66±0.07 | 85.23±0.08 | 83.44±0.09 | 79.10±0.25 |

| MEST2× | 97.66±0.03 | 94.87±0.09 | 88.33±0.10 | 85.01±0.07 | 83.50±0.09 | 78.31±0.01 |

| CHT2× | 98.34±0.08 | 95.60±0.05 | 88.34±0.07 | 85.53±0.25 | 85.43±0.10 | 81.18±0.15 |

Appendix F Sensitivity test of ESML and CHT

Appendix G Ablation test of each component in CHT

- Correlated Sparse Topology Initialization network properties.

- Correlated sparse topological initialization (CSTI):

- Sparse Weight Initialization (SWI):

- Early stop:

Appendix H Extra experiments setup

Appendix H.1. Hidden dimension

Appendix H.2. Baseline methods

Appendix H.3. Sparsity

Appendix I Area Across the Epochs

Appendix J Subranking strategy of CH3-L3

- Assign a weight to each link in the network, denoted as .

- Compute the shortest paths (SP) between all pairs of nodes in the weighted network.

- For each node pair , compute the Spearman’s rank correlation () between the vectors of all shortest paths from node i and node j.

- Generate a final ranking where node pairs are initially ranked based on the CH score (), and ties are sub-ranked based on the value. If there are still tied scores, random selection is used to rank the node pairs.

| MNIST | Fashion_MNIST | EMNIST | CIFAR10 | CIFAR100(VGG16) | CIFAR100(ResNet50) | ImageNet(ResNet50) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHT1X | 31.15% | 30.45% | 42.22% | 32.52% | 32.32% | 99.98% | 73.54% |

| RigL1X | 97.45% | 98.69% | 89.19% | 94.14% | 93.50% | 79.22% | 36.16% |

| CHT2X | 33.27% | 29.25% | 39.78% | 34.24% | 35.71% | 100% | 69.57% |

| RigL2X | 100% | 100% | 99.82% | 99.83% | 99.80% | 75.74% | 29.67% |

Appendix K Credit Assigned Path

Appendix L Hyperparameter setting and implementation details

Appendix L.1. Hyperparameter setting

Appendix L.2. Algorithm tables of ESML and CHT

Appendix M Annotation in Figure

References

- Muscoloni Alessandro and Cannistraci Carlo Vittorio. Leveraging the nonuniform pso network model as a benchmark for performance evaluation in community detection and link prediction. New Journal of Physics, 20(6):063022, 2018.

- Alberto Cacciola, Alessandro Muscoloni, Vaibhav Narula, Alessandro Calamuneri, Salvatore Nigro, Emeran A Mayer, Jennifer S Labus, Giuseppe Anastasi, Aldo Quattrone, Angelo Quartarone, et al. Coalescent embedding in the hyperbolic space unsupervisedly discloses the hidden geometry of the brain. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.04192, 2017.

- Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci. Modelling self-organization in complex networks via a brain-inspired network automata theory improves link reliability in protein interactomes. Sci Rep, 8(1):2045–2322, 10 2018.

- Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci and Alessandro Muscoloni. Geometrical congruence, greedy navigability and myopic transfer in complex networks and brain connectomes. Nature Communications, 13(1):7308, 2022.

- Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci, Gregorio Alanis-Lobato, and Timothy Ravasi. From link-prediction in brain connectomes and protein interactomes to the local-community-paradigm in complex networks. Scientific reports, 3(1):1613, 2013.

- Gregory Cohen, Saeed Afshar, Jonathan Tapson, and Andre Van Schaik. Emnist: Extending mnist to handwritten letters. In 2017 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), pp. 2921–2926. IEEE, 2017.

- Simone Daminelli, Josephine Maria Thomas, Claudio Durán, and Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci. Common neighbours and the local-community-paradigm for topological link prediction in bipartite networks. New Journal of Physics, 17(11):113037, nov 2015. URL. [CrossRef]

- Claudio Durán, Simone Daminelli, Josephine M Thomas, V Joachim Haupt, Michael Schroeder, and Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci. Pioneering topological methods for network-based drug–target prediction by exploiting a brain-network self-organization theory. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 19(6):1183–1202, 04 2017. URL. [CrossRef]

- Utku Evci, Trevor Gale, Jacob Menick, Pablo Samuel Castro, and Erich Elsen. Rigging the lottery: Making all tickets winners. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2020, 13-18 July 2020, Virtual Event, volume 119 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2943–2952. PMLR, 2020. URL http://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/evci20a.html.

- Elias Frantar and Dan Alistarh. Massive language models can be accurately pruned in one-shot. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.00774, 2023.

- Hugh G Gauch Jr, Hugh G Gauch, and Hugh G Gauch Jr. Scientific method in practice. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Xavier Glorot and Yoshua Bengio. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Yee Whye Teh and D. Mike Titterington (eds.), Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, AISTATS 2010, Chia Laguna Resort, Sardinia, Italy, May 13-15, 2010, volume 9 of JMLR Proceedings, pp. 249–256. JMLR.org, 2010. URL http://proceedings.mlr.press/v9/glorot10a.html.

- Babak Hassibi, David G Stork, and Gregory J Wolff. Optimal brain surgeon and general network pruning. In IEEE international conference on neural networks, pp. 293–299. IEEE, 1993.

- Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 1026–1034, 2015.

- Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 770–778, 2016.

- Donald Hebb. The organization of behavior. emphnew york, 1949.

- Itay Hubara, Brian Chmiel, Moshe Island, Ron Banner, Joseph Naor, and Daniel Soudry. Accelerated sparse neural training: A provable and efficient method to find n: m transposable masks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:21099–21111, 2021.

- Alex Krizhevsky. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. pp. 32–33, 2009. URL https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf.

- Yann LeCun, John S. Denker, and Sara A. Solla. Optimal brain damage. In David S. Touretzky (ed.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2, [NIPS Conference, Denver, Colorado, USA, November 27-30, 1989], pp. 598–605. Morgan Kaufmann, 1989. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/250-optimal-brain-damage.

- Yann LeCun, Léon Bottou, Yoshua Bengio, and Patrick Haffner. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE, 86(11):2278–2324, 1998. URL. [CrossRef]

- Namhoon Lee, Thalaiyasingam Ajanthan, and Philip H. S. Torr. Snip: single-shot network pruning based on connection sensitivity. In 7th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2019, New Orleans, LA, USA, May 6-9, 2019. OpenReview.net, 2019. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=B1VZqjAcYX.

- Jiajun Li and Ahmed Louri. Adaprune: An accelerator-aware pruning technique for sustainable cnn accelerators. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing, 7(1):47–60, 2021.

- Ming Li, Run-Ran Liu, Linyuan Lü, Mao-Bin Hu, Shuqi Xu, and Yi-Cheng Zhang. Percolation on complex networks: Theory and application. Physics Reports, 907:1–68, 2021.

- Linyuan Lü, Liming Pan, Tao Zhou, Yi-Cheng Zhang, and H. Eugene Stanley. Toward link predictability of complex networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(8):2325–2330, 2015.

- Asit Mishra, Jorge Albericio Latorre, Jeff Pool, Darko Stosic, Dusan Stosic, Ganesh Venkatesh, Chong Yu, and Paulius Micikevicius. Accelerating sparse deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08378, 2021.

- Decebal Constantin Mocanu, Elena Mocanu, Peter Stone, Phuong H Nguyen, Madeleine Gibescu, and Antonio Liotta. Scalable training of artificial neural networks with adaptive sparse connectivity inspired by network science. Nature communications, 9(1):1–12, 2018.

- A. Muscoloni, U. Michieli, and C.V. Cannistraci. Adaptive network automata modelling of complex networks. preprints, 2020. URL. [CrossRef]

- Alessandro Muscoloni and Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci. A nonuniform popularity-similarity optimization (npso) model to efficiently generate realistic complex networks with communities. New Journal of Physics, 20(5):052002, 2018.

- Alessandro Muscoloni and Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci. Angular separability of data clusters or network communities in geometrical space and its relevance to hyperbolic embedding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.00025, 2019.

- Vaibhav et al Narula. Can local-community-paradigm and epitopological learning enhance our understanding of how local brain connectivity is able to process, learn and memorize chronic pain? Applied network science, 2(1), 2017.

- Mark EJ Newman. Clustering and preferential attachment in growing networks. Physical review E, 64(2):025102, 2001.

- Christopher L Rees, Keivan Moradi, and Giorgio A Ascoli. Weighing the evidence in peters’ rule: does neuronal morphology predict connectivity? Trends in neurosciences, 40(2):63–71, 2017.

- Carlos Riquelme, Joan Puigcerver, Basil Mustafa, Maxim Neumann, Rodolphe Jenatton, André Susano Pinto, Daniel Keysers, and Neil Houlsby. Scaling vision with sparse mixture of experts. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:8583–8595, 2021.

- Olga Russakovsky, Jia Deng, Hao Su, Jonathan Krause, Sanjeev Satheesh, Sean Ma, Zhiheng Huang, Andrej Karpathy, Aditya Khosla, Michael Bernstein, Alexander C. Berg, and Li Fei-Fei. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. International Journal of Computer Vision (IJCV), 115(3):211–252, 2015.

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014.

- Mingjie Sun, Zhuang Liu, Anna Bair, and J Zico Kolter. A simple and effective pruning approach for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.11695, 2023.

- Han Xiao, Kashif Rasul, and Roland Vollgraf. Fashion-mnist: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.07747, 2017.

- Mengqiao Xu, Qian Pan, Alessandro Muscoloni, Haoxiang Xia, and Carlo Vittorio Cannistraci. Modular gateway-ness connectivity and structural core organization in maritime network science. Nature Communications, 11(1):2849, 2020.

- Geng Yuan, Xiaolong Ma, Wei Niu, Zhengang Li, Zhenglun Kong, Ning Liu, Yifan Gong, Zheng Zhan, Chaoyang He, Qing Jin, et al. Mest: Accurate and fast memory-economic sparse training framework on the edge. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:20838–20850, 2021.

- Geng Yuan, Yanyu Li, Sheng Li, Zhenglun Kong, Sergey Tulyakov, Xulong Tang, Yanzhi Wang, and Jian Ren. Layer freezing & data sieving: Missing pieces of a generic framework for sparse training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.11204, 2022.

- Y. Zhang, H. Bai, H. Lin, J. Zhao, L. Hou, and C.V. Cannistraci. An efficient plug-and-play post-training pruning strategy in large language models. preprints, 2023a. URL. [CrossRef]

- Yuxin Zhang, Mingbao Lin, Mengzhao Chen, Fei Chao, and Rongrong Ji. Optg: Optimizing gradient-driven criteria in network sparsity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.12826, 2022.

- Yuxin Zhang, Yiting Luo, Mingbao Lin, Yunshan Zhong, Jingjing Xie, Fei Chao, and Rongrong Ji. Bi-directional masks for efficient n: M sparse training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06058, 2023b.

| 1 | A video that shows the ESML percolation of the network across the epochs for the example of Figure 2A is provided at this link https://shorturl.at/blGY1

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).