Submitted:

13 January 2023

Posted:

16 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Design

3. Construction, Making and Working

3.1. Temperature and Energy Flux in a Fission Device

3.2. Ignition Problem

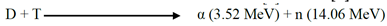

3.2.1. Ignition Temperature

3.2.2. Lawson Criteria

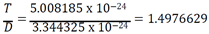

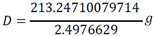

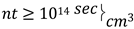

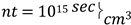

. At ignition temperature ~5 𝑥 107K with

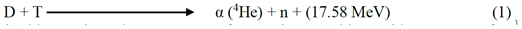

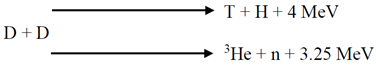

. At ignition temperature ~5 𝑥 107K with  , For DD reaction,

, For DD reaction,

3.3. Devices—Type and Configurations

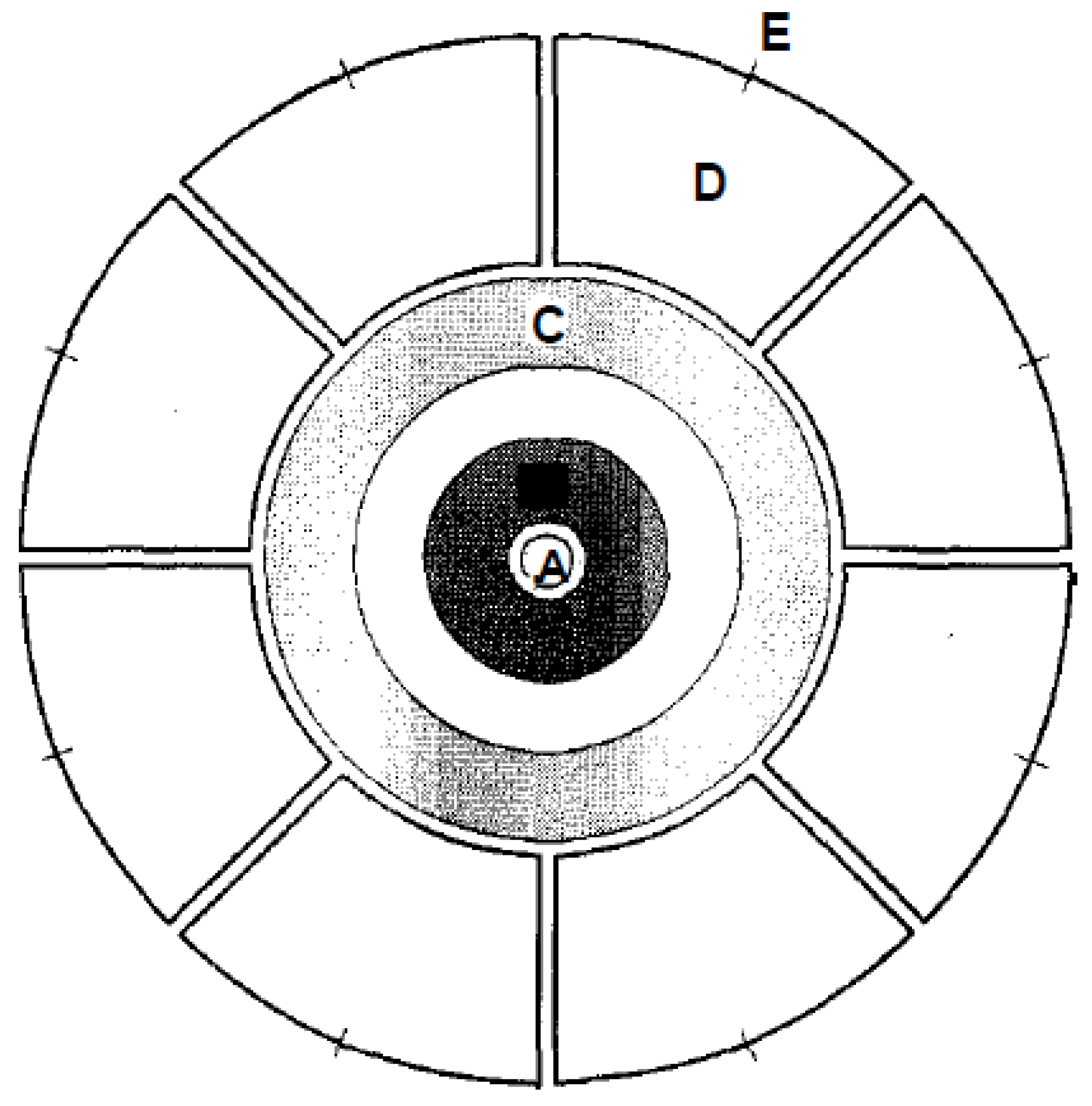

3.3.1. Ordinary Device

3.3.2. Booster Device

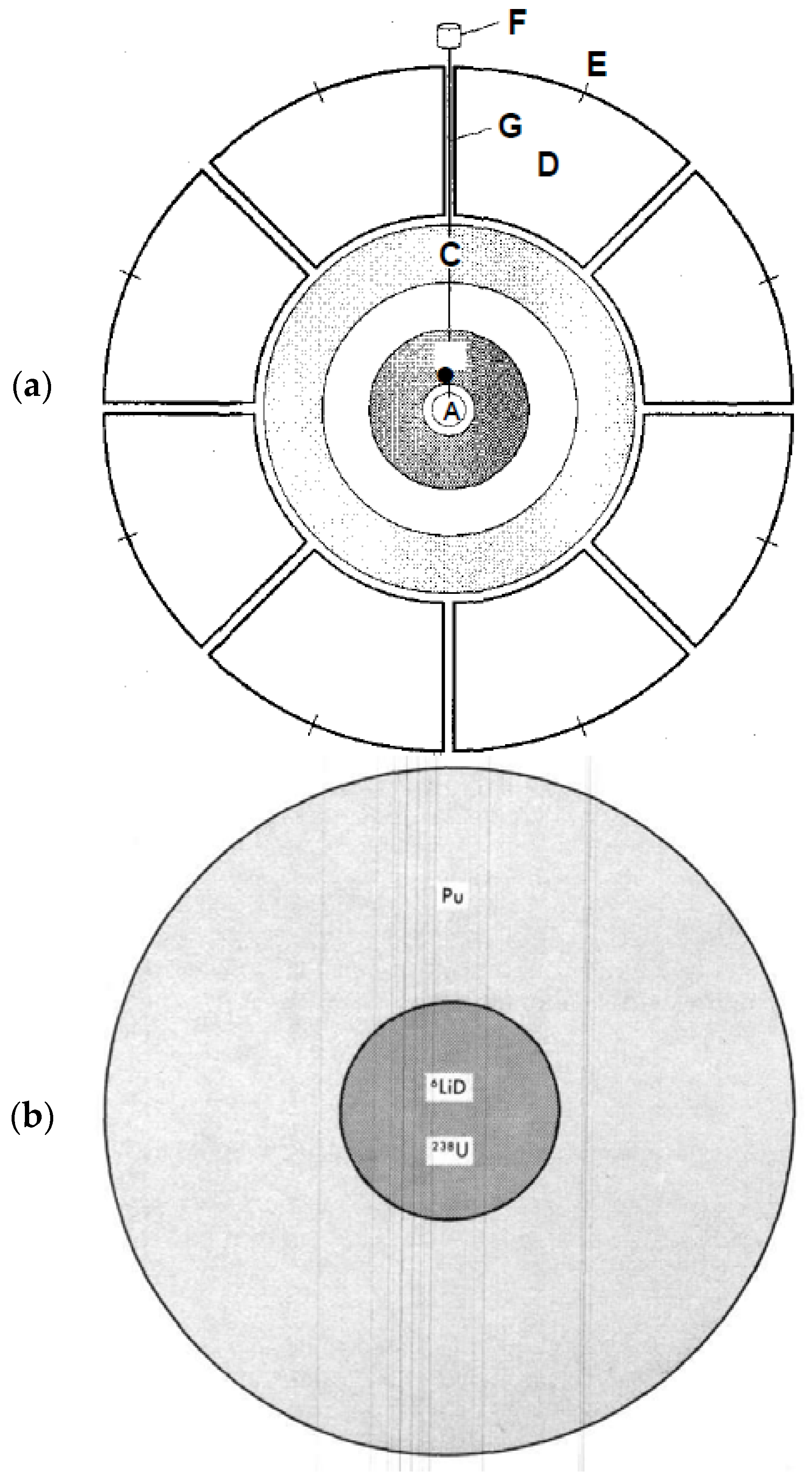

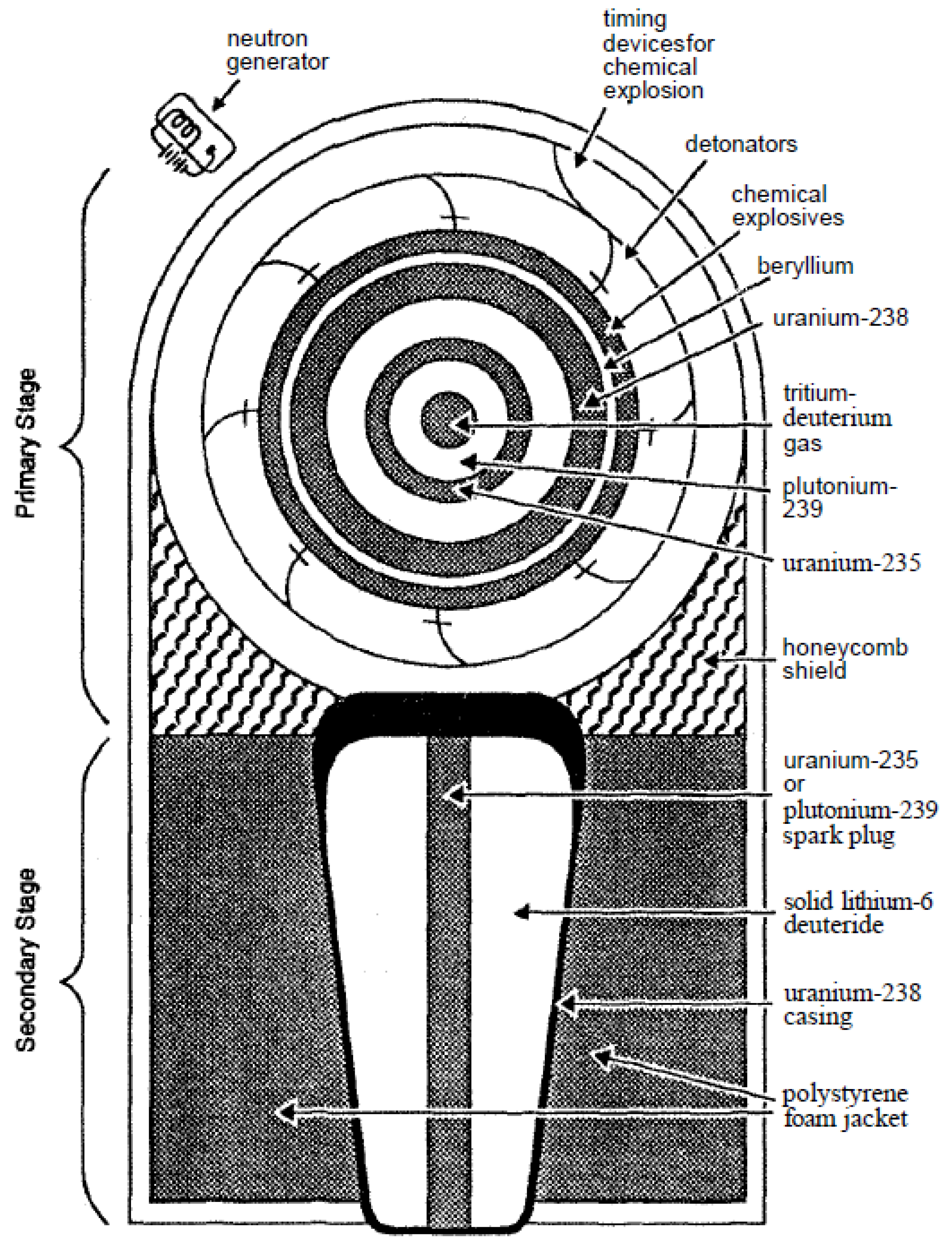

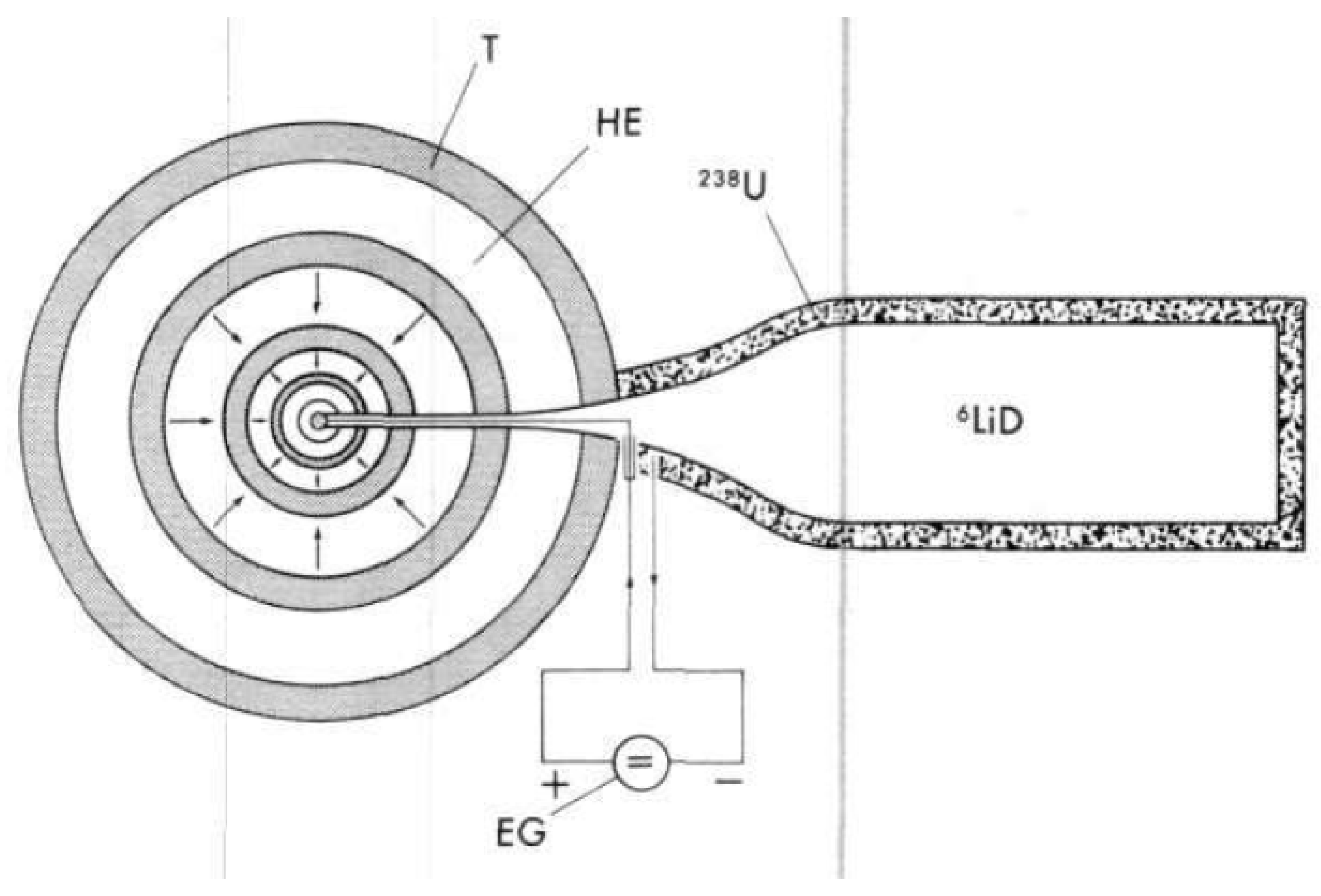

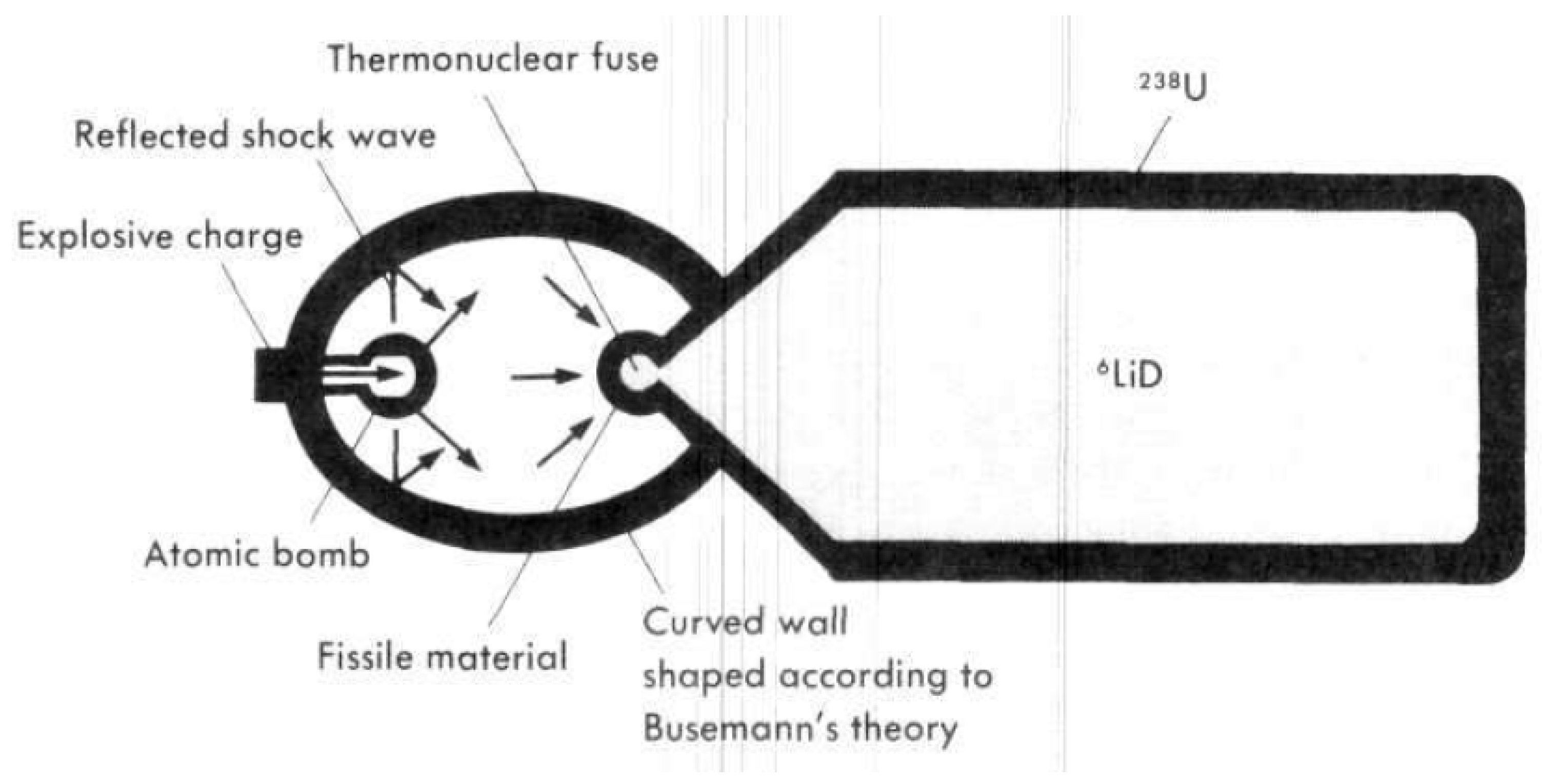

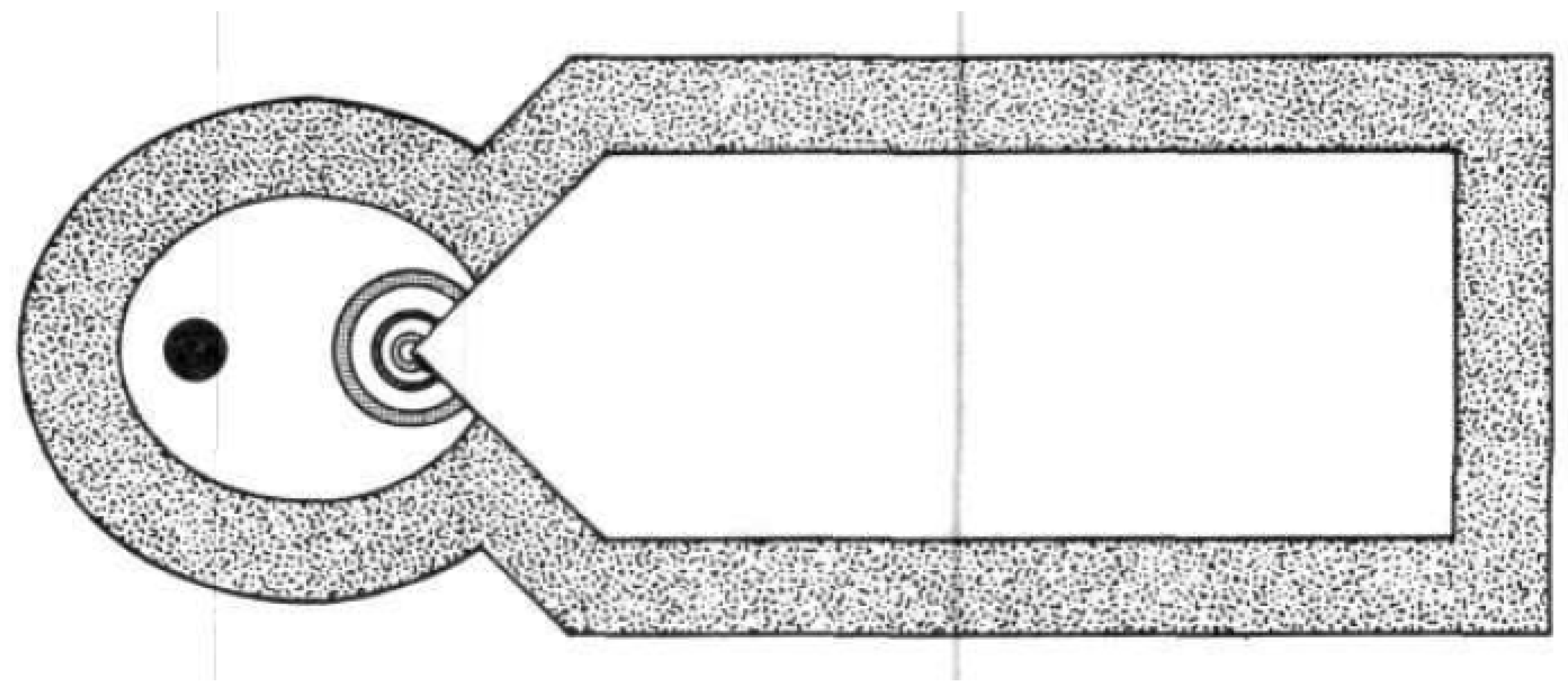

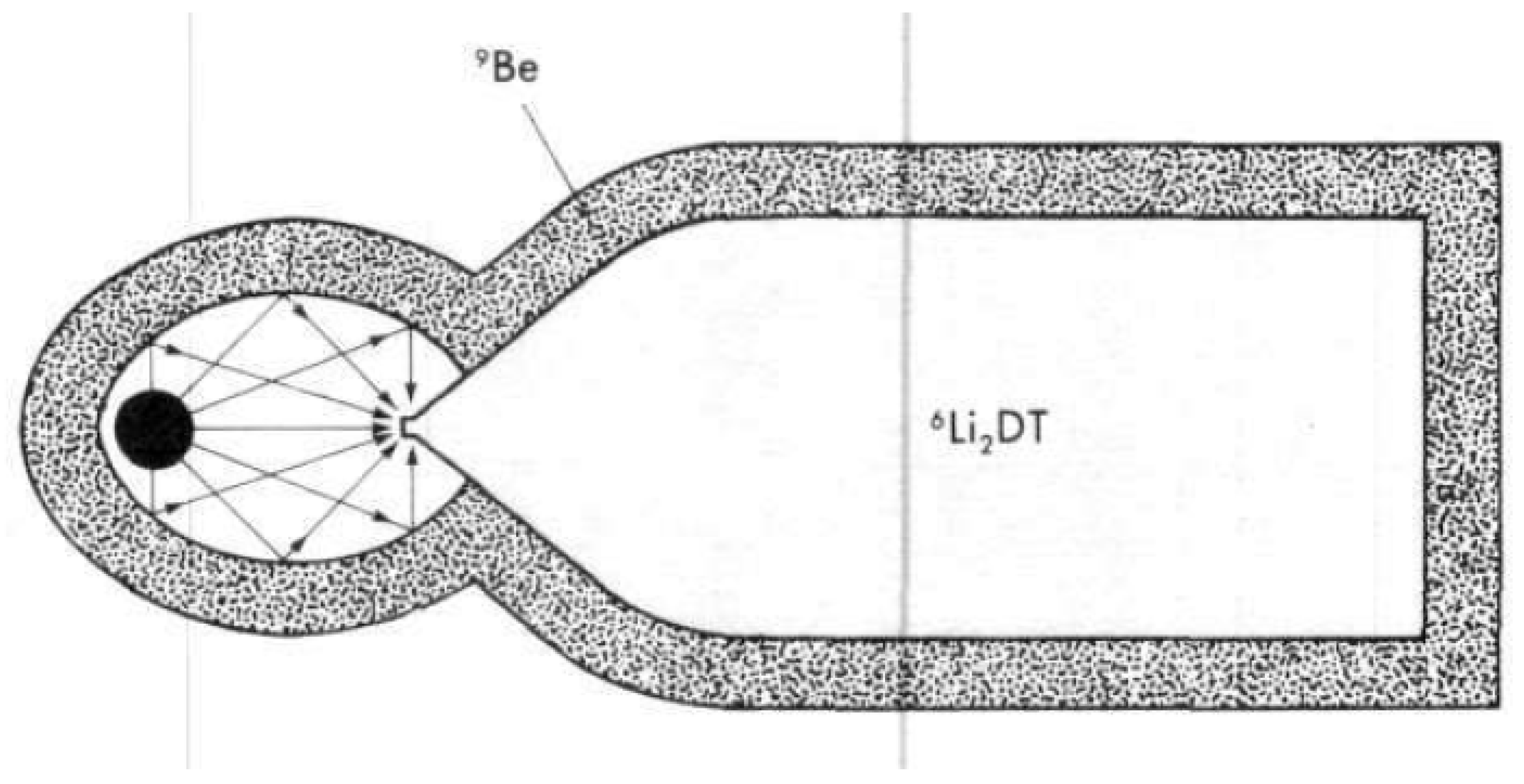

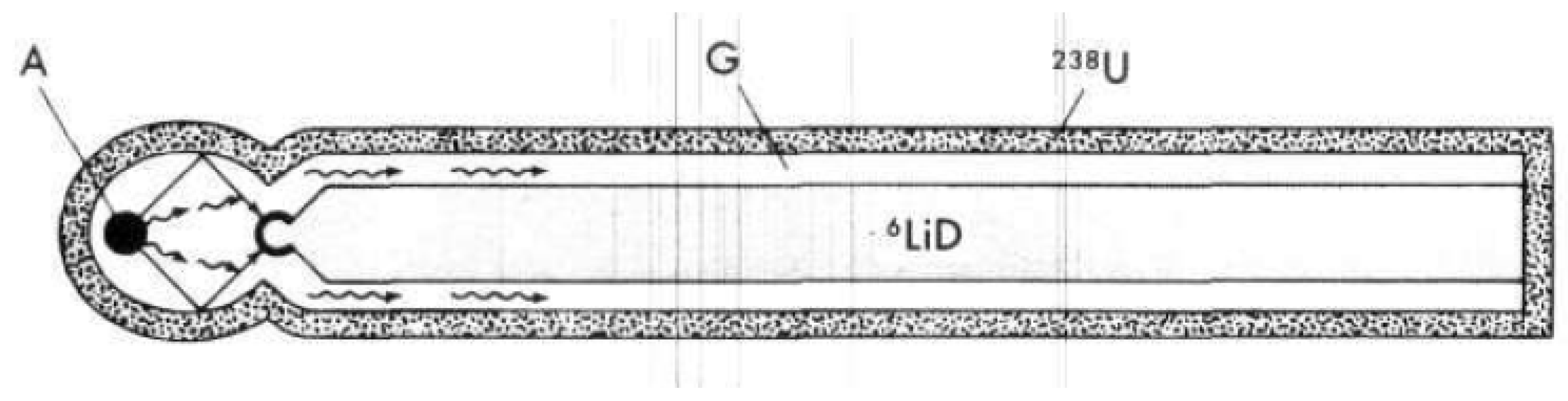

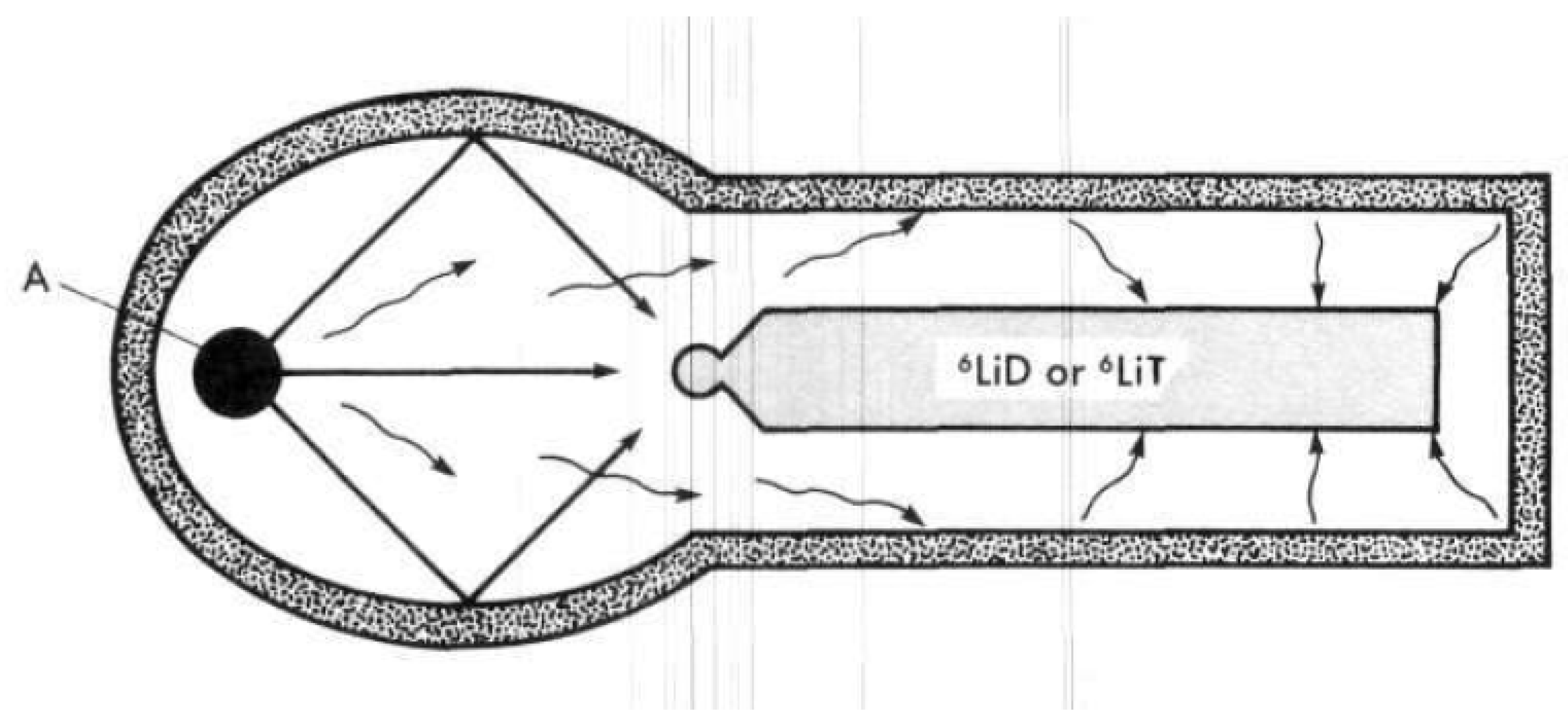

3.3.3. Two Stage, Modified Teller—Ulm or Mike Ivy Configuration

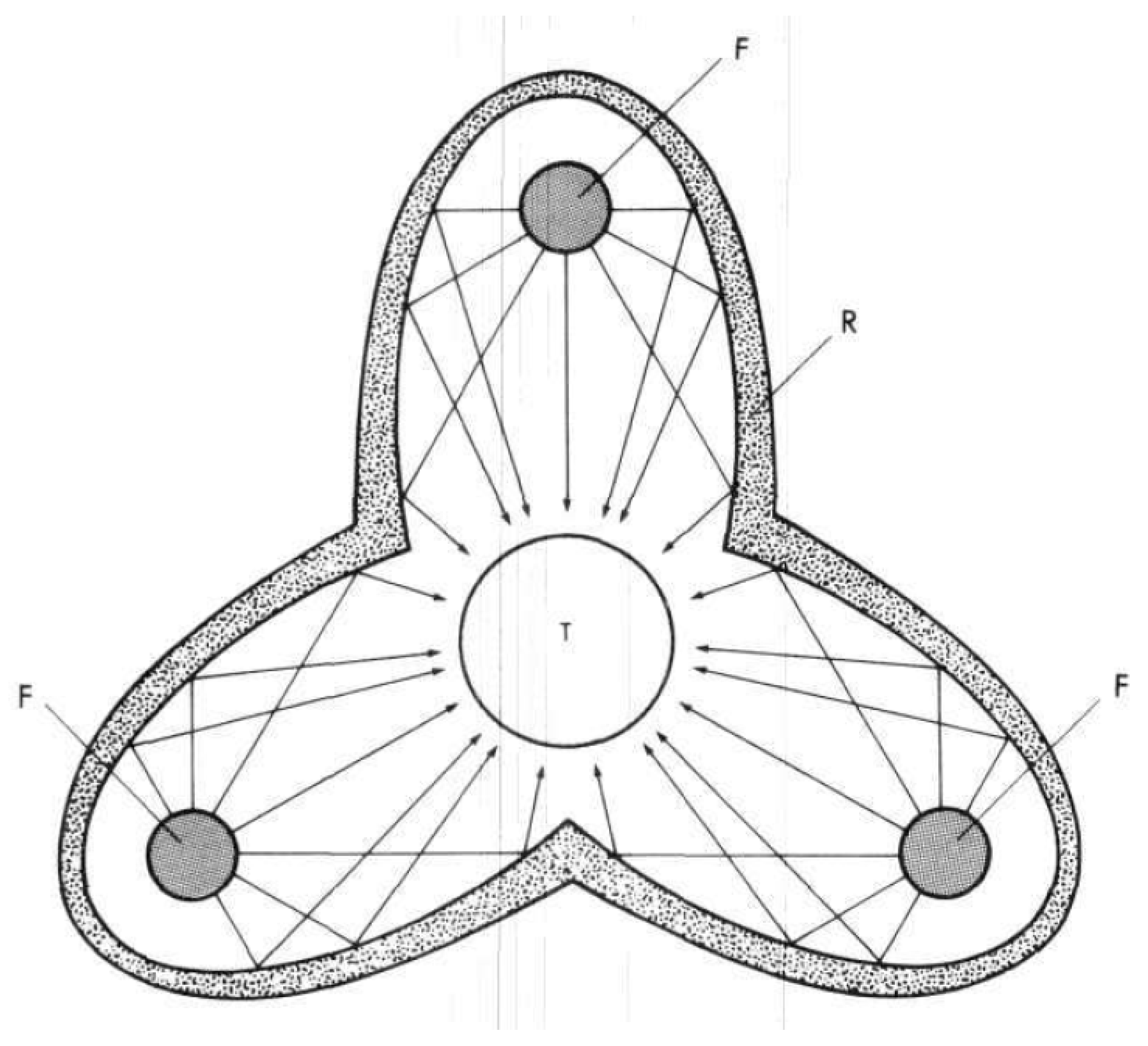

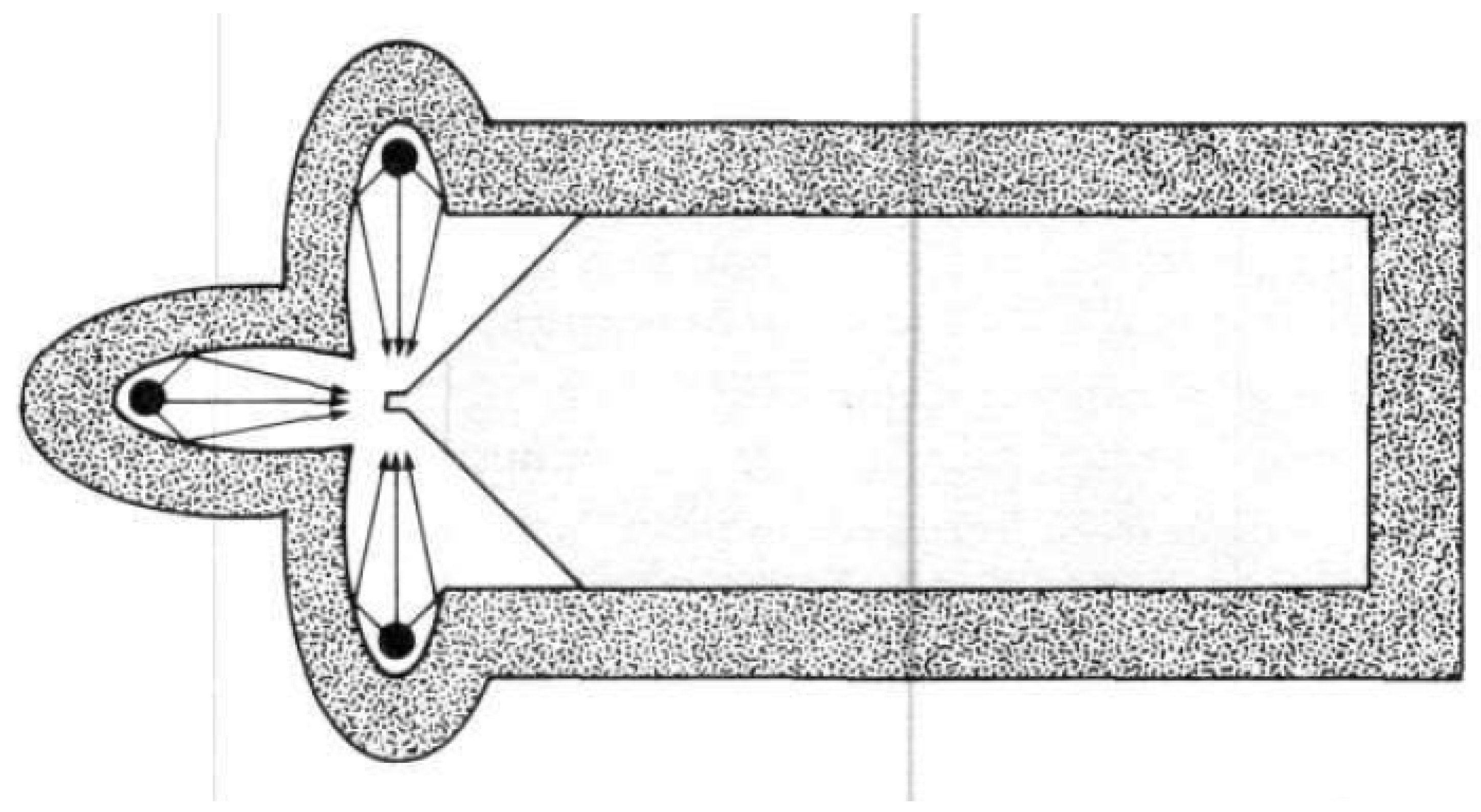

3.3.4. Polyhedron Configuration

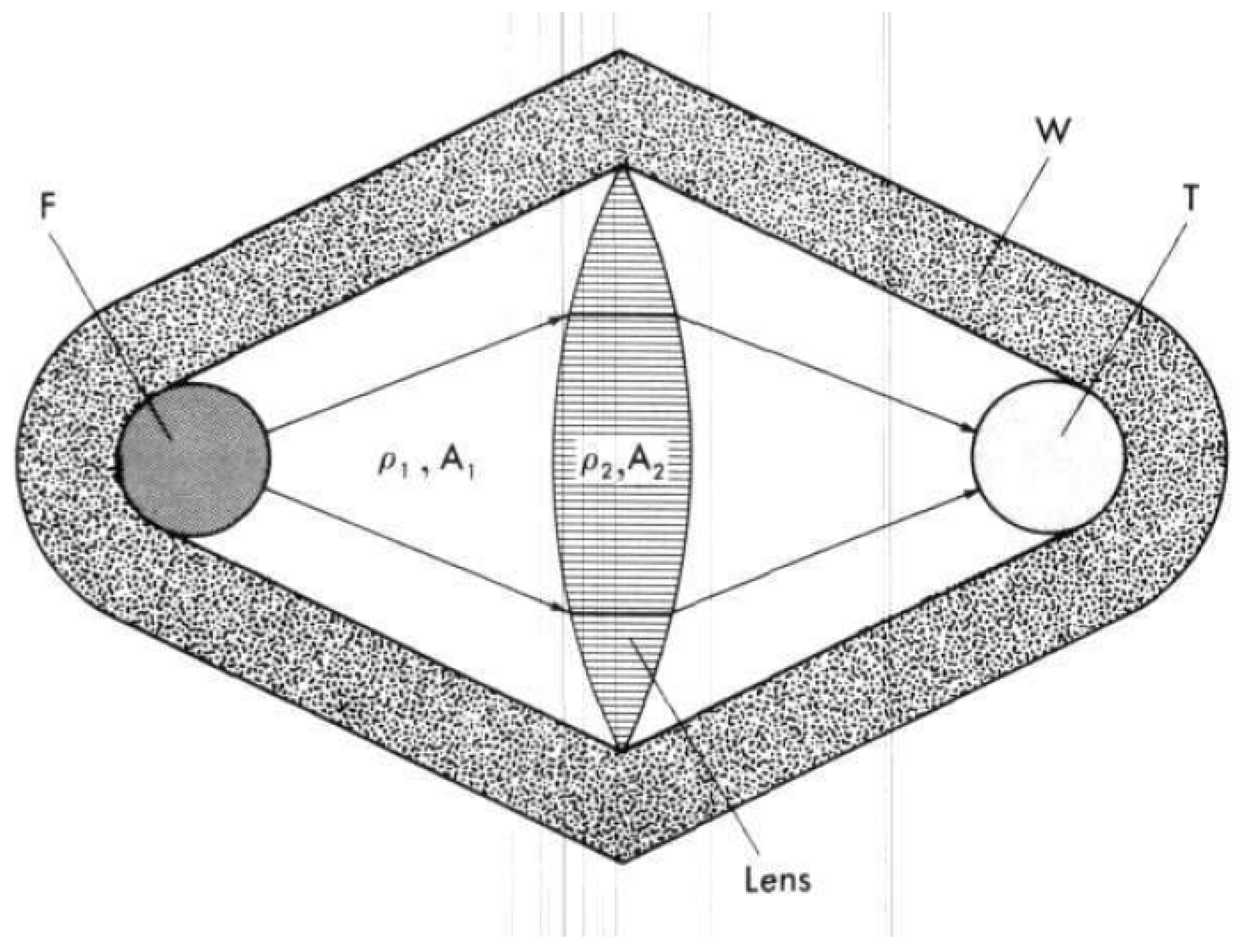

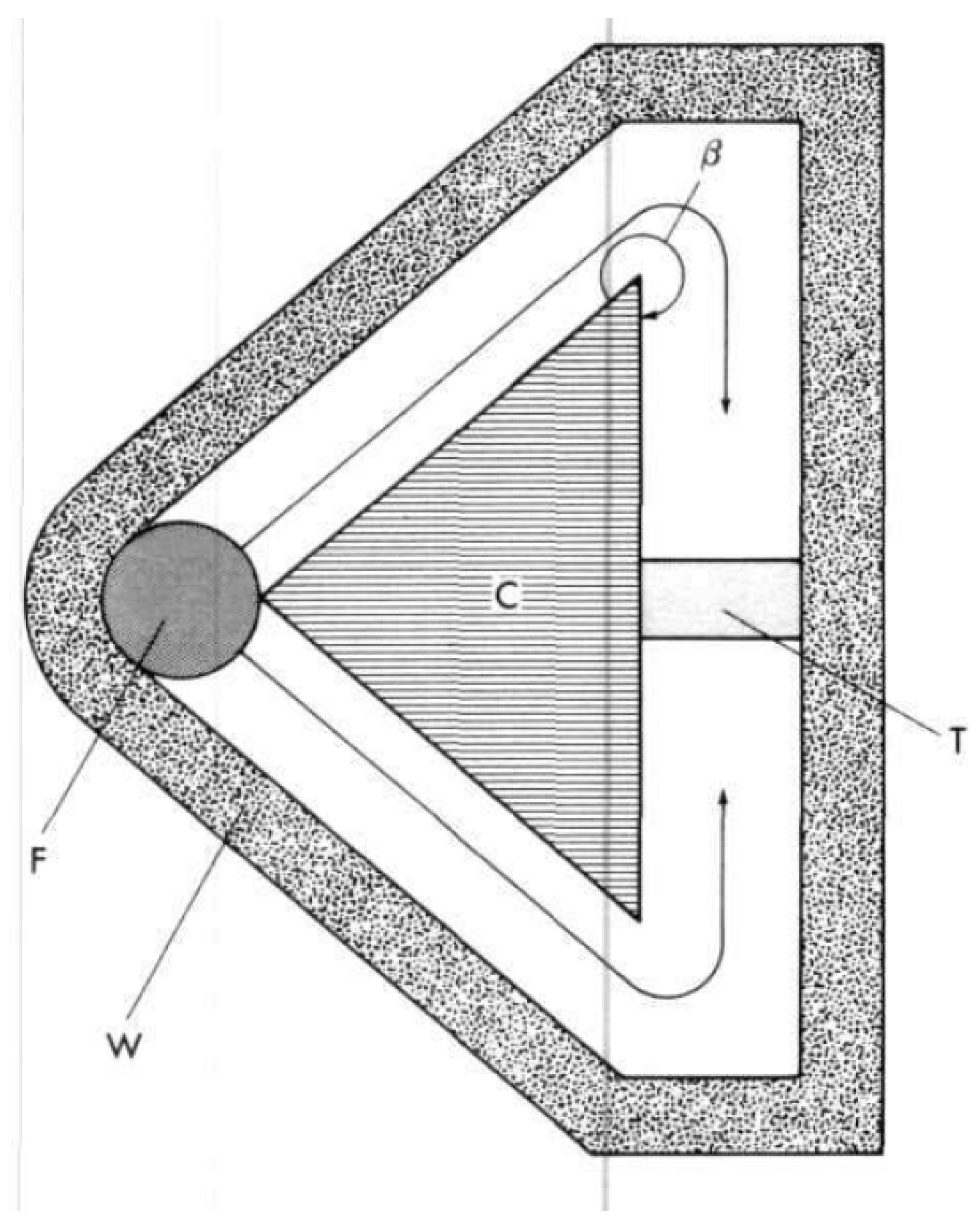

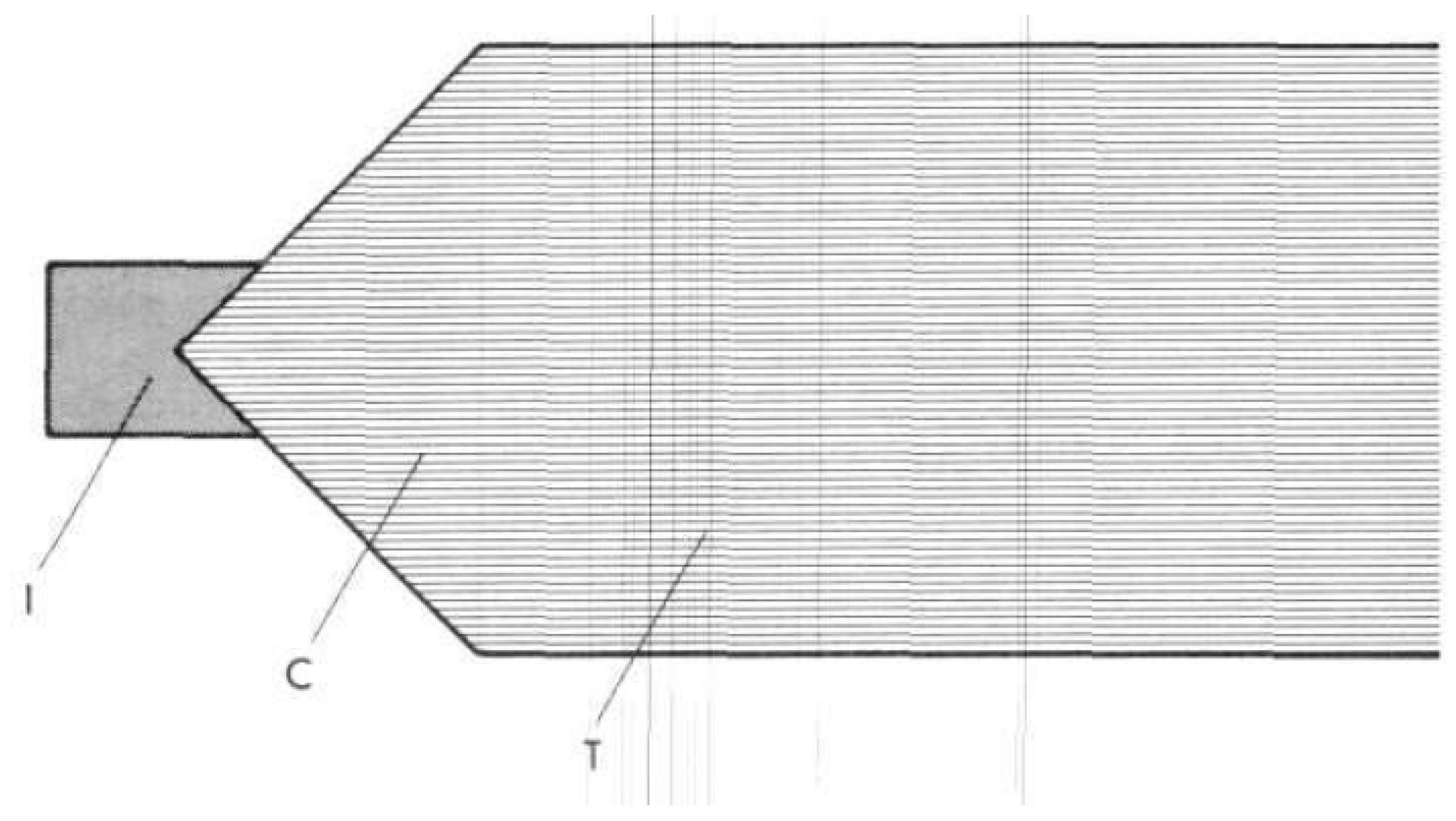

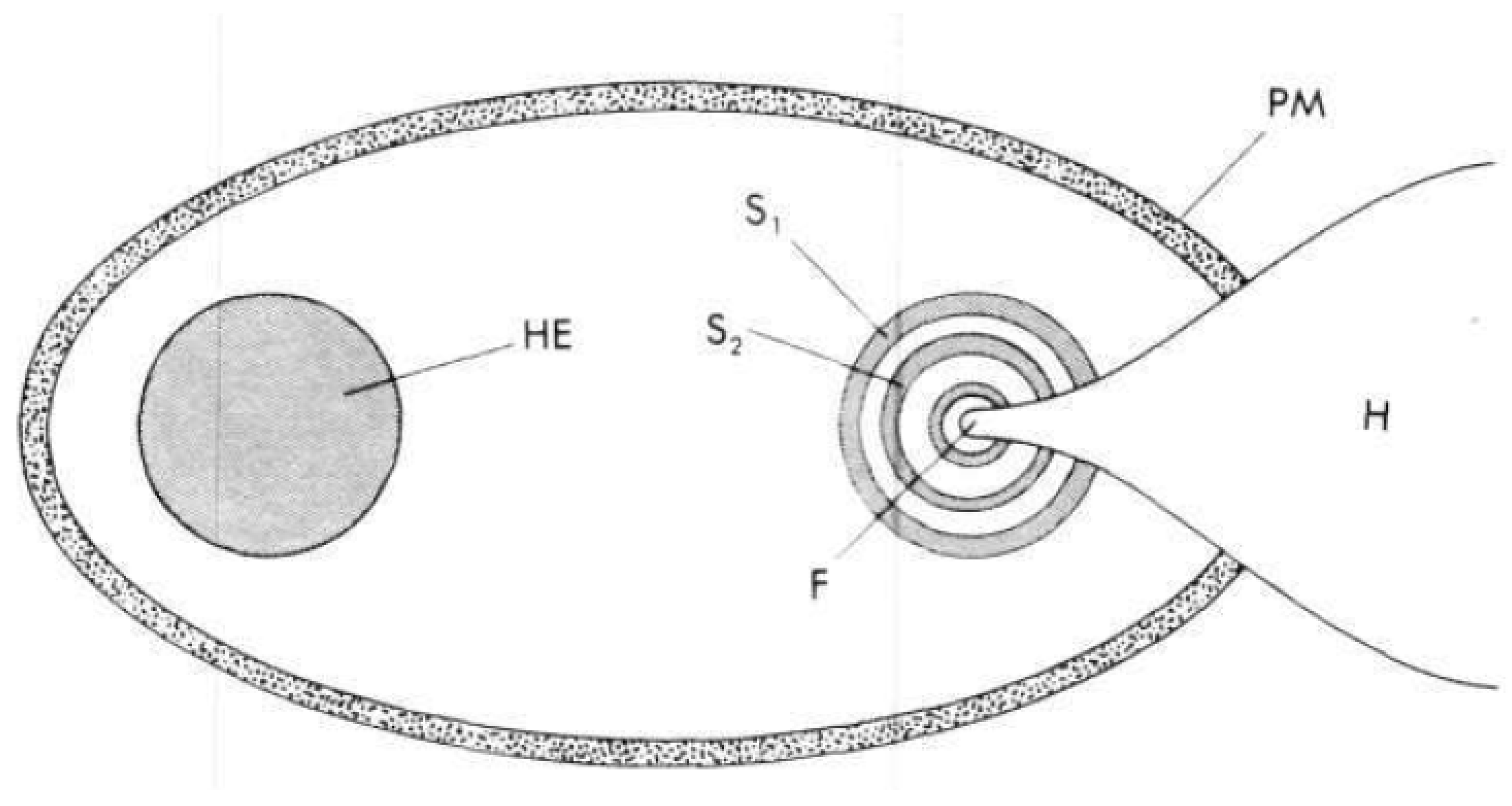

3.3.5. Ignition by Implosion (Prandtl-Meyer Configuration)

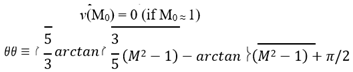

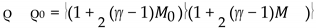

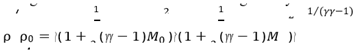

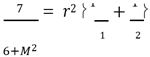

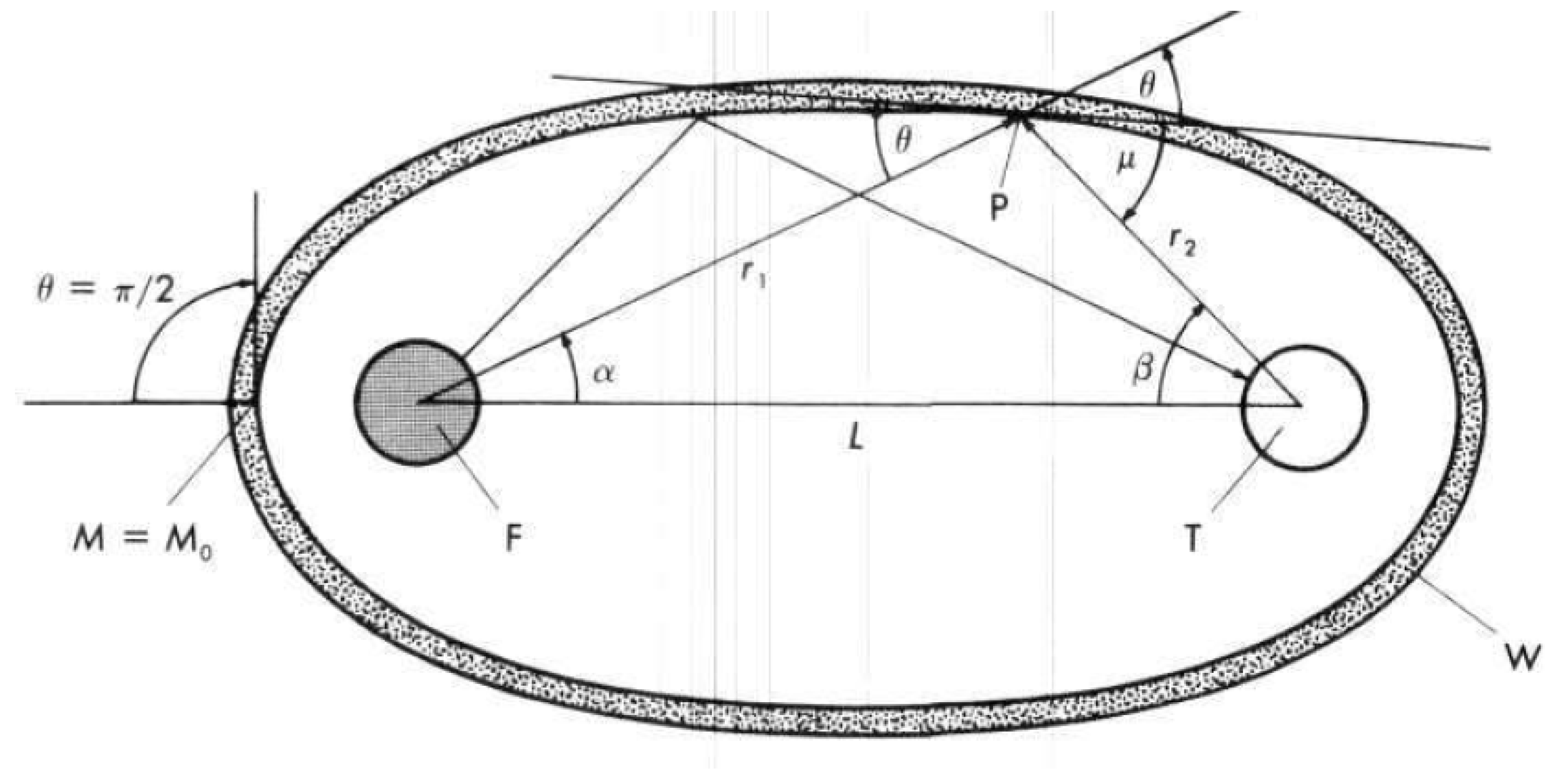

3.3.5.1. Determination of Wall Shape of Ellipsoid

and

and

from (9) and (10)

from (9) and (10)

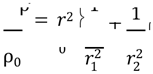

3.4. Shock Wave Focusing—Other Configurations

, condition 𝜌2 = 𝜌1

, condition 𝜌2 = 𝜌1

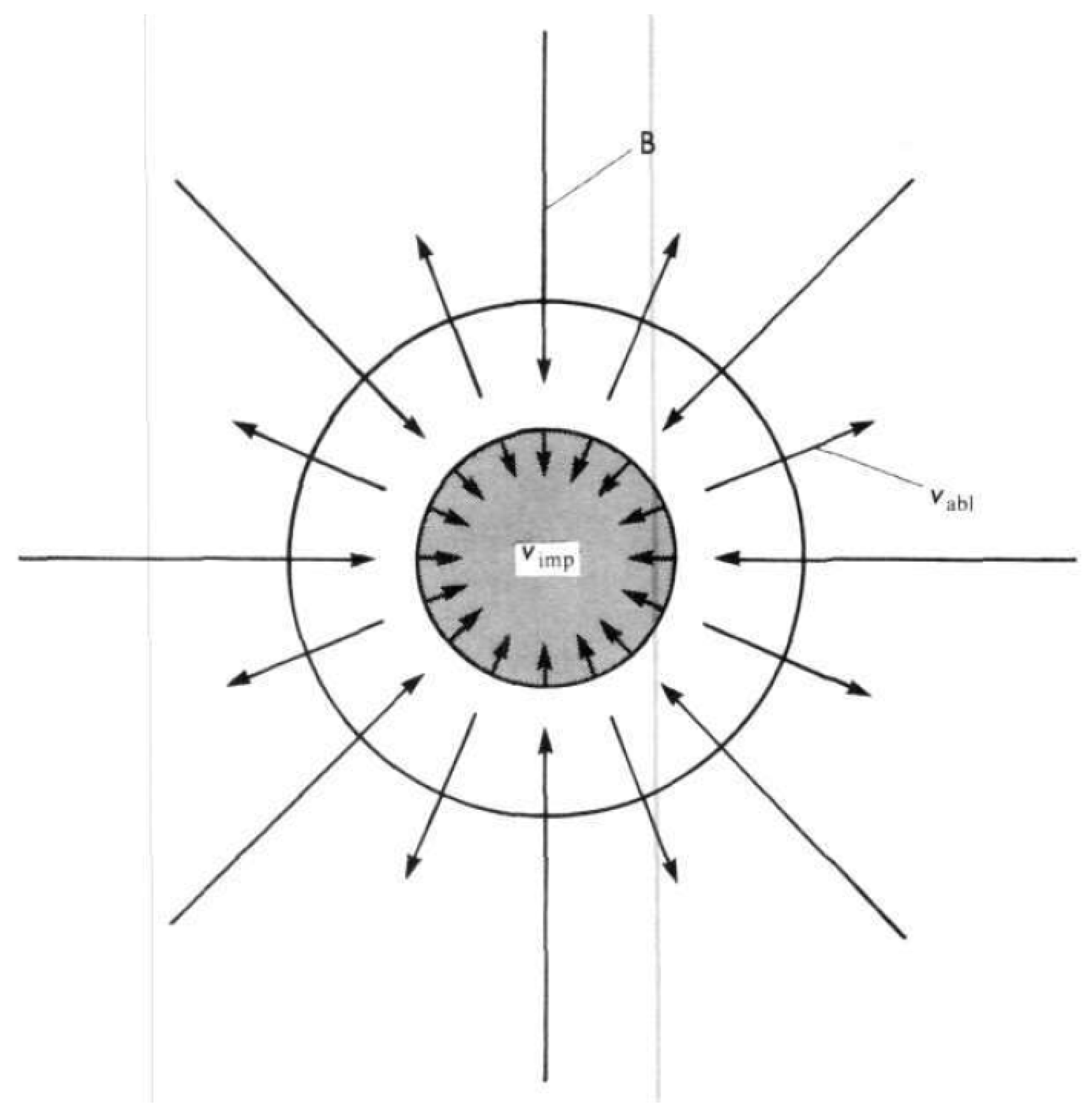

3.5.. Non Fission Ignition (Chemical Ignition) and Ablation

3.6. Lasers, Ion Beams and FGNW

3.7. Deployment

3.8. Detonation

4. Conclusion

References

- Winterberg, F., The Release of Thermonuclear Energy by Inertial Confinement: Ways Towards Ignition. 2010: World Scientific.

- Winterberg, F., General Relativistic Modification of the Lockheed Compact Fusion Reactor Concept. Fusion Science and Technology, 2020. 76: p. 141 - 144. [CrossRef]

- Gsponer, A., Fourth Generation Nuclear Weapons: Military effectiveness and collateral effects. 2005.

- Siracusa, J.M., Nuclear Weapons: A Very Short Introduction. 2008: OUP Oxford.

- Winterberg, F. and F.E. Foundation, The Physical Principles of Thermonuclear Explosive Devices. 1981: Fusion Energy Foundation.

- Winterberg, F.M. On Thermonuclear Micro-Bomb Propulsion for Fast Interplanetary Missions. 2013.

- Winterberg, F.M., Nuclear microbomb propulsion for manned deep space exploration with return travel. Acta Astronautica, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., Matter–antimatter gigaelectron volt gamma ray laser rocket propulsion. Acta Astronautica, 2012. 81(1): p. 34-39. [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.M.A., Materials for Outer Shell of 1.170 GWh (1.00669 Kilo Ton TNT) Fusion Device-Weight Basis. 2021.

- Gsponer, A. and J.P. Hurni. The physical principles of thermonuclear explosives , inertial confinement fusion , and the quest for fourth generation nuclear weapons. 2010.

- Barnaby, F., How to Build a Nuclear Bomb: And Other Weapons of Mass Destruction. 2004: Nation Books.

- Sandel, F.L., et al., Focusing of fast plasma shock waves. The Physics of Fluids, 1975. 18(8): p. 1075-1076. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., Ignition by shock wave focusing and staging of thermonuclear microexplosions. Nature, 1975. 258(5535): p. 512-514. [CrossRef]

- RAIZER, I. and I. ZELDOVICH, Physics of Shock Waves and High- Temperature Hydrodynamic Phenomena. Volume 1(Physics of shock waves and high temperature hydrodynamic phenomena, Volume 1). 1966.

- Lazarus, R. and R. Richtmyer, Report la-6823-ms. Los Alamos Sci. Lab, 1977. 680.

- Sharma, V.D. and C. Radha, Similarity solutions for converging shocks in a relaxing gas. International Journal of Engineering Science, 1995. 33(4): p. 535-553. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.H.T., R.A. Neemeh, and P.P. Ostrowski, Experimental Studies of the Production of Converging Cylindrical Shock Waves. AIAA Journal, 1980. 18(1): p. 47-48. [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.B., A numerical method for a converging cylindrical shock. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 1957. 2(2): p. 185- 200. [CrossRef]

- Shabouei, M., R. Ebrahimi, and K.M. Body, Numerical solution of cylindrically converging shock waves. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.02680, 2016.

- Takayama, K., H. Kleine, and H. Grönig, An experimental investigation of the stability of converging cylindrical shock waves in air. Experiments in Fluids, 1987. 5(5): p. 315-322. [CrossRef]

- Kinney, G.F. and K.J. Graham, Explosive Shocks in Air. 1985: Springer, Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Stoner, R.G. and W. Bleakney, The Attenuation of Spherical Shock Waves in Air. Journal of Applied Physics, 1948. 19(7): p. 670-678. [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, V., et al., Light emission during shock wave focusing in air and argon. Physics of Fluids, 2007. 19(10): p. 106106. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, H. and W. Gretler, The propagation of spherical and cylindrical shock waves in real gases. Physics of Fluids, 1994. 6(6): p. 2154-2164. [CrossRef]

- VonNeumann, J. and R.D. Richtmyer, A Method for the Numerical Calculation of Hydrodynamic Shocks. Journal of Applied Physics, 1950. 21(3): p. 232-237. [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.W. and A. Kantrowitz, The Production and Stability of Converging Shock Waves. Journal of Applied Physics, 1951. 22(7): p. 878-886. [CrossRef]

- Dyke, M.V. and A.J. Guttmann, The converging shock wave from a spherical or cylindrical piston. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 1982. 120: p. 451-462.

- Ramsey, S.D. and R.S. Baty, Piston driven converging shock waves in a stiffened gas. Physics of Fluids, 2019. 31(8): p. 086106. [CrossRef]

- Guderley, K., Starke kugelige und zylindrische verdichtungsstosse in der nahe des kugelmitterpunktes bnw. der zylinderachse. Luftfahrtforschung, 1942. 19: p. 302.

- Nath, G. and S. Singh, Similarity solutions for magnetogasdynamic cylindrical shock wave in rotating ideal gas using Lie Group theoretic method: Isothermal flow. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics, 2020. 17(08): p. 2050123.

- Brode, H.L., Numerical Solutions of Spherical Blast Waves. Journal of Applied Physics, 1955. 26(6): p. 766-775. [CrossRef]

- Brode, H.L., Blast Wave from a Spherical Charge. The Physics of Fluids, 1959. 2(2): p. 217-229. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C., et al., Effect of explosive charge geometry on shock wave propagation. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2018. 1979(1): p. 150021.

- Winterberg, F., Thermonuclear microexplosion ignition by imploding a disk of relativistic electrons. Physics of Plasmas, 1995. 2(3): p. 733-740. [CrossRef]

- Tabak, M., et al., Ignition and high gain with ultrapowerful lasers*. Physics of Plasmas, 1994. 1(5): p. 1626-1634. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., Laser Ignition of an Isentropically Compressed Dense Z-Pinch. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A, 1999. 54(8-9): p. 459-464. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., Thermonuclear micro-explosions with intense ion beams. Nature, 1974. 251(5470): p. 44-46. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., Adiabatic wall focusing of intense ion beams for the ignition of thermonuclear microexplosions. Zeitschrift für Physik A Atoms and Nuclei, 1977. 282(1): p. 3-6. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., Production of dense thermonuclear plasmas by intense ion beams. Plasma Physics, 1975. 17(1): p. 69- 77. [CrossRef]

- Winterberg, F., The Possibility of Producing a Dense Thermonuclear Plasma by an Intense Field Emission Discharge. Physical Review, 1968. 174(1): p. 212-220. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).