Submitted:

04 October 2023

Posted:

10 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Advantages of the Autonomous Vehicle Compared to the Traditional Ones

- Every year approximately 1.25 million vehicle accidents occur globally, leading to a substantial loss of lives. In the United States, car accidents alone claim the lives of over individuals on an annual basis [2]. The main causes of such accidents are drowsiness, incapacitation, inattention, or intoxication [3]. According to advocates, most traffic accidents (more than ) are caused by human errors. Autonomous vehicles can address these issues by introducing a zero-human error approach, relying on computer-controlled systems to eliminate many of the mistakes that human drivers make on the road and improving safety for both passengers and pedestrians, while reducing loss of life and property damage.

- Enhanced Traffic Flow and Reliability: Due to limited human perception and reaction speeds, effectively utilising highway capacity becomes a challenge. Self-driving vehicles, being computer-controlled and interconnected, can enhance efficiency and alleviate congestion. This means that the existing roads will be able to accommodate more vehicles. With increased carrying capacity on current roadways, the need for constructing new roads or expanding existing ones to handle congestion will diminish. Consequently, the land designated for roads and parking can be repurposed for commercial and residential use. Additionally,the widespread adoption of self-driving cars in the transportation system can decrease traffic delays and accidents, leading to improved overall reliability [2].

- Environmental Advantages: With the advent of self-driving cars, the transportation system becomes safer and more dependable. Consequently, there is an opportunity to redesign vehicles, shifting away from heavy, tank-like models to lighter counterparts, which consume less fuel. Furthermore, self-driving concepts are also fostering the development of electric vehicles (EVs) and other alternative propulsion technologies. This collective reduction in fuel consumption promises to deliver significant environmental benefits that are highly valued, including a reduction in gas emissions and improved air quality.

- Mobility for Non-drivers: Self-driving cars provide an opportunity for non-drivers (e.g., young, old, impaired, disabled, and people who do not possess a driving license) to have personal mobility [2].

- Reduced Driver Stress: A study involving 49 participants has demonstrated that the self-driving environment induces less stress compared to traditional driving [4]. This suggests that self-driving cars have the potential to improve overall well-being by reducing the workload and the associated stress of driving, as noted in a study by Parida et al. [2].

- The advent of self-driving cars is expected to significantly decrease the number of required parking spaces, particularly in the United States, by over 5.7 billion square meters, as reported by Parida et al. [2]. Several factors contribute to this improvement, including the elimination of the need for open-door space for self-parking vehicles, as there is no human driver who needs to exit the vehicle. As a result, vehicles can be parked more closely together, achieving an approximate 15% increase in parking density.

- Additional Time for Non-Driving Activities: Self-driving cars provide additional time for non-driving activities, enabling individuals to save up to approximately 50 minutes per day that would otherwise be spent on driving activities. This newfound time can be invested in work, relaxation, or entertainment.

- The concept of "mobility-on-demand" is gaining popularity in large cities, and self-driving vehicles are poised to support this feature. Through the deployment of self-driving taxis, private vehicle ride-sharing, buses, and trucks, high-demand routes can be efficiently served. Shared mobility has the potential to reduce vehicle ownership by up to while increasing travel per vehicle by up to .

- Real-Time Situational Awareness: Self-driving cars have the capability to utilise real-time traffic data, including travel time and incident reports. This enables them employing sophisticated navigation systems and efficient vehicle routing, resulting in improved performance and informed decision-making on the road, [2].

- Multidisciplinary Design Optimisation: Multidisciplinary design optimization (MDO) is a research field that explores the use of numerical optimization methods to design engineering systems based on multiple disciplines, such as structural analysis, aerodynamics, materials science, and control systems. MDO is widely used to design automobiles, aircraft, ships, space vehicles, electro-chemical systems, and more, with the goal of improving performance while minimizing weight and cost [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. With the advancement of computational power, MDO frameworks can also be used for autonomous vehicles to improve their structural design, aerodynamics, powertrain optimization, sensor integration and placement, path planning, control system optimization, and energy management. There has been significant research into making vehicles lightweight without compromising their strength and safety, with composite materials being a popular choice for this purpose [14,15,16].

1.2. The Intersection between Self-Driving Cars and Electric Vehicles (EVs)

1.3. Why Self-Driving Cars Became Possible Due to the Development of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

1.4. Statistical Predictions about Expansion of Self-Driving Cars Industry in Near Future

| Authors | Year | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Yurtsever et al. [22] | 2019 | Autonomous vehicles, control, robotics, automation, intelligent vehicles, intelligent transportation systems |

| Liu et al. [23] | 2021 | Cooperative Autonomous Driving, IAAD, IGAD, IPAD |

| Huang et al. [24] | 2020 | deep learning, perception, mapping, localization, planning, control, prediction, simulation, V2X, safety, uncertainty, CNN, RNN, LSTM, GRU, GAN, simulation learning, reinforcement learning |

| Malik et al. [25] | 2021 | cooperative driving, collaboration, lane change, platooning, leader election |

| Contreras-Castillo et al. [26] | 2019 | Autonomous Car Stakeholders, Autonomy Models |

2. Research and Development in AI and Control Strategies in the Field of Self-Driving Cars

3. Multi-Task Learning and Meta Learning

3.1. Conditioning Task Descriptor

3.1.1. Concatenation

3.1.2. Additive Conditioning

3.1.3. Multi-head Architecture

3.1.4. Multiplicative Conditioning

3.2. Objective Optimization

- Sample Mini Batch

- Sample Mini Batch Datapoints for each task

- Compute Loss on Mini Batch

- Compute Gradient via Backpropagation

- Optimize using Gradient information

3.3. Action Prediction

- Model-based Prediction

- Driven-based Prediction

- Lane sequence-based predictions

- Recurrent neural networks

3.4. Depth and Flow Estimation

- Stereo Scenes

- Monocular Scenes [86]

3.5. Behavior Prediction of Nearby Objects

3.6. One Shot Learning

- ‘Probabilistic models’ using ‘Bayesian learning’

- ‘Generative models’ deploying ‘probability density functions’

- Images transformation

- Memory augmented neural networks

- Meta learning

- Metric learning exploiting ‘convolutional neural networks (CNN)’ [99]

3.7. Few Shot Learning

- Some methods use data to enhance supervised experience by using previously acquired knowledge

- Some methods use model to minimize the dimensions of hypothesis space by deploying previously acquired knowledge

- Others use previous knowledge to facilitate algorithm which helps in searching of optimal hypothesis present in given space [103]

4. Modular Pipeline

4.1. Sensor Fusion

-

Exteroceptive Sensors: They mainly sense the external environment and measure distances to different traffic objects. The following technologies can be used as an exteroceptive sensor in self-driving cars.

- -

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging): LiDAR can measure distances to different objects remotely by using energy-emitting sensors. It sends a pulse of laser and then senses “Time Of Fight (TOF)”, by which pulse comes back.

- -

- Radar: Radar can sense distances to different objects along with their angle and velocity, by using electromagnetic radiation or radio waves.

- -

- Camera: A camera builds up a digital image by using passive light sensors. It can detect static as well as dynamic objects in the surroundings.

- -

- Ultrasonic: An Ultrasonic sensor also calculates distances to neighboring objects by using sound waves.

-

Proprioceptive Sensors: They calculate different system values of the vehicle itself, such as the position of the wheels, the angles of the joints, and the speed of the motor.

- -

- GPS (Global Positioning System): GPS provides geolocation as well as time information all over the world. It is a radio-navigation system based on satellites.

- -

- IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit): The IMU calculates an object’s force, magnetic field, and angular rate.

- -

- Encoders: It is an electro-mechanical instrument which takes an angular or linear shaft’s position as its input and generates a corresponding digital or analogue signal as its output.

- Vision - LiDAR/Radar: It is used for modelling of surroundings, vehicle localization as well as object detection.

- Vision – LiDAR: It can track dynamic objects by deploying LiDAR technology and a stereo camera.

- GPS-IMU: This system is developed for absolute localization by employing GPS, IMU and DR (Dead Reckoning).

- RSSI-IMU: This algorithm is suitable for indoor localization, featuring RSSI (Received Signal Strength Indicator), WLAN (Wireless Local Area Network) and IMU [109].

4.2. Localization

- GNSS-RTk: GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) deploys 30 GPS satellites, which are being positioned in space at 20,000 km away from earth. RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) navigation system is also based on satellites and provides accurate position data.

- Inertial navigation: This system is also used for localization and uses motion sensors such as accelerometers, rotational sensors like gyroscopes, and a processing device for computations.

- LIDAR localization: LIDAR sensor provides 3D point clouds, containing information about surroundings. Localization is being performed by incessantly exposing and matching LIDAR data with HD maps. Algorithms used to test point clouds are “Iterative Closet Point (ICP)” and “Filter Algorithms (such as Kalman filter)”.

4.3. Planning and Control

- Path planning / generation: An appropriate path for vehicle is being planned. If a car needs to change the lane, it must be planned carefully without any accidental scenario.

- Speed planning / generation: It calculates the suitable speed of the vehicle. It also measures the speeds and distances of neighboring cars and utilizes this information in speed planning.

- The Routing module gets destination data from the user and generates a suitable route accordingly by investigating road networks and maps.

- The behavioral planning module receives route information from the routing module and inspects applicable traffic rules and develops motion specifications.

- The motion planner receives both route information and motion specifications. It also exhibits localization and perception information. By utilising all provided information, it generates trajectories.

- Finally, the control system receives these developed trajectories and plans the car’s motion. It also emends all execution errors in the planned movements in a reactive way.

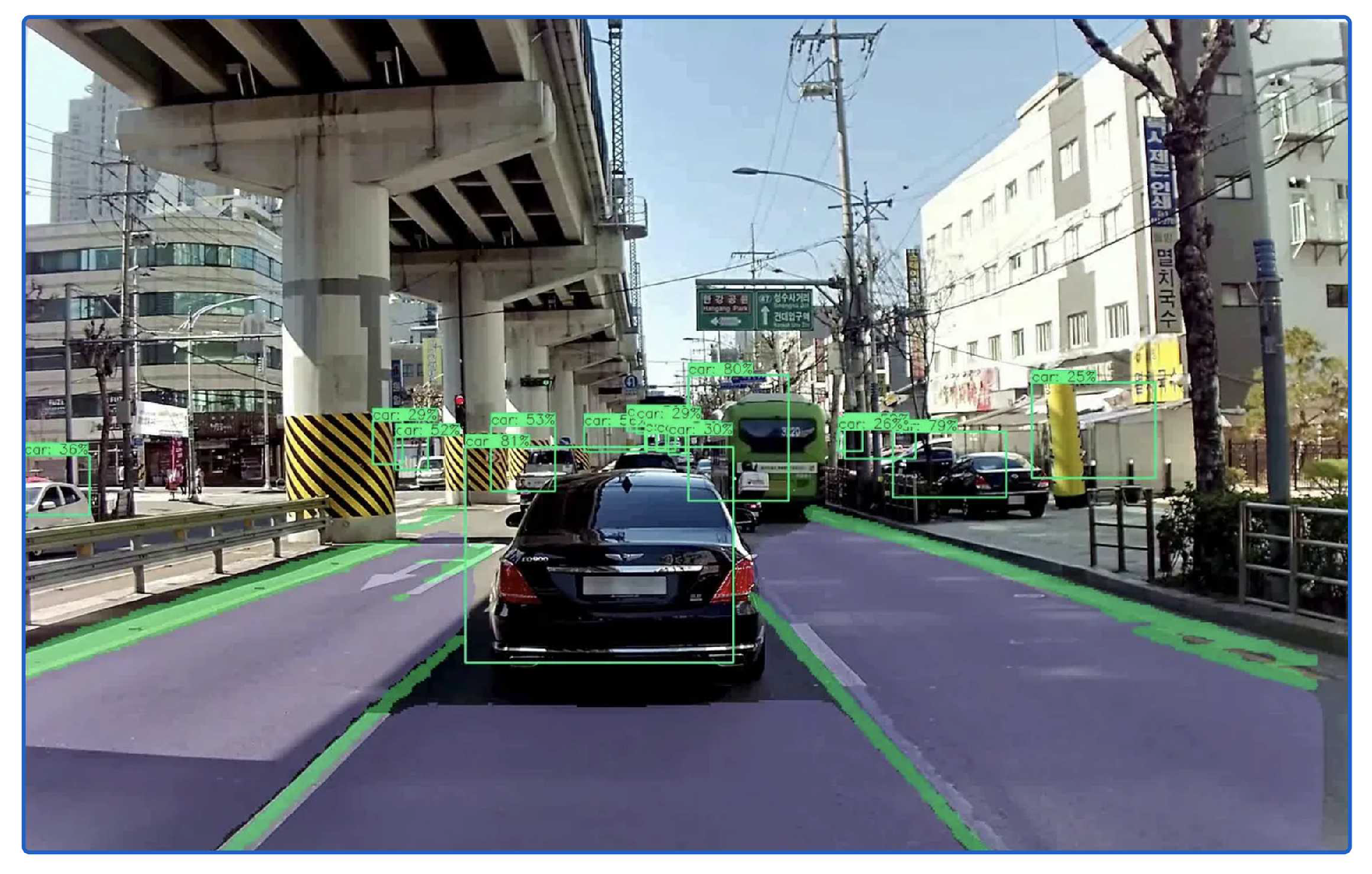

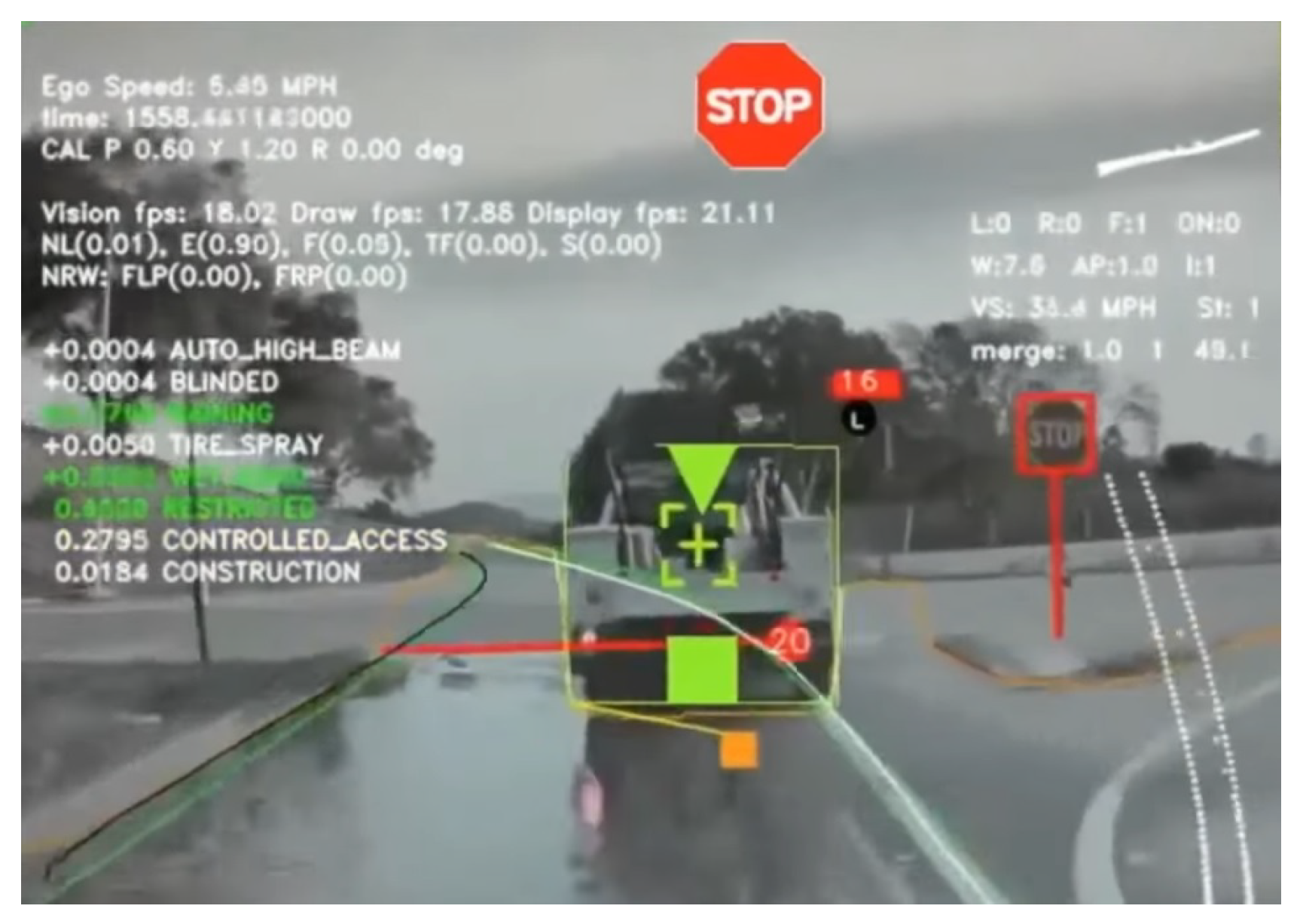

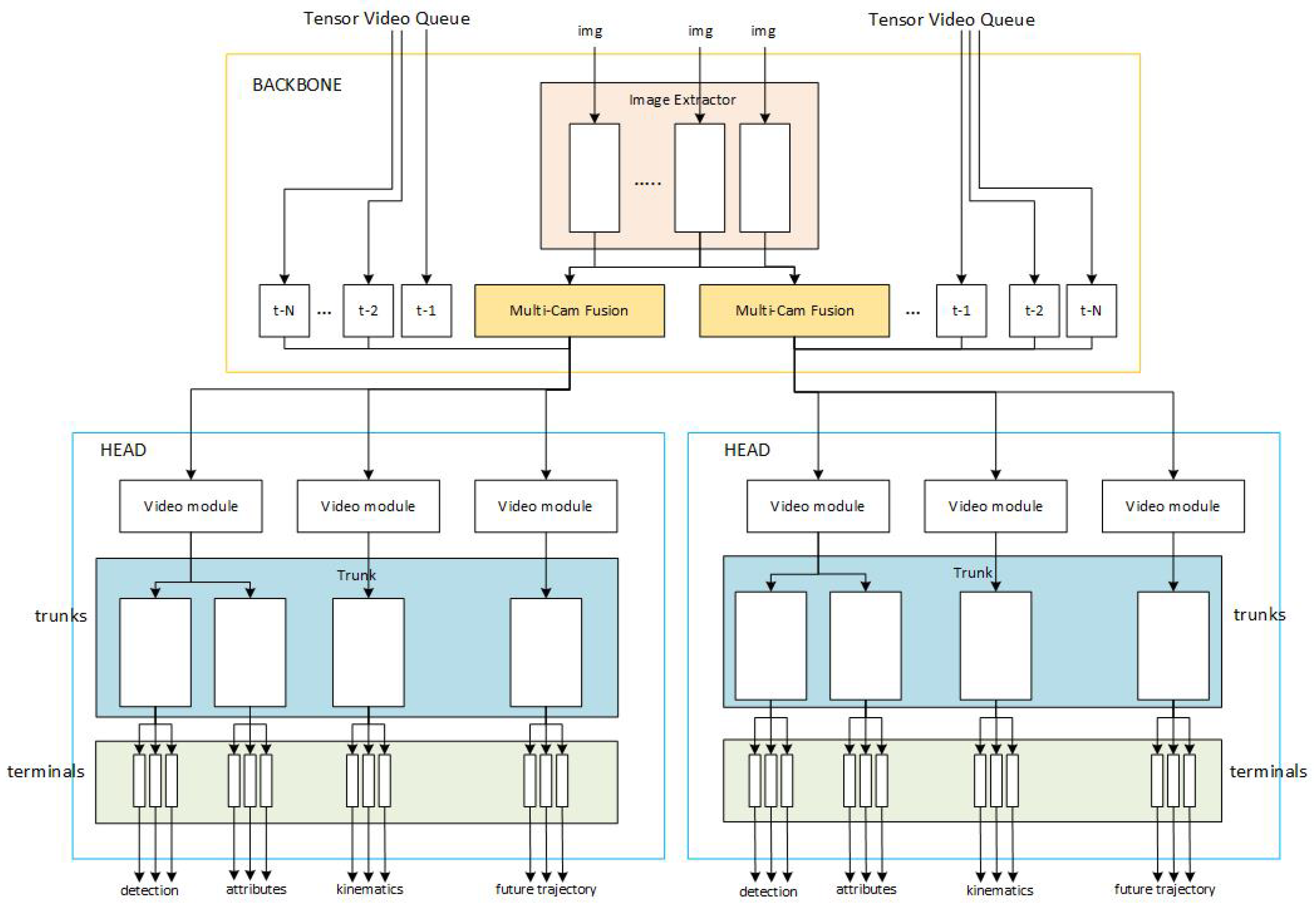

4.4. Computer Vision

5. Case Study: Waymo vs Tesla

6. Challenges

6.1. Current Challenges of Self-Driving Cars

6.1.1. Ethical Issues

6.1.2. Cybersecurity

6.1.3. Road Infrastructure and the Transition

6.1.4. Regulatory Needs

6.1.5. Hardware Requirements and Resource Allocation

6.1.6. Haywire Environment

6.2. User Acceptance and Public Opinion and How It Can Be Improved Further

References

- Yoganandhan, A.; Subhash, S.; Jothi, J.H.; Mohanavel, V. Fundamentals and development of self-driving cars. Materials today: proceedings 2020, 33, 3303–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Franz, M.; Abanteriba, S.; Mallavarapu, S. Autonomous driving cars: future prospects, obstacles, user acceptance and public opinion. International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics. Springer, 2018, pp. 318–328.

- Campbell, M.; Egerstedt, M.; How, J.; Murray, R. Autonomous driving in urban environments: approaches, lessons and challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2010, 368, 4649–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamson, H.; Merat, N.; Carsten, O.; Lai, F. Fully-automated driving: The road to future vehicles. Proceedings of the Sixth International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training and Vehicle Design. Citeseer, 2011, pp. 2–9.

- De, S.; Singh, K.; Seo, J.; Kapania, R.K.; Ostergaard, E.; Angelini, N.; Aguero, R. Structural Design and Optimization of Commercial Vehicles Chassis under Multiple Load Cases and Constraints. AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, 2019, p. 0705.

- Jrad, M.; De, S.; Kapania, R.K. Global-Local Aeroelastic Optimization of Internal Structure of Transport Aircraft Wing. 18th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference, 2017, p. 4321.

- Robinson, J.H.; Doyle, S.; Ogawa, G.; Baker, M.; De, S.; Jrad, M.; Kapania, R.K. Aeroelastic Optimization of Wing Structure Using Curvilinear Spars and Ribs (SpaRibs). 17th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference, 2016, p. 3994.

- De, S.; Singh, K.; Seo, J.; Kapania, R.K.; Ostergaard, E.; Angelini, N.; Aguero, R. Lightweight Chassis Design of Hybrid Trucks Considering Multiple Road Conditions and Constraints. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2021, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Jrad, M.; Locatelli, D.; Kapania, R.K.; Baker, M. SpaRibs geometry parameterization for wings with multiple sections using single design space. 58th AIAA/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, 2017, p. 0570.

- De, S.; Singh, K.; Seo, J.; Kapania, R.; Aguero, R.; Ostergaard, E.; Angelini, N. Unconventional Truck Chassis Design with Multi-Functional Cross Members. Technical report, SAE Technical Paper, 2019.

- De, S. Structural Modeling and Optimization of Aircraft Wings having Curvilinear Spars and Ribs (SpaRibs). PhD thesis, Virginia Tech, 2017.

- De, S.; Singh, K.; Alanbay, B.; Kapania, R.K.; Aguero, R. Structural Optimization of Truck Front-Frame Under Multiple Load Cases. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2018, Vol. 52187, p. V013T05A039.

- De, S.; Kapania, R.K. Algorithms For 2d Mesh Decomposition In Distributed Design Optimization. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2002.00525. [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan, B. Free Vibration analysis of Curvilinearly Stiffened Composite plates with an arbitrarily shaped cutout using Isogeometric Analysis. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2104.12856 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan, B.; Kapania, R.K. Thermal buckling of curvilinearly stiffened laminated composite plates with cutouts using isogeometric analysis. Composite Structures 2020, 238, 111881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, B.; Kapania, R.K. Analyzing thermal buckling in curvilinearly stiffened composite plates with arbitrary shaped cutouts using isogeometric level set method. Aerospace Science and Technology, 2022; 107350. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar, H.; Bankiti, V.; Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Liong, V.E.; Xu, Q.; Krishnan, A.; Pan, Y.; Baldan, G.; Beijbom, O. nuscenes: A multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 11621–11631.

- Wang, B.; Zhu, M.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, W.; Wei, H. Real-time 3D object detection from point cloud through foreground segmentation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 84886–84898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, H.; Han, H.; Ding, Y. MSeg3D: Multi-modal 3D Semantic Segmentation for Autonomous Driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 21694–21704.

- Ponnusamy, B. The role of artificial intelligence in future technology. International Journal of Innovative Research in Advanced Engineering 2018, 5, 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P.; Brooks, R.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Calo, R.; Etzioni, O.; Hager, G.; Hirschberg, J.; Kalyanakrishnan, S.; Kamar, E.; Kraus, S. ; others. Artificial intelligence and life in 2030: the one hundred year study on artificial intelligence 2016.

- Yurtsever, E.; Lambert, J.; Carballo, A.; Takeda, K. A Survey of Autonomous Driving: Common Practices and Emerging Technologies. CoRR, 2019; abs/1906.05113. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Q. Towards Fully Intelligent Transportation through Infrastructure-Vehicle Cooperative Autonomous Driving: Challenges and Opportunities. CoRR, 2021; abs/2103.02176. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Autonomous Driving with Deep Learning: A Survey of State-of-Art Technologies. CoRR, 2020; abs/2006.06091. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Khan, M.A.; El-Sayed, H. Collaborative autonomous driving—A survey of solution approaches and future challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Castillo, J.; Zeadally, S.; Guerrero-Ibánez, J. Autonomous cars: challenges and opportunities. IT Professional 2019, 21, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreyas, V.; Bharadwaj, S.N.; Srinidhi, S.; Ankith, K.; Rajendra, A. Self-driving cars: An overview of various autonomous driving systems. Advances in Data and Information Sciences, 2020; 361–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ondruš, J.; Kolla, E.; Vertal’, P.; Šarić, Ž. How do autonomous cars work? Transportation Research Procedia 2020, 44, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wolinski, D.; Lin, M.C. ADAPS: Autonomous driving via principled simulations. 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2019, pp. 7625–7631.

- Tan, C.; Sun, F.; Kong, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, C. A Survey on Deep Transfer Learning. ArXiv, 2018; abs/1808.01974. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. MICCAI, 2015.

- Rhinehart, N.; McAllister, R.; Levine, S. Deep imitative models for flexible inference, planning, and control. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1810.06544 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovs, M.; Ozols, K.; Dobrajs, A.; Kadikis, R. Improving Semantic Segmentation of Urban Scenes for Self-Driving Cars with Synthetic Images. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codevilla, F.; Müller, M.; López, A.; Koltun, V.; Dosovitskiy, A. End-to-end driving via conditional imitation learning. 2018 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 4693–4700.

- Bansal, M.; Krizhevsky, A.; Ogale, A. Chauffeurnet: Learning to drive by imitating the best and synthesizing the worst. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1812.03079 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.B.; Gupta, A.K.; He, K. Non-local Neural Networks. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018; 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.H.; Cai, J.; Liu, Z.N.; Mu, T.J.; Martin, R.R.; Hu, S. PCT: Point Cloud Transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2021, 7, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. ArXiv, 2010; abs/2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Yu, W.; Shi, Y.; Tay, F.E.H.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. Tokens-to-Token ViT: Training Vision Transformers from Scratch on ImageNet. ArXiv, 2101; abs/2101.11986. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid Vision Transformer: A Versatile Backbone for Dense Prediction without Convolutions. ArXiv, 2102; abs/2102.12122. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, B.; Codella, N.C.F.; Liu, M.; Dai, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. CvT: Introducing Convolutions to Vision Transformers. ArXiv, 2021; abs/2103.15808. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, A.; Savinov, N.; Geiger, A. Conditional affordance learning for driving in urban environments. Conference on Robot Learning. PMLR, 2018, pp. 237–252.

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Lu, C.; Luo, Z.; Xue, H.; Wang, C. Lidar-video driving dataset: Learning driving policies effectively. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 5870–5878.

- Wang, D.; Devin, C.; Cai, Q.Z.; Yu, F.; Darrell, T. Deep object-centric policies for autonomous driving. 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2019, pp. 8853–8859.

- Hecker, S.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. End-to-end learning of driving models with surround-view cameras and route planners. Proceedings of the european conference on computer vision (eccv), 2018, pp. 435–453.

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Cai, J.; Luo, J. End-to-end multi-modal multi-task vehicle control for self-driving cars with visual perceptions. 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). IEEE, 2018, pp. 2289–2294.

- Kwon, S.; Park, J.; Jung, H.; Jung, J.; Choi, M.K.; Tayibnapis, I.R.; Lee, J.H.; Won, W.J.; Youn, S.H.; Kim, K.H. ; others. Framework for Evaluating Vision-based Autonomous Steering Control Model. 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1310–1316.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Ros, G.; Codevilla, F.; Lopez, A.; Koltun, V. CARLA: An Open Urban Driving Simulator. Proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on Robot Learning, 2017, pp. 1–16.

- Liang, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Xing, E. Cirl: Controllable imitative reinforcement learning for vision-based self-driving. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 584–599.

- Bi, J.; Xiao, T.; Sun, Q.; Xu, C. Navigation by imitation in a pedestrian-rich environment. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1811.00506. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Zhou, B.; Koltun, V.; Krähenbühl, P. Learning by Cheating. ArXiv, 2019; abs/1912.12294. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. ArXiv, 2017; abs/1704.04861. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018; 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.E.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. ECCV, 2016.

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, H.; Deng, J. CornerNet: Detecting Objects as Paired Keypoints. ArXiv, 2018; abs/1808.01244. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, B.; Arbeláez, P.; Girshick, R.B.; Malik, J. Hypercolumns for object segmentation and fine-grained localization. 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015; 447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S.J. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017; 936–944. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020; 10778–10787. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. NAS-FPN: Learning Scalable Feature Pyramid Architecture for Object Detection. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019; 7029–7038. [Google Scholar]

- Devries, T.; Taylor, G.W. Improved Regularization of Convolutional Neural Networks with Cutout. ArXiv, 2017; abs/1708.04552. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.K.; Yu, H.; Sarmasi, A.; Pradeep, G.; Lee, Y.J. Hide-and-Seek: A Data Augmentation Technique for Weakly-Supervised Localization and Beyond. ArXiv, 2018; abs/1811.02545. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Jia, J. GridMask Data Augmentation. ArXiv, 2020; abs/2001.04086. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.E.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, L.; Zeiler, M.D.; Zhang, S.; LeCun, Y.; Fergus, R. Regularization of Neural Networks using DropConnect. ICML, 2013.

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Le, Q.V. DropBlock: A regularization method for convolutional networks. NeurIPS, 2018.

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Huang, T.S. UnitBox: An Advanced Object Detection Network. Proceedings of the 24th ACM international conference on Multimedia 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rezatofighi, S.H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection Over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019; 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. ArXiv, 2020; abs/1911.08287. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 42, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. ECCV, 2018.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. Receptive Field Block Net for Accurate and Fast Object Detection. ArXiv, 2018; abs/1711.07767. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Sheng, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cai, L.; Ling, H. M2Det: A Single-Shot Object Detector based on Multi-Level Feature Pyramid Network. AAAI, 2019.

- Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. Learning Spatial Fusion for Single-Shot Object Detection. ArXiv, 2019; abs/1911.09516. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020; 10778–10787. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Liew, J.H.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. PANet: Few-Shot Image Semantic Segmentation with Prototype Alignment. 2020; arXiv:cs.CV/1908.06391. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. ArXiv, 2020; abs/2004.10934. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, D. Mish: A Self Regularized Non-Monotonic Activation Function. BMVC, 2020.

- Elsken, T.; Metzen, J.H.; Hutter, F. Neural Architecture Search: A Survey. ArXiv, 2019; abs/1808.05377. [Google Scholar]

- Vanschoren, J. Meta-Learning: A Survey. ArXiv, 2018; abs/1810.03548. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Kwok, J.; Ni, L. Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning. arXiv: Learning, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, V.; Yu, H.; Miao, C. A Survey of Zero-Shot Learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, J.H.; Jeon, M.; Lee, B.G. Unsupervised learning for depth, ego-motion, and optical flow estimation using coupled consistency conditions. Sensors 2019, 19, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmuller, H. Accurate and efficient stereo processing by semi-global matching and mutual information. 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05). IEEE, 2005, Vol. 2, pp. 807–814.

- Espinosa Morales, A.M.; Moure Lopez, J.C. Embedded Real-time stereo estimation via semi-global matching on the GPU. Procedia Computer Science, 2016, vol. 80, p. 143-153.

- Newcombe, R.A.; Lovegrove, S.J.; Davison, A.J. DTAM: Dense tracking and mapping in real-time. 2011 international conference on computer vision. IEEE, 2011, pp. 2320–2327.

- Wang, S.; Clark, R.; Wen, H.; Trigoni, N. Deepvo: Towards end-to-end visual odometry with deep recurrent convolutional neural networks. 2017 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2017, pp. 2043–2050.

- Wang, P.; Shen, X.; Lin, Z.; Cohen, S.; Price, B.; Yuille, A.L. Towards unified depth and semantic prediction from a single image. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 2800–2809.

- Vijayanarasimhan, S.; Ricco, S.; Schmid, C.; Sukthankar, R.; Fragkiadaki, K. Sfm-net: Learning of structure and motion from video. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1704.07804 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.F. Unsupervised learning of accurate camera pose and depth from video sequences with Kalman filter. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 32796–32804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogiannis, A.; Chandra, R.; Manocha, D. B-gap: Behavior-guided action prediction for autonomous navigation. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2011.03748. [Google Scholar]

- Tesla, D. miles of full self driving, tesla challenge 2, autopilot,”, 25.

- Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Tomizuka, M.; Zhan, W. Socially-compatible behavior design of autonomous vehicles with verification on real human data. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2021, 6, 3421–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, S.K.; Tilbury, D.M.; Yang, X.J.; Pradhan, A.K.; Robert, L.P. Analysis and prediction of pedestrian crosswalk behavior during automated vehicle interactions. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 6426–6432.

- Saleh, K.; Abobakr, A.; Nahavandi, D.; Iskander, J.; Attia, M.; Hossny, M.; Nahavandi, S. Cyclist intent prediction using 3d lidar sensors for fully automated vehicles. 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 2020–2026.

- O’Mahony, N.; Campbell, S.; Carvalho, A.; Krpalkova, L.; Hernandez, G.V.; Harapanahalli, S.; Riordan, D.; Walsh, J. One-shot learning for custom identification tasks; a review. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 38, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, S.M. Generative One-Shot Learning (GOL): A semi-parametric approach to one-shot learning in autonomous vision. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 7127–7134.

- Haddad, M.; Sanders, D.; Langner, M.C.; Tewkesbury, G. One shot learning approach to identify drivers. IntelliSys 2021. Springer, 2021, pp. 622–629.

- Ullah, A.; Muhammad, K.; Haydarov, K.; Haq, I.U.; Lee, M.; Baik, S.W. One-shot learning for surveillance anomaly recognition using siamese 3d cnn. 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–8.

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Kwok, J.; Ni, L. Generalizing from a few examples: A survey on few-shot learning. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1904.05046. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Tang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Su, H. Visual driving assistance system based on few-shot learning. Multimedia Systems, 2021; 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Majee, A.; Agrawal, K.; Subramanian, A. Few-shot learning for road object detection. AAAI Workshop on Meta-Learning and MetaDL Challenge. PMLR, 2021, pp. 115–126.

- Stewart, K.; Orchard, G.; Shrestha, S.B.; Neftci, E. Online few-shot gesture learning on a neuromorphic processor. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems 2020, 10, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Kaul, M. Self-supervised few-shot learning on point clouds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 7212–7221. [Google Scholar]

- Ranga, A.; Giruzzi, F.; Bhanushali, J.; Wirbel, E.; Pé rez, P.; Vu, T.H.; Perotton, X. VRUNet: Multi-Task Learning Model for Intent Prediction of Vulnerable Road Users. Electronic Imaging 2020, 32, 109-1–109-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; O’Mahony, N.; Krpalcova, L.; Riordan, D.; Walsh, J.; Murphy, A.; Ryan, C. Sensor technology in autonomous vehicles: A review. 2018 29th Irish Signals and Systems Conference (ISSC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–4.

- Janai, J.; Güney, F.; Behl, A.; Geiger, A.; others. Computer vision for autonomous vehicles: Problems, datasets and state of the art. Foundations and Trends® in Computer Graphics and Vision 2020, 12, 1–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Engineering autonomous vehicles and robots: the DragonFly modular-based approach; John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Bagloee, S.A.; Tavana, M.; Asadi, M.; Oliver, T. Autonomous vehicles: challenges, opportunities, and future implications for transportation policies. Journal of modern transportation 2016, 24, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, J.D.; King, A.G. Autonomous driving-a practical roadmap. Technical report, SAE Technical Paper, 2010.

- Bazilinskyy, P.; Kyriakidis, M.; de Winter, J. An international crowdsourcing study into people’s statements on fully automated driving. Procedia Manufacturing 2015, 3, 2534–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; de Winter, J.C. Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour 2015, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).