1. Introduction

The RH [

1] is one of the most important unsolved problems in mathematics. Although there are many achievements towards proving this celebrated hypothesis, it remains an open problem [

2,

3]. The Riemann zeta function is originally defined in the half-plane

by the absolutely convergent series [

2]

The connection between the above-defined Riemann zeta function and prime numbers was discovered by Euler, i.e., the famous Euler product

where

p runs over the prime numbers.

Riemann showed in his paper in 1859 how to extend the zeta function to the whole complex plane

by analytic continuation, i.e.

where

is the symbol adopted by Riemann to represent the contour integral from

to

around a domain which includes the value 0 but no other point of discontinuity of the integrand in its interior.

Or equivalently,

where

is the Jaccobi theta function,

is the Gamma function in the following Weierstrass expression

where

is the Euler-Mascheroni constant.

As shown by Riemann,

extends to

as a meromorphic function with only a simple pole at

, with residue 1, and satisfies the following functional equation

The Riemann zeta function

has zeros at the negative even integers:

,

,

,

, ⋯ and one refers to them as the

trivial zeros. The other zeros of

are the complex numbers, i.e.,

non-trivial zeros [

2].

In 1896, Hadamard [

4] and Poussin [

5] independently proved that no zeros could lie on the line

, together with the functional equation

and the fact that there are no zeros with real part greater than 1, this showed that all non-trivial zeros must lie in the interior of the

critical strip. Later on, Hardy (1914) [

6], Hardy and Littlewood (1921) [

7] showed that there are infinitely many zeros on the

critical line .

To give a summary of the related research works on the RH, we have the following results on the properties of the non-trivial zeros of

[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

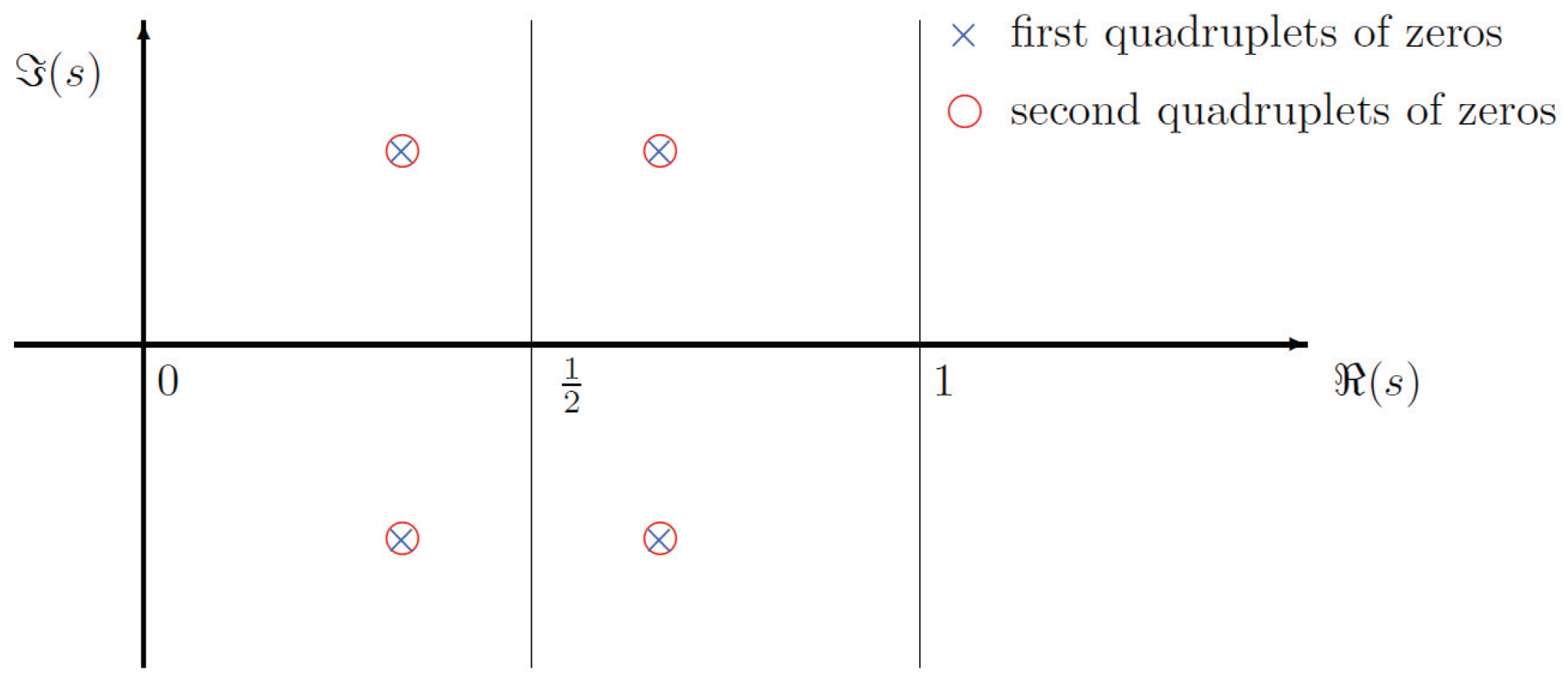

Lemma 1. Non-trivial zeroes of , noted as , have the following properties

1) The number of non-trivial zeroes is infinity;

2) ;

3) ;

4) are all non-trivial zeroes.

As further study, a completed zeta function

is proposed by equation

It is well-known that

is an entire function of order 1. This implies

is analytic, and can be expressed as infinite product of polynomial factors, in the whole complex plane

. In addition, replacing

s with

in Equation (

6), and combining Equation (

5), we obtain the following functional equation

According to the definition of

, and recalling Equation (

4), the trivial zeros of

are canceled by the poles of

. The zero of

and the pole of

cancel; the zero

and the pole of

cancel [

9,

10,

11]. Thus, all zeros of

are exactly the nontrivial zeros of

. Then we have the following Lemma 2.

Lemma 2. The zeros of coincide with the non-trivial zeros of .

Consequently, the following two statements are equivalent.

Statement 1.

All the non-trivial zeros ofhave real part equal to.

Statement 2.

All zeros ofhave real part equal to.

To prove the RH, a natural thinking is to estimate the numbers of non-trivial zeros of

inside or outside some certain areas according to Argument Principle. Along this train of thought, there are many research works. Let

denote the number of non-trivial zeros of

inside the rectangle:

, and let

denote the number of non-trivial zeros of

on the line

. Selberg proved that there exist positive constants

c and

, such that

[

12], later on, Levinson proved that

[

13], Lou and Yao proved that

[

14], Conrey proved that

[

15], Bui, Conrey and Young proved that

[

16], Feng proved that

[

17], Wu proved that

[

18].

On the other hand, many non-trivial zeros have been calculated by hand or by computer programs. Among others, Riemann found the first three non-trivial zeros [

19]. Gram found the first 15 zeros based on Euler-Maclaurin summation [

20]. Titchmarsh calculated the 138

th to 195

th zeros using the Riemann-Siegel formula [

21,

22]. Here are the first three (pairs of) non-trivial zeros:

.

The idea of this paper is originated from Euler’s work on proving the following famous equality

This interesting result is deduced by comparing the like terms of two types of infinite expressions, i.e., infinite polynomial and infinite product, as shown in the following

Then the author of this paper conjectured that

should be factored into

or something like that, which was verified by paring

and

in the Hadamard product of

, i.e.

The Hadamard product of

as shown in Equation (

10) was first proposed by Riemann, however, it was Hadamard who showed the validity of this infinite product expansion [

23].

where

,

runs over all zeros of

.

Hadamard pointed out that to ensure the absolute convergence of the infinite product expansion,

and

are paired. Later in

Section 4, we will show that

and

can also be paired to ensure the absolute convergence of the infinite product expansion.

2. Preliminary Lemmas

This section provides some preliminary knowledge to support the proof of the key lemma - Lemma 10 in next section. We need the classical results (Lemma 3 and Lemma 4) in polynomial algebra over fields, with extension to infinite product of polynomial factors as a type of entire function (Lemma 5, Lemma 6, and Lemma 7), and properties of the multiplicity of zeros of entire function (Lemma 8 and Lemma 9).

To begin with, we introduce the ring of polynomial, denoted as

, which is defined as the set of all polynomials in

x over the field of real numbers

, i.e.

The set equipped with the operations + (addition) and · (multiplication) is the ring of polynomial in x over the field .

The ring of polynomial is a subset of the ring of entire function, and both rings possess properties of divisibility, coprimality, and greatest common divisor, denoted as "gcd". There are also differences between these two rings. Among others, polynomials have degrees, entire functions in infinite product form do not. For entire functions, their divisibility, coprimality and common factors are determined by the relationships between their zero sets [

24,

25,

26].

Although references [

24,

25,

26] provide definitions for divisibility, coprimality, and greatest common divisor of entire functions, we present the corresponding definitions below to emphasize the specific case considered in this paper: the relationship between a polynomial and an entire function represented as an infinite product of polynomial factors.

Definition 1. Let , be an entire function, and . We say divides , denoted as , if there exists an entire function , such that .

Definition 2. Let , be an entire function, and , a polynomial is called the greatest common divisor of and if: 1. and ; 2. For every polynomial that divides both and , we have .

Definition 3. Let , be an entire function, and . We say that and are coprime (relatively prime) if whenever a polynomial divides both and , then must be a nonzero constant. This is denoted by .

To support the proof of the key lemma - Lemma 10 in next section. We need the following lemmas.

Lemma 3. Let . If is irreducible (prime) and divides the product , then divides one of the polynomials .

Lemma 4. Let . If is irreducible and is any polynomial, then either divides or .

Lemma 5. Let . If is irreducible and divides the infinite product , then divides one of the polynomials .

Lemma 6. Let . If is irreducible and divides the product , but and are relatively prime (coprime), then divides .

Lemma 7. Let . If is irreducible, then either divides , or and are relatively prime, i.e., .

Remark 1. The contents of Lemma 3 and Lemma 4 can be found in many textbooks of linear algebra, modern algebra, or abstract algebra, see for example references [27,28,29]. Below we give the proofs of Lemma 5, Lemma 6, and Lemma 7.

Proof (Proof of Lemma 5). The proof is conducted by Transfinite Induction.

Let ( is an ordinal number) be the statement:

". If is irreducible and divides the product , then divides one of the polynomials ", where , with the ordering that for all natural numbers n, is the smallest limit ordinal other than 0.

Base Case: is an obvious fact according to Lemma 3 with ;

Successor Case: To prove , we have , where . Then according to Lemma 3 with , we have or . Considering : if divides , then divides one of , thus we know .

Limit Case: We need to prove

,

is any limit ordinal other than 0. For the sake of contradiction, assume that

, i.e.,

does not divide any polynomial

. Then, considering

is irreducible with the property stated in Lemma 4, we have:

which contradicts

divides one of the polynomials

. Thus, we know that the assumption

is false.

Then is true, i.e., the Limit Case is true.

That completes the proof of Lemma 5. □

Proof (Proof of Lemma 6). If is irreducible and divides the product , then according to Lemma 5, divides one of the polynomials . Further, if and are relatively prime, then does not divides any factor of (otherwise divides , which contradicts the condition " and are relatively prime"). Thus, must divides .

That completes the proof of Lemma 6. □

Proof (Proof of Lemma 7). Since is irreducible, then by the definition of irreducible polynomial, either or . It is clear that . Thus, we conclude that either divides or , i.e., and are relatively prime.

That completes the proof of Lemma 7. □

Additionally, we also need the following results on properties of a zero of entire function in complex analysis for understanding the multiplicity of a zero of .

Lemma 8. Let be a non-zero entire function, and let be a zero of . Then the multiplicity of is a finite positive integer.

Proof. Let , be an entire function, which means it is holomorphic on the whole complex plane. Suppose has a zero at of multiplicity m, then , where is also an entire function and .

Assume for contradiction that m is infinite, which implies there exists an accumulation point of zeros in the neighbor of . Then, by Identity Theorem for holomorphic functions, and considering "0" is also an entire function, we have , which contradicts the given condition that . Thus, the assumption is false, i.e., m must be a finite positive integer.

That completes the proof of Lemma 8. □

Remark 2. Statements similar to Lemma 8 can be found in Reference [30] and other related textbooks/monographs.

Lemma 9. Let be a non-zero entire function, and let be a zero of . Then the multiplicity of is unique.

Proof. Let , be an entire function, which has a multiple zero at of multiplicity m. We can write: , where is also an entire function and .

Assume for contradiction that there exists another integer such that n is also a multiplicity of the zero . This means we can also write: , where is an entire function and .

Since both expressions for must be equal, we then obtain . Without loss of generality, consider , then we have: , which is a contradiction to . Thus, the assumption is false, i.e., the multiplicity of a zero of any non-zero entire function is unique.

That completes the proof of Lemma 9. □