Graphic Abstract

This image suggests that the synergy of three key mechanisms dictates chemical, biological, and social evolution. These key mechanisms include natural selection and two other enigmatic mechanisms revealed by this article.

Why did simple carbon-based materials (CBMs) on Earth evolve into complex, orderly, and diverse organisms and societies? Extensive research in physics, chemistry, and biology has yet to explicitly and comprehensively answer this fundamental scientific question [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. For instance, physics' answers are often elusive because they often rely on certain nebulous and abstract concepts associated with entropy, such as negative entropy, the theory of dissipative structures, and the maximum entropy hypothesis [

2,

3,

4]. Chemistry's answers focus on the concept of chemical evolution [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], which cannot address biological evolution and social evolution. Biology's answers have moved from Darwin's theory of natural selection to its updated version, the Modern Synthesis. The Modern Synthesis highlights the importance of natural selection and refines its definition from Darwin's “survival of the fittest” to the gradual changes in gene frequencies within populations, as individuals carrying adaptive mutations tend to achieve higher reproductive success. [

14]. While these two biological theories can adeptly explain many evolutionary phenomena, they fall short in addressing macroevolutionary issues, such as the origin of life, and social evolution, which emphasizes both competition and inclusiveness, both selfishness and altruism, and both conflicts and collaboration [

15]. Here, we propose the Carbon-Based Evolutionary Theory (CBET), aiming to provide the first explicit, evidence-based, and holistic explanation for the entire evolution of CBMs on Earth.

1. Methods and Definitions

CBET is established through the novel, systematic integration of numerous factors critical to CBM evolution using logic reasoning, diverse established knowledge from physics, chemistry, biology, and the social sciences, along with the following definitions.

Driving force: the energy-associated power that makes a specific change.

Mechanism: the reason for the change of things.

Carbon-containing molecules (CCMs): those molecules containing carbon atoms.

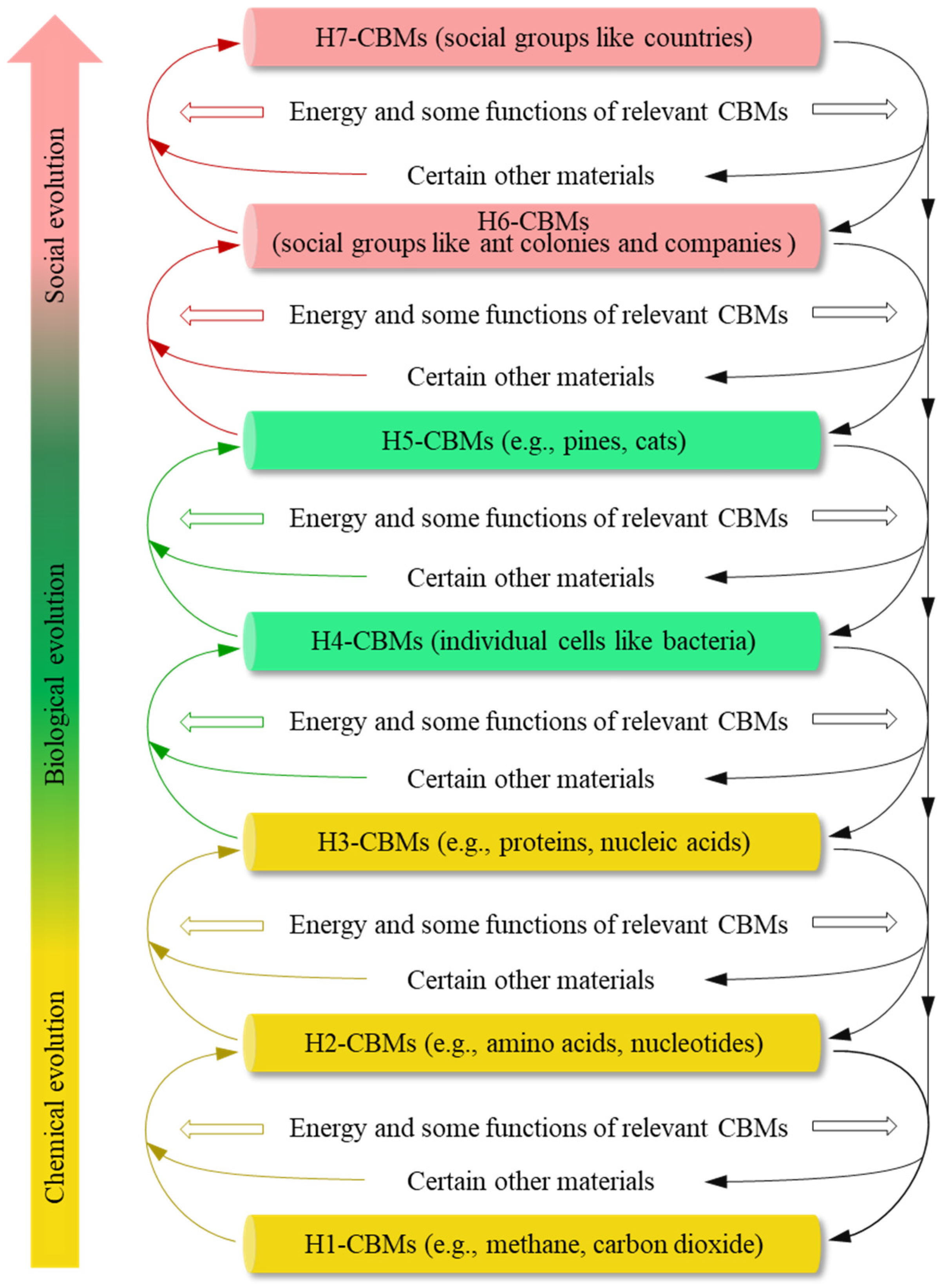

CBMs: those substances in which carbon atoms play a major role at the atomic level. CBMs are classified into the following eight hierarchies.

H0-CBMs: carbon atoms.

H1-CBMs: small CCMs, such as CH4, CO2, and HCN.

H2-CBMs: middle CCMs, such as lysine, gentamicin, and glucose.

H3-CBMs: large CCMs, such as proteins and nucleic acids.

H4-CBMs: individual cells, such as bacteria and cells in rats, composed of numerous H3-CBMs and other molecules with internal collaboration.

H5-CBMs: multicellular organisms, such as pines and rabbits.

H6-CBMs: social groups with only one hierarchy in management, such as ant colonies, bee colonies, and many small companies, which are composed of some animal or human individuals that closely cooperate for the social groups with different duties for the social groups.

H7-CBMs: human social groups that have multiple hierarchies in management, and low-hierarchy social groups closely cooperate with different duties for high-hierarchy social groups. Universities, armies, and countries are examples of H7-CBMs.

The collaborative social groups of H6-CBMs and H7-CBMs can be viewed as superorganisms [

16], while multicellular organisms and unicellular can be viewed as social groups of cells and molecules, respectively. These facts support the above definitions of the above eight hierarchies of CBMs. Notably, no clear lines separate the above CBM hierarchies. For instance, some peptides are between H2-CBMs and H3-CBMs, some MMAs are between H3-CBMs and H4-CBMs, and lion groups are between H5-CBMs and H6-CBMs.

High-hierarchy CBMs (HHCBMs) and low-hierarchy CBMs (LHCBMs) are defined by comparing their hierarchies. For instance, H4-CBMs are HHCBMs compared to H3-CBMs, but they are LHCBMs compared to H5-CBMs.

Simple CBMs and complex CBMs are defined by comparing their structural complexity. For instance, eukaryotic paramecia are complex CBMs compared to prokaryotic staphylococci, but they are simple CBMs compared with multi-cellular ants.

Multi-molecule aggregates (MMAs): phospholipid bilayers, virions, ribosomes, and other relatively stable structures composed of multiple H3-CBMs with or without other molecules.

Chemical evolution: the evolution from small CCMs to middle and large CCMs, or from H1-CBMs to H2-CBMs and H3-CBMs.

Biological evolution: the origin and evolution of life, namely H4-CBMs and H5-CBMs.

Social evolution: the origin and evolution of animal or human social groups, namely H6-CBMs and H7-CBMs.

The overall performance of the formation and maintenance (OPFM) of a CBM: the holistic ability for the CBM to be formed and maintained.

Autocatalysis or allocatalysis: the catalysis of a molecule catalyzing the synthesis or degradation of itself (autocatalysis) or other molecules (allocatalysis).

2. Results

2.1. The Driving Force Mechanism

2.1.1. Origin of the Driving Force Mechanism

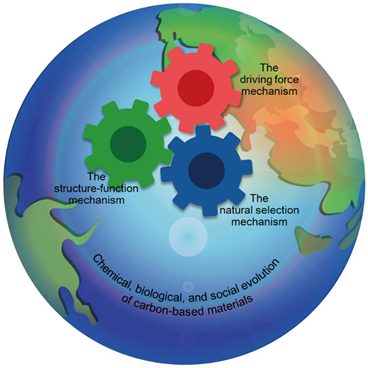

In a car, it is the functions of the automotive engine and the powertrain system that transform the energy from fuel into the driving force required for the car to operate. Similarly, as described in

Section 2.1.2 and illustrated in

Figure 1, some functions of the relevant CBMs transform certain energies on Earth into the driving force behind CBM evolution. At any given time, this driving force represents the energy-related power that both forms and degrades complex CBMs.

2.1.2. Effects of the Driving Force Mechanism

(1) Formation of H2-CBMs. Earth possesses abundant heat sources, including sunlight, lightning, geothermal energy, volcanic activity, fires, and the decomposition of organic matter [

17]. The heat energy released from these sources is adjusted by the extensive water, which amounts to approximately 1.35×10

18 tons, as well as the atmosphere, which is over 1,000 km thick, on Earth [

17]. The adjustment helps to maintain a moderate, widespread, and persistent distribution of heat energy on Earth and renders Earth a rare habitable planet [

20]. Under the second law of thermodynamics [

21], many H1-CBMs, such as CH

4, CO

2, and HCN, and other substances (e.g., H

2O) spontaneously absorb heat from these heat sources. Chemically, some functions of H1-CBMs transform the absorbed heat energy into the driving force to transform many H1-CBMs into diverse distinct H2-CBMs through heat-absorbing organic synthesis reactions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The prebiotic chemical synthesis of various H2-CBMs, such as amino acids, nucleotides, and monosaccharaides, has been experimentally validated [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], and supported by the fact that myriad distinct H2-CBMs have been identified from meteorites [

22]. Some functions of H1-CBMs, such as the reactivity of CO

2 with H

2O and the reactivity of CH

4 with NH

3, are critical for the formation of H2-CBMs.

(2) Formation of H3-CBMs. Many H2-CBMs generated through the above processes can further spontaneously absorb heat under the second law of thermodynamics from abundant heat sources on Earth. Chemically, some functions of H2-CBMs, such as the dehydration condensation reactions between some function groups of some H2-CBMs, transform the absorbed heat energy into the driving force to transform many H2-CBMs into myriad distinct H3-CBMs through heat-absorbing organic chemical reactions. High pressure, some inorganic molecules like boric acids, and certain H2-CBMs, such as N-phosphoryl amino acids, can facilitate the abiotic synthesis of some H3-CBMs [

5,

6,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

18].

Among all atoms, only carbon atoms can serve as the backbone to bond with other atoms, such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, halogens, metals, and various functional groups, to form long, complex, and water-soluble large molecules [

18], which are essential for the construction of organisms. Consequently, only CBMs have the potential to naturally evolve from simple structures into life [

18].

(3) Formation of H4-CBMs. Myriad H3-CBMs, such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, generated through the above processes, along with other materials (e.g., H

2O, H1-CBMs, and H2-CBMs), can form diverse MMAs. In physics and chemistry, some functions of H3-CBMs, such as the interaction among proteins through hydrogen bonds, transform the energy provided by the wind, rain, lightning, and solar evaporation into the driving force for the formation of myriad MMAs [

5,

9,

10,

11,

12]. A very few MMAs that emerged occasionally can actively absorb water, organic molecules, and energy to construct or reproduce themselves. The emergence of these MMAs represented the origin of life or the first batch of H4-CBMs. The energy, which is supplied under the laws of physics and chemistry, is critical to the formation and maintenance of H4-CBMs, which involve energy-absorbing synthesis of diverse H3-CBMs. Meanwhile, some functions of certain H3-CBMs, such as the one of nucleic acids in storing genetic information and the catalysis activity of many proteins, are also critical for the formation of H4-CBMs. Consequently, some functions of diverse H3-CBMs transform certain energy into the driving force of the formation of H4-CBMs, which, for example, is embodied in the exponential growth of

Escherichia coli cultured in broth within a warm incubator. The first generations of H4-CBMs might originate at sea beds near hydrothermal vents [

23]. One of these H4-CBMs survived natural selection and became the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of all living things. LUCA could possess hundreds of genes [

24]. The experiments on the abiotic synthesis of viruses and H4-CBMs have been successful, which supports the abiogenesis of LUCA from extremely vast MMAs [

25,

26], although the precise steps by which LUCA originated, particularly the ones involving the origin of codons for protein synthesis [

27], remains unknown.

(4) Formation of H5-CBMs. Myriad variants of prokaryotic H4-CBMs could accumulate on Earth in billions of years after its origin. Some variants became eukaryotic H4-CBMs during the early Proterozoic eon [

14,

28]. Myriad variants of eukaryotic H4-CBMs could accumulate on Earth in the following hundreds of million years. Some variants of H4-CBMs became eukaryotic multicellular organisms (H5-CBMs) during the middle Proterozoic eon [

14,

29]. Some functions of the relevant H4-CBMs, such as the abilities of the fertilized eggs of elephants or trees to absorb energy and materials, gene regulation, and cell differentiation, transform certain energy on Earth into the driving force for the formation and maintenance of H5-CBMs, driving fertilized eggs and related materials to develop into adult elephants and other H5-CBMs. The driving force is embodied in the spring and summer, when many plants sprout and grow vigorously. It is also embodied in tropical rainforests, which are rich in diverse H5-CBMs. By contrast, glacial periods with inadequate energy on Earth can lead to mass extinction of H5-CBMs [

14].

(5) Formation of H6-CBMs. Multicellular animals possibly emerged on Earth 800 million years ago [

30]. Possibly 100 million years ago, some insects established their social groups (H6-CBMs) [

31]. Sociality is widespread in

Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and wasps),

Blattodea (termites), and

Hemiptera (aphids) [

16,

32,

33]. A typical animal social collective has a queen and a few reproductive males, who take on the roles of the sole reproducers, and other individuals act as soldiers and workers who collaborate to create a living situation favorable for the brood. Some small companies can also be taken as H6-CBMs. Some functions of the relevant animals, such as their complexity in gene regulation, chemical communications, and collaboration behaviors, are critical for establishing social groups [

31,

32,

33,

34]. These functions transform certain energy on Earth, such as the chemical energy stored in honey collected by honeybees, into the driving force for the formation of the relevant H6-CBMs.

(6) Formation of H7-CBMs. H7-CBMs are human social groups that have multiple hierarchies in management. Some functions of some human social groups, such as their advanced technologies, their advanced management systems, and/or their strong willing to expand their group sizes, transform certain energy on Earth associated with food, hydropower, animal power, human power, coal, electricity, nuclear energy, and/or solar energy into the driving force for the formation of H7-CBMs.

(7) Degradation of complex CBMs. Due to some functions or features of CBMs, such as a deficiency in certain functions and the relative fragility of carbon-carbon bonds, energy from fires, collisions, radiation, and other sources can degrade numerous complex CBMs. [

14,

15,

18]. Sometimes the energy of asteroid collision and volcanism can directly or indirectly lead to mass extinctions of complex CBMs [

14]. The degradation process usually releases energy (

Figure 1). While complex CBMs can be established only hierarchy by hierarchy, they can be directly degraded into CBMs one or more hierarchies lower (

Figure 1). For instance, a living grass can be directly decomposed into molecules and atoms in a steelmaking furnace.

2.1.3. Repeated Cycles of the Formation and Degradation of Complex CBMs

The above processes lead to repeated cycles of the formation and degradation of complex CBMs. The repeated cycles align with the carbon cycling on Earth, which influences the carbon contents in the atmosphere, land, oceans, biosphere, and human society [

18,

37]. The CBMs in these repeated cycles hold the following two features.

(1) Variability. The regenerated complex CBMs frequently experience structural changes, and the changes hold myriad possibilities. Consequently, a diverse array of complex CBMs, spanning from H2-CBMs to H7-CBMs, has arisen naturally.

(2) Relative stability. For example, some proteins have been well preserved in fossils for millions of years [

35], and various H2-CBMs could have been preserved billions of years in meteorites [

36], and humans can typically live for decades.

The repeated cycles of the formation and degradation of H4-CBMs and H5-CBMs involve the formation and degradation of many H2-CBMs and H3-CBMs. Consequently, biological evolution is the natural extension of chemical evolution.

The repeated cycles of the formation and degradation of H6-CBMs and H7-CBMs involve the birth and death of cells and animal individuals within H6-CBMs or H7-CBMs. Consequently, social evolution is the natural extension of biological evolution.

2.2. The Structure-Function Mechanism

2.2.1. Origin of the Structure-Function Mechanism

Fact 1: The hierarchical escalation of the complexity of CBMs resulted from the driving force mechanism can yield novel functions that are not present in LHCBMs. This is in accordance with the fundamental principle of systems theory: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts [

38]. For example, while individual bird cells cannot fly, birds as a whole can. When a group of individuals coalesces into a basketball team, the team acquires new capabilities, such as competing in games to attract sponsorships, which in turn supports the team's sustenance.

Fact 2: Throughout the repeated cycles of formation and degradation of HHCBMs, certain HHCBMs may acquire new functions as a result of structural changes occurring during these cycles. For instance, genomic mutations can modify the running speeds of goats, the chemical communication within insect colonies, and the cognitive abilities of humans.

The two aforementioned facts are based on the logic that structural changes can give rise to new functions. They form the structure-function mechanism of CBM evolution, which creates new functions that can be beneficial, detrimental, or neutral to the formation and maintenance of CBMs ranging from H2-CBMs to H7-CBMs. Numerous functions of the relevant CBMs depicted in

Figure 1 are produced through this mechanism, as detailed below. Furthermore, certain genetic mutations of some organisms are not random because of the structure-function mechanism.

2.2.2. Effects of the Structure-Function Mechanism

Many H2-CBMs acquire novel functions through the structure-function mechanism. Some H2-CBMs, such as glucose and adenosine triphosphate, can store energy. Others can catalyze specific chemical reactions [

8,

9,

39,

40,

41], including the synthesis of various chiral compounds. Certain H2-CBMs possess two or more active functional groups and can therefore be polymerized. Numerous H2-CBMs (e.g., gentamicin and metformin) have the ability to treat human diseases that cannot be cured by H1-CBMs, thus benefiting the maintenance of human H5-CBMs. Additionally, certain structural changes in H2-CBMs can dramatically alter their functions, a principle frequently applied in drug optimization.

Many H3-CBMs also acquire new functions through the structure-function mechanism. For instance, some proteins function as ion channels. Many proteins can catalyze the synthesis of specific H2-CBMs or H3-CBMs. Nucleic acid H3-CBMs (DNA or RNA) can act as templates to direct the precise synthesis of DNA and RNA. Phospholipid H3-CBMs are amphiphilic and can self-assemble into a barrier-like bilayer. The H3-CBMs of numerous antibodies can prevent viral infections. These functions of H3-CBMs are not achievable by the H2-CBMs that constitute the respective H3-CBMs. Furthermore, certain structural changes in H3-CBMs (e.g., proteins) can significantly alter their functions, forming the genetic basis for certain human genetic diseases.

Many MMAs obtain novel functions through the structure-function mechanism. Some chlorophyll-like MMAs composed of certain proteins can transform CO2 to sugar. Some MMAs composed of certain proteins and DNA molecules can replicate the DNA molecules through the DNA polymerase activity of the proteins. Some MMAs composed of the bilayer of phospholipids can safeguard water-soluble H2-CBMs and H3-CBMs from degradation by enzymes. The above functions of MMAs could facilitate the formation and maintenance of H2-CBMs and H3-CBMs, which, in turn, facilitate the formation and maintenance of MMAs. A very few MMAs can actively absorb water, organic molecules, and energy to construct themselves. The emergence of these MMAs represents the origin of life or H4-CBMs, which possess the critical function of life: reproduction. Reproduction of H4-CBMs can efficiently facilitate the formation and maintenance of H2-CBMs, H3-CBMs, and MMAs within H4-CBMs. Meanwhile, certain structural changes (e.g., genomic changes) of H4-CBMs can significantly change the functions of the H4-CBMs.

Many H5-CBMs obtain novel functions through the structure-function mechanism. For instance, cat cells cannot catch rats, but cats can. Meanwhile, structural changes of H5-CBMs can significantly change the functions of the H5-CBMs. For instance, inflammatory changes leading to necrosis of heart, brain, and vascular cells kill many humans annually.

Many H6 -CBMs obtain novel functions through the structure-function mechanism. For instance, similar to the breeding of cows by humans for milk, European red ants (

Formica rufa) cultivate various species of aphids for collecting the honeydew of aphids, which cannot be realized by a single ant [

42]. Meanwhile, certain structural changes of H6-CBMs can significantly change the functions of H6-CBMs. For instance, changes of the rules of a company can significantly change the functions of the company.

Many H7-CBMs obtain novel functions through the structure-function mechanism. For instance, after merging into large agricultural entities, which are HHCBMs, many agricultural firms can reduce their overall operating costs, increase the production of agricultural goods (such as certain CBMs) through technological complementarity, and gain a larger market share via market complementarity. Meanwhile, certain structural changes of H7-CBMs (e.g., changes of the leaders of a country) can significantly change the functions of H7-CBMs.

2.3. The Natural Selection Mechanism

2.3.1. Origin of the Natural Selection Mechanism

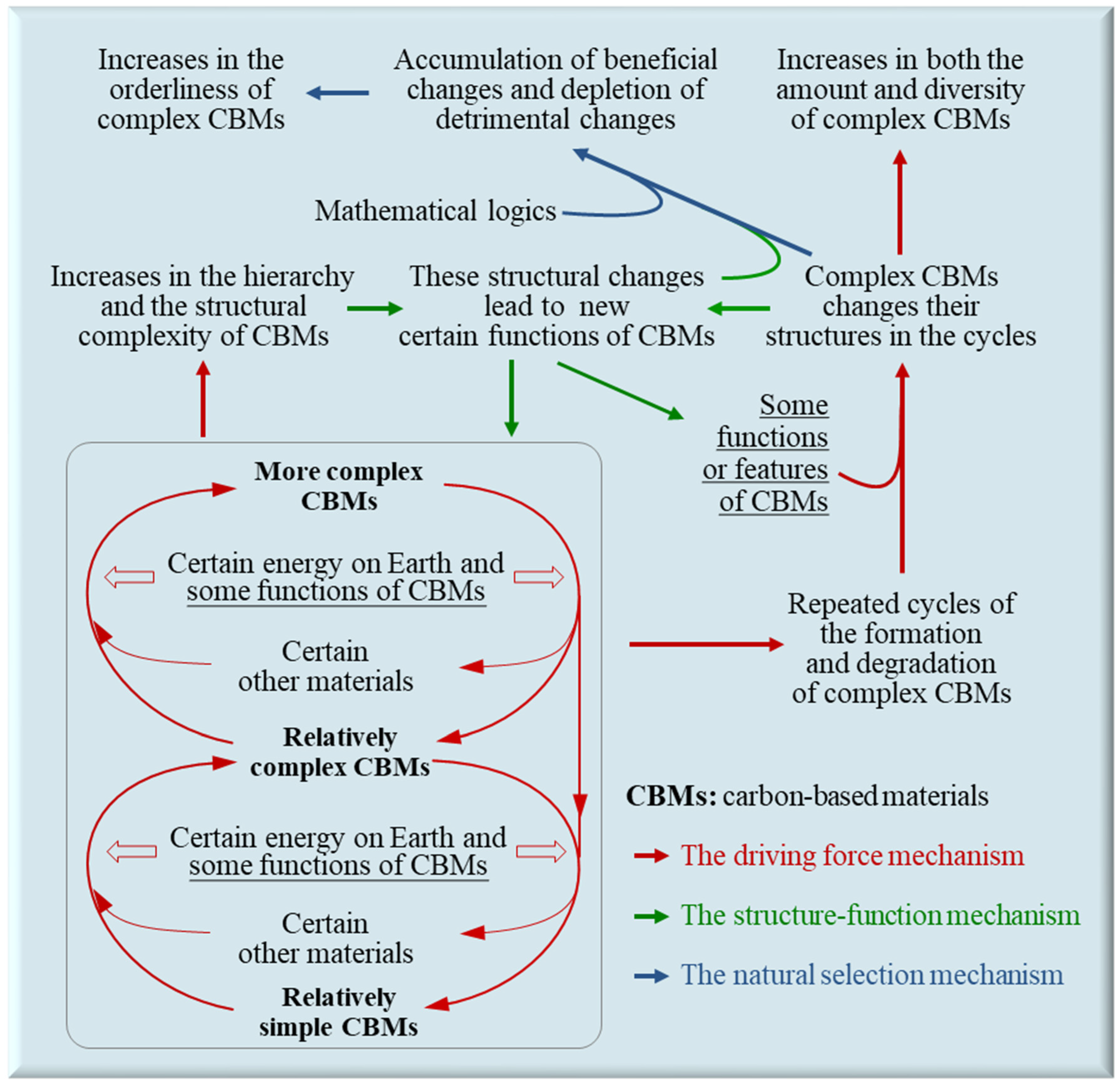

As elucidated in

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2, there are cycles of the formation and degradation of complex CBMs, and many complex CBMs undergo structural and functional changes during these cycles. These cycles hold the following three mathematical logics.

Logic 1: If the total formation of a complex CBM exceeds its total degradation, this complex CBM persists on Earth.

Logic 2: If the formation-to-degradation ratio of a complex CBM is >1 (or <1), its quantity is increasing (or decreasing) during the period.

Logic 3: If the formation-to-degradation ratio of complex CBM A is greater than that of complex CBM B, the ratio of CBM A versus CBM B in quantity is increasing.

These three mathematical logics constitute the natural selection mechanism of CBM evolution. In other words, natural selection stems from mathematical logic, which is the essence of its operation. Natural selection in previous theories stems from the survival competition of organisms [

14], which is a biological phenomenon governed by the mathematical logic.

2.3.2. Features or Effects of Natural Selection

(1) Natural selection is not only applicable to biological evolution but also to chemical and social evolution, as indicated by the above three logics.

(2) The OPFM of a complex CBM dictates its destiny in natural selection based on the above three mathematical logics. The OPFM is not determined by any single component, trait, or hierarchy of the complex CBM alone, but rather by the collective contribution of all components, traits, and hierarchies. This implies that every component, trait, and hierarchy of a complex CBM is subject to natural selection. Furthermore, certain traits of complex CBMs, such as the sprinting ability of antelopes, the cooperative behavior of wolves, or human individual skills, can markedly boost a CBM's OPFM. Consequently, natural selection emphasizes both comprehensive development and specialized development.

(3) Natural selection highlights both competition and collaboration, as inferred from Logics 2 and 3 above. Competition leads to the accumulation of structural changes (positive selection) that enhance the OPFM of complex CBMs and the elimination of structural changes (negative selection) that detrimental to the OPFM of complex CBMs. The interplay of positive and negative selection results in a continuous optimization of the internal structures, internal collaboration, and internal orderliness of CBMs ranging from H2-CBMs to H7-CBMs. In essence, the success of a complex CBM in natural selection typically depends on its internal collaboration. For ants, bees, humans, and other animals living in social groups (H6-CBMs and H7-CBMs), their collaborative efforts are essential for the survival of their respective social groups.

(4) Natural selection highlights both selfishness and altruism. Selfishness is essential for animals to secure sufficient energy, resources, favorable environments, and mating opportunities to thrive on Earth. Conversely, altruism is also pervasive throughout evolution. For example, many molecules act as catalysts, energy sources, or building blocks for the synthesis of other molecules within organisms. In H4-CBMs (e.g., bacteria), many molecules aid in the transmission of nucleic acids to the next generation. In H5-CBMs (e.g., rats), many cells assist in the passage of reproductive cells to subsequent generations. In H6-CBMs (e.g., ant colonies), many individual animals support the reproduction of a select few within the social group, and in H7-CBMs, many human soldiers, police officers, and firefighters sacrifice themselves for the good of their society or other individuals.

(5) Natural selection within CBET emphasizes inclusiveness. As per

Logic 1 above, a complex CBM can survive on Earth if its overall formation surpasses its overall degradation, even if its OPFM is lower than that of its ancestor or other CBMs. Thus, natural selection allows organisms to possess certain disadvantages. For example, many individuals harbor gene mutations associated with genetic disorders, and human infants are more fragile compared to those of some other mammals. This indicates that certain biological traits, such as the long necks of giraffes, can be advantageous, neutral, or detrimental in the process of natural selection. The inclusiveness of natural selection corresponds with the prevalence of neutral mutations in genomes [

14], as these mutations have minimal effects on the OPFM of the respective organisms.

(6) Natural selection underscores both inheritable and non-inheritable factors, as they can both significantly affect the OPFM of relevant organisms. For instance, the non-heritable factor of vaccination can increase animals' OPFM, and education can increase humans' OPFM. Sexual selection, no matter whether inheritable and non-inheritable, which is distinct from natural selection and a function and behavior of many animals, highly affects the evolution of animals.

(7) Natural selection underscores a balance between resource exploitation and environmental protection. Firstly, whether an HHCBM has sufficient OPFM in natural selection depends not only on its own characteristics but also on the environment, which provides energy and constituent materials for HHCBMs. Secondly, major environmental changes, such as asteroid impacts, can destroy enormous HHCBMs [

14,

16,

32].

(8) The pressures of natural selection on numerous organisms and societies intensify over time due to competition within species and/or among interacting species, such as predators and prey, parasites and hosts, as well as plants and herbivores. The advancements in adaptations within one population or species are often offset by the simultaneous evolutionary progress of other populations or species. Consequently, if a population or species ceases to evolve, it may be surpassed by other populations or species that persist in adapting and evolving. [

43].

2.3.3. Other Effects of the Natural Selection Mechanism

According to the three mathematical logics stated above, natural selection has the following effects on CBM evolution that have not been elucidated above.

(1) The natural selection of many H2-CBMs is influenced by certain H3-CBMs (e.g., some enzymes that catalyze the production of specific H2-CBMs), H4-CBMs (e.g., bacteria that degrade many H3-CBMs into H2-CBMs through catabolism), and H5-CBMs (e.g., trees that produce numerous H2-CBMs via photosynthesis and other chemical reactions). Consequently, H2-CBMs involved in the creation of organisms, such as amino acids and nucleotides, or in the advancement of human societies, such as gentamicin and various other chemical drugs, are now widespread on Earth, while H2-CBMs not involved in organism formation may be rare on Earth.

(2) The natural selection of many H3-CBMs is influenced by certain H4-CBMs (e.g., bacteria that degrade many H3-CBMs into H2-CBMs through catabolism and synthesize various H3-CBMs through anabolism), H5-CBMs (e.g., trees that produce many H3-CBMs, including celluloses, proteins, and nucleic acids), and H6-CBMs (e.g., companies that produce diverse H3-CBMs for use in manufacturing clothes and shoes). Consequently, H3-CBMs that contribute to the formation of organisms, such as proteins and nucleic acids, or to the development of human societies, such as polyethylene, polypropylene, and polyvinyl chloride, are now prevalent on Earth, while many H3-CBMs not involved in organism formation may be rare on Earth.

(3) The natural selection of many H4-CBMs is influenced by certain H5-CBMs (e.g., rats, which produce numerous new cells and eliminate many old cells daily within their bodies) and H6-CBMs (e.g., some ant colonies, whose growth involves the formation and degradation of their cells). Consequently, H4-CBMs (e.g., certain fungi, bacteria, and cells of H5-CBMs) involved in the formation of H5-CBMs or the sustenance of human societies (e.g., the production of yogurt or antibiotics) have flourished on Earth, while H4-CBMs detrimental to human societies, such as Vibrio cholera and Yersinia pestis, have been mitigated on Earth.

(4) The natural selection of many H5-CBMs is influenced by certain H6-CBMs (e.g., European red ants, which farm aphids to harvest their honeydew [

42]) and H7-CBMs (e.g., countries, whose governance impacts the lives of many humans). Consequently, H5-CBMs that contribute to the advancement of human societies, such as rice, wheat, potatoes, pigs, cows, sheep, and chickens, are now widespread on Earth, while many H5-CBMs harmful to human societies, such as tigers and opium poppies, have been controlled on Earth.

(5) The natural selection of many H6-CBMs is influenced by certain H7-CBMs. For instance, the laws of a country affect the fortunes of many companies within that country. Furthermore, natural selection can lead to improvements in the management of H6-CBMs. Well-managed H6-CBMs have certain advantages in natural selection as they can significantly reduce internal competition and conflict, as well as harness collective strengths to obtain energy and relevant materials for reproduction, maintenance, and defense against predators. For instance, certain ants, such as

Atta colombica, can cultivate fungi as a primary food source [

44], which cannot be achieved by a single ant. Consequently, although social animals sometimes require individuals to sacrifice their freedom and even their lives for the benefit of others, social animals typically have significantly longer lifespans compared to their non-social counterparts within the same taxa [

32,

33]. For instance, the naked mole rat (

Heterocephalus glaber) living in society has a lifespan of up to 30 years, several times longer than that of other rodents [

45]. On the other hand, the natural selection advantages of animal social groups can also lead to intense competition or conflicts between animal social groups. For instance, battles between ant colonies can result in ant massacres [

46].

(6) Natural selection can result in enhanced governance among H7-CBMs through competition, with well-managed H7-CBMs gaining an edge over those that are poorly managed in minimizing internal competition and conflict, securing essential energy and materials for sustenance, and defending against predators or rivals. This enhancement highlights the equilibrium between individual and collective interests within human societies. H7-CBMs tend to grow in size, as larger, well-managed groups generally possess more natural selection benefits than smaller ones. As a result, human social groups have developed from clans to tribes, alliances, nations, and international coalitions. This evolutionary trajectory indicates the potential benefits of uniting all nations into a single, cohesive entity. Moreover, the competitive edge of well-managed H7-CBMs has also amplified the destructiveness of their rivalries and conflicts, including international wars. In 2022, global military spending exceeded

$2.2 trillion, with 238,000 lives lost to conflict [

47]. Technological progress in H7-CBMs, such as nuclear arms and artificial intelligence, has dramatically heightened the potential havoc of international wars, posing a danger to both humanity and the planet. This situation further underscores the critical necessity for global unity to avert the staggering expenses, casualties, and threats inherent in military conflicts.

2.4. The Synergy of the Three Mechanisms Leads to Evolution

As outlined in

Figure 2, the synergy of the above three mechanisms hierarchically escalates the complexity of CBMs, increases the abundance, diversity, and orderliness of complex CBMs, leading to chemical, biological, and social evolution on Earth. Firstly, the driving force mechanism, which arises from the combination of energy and certain functions of relevant CBMs, hierarchically escalates the complexity of CBMs and leads to the repeated cycles of the formation and degradation of complex CBMs (

Section 2.1). Secondly, the hierarchical escalation in the complexity of CBMs and structural changes of complex CBMs during the repeated cycles can generate new functions, which can be beneficial, harmful, or neutral to enhance the OPFM of complex CBMs. This constitutes the structure-function mechanism (

Section 2.2). Thirdly, in mathematics, those functions beneficial to enhance the OPFM of certain complex CBMs, along with the relevant structural changes, will be relatively more abundant on Earth, which constitutes the natural selection mechanism, leading to continuous structural and functional optimization of complex CBMs (

Section 2.3).

Natural selection allows certain complex CBMs to tend to form and maintain their structures using less energy and materials. Meanwhile, the driving force mechanism and the structure-function mechanism collectively allow certain other complex CBMs to tend to form and maintain their bodies using more energy and materials. For example, many primates have become larger in body sizes than their earliest ancestors, which could be as small as mice [

48].

The evolution of CBMs significantly impacts itself. It stores energy, prepares constituent materials, produces catalyzers, generates novel functions, and escalates the natural selection pressure for its subsequent stages (

Figure 2). Furthermore, CBM evolution substantially modifies Earth's surface and environment, leading to opportunities, competition, or disasters for certain CBMs [

43,

49]. For instance, the increase in photosynthetic bacteria around 2.5 billion years ago likely resulted in a significant increase in the concentration of oxygen in the air, posing a disaster for anaerobic bacteria and opportunities for aerobic bacteria [

14,

49].

3. Novelties of CBET

CBET carries the following important novelties.

(1) In general science and philosophy, CBET could offer the first explicit and holistic explanation for chemical, biological, and social evolution, from both a bird's-eye view and an introspective view.

(2) In general science and philosophy, CBET recognizes the complexity of evolution and innovatively employs three mechanisms to explain evolution, while previous studies underestimated the complexity of evolution and tried to explain evolution using a single mechanism, such as natural selection in Darwin's theory [

14], entropy dissipation into the surroundings in Schrödinger's negative entropy notion [

2], self-organization in Prigogine's dissipative structure theory [

3], the constructal law [

50], the maximum entropy production hypothesis [

4], the free-energy principle [

51], Eigen's hypothesis of hypercycles proposed for interpreting the origin of life [

52], and the RNA world hypothesis [

53]. These one-single-mechanism theories or hypotheses are either elusive or incomplete, primarily focusing on specific aspects of chemical, biological, or social evolution using an introspective methodology. Additionally, Eigen's hypothesis of hypercycles and the RNA world hypothesis both underscored the organic syntheses of a few kinds of special molecules through autocatalysis [

52,

53], while CBET underscores allocatalysis and collaboration of various common CBMs (

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3 and

Section 2.4). Autocatalysis is much rarer than allocatalysis both in biosphere and abiotic environments [

8,

39,

40,

41], and should be thus much less important than allocatalysis for evolution.

(3) In general science and philosophy, the three evolutionary mechanisms of CBET innovatively clarify the intricate relationships among the four basic concepts associated with evolution: energy, structures, functions, and orderliness (

Figure 2). In contrast, the relationships of these basic concepts have been frequently entangled with certain elusive notions associated with entropy [

54], as shown in the following paragraph.

(4) In physics, CBET innovatively interprets the relationships between the second law of thermodynamics and evolution. It is widely stated in textbooks and encyclopedias that entropy represents disorder and consequently, the second law of thermodynamics contradicts evolution, as this law seems to validate that many systems tend to increase their entropy and thus become more disordered [

1,

2,

3,

50,

54]. Creationists have exploited this perceived contradiction to argue against evolution [

1,

55]. Some influential theories, such as Schrödinger's negative entropy theory and Prigogine's dissipative structure theory, accepted and reconciled this contradiction by suggesting that open systems (like organisms) can gain orderliness not through natural selection but through the dissipation of entropy into the environment [

2,

3]. In contrast, CBET embraces the new notion that entropy does not represent disorder [

54,

56], as entropy is analogous to energy with the unit of joule/kelvin, representing the quotient of heat energy and the corresponding thermodynamic temperature, while disorder refers to chaos, untidiness, or abnormalities, and is not analogous to energy [

54,

56]. The unit of disorder is not joule/kelvin, either. Consequently, CBET supports the new notion that the second law of thermodynamics does not suggest that many systems tend to become more disordered and hence this law does not contradict evolution [

54,

56]. Moreover, CBET clarifies that this thermodynamic law is highly associated with the driving force of evolution (

Section 2.1), which aligns with some other research reports [

50,

55].

(5) In biology, as elucidated in

Section 2.1, CBET innovatively reveals the driving force of biological evolution in terms of energy. Previous studies posited that natural selection, mutations, or genetic drift are the driving forces of evolution [

57,

58,

59], but these factors require energy and do not provide energy.

(6) In biology, as elucidated in

Section 2.3, CBET innovatively provides comprehensive explanations for the mathematical essence of natural selection, the targets of natural selection, and biological altruism from a bird's-eye view.

(7) In biology, the inclusiveness of natural selection, along with the driving force mechanism, the variability of complex CBMs, and the structure-function mechanism, innovatively and explicitly interprets the increasing biodiversity on Earth and certain macroevolution events. For instance, organisms, multicellular organisms, and endothermic animals are not inherently fitter than inanimate materials, unicellular organisms, and ectothermic animals, respectively, yet their total formation can all exceed their total degradation due to some functions generated by the structure-function mechanism, the energy supplied by the driving force mechanism, and the materials supported by the environment. In contrast, previous theories emphasized the fierce competition in natural selection, which was expressed as “survival of the fittest” in Darwin's theory and “gradual replacement of populations with those carrying advantageous mutations” in the Modern Synthesis [

14]. These previous theories could not explain the above macroevolution events [

1].

(8) In biology, neither Darwin's natural selection nor the Modern Synthesis can incorporate non-random mutations [

60,

61], neutral mutations [

14], epigenetic changes [

62,

63], and non-heritable strengths [

14], which are prevalent in or important for numerous organisms. In contrast, CBET can innovatively incorporate these facts, as non-random mutations and epigenetic changes can be realized through the structure-function mechanism, neutral mutations affect little the OPFM of organisms, and epigenetic changes and certain non-heritable strengths can significantly affect the OPFM of organisms [

4].

(9) In the social sciences, CBET innovatively uncovers the natural roots of the balance between multiple pivotal and seemingly paradoxical social notions, such as all-round development versus specialized development, inclusiveness versus elimination, collaboration versus competition, altruism versus selfishness, and resource exploitation versus environmental protection (

Section 2.3). Accordingly, CBET advocates for the balanced and harmonious development of human society. Historically, nations that adopted relatively balanced and harmonious development in their social governance often performed powerfully in international competitions [

64]. CBET also suggests that in the future it is better for all nations to be unified into a single, harmonious entity to avoid too expensive and disastrous international wars (

Section 2.3). In contrast, Darwin's natural selection only emphasizes selfishness, competition, and the elimination of the less advantaged and has been used to rationalize wars, colonialism, slavery, racism, and genocide [

15].

(10) CBET highlights the structural hierarchies of CBMs or organisms using the innovative terminology of the eight hierarchies of CBMs. Although hierarchies have also been highlighted for decades or even hundreds of years in the research of evolutionary theories [

65], previous research has neither systematically categorized CBMs into the eight hierarchies nor utilized structural hierarchies to deduce the driving force and mechanisms of CBM evolution [

65].

4. Credibility of CBET

CBET is credible for the following reasons:

(1) CBET is established through the novel integration of well-established knowledge from diverse disciplines, and the integration utilizes precise logic and proper terminology, such as the eight hierarchies of CBMs, making CBET a novel, credible, and self-consistent theory.

(2) CBET contains neither elusive nor weird concepts. Meanwhile, to our knowledge, CBET does not contradict any established facts across physics, chemistry, biology, geology, astronomy, and the social sciences.

(3) The rapid advancements in scientific research in physics, chemistry, biology, geology, astronomy, and social sciences over the past two centuries have revealed numerous factors critical for CBM evolution (

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3 and

Section 2.4). CBET precisely integrates and aligns with these numerous critical factors. In contrast, previous research typically emphasized only a limited number of critical factors. For instance, the Modern Synthesis did not address the chemical properties of carbon atoms, the laws of thermodynamics, the reactions of organic chemistry, or the inclusiveness of social sciences.

(4) CBET avoids diverse pitfalls that many previous studies fell into, such as the misconceptions that entropy is a measure of disorder and that the second law of thermodynamics contradicts evolution [

1,

54,

56].

(5) As shown in

Section 3, CBET is superior to other theories in explaining multiple evolutionary issues, which reinforces its credibility.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The evolutionary theory of CBET, as delineated in this article through the systematic integration of well-established interdisciplinary knowledge, offers an explicit, evidence-supported, and holistic explanation for chemical, biological, and social evolution. It clarifies the intricate relationships among energy, structures, functions, and orderliness. Additionally, it reveals the natural roots of multiple pivotal social notions. As such, it has the potential to bridge the natural sciences and social sciences.

As a novel theory, CBET would benefit from additional validation and refinement. Should it gain widespread acceptance, CBET could be a basic theory of sciences, directing research and education across a variety of scientific disciplines. Also, CBET can guide the rational development of human society because it advocates for the balanced, harmonious, and peaceful development of human societies.

Author Contributions

JMC and JWC conceptualized, designed, and performed this study. JMC wrote this article and JMC and JWC revised this article. JMC acquired the fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Meng Yang and Yiqing Chen for their numerous constructive comments. This work was supported by the High-Level Talent Fund of Foshan University (No. 20210036).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Xie, P. 2014 The aufhebung and breakthrough of the theories on the origin and evolution of life. Beijing, China: Science Press.

- Schrödinger E. 2012 What is Life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Prigogine I. 1978 Time, structure and fluctuation. Science 201, 777–785. [CrossRef]

- Dewar RC. 2010 Maximum entropy production and plant optimization theories. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 365, 1429–1435. [CrossRef]

- Oparin AI. 1969 Chemistry and the origin of life. R. Inst. Chem. Rev. 2, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Fu S, Ying J, Zhao Y. 2023 Prebiotic chemistry: a review of nucleoside phosphorylation and polymerization. Open Biol. 13, 2202–2234. [CrossRef]

- Sumie Y, Sato K, Kakegawa T, Furukawa Y. 2023 Boron-assisted abiotic polypeptide synthesis. Commun. Chem. 6, 89. [CrossRef]

- de Graaf R, De Decker Y, Sojo V, Hudson R. 2023 Quantifying catalysis at the origin of life. Chemistry 29, e202301447. [CrossRef]

- Nogal N, Sanz-Sánchez M, Vela-Gallego S, Ruiz-Mirazo K, de la Escosura A. 2023. The protometabolic nature of prebiotic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 7359–7388. [CrossRef]

- Chieffo C, Shvetsova A, Skorda F, Lopez A, Fiore M. 2023 The origin and early evolution of life: Homochirality emergence in prebiotic environments. Astrobiology 23, 1368–1382. [CrossRef]

- Fiore M. 2022 Prebiotic chemistry and life's origin. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Farías-Rico JA, Mourra-Díaz CM. 2022 A short tale of the origin of proteins and ribosome evolution. Microorganisms 10, 2115. [CrossRef]

- Ershov B. 2010 Natural radioactivity and chemical evolution on the early Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 2763–2768. [CrossRef]

- Futuyma DJ, Kirkpatrick M. 2017. Evolution. Sunderland, USA: Sinauer Associates.

- Rudman LA, Saud LH. 2020 Justifying social inequalities: The role of social Darwinism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B. 46, 1139–1155. [CrossRef]

- Nowak M, Tarnita C, Wilson E. 2010 The evolution of eusociality. Nature 466, 1057–1062. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. 2019. The Earth book. Sterling, USA: Sterling.

- Razeghi, M. 2019 The mystery of carbon: An introduction to carbon materials. Bristol, UK: Institute of Physics Publishing.

- Cowan J. 2012 One of the first of the second stars. Nature 488, 288–289. [CrossRef]

- Seager S. 2013 Exoplanet habitability. Science 340, 577–581. [CrossRef]

- Borgnakke C, Sonntag RE. 2022 Fundamentals of thermodynamics. Hoboken, United States: Wiley.

- Schmitt-Kopplin P, Gabelica Z, Gougeon RD, et al. 2010. High molecular diversity of extraterrestrial organic matter in Murchison meteorite revealed 40 years after its fall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 2763–2768. [CrossRef]

- Dodd MS, Papineau D, Grenne T, et al. 2017 Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates. Nature 543, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Weiss MC, Sousa FL, Mrnjavac N, et al. 2016 The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor. Nat. Microb. 1, 16116. [CrossRef]

- Stobart CC, Moore ML. 2014 RNA virus reverse genetics and vaccine design. Viruses 6, 2531–2550. [CrossRef]

- Hutchison CA 3rd, Chuang RY, Noskov VN, et al. 2016 Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 351, aad6253. [CrossRef]

- Xie P. 2021 Who is the missing "matchmaker" between proteins and nucleic acids? Innovation (Camb) 2, 100120. [CrossRef]

- Han TM, Runnegar B. 1992 Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old Negaunee iron-formation, Michigan. Science 257, 232–235. [CrossRef]

- Zhu S, Zhu M, Knoll A, et al. 2016 Decimetre-scale multicellular eukaryotes from the 1.56-billion-year-old Gaoyuzhuang formation in North China. Nat. Commun. 7, 11500. [CrossRef]

- Anderson RP, Woltz CR, Tosca NJ, Porter SM, Briggs DEG. 2023 Fossilisation processes and our reading of animal antiquity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 1060–1071. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Yin X, Shih C, Gao T, Ren D. 2020 Termite colonies from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar demonstrate their early eusocial lifestyle in damp wood. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 381–390. [CrossRef]

- Mera-Rodríguez D, Jourdan H, Ward PS, Shattuck S, Cover SP, Wilson EO, Rabeling C. 2023 Biogeography and evolution of social parasitism in Australian Myrmecia bulldog ants revealed by phylogenomics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 186, 107825. [CrossRef]

- Plowers N. 2010. An introduction to eusociality. Nature Education Knowledge 3, 7.

- Majelantle TL, Ganswindt A, Hart DW, Hagenah N, Ganswindt SB, Bennett NC. 2024 The dissection of a despotic society: exploration, dominance and hormonal traits. Proc. Biol. Sci. 291, 20240371. [CrossRef]

- Li ZH, Bailleul AM, Stidham TA, Wang M, Teng T. 2021 Exceptional preservation of an extinct ostrich from the Late Miocene Linxia Basin of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 59, 229. [CrossRef]

- Heck PR, Greer J, Kööp L, et al. 2020 Lifetimes of interstellar dust from cosmic ray exposure ages of presolar silicon carbide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 1884–1889. [CrossRef]

- Reichlem, DE. 2023 The global carbon cycle and climate change. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

- von Bertalanffy, L. 1968 General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. George Braziller.

- Lovinger GJ, Sak MH, Jacobsen EN. 2024 Catalysis of an SN2 pathway by geometric preorganization. Nature 632, 1052–105. [CrossRef]

- Stone EA, Cutrona KJ, Miller SJ. 2020 Asymmetric catalysis upon helically chiral loratadine analogues unveils enantiomer-dependent antihistamine activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12690–12698. [CrossRef]

- Morrell, DG. 2019 Catalysis of organic reactions. Boca Raton, USA: CRC Press.

- Kilpeläinen J, Finér L, Neuvonen S, et al. 2009 Does the mutualism between wood ants (Formica rufa group) and Cinara aphids affect Norway spruce growth? For Ecol Manage 257, 238–243.

- Benton MJ. 2009 The red queen and the Court Jester: species diversity and the role of biotic and abiotic factors through time. Science 323, 728–732. [CrossRef]

- Suen G, Teiling C, Li L, et al. 2011 The genome sequence of the leaf-cutter ant Atta cephalotes reveals insights into its obligate symbiotic lifestyle. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002007. [CrossRef]

- Kim E, Fang X, Fushan A, et al. 2011 Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat. Nature 479, 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Moffett, MW. 2010 Adventures among ants. University of California Press is located in Oakland, United States: University of California Press.

- SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Available online: https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Wilson Mantilla GP, Chester SGB, Clemens WA, et al. 2021 Earliest Palaeocene purgatoriids and the initial radiation of stem primates. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 210050. [CrossRef]

- Olejarz J, Iwasa Y, Knoll AH, et al. 2021 The Great Oxygenation Event as a consequence of ecological dynamics modulated by planetary change. Nat. Commun. 12, 3985. [CrossRef]

- Bejan A. 2023 The principle underlying all evolution, biological, geophysical, social and technological. Philos. Trans. A. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 381(2252), 20220288. [CrossRef]

- Ramstead MJD, Badcock PB, Friston KJ. 2018 Answering Schrödinger's question: A free-energy formulation. Phys. Life Rev. 24, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman SA. 2011 Approaches to the origin of life on the Earth. Life (Basel) 1, 34–48. [CrossRef]

- Robertson MP, Joyce GF. 2012 The origins of the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a003608. [CrossRef]

- Chen JM, Chen JW, Zivieri R. 2024 Systematically challenging three prevailing notions about entropy and life. Qeios. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber A, Gimbel S. 2010 Evolution and the second law of thermodynamics: Effectively communicating to non-technicians. Evo. Edu. Outreach 3, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Chen JM, Chen JW. 2000 Root of science—the driving force and mechanisms of the extensive evolution.Beijing, China: Science Press.

- Ma S, Guo Y, Liu D, et al. 2023 Genome-wide analysis of the membrane attack complex and perforin genes and their expression pattern under stress in the Solanaceae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 13193. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liu X, Wang C, et al. 2023 The pig pangenome provides insights into the roles of coding structural variations in genetic diversity and adaptation. Genome Res. 33, 1833–1847. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Li X, Feng Y. 2023 Autotetraploid origin of Chinese cherry revealed by chromosomal karyotype and in situ hybridization of seedling progenies. Plants (Basel) 12, 3116. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald DM, Rosenberg SM. 2019 What is mutation? A chapter in the series: How microbes “jeopardize” the modern synthesis. PLoS Genet. 15, e1007995. [CrossRef]

- Olivieri DN, Mirete-Bachiller S, Gambón-Deza F. 2021 Insights into the evolution of IG genes in amphibians and reptiles. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 114, 103868. [CrossRef]

- Sabarís G, Fitz-James MH, Cavalli G. 2023 Epigenetic inheritance in adaptive evolution. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1524, 22–29. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Schiavon M, Buchler NE. 2019 Epigenetic switching as a strategy for quick adaptation while attenuating biochemical noise. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15: e1007364. [CrossRef]

- McNeill JR, Pomeranz K. 2015 The Cambridge World History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Eldredge N, Pievani T, Serrelli E, Tëmkin I. 2016 Evolutionary theory: A hierarchical perspective. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).