Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

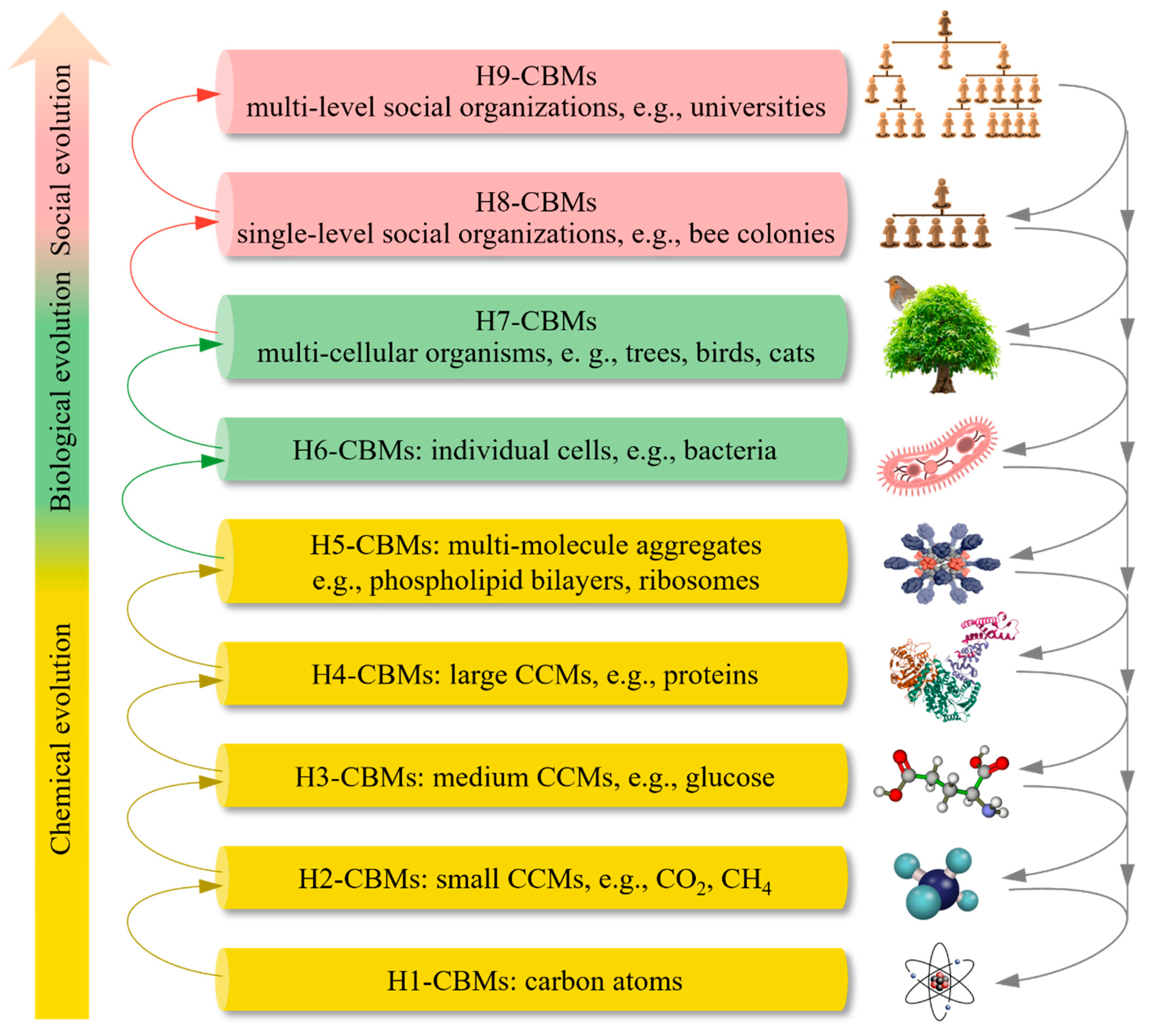

Hierarchies and Functions of CBMs

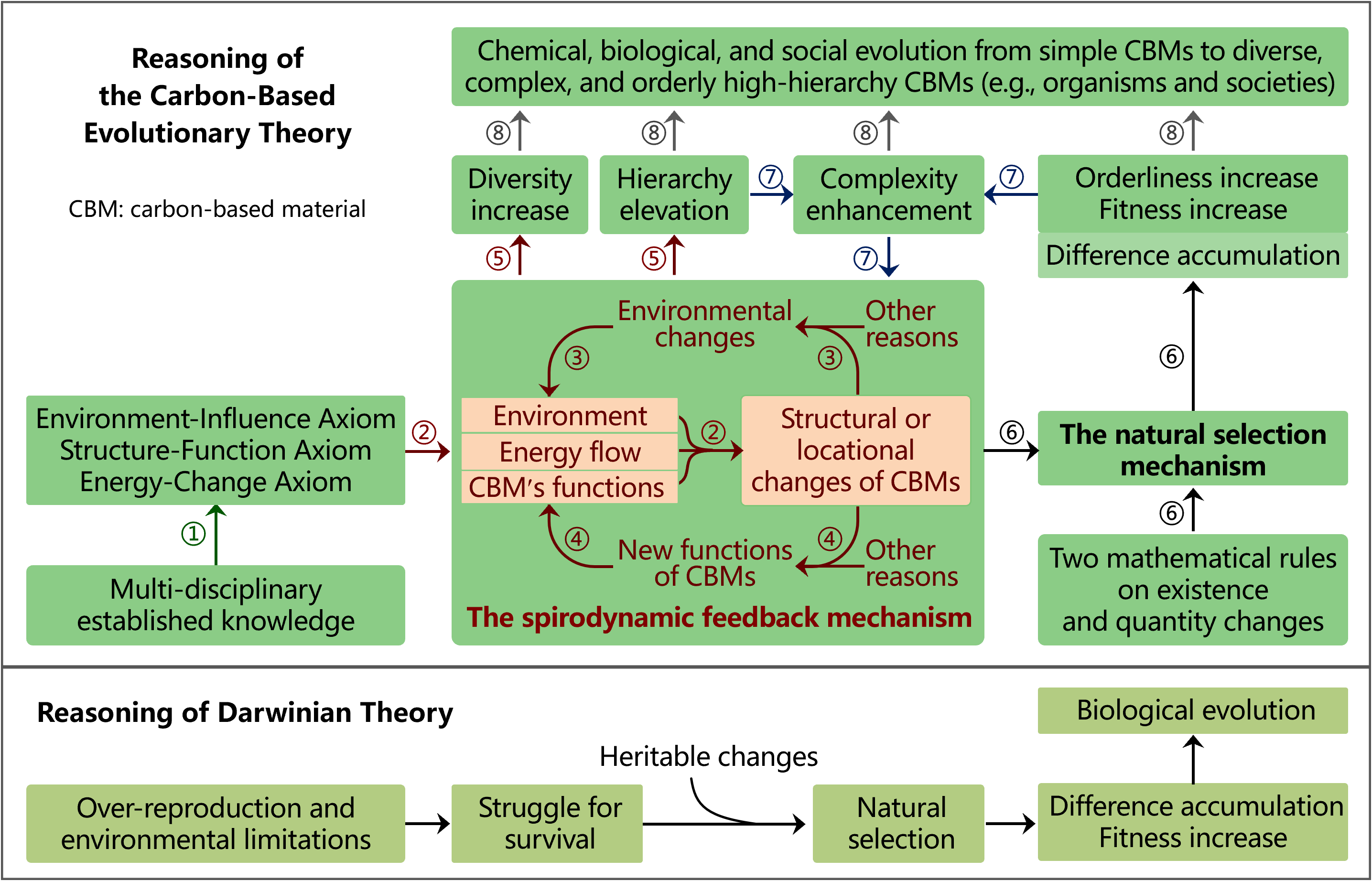

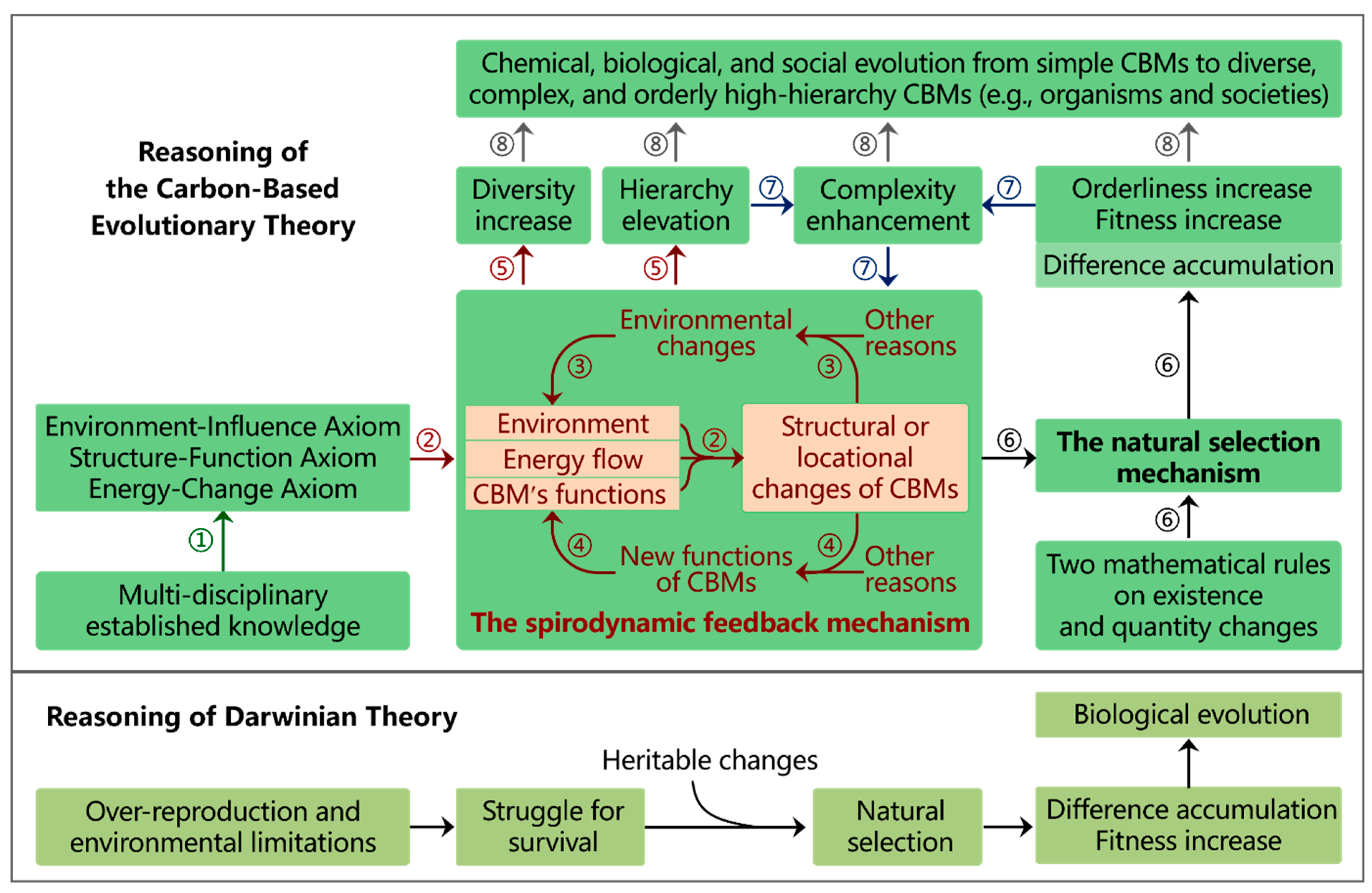

Reasoning Steps of CBET

Explanation of Life’s Origin

Clarification of Misunderstandings

Validation of CBET

Discussion

Methods

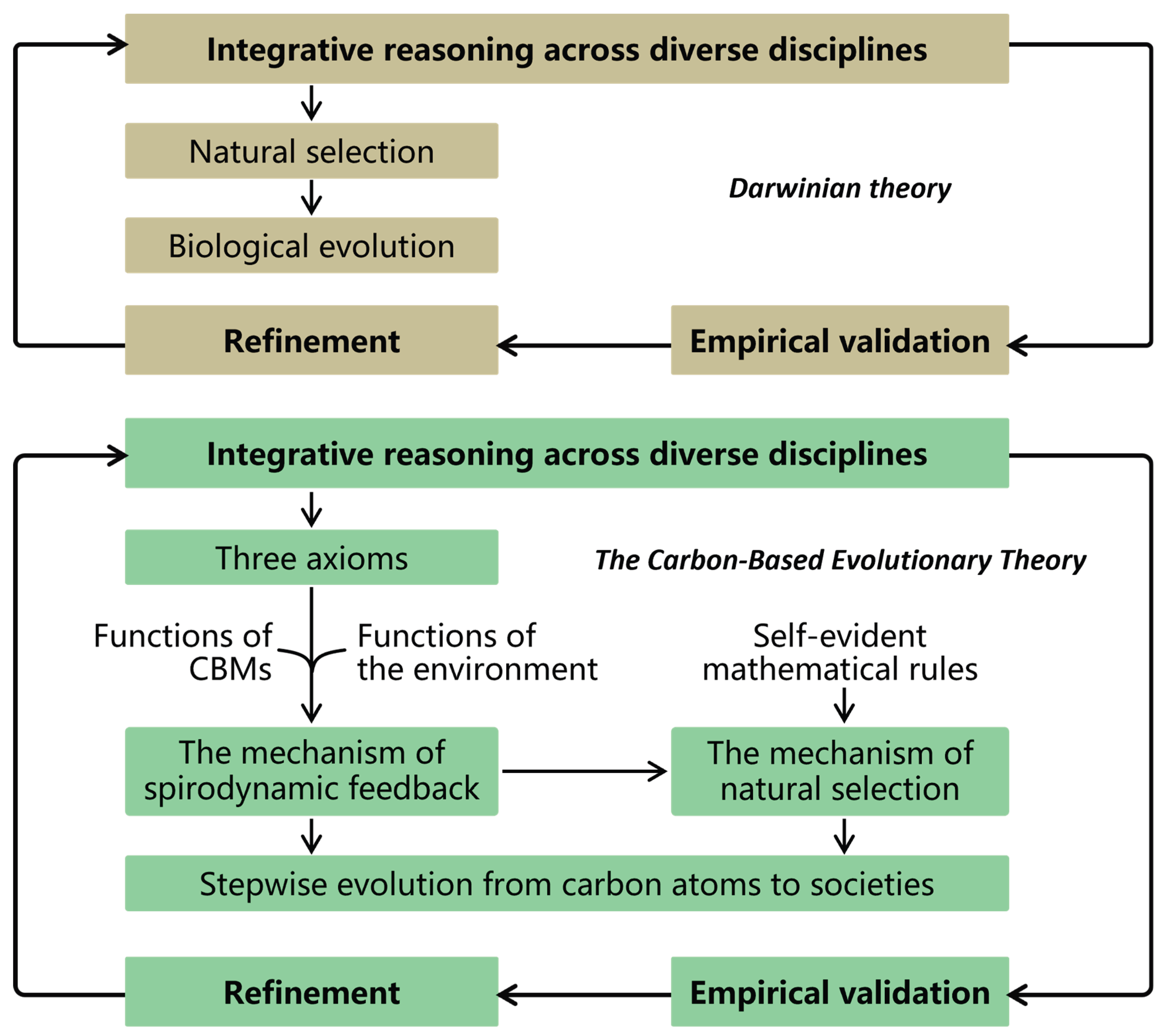

Methodology of CBET

Integrative Reasoning of CBET

Empirical Validation of Spriodynamic Feedback

- ✧

- They require or rely on energy flow.

- ✧

- They are influenced by environmental factors.

- ✧

- They rely on functions of the relevant material, which are partially determined by the structure of the relevant material.

- ✧

- They demonstrate that structural changes can generate new, emergent functions, which can initiate further structural changes, establishing a feedback loop that can lead to hierarchical elevation, as illustrated by Facts 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, and 25.

- ✧

- They show that structural or locational changes can alter the environment, which can in turn feedback to initiate further structural changes, as evidenced by Facts 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 18, 20, and 27.

Empirical Validation of Natural Selection

Evaluation of Conceptual Clarity and Logical Coherence

Refinement of CBET

Other Issues

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species 1st edn (John Murray, 1859).

- Futuyma, D. J. & Kirkpatrick, M. Evolution 4th edn (Sinauer Associates, 2017).

- Chen, J. M. A new evolutionary theory deduced mathematically from entropy amplification. Chin. Sci. Bull. 45, 91–96 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Xie, P. The Aufhebung and Breakthrough of the Theories on the Origin and Evolution of Life (Science Press, 2014).

- Oparin, A. I. Chemistry and the origin of life. R. Inst. Chem. Rev. 2, 1–12 (1969).

- Fiore, M. Prebiotic Chemistry and Life’s Origin (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2022).

- Nowak, M. A., Tarnita, C. E. & Wilson, E. O. The evolution of eusociality. Nature 466, 1057–1062 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Birch, J. The Philosophy of Social Evolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

- Cowan, J. J. One of the first of the second stars. Nature 488, 288–289 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, M. The Mystery of Carbon: An Introduction to Carbon Materials (IOP Publishing, 2019).

- Heck, P. R. et al. Lifetimes of interstellar dust from cosmic ray exposure ages of presolar silicon carbide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 1884–1889 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. H. et al. Exceptional preservation of an extinct ostrich from the Late Miocene Linxia Basin of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 59, 229–248 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Reichle, D. E. The Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Change 2nd edn (Elsevier, 2023).

- Seager, S. Exoplanet habitability. Science 340, 577–581 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L. E. et al. A geological and chemical context for the origins of life on early Earth. Astrobiology 24 (S1), S76–S106 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Olejarz, J., Iwasa, Y., Knoll, A. H. & Nowak, M. A. The Great Oxygenation Event as a consequence of ecological dynamics modulated by planetary change. Nat. Commun. 12, 3985 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Benton, M. J. The Red Queen and the Court Jester: species diversity and the role of biotic and abiotic factors through time. Science 323, 728–732 (2009). [CrossRef]

- De Capitani, J., Mutschler, H. The long road to a synthetic self-replicating central dogma. Biochemistry 62(7), 1221–1232 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Marchi, S. & Korenaga, J. The shaping of terrestrial planets by late accretions. Nature 641, 1111–1120 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Fu, S., Ying, J. & Zhao, Y. Prebiotic chemistry: a review of nucleoside phosphorylation and polymerization. Open Biol. 13, 220234 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nam, I., Lee, J. K., Nam, H. G. & Zare, R. N. Abiotic production of sugar phosphates and uridine ribonucleoside in aqueous microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12396–12400 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Dobson, C. M., Ellison, G. B., Tuck, A. F. & Vaida, V. Atmospheric aerosols as prebiotic chemical reactors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11864–11868 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Griffith, E. C. & Vaida, V. In situ observation of peptide bond formation at the water-air interface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15697–15701 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Trainer, M. G. Atmospheric prebiotic chemistry and organic hazes. Curr. Org. Chem. 17, 1710–1723 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Q. et al. Sexual selection promotes giraffoid head-neck evolution and ecological adaptation. Science 376, eabl8316 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene (Oxford Univ. Press, 1976).

- Low, D. A. Advantage of an epigenetic switch in response to alternate environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2416356121 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Veigl, S. J., Vasilyeva, Z. & Müller, R. Scientific-intellectual movements in the post-truth age: The case of the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., Chen, J. W. & Zivieri, R. Systematically challenging three prevailing notions about entropy and life. Qeios 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, D. M. & Rosenberg, S. M. What is mutation? A chapter in the series: How microbes “jeopardize” the modern synthesis. PLoS Genet. 15, e1007995 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Fine, J. L. & Moses, A. M. An RNA condensate model for the origin of life. J. Mol. Biol. 437, 169124 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T. Reconsidering the logical structure of the theory of natural selection. Commun. Integr. Biol. 7, e972848 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. C. et al. Key for hexagonal diamond formation: theoretical and experimental study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 2158–2167 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Stobart, C. C. & Moore, M. L. RNA virus reverse genetics and vaccine design. Viruses 6, 2531–2550 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, C. A. et al. Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 351, aad6253 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. Time, structure and fluctuation. Science 201, 777–785 (1978). [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M. J. D., Badcock, P. B. & Friston, K. J. Answering Schrödinger’s question: A free-energy formulation. Phys. Life Rev. 24, 1–16 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 127–138 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L. A. & Saud, L. H. Justifying social inequalities: The role of social Darwinism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 1139–1155 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sober, E. & Wilson, D. S. Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior (Harvard Univ. Press, 1998).

- Eldredge, N., Pievani, T., Serrelli, E. & Tëmkin, I. Evolutionary Theory: A Hierarchical Perspective (Univ. Chicago Press, 2016).

- Miller, J. H. & Page, S. E. Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life (Princeton Univ. Press, 2007).

- Sabater, B. Entropy Perspectives of Molecular and Evolutionary Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 4098 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. What is Life (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

- Bejan, A. The principle underlying all evolution, biological, geophysical, social and technological. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 381, 20220288 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R. C. Maximum entropy production and plant optimization theories. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 1429–1435 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Borgnakke, C. & Sonntag, R. E. Fundamentals of Thermodynamics (Wiley, 2022).

- Schmitt-Kopplin, P. et al. High molecular diversity of extraterrestrial organic matter in Murchison meteorite revealed 40 years after its fall. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2763–2768 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wang, Z., Bai, J. & Qiao, H. Prebiotic peptide synthesis: How did longest peptide appear? J. Mol. Evol. 93, 193–211 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., Liu, A., Li, X. & Miao, Z. Research progress on mRNA drug delivery strategies in the nervous system. Nanomedicine 20, 1955–1970 (2025). [CrossRef]

| Darwinian theory | The Carbon-Based Evolutionary Theory | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Biological evolution | Chemical, biological, and social evolution |

| Core concept | Organisms | Carbon-based materials (CBMs) |

| Mechanisms | Natural selection that shapes evolution | Spriodynamic feedback (drives evolution) and natural selection (shapes evolution) |

| Fitness calculation | The number of an individual’s offspring in the next generation | The formation-to-degradation ratio of a CBM over a time interval |

| Life’s origin | Did not explain life’s origin | Schematically accounts for life’s origin |

| Inclusiveness | Could not fully integrate neutral or detrimental mutations with natural selection | Integrates the prevalence of neutral or detrimental mutations with natural selection |

| Changes under selection | Focused on heritable genetic changes | Highlights the roles of genetic, epigenetic, and non-heritable changes |

| Primary significance | Unveiled the natural selection mechanism; challenged creationism and inheritance of acquired traits | Establishes a coherent framework theory that explicitly and schematically explains chemical, biological, and social evolution |

| Social significance | Could not establish natural-science-grounded foundations for social sciences or for harmonious societal development | Establishes natural-science-grounded foundations for social sciences and for harmonious societal development |

| Order | Description of the fact |

|---|---|

| 1 | Charcoal combustion which consumes oxygen and forms carbon dioxide |

| 2 | Diamond synthesis from graphite under certain conditions [33] |

| 3 | Water adsorption of activated carbon |

| 4 | CO2, NH3, and other molecules form amino acids via chemical reactions [2,5] |

| 5 | Methane explosion in coal mines |

| 6 | Evaporation of ethanol from an open bottle |

| 7 | The dehydration condensation of amino acids into peptides in tubes |

| 8 | The binding of gentamicin to the 30S ribosomal subunit of some bacteria |

| 9 | The degradation of glucose into carbon dioxide and water in cells |

| 10 | Some recombinant proteins self-assembling into virus-like particles |

| 11 | DNA synthesis catalyzed by a protein |

| 12 | Starch degradation in the stomach |

| 13 | Inputting certain DNA molecules into certain cells can create new viruses [34] |

| 14 | Inputting certain DNA molecules into certain cells can create new cells [35] |

| 15 | The formation of bilayer vesicles by amphiphilic lipid molecules |

| 16 | The development of a fertilized egg into a tadpole |

| 17 | Escherichia coli absorbs glucose via its membrane carrier proteins |

| 18 | The reproduction of bacteria within chicken intestines |

| 19 | A group of ant individuals form a eusocial ant colony |

| 20 | Some trees undergo spring budding and autumn leaf shedding |

| 21 | A car collision causes human casualties |

| 22 | The formation of a basketball team by a group of young people |

| 23 | Leafcutter ants harvest foliage to cultivate symbiotic fungi in their nests |

| 24 | The destruction of a beehive by a forest fire |

| 25 | Several institutions merged into Paris-Saclay University in 2018 |

| 26 | University of the Arts Philadelphia was closed in 2024 |

| 27 | The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).