1. Introduction

There is a great interest in sleep in both the general public and the scientific community. The critical influence of sleep on health and some aspects of cognition is well established1-3; moreover, our modern lifestyle and technologies affect our sleep habits and quality in new ways every day, increasing the prevalence of sleep deprivation and bad sleep habits4-7. Memory is also a focus of societal interest, with respect to education and learning on one side of the developmental spectrum, and to aging and age-related memory decline on the other. As such, the effect of sleep on memory has gained much attention in psychology and neuroscience research over the last two decades, with thousands of dedicated publications. Additionally, a number of theories and models explaining the effect of sleep on memory have been developed e.g., 8,9-23. The focus of this paper is on the effect of sleep on memory consolidation at behavioral level; that is, on how sleeping after having learned something (e.g., new vocabulary or playing the piano) benefits subsequent memory, compared to an equivalent time spent without sleep. We follow the primacy of behavioral research for understanding the brain principle24,25: before we get to neuroscience methods, we need to optimize behavioural design and methods. For scope reasons, in this article, we will not focus on the biological mechanisms or neural substrates for memory consolidation.

According to prominent empirical studies e.g., 26,27 and reviews on this topic 12,28,29, in healthy adults declarative memory appears more resistant to forgetting when encoding is followed by a period of sleep compared to a period of wakefulness, whereas non-declarative memory performance can even be improved when sleep follows training. The evidence for sleep-related memory consolidation appears to be so convincing that it has been claimed that “While memory formation is not the only function of sleep, it seems to be the most important (...)” 30 or that "(...) active system consolidation might be an evolutionary conserved function of sleep.” 31. While such judgements may be justified if based on a large body of rather heterogenous experimental approaches, we claim here that the support such statements receive from individual experiments is not yet compelling, due to several experimental and methodological issues. Indeed, there has been critical discussion as to the actual impact of sleep on memory consolidation e.g., 32,33-37. A non-negligible number of studies have not found sleep-related consolidation effects, especially for non-declarative memory e.g., 38,39-43. There is also increasing evidence that the effect of sleep on memory consolidation is perhaps more multifaceted than initially thought e.g., 28. In addition, the correlations observed between sleep electrophysiology (e.g., sleep spindles, stage 2 NREM sleep) and memory consolidation are often not replicated across studies and are sometimes too numerous that it becomes difficult to reliably interpret the significant ones 32,35,44. They sometimes even go in the opposite direction than what is expected 33,45. Contradictory findings in the field are not an issue per se, as they can highlight the complexity of the effect of sleep on memory consolidation. Those findings become an issue, however, if they point to systematic problems with the literature. Thus, providing guidelines for future studies is crucial to maintaining progress in the field.

In this Perspective, we propose a guideline for future research on sleep and memory. Such a comprehensive guideline is lacking so far (but see 28), hindering the progress toward a better understanding of the effect of sleep on memory in fields ranging from psychology to biology and neuroscience. We highlight four methodological issues that could be responsible for some of the contradictory findings in the literature, and then propose solutions for them to guide future research.

1.1. Experimental design

In this section, we identify five areas that could benefit from improvements in the experimental designs and suggest solutions for each of them.

Figure 1 illustrates the main study conditions that can be included in the experimental designs testing the effect of sleep on memory consolidation. It is important to note from the outset that it is difficult to address all of these methodological caveats in one parsimonious experimental design. Thus, several types of studies may be necessary to draw strong conclusions about the function of a particular type of sleep for a particular type of memory

46.

The issues with non-optimal experimental designs can be organized into three sets. The first one is related to the influence of the time of day when the tasks are performed. The second is about whether the observed benefit of sleep over wake intervals is just due to the fact that, during sleep, interference is much diminished. This issue is related to the fundamental question of whether sleep passively (through reduced interference) or actively (through sleep-specific neural processes) contributes to memory consolidation for in depth discussion see 47. If sleep has only a passive role in this regard, then creating wake intervals with reduced external interferences during the post-learning interval may be sufficient to trigger a level of consolidation comparable to that of a sleep interval. Finally, we also briefly discuss the effect of baseline measurements and feedback on performance changes in the retention interval, because differences in these aspects of the experimental design can further confound the observed relationship between sleep and memory.

1.2. Time-of-day (circadian) effects

It has been shown that learning and memory performance is affected by the time of day when the task is performed

48,49 (for negative results, see

50). Time-of-day (circadian) effects can lead to confounds in sleep-related consolidation studies. A typical approach in these studies is to compare performance change in a Sleep condition (i.e., learning in the evening and testing memory the next morning;

Figure 1, condition 1) with that in a Wake condition (i.e., learning in the morning and testing memory the next evening; condition 2). Importantly, however, a greater off-line improvement in a Sleep condition compared to a Wake condition in such a design may be, at least partially, explained by two confounds: worse performance in the evening (i.e., when learning takes place in the Sleep condition) due to circadian effects, including day-long buildup of fatigue

51; and/or a better performance in the morning (i.e., when testing takes place in the Sleep condition) when participants are likely well rested. Probing circadian effects, one meta-analysis

32 of sleep-related motor memory consolidation showed that performance is best if the test session occurs in the early afternoon. Notably, the issue of circadian effects can be even more pronounced over the course of the human lifespan, especially when comparing young vs. older groups of individuals with differences in chronotype and homeostatic sleep pressure

52. In either case, it is unclear to what extent sleep

per se contributes to improved performance compared to these circadian effects.

Moreover, hormones like cortisol strongly influence memory processes, and their release is subject to distinct circadian rhythms. For instance, growth hormone (GH) peaks in the first half of the night, whereas GH concentrations in the second half are very low. By contrast, cortisol has its daily nadir in the first half of the night and its peak in the second half

53. This confounds not only evening-morning vs. morning-evening (

Figure 1, conditions 1 vs. 2, respectively) comparisons but also within-night comparisons that are permitted by the classical split-night paradigm, which compares the slow wave sleep (SWS)-rich first half of the night with the rapid eye-movement (REM) sleep-rich second half of the night

54. Thus, the confounds of endocrine fluctuations across the circadian rhythm are difficult to avoid, rendering the split-night paradigm problematic.

These potential circadian effects are not easy to control because, in humans, sleep typically occurs during the night (although see 55 for an inverted 12-hour schedule with sleep occurring during daytime). Nevertheless, several solutions have been proposed to address this potential caveat. None are ideal nor exhaustive, but a combination of converging results across studies employing these different strategies can accrue confidence in the conclusions.

When focusing on the effects of nighttime sleep on memory consolidation, e.g., in an evening-morning (Sleep) vs. morning-evening (Wake) design (

Figure 1, conditions 1 vs. 2, respectively), additional control groups should be tested to disentangle the circadian effects from the effect of sleep

per se. Thus, a full design would include evening-morning (i.e., 12h Sleep; condition 1) and morning-evening (i.e., 12h Wake; condition 2) conditions, together with evening-alone (condition 3) and morning-alone (condition 4) conditions, the latter two conditions with immediate testing. A difference in

learning performance (i.e., how long it takes to learn or the overall performance during training) and/or in the immediate

retrieval performance when learning/immediate testing takes place during the evening vs. in the morning would indicate potential circadian effects and preclude further interpretation about the effect of sleep on consolidation e.g.,

56,57-59. Note that there are studies that include circadian controls (control conditions 3 and 4 in Fig. 1) but find no effects of time of learning or testing

50. In such a design, a beneficial effect of sleep without any time-of-day effect would be demonstrated only if: there is no difference in learning performance in the four conditions; there is no difference in testing performance between the morning-alone and the evening-alone conditions; and there is better retrieval in the evening-morning than in the morning-evening condition.

Another possible solution is to include sleep-deprived wake control groups in evening-morning (12h Sleep-deprived) or evening-evening (24h Sleep-deprived) conditions (see

Figure 1, conditions 5 vs. 6, respectively) and compare their performance with that of an evening-morning (12h Sleep; condition 1) group. In these sleep deprivation controls, learning takes place in the evening and testing takes place either in the morning or in the next evening, with participants staying awake during the night, or during both the night and the following day, respectively. In both cases, testing can take place either after sleep deprivation, with participants being acutely sleep deprived at testing, or testing can be delayed by another 24-48 hours to allow for one or two nights of recovery sleep (condition 7), with the sleep conditions likewise being tested after comparable delays. The advantage of sleep deprivation control designs is that learning and testing take place at the same time of day in the 12h-Sleep and 12h Sleep-deprived groups, thus controlling for potential circadian differences that are an issue with the typical morning-evening (12h Wake; condition 2) controls. The same holds for the comparison of evening-evening groups, where one group could sleep (24h interval including a sleep period), while the other stayed awake (24h Sleep-deprived) in the delay period (see

Figure 1 conditions 8 vs. 6, respectively). Including recovery sleep (condition 7) ensures that participants are not acutely sleep-deprived at testing, which reduces the (negative) impact of sleep deprivation on test performance. However, including recovery sleep comes at the price of extending the retention interval, which may likewise affect test performance through processes of decay, forgetting or memory restructuring. The benefits of both immediate or delayed testing solutions are limited, because acute sleep deprivation introduces confounding influences on test performance, and recovery sleep may exert additional confounds with regard to longer retention intervals and potential compensatory effects of recovery sleep on memory consolidation, or other confounds related to sleep rebound effects. That is, sleep during the recovery night(s) may compensate for the missed opportunity for sleep consolidation during the first night of sleep deprivation, thus masking the original effect on memory consolidation. Only few studies applied such sleep deprivation designs. One

60 examined the role of noradrenaline for sleep-dependent memory consolidation by pharmacologically blocking noradrenaline via clonidine administration in an evening-evening sleep vs. sleep deprivation design without recovery sleep (

Figure 1 conditions 8 vs. 6, respectively). They observed impaired memory retention after clonidine administration compared to placebo in the sleep condition but no difference between clonidine and placebo in the sleep-deprived wake condition, suggesting that noradrenaline supports memory consolidation specifically during sleep but not during wakefulness.

A third possible solution is to focus on the effect of daytime sleep (i.e., napping) on learning and memory performance, as in this case training and testing occur at the same time in the nap and awake groups (

Figure 1 conditions 9 vs. 10, respectively)

61 (see also section 1c). Note, however, that daytime and nighttime sleep might affect memory differently

62, and daytime naps might largely vary across participants with regards to the duration, depth and composition of sleep (e.g., appearance of REM stage in some, but not all participants), which should be taken into account during analysis and interpretation of these studies.

Finally, beyond the inclusion of additional groups/conditions to control for circadian effects, further questionnaires/tasks should also be used to assess subjective sleepiness (e.g., Stanford Sleepiness Scale) and objective vigilance (e.g., Psychomotor Vigilance Test) before and after the encoding and testing sessions. These assessments could provide further useful information about the subjective states and vigilance of participants, and could be included in the analyses as covariates, or extreme values could be used for participant exclusion. It is important to note, however, that questionnaires/tasks with good psychometric properties should be selected for this purpose, and a null effect with these assessments alone (i.e., without the inclusion of control groups/conditions discussed above) should not be used to dismiss an alternative explanation entirely, because null results could be due to low statistical power (see below).

1.3. Controls in overnight studies

Studies investigating the effect of sleep on memory consolidation sometimes compare experimental conditions across sleep intervals only. For example, studies in clinical populations with patients suffering from sleep disorders (e.g., primary insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, sleep-disordered breathing) often compare a pathological group with a control healthy group and often use only an evening-morning sleep condition (

Figure 1, condition 1)

43,63 for reviews, see

64,65.

Importantly, however, if patients show a smaller benefit of the overnight period on performance compared to control participants, one cannot disentangle whether it is caused by the specific effect of that overnight sleep (i.e., state-dependent consolidation) or by a trait-dependent effect of sleep disturbances on memory processes involving not only consolidation, but perhaps also encoding and retrieval or even other cognitive limitations

64,66-68. An additional issue is that pathologies can also influence circadian cycles

69, thus time of peak performance may be shifted in such populations. Many of these issues need to be likewise considered in aging populations, as aging impacts the prevalence of sleep disorders, cognitive performance, daytime functioning, and mnemonic functioning

70,71.

Similarly, studies investigating sleep interventions (e.g., using pharmacological agents or electrical stimulation) typically only compare sleep conditions with vs. without intervention in an evening-morning design (

Figure 1, condition 1). However, with this design, it cannot be ascertained that any observed effects are sleep-specific or whether the intervention exerts general effects that are independent of sleep.

To assess the specificity of sleep-related consolidation and sleep interventions, it is essential to include appropriate control groups/conditions in which participants stay awake for a comparable period and, in the case of intervention studies, also receive the same experimental manipulations as in the sleep groups/conditions. There are two main classes of wake controls in overnight studies: morning-evening (wake) controls (

Figure 1, condition 2), and evening-morning (condition 1) or evening-evening (sleep deprived) controls (condition 6) (see section 1a).

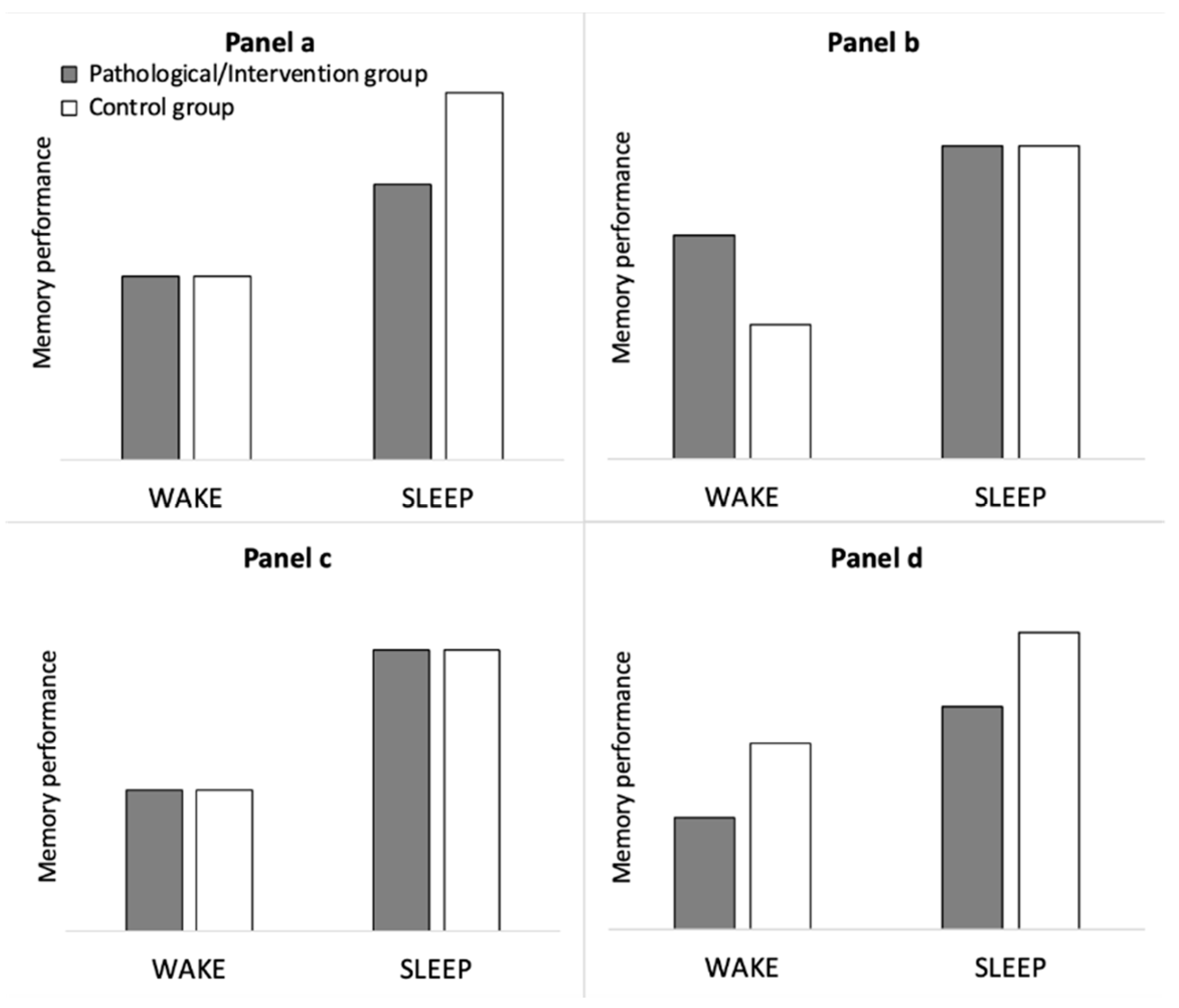

For example, to demonstrate that a pathology (or an intervention) specifically affects sleep-related consolidation, there must be not only differences in test-performance between the pathological (or intervention) group and the control group, but also that similarities (or improvements) in test performance in the wake control condition in both groups. In other words, there should be a group difference in the sleep condition, but no group difference in the wake condition (i.e., a group-by-condition interaction; see

Figure 2, panel a). However, if test performance in the sleep condition is similar in the pathological/intervention group and control group, then one cannot conclude that the pathology/intervention affects sleep-related consolidation processes (i.e., no interaction; Panel c), unless there is also a group difference in the wake condition (i.e., an interaction; Panel b). Finally, if test performance in the pathological/intervention group is different from that in the control group both in the Sleep and in the Wake conditions without a group-by-condition interaction (i.e., no interaction; Panel d), then one would conclude that the pathology or the intervention has a more general effect, possibly influencing other processes (such as encoding or retrieval) but not sleep-related consolidation

per se.

Such a design has been used in a handful of studies only. One study

72 compared the effect of evening-morning (sleep) vs. morning-evening (wake) conditions (

Figure 1, conditions 1 vs. 2) on consolidation of non-declarative/procedural and declarative memory in participants with insomnia and healthy control participants. For procedural memory, similar retention over the morning-evening (wake) interval was observed in both groups (condition 2). However, the healthy control group showed better retention over the evening-morning (sleep) interval (condition 1) than did the insomnia group. This pattern of differences corresponds to

Figure 2A. The authors concluded that insomnia specifically impairs sleep-related consolidation in procedural memory. Since declarative memory retention did not differ significantly between the two groups, either in the wake or in the sleep condition (although it showed a trend towards the same overall pattern as in

Figure 2A), no conclusion about the effect of insomnia on sleep-related consolidation of declarative memory could be drawn in this case.

1.4. Control conditions in napping studies

Napping studies typically compare performance changes following an interval that includes daytime sleep with an interval that includes sustained wake at the same time of day (

Figure 1, conditions 9 vs. 10). Therefore, they allow to control for circadian effects (see section 1a). The duration of naps varies greatly across studies, ranging from 6 minutes

73 and 40-90 minutes

62,74,75 to 3 hours

76-78. The naps in most such studies take place around noon

62,75,79, while others take place in the early morning

80 or at night

74. Split-night designs have also been applied, with 3-hour sleep periods either during the first (SWS-rich) or second (REM-rich) halves of the night

77,81,82.

Importantly, as above, naps differ substantially with respect to the composition of sleep stages and hormonal concentrations, depending on the time of day and the duration of the nap. Moreover, including wake controls at the same time of day and of the same duration does not rule out the possibility that other factors than sleep per se affect memory consolidation. For example, the general concern that reducing external interferences during the post-learning interval may be sufficient to aid off-line consolidation also pertains to nap studies e.g., 15,83.

The length of actual sleep during a nap is also critical. The nap condition may include a significant amount of quiet rest depending on sleep latency. If this is the case, the two conditions of quiet rest and nap may overlap significantly, making comparisons difficult84.

There are several potential ways to control napping studies. First, depending on the aim of the study, the timing and duration of naps must be carefully considered. Attending to these variables allows, for example, comparing naps with and without REM sleep e.g., 61,85.

Second, adding a carefully controlled quiet rest condition (e.g., keeping eyes open to avoid falling asleep; condition 11) helps to distinguish whether sleep is a specific state that actively triggers off-line memory improvement, or a non-specific state that only passively protects memories from interference 47. The benefits of such a design have been recently recognized. Studies using such a design have led to mixed findings, with some studies showing better consolidation in the nap condition than in the quiet rest condition 76,86,87 and others showing that quiet rest produced effects on memory consolidation similar to those observed in nap conditions 88,89, suggesting that sleep per se may not be necessary for consolidation but rather only provides a favorable environment. Observations that memory reactivation occurs not only during sleep but also during quiet rest e.g., 90 using fMRI further highlight the need for such control conditions. Therefore, monitoring the wake (quiet rest) condition with polysomnography is essential to rule out any sleep-like brain activity during the quiet rest interval, as well as to examine whether polysomnographic indicators during wake (quiet rest) are specifically associated with memory consolidation (see also below)84.

Note that a quiet rest condition would also be informative in a classic overnight design (

Figure 1, condition 1) that employs control conditions, such as morning-evening (wake) or evening-morning with sleep deprivation (

Figure 1 conditions 2 vs. 5, respectively). However, this solution is not feasible since it would be extremely difficult to stay in quiet wakefulness for 12 hours in the morning-evening condition and it would be even more difficult (and stressful) to avoid falling asleep in a quiet environment in the evening-morning condition. Therefore, overnight studies typically use an active wake evening-morning (sleep-deprived; condition 5) control condition to control for circadian effects in their design.

Finally, few studies have included both an overnight sleep (condition 1), a daytime nap (condition 9), and a quiet rest (wake; condition 11) condition in a single experimental design to understand the specific effect of sleep on consolidation 91,92. While this approach introduces its own set of challenges (e.g., the architecture of a nap and overnight sleep are not comparable), it can be advantageous as it allows: the direct comparison of the relative benefit of an overnight sleep vs. a nap; a better control for time-of-day effects; and the examination of specific benefits of napping and the minimum amount of sleep necessary to afford a benefit to memory consolidation.

1.5. Intervals between encoding and sleep

The time interval between the learning task and sleep onset (

Figure 1 condition 1) may vary across experiments, conditions and individuals, potentially hindering the assessment of the true effect of sleep on memory consolidation. Although consolidation of procedural memory appears rather insensitive to such effects

28, in declarative memory, the more time that elapses between the end of the learning task and sleep onset, the smaller the sleep-related memory benefit

26. A longer wake interval before sleep onset may hinder the manifestation of the beneficial effect of sleep due to the participant’s involvement in activities that may interfere with recently learned information by re-engaging the same cognitive processes and/or recruiting the same neural networks.

Experiments should control the duration of the interval between memory encoding and bedtime/sleep onset, as well as the participants’ activities during this interval. To minimize interference during this interval, participants should go to bed as soon as possible after memory encoding. Such designs are more feasible when participants sleep in the lab during the experiment. If, however, participants sleep at home after the learning session, then mobile actigraphy or, as less-compelling substitutes, sleep diaries and post-experiment questionnaires, should be employed to assess the duration of this interval and the activities performed. This information then should be appropriately considered in data analysis.

1.6. Baseline measures and feedback

When designing a declarative memory paradigm, a critical question is what procedure to use to ensure that participants encode a sufficient number of items for a later reliable and valid test of retrieval performance. In most sleep-related declarative memory studies that use cued or free recall, a certain learning criterion is defined, for instance 60% of recall success. (Other methods involve restrictions of study time e.g. 73 or of number of trials during encoding e.g., 93). If the learning criterion is not met after the first run of trials, a common strategy is to repeat the whole run, until the learning criterion is met e.g. 94,95. An advantage of this procedure is that all participants encode a sufficient number of items for later retrieval testing. However, the quality of encoding can be significantly different between participants: A participant who met the learning criterion within the very first run studies all items only once and, therefore, encodes them rather weakly. Another participant, who needed several repetitions to meet the criterion, studies all items multiple times. In this latter example, a difference can arise in the strength/quality of encoding of different items: some items may have been successfully encoded already in the first run and further practiced during successive repetitions, while other items may have been encoded only in the final repetition. These differences in repetitions and encoding level could have an enormous impact on later retrieval performance 96-98. This effect deserves even more consideration in studies comparing different populations (e.g., healthy participants vs. patients, or children vs. adults) that presumably learn at a different pace.

Another issue that arises in declarative memory paradigms is that the performance level observed during the last run of encoding (i.e., just when the learning criterion is met) is frequently used as a baseline measurement to evaluate recall performance after the retention interval. However, encoding runs are often designed to give direct feedback, often in the form of providing the correct answer after each item, potentially resulting in further, unmeasured encoding. Therefore, the baseline measurement does not reflect the exact memory state at the end of the learning phase, but rather probably underestimates it in such cases 99-102.

Most researchers investigating sleep-related consolidation of declarative memory choose a learning criterion between 40% and 80% e.g., 103,104, with a 60%-criterion often used for word-pair learning or visuo-spatial learning tasks e.g., 94,95,105-109. Overall, based on these studies, the 60% learning criterion seems to be a reasonable choice to account for possible floor and ceiling effects.

An option to circumvent the use of a predefined learning criterion is the so-called selective reminding procedure 110. All items are presented to the participant during a first study run. Subsequently, a first test run is conducted where all items are tested. In a second study run, only those items that were not recalled correctly during the first test run are presented. These runs continue until all items are remembered correctly once. This procedure enables all participants to encode the same number of items while no item is ‘over-learned’ for examples, see 111,112,113. This procedure could be used to reach 100% for baseline encoding level in all participants. One limitation of such approach (i.e., 100% learning criterion) is, however, that it is only suitable for those memory studies where a loss in declarative memory is expected over the retention interval. In other cases, using the selective reminding procedure with a lower predefined learning criterion (e.g., 60%) could ensure similar encoding strength/quality across participants (no over-learned items), while avoiding potential floor and ceiling effects.

Additionally, a test run of all items, without any corrective feedback, could be introduced immediately after the learning criterion is met, to provide a more precise measure of the baseline. However, test runs can also boost learning and subsequent consolidation even if no feedback is given—a phenomenon called ‘test-enhanced learning’ 114,115.

2. Task complexity

A significant difficulty in sleep and memory research, and in cognitive neuroscience and psychology in general, is that practically every task involves several cognitive processes e.g., 116,117. The learning/memory scores that are used to assess behavioral performances typically reflect a mixture of these cognitive processes 118. For example, even a simple perceptual-motor learning task requires at least the processing of perceptual stimuli, acquisition of their serial order and/or transitional probabilities, perceptual-motor coordination, and selective attention. As learning progresses (i.e., as the involved neurocognitive system is being fine-tuned to the task), these processes could improve at different paces and, therefore, could contribute to the behavioral performance at the end of the learning session to varying degrees. Importantly, consolidation can differentially affect processes involved in the task e.g., 19,28,119,120, and this problem could be even further exacerbated by individual differences in the contribution of each process to behavioral performance.

There are not only different types of learning and cognitive processes but also different types of retrieval processes that may determine whether beneficial effects of sleep on memory consolidation are detected or not. Specifically, declarative memory paradigms most frequently probe recall (the ability to retrieve a stimulus from memory with or without a cue) , and recognition (the ability to decide whether a given stimulus has been previously encountered). Some evidence suggests that recall is more sensitive to sleep effects than recognition, possibly because sleep facilitates the integration of new memories into pre-existing knowledge networks, thereby increasing potential access routes for recall 12.

Differences in retrieval may be evident for procedural memory as well. For example, tasks may tap into explicit (i.e., conscious) vs. implicit (i.e., unconscious) aspects of the acquired knowledge to varying degrees e.g., 121,122. This could potentially lead to contradictory findings across studies and mask the differential effect of sleep on the consolidation of different aspects of knowledge.

Another factor to consider is that different memory systems such as declarative and procedural memory are thought to interact with each other during learning and possibly also during consolidation 123. However, to optimize use of resources, researchers sometimes include memory tasks tapping into different memory systems (e.g., a non-declarative/procedural and a declarative memory task) in a given experiment, which could cause interference in the consolidation of individual memories and alter the observed effects of post-learning sleep and their interpretation. For instance, it has been shown that acquiring procedural memories just after a declarative memory task was affected by participants’ memory performance in the latter and led to differences in consolidation over the wake vs. sleep conditions 124.

Since there are no process-pure learning/memory tasks, attention should be paid to the specific cognitive processes that are involved in a particular task. We recommend using tasks and designs that could help disentangle these different cognitive processes, and examine whether they are differentially affected by sleep. For example, in declarative memory tasks, different aspects of retrieval (free recall, cued recall, recognition) should be systematically compared within the same experimental design to examine how they can reveal (potentially different) sleep effects. These effects may also vary depending on the type of information to be encoded, for example, paired-associates learning 78,125, word-list learning 126,127, emotional picture learning 62,128 and object-location memory 109,129, suggesting that they involve at least partially distinct cognitive processes.

To better understand the differential effect of sleep on aspects of memory, contrasting the encoding/consolidation of different types of information within the same experimental design is warranted. In procedural learning/memory, for instance, research has disentangled and contrasted allocentric vs. egocentric representations 40, perceptual vs. motor components of learning 57, transition vs. ordinal representations 130, and acquisition of statistical vs. sequential regularities 89, and showed differential effects of sleep in some of these aspects 118,130,131.

Furthermore, to minimize the potential interactions between different memory systems, which could confound the identification of sleep effects, it may be beneficial to administer tasks tapping into different memory systems using a between-participant design. If, however, a within-participant design is chosen, the order of task administration should be counterbalanced across participants and included in data analysis as a separate factor.

3. Fatigue effect in repetitive tasks

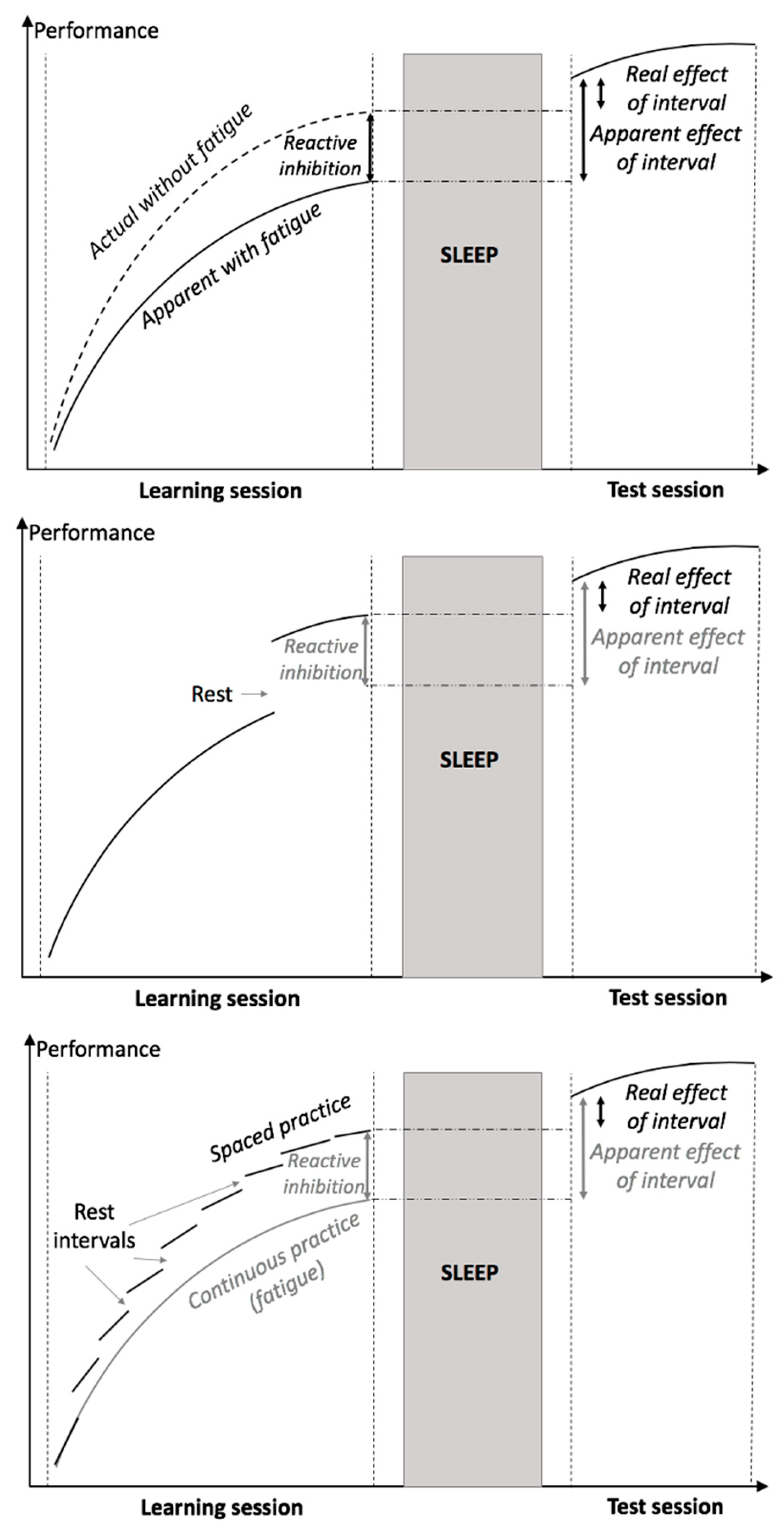

Some studies, particularly those investigating non-declarative/procedural learning, use tasks that involve continuous practice with a series of repetitions of the same action, such as pressing keys 132. Learning is measured as the improvement in accuracy or in reaction times as the task progresses. Usually, the performance at the end of the training session serves as a baseline to measure improvement at the test session that takes place after an interval involving sleep or wakefulness. Yet, after a certain amount of time spent performing the task, the participant’s observed improvement is less marked, which can be interpreted as a reactive inhibition effect that reflects the build-up of fatigue over the trials e.g., 32,133. This effect often results in smaller improvement or even a decrease in performance as the task progresses. Thus, the measured performance after longer/extended practice is not representative of the level of expertise gained in the task and, therefore, comparing the performance at the test session with that of the end of the training session may lead to illusory sleep-related improvement and may also bias the quantification of the sleep benefit.

Figure 3a illustrates this issue, which can be even further exacerbated by averaging performance measures across multiple trials, instead of using trial-by-trial analysis. In several cases, after eliminating the reactive inhibition effect by releasing the presumed fatigue, the sleep-related off-line improvement was no longer observed e.g.,

134,135. Rather than an actual performance improvement, after elimination of the reactive inhibition effect, the benefit of sleep was expressed as a stabilization of performance

134,136. Although this issue is primarily relevant in procedural learning studies, reactive inhibition might also affect performance in declarative memory studies, particularly if they include repetitive presentations of the same items or a long period of memorization

127.

Resting for a few minutes after the training session appears to be sufficient to ‘wash out’ the effect of reactive inhibition on performance. Measuring performance after a break is therefore a more appropriate baseline to assess subsequent off-line consolidation e.g.,

89,133.

Figure 3b illustrates this solution. Moreover, use of short (e.g., 10 s) performance intervals between longer (e.g., 30 s) rest intervals during the training session (often termed spaced practice) can also impede the accumulation of reactive inhibition compared to experimental designs that use massed practice in which there are longer task intervals e.g.,

133,134,137.

Figure 3c illustrates this solution.

Other solutions to reactive inhibition involve the use of curve-fitting methods and computational modelling in data analysis. Here we highlight two curve-fitting methods. First, a function-based model (e.g., a power function for reaction time improvement) can be fitted to the training session data and used to predict future performance (under the null hypothesis that the delay between training and test sessions has no effect on performance). This method enables a comparison between the predicted (under H0) and the actual outcomes measured during the test session. This way, one avoids averaging over data points to compute a pre-post gain—a procedure that may yield illusory off-line performance gains if performance improves between the end of the training session and the beginning of the test session, wherein the data averaging is done32. As a second and more formal approach, a function can be fitted to the training and test session data and then a continuity test can be used to infer whether the performance is a simple continuation of that function from the training session to the test session, or whether there is an abrupt change between the sessions (see details on these approaches in 32).

Using computational models on trial-by-trial data can also help overcome the issue of fatigue by directly including reactive inhibition as a separate parameter in the model. For instance, in a probabilistic sequence learning task, one study 138 used such a model to enable the estimation of the actual magnitude of learning, independent of the effect of reactive inhibition. Such models can be used in a wide range of learning and memory tasks, including finger tapping and other sequence learning tasks.

4. Data analysis practices

The studies of sleep and memory suffer from similar problems as the whole field of psychology and neuroscience discussed in recent years as the ‘replication crisis’ 139-141, and thus could similarly benefit from an update in practices that are currently evolving in the scientific community in general (see e.g., 142 about publication bias in sleep and motor sequence learning literature).

4.1. Sample size and result interpretation

Studies of sleep-related consolidation have typically used samples with 12-20 participants per group e.g., 26,142,143, or in some cases even smaller samples e.g., 144. This may be due to complicated or demanding study designs, difficulties recruiting clinical populations, and/or drop-outs of participants (i.e., experimental attrition). Moreover, sample sizes have usually not been determined by a priori power analysis based on expected effect sizes. Importantly, small sample sizes could result in low statistical power, potentially increasing Type 2 errors (i.e., not detecting an existing effect), as well as non-replicable, spurious findings. By contrast, a common but questionable practice of collecting additional data until a significant effect is reached could increase Type 1 errors (i.e., detecting an effect that does not exist), again, leading to non-replicable findings.

Another issue arises from the interpretation of non-significant findings. For example, non-significant effects could be observed in pre-sleep vs. post-sleep comparisons when consolidation results in stabilization of the acquired knowledge without forgetting or off-line performance improvement (i.e., no performance change). The conclusions that sleep promotes stabilization of the acquired knowledge or has no effect on some aspects of memory consolidation compared to wakefulness cannot be drawn by showing non-significant results in classical statistical approaches (e.g., frequentist t-test, ANOVA, correlation, etc.).

Solutions to this issue can focus on using a priori power analyses before data collection, as well as Bayesian statistical approaches during and after data collection. It has long been recommended in guidelines (e.g., published by the American Psychological Association145) that experimenters should determine the sample size before starting the experiment by computing power analyses based on the expected effect size estimated or found in previous studies that observed similar effects.

For particularly costly experimental protocols, Bayesian statistical analyses 146-149 computed in the course of data collection can be used to determine whether there is enough evidence in favor of a given a priori defined effect so that one can stop data collection 150,151. Bayesian analyses, in particular the Bayes Factors, are rarely reported in the field of sleep-related memory consolidation (although see 152 for an exception) whereas they are increasingly reported in other areas of psychology and neuroscience. The Bayes Factor indicates an odds ratio of relative probabilities in favor of the null hypothesis vs. in favor of the alternative hypothesis153,154. Bayesian statistics thus allow a more fine-grained quantitative evaluation of the effect of sleep on memory consolidation. Additionally, effect size measures should always be reported to provide an estimate of the relevance of the observed effect. Effect sizes can also be indicative of the true effect in cases of non-significant results with small samples and potential Type 2 errors155.

4.2. Spurious correlations

Beyond the comparison of groups or conditions, conclusions about the effect of sleep are often based on correlations between behavioral performance and sleep polysomnographic parameters e.g., 89,156 (see also the next subsection). However, suboptimal statistical practices can lead to spurious correlations being identified e.g., 32,33,44,157. Specifically, polysomnography provides a wealth of parameter combinations, including different spindle parameters (absolute/relative number, amplitude, length, activity) at different frequencies (slow/fast) at different scalp regions/electrodes during different sleep stages and different fractions of the night. The resulting massive ‘researcher’s degrees of freedom’ easily allow for (intentional or unintentional) p-hacking.

Small sample sizes are a further source of spurious correlations. When sufficiently large sample sizes are used, these correlations may be greatly reduced 157 or even disappear. For example, between sleep parameters and episodic memory consolidation—an area that has received much attention in the past decades of sleep and memory research—one study 158 did not find any significant correlation in a large sample of 929 participants.

The correlations to be computed should be planned a priori (see also Box 1) and corrected for multiple comparisons to avoid increases in Type 1 errors 159. Non-significant planned correlations should also be systematically reported 160. If no relationship is expected between certain sleep parameters and behavioral performance, Bayesian approaches should be used to draw conclusions in favor of the null hypothesis instead of (or in addition to) reporting non-significant p-values (see previous subsection).

4.3. Individual differences

Certain features of sleep (e.g., sleep spindles) appear to be highly correlated with trait-like individual differences in cognitive abilities. Particularly strong relationships have been identified for cognitive abilities related to reasoning, problem solving, the ability to identify complex patterns and relationships, and the use of logic (i.e., ‘fluid intelligence’) 161-165. Since these cognitive abilities are associated with certain features of sleep and with memory functions, they may confound the associations revealed between sleep and memory consolidation. Therefore, when the specific effect of sleep on memory consolidation is tested, associations between sleep (e.g., spindles) and these cognitive abilities (e.g., intelligence) should be controlled for.

The problem of disentangling individual differences in the associations between sleep and general cognitive abilities from the associations between sleep and memory can be addressed by at least two ways. First, one can employ neurocognitive assessments (e.g., intelligence testing) and include these scores as covariates to statistically control for possible confounding effects when testing the specific associations between sleep and memory consolidation. Second, a comparable baseline night of sleep together with an appropriate control task can be included in the study design. This control task should be comparable to the experimental task without engaging the specific targeted processes that are the focus of sleep-related memory consolidation. Comparing the two experimental conditions can reveal the specific effect of sleep on the memory process of interest.

5. Conclusion

In this article, we have highlighted four sets of critical methodological issues that impede research in the field of sleep and memory, and offered solutions to avoid or address them (

Table 1). It is important to note that all scientific disciplines suffer from similar issues. Research on the relationship between sleep and memory is still quite fortunate in this respect. However, there is a constant need to fine-tune the methodology. We believe that implementing the solutions presented here will lead to more reliable results and significantly advance our understanding of the complex relationship between sleep and memory. Since some of the issues described here (such as those related to fatigue effects, task complexity, and data analysis practices) are relevant not only in sleep and memory research but also in other fields of psychology and neuroscience, applying these solutions where appropriate could benefit the broader scientific community as well. Implementing these solutions is undoubtedly challenging: it can increase the duration and cost of research. However, adopting the practices above will help advance the field in the long term.

Box 1. Open science practices.

Other fields of neuroscience using techniques such as fMRI have engaged in open science initiatives by, for example, depositing raw data in open-access databases (e.g., OpenfMRI; 166), which have recently been extended to other neuroimaging and electrophysiological methods such as EEG as well (OpenNEURO; 167). However, sleep and memory research is lagging behind with respect to this practice. Research transparency is further hindered by the lack of pre-registration of the studies on sleep and memory.

5.1. Data deposition

Making research data publicly available enables the re-analysis of old data when new analysis techniques and/or new theories are developed. For example, there are at least two different types of REM microstates (tonic vs. phasic), each with different characteristics, described comprehensively recently 168,169. Access to previous sleep EEG data would enable testing of the role of REM microstructure in memory consolidation in previous datasets. Publicly available sleep EEG and behavioral data could also provide solutions for at least some of the issues discussed above by, for example, enabling data re-analysis to evaluate evidence for potentially non-significant results, and could resolve at least some of the previous issues of spurious results. Such open databases could also support reliable synthesis of the data through meta-analyses with larger sample sizes.

To maximize the benefits of previous research in the scientific community, we recommend that sleep researchers engage in open science 170 and make data publicly available. There are several online open repositories available for such purposes, such as Open Science Framework171, OpenNeuro.org167, Scientific Data or sleepdata.org). Developing a specific open database for sleep research with EEG, polysomnographic and behavioral data would further benefit this field.

5.2. Pre-registration

Another way of increasing transparency of research is to pre-register studies before data collection 172,173. Pre-registration includes the specification of the research question, experimental design, participant population, sample size as well as planned analysis methods. Pre-registration is already the gold standard in many fields of research, including for clinical trials in medical research174,175. The neuroscience and psychology fields increasingly recognize the importance of pre-registration as well. Yet, this option has been largely neglected in sleep and memory research so far.

Studies can be pre-registered in different ways. One option is pre-registration in independent online registries like the Open Science Framework or ClinicalTrials.gov. In these registries, researchers provide a detailed description of their planned study that can be accessed by other researchers as well as journal editors and reviewers to determine whether the pre-specified plan was followed adequately. Another option is to write a registered report, which is a novel publication type offered by an increasing number of journals (e.g., Plos Biology, eLife, eNeuro, Nature Human Behaviour, Cortex). A registered report usually undergoes two stages of peer review, first before data collection to determine the appropriateness of the research plan and methodology, and then after data collection covering the full research report including the results. If the first round of peer review is successful, the authors are typically offered ‘in principle acceptance’ by the journal, allowing the results to be published irrespective of the actual findings.

Both procedures, pre-registration in online registries and registered reports, increase the quality of research by reducing inappropriate data analysis practices, including p-hacking, HARKing (hypothesizing after the results are known), and the application of unplanned statistical tests174,176. Thus, pre-registration can promote the implementation of solutions to Pitfall 4 discussed above (see e.g., sections 4a and 4b). Additionally, registered reports could also reduce the file-drawer problem because the study, irrespective of finding significant or non-significant results, could be published in the target journal.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Hungary’s National Brain Research Program (project 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00002); the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (NKFIH-OTKA K 128016, PI: D. N.; NKFIH-OTKA PD 124148, PI: K.J.; NKFI FK 128100, PI: P.S.); Janos Bolyai Research Fellowship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (to K. J.); IDEXLYON Fellowship (to D.N); French National Agency for Research (ANR, grant n°ANR-15-CE33-0003, PI: S.M.). The authors thank K. Schipper and T. Vekony for their help and comments on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Palagini, L. & Rosenlicht, N. Sleep, dreaming, and mental health: a review of historical and neurobiological perspectives. Sleep Med. Rev. 15, 179-186 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Simor, P., Sifuentes-Ortega, R. & Peigneux, P. ESRS European sleep medicine textbook: chapter: A. 5. Sleep and psychology (cognitive and emotional processes). (2021).

- Walker, M. P. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1156, 168-197 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Shochat, T. Impact of lifestyle and technology developments on sleep. Nature and science of sleep 4, 19 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Bixler, E. Sleep and society: an epidemiological perspective. Sleep Med. 10, S3-S6 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, L. et al. Past, present, and future: trends in sleep duration and implications for public health. Sleep health 3, 317-323 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Hale, L. & Guan, S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med. Rev. 21, 50-58 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, S. & Rasch, B. Differential effects of non-REM and REM sleep on memory consolidation? Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 14, 430 (2014).

- Antony, J. W., Schönauer, M., Staresina, B. P. & Cairney, S. A. Sleep spindles and memory reprocessing. Trends Neurosci. 42, 1-3 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Boyce, R., Williams, S. & Adamantidis, A. REM sleep and memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 44, 167-177 (2017).

- Diekelmann, S. & Born, J. The memory function of sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 114-126 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Diekelmann, S., Wilhelm, I. & Born, J. The whats and whens of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Sleep Med. Rev. 13, 309-321 (2009).

- Feld, G. B. & Born, J. Sculpting memory during sleep: concurrent consolidation and forgetting. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 44, 20-27 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. A. & Durrant, S. J. Overlapping memory replay during sleep builds cognitive schemata. Trends in cognitive sciences 15, 343-351 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Mednick, S. C., Cai, D. J., Shuman, T., Anagnostaras, S. & Wixted, J. T. An opportunistic theory of cellular and systems consolidation. Trends Neurosci. 34, 504-514 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Saletin, J. M. & Walker, M. P. Nocturnal mnemonics: sleep and hippocampal memory processing. Front. Neurol. 3, 59 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D. J. Memory: an overview, with emphasis on developmental, interpersonal, and neurobiological aspects. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 40, 997-1011 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Stickgold, R. & Walker, M. P. Memory consolidation and reconsolidation: what is the role of sleep? Trends Neurosci. 28, 408-415 (2005).

- Stickgold, R. & Walker, M. P. Sleep-dependent memory triage: Evolving generalization through selective processing. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 139-145 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med. Rev. 10, 49-62, (2006). [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Sleep and the price of plasticity: from synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron 81, 12-34 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. P. A refined model of sleep and the time course of memory formation. Behav. Brain Sci. 28, 51-104 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Schönauer, M., Grätsch, M. & Gais, S. Evidence for two distinct sleep-related long-term memory consolidation processes. Cortex 63, 68-78 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, J. W., Ghazanfar, A. A., Gomez-Marin, A., MacIver, M. A. & Poeppel, D. Neuroscience needs behavior: correcting a reductionist bias. Neuron 93, 480-490 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Niv, Y. The primacy of behavioral research for understanding the brain. Behav. Neurosci. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gais, S., Lucas, B. & Born, J. Sleep after learning aids memory recall. Learn. Mem. 13, 259-262 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. P., Brakefield, T., Hobson, J. A. & Stickgold, R. Dissociable stages of human memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Nature 425, 616-620 (2003). [CrossRef]

- King, B. R., Hoedlmoser, K., Hirschauer, F., Dolfen, N. & Albouy, G. Sleeping on the motor engram: the multifaceted nature of sleep-related motor memory consolidation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 80, 1-22 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Rasch, B. & Born, J. About sleep's role in memory. Physiol. Rev. 93, 681-766, (2013). [CrossRef]

- Born, J. & Wilhelm, I. System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychol. Res. 76, 192-203 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Vorster, A. P. & Born, J. Sleep and memory in mammals, birds and invertebrates. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 50, 103-119 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Pan, S. C. & Rickard, T. C. Sleep and motor learning: is there room for consolidation? Psychol. Bull. 141, 812 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Mantua, J. Sleep Physiology Correlations and Human Memory Consolidation: Where Do We Go From Here? Sleep 41, zsx204 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Vertes, R. P. & Siegel, J. M. Time for the sleep community to take a critical look at the purported role of sleep in memory processing. Sleep 28, 1228-1229 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Dastgheib, M., Kulanayagam, A. & Dringenberg, H. C. Is the role of sleep in memory consolidation overrated? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 104799 (2022).

- Cordi, M. J. & Rasch, B. How robust are sleep-mediated memory benefits? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 67, 1-7 (2021).

- Voderholzer, U. et al. Sleep restriction over several days does not affect long-term recall of declarative and procedural memories in adolescents. Sleep Med. 12, 170-178 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Robertson, E. M., Pascual-Leone, A. & Press, D. Z. Awareness modifies the skill-learning benefits of sleep. Curr. Biol. 14, 208-212, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Song, S., Howard, J. H., Jr. & Howard, D. V. Sleep does not benefit probabilistic motor sequence learning. J. Neurosci. 27, 12475-12483, (2007). [CrossRef]

- Viczko, J., Sergeeva, V., Ray, L. B., Owen, A. M. & Fogel, S. M. Does sleep facilitate the consolidation of allocentric or egocentric representations of implicitly learned visual-motor sequence learning? Learn. Mem. 25, 67-77 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. K., Baran, B., Pace-Schott, E. F., Ivry, R. B. & Spencer, R. Sleep modulates word-pair learning but not motor sequence learning in healthy older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 991-100 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, D. et al. Sleep has no critical role in implicit motor sequence learning in young and old adults. Exp. Brain Res. 201, 351-358, (2010). [CrossRef]

- Csabi, E., Varszegi-Schulz, M., Janacsek, K., Malecek, N. & Nemeth, D. The consolidation of implicit sequence memory in obstructive sleep apnea. PLoS One 9, e109010 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ujma, P. P. Meta-analytic evidence suggests no correlation between sleep spindles and memory. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. D. et al. The role of sleep in false memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem 92, 327-334 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Peigneux, P. & Smith, C. Memory processing in relation to sleep. Principles and practice of sleep medicine 5 (2010).

- Ellenbogen, J. M., Payne, J. D. & Stickgold, R. The role of sleep in declarative memory consolidation: passive, permissive, active or none? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 716-722 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C., Collette, F., Cajochen, C. & Peigneux, P. A time to think: circadian rhythms in human cognition. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 24, 755-789 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Barner, C., Schmid, S. R. & Diekelmann, S. Time-of-day effects on prospective memory. Behav. Brain Res. 376, 112179 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Scullin, M. K. & McDaniel, M. A. Remembering to execute a goal: sleep on it! Psychol. Sci. 21, 1028-1035 (2010).

- Keisler, A., Ashe, J. & Willingham, D. T. Time of day accounts for overnight improvement in sequence learning. Learn. Mem. 14, 669-672 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Taillard, J., Gronfier, C., Bioulac, S., Philip, P. & Sagaspe, P. (s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published …, 2021).

- Dresler, M. et al. Neuroscience-driven discovery and development of sleep therapeutics. Pharmacology & therapeutics 141, 300-334 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Genzel, L. & Robertson, E. M. To Replay, Perchance to Consolidate. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002285. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M. et al. The relative impact of sleep and circadian drive on motor skill acquisition and memory consolidation. Sleep 40, zsx036 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Fenn, K. M., Nusbaum, H. C. & Margoliash, D. Consolidation during sleep of perceptual learning of spoken language. Nature 425, 614-616 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Hallgato, E., Győri-Dani, D., Pekár, J., Janacsek, K. & Nemeth, D. The differential consolidation of perceptual and motor learning in skill acquisition. Cortex 49, 1073-1081 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Talamini, L. M., Nieuwenhuis, I. L., Takashima, A. & Jensen, O. Sleep directly following learning benefits consolidation of spatial associative memory. Learn. Mem. 15, 233-237 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M., McKinley, S. & Stickgold, R. Sleep optimizes motor skill in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59, 603-609 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Gais, S., Rasch, B., Dahmen, J. C., Sara, S. & Born, J. The memory function of noradrenergic activity in non-REM sleep. J Cogn Neurosci 23, 2582-2592. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Mednick, S. C., Nakayama, K. & Stickgold, R. Sleep-dependent learning: a nap is as good as a night. Nat Neurosci 6, 697-698. (2003). [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. D. et al. Napping and the selective consolidation of negative aspects of scenes. Emotion 15, 176 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J. et al. Impaired declarative memory consolidation during sleep in patients with primary insomnia: influence of sleep architecture and nocturnal cortisol release. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 1324-1330 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, S. et al. Role of normal sleep and sleep apnea in human memory processing. Nature and science of sleep 10, 255 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Cellini, N. Memory consolidation in sleep disorders. Sleep Med. Rev. 35, 101-112 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A. & Bucks, R. S. Memory and obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Sleep 36, 203-220 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Csábi, E., Benedek, P., Janacsek, K., Katona, G. & Nemeth, D. Sleep disorder in childhood impairs declarative but not nondeclarative forms of learning. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 35, 677-685 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, I. et al. Sleep apnoea and the brain: a complex relationship. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 3, 404-414 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Wulff, K., Gatti, S., Wettstein, J. G. & Foster, R. G. Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 589-599 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Vitiello, M. V. & Gooneratne, N. S. Sleep in normal aging. Sleep Med. Clin. 13, 1-11 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Mander, B. A., Winer, J. R. & Walker, M. P. Sleep and human aging. Neuron 94, 19-36 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Nissen, C. et al. Sleep-related memory consolidation in primary insomnia. J. Sleep Res. 20, 129-136 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lahl, O., Wispel, C., Willigens, B. & Pietrowsky, R. An ultra short episode of sleep is sufficient to promote declarative memory performance. J Sleep Res 17, 3-10. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Diekelmann, S., Biggel, S., Rasch, B. & Born, J. Offline consolidation of memory varies with time in slow wave sleep and can be accelerated by cuing memory reactivations. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 98, 103-111 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Nishida, M. & Walker, M. P. Daytime naps, motor memory consolidation and regionally specific sleep spindles. PLoS One 2, e341 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Schönauer, M., Geisler, T. & Gais, S. Strengthening procedural memories by reactivation in sleep. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26, 143-153 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Gais, S., Plihal, W., Wagner, U. & Born, J. Early sleep triggers memory for early visual discrimination skills. Nat Neurosci 3, 1335-1339. (2000). [CrossRef]

- Plihal, W. & Born, J. Effects of early and late nocturnal sleep on declarative and procedural memory. J Cogn Neurosci 9, 534-547. (1997). [CrossRef]

- Mednick, S. C., Mednick, S. C., Cai, D. J., Kanady, J. & Drummond, S. P. A. Comparing the benefits of caffeine, naps and placebo on verbal, motor and perceptual memory. Behav. Brain Res. 193, 79 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Sopp, M. R., Michael, T. & Mecklinger, A. Effects of early morning nap sleep on associative memory for neutral and emotional stimuli. Brain Res 1698, 29-42. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Plihal, W., Weaver, S., Molle, M., Fehm, H. L. & Born, J. Sensory processing during early and late nocturnal sleep. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 99, 247-256. (1996). [CrossRef]

- Yaroush, R., Sullivan, M. J. & Ekstrand, B. R. Effect of sleep on memory. II. Differential effect of the first and second half of the night. J Exp Psychol 88, 361-366. (1971). [CrossRef]

- Wamsley, E. J. Memory consolidation during waking rest. Trends in cognitive sciences 23, 171-173 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J. N., Wong, K. F., Raghunath, B. L., Look, C. & Chee, M. W. The long-term memory benefits of a daytime nap compared with cramming. Sleep 42, zsy207 (2019). [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, E. A., Duggan, K. A. & Mednick, S. C. REM sleep rescues learning from interference. Neurobiol Learn Mem 122, 51-62. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Piosczyk, H. et al. The effect of sleep-specific brain activity versus reduced stimulus interference on declarative memory consolidation. J. Sleep Res. 22, 406-413 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Schichl, M., Ziberi, M., Lahl, O. & Pietrowsky, R. The influence of midday naps and relaxation-hypnosis on declarative and procedural memory performance. Sleep and Hypnosis 13, 7-14 (2011).

- Mednick, S. C., Makovski, T., Cai, D. & Jiang, Y. V. Sleep and rest facilitate implicit memory in a visual search task. Vision Res. 49, 2557-2565 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Simor, P. et al. Deconstructing procedural memory: Different learning trajectories and consolidation of sequence and statistical learning. Front. Psychol. 9, 2708 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Schapiro, A. C., McDevitt, E. A., Rogers, T. T., Mednick, S. C. & Norman, K. A. Human hippocampal replay during rest prioritizes weakly learned information and predicts memory performance. Nature communications 9, 3920 (2018). [CrossRef]

- den Berg van, N. H. et al. Sleep Enhances Consolidation of Memory Traces for Complex Problem-Solving Skills. Cereb. Cortex, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, N. et al. Sleep preferentially enhances memory for a cognitive strategy but not the implicit motor skills used to acquire it. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 161, 135-142 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Mikutta, C. et al. Phase-amplitude coupling of sleep slow oscillatory and spindle activity correlates with overnight memory consolidation. J. Sleep Res.. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cordi, M. J., Diekelmann, S., Born, J. & Rasch, B. No effect of odor-induced memory reactivation during REM sleep on declarative memory stability. Frontiers in systems neuroscience 8, 157. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Prehn-Kristensen, A. et al. Transcranial Oscillatory Direct Current Stimulation During Sleep Improves Declarative Memory Consolidation in Children With Attention-deficit/hyperactivity Disorder to a Level Comparable to Healthy Controls. Brain stimulation 7, 793-799. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Xue, G. et al. Greater neural pattern similarity across repetitions is associated with better memory. Science 330, 97-101. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Young, D. R. & Bellezza, F. S. Encoding variability, memory organization, and the repetition effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 8, 545-559 (1982).

- Ebbinghaus, H. Memory: a contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences 20, 155-156. (2013). [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. C. & McDermott, K. B. The testing effect in recognition memory: a dual process account. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 33, 431-437. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Soderstrom, N. C., Kerr, T. K. & Bjork, R. A. The Critical Importance of Retrieval--and Spacing--for Learning. Psychol Sci 27, 223-230 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J. D. & Roediger, H. L., 3rd. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science 319, 966-968. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Wiklund-Hornqvist, C., Jonsson, B. & Nyberg, L. Strengthening concept learning by repeated testing. Scand. J. Psychol. 55, 10-16. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Klinzing, J. G., Rasch, B., Born, J. & Diekelmann, S. Sleep's role in the reconsolidation of declarative memories. Neurobiol Learn Mem 136, 166-173. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Fowler, M. J., Sullivan, M. J. & Ekstrand, B. R. Sleep and memory. Science 179, 302-304. (1973). [CrossRef]

- Fenn, K. M. & Hambrick, D. Z. Individual differences in working memory capacity predict sleep-dependent memory consolidation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141, 404-410. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, I., Diekelmann, S. & Born, J. Sleep in children improves memory performance on declarative but not procedural tasks. Learn Mem 15, 373-377 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L., Mölle, M., Hallschmid, M. & Born, J. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation during Sleep Improves Declarative Memory. J. Neurosci. 24, 9985-9992. (2004). [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. D. et al. Memory for semantically related and unrelated declarative information: the benefit of sleep, the cost of wake. PLoS One 7, e33079. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Rasch, B., Buchel, C., Gais, S. & Born, J. Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science 315, 1426-1429 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Buschke, H. Selective reminding for analysis of memory and learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 12, 543-550 (1973). [CrossRef]

- Quan, S. F., Budhiraja, R. & Kushida, C. A. Associations Between Sleep Quality, Sleep Architecture and Sleep Disordered Breathing and Memory After Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea in the Apnea Positive Pressure Long-term Efficacy Study (APPLES). Sleep science (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 11, 231-238. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Uguccioni, G. et al. Sleep-related declarative memory consolidation and verbal replay during sleep talking in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. PLoS One 8, e83352. (2013). [CrossRef]

- Mazza, S. et al. Relearn Faster and Retain Longer. Psychol Sci 27, 1321-1330. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Roediger III, H. L. & Karpicke, J. D. The power of testing: basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 181-210 (2006). [CrossRef]

- McDermott, K. B. Practicing Retrieval Facilitates Learning. Annu Rev Psychol 72, 609-633, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, L. L. A process dissociation framework: Separating automatic from intentional uses of memory. JMemL 30, 513-541 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Sigman, M. & Dehaene, S. Parsing a cognitive task: a characterization of the mind's bottleneck. PLoS Biol. 3, e37 (2005).

- Cohen, D. A., Pascual-Leone, A., Press, D. Z. & Robertson, E. M. Off-line learning of motor skill memory: A double dissociation of goal and movement. PNAS 102, 18237-18241 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Conte, F. & Ficca, G. Caveats on psychological models of sleep and memory: a compass in an overgrown scenario. Sleep Med. Rev. 17, 105-121 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Stickgold, R. Parsing the role of sleep in memory processing. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 847-853 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Schendan, H. E., Searl, M., Melrose, R. & Stern, C. An FMRI study of the role of the medial temporal lobe in implicit and explicit sequence learning. Neuron 37, 1013-1025 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S., Drosopoulos, S., Tsen, J. & Born, J. Implicit Learning-Explicit Knowing: A Role for Sleep in Memory System Interaction. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 311 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, M., Toader, A. C., Wassermann, E. M. & Voss, J. L. Competitive and cooperative interactions between medial temporal and striatal learning systems. Neuropsychologia 136, 107257, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. M. & Robertson, E. M. Off-line processing: Reciprocal interactions between declarative and procedural memories. J. Neurosci. 27, 10468-10475 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Feld, G. B., Weis, P. P. & Born, J. The Limited Capacity of Sleep-Dependent Memory Consolidation. Front Psychol 7, 1368, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Diekelmann, S., Born, J. & Wagner, U. Sleep enhances false memories depending on general memory performance. Behav Brain Res 208, 425-429, (2010). [CrossRef]

- Abel, M. & Bauml, K. H. Retrieval-induced forgetting, delay, and sleep. Memory 20, 420-428, (2012). [CrossRef]

- Cairney, S. A., Durrant, S. J., Power, R. & Lewis, P. A. Complementary roles of slow-wave sleep and rapid eye movement sleep in emotional memory consolidation. Cereb Cortex 25, 1565-1575, (2015). [CrossRef]

- Rudoy, J. D., Voss, J. L., Westerberg, C. E. & Paller, K. A. Strengthening individual memories by reactivating them during sleep. Science 326, 1079-1079 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Song, S. & Cohen, L. G. Practice and sleep form different aspects of skill. Nature communications 5, 3407 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Albouy, G. et al. Daytime sleep enhances consolidation of the spatial but not motoric representation of motor sequence memory. PLoS One 8, e52805 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Nissen, M. J. & Bullemer, P. Attentional requirements of learning: Evidence from performance measures. Cogn. Psychol. 19, 1-32 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Brawn, T. P., Fenn, K. M., Nusbaum, H. C. & Margoliash, D. Consolidating the effects of waking and sleep on motor-sequence learning. The Journal of neuroscience 30, 13977-13982 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Rickard, T. C., Cai, D. J., Rieth, C. A., Jones, J. & Ard, M. C. Sleep does not enhance motor sequence learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition; Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 34, 834 (2008).

- Cai, D. J. & Rickard, T. C. Reconsidering the role of sleep for motor memory. Behav. Neurosci. 123, 1153 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Nettersheim, A., Hallschmid, M., Born, J. & Diekelmann, S. The role of sleep in motor sequence consolidation: stabilization rather than enhancement. J. Neurosci. 35, 6696-6702 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Rieth, C. A., Cai, D. J., McDevitt, E. A. & Mednick, S. C. The role of sleep and practice in implicit and explicit motor learning. Behav. Brain Res. 214, 470-474 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Török, B., Janacsek, K., Nagy, D. G., Orbán, G. & Nemeth, D. Measuring and filtering reactive inhibition is essential for assessing serial decision making and learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 146, 529 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J. P. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2, e124 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S. E., Lau, M. Y. & Howard, G. S. Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean? American Psychologist 70, 487 (2015). [CrossRef]

- OpenScienceCollaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 (2015).

- Rickard, T. C., Pan, S. C. & Gupta, M. W. Severe Publication Bias Contributes to Illusory Sleep Consolidation in the Motor Sequence Learning Literature. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition (in press). [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U., Hallschmid, M., Rasch, B. & Born, J. Brief sleep after learning keeps emotional memories alive for years. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 788-790 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Csabi, E. et al. Declarative and Non-declarative Memory Consolidation in Children with Sleep Disorder. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 709, (2015). [CrossRef]

- Association, A. P. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, (2020). (American Psychological Association, 2019).

- Dienes, Z. How Bayes factors change scientific practice. J. Math. Psychol. 72, 78-89 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Dienes, Z., Coulton, S. & Heather, N. Using Bayes factors to evaluate evidence for no effect: examples from the SIPS project. Addiction 113, 240-246 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Dienes, Z. & Mclatchie, N. Four reasons to prefer Bayesian analyses over significance testing. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 207-218 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. et al. Bayesian inference for psychology. Part I: Theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 35-57 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Rouder, J. N. Optional stopping: No problem for Bayesians. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 21, 301-308 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F. D., Wagenmakers, E.-J., Zehetleitner, M. & Perugini, M. Sequential hypothesis testing with Bayes factors: Efficiently testing mean differences. Psychol. Methods 22, 322 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Brown, H. & Maylor, E. A. Memory consolidation effects on memory stabilization and item integration in older adults. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24, 1032-1039 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D. & Iverson, G. Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 16, 225-237, (2009). [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, A. F. & Wiley, J. What are the odds? A practical guide to computing and reporting Bayes factors. The Journal of Problem Solving 7, 2 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P. D. The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. (Cambridge university press, 2010).

- Scullin, M. K. Sleep, memory, and aging: the link between slow-wave sleep and episodic memory changes from younger to older adults. Psychol. Aging 28, 105 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ujma, P. P. Sleep spindles and general cognitive ability–A meta-analysis. Sleep Spindles & Cortical Up States 2, 1-17 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, S., Hartmann, F., Papassotiropoulos, A., de Quervain, D. J. & Rasch, B. No associations between interindividual differences in sleep parameters and episodic memory consolidation. Sleep 38, 951-959 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H. Bonferroni and Šidák corrections for multiple comparisons. Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics 3, 103-107 (2007).

- Forstmeier, W., Wagenmakers, E. J. & Parker, T. H. Detecting and avoiding likely false-positive findings–a practical guide. Biological Reviews 92, 1941-1968 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Bódizs, R. et al. Prediction of general mental ability based on neural oscillation measures of sleep. J. Sleep Res. 14, 285-292, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. et al. Sleep Spindles and Intellectual Ability: Epiphenomenon or Directly Related? J Cogn Neurosci 29, 167-182, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z., Ray, L. B., Owen, A. M. & Fogel, S. M. Brain Activation Time-Locked to Sleep Spindles Associated With Human Cognitive Abilities. Front Neurosci 13, 46, (2019). [CrossRef]