1. Introduction

Wastewater and environmental surveillance (WES) has emerged as a powerful tool for monitoring population-level pathogen circulation during COVID-19 pandemic (Kilaru et al. 2023; Mao et al. 2020). WES is most commonly used in sewered settings; however, its value is also evident in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with non-sewered systems, where access to health care is limited, clinical data are often incomplete or fragmented and the risk of outbreaks is high (Abdul-Rahman et al. 2023; Asantewaa et al. 2024; Hamilton et al. 2024; Maree et al. 2025). In such contexts, WES can provide critical information on pathogen circulation and serve as an early warning system to guide targeted public health interventions. WES has been successfully applied to viral pathogens in Africa, such as poliovirus and SARS-CoV-2, for which harmonised methodology protocols are available (Manyanga et al. 2025; Hamisu et al. 2022; Dzinamarira et al. 2022; Iwu-Jaja et al. 2023; Shempela et al. 2024; WHO 2003; WHO 2024a). However, its application to bacterial pathogens causing diarrhoeal diseases, such as toxigenic Vibrio cholerae (O1/O139) causing cholera and Salmonella Typhi causing typhoid fever, has been limited, despite their considerable burden across sub-Saharan Africa (Chigwechokha et al. 2024; Street et al. 2025; Uzzell et al. 2024a; Uzzell et al. 2024b).

While well-established WES systems operate in several high-resource settings (Bubba et al. 2023; Keshaviah et al. 2023), in Africa the development of such systems remains limited, with fragmented efforts often preventing comparability across sites or countries. A harmonised approach to WES implementation is important to generate comparable data and strengthen surveillance capacity in sub-Saharan Africa. Harmonisation of sampling strategies and establishment of quality assurance systems for laboratory protocols are essential to ensure that data generated are not only robust within countries but also comparable across borders, thereby strengthening regional collaboration and supporting timely responses to public health threats (Lundy et al. 2021; Servetas et al. 2022).

WES can provide insights into pathogen circulation within communities and serve as an early warning system for outbreaks (Bibby et al. 2021; Mao et al. 2020). However, in many low resource regions, sanitation infrastructure is heterogeneous, encompassing both sewered and non-sewered systems, as well as environmental water bodies that receive untreated human waste (Capone et al. 2025; Delgado Vela et al. 2024). Sampling these different matrices is therefore critical to characterise pathogen circulation and trends, which can subsequently inform public health actions aimed at reducing exposure and disease risk. While international initiatives, such as those by the World Health Organization, have emphasized the need to include non-sewered settings as possible target matrices in WES, empirical data from these environments remain scarce (Keshaviah et al. 2023; WHO 2024a).

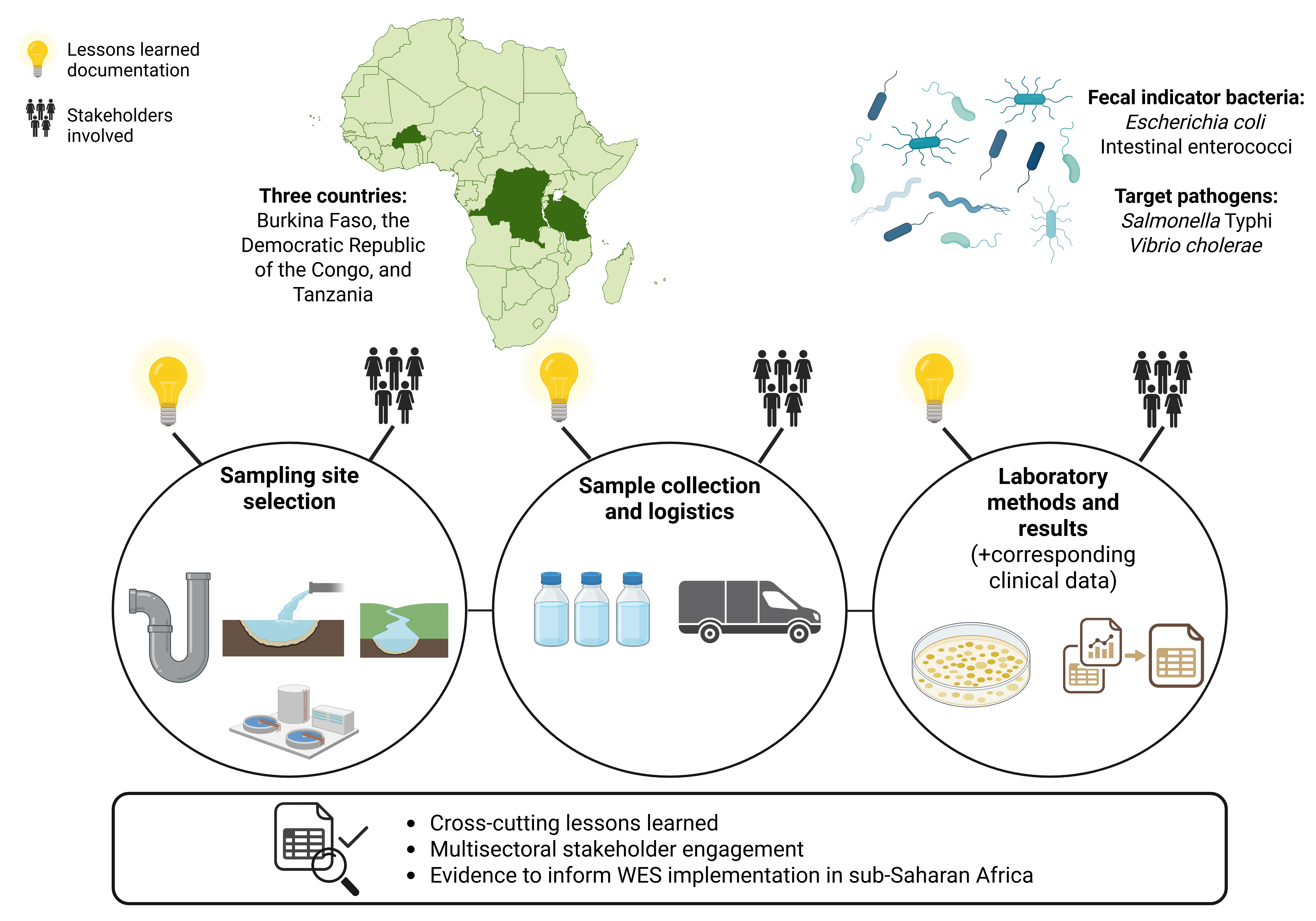

As part of the ODIN consortium project (

https://odin-wsp.tghn.org/), this study documents both the successes and the challenges encountered when implementing a WES framework in sub-Saharan Africa. The study explores the surveillance of two major waterborne pathogens,

V. cholerae and

S. Typhi, across strategically selected urban and rural settings in Burkina Faso, the DRC, and Tanzania, using wastewater and surface water sampling data from 2025, alongside corresponding clinical data to assess their public health relevance. In addition, it highlights the central role of stakeholder engagement in shaping practical implementation and coordination across sectors, by documenting how stakeholders influenced site selection, data flow, and the operationalisation of WES activities. Finally, the study provides operational lessons and recommendations to guide the expansion of effective WES systems throughout Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stakeholder Engagement During the WES Design and Implementation

Stakeholder engagement was a central component throughout both the design and implementation of the WES systems in Burkina Faso, the DRC, and Tanzania. From the initial project kick-off and stakeholder workshops to the operational phase, diverse stakeholders, including public health authorities, local water agencies, laboratory personnel, and environmental health experts, were actively involved and had clear roles (Tiwari & Miller et al. 2025) (

Table 1).

All three countries held meetings with the stakeholders throughout the sampling campaign to review and confirm the selection of surveillance sites and target pathogens. Regular internal project meetings were held with all participating countries to share and discuss experiences, successes, and challenges.

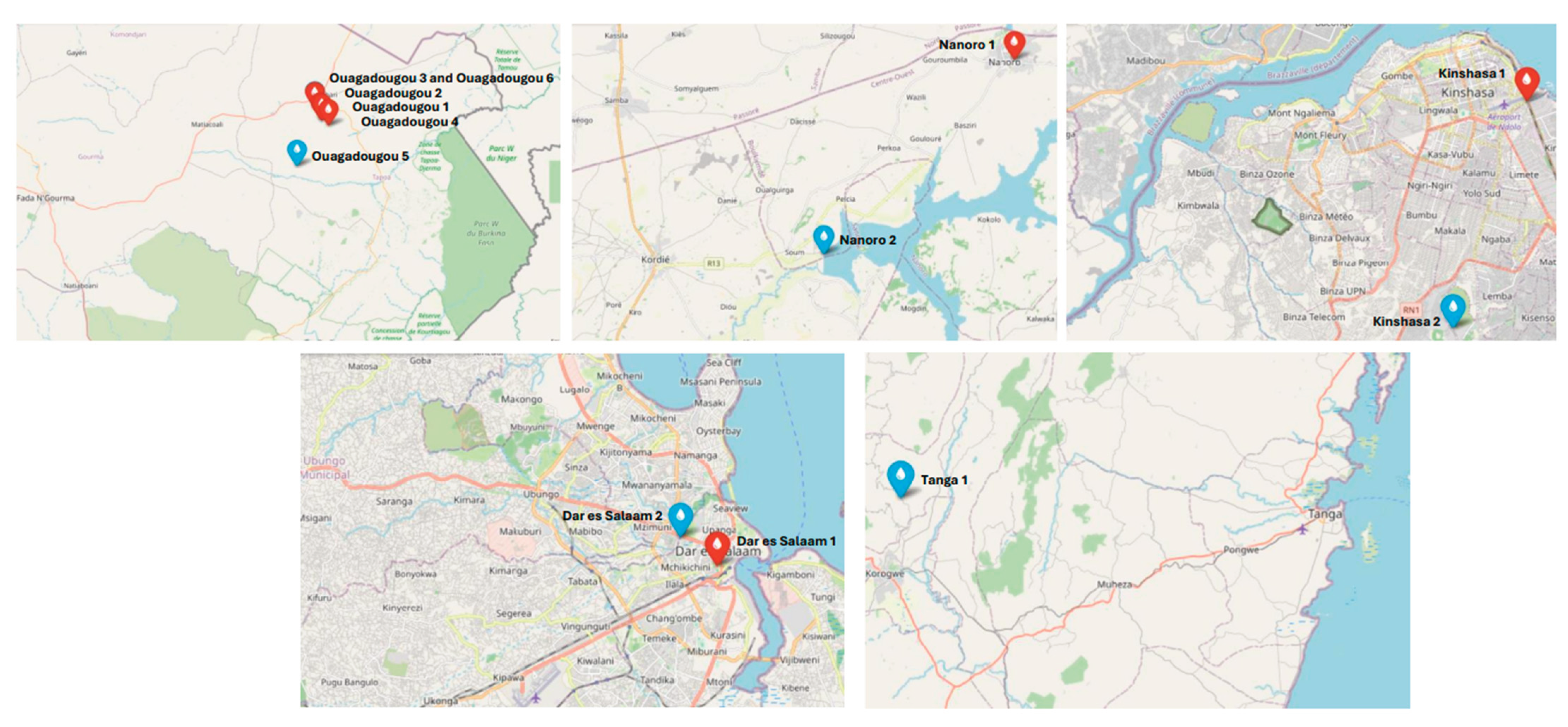

2.2. Sampling Site Selection and Corresponding Clinical Data

The study sites for the project, Ouagadougou and Nanoro in Burkina Faso, Kinshasa in the DRC, and Dar es Salaam and Tanga in Tanzania, were selected and mapped to capture a comprehensive picture of cholera and typhoid fever burden in each location. Local research teams led the design by mapping potential sampling locations and engaging with a broad range of stakeholders to ensure feasibility and contextual relevance (Tiwari & Miller et al. 2025).

Sampling was designed to integrate WES of wastewater from both sewered and non-sewered systems together with surface waters impacted by human waste discharge (

Figure 1 and

Table 2). Sampling sites were also selected for their proximity to the laboratories responsible for sample analysis, ensuring efficient logistics to preserve sample integrity and thus minimise pathogen degradation. Local teams collaborated with the national Poliovirus Surveillance Units, operating under the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), which has long-standing WES experience for poliovirus in Africa, and received guidance in selecting sampling locations (WHO 2003; WHO 2022). Following GPEI guidance, factors such as site accessibility, stakeholder collaboration and coordination (including epidemiologists, laboratory personnel, and local public health authorities), and the potential safety hazards at sampling sites were assessed through site inspections (WHO 2003).

In this study, wastewater refers to both sewered and non-sewered systems containing human faecal waste. Sewered systems consist of networks of pipes that collect and transport wastewater from sources to centralised wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) or designated disposal points, whereas non-sewered systems are not connected to a centralised sewer. Examples of non-sewered systems include septic tanks, pit latrines, and open channels. Surface waters refer to environmental water, such as rivers, ponds, and dams, that are impacted by human faecal waste.

2.2.1. Clinical Surveillance Data

To contextualise the WES findings, available clinical data on cholera and typhoid fever were obtained from the same regions where environmental samples were collected. In Burkina Faso and the DRC, clinical surveillance data were sourced from national surveillance systems coordinated by the respective Ministries of Health (MoH). In Tanzania, data were obtained through regional public health surveillance structures. For Tanzania, data were not yet available at the time of analysis but are currently being collected from relevant stakeholders (

Table 1). For this study, only aggregated case numbers were acquired, no individual-level data were collected.

In Burkina Faso, clinical surveillance is coordinated by the MoH’s Department of Disease Surveillance, which receives monthly case reports from all health facilities via the standard Rapport mensuel d’activités (RMA). Case reporting at peripheral health centres is largely syndromic, as routine laboratory confirmation is limited due to diagnostic capacity. Typhoid fever (often combined with paratyphoid fever data) and cholera are notifiable diseases. For the ODIN project, aggregated case counts for cholera and typhoid fever were obtained from the MoH’s Studies and Sectoral Statistics Department for health facilities within the catchment areas corresponding to the sampling sites.

In the DRC, clinical surveillance for typhoid fever and cholera is conducted through the MoH’s decentralized system, with monthly case number reports submitted by public health facilities to their respective health zones. Typhoid fever (often combined with paratyphoid fever data) and cholera cases are primarily diagnosed based on clinical presentation, without routine laboratory confirmation. For the ODIN project, aggregated case counts were obtained from the relevant health zones, with authorization from the Provincial Health Division, for areas corresponding to the sampling sites.

In Tanzania, clinical surveillance data is being obtained from a technical department within the regional public health authority. Cholera data is sourced from the national Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system, which compiles weekly reports from health facilities through district, regional, and national levels, as cholera is a notifiable disease. All reported cholera cases are laboratory confirmed. In contrast, typhoid fever data is derived from routine clinical reporting and limited surveillance activities, with cases identified based on either laboratory confirmation or clinical syndromic diagnosis.

2.3. Choosing the Target Diarrhoeal Pathogens and Faecal Indicator Bacteria

The target pathogens for the WES system were selected based on local epidemiological evidence, prior knowledge of regional outbreaks, existing surveillance programs, and the results of a priority pathogen survey conducted during stakeholder workshops (Tiwari & Miller et al. 2025). In addition, a harmonised list of target pathogens was agreed upon across all three countries to enable consistent application of the shared ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ODIN 2025). The target pathogens selected for this study were S. Typhi and toxigenic V. cholerae (O1/O139). Additionally, Escherichia coli and intestinal enterococci were included as faecal indicator bacteria (FIBs) to assess the level of recent faecal contamination in the collected samples.

2.4. Study Site Operations and Sample Management

Prior to the initiation of the sampling campaign, laboratory audits were conducted in all three participating countries to assess existing capacity, quality standards, and occupational safety precautions. The audits, performed by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), were conducted in line with the methodologies described in the ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ODIN 2025). In addition, the sampling procedures, sample transportation, and laboratory analyses were piloted at the end of 2024 before the start of the full sampling campaigns.

2.4.1. Wastewater and Environmental Sample Collection

Wastewater and surface water sampling locations of this study were sampled monthly by grab sampling according to ISO 19458 (ISO 19458:2006 Water quality – Sampling for microbiological analysis) from January to September 2025. A total of 112 environmental samples were collected from 13 wastewater and surface water sampling locations across Burkina Faso (n=71, including 44 wastewater and 27 surface water samples, from eight sites), the DRC (n=16, including eight wastewater and eight surface water samples, from two sites), and Tanzania (n=25, including seven wastewater and 18 surface water samples, from three sites). A maximum of two samples per sampling location were missing during the sampling period (Supplemental

Table S1). The local project teams were responsible for sample collection, and a dedicated sample collection form was developed to record sampling metadata (Supplemental Material 1). All sampling was conducted following appropriate safety protocols, including adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) (ODIN 2025). Team members involved in sampling received specific training for these procedures. The recommended sample volume for wastewater was 500 ml and for surface waters 3 litres.

2.4.2. Logistics, Cold Chain Maintenance, and Sample Storage

Samples were transported to the laboratory either in Crēdo Cube® system (va-Q-tec, Germany) or in insulated cool boxes with ice packs in accordance with ISO 19458 (ODIN 2025). Sample temperature (°C) was recorded at the time of sampling and upon arrival at the laboratory. Additionally, the air temperature at the time of sample collection was recorded. Upon arrival at the laboratory, samples were either immediately processed or stored at appropriate temperatures (2-8 °C) and processed within 24 hours following the sample collection.

2.5. Laboratory Methodologies and Data Management

Samples were processed in accordance with the ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ODIN 2025), following the agreed protocols across all three countries. However, some deviations from the protocols were necessary, as described below, to accommodate differences in available reagents and equipment. Analyses were conducted at the Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro in Burkina Faso, at the Centre for Research and Studies on Emerging and Re-emerging Diseases (CREMER) in the DRC, and in Tanzania at the National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL) in Dar es Salaam and the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) Laboratory in Tanga.

2.5.1. Laboratory Analyses for FIB: Escherichia coli and Intestinal Enterococci

ODIN Laboratory Handbook refers to standard methods ISO/DIS 9308-4 and ISO 7899-2:2000 for enumeration of E. coli and intestinal enterococci, respectively. E. coli and intestinal enterococci were analysed by the membrane filtration technique filtering a known volume of the sample through pore a size of 0.45-µm membrane filter or by spread plating tenfold serial dilutions of the sample on tryptone bile X-glucuronide agar (TBX) medium and Slanetz & Bartley agar (S&B) medium. Analysed sample volumes depended on the expected faecal contamination level and the filterability of the sample. After incubation, green to turquoise colonies on TBX were counted as E. coli and red colonies on S&B as presumptive enterococci. Intestinal enterococci colonies were confirmed on Bile esculin azide agar (BEA) medium as typical colonies that darkened after incubation.

In the DRC, FIB analyses for wastewater samples were not conducted according to established methods. For surface water, E. coli was measured in 1 ml and 10 ml sample volumes using membrane filtration. Intestinal enterococci were not analysed in samples from the DRC.

FIB results were reported as a colony-forming units CFU/100 ml for surface water and CFU/ml for wastewater.

2.5.2. Laboratory Analyses for Vibrio Cholerae

Vibrio cholerae was analysed according to the methodology described in the ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ODIN 2025). In brief, from 1 ml to 100 ml of the water samples, depending on the sample type and filterability, were filtered through pore size of 0.45-µm membrane filter, which was then placed either directly on thiosulphate citrate bile and sucrose agar (TCBS) medium in Tanzania, or first into alkaline peptone water for enrichment at 35±2°C for 4 hours in Burkina Faso and for 24 hours in the DRC. After enrichment, 10 µL of the enriched broth was inoculated onto TCBS agar. Furthermore, highly turbid wastewater samples were analysed by spread plating the tenfold serial dilution of wastewater sample directly on TCBS medium. After incubation, yellow colonies on TCBS were counted as presumptive V. cholerae. The species identification of presumptive V. cholerae colonies was performed using MALDI-ToF MS (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry), or with API 20E (BioMérieux, Marcy-L’Étoile, France) identification protocols.

Serotyping with O1 and O139 antisera was used to identify toxigenic V. cholerae O1/O139 isolates instead of the methodology recommended in the ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ctxA PCR) to verify the presence of the cholera toxin gene.

2.5.3. Laboratory Analyses for Salmonella Typhi

Salmonella spp. was analysed according to the ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ODIN 2025), following the principles of standard method ISO 19250:2010. The analysed sample volume varied between 1 ml and 250 ml depending on the sample type and filterability of the samples. In brief, Salmonella spp. was analysed by filtering known volume of the sample on one or more membrane filters with pore size of 0.45-µm and placing the filters either on Buffered Peptone Water or Alkaline Peptone Water for pre-enrichment, incubated at 36±2 °C for 18±2 hours to promote bacterial growth, or on Rappaport-Vassiliadis broth with soya (RVS). Following pre-enrichment, the samples were cultured in Modified Semisolid Rappaport Vassiliadis Medium (MSRV) at 41.5±1 °C for 24±3 hours. After incubation, typical mobile growth on MSRV was cultivated on selective xylose lysine deoxycholate agar (XLD) and incubated at 36±2 °C for another 24±3 hours. Black colonies on XLD were counted as presumptive Salmonella spp. In protocol without pre-enrichment, RVS broth was inoculated on selective xylose lysine deoxycholate agar (XLD) or on Hecktoen Agar medium and typical colonies were counted as presumptive Salmonella spp. Species identification of the presumptive Salmonella spp. colonies was performed by using MALDI-ToF MS, or API 20E identification protocols.

For the isolates identified as Salmonella enterica, serotyping with antisera agglutination was performed to identify serotype S. Typhi according to the method described in ODIN Laboratory Handbook (ODIN 2025). However, in Burkina Faso, only the agglutination to Salmonella Multi Group Poly A-I + Vi antisera testing was performed, and isolates that were Vi-positive were interpreted as presumptive S. Typhi.

2.5.4. Wastewater and Environmental Data Management

To ensure standardised recording and comparability of results across countries, harmonised data recording procedures were implemented across all sites. These procedures captured general information for each sampling event, details of the laboratory methodologies applied, and confirmation results for the target pathogens. Qualitative outcomes (presence/absence and analysed volume) for S. Typhi and V. cholerae and quantitative outcomes (CFUs per volume) for FIBs were recorded.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

For each sampling location, descriptive statistics were calculated for faecal indicator bacteria (E. coli and intestinal enterococci), with counts expressed as log10 CFU/ml for wastewater and log10 CFU/100 ml for surface water matrices. Positivity rates, median values with interquartile ranges (IQR), minimum and maximum values per site were reported, with IQRs calculated only for locations with three or more positive samples. All descriptive analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Wastewater and Environmental Sampling Results

Wastewater and environmental surveillance results for target pathogens

Salmonella Typhi,

Vibrio cholerae, along with FIBs, and corresponding clinical data were recorded for wastewater and surface water samples from Burkina Faso, the DRC, and Tanzania (

Table 3 and Supplemental

Table S1).

In Burkina Faso, presumptive

S. Typhi was detected by antisera agglutination-based techniques at three wastewater sampling locations (Ouagadougou 2 and 3, and Nanoro 1), with all detections occurring in June 2025; these isolates will be further confirmed whole-genome sequencing (

Table 3 and Supplemental

Table S1). No

V. cholerae was detected in Burkina Faso during the study period. In the DRC, neither

V. cholerae nor

S. Typhi was detected at any sampling locations. In Tanzania, presumptive

S. Typhi, i.e.

S. enterica spp.

enterica that requires further confirmation by serotyping or whole-genome sequencing, was detected at the surface water site Tanga 1 from May to August 2025.

V. cholerae was detected at one wastewater sampling location (Dar es Salaam 1) in June 2025; the isolate was a non-O1/non-O139 serotype.

FIBs levels were assessed across wastewater and surface water samples collected at all study sites in Burkina Faso, the DRC, and Tanzania. Counts, positivity rates, and distributions of

E. coli and intestinal enterococci counts are summarised in

Table 4.

Across all study sites, FIBs were frequently detected (

Table 4). In Burkina Faso, all sampling locations in Ouagadougou and Nanoro were positive at least once for both

E. coli and intestinal enterococci. In the DRC, Kinshasa 2 was positive for

E. coli. All sampling locations in Dar es Salaam and Tanga were positive for

E. coli at least once during the sampling period, while intestinal enterococci were detected at all locations except Dar es Salaam 2. Overall, positivity rates were consistently higher for

E. coli than for intestinal enterococci, with the highest

E. coli positivity rates (100%) observed at Ouagadougou 4, Ouagadougou 5, and Tanga 1. The highest intestinal enterococci positivity rates were observed at surface water sites (78% at Ouagadougou 5 and Ouagadougou 6, and 100% at Tanga 1). Maximum concentrations for both

E. coli and intestinal enterococci were recorded in Ouagadougou, with the highest wastewater counts at Ouagadougou 3 and the highest surface water counts at Ouagadougou 6.

3.2. Clinical Data Corresponding to Sampling Locations

In Burkina Faso and the DRC, clinical data corresponding to the sampling locations are presented in Supplemental

Table S1, while

Table 3 summarises the number of sampling sites with and without nearby reported clinical cases and the corresponding environmental detections of target pathogens and FIBs. Typhoid fever cases were combined with paratyphoid fever cases (

Table 3 and Supplemental

Table S1). In Ouagadougou, the sampling locations Ouagadougou 1 and 2, and then again 3 and 6, were located within the same health facility area. Typhoid fever cases were reported around all sampling locations in both countries, with case numbers varying between 0-401 cases in Ouagadougou, and 8-25 cases in Nanoro, and 1606-4834 in Kinshasa. Cholera cases were not reported in Burkina Faso during the sampling period. In the DRC, cholera cases were reported in six out of eight sampled months from the nearby catchment area of Kinshasa 1 location (case numbers ranging from 2 to 194). At Kinshasa 2, cholera cases were reported during June–August 2025 (42, 8, and 2 cases, respectively).

Clinical data from Tanzania is currently being collected from relevant stakeholders.

3.3. Lessons Learned from the Implementation of WES in Sub-Saharan Africa

Key lessons were identified across multiple aspects of the project, from capacity building to laboratory analyses, regarding the design and implementation of WES in sub-Saharan Africa (

Table 5). The lessons learned were documented throughout the sampling period and discussed in various meetings.

Existing laboratory and field capacities varied between sites, highlighting the need for refresher training, ongoing technical support, and formal collaboration agreements to mitigate high staff turnover. A clear definition of stakeholder roles and building on existing systems (e.g., GPEI) was also essential for sustaining WES implementation. Site selection required early definition of WES objectives, stakeholder consultation, and careful consideration of population coverage, particularly in non-sewered or rural settings where data were scarce or fragmented. Country-specific experiences highlighted the importance of flexible site selection and contingency planning: in the DRC, planned sampling in Goma was relocated to Kinshasa due to security concerns. Clinical data limitations, such as combined (typhoid and paratyphoid fever clinical data) or syndromic case reporting, also complicated comparisons with environmental results.

Coordinating sampling timetables and ensuring timely sample transport proved challenging, particularly in large urban areas or during seasonal disruptions, and accessing certain sites required advance planning and collaboration with local authorities. Laboratory capacity was a critical challenge, as culture-based methods were technically demanding, and local reagent supply was limited. Data processing and flow were often slow, limiting the potential for timely public health action.

4. Discussion

The greatest opportunities, and perhaps the most significant challenges, for wastewater and environmental surveillance (WES) currently lie in Africa, as it is particularly valuable when it fills critical information gaps, especially in settings where clinical surveillance data are limited and delayed. These limitations in clinical surveillance are further amplified in many African contexts by recurrent disease outbreaks, rapid urbanization, and environmental degradation, which together hinder reliable and timely public health surveillance and actions (Manirambona et al. 2024).

This study explored and evaluated the implementation of WES for diarrhoeal waterborne pathogens across three sub-Saharan African countries: Burkina Faso, the DRC, and Tanzania. By targeting V. cholerae and S. Typhi, and incorporating sewered, non-sewered, and surface water sampling matrices, the study assessed the feasibility of WES in diverse sanitation contexts. The findings highlight both the practical challenges and the successes of designing, implementing, and harmonising WES systems, offering insights for future surveillance initiatives in LMIC settings.

4.1. WES Implementation and Laboratory Findings

To reflect the diversity of sanitation infrastructures across the study countries, the ODIN project incorporated sewered and non-sewered systems, and surface water bodies as sampling matrices. In settings with minimal or poorly structured sewer coverage, non-sewered systems and environmental water bodies, such as rivers and dams, can capture pathogens shed by local populations (Acharya et al. 2024; Saleem et al. 2019; WHO 2019). In this study, wastewater sites included closed sewage systems, such as a manhole and wastewater pipelines, WWTPs, and an open channel serving as non-sewered system. Surface water sampling targeted rivers and dams receiving untreated sewage outflows, including human waste and greywater discharges, serving as a critical proxy for community-level pathogen circulation, particularly in informal urban and peri-urban settlements where sewer networks are scarce. Several sites were affected by open defecation or solid waste inputs, conditions that increase the likelihood of detecting human-derived pathogens. Others were impacted by upstream agricultural, industrial, or hospital discharges, introducing complex mixtures of contaminants that can affect pathogen persistence and detection (Borreca et al. 2024; Emmanuel et al. 2009; Sasakova et al. 2018). High-mobility areas, including densely populated trading zones, allowed monitoring of transient populations. Together, these complementary sampling strategies supported more equitable geographic and demographic surveillance coverage and could help capture populations that may be frequently overlooked in conventional WES programs.

In addition to site characteristics, population coverage—the size and composition of the contributing population—is important consideration for WES. Guidance from the GPEI indicates that poliovirus detection sensitivity is strongly influenced by the size of the catchment population, with optimal sampling recommended for sites serving 100,000–300,000 individuals (WHO 2023). High-density areas are prioritised due to their greater likelihood of revealing pathogen circulation. Although similar recommendations do not exist for bacterial pathogens, applying population-based considerations to diarrhoeal disease WES could improve data reliability. In sub-Saharan Africa, however, accurate population estimates are often unavailable, and data sources vary substantially between countries (Seidler et al. 2025). In this study, only 5 out of 13 sampling locations met GPEI’s recommended catchment size for poliovirus. In high-resource settings, wastewater-based surveillance often uses population coverage estimates and wastewater treatment plant influent flow data to normalise WES results (Boogaerts et al. 2024; Kankaanpää et al. 2016; Tiwari et al. 2022). However, this approach is not feasible in most LMIC locations, particularly for non-sewered systems and surface waters, where waste originates from dispersed households, mobile populations, upstream communities, and unaccounted populations. Despite these limitations, population coverage estimates remain essential for linking environmental surveillance signals to the associated communities, thereby helping to ensure accurate reflection of community-level pathogen circulation and supporting public health decision-making.

E. coli and intestinal enterococci are the faecal indicator bacteria to assess faecal contamination in sampled water. Both organisms are widely used in environmental microbiology because they reliably reflect recent faecal inputs and are strongly associated with human and animal waste (Devane et al. 2020; Murei et al. 2024). S. Typhi and toxigenic V. cholerae (O1/O139) were selected as target pathogens due to their continued public health relevance in sub-Saharan Africa, where typhoid fever and cholera continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality (GTFCC 2025; Koua et al. 2025; Liu et al. 2025). In Burkina Faso, typhoid fever remains a significant concern, with recent estimates reporting an incidence of 133 cases per 100,000 person-years (Marks et al. 2024). In the DRC, both diseases are endemic, with recurrent cholera outbreaks reported particularly in eastern provinces and urban informal settlements, alongside a substantial but under-documented burden of typhoid fever due to limited laboratory confirmation (Théophile et al. 2018; WHO 2025b). In Tanzania, cholera outbreaks also recur; the 2024 wave affected multiple regions with thousands of reported cases and deaths (WHO 2024b). Typhoid fever is also endemic in Tanzania, and studies indicate a substantial national burden, with isolates presenting resistance genes (Cutting et al. 2022; Thriemer et al. 2012). WES has been previously applied for both V. cholerae (Bwire et al. 2018; Kahler et al. 2015; Zohra et al. 2021), and S. Typhi (Matrajt et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2021; Uzzell et al. 2024a; Uzzell et al. 2024b) surveillance. Moreover, the inclusion of both pathogens to WHO’s guidance on “Wastewater and environmental surveillance for one or more pathogens: guidance on prioritization, implementation and integration” further supported the decision to include them to this study (WHO 2024a). However, their environmental epidemiology differs substantially. Detection of toxigenic V. cholerae in environmental samples must be interpreted cautiously due to the organism’s ability to persist independently of human infections (GTFCC 2022), whereas S. Typhi is human-specific and therefore more directly indicative of human shedding.

In this study, FIB analysis confirmed widespread faecal contamination at most sampling locations, demonstrating that selected sites were indeed impacted by human or animal waste and suitable for environmental surveillance. Across all sites and nine months of sampling, culture-based methods detected presumptive S. Typhi at seven time points (three in Burkina Faso, four in Tanzania) and V. cholerae once (in Tanzania). These relatively low detection rates are consistent with previous culture-based WES studies. For example, Shackelford et al. (2025) did not detect V. cholerae from pit latrines and faecal sludge by culture during an outbreak in a Malawian refugee camp, and Chigwechokha et al. (2024) reported reduced sensitivity for S. Typhi using culture methods. Despite the low number of positive detections in this study, all three countries continued to prioritise V. cholerae and S. Typhi for WES. This prioritisation was reaffirmed during project meetings, where country teams consistently identified these pathogens as high public health priorities, highlighting the need to further develop environmental surveillance systems for their detection.

Although many previous WES studies rely on PCR-based detection due to its higher sensitivity (Capone et al. 2021; Johnson et al. 2022; Saha et al. 2019; Servetas et al. 2022; Uzzell et al. 2024a; Uzzell et al. 2024b; Zohra et al. 2021), the ODIN project intentionally employed culture-based methods to enable quantification of viable bacteria and subsequent genomic epidemiology in comparison to the clinical strains. Implementing harmonised culture-based protocols from the ODIN Laboratory Handbook revealed substantial variation in baseline capacity for microbiological water analyses across the countries and partner laboratories. Key gaps related to the availability of the standardized laboratory protocols, negative and positive controls, membrane filtration techniques, selective culture media suitable for environmental samples with variable background flora, and capacity to perform bacteriological confirmatory tests. Implementation in the DRC was further complicated by a concurrent mpox outbreak, leading the team to incorporate mpox into their sampling and analysis (Beiras et al. 2025; WHO 2025a). These operational challenges underscore the need for flexibility and contingency planning when conducting WES in dynamic epidemiological contexts.

Timely and accurate data recording emerged as a cross-cutting challenge. Environmental surveillance generates complex datasets requiring detailed metadata, site-specific contextualisation, and clear documentation of detection limits. Well-functioning systems that incorporate standardised electronic data collection tools, harmonised reporting structures, and targeted training in environmental data management can reduce errors and maintain timely data flow, thereby strengthening the role of WES as an epidemiological tool. Notably, in most countries, WES is not integrated into national health systems, so even when findings are communicated, timely public health responses may not follow. Ensuring comparable data structures across countries is essential for harmonisation and facilitates future integration into regional dashboards accessible to health professionals, supporting coordinated public health decision-making.

4.2. Contextualising WES Data with Clinical Surveillance Data

Interpreting wastewater and environmental detections in the context of clinical surveillance data proved challenging. In this study, due to the low number of pathogen detections in WES samples, no statistical analyses between WES and clinical data could be conducted. Visual inspection of the data also did not reveal a consistent lead–lag pattern, including WES detections preceding reported clinical cases of typhoid fever and cholera, consistent with findings from a previous study (Uzzell et al. 2024b).

Interpretation is complicated by clinical surveillance practices in many African countries, where reporting is largely syndromic and enteric fever cases are frequently combined. These challenges can obscure early warning and local transmission dynamics at specific sampling locations. Cholera surveillance faces similar limitations, as microbiological laboratory confirmation of the cases can be limited. Syndromic reporting, combined with limited access to healthcare, may delay detection of pathogens and result in underreporting of certain diseases, particularly where healthcare facilities and diagnostic services are scarce. Consequently, many outbreak- and pandemic-prone diseases go unreported (Mremi et al. 2021). These structural limitations of clinical surveillance underscore the value of WES as a complementary surveillance tool.

Linking WES findings to clinical data is critical, particularly when evaluating the suitability of WES for specific pathogens. However, variations in data quality across countries make cross-country comparisons, and consequently the generation of harmonised results, particularly challenging. Strengthening linkages between environmental and clinical surveillance through collaboration with national and regional epidemiological teams is therefore essential to clearly defining the type and quality of clinical data required for WES. Within the ODIN project, such collaboration has already been initiated to raise awareness about WES, clarify clinical data requirements, and establish systems for collecting the clinical case data needed to support WES activities.

4.3. WES as a Multidisciplinary Tool

WES is inherently a multidisciplinary approach, bridging public health, environmental science, microbiology, epidemiology, water sector and engineering, aligning with the One Health framework. Its successful implementation depends on early and sustained stakeholder engagement, clear allocation of responsibilities, and well-defined data flow pathways between field workers, laboratories, epidemiological teams, and decision-makers. As WES ultimately aims to generate actionable data for public health decision-making, establishing clear and proactive operational and communication frameworks are essential (Van Der Drift et al. 2025). Experience from implementing WES highlighted differences in institutional structures and stakeholder roles across sub-Saharan African countries, underscoring the need for flexible, context-specific workflows adapted to local systems rather than uniform implementation models.

Leveraging existing initiatives, such as GPEI and established programs for SARS-CoV-2 environmental surveillance provide a practical foundation for scaling WES. In this study, shared sampling locations and infrastructure with GPEI facilitated implementation and underscored the efficiency advantages of integrating WES into existing surveillance systems. Regional initiatives led by organisations such as Africa Centre for Disease Control (Africa CDC), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and Global Consortium for Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance for Public Health (GLOWACON) further offer opportunities to promote harmonisation, capacity building, and sustainability, complementing clinical surveillance systems for local public health decision-making and improved health strategies (Africa CDC 2026; GLOWACON 2026; UNEP 2026).

To promote effective and enduring stakeholder engagement in WES, several best practices emerging from the ODIN project should be adopted, such as the importance of early planning, transparent communication, continuous feedback mechanisms, and shared ownership among stakeholders. Maintaining transparency and accountability throughout implementation is essential to ensure that surveillance data and needed public health decisions are communicated clearly.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, laboratory audits and training assessments were conducted mostly online rather than in person, limiting the ability to fully evaluate hands-on laboratory capacity and procedural adherence. In the DRC, the relocation of project activities from Goma to Kinshasa after the laboratory audits had been completed posed additional challenges, as the Kinshasa laboratory was only assessed via document-based audit after project activities had already been initiated. Second, these activities were conducted only in English, not by using the local languages, and the participation of the technical personnel directly responsible for performing the analyses was limited. Third, methodological differences between countries, including deviations in the FIB analyses in the DRC, as well as delays and difficulties in obtaining essential laboratory materials, hindered adherence to harmonised SOPs and highlight the practical challenges of implementing harmonised WES efforts. Fourth, the overall number of positive detections for presumptive S. Typhi and V. cholerae was low, limiting the ability to conduct statistical analyses or draw definitive conclusions regarding associations between WES and clinical data. Finally, clinical surveillance data were often aggregated at the district level and syndromic in nature, complicating the validation and interpretation of environmental findings. Collectively, these limitations underscore the challenges of implementing WES in resource-limited settings and the need for strategic planning, standardisation, and continued capacity building.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that implementing WES for waterborne diarrhoeal pathogens across diverse sub-Saharan African settings is feasible, but requires careful consideration of local epidemiology, sanitation infrastructure, sustainability, and population dynamics. Despite low target pathogen detection during the sampling campaign, the study highlights the value of combining multiple sampling matrices, including wastewater and surface waters, and integrating faecal indicator bacteria to confirm the representativeness of the samples and to validate the site selection. The use of culture-based methods underscored the need for targeted training and commitment of the laboratory teams to follow the standardised procedures to maintain data quality, reliability, and comparability. Linking and analysing WES findings with clinical data remains challenging due to syndromic surveillance, combined data, and population estimation uncertainties, yet such integration is critical for meaningful interpretation. The study underscores that successful WES requires multidisciplinary collaboration and early, structured stakeholder engagement, leveraging existing programs and One Health frameworks to enhance operational efficiency, harmonisation, and sustainability. Overall, these findings provide practical guidance for scaling WES in LMICs and reinforce its potential as a complementary tool for community-level pathogen monitoring and evidence-informed public health decision-making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was part of the ODIN consortium project “Strengthening Environmental Surveillance to Advance Public Health Action”. The project is supported by the Commission of the European Communities as part of the Horizon Europe – the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (Grant Agreement no 101103253) and Global Health EDCTP3. Additionally, Taru Miller received personal research support from Maa- ja vesitekniikan tuki ry (MVTT), which partly contributed to the preparation of this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all stakeholders and ODIN consortium members, as well as the field and laboratory teams who supported sample collection and analysis. We also thank Jeremy Cook for providing the sampling location maps for Figure 1.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Taru Miller: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, visualisation, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing. Kristiina Valkama: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing. Vito Baraka: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing – review & editing. Marc Christian Tahita: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualisation, and writing – review & editing. Vivi Maketa: supervision, project administration, writing – review & editing. Eric Lyimo: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, and writing – review & editing. Hillary Sebukoto: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, and writing – review & editing. Palpouguini Lompo: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualisation, and writing – review & editing. Bérenger Kaboré: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualisation, and writing – review & editing. Zakaria Garba: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualisation, and writing – review & editing. Sibidou Yougbare: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualisation, and writing – review & editing. Melissa Kabena: project administration, writing – review & editing. Evodie Ngelesi: project administration, writing – review & editing. Jackson Clever: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, and writing – review & editing. Peter Mkama: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualization, and writing – review & editing. Modest Chuwa: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, and writing – review & editing. Steven Mnyawonga: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, and writing – review & editing. Outi Nyholm: methodology, writing – review & editing. Ana Maria de Roda Husman: conceptualisation, supervision, writing – review & editing. Tarja Pitkänen: conceptualisation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the ODIN project activities was obtained from relevant national ethics committees. In Burkina Faso, approval was granted under approval certificate number Deliberation No. 2024-05-138. In the DRC, the ethical approval was granted under the certificate number N°535/CNES/BN/PMMF/202 du 20/05/2024. In Tanzania, the ethical approval was granted under certificate number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/4654, with an extension NIMR/HQ/R.8c/Vol.I/2998.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abdul-Rahman, T.; Ghosh, S.; Lukman, L.; Bamigbade, G.B.; Oladipo, O.V.; Amarachi, O.R.; Olanrewaju, O.F.; Toluwalashe, S.; Awuah, W.A.; Aborode, A.T.; et al. Inaccessibility and low maintenance of medical data archive in low-middle income countries: Mystery behind public health statistics and measures. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2023, 16(10), 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, J.; Jha, R.; Gompo, T.R.; Chapagain, S.; Shrestha, L.; Rijal, N.; Shrestha, A.; Koirala, P.; Subedi, S.; Tamang, B.; et al. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)–Producing Escherichia coli in Humans, Food, and Environment in Kathmandu, Nepal: Findings From ESBL E. coli Tricycle Project. International Journal of Microbiology 2024, 2024(1), 1094816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa CDC. Development of a Continental Strategy for Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance (WES). 2026. Available online: https://africacdc.org/opportunity/development-of-a-continental-strategy-for-wastewater-and-environmental-surveillance-wes/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Asantewaa, A.A.; Odoom, A.; Owusu-Okyere, G.; Donkor, E.S. Cholera Outbreaks in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in the Last Decade: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12(12), 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiras, C.G.; Malembi, E.; Escrig-Sarreta, R.; Ahuka, S.; Mbala, P.; Mavoko, H.M.; Subissi, L.; Abecasis, A.B.; Marks, M.; Mitjà, O. Concurrent outbreaks of mpox in Africa—An update. The Lancet 2025, 405(10472), 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; Wu, Z.; North, D. Making waves: Plausible lead time for wastewater based epidemiology as an early warning system for COVID-19. Water Research 2021, 202, 117438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boogaerts, T.; Van Wichelen, N.; Quireyns, M.; Burgard, D.; Bijlsma, L.; Delputte, P.; Gys, C.; Covaci, A.; Van Nuijs, A.L.N. Current state and future perspectives on de facto population markers for normalization in wastewater-based epidemiology: A systematic literature review. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 935, 173223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreca, A.; Vuilleumier, S.; Imfeld, G. Combined effects of micropollutants and their degradation on prokaryotic communities at the sediment–water interface. Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), 16840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubba, L.; Benschop, K.S.M.; Blomqvist, S.; Duizer, E.; Martin, J.; Shaw, A.G.; Bailly, J.-L.; Rasmussen, L.D.; Baicus, A.; Fischer, T.K.; et al. Wastewater Surveillance in Europe for Non-Polio Enteroviruses and Beyond. Microorganisms 2023, 11(10), 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwire, G.; Debes, A.K.; Orach, C.G.; Kagirita, A.; Ram, M.; Komakech, H.; Voeglein, J.B.; Buyinza, A.W.; Obala, T.; Brooks, W.A.; et al. Environmental Surveillance of Vibrio cholerae O1/O139 in the Five African Great Lakes and Other Major Surface Water Sources in Uganda. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, D.; Chigwechokha, P.; De Los Reyes, F.L.; Holm, R.H.; Risk, B.B.; Tilley, E.; Brown, J. Impact of sampling depth on pathogen detection in pit latrines. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15(3), e0009176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, D.; Chiluvane, M.; Cumbane, V.; Dalton, J.; Holcomb, D.; Kowalsky, E.; Lai, A.; Mataveia, E.; Monteiro, V.; Rao, G.; et al. Environmental pathogen surveillance in cities without universal conventional wastewater infrastructure

. In Public and Global Health; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigwechokha, P.; Nyirenda, R.L.; Dalitsani, D.; Namaumbo, R.L.; Kazembe, Y.; Smith, T.; Holm, R.H. Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella Typhi culture-based wastewater or non-sewered sanitation surveillance in a resource-limited region. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2024, 34(3), 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, E.R.; Simmons, R.A.; Madut, D.B.; Maze, M.J.; Kalengo, N.H.; Carugati, M.; Mbwasi, R.M.; Kilonzo, K.G.; Lyamuya, F.; Marandu, A.; et al. Facility-based disease surveillance and Bayesian hierarchical modeling to estimate endemic typhoid fever incidence, Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania, 2007–2018. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16(7), e0010516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado Vela, J.; Philo, S.E.; Brown, J.; Taniuchi, M.; Cantrell, M.; Kossik, A.; Ramaswamy, M.; Ajjampur, S.S.; Guerfali, F.Z.; Holm, R.H.; et al. Moving beyond Wastewater: Perspectives on Environmental Surveillance of Infectious Diseases for Public Health Action in Low-Resource Settings. Environment & Health 2024, 2(10), 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devane, M.L.; Moriarty, E.; Weaver, L.; Cookson, A.; Gilpin, B. Fecal indicator bacteria from environmental sources; strategies for identification to improve water quality monitoring. Water Research 2020, 185, 116204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Murewanhema, G.; Iradukunda, P.G.; Madziva, R.; Herrera, H.; Cuadros, D.F.; Tungwarara, N.; Chitungo, I.; Musuka, G. Utilization of SARS-CoV-2 Wastewater Surveillance in Africa—A Rapid Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(2), 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, E.; Pierre, M.G.; Perrodin, Y. Groundwater contamination by microbiological and chemical substances released from hospital wastewater: Health risk assessment for drinking water consumers. Environment International 2009, 35(4), 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLOWACON. The Global Consortium for Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance for Public Health. 2026. Available online: https://glowacontest.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- GTFCC. Global Task Force on Cholera Control. Technical Note Environmental Surveillance for Cholera Control. 2022. Available online: https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/gtfcc-technical-note- (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- GTFCC. Global Task Force on Cholera Control. Cholera—global situation. GTFCC Cholera Dashboard. 2025. Available online: https://www.gtfcc.org/about-cholera/cholera-facts/#ss4 (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Hamilton, K.A.; Wade, M.J.; Barnes, K.G.; Street, R.A.; Paterson, S. Wastewater-based epidemiology as a public health resource in low- and middle-income settings. Environmental Pollution 2024, 351, 124045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamisu, A.W.; Blake, I.M.; Sume, G.; Braka, F.; Jimoh, A.; Dahiru, H.; Bonos, M.; Dankoli, R.; Mamuda Bello, A.; Yusuf, K.M.; et al. Characterizing Environmental Surveillance Sites in Nigeria and Their Sensitivity to Detect Poliovirus and Other Enteroviruses. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 225(8), 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu-Jaja, C.; Ndlovu, N.L.; Rachida, S.; Yousif, M.; Taukobong, S.; Macheke, M.; Mhlanga, L.; Van Schalkwyk, C.; Pulliam, J.R.C.; Moultrie, T.; et al. The role of wastewater-based epidemiology for SARS-CoV-2 in developing countries: Cumulative evidence from South Africa supports sentinel site surveillance to guide public health decision-making. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 903, 165817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Sharma, J.R.; Ramharack, P.; Mangwana, N.; Kinnear, C.; Viraragavan, A.; Glanzmann, B.; Louw, J.; Abdelatif, N.; Reddy, T.; et al. Tracking the circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa using wastewater-based epidemiology. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1), 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahler, A.M.; Haley, B.J.; Chen, A.; Mull, B.J.; Tarr, C.L.; Turnsek, M.; Katz, L.S.; Humphrys, M.S.; Derado, G.; Freeman, N.; et al. Environmental Surveillance for Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae in Surface Waters of Haiti. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2015, 92(1), 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankaanpää, A.; Ariniemi, K.; Heinonen, M.; Kuoppasalmi, K.; Gunnar, T. Current trends in Finnish drug abuse: Wastewater based epidemiology combined with other national indicators. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 568, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshaviah, A.; Diamond, M.B.; Wade, M.J.; Scarpino, S.V.; Ahmed, W.; Amman, F.; Aruna, O.; Badilla-Aguilar, A.; Bar-Or, I.; Bergthaler, A.; et al. Wastewater monitoring can anchor global disease surveillance systems. The Lancet Global Health 2023, 11(6), e976–e981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilaru, P.; Hill, D.; Anderson, K.; Collins, M.B.; Green, H.; Kmush, B.L.; Larsen, D.A. Wastewater Surveillance for Infectious Disease: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Epidemiology 2023, 192(2), 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koua, E.L.; Moussana, F.H.; Sodjinou, V.D.; Kambale, F.; Kimenyi, J.P.; Diallo, S.; Okeibunor, J.; Gueye, A.S. Exploring the burden of cholera in the WHO African region: Patterns and trends from 2000 to 2023 cholera outbreak data. BMJ Global Health 2025, 10(1), e016491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Q.; Chen, T.; Hu, B.; Shi, H. The global burden of typhoid and paratyphoid fever from 1990 to 2021 and the impact on prevention and control. BMC Infectious Diseases 2025, 25(1), 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ibaraki, M.; Kapoor, R.; Amin, N.; Das, A.; Miah, R.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Rahman, M.; Dutta, S.; Moe, C.L. Development of Moore Swab and Ultrafiltration Concentration and Detection Methods for Salmonella Typhi and Salmonella Paratyphi A in Wastewater and Application in Kolkata, India and Dhaka, Bangladesh. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 684094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Slobodnik, J.; Karaolia, P.; Cirka, L.; Kreuzinger, N.; Castiglioni, S.; Bijlsma, L.; Dulio, V.; Deviller, G.; et al. Making Waves: Collaboration in the time of SARS-CoV-2 - rapid development of an international co-operation and wastewater surveillance database to support public health decision-making. Water Research 2021, 199, 117167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirambona, E.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Shomuyiwa, D.O.; Denkyira, S.A.; Okesanya, O.J.; Haruna, U.A.; Salamah, H.M.; Musa, S.S.; Nkeshimana, M.; Ekpenyong, A.M. Harnessing wastewater-based surveillance (WBS) in Africa: A historic turning point towards strengthening the pandemic control. Discover Water 2024, 4(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyanga, D.; Maseti, E.; Mokoena, K.; Buthelezi, T.; Mthetwa, S.; Mokoena, S.; Khosa-Losela, E.; Wanyoike, S. Assessment of environmental surveillance for the detection of poliovirus implementation in the metropolitan districts of South Africa, 2020-2023. Pan African Medical Journal 2025, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Zhang, K.; Du, W.; Ali, W.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H. The potential of wastewater-based epidemiology as surveillance and early warning of infectious disease outbreaks. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2020, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maree, G.; Els, F.; Naidoo, Y.; Naidoo, L.; Mahamuza, P.; Macheke, M.; Ndlovu, N.; Rachida, S.; Iwu-Jaja, C.; Taukobong, S.; et al. Wastewater surveillance overcomes socio-economic limitations of laboratory-based surveillance when monitoring disease transmission: The South African experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE 2025, 20(2), e0311332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, F.; Im, J.; Park, S.E.; Pak, G.D.; Jeon, H.J.; Wandji Nana, L.R.; Phoba, M.-F.; Mbuyi-Kalonji, L.; Mogeni, O.D.; Yeshitela, B.; et al. Incidence of typhoid fever in Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Madagascar, and Nigeria (the Severe Typhoid in Africa programme): A population-based study. The Lancet Global Health 2024, 12(4), e599–e610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matrajt, G.; Lillis, L.; Meschke, J.S. Review of Methods Suitable for Environmental Surveillance of Salmonella Typhi and Paratyphi. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020, 71 (Supplement_2), S79–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mremi, I.R.; George, J.; Rumisha, S.F.; Sindato, C.; Kimera, S.I.; Mboera, L.E.G. Twenty years of integrated disease surveillance and response in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and opportunities for effective management of infectious disease epidemics. One Health Outlook 2021, 3(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murei, A.; Kamika, I.; Momba, M.N.B. Selection of a diagnostic tool for microbial water quality monitoring and management of faecal contamination of water sources in rural communities. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 906, 167484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODIN; Al-Hello, H.; Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Finland; Nyholm, O.; Pitkänen, T. ODIN Laboratory Handbook Standard Operating Procedures for Pre-treatment of Environmental Samples, Pathogen Analytics and Whole Genome Sequencing. In ODIN Wastewater Surveillance Project [Internet]. The Global Health Network; Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL): Finland, 2025; Available online: https://odin-wsp.tghn.org/objectives-and-impact/reports/odin-laboratory-handbook-sop-environmental-samples/.

- Saha, S.; Tanmoy, A.M.; Andrews, J.R.; Sajib, M.S.I.; Yu, A.T.; Baker, S.; Luby, S.P.; Saha, S.K. Evaluating PCR-Based Detection of Salmonella Typhi and Paratyphi A in the Environment as an Enteric Fever Surveillance Tool. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2019, 100(1), 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Burdett, T.; Heaslip, V. Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19(1), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasakova, N.; Gregova, G.; Takacova, D.; Mojzisova, J.; Papajova, I.; Venglovsky, J.; Szaboova, T.; Kovacova, S. Pollution of Surface and Ground Water by Sources Related to Agricultural Activities. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2018, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, V.; Utazi, E.C.; Finaret, A.B.; Luckeneder, S.; Zens, G.; Bodarenko, M.; Smith, A.W.; Bradley, S.E.K.; Tatem, A.J.; Webb, P. Subnational variations in the quality of household survey data in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1), 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servetas, S.L.; Parratt, K.H.; Brinkman, N.E.; Shanks, O.C.; Smith, T.; Mattson, P.J.; Lin, N.J. Standards to support an enduring capability in wastewater surveillance for public health: Where are we? Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2022, 6, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackelford, B.B.; Chigwechokha, P.; Ziba, L.; Misomali, C.; Kanjiru, M.; Buleya, P.; Nyirenda, R.L.; Wolfe, M.K.; Holm, R.H. Culture method surveillance of Vibrio cholerae in a non-sewered sanitation refugee camp setting: Dzaleka Camp, Malawi; Public and Global Health; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shempela, D.M.; Muleya, W.; Mudenda, S.; Daka, V.; Sikalima, J.; Kamayani, M.; Sandala, D.; Chipango, C.; Muzala, K.; Musonda, K.; et al. Wastewater Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Zambia: An Early Warning Tool. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(16), 8839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, R.; Nkambule, S.; Mahlangeni, N.; Mthethwa, M.; Blose, N.; Genthe, B.; Kredo, T. Wastewater and environmental surveillance for Vibrio cholerae: A scoping review. Journal of Water and Health 2025, 23(6), 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théophile, M.K.; Archippe, B.M.; David, L.M.; Mihuhi, N.; Mutendela, J.K.; Kanigula, M. Antibio-résistance des souches de Salmonella ssp isolées des hémocultures à Bukavu en RD Congo. Pan African Medical Journal 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thriemer, K.; Ley, B.; Ame, S.; Von Seidlein, L.; Pak, G.D.; Chang, N.Y.; Hashim, R.; Schmied, W.H.; Busch, C.J.-L.; Nixon, S.; et al. The Burden of Invasive Bacterial Infections in Pemba, Zanzibar. PLoS ONE 2012, 7(2), e30350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Lipponen, A.; Hokajärvi, A.-M.; Luomala, O.; Sarekoski, A.; Rytkönen, A.; Österlund, P.; Al-Hello, H.; Juutinen, A.; Miettinen, I.T.; et al. Detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater influent in relation to reported COVID-19 incidence in Finland. Water Research 2022, 215, 118220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Miller, T.; Baraka, V.; Tahita, M.C.; Maketa, V.; Kaboré, B.; Kingpriest, P.T.; Mitashi, P.; Lyimo, E.; Sebukoto, H.; et al. Strengthening pathogen and antimicrobial resistance surveillance through environmental monitoring in sub-Saharan Africa: Stakeholder perspectives. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2025, 270, 114651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme – Wastewater Surveillance. 2026. Available online: https://www.unep.org/topics/ocean-seas-and-coasts/ecosystem-degradation-pollution/wastewater/wastewater-surveillance#:~:text=Wastewater%20surveillance%20is%20a%20useful,COVID%2D19%20and%20other%20diseases (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Uzzell, C.B.; Abraham, D.; Rigby, J.; Troman, C.M.; Nair, S.; Elviss, N.; Kathiresan, L.; Srinivasan, R.; Balaji, V.; Zhou, N.A.; et al. Environmental Surveillance for Salmonella Typhi and its Association With Typhoid Fever Incidence in India and Malawi. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024a, 229(4), 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, C.B.; Gray, E.; Rigby, J.; Troman, C.M.; Diness, Y.; Mkwanda, C.; Tonthola, K.; Kanjerwa, O.; Salifu, C.; Nyirenda, T.; et al. Environmental surveillance for Salmonella Typhi in rivers and wastewater from an informal sewage network in Blantyre, Malawi. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2024b, 18(9), e0012518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Drift, A.-M.R.; Welling, A.; Arntzen, V.; Nagelkerke, E.; Van Der Beek, R.F.H.J.; De Roda Husman, A.M. Wastewater surveillance studies on pathogens and their use in public health decision-making: A scoping review. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 993, 179982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for environmental surveillance of poliovirus circulation

. 2003. Available online: https://iris.who.int/items/88c61773-200c-4749-b763-e005c196301d (accessed on 3 February 2026).

- WHO. Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2017: Special focus on inequalities

. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516235 (accessed on 3 February 2026).

- WHO. Global Polio Surveillance Action Plan 2022–2024

. 2022. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/GPSAP-2022-2024-EN.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2026).

- WHO. GPEI Field guidance for the implementation of environmental surveillance for poliovirus

. 2023. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Field-Guidance-for-the-Implementation-of-ES-20230007-ENG.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2026).

- WHO. Wastewater and environmental surveillance for one or more pathogens. Guidance on prioritization, implementation and integration. 2024a. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/wastewater-and-environmental-surveillance-for-one-or-more-pathogens--guidance-on-prioritization--implementation-and-integration (accessed on 3 February 2026).

- WHO. How effective community engagement is saving lives in Tanzania during cholera outbreak. 2024b. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/united-republic-of-tanzania/news/how-effective-community-engagement-saving-lives-tanzania-during-cholera-outbreak (accessed on 3 February 2026).

- WHO. Mpox multi-country external situation, report No. 60. WHO: Geneva, 2025a; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox--external-situation-report--60---8-december-2025 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- WHO. WHO response to challenging cholera outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. 2025b. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-response-to-challenging-cholera-outbreak-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo (accessed on 11 February 2026).

- Zohra, T.; Ikram, A.; Salman, M.; Amir, A.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, Z.; Ahad, A. Wastewater based environmental surveillance of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae in Pakistan. PLOS ONE 2021, 16(9), e0257414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |