1. Introduction

Contemporary society is increasingly characterised by uncertainty, instability and the rapid circulation of events, values and truths, making it difficult to cultivate stable values and long-term perspectives, including those related to environmental responsibility. Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman [

1] conceptualised this condition as liquid modernity, describing a social context in which economic systems, political structures and cultural norms change more quickly than individuals can meaningfully adapt. In such conditions, dominant global economic and political paradigms continue to prioritise continuous growth and consumption, often directly contradicting the principles of sustainable development. Although globalisation has intensified interdependence across societies and cultures, it has also contributed to environmental degradation, ethical relativism and socially unsustainable practices. Experiences of existential insecurity – such as precarious employment, economic instability and accelerated technological change – further reinforce short-term thinking that often marginalises environmental concerns.

Alongside these structural conditions, psychological and emotional responses to environmental crises have become increasingly visible. Eco-anxiety, commonly described as a chronic fear of environmental catastrophe accompanied by feelings of helplessness, has been identified as particularly prevalent among younger generations [

2,

3]. In this context, the development of ecological literacy and sustainability-oriented awareness emerges as a pressing educational priority. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), as articulated by UNESCO, emphasises the integration of knowledge, values and competencies necessary for sustainable living and responsible citizenship [

4,

5]. Teachers play a critical role in mediating sustainability-related meanings, shaping not only learners’ knowledge but also their attitudes, values and worldviews. From this perspective, ecological literacy has become a central aim within teacher education. It extends beyond environmental knowledge to include ethical reflection, emotional engagement and an awareness of human–environment interdependence. Preparing future teachers to engage with sustainability therefore requires pedagogical approaches that address cognitive, affective and relational dimensions of learning. Visual arts education (VAE) offers a pedagogical space for engaging with sustainability through experiential, reflective and relational learning processes. Through artistic perception, interpretation and material engagement, sustainability-related issues can be approached in ways that support critical reflection and ecological awareness beyond purely cognitive or informational learning [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Despite the growing emphasis on sustainability within educational policy and discourse, empirical research examining how VAE can contribute to ecological thinking in teacher education remains limited. Existing studies often emphasise cognitive or behavioural outcomes, while fewer investigate interpretative, affective and experiential dimensions of sustainability learning. Responding to this gap, the present study explores how VAE can function as a pedagogical space for fostering ecological thinking and sustainability awareness among pre-service teachers. Specifically, it examines how engagement with contemporary visual artworks and art-making processes enables meaning-making related to ecological responsibility, emotional engagement and relational understandings of human–environment interactions within teacher education.

Accordingly, the study is guided by the following research questions:

How can contemporary visual art practices contribute to the development of ecological literacy and sustainability awareness among pre-service teachers?

How can contemporary visual arts practices be pedagogically contextualised within visual arts education to inspire sustainability-oriented reflection?

How do pre-service teachers experience and interpret ecological concepts through dialogue with contemporary artworks and through their own art-making processes within art-based pedagogical activities?

To address these questions, the study adopts a qualitative, interpretative approach aligned with arts-informed pedagogical perspectives that emphasise interpretation, reflection and contextual understanding.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainability Education, Ecological Literacy and Holistic Learning

Contemporary sustainability education increasingly recognises that environmental challenges cannot be addressed solely through technical solutions or the transmission of factual knowledge. Instead, sustainability is understood as a complex, value-laden and relational field that requires systemic thinking, ethical reflection and an awareness of human–environment interdependence [

10,

11,

12]. Within this discourse, ecological literacy has become a foundational educational goal.

Ecological literacy goes beyond environmental knowledge to include an understanding of ecological systems, recognition of interconnectedness, and the capacity to reflect on values, responsibilities and the consequences of human actions [

13,

14,

15]. From this perspective, ecological thinking involves a shift in perception and identity, fostering sensitivity to the relational dynamics between humans and the environment. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) aligns with this approach by emphasising integrative learning processes that connect cognitive, affective and ethical dimensions of sustainability [

16,

17], as reflected in the aims of SDG 4.7 and related sustainability targets. This emphasis aligns with broader trends in sustainability education research, which increasingly prioritise integrative, learner-centred and reflective approaches over transmissive models of learning [

18,

19]. Recent research further highlights the role of arts-based and creative pedagogies in supporting ecological literacy by enabling learners to engage with sustainability through experiential, interpretative and affective processes [

7,

20,

21].

A holistic approach to education reinforces this perspective by highlighting the interconnectedness of cognitive, emotional and psychomotor domains and advocating learning experiences that integrate knowledge, feeling and action [

22,

23,

24]. This approach shifts the focus from what is taught to how sustainability is experienced, interpreted and embodied within educational contexts. Through interdisciplinary integration – linking visual arts, environmental science, ethics and social studies – students can engage with ecological themes in rich, multimodal ways. Within such a framework, artistic practice emerges not only as a means of addressing sustainability-related issues, but also as a tool for reflective learning that supports the development of creativity, empathy and ethical reasoning as core professional competencies for future educators.

2.2. Meaning-Making in Sustainability Education

Learning for sustainability is increasingly understood as a process of meaning-making rather than the acquisition of predefined knowledge. Meaning-making involves learners actively constructing understanding by interpreting experiences, emotions, and information within specific social and cultural contexts [

25,

26]. This perspective is particularly relevant in sustainability education, where ecological issues are marked by uncertainty, ethical tension, and contested meanings.

Research consistently shows that sustainability-related learning encompasses intertwined cognitive, affective, and ethical dimensions, which require integrated pedagogical approaches. Educational practices that emphasise emotional engagement and reflective interpretation are therefore better able to support learners in negotiating complexity, reflecting on values, and imagining alternative futures – processes central to sustainability-oriented learning and especially important in arts-based and interpretative educational contexts.

2.3. Visual Arts Education as a Pedagogical Space for Sustainability

Building on this understanding, VAE provides a pedagogical space for engaging with sustainability through experiential, reflective, and relational learning processes. Unlike instructional approaches that prioritise fixed outcomes, arts-based learning emphasises open-ended inquiry, sensory perception, personal interpretation, and imagination as central modes of knowing [

27,

28]. Artistic images, materials, and spatial interventions do not convey singular or closed meanings; instead, they invite learners to actively construct understanding through perception, emotion, and reflection.

This open-ended quality makes VAE particularly suited to addressing complex sustainability issues such as ecological responsibility, human–nature relationships, and material awareness [

29,

30]. Through artistic engagement, learners are encouraged to question dominant narratives, explore ambiguity, and connect personal experience with broader socio-ecological concerns. In this sense, visual arts function not merely as illustrative content but as a medium for critical reflection and meaning-making within sustainability education.

For pre-service teachers, engagement with visual arts can foster pedagogical sensitivity towards sustainability by highlighting how learning processes are shaped by values, emotions, and relational understanding [

31,

32]. Such engagement is particularly relevant in teacher education, where future educators are expected to navigate complexity and facilitate sustainability-oriented learning in diverse and unpredictable classroom contexts.

2.4. Contemporary Art as Pedagogical Case Examples in Sustainability Education

Contemporary art practices increasingly engage with ecological themes by addressing environmental degradation, material consumption, perceptions of nature, and human–environment relations in the context of the Anthropocene. Rather than conveying didactic messages or proposing solutions, contemporary artworks often operate through ambiguity, disruption, and critical inquiry, inviting viewers to reflect on their own positions within complex ecological systems.

Artworks that foreground materiality, perception, fragility, and interdependence serve as pedagogical case examples capable of mediating sustainability-related meanings. Through their open-ended structures, such works enable interpretative engagement with ecological issues that resists simplification and acknowledges uncertainty, ethical tension, and relational complexity. This quality aligns with sustainability education approaches that emphasise systems thinking and relational understanding over linear or solution-oriented frameworks.

From an educational perspective, contemporary artworks can be used as interpretative resources that support dialogic inquiry and reflective meaning-making. Their resistance to fixed interpretation encourages learners to negotiate multiple perspectives, attend to affective and sensory responses, and explore ecological issues as situated and value-laden rather than abstract or purely informational. Research on place-based and context-sensitive arts practices similarly highlights the capacity of contemporary art to mediate sustainability discourse through experiential and relational engagement [

33,

34].

In this study, contemporary artworks are used as pedagogical case examples that illustrate diverse aesthetic and conceptual strategies for addressing ecological concerns. Although the selected artists are situated within a specific cultural context, the analysis focuses on thematic and conceptual dimensions that resonate with broader sustainability discourses and are pedagogically transferable across educational settings.

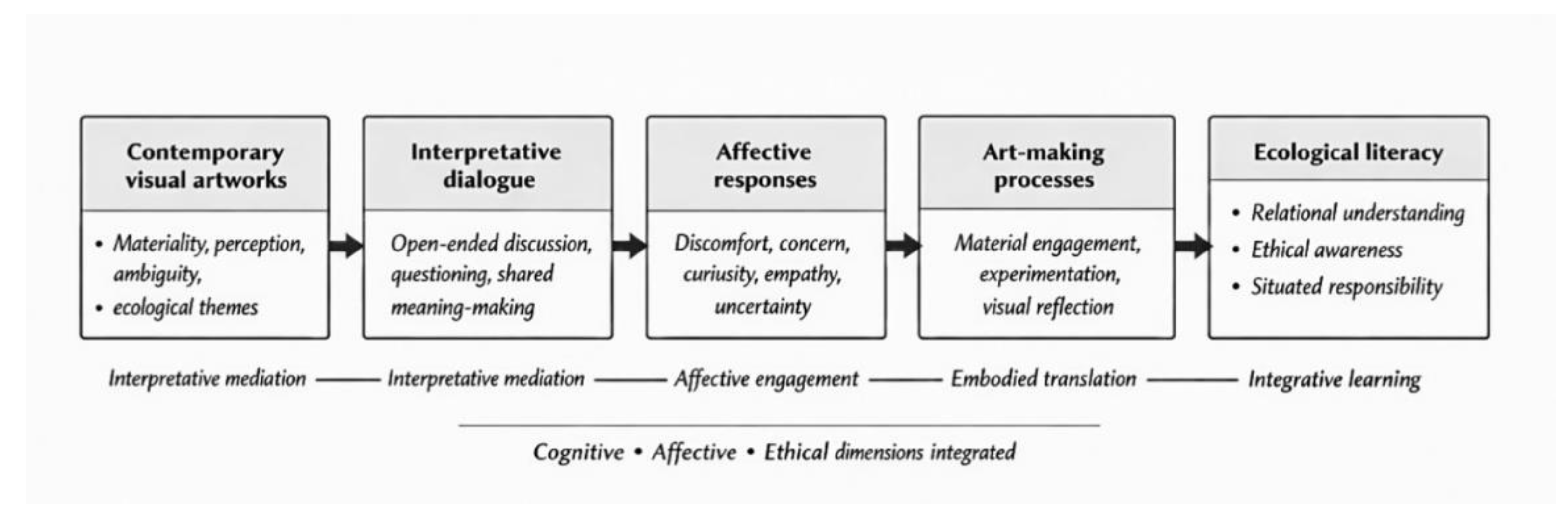

Takoen together, these theoretical perspectives position sustainability education as a meaning-oriented, experiential, and relational process, and VAE as a pedagogical space capable of supporting such learning (

Figure 1). The emphasis on ecological literacy, holistic learning, and meaning-making provides a conceptual foundation for interpretative approaches that attend to learners’ experiences, perceptions, and reflections. Within this framework, engagement with contemporary art is understood both as a pedagogical strategy and as a mode of inquiry that enables the exploration of ecological concepts beyond purely cognitive forms of learning. These considerations inform the adoption of a qualitative, interpretative research design focused on pre-service teachers’ engagement with ecological themes through dialogue with artworks and art-based pedagogical activities.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

Guided by the theoretical framework outlined above, this study adopts a qualitative, interpretative research design grounded in arts-based educational research and visual hermeneutics. The research is exploratory and conceptual, aiming to examine how visual arts education can contribute to the development of ecological thinking and sustainability awareness in teacher education. Rather than measuring learning outcomes or establishing causal relationships, the study focuses on processes of meaning-making, interpretative engagement, and pedagogical potential.

The methodological framework integrates three complementary components: interpretative visual analysis of selected artworks, a pedagogical case study approach embedded in higher education teaching practice, and reflective analysis of students’ art-making processes. These components are supported by a conceptual synthesis of literature from sustainability education and visual arts education. Sustainability is approached as a complex, value-laden, and experiential field, which calls for research strategies capable of addressing affective, ethical, and imaginative dimensions alongside cognitive understanding [

23,

35]. Within this framework, visual arts function both as an object of interpretation and as a pedagogical medium through which ecological concepts can be explored and articulated. This orientation aligns with arts-based research perspectives that conceptualise artistic practice as a mode of inquiry capable of generating situated, experiential, and reflective knowledge [

36,

37].

The study involved a total of 69 second- and third-year pre-service teachers enrolled in two consecutive Visual Arts courses during the 2022/2023 academic year. All research activities were embedded within regular course teaching. The central thematic framework, Understanding the Anthropocene through Dialogue with Visual Art, guided the selection of artworks, pedagogical activities, and students’ creative and reflective tasks. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and students’ reflections and artworks were analysed in anonymised form for research purposes.

3.2. Selection of Artistic Case Examples

Rather than seeking representativeness or generalisation, the study used selected contemporary artists as artistic case examples. The artists – Sebastijan Dračić, Kristian Kožul, Bojan Šumonja and Ivana Franke – were chosen for their conceptual engagement with themes relevant to the Anthropocene, including human–environment relations, materiality, perception, responsibility and systemic interdependence, as well as their capacity to provoke interpretative dialogue within an educational context. Their practices encompass diverse artistic strategies, conceptual approaches and media, including painting, sculpture, installation and spatial intervention. Although the artworks originate from Croatian contemporary art practice, their inclusion is based on thematic and conceptual relevance to broader ecological and sustainability-related discourses, rather than national or cultural specificity. Accordingly, the pedagogical approach developed in this study is transferable and may be applied using artworks from other cultural contexts, provided they engage with comparable environmental concerns and relational understandings of human–environment interactions.

The artworks were selected for their ability to evoke ecological reflection without relying on explicit environmental messaging. In this study, they are approached not as isolated objects of aesthetic analysis, but as pedagogical resources capable of mediating ecological meanings and supporting interpretative, affective and ethical engagement.

3.3. Interpretative Visual Analysis (Visual Hermeneutics)

The analysis of artworks was conducted using an interpretative visual hermeneutic approach [

26,

38], which conceptualises images as culturally and contextually situated forms of meaning-making. Interpretation is understood as a dialogic process that emerges through the interaction between the artwork, the viewer, and broader socio-ecological discourses [

39,

40]. The interpretative process followed a hermeneutic cycle, moving iteratively between close observation and description of visual, material, and spatial elements, contextualisation, and reflective interpretation within ecological, philosophical, and educational frameworks. Analytical attention focused on symbolism, material choices, modes of representation, and the affective responses elicited by the artworks. This iterative movement enabled meanings to emerge progressively through interpretative engagement, rather than being imposed through predefined analytical categories.

3.4. Pedagogical Engagement with Artworks

The selected artworks were incorporated into VAE courses for pre-service teachers using a range of art-based pedagogical methods, including guided dialogic discussion, reflective note-taking, associative drawing, role-play, and project-based learning. These methods were intended to support experiential, reflective, and relational engagement with sustainability-related themes.

Pedagogical activities typically began with collective viewing and open-ended discussion, encouraging students to express personal interpretations and negotiate shared meanings. Reflective notes and short written responses captured individual impressions, emotional reactions, and emerging ecological reflections. Visual and performative activities enabled students to translate abstract ecological ideas into material and symbolic forms, while role-play supported perspective-taking and ethical reflection. Small-scale artistic projects fostered sustained engagement with ecological themes over time.

Students’ reflections and artworks were treated as illustrative pedagogical materials rather than as data subjected to formal coding. They were examined through iterative thematic reading and visual interpretation, with analytical attention given to recurring concepts, emotional expressions, and sustainability-related meanings. Student statements presented in the Results and Discussion sections are analytically synthesised representations of shared interpretative patterns identified across written reflections, group discussions, and art-based responses, rather than verbatim quotations attributed to individual participants. All statements were anonymised to protect individual voices while preserving the integrity of collective meaning-making processes.

3.5. Conceptual and Pedagogical Synthesis

Complementing the interpretative and pedagogical components, the study used a conceptual synthesis to integrate insights from VAE, ecological literacy, holistic education, and sustainability studies. This synthesis enabled connections between artistic interpretation, pedagogical practice, and broader educational paradigms, highlighting the role of VAE in fostering ecological awareness and ethical engagement. The synthesis informed the discussion of educational implications for teacher education by articulating how art-based approaches can support ecological thinking that is reflective, affective, and value-oriented. By combining artistic case examples, pedagogical engagement, and conceptual reflection, the methodological framework supports a multilayered exploration of sustainability within VAE. In line with the qualitative and interpretative research design, the analysis prioritised the generation of contextually grounded pedagogical insights rather than generalisable outcomes.

3.6. Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was addressed using strategies that supported credibility, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was enhanced through prolonged engagement in an authentic educational setting and an iterative interpretative process conducted throughout the study. Interpretative consistency was strengthened through triangulation of data sources, including students’ written reflections, dialogic discussions, and visual artworks. Confirmability was supported through reflective validation with participants to reduce potential researcher bias, while dependability was ensured by a transparent and coherent research design with clearly articulated pedagogical and analytical procedures.

4. Results

4.1. Interpretative Insights from Contemporary Artworks

The interpretative analysis of selected works by contemporary artists revealed a range of aesthetic and conceptual strategies through which ecological concerns and human–environment relations are foregrounded. Despite differences in medium and artistic language, the artworks consistently drew attention to issues of environmental degradation, material consumption, interconnectedness, and responsibility.

Dračić’s landscapes highlight ecological uncertainty through subtle symbolic and atmospheric disruptions, presenting nature as a space shaped by human intervention and temporal instability. Kožul’s sculptural works emphasise material excess and hybridity, drawing attention to the logic of consumer culture, overproduction, and disposability embedded in contemporary material practices. Šumonja’s figurative imagery situates human presence within natural environments marked by tension and dissonance, using recurring landscape motifs to signal social conformity, environmental neglect, and ethical erosion. Franke’s installations foreground perceptual instability and embodied spatial experience, directing attention to relational positioning and the limits of control in human–environment interactions.

The artworks thus served as pedagogical case examples mediating complex ecological meanings.

4.2. Pedagogical Engagement and Student Interpretations

Engagement with the artworks typically began with collective viewing and guided dialogic discussion based on interpretative analysis, enabling students to explore visual, material, and symbolic elements through open-ended questions. Students were encouraged to attend to the perceptual, material, and affective dimensions of the artworks, as well as to the broader socio-ecological questions they raised. To support individual reflection, students produced reflective notes and short written responses, documenting personal impressions and emerging ecological interpretations. Student statements presented in the Results section are analytically synthesised representations derived from students’ reflections and art-based responses, capturing recurring themes and dominant interpretative patterns across the data.

Art-making activities, including associative drawing and material-based responses, supported embodied and imaginative engagement with sustainability-related concepts. Role-play and perspective-taking activities encouraged students to adopt non-human or alternative viewpoints, fostering ethical reflection and relational thinking. Elements of a project-based approach enabled sustained engagement with ecological themes through small-scale artistic projects integrating interpretation, reflection, and creative production. Across these pedagogical encounters, students’ interpretations consistently extended beyond factual knowledge of environmental issues, approaching sustainability as an experiential and value-oriented process shaped through dialogue, affective response, and material exploration. The pedagogical process through which engagement with contemporary art unfolded – linking interpretative dialogue, affective engagement, and art-making activities – is schematically represented in

Figure 2, which illustrates the relational structure of learning that supported ecological literacy in the study.

4.3. Interpretative Contextualisation of Contemporary Artworks

Building on the pedagogical process outlined above, students’ interpretative engagement with contemporary artworks demonstrates how the pedagogical pathways were re-signified through perceptual, material, and symbolic registers. Rather than seeking explicit environmental messages, students constructed meaning through experiential interpretation, connecting the visual and material qualities of the artworks with broader socio-ecological conditions.

In dialogue with Dračić’s painterly landscapes, students reinterpreted atmospheric density and temporal duration as indicators of unsustainable accumulation and the long-term consequences of environmental change. Kožul’s hybrid assemblages were re-signified through affective responses such as discomfort and irony, which students associated with consumer excess and the instability of nature–culture boundaries. Interpretations of Šumonja’s landscapes often shifted towards themes of loss, alienation, and ecological injustice, situating environmental degradation within wider socio-political and ethical frameworks. Engagement with Franke’s installations prompted reflections on vulnerability, attentiveness, and embodied presence, as students interpreted perceptual disorientation as a metaphor for ecological interdependence and uncertainty.

Through these interpretative processes, students translated artistic affordances into situated ecological meanings, demonstrating how contemporary art can function as a pedagogical medium that supports reflective, affective, and relational engagement with sustainability.

4.4. Student Artistic Responses and Reflective Engagement

Following their interpretative engagement with the artworks, students created their own visual responses as a form of reflective meaning-making. These artworks did not seek to replicate the analysed artistic strategies; instead, they translated individual impressions, emotions, and ecological concerns into visual and material form. Recurring motifs included fragmentation, repetition, altered landscapes, relational structures, and symbolic emptiness, reflecting students’ attempts to visualise complex ecological tensions (

Table 1).

Students’ written reflections and group discussions indicate that the process of art-making supported the articulation of ambivalent and often emotionally charged sustainability-related experiences, including concern, uncertainty, responsibility, and empathy. Rather than attempting to resolve ecological issues, students used visual expression to negotiate tensions between agency and helplessness, as well as between hope and anxiety. In this sense, artistic production functioned as a mediating pedagogical space in which ecological thinking emerged as an open, relational, and reflective process shaped through material engagement and personal interpretation.

5. Discussion and Implications for Teacher Education

Classroom dialogue and artistic practice served as complementary spaces for exploring sustainability as a complex, relational, and value-laden field of inquiry. Teaching interventions were organised around open-ended reflective prompts that situated ecological issues within broader ethical, social, and existential frameworks. Guiding questions addressed human–environment relationships, perceptual and ethical dimensions revealed through artworks, and the ways artistic encounters challenge assumptions of responsibility, distance, and control. Further discussion focused on the boundaries of individual agency, the role of social, political, and economic structures, and the influence of emotions such as guilt or helplessness on willingness to act. Together, these prompts encouraged students to approach sustainability not as an external or abstract issue, but as a relational condition in which they are personally implicated. In order to avoid unnecessary repetition, the Discussion synthesises key patterns across the findings rather than reiterating descriptive details already presented in the Results section.

Throughout classroom discussions, a recurring tension emerged between students’ awareness of global environmental problems and their uncertainty about meaningful personal action. Responsibility was initially expressed in abstract terms and often attributed to governments, industries, or “society in general.” Through guided reflection, students increasingly adopted more situated and reflexive positions, articulated through analytically synthesised reflections such as

recognising themselves as part of broader socio-ecological systems, even when attempting to distance themselves, or

understanding responsibility not only as large-scale change but also as everyday choices and forms of participation. Several reflections further suggested that

responsibility begins not at the level of solutions, but at the level of awareness and everyday decision-making. These shifts indicate an emerging understanding of sustainability as an ethical and relational field grounded in participation and attentiveness, rather than as a purely technical or policy-driven issue, aligning with perspectives that emphasise relational agency and moral imagination [

41,

42,

43].

Engagement with contemporary artworks addressing accumulation, loss, and environmental degradation often elicited discomfort, anxiety, and uncertainty. Students expressed affective responses associated with eco-anxiety, including

unease when confronting overlooked environmental consequences and feelings of being overwhelmed by the scale of ecological problems relative to individual capacity. At the same time, artworks that allowed space for ambiguity and contemplation generated positive affective responses such as attentiveness, curiosity, empathy, and cautious hope. These patterns align with research showing that sustainability learning often evokes strong and ambivalent emotions, including concern, responsibility, and eco-anxiety [

44]. While such emotions may motivate engagement, they can also lead to withdrawal if educational contexts do not support reflection and sense-making. Interpretative patterns from students’ reflections suggest that

the absence of prescriptive messages enabled deeper engagement, and that experiencing discomfort was productive in revealing personal implication rather than externalising responsibility. Students frequently noted that

not being told what to think or do allowed them to remain with uncertainty and to recognise their own implication in ecological issues. Several reflections further indicated that

emotional tension played a productive role in reflection, as discomfort disrupted habitual distancing from environmental problems and prompted reconsideration of everyday choices and values. In this sense, discomfort was experienced not as an obstacle to learning, but as a productive condition for ethical reflection. This highlights the limitations of approaches that frame sustainability primarily as a technical or informational issue while marginalising its emotional and experiential dimensions. Consistent with research on climate change communication, emotions emerged as central to shaping understanding, motivation, and agency [

45,

46,

47,

48].

Material-based activities, including the use of recycled and found materials, enabled the translation of reflective discussion into embodied understanding, reinforcing arguments that learning through making can deepen ecological awareness [

49]. Students frequently noted that working with materials highlighted ecological processes such as accumulation, fragility, interdependence, and imbalance. Synthesised reflections indicated heightened awareness of how

material repetition and layering mirrored processes of environmental degradation and irreversibility. The deliberate choice to work with discarded materials was often described as both practical and symbolic, with students emphasising that

using waste materials made sustainability visible within the artistic process itself. Students consistently highlighted that

artistic practice enabled forms of insight not accessible through discussion alone. Reflections emphasised the value of non-verbal and embodied modes of thinking, with synthesised statements indicating that

shaping ideas visually allowed tensions to be sensed rather than merely articulated, and that

artistic work made it possible to explore contradictions without resolving them prematurely. Such responses underline the role of artistic activity in fostering tolerance for ambiguity and complexity – capacities essential for engaging with sustainability challenges characterised by uncertainty and ethical tension [

50,

51].

Reflective notes and discussions further revealed recurring feelings of responsibility, concern, and connectedness, while visual and performative tasks supported the articulation of abstract ecological concepts through symbolic and personal expression. The benefits of artistic engagement extended beyond the immediate learning context, as students reported increased confidence in using visual arts as a pedagogical tool for addressing ecological topics with future pupils. This finding aligns with research on sustainability competencies in teacher education, which emphasises pedagogical sensitivity, reflective capacity, critical distancing, and affective engagement alongside subject knowledge [

35,

52,

53]. Rather than offering solutions to environmental problems, such practices encouraged students to reconsider their own positionality within ecological systems and to reflect on the role of perception, values, and everyday choices in sustainability-oriented action. In line with interpretative approaches in education for sustainable development, the study foregrounds analytical depth and pedagogical insight by prioritising reflective meaning-making within situated educational contexts.

Within teacher education, sustainability literacy is increasingly understood as a relational and practice-oriented competence that requires interpretative and experiential learning opportunities [

54,

55]. From this perspective, the findings demonstrate that VAE – particularly through the use of contemporary artworks as pedagogical case examples – can support engagement with sustainability as an open-ended, meaning-oriented process responsive to ecological complexity and ambiguity. By resisting didactic messages and embracing uncertainty and multiplicity of meaning, artworks aligned with sustainability discourses that emphasise systems thinking and relational ontology. Approached as open-ended sites of interpretation, contemporary artworks enabled ecological thinking to emerge through dialogue, affective engagement, and reflective meaning-making, consistent with previous research on the role of the arts in sustainability education [

7,

34,

51].

Across the analysed artistic case examples, students’ interpretations shifted from descriptive or aesthetic responses to more relational and systemic understandings of ecological issues. Ecological problems were increasingly articulated not as external phenomena but as questions of responsibility, interdependence, and human positioning within ecological systems. This supports arguments that ecological literacy involves the integration of knowledge, values, emotions, and reflective awareness [

56,

57], and confirms the relevance of art-based approaches for addressing such complexity [

8,

9,

58].

The findings contribute to current debates on sustainability education by demonstrating how VAE can serve as a space for affective, ethical, and experiential engagement with ecological issues, complementing dominant cognitive and informational approaches. While knowledge-based approaches alone are widely recognised as insufficient for fostering long-term ecological responsibility, empirical illustrations of how interpretative, affective, and experiential dimensions can be integrated within teacher education remain limited. This study addresses that gap by showing how engagement with contemporary artworks, reflective dialogue, and material-based practice enables future teachers to approach sustainability as a relational and value-laden process.

In response to RQ1, the study shows that art-based educational projects contribute to ecological thinking by enabling pre-service teachers to approach sustainability as a relational, affective, and ethical field of inquiry. Through interpretative engagement with artworks and reflective art-making, students developed forms of ecological literacy that integrate emotional awareness, critical questioning, and recognition of human–environment interdependence. Addressing RQ2, the findings demonstrate that contemporary art practices can be pedagogically contextualised as interpretative case examples that stimulate sustainability-oriented reflection. When approached through guided visual interpretation rather than art-historical explanation, artworks served as catalysts for dialogue connecting personal experience with broader ecological challenges. In relation to RQ3, students experienced ecological concepts as emotionally charged and personally implicating rather than abstract or distant. Through art-making, these reflections were translated into material choices and visual strategies, indicating a shift towards viewing themselves as active participants within ecological systems rather than detached observers. Taken together, the findings suggest that VAE contributes to sustainability education not by transmitting solutions, but by cultivating reflective, affective, and relational capacities foundational to responsible ecological engagement.

6. Limitations

The study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the research employs a qualitative, interpretative design within a single institutional context and involves a relatively small group of pre-service teachers. While this approach allowed for an in-depth exploration of students’ experiences, interpretations, and meaning-making processes, the findings are context-specific and are not intended to be generalised beyond the studied setting.

Second, the study uses a purposive selection of contemporary artworks chosen for their conceptual engagement with ecological and sustainability-related themes. Although these artistic case examples provided meaningful pedagogical entry points, they do not represent exhaustive or definitive artistic approaches to sustainability-oriented engagement.

Third, the researcher’s dual role as course instructor and investigator may have influenced students’ participation and self-expression. To address this, all reflections and artworks were analysed in anonymised form, with analytical emphasis placed on recurring interpretative patterns rather than individual responses.

Finally, the study focuses on interpretative, affective and experiential dimensions of sustainability learning and does not include systematically collected empirical measures of learning outcomes. Its purpose is to illuminate pedagogical processes and potentials rather than to evaluate effectiveness. While not aiming at generalisation, the study offers context-sensitive insights that may inform similar pedagogical approaches in teacher education. Future research could extend these findings through longitudinal or mixed-method studies across multiple educational contexts.

7. Conclusions

Overall, visual arts education provides a pedagogical space for experiential, reflective, and relational engagement with sustainability in teacher education. Building on this premise, the study demonstrates how engagement with contemporary art and art-based pedagogical practices can support the development of ecological literacy and sustainability awareness among pre-service teachers.

By pedagogically contextualising contemporary artworks as interpretative case examples, visual arts education supports sustainability-oriented reflection that connects personal experience with broader ecological concerns. Through dialogue with artworks and art-making processes, students developed more situated and relational understandings of sustainability, foregrounding responsibility, agency, and material awareness.

In alignment with SDG 4, SDG 12, and SDG 13, the findings highlight the pedagogical relevance of VAE for sustainability-oriented learning in teacher education. Although context-specific and not intended for generalisation, the findings offer transferable insights for integrating art-based and reflective methodologies into sustainability-oriented teacher education across diverse educational contexts.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for all aspects of the study and manuscript preparation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived in accordance with institutional requirements for educational research involving anonymised course-based student reflections and artworks.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available due to privacy and consent restrictions related to student reflections and artworks.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT 5.2 to generate figures. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VAE |

Visual Arts Education |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| ESD |

Education for Sustainable Development |

References

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000.

- Ojala, M. Eco-anxiety. RSA Journal 2018, 164, 10–15.

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10149. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017.

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020.

- Berman, K.S. Finding Voice: A Visual Arts Approach to Engaging Social Change; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017.

- Graham, M.A. Art, ecology and art education: Locating art education in a critical place-based pedagogy. Stud. Art Educ. 2007, 48, 375–391.

- Heras, M.; Galafassi, D.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Ravera, F.; Berraquero-Díaz, L.; Ruiz-Mallén, I. Realising potentials for arts-based sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1875–1889. [CrossRef]

- Roosen, L.J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Swim, J.K. Visual art as a way to communicate climate change: A psychological perspective on climate change–related art. World Art 2018, 8, 85–110. [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, M. Education for sustainability as a frame of mind. In Researching Education and the Environment; Reid, A., Scott, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 37–48. [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. Sustainable living, ecological literacy, and the breath of life. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 12, 9–18.

- Meinherz, F.; Fritz, L.; Schneider, F. How values play into sustainability assessments: Challenges and a possible way forward. In Sustainability Assessments of Urban Systems; Binder, C.R., Wyss, R., Massaro, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 65–86. [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.W. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994.

- Jordan, R.; Singer, F.; Vaughan, J.; Berkowitz, A. What should every citizen know about ecology? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 495–500. [CrossRef]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014.

- Fia, M.; Ghasemzadeh, K.; Paletta, A. How higher education institutions walk their talk on the 2030 agenda: A systematic literature review. High. Educ. Policy 2022, 35, 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A.; Heiss, J. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [CrossRef]

- McLean, M.; Phelps, C.; Smith, J.; Maheshwari, N.; Veer, V.; Bushell, D.; Moro, C. An authentic learner-centered approach to climate and health education. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1049932. [CrossRef]

- Pleschová, G. Student-centred learning and reflective teaching. In The Long-Term Effects of Educational Development Programmes: Collaboration, Trust and Leadership; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Finale, R. Can we raise the level of environmental awareness through art? Soc. Educ. Res. 2025, 6, 147–163. [CrossRef]

- Hannigan, S.; Hradsky, D.; Bellingham, R.; Raphael, J.; White, P.J. Reimagining climate change futures: A review of arts-based education programs. Futures 2025, 153, 103667. [CrossRef]

- Illeris, K. A comprehensive understanding of human learning. In Contemporary Theories of Learning; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–14.

- Koul, S.; Nayar, B. The holistic learning educational ecosystem: A classroom 4.0 perspective. High. Educ. Q. 2021, 75, 98–112. [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Beyond Unreasonable Doubt: Education and Learning for Socio-Ecological Sustainability in the Anthropocene; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015.

- Ignelzi, M. Meaning-making in the learning and teaching process. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2000, 82, 5–14.

- Kress, G. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2010.

- Eisner, E.W. The Arts and the Creation of Mind; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2002.

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F., Jr. Speaking of art as embodied imagination: A multisensory approach to understanding aesthetic experience. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 259–282. [CrossRef]

- Ammentorp, L. Imagining social change: Developing social consciousness in an arts-based pedagogy. Outlines Crit. Pract. Stud. 2007, 9, 38–52.

- Wagner, E.; Nielsen, C.S.; Veloso, L.; Suominen, A.; Pachova, N. Arts, Sustainability and Education; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.K. Re-discovering the arts: The impact of engagement in a natural environment upon pre-service teacher perceptions of creativity. Think. Skills Creat. 2013, 8, 102–108. [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, L. The arts and education for sustainability: Shaping student teachers’ identities towards sustainability. In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability; Davis, J., Elliott, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 266–279. [CrossRef]

- Demos, T.J. Contemporary art and the politics of ecology: An introduction. Third Text 2013, 27, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.; Martusewicz, R.A. Introduction: Contemporary art as critical, revitalizing, and imaginative practice toward sustainable communities. In Art, EcoJustice, and Education; Foster, R., Mäkelä, J., Martusewicz, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–9.

- Albareda-Tiana, S.; Vidal-Raméntol, S.; Pujol-Valls, M.; Fernández-Morilla, M. Holistic approaches to develop sustainability and research competencies in pre-service teacher training. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3698. [CrossRef]

- Barone, T.; Eisner, E. Arts-based educational research. In Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 95–109.

- Leavy, P. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Boden, Z.; Eatough, V. Understanding more fully: A multimodal hermeneutic–phenomenological approach. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014, 11, 160–177.

- Bal, M.; Bryson, N. Semiotics and art history. Art Bull. 1991, 73, 174–208.

- O’Toole, M. The Hermeneutic Spiral and Interpretation in Literature and the Visual Arts; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Horcea-Milcu, A.I.; Abson, D.J.; Apetrei, C.I.; Duse, I.A.; Freeth, R.; Riechers, M.; Lang, D.J. Values in transformational sustainability science: Four perspectives for change. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1425–1437. [CrossRef]

- Sunassee, A.; Bokhoree, C.; Patrizio, A. Students’ empathy for the environment through eco-art place-based education: A review. Ecologies 2021, 2, 214–247. [CrossRef]

- Tomljenović, Z. Ecological thinking—Learning new values through visual arts education. In Ecology in the Concept of Broader Social Change; Duh, M., Ambrožič-Dolinšek, J., Eds.; University of Maribor, Faculty of Education; RIS Dvorec: Maribor, Slovenia, 2016; pp. 298–312.

- Ojala, M. Facing anxiety in climate change education: From therapeutic practice to hopeful transgressive learning. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 41–56.

- Bloodhart, B.; Swim, J.K.; Dicicco, E. “Be worried, be VERY worried”: Preferences for and impacts of negative emotional climate change communication. Front. Commun. 2019, 3, 63. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Gustafson, A.; Jensen, R. Framing climate change: Exploring the role of emotion in generating advocacy behavior. Sci. Commun. 2018, 40, 442–468. [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, L.; Rushton, E.A. Education for environmental sustainability and the emotions: Implications for educational practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4441. [CrossRef]

- Inwood, H. Cultivating artistic approaches to environmental learning: Exploring eco-art education in elementary classrooms. Int. Electron. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 3, 129–145.

- Clarke, A.; Hulbert, S. Envisioning the future: Working toward sustainability in fine art education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2016, 35, 36–50. [CrossRef]

- Jónsdóttir, Á.B. Artistic Actions for Sustainability: Potential of Art in Education for Sustainability; Lapland University Press: Rovaniemi, Finland, 2017.

- Bürgener, L.; Barth, M. Sustainability competencies in teacher education: Making teacher education count in everyday school practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 821–826. [CrossRef]

- Fan, H. Integrating ecological consciousness into environmental art design education: Impacts on student engagement, sustainability practices, and critical thinking. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 6549–6572. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Unlocking futures literacy: Essential skills for students for an evolving world. Cogent Educ. 2025, 12, 2588021. [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, J.; Benati, K.; Beamish, A.; Guy, M.; Interrigi, F. Enhancing critical and creative thinking in sustainability education through reflective practice and project-based learning. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2026, 24, 101364. [CrossRef]

- Shutaleva, A. Ecological culture and critical thinking: Building of a sustainable future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13492. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Transformative learning and sustainability: Sketching the conceptual ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 5, 17–33.

- Horvath, S.M.; Payerhofer, U.; Wals, A.; Gratzer, G. The art of arts-based interventions in transdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 547–563. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).