Submitted:

28 January 2026

Posted:

29 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vitro Culture of Host Cells and Parasites

2.1.1. T. gondii in Human Fibroblasts

2.1.2. Leishmania Promastigotes

2.2. Chemicals and Radiochemicals

2.3. Drug Sensitivity Assay for T. gondii Tachyzoites

2.4. Drug Cytotoxicity Assay for HFF Cells Using Alamar Blue Dye

2.5. Transport Assays

2.6. Plasmid Construction and Expression of TgENT1 in L. mexicana NT3-KO

2.7. CRISPR-Mediated Gene Disruption in T. gondii Tachyzoites

2.7.1. Direct Gene Knockout

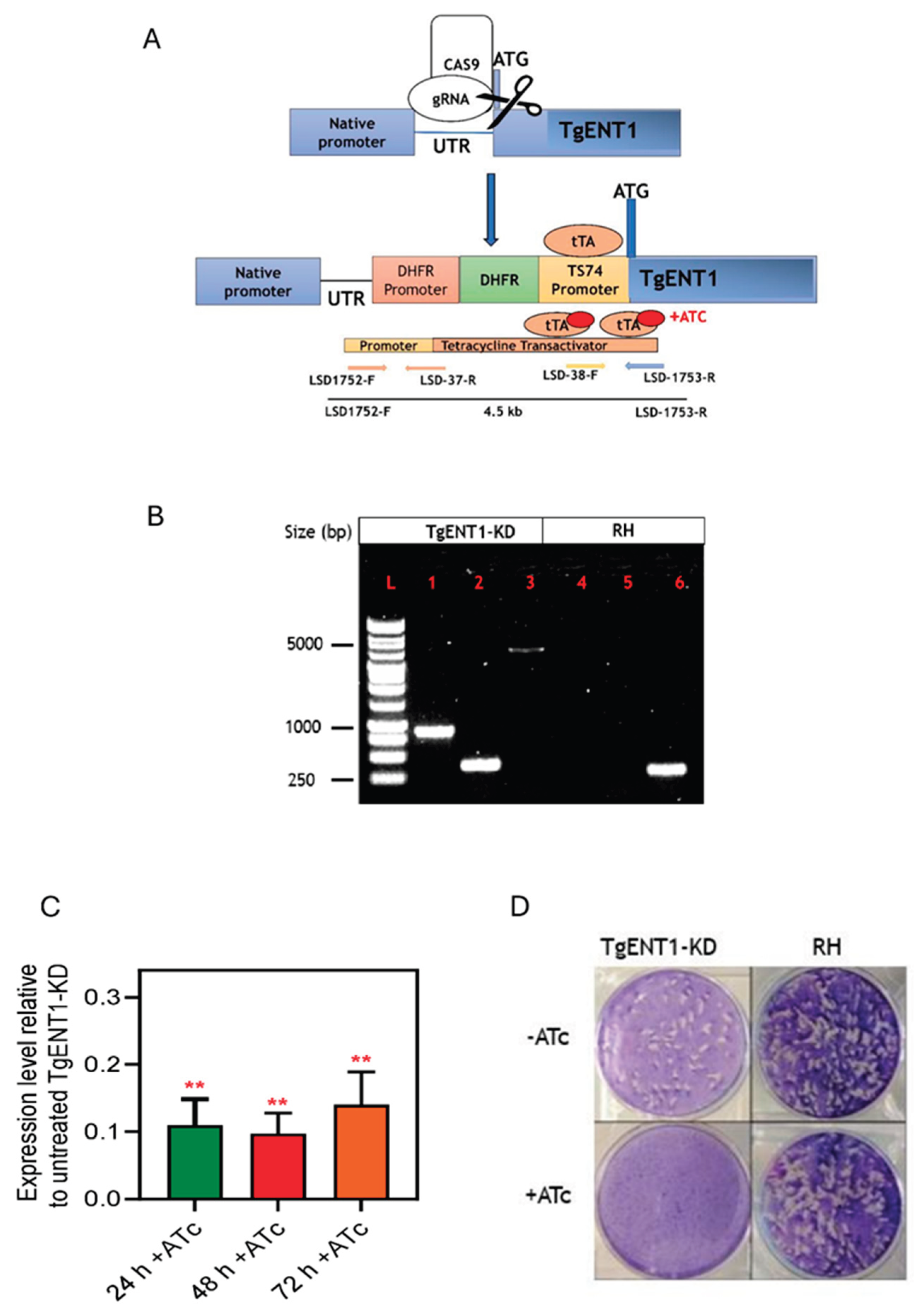

2.7.2. Gene Knockdown (Tetracycline-Inducible Transactivator System)

2.7.3. Transfection and Selection

2.7.4. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting

2.8. Plaque Assay

2.9. Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR) in T. gondii Tachyzoites

2.10. qRT-PCR for L. mexicana Promastigotes

3. Results

3.1. Creation of TgENT Knockout (KO) and Knockdown (KD) Strains

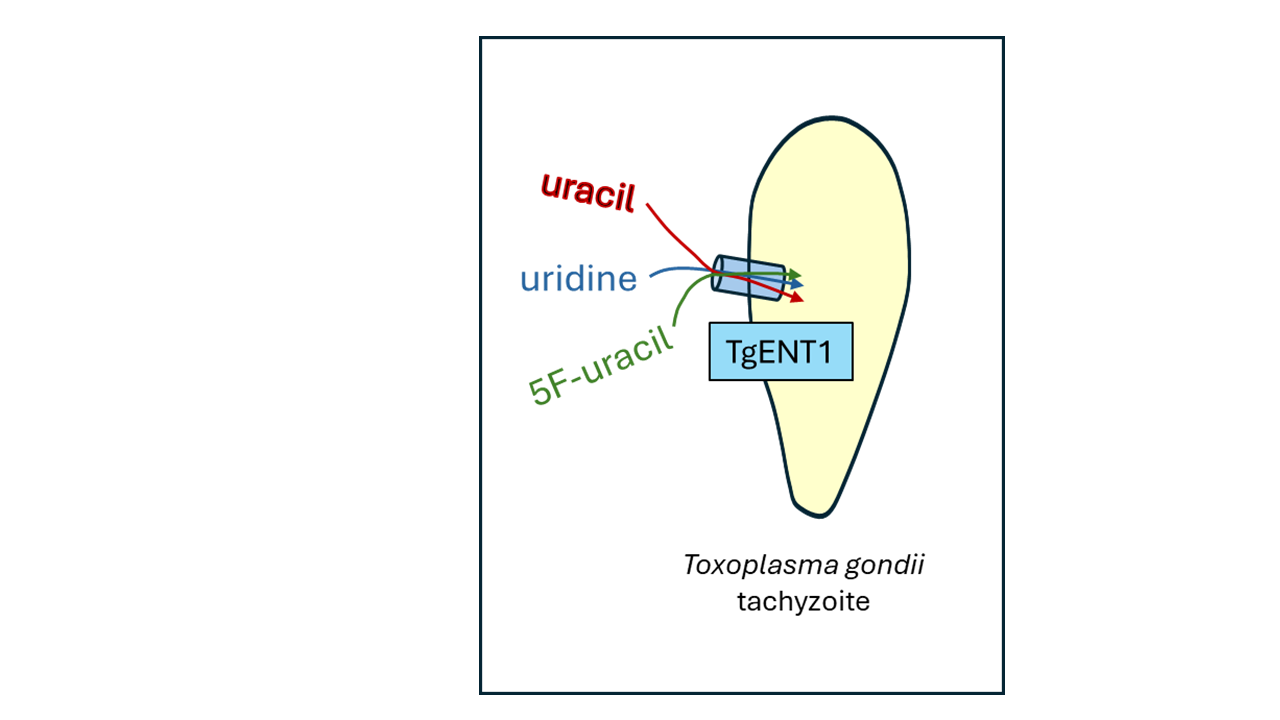

3.1.1. Identification of Toxoplasma ENTs

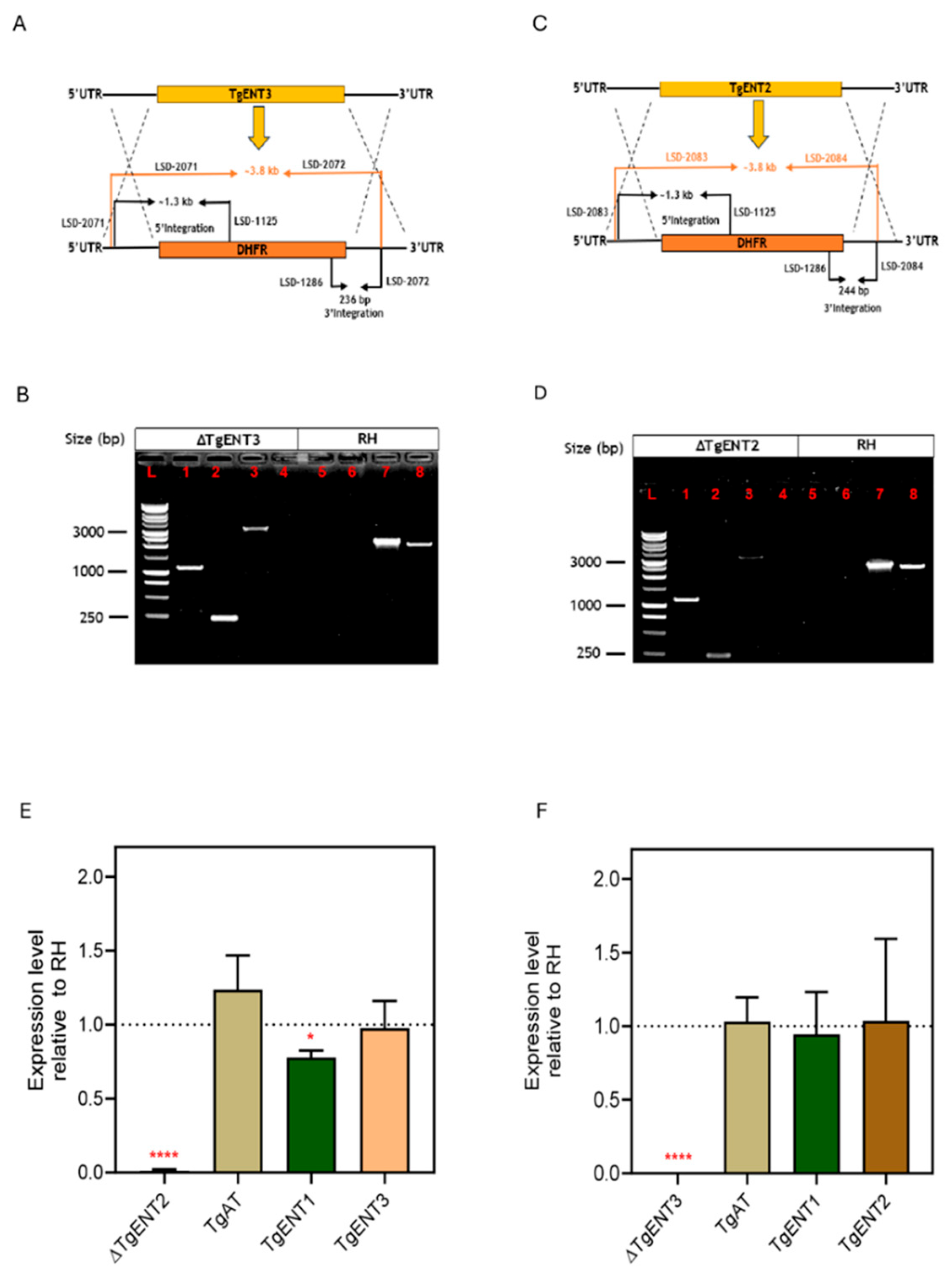

3.1.2. Construction of TgENT2 and TgENT3 Knockouts in T. gondii RH Cell Line

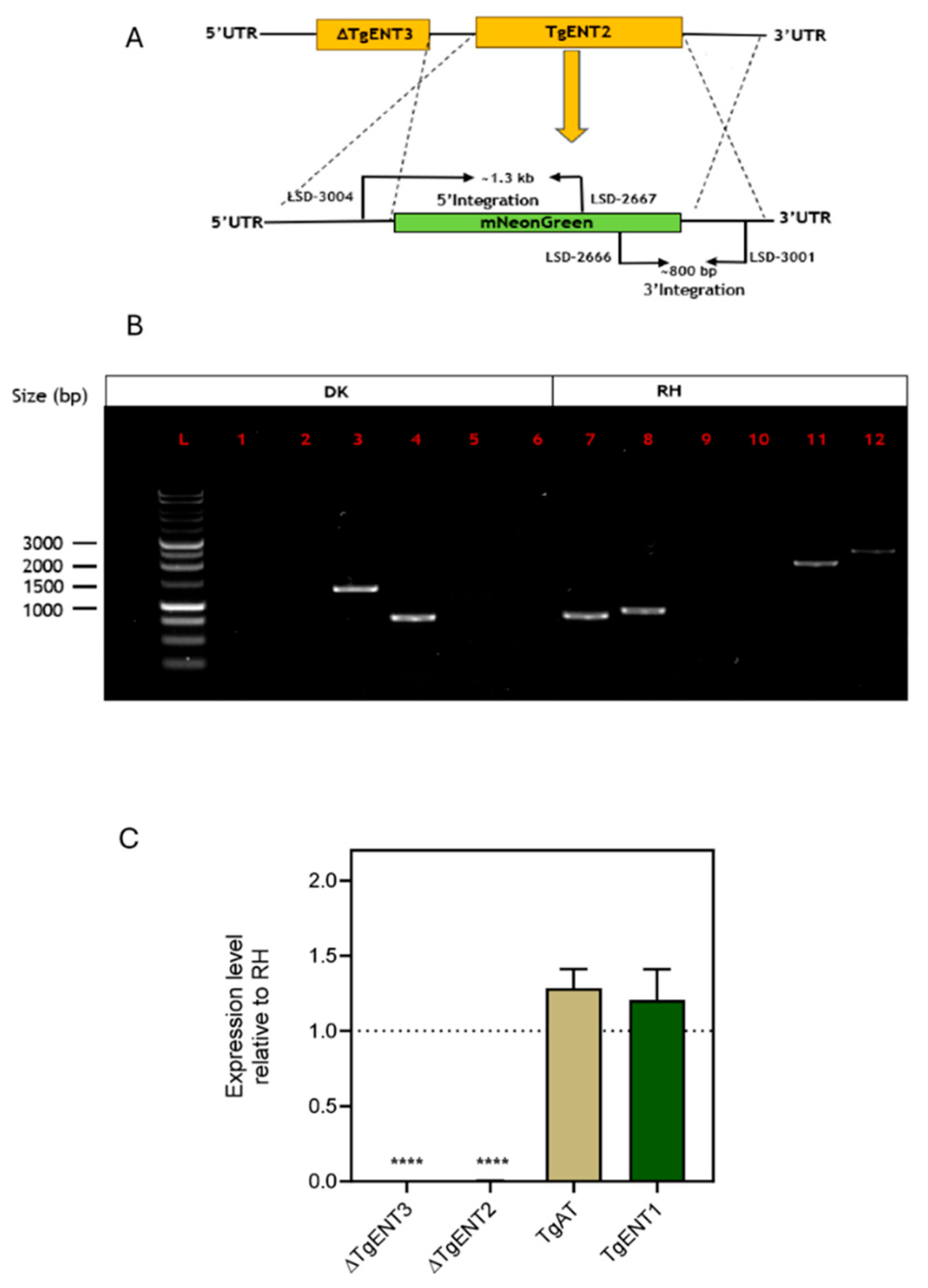

3.1.3. Creation of a TgENT2/3 Double Knockout Cell Line (ENT2/3dKO)

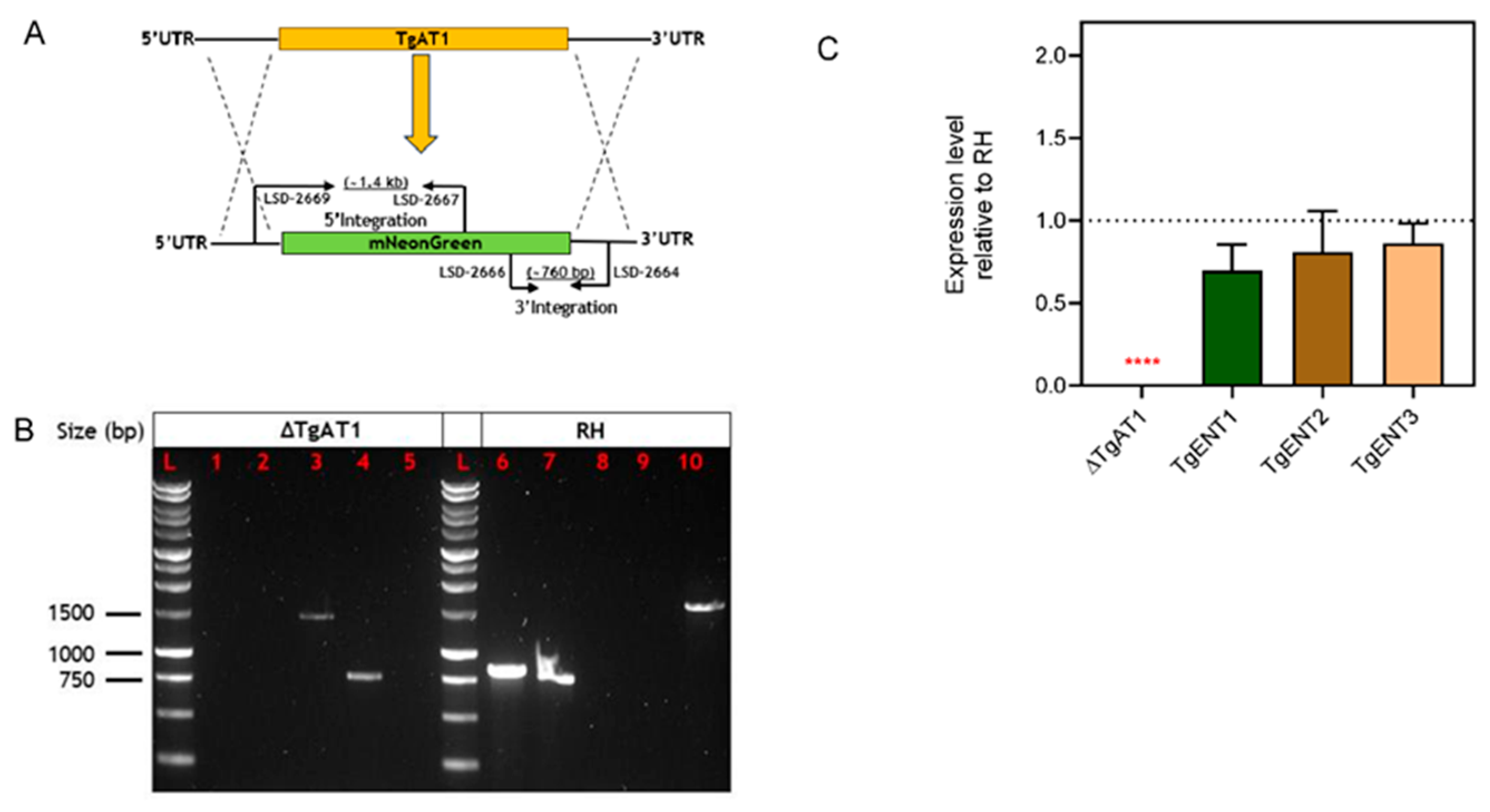

3.1.4. Deletion of TgAT1 in the RH Cell Line

3.1.5. Creation of a Conditional Knockout of TgENT1

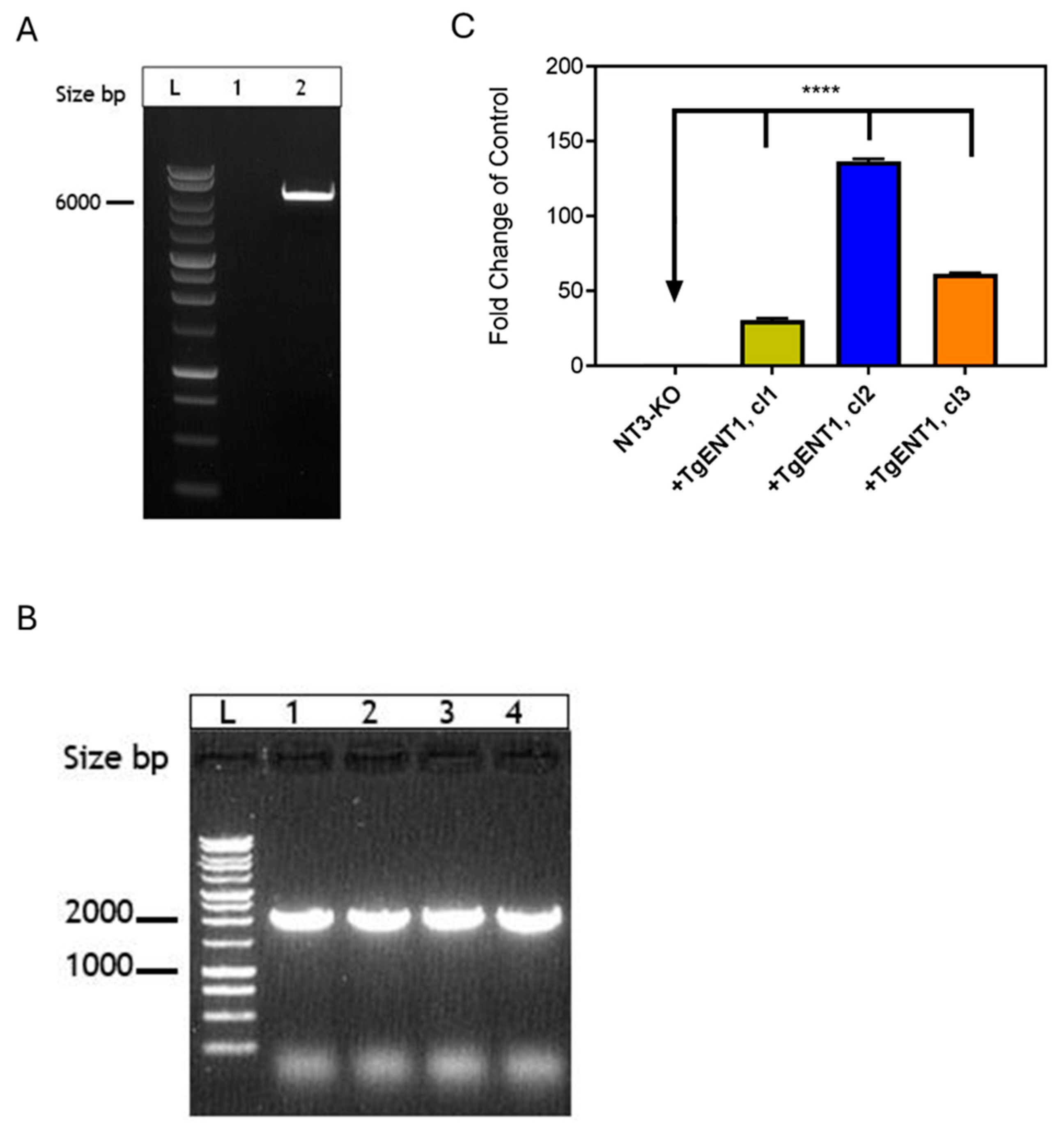

3.1.6. Expression of TgENTs in a Leishmania Mexicana Cell Line Deficient in Nucleobase Transport

3.2. Investigation into the Physiological Role of the TgENT Transporters

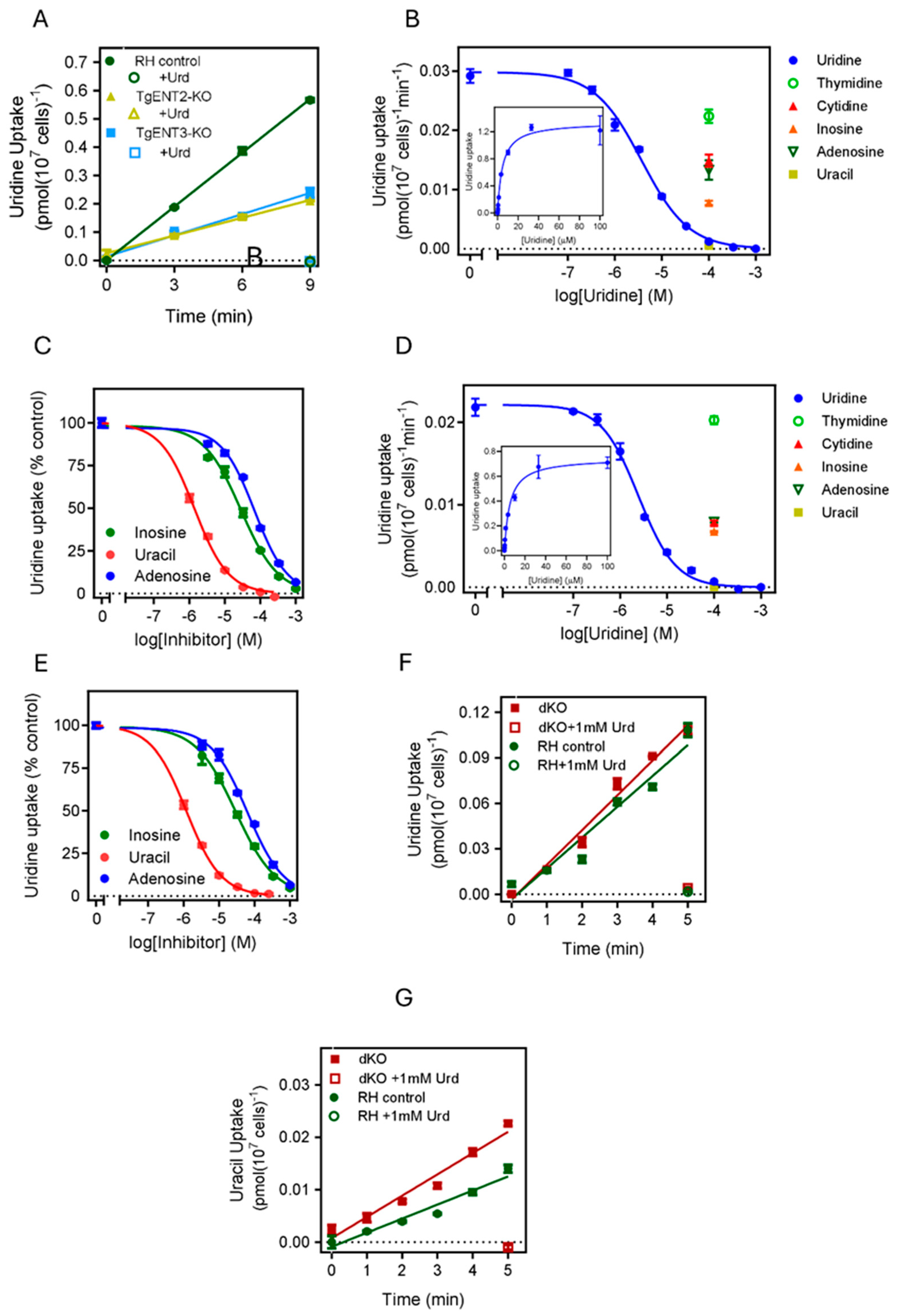

3.2.1. Is TgENT2 or TgENT3 Involved in Pyrimidine Uptake in T. gondii?

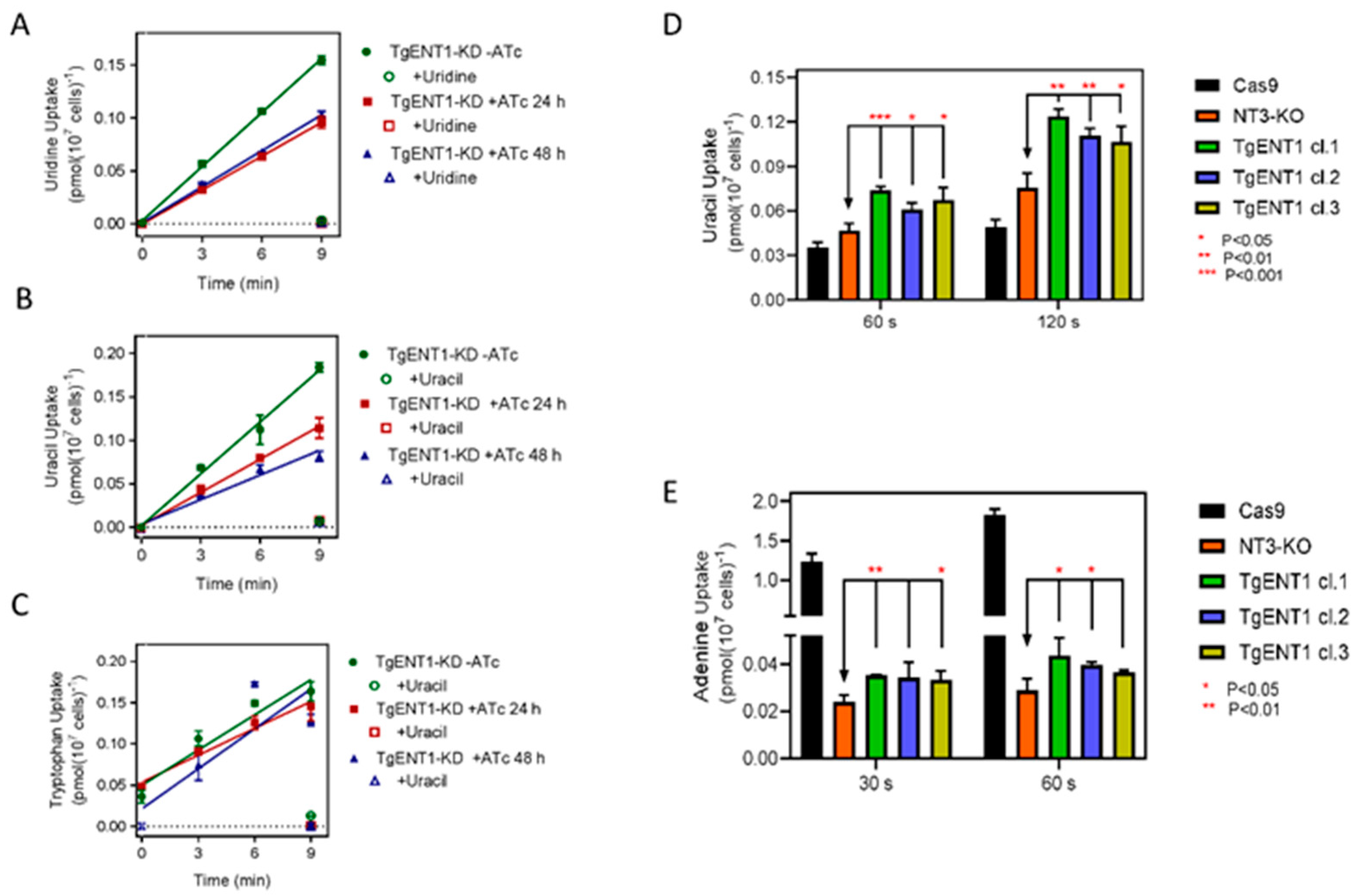

3.2.2. Investigating the Role of TgENT1 in Pyrimidine Transport

3.3. Effect of Transporter Knockouts on Sensitivity to 5-Fluorinated Pyrimidines

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ENT | Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter |

| TgUUT1 | Toxoplasma gondii Uracil/Uridine Transporter 1 |

| TgAT1 | Toxoplasma gondii Adenosine Transporter 1 |

References

- Dubey, J.; Murata, F.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.; Kwok, O.; Villena, I. Congenital toxoplasmosis in humans: an update of worldwide rate of congenital infections. Parasitology 2021, 148, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.G.; Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004, 363, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan. Int J Parasitol 2004, 34, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothroyd, J.C. Expansion of host range as a driving force in the evolution of Toxoplasma. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kouni, M.H.; Guarcello, V.; Al Safarjalani, O.N.; Naguib, F.N. Metabolism and selective toxicity of 6-nitrobenzylthioinosine in Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counihan, N.A.; Modak, J.K.; de Koning-Ward, T.F. How malaria parasites acquire nutrients from their host. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 649184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.; Beckers, C.; Joiner, K. The parasitophorous vacuole membrane surrounding intracellular Toxoplasma gondii functions as a molecular sieve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, M.A.; Gaete, P.S.; Swale, C.; Maru, P.; Contreras, J.E.; Saeij, J.P.J. Two Toxoplasma gondii putative pore-forming proteins, GRA47 and GRA72, influence small molecule permeability of the parasitophorous vacuole. mBio 2024, 15, e0308123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, R.L.; Krug, E.C.; Marr, J.J. Purine and pyrimidine metabolism. In Biochemistry and molecular biology of parasites; Elsevier, 1995; pp. 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, H.M.; Ngo, E.O.; Bzik, D.J.; Joiner, K.A. Toxoplasma gondii: are host cell adenosine nucleotides a direct source for purine salvage? Exp Parasitol 2000, 95, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, H.P.; Al-Salabi, M.I.; Cohen, A.M.; Coombs, G.H.; Wastling, J.M. Identification and characterisation of high affinity nucleoside and nucleobase transporters in Toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol 2003, 33, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.A.; Bzik, D.J. De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 2002, 415, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elati, H.A.; Goerner, A.L.; Martorelli Di Genova, B.; Sheiner, L.; De Koning, H.P. Pyrimidine salvage in Toxoplasma gondii as a target for new treatment. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2023, 13, 1320160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnaro, G.D.; De Koning, H.P. Purine and pyrimidine transporters of pathogenic protozoa–conduits for therapeutic agents. Medicinal Research Reviews 2020, 40, 1679–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natto, M.J.; Miyamoto, Y.; Munday, J.C.; AlSiari, T.A.; Al-Salabi, M.I.; Quashie, N.B.; Eze, A.A.; Eckmann, L.; De Koning, H.P. Comprehensive characterization of purine and pyrimidine transport activities in Trichomonas vaginalis and functional cloning of a trichomonad nucleoside transporter. Mol Microbiol 2021, 116, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldfer, M.M.; Alfayez, I.A.; Elati, H.A.; Gayen, N.; Elmahallawy, E.K.; Milena Murillo, A.; Marsiccobetre, S.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Silber, A.M.; De Koning, H.P. The Trypanosoma cruzi TcrNT2 Nucleoside Transporter Is a Conduit for the Uptake of 5-F-2′-Deoxyuridine and Tubercidin Analogues. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungogo, M.A.; Aldfer, M.M.; Natto, M.J.; Zhuang, H.; Chisholm, R.; Walsh, K.; McGee, M.; Ilbeigi, K.; Asseri, J.I.; Burchmore, R.J.S.; et al. Cloning and Characterization of Trypanosoma congolense and T. vivax Nucleoside Transporters Reveal the Potential of P1-Type Carriers for the Discovery of Broad-Spectrum Nucleoside-Based Therapeutics against Animal African Trypanosomiasis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.D. The SLC28 (CNT) and SLC29 (ENT) nucleoside transporter families: a 30-year collaborative odyssey. Biochem Soc Trans 2016, 44, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delespaux, V.; de Koning, H.P. Transporters in Anti-Parasitic Drug Development and Resistance. In Trypanosomatid diseases: molecular routes to drug discovery; Jäger, T., Koch, O., Flohe, L., Eds.; 2013; pp. 335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Munday, J.C.; Settimo, L.; de Koning, H.P. Transport proteins determine drug sensitivity and resistance in a protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma brucei. Front Pharmacol 2015, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunay, I.R.; Gajurel, K.; Dhakal, R.; Liesenfeld, O.; Montoya, J.G. Treatment of Toxoplasmosis: Historical Perspective, Animal Models, and Current Clinical Practice. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodenkova, S.; Buchler, T.; Cervena, K.; Veskrnova, V.; Vodicka, P.; Vymetalkova, V. 5-fluorouracil and other fluoropyrimidines in colorectal cancer: Past, present and future. Pharmacol Ther 2020, 206, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiver, C.; Milandre, C.; Poizot-Martin, I.; Drogoul, M.P.; Gastaut, J.L.; Gastaut, J.A. 5-Fluoro-uracil-clindamycin for treatment of cerebral toxoplasmosis. AIDS 1993, 7, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.W.; Carter, N.; Sullivan, W.J., Jr.; Donald, R.G.; Roos, D.S.; Naguib, F.N.; el Kouni, M.H.; Ullman, B.; Wilson, C.M. The adenosine transporter of Toxoplasma gondii. Identification by insertional mutagenesis, cloning, and recombinant expression. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 35255–35261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnaro, G.D.; Elati, H.A.A.; Balaska, S.; Martin Abril, M.E.; Natto, M.J.; Hulpia, F.; Lee, K.; Sheiner, L.; Van Calenbergh, S.; de Koning, H.P. A Toxoplasma gondii Oxopurine Transporter Binds Nucleobases and Nucleosides Using Different Binding Modes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, G.; Goerner, A.; Bennett, C.; Brennan, E.; Carruthers, V.B.; Martorelli Di Genova, B. Impact of equilibrative nucleoside transporters on Toxoplasma gondii infection and differentiation. mBio 2025, 16, e0220725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, K.J.; Aliota, M.T.; Knoll, L.J. Dual transcriptional profiling of mice and Toxoplasma gondii during acute and chronic infection. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheiner, L.; Demerly, J.L.; Poulsen, N.; Beatty, W.L.; Lucas, O.; Behnke, M.S.; White, M.W.; Striepen, B. A systematic screen to discover and analyze apicoplast proteins identifies a conserved and essential protein import factor. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, e1002392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneke, T.; Madden, R.; Makin, L.; Valli, J.; Sunter, J.; Gluenz, E. A CRISPR Cas9 high-throughput genome editing toolkit for kinetoplastids. R Soc Open Sci 2017, 4, 170095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabli, A.M.M. Polyomic analyses for rational antileishmanial vaccine development: a role for membrane transporters? PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aldfer, M.M.; AlSiari, T.A.; Elati, H.A.A.; Natto, M.J.; Alfayez, I.A.; Campagnaro, G.D.; Sani, B.; Burchmore, R.J.S.; Diallinas, G.; De Koning, H.P. Nucleoside Transport and Nucleobase Uptake Null Mutants in Leishmania mexicana for the Routine Expression and Characterization of Purine and Pyrimidine Transporters. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Salabi, M.I.; Wallace, L.J.; De Koning, H.P. A Leishmania major nucleobase transporter responsible for allopurinol uptake is a functional homolog of the Trypanosoma brucei H2 transporter. Mol Pharmacol 2003, 63, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldfer, M.M.; Hulpia, F.; van Calenbergh, S.; De Koning, H.P. Mapping the transporter-substrate interactions of the Trypanosoma cruzi NB1 nucleobase transporter reveals the basis for its high affinity and selectivity for hypoxanthine and guanine and lack of nucleoside uptake. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2024, 258, 111616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetaud, E.; Lecuix, I.; Sheldrake, T.; Baltz, T.; Fairlamb, A.H. A new expression vector for Crithidia fasciculata and Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2002, 120, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt-Varesano, A.; Braun, L.; Ranquet, C.; Hakimi, M.A.; Bougdour, A. The aspartyl protease TgASP5 mediates the export of the Toxoplasma GRA16 and GRA24 effectors into host cells. Cell Microbiol 2016, 18, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghabi, D.; Sloan, M.; Gill, G.; Hartmann, E.; Antipova, O.; Dou, Z.; Guerra, A.J.; Carruthers, V.B.; Harding, C.R. The vacuolar iron transporter mediates iron detoxification in Toxoplasma gondii. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufermann, C.M.; Muller, F.; Frohnecke, N.; Laue, M.; Seeber, F. Toxoplasma gondii plaque assays revisited: Improvements for ultrastructural and quantitative evaluation of lytic parasite growth. Exp Parasitol 2017, 180, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovciarikova, J.; Shikha, S.; Lacombe, A.; Courjol, F.; McCrone, R.; Hussain, W.; Maclean, A.; Lemgruber, L.; Martins-Duarte, E.S.; Gissot, M.; et al. Two ancient membrane pores mediate mitochondrial-nucleus membrane contact sites. J Cell Biol 2024, 223, e202304075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclean, A.E.; Sloan, M.A.; Renaud, E.A.; Argyle, B.E.; Lewis, W.H.; Ovciarikova, J.; Demolombe, V.; Waller, R.F.; Besteiro, S.; Sheiner, L. The Toxoplasma gondii mitochondrial transporter ABCB7L is essential for the biogenesis of cytosolic and nuclear iron-sulfur cluster proteins and cytosolic translation. MBio 2024, 15, e00872-00824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.A.; Tagoe, D.N.; Munday, J.C.; Donachie, A.; Morrison, L.J.; De Koning, H.P. Pyrimidine biosynthesis is not an essential function for Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms. Plos one 2013, 8, e58034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.; Szallies, A.; Rawer, M.; Echner, H.; Duszenko, M. GPI anchor transamidase of Trypanosoma brucei: in vitro assay of the recombinant protein and VSG anchor exchange. J Cell Sci 2002, 115, 2529–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, H.P.; Bridges, D.J.; Burchmore, R.J. Purine and pyrimidine transport in pathogenic protozoa: from biology to therapy. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2005, 29, 987–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K. Purine transport and salvage in apicomplexan parasites. Ph.D thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; He, Z.; He, M.; Chen, C.; Luo, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Fang, R. A nucleoside transporter on the mitochondria of T. gondii is essential for maintaining normal growth of the parasite. Parasites & Vectors 2025, 18, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik, S.M.; Huet, D.; Ganesan, S.M.; Huynh, M.H.; Wang, T.; Nasamu, A.S.; Thiru, P.; Saeij, J.P.J.; Carruthers, V.B.; Niles, J.C.; et al. A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen in Toxoplasma Identifies Essential Apicomplexan Genes. Cell 2016, 166, 1423–1435 e1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, M.; Schluter, D.; Soldati, D. Role of Toxoplasma gondii myosin A in powering parasite gliding and host cell invasion. Science 2002, 298, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, A.; Maclean, A.E.; Ovciarikova, J.; Tottey, J.; Muhleip, A.; Fernandes, P.; Sheiner, L. Identification of the Toxoplasma gondii mitochondrial ribosome, and characterisation of a protein essential for mitochondrial translation. Mol Microbiol 2019, 112, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, B.A.; Belperron, A.A.; Bzik, D.J. Negative selection of Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2001, 116, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, D.B.; Harkin, D.P.; Johnston, P.G. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, P.K.; Khatri, A.; Hubbert, T.; Milhous, W.K. Selective activity of 5-fluoroorotic acid against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989, 33, 1090–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, W.; Trigg, P. Incorporation of radioactive precursors into DNA and RNA of Plasmodium knowlesi in vitro. The J Protozool 1970, 17, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyke, K.; Tremblay, G.C.; Lantz, C.H.; Szustkiewicz, C. The source of purines and pyrimidines in Plasmodium berghei. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1970, 19, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, H.; Diallinas, G. Nucleobase transporters. Mol Membr Biol 2000, 17, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, I.G.; Yakob, L.; Al Salabi, M.I.; Diallinas, G.; Soteriadou, K.P.; De Koning, H.P. Identification of the first pyrimidine nucleobase transporter in Leishmania: similarities with the Trypanosoma brucei U1 transporter and antileishmanial activity of uracil analogues. Parasitology 2005, 130, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, H.P.; Jarvis, S.M. A highly selective, high-affinity transporter for uracil in Trypanosoma brucei brucei: evidence for proton-dependent transport. Biochem Cell Biol 1998, 76, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudin, S.; Quashie, N.B.; Candlish, D.; Al-Salabi, M.I.; Jarvis, S.M.; Ranford-Cartwright, L.C.; de Koning, H.P. Trypanosoma brucei: a survey of pyrimidine transport activities. Exp Parasitol 2006, 114, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, H.P. Pyrimidine transporters of trypanosomes–a class apart? Trends in Parasitology 2007, 23, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.A.M. Pyrimidine salvage and metabolism in kinetoplastid parasites; University of Glasgow, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani, K.J.H. Strategies for the identification and cloning of genes encoding pyrimidine transporters of Leishmania and Trypanosoma species. Ph.D thesis, University of Glasgow, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ritt, J.F.; Raymond, F.; Leprohon, P.; Legare, D.; Corbeil, J.; Ouellette, M. Gene amplification and point mutations in pyrimidine metabolic genes in 5-fluorouracil resistant Leishmania infantum. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013, 7, e2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T gondii Gene ID | Name | bp (no introns) | a.a. | TMD* | Qian et al | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGME49 | TGGT1 | |||||

| 244440 | 244440 | TgAT1 | 1389 | 462 | 10 | TgAT1 |

| 288540 | 288540 | TgENT1 | 2091 | 696 | 10 | TgNT1 |

| 500147 | 359630 | TgENT2 | 2007 | 668 | 10 | TgNT3 |

| 233130 | 233130 | TgENT3 | 1596 | 531 | 10 | TgNT2 |

| TgENT2-KO | TgENT3-KO | RH1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km | 5.29 ± 0.58 | 3.78 ± 0.92 | 3.34 ± 0.82 | µM |

| Vmax | 0.025 ± 0.002 | 0.011 ± 0.002 | 0.020 ± 0.004 | pmol(107 cells)-1min-1 |

| Uracil Ki | 0.96 ± 0.17 | 1.06 ± 0.14 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | µM |

| Inosine Ki | 32.2 ± 3.3 | 37.7 ± 3.82 | 28.2 ± 4.1 | µM |

| Adenosine Ki | 77.4 ± 10.7 | 58.9 ± 1.10* | 111 ± 6 | µM |

| ID | RH | TgAT1-KO | TgENT2-KO | TgENT3-KO | TgENT2/3dKO | HFF cytotoxicity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 ± SEMa | EC50 ± SEM | P b | EC50 ± SEM | P b | EC50 ± SEM | P b | EC50 ± SEM | P b | EC50 Cytostatica |

EC50 Cytocidala |

SI | |

| 5-FU | 1.13 ± 0.16 | 0.70 ± 0.21 | 0.17 | 1.36 ± 0.26 | 0.49 | 0.82 ± 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.49 ± 0.43 | 3074 ±339 | 2720 |

| 5-FUrd | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.11 ± 0.10 | 20.4 ± 1 | 45 |

| 5-F-2’dUrd | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 0.41 ± 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 1478 ± 512 | 2205 |

| Sulfadiazine | 12.4 ± 1.08 | 3.95 ± 0.29 | 0.0003 | 7.15 ± 0.19 | 0.01 | 8.12 ± 0.22 | 0.02 | 5.74 ± 0.29 | 0.004 | -- | -- | -- |

| PAO | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.06 ± 0.003 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).