Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

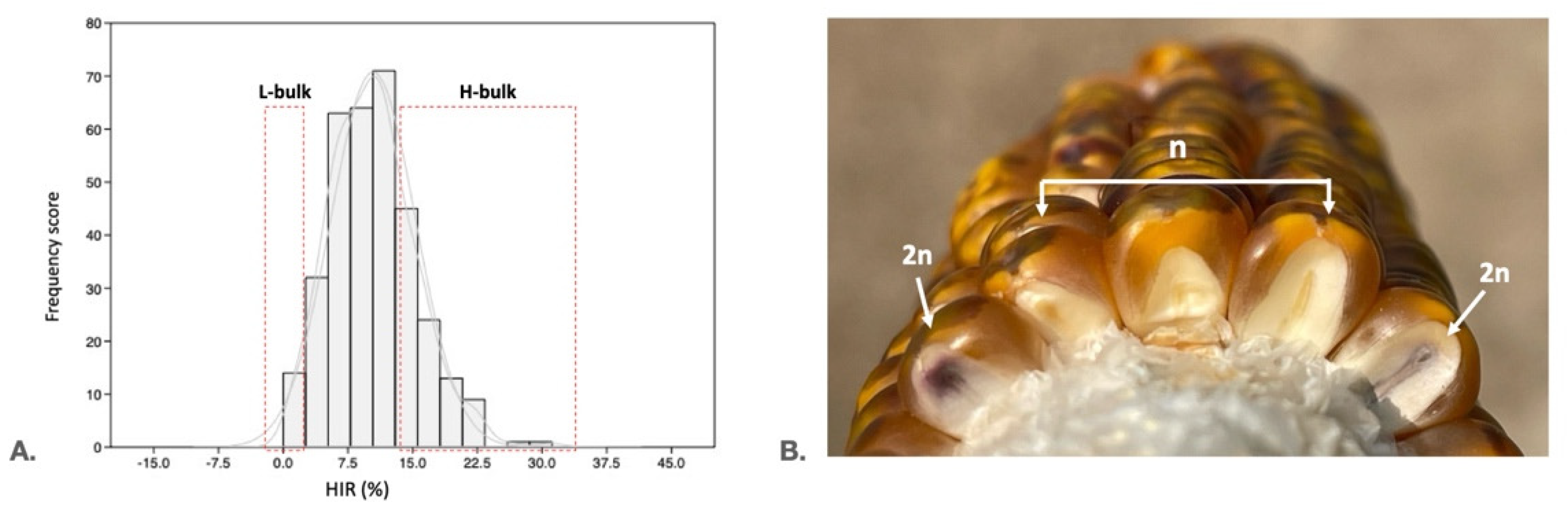

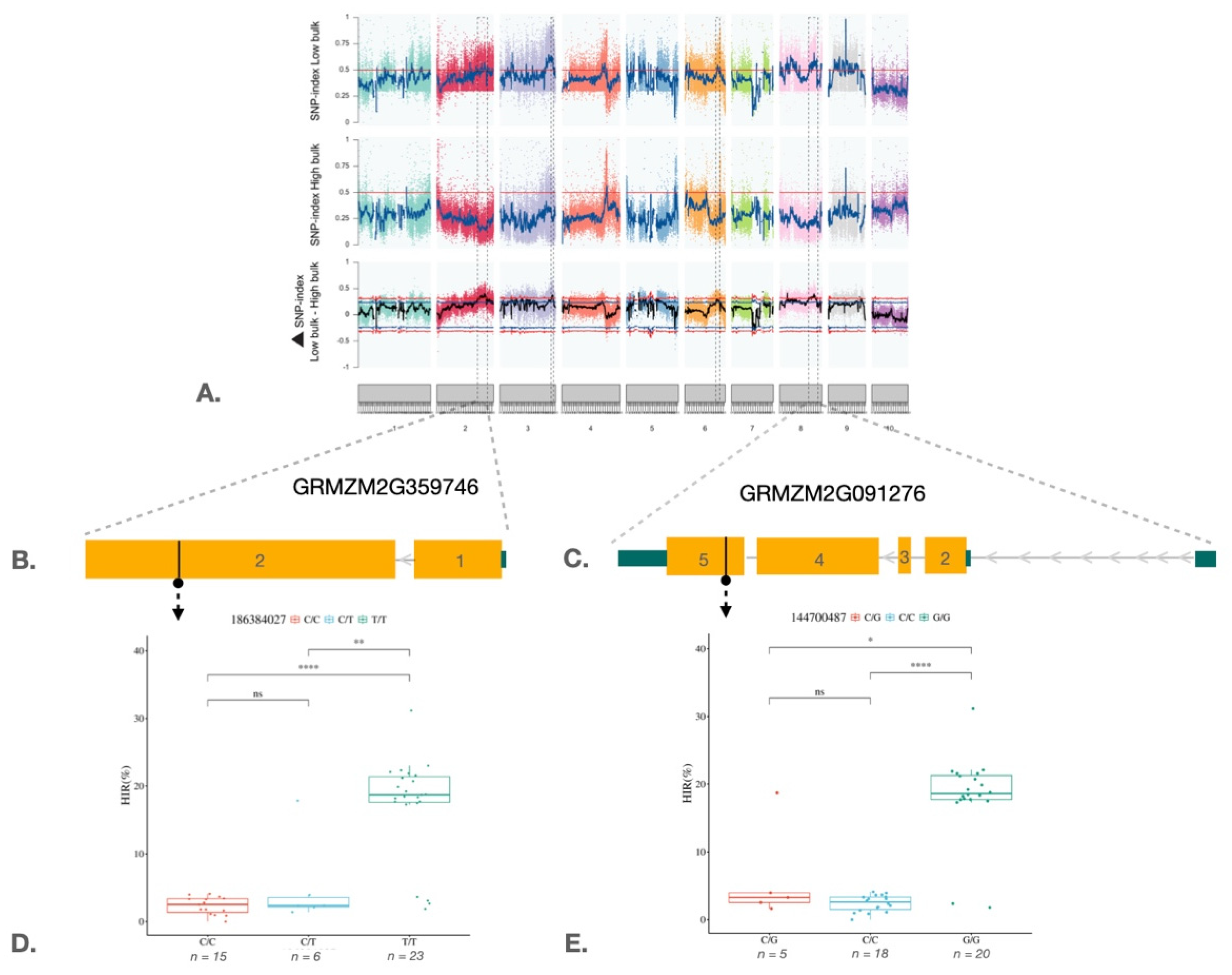

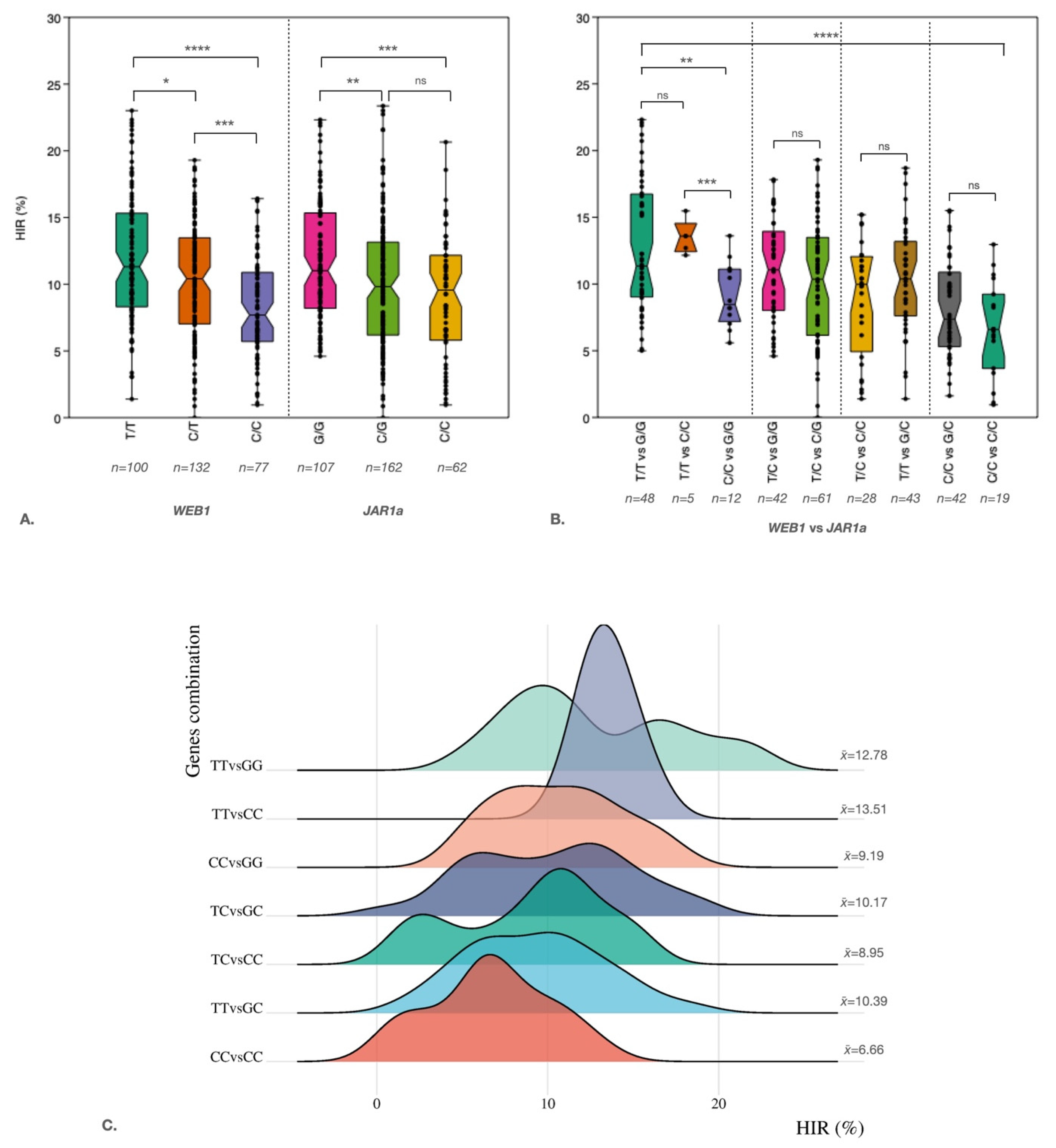

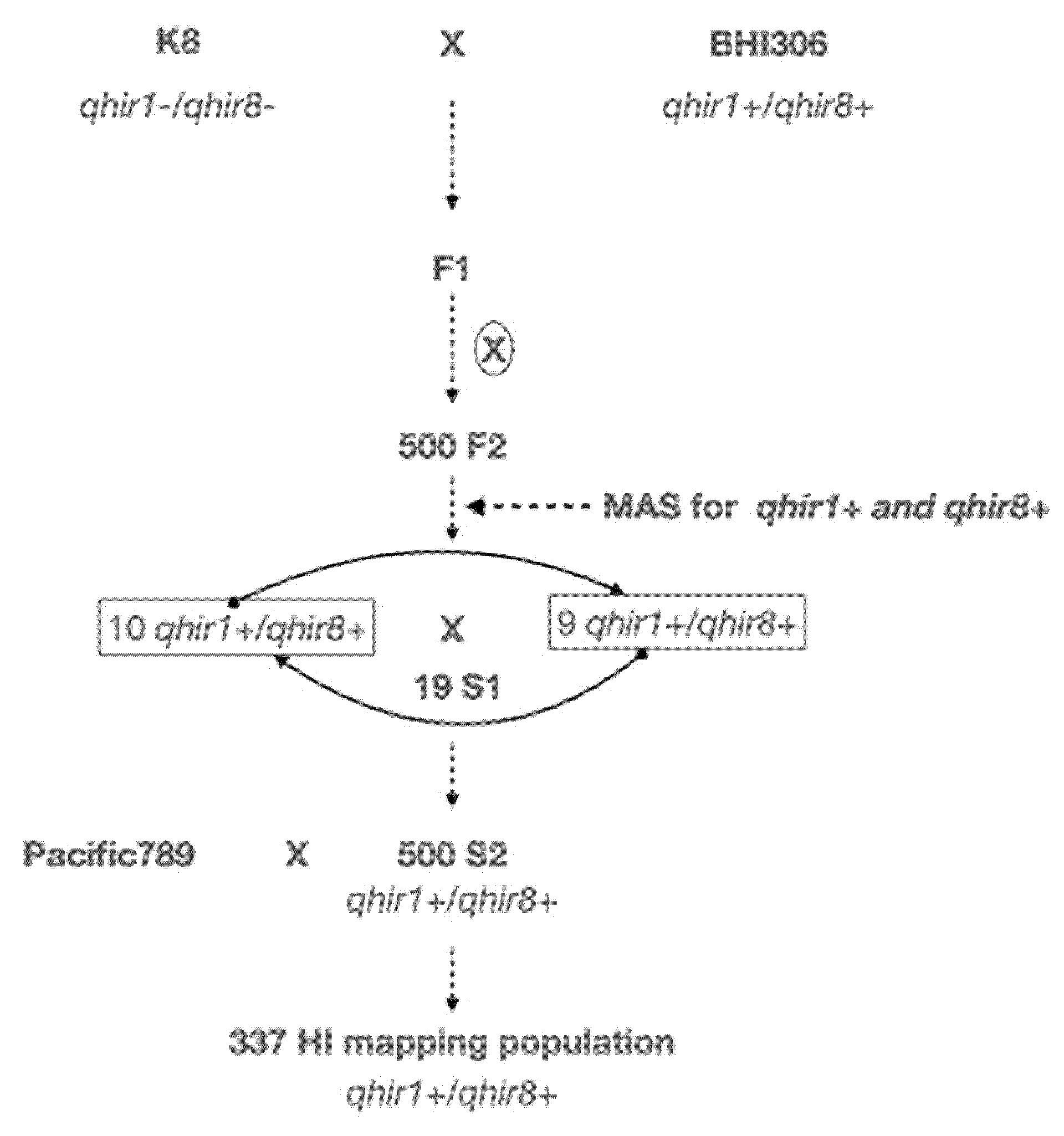

Double-haploid (DH) technology is a well-established method for speeding up the development of inbred lines in breeding programs. The major loci qhir1 and qhir8 are widely used in marker-assisted selection (MAS) to increase the haploid induction rate (HIR) in maize. However, previous studies have shown that HIR can be unstable within populations, even in the presence of these two loci. To identify novel loci associated with HIR, we performed QTL-seq analysis on 337 S2 haploid inducers (qhir1+/qhir8+) derived from crossing K8 with BHI306. The population exhibited HIR ranging from 0% to 31.16%. We sequenced bulked DNA from 30 extreme high-HIR lines (15.72-31.16%) and 30 extreme low-HIR lines (0-3.84%), identifying candidate intervals on chromosomes 2 (qHI2), 3 (qHI3), 6 (qHI6), and 8 (qHI8). Based on the QTL-seq results, 147 high-confidence SNPs/InDels (R² > 0.3) led to the analysis of 58 genes across three QTLs. We retrieved ten missense mutation SNPs from three genes (GRMZM2G359746 (qHI2), AC198725.4 (qHI3), and GRMZM2G091276 (qHI8)), which are located on chromosomes 2, 3, and 8. Regression analysis of these SNPs showed an R² range of 0.27 to 0.72. The two most highly associated SNPs were located in exon 2 of GRMZM2G359746 (qHI2) and in exon 5 of GRMZM2G091276 (qHI8), respectively. Marker-trait association analysis revealed that lines carrying favorable alleles at both loci, together with qhir1+ and qhir8+, exhibited significantly higher average HIR (12.77%) compared to those with unfavorable alleles (6.66%). These findings provide valuable markers for enhancing maternal haploid inducer breeding programs in maize.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotyping of the Mapping Population and Selection of Extremely High and Low HIR

2.2. Whole-Genome Resequencing, Sequence Processing, and Variant Calling

2.3. QTL-Seq Analysis and Marker Validation in the Maize Haploid Inducer Population

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and HIR Evaluation

4.2. Selection of Plants with Extremely High and Low Haploid Induction Rates, DNA Isolation and Whole-Genome Resequencing

4.3. Processing of Sequencing Data and QTL-seq Analysis

4.4. Design a Marker for HIR Validation

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DH | Double-Haploid |

| MAS | Marker-Assisted Selection |

| HIR | Haploid Induction Rate |

| QTL | Quantitative Trait Loci |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| MTL | MATRILINEAL |

| ZmPLA1 | Zea mays PHOSPHOLIPASE-A1 |

| NLD | NOT LIKE DAD |

| ZmDMP | Zea mays DUF679 domain membrane protein |

| ZmPLD3 | Zea mays PHOSPHOLIPASE D3 |

| ZmPOD65 | Zea mays Peroxidase65 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association |

| CENH3 | Centromeric Histone H3 |

| R1-nj | R1-Navajo |

| WEB1 | WEAK CHLOROPLAST MOVEMENT UNDER BLUE LIGHT 1 |

| JAR1a | Jasmonate-resistant 1 |

| PS I | photosystem I |

| PS II | photosystem II |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid |

| ACX | Acyl-CoA Oxidase |

| JA-Ile | Jasmonoyl-L-Isoleucine |

| PVE | Percentage of Variance |

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B. M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications. Food security 2022, 14(5), 1295–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Corn, U., Foreign Agricultural Service. 2021.

- Sprague, G. The experimental basis for hybrid maize. Biological Reviews 1946, 21(3), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Natsume, S.; Mitsuoka, C.; Uemura, A.; Utsushi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Takuno, S. QTL-seq: rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. The Plant Journal 2013, 74(1), 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Johar, P.; Raina, A.; Salgotra, R.; Feng, X.; Bhat, J. A. Harnessing the potential of bulk segregant analysis sequencing and its related approaches in crop breeding. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13, 944501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lee, J.-H.; Han, K.; Jang, S.; Han, J.; Lim, J.-H.; Jung, J.-W.; Kang, B.-C. A major QTL and candidate genes for capsaicinoid biosynthesis in the pericarp of Capsicum chinense revealed using QTL-seq and RNA-seq. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2019, 132(2), 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Guo, N.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xing, H. Combining QTL-seq and linkage mapping to fine map a wild soybean allele characteristic of greater plant height. BMC genomics 2018, 19(1), 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M. K.; Khan, A. W.; Singh, V. K.; Vishwakarma, M. K.; Shasidhar, Y.; Kumar, V.; Garg, V.; Bhat, R. S.; Chitikineni, A.; Janila, P. QTL-seq approach identified genomic regions and diagnostic markers for rust and late leaf spot resistance in groundnut (A rachis hypogaea L.). Plant biotechnology journal 2017, 15(8), 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, J.; Chu, Y.; Chavarro, C.; Botton, S.; Culbreath, A.; Isleib, T. G.; Holbrook, C.; Ozias-Akins, P. Mapping late leaf spot resistance in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) using QTL-seq reveals markers for marker-assisted selection. Frontiers in plant science 2018, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illa-Berenguer, E.; Van Houten, J.; Huang, Z.; van der Knaap, E. Rapid and reliable identification of tomato fruit weight and locule number loci by QTL-seq. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2015, 128(7), 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Liu, C.; Qi, X.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Chen, B.; Tian, X. Mutation of ZmDMP enhances haploid induction in maize. Nature plants 2019, 5(6), 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, A. M.; Oh, C.-S.; Kim, H. T.; Choi, G.; Seo, E.; Yeam, I.; Lee, J. M. QTL-seq analysis for identification of resistance loci to bacterial canker in tomato. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12, 809959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, B.; Bednarek, R.; Wu, S.; Fei, Z.; Ling, K. Resequencing of bottle gourd germplasm and using QTL-Seq to map PRSV-W resistance in bottle gourd (Lagenaria sinceraria) Phytopathology; AMER PHYTOPATHOLOGICAL SOC 3340 PILOT KNOB ROAD: ST PAUL, MN 55121 USA, 2019; pp. pp 156–156. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Huang, Y.; Gu, B. QTL-Seq identifies quantitative trait loci of relative electrical conductivity associated with heat tolerance in bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria). PloS one 2020, 15(11), e0227663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Shi, T.; Wang, F.; Zhou, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, Y. Interval mapping for red/green skin color in Asian pears using a modified QTL-seq method. Horticulture Research 2017, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.; Wei, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.; Yan, Y.; Bao, C. Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling radish root shape using QTL-seq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadambari, G.; Vemireddy, L. R.; Srividhya, A.; Nagireddy, R.; Jena, S. S.; Gandikota, M.; Patil, S.; Veeraghattapu, R.; Deborah, D.; Reddy, G. E. QTL-Seq-based genetic analysis identifies a major genomic region governing dwarfness in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Reports 2018, 37(4), 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Zheng, H.; Bi, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Li, J. Identification of a major QTL and candidate gene analysis of salt tolerance at the bud burst stage in rice (Oryza sativa L.) using QTL-Seq and RNA-Seq. Rice 2020, 13(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubankoh, P.; Wanchana, S.; Saensuk, C.; Ruanjaichon, V.; Cheabu, S.; Vanavichit, A.; Toojinda, T.; Malumpong, C.; Arikit, S. QTL-seq reveals genomic regions associated with spikelet fertility in response to a high temperature in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant cell reports 2020, 39(1), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riangwong, K.; Aesomnuk, W.; Sonsom, Y.; Siangliw, M.; Unartngam, J.; Toojinda, T.; Wanchana, S.; Arikit, S. QTL-seq identifies genomic regions associated with resistance to dirty panicle disease in rice. Agronomy 2023, 13(7), 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songtoasesakul, D.; Aesomnuk, W.; Pannak, S.; Siangliw, J. L.; Siangliw, M.; Toojinda, T.; Wanchana, S.; Arikit, S. QTL-seq identifies Pokkali-derived QTLs and candidate genes for salt tolerance at seedling stage in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agriculture 2023, 13(8), 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannak, S.; Wanchana, S.; Aesomnuk, W.; Pitaloka, M. K.; Jamboonsri, W.; Siangliw, M.; Meyers, B. C.; Toojinda, T.; Arikit, S. Functional Bph14 from Rathu Heenati promotes resistance to BPH at the early seedling stage of rice (Oryza sativa L.) as revealed by QTL-seq. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2023, 136(2), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branham, S. E.; Patrick Wechter, W.; Lambel, S.; Massey, L.; Ma, M.; Fauve, J.; Farnham, M. W.; Levi, A. QTL-seq and marker development for resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum race 1 in cultivated watermelon. Molecular Breeding 2018, 38(11), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Kwon, S.; Park, G.; Kim, H.; Park, Y. Identification of a candidate gene controlling semi-dwarfism in watermelon, Citrullus lanatus, using a combination of genetic linkage mapping and QTL-seq. Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology 2021, 62(3), 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Lin, T.; Klein, J.; Wang, S.; Qi, J.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Weng, Y.; Huang, S. QTL-seq identifies an early flowering QTL located near Flowering Locus T in cucumber. Theoretical and applied genetics 2014, 127(7), 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Li, S.; Deng, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, R. Identification of a major-effect QTL associated with pre-harvest sprouting in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) using the QTL-seq method. BMC genomics 2021, 22(1), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Badri Anarjan, M.; Win, K. T.; Begum, S.; Lee, S. QTL-seq analysis of powdery mildew resistance in a Korean cucumber inbred line. Theoretical and applied genetics 2021, 134(2), 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Upadhyaya, H. D.; Bajaj, D.; Kujur, A.; Badoni, S.; Laxmi; Kumar, V.; Tripathi, S.; Gowda, C. L.; Sharma, S. Deploying QTL-seq for rapid delineation of a potential candidate gene underlying major trait-associated QTL in chickpea. DNA research 2015, 22(3), 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Huai, D.; Kang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liu, K.; Lei, Y.; Liao, B. Detection of a major QTL and development of KASP markers for seed weight by combining QTL-seq, QTL-mapping and RNA-seq in peanut. Theoretical and applied genetics 2022, 135(5), 1779–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Lan, G.; Bai, B.; Yu, P.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, C.; Zhao, X.; Yu, H. Identification of candidate genes associated with peanut pod length by combined analysis of QTL-seq and RNA-seq. Genomics 2024, 116(3), 110835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Song, S.; Zhou, R.; Li, D.; Gao, Y.; Cui, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, J.; Zhang, X. QTL-seq and transcriptome analysis disclose major QTL and candidate genes controlling leaf size in Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 580846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikam, V.; Molenaar, W.; Melchinger, A. E.; Boddupalli, P. M. Doubled haploid technology for line development in maize: technical advances and prospects. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2019, 132(12), 3227–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, E., Jr. A line of maize with high haploid frequency. The American Naturalist 1959, 93(873), 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotarenco, V.; Dicu, G.; State, D.; Fuia, S. New inducers of maternal haploids in maize. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Prigge, V.; Xu, X.; Li, L.; Babu, R.; Chen, S.; Atlin, G. N.; Melchinger, A. E. New insights into the genetics of in vivo induction of maternal haploids, the backbone of doubled haploid technology in maize. Genetics 2012, 190(2), 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Jin, W.; Melchinger, A. E.; Chen, S. Gametophytic and zygotic selection leads to segregation distortion through in vivo induction of a maternal haploid in maize. Journal of Experimental Botany 2013, 64(4), 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yue, Y.; Zhao, H.; Fei, X.; E, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, S.; Lai, J.; Song, W. Loss-of-function alleles of ZmPLD3 cause haploid induction in maize. Nature plants 2021, 7(12), 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Sun, J.; Li, R.; Yan, S.; Chen, W.; Guo, L.; Qin, G.; Wang, P.; Luo, C.; Huang, W. A reactive oxygen species burst causes haploid induction in maize. Molecular Plant 2022, 15(6), 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, H. U.; Krause, M. D.; Zunjare, R. U.; Almeida, V. C.; Peterlini, E.; Rotarenco, V.; Frei, U. K.; Beavis, W. D.; Lübberstedt, T. Genetic basis of maize maternal haploid induction beyond MATRILINEAL and ZmDMP. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1218042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gent, J. I.; Dawe, R. K. Haploid induction by a maize cenh3 null mutant. Science Advances 2021, 7(4), eabe2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammona, K.; Dermail, A.; Suriharn, K.; Lübberstedt, T.; Wanchana, S.; Thunnom, B.; Poncheewin, W.; Toojinda, T.; Ruanjaichon, V.; Arikit, S. Accelerating haploid induction rate and haploid validation through marker-assisted selection for qhir1 and qhir8 in maize. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1337463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, Y.; Young, L.; Yaegashi, H.; Natsume, S.; Shea, D. J.; Takagi, H.; Booker, H.; Innan, H.; Terauchi, R.; Abe, A. High-performance pipeline for MutMap and QTL-seq. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, Y.; Suetsugu, N.; Kong, S.-G.; Wada, M. Two interacting coiled-coil proteins, WEB1 and PMI2, maintain the chloroplast photorelocation movement velocity in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107(45), 19591–19596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Kar, R. K. Chloroplast avoidance movement: a novel paradigm of ROS signalling. Photosynthesis research 2020, 144(1), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger-Liszkay, A. Singlet oxygen production in photosynthesis. Journal of experimental botany 2005, 56(411), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger-Liszkay, A.; Fufezan, C.; Trebst, A. Singlet oxygen production in photosystem II and related protection mechanism. Photosynthesis research 2008, 98(1), 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A. V.; Johnson, M. P.; Duffy, C. D. The photoprotective molecular switch in the photosystem II antenna. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2012, 1817(1), 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyer, C. H. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative signaling and the regulation of photosynthesis. Environmental and experimental botany 2018, 154, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuleva, M. A.; Petrova, A. A.; Mamedov, M. D.; Semenov, A. Y.; Ivanov, B. N. O2 reduction by photosystem I involves phylloquinone under steady-state illumination. FEBS letters 2014, 588(23), 4364–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P.; Šnyrychová, I.; Kruk, J.; Strzałka, K.; Nauš, J. Evidence that cytochrome b 559 is involved in superoxide production in photosystem II: effect of synthetic short-chain plastoquinones in a cytochrome b 559 tobacco mutant. Biochemical Journal 2006, 397(2), 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II as a response to light and temperature stress. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Qi, T.; Huang, H.; Xie, D. Regulation of stamen development by coordinated actions of jasmonate, auxin, and gibberellin in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant 2013, 6(4), 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsir, L.; Chung, H. S.; Koo, A. J.; Howe, G. A. Jasmonate signaling: a conserved mechanism of hormone sensing. Current opinion in plant biology 2008, 11(4), 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browse, J. Jasmonate passes muster: a receptor and targets for the defense hormone. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2009, 60(1), 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, S.; Chico, J. M.; Solano, R. The jasmonate pathway: the ligand, the receptor and the core signalling module. Current opinion in plant biology 2009, 12(5), 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Xie, D. Molecular mechanism for jasmonate-induction of anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Journal of experimental botany 2009, 60(13), 3849–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Qi, T.; Huang, H.; Ren, Q.; Wu, D.; Chang, C.; Peng, W.; Liu, Y.; Peng, J.; Xie, D. The jasmonate-ZIM domain proteins interact with the R2R3-MYB transcription factors MYB21 and MYB24 to affect jasmonate-regulated stamen development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2011, 23(3), 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Y.; Seo, J.-S.; Cho, J. H.; Jung, H.; Kim, J.-K.; Lee, J. S.; Rhee, S.; Do Choi, Y. Oryza sativa COI homologues restore jasmonate signal transduction in Arabidopsis coi1-1 mutants. PloS one 2013, 8(1), e52802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConn, M.; Browse, J. The critical requirement for linolenic acid is pollen development, not photosynthesis, in an Arabidopsis mutant. The Plant Cell 1996, 8(3), 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilmiller, A. L.; Koo, A. J.; Howe, G. A. Functional diversification of acyl-coenzyme A oxidases in jasmonic acid biosynthesis and action. Plant Physiology 2007, 143(2), 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldelari, D.; Wang, G.; Farmer, E. E.; Dong, X. Arabidopsis lox3 lox4 double mutants are male sterile and defective in global proliferative arrest. Plant molecular biology 2011, 75(1), 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyprys, P.; Lindemeier, M.; Sprunck, S. Gamete fusion is facilitated by two sperm cell-expressed DUF679 membrane proteins. Nature plants 2019, 5(3), 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Jia, M.; Cao, L.; Yu, J.; Zhao, D. Haploid induction in allotetraploid tobacco using DMPs mutation. Planta 2022, 255(5), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, L. M.; Khaled, A.; Laffaire, J. B.; Chaignon, S.; Gendrot, G.; Laplaige, J.; Bergès, H.; Beydon, G.; Bayle, V.; Barret, P. Loss of pollen-specific phospholipase NOT LIKE DAD triggers gynogenesis in maize. The EMBO journal 2017, 36(6), 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, T.; Starr, D.; Richbourg, L.; Chintamanani, S.; Delzer, B.; Nuccio, M. L.; Green, J.; Chen, Z.; McCuiston, J.; Wang, W. MATRILINEAL, a sperm-specific phospholipase, triggers maize haploid induction. Nature 2017, 542(7639), 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, X.; Meng, D.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, C.; Dong, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, B.; Li, W.; Li, L. A 4-bp insertion at ZmPLA1 encoding a putative phospholipase A generates haploid induction in maize. Molecular plant 2017, 10(3), 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, G.-y.; Li, L.-p.; Wang, P.-t.; Li, X.-y.; Han, Y.-j.; Zhao, X. The action of enhancing weak light capture via phototropic growth and chloroplast movement in plants. Stress Biology 2022, 2(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermail, A.; Lübberstedt, T.; Suwarno, W. B.; Chankaew, S.; Lertrat, K.; Ruanjaichon, V.; Suriharn, K. Combining ability of tropical× temperate maize inducers for haploid induction rate, R1-nj seed set, and agronomic traits. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1154905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, G. A.; Carneiro, M. O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J. From FastQ data to high-confidence variant calls: the genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Current protocols in bioinformatics 2013, 43(1), 11.10. 1–11.10. 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Cleaned reads (million) | Cleaned base (Gb) | % Alignment | Average depth coverage (x) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHI306 | 186.83 | 27.52 | 89.29 | 12.28 |

| K8 | 140.32 | 20.68 | 87.58 | 9.39 |

| Highest HIR bulk | 1521.00 | 229.00 | 99.95 | 107.00 |

| Lowest HIR bulk | 1415.00 | 212.00 | 99.98 | 99.37 |

| Length (bp) | All variants (read depths > 7) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | InDels | ||

| 301,354,135 | 10,615 | 4,200 | |

| 237,068,873 | 11,149 | 4,100 | |

| 232,140,174 | 16,807 | 6,170 | |

| 241,473,504 | 10,476 | 3,692 | |

| 217,872,852 | 6,239 | 2,722 | |

| 169,174,353 | 9,796 | 3,510 | |

| 176,764,762 | 5,623 | 1,663 | |

| 175,793,759 | 8,146 | 3,273 | |

| 156,750,706 | 7,519 | 2,632 | |

| 150,189,435 | 4,256 | 1,633 | |

| 2,058,582,553 | 90,626 | 33,595 | |

| QTL | Chr. | QTL-region | Mb | Confidence interval (99%) | Δ(SNP index) | No. of SNP/InDel | R2>0.3 | No. of genes | Candidate genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qHI2 | 2 | 170263374 - 210388889 | 40.12 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 1,777 | 69 | 28 | GRMZM2G140156_RID-transcription factor 2, GRMZM2G359746_WEB1 gene_WEAK CHLOROPLAST MOVEMENT UNDER BLUE LIGHT 1 |

| qHI3 | 3 | 213006045 - 223082649 | 10.08 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 1,254 | 35 | 15 | GRMZM2G440943_Helicase/SANT-associated DNA binding protein, AC198725.4_FG009_WRKY DNA-binding protein 28 |

| qHI6 | 6 | 130180223 - 145992397 | 15.81 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 473 | 2 | - | - |

| qHI8 | 8 | 120056063 - 159995947 | 38.94 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 1,720 | 41 | 15 | GRMZM2G091276_JAR1a_Jasmonate-resistant 1, GRMZM2G134738_Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5b-3 mitochondrial (ZmCOX5b-3) |

| SNP position (V.2) | Chromosome | R2 | P-value | N | Gene | Variation | Mutation | Exon | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 186384027 | 2 | 0.58 | 1.04E-09 | 42 | GRMZM2G359746 | T/C | missense | 2 | R->Q |

| 186384242 | 2 | 0.28 | 1.31E-04 | 42 | GRMZM2G359746 | T/G | missense | 2 | Q->H |

| 186384636 | 2 | 0.43 | 5.14E-07 | 43 | GRMZM2G359746 | T/G | missense | 2 | D->A |

| 217212966 | 3 | 0.34 | 1.37E-05 | 43 | AC198725.4 | T/G | missense | 3 | D->P |

| 217212967 | 3 | 0.34 | 1.37E-05 | 43 | AC198725.4 | C/G | missense | 3 | D->P |

| 217214782 | 3 | 0.27 | 1.31E-04 | 44 | AC198725.4 | T/G | missense | 1 | T->P |

| 144700162 | 8 | 0.27 | 1.57E-04 | 43 | GRMZM2G091276 | C/T | missense | 5 | G->E |

| 144700252 | 8 | 0.31 | 6.44E-05 | 41 | GRMZM2G091276 | C/T | missense | 5 | G->D |

| 144700393 | 8 | 0.5 | 2.98E-08 | 44 | GRMZM2G091276 | C/T | missense | 5 | R->H |

| 144700487 | 8 | 0.72 | 3.47E-13 | 41 | GRMZM2G091276 | G/C | missense | 5 | G->R |

| Marker | Range of HIR | Average | SNP | n | R2 | P-value | PVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEB1_2_186384027 | 1.39-23.01 | 11.96 | T/T | 309 | 0.08 | 4.39E-07 | 8 |

| 0-19.3 | 10.36 | T/C | |||||

| 0.95-16.42 | 8.19 | C/C | |||||

| JAR1a_8_ 144700487 | 4.6-22.32 | 11.67 | G/G | 331 | 0.03 | 1.82E-03 | 3 |

| 0-23.36 | 10.02 | G/C | |||||

| 0.95-20.65 | 9.02 | C/C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).