1. Introduction

According to the prevailing somatic mutation theory, a cancer develops in a step-wise manner through the successive accumulation of mutations in a single cell, whose descendants are selected for the progressive traits of malignancy: uncontrolled cell proliferation, clonal expansion, invasion of adjacent tissues, and eventual spread to distant organs (metastasis). This model, which mechanistically links cancer pathogenesis to oncogenic mutations via linear molecular pathways, has recently been questioned [

1,

2]. Although it is generally suggested that just a few (four or five) mutations drive tumorigenesis, there is an enormous diversity of genetic alterations in cancers to the point where almost every gene has been linked to cancer [

3,

4]. Also, it is not usually clear which of these mutations are the main cancer drivers, since similar cancers in different individuals display only modest overlap in their gene mutations, and they may not even share any mutation in the same gene [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Moreover, it is always possible to point to the specific malignant trait that an individual cancer gene induces. Although it was anticipated that a common set of driver mutations would be identified for each cancer type, this did not turn out to be the case [

10]. Even more telling is the association of well-known cancer genes with common benign conditions, such as nevi, seborrheic keratosis and rheumatoid arthritis [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Along the same lines, somatic

FGFR3 mutations are drivers of some malignancies, such as bladder cancer and multiple myeloma; yet, curiously, germline inheritance of

FGFR3 alterations causes dwarfism syndromes, but does not increase cancer risk in affected individuals [

15,

16,

17]. A further unexpected finding is that somatic mutations are prevalent in healthy tissues of ageing persons, who do not have a diagnosis of cancer [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

These observations call into question the precise role of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in cancers, benign diseases, and, for that matter, normal ageing. Although mutations of these genes are involved in tumorigenesis, their role appears to depend on additional events or existing cellular conditions [

2]. This article proposes that cells in multicellular organisms are organized by an elaborate, dynamic genome-wide regulatory network (GRN), in which non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) play an indispensable role, and whose disruption causes the cell to transform into a neoplastic phenotype.

2. Non-Coding RNAs Across the Domains of Life

A significant discovery over the past few decades is that ncRNAs, which were initially thought to be by-products of RNA processing or represent transcriptional noise, are, in fact, crucial for vital cellular processes [

27]. They are ubiquitous in all three domains of life: domain Bacteria (kingdom: Eubacteria), domain Archaea (kingdom: Archaebacteria), and domain Eukarya (kingdoms: Protista, Fungi, Plantae and Animalia). Across all of these, they regulate gene expression as well as buffer or enforce gene activities.

In bacteria, ncRNAs, called small RNA regulators (sRNA), are typically 50 to 400 nucleotides (nt) in length. Individual sRNAs affect the expression of a single or multiple genes that encode metabolic proteins, transcription factors or virulence factors, establishing a hierarchical order of regulation in various metabolic and physiological processes [

28]. This occurs by different mechanisms, such as altering RNA conformation, base pairing with other RNAs, or binding to proteins and DNA [

29]. In general, sRNAs fall into two classes:

cis-encoded antisense sRNA, which overlaps a segment on the opposite strand of a gene and shares an extended region of complementarity with its target messenger RNA (mRNA); and

trans-encoded sRNA, which is encoded at a different genomic location from its target mRNA and has less complementarity with it [

30,

31]. Limited complementary allows

trans-encoded sRNAs to base-pair with multiple genes. Their binding at the 5′ end or 3′ end of their target mRNAs modifies their secondary structure, exposing the ribosome binding site (RBS), thus enabling translation. Conversely, the interaction between sRNAs and target mRNAs can inhibit translation; this is brought about by degradation of mRNA by endoribonuclease RNaseE, or through direct binding of sRNA to RBS [

32]. sRNA can also interact with regulatory proteins, leading to conformational adaptation of the protein side-chains and RNA; this permits recognition of different RNA sequences by the same protein. An example of this type of sRNA is Csr/Rsm (carbon storage regulator/regulator of secondary metabolism), which sequesters the global translation repressor protein CsrA/RsmE from the RBS of a subset of mRNAs [

33].

Archaebacteria comprise various species that survive in extreme conditions, such as hot springs and salt lakes, although they are also present in soil, oceans, marshlands and human microbiota [

34,

35]. They contain sRNAs, which enhance their survival in hostile habitats [

36]. Multiple ribosomal RNA (rRNA) copies in mesophilic archaea permit rapid adaptation to changing temperatures, while small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA)-like C/D box types in thermophilic archaea facilitate adjustment to hot environments through RNA stabilization and transfer RNA (tRNA) methylation [

37]. Further, sRNAs in some Archaebacteria, in particular the

Methanosarcina species, appear to facilitate the formation of multicellular complexes during different growth phases and in response to environmental conditions [

38]. In this context, the sRNAs fine-tune gene expression in response to external stress [

39].

In eukaryotes, ncRNAs are widely expressed and are broadly divided into two groups: house-keeping ncRNAs (e.g., rRNA or tRNA), and regulatory ncRNAs. The regulatory ncRNAs are, in turn, subdivided into three types: small ncRNAs (e.g., microRNA or miRNA), which are <200nt in length; long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), which are >200nt; and circular RNAs (circRNAs), which range in size from 100nt to 4000nt [

40,

41,

42]. The regulatory ncRNAs control key biological processes, such as stem cell differentiation and cell fate determination (cell differentiation). They occupy specific subcellular locations where they exert their action. In the nucleus, they coordinate expression of protein-coding genes, whereas in the cytoplasm, they control protein synthesis and can tailor protein function. The ncRNA repertoire shows a significant expansion in eukaryotes, becoming most prominent in the cells of metazoans, which require additional regulators for proper development. Consistent with this notion, miRNA surges coincide with major developmental innovations: from bilaterians to vertebrates to mammals [

43]. In the next section, the evolutionary leap from simple prokaryotes to complex eukaryotes is described.

3. From Prokaryotes to Eukaryotes: The Hidden Layer of Non-Coding RNAs

There is a good correlation between genome size and genetic capability in domain Bacteria and domain Archaea, both of which comprise prokaryotic cells. Their genomes are haploid and consist of closely packed protein-coding genes of varying sizes; for example, from 182 genes in

Carsonella ruddii to 8,602 in

Burkholderia xenovorans [

44,

45]. Prokaryotes contain relatively small amounts of non-coding sequences, about 12%, which encode a small number of regulatory RNAs or function as regulatory elements that control gene expression at the transcriptional and translational levels [

39,

46]. In contrast, the eukaryotic genomes carry a large amount of non-coding sequences, generally ranging from 25% to 50% in simple eukaryotes to >50% in more complex fungi, plants and animals [

47].

The non-coding sequences reside in the intronic and intergenic regions of DNA. Because genes were considered to be synonymous with protein coding, the non-coding sequences were initially dismissed as “junk”. This also reflected the belief that evolutionary progress required innovations in proteins that subserve cell signaling and developmental pathways. The later realization that there is, in fact, no correlation between the perceived complexity of eukaryotic organisms and the number of their protein-coding genes (referred to as the G-value paradox) questioned this assumption [

48]. A further dilemma is that as cells become more complicated, a greater degree of gene regulation is necessary. In prokaryotes, the largely protein-based regulatory apparatus displays a quadratic increase in the number of regulators with genome size [

49,

50]. Such a system cannot be efficiently scaled because its capacity is quickly saturated. It is, therefore, inadequate for multicellular organisms where an enormous amount of information is required for the coordination of developmental pathways. It is now evident that the genomes of complex organisms produce large numbers of ncRNAs, many of which have regulatory functions [

51]. In fact, the majority of the mammalian genome is transcribed in complicated patterns of interlaced and overlapping transcripts; in humans, ncRNAs account for almost 60% of the transcriptome [

52].

The vast hidden layer of ncRNAs in eukaryotes answered the question about where in the genome the information that underpins biological complexity lies. The ncRNA system is aptly equipped to get around the limitations of a protein-based one because of its structural diversity and functional versatility [

2]. That regulatory ncRNAs scale consistently with increasing cellular complexity is evidence that the evolutionary leap from simple prokaryotes to complex eukaryotes is transacted at this level [

43,

53]. This trend continued into the genomes of multicellular organisms, wherein the complicatedness of the ncRNA apparatus runs in parallel with developmental complexity. Consistent with this, the most evolutionarily conserved miRNAs in bilaterian organisms play a role early in embryonic development, while those that evolved later specifically in mammals function at later stages of embryonic development [

54]. Further, species-specific miRNAs are generally active in differentiated cell types rather that during embryonic development. This supports the notion that certain ncRNAs in more complex metazoans coordinate pivotal cell activities, such as developmental timing and cell identity.

The multilayered interactions and crosstalk among the ncRNAs as well as their association with various molecular regulators, such as chromatin remodeling factors, transcription factors and nuclear trafficking modulators, create a network for relaying information and provide the groundwork for the GRN [

55,

56]. Some of the principles that govern the behavior of regulatory networks are examined in the next section.

4. The Cell from a Systems Biology Perspective

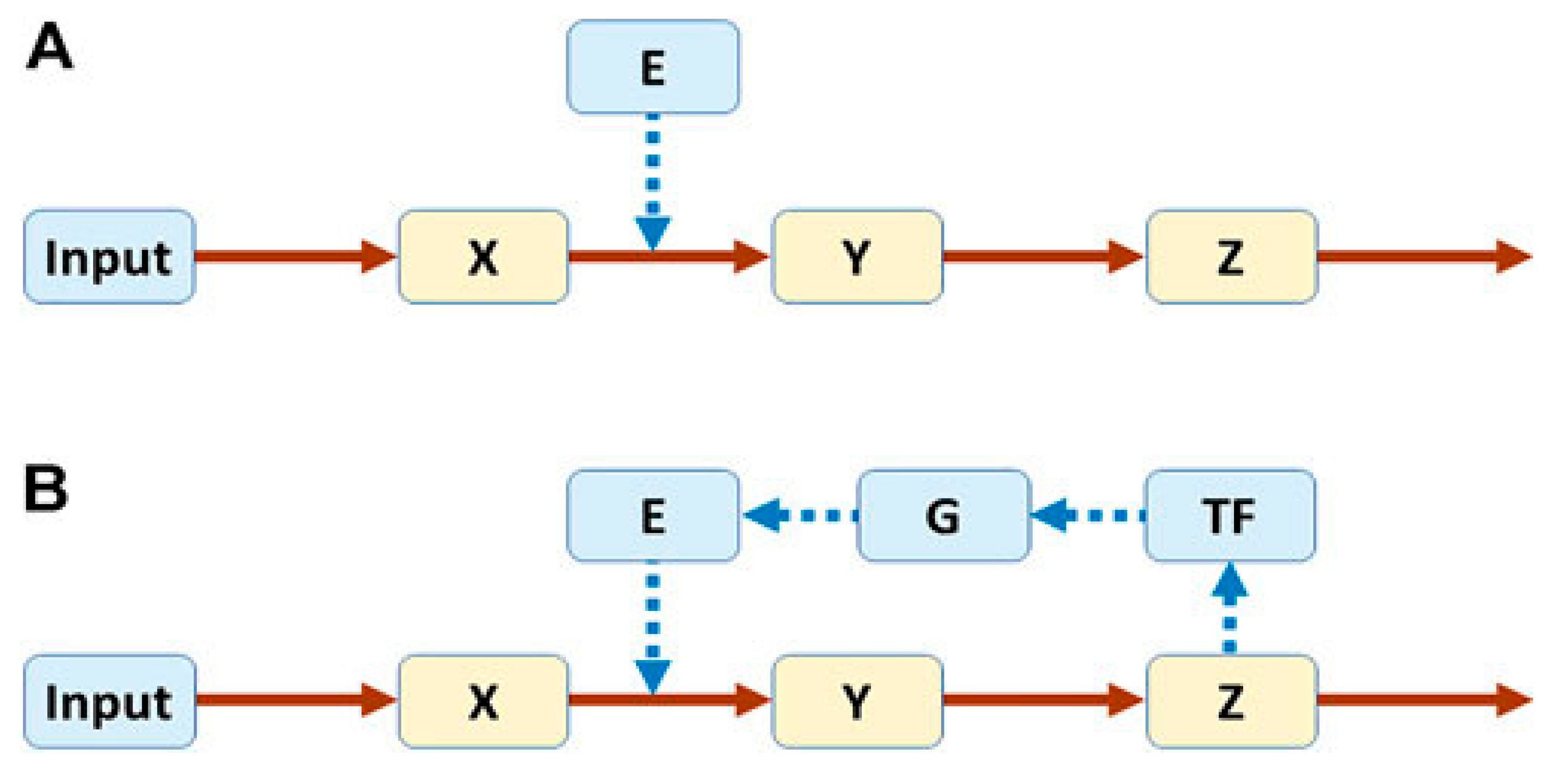

Biological systems are complex because they are made up of many components that are interactive, adaptable and dynamic. An understanding of how they function can be gleaned by dissecting specific pathways and reconstructing the whole from their individual parts. Voit described the behavior of a pathway without and with feedback loops, which are central to its regulation [

57]. In

Figure 1,

X,

Y and

Z represent metabolites, and

E an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of

X to

Y. Pathway A is not regulated, but in Pathway B, regulation is introduced with

Z turning on production of a transcription factor (

TF) that, in turn, causes gene

G to produce

E.

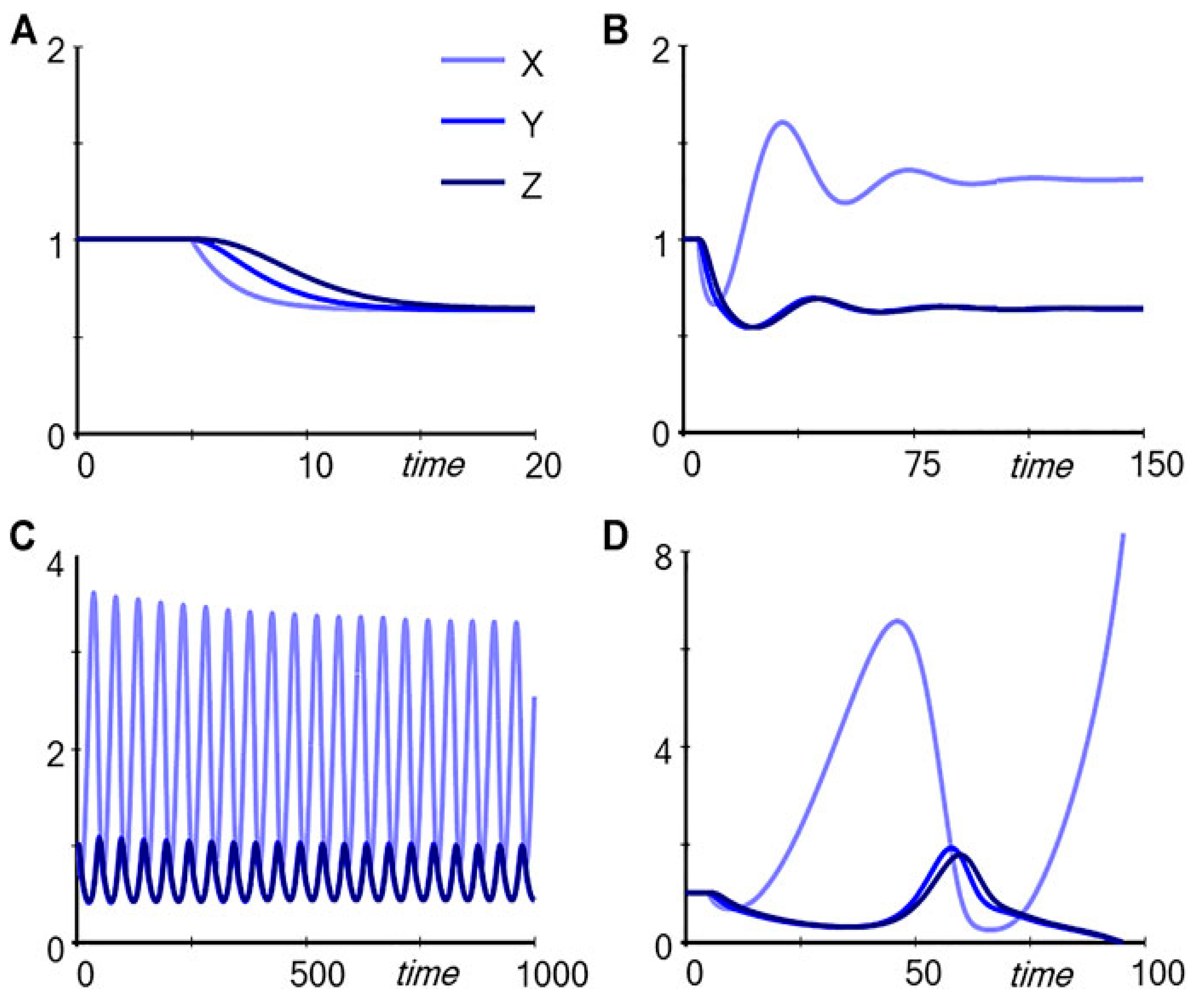

If

Input is decreased, the two pathways respond differently, as depicted in

Figure 2. For the unregulated pathway (Pathway A in

Figure 1), reducing

Input from 1.0 to 0.8, for example, causes a successive decrease in the metabolites (

X,

Y and

Z) (

Figure 2A). However, for the regulated pathway (Pathway B in

Figure 1), the response follows markedly different patterns, depending on the strength with which

Z drives production of

TF, captured in the parameter

p (

Figure 2 B-D). If

p = 0.4, the response is dampened and the levels of

Y and

Z decrease (

Figure 2B); for

p = 0.56, the system settles into stable limit-cycle oscillations (

Figure 2C); and for

p = 0.6,

Y and

Z disappear (

Figure 2D). It is noteworthy that subtle numerical alterations in the parameter setting can lead to unpredictable qualitative changes in response of the system.

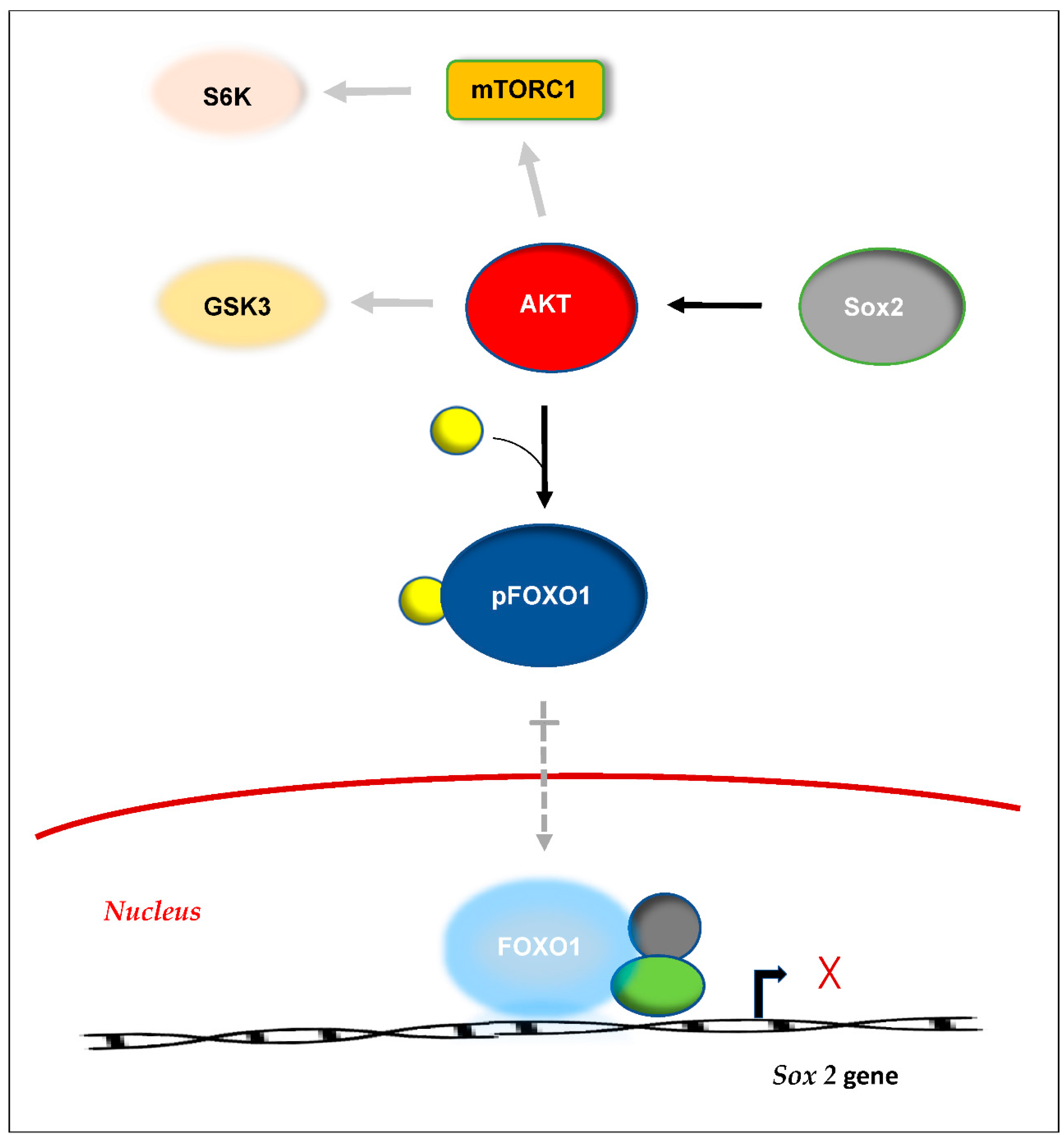

Feedback loops that connect output signals back to their inputs are common regulatory elements in biological signaling systems [

58,

59]. An example is the regulation of Sox2, a transcription factor that is essential for maintaining self-renewal of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells (

Figure 3) [

60].

Sox2 is regulated by a feedback loop, where elevated levels of cytoplasmic Sox2 lead to increased activity of AKT, which is part of the cell’s physiological pathways. Activation of AKT causes phosphorylation of the transcription factor FOXO1 to pFOXO1, which becomes sequestered in the cytoplasm. FOXO1 normally binds to the upstream regulatory region of the Sox2 gene, but its cytoplasmic sequestration makes it unavailable for binding. This results in a decrease in transcription of the Sox2 gene and a subsequent fall in the level of Sox2.

Feedback loops can be positive or negative or a mixture of both (hybrid) [

61]. Positive feedback causes rapid, all-or-nothing transitions, while negative feedback (as in the above example of Sox2 regulation) acts as a restorative force to create a stable limit cycle, usually with faster, smaller-amplitude oscillations. Hybrid feedback promotes a broader range of oscillatory signal outputs, and with non-linear coupling of the two feedback types, novel dynamic states arise. Therefore, feedback loops are critical, allowing diversification of a system state into multiple distinct alternative states [

62,

63].

In classical biology, the metabolic reactions of the cell’s myriad molecules are usually reduced to linear pathways to help decipher their basic operation. Among these in mammalian species are hundreds of cell-specific signaling systems assembled from linear pathways with upstream regulators and downstream targets [

64] They are not free-standing entities, but are linked by signals within and between the different pathways. This establishes a web of connectivity that is essential in mediating important biological functions. One such function is how order is achieved during the development of multicellular organisms where determination of cell identity must be versatile, yet precise and robust to avoid errors [

65]. Recently, the importance of the continuous, dynamic interactions of the cell’s biomolecules as a fundamental organizing process built into all life forms has become evident.

5. How Order Is Achieved: Regulatory Networks and the Origin of Attractor States

A central issue in metazoan development is how different cell types arise from the same genome of its zygote. A cell is shaped by its proteins, which perform a vast array of functions that define its traits. In turn, the collection of all active proteins in a cell is determined by its gene-expression profile at any given time. In humans, this profile encompasses the state of approximately 20,000 genes across the genome: active/inactive [

66]. Since the state of every gene is governed by the GRN, it follows that the GRN oversees a vast number of theoretically possible combinatorial states, which can be conceived as an abstract “state space” [

67,

68]. From any theoretical starting point, the system evolves and eventually settles down into a steady state [

69]. It should be noted that not all gene configurations are necessarily feasible because certain interactions may not be permitted by the regulatory constraints imposed by the GRN [

70]. For instance, genes that mutually repress each other’s expression cannot be fully co-expressed (as illustrated in the example of

Sox2 regulation above). Therefore, as gene expressions change over time, all requisite conditions must be satisfied throughout the network for it to attain a steady state. In this regard, the genome operates as a dynamic system of multiple interacting elements with feedback regulation, from which different self-stabilizing states, referred to as “attractor” states, are generated [

71].

An important feature of an attractor state is that similar but less stable states in its neighborhood or “basin of attraction” tend to move – or are attracted – towards it. A corollary to this is that following a small displacement to another state within its basin, the system will return to its original attractor state. The movement towards established attractor states facilitates the adaptation of select gene expressions towards physiologically stable states, or cell phenotypes, over evolutionary time. Waddington introduced the term “canalization” to capture two essential requirements for development to proceed in an orderly coordinated fashion: first, a buffering potential ensures that organisms develop normally under a range of external conditions; second, the robustness of developmental decisions assures that choices are determined in an all-or-nothing manner rather than drift around [

72]. Notwithstanding, stochastic fluctuations of gene regulators, like transcription factors and epigenetic regulators, or external stimuli, like growth factors, can influence gene expression programs and change the trajectory of cell development [

73,

74]. In effect, the cell is pushed to a position further away, and, if the force is vigorous enough, it can cross over the boundaries of its basin of attraction into the adjacent attractor. This genomic plasticity lays the foundation for differentiation by which a cell transitions from the pluripotent state through multiple progenitor states to the differentiated state. At the same time, the intrinsic robustness of the GRN provides a counterbalance that enables a cell to resist small changes in internal cues or external stimuli [

75]. Under certain conditions, alterations of the gene expression programs are severe enough to be disruptive. The implications of this for cancer development are discussed in the next section.

6. From Normalcy to Malignancy: Role of Non-Coding RNAs

Metazoan development starts with the reprogramming of the zygotic genome into a transient totipotent state, which, in bilaterians, creates three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) that give rise to all cells in the organism. In humans, this comprises about 250 different cell types, totaling an estimated 4x10

13 in the adult. A crucial property of epithelial and mesenchymal cells during embryogenesis is their ability to migrate to distant sites or form complex organs during morphogenesis [

76]. This is directed by the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) program, a cellular process that transiently converts epithelial into mesenchymal characteristics.

The events that unfold during transcription are crucial to developmental programs because they dictate the spatiotemporal expression of genes, which ultimately determines the cell type-specific proteome. While genes hold the blueprint for development and proteins are responsible for structure, ncRNAs provide an indispensable interface between the two to guide proper regulation of gene expression and cellular identity. Cell development begins at the level of the chromatin where epigenetic processes, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, control gene activation or repression [

77,

78]. Recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) initiates transcription, which occurs bidirectionally with sense mRNA and antisense lncRNA. Their expression from their own genes allows lncRNAs to regulate themselves [

79]. More recent evidence suggests that transcription of lncRNA may be initiated by unidentified initiation factors and is

trans-regulated by lncRNAs from other chromosomes [

80].

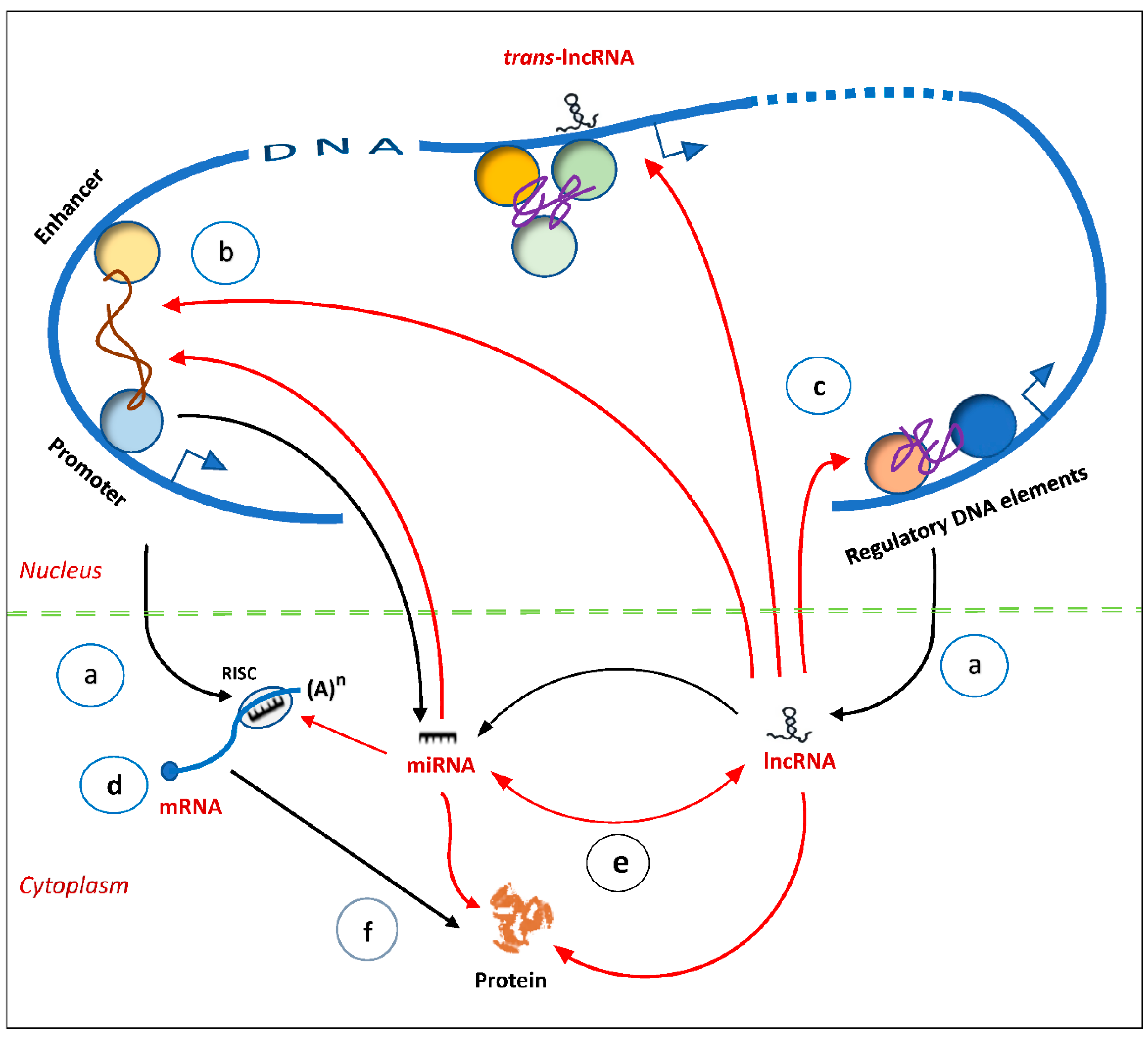

In the nucleus, lncRNAs contribute to gene expression in different ways. They modulate chromatin function and regulate the assembly and function of membrane-less nuclear bodies; they establish active and repressive domains through transcription repressor complexes; and they serve as scaffolds to tether enzyme complexes to gene promoters, which is followed by recruitment of transcription factors and transcription factor-DNA binding motif sequences within enhancers and promoters [

81]. In addition to lncRNAs, various nuclear miRNAs participate in the regulation of gene transcription [

82]. In the cytoplasm, miRNAs fine-tune protein synthesis through interactions with mRNAs [

40].

The capacity of ncRNAs to act locally as well as affect genomic segments separated by long linear distances on the same chromosomes or even on different chromosomes extends their regulatory reach across the genome [

83,

84]. Another important feature is the interplay among miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs, which affects their function. For example, lncRNAs act as decoys by capturing miRNAs, thus preventing them from binding to their respective mRNAs. [

42,

56]. In addition, ncRNAs interact with DNA and proteins to modulate epigenetic components, mediate intra-chromosomal interactions, and control gene transcription [

85]. The result is an elaborate regulatory network established through ncRNA-ncRNA, ncRNA-DNA and ncRNA–protein connectivity (

Figure 4). They form a parallel-processing system, whose signals are processed in many different pathways simultaneously, and they are non-linear and modifiable [

86].

6.1. Consequences of Disruption of Non-Coding RNAs

Mutations of ncRNAs can lead to changes in gene-expression patterns and alterations of regulatory protein activities. Because the GRN is robust, minor degrees of rewiring of its components are tolerated, but the accumulation of a large set of genomic changes warps the state space and reshapes its contour. The corridor of accessible attractors is expanded as new developmental pathways are carved out. The outcome is that the susceptible cell can veer into other attractor states, among which might be previously unoccupied “cancer” attractors. This becomes an incipient cancer cell.

ncRNA functions can be disrupted in several ways. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in lncRNA alter its secondary configuration and interfere with lncRNA-miRNA interactions [

87]. Also, SNVs in the 5’ UTR of

cis-regulatory sequences affect translation, while those in the 3’ UTR disrupt RNA-RNA or RNA-protein interactions and, thus, interfere with post-transcriptional gene expression [

88,

89]. Further, in most cancers, ncRNAs directly or indirectly interact with oncogenic proteins, enforcing or dampening their action [

90,

91]. Chromosomal translocation, a frequent occurrence in cancer, can lead to aberrant fusion circRNA, by the back-splicing of complimentary repetitive intronic elements (Alu elements). Unlike normal circRNAs, which act as sponges, fusion circRNAs can abnormally stimulate cell proliferation [

92]. In some cancers, adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing in 3’ UTRs result in deletion of regulatory elements, like miRNAs, that they may contain; this loss can cause inappropriate oncogene activation [

93]. Finally, chromosomal loss and duplication can alter the number of copies of ncRNAs.

6.2. Clinicopathological Considerations of the Cancer Attractor State

It is instructive to inquire how the concept of the cancer attractor reconciles clinical observations that are not fully explained. First, almost all cancers harbor a wide diversity of mutations despite having similar histological characteristics. For example, in small-cell lung cancer, which makes up about 15% of all lung cancers, several different oncogenic pathways are activated or silenced [

94]. These include overexpression of the

MYC family of oncogenes, dual inactivation of the tumor suppressor genes

TP53 and

RB1, activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and upregulation of the Notch pathway. Nonetheless, their histological appearance is similar. These observations can be explained by the convergence of different pathways toward a common cancer phenotype. Stated another way, the GRN steers the cell along trajectories within its state space into the basin of attraction of a particular attractor state.

Second, metastasis, a common occurrence in cancer patients, is an incompletely understood process [

95]. To progress through the metastatic cascade, a cancer cell goes through a series of steps: local invasion and intravasation into the blood circulation, survival in the blood stream, and extravasation and growth in new organs [

96]. Metastasis is ascribed to the known cancer genes and their associated signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation [

97]. In addition to the proclivity for metastasis, a related issue is its timing. Although metastasis is generally believed to be a “late” event, early metastasis is frequent in the course of many cancers. In small-cell lung cancer, for example, about 70% of patients have overt metastatic disease at diagnosis, commonly in the lymph nodes, brain, liver and bones [

94]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer, dissemination of cancer cells occurs early, even before the cancer is clinically detectable (<10 mm

3) [

98].

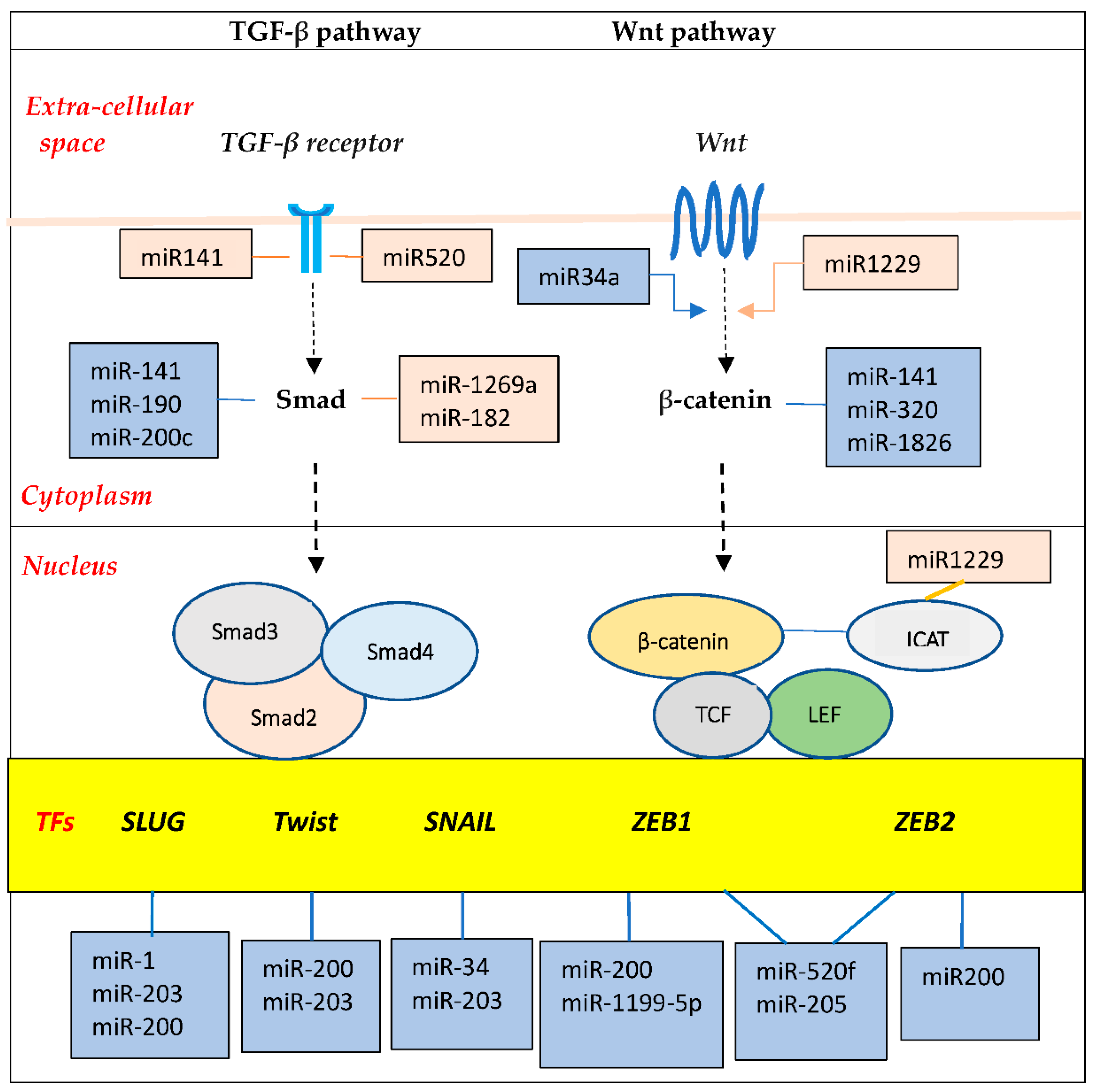

It appears that at the core of the metastatic process is the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) program [

99,

100]. This developmental program is essential for embryogenesis and tissue regeneration (e.g., wound healing), but its aberrant reactivation in cancer results in cells that are more mobile and invasive, and capable of overcoming the metastatic hurdles [

101]. Several different signaling pathways, including TGFβ/Smad, WNT/β-catenin, Notch and tyrosine signaling pathways, can be activated in EMT programs [

102,

103,

104]. These promote expression of EMT transcription factors, such as the zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factors ZEB1 and ZEB2, the zinc-finger factors SNAI1 (SNAIL) and SNAI2 (SLUG), and the basic helix–loop–helix factors TWIST1 and TWIST2 (

Figure 5).

Importantly, various miRNAs interact in complex ways with these transcription factors to drive or buffer EMT signal pathways. For example, miR-200 and miR-205 cooperate to suppress ZEB1/2 expression; on the other hand, ZEB1/2 directly suppress the transcription of the miR-200 [

105]. Similarly, a mutually inhibitory loop is present between Zeb1 and miR-1199-5p. These double-negative feedback loops serve as epithelial/mesenchymal switches to enhance the versality required by cells for EMT. Additionally, a number of lncRNAs regulate EMT through various mechanisms, such as functioning as competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) to sequester miRNA, or sponging of miRNAs. Further, lncRNAs interact with transcription factors to direct the polycomb-repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to various epithelial gene targets [

91,

106,

107,

108].

The epithelial and mesenchymal cells correspond to distinct attractor states under the tight control of ncRNAs [

109,

110,

111]. However, instead of transitioning between the epithelial and mesenchymal states, cancer cells undergo a partial or transient EMT, displaying a phenotype with a mixture of epithelial and mesenchymal traits [

112]. The hybrid E/M cells have a higher potential for metastasis compared with cells at either end of the EMT spectrum. Additionally, they display increased cancer stem cell activity or pluripotency [

100]. In summary, the hijacking of the EMT program by the cancer cell generates a hybrid E/M attractor state, which endows the cell with highly malignant traits, including a mechanism for metastasis at early stages.

7. Discussion

The most conspicuous anomaly in cancer cells is multiple mutations of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, which often result in constitutive activation of signaling protein cascades that promote cell proliferation. Although not all mutations are necessarily compatible with cell survival, those that are tolerated could confer a selective growth advantage over its normal counterpart [

113]. As posited by the somatic mutation theory, this yields an expanding clone of cells that acquire progressive malignant traits. But the observed gene mutations are inconsistent among cancers. Beyond cancer, many of these mutations are also associated with benign conditions and are prevalent in healthy tissues. The discrepancy among the putative cancer genes and their functional diverseness suggest that other mechanisms are at play during the development of a cancer [

1,

2,

114].

Alongside the overt chromosomal abnormalities observed in cancer cells, there is a large, hidden layer of ncRNAs. They operate at several different cellular levels, from transcriptional control of gene expression through post-transcriptional modulation of mRNA stability to post-translational functioning of proteins. Through their crosstalk with other RNAs as well as their interplay with DNA and proteins, they are integral components of regulatory mechanisms that have previously been attributed to proteins. This discovery has led to a new way of thinking about how the genome is organized, and represents a conceptual shift about how cancer develops [

115,

116].

An appreciation of the central role of the genome regulatory system in tumorigenesis starts with the recognition that cells are defined by their gene-expression patterns as part of a dynamic network of interacting elements. The metazoan genome contains a huge number of possible gene configurations, which are either persistent and stable, or evanescent and unstable. From any starting point, the system spontaneously evolves and eventually settles down into stable attractor states, corresponding to distinct cell types [

66,

71,

117]. Over time, cell development has become canalized in such a way that cells are guided by evolutionary maps down narrow valleys in the epigenetic landscape to those attractor states that serve useful physiological functions [

72]. Nonetheless, within the GRN state space, other potential attractor states exist, but are not normally occupied, since the less functional attractors are bypassed.

An important property of the attractor state is its robustness to tolerate minor changes. However, a collection of multiple disruptions of ncRNAs can effectively rewire the GRN and push the cell towards a different attractor state or cell phenotype. In consonance with the notion of the cell as an attractor state, the cancer cell, whose behaviors are conditioned by the particular pattern of the connections and interactions within its regulatory network, also represents an attractor state [

70]. The path towards a cancer attractor is forged by a warping of the topography of the epigenetic landscape through alterations in the ncRNA network connectivity [

86].

This view offers a different perspective of the role of somatic mutations of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in cancer pathogenesis. Alterations of these genes contribute to the proliferation of cancer cells through their action on the cell cycle apparatus and their links to associated signal transduction pathways. Moreover, different ncRNA circuitries intersect with oncogenic pathways, which can be indirectly activated or repressed. However, the crucial consideration is that the presence of mutated oncogenic driver genes appears insufficient to cause cancer. Rather, this transition is transacted at the level of the incipient cancer cell with its immanent neoplastic program scripted by regulatory ncRNAs.

Implications for Systemic Cancer Therapy

The centrality of the ncRNA network in tumorigenesis has important implications regarding our approach to systemic cancer therapy. Cytotoxic chemotherapy was introduced in the 1940s on the assumption that the mitotic cycle is perturbed in cancer cells, and, later, discovery of disrupted oncogenic signaling pathways guided the design of molecularly targeted therapy in the late 1990s [

118,

119]. Both of these therapies have modestly improved the cure rates of several types of cancer when given in the post-operative adjuvant setting after resection of all macroscopic cancer, and extended overall survival times of patients with metastatic disease. Nonetheless, the situation for patients with advanced or metastatic cancers, especially those originating in epithelial tissues, like breast, lung, prostate or colorectum, remains particularly dire [

120]. While development of these therapies began with reasonable starting points, a deeper understanding of the cause of cancer was not at hand. But the emerging information about the role of cell’s genomic regulatory system in tumorigenesis is already influencing the next generation of cancer therapy [

121]. The targeting of ncRNAs by nucleic acid-based therapy could herald a different approach to the design of novel anti-cancer strategies [

122]. Nonetheless, new opportunities bring new challenges. If multiple alterations of the ncRNA regulatory network drive the cancer process, we can assume that restoring order would require several points of intervention. This calls for an in-depth knowledge of network dynamics and how specific components impact its overall functioning [

123,

124].

In conclusion, the evolutionary progress from simple prokaryotes to the complex eukaryotes is orchestrated by an elaborate system of regulatory ncRNAs, which are conserved and distributed across all three domains of life. They are the architects of cellular complexity in multicellular organisms, but when they misfire, they become the agents of malignancy. The new understanding of the organization and regulation of the genome affords us an opportunity to update our views about the early stages of cancer development to better align with the reality of clinical observations.

Funding

No external funding received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3’ UTR |

3’ untranslated region |

| 5’ UTR |

5’ untranslated region |

| ceRNA |

competitive endogenous RNA |

| circRNA |

circular RNA |

| EMT |

Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition |

| GRN |

genome-wide regulatory network |

| lncRNA |

long non-coding RNA |

| miR |

mature form of microRNA |

| miRNA |

microRNA |

| mRNA |

messenger RNA |

| ncRNA |

non-coding RNA |

| nt |

nucleotide |

| PRC2 |

polycomb-repressive complex 2 |

| RBS |

ribosomal binding site |

| RISC |

RNA-induced silencing complex

|

| rRNA |

ribosomal RNA |

| snoRNA |

small nucleolar RNA |

| SNV |

single nucleotide variants |

| sRNA |

small RNA |

| tRNA |

transfer RNA |

References

- Huang, S.; Soto, A.M.; Sonnenschein, C. The end of the genetic paradigm of cancer. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23(3), e3003052. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. The Primary Role of Non-coding RNA in the Pathogenesis of Cancer. Genes 2025, 16, 771. [CrossRef]

- The ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 2020, 578, 82–93. [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, J.P. Every gene can (and possibly will) be associated with cancer. Trends Genet. 2022, 38(3), 216-217. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Roberts, N.D.; Wala, J.A.; Shapira, O.; Schumacher, S.E.; Kumar, K.; Khurana, E.; Waszak, S.; Korbel, J.O.; Haber, J.E.; et al. PCAWG Consortium. Patterns of somatic structural variation in human cancer genomes. Nature 2020, 578, 112–121. [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, G.; Miller, M.L.; Aksoy, B.A.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; Schultz, N.; Sander, C. Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013, 45(10), 1127-1133. [CrossRef]

- Tamborero, D.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Perez-Llamas, C.; Deu-Pons, J.; Kandoth, C.; Reimand, J.; Lawrence, M.S.; Getz, G.; Bader, G.D.; Ding, L.; et al. Comprehensive identification of mutational cancer driver genes across 12 tumor types. Sci Rep. 2013, 3, 2650. [CrossRef]

- Kandoth, C.; McLellan, M.D.; Vandin, F.; Ye, K.; Niu, B.; Lu, C.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Q.; McMichael, J.F.; Wyczalkowski, M.A.; et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 2013, 502(7471), 333-339. [CrossRef]

- Porta-Pardo, E.; Garcia-Alonso, L.; Hrabe, T.; Dopazo, J.; Godzik, A. A Pan-cancer catalogue of cancer driver protein interaction interfaces. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015, 11(10), e1004518. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jiménez, F.; Muiños, F.; Sentís, I.; Deu-Pons, J.; Reyes-Salazar, I.; Arnedo-Pac, C.; Mularoni, L.; Pich, O.; Bonet, J.; Kranas, H.; et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 555–572. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Lippman, S.M.; Flaherty, K.T.; Kurzrock, R. The Conundrum of Genetic "Drivers" in Benign Conditions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016, 108(8), djw036. [CrossRef]

- Adashek, J.J.; Kato, S.; Lippman, S.M.; Kurzrock, R. The paradox of cancer genes in non-malignant conditions: implications for precision medicine. Genome Med. 2020, 12(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Shain, A.H.; Yeh, I.; Kovalyshyn, I.; Sriharan, A.; Talevich, E.; Gagnon, A.; et al. The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373(20), 1926-1936. [CrossRef]

- Torreggiani, S.; Castellan, F.S., Aksentijevich, I.; Beck, D.B. Somatic mutations in autoinflammatory and autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024, 20, 683–698. [CrossRef]

- Hafner, C.; van Oers, J.M.; Hartmann, A.; Landthaler, M.; Stoehr, R.; Blaszyk, H.; et al. High frequency of FGFR3 mutations in adenoid seborrheic keratoses. J Invest Dermatol. 2006, 126(11), 2404-2407. [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 2014, 507, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- L'Hôte C.G.; Knowles, M.A. Cell responses to FGFR3 signalling: growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2005, 304(2), 417-431. [CrossRef]

- Coorens, T.H.H.; Collord, G.; Jung, H.; Wang, Y.; Moore, L.; Hooks, Y.; Mahbubani, K.; Law, S.Y.K.; Yan, H.H.N.; Yuen, S.T. et al. The somatic mutation landscape of normal gastric epithelium. Nature 2025, 640, 418–426. [CrossRef]

- Machado, H.E.; Mitchell, E.; Øbro, N.F.; Kübler, K.; Davies, M.; Leongamornlert, D.; Cull, A.; Maura, F.; Sanders, M.A.; Cagan, A.T.J.; et al. Diverse mutational landscapes in human lymphocytes. Nature 2022, 608, 724–732. [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Leongamornlert, D.; Coorens, T.H.H.; Sanders, M.A.; Ellis, P.; Dentro, S.C.; Dawson, K.J.; Butler, T.; Rahbari, R.; Mitchell, T.J.; et al. The mutational landscape of normal human endometrial epithelium. Nature 2020, 580(7805), 640-646. [CrossRef]

- Lee-Six, H.; Olafsson, S.; Ellis, P.; Osborne, R.J.; Sanders, M.A.; Moore, L.; Georgakopoulos, N.; Torrente, F.; Noorani, A.; Goddard, M.; et al. The landscape of somatic mutation in normal colorectal epithelial cells. Nature 2019, 574(7779), 532-537. [CrossRef]

- Martincorena, I.; Fowler, J.C.; Wabik, A.; Lawson, A.R.J.; Abascal, F.; Hall, M.W.J.; Cagan, A.; Murai, K.; Mahbubani, K.; Stratton, M.R.; et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science 2018, 362(6417), 911-917. [CrossRef]

- Martincorena, I.; Roshan, A.; Gerstung, M.; Ellis, P.; Van Loo, P.; McLaren, S.; Wedge, D.C.; Fullam, A.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Tubio, J.M.; et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 2015, 348(6237), 880-886. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.; Kakiuchi, N.; Yoshizato, T.; Nannya, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Shiozawa, Y.; Sato, Y.; Aoki, K.; Kim, S.K.; et al. Age-related remodelling of oesophageal epithelia by mutated cancer drivers. Nature 2019, 565(7739), 312-317. [CrossRef]

- Shlush, L.I. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis. Blood 2018, 131(5), 496-504. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.R.J.; Abascal, F.; Nicola, P.A.; Lensing S.V.; Roberts A.L.; Kalantzis G.; et al. Somatic mutation and selection at population scale. Nature 2025, 647, 411–420. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Barbosa, C.; Calhoun, S.H.; Wieden, H.J. Non-coding RNAs: what are we missing? Biochem Cell Biol. 2020, 98(1), 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Beisel, C.L.; Storz, G. The Base-Pairing RNA Spot 42 Participates in a Multioutput Feedforward Loop to Help Enact Catabolite Repression in Escherichia coli. Molecular Cell 2010, 41(3), 286-297. [CrossRef]

- Majumder, R.; Ghosh, S.; Das, A.; Singh, M.K.; Samanta, S.; Saha, A.; Saha, R.P. Prokaryotic ncRNAs: Master regulators of gene expression. Current Research in Pharmacology and Drug Discovery 2022, 3, 100136. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Srivastava, S. Small RNA-mediated regulation in bacteria: A growing palette of diverse mechanisms. Gene 2018, 656, 60-72. [CrossRef]

- Thomason, M.K.; Storz, G. Bacterial antisense RNAs: how many are there, and what are they doing? Annu Rev Genet. 2010, 44, 167-188. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, S.; Storz, G. Bacterial small RNA regulators: versatile roles and rapidly evolving variations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011, 3(12), a003798. [CrossRef]

- Duss, O.; Michel, E.; Dit Konté, N. D.; Schubert, M.; Allain, F. H. T. Molecular basis for the wide range of affinity found in Csr/Rsm protein-RNA recognition. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42(8), 5332–5346. [CrossRef]

- Auguet J-C.; Barberan, A.; Casamayor, E.O. Global ecological patterns in uncultured Archaea. The ISME Journal 2010, 4(2), 182–190. [CrossRef]

- Bang, C.; Schmitz, R.A. Archaea associated with human surfaces: not to be underestimated. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2015, 39(5), 631–648. [CrossRef]

- Gelsinger, D.R.; DiRuggiero, J. The Non-Coding Regulatory RNA Revolution in Archaea. Genes 2018, 9(3), 141. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrasco, R.; Aliaga-Tobar, V.; Abades, S.; Maracaja-Coutinho, V. The repertoire of candidate archaeal noncoding RNAs and their association with temperature adaptation. BioSystems. 2025, 254, 105519. [CrossRef]

- Galagan, J.E.; Nusbaum, C.; Roy, A.; Endrizzi, M.G.; Macdonald, P.; FitzHugh, W.; et al. The genome of M. acetivorans reveals extensive metabolic and physiological diversity. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 532-542. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Qi, W.; Dong, X.; Li, J. Archaeal RNA processing and regulation: expanding the functional landscape. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2025, 89(4), e00318-24. [CrossRef]

- Chen L.L.; Kim V.N. Small and long non-coding RNAs: Past, present, and future. Cell 2024, 187, 6451–6485. [CrossRef]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.J.; Chen, L.L.; Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021, 22(2), 96-118. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Circular RNAs: Novel Players in Cancer Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(18), 10121. [CrossRef]

- Hertel, J.; Lindemeyer, M.; Missal, K.; Fried, C.; Tanzer, A.; Flamm, C.; Hofacker, I.L.; Stadler, P.F.; et al. The expansion of the metazoan microRNA repertoire. BMC Genomics 2006, 7, 25. [CrossRef]

- Nakabachi, A.; Yamashita, A.; Toh, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Dunbar, H.E.; Moran, N.A.; et al. The 160-kilobase genome of the bacterial endosymbiont Carsonella. Science 2006, 314(5797), 267. [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, T.T.; Motro, Y.; Hallin, P.F.; Lund, O.; Dunn, D.; La, T.; et al. 2006. Ten years of bacterial genome sequencing: comparative-genomics-based discoveries. Funct Integr Genomics 2006, 6(3), 165–185. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, S. Micros for microbes: non-coding regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Trends Genet. 2005, 21, 399–404. [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J. RNA regulation: a new genetics? Nat Rev Genet. 2004, 5, 316–323. [CrossRef]

- Taft, R.J.; Pheasant, M.; Mattick, J.S. The relationship between non-protein-coding DNA and eukaryotic complexity. Bioessays 2007, 29(3), 288-299. [CrossRef]

- Croft, L.J.; Lercher, M.J.; Gagen, M.J.; Mattick, J.S. Is prokaryotic complexity limited by accelerated growth in regulatory overhead? Genome Biol. 2003, 5, 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Gagen, M.J.; Mattick, J.S. Inherent size constraints on prokaryote gene networks due to "accelerating" growth. Theory Biosci. 2005, 123(4), 381-411. PMID: 18202872. [CrossRef]

- Frith, M.C.; Pheasant, M.; Mattick, J.S. The amazing complexity of the human transcriptome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005, 13(8), 894-898. [CrossRef]

- Carninci, P.; Kasukawa, T.; Katayama, S.; Gough, J.; Frith, M.C.; Maeda, N.; et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 2005, 309(5740), 1559-1563. [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S. Challenging the dogma: the hidden layer of non-protein-coding RNAs in complex organisms. Bioessays. 2003, 25, 930–939. [CrossRef]

- DeVeale, B.; Swindlehurst-Chan, J.; Blelloch, R. The roles of microRNAs in mouse development. Nature Reviews. Genetics 2021, 22(5), 307-323. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Luo, G.; Liang, S.; Lü, M. Research progress on the interactions between long non-coding RNAs and microRNAs in human cancer. Oncology letters. 2020, 19(1), 595-605. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Prabhakar, N.; Kumar, L.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Kar, S.; Malik, S.; et al. Crosstalk between long noncoding RNA and microRNA in Cancer. Cell Oncol. 2023, 46, 885–908. [CrossRef]

- Voit, E.O. Perspective: Systems biology beyond biology. Front. Syst. Biol. 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

- Brandman, O.; Meyer, T. Feedback loops shape cellular signals in space and time. Science 2008, 322(5900), 390-395. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, W. Interlinking positive and negative feedback loops creates a tunable motif in gene regulatory networks. Phys. Rev. 2009, E 80, 011926. [CrossRef]

- Ormsbee Golden BD, Wuebben EL, Rizzino A. Sox2 expression is regulated by a negative feedback loop in embryonic stem cells that involves AKT signaling and FoxO1. PLoS One 2013, 8(10), e76345. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Liu, J.; Bao, T.; Huo, H.; Yuan, Y.; Fang, T. Flexible modulation of hybrid feedback loops in competitive biological oscillators. npj Syst Biol Appl. 2025, 11, 122. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. Laws for the dynamics of regulatory networks. Int J Dev Biol. 1998, 42, 479-485. PMID: 9654035.

- Mochizuki A. Controlling complex dynamical systems based on the structure of the networks. Biophys Physicobiol. 2023, 20(2), e200019. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.D.; Landau, E.M.; Iyengar, R. Signaling networks: the origins of cellular multitasking. Cell 2000, 103(2), 193-200. [CrossRef]

- Freeman M. Feedback control of intercellular signalling in development. Nature 2000, 408(6810), 313-319. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. Metabolic stability and epigenesis in randomly constructed genetic nets, J. Theor. Biol. 1969, 22, 437-467. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. Homeostasis and differentiation in random genetic control networks. Nature 1969, 224, 177-178. [CrossRef]

- Fink, T. M. A.; Sheldon, F. Number of Attractors in the Critical Kauffman Model Is Exponential. Physical review letters 2023, 131(26), 267402. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Rozum, J.C.; Quail, M.M.; Qasim, M.N.; Sindi, S.S.; Nobile, C.J.; Albert, R.; Hernday, A.D. Inferring gene regulatory networks using transcriptional profiles as dynamical attractors. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023, 19(8), e1010991. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. On the intrinsic inevitability of cancer: From foetal to fatal attraction. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2011, 21(3), 183-199. [CrossRef]

- Milnor, J.W. On the concept of attractor. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1985, 99, 177-195. [CrossRef]

- Waddington, C.H. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 1942, 150(3811), 563-565. [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; van Oudenaarden, A. Nature, nurture, or chance: stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell 2008,135(2), 216-226. [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Liu, Z. Shaping development by stochasticity and dynamics in gene regulation. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170030. dx. [CrossRef]

- Misteli, T. The Self-Organizing Genome: Principles of Genome Architecture and Function. Cell 2020, 183(1), 28-45. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa E., Mayor R. Collective cell migration in development. J Cell Biol. 2016, 212 (2), 143–155. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg M.V.C., Bourc’his D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 590–607. [CrossRef]

- Jambhekar, A.; Dhall, A.; Shi, Y. Roles and regulation of histone methylation in animal development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 625–641. [CrossRef]

- Nojima T., Proudfoot N.J. Mechanisms of lncRNA biogenesis as revealed by nascent transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 389–406. [CrossRef]

- Wang A. Conceptual breakthroughs of the long noncoding RNA functional system and its endogenous regulatory role in the cancerous regime. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2024, 5, 1706. [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Orom, U.A.; Cesaroni, M.; Beringer, M.; Taatjes, D.J.; Blobel, G.A.; et al. Activating RNAs associate with Mediator to enhance chromatin architecture and transcription. Nature 2013, 494, 497–501. [CrossRef]

- Billi, M.; De Marinis, E.; Gentile, M.; Nervi, C.; Grignani, F. Nuclear miRNAs: Gene Regulation Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6066. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Kwon, Y.S.; Nunez, E.; Cardamone, M.D.; Hutt, K.R.; Ohgi, K.A.; et al. Enhancing nuclear receptor-induced transcription requires nuclear motor and LSD1-dependent gene networking in interchromatin granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008, 105, 19199–19204. [CrossRef]

- Nunez, E.; Fu, X.D.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Nuclear organization in the 3D space of the nucleus—cause or consequence? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009, 19, 424–436. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.D. Non-coding RNA: a new frontier in regulatory biology. Natl Sci Rev. 2014, 1(2),190-204. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Eichler, G.; Bar-Yam, Y.; Ingber, D.E. Cell fates as high-dimensional attractor states of a complex gene regulatory network. Phys Rev Lett. 2005, 94, 128701. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, J.; Bachtiar, M.; Chong, S.S.; Lee, C.G.L. Architecture of polymorphisms in the human genome reveals functionally important and positively selected variants in immune response and drug transporter genes. Hum Genomics 2018, 12(1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Miao, Y.R.; Wu, X.; Luo, H.; Cao, W.; et al. lncRNASNP v3: an updated database for functional variants in long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51(D1), D192-D198. [CrossRef]

- Preskill, C.; Weidhaas, J.B. SNPs in microRNA binding sites as prognostic and predictive cancer biomarkers. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013, 18(4), 327-340. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Jeong, S.D.; Shin, C.H.; Cha, S.; Yu, A.; Kim, E.J.; et al. LINC02257 regulates malignant phenotypes of colorectal cancer via interacting with miR-1273g-3p and YB1. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 895. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Sun, T.; Hacisuleyman, E.; Fei, T.; Wang, X.; Brown, M.; et al. Integrative analyses reveal a long noncoding RNA-mediated sponge regulatory network in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2016, 7, 10982. PMID: 26975529; PMCID: PMC4796315. [CrossRef]

- Guarnerio, J.; Bezzi, M.; Jeong, J.C.; Paffenholz, S.V.; Berry, K.; Naldini, M.M.; et al. Oncogenic role of fusion-circRNAs derived from cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Cell 2016, 165(2), 289-302. Epub 2016 Mar 31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, C.S.; Varelas, X.; Monti, S. Altered RNA editing in 3' UTR perturbs microRNA-mediated regulation of oncogenes and tumor-suppressors. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 23226. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X., Zhang, Z., Chen, Y. et al. Current and future therapies for small cell lung carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2025, 18, 37. [CrossRef]

- Bernards, R.; Weinberg, R. Metastasis genes: A progression puzzle. Nature. 2002, 418(6900), 823. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.W.; Pattabiraman, D.R.; Weinberg, R.A. Emerging Biological Principles of Metastasis. Cell. 2017, 168(4), 670-691. [CrossRef]

- Birkbak, N.J.; McGranahan, N. Cancer genome evolutionary trajectories in metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2020, 37(1), 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ding, J.; Ma, Z.; et al. Quantitative evidence for early metastatic seeding in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2019, 51(7), 1113-1122. [CrossRef]

- Roche, J. The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer. Cancers. 2018, 10(2), 52. [CrossRef]

- Allgayer, H.; Mahapatra, S.; Mishra, B.; Swain, B.; Saha, S.; Khanra, S.; et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer metastasis: the status quo of methods and experimental models. Mol Cancer. 2025, 24, 167. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M.A.; Huang, R.Y-J.; Jackson, R.A.; Thiery, J.P. EMT: 2016. Cell. 2016, 166, 21–45. [CrossRef]

- Schnirman, R.E.; Kuo, S.J.; Kelly, R.C.; Yamaguchi, T.P.; Willert, K. Chapter Five - The role of Wnt s [ignaling in the development of the epiblast and axial progenitors. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Academic Press. 2023, 153, 145-180. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Kang, Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Dev Cell. 2019, 49(3), 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, M.C.; Brown, B.A.; Adair, S.A.; Bauer, T.W.; Lazzara, M.J. The kinase ERK plays a conserved dominant role in the heterogeneity of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells. Sci. Signal. 2025, 18, eads7002. [CrossRef]

- Khanbabaei, H.; Ebrahimi, S.; García-Rodríguez, J.L.; Ghasemi, Z.; Pourghadamyari, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Kristensen, L.S. Non-coding RNAs and epithelial mesenchymal transition in cancer: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 41(1), 278. [CrossRef]

- Gómez Tejeda Zañudo, J.; Guinn, M.T.; Farquhar, K.; Szenk, M.; Steinway, S.N.; Balázsi, G.; Albert, R. Towards control of cellular decision-making networks in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Phys. Biol. 2019, 16(3), 031002. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, W.; Tian, J.; Shu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y. Non-coding RNAs as key regulators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025, 13, 1544310. [CrossRef]

- Nadukkandy, A.S.; Blaize, B.; Kumar, C.D.; Mori, G.; Cordani, M.; Kumar. L.D. Non-coding RNAs as mediators of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in metastatic colorectal cancers. Cellular Signalling. 2025, 127, 111605. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ingber. D.E. A non-genetic basis for cancer progression and metastasis: self-organizing attractors in cell regulatory networks. Breast Dis. 2006, 26, 27-54. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Poe, D.; Yang, Y.; Hyatt, T.; Xing, J. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition proceeds through directional destabilization of multidimensional attractor. eLife. 2022, 11, e74866. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2022, 15, 129. [CrossRef]

- Pastushenko, I.; Brisebarre, A.; Sifrim, A.; Fioramonti, M.; Revenco, T.; Boumahdi, S.; et al. Identification of the tumour transition states occurring during EMT. Nature. 2018, 556(7702), 463–468. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.E. Survey for Activating Oncogenic Mutation Variants in Metazoan Germline. Genes. J Mol Evol. 2024, 92, 930–943. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. Revisiting the somatic mutation theory of cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2026, 27, 116. [CrossRef]

- Roy, L.; Chatterjee, O.; Bose, D.; Roy, A.; Chatterjee, S. Noncoding RNA as an influential epigenetic modulator with promising roles in cancer therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2023, 28, 103690. [CrossRef]

- Aznaourova, M.; Schmerer, N.; Schmeck, B.; Schulte, L.N. Disease-Causing Mutations and Rearrangements in Long Non-coding RNA Gene Loci. Front Genet. 2020, 11, 527484. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Gene expression profiling, genetic networks, and cellular states: an integrating concept for tumorigenesis and drug discovery. Mol Med. 1999, 77, 469–480. [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, C.P. Nitrogen mustards in the treatment of neoplastic disease; official statement. J Am Med Assoc. 1946, 131, 656-658. [CrossRef]

- Min, H.Y.; Lee, H.Y. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med. 2022, 54(10), 1670-1694. [CrossRef]

- Tregear, M.; Visco, F. Outcomes that matter to patients with cancer: living longer and living better. EClinicalMedicine. 2024 Sep 11;76:102833. [CrossRef]

- Piergentili, R.; Sechi, S. Targeting Regulatory Noncoding RNAs in Human Cancer: The State of the Art in Clinical Trials. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 471. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Ren, M. The Progress and Evolving Trends in Nucleic-Acid-Based Therapies. Biomolecules. 2025, 15(3), 376. [CrossRef]

- Das Adhikari, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Cui, Y. Recent advances in spatially variable gene detection in spatial transcriptomics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024, 23, 883-891. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Xiao, J.; Yu, T. A robust statistical approach for finding informative spatially associated pathways. Brief Bioinform. 2024, 25(6), bbae543. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).