1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is primarily caused by external forces that damage or degenerate brain cells, such as car accidents, falls, violent impacts, blows, vibrations, or the entry of foreign objects into the brain. The symptoms of TBI range from mild concussion to severe coma and death, and depending on the affected brain area, it can cause physiological, psychological, cognitive, and emotional abnormalities. These symptoms are typically evaluated by neurological examination combined with assessment of motor function, sensation, hearing, language, coordination, and mental status [

1,

2,

3]. Notably, TBI can also affect mood and cause depression, which is the most common psychological disease, affecting approximately 15%–20% of people during their life. Among all emotional diseases, depression is responsible for the main expense in insurance costs. Neuroimaging methods, such as computed tomography, are used to diagnose TBI and confirm the location of skull fractures, brain contusions, hemorrhages, or masses [

4,

5,

6]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an even more sensitive neuroimaging method that allows for finer differentiation of anatomical location, type of injury, and severity. Neuroimaging studies have revealed structural and metabolic abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex region of TBI patients that can cause depression [

7,

8,

9].

The main non-nerve cells in the brain are astrocytes and microglia, which are identified using the protein markers glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1), respectively. These cell types are strongly associated with neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, central pain sensitization, and the assessment of brain injury. Increased GFAP levels reflect astrocyte activation and are well-established markers of neuronal inflammation and injury. Similarly, microglia become activated when nerves are inflamed. These activated microglia are classified as M1 cells and result in increased Iba1 protein levels. Recent preclinical and clinical studies suggest that astrocyte and microglia undergo significant activation and proliferation after TBI [

10,

11,

12]. Mouse models of different stages of TBI show increased white cortex levels of both GFAP and Iba1. Excessive release of HMGB1 and S100B from astrocytes and microglia is thought to lead to neuroinflammation. Prolonged inflammation increases levels of NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein 3, which activates astrocytes and microglia. These changes result in persistent neurotransmission alterations that cause neurological dysfunction, ultimately increasing the risk of mood disorders such as depression [

13,

14,

15].

Adiponectin was reported to regulate glucose, enhance insulin sensitivity, anti-inflammation, and prevention of type 2 diabetes and metabolic diseases. When the brain is damaged, the immune system sends immune cells to repair tissue, which triggers a neuroinflammatory response. The release of adiponectin can reduce inflammation caused by astrocytes, microglia, and macrophages. Through its anti-inflammatory effects, adiponectin has also been shown to protect the heart, vascular system, intestines, lungs, and brain tissue [

16,

17,

18]. After it is released, adiponectin binds to the adiponectin 1 AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 receptors. Recent studies show that AdipoR1 receptors are mainly found in the brain, blood vessels, skeletal muscle, and heart, whereas AdipoR2 receptors are mainly found in the liver, arteries, and adipocytes. Studies of mice have demonstrated that adiponectin receptor deprivation results in glucose intolerance and hyperinsulinemia, confirming the role of this receptor in stabilizing carbohydrates and insulin. Adiponectin can directly activate the adaptor protein phosphotyrosine, which interacts with the PH domain and leucine zipper 1 (APPL1) to bind to the intracellular structure of AdipoR1 after activating AdipoR1, and then further activates AMPK and Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). APPL1 can then activate PPARα and the PI3K/Akt/FOXO1 signaling pathway [

19,

20,

21].

TRPV1 plays important roles in pain and heat transmission and, in blood vessels, participates in vasodilation, thermal sensation, and inflammation. TRPV1 was initially discovered in mammalian sensory neurons and is responsive to various stimuli including capsaicin, mechanical force, temperatures above 43 °C, low pH, anandamide, and inflammation. Genetic manipulation studies have further confirmed the association of TRPV1 with thermal pain sensitization. Capsaicin can dilate cerebral arteries to alleviate cerebral edema and blood–brain barrier damage. Overall, these findings suggest that the neuroprotective effect of capsaicin is related to blood vessels [

22,

23,

24]. Neuroinflammation can significantly activate TRPV1, resulting in increased expression of protein kinase A (PKA), PI3K, and PKC. These effects relate to the central sensitization process of pain caused by fibromyalgia, which involves both the peripheral and central nervous systems. PKCε is known to induce pain hypersensitization in nociceptors, thereby contributing to central sensitization and fibromyalgia pain. Mitogen-activated protein kinase is also involved in neuroinflammatory and pain signaling pathways and belongs to the family that includes extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway is also involved in central pain sensitization. These hormones are related to pain transmission, central sensitization, and neural plasticity. Activation of the cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) is thought to be involved in the generation of fibromyalgia pain [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Acupuncture, which has been used in Asia for over 3,000 years, is used to balance the flow of qi and blood and promote the health of meridians. Acupuncture methods have been improved to use stainless steel needles inserted into specific locations termed acupoints. Scientific studies have confirmed that acupuncture can relieve symptoms by stimulating peripheral nerves via stimulating connective tissue or muscles and transmitting information upward to the central nervous system, and the World Health Organization now recognizes its applicable for more than 100 diseases—particularly for pain management. EA is widely used to standardize stimulation conditions and shows anti-inflammatory effects. For example, EA stimulation of the Zusanli acupoint (ST36) can activate the vagus nerve-adrenal axis in mice and can effectively control inflammation in mouse sepsis models [

29,

30]. There is growing evidence that EA can treat inflammatory pain, neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Studies also support that acupuncture can treat comorbid pain and depression by reducing levels of inflammatory factors in the plasma, such as interleukins, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ [

34]. However, there is limited research on the molecular mechanisms through which EA can treat TBI.

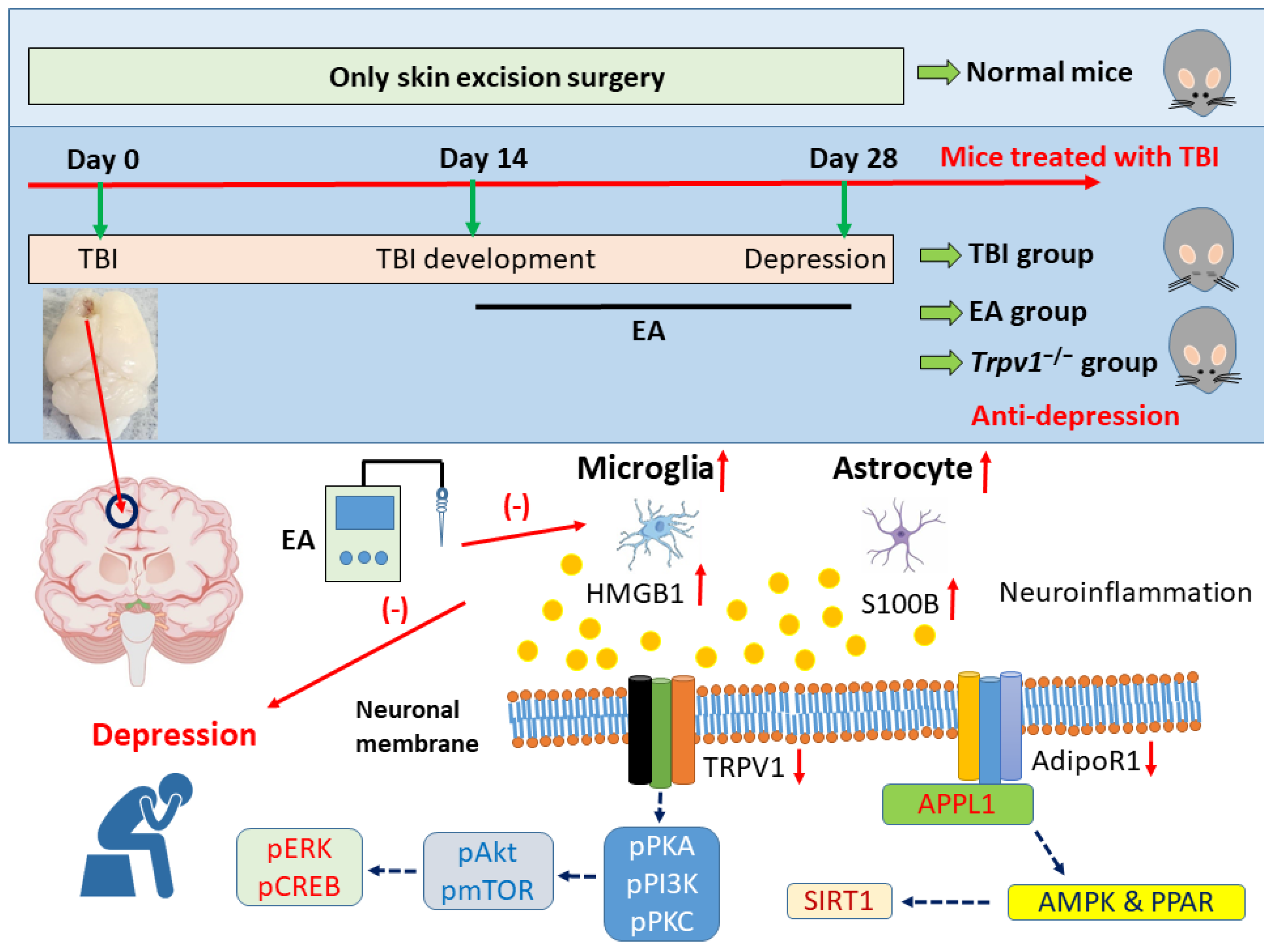

To address this research gap, this study investigated whether EA can treat TBI and comorbid depression in mice. We hypothesized that TBI would result in damage to the prefrontal cortex and lead to depression-like symptoms, and that EA or TRPV1 gene deletion would improve these symptoms. Specifically, we anticipated that EA would reduce neuroinflammation by releasing adiponectin and acting on the AdipoR1 signaling pathway. As predicted, TBI model mice showed increased protein levels of GFAP and Iba1 in the prefrontal cortex and decreased AdoR1 levels. These effects were also reflected by the expression levels of their signaling substances HMGB1 and S100B. This phenomenon also occurred in its downstream pathway APPL1-SIRT1-AMPK-PPAR, with a similar phenomenon observed in the TRPV1 signaling pathway. Importantly, both EA or Trpv1−/− were shown to reverse these brain injury-induced phenomena. Overall, this study provides evidence that EA treats TBI by modulating neuroinflammation via adiponectin. Given these findings, we propose that EA modulates the adiponectin signaling pathway and can thus be used to treat TBI-induced depression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Model of TBI and Comorbid Depression

We obtained 8–12 week old C57BL/6 wild-type mice, weighing approximately 18–22 grams, from BioLasco (Taipei, Taiwan Co., Ltd.). All mice were transported directly to the animal center and confirmed to have healthy fur and no wounds. Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment with a room temperature of 25 °C, humidity of 60%, and a controlled light/dark cycle of 12 hours (8:00 AM to 8:00 PM). Power calculations using G*Power 3.1.9.7 indicated that a minimum of nine mice per group was required to achieve a significance level of α = 0.05 and 80% statistical power. Mice were randomly assigned to four groups: normal group; TBI-induced depression comorbidity (TBI); TBI-induced depression comorbidity treated with 2 Hz EA (TBI + 2 Hz EA); or Trpv1−/− mice treated with TBI-induced depression comorbidity (TBI + Trpv1−/−). TBI was induced using the gravity impact model. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction concentration 5%, maintenance concentration 1%) and fixed in a stereotaxic apparatus. The left frontal cortex was exposed using a 3 mm drill and a gravity impact was performed at a point 1.95 mm posterior to the anterior fontanelle and 0.3 mm lateral to the midline. The impact conditions were as follows: impact head diameter 2 mm, impact depth 2 mm, impact velocity 5 m/s, and post-impact duration 100 ms (Impact ONE; Leica Biosystems, IL 60010, United States). After impact, the wound was sutured with surgical sutures and antibiotic ointment was applied to prevent infection. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Medical University, Taiwan (Approval No.: CMUIACUC-2023-066) and followed the Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences Press).

2.2. EA Treatment

EA was performed once daily for 14 days starting on the 15th day after brain injury. Prior to EA, mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and maintained under 1% isoflurane. Two 0.5-inch long 32G stainless steel needles (Yu-Kuang Chemical Industrial Co., Ltd., Taiwan) were vertically inserted into the bilateral ST36 acupoints, which are located 3–4 mm below the patella, between the fibula and tibia, anterior to the tibialis anterior muscle. The stainless steel needles were connected to the EA machine using a Trio 300 electrostimulator (Ito Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The EA conditions were as follows: 1 mA intensity, 2 Hz frequency, 150 μs pulse width, and continuous square wave pulses for 20 minutes. During EA stimulation, slight twitching of the muscles around the acupoint was observed.

2.3. Evaluation of Depressive Behaviors

The open field test (OFT) and forced swimming test (FST) were used to assess depressive behaviors in mice before and 4 weeks after TBI. Tests were performed using the Smart 3 system (TrackMot V.5.45; Signa Technology Co, Taipei, Taiwan) combined with video tracking software for analysis. The OFT used a 45 × 45 × 45 cm square white enclosed space made of acrylic plastic divided into nine equal-sized areas. Mice were initially placed in the central area and allowed to move freely for 15 min. The distance traveled across the central area, time spent in the central area, and total amount of movement in the open space were automatically recorded and analyzed by the software. Depressive behavior was indicated by a decrease in the number of times the mouse traveled across the central area or a shorter time spent in the central area. The FST was performed using a transparent plastic cylinder (47 cm high, 38 cm inner diameter) filled with 18 cm of 25 °C water. This water depth was sufficient to prevent the mouse’s tail from touching the bottom, preventing interference with the experimental results. The water was changed after each test. Each mouse performed a 5-min FST, with their trajectory and time spent stationary automatically recorded using software. Depressive behavior was indicated by an increased immobility time during the FST. After the test, the mice were removed, dried with a towel, and returned to their original cages.

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

The mouse cerebellum was dissected and tissues were placed on ice and stored at −80 ºC until protein extraction. Entire proteins were isolated in cold radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.02% NaN3, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (AMRESCO). The extracted proteins were subjected to 8% SDS-tris glycine gel electrophoresis and transmitted to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were initially incubated in 5% non-fat milk in TBS-T buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) followed by incubation a primary antibody in TBS-T with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. Peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit antibody or antimouse antibody (1: 5000) was used as the secondary antibody. Blots were imaged using a chemiluminescent substrate kit (PIERCE) and LAS-3000 Fujifilm system (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). β-actin or α-tubulin was used as an internal control. Finally, the protein concentration of the bands was measured using NIH Image J 1.54h software (Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.5. Immunofluorescence

Mice were euthanized with a 5% isoflurane and intracardially injected with 0.9% normal saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were immediately excised and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 ºC for 3 days. Subsequently, the samples were embedded in 30% sucrose for cryoprotection overnight at 4ºC, fixed in an optimal cutting temperature complex, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 ºC. Frozen tissues were cut into a 20 mm sections using a cryostat directly placed on glass slides. The sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated with a blocking solution consisting of 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.02% sodium azide for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were incubated overnight with the primary antibody (1:200, Alomone) for Iba1, TRPV1, and pERK in 1% BSA solution. Finally, the samples were incubated with the secondary antibody (1:500), 488-conjugated AffiniPure donkey antirabbit IgG (H + L) and 594-conjugated AffiniPure donkey antigoat IgG (H + L) for 2 h at room temperature and then fixed with cover slips for immunofluorescence visualization (Leica, DM500, CA 94539, USA) .

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 software (IBM, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of mean. Differences among all groups were tested by analysis of variance followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. Results with P < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first to demonstrate that TBI leads to increased neuroinflammation in the mPFC in mice. We observed significant increases in astrocytes, microglia, and their neurotransmitters HMGB1 and S100B. Neurotransmission dominated by AdipoR1 and TRPV1 was reduced by TBI. Overall, our findings support that EA can effectively alleviate neuroinflammation and improve impaired neurotransmission. Notably, similar results were observed in Trpv1 knockout mice.

TBI is commonly associated with mental and neurological abnormalities. While the mortality rate from severe TBI has significantly decreased due to the introduction of protective measures such as helmets, the mental, cognitive, and emotional sequelae caused by TBI of varying severity are increasing. The manifestations of TBI are highly complex and depend on the location of the impact [

35]. These can include symptoms of emotional instability such as irritability, impulsivity, extreme anger, suicidal tendencies, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. Recent articles have indicated that SERPINE1 is an important blood marker for predicting TBI-induced depression. Using a gene expression omnibus dataset for a TBI with comorbid depression sample, the authors performed a weighted gene co-expression network analysis that identified factors related to circadian rhythm function, consistent with the idea that TBI and depression are influenced by circadian rhythms. By inducing TBI and depression in an animal model, they demonstrated that inhibiting SERPINE1 expression reduced the protein expression levels of claudin-1 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which improved treating TBI and depression comorbidity. They also confirmed that excessive SERPINE1 expression activates neutrophils, which affects circadian rhythms and causes comorbid causing TBI and depression [

36]. Antidepressants are currently the main treatment for comorbid TBI and depression. However, due to the complexity of the TBI site and underlying mechanism, treatment efficacy is poor and there are often concerns about side effects, safety, and tolerability. Methylphenidate, which was originally developed as a central nervous system stimulant for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, is reported to have better therapeutic effects in the early stages following mild to moderate brain injury [

37]. Our results support that TBI does lead to depressive comorbidity in mice. We further found that EA can effectively alleviate TBI-induced depression. Similar results were observed for

Trpv1 knockout, supporting that EA treats depression through effects on the TRPV1 pathway.

Melatonin has recently emerged as a novel neuroprotective mechanism for treating TBI and serves as a potential new direction for treating TBI-induced depression. The heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) signaling pathway is also closely related to the occurrence of depression. CREB activity in nucleus accumbens (NAc) primarily governs reward and motivation. A previous study demonstrated that melatonin can effectively treat TBI-induced depressive behavior and reduce pCREB protein levels in the NAc. This study further demonstrated that intraventricular injection of HO-1-specific inhibitors can mitigate the neuroprotective effects of melatonin. Melatonin has been shown to reduce the expression levels of A1 astrocyte and IL-6 in NAc after TBI, and these changes can be reversed by HO-1-specific inhibitors [

38]. Du et al. used RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) technology to study the role of circular RNAs in TBI-induced depression. They observed reductions in the level of circSpna2 expression in the plasma of TBI mice, which was proportional to the severity of depression. Knock-down of circSpna2 was found to exacerbate depressive symptoms in TBI mice. They revealed that circSpna2 can bind to the ubiquitin ligase Keap1, thereby regulating the Nrf2-Atp7b signaling pathway and affecting cuproptosis. These results suggest that circSpna2 plays an important role in copper apoptosis and may offer a new therapeutic direction for TBI-induced depression [

39]. Zhou et al. reported a statistically significant increase in FOXO1 protein expression in neutrophils in TBI patients and mouse models. However, neutrophils with high FOXO1 concentrations showed increased infiltration in both the acute and chronic phases after TBI that were proportional to the severity of TBI and promoted depressive episodes. In the acute phase, FOXO1 increased cytoplasmic Versican expression and interacted with the apoptosis regulator B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2)-associated X protein (BAX) to prevent apoptosis. These findings of higher FOXO1 levels in neutrophils in both acute and chronic TBI highlight the importance of regulating neutrophils in this condition [

40]. In the present study, our molecular analyses confirmed that TBI induces a neuroinflammatory response in the PFC and decreases in the AdipoR1 and TRPV1 signaling pathways, leading to comorbid depression. We further demonstrated that EA or

Trpv1−/− can reduce the levels of astrocyte (indicated by GFAP), microglia (Iba1), and their signaling mediators HMGB1 and S100B. Moreover, EA or

Trpv1−/− can further increase AdipoR1–APPL1 downstream to the SIRT1/AMPK/PPAR pathway. We observed similar results for the TRPV1 signaling pathway.

Boyko et al. reported that TBI rats have significantly worse neurological function scores (NSS) at 48 h compared to control animals; however, after 1 month, neurological function was similar in the two groups. MRI revealed that TBI rats have more severe cerebral edema and greater blood–brain barrier damage than normal rats. Depressive symptoms were confirmed by a significantly lower sucrose intake by TBI rats compared to control rats, and the reduced time spent in the open arm and fewer entries indicated that TBI rats also had higher levels of anxiety [

41]. A recent study reported the effects of controlled cortical impact-induced TBI in normal mice and IL-10 gene-deficient mice. Serum IL-10 concentrations were significantly elevated in normal male (but not female) mice after TBI. Male

IL-10 gene-deficient mice also showed a larger injured volume than control mice and they exhibited poorer performances of sensorimotor tasks and cognitive tests and showed higher anxiety- and depression-related behaviors. Importantly, male

IL-10 gene-deficient mice showed significantly increased levels of GFAP and Iba1 proteins in the brain injury area and a significantly lower number of NeuN-positive cells, indicating greater cell death. These results confirm that IL-10 deficiency exacerbates cognitive and emotional function after TBI through an inflammatory response caused by stellate cell and glial cell proliferation [

42].

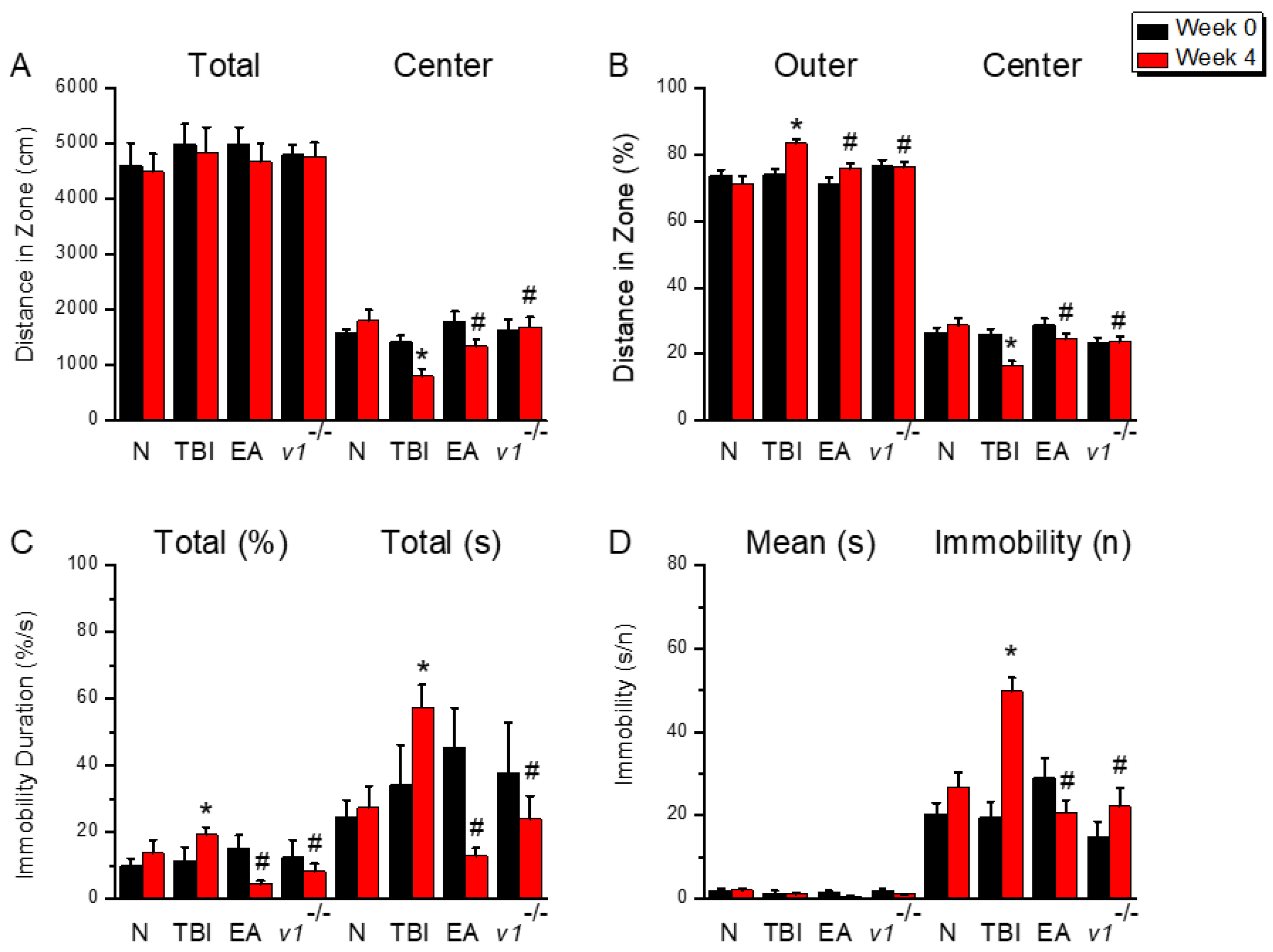

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of depressive behavior exhibited by mice after TBI. (A) OFT shows the total walking distance and distance into the central region; (B) OFT shows the percentage of time mice entered the outer and central regions. (C) Percentage of total immobility and time spent by mice during the FST behavioral test; (D) Average time and number of immobility during the FST behavioral test. *Significant difference compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant difference compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 9 per group.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of depressive behavior exhibited by mice after TBI. (A) OFT shows the total walking distance and distance into the central region; (B) OFT shows the percentage of time mice entered the outer and central regions. (C) Percentage of total immobility and time spent by mice during the FST behavioral test; (D) Average time and number of immobility during the FST behavioral test. *Significant difference compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant difference compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 9 per group.

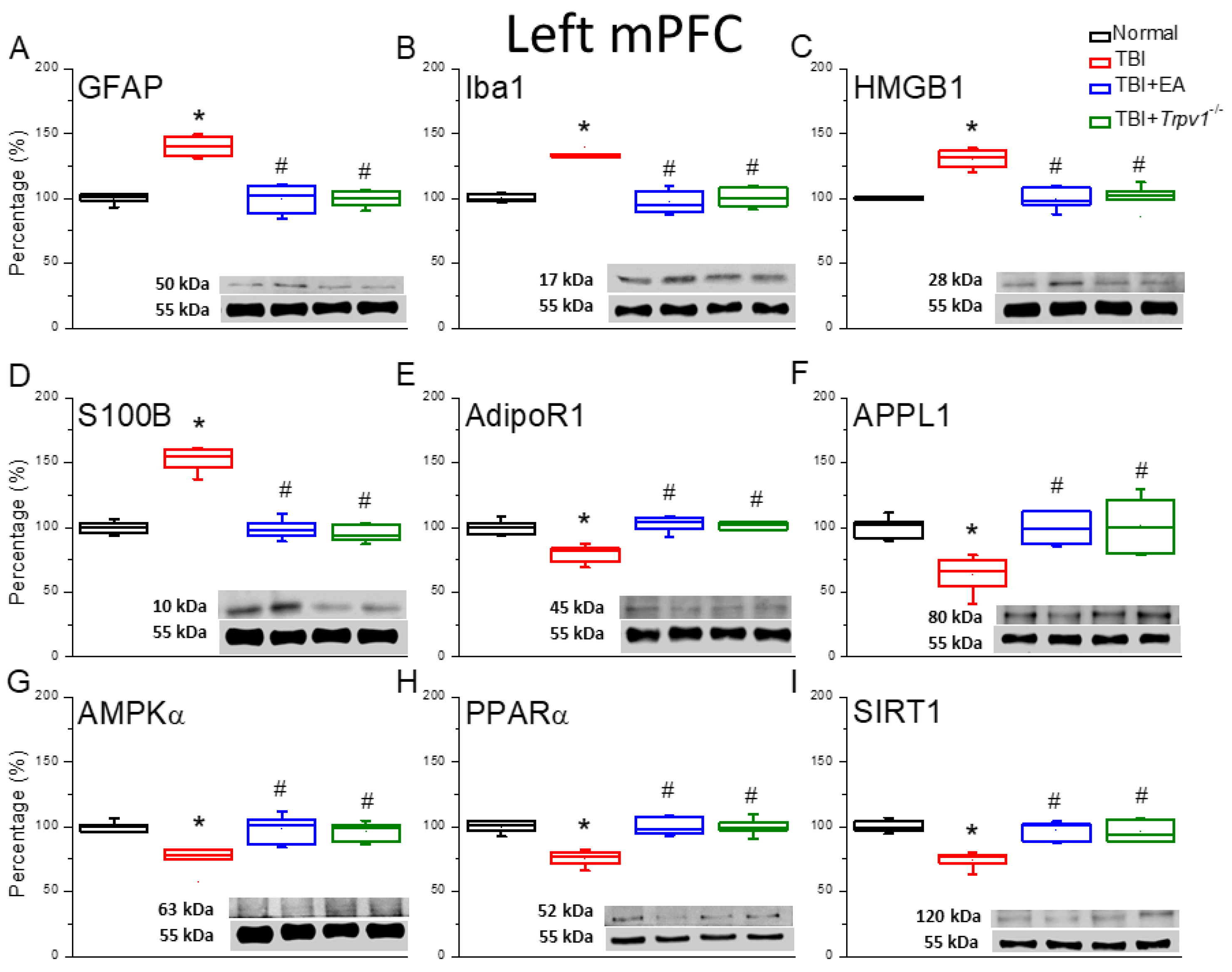

Figure 2.

Neuroinflammation in the left mPFC region of mice; protein expression of AdipoR1-related molecules. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+ Trpv1−/− group. (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) HMGB1, (D) S100B, (E) AdipoR1, (F) APPL1, (G) AMPKα, (H) PPARα, (I) SIRT. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

Figure 2.

Neuroinflammation in the left mPFC region of mice; protein expression of AdipoR1-related molecules. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+ Trpv1−/− group. (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) HMGB1, (D) S100B, (E) AdipoR1, (F) APPL1, (G) AMPKα, (H) PPARα, (I) SIRT. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

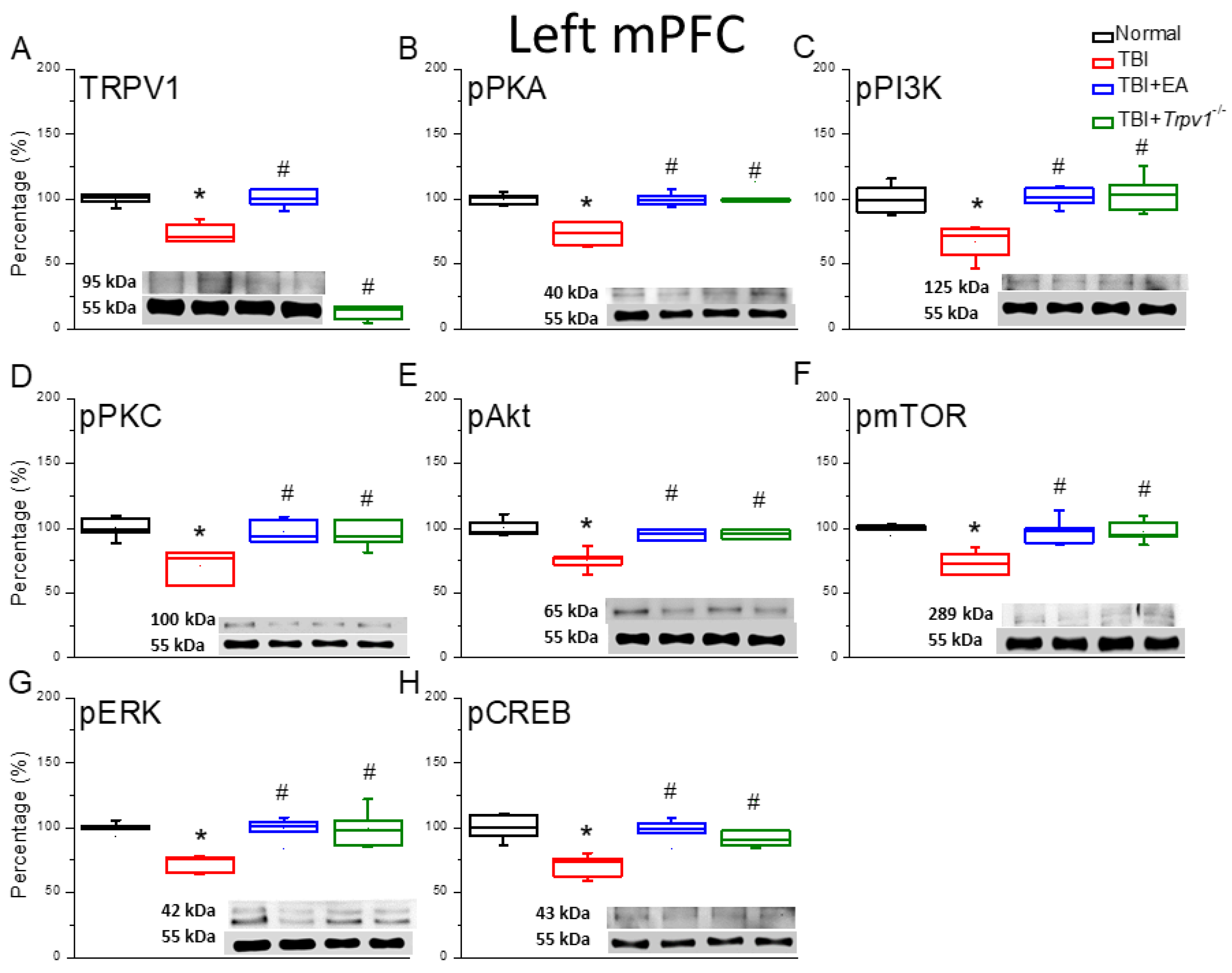

Figure 3.

Protein expression of TRPV1-related molecules in the left mPFC region of mice. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+ Trpv1−/− group. (A) TRPV1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, (H) pCREB. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

Figure 3.

Protein expression of TRPV1-related molecules in the left mPFC region of mice. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+ Trpv1−/− group. (A) TRPV1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, (H) pCREB. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

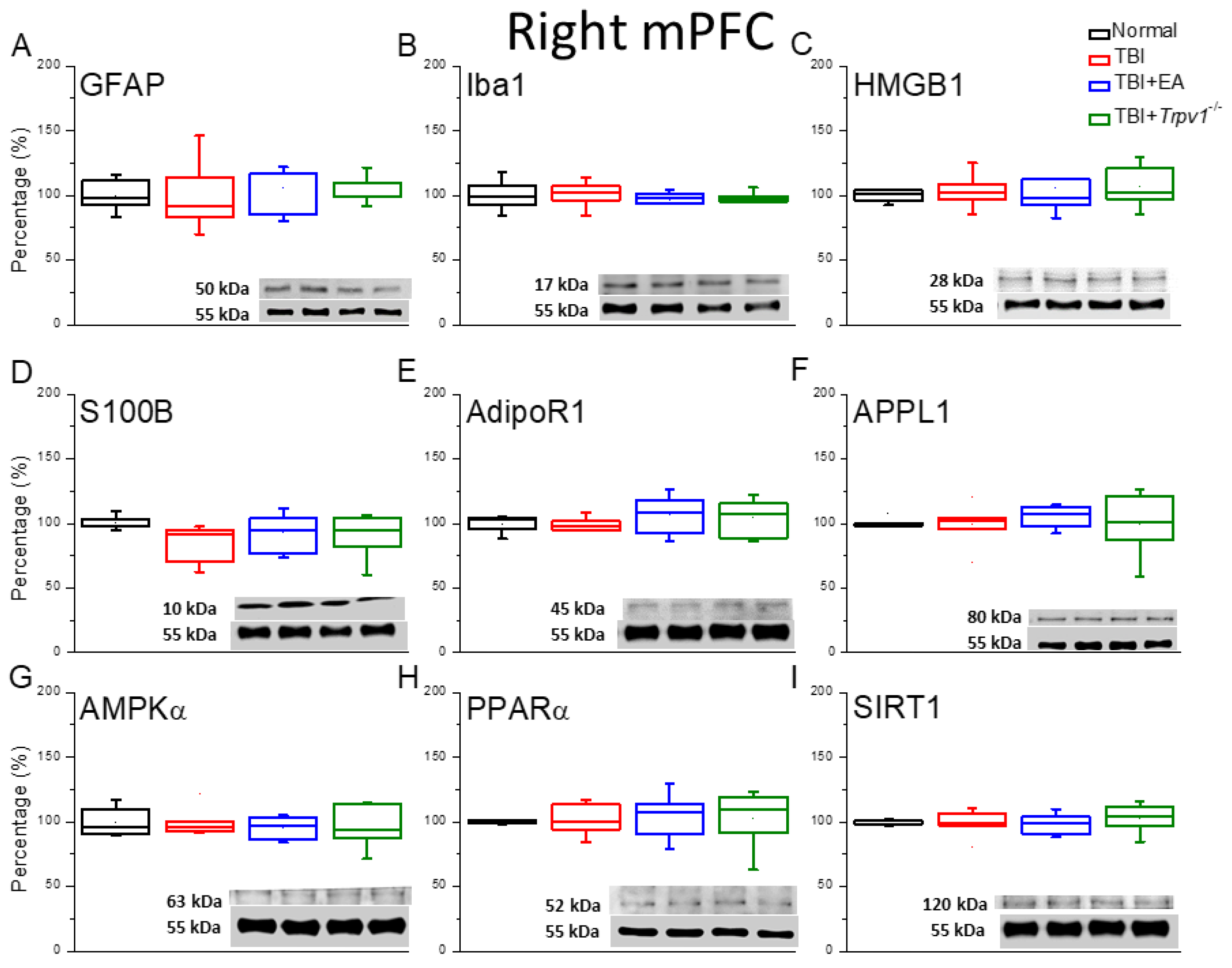

Figure 4.

Neuroinflammation in the right mPFC region of mice; protein expression of AdipoR1-related molecules. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+Trpv1−/− group. (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) HMGB1, (D) S100B, (E) AdipoR1, (F) APPL1, (G) AMPKα, (H) PPARα, (I) SIRT. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

Figure 4.

Neuroinflammation in the right mPFC region of mice; protein expression of AdipoR1-related molecules. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+Trpv1−/− group. (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) HMGB1, (D) S100B, (E) AdipoR1, (F) APPL1, (G) AMPKα, (H) PPARα, (I) SIRT. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

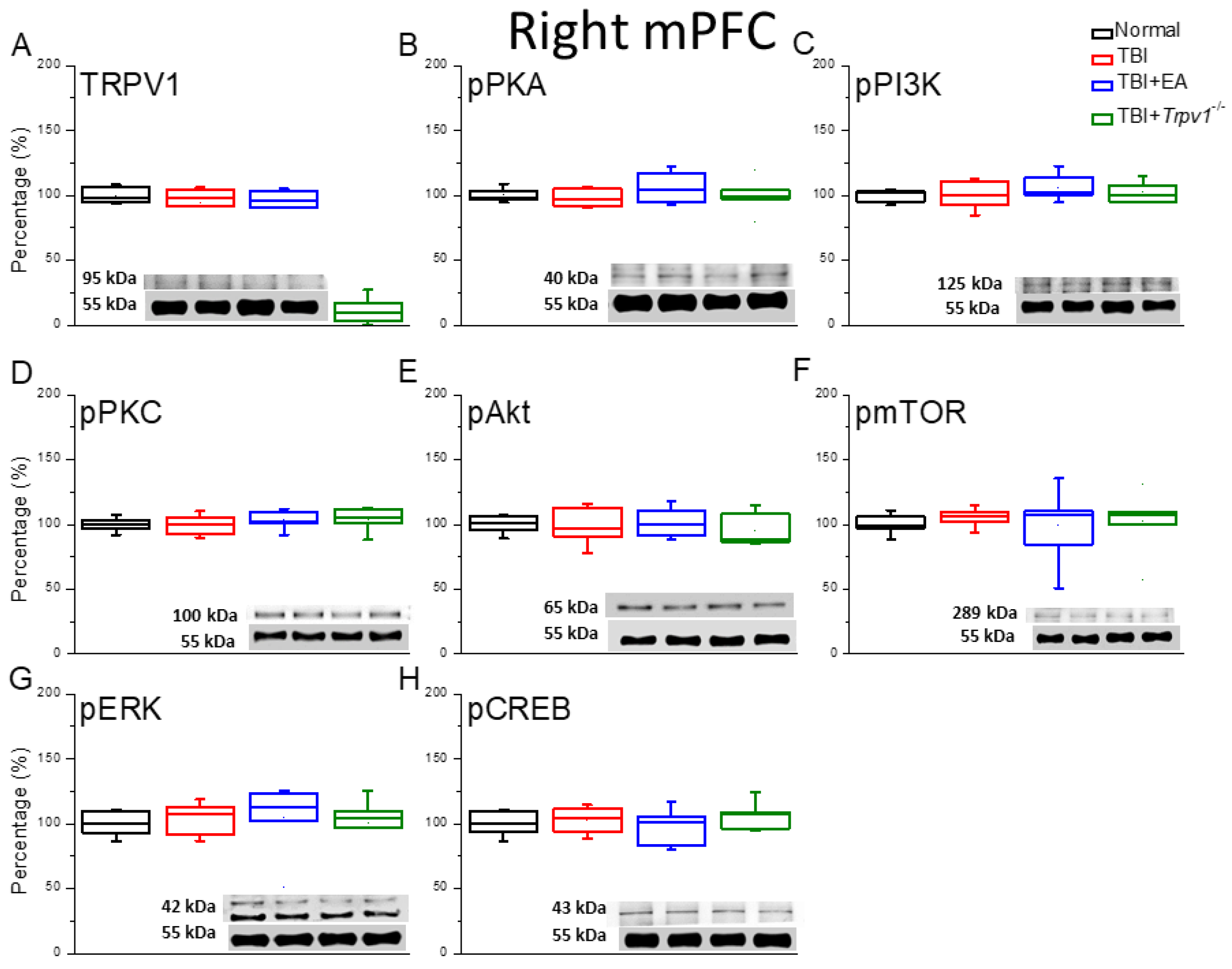

Figure 5.

Protein expression of TRPV1-related molecules in the right mPFC region of mice. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+ Trpv1−/− group. (A) TRPV1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, (H) pCREB. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

Figure 5.

Protein expression of TRPV1-related molecules in the right mPFC region of mice. Western blotting assay included four lanes: normal group, TBI group, TBI+EA group, and TBI+ Trpv1−/− group. (A) TRPV1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, (H) pCREB. *Significant differences compared to the normal mouse group at the same time point. #Significant differences compared to the TBI mouse group at the same time point. n = 6 per group.

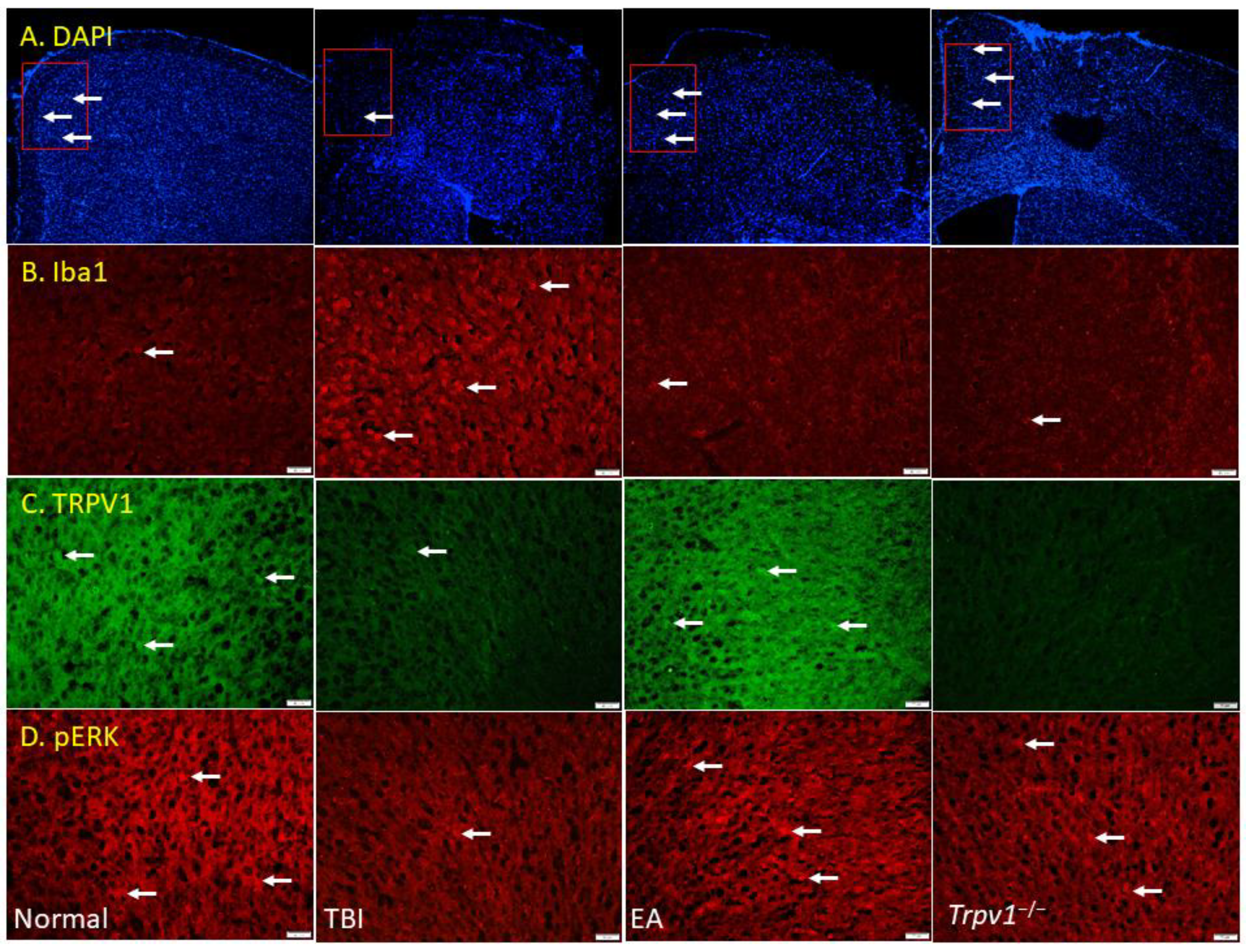

Figure 6.

Fluorescence intensities of TRPV1 and related molecules labeled in the mouse left mPFC. Immunofluorescence staining of (A) DAPI, (B) Iba1, (C) TRPV1, and (D) pERK in the mouse mPFC (blue, red, or green). There were significant reduced in DAPI, TRPV1, and pERK protein levels of TBI mice. There was significant increase in Iba1 protein levels of TBI mice. n = 3 in all groups.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence intensities of TRPV1 and related molecules labeled in the mouse left mPFC. Immunofluorescence staining of (A) DAPI, (B) Iba1, (C) TRPV1, and (D) pERK in the mouse mPFC (blue, red, or green). There were significant reduced in DAPI, TRPV1, and pERK protein levels of TBI mice. There was significant increase in Iba1 protein levels of TBI mice. n = 3 in all groups.

Figure 7.

Graphic diagram of EA in TBI-induced depression via neuroinflammation, AdipoR1, and TRPV1 signaling pathways.

Figure 7.

Graphic diagram of EA in TBI-induced depression via neuroinflammation, AdipoR1, and TRPV1 signaling pathways.