Introduction

Context: Findings from Paper 1

In the first paper of this trilogy, we established that anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) constitute a reproducible morphological–histological phenotype distinct from both conventional antemortem thrombi and ordinary postmortem clots. Using blinded, multi-site analyses, those structures were shown to form elongated, lumen-conforming casts with characteristic elastic behaviour and fibrinous lamination, but with unusually sparse cellular inclusion. While these findings demonstrate that AICs are structurally and histologically anomalous, morphology and histology alone cannot determine the biochemical nature of the matrix from which such structures are formed. Structural appearance defines form, but not composition. Accordingly, an independent line of evidence is required to assess whether AICs are consistent with canonical fibrin-based clot biochemistry or represent a materially distinct intravascular entity.

Taken together, these gross morphological and histological features establish AICs as a coherent and reproducible structural phenotype formed under conditions of active blood flow, but they do not resolve the biochemical identity of the material comprising the casts themselves. Multiple distinct matrices can give rise to superficially similar fibrillar architectures when viewed histologically. Consequently, structural characterization alone cannot determine whether AICs are composed predominantly of canonical fibrin or whether they incorporate a materially distinct biochemical framework.

In this context, morphology and histology define structural form, but they do not, by themselves, determine biochemical composition.

Why Elemental Analysis Is the Next Logical Step

(i) Elements as Orthogonal Evidence to Morphology and Histology

Morphological and histological analyses provide essential information about the structural organisation of biological materials but are intrinsically limited in their ability to resolve chemical composition. Distinct biochemical matrices can adopt superficially similar fibrillar architectures when subjected to comparable hemodynamic conditions, fixation, and staining protocols. As a result, structural appearance alone cannot discriminate reliably between a protein-dominant clot, a protein–mineral hybrid, or a matrix substantially diluted by non-protein constituents. Elemental analysis offers an orthogonal evidentiary axis that is independent of tissue architecture and staining behaviour, directly probing the atomic composition of the material itself rather than its visual form. By quantifying elemental abundances and ratios, elemental analysis can therefore test whether the AICs identified in Paper 1 are chemically consistent with canonical fibrin-based thrombi or whether they occupy a distinct compositional class.

(ii) Elemental Stoichiometry as a Constraint on Biochemical Identity

Elemental stoichiometry imposes first-principles constraints on the biochemical identity of biological matrices. Proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and mineral phases each exhibit characteristic elemental signatures that reflect their underlying molecular composition. In particular, protein-rich matrices are defined by relatively high nitrogen content and low sulfur abundance determined by amino-acid composition, while oxygen-rich and phosphorus-bearing materials indicate contributions from carbohydrate moieties, phosphate groups, inorganic polyphosphates, or mineral-associated phases. Because these elemental relationships arise directly from atomic composition, they cannot be altered by staining, dehydration, or histological processing. Comparison of measured elemental ratios against theoretical stoichiometry derived from known biomolecules—such as fibrinogen—therefore provides a powerful constraint on the fraction of protein that can plausibly constitute a given material. In this way, elemental analysis enables quantitative assessment of whether AICs are compatible with a predominantly fibrin-based clot or whether their bulk composition requires substantial non-protein contributions.

(iii) Precedent: Elemental Signatures Distinguish Clot Subtypes, Mineralisation, and Foreign Matrices

Prior studies demonstrate that elemental profiling can distinguish among physiologically and pathologically distinct clot types, as well as between biological and non-biological matrices. Analyses of platelet-rich fibrin clots show elemental patterns dominated by carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen, with minor contributions from sodium, phosphorus, and sulfur, consistent with an organic proteinaceous scaffold containing entrained electrolytes. In contrast, thrombi recovered from clinical settings such as ischemic stroke may exhibit localized calcium–phosphate enrichment indicative of secondary mineral deposition, while retaining an otherwise protein-dominant bulk composition. Elemental methods are also routinely used to identify foreign materials or exogenous polymers, which display elemental ratios incompatible with endogenous biomolecules. Together, these precedents establish elemental composition as a validated and discriminating tool for classifying clot matrices and assessing whether anomalous specimens conform to known biological categories or represent materially distinct entities.

What Elemental Analysis Can—and Cannot—tell Us

Elemental analysis provides a direct measure of the atomic composition of a material and, as such, can robustly identify deviations from the elemental proportions expected of canonical protein-based clots. By comparing measured elemental ratios with theoretical stoichiometry derived from known biomolecules, elemental data can reveal whether a specimen is broadly consistent with a fibrin-dominant matrix or whether its bulk composition requires substantial non-protein contributions. In this context, elemental analysis is particularly effective for detecting systematic departures from expected nitrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and phosphorus levels, which together constrain the plausible biochemical class of the material.

Beyond simple classification, elemental analysis can also identify relative enrichment and depletion patterns across elements that are mechanistically informative without being molecularly specific. Elevation of phosphorus, depression of sulfur, or imbalance within the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen triad can indicate incorporation of phosphate-bearing species, dilution of protein content, or enrichment of oxygen-rich organic or inorganic components. When observed consistently across samples and laboratories, such patterns provide strong evidence of compositional divergence from ordinary thrombi, even in the absence of absolute reference values for normal postmortem clots.

At the same time, elemental analysis has clear and important limitations. It cannot identify specific proteins, distinguish among protein isoforms, or resolve the molecular architecture or bonding states of the constituents detected. Elemental measurements alone cannot determine whether observed phosphorus arises from polyphosphate, phospholipids, nucleic acids, or mineral phases, nor can they specify which proteins contribute the detected nitrogen or sulfur. Consequently, while elemental analysis can establish whether AICs are compositionally compatible with a canonical fibrin matrix or require an abnormal framework, it cannot define the molecular identities of the components involved. Resolution of protein composition and relative abundance therefore requires complementary proteomic analysis, which is addressed in the third paper of this series.

Aim of the Study

The aim of this study was to determine the elemental composition of AICs using blinded, multi-site elemental analysis and to assess whether their elemental signatures are consistent with those expected for canonical fibrin-based thrombi. By benchmarking measured elemental ratios against theoretical fibrinogen stoichiometry and available empirical references, this work seeks to establish whether AICs conform to a predominantly proteinaceous clot matrix or exhibit compositional features indicative of an abnormal biochemical framework.

Materials and Methods

Sample Continuity with Paper 1

The anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) analyzed in the present study were drawn from the same sample pool, or from a directly overlapping subset, as those characterised morphologically and histologically in the first paper of this trilogy. Specimen acquisition, initial triage, and coding procedures were therefore identical across both studies, ensuring continuity of material and comparability of findings. No new sampling pathways were introduced for the elemental analyses reported here.

All samples were assigned coded identifiers at the point of collection, and these identifiers were retained throughout subsampling, distribution, and analysis. Blinding was maintained for all elemental determinations, with participating laboratories receiving no information regarding sample provenance, morphological characteristics, or study hypotheses. Cross-referencing of sample identifiers between Paper 1 and the present study was performed only after completion of the elemental analyses, allowing structural and compositional findings to be integrated without compromising analytical independence.

Consistent with the scope of this paper, gross morphological and histological features of the AICs are not redescribed here and are presented in detail in the preceding study. The present work focuses exclusively on elemental composition, using the established sample framework to assess whether the anomalous structures previously identified are chemically consistent with canonical fibrin-based thrombi or represent a distinct compositional class.

Sample Preparation for Elemental Analysis

Subsamples of anomalous intravascular casts were prepared for elemental analysis using standardized protocols appropriate for biological tissues. Following initial handling, specimens were air-dried or gently dried under controlled conditions to remove free moisture prior to digestion, enabling consistent mass normalization across samples. Dried material was then subjected to closed-vessel, microwave-assisted acid digestion using ultra-pure nitric acid with hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizing agent, producing clear solutions suitable for elemental determination by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

To minimize exogenous contamination, all sample handling and preparation steps were conducted using low-contamination practices. Acid-washed fluoropolymer or PTFE vessels were employed throughout, reagents were of trace-metal or ultra-pure grade, and all containers and tools were pre-rinsed with dilute acid and ultra-pure water. No hydrofluoric acid or other reagents associated with siliceous or inorganic matrices were used, consistent with standard protocols for biological materials.

Quality control measures included the use of procedural blanks, reagent blanks, and, where applicable, matrix-matched spikes and preparation duplicates to monitor contamination, recovery, and analytical precision. These controls were processed alongside samples within each analytical run to ensure that measured elemental signals reflected intrinsic sample composition rather than preparation artifacts.

Elemental Analysis Technique

Elemental determinations were performed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) under harmonised protocols across participating laboratories. Analyses were conducted on digested samples introduced in an acid matrix appropriate for biological materials, with instrument operating conditions optimized for sensitivity across both major and trace elements.

The analytical suite included bulk elements relevant to biological matrix classification (carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur), together with physiologically relevant metals and electrolytes (e.g., sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc) and selected trace elements as required to assess potential contamination or exogenous contributions. This panel allowed evaluation of both the dominant biochemical framework of the casts and secondary elemental patterns informative for comparison with whole-blood and fibrin-based reference values.

Calibration was performed using multi-element standards prepared in a matched acid matrix over concentration ranges bracketing those expected in the samples. Internal standards were applied to correct for instrumental drift and matrix effects, and calibration verification standards were analysed periodically throughout each run to confirm analytical stability. Elemental concentrations were accepted only when quality control criteria for calibration linearity, recovery, and precision were met, ensuring that reported values reflected true sample composition rather than analytical artefact.

Results

Global Elemental Profile of Anomalous Intravascular Casts

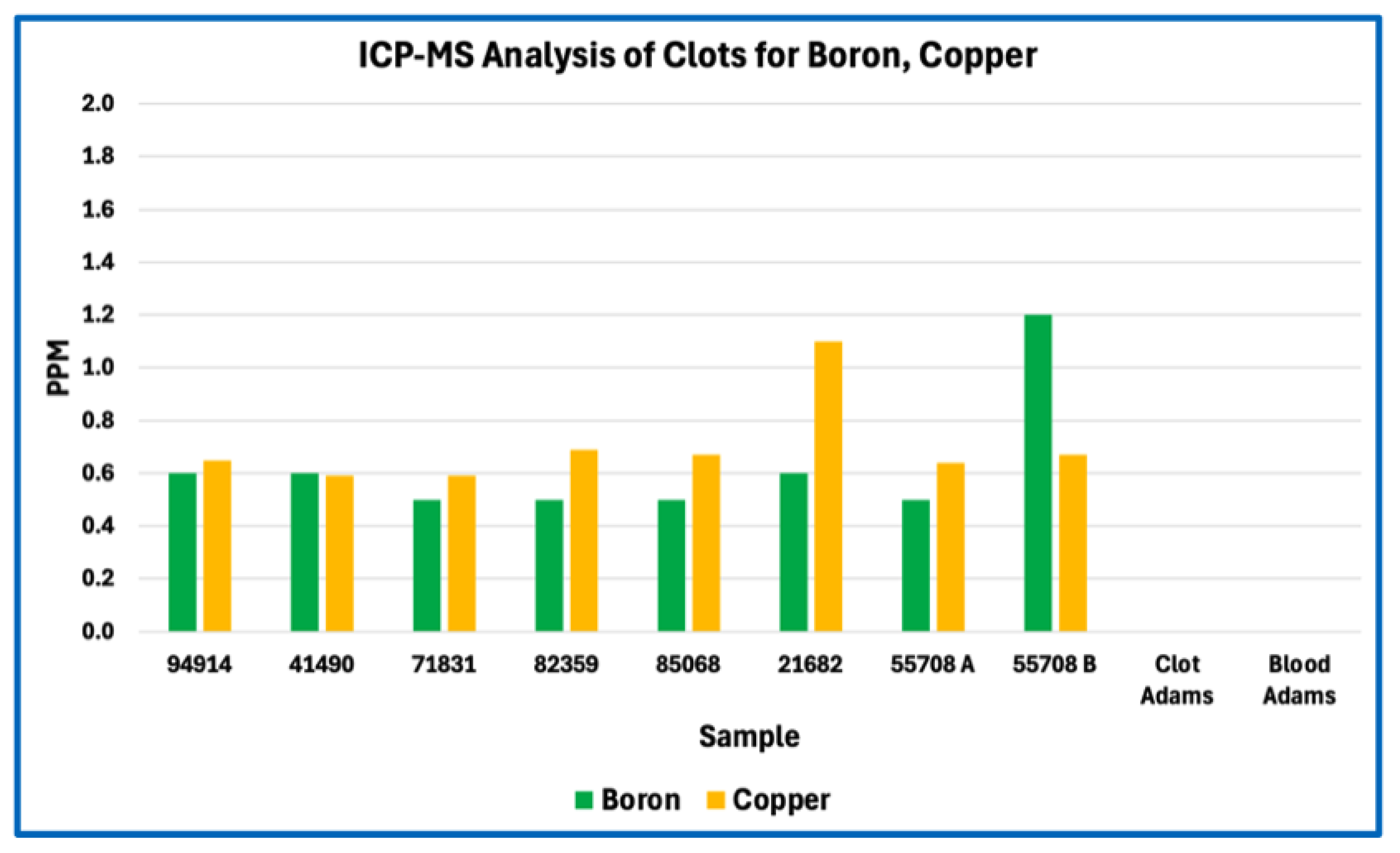

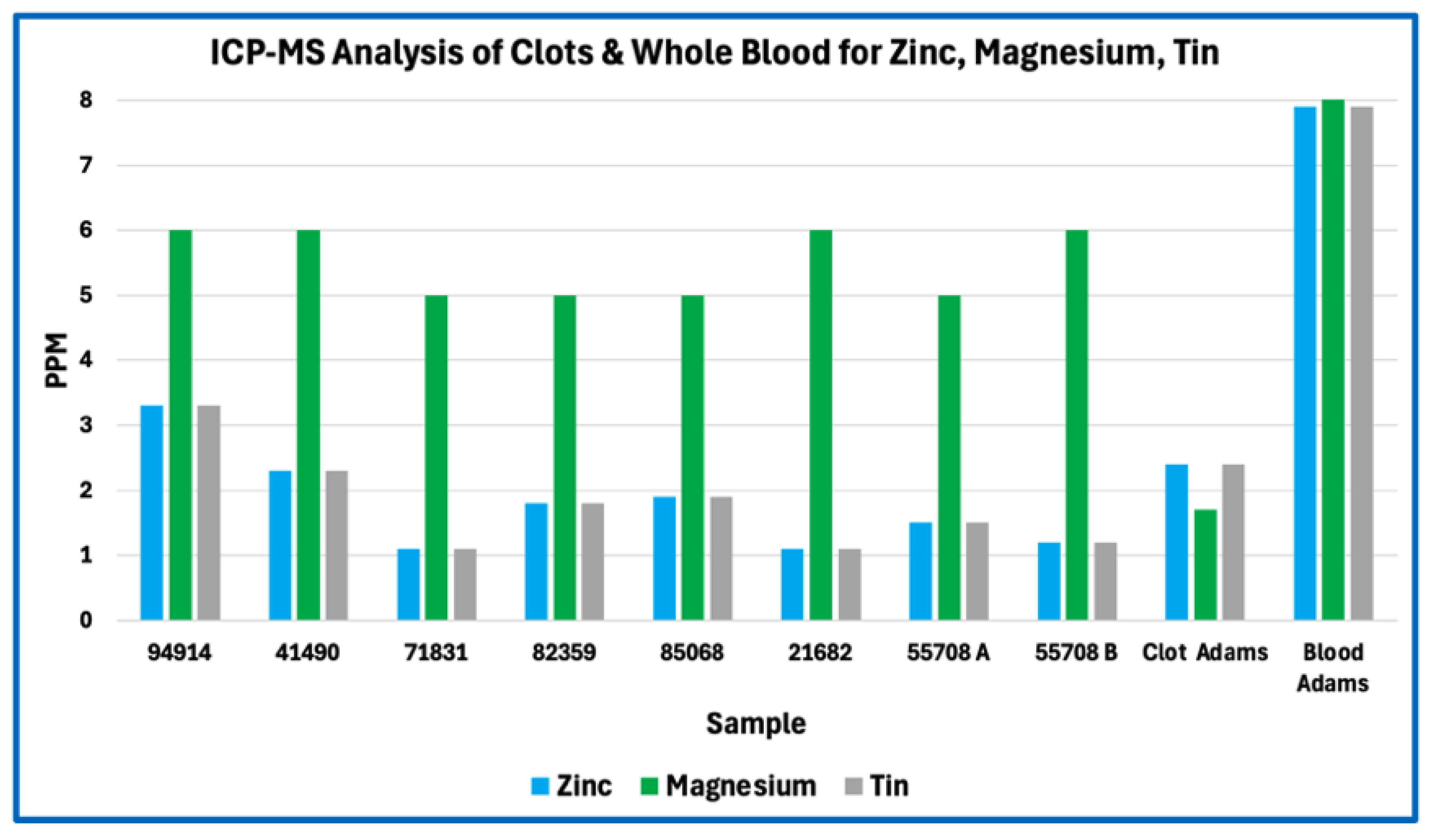

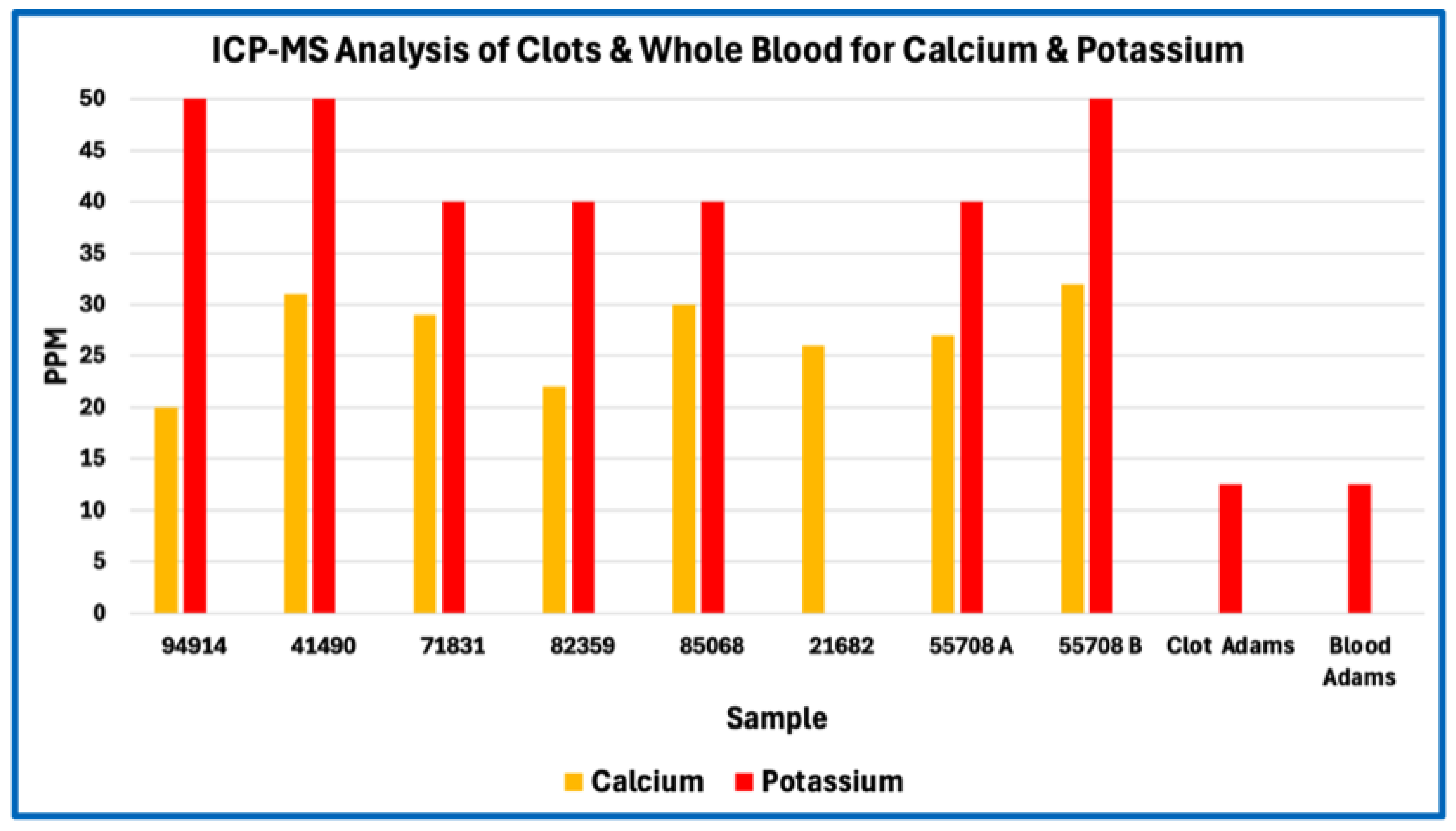

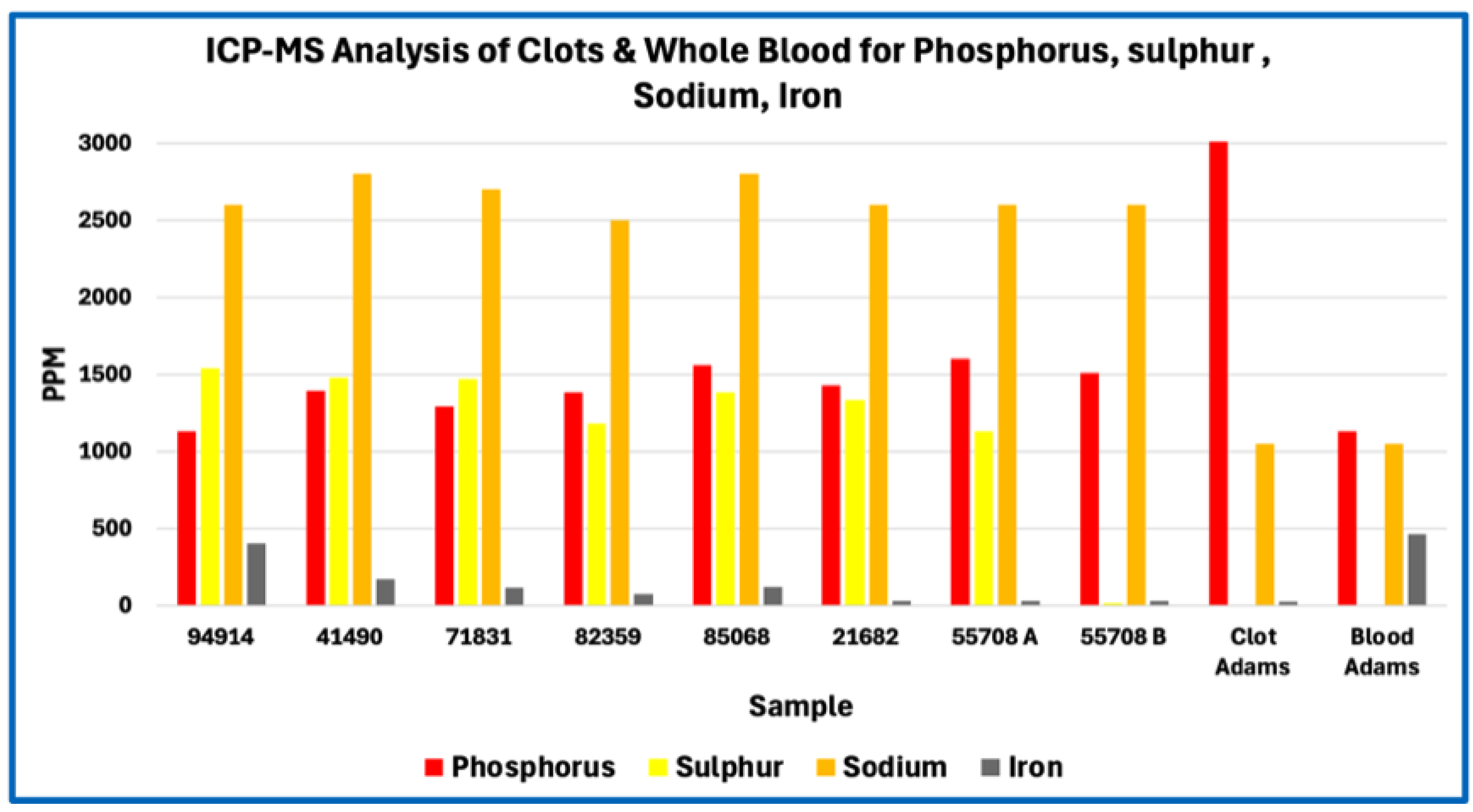

Elemental analysis of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) revealed a broadly biological elemental spectrum dominated by light elements and physiologically common electrolytes, with no evidence of exotic or non-biogenic metals at bulk levels. Across all samples analysed, the principal detected elements included phosphorus, sulfur, sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, copper, boron, and aluminium, together with the expected background contributions from carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen inherent to organic matrices.

In absolute concentration terms, sodium and phosphorus were among the most abundant measured elements, followed by sulfur, calcium, potassium, iron, and magnesium. Trace metals such as zinc, copper, boron, tin, and aluminium were present at low parts-per-million or sub-ppm levels consistent with physiological background or incidental environmental exposure rather than selective incorporation. No single element exhibited concentrations suggestive of synthetic polymers, industrial fillers, or foreign particulate matrices.

When expressed as relative abundance patterns, the elemental profiles of AICs showed a consistent organization across samples. Phosphorus and sodium clustered at higher relative proportions than would be expected for a purely proteinaceous fibrin matrix, whereas sulfur and nitrogen (where measurable by complementary methods) were proportionally depressed relative to first-principles fibrinogen stoichiometry. Calcium, potassium, and magnesium occurred at levels compatible with entrained plasma electrolytes and postmortem redistribution rather than extensive mineralization. Iron levels varied in a manner consistent with residual hemoglobin or erythrocyte degradation products rather than anomalous iron accumulation.

Inter-sample consistency was high for the dominant compositional features. Although absolute concentrations varied across individual specimens, the relative ordering of major elements—particularly the prominence of phosphorus and sodium and the relative depression of sulfur—was preserved across samples and laboratories. Variance analyses demonstrated that dispersion for most elements fell within ranges expected for postmortem biological materials subject to differing handling and dehydration histories, without evidence of bimodal or outlier-driven distributions.

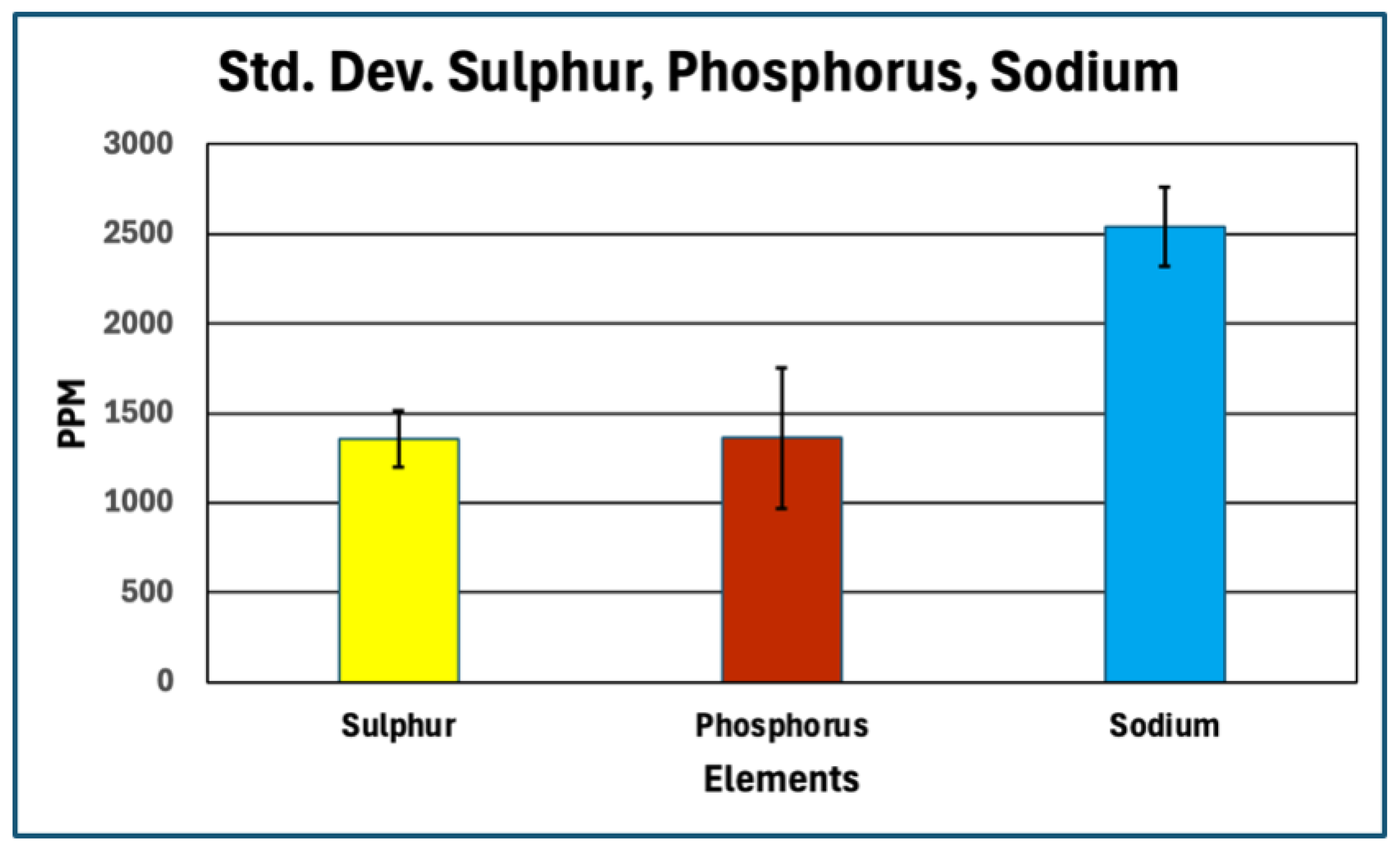

Across

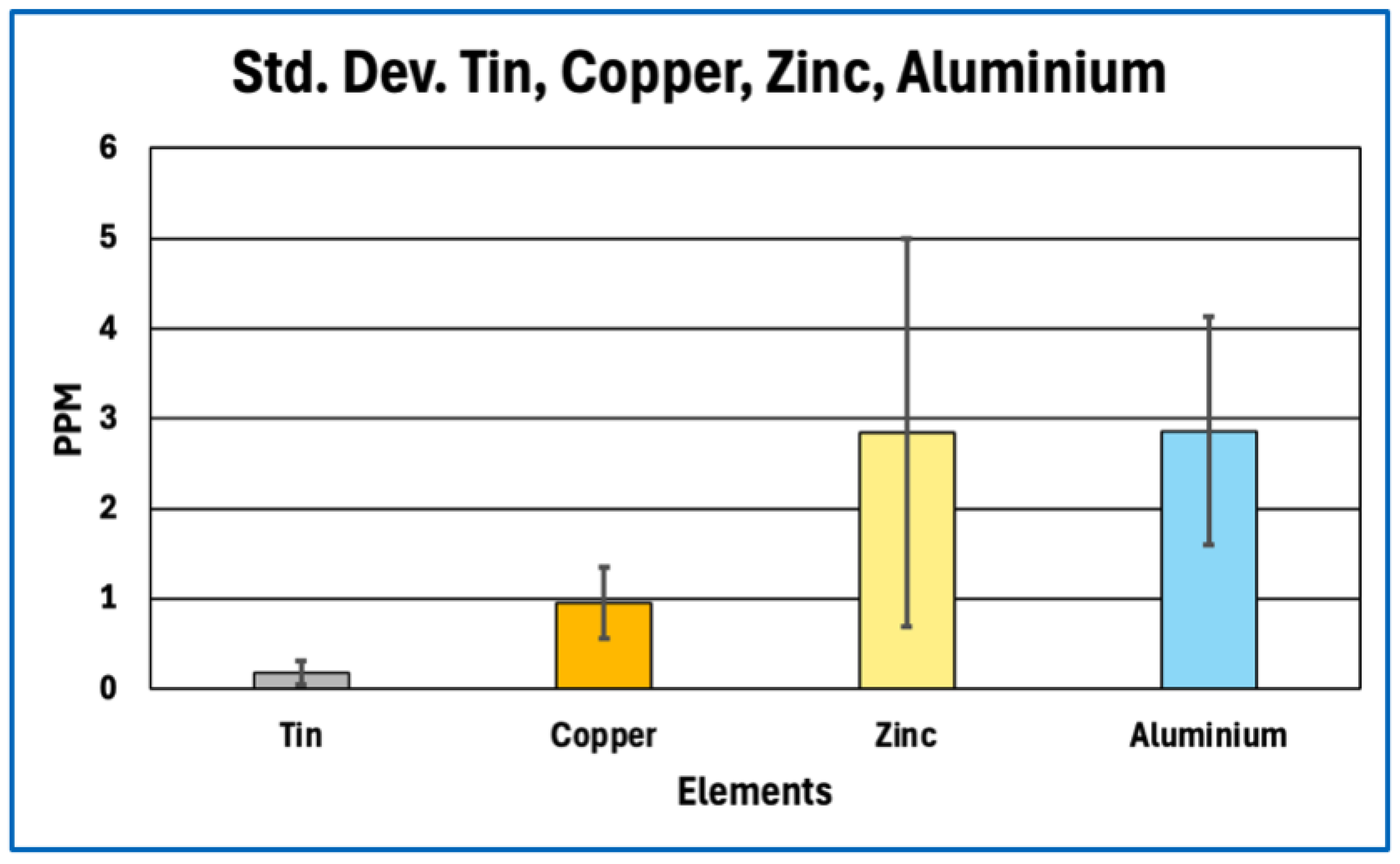

Figure 1,

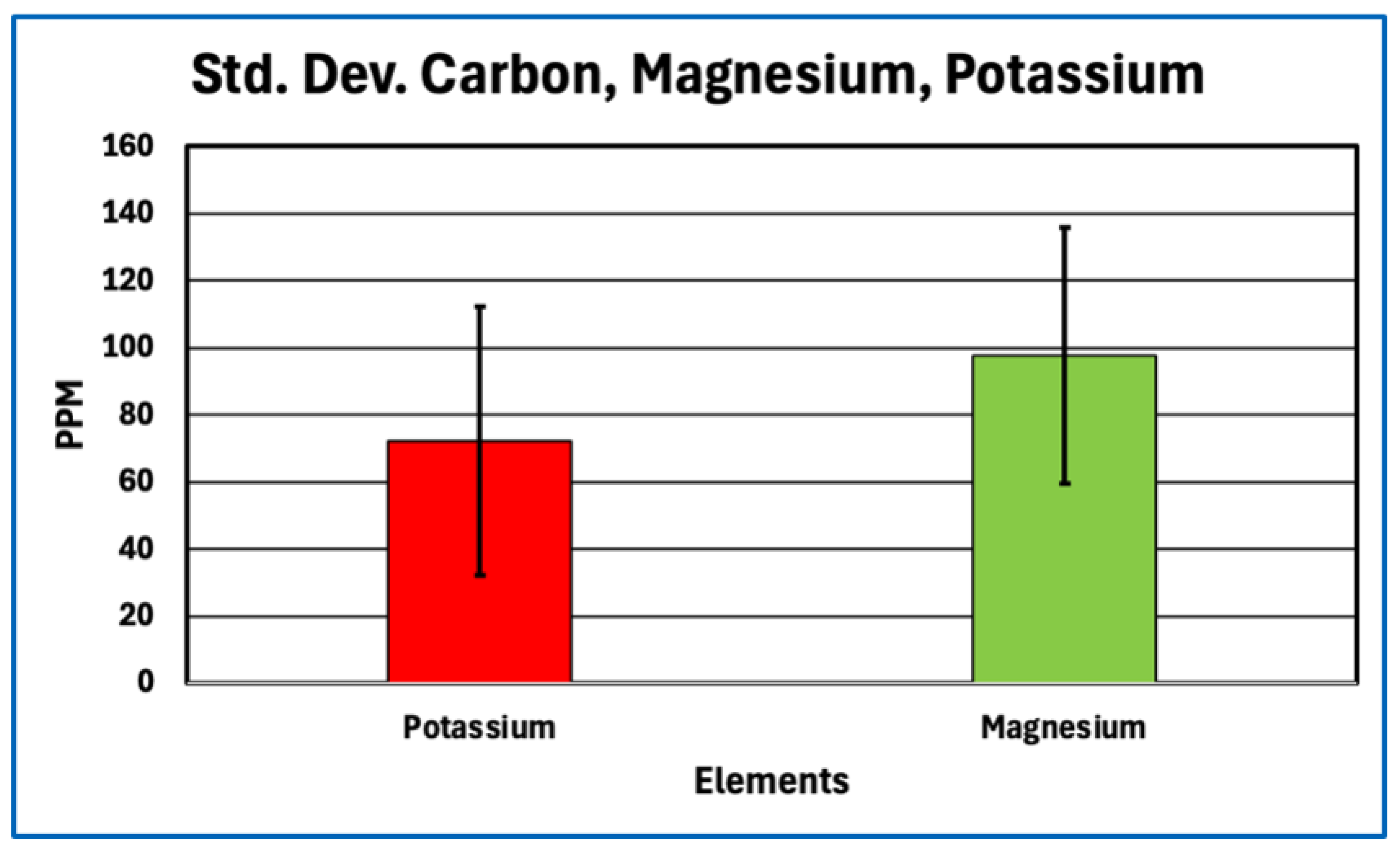

Figure 2,

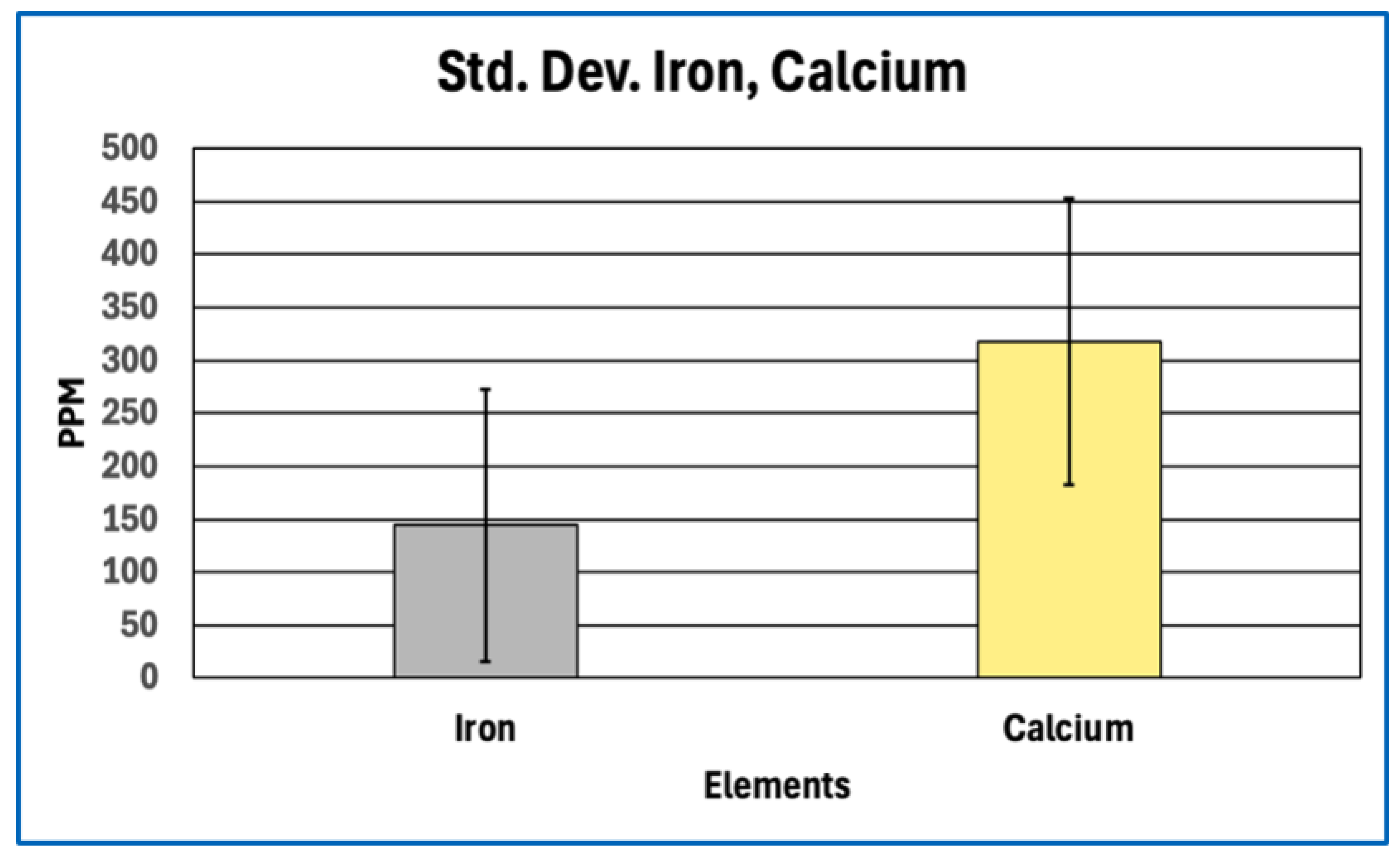

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, this consistency is evident visually in the parallel scaling of elemental concentrations between clot samples and whole-blood references. For each elemental grouping, AIC samples display coherent clustering rather than scattered or discontinuous profiles, with phosphorus and sodium repeatedly occupying the upper range of measured concentrations and sulfur consistently lower than would be expected for a fibrin-dominant protein matrix. Elements associated primarily with plasma electrolytes (e.g., sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium) track within physiologically plausible ranges relative to whole blood, whereas trace metals remain uniformly low and show no sample-specific enrichment. Importantly, no figure demonstrates abrupt inflection points, discrete sub-populations, or anomalous spikes that would indicate mixed material classes, exogenous contamination, or heterogeneous composite matrices.

Taken together, these results indicate that AICs share a reproducible global elemental profile consistent with a biological matrix, while simultaneously exhibiting systematic deviations from the elemental proportions expected for canonical fibrin-dominant thrombi. Detailed evaluation of these deviations is presented in the following section.

Deviations from Canonical Fibrin-Based Clots

Comparison of the elemental composition of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) with reference baselines revealed systematic and reproducible deviations from the elemental proportions expected for canonical fibrin-based thrombi. These deviations were most pronounced for sulfur and phosphorus, with additional imbalance evident in the carbon–nitrogen relationship when evaluated against theoretical fibrinogen stoichiometry.

Sulfur Depletion Relative to Expected Fibrin Content

Sulfur provides a robust bulk constraint on protein content because its abundance in clots is dominated by the cysteine and methionine residues of fibrinogen and related proteins. First-principles stoichiometric calculations based on the amino-acid composition of human fibrinogen indicate a sulfur content of approximately 0.8 % by mass (≈ 8,100 ppm) for a pure fibrin polymer. In contrast, the AICs analysed here exhibited a mean sulfur concentration of approximately 1,190 ppm.

Sulfur Depletion

When considered alongside sulfur depletion, the elevated phosphorus signal indicates enrichment of phosphate-bearing components disproportionate to protein content. Importantly, phosphorus enrichment was observed both in absolute concentration and relative to other bulk elements, reinforcing that this pattern reflects intrinsic composition rather than dilution or dehydration effects. No corresponding elevation in calcium sufficient to imply bulk apatite mineralization was observed, suggesting that phosphorus is present primarily in non-apatitic forms within the matrix.

Nitrogen–carbon Imbalance

Although carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen were not quantified by ICP-MS directly, their relative proportions can be inferred through comparison with stoichiometric expectations and complementary datasets. Protein-rich matrices are characterized by relatively high nitrogen content, typically accounting for ~16–18 % of dry mass in fibrinogen. In contrast, the depressed sulfur signal in AICs implies concomitant reduction in nitrogen-bearing peptide backbone material. When benchmarked against fibrinogen stoichiometry and normalized elemental models derived from platelet-rich fibrin matrices, the AICs exhibit a nitrogen deficit relative to carbon and oxygen, indicating dilution of protein content by oxygen-rich, nitrogen-poor constituents.

This nitrogen–carbon imbalance is directionally consistent with surface-weighted elemental spectra reported for fibrin matrices but is substantially more pronounced in the AICs, exceeding what can reasonably be attributed to analytical bias alone. Together with sulfur depletion, this pattern constrains the bulk composition of the AICs as protein-bearing but not protein-dominant.

Collectively, these elemental deviations—marked sulfur depletion, relative phosphorus enrichment, and nitrogen–carbon imbalance—demonstrate that anomalous intravascular casts are compositionally inconsistent with canonical fibrin-based thrombi, motivating further evaluation of their biochemical framework in the discussion.

Internal Heterogeneity

Assessment of internal heterogeneity within and between anomalous intravascular cast (AIC) samples revealed moderate variability in absolute elemental concentrations, consistent with biological materials subject to postmortem handling, dehydration, and partial loss of soluble components. Variance analyses showed that dispersion for most elements fell within expected ranges for heterogeneous biological tissues rather than indicating discrete compositional subtypes or bimodal distributions.

When evaluated across samples, the relative ordering of dominant elements—particularly phosphorus, sulfur, sodium, and calcium—was preserved despite differences in absolute concentration. Sulfur depletion and relative phosphorus enrichment, the defining compositional features identified in Section 4.2, were observed consistently across all analysed specimens and were not driven by a small number of outliers. This indicates that the principal elemental deviations reflect shared matrix characteristics rather than localized anomalies.

Within individual casts, no systematic regional variation in elemental composition could be resolved at the level of bulk subsampling employed in this study. Subsamples taken from different portions of the same cast did not exhibit reproducible proximal–distal or surface–core gradients beyond random variation attributable to sampling and preparation effects.

Correlation of elemental profiles with gross morphological or histological features described in Paper 1 revealed no consistent associations. Variations in cast length, degree of branching, elasticity, or histological lamination did not correspond to distinct elemental signatures. This lack of correlation suggests that the compositional deviations identified here represent a global property of the AIC matrix rather than secondary features tied to specific structural phenotypes.

Summary Elemental Phenotype

Taken together, the elemental analyses define a coherent and reproducible compositional signature for AICs. This signature is consistent across samples and laboratories and can be summarised as follows:

Elemental Signature of AICs

Sulfur: Markedly depleted relative to theoretical fibrinogen stoichiometry, constraining the bulk protein fraction to a minor component of total dry mass.

Phosphorus: Elevated in both absolute concentration and relative abundance compared with expectations for a purely proteinaceous fibrin matrix.

Nitrogen: Depressed relative to carbon and oxygen when benchmarked against fibrinogen stoichiometry, indicating dilution of peptide backbone material.

Oxygen: Proportionally elevated relative to nitrogen, consistent with enrichment of oxygen-rich, nitrogen-poor constituents.

Calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium: Present at levels compatible with entrained plasma electrolytes and postmortem redistribution rather than extensive mineralization.

Trace metals (e.g., Zn, Cu, Fe, Al, Sn): Detected at physiological or background levels without evidence of selective enrichment or foreign material incorporation.

This elemental phenotype contrasts sharply with that expected for canonical antemortem thrombi, which are dominated by fibrin and platelet-derived proteins and therefore exhibit higher sulfur and nitrogen content consistent with a protein-rich matrix. It also differs from ordinary postmortem clots, which typically reflect sedimented blood components and serum chemistry without systematic sulfur depletion or phosphorus enrichment.

Accordingly, the elemental profile of AICs is incompatible with classification as either conventional antemortem thrombi or routine postmortem coagula and instead defines a distinct, abnormal intravascular matrix.

Discussion

Interpretation of Elemental Anomalies

The elemental deviations identified in this study place strong constraints on the biochemical nature of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) without, by themselves, specifying molecular identity. In particular, the combination of sulfur depletion and relative phosphorus enrichment provides insight into bulk matrix composition that is independent of histological appearance and resistant to analytical artefact.

Implications of Sulfur Depletion for Protein Composition

Sulfur content offers a robust proxy for total protein fraction because sulfur-bearing amino acids—cysteine and methionine—are intrinsic to polypeptide backbones and occur at relatively fixed proportions in fibrinogen and related clotting proteins. First-principles stoichiometric calculations therefore define a narrow expected range for sulfur abundance in fibrin-dominant matrices. The marked sulfur depletion observed in AICs relative to this expectation implies that proteinaceous material constitutes only a minor fraction of total dry mass. Even allowing for surface effects, partial analytical under-recovery, or postmortem modification, the magnitude and consistency of sulfur depletion across samples exceed what can reasonably be attributed to methodological bias alone.

Importantly, this finding does not indicate absence of protein, nor does it contradict the fibrinous architecture observed histologically. Rather, it constrains the bulk composition of the casts, indicating that while proteins are present and contribute to structural features, they do not dominate the mass of the matrix. This distinction resolves the apparent tension between fibrin-like morphology and non-fibrin-like elemental composition and cautions against equating histological fibrin appearance with a predominantly proteinaceous material.

Interpretation of Phosphorus Enrichment Without Molecular Attribution

Phosphorus enrichment in AICs, observed both in absolute concentration and relative to other bulk elements, further distinguishes their composition from canonical fibrin-based thrombi. Phosphorus is not a major constituent of protein backbones and therefore serves as an indicator of phosphate-bearing components that are extrinsic to simple polypeptide matrices. The absence of commensurate calcium enrichment sufficient to indicate bulk apatite formation suggests that the detected phosphorus does not primarily reflect extensive mineralization.

At the same time, elemental analysis cannot resolve the specific chemical form of phosphorus present. The observed enrichment is therefore interpreted conservatively as evidence for incorporation or association of phosphate-bearing species within the matrix, rather than as proof of any particular molecular entity or bonding mechanism. This phosphorus signal, when considered alongside sulfur depletion and nitrogen–carbon imbalance, supports the inference that AICs comprise a hybrid matrix in which protein is structurally important but compositionally diluted by non-protein constituents.

Taken together, sulfur depletion and phosphorus enrichment define a compositional profile that is incompatible with a simple fibrin-dominant clot yet remains consistent with a biologically derived intravascular material. These elemental constraints establish the need for molecular-level analysis to determine the identities and relative abundances of the protein and non-protein components involved, which is addressed in the subsequent proteomic study.

Integration with Morphological–Histological Findings

The elemental findings reported here reinforce and extend the morphological and histological conclusions established in the first paper of this trilogy. In Paper 1, anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) were shown to form elongated, lumen-conforming structures with elastic mechanical properties and fibrinous lamination indicative of formation under active blood flow, yet with sparse cellular inclusion atypical of conventional thrombi. Those observations established a distinctive structural phenotype but could not resolve the biochemical nature of the matrix giving rise to that architecture.

Elemental analysis provides an independent and orthogonal line of evidence that complements these structural findings. The systematic depletion of sulfur and relative enrichment of phosphorus demonstrate that the material comprising AICs is compositionally inconsistent with a simple fibrin-dominant clot, despite exhibiting fibrin-like morphology under histological examination. This decoupling of appearance from bulk composition explains how AICs can display organized fibrillar architecture while failing to conform chemically to canonical thrombi, and it resolves potential ambiguity arising from histological resemblance alone.

Taken together, the convergence of a reproducible structural phenotype (morphology and histology) and a reproducible elemental phenotype (bulk composition) provides a stronger basis for defining AICs as a distinct intravascular entity than either line of evidence could alone. Morphological and histological data establish that the structures are real, coherent, and formed in vivo, while elemental data constrain what they are made of and rule out classification as ordinary antemortem thrombi or routine postmortem clots. This multi-modal consistency reduces the likelihood that the observed features arise from artefact, sampling bias, or isolated pathological variation.

Accordingly, the integration of structural and elemental evidence supports the interpretation that AICs represent a materially and biologically distinct class of intravascular cast. Defining the molecular constituents responsible for this combined phenotype requires resolution beyond elemental composition alone, providing a clear rationale for the proteomic analyses presented in the final paper of this series.

What Elemental Analysis Rules Out

The elemental composition of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) allows several common alternative explanations for their origin to be excluded with confidence. These exclusions arise not from interpretation of structure or appearance, but from bulk chemical constraints that are incompatible with specific proposed mechanisms.

Exclusion of Simple Fibrin Overload

A straightforward explanation for unusual intravascular material might be excessive fibrin deposition or hyper-coagulability leading to unusually large or dense clots. However, simple fibrin overload would necessarily produce a matrix enriched in protein and therefore elevated in sulfur and nitrogen relative to bulk mass. The marked sulfur depletion observed in AICs is incompatible with this scenario, as it constrains the total fibrin-like protein fraction to a minor component of the material. Even accounting for analytical and postmortem effects, the sulfur deficit is too large and too consistent to be reconciled with a clot composed predominantly of fibrin. Elemental analysis therefore rules out simple quantitative excess of an otherwise normal fibrin matrix as an explanation for AIC composition.

Exclusion of Cellular Aggregation

Aggregation or compaction of blood cells, platelets, or cellular debris could also produce coherent intravascular material without invoking novel chemistry. Such aggregates would be expected to retain elemental signatures characteristic of cellular biomass, including relatively high nitrogen and sulfur content from intracellular proteins, nucleoproteins, and membrane-associated enzymes, together with iron enrichment from hemoglobin where erythrocytes are involved. The elemental profiles of AICs do not display these features. Nitrogen and sulfur are depressed relative to protein expectations, and iron levels vary in a manner consistent with minor entrainment rather than bulk cellular composition. These findings are inconsistent with AICs being formed primarily by cellular aggregation or sedimentation.

Exclusion of Classical Coagulation Artifacts

Finally, classical coagulation artifacts arising from postmortem changes, fixation, dehydration, or handling would be expected to preserve the underlying elemental proportions of blood-derived proteins and cells, even if morphology were distorted. While such processes can redistribute soluble ions or modify surface chemistry, they do not selectively deplete sulfur-bearing amino acids or systematically enrich phosphorus relative to protein content. The reproducible elemental deviations observed in AICs across samples and laboratories therefore cannot be explained as artefacts of coagulation, fixation, or postmortem handling alone.

Collectively, these exclusions narrow the plausible interpretation of AICs to that of a biologically derived but compositionally abnormal intravascular matrix. Elemental analysis thus not only constrains what AICs are made of, but also rules out several conventional explanations that might otherwise account for their unusual appearance.

Limits of Elemental Inference

While elemental analysis provides strong constraints on bulk composition, it has intrinsic limitations that must be acknowledged. Elemental data describe the relative abundance of atoms within a material but do not specify how those atoms are organized into molecules, polymers, or complexes. As such, elemental analysis alone cannot resolve the identity, sequence, or relative abundance of specific proteins present within AICs, nor can it distinguish among protein isoforms or post-translationally modified variants.

In addition, elemental measurements do not define bonding states or molecular architecture. The presence of phosphorus, for example, cannot discriminate between inorganic phosphate, polyphosphate, phospholipids, nucleic acids, or other phosphate-bearing species, nor can sulfur measurements specify whether sulfur atoms reside in reduced thiols, disulfide bonds, or oxidised forms. Likewise, elemental ratios cannot determine whether non-protein constituents are covalently integrated into the matrix, weakly associated, or present as physically entrained phases.

Accordingly, elemental analysis should be understood as a constraint-setting tool rather than a molecular identification method. In the present study, elemental data establish that AICs are compositionally incompatible with canonical fibrin-dominant thrombi and require substantial non-protein contributions, but they do not identify the specific molecular constituents responsible for this abnormal matrix. Resolution of protein identity, relative abundance, and molecular interactions therefore requires complementary analytical approaches capable of operating at the molecular level.

These limitations define the scope boundary between elemental and proteomic analyses and provide the rationale for the molecular characterization presented in the final paper of this trilogy.

Rationale for Proteomic Analysis (Paper 3)

The elemental anomalies identified in this study define clear compositional constraints but simultaneously expose the limits of inference achievable without molecular resolution. Sulfur depletion constrains the bulk protein fraction, phosphorus enrichment indicates incorporation of phosphate-bearing components, and nitrogen–carbon imbalance confirms dilution of peptide backbone material; however, none of these elemental signatures can identify which proteins are present, which are absent, or how protein constituents are distributed within the anomalous intravascular cast (AIC) matrix. As a result, elemental analysis establishes that the matrix is abnormal but cannot determine what molecular species give rise to this composition.

Protein-level resolution is therefore required to reconcile the coexistence of fibrin-like morphology with a non-fibrin-dominant elemental profile. Proteomic analysis can determine whether fibrin chains are present in expected proportions, selectively depleted, modified, or accompanied by atypical proteins not characteristic of ordinary thrombi. It can also reveal whether the protein component of AICs represents a minor structural scaffold embedded within a broader non-protein matrix, as implied by sulfur-based mass constraints, or whether alternative protein assemblies contribute to the observed architecture.

Accordingly, the elemental findings presented here define the precise analytical gap that proteomics is uniquely positioned to fill. By identifying the protein constituents and their relative abundances, proteomic analysis provides the necessary molecular context to interpret the compositional anomalies revealed at the elemental level. This molecular characterization is addressed in the third and final paper of this trilogy, which builds directly on the structural and compositional constraints established in Papers 1 and 2.

Before molecular resolution is addressed directly, it is therefore useful to consider, in hypothesis-driven terms, the principal phosphate-bearing reservoirs that could plausibly account for the phosphorus enrichment constrained by elemental analysis.

Potential Sources of Phosphorus Enrichment in Anomalous Intravascular Casts

The consistent enrichment of phosphorus observed alongside marked sulfur depletion prompts consideration of potential non-fibrin sources of phosphate that could contribute to the elemental phenotype of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs).

Elemental analysis demonstrates that anomalous intravascular casts exhibit reproducible phosphorus enrichment concurrent with marked sulfur depletion relative to theoretical fibrinogen stoichiometry. Because sulfur provides a robust bulk proxy for protein content, this elemental imbalance constrains the clot matrix as protein-bearing but not protein-dominant. The excess phosphorus must therefore arise from non-fibrin phosphate reservoirs or from protein-associated phosphate contributions disproportionate to sulfur-containing amino acids. Several plausible sources merit consideration.

One potential contributor is membrane-derived phospholipid reservoirs associated with cellular disruption. Histological examination of AICs reveals extensive eosinophilic cytoplasmic material consistent with widespread erythrocyte lysis and fragmentation (Paper 1). While hemoglobin itself is not phosphorus-rich, erythrocyte and platelet membranes contain abundant phospholipids, each bearing phosphate head-groups. Fragmentation or persistence of membrane-derived material within the clot matrix could therefore elevate bulk phosphorus without restoring sulfur to levels expected for a fibrin-dominant protein scaffold. Such a mechanism would be consistent with phosphorus enrichment accompanied by depressed sulfur and nitrogen signals.

A second, non-mutually exclusive contributor is inorganic or polymeric phosphate incorporated during clot formation. Platelet activation releases inorganic polyphosphate from platelet dense granules, and this platelet-derived polyphosphate has been shown to associate with fibrin networks and modulate clot architecture by increasing fibrin fiber thickness and resistance to fibrinolysis (Smith & Morrissey, 2008; Mutch et al., 2010; Undas & Ariëns, 2011; Longstaff, 2015). Incorporation of polyphosphate-bearing reservoirs would elevate phosphorus content while contributing little sulfur or nitrogen, thereby shifting elemental ratios away from fibrinogen stoichiometry without requiring mineralization. The absence of calcium levels sufficient to indicate apatite formation supports the interpretation that phosphorus is present predominantly in non-mineralised forms.

While nucleic acids represent another class of potential phosphate-bearing reservoirs, their contribution is unlikely to dominate bulk phosphorus given the absence of corresponding nitrogen enrichment and the lack of histological features suggestive of nucleic acid–rich debris.

Additional phosphorus may also derive from phosphorylated proteins and other phosphate-bearing biomolecules present at low abundance. Proteomic analysis (Paper 3) indicates that AICs comprise a heterogeneous protein population, including fibrin family proteins, heme-associated proteins, and numerous additional constituents. Post-translational phosphorylation of proteins can contribute measurable phosphorus, and large-scale phosphoproteomic studies have demonstrated extensive phosphorylation of both host and viral proteins during SARS-CoV-2 infection (Bouhaddou et al., 2020). However, given the relatively small mass contribution of phosphosites—typically occurring on serine (Ser), threonine (Thr), and tyrosine (Tyr) residues via their hydroxyl groups—such modifications alone are unlikely to account for the magnitude of phosphorus enrichment observed, unless accompanied by substantial quantities of phosphate-bearing, non-protein material.

Finally, interaction between clot-associated proteins and specific ligands may further influence elemental balance and clot architecture. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein has been shown experimentally to bind fibrinogen and fibrin, inducing structural alterations and increased resistance to fibrinolysis in vitro (Grobbelaar et al., 2021). Additional studies have reported co-localization of spike protein with fibrin in experimental and pathological contexts, suggesting that spike–fibrin interactions may occur in vivo (Ryu et al., 2024). Detection of spike protein within retrieved thrombi from COVID-19 patients further supports the possibility that circulating spike fragments can associate with clot material (Pretorius et al., 2022). While spike protein itself is not a biochemical “phosphorus donor” in the enzymatic sense, it can carry phosphate groups via post-translational phosphorylation, raising the possibility that spike–fibrin interactions could contribute modestly to phosphate burden or alter clot composition indirectly. The quantitative contribution of such mechanisms to bulk elemental phosphorus, however, remains unresolved.

Taken together, these considerations suggest that phosphorus enrichment in AICs most plausibly reflects a composite contribution from membrane-derived phospholipid reservoirs, polyphosphate-bearing reservoirs, and other phosphate ester–rich reservoirs within a heterogeneous protein population rather than from fibrin alone.

Elemental analysis constrains the problem by excluding a purely proteinaceous or mineralised matrix, but it cannot resolve phosphate speciation or molecular origin. Targeted biochemical, lipidomic, and phosphate-speciation analyses will be required to discriminate among these candidate reservoirs and to determine their relative contributions to the anomalous elemental phenotype described here.