Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

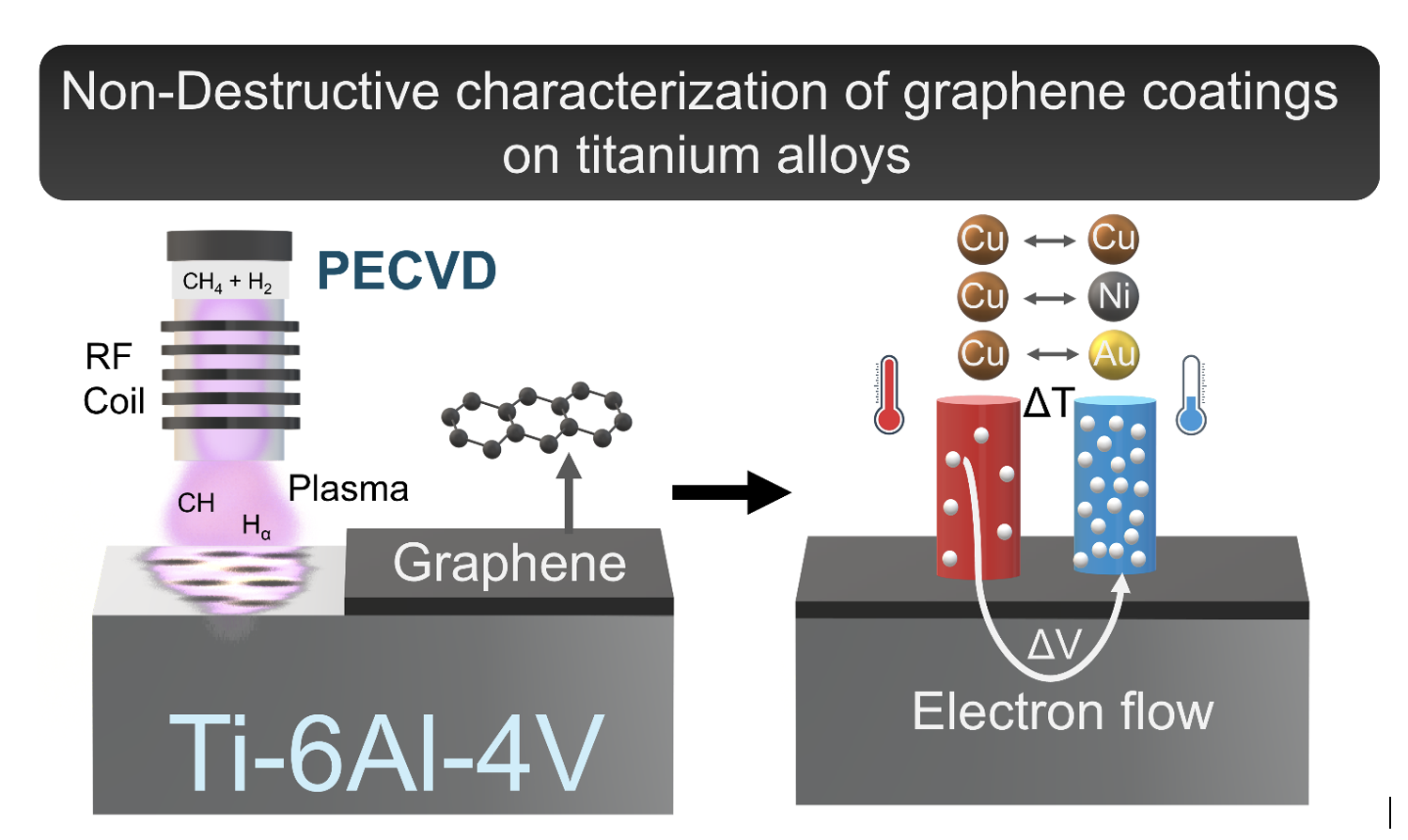

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. CVD & PECVD Preliminary Tests & Deposition on Ti-6Al-4V ELI Grade Samples

2.3. Raman Characterization of Preliminary Ti Samples

2.4. TEP Characterization of Ti-6Al-4V ELI Grade Samples

2.5. Conductivity Measurements Using Eddy Currents Testing (ECT)

2.6. Surface Roughness Measurements

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Tests of PECVD on Ti-Substrate

3.2. Growth Time Influence in Optimal PECVD Parameters

3.3. Thermoelectric Power (TEP) Characterization of Nanographene-Coated Ti-6Al-4V ELI Grade Samples

3.4. Eddy Currents Characterization

3.5. Surface Roughness Measurements

3.6. SEM Characterization

4. Discussion

4.1. Plasma-Enhanced Nanographene Growth from Methane on Substrates

4.2. Proposed Nanographene Pathway Growth

4.3. Thermoelectric Power (TEP) Characterization of Nanographene-Coated Ti-6Al-4V ELI Grade Samples

4.4. Eddy Currents Testing (ECT) Conductivity Measurements of Nanographene-Coated Ti-6Al-4V ELI Grade Samples

4.5. Surface Roughness Measurements

4.6. SEM Characterization

4.7. Functional and Statistical Basis for Potential Applications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| PECVD | Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| NG | Nanographene |

| TEP | Thermoelectric Power |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| LT | Low Thickness (1.6 mm samples) |

| MT | Medium Thickness (3.2 mm samples) |

| HT | High Thickness (7 mm samples) |

| LR | Low Roughness (samples mirror polished) |

| MR | Medium Roughness (samples prepared with 600 microns sandpaper) |

| HR | High Roughness (samples prepared with 240 microns sandpaper) |

References

- Gil, F.; Planell, J. Aplicaciones biomédicas del titanio. Biomecànica, art 2009, 4.

- Leyens, C.; Peters, M. Titanium and titanium alloys: fundamentals and applications; Wiley Online Library: 2006.

- Venkatesh, B.; Chen, D.; Bhole, S. Effect of heat treatment on mechanical properties of Ti–6Al–4V ELI alloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2009, 506, 117-124.

- Galarraga, H.; Warren, R.J.; Lados, D.A.; Dehoff, R.R.; Kirka, M.M.; Nandwana, P. Effects of heat treatments on microstructure and properties of Ti-6Al-4V ELI alloy fabricated by electron beam melting (EBM). Materials Science and Engineering: A 2017, 685, 417-428.

- Committee, A.H. Properties and selection: nonferrous alloys and special-purpose materials; ASM international: 1990.

- Popa, M.V.; Moreno, J.M.C.; Popa, M.; Vasilescu, E.; Drob, P.; Vasilescu, C.; Drob, S.I. Electrochemical deposition of bioactive coatings on Ti and Ti–6Al–4V surfaces. Surface and Coatings Technology 2011, 205, 4776-4783.

- Bhui, A.S.; Singh, G.; Sidhu, S.S.; Bains, P.S. Experimental investigation of optimal ED machining parameters for Ti-6Al-4V biomaterial. Facta Universitatis, Series: Mechanical Engineering 2018, 16, 337-345.

- GRUYTER, D. Investigation on surface properties of laser-textured Ti-6Al-4V ELI biomaterial.

- Boddula, R.; Ahamed, M.I.; Asiri, A.M. Polymers Coatings: Technology and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: 2020.

- Grigoriev, S.; Sotova, C.; Vereschaka, A.; Uglov, V.; Cherenda, N. Modifying coatings for medical implants made of titanium alloys. Metals 2023, 13, 718.

- Manivasagam, G.; Dhinasekaran, D.; Rajamanickam, A. Biomedical implants: corrosion and its prevention-a review. Recent patents on corrosion science 2010.

- Creighton, J.; Ho, P. Introduction to chemical vapor deposition (CVD). ASM International 2001, 407.

- Hamedani, Y.; Macha, P.; Bunning, T.J.; Naik, R.R.; Vasudev, M.C. Plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition: where we are and the outlook for the future. In Chemical Vapor Deposition-Recent Advances and Applications in Optical, Solar Cells and Solid State Devices; IntechOpen: 2016.

- Neralla, S. Chemical vapor deposition: recent advances and applications in optical, solar cells and solid state devices. 2016.

- Kang, S.; Mauchauffé, R.; You, Y.S.; Moon, S.Y. Insights into the role of plasma in atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition of titanium dioxide thin films. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 16684.

- Meyyappan, M.; Delzeit, L.; Cassell, A.; Hash, D. Carbon nanotube growth by PECVD: a review. Plasma sources science and technology 2003, 12, 205.

- Bogaerts, A.; Tu, X.; Whitehead, J.C.; Centi, G.; Lefferts, L.; Guaitella, O.; Azzolina-Jury, F.; Kim, H.-H.; Murphy, A.B.; Schneider, W.F. The 2020 plasma catalysis roadmap. Journal of physics D: applied physics 2020, 53, 443001.

- Martinu, L.; Zabeida, O.; Klemberg-Sapieha, J. Plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition of functional coatings. Handbook of deposition technologies for films and coatings 2010, 392-465.

- Nag, A.; Simorangkir, R.B.; Gawade, D.R.; Nuthalapati, S.; Buckley, J.L.; O’Flynn, B.; Altinsoy, M.E.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. Graphene-based wearable temperature sensors: A review. Materials & Design 2022, 221, 110971.

- Yang, J.; Wei, D.; Tang, L.; Song, X.; Luo, W.; Chu, J.; Gao, T.; Shi, H.; Du, C. Wearable temperature sensor based on graphene nanowalls. Rsc Advances 2015, 5, 25609-25615.

- Chien, C.T.; Hiralal, P.; Wang, D.Y.; Huang, I.S.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, C.W.; Amaratunga, G.A.J. Graphene-Based Integrated Photovoltaic Energy Harvesting/Storage Device. Small 2015, 11, 2929-2937. [CrossRef]

- Grande, L.; Chundi, V.T.; Wei, D.; Bower, C.; Andrew, P.; Ryhänen, T. Graphene for energy harvesting/storage devices and printed electronics. Particuology 2012, 10, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chatterjee, K. Comprehensive Review on the Use of Graphene-Based Substrates for Regenerative Medicine and Biomedical Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 26431-26457. [CrossRef]

- Ponmozhi, J.; Frias, C.; Marques, T.; Frazão, O. Smart sensors/actuators for biomedical applications: Review. Measurement 2012, 45, 1675-1688. [CrossRef]

- Reina, G.; González-Domínguez, J.M.; Criado, A.; Vázquez, E.; Bianco, A.; Prato, M. Promises, facts and challenges for graphene in biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4400-4416. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, L.; Shi, G. Graphene-based smart materials. Nat Rev Mater 2017, 2, 17046. [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, M.F.; Shao, Y.; Kaner, R.B. Graphene for batteries, supercapacitors and beyond. Nat Rev Mater 2016, 1, 16033. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, K.-Y.; Hong, J.; Kang, K. All-graphene-battery: bridging the gap between supercapacitors and lithium ion batteries. Scientific Reports 2014, 4, 5278. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Zhang, C.; Yin, H.; Hou, Y. Graphene-based nanocomposites for energy storage and conversion in lithium batteries, supercapacitors and fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 15-32. [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Bi, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Li, Z. A comprehensive review on graphene-based anti-corrosive coatings. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 373, 104-121. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.M.C.A.; Aguiar, C.; Vazquez, A.M.; Robin, A.; Barboza, M.J.R. Improving corrosion resistance of Ti–6Al–4V alloy through plasma-assisted PVD deposited nitride coatings. Corrosion Science 2014, 88, 317-327. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-S.; Liao, L.-K.; Hsu, C.-H.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Wu, W.-Y.; Liao, S.-C.; Chen, K.-H.; Lui, P.-W.; Zhang, S.; Lien, S.-Y. Reprint of “Effect of substrate bias on biocompatibility of amorphous carbon coatings deposited on Ti6Al4V by PECVD”. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 376, 124787. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Gorman, J.J.; Na, S.R.; Cullinan, M. Growth of monolayer graphene on nanoscale copper-nickel alloy thin films. Carbon 2017, 115, 441-448. [CrossRef]

- Jankauskas, Š.; Meškinis, Š.; Žurauskienė, N.; Guobienė, A. Influence of Synthesis Parameters on Structure and Characteristics of the Graphene Grown Using PECVD on Sapphire Substrate. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1635. [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Zhou, H.; Liu, D.; Luo, F.; Tian, Y.; Chen, D.; Wei, W. One-step in-situ reaction synthesis of TiC/graphene composite thin film for titanium foil surface reinforcement. Vacuum 2019, 160, 472-477. [CrossRef]

- Nine, M.J.; Cole, M.A.; Tran, D.N.H.; Losic, D. Graphene: a multipurpose material for protective coatings. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3, 12580-12602. [CrossRef]

- Usha Kiran, N.; Dey, S.; Singh, B.; Besra, L. Graphene Coating on Copper by Electrophoretic Deposition for Corrosion Prevention. Coatings 2017, 7, 214. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Z. Graphene Coated Ti-6Al-4V Exhibits Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties Against Oral Pathogens. Journal of Prosthodontics 2023, 32, 505-511. [CrossRef]

- Romo-Rico, J.; Bright, R.; Krishna, S.M.; Vasilev, K.; Golledge, J.; Jacob, M.V. Antimicrobial graphene-based coatings for biomedical implant applications. Carbon Trends 2023, 12, 100282. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Han, Y.M.; Morin, J.L.P.; Luong-Van, E.K.; Chew, R.J.J.; Castro Neto, A.H.; Nijhuis, C.A.; Rosa, V. Inhibiting Corrosion of Biomedical-Grade Ti-6Al-4V Alloys with Graphene Nanocoating. J Dent Res 2020, 99, 285-292. [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, J.R. Introductory Raman Spectroscopy, 2nd ed ed.; Elsevier Science & Technology: San Diego, 2003; p. 1.

- Smith, E.; Dent, G. Modern raman spectroscopy: a practical approach, Reprinted ed.; Wiley: Chichester, 2008; p. 210.

- Ferrari, A.C.; Basko, D.M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nature Nanotech 2013, 8, 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, A.; Felten, A.; Mishchenko, A.; Britnell, L.; Krupke, R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Casiraghi, C. Probing the Nature of Defects in Graphene by Raman Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3925-3930. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmid, H.J. Introduction to thermoelectricity, Second edition ed.; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 2016; p. 278.

- Perez, M.; Massardier, V.; Kleber, X. Thermoelectric power applied to metallurgy: principle and recent applications. International Journal of Materials Research 2009, 100, 1461-1465. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.D.; Lasseigne-Jackson, A.N.; Jackson, J.E.; Mishra, B.; Olson, D.L.; Koenig, T. Characterization of Weldments and Materials Using Thermoelectric Power Measurements. MSF 2008, 580-582, 117-120. [CrossRef]

- Carreon, H. Thermoelectric detection of fretting damage in aerospace materials. Russ J Nondestruct Test 2014, 50, 684-692. [CrossRef]

- Carreon, H.; San Martin, D.; Caballero, F.G.; Panin, V.E. The effect of thermal aging on the strength and the thermoelectric power of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Phys Mesomech 2017, 20, 447-456. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, P. Opportunities and challenges for nondestructive residual stress assessment. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, 2006; pp. 22-40.

- Yong-Moo, C.; Sabir, C.M.; Paul, E.; Paul, G.; John, R.; Asghar, K.A. Eddy Current Testing at Level 2: manual for the Syllabi Contained in IAEA-TECDOC-628. Rev. 2” Training Guidelines for Non Destructive Testing Techniques. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency 2011.

- Rosen, M.; Horowitz, E.; Swartzendruber, L.; Fick, S.; Mehrabian, R. The aging process in aluminum alloy 2024 studied by means of eddy currents. Materials Science and Engineering 1982, 53, 191-198.

- Safdar, A.; He, H.; Wei, L.Y.; Snis, A.; Chavez de Paz, L.E. Effect of process parameters settings and thickness on surface roughness of EBM produced Ti-6Al-4V. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2012, 18, 401-408.

- Zhai, C.; Gan, Y.; Hanaor, D.; Proust, G.; Retraint, D. The role of surface structure in normal contact stiffness. Experimental Mechanics 2016, 56, 359-368.

- Deligianni, D.D.; Katsala, N.; Ladas, S.; Sotiropoulou, D.; Amedee, J.; Missirlis, Y. Effect of surface roughness of the titanium alloy Ti–6Al–4V on human bone marrow cell response and on protein adsorption. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1241-1251.

- Shah, J.; Lopez-Mercado, J.; Carreon, M.G.; Lopez-Miranda, A.; Carreon, M.L. Plasma synthesis of graphene from mango peel. ACS omega 2018, 3, 455-463.

- Ferrari, A.C.; Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Physical review B 2000, 61, 14095.

- Brown, S.D.M.; Jorio, A.; Corio, a.P.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Dresselhaus, G.; Saito, R.; Kneipp, K. Origin of the Breit-Wigner-Fano lineshape of the tangential G-band feature of metallic carbon nanotubes. Physical Review B 2001, 63, 155414.

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Physical review letters 2006, 97, 187401.

- Xu, M.; Liang, T.; Shi, M.; Chen, H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chemical reviews 2013, 113, 3766-3798.

- Gupta, A.; Chen, G.; Joshi, P.; Tadigadapa, S.; Eklund. Raman scattering from high-frequency phonons in supported n-graphene layer films. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2667-2673.

- Wu, J.-B.; Lin, M.-L.; Cong, X.; Liu, H.-N.; Tan, P.-H. Raman spectroscopy of graphene-based materials and its applications in related devices. Chemical Society Reviews 2018, 47, 1822-1873.

- Venezuela, P.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F. Theory of double-resonant Raman spectra in graphene: Intensity and line shape of defect-induced and two-phonon bands. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2011, 84, 035433.

- Malard, L.M.; Pimenta, M.A.; Dresselhaus, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Raman spectroscopy in graphene. Physics reports 2009, 473, 51-87.

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Jorio, A.; Saito, R. Characterizing graphene, graphite, and carbon nanotubes by Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010, 1, 89-108.

- Mikhailov, S. Measuring disorder in graphene with Raman spectroscopy. Physics and Applications of Graphene—Experiments; InTech Publishers: London, UK 2011, 439-454.

- Yang, W.; He, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, M.; Xie, G.; Wang, D.; Yang, R.; Shi, D. Growth, characterization, and properties of nanographene. Small 2012, 8, 1429-1435.

- Zandiatashbar, A.; Lee, G.-H.; An, S.J.; Lee, S.; Mathew, N.; Terrones, M.; Hayashi, T.; Picu, C.R.; Hone, J.; Koratkar, N. Effect of defects on the intrinsic strength and stiffness of graphene. Nature communications 2014, 5, 3186.

- Kumal, R.R.; Gharpure, A.; Viswanathan, V.; Mantri, A.; Skoptsov, G.; Vander Wal, R. Microwave plasma formation of nanographene and graphitic carbon black. C 2020, 6, 70.

- Kalita, G.; Kayastha, M.S.; Uchida, H.; Wakita, K.; Umeno, M. Direct growth of nanographene films by surface wave plasma chemical vapor deposition and their application in photovoltaic devices. RSC advances 2012, 2, 3225-3230.

- Madito, M.J. Revisiting the Raman disorder band in graphene-based materials: A critical review. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2025, 103814.

- Qi, J.L.; Wang, X.; Lin, J.H.; Zhang, F.; Feng, J.C.; Fei, W.-D. A high-performance supercapacitor of vertically-oriented few-layered graphene with high-density defects. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 3675-3682.

- Robertson, J. Diamond-like amorphous carbon. Materials science and engineering: R: Reports 2002, 37, 129-281.

- Li, N.; Zhen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; He, L. Nucleation and growth dynamics of graphene grown by radio frequency plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 6007.

- Biddle, C.C. Theory of eddy currents for nondestructive testing. 1976.

- Yan, C.; Bao, J.; Zheng, X. Conductivity Measurement for Non-Magnetic Materials Using Eddy Current Method with a Novel Simplified Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 3900.

- Nizam, M.; Sebastian, D.; Kairi, M.; Khavarian, M.; Mohamed, A. Synthesis of graphene flakes over recovered copper etched in ammonium persulfate solution. Sains Malays 2017, 46, 1039-1045.

- Stöberl, U.; Wurstbauer, U.; Wegscheider, W.; Weiss, D.; Eroms, J. Morphology and flexibility of graphene and few-layer graphene on various substrates. Applied Physics Letters 2008, 93.

- Chugh, S.; Mehta, R.; Lu, N.; Dios, F.D.; Kim, M.J.; Chen, Z. Comparison of graphene growth on arbitrary non-catalytic substrates using low-temperature PECVD. Carbon 2015, 93, 393-399.

- Wei, D.; Peng, L.; Li, M.; Mao, H.; Niu, T.; Han, C.; Chen, W.; Wee, A.T.S. Low temperature critical growth of high quality nitrogen doped graphene on dielectrics by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. ACS nano 2015, 9, 164-171.

- Yang, C.; Bi, H.; Wan, D.; Huang, F.; Xie, X.; Jiang, M. Direct PECVD growth of vertically erected graphene walls on dielectric substrates as excellent multifunctional electrodes. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2013, 1, 770-775.

- Riikonen, S.; Krasheninnikov, A.; Halonen, L.; Nieminen, R. The role of stable and mobile carbon adspecies in copper-promoted graphene growth. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2012, 116, 5802-5809.

- Wang, X.; Yuan, Q.; Li, J.; Ding, F. The transition metal surface dependent methane decomposition in graphene chemical vapor deposition growth. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 11584-11589.

- Li, X.; Colombo, L.; Ruoff, R.S. Synthesis of graphene films on copper foils by chemical vapor deposition. Advanced Materials 2016, 28, 6247-6252.

- Losurdo, M.; Giangregorio, M.M.; Capezzuto, P.; Bruno, G. Graphene CVD growth on copper and nickel: role of hydrogen in kinetics and structure. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2011, 13, 20836-20843.

- Terasawa, T.-o.; Saiki, K. Growth of graphene on Cu by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Carbon 2012, 50, 869-874.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Xin, J.; Yakobson, B.I.; Ding, F. Role of hydrogen in graphene chemical vapor deposition growth on a copper surface. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 3040-3047.

- López, G.; Mittemeijer, E. The solubility of C in solid Cu. Scripta Materialia 2004, 51, 1-5.

- Szkliniarz, A.; Szkliniarz, W. Carbon in commercially pure titanium. Materials 2023, 16, 711.

- Kim, H.; Mattevi, C.; Calvo, M.R.; Oberg, J.C.; Artiglia, L.; Agnoli, S.; Hirjibehedin, C.F.; Chhowalla, M.; Saiz, E. Activation energy paths for graphene nucleation and growth on Cu. ACS nano 2012, 6, 3614-3623.

- Zhang, W.; Wu, P.; Li, Z.; Yang, J. First-principles thermodynamics of graphene growth on Cu surfaces. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2011, 115, 17782-17787.

- Despiau-Pujo, E.; Davydova, A.; Cunge, G.; Delfour, L.; Magaud, L.; Graves, D. Elementary processes of H2 plasma-graphene interaction: A combined molecular dynamics and density functional theory study. Journal of Applied Physics 2013, 113.

- Xie, L.; Jiao, L.; Dai, H. Selective etching of graphene edges by hydrogen plasma. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132, 14751-14753.

- Nunomura, S. A review of plasma-induced defects: detection, kinetics and advanced management. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2023, 56, 363002.

- Nunomura, S.; Tsutsumi, T.; Takada, N.; Fukasawa, M.; Hori, M. Radical, ion, and photon’s effects on defect generation at SiO2/Si interface during plasma etching. Applied Surface Science 2024, 672, 160764.

- Thiemann, F.L.; Rowe, P.; Zen, A.; Muller, E.A.; Michaelides, A. Defect-dependent corrugation in graphene. Nano Letters 2021, 21, 8143-8150.

- Ma, J.; Alfè, D.; Michaelides, A.; Wang, E. Stone-Wales defects in graphene and other planar sp 2-bonded materials. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2009, 80, 033407.

- Kim, Y.; Ihm, J.; Yoon, E.; Lee, G.-D. Dynamics and stability of divacancy defects in graphene. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2011, 84, 075445.

- Banhart, F.; Kotakoski, J.; Krasheninnikov, A.V. Structural defects in graphene. ACS nano 2011, 5, 26-41.

- Tritt, T.M. Thermoelectric materials: Principles, structure, properties, and applications. 2002.

- Amollo, T.A.; Mola, G.T.; Kirui, M.; Nyamori, V.O. Graphene for thermoelectric applications: prospects and challenges. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences 2018, 43, 133-157.

- Fickl, B.; Heinzle, S.; Gstöttenmayr, S.; Emri, D.; Blazevic, F.; Artner, W.; Dipolt, C.; Eder, D.; Bayer, B.C. Challenges in Chemical Vapour Deposition of Graphene on Metallurgical Alloys Exemplified for NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. BHM Berg-und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 2024, 169, 357-365.

- Kim, D.-W.; Heo, U.S.; Kim, K.-S.; Park, D.-W. One-step synthesis of TiC/multilayer graphene composite by thermal plasma. Current Applied Physics 2018, 18, 551-558.

- Blodgett, M.P.; Ukpabi, C.V.; Nagy, P.B. Surface roughness influence on eddy current electrical conductivity measurements. 2003.

- Romero, C.; Domínguez, C.; Villemur, J.; Botas, C.; Gordo, E. Effect of the graphene-based material on the conductivity and corrosion behaviour of PTFE/graphene-based composites coatings on titanium for PEM fuel cell bipolar plates. Progress in Organic Coatings 2024, 194, 108587.

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Sun, B.; Ma, S.; Guan, J.; Jiang, Z.; Song, K.; Hu, H. Enhanced electrical and mechanical properties of graphene/copper composite through reduced graphene oxide-assisted coating. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 8121-8131.

- Mohamed, M.; Abd-El-Nabey, B. Corrosion performance of a steel surface modified by a robust graphene-based superhydrophobic film with hierarchical roughness. Journal of Materials Science 2022, 57, 11376-11391.

- Geringer, V.; Liebmann, M.; Echtermeyer, T.; Runte, S.; Schmidt, M.; Rückamp, R.; Lemme, M.; Morgenstern, M. Intrinsic and extrinsic corrugation of monolayer graphene deposited on SiO 2. Physical review letters 2009, 102, 076102.

- Lui, C.H.; Liu, L.; Mak, K.F.; Flynn, G.W.; Heinz, T.F. Ultraflat graphene. Nature 2009, 462, 339-341.

- Tetlow, H.; De Boer, J.P.; Ford, I.J.; Vvedensky, D.D.; Coraux, J.; Kantorovich, L. Growth of epitaxial graphene: Theory and experiment. Physics reports 2014, 542, 195-295.

- Withanage, S.; Nanayakkara, T.; Wijewardena, U.K.; Kriisa, A.; Mani, R. The role of surface morphology on nucleation density limitation during the CVD growth of graphene and the factors influencing graphene wrinkle formation. MRS Advances 2019, 4, 3337-3345.

- Akinay, Y.; Topuz, M.; Gunes, U.; Gokdemir, M.E.; Cetin, T. recent developments in 2D MXene-filled bioinspired composites for biomedical applications. Journal of Materials Science 2025, 1-30.

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Dutta, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xin, M.; Du, S.; Xu, G.; Cheng, H. Thermoelectric porous laser-induced graphene-based strain-temperature decoupling and self-powered sensing. Nature communications 2025, 16, 792.

- Khoso, N.A.; Jiao, X.; GuangYu, X.; Tian, S.; Wang, J. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of graphene based nanocomposite coated self-powered wearable e-textiles for energy harvesting from human body heat. RSC advances 2021, 11, 16675-16687.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).