Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

27 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Planaria Husbandry

2.3. Core Facilities

2.4. HEK 293 Cell Culture and Spheroids

2.5. Protein Expression and Purification

2.6. Confocal Microscopy

2.7. Negative Staining

2.8. Biological SAXS

2.9. Planar Bilayer

2.10. Epigenetics Analysis Differential Methylation

2.11. ATP Assay

2.12. Hypertrophy Assay

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

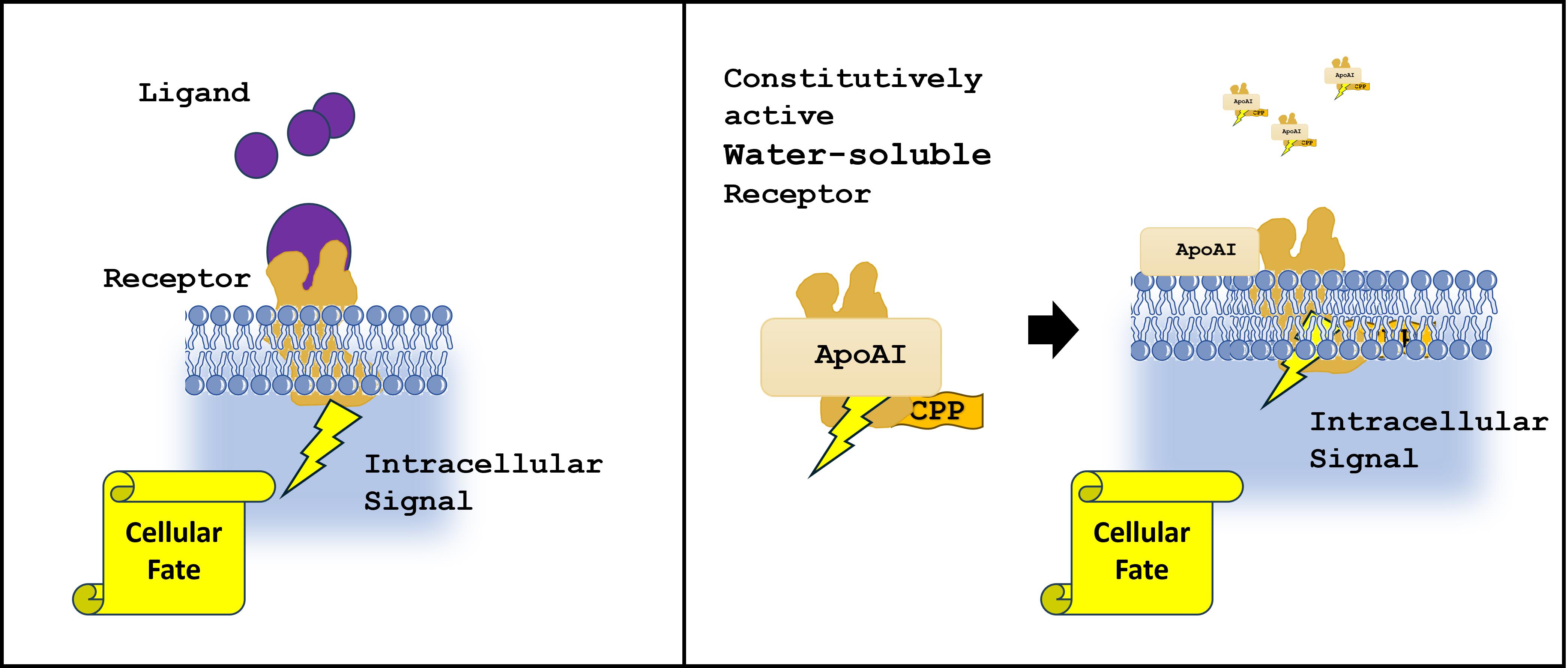

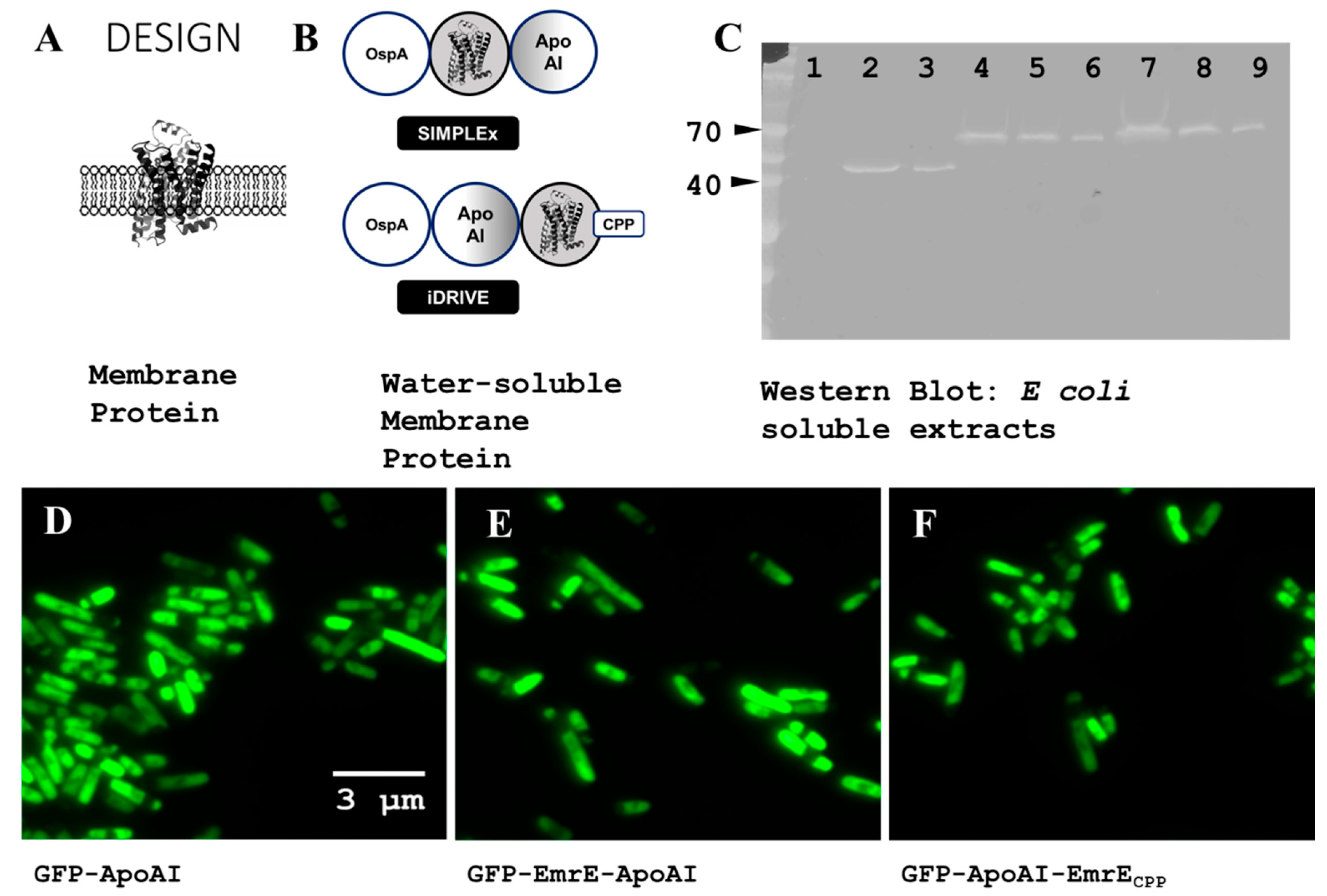

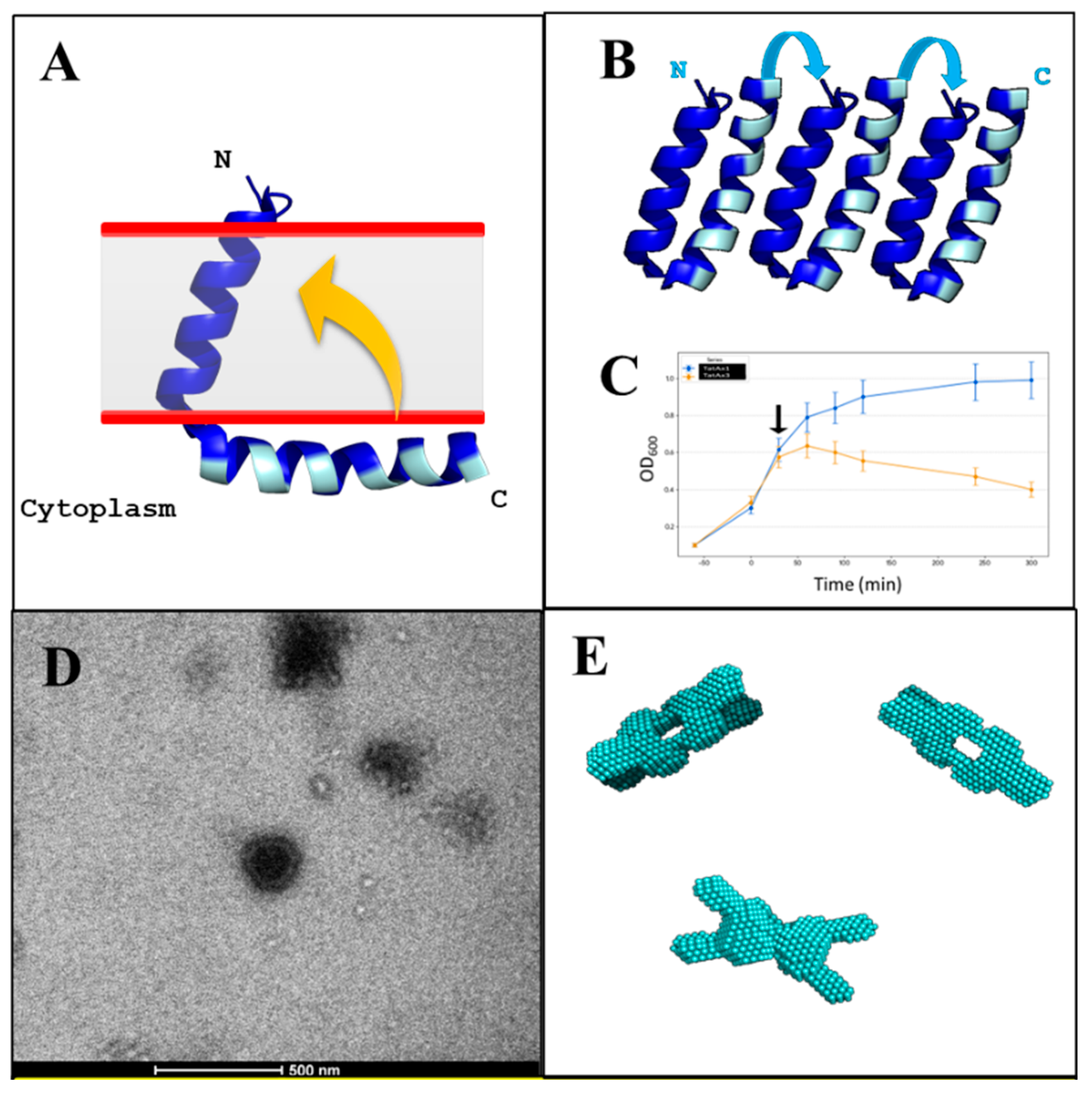

3.1. Design of iDRIVE (In Vivo Deployment of Recombinant Viable IMPs)

3.2. iDRIVE Interacts with Quiescent and Proliferating Cells

3.3. iDRIVE Allows IMPs to Re-Insert into the Plasma Membrane

3.4. iDRIVE Allows IMPs to Activate Signal Pathways In Vitro

3.5. iDRIVE Allows IMPs to Activate Signal Pathways In Vitro. The Case of Myotube Hypertrophy

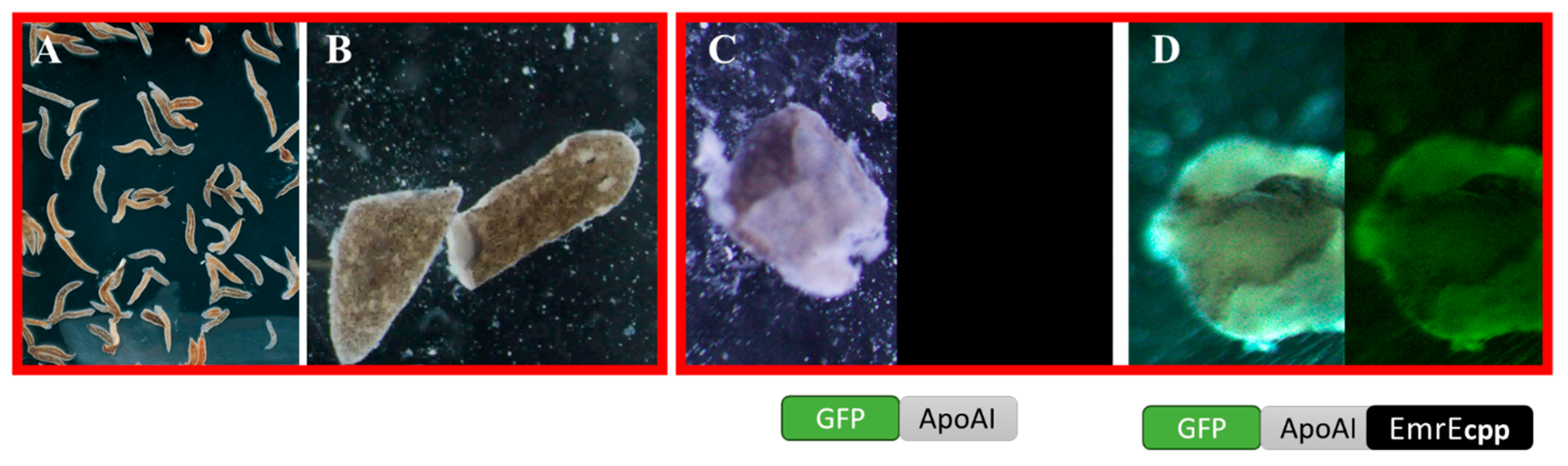

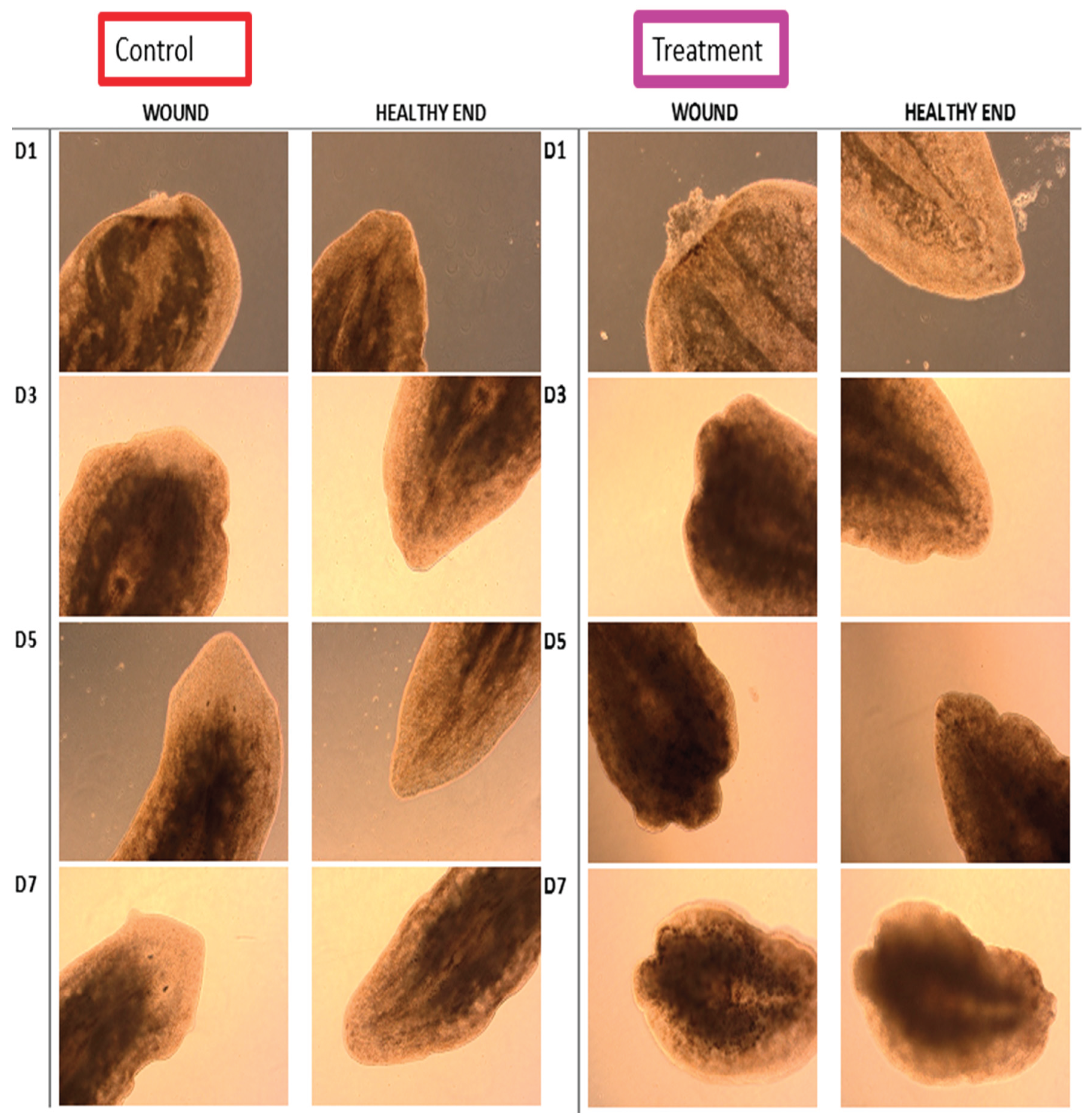

3.6. iDRIVE Allows IMPs to Activate Signal Pathways In Vivo. The Case of Planaria Regeneration

4. Conclusion

References

- Wallin, E.; von Heijne, G. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms . Protein Sci 1998, 7(4), 1029–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedin, L.E.; Illergard, K.; Elofsson, A. An introduction to membrane proteins . J Proteome Res 2011, 10(8), 3324–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielli, J.F.; Harvey, E.N. The tension at the surface of mackerel egg oil, with remarks on the nature of the cell surface . Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology 1935, 5(4), 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, M.; Furthmayr, H.; Marchesi, V.T. Primary structure of human erythrocyte glycophorin A. Isolation and characterization of peptides and complete amino acid sequence . Biochemistry 1978, 17(22), 4756–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, C.G. Overexpression of mammalian integral membrane proteins for structural studies . FEBS Lett 2001, 504(3), 94–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedfalk, K. Further advances in the production of membrane proteins in Pichia pastoris . Bioengineered 2013, 4(6), 363–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.J. Stabilizing membrane proteins through protein engineering . Curr Opin Chem Biol 2013, 17(3), 427–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrachi, D. Making water-soluble integral membrane proteins in vivo using an amphipathic protein fusion strategy . Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S. QTY code enables design of detergent-free chemokine receptors that retain ligand-binding activities . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115(37), E8652–E8659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroentomeechai, T. A universal glycoenzyme biosynthesis pipeline that enables efficient cell-free remodeling of glycans . Nat Commun 2022, 13(1), 6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulezian, E. Membrane protein production and formulation for drug discovery . Trends Pharmacol Sci 2021, 42(8), 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, C.S. Tackling Undruggable Targets with Designer Peptidomimetics and Synthetic Biologics . Chem Rev 2024, 124(22), 13020–13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.R.P.; Duncan, E.M. Laboratory Maintenance and Propagation of Freshwater Planarians . Curr Protoc Microbiol 2020, 59(1), p. e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuchi, K. Different morphologies of human embryonic kidney 293T cells in various types of culture dishes . Cytotechnology 2020, 72(1), 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.A. Structural analysis of RNA helicases with small-angle X-ray scattering . Methods Enzymol 2012, 511, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Svergun, D. Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria . Journal of Applied Crystallography 1992, 25(4), 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, D.; Svergun, D.I. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering . J Appl Crystallogr 2009, 42 Pt 2, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharian, E. Recording of ion channel activity in planar lipid bilayer experiments . Methods Mol Biol 2013, 998, 109–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrachi, D. A water-soluble DsbB variant that catalyzes disulfide-bond formation in vivo . Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13(9), 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricerri, M.A. Interaction of apolipoprotein A-I in three different conformations with palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidylcholine vesicles . J Lipid Res 2002, 43(2), 187–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.C.; Posey, N.D.; Tew, G.N. Protein Binding and Release by Polymeric Cell-Penetrating Peptide Mimics . Biomacromolecules 2022, 23(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaby, A.W. Methods for analysis of size-exclusion chromatography-small-angle X-ray scattering and reconstruction of protein scattering . J Appl Crystallogr 2015, 48 Pt 4, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalf, S.M.; Wu, Q.; Guo, S. Molecular basis of cell fate plasticity - insights from the privileged cells . Curr Opin Genet Dev 2025. 93, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, J.C. Stem cell systems and regeneration in planaria . Dev Genes Evol 2013, 223(1-2), 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.E.; Wang, I.E.; Reddien, P.W. Clonogenic neoblasts are pluripotent adult stem cells that underlie planarian regeneration . Science 2011, 332(6031), 811–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheon, G.W.; Bolhuis, A. The archaeal twin-arginine translocation pathway . Biochem Soc Trans 2003, 31 Pt 3, 686–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, T.H. Folding and self-assembly of the TatA translocation pore based on a charge zipper mechanism . Cell 2013, 152(1-2), 316–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohlke, U. The TatA component of the twin-arginine protein transport system forms channel complexes of variable diameter . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102(30), 10482–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Romero, H.; Ros, U.; Garcia-Saez, A.J. Pore formation in regulated cell death . EMBO J 2020, 39(23), p. e105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iino, H. Small-angle X-ray scattering analysis reveals the ATP-bound monomeric state of the ATPase domain from the homodimeric MutL endonuclease, a GHKL phosphotransferase superfamily protein . Extremophiles 2015, 19(3), 643–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doonan, F.; Cotter, T.G. Morphological assessment of apoptosis . Methods 2008, 44(3), 200–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.J. Puncta intended: connecting the dots between autophagy and cell stress networks . Autophagy 2021, 17(4), 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonavane, P.R.; Willert, K. Controlling Wnt Signaling Specificity and Implications for Targeting WNTs Pharmacologically . Handb Exp Pharmacol 2021, 269, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Marin, D. Frizzled receptors: gatekeepers of Wnt signaling in development and disease . Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13, 1599355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities . Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7(1), p. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z. CHIR99021 enhances Klf4 Expression through beta-Catenin Signaling and miR-7a Regulation in J1 Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells . PLoS One 2016, 11(3), e0150936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S. Pleiotropy of glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition by CHIR99021 promotes self-renewal of embryonic stem cells from refractory mouse strains . PLoS One 2012, 7(4), e35892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L. Cryo-EM structure of constitutively active human Frizzled 7 in complex with heterotrimeric G(s) . Cell Res 2021, 31(12), 1311–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, R.; Wenzel-Seifert, K. Constitutive activity of G-protein-coupled receptors: cause of disease and common property of wild-type receptors . Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2002, 366(5), 381–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, J.H. WNT-induced association of Frizzled and LRP6 is not sufficient for the initiation of WNT/beta-catenin signaling . Nat Commun 2025, 16(1), 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinato, G.; Wen, X.; Zhang, N. Engineering Strategies for the Formation of Embryoid Bodies from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells . Stem Cells Dev 2015, 24(14), 1595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurer, F. Standard Gibbs energy of metabolic reactions: II. Glucose-6-phosphatase reaction and ATP hydrolysis . Biophys Chem 2017, 223, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueggemann, L.I.; Sullivan, J.M. HEK293S cells have functional retinoid processing machinery . J Gen Physiol 2002, 119(6), 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, A.R. Activation of retinoic acid receptors by dihydroretinoids . Mol Pharmacol 2009, 76(6), 1228–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T. CHIR99021 combined with retinoic acid promotes the differentiation of primordial germ cells from human embryonic stem cells . Oncotarget 2017, 8(5), 7814–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagnocchi, L.; Mazzoleni, S.; Zippo, A. Integration of Signaling Pathways with the Epigenetic Machinery in the Maintenance of Stem Cells . In Stem Cells Int; 2016; p. 8652748. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Pharmacologically blocking p53-dependent apoptosis protects intestinal stem cells and mice from radiation . Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semsarian, C. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) induces myotube hypertrophy associated with an increase in anaerobic glycolysis in a clonal skeletal-muscle cell model . Biochem J 1999, 339 Pt 2)(Pt 2, 443–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.P. G protein-coupled receptor 56 regulates mechanical overload-induced muscle hypertrophy . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(44), 15756–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, T.; Hall, R.A. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors: structure, signaling, physiology, and pathophysiology . Physiol Rev 2022, 102(4), 1587–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoveken, H.M. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors are activated by exposure of a cryptic tethered agonist . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112(19), 6194–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallouli, R. G protein selectivity profile of GPR56/ADGRG1 and its effect on downstream effectors . Cell Mol Life Sci 2024, 81(1), p. 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H. The IGF1 Signaling Pathway: From Basic Concepts to Therapeutic Opportunities . Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(19). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, J.; Levin, M.; Mafe, S. Morphology changes induced by intercellular gap junction blocking: A reaction-diffusion mechanism . Biosystems 2021, 209, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, J.; Levin, M.; Mafe, S. Top-down perspectives on cell membrane potential and protein transcription . Sci Rep 2025, 16(1), p. 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, N.D. Insulin-like growth factor-I increases astrocyte intercellular gap junctional communication and connexin43 expression in vitro . J Neurosci Res 2003, 74(1), 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, N.; Dermietzel, R. Connexons and cell adhesion: a romantic phase . Histochem Cell Biol 2008, 130(1), 71–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenhan, T.; Aust, G.; Hamann, J. Sticky signaling--adhesion class G protein-coupled receptors take the stage . Sci Signal 2013, 6(276), p. re3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A. Planarians: an In Vivo Model for Regenerative Medicine . Int J Stem Cells 2015, 8(2), 128–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurley, K.A.; Rink, J.C.; Alvarado, A. Sanchez. Beta-catenin defines head versus tail identity during planarian regeneration and homeostasis . Science 2008, 319(5861), 323–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakugawa, S. Notum deacylates Wnt proteins to suppress signalling activity . Nature 2015, 519(7542), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Carreras, E. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling is required for pole-specific chromatin remodeling during planarian regeneration . Nat Commun 2023, 14(1), p. 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beane, W.S. A chemical genetics approach reveals H,K-ATPase-mediated membrane voltage is required for planarian head regeneration . Chem Biol 2011, 18(1), 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, C.E.; Alvarado, A.S. Systemic RNA Interference in Planarians by Feeding of dsRNA Containing Bacteria . Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1774, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C. Wnt signaling pathways in biology and disease: mechanisms and therapeutic advances . Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10(1), p. 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.X. Constitutive activation of G protein-coupled receptors and diseases: insights into mechanisms of activation and therapeutics . Pharmacol Ther 2008, 120(2), 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs): advances in structures, mechanisms, and drug discovery . Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9(1), p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. G Protein-Coupled Receptors: A Century of Research and Discovery . Circ Res 2024, 135(1), 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, K. and P.A. Insel, G. Protein-Coupled Receptors as Targets for Approved Drugs: How Many Targets and How Many Drugs? Mol Pharmacol 2018, 93(4), 251–258. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).