1. Introduction

The construction industry worldwide is experiencing a paradigm shift toward resource-efficient and low-impact material systems, with growing environmental limitations, resource depletion, and performance requirements of the contemporary infrastructure [

1,

2,

3]. Traditional substances that use Portland cement are still considered to be among the most energy-consuming construction products, which also leads to a substantial contribution to global carbon emissions and the exhaustion of natural resources [

2,

4,

5]. The challenges have been heating research on alternative binder systems that would provide high mechanical performance with minimum environmental burdens [

6,

7].

Alkali-activated materials have been considered as an exciting category of cementitious composites since they can use industrial by-products like slag and fly ash as the main precursors [

8,

9,

10]. Alkali-activated composites have significantly lower carbon footprints, greater chemical performance, and superior durability in hostile conditions compared to normal Portland cement systems [

2,

11]. The fact that they are versatile in the sense of adapting to various sources of aluminosilicate further increases their applicability to the practice of constructing resources efficiently [

7]. The behavior of alkali-activated systems is, however, quite sensitive to the binder chemistry, precursor activity, and microstructural growth, which requires special attention to the optimization of the mixture [

12].

The role of fly ash in alkali-activated composites is important because of its aluminosilicate composition and the morphology of the particles in the form of a sphere [

13,

14]. Chemical and mineralogical properties of fly ash, most notably the content of calcium, affect the kinetics of the reaction, as well as mechanical performance, to a significant extent [

15,

16,

17]. The early-age reactivity of a high-calcium fly ash is generally higher, and these fly ashes assist in the creation of products rich in calcium, contributing to higher rates of strength development, whereas fly ashes with low calcium levels can enhance the base of polymerization-related processes that help to enhance stability over time [

18,

19,

20]. Although fly ash tends to be used as a precursor to a binding agent, its application in the form of a partial fine aggregate replacement has been of interest recently because it could enhance the properties of particle packing and minimize the use of natural sand resources [

15,

21].

Although these are the benefits, the balancing of the binder synergy in alkali-activated slag fly ash systems is still not easy to achieve [

7,

22]. Over incorporation can cause dilution effects, low load-bearing capability, and deteriorated fresh-state properties, and under incarceration can restrict sustainability advantages [

23,

24]. Additionally, it has been established that alkali-activated systems are sensitive to the parameters of the mixture, like water demand, activator concentration, and size distribution, which have a direct influence on the workability and development of strength [

7,

25]. To overcome these issues, advanced modifiers that can be used to refine the microstructure and increase reaction efficiency to the detriment of fresh-state performance are necessary.

Nano silica has also drawn much interest as a nano-scale cementitious and alkali-activated systems nano-additive because of its tremendously high specific surface area and chemical reactivity [

26,

27,

28]. As a physical filler and a chemically active nucleation agent, nano-silica can hasten reaction kinetics and enhance the development of extra binding phases, as well as refit pore structure [

9,

28]. With alkali-activated composites, nano-silica has also been cited to help in increasing the interfacial transition zone, better packing density of particles, and raising the degree of polymerization, which results in better mechanical performance [

29,

30]. Nevertheless, nano-silica is highly dosage-sensitive, and its over-incorporation can lead to particle agglomeration, an increase in water requirement, and low workability [

26,

31].

Although many research works have analyzed nano-silica-modified cementitious and alkali-activated systems, most tests have been largely based on compressive strength as the key outcome of performance [

10]. This method will give little information on tensile and flexural behavior, which will be critical in determining cracking resistance, redistribution of stress, and the overall structural reliability [

12,

30]. Furthermore, the interplay of nano-silica and various types of fly ash, under regulated alkali-activated circumstances, has not been assessed in systematic appraisals of combined performance-based systems [

9].

Recently, it has been highlighted that there is a necessity to have a multi-indexed performance measurement system that goes beyond compressive strength to reflect the intricate mechanical action of advanced cementitious composites [

31,

32]. Normalized performance indices consisting of tensile and flexural performances give a better measure of material efficiency, particularly under systems where microstructural refinement and interface bonding are of primary importance [

12]. The use of fresh-state performance measures combined with mechanical indexes also increases the trustworthiness of mixture optimization, as it ensures constructability as well as mechanical efficiency [

33].

From an infrastructure engineering perspective, these performance-based evaluation systems are becoming increasingly demanded to ensure that advanced cementitious composites not only meet the strength requirements but also meet the constructability, crack resistance, and long-term service performance requirements under a realistic loading environment [

34,

35,

36,

37].

In recent infrastructure usage, complex stress conditions, time-dependent loading and aggressive service conditions to which materials are commonly subjected make durability and mechanical reliability equally important. As a result, assessment systems that combine fresh-state behavior and multi-directional mechanical performance give a more realistic assessment of in-service behavior when compared to strength-based measures alone. With these approaches, careful selection of materials, and optimization of mixtures can be made in a way that it addresses the needs of infrastructure systems where consistency in performance, resilience, and sustainability are critical design goals.

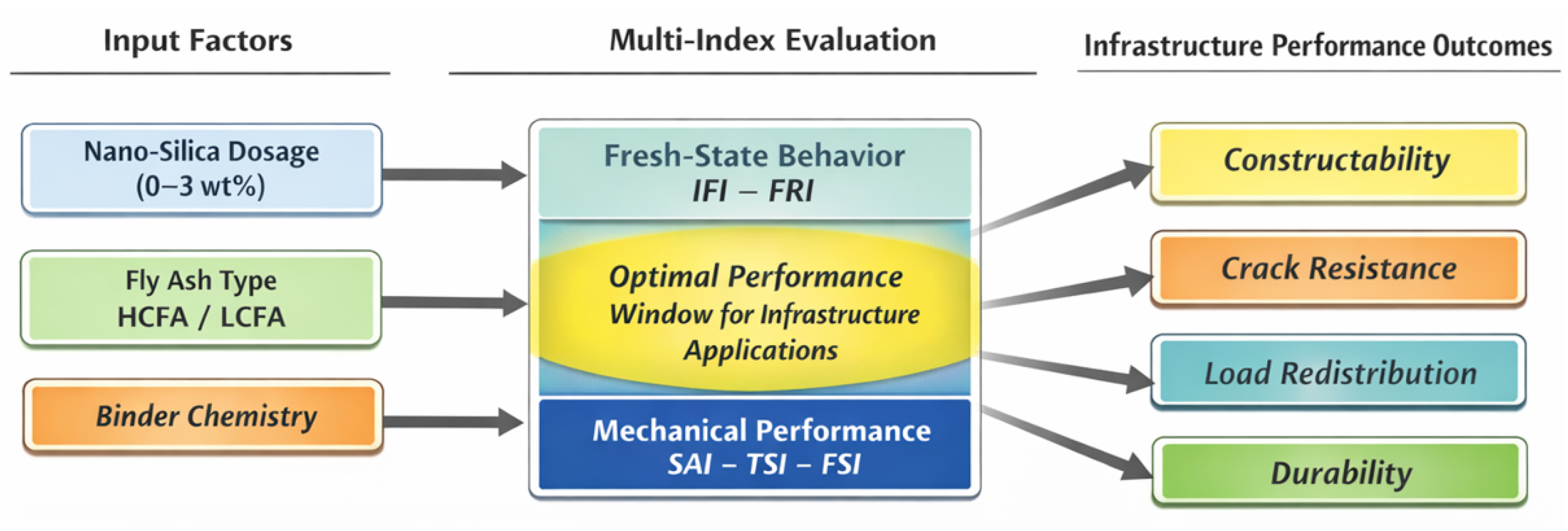

In line with this, the current study aims to examine the synergistic effect of nano-silica to control the interaction between the binder and the development of the resource-efficient alkali-activated composite using a holistic multi-index performance platform, which is based on the Strength Activity Index (SAI) as a reference index according to ASTM C618 [

38].

The composites that were prepared with slag and fly ash as alkali-activated slag and with low-calcium and high-calcium fly ash, with a fixed degree of fine aggregate replacement, and nano-silica added at different dosages. Flow-based indices were used to measure fresh-state behavior, and normalized compressive-, tensile-, and flexural-based indices were used to measure mechanical performance. An integration of these indicators provides the study with the complete perspective of nano-silica-enhanced synergy and establishes a rational base for the creation of high-performance, resource-effective alkali-activated composite systems with clear perspectives in terms of sustainable infrastructure applications.

It is essential to note that the proposed framework is intended to be a performance-integration methodology, rather than a mechanistic approach or a predictive modeling approach. Unlike the classical study of compressive strength as the selection of a performance metric, the current study involves an integrative multi-index design that integrates fresh-state indices (IFI, FRI) and normalized hardened-state indices (SAI, TSI, and FSI). To make such a performance-based measure, mineralogical (XRD) and microstructural (SEM) characterizations are given to decode the phase evolution, amorphous phase, and microstructural refinements of the evident fresh-state and mechanical performance of the identified materials.

The experimental and characterization methodology facilitates the study of the alkali-activated slag fly ash composites more comprehensively and performance-based, particularly systems where constructability and mechanical response are highly conditional on the nano-scale adjustment and interaction of binders.

2. Experimental Program and Methodology

As depicted in

Figure 1, the sequence of actions followed in the experimental outline applied in this study includes the selection of raw materials and mix proportions prior to the testing procedure which was conducted with the aim of studying nano-silica adjusted synergy in alkali-activated, resource-saving composites.

The framework also involves the mineralogical and microstructural characterization using the X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to give a fundamental insight into the mechanics of the interaction between the binder system and nano-silica incorporation. This combined description allows relating phase composition and microstructural refinement with reaction kinetics, matrix densification as well as fresh-state and mechanical performance of alkali-activated composites.

The workability and flowability retention properties were quantitatively measured by the use of the Initial Flow Index (IFI) and Flow Retention Index (FRI) in assessing fresh-state quantitative performance.

Mechanical performance was measured using a multi-index of the Strength Activity Index (SAI), which is defined in ASTM C618 [

38] and complemented by tensile-based and flexural-based indices, the Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI). The synergistic method enables the comprehensive evaluation of the influence of nano-silica inclusion on fresh and hardened properties that act as a performance-driven basis to the knowledge of the synergy of the role of binder and mixture optimization in the alkali-activated composite systems.

2.1. Materials and Constituent Properties

Slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), nano-silica (NS), an alkaline activator (AL), and fine aggregate (S) were used as the main constituents of this study. Their combination in the simultaneous application permitted the performance of the systematic analysis of the synergetic effect of slag binders, alkali-activated fly ash, and nano-silica activeness on the formation of resource-efficient alkali-activated composite systems.

The slag cement (SC) is a by-product of municipal waste, and it contains high proportions of amorphous materials. It was selected as a green option since it can minimize the environmental impact that is usually associated with the production of Portland cement.

The sources of the high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) were coal power plants, which utilize a wide variety of fuels. The HCFA is rich in CaO, and LCFA is rich in amorphous silica and alumina.

The nano-silica (NS) is recycled waste glass as a nano-scale modifier to bring synergy in binders and micro-structure fineness in the alkali-activated system. The nano-silica is largely amorphous, as shown by its chemical composition and physical characteristics (

Table 1 and

Table 2) and a very small particle size and very high specific surface area.

These properties make nano-silica a useful physical filler and chemically active moiety, inducing nucleation of reaction products and increasing the density of particle packing and the interfacial bonding of the alkali-activated matrix.

This paper used nano-silica in the percentage of total binder to provide a systematic assessment of the dosage-related impact of the nano-silica and fly ash types on the fresh-state behavior and hardened mechanical performance.

Mixed care was taken to eliminate agglomeration of nano-silica and to achieve even distribution of the nano-silica so that its full involvement in the alkali-activation process could be achieved.

The alkaline activator (AL) is sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) with a molar ratio of SiO2/Na2O =1.0 (50% SiO2 and 50% Na2O), which was chosen as an activator of slag-fly ash binders. Activation dosage was kept unchanged in all mixtures (AL/SC = 20% by mass) in order to isolate the effect of the addition of nano-silica.

The fine aggregate (S) was used in the aggregate phase and consisted of crushed sandstone with specific gravity of 2.58 and fineness modulus of 2.83; fly ash (FA/S = 20% by weight) was incorporated in the aggregate phase to partially substitute the fine aggregate, enhancing the ability of the particle to pack efficiently and decreasing the use of natural sand.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was used to establish the chemical composition of slag cement, types of fly ash, and nano-silica, and loss on ignition (LOI) was determined according to the standard procedures. The specific surface area and particle size distribution of slag cement and fly ash were calculated using the Blaine permeability technique and laser diffraction method, respectively. Conversely, the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method was used to determine the specific surface area of nano-silica because it is nano-scale in nature.

Table 1 shows the chemical compositions of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS), whereas

Table 2 presents the physical properties of these materials in a summary.

These characterizations form the requisite background on understanding the effect of nano-silica on the interaction of binders, the fresh-state behavior and the mechanical performance of the alkali-activated composites.

2.2. Mixture Design and Proportioning

Table 3 summarizes the mix proportions used in this work. Each of the alkali-activated composite mixtures was prepared to examine the effects of the incorporation of nano-silica and fly ash types on binder synergy and performance at constant baseline mixture parameters. The primary binder in all mixtures was slag cement (SC) and fly ash was added as a partial replacement of fine aggregates in all mixtures at 20% fly ash-sand (FA/S) proportion by weight. High-calcium fly ash (HCFA) and low-calcium fly ash (LCFA) were used to investigate the relationship between fly ash types and nano-silica dosage.

To determine the impact of nano-silica and fly ash types, the water-to-slag ratio (W/SC), alkali activator-to-slag ratio (AL/SC) were kept constant throughout the mixtures at 50% and 20%, respectively. Nano-silica was added in 0, 1, 2, and 3 wt% to the total binder content. The reference mixtures containing no nano-silica (NS = 0%) were used as control mixes to normalize the performance and make a comparative evaluation.

Fine aggregate was a mixture of crushed sandstone, which was controlled in terms of grading and was partially substituted by fly ash to increase the efficiency of particle packing and minimize the use of natural sand. To compare reliably and consistently different dosages of nano-silica and fly ash types, the mixtures were prepared under the same conditions in terms of mixing, casting, and curing conditions.

2.3. Experimental Procedures and Testing

The mineralogical properties, fresh-state behavior and mechanical performance of nano-silica-modified alkali-activated composites were compared through an organized experimental program that was carried out under controlled and consistent testing conditions. The experimental processes were planned to allow the comparison of the various nano-silica dosages and fly-ash types to be made in a reliable way so that they are relevant to the infrastructure-based performance assessment.

2.3.1. Mineralogical Characteristics of Constituent Materials

Mineralogical characterization of the raw materials was made to provide a basic platform on which the reactivity and interaction mechanisms of the raw materials in the nano-silica modified alkali-activated composite system could be understood. The analysis by X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to determine crystalline and amorphous phases in slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS). The resulting patterns of diffraction were qualitatively evaluated to determine the presence of crystalline phases containing calcium and amorphous aluminosilicate components, which are important in regulating reactivity and reaction between alkali activation and other components.

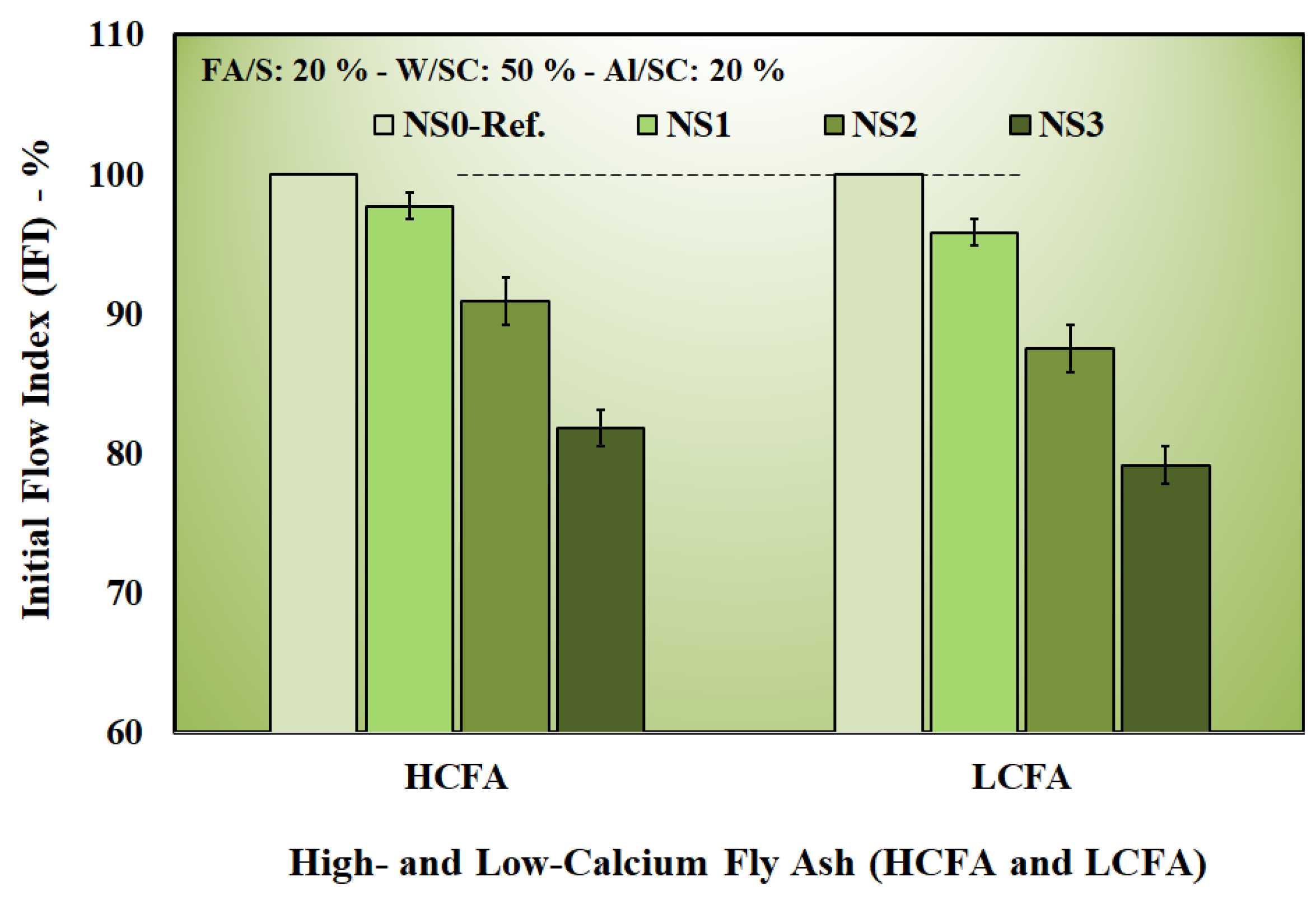

2.3.2. Fresh-State Flow Assessment

Flow-based indices were used to quantify the fresh-state performance of nano-silica modified alkali-activated composites to measure flowability and the retention of workability. Immediately after mixing, the Initial Flow Index (IFI) was obtained in a standard flow-table test following the guidelines of JIS A1150-JSA 2014 [

39] wherein the spread diameter of each mixture was normalized against the respective reference mixture devoid of nano-silica (NS = 0%). Flow Retention Index (FRI) was established after casting 15 minutes to evaluate the potential of the mixtures to retain their flowability. The measures of both indices were based on standardized procedures that made it possible to compare mixtures with varying nano-silica dosages and types of fly ash.

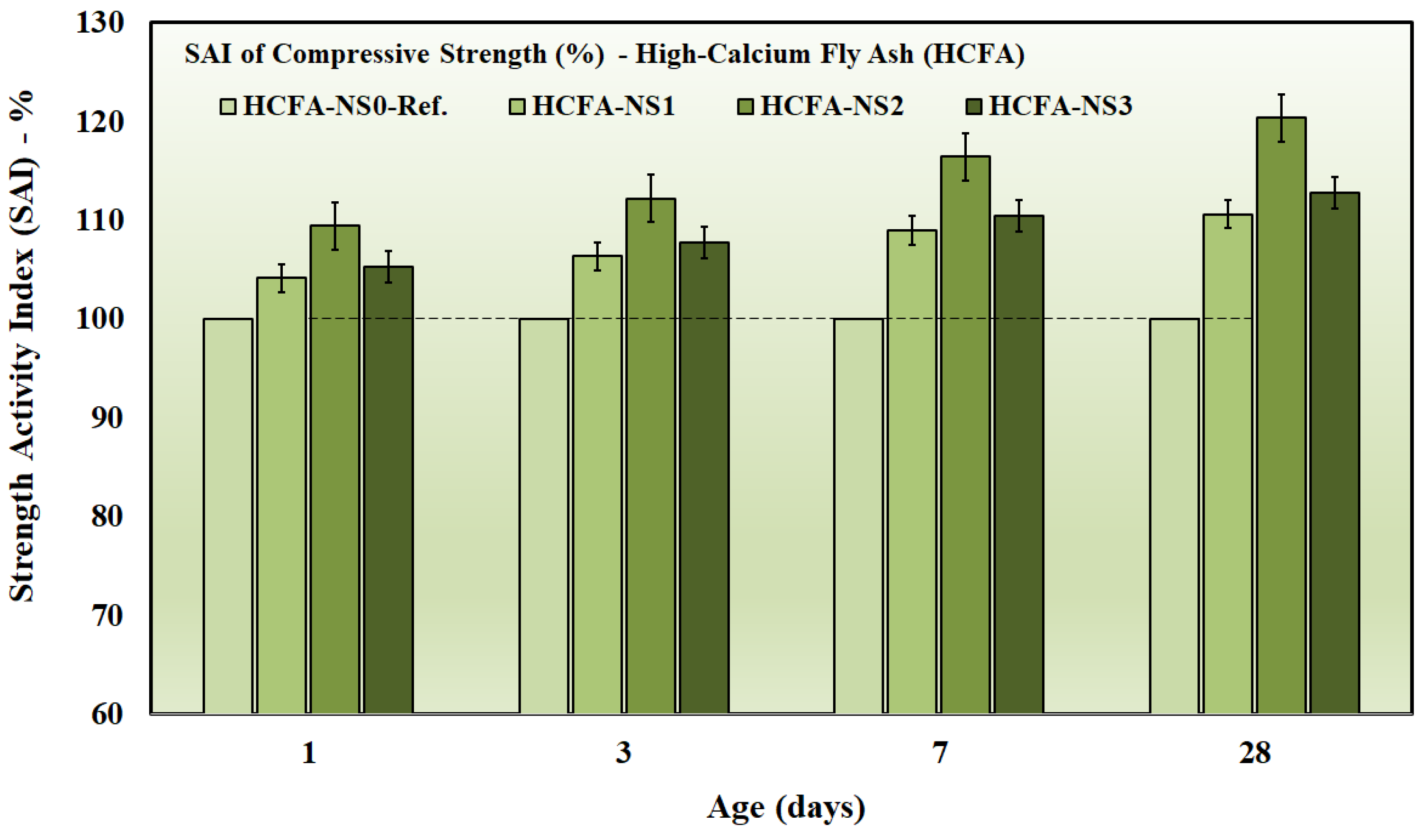

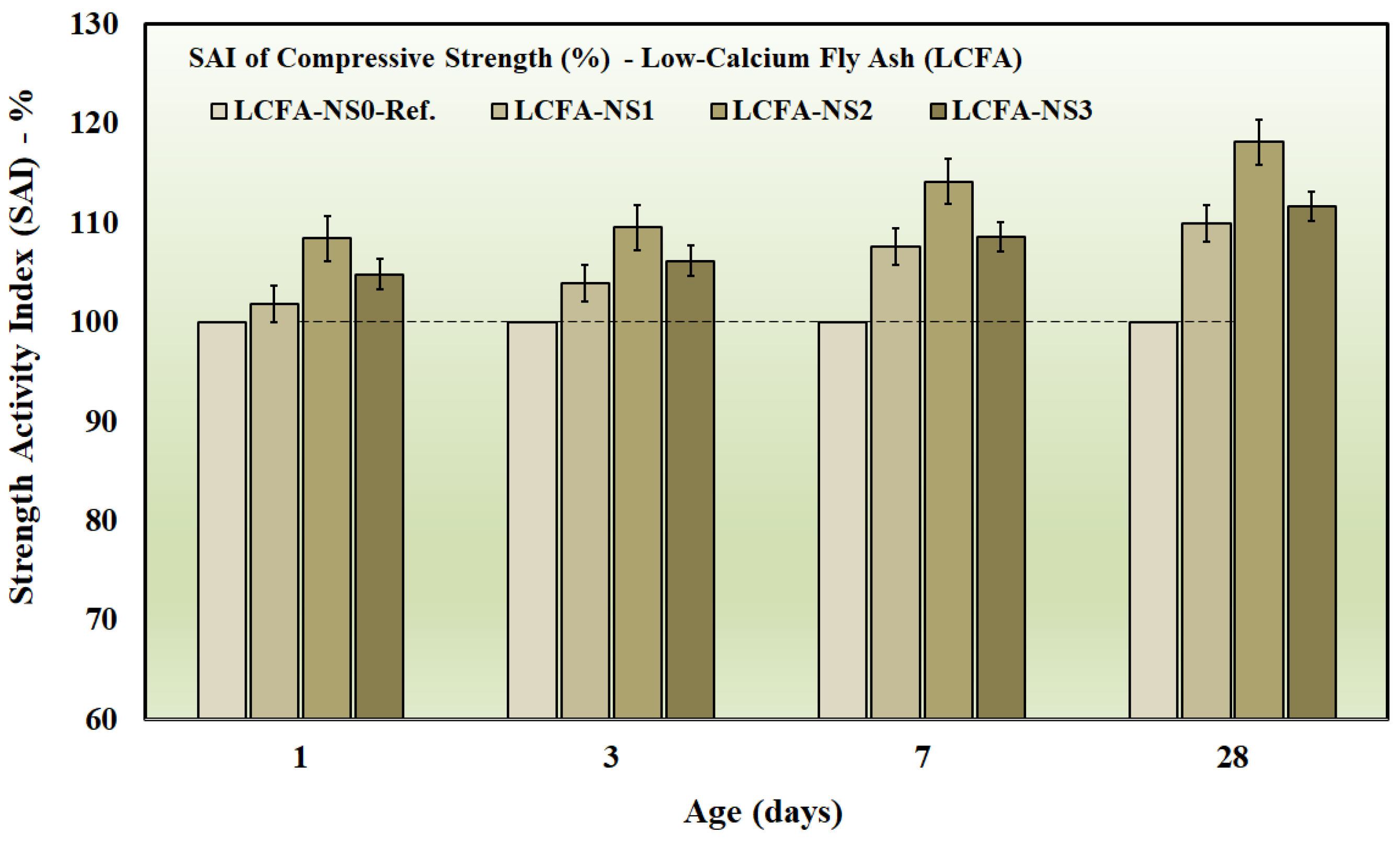

2.3.3. Mechanical Performance Evaluation

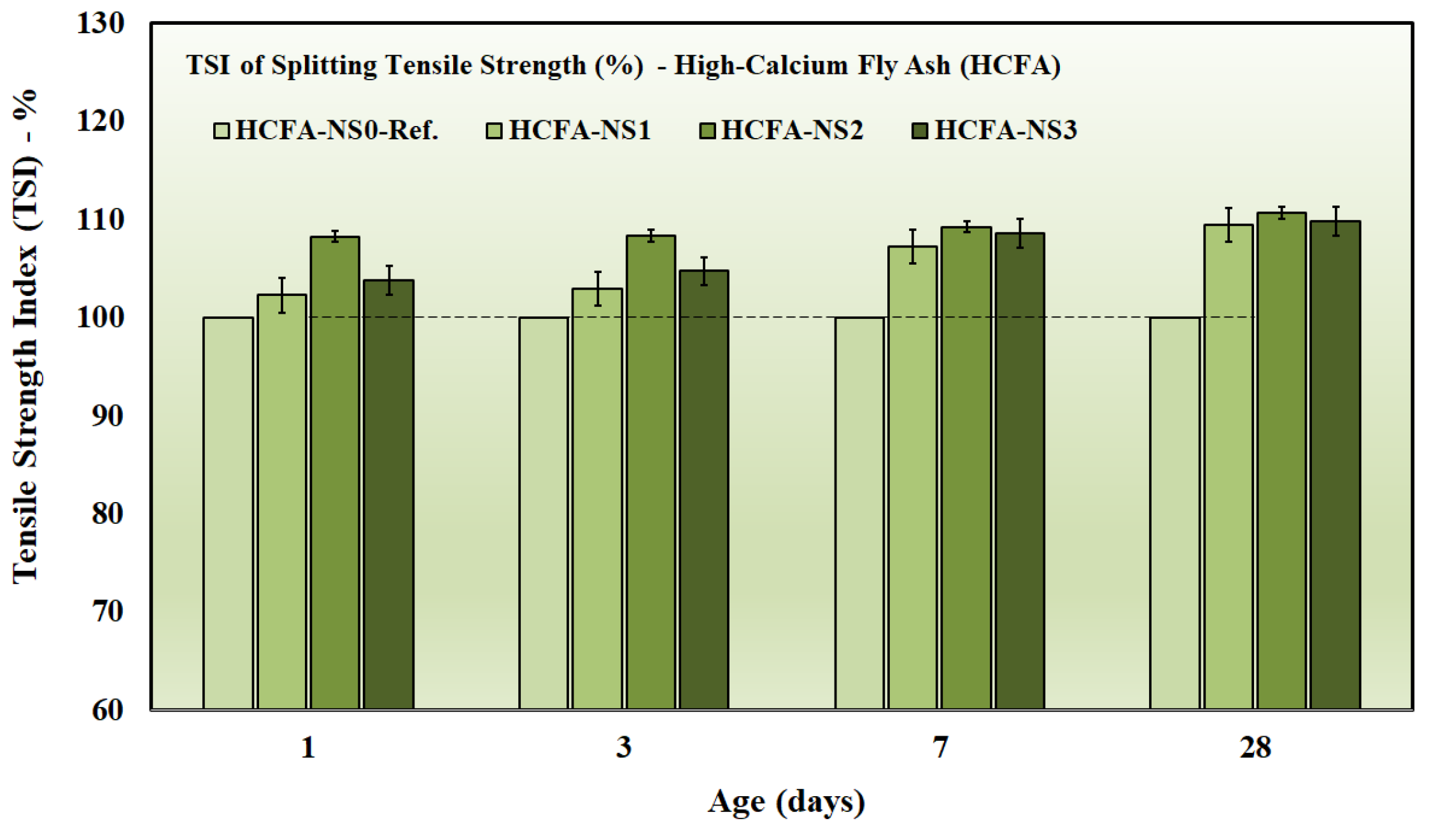

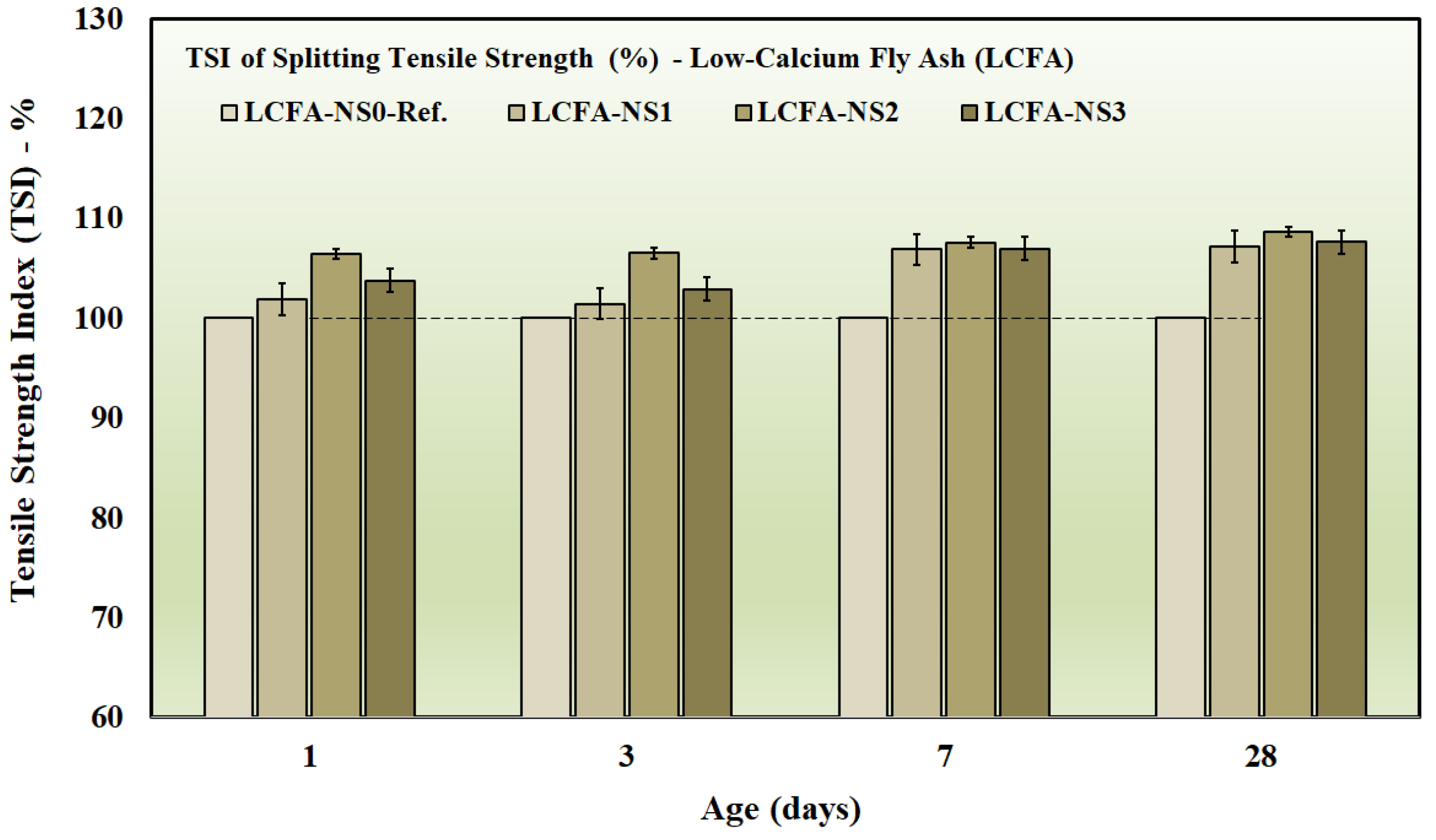

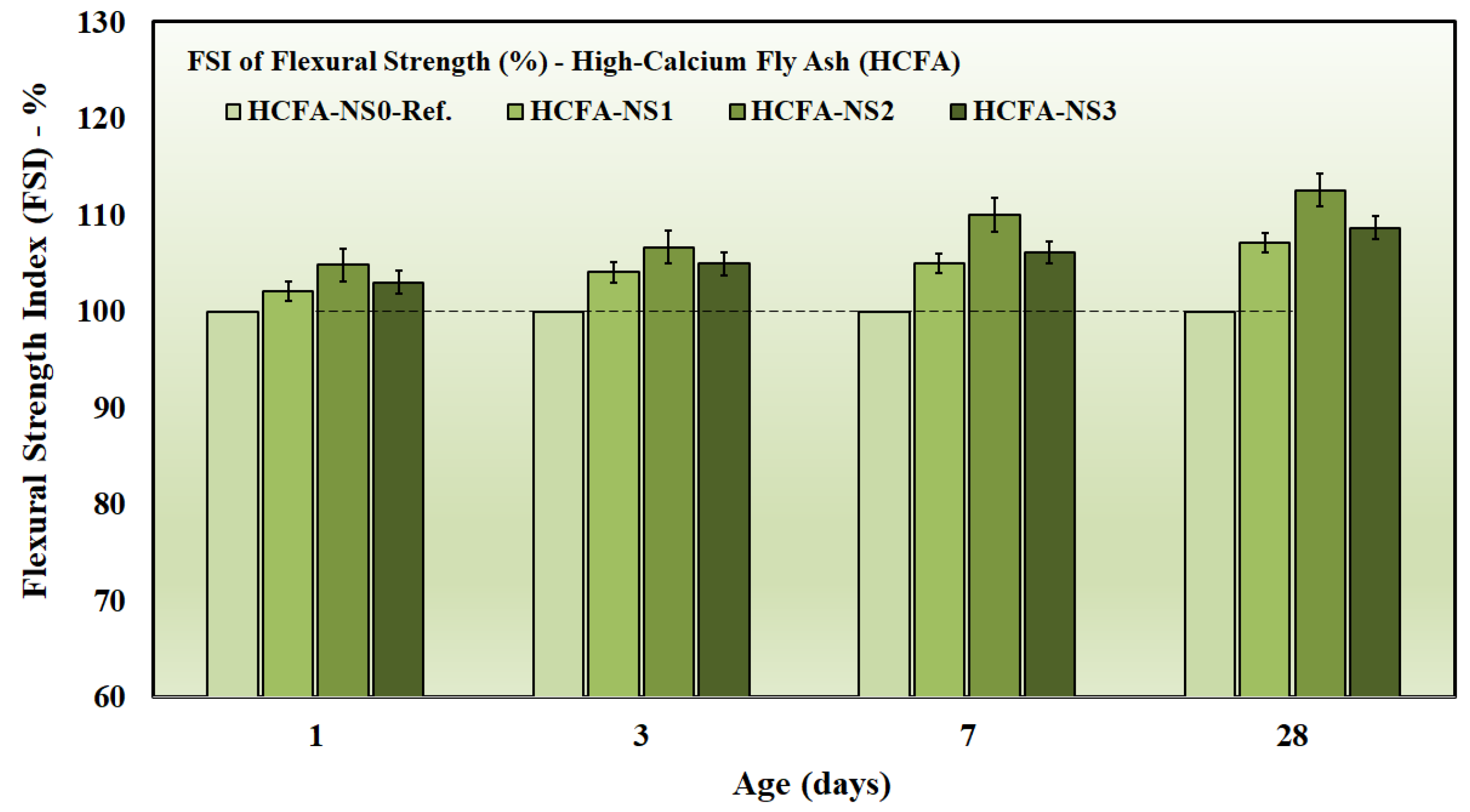

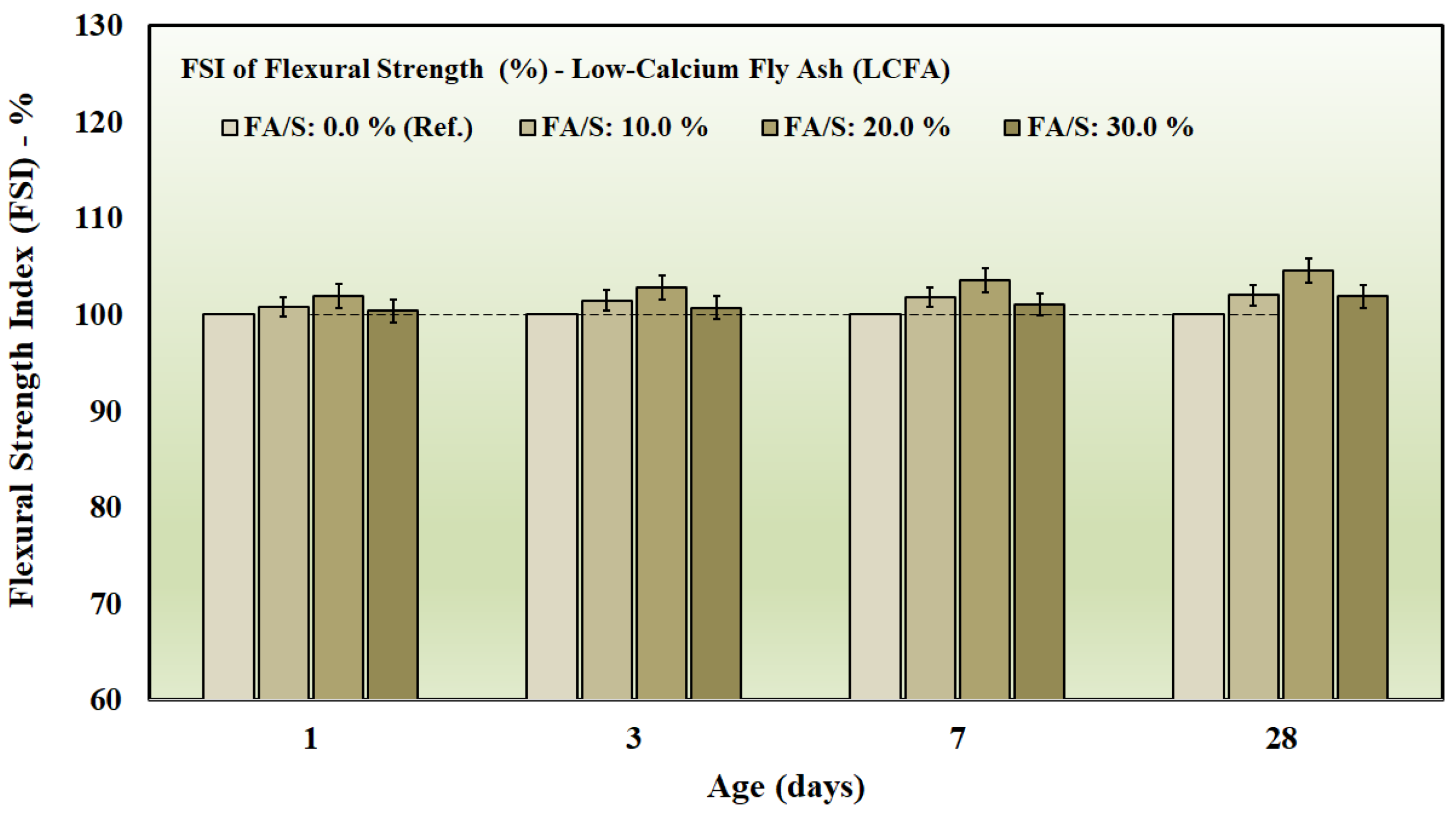

The nano-silica modified alkali-activated composites were tested in mechanical performance with respect to compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strength. Multi-index methodology was used to assess mechanical performance. The compressive strength was measured in terms of Strength Activity Index (SAI) which according to ASTM C618 [

38] is determined as the ratio of compressive strength of the nano-silica modified mixtures to the compressive strength of the corresponding reference mixtures without nano-silica (NS = 0%). The tensile and flexural performance was determined by testing in terms of Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) respectively. Both the indices were determined by dividing a measured splitting tensile and flexural strength of each mixture by the relevant reference mixtures, using the same normalization strategy as SAI. Compressive, splitting tensile and flexural strength tests were performed based on JIS A1108-JSA 2006a [

40], JIS A1113-JSA 2006c [

41], and JIS A1106-JSA 2006b [

42], respectively. All of the tests were conducted at curing ages of 1, 3, 7 and 28 days of specimens exposed to a controlled steam-curing regime. Cylindrical specimens (50 × 100 mm) were used to measure compressive as well as splitting tensile strengths, and prismatic specimens (40 × 40 × 160 mm) were used to measure flexural strength. Each mixture was tested on three specimens at each curing age.

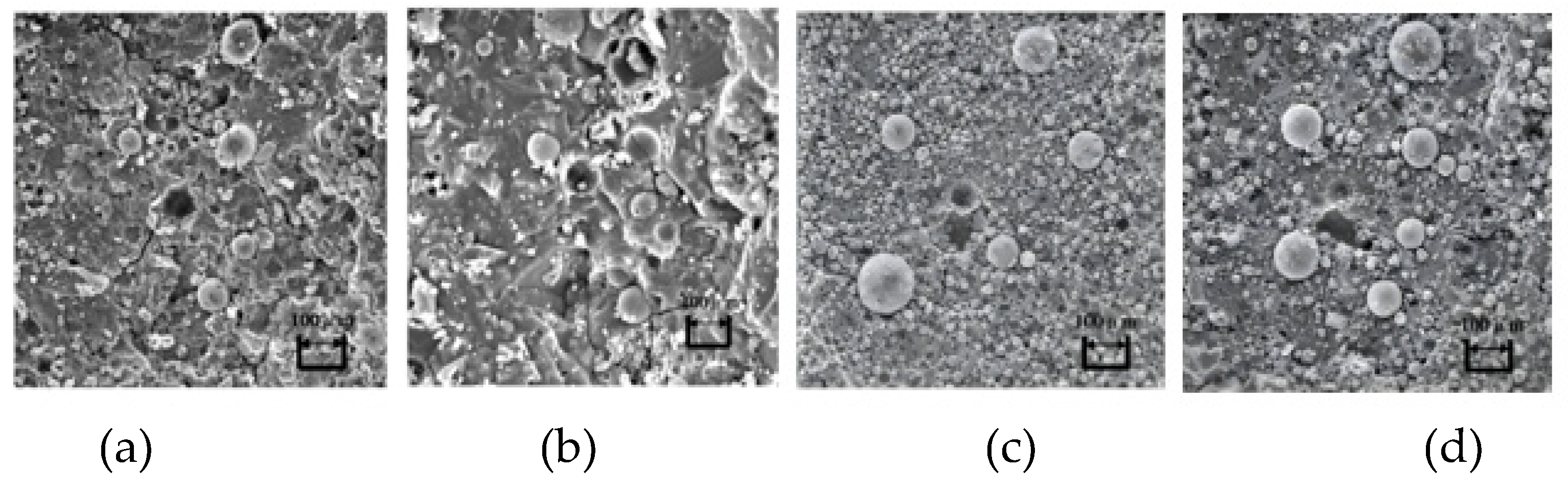

2.3.4. Microstructural Characterization (SEM)

To support the interpretation of the trends of fresh-state and mechanical performance, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used to scan the microstructural characteristics of the chosen alkali-activated composites. At 28 days of curing, representative specimens were made of reference mixtures and mixtures containing nano-silica. The morphology of the matrices, the distribution of the particles, the structure of the pore, and the relationship between the product of the reactions and the particles that had not reacted were observed using SEM.

4. Conclusions

This study revealed that the proposed multi-index performance is a comprehensive and systematic framework thorough foundation measurements the synergies of the nano-silica incorporation into the resource-efficient alkali-activated composites. The proposed framework facilitates the use of performance-based assessment, integrating the fresh-state flow indicators and strength-based mechanical indicators, thereby providing material assessment other than the conventional compressive strength-based techniques.

The performance of fresh-state systems based on the Initial Flow Index (IFI) and the Flow Retention Index (FRI) gradually declined as the dosage of the nano-silica increased in both HCFA-based systems and LCFA-based systems. This behavior is attributed to the increase in the surface area and the rate of reaction in the initial stage. Nevertheless, LCFA systems never showed limited flow retention and fresh-state stability as compared to HCFA systems because of the influence of low calcium concentrations and low reaction rates in inhibiting quick stiffening.

An intermediate nano-silica dosage of about 2 wt% was optimum, yielding the enhanced compressive, tensile, and flexural response with both fly ash systems. At this dosage concentration, the Strength Activity Index (SAI), Tensile Strength Index (TSI) and Flexural Strength Index (FSI) showed improved development of strength. An increase in the nano-silica content led to a decrease in the performance gains, and the results illustrated the need to optimize dosage to prevent the negative effects of excessive fineness and particle agglomeration.

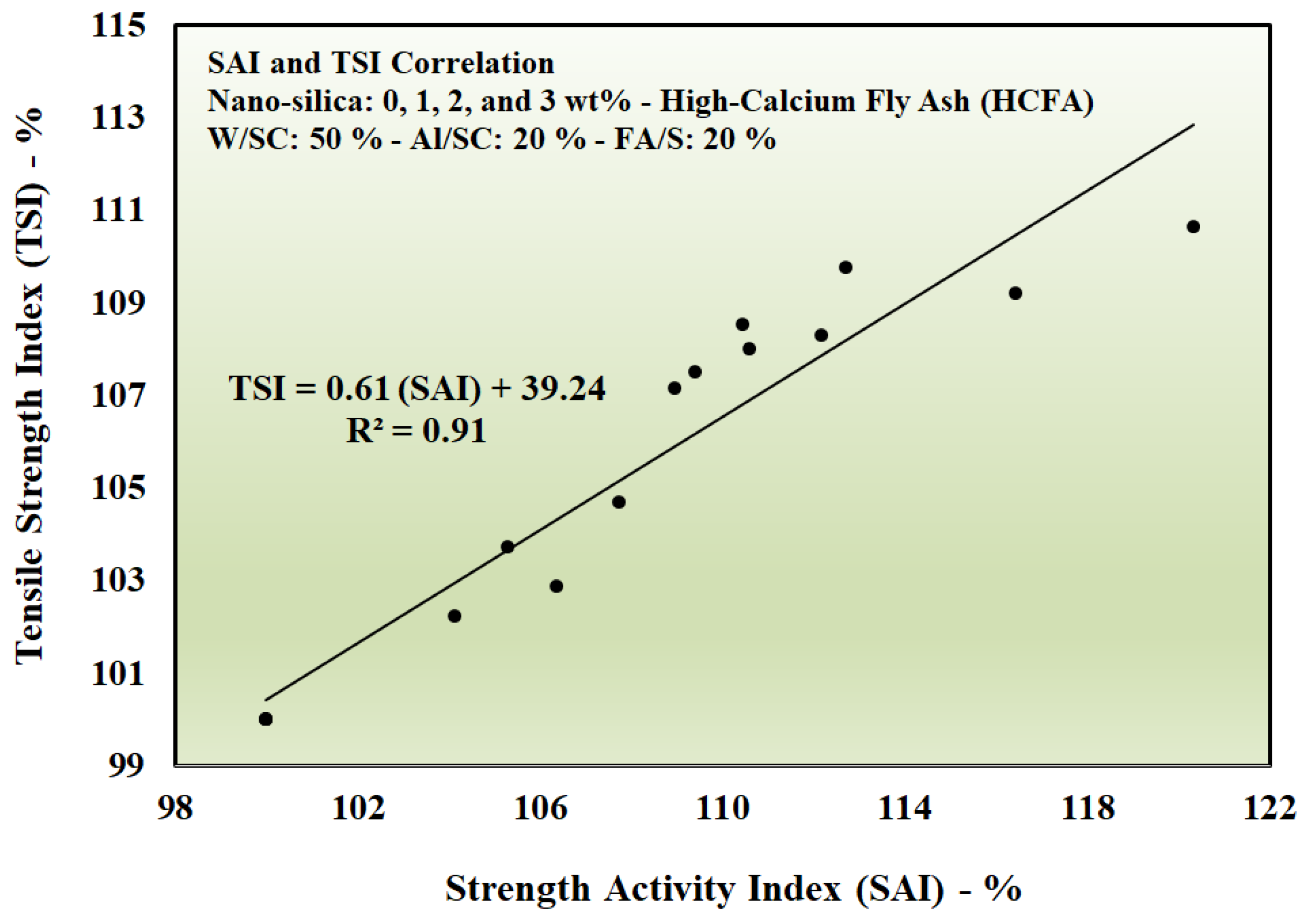

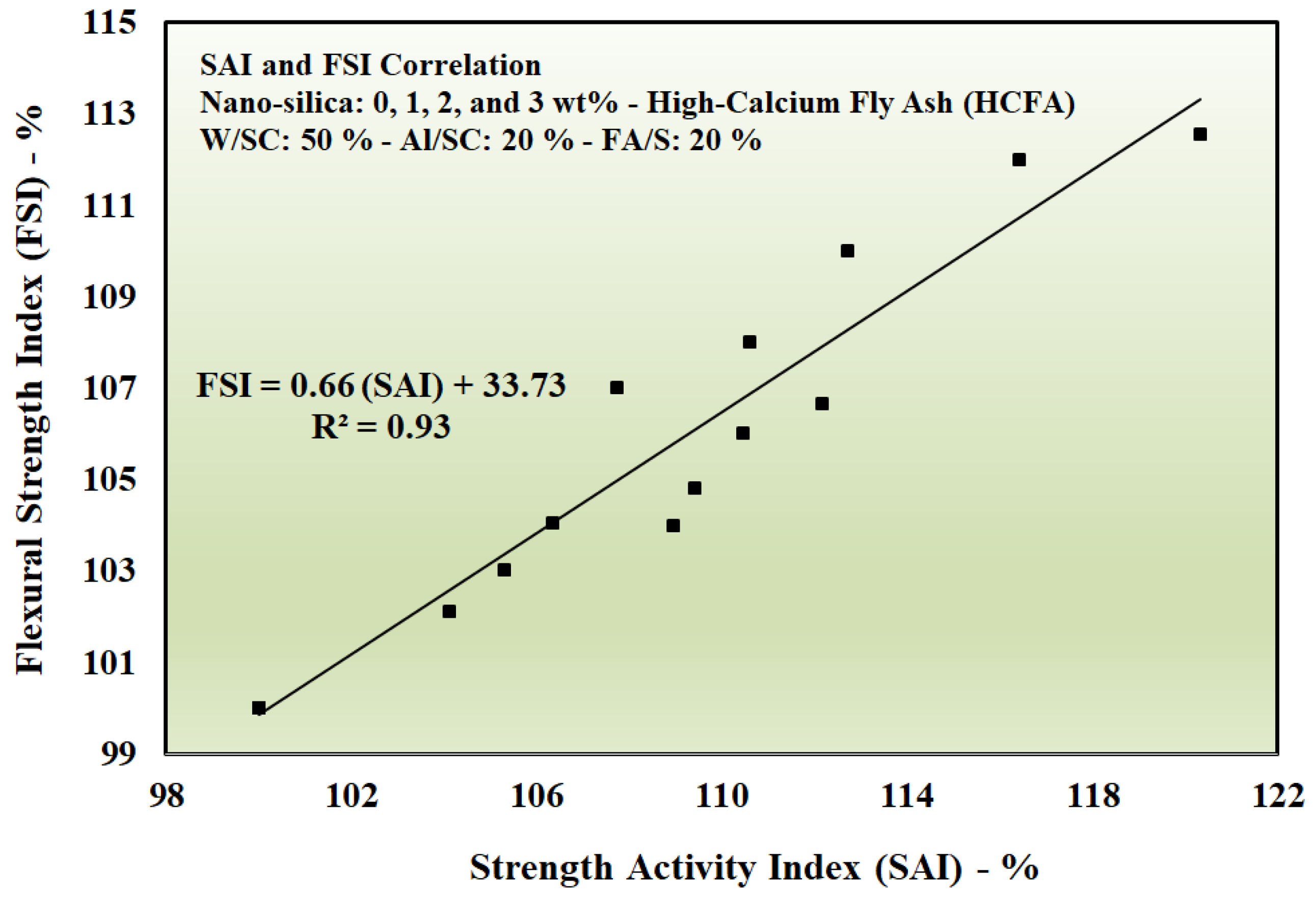

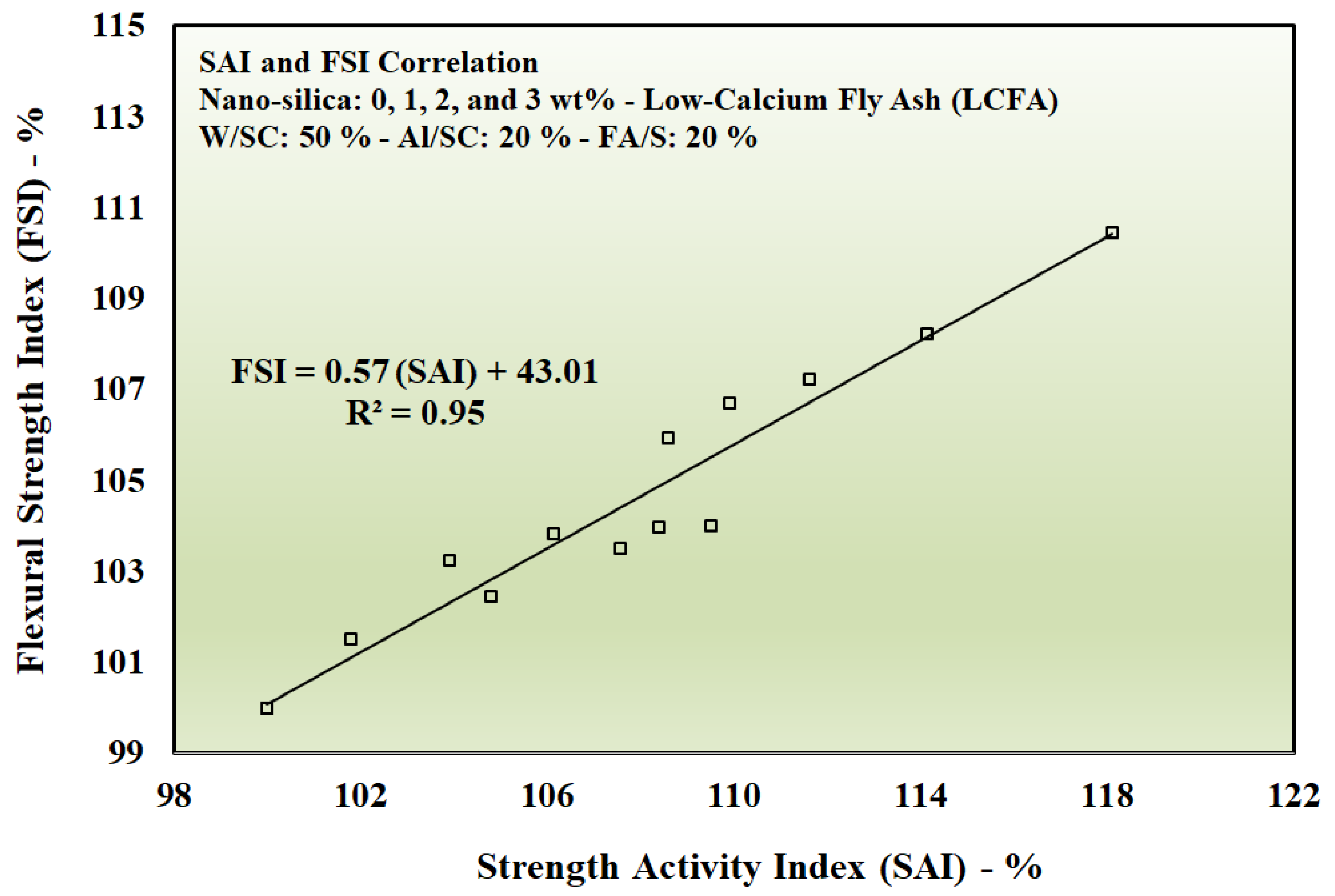

Correlation analyses of Strength Activity Index (SAI) and Tensile and Flexural Strength Index (TSI and FSI) revealed that it is not possible to reliably estimate tensile and flexural performance based only on compressive performance, particularly in nano-silica, fly ash, and alkali-activated composites, which react in different ways. Such findings suggest that mechanical synergy as well as load-transfer properties of alkali-activated composites require a multi-index evaluation.

Mineralogical and microstructural analyses (XRD and SEM) revealed that the effectiveness of the reaction, as well as the densification of the matrix and stress transfer, is determined by the interaction of amorphous aluminosilicate components, the availability of calcium, and the reactivity of nano-silica. An intermediate dosage of nano-silica (2 wt) was favorable to balance the nucleation and refinement of the microstructure, but a high dosage favored agglomeration, non-homogeneous nucleation, and low performance. These values agree with the experimentally determined patterns of fresh-state behavior and mechanical performance.

Collectively, the results endorse that the proposed multi-index framework is an effective methodological approach in the optimization of nano-silica dosage and directing the design of resource-efficient alkali-activated composites, which have proven to be relevant in sustainable infrastructure applications.

Figure 1.

Experimental framework for nano-silica enhanced alkali-activated composites.

Figure 1.

Experimental framework for nano-silica enhanced alkali-activated composites.

Figure 2.

Initial Flow Index (IFI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different nano-silica dosages.

Figure 2.

Initial Flow Index (IFI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different nano-silica dosages.

Figure 3.

Flow Retention Index (FRI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different nano-silica dosages.

Figure 3.

Flow Retention Index (FRI) of HCFA- and LCFA-based mixtures at different nano-silica dosages.

Figure 4.

Compressive Strength Activity Index (SAI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 4.

Compressive Strength Activity Index (SAI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 5.

Compressive Strength Activity Index (SAI) of LCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 5.

Compressive Strength Activity Index (SAI) of LCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 6.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 6.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 7.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 7.

Tensile Strength Index (TSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 8.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 8.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 9.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 9.

Flexural Strength Index (FSI) of HCFA-Based Alkali-Activated Composites Modified with Nano-Silica.

Figure 10.

SAI–TSI correlation for HCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 10.

SAI–TSI correlation for HCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 11.

SAI–TSI correlation for LCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 11.

SAI–TSI correlation for LCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 12.

SAI–FSI correlation for HCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 12.

SAI–FSI correlation for HCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 13.

SAI–FSI correlation for LCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 13.

SAI–FSI correlation for LCFA-based nano-silica–modified composites.

Figure 14.

Schematic of multi-index performance implications for infrastructure applications of alkali-activated composites.

Figure 14.

Schematic of multi-index performance implications for infrastructure applications of alkali-activated composites.

Figure 15.

XRD Patterns of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS).

Figure 15.

XRD Patterns of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS).

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS).

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS).

| Chemical Compositions (%) |

CaO |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

MgO |

Fe2O3 |

Na2O |

TiO2 |

P2O5 |

LOI |

| Slag Cement - (SC) |

43.1 |

32.5 |

13.5 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

| High-Calcium Fly Ash - (HCFA) |

18.8 |

48.8 |

19.8 |

1.5 |

3.8 |

1.2 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

1.7 |

| Low-Calcium Fly Ash - (LCFA) |

6.3 |

57.6 |

26.5 |

1.2 |

4.2 |

0.5 |

1.9 |

0.3 |

1.5 |

| Nano-Silica - (NS) |

0.6 |

98.2 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

0.2 |

Table 2.

Physical properties of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS).

Table 2.

Physical properties of slag cement (SC), high-calcium fly ash (HCFA), low-calcium fly ash (LCFA), and nano-silica (NS).

| Physical Properties |

Specific gravity

(g/cm3)

|

Specific surface area, Blaine

(cm2/g)

|

Specific surface area,

BET

(m2/g)

|

Average particle size

D50 (μm)

|

| Slag Cement - (SC) |

2.80 |

3750 |

--- |

6.48 |

| High-Calcium Fly Ash - (HCFA) |

2.80 |

3780 |

--- |

16.25 |

| Low-Calcium Fly Ash - (LCFA) |

2.14 |

3630 |

--- |

18.35 |

| Nano-Silica - (NS) |

2.20 |

--- |

85 |

0.04 |

Table 3.

Mix proportions of nano-silica–modified alkali-activated composites.

Table 3.

Mix proportions of nano-silica–modified alkali-activated composites.

| Mix ID |

Fly Ash Type |

NS

(%)

|

FA/S

(%)

|

W/SC

(%)

|

AL/SC

(%)

|

Mix Proportioning (kg/m3) |

Slag Cement

(SC)

|

Water

(W)

|

Alkali-Activator

(AL)

|

Fly Ash

(FA)

|

Sand

(S)

|

Nano-Silica

(NS)

|

| HCFA-NS0 – Ref. |

HCFA |

0 |

20 |

50 |

20 |

600 |

300 |

120 |

200 |

1000 |

0 |

| HCFA-NS1 |

1 |

594 |

6 |

| HCFA-NS2 |

2 |

588 |

12 |

| HCFA-NS3 |

3 |

582 |

18 |

| LCFA-NS0 – Ref. |

LCFA |

0 |

20 |

50 |

20 |

600 |

300 |

120 |

200 |

1000 |

0 |

| LCFA-NS1 |

1 |

594 |

6 |

| LCFA-NS2 |

2 |

588 |

12 |

| LCFA-NS3 |

3 |

582 |

18 |