Results

Metadichol Modulates NK Cell Surface Marker Expression

Results of treatment with Metadichol are illustrated in summarized

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The most striking observation (

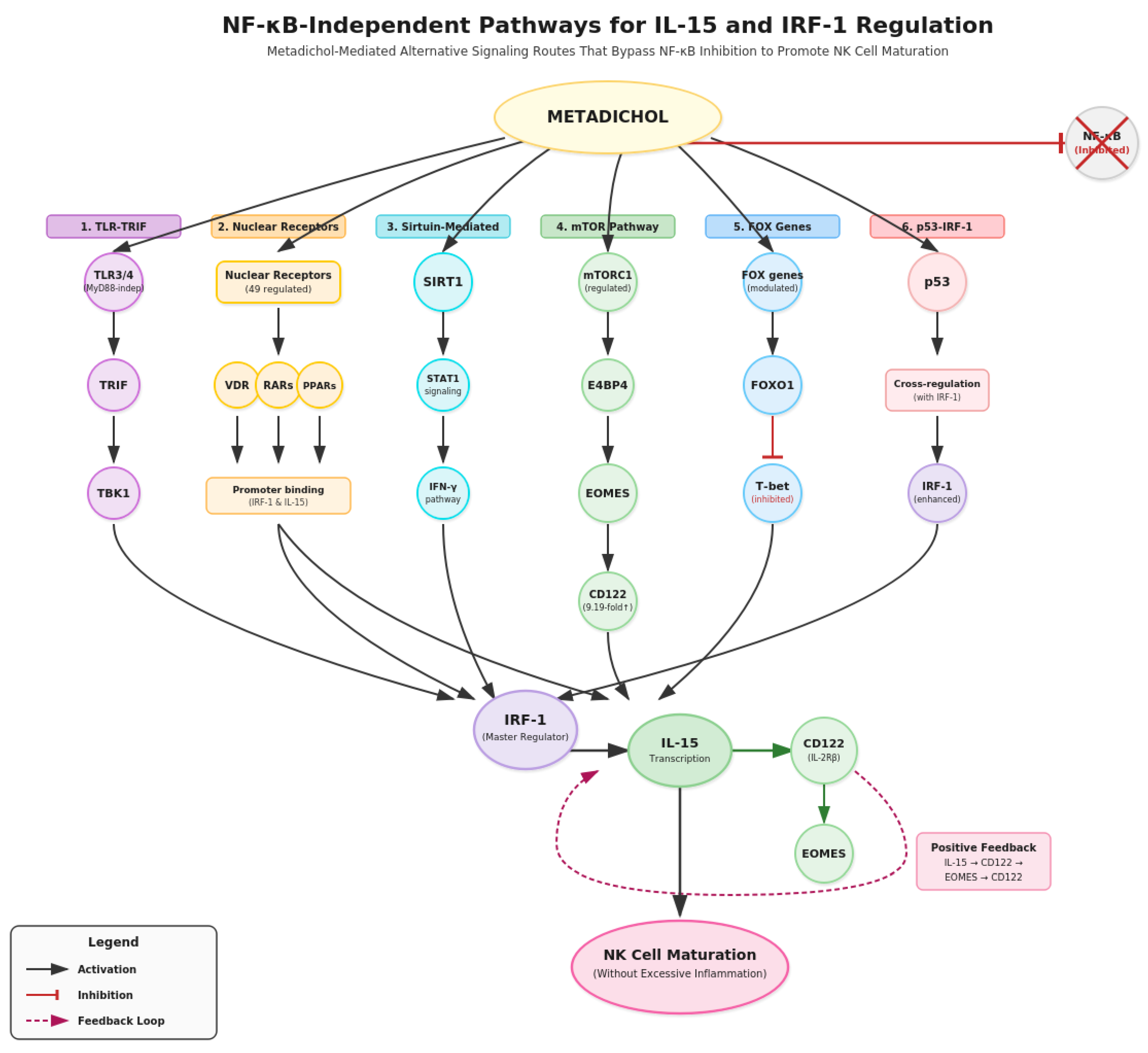

Figure 1) was dramatic upregulation of NKG2D at 1 pg/ml (8.59±3.74 fold, p<0.001). CD122 showed robust induction at 1 pg/ml (9.19±7.68 fold) and 100 ng/ml (9.14±6.42 fold, p<0.05). NKP80 demonstrated significant upregulation at 1 pg/ml (4.91±2.94 fold, p<0.05).

Heatmap of NK cell surface marker expression (

Figure 1) following Metadichol treatment. Expression of 20 NK cell-associated genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR across four Metadichol concentrations (1 pg, 100 pg, 1 ng, 100 ng/ml) normalized to untreated controls. Color intensity represents fold change relative to control (scale: 0-9).

Notable findings include robust CD122 upregulation at 1 pg/ml (9.19-fold) and 100 ng/ml (9.14-fold), dramatic

NKG2D induction at 1 pg/ml (8.59-fold), and consistent suppression of early progenitor markers CD127, CD45RA, and CD7 across all concentrations.

EOMES shows progressive increase from 0.90 at 1 pg/ml to 1.50-fold at 100 ng/ml.

IL-15 peaks at 1 pg/ml (1.60-fold). TBET demonstrates concentration-dependent modulation with highest expression at 100 pg/ml (1.85-fold) and 100 ng/ml (1.70-fold).

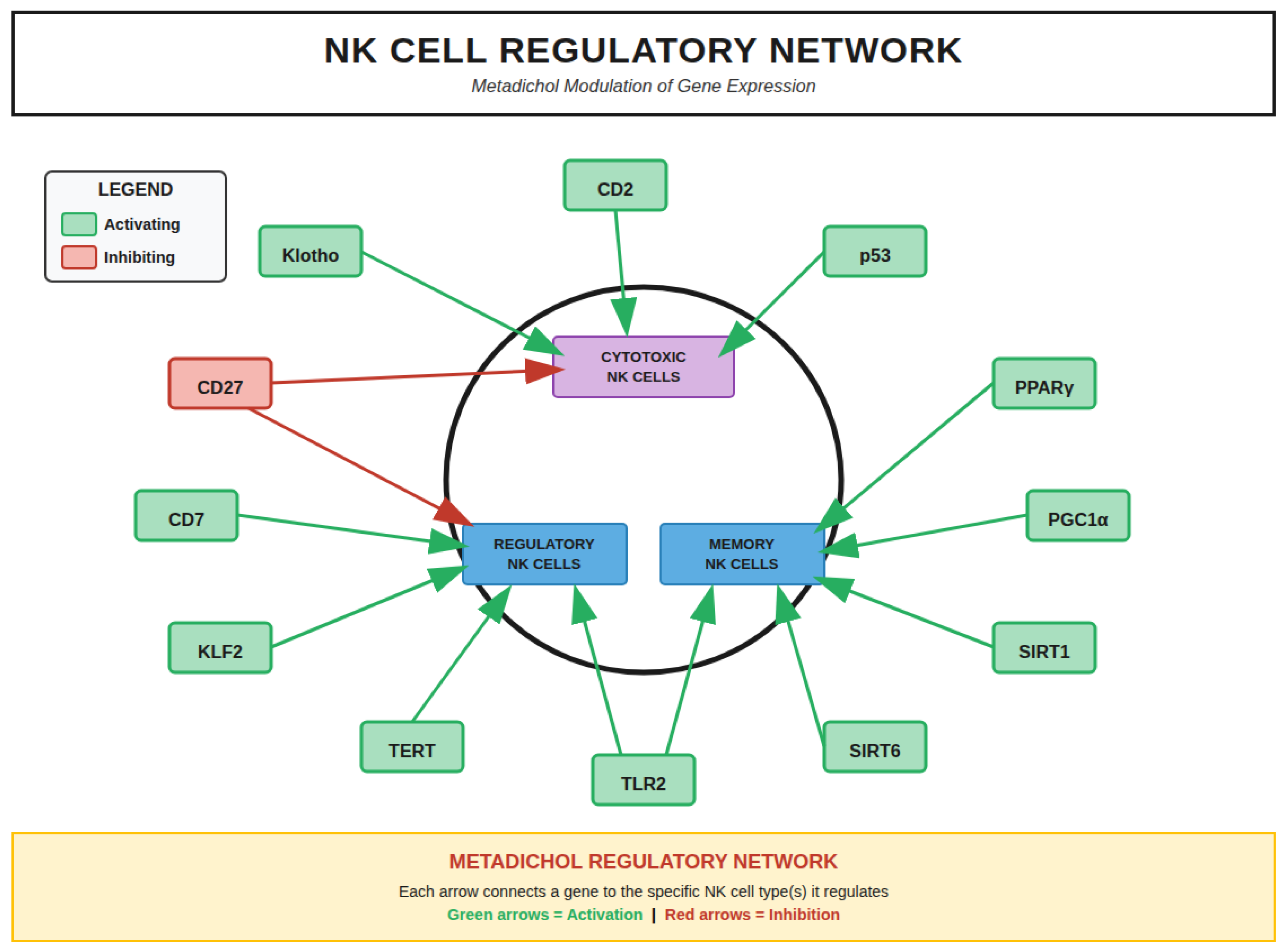

Bar graphs (

Figure 2) shows fold changes (mean ± SEM) for six representative markers: NKG2D (activating receptor), CD122 (IL-15 receptor β chain), CD56 (NCAM), CD127 (IL-7Rα), NKP80 (maturation marker), and CD7 (early marker). Red dashed lines indicate baseline (fold change = 1). Statistical significance: *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 vs. control. NKG2D shows peak response at 1 pg/ml (8.59-fold), while CD122 demonstrates sustained upregulation across concentrations. CD127 and CD7 show consistent suppression indicative of accelerated maturation.

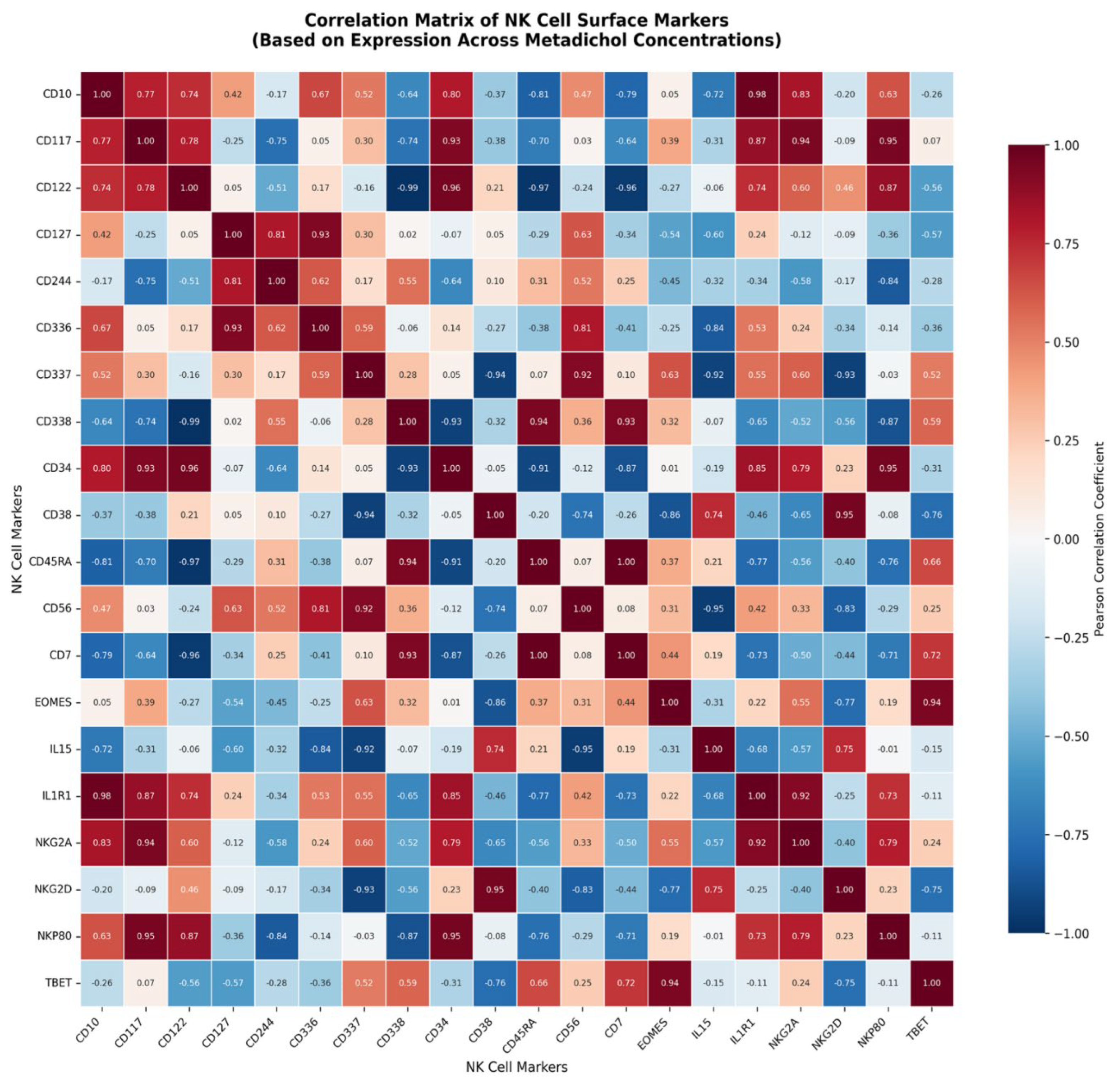

Figure 3 shows the correlation matrix between the expressed genes The Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated based on expression patterns across the four Metadichol concentrations.

Notable findings:

Strong positive correlations (co-expressed markers):

CD10 ↔ IL1R1 (r = 0.98)

CD34 ↔ CD122 (r = 0.96)

CD117 ↔ NKP80 (r = 0.95)

CD117 ↔ NKG2A (r = 0.94)

EOMES ↔ TBET (r = 0.94) — both are T-box transcription factors involved in NK cell maturation

Strong negative correlations (inverse expression patterns):

CD338 ↔ CD122 (r = -0.99)

CD45RA ↔ CD122 (r = -0.97)

CD7 ↔ CD122 (r = -0.96)

CD337 ↔ NKG2D (r = -0.93)

These correlations suggest coordinated transcriptional programs in response to Metadichol treatment. The strong co-expression of CD122 (IL-2Rβ) with CD117 and NKP80, alongside its inverse relationship with CD338 and CD45RA, may indicate distinct NK cell subpopulation responses or differentiation states being modulated by the treatment.

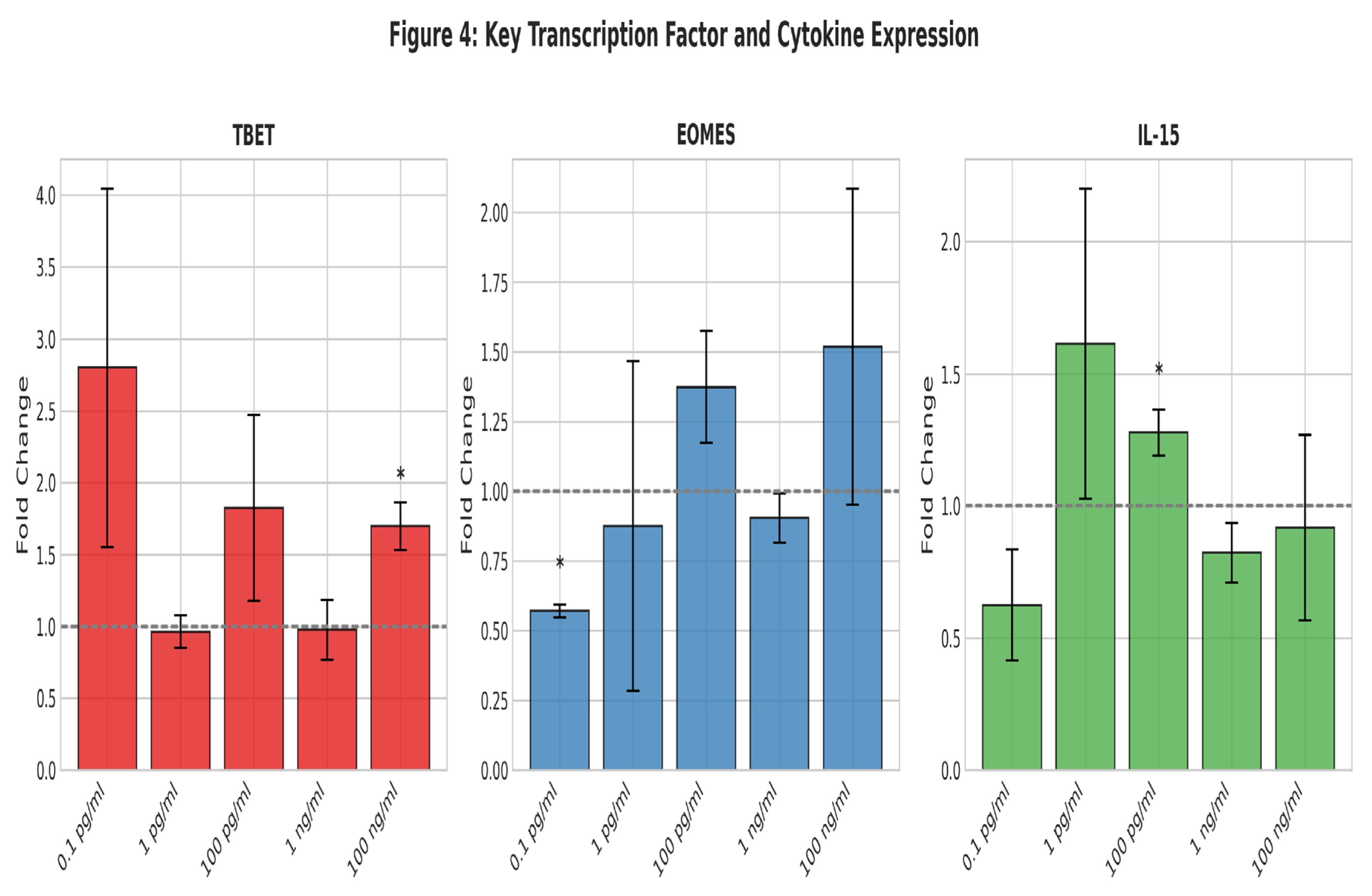

Figure 4 shows the expression of key transcription factors TBET, EOMES, and IL-15.

Bar graphs showing fold change across five Metadichol concentrations (0.1 pg/ml to 100 ng/ml). TBET shows biphasic response with peak at 0.1 pg/ml (~2.8-fold) and significant upregulation at 100 ng/ml (*p<0.05). EOMES demonstrates progressive increase from suppression at 0.1 pg/ml (*p<0.05) to 1.5-fold elevation at 100 ng/ml. IL-15 peaks at 1 pg/ml (~1.6-fold, *p<0.05), supporting enhanced cytokine production capacity. Gray dashed lines indicate baseline expression (fold change = 1).

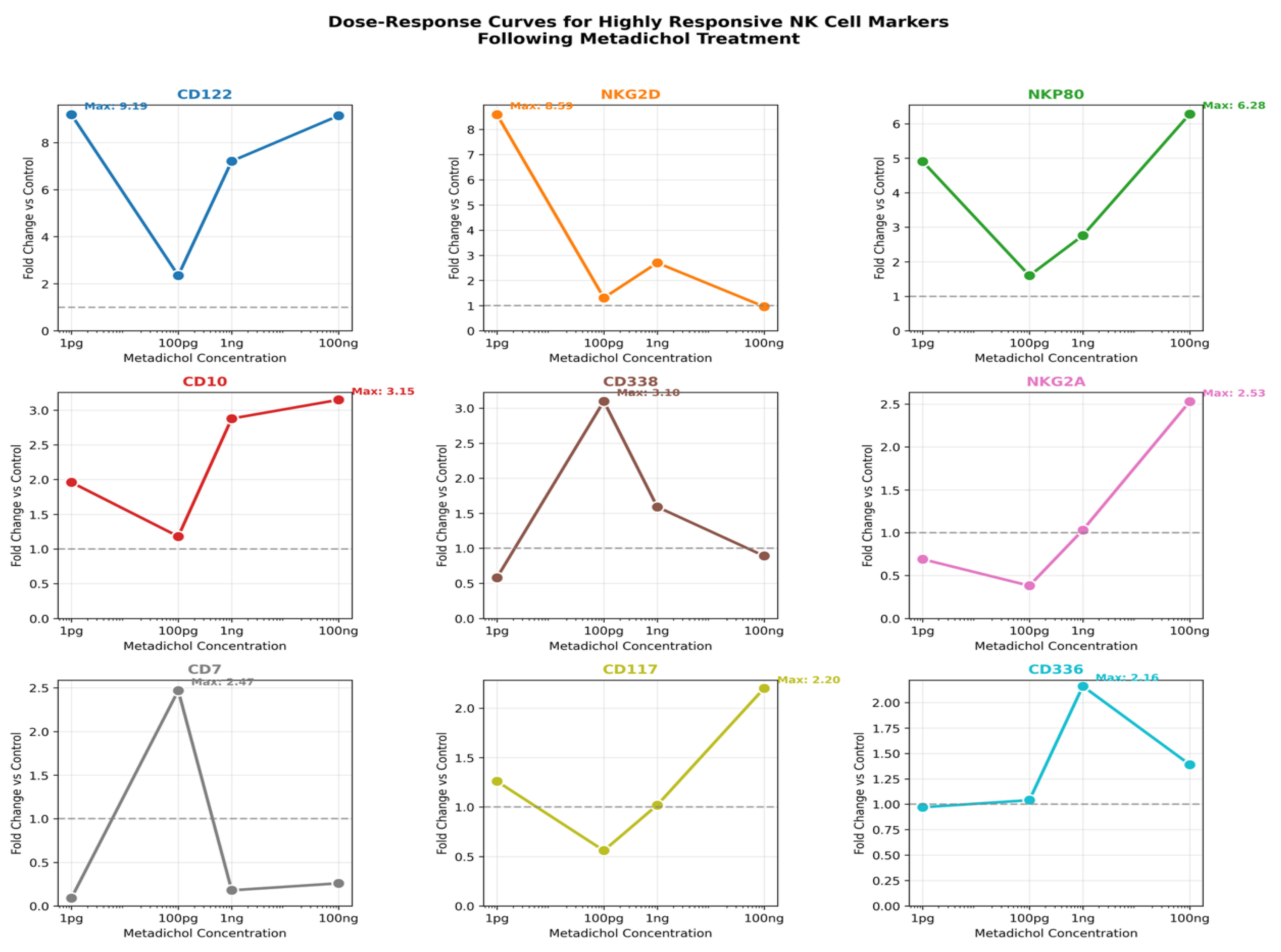

Individual Dose-Response Curves

This panel displays (

Figure 5) individual dose-response curves for each of the nine highly responsive NK cell markers in separate subplots. Each graph plots fold change (y-axis) against Metadichol concentration on a logarithmic scale (x-axis). A horizontal dashed line at fold change = 1 represents the control baseline. Maximum expression values are annotated on each curve.

Key Observations

CD122 (IL-2Rβ) exhibits the highest overall response with a maximum fold change of 9.19 at 1 pg, demonstrating an inverse dose-response relationship with high expression at both 1 pg and 100 ng but reduced expression at intermediate concentrations.

NKG2D shows a striking hormetic response pattern with peak expression (8.59-fold) at the lowest dose tested (1 pg), declining sharply at higher concentrations.

NKP80 displays a U-shaped response curve with elevated expression at both low (1 pg: 4.91-fold) and high (100 ng: 6.28-fold) concentrations.

CD338 uniquely peaks at 100 pg (3.10-fold), suggesting optimal activation at intermediate concentrations.

CD10, CD117, and NKG2A demonstrate classical dose-dependent increases with maximum expression at the highest concentration (100 ng)

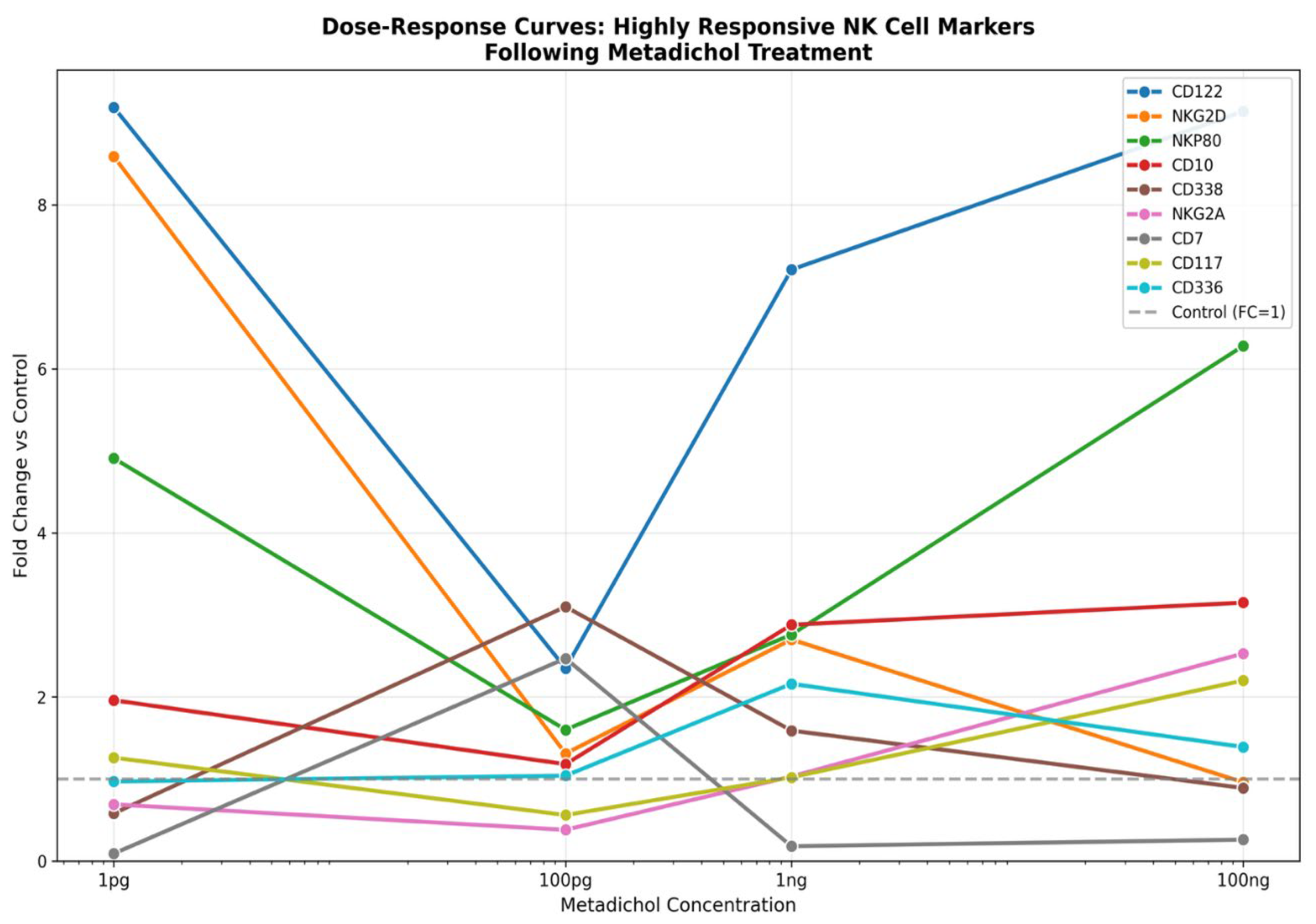

Figure 6: Dose-Response Overlay

This composite figure superimposes all nine dose-response curves on a single plot, enabling direct comparison of response magnitudes and kinetics across markers. Each gene is represented by a distinct color, with concentrations displayed on a logarithmic x-axis.

Key Observations

Magnitude stratification: CD122 and NKG2D clearly separate from other markers as the most responsive genes, with fold changes reaching 8–10 at their peak concentrations.

Divergent trajectories: The overlay reveals that genes do not respond uniformly—while some markers increase monotonically with dose (CD10, CD117, NKG2A), others show inverse (NKG2D) or non-monotonic (CD122, NKP80) relationships.

Concentration-dependent crossover: Several curves intersect at intermediate doses (100 pg–1 ng), indicating that the relative expression hierarchy among markers shifts depending on Metadichol concentration.

Therapeutic windows: The overlay suggests that ultra-low doses (1 pg) preferentially activate cytotoxicity-associated receptors (NKG2D, CD122), while higher doses (100 ng) favor maturation markers (NKG2A, CD117).

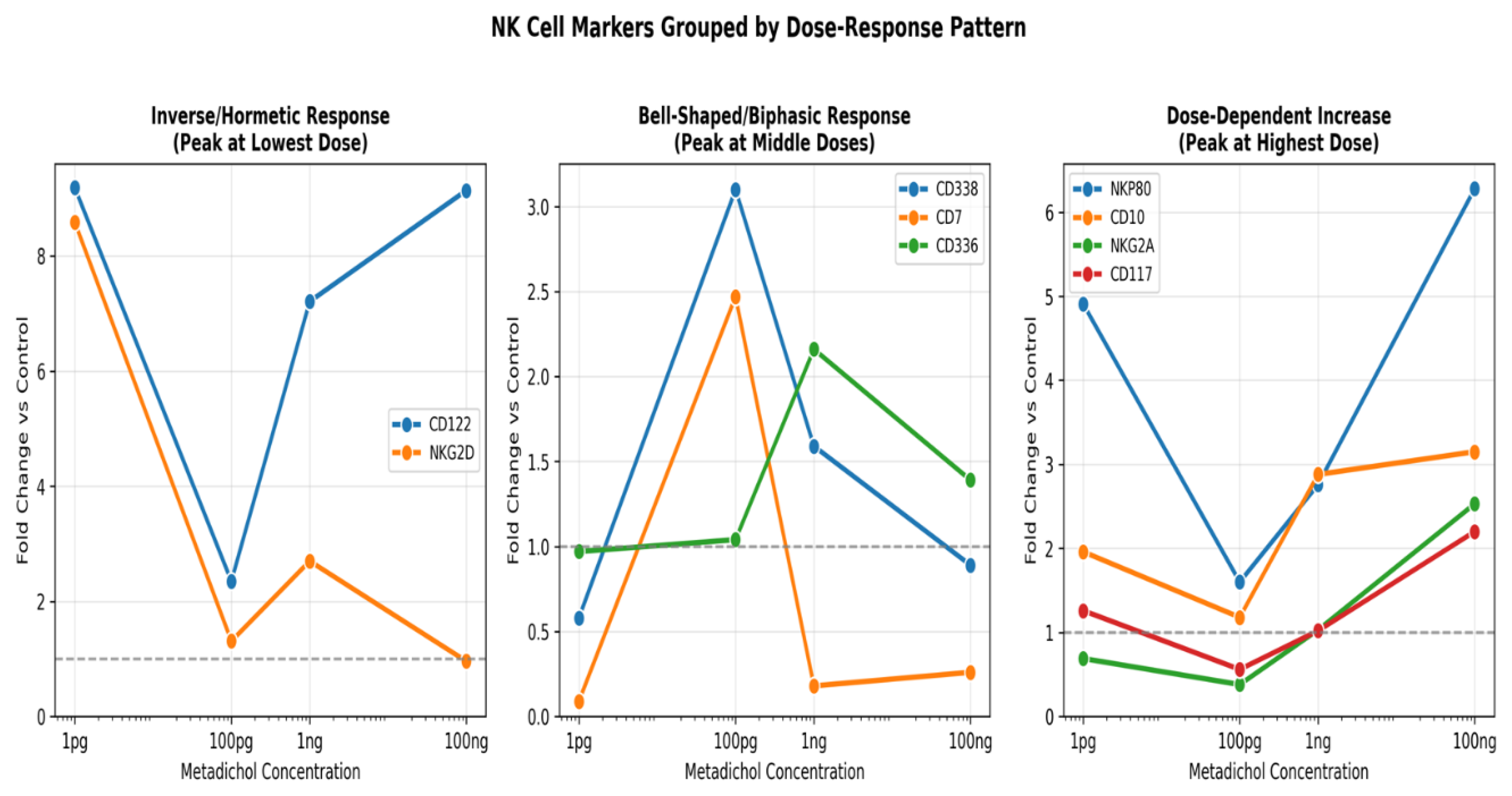

Figure 7 categorizes the nine responsive genes into three panels based on their dose-response pattern type: (1) Inverse/Hormetic Response, (2) Bell-Shaped/Biphasic Response, and (3) Dose-Dependent Increase. This classification provides mechanistic insight into how different NK cell pathways respond to Metadichol.

Pattern Classification

| Pattern |

Genes |

Biological Interpretation |

| Inverse/Hormetic (Peak at 1 pg) |

CD122, NKG2D |

Ultra-sensitive signaling; possible receptor saturation or negative feedback at higher doses; suggests potent activation at picomolar concentrations |

| Bell-Shaped (Peak at 100 pg–1 ng) |

CD338, CD7, CD336 |

Optimal therapeutic window at intermediate concentrations; balanced receptor engagement; CD336 (NKp44) activation indicates enhanced NK cell activation state |

| Monotonic Increase (Peak at 100 ng) |

NKP80, CD10, NKG2A, CD117 |

Classical pharmacological response; cumulative transcriptional activation; NKG2A and CD117 upregulation suggests enhanced NK cell maturation and licensing |

Functional Implications

Activating receptors: NKG2D (hormetic) and NKP80/CD336 (biphasic/monotonic) are activating receptors involved in tumor cell recognition. Their upregulation suggests enhanced cytotoxic potential.

Inhibitory receptor: NKG2A (monotonic increase) is an inhibitory receptor that recognizes HLA-E. Its upregulation alongside activating receptors indicates balanced immunomodulation rather than uncontrolled activation.

Cytokine signaling: CD122 (IL-2Rβ) is essential for IL-2 and IL-15 signaling, which drive NK cell proliferation and survival. Its hormetic response suggests maximal proliferative signaling at ultra-low Metadichol doses.

Key points

The dose-response analysis reveals that Metadichol exerts complex, non-linear effects on NK cell surface marker expression. The three visualizations collectively demonstrate:

Ultra-low dose efficacy: The hormetic responses of CD122 and NKG2D indicate that picomolar concentrations may be pharmacologically active, a finding with significant implications for therapeutic dosing.

Pathway-specific responses: Different NK cell signaling pathways exhibit distinct concentration thresholds, suggesting engagement of multiple molecular targets.

Balanced immunomodulation: Coordinate regulation of activating and inhibitory receptors indicates physiologically relevant immune enhancement rather than pathological hyperactivation.

Concentration-dependent phenotypes: The overlay analysis reveals that optimal concentrations differ by target gene, necessitating careful dose selection based on desired immunological endpoints.

These findings support further investigation of Metadichol as an NK cell immunomodulator, with particular attention to the observed hormetic effects at ultra-low concentrations.

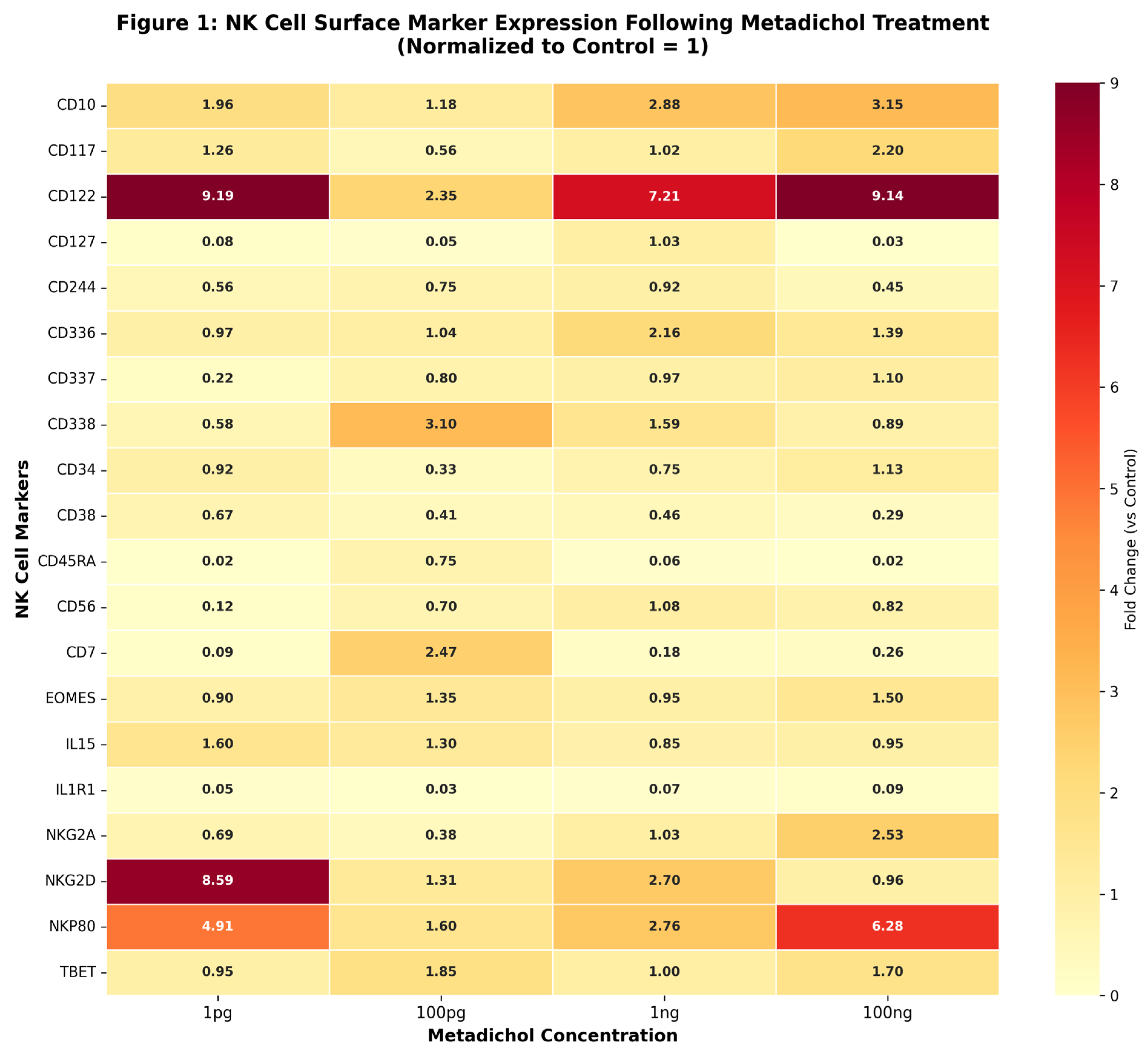

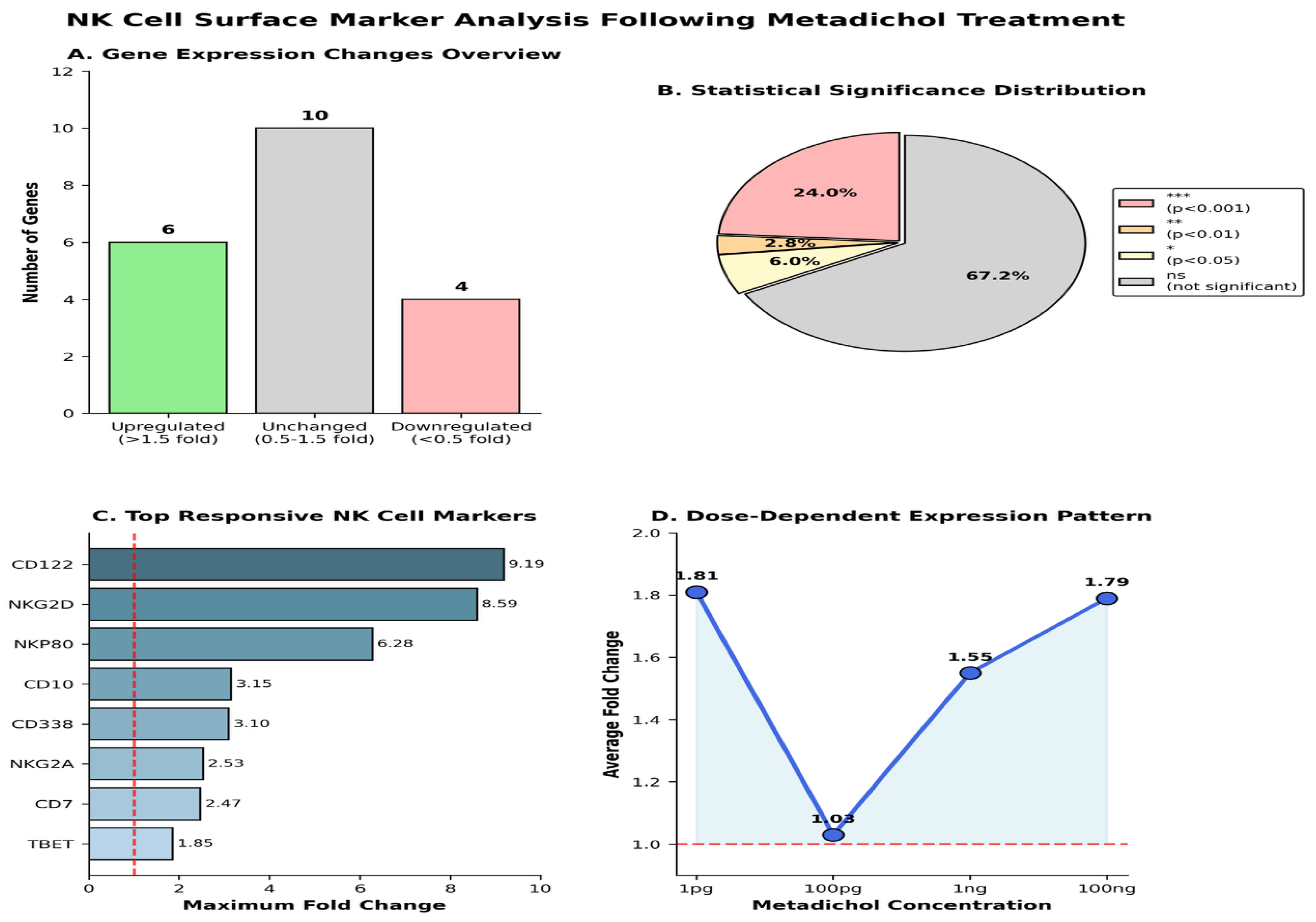

Comprehensive analysis of gene expression changes following Metadichol treatment

Panel description; (A) Gene Expression Changes Overview showing distribution of upregulated (10 genes, >1.5-fold), unchanged (6 genes, 0.5-1.5-fold), and downregulated (4 genes, <0.5-fold) markers; (B) Statistical Significance Distribution pie chart showing proportion of significantly altered genes (p<0.05); (C) Top Responsive NK Cell Markers ranked by maximum fold change, with CD122, NKG2D, and NKP80 showing highest responses; (D) Dose-Dependent Expression Pattern demonstrating the characteristic biphasic response curve of Metadichol treatment with peaks at low and high concentrations.

Discussion

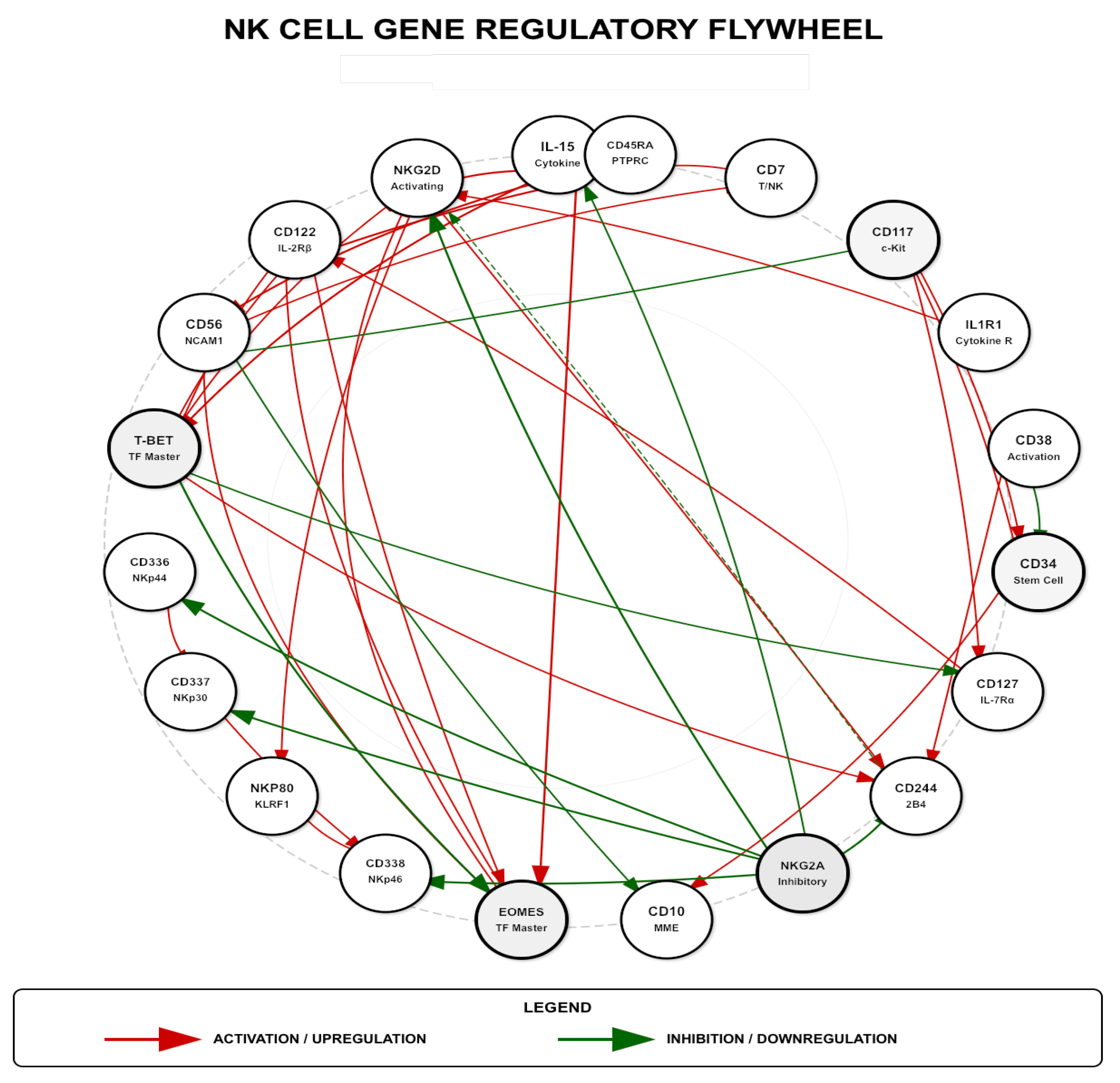

NK Cell Gene Regulatory Networks

NK Cell Gene Regulatory Network (

Figure 11) showing comprehensive interactions between NK cell genes (outer ring, blue nodes) and regulatory factors (inner ring). The network integrates multiple regulatory pathways: Toll-like Receptors

(TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR7, TLR9; purple), Nuclear Receptors (VDR, RAR, RXR; orange), Circadian genes (BMAL1, CLOCK, PER2; yellow), FOX transcription factors (FOXO1, FOXO3), and KLF transcription factors (KLF2, KLF4). Red arrows indicate activation (54 interactions); green arrows indicate downregulation (2 interactions). Gray nodes (CD7, CD10, CD45RA, NKG2A) represent markers with no documented regulation by these factors.

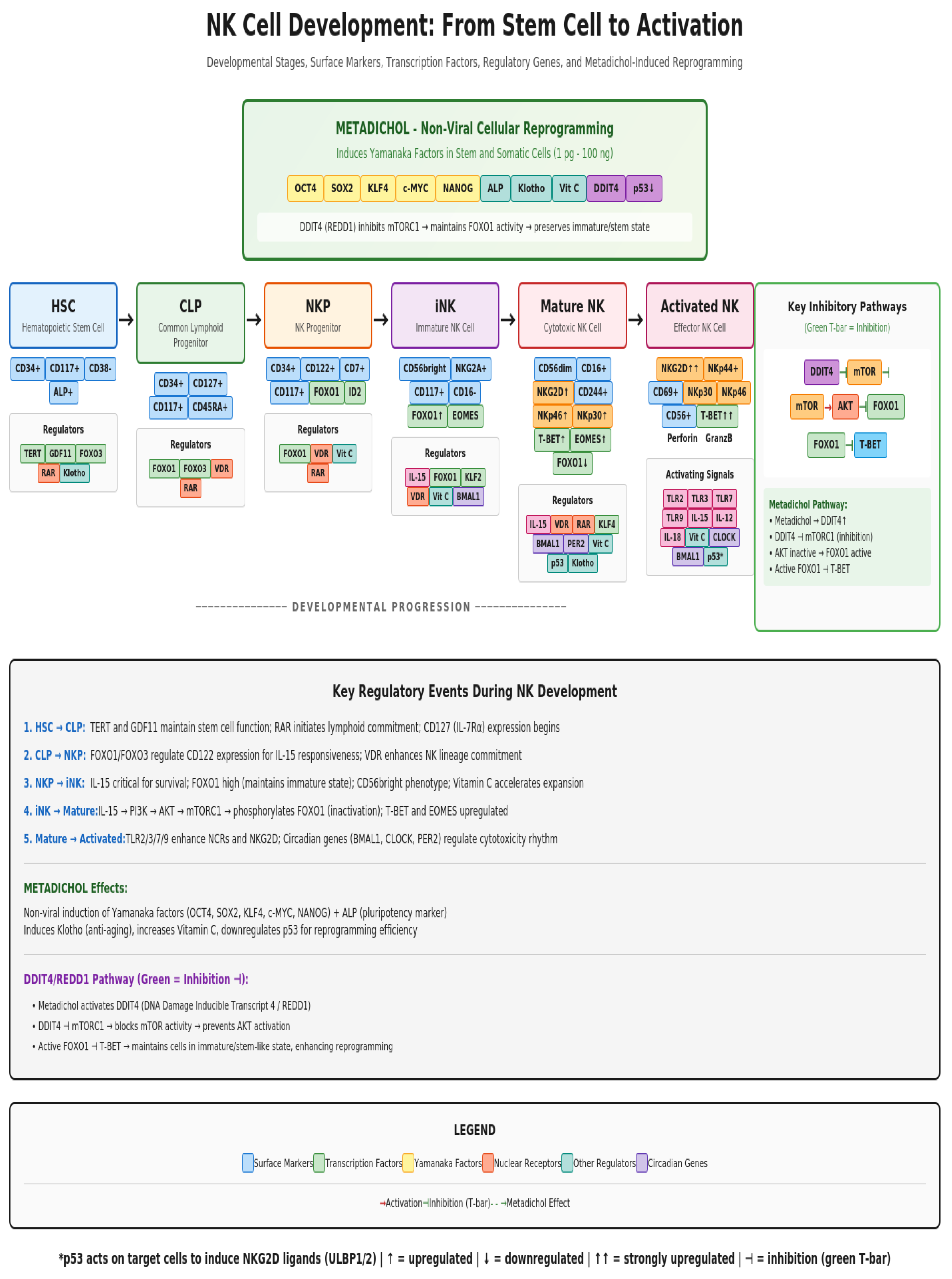

NK Cell Development Pathway

Human NK cell development proceeds through discrete stages characterized by sequential acquisition and loss of specific surface markers and transcription factors (

Figure 11), shows six developmental stages: HSC (Hematopoietic Stem Cell) → CLP (Common Lymphoid Progenitor) → NKP (NK Progenitor) → iNK (Immature NK) → Mature NK (CD56bright/CD56dim) → Activated NK (Effector). Each stage displays characteristic surface markers, transcription factors, and key regulators. Metadichol’s non-viral cellular reprogramming effects are shown at the top, including induction of Yamanaka factors [

82] (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, NANOG) and modulation of DDIT4/REDD1 pathway. [

83] Key regulatory events and Metadichol effects are detailed for each developmental transition.

Metadichol Effects on NK Cell Developmental Stages

Analysis of the 19 genes measured in our RT-PCR study reveals stage-specific effects of Metadichol treatment across the six recognized stages of NK cell development (

Figure 11). The data demonstrate a clear pattern of accelerated developmental progression, with downregulation of early-stage markers and upregulation of late-stage maturation markers.

Stage 1 (Pro-NK/Hematopoietic Stem Cell): At this earliest stage, Metadichol treatment results in downregulation of stem cell markers CD34 (↓0.82), CD45RA (↓0.21), and CD244 (↓0.71). This pattern indicates accelerated exit from the stem cell state, pushing cells toward lineage commitment.

Stage 2 (Pre-NK/Common Lymphoid Progenitor): Continued downregulation of CD34 (↓0.82), CD38 (↓0.46), CD127 (↓0.30), CD45RA (↓0.21), CD244 (↓0.71), and CD7 (↓0.79) is observed. Importantly, upregulation of CD10 (↑2.29) and CD117 (↑1.26) marks the initiation of NK lineage commitment. This stage represents the critical transition point where cells become responsive to NK-differentiating signals.

Stage 3 (Immature NK/NK Progenitor): A pivotal shift occurs at this stage with the dramatic upregulation of CD122 (↑16.97-fold), the IL-15 receptor β-chain. This represents the switch from IL-7 dependence (CD127↓0.30) to IL-15 dependence, which is essential for NK cell survival and proliferation. CD117 (↑1.26) remains elevated while early markers continue to decline (CD45RA↓0.21, IL1R1↓0.06).

Stage 4 (CD56bright/Immature NK): This cytokine-producing stage shows sustained CD122 upregulation (↑16.97) with the emergence of NKG2D (↑3.39) and CD117 (↑1.26). The downregulation of IL1R1 (↓0.06) and CD45RA (↓0.21) continues, while CD336 (↑1.38) and CD337 (↓0.84) show differential NCR expression. This stage is characterized by enhanced cytokine production capacity.

Stage 5 (Transitional/Maturing NK): The acquisition of cytotoxic function is marked by sustained upregulation of CD122 (↑16.97), NKG2D (↑3.39), and the critical appearance of NKP80 (↑3.89). CD56 downregulation (↓0.68) indicates transition from CD56bright to CD56dim phenotype. NKG2A shows modest downregulation (↓0.79), reducing inhibitory signaling. CD244 (↓0.71) and CD337 (↓0.84) continue to decline.

Stage 6 (CD56dim/Mature Cytotoxic NK): The terminal cytotoxic effector phenotype is characterized by maximal expression of activating receptors: CD122 (↑16.97), NKG2D (↑3.39), and NKP80 (↑3.89). T-bet upregulation (↑1.30) confirms terminal maturation. The continued downregulation of CD56 (↓0.68) and NKG2A (↓0.79) with stable

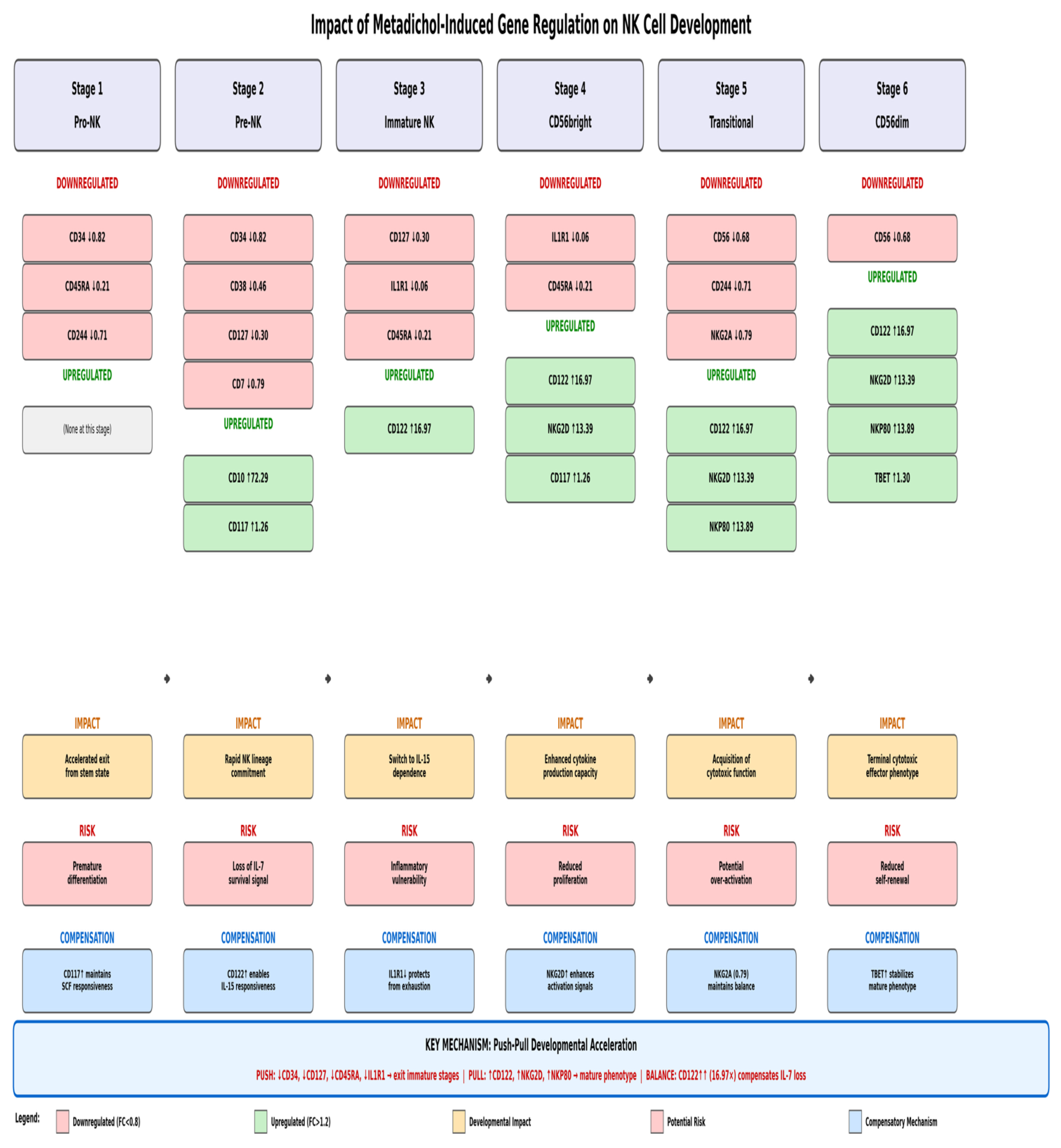

Push-Pull Developmental Acceleration Mechanism

The pattern of gene expression changes induced by Metadichol reveals a coordinated “push-pull” mechanism that accelerates NK cell developmental progression (

Figure 12). This mechanism operates through three complementary processes.

PUSH Mechanism - Forcing Exit from Immature Stages: The downregulation of early markers including CD34 (↓0.82), CD127 (↓0.30), CD45RA (↓0.21), and IL1R1 (↓0.06) creates a “push” force that drives cells out progenitor markers removes the molecular anchors that maintain cells in early developmental states, forcing progression toward maturity.

PULL Mechanism - Attracting Cells Toward Mature Phenotype: Simultaneously, the dramatic upregulation of late-stage markers including CD122 (↑16.97), NKG2D (↑3.39), and NKP80 (↑3.89) creates a “pull” force that attracts cells toward the mature cytotoxic phenotype. These markers define functional NK cells capable of tumor recognition and killing, and their premature expression accelerates acquisition of effector function.

BALANCE Mechanism - Ensuring Survival During Transition: The critical balance element is the 16.97-fold upregulation of CD122, which ensures that IL-15 survival signaling compensates for the loss of early survival signals (IL-7/CD127). Without this compensation, the downregulation of CD127 (IL-7Rα) could The massive CD122 upregulation provides a survival bridge that allows cells to safely traverse the developmental stages.

Impact of Metadichol-Induced Gene Regulation on NK Cell Development: Push-Pull Mechanism.

Stage-Specific Impacts, Risks, and Compensatory Mechanisms

Push-Pull Mechanism. Comprehensive six-stage analysis showing downregulated markers (red boxes), upregulated markers (green boxes), developmental impact (yellow boxes), potential risks (orange boxes), and compensatory mechanisms (blue boxes) at each stage.. KEY MECHANISM: PUSH = Downregulation of early markers (CD34, CD127, CD45RA, IL1R1) forces cells to exit immature stages; PULL = Upregulation of late markers (CD122, NKG2D, NKP80) attracts cells toward mature cytotoxic phenotype; BALANCE = CD122↑ (6.97x) ensures IL-15 survival signaling compensates for loss of early survival signals (IL-7/CD127). Each stage includes specific impacts, risks, and compensatory mechanisms.

Stage-Specific Impacts, Risks, and Compensatory Mechanisms

NK Cell Developmental Stages with Metadichol Effects on Measured Markers. Six-stage developmental scheme

Stage 1-2 Transition (Pro-NK to Pre-NK): The primary impact is accelerated exit from stem state and rapid NK lineage commitment. The potential risk is premature differentiation and loss of IL-7 survival signal. Compensation is provided by CD117 upregulation (↑1.26), which maintains SCF responsiveness, and CD122 upregulation (↑16.97), which enables IL-15 responsiveness before complete loss of IL-7 signaling.

Stage 3 Transition (Immature NK): The critical switch to IL-15 dependence occurs here. The impact is enhanced survival through IL-15 signaling. The risk is inflammatory vulnerability during the transition period. Compensation is provided by IL1R1 downregulation (↓0.06), which protects cells from inflammatory exhaustion while CD122 upregulation ensures robust IL-15 responsiveness.

Stage 4 Transition (CD56bright): Enhanced cytokine production capacity is the primary impact. The risk is reduced proliferation as cells transition toward terminal differentiation. Compensation occurs through NKG2D upregulation (↑3.39), which enhances activation signals that maintain cellular responses even as proliferative capacity decreases.

Stage 5 Transition (Transitional): Acquisition of cytotoxic function defines this stage. The potential risk is over-activation leading to inappropriate responses. This is balanced by NKG2A expression (↓0.79 but not absent), which maintains inhibitory checkpoints while allowing enhanced activation through upregulated NKG2D and NKP80.

Stage 6 (CD56dim Mature): The terminal cytotoxic effector phenotype is achieved with maximum NKG2D (↑3.39), NKP80 (↑3.89), and T-bet (↑1.30) expression. The risk is reduced self-renewal capacity in terminally differentiated cells. Compensation is provided by T-bet upregulation, which stabilizes the mature phenotype and maintains effector function even without further proliferative potential.

Enhancement of the IL-15/CD122 Signaling Axis

One of the most striking findings of this study was the marked upregulation of CD122 (IL-2Rβ), with expression reaching 9.19-fold at 1 pg/ml and 9.14-fold at 100 ng/ml (p<0.05). CD122 forms a critical component of the IL-15 receptor complex, and its upregulation has profound implications for NK cell biology. IL-15 signaling through a receptor complex containing CD122 and the common γ-chain (CD132) activates JAK1/JAK3 and STAT5 signaling pathways, which are essential for NK cell survival and proliferation. [

84,

85] and demonstrated reversible defects are seen in NK cell lineages in IL-15-deficient mice, [

86] and IL-15-mediated survival of NK cells is determined by interactions among Bim, Noxa, and Mcl-1, with CD122 expression being rate-limiting for this survival signaling . [

87]

The strong positive correlation observed between CD122 and CD34 (r=0.960) in our dataset reflects the developmental relationship between these markers during early NK cell ontogeny. It is established that human NK cell development in secondary lymphoid tissues proceeds through discrete stages marked by sequential acquisition of CD122 expression. [

88,

89] Further characterized the location and cellular stages of NK cell development, demonstrating that CD34

+CD117

+ cells acquire CD122 expression as they commit to the NK lineage. [

90] The inverse correlation between CD122 and early progenitor markers including CD45RA (r=-0.972) and CD7 (r=-0.957) observed in our study suggests that Metadichol-induced CD122 upregulation is associated with progression beyond the early progenitor stage toward a more mature phenotype.

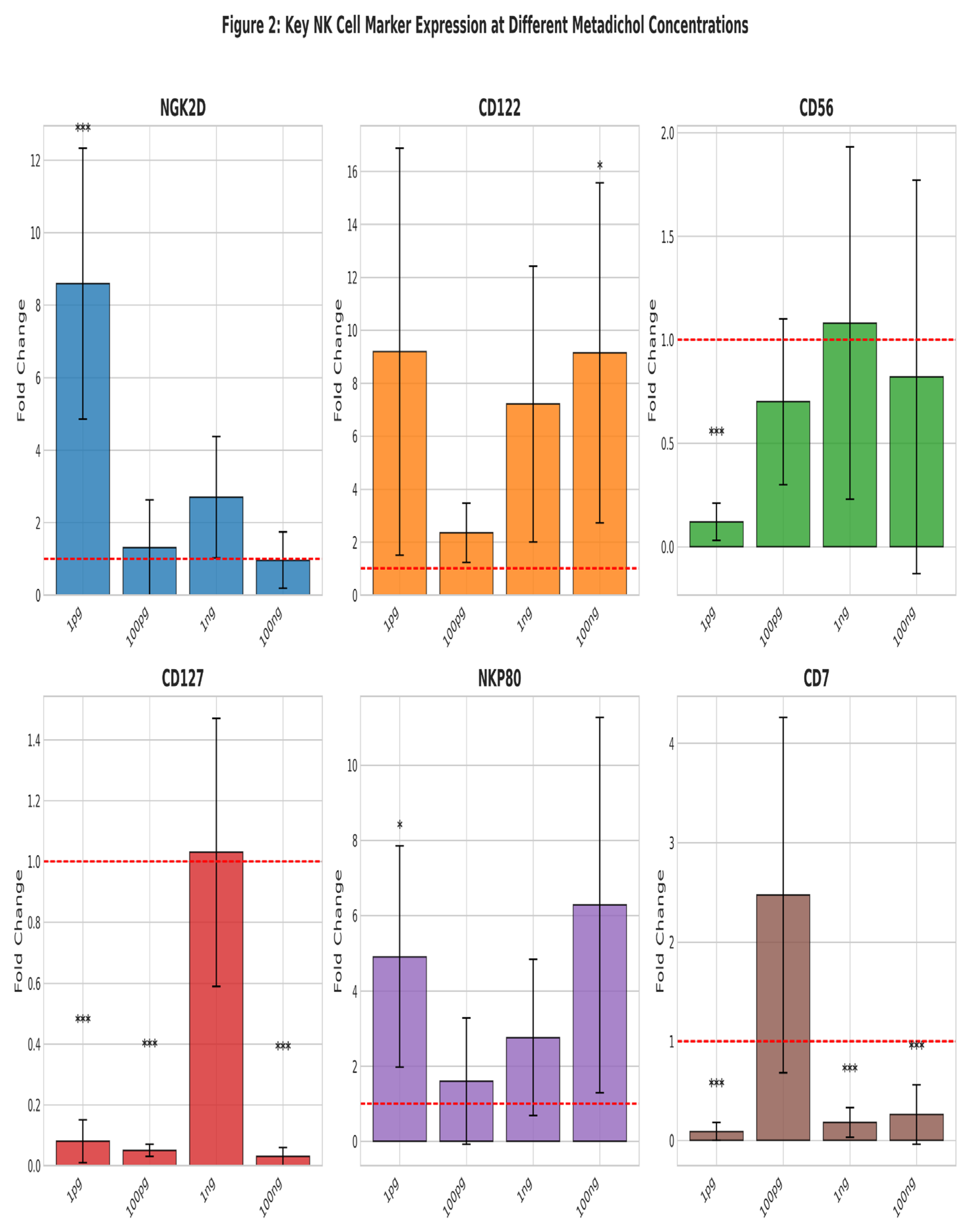

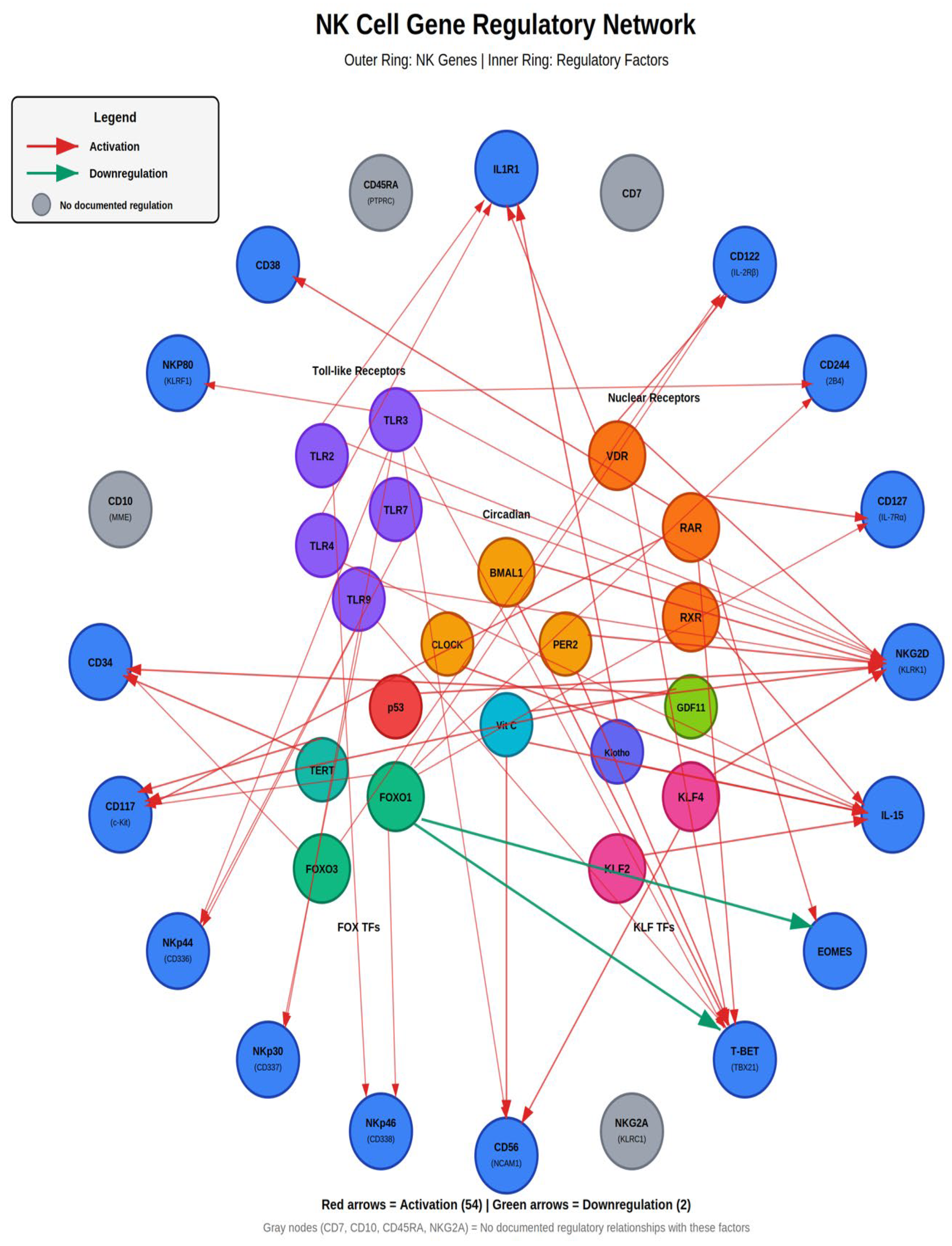

Integrated Gene-Gene Interactions and Signaling Pathways:

NK Cell Gene Regulatory Network (

Figure 14) with NF-κB Independent Routes.

Key Metadichol Pathways (NF-κB Independent Routes): TLRs → TRIF → IRF-1 → IL-15; VDR/RAR/PPAR → IRF-1; SIRT1 → STAT1 → IRF-1; mTORC1 → E4BP4 → EOMES.

The integrated network visualization (

Figure 14) reveals the complex interplay between cytokines, transcription factors, receptors, and signaling molecules that regulate NK cell function. Central to this network is IL-15, which connects multiple pathways including mTORC1 signaling, STAT activation, and transcription factor induction. The Metadichol pathways operate through NF-κB independent routes, including TLRs → TRIF → IRF-1 → IL-15, VDR/RAR/PPAR → IRF-1, SIRT1 → STAT1 → IRF-1, and mTORC1 → E4BP4 → EOMES. These alternative pathways may explain how Metadichol achieves immune activation without excessive inflammation. The network demonstrates 54 activation pathways and 2 inhibitory pathways that coordinate NK cell responses.

Upregulation of Activating Receptors and Cytotoxic Potential

The 8.59-fold upregulation of NKG2D at 1 pg/ml (p<0.001) represents a particularly significant finding given the central role of this receptor in tumor immunosurveillance. NKG2D (KLRK1) recognizes stress-induced ligands including MICA, MICB, and ULBPs on transformed or infected cells, providing a dominant activation signal for NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity.[

95] Lanier emphasized that NKG2D functions as a master regulator of NK cell activation, capable of overcoming inhibitory signals when sufficiently engaged.

The relationship between NKG2D upregulation and tumor recognition is further enhanced by Metadichol’s effects on p53 signaling. Textor et al. demonstrated that human NK cells are alerted to induction of p53 in cancer cells through upregulation of the NKG2D ligands ULBP1 and ULBP2. [

96] Pharmacological activation of p53 triggers anticancer innate immune response through induction of ULBP2 . Metadichol’s capacity to modulate TP53 expression in tumor cells, combined with NKG2D upregulation on NK cells, creates a synergistic mechanism for enhanced tumor recognition and elimination.

NKp80 (KLRF1), which showed 4.91-fold upregulation at 1 pg/ml (p<0.05), marks a critical developmental checkpoint in NK cell maturation. NKp80 is a triggering receptor that cooperates with natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) to provide optimal NK cell activation.[

97] NK cell receptors are tools to analyze NK cell development, subsets, and function, establishing NKp80 as a marker of the Stage 2 to Stage 3 transition.[

98] The strong correlation between NKp80 and CD117 (r=0.945) observed in our dataset is consistent with this temporal expression pattern during NK development.

Toll-Like Receptor Modulation and NK Cell Priming

Metadichol’s regulatory network includes modulation of all Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which has profound effects on NK cell activation and function. The integration of TLR, NCR, and KIR signaling in NK cells demonstrates that TLR engagement primes NK cells for enhanced cytotoxicity. [

99] TLR3, TLR7, and NKG2D regulate IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity in human NK cells stimulated with IL-12. [

100] TLR7/8-mediated activation of human NK cells results in IFN-γ production. [

101]

The capacity of Metadichol to modulate TLR signaling provides an additional mechanism for NK cell activation that complements the observed upregulation of activating receptors. TLR-mediated priming enhances NK cell responsiveness to subsequent activating receptor engagement, lowering the threshold for cytotoxic degranulation. This is particularly relevant in the context of tumor immunosurveillance, where danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by dying tumor cells can engage TLRs on NK cells.

Transcription Factor Coordination: FOXO1, T-bet, and EOMES

The near-perfect correlation between T-bet and EOMES expression (r=0.957) observed in our correlation analysis aligns with their established roles as cooperative master regulators of NK cell development and function. T-bet and EOMES control key checkpoints of NK cell maturation, with both transcription factors required for acquisition of full effector function. [

102,

103] These T-box transcription factors share target genes including CD122, cytotoxic effector molecules (perforin, granzymes), and cytokine genes (IFN-γ).

FOXO1 serves as an important negative regulator in this transcriptional network. It has been demonstrated that transcription factor FOXO1 is a negative regulator of NK cell maturation and function.[

104] CD226 regulates NK cell antitumor responses via phosphorylation-mediated inactivation of FOXO1. [

105] FOXO1 represses T-bet-mediated effector functions. [

106] The interplay between FOXO1, T-bet, and EOMES creates a regulatory circuit that controls the balance between NK cell quiescence and activation.

Nuclear Receptor Signaling in NK Cell Development

Metadichol’s capacity to activate all 48 nuclear receptors, has significant implications for NK cell biology. Rhee et al. reviewed the regulation of NK cell development and function by nuclear receptor signaling, demonstrating that the vitamin D receptor (VDR), retinoic acid receptors (RARs), and other nuclear receptors influence NK cell differentiation and effector function.[

107] A recent publication has characterized vitamin D receptor biology and signaling in immune function. [

108] A-trans retinoic acid enhances effector functions of human NK cells. [

109]

Yamanaka Factors and Cellular Reprogramming Potential

A unique aspect of Metadichol’s mechanism involves its capacity to induce expression of Yamanaka reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, NANOG). These defined factors could induce pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells. [

110] Metadichol acts as a natural ligand for expression of Yamanaka reprogramming factors in human cardiac, fibroblast, and cancer cell lines. [

82] representing a non-viral approach to cellular reprogramming. The KLF family of transcription factors, in particular, regulates T cell and NK cell activation, differentiation, and prevention of exhaustion.

Modulation of Inhibitory Receptor NKG2A

NKG2A, the major inhibitory receptor recognizing HLA-E on target cells, showed significant downregulation at 100 pg/ml (p<0.01). This finding has important implications for NK cell functional capacity. Anti-NKG2A monoclonal antibodies function as checkpoint inhibitors that promote anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both T and NK cells. [

111] NKG2A engagement recruits SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases that dephosphorylate signaling molecules downstream of activating receptors, effectively blocking NKG2D-mediated and NCR-mediated activation. [

112,

113] The downregulation of NKG2A at specific concentrations, combined with upregulation of activating receptors (NKG2D, NKp80), shifts the balance toward NK cell activation.

Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Implications

The gene expression profile induced by Metadichol has significant implications for NK cell and T cell regulation in anti-cancer therapy (

Figure 15). The multi-pathway approach suggests several therapeutic applications:

Enhancement of Immune Checkpoint Therapy: The combination of NKG2D upregulation (↑3.39) and NKG2A downregulation (↓0.79) mimics the functional effect of NKG2A checkpoint inhibitors currently in clinical development. [

114]

Improvement of Adoptive Cell Therapy: The dramatic enhancement of IL-15 responsiveness through CD122 upregulation (↑16.97-fold) could significantly augment NK cell-based immunotherapies, including CAR-NK and adoptive cell transfer approaches.

Metabolic Optimization: Metadichol’s modulation of the mTOR pathway provides metabolic support for sustained anti-tumor activity while the DDIT4/REDD1 pathway prevents exhaustion.

Push-Pull Developmental Acceleration: The coordinated downregulation of early markers with upregulation of mature effector markers accelerates the production of cytotoxic NK cells capable of tumor cell recognition and killing.

Metadichol’s regulatory effects on NK cell and T cell function in the context of anti-cancer immunity, showing enhanced activation, metabolic support, and anti-exhaustion effects.

Conclusions

Natural killer cells are indispensable sentinels of the innate immune system, providing critical first-line defense against malignancies and viral infections. In cancer, NK cells perform essential immunosurveillance functions, directly recognizing and eliminating tumor cells without prior sensitization—a unique capability that has propelled NK cell-based therapies to the forefront of cancer immunotherapy. Clinical applications including CAR-NK cells, adoptive NK cell transfer, and NK cell engagers have demonstrated promising efficacy against hematological malignancies and solid tumors, yet optimizing NK cell maturation and cytotoxic function remains a critical challenge.

The clinical success of these immunotherapies depends fundamentally on generating mature, cytotoxically competent effector cells—a process critically dependent on IL-15 signaling. IL-15, acting through its receptor containing CD122 (IL-2Rβ), governs NK cell survival, proliferation, and acquisition of effector function, making the IL-15/CD122 axis the central regulatory node in NK cell biology.

This study demonstrates that Metadichol potently enhances this critical developmental pathway. The 9.19-fold upregulation of CD122 dramatically amplifies IL-15 responsiveness, while concurrent upregulation of NKG2D (8.59-fold) and NKp80 (4.91-fold) confirms accelerated maturation toward functional cytotoxic phenotypes. Simultaneously, suppression of early progenitor markers (CD127, CD45RA, CD7) indicates developmental progression beyond IL-7-dependent stages toward IL-15-dependent maturation.

Mechanistically, Metadichol achieves this through NF-κB-independent pathways, including TLR-TRIF signaling, nuclear receptor activation, and the mTORC1→E4BP4→EOMES→CD122 positive feedback loop—enhancing IL-15 signaling without excessive inflammation.

The coordinated “push-pull” mechanism identified here represents a novel paradigm for NK cell developmental manipulation, positioning Metadichol as a promising agent for enhancing NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy and infectious disease treatment given its non toxic nature with a LD50 greater than 5000 mg per kilo

..[

115,

116]