1. Introduction

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization [

1], global aquaculture production has nearly tripled over the past two decades, increasing from 34 million tons in 1997 to approximately 82 million tons in 2020. Freshwater fish production currently accounts for about 62% of total global aquaculture output.

Among salmonids, the primary producers outside Asia are Norway and Chile, which together contribute approximately 2% of global production, mainly represented by Atlantic salmon [

Salmo salar (Linnaeus, 1758)]. However, global rainbow trout production reached 940,000 tons in 2019 [

1]. As reported by D’Agaro et al. [

2], the largest producers of rainbow trout are Norway, Chile, and Turkey. Today, rainbow trout [

Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792)] represents one of the most important freshwater farmed salmonid species worldwide, accounting for approximately 97% of total trout production. Rainbow trout was also the dominant freshwater aquaculture species in the European Union in 2020 [

3] and, together with common carp (

Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758), constitutes the main freshwater aquaculture species in Bulgaria.

At the same time, plastic pollution has emerged as a major global environmental challenge. Nearly 300 million tons of plastic are produced annually, a substantial proportion of which eventually enters rivers, lakes, and marine ecosystems [

4]. Several authors consider plastic pollution to be a problem of similar magnitude to climate change [

5]. Under environmental conditions, plastics undergo physical, chemical, and biological degradation driven by erosion, temperature fluctuations, ultraviolet radiation, and microbial activity, resulting in the formation of secondary MPs, besides some primary particles originally produced already as MPs. MPs are commonly defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm [

6]. MPs enter aquatic environments through multiple pathways, including riverine transport [

7,

8], urban dust [

9], effluents from wastewater treatment plants [

10], agricultural practices such as the application of sewage sludge and the use of plastic mulch films [

11,

12], as well as atmospheric deposition [

13]. In aquaculture systems, most operational infrastructure, including cages, nets, pipes, hoses, and ropes, is manufactured from plastic materials. Consequently, aquaculture facilities themselves are considered potential sources of MP contamination [

14,

15]. In addition, fish feeds produced from processed marine organisms have been identified as another potential source for MP introduction into aquaculture systems [

16,

17].

Despite growing awareness, the majority of plastic pollution research has focused on marine environments. Blettler et al. [

18] reported that approximately 87% of plastic pollution studies address marine systems, whereas only 13% concern freshwater ecosystems. Although ingestion of plastics by fish was first documented in the early 1970s [

19,

20], information on MP contamination in freshwater fish tissues remains limited. Most available studies have focused on MP presence in the gastrointestinal tract [

21,

22,

23,

24], while data on MP accumulation in edible muscle tissue, particularly in farmed freshwater species, are still scarce [

25,

26]. Therefore, despite the relatively small sample size and single sampling event, the present pilot study aims to provide the first baseline data on the presence, abundance, particle size, shape, and polymer composition of MPs in the muscle tissue of farmed rainbow trout in Bulgaria. No toxicological endpoints were assessed in fish or humans; instead, the study focuses on documenting multiple MP occurrences in edible tissues and contributing to the understanding of contamination pathways in freshwater aquaculture systems. Furthermore, the current findings for rainbow trout were compared against existing published datasets derived from common carp [

27].

2. Materials and Methods

No animal ethics approval was required for the present study, as all fish specimens were purchased as food products. In August 2025, six adult rainbow trout individuals (mean weight 420 ± 25.5 g; mean total length 33 ± 3.5 cm) were obtained from a fresh fish retailer in the city of Plovdiv, Bulgaria, which receives daily deliveries from national freshwater aquaculture farms, mainly operating open pond systems. Information on feeding regimes was not available; therefore, farm-level or national-scale inferences could not be made.

Dissection, sample preparation, and analytical procedures followed the protocol described by Arnaudova et al. [

27]. Briefly, muscle tissue samples were collected and digested using a 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution combined with 15% hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) until complete degradation of organic material was achieved. MP particles were subsequently separated by density centrifugation using saturated sodium chloride (NaCl) or zinc chloride (ZnCl₂) solutions, depending on the expected polymer density. The supernatant was filtered through 0.8 μm metal-coated (Al or Au) membrane filters.

MP identification and characterization were performed as previously reported [

28]. An Agilent 8700 Laser Direct Infrared (LDIR) Chemical Imaging System (Agilent Technologies, USA) was used, with automated operation controlled by Agilent Clarity software (version 1.1.23). Particles were analysed in the mid-infrared spectral region. Filters were first imaged under visible light to localize particles, followed by infrared scanning at 1442 nm to detect residual organic matter. Point-based spectral measurements were obtained using a quantum cascade laser (975–1800 cm⁻¹), covering characteristic absorption bands of common polymer types. Acquired spectra were matched against a reference polymer library for chemical identification.

Particle size was classified into five categories following Cheng et al. [

29] with slight modifications: <50 μm, 51–100 μm, 101–300 μm, 301–1000 μm, and 1001–5000 μm. Quantification was expressed as the number of particles per sample and as estimated mass, calculated from particle area and polymer density. All analyses of each sample were performed in triplicate.

To minimize contamination, strict quality control procedures were applied throughout the study. All reagents and equipment were pre-filtered, procedural blanks were included, and samples were handled under a laminar flow hood while wearing natural fibre laboratory coats and nitrile gloves. Blank membrane filters were placed in five Petri dishes during analyses to monitor airborne contamination. All doors and windows were kept closed during laboratory procedures, following previously established recommendations [

30,

31].

Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate differences in MP abundance, polymer composition, and particle characteristics between rainbow trout and common carp, as well as to explore multivariate patterns in MP profiles. Common carp results included in the analyses to enable direct comparison with previously published data generated using the same sampling, extraction, and analytical protocols [

27]. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.1) and Python (version 3.11), and results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Differences in MP abundance between rainbow trout and common carp for individual polymer types were tested using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, as data did not meet the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. Mean values are presented with standard deviations. Interspecific differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. To explore multivariate patterns in polymer composition, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using individual fish as observations and polymer types as variables. Before PCA, MP abundance data were log-transformed using ln(x + 1) to reduce skewness and account for zero values, and subsequently standardized (z-score transformation) to ensure equal weighting of variables. PCA results were visualized using biplots, with points representing individual samples, arrows indicating variable loadings, and 95% confidence ellipses illustrating species-level dispersion. Size-class and shape distributions of MP particles were analysed using contingency tables. Differences in size distribution among polymer types, as well as differences in particle shape distribution across size classes, were tested using chi-square tests of independence. Categories containing only zero values were excluded from the analyses to meet test assumptions. The strength of associations was quantified using Cramér’s V as a measure of effect size. Graphical representations included 100% stacked bar charts to visualize the relative distribution of MP size classes across polymer types and the relative distribution of particle shapes across size classes.

3. Results

The type and average concentration of each MP polymer, as well as class range and shape, detected via LDIR in the muscle tissue of rainbow trout are presented in

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. MPs were found in every analysed individual, and a total of nine different polymer types were identified: polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyamide (PA), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), polyurethane (PU), rubber, and polyoxymethylene (POM), similarly to our previous findings in common carp [

27]. However, these polymers were not present in all samples. Moreover, in contrast to common carp [

27], polyvinyl chloride (PVC) was not detected in rainbow trout muscle.

Polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and rubber were detected in all six rainbow trout samples and thus represented the most frequently occurring polymer types. Nevertheless, these polymers were not always the most abundant. The highest single-sample concentration was recorded for polyamide (PA), reaching 211 particles/g in one individual. Rubber also occurred at relatively high levels in two samples (31 and 14 particles/g, respectively). Polyethylene (PE) was detected in two rainbow trout only, and in comparatively low quantities. Polyurethane (PU) was present in two samples, while polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyoxymethylene (POM) were only detected in a single fish each.

The interspecific comparison between rainbow trout and common carp revealed statistically significant differences for polyethylene (PE) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), with both polymers occurring at significantly higher concentrations in carp muscle (Kruskal–Wallis test: PE: Hc = 5.945, p = 0.0148; ABS: Hc = 6.545, p = 0.0105;

Table 1). In contrast, no significant differences were observed between species for polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyurethane (PU), rubber, or polyoxymethylene (POM) (p > 0.05 in all cases).

Overall, although rainbow trout exhibited lower MP concentrations for all polymer categories compared to carp, statistically supported interspecific differences were limited to polyethylene (PE) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS).

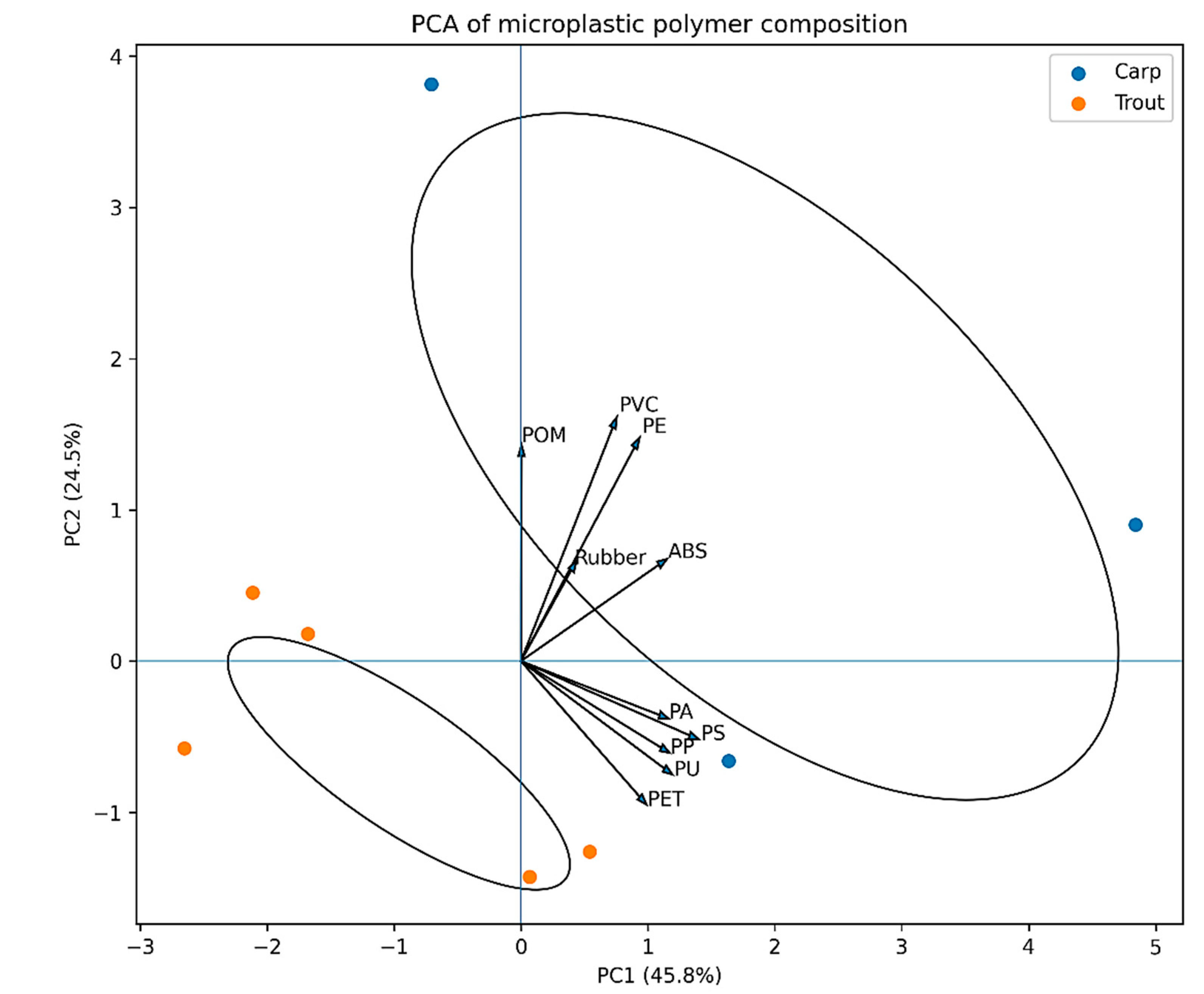

Principal component analysis (PCA) based on log-transformed and standardized MP abundance data revealed a clear multivariate separation between rainbow trout and common carp (

Figure 1). The first two principal components explained 45.8% (PC1) and 24.5% (PC2) of the total variance, respectively. The ordination was primarily driven by differences in polyethylene (PE), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and polyamide (PA), as indicated by their strong loadings along PC1. Rainbow trout samples showed higher variability along PC2, largely associated with polyamide (PA) and rubber, whereas common carp clustered towards higher PC1 scores, reflecting elevated contributions of polyethylene (PE) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS).

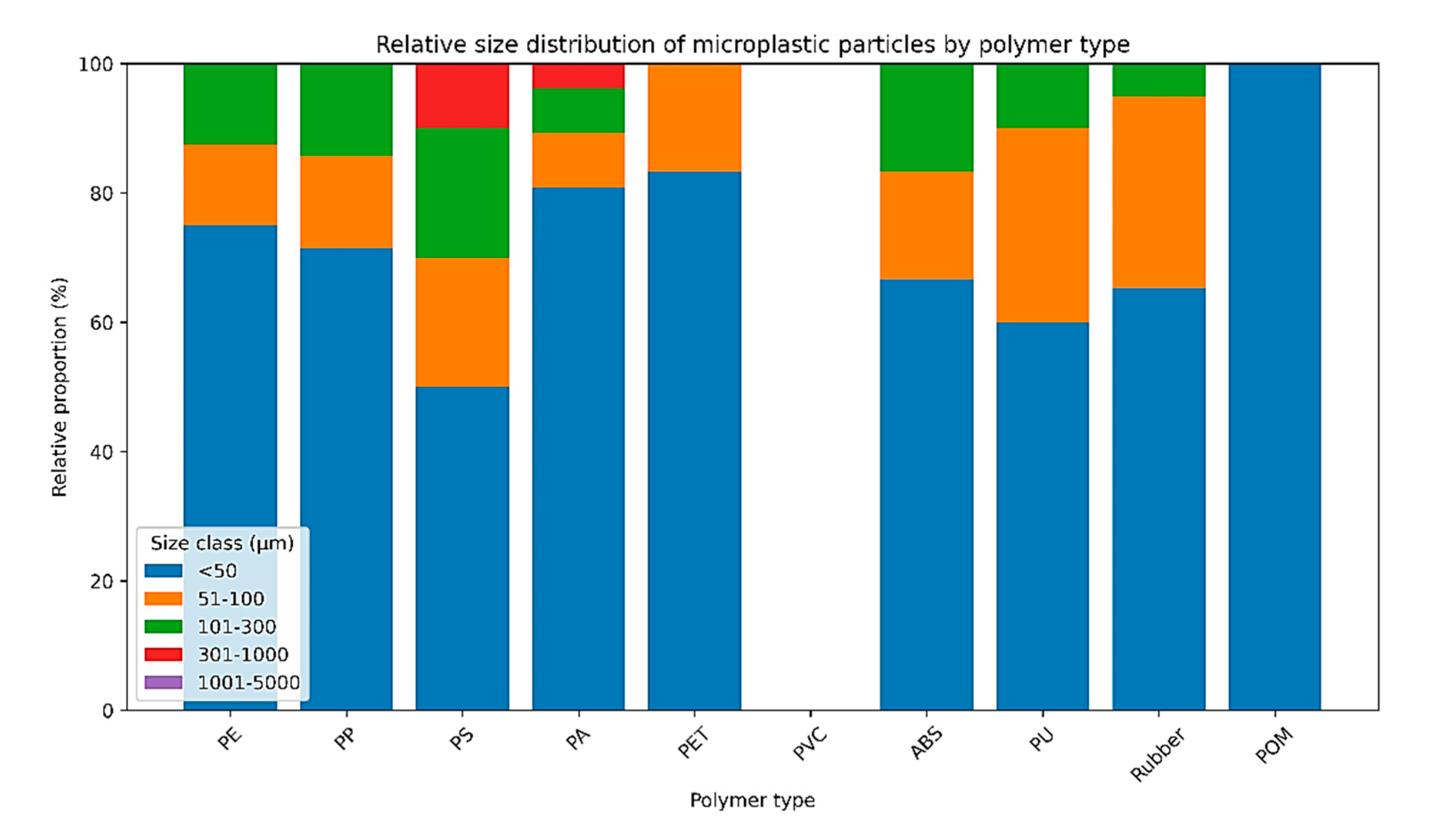

The size distribution of MP particles differed significantly among polymer types (χ² = 49.77, df = 24, p = 0.0015;

Figure 2). Overall, particles smaller than 50 μm dominated all polymer categories, accounting for the majority of detected MPs, followed by the 51–100 μm and 101–300 μm size classes. Polyamide (PA) and rubber exhibited the highest contributions across all size classes, together representing the largest proportion of total MP counts. In contrast, particles larger than 300 μm were rare and were detected only sporadically, while no particles exceeding 1000 μm were observed in any polymer category. The strength of association between polymer type and size class was moderate (Cramér’s V = 0.16).

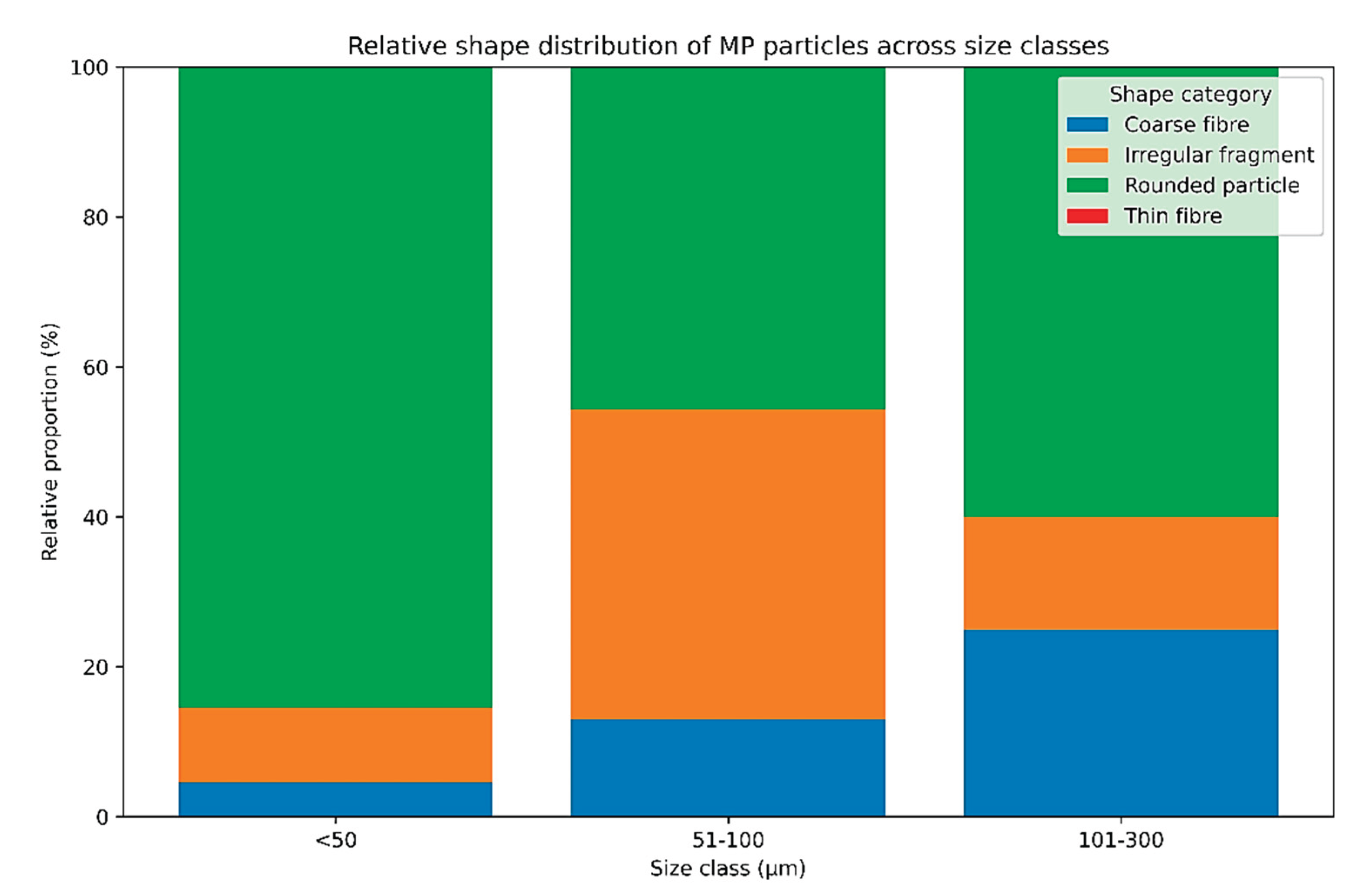

The shape distribution of MP particles differed significantly among size classes (χ² = 59.85, df = 4, p = 3.11 × 10⁻¹²;

Figure 3). Rounded particles dominated the <50 μm fraction, while the relative contribution of irregular fragments and coarse fibers increased with particle size. No thin fibers were detected, and particles exceeding 300 μm were absent from the dataset. The strength of association between particle shape and size class was moderate (Cramér’s V = 0.23).

4. Discussion

Although several polymer types were consistently detected across samples (e.g. polyethylene, PE; polystyrene, PS; acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, ABS; and rubber), polymer abundance varied considerably among individuals, indicating heterogeneous exposure conditions and/or inter-individual differences in feeding behavior, filtration efficiency of the gills, and gut transit time. Such variability has also been reported in other studies on MP ingestion in fish and likely reflects the patchy distribution of MPs in aquatic environments and the stochastic nature of ingestion and/or ventilation processes. Among all detected polymers, polyamide (PA) was the most abundant, reaching up to 211 particles/g in one individual and clearly exceeding all other polymer types. Polyamide (PA) is commonly associated with fishing gear, nets, aquaculture infrastructure, and textile fibers; therefore, its elevated presence may reflect direct release from aquaculture equipment or contamination in the incoming water supply. Similarly, rubber, which was detected at relatively high levels in several samples, may originate from abrasion of facility components, degraded rubber materials, or tire-derived particles transported into the system via surface runoff or water intake.

The application of LDIR chemical imaging enabled the reliable identification of a broad spectrum of polymer types with high chemical specificity, supporting the robustness of the present findings. Importantly, even polymers detected at relatively low absolute abundances (e.g., polyethylene terephthalate, PET; polyoxymethylene, POM) demonstrate that MPs are capable of infiltrating controlled aquaculture environments despite standardized feeding regimes, recirculation systems, or good farming practices. This highlights that aquaculture facilities are not isolated from surrounding plastic pollution pressures and may act as sinks for a wide range of polymer types.

Comparison with our previous study on common carp [

27] provides valuable insight into potential species-specific and size-related differences in MP accumulation. In general, common carp exhibited higher overall MP loads than rainbow trout, which is likely explained by their larger body size and longer lifespan, resulting in prolonged cumulative exposure. This supports the hypothesis that MP accumulation is strongly influenced by exposure time and fish biomass. However, polyamide (PA) showed the opposite pattern, being significantly more abundant in rainbow trout than in common carp. This finding suggests that polymer-specific exposure pathways may differ between species and farming systems and may be influenced by farm-specific materials, water flow conditions, or differences in feeding ecology. The overall similarity in polymer composition between the two studies further suggests consistent contamination sources at least at the national level, likely linked to commonly used plastics in Bulgarian freshwater aquaculture, such as feed packaging, hoses, filtration units, and netting materials. Nevertheless, it might be plausible to extrapolate our findings to several other regions worldwide and the potential risks generated for human consumption.

The multivariate PCA supported the univariate statistical results by revealing a clear separation between rainbow trout and common carp based on polymer composition, primarily driven by differences in polyethylene (PE), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and polyamide (PA). This indicates that MP contamination patterns are not only quantitatively but also qualitatively different between species, reflecting distinct exposure profiles. In addition, the size-distribution analysis showed that particles smaller than 50 μm dominated all polymer categories, while particles larger than 300 μm were rare. The strong predominance of small-sized MPs is consistent with fragmentation processes and is ecotoxicologically relevant, as smaller particles are more bioavailable through ingestion and ventilation and more likely to penetrate biological barriers.

The analysis of particle shape further demonstrated that rounded particles dominated the smallest size fraction, whereas irregular fragments and coarse fibers became more prevalent with increasing particle size. This pattern likely reflects mechanical degradation of plastic materials and progressive fragmentation in the aquatic environment. The absence of thin fibers may be related to either lower environmental availability or methodological limitations of LDIR detection for certain fiber morphologies. However, it is not excluded that internalization of fibers might be more difficult than a small particle with a regular shape, as well as expected for bigger irregular particles. Together, the significant associations between polymer type, size class, and particle shape indicate non-random structuring of MP characteristics in aquaculture systems and suggest that both physical and chemical properties influence MP fate and bioavailability.

From a broader perspective, research on MP ingestion in wild marine and freshwater species has increased substantially in recent years [

32], whereas studies focusing on farmed fish remain comparatively scarce. The present study provides the first documented evidence of MP contamination in farmed rainbow trout in Bulgaria and contributes to filling this important knowledge gap. The detection of nine distinct polymer types in edible muscle tissue demonstrates that MPs are capable of crossing biological barriers and accumulating in internal fish tissues, even under controlled farming conditions. The diversity of polymers, ranging from common packaging-related materials (polyethylene, PE, and polystyrene PS) to more specialized polymers (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, ABS), polyurethane, PU, rubber, and polyoxymethylene, POM), suggests multiple and complex contamination sources and pathways affecting aquaculture environments.

Rainbow trout is a predatory species that naturally feeds on aquatic invertebrates, mussels, crustaceans, and small fish [

33], which may facilitate the trophic transfer of MPs. From a food safety perspective, the presence of MPs in edible tissues is concerning, as rainbow trout is commonly consumed as whole fish or fillets. Fish represents an important source of high-quality protein and omega-3 fatty acids in the human diet [

34]. Therefore, the detection of MPs raises potential implications for consumer exposure and potential health risk. Most detected particles in the present study were smaller than 50 μm, a size range that may facilitate translocation across biological membranes and increase the likelihood of tissue retention. Small MPs are also more prone to interact with cellular structures, induce inflammatory responses, or act as vectors for plastic additives and adsorbed environmental contaminants [

35,

36].

Although the toxicological implications of dietary MP exposure for humans remain uncertain, MPs may serve as carriers for hazardous chemicals and microorganisms, and their presence in aquaculture products warrants precautionary consideration. Overall, the present results provide baseline data for Bulgaria and highlight the importance of monitoring MPs not only in wild freshwater species but also in farmed fish entering the commercial market worldwide. Improved management strategies, including the reduction of plastic use in aquaculture infrastructure and better control of water sources, may be necessary to mitigate MP contamination in fish farming systems.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable preliminary insights into MPs’ contamination in farmed rainbow trout, although it is limited by a relatively small sample size and single time-point sampling. Nevertheless, as a proof-of-concept investigation, it clearly demonstrates the presence of multiple MPs in the muscle tissue of farmed rainbow trout, representing a novel regional contribution to aquatic toxicology. Our findings confirm that freshwater aquaculture systems are vulnerable to MP contamination despite their controlled production conditions. Given that Bulgaria increasingly relies on freshwater aquaculture production, the implementation of targeted mitigation strategies—such as improving water filtration, reducing plastic use in farm infrastructure, and promoting better waste-management practices—may help to decrease MP exposure in cultured fish worldwide. However, as a pilot study, the present results should be interpreted as indicative rather than representative of the entire Bulgarian aquaculture sector. Therefore, broader multi-farm and multi-season investigations are required to assess spatial and temporal variability and to establish more robust prevalence estimates and risk assessments. Overall, continued monitoring across seasons, farming systems, and species is essential for developing a comprehensive understanding of MP contamination sources and pathways, and for supporting the development of effective national policies aimed at safeguarding both fish health and consumer safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Y., D.A.; methodology, V.Y., D.A. and K.N.; software, K.N.; validation, V.Y., C.G., K.N and L.A..; formal analysis, K.N.; investigation, V.Y., D.A., E.G., S.S., E.G., and I.E.U.; resources, V.Y., S.S., E.G.; data curation, V.Y, K.N., I.E.U. and L.A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.Y. and K.N.; writing—review and editing, V.Y, B.B., K.N. and C.G..; visualization, V.Y. and K.N.; supervision, V.Y..; project administration, V.Y.; funding acquisition, V.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No BG-RRP-2.004-0001-C01, DUECOS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

Project no. SP25BF001 (СП25-БФ-001) – Pilot study on the quantity and composition of microplastics in freshwater commercially important fish species (common carp, Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758, and brown trout, Salmo trutta fario Linnaeus, 1758) in Bulgaria (Department of Scientific Research of the University of Plovdiv). Project no. TKP2021-NKTA-32 was implemented with the support provided by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme. The research presented in the article was carried out within the framework of the Széchenyi Plan Plus program with the support of the RRF 2.3.1-21-2022-00008 project. Krisztián Nyeste and László Antal were supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO 2022. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Towards Blue Transformation. Available online: www.fao.org (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- D’Agaro, E.; Gibertoni, P.; Esposito, S. Recent trends and economic aspects in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) sector. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12(17), 8773. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178773.

- APROMAR 2022. Asociación Empresarial de Acuicultura en España. Aquaculture in Spain. Available online: https://apromar.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Aquaculture-in-Spain-2022_APROMAR.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Waters, C.N.; Ivar do Sul, J.A.; Corcoran, P.L.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cearreta, A.; Edgeworth, M.; Gałuszka, A.; Jeandel, C.; Leinfelder, R.; McNeill, J.R.; Steffen, W.; Summerhayes, C.; Wagreich, M.; Williams, M.; Wolfe, A.P.; Yonan, Y. The geological cycle of plastics and their use as a stratigraphic indicator of the Anthropocene. Anthropocene 2016, 13, 4–17.

- Galloway, T.; Lewis, C. Marine microplastics. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27(11), 445–446.

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.; Bamford, H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the occurrence, effects and fate of microplastic marine debris. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS-OR & R-30 2009, 7–17.

- Constant, M.; Ludwig, W.; Kerherve, P.; Sola, J.; Charriere, B.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Canals, M.; Heussner, S. Microplastic fluxes in a large and a small Mediterranean river catchments: the Tet and the Rhone, Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 136984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136984.

- Pojar, I.; Stanica, A.; Stock, F.; Kochleus, C.; Schultz, M.; Bradley, C. Sedimentary microplastic concentrations from the Romanian Danube River to the Black Sea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81724-4.

- Miloloža, M.; Kučić Grgić, D.; Bolanča, T.; Ukić, Š.; Cvetnić, M.; Bulatović, V.O.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Kušić, H. Ecotoxicological assessment of microplastics in freshwater sources—a review. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010056.

- Kang, H.J.; Park, H.J.; Kwon, O.K.; Lee, W.S.; Jeong, D.H.; Ju, B.K.; Kwon, J.H. Occurrence of microplastics in municipal sewage treatment plants: a review. Environ. Health Toxicol. 2018 33(3), e2018013. https://doi.org/10.5620/eht.e2018013.

- Nizzetto, L.; Futter, M.; Langaas, S. Are agricultural soils dumps for microplastics of urban origin? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10777–11077. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b04140.

- Prokić, M.D.; Radovanović, T.B.; Gavrić, J.P.; Faggio, C. Ecotoxicological effects of microplastics: examination of biomarkers, current state and future perspectives. TrAC-Trend. Anal. Chem. 2019, 111, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2018.12.001.

- Ding, Y.C.; Zou, X.Q.; Wang, C.L.; Feng, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.Y.; Chen, H.Y. The abundance and characteristics of atmospheric microplastic deposition in the northwestern South China Sea in the fall. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 253, 118389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118389.

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Tan, S.; Kang, Z.; Yu, X.; Lan, W.; Cai, L.; Wang, J.; Shi, H. Microplastic pollution in the Maowei Sea, a typical mariculture bay of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.192.

- Wu, F.; Wang, Y.; Leung, J.Y.; Huang, W.; Zeng, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, A.; Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, L. Accumulation of microplastics in typical commercial aquatic species: a case study at a productive aquaculture site in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135432.

- Hanachi, P.; Karbalaei, S.; Walker, T.R.; Cole, M.; Hosseini, S.V. Abundance and properties of microplastics found in commercial fish meal and cultured common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2019, 26, 23777–23787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05637-6.

- Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Sun, C.; Teng, J.; Chen, L.; Shan, E.; Zhao, J. Microplastics in fish meals: an exposure route for aquaculture animals. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 151049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151049.

- Blettler, M.C.M.; Abrial, E.; Khan, F.R.; Sivri, N.; Espinola, L.A. Freshwater plastic pollution: Recognizing research biases and identifying knowledge gaps. Water Res. 2018, 143, 416–424.

- Carpenter, E.J.; Anderson, S.J.; Harvey, G.R.; Miklas, H.P.; Peck, B.B. Polystyrene spherules in coastal waters. Science 1972, 178, 749–750. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.178.4062.749.

- Kartar, S.; Sainsbury, M.; Milne, R.A. Polystyrene waste in the Severn Estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1973, 4, 144.

- Cheung, L.T.O.; Lui, C.Y.; Fok, L. Microplastic contamination of wild and captive flathead grey mullet (Mugil cephalus). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040597.

- Feng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, J.; Gao, G. The accumulation of microplastics in fish from an important fish farm and mariculture area, Haizhou Bay, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133948.

- Reinold, S.; Herrera, A.; Saliu, F.; Hernández-González, C.; Martinez, I.; Lasagni, M.; Gómez, M. Evidence of microplastic ingestion by cultured European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112450.

- Piskuła, P.; Astel, A. Occurrence of microplastics in commercial fishes from aquatic ecosystems of northern Poland. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2024, 24(3), 492–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2023.12.005.

- Abbasi, S.; Soltani, N.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Turner, A.; Hassanaghaei, M. Microplastics in different tissues of fish and prawn from the Musa Estuary, Persian Gulf. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.076.

- Garcia, A.G.; Suarez, D.C.; Li, J.; Rotchell, J.M. A comparison of microplastic contamination in freshwater fish from natural and farmed sources. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 14488–14497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11605-2.

- Aranudova, D.; Stoyanova, S.; Georgieva, E.; Yancheva, V. From pond to plate: laser direct infrared (LDIR) chemical imaging system characterization and quantification of microplastics in farmed common carp (Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, 1758). Zoonotes 2025, 285, 1–4.

- Peñalver-Soler, R.M.; Pérez-Álvarez, M.D.; Pellerito, F.; Pérez-Ruzafa, Á.; Campillo, N.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Viñas, P. Direct laser infrared microscopy for the monitoring of microplastics in Holothuria poli andsediments of the Mar Menor coastal lagoon. Environ. Poll. 2025, 378, 126478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2025.126478.

- Cheng, X.; Yang, L.; Song, X.; Yao, D. Source, transport, and risk assessment of microplastics in the sediment-water interface of Baiyangdian Lake, China. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13(6), 119574.

- Lusher, A.L.; McHugh, M.; Thompson, R.C. Occurrence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract of pelagic and demersal fish from the English Channel. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 67, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.11.028.

- Torre, M.; Digka, N.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Tsangaris, C.; Mytilineou, C. Anthropogenic microfibres pollution in marine biota. a new and simple methodology to minimize airborne contamination. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113 (1–2), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.07.050.

- Perumal, K.; Muthuramalingam, S. Global sources, abundance, size, and distribution of microplastics in marine sediments – a critical review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 264, 107702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2021.107702.

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. 2021. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. Available online at: https://www.fishbase.org (08/2021).

- FAO 2020. Aquatic species fact sheets database. http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/3367/en. Helsinki.

- Zeytin, S.; Wagner, G.; Mackay-Roberts, N.; Gerdts, G.; Schuirmann, E.; Klockmann, S.; Slater, M. 2020. Quantifying microplastic translocation from feed to the fillet in European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 156, 111210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111210.

- Matavos-Aramyan, S. 2024. Addressing the microplastic crisis: A multifaceted approach to removal and regulation. Environ. Adv., 17, 100579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2024.100579.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).