1. Introduction

The global transportation and industrial sectors are foundational to economic development but face profound challenges due to their dependence on fossil fuels. This reliance drives two interconnected crises: the rapid depletion of finite petroleum reserves and the severe environmental degradation caused by pollutant emissions. Compression ignition (CI) engines, prized for their durability, high torque output, and fuel efficiency, are the workhorses of these sectors, particularly in heavy-duty transport, agriculture, and power generation. However, they are significant contributors to atmospheric pollution, emitting substantial quantities of harmful gases and particulates, including carbon monoxide (CO), unburnt hydrocarbons (HC), nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter (PM), and the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO₂) [

1,

2]. These emissions are linked to climate change, urban smog, acid rain, and serious public health issues such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, the search for renewable, sustainable, and cleaner-burning alternative fuels has become a global imperative, driven by both environmental mandates and energy security concerns [

3,

4].

Biodiesel, a renewable fuel derived from biological feedstocks via the transesterification process, has emerged as one of the most promising direct replacements or supplements for petroleum diesel. Chemically, it consists of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) and offers several inherent advantages: it is biodegradable, non-toxic, possesses a higher flash point for safer handling, and contains oxygen in its molecular structure. This oxygen content is a key differentiator, as it promotes more complete combustion within the engine cylinder. Perhaps most importantly, biodiesel is largely compatible with existing diesel engine infrastructure, often requiring little to no modification, especially at lower blend ratios, which facilitates its immediate adoption [

5,

6]. Extensive research has demonstrated that biodiesel-diesel blends can significantly reduce emissions of CO, HC, and PM compared to conventional diesel. However, the adoption of biodiesel is not without significant technical trade-offs that have hindered its widespread commercialization [

7,

8].

The primary limitations of biodiesel stem from its different physicochemical properties relative to diesel. Firstly, biodiesel has a lower calorific value (or heating value), typically 10–15% less than diesel. This means that for the same power output, a greater volume of fuel must be injected and combusted, leading to an increase in brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC).

Secondly, biodiesel has higher viscosity and density, which can negatively affect the fuel injection system’s atomization characteristics, potentially leading to larger droplet sizes, poorer air-fuel mixing, and incomplete combustion. Thirdly, as a result of these factors and differences in combustion phasing, biodiesel often exhibits a slight reduction in brake thermal efficiency (BTE), the measure of how effectively an engine converts the fuel’s chemical energy into useful mechanical work. The most persistent and challenging drawback, however, is the “biodiesel NOx penalty.” Biodiesel combustion consistently leads to higher emissions of nitrogen oxides. This is attributed to a combination of effects: the fuel-bound oxygen promotes higher local combustion temperatures; biodiesel’s higher cetane number can shorten ignition delay, leading to more premixed combustion; and its different radiative properties alter in-cylinder heat transfer. These factors collectively elevate the conditions that favor thermal NOx formation via the Zeldovich mechanism [

9,

10]. These limitations become increasingly pronounced as the percentage of biodiesel in the blend increases, making high-concentration blends (e.g., B50, B100) less practical without substantial engine recalibration or aftertreatment.

To overcome these inherent drawbacks, researchers have turned to advanced fuel modification techniques, with nanotechnology offering particularly promising avenues. The incorporation of metal oxide nanoparticles as fuel additives represents a frontier in combustion science. Nanoparticles, typically defined as particles with at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nanometers, possess an exceptionally high surface-area-to-volume ratio. This unique property grants them enhanced catalytic activity, superior heat transfer characteristics, and the ability to act as miniature energy carriers. When dispersed in fuel, they can fundamentally alter the combustion process. Among the various nanoparticles studied, aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) and cerium oxide (CeO₂) have shown distinct and complementary benefits. Aluminum oxide nanoparticles are excellent thermal conductivity enhancers. Their presence in the fuel droplet improves heat transfer between the burning gases and the unburned fuel, promoting more rapid and complete vaporization. This can lead to improved BTE and a reduction in the formation of soot precursors due to better air-fuel mixing [

11,

12]. Cerium oxide nanoparticles, on the other hand, are renowned for their oxygen storage capacity (OSC) facilitated by the facile Ce⁴⁺ ↔ Ce³⁺ redox cycle. During combustion, CeO₂ can release active oxygen species to oxidize CO and unburnt HC. More importantly, it can also buffer oxygen availability during the high-temperature post-flame period, moderating peak combustion temperatures and thereby suppressing the formation of thermal NOx. This dual role makes CeO₂ a potent multifunctional emission catalyst [

13,

14,

15,

16].

While considerable research exists on the individual effects of biodiesel and on the impact of single nanoparticle additives (either Al₂O₃ or CeO₂), a critical research gap remains in the systematic investigation of their combined and synergistic application. Most studies have focused on one nanoparticle type in isolation, or on biodiesel blends without considering the full spectrum of low to medium blend ratios. There is a lack of comprehensive data, particularly in the context of locally sourced, non-edible feedstocks like Jatropha curcas, which is of strategic importance to countries like Ethiopia. Jatropha curcas is an ideal biodiesel feedstock for arid and semi-arid regions. It is a non-edible, drought-resistant shrub that can thrive on marginal and degraded lands unsuitable for food crops, thereby avoiding the contentious “food vs. fuel” debate. Its seeds contain a high oil content (30–50% by weight), making its cultivation economically viable for rural communities while providing a sustainable source of renewable energy [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Understanding how nanoparticle additives interact with Jatropha biodiesel across a practical blend range (e.g., B5 to B25) is essential for developing optimized, high-performance fuel formulations tailored to local conditions and needs [

21,

22].

Therefore, this study is designed to systematically address this research gap. The central aim is to evaluate the individual and combined effects of Al₂O₃ and CeO₂ nanoparticle additives on the performance, combustion, and emission characteristics of a CI engine operating on diesel–Jatropha biodiesel blends. The investigation spans a comprehensive blend range from B5 to B25, with a particular focus on the widely adopted B20 blend. The specific objectives are fourfold: (1) To synthesize Jatropha biodiesel, prepare stable diesel-biodiesel-nanoparticle fuel blends, and characterize their key physicochemical properties; (2) To experimentally investigate the engine performance parameters, specifically BTE and BSFC, under varying load conditions; (3) To analyze the detailed emission profiles, including CO, HC, NOx, CO₂, and smoke opacity; and (4) To assess the separate and synergistic impacts of the nanoparticles and determine the most effective fuel formulation for achieving enhanced engine performance coupled with lower emissions. We hypothesize that the combination of Al₂O₃ and CeO₂ will produce a synergistic effect, where Al₂O₃ improves combustion completeness and thermal efficiency, while CeO₂ simultaneously reduces all major pollutants, including NOx, thereby creating a fuel that outperforms both conventional diesel and unmodified biodiesel. The outcomes of this research are expected to provide valuable empirical data and practical insights, contributing to the development of advanced, sustainable biofuel technologies. This work aligns with global efforts toward energy diversification, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and the promotion of circular economic models by valorizing a local, non-food resource.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock and Biodiesel Production

The primary feedstock for this study was Jatropha curcas seeds, sourced locally within Ethiopia to ensure relevance to the regional context. The seeds were cleaned, sun-dried, and decorrelated to remove shells. The crude Jatropha oil was then mechanically extracted using a screw press (Komet CA59). The extracted oil was filtered through a muslin cloth to remove solid impurities and stored in airtight containers. Prior to biodiesel production, the crude oil was characterized. Its acid value was determined via titration with 0.1 N ethanolic KOH according to ASTM D664, yielding a value of 0.47 mg KOH/g oil. This corresponds to a free fatty acid (FFA) content of approximately 0.24%, which is well below the 2% threshold. A low FFA content (<2%) is crucial as it allows for a simple, single-step alkali-catalyzed transesterification process, eliminating the need for a preliminary acid-catalyzed esterification step, thereby simplifying production and reducing costs [

23].

Biodiesel (B100) was produced via this single-step alkaline transesterification. For a standard batch, 500 mL of preheated Jatropha oil (60 °C) was placed in a 2 L round-bottom flask reactor equipped with a condenser, mechanical stirrer, and temperature controller. A catalyst solution was prepared by dissolving 5.1 g of potassium hydroxide (KOH) pellets (1% w/w of oil) in 240 mL of anhydrous methanol, achieving a methanol-to-oil molar ratio of approximately 6:1. The catalyst-methanol solution was then slowly added to the heated oil with continuous stirring at 600 rpm. The reaction was maintained at a constant temperature of 60 ± 2 °C for 90 minutes. Upon completion, the mixture was transferred to a separating funnel and allowed to settle for 24 hours. Two distinct layers formed: the lower, denser glycerol layer (a by-product) and the upper biodiesel layer. The glycerol was carefully drained off. The crude biodiesel was then washed several times with warm deionized water (at about 50 °C) to remove residual catalyst, soap, and methanol until the wash water became clear.

The washed biodiesel was finally dried using anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove any traces of water, resulting in clear, amber-colored Jatropha methyl ester (B100). The quality of the produced biodiesel was verified against key specifications of the international standard ASTM D6751. Critical properties such as density (ASTM D4052), kinematic viscosity at 40 °C (ASTM D445), flash point (ASTM D93), and acid value (ASTM D664) were measured and found to be within acceptable limits, confirming its suitability for engine testing [

24].

2.2. Preparation of Fuel Blends and Nano-Fuels

Commercial automotive diesel fuel (B0), conforming to Ethiopian Petroleum Enterprise specifications, was procured from a local station and used as the baseline reference fuel. Biodiesel-diesel blends were prepared on a volumetric basis using graduated cylinders and mechanical stirring for 15 minutes to ensure homogeneity. The prepared blends were: B0 (100% diesel), B5 (5% B100, 95% B0), B10, B15, B20, and B25.

Two types of metal oxide nanoparticles were used as fuel additives: aluminum oxide (γ-Al₂O₃) and cerium oxide (CeO₂). Both nanoparticles were commercially sourced (Sigma-Aldrich) with certified properties: an average particle size of approximately 30 nm and a purity greater than 99%. Based on an extensive review of literature and preliminary stability tests, specific concentrations were selected to maximize benefits while avoiding issues like agglomeration or injector clogging. The chosen concentrations were 150 parts per million (ppm) for Al₂O₃ and 50 ppm for CeO₂ [

25,

26]. To prepare the nano-fuel blends, a precise mass of nanoparticles (calculated based on the desired ppm concentration and the volume of fuel) was weighed using a high-precision analytical balance (±0.0001 g). The nanoparticles were added to 500 mL of the B20 biodiesel-diesel blend. To achieve a stable and uniform dispersion and prevent nanoparticle agglomeration—a common challenge that reduces effectiveness a non-ionic surfactant, Tween-80 (Polysorbate 80), was added at 1% by volume. The mixture (fuel + nanoparticles + surfactant) was then subjected to high-intensity ultrasonication using a probe sonicator (Sonics VCX750) operating at a frequency of 20 kHz. The ultrasonication process was carried out for 60 minutes in pulse mode (5 seconds on, 5 seconds off) to prevent excessive heating of the fuel. This process generates ultrasonic cavitation, creating microscopic bubbles that implode with tremendous force, effectively breaking apart nanoparticle clusters and dispersing them uniformly throughout the liquid fuel.

The stability of the prepared nano-fuel was assessed visually and by dynamic light scattering (DLS), confirming no visible sedimentation or phase separation for over 72 hours, indicating a stable colloidal suspension suitable for engine testing.

2.3. Experimental Setup and Instrumentation

The core experimental work was conducted on a fully instrumented engine test bench. The test engine was a single-cylinder, four-stroke, direct-injection, water-cooled, naturally aspirated diesel engine (Kirloskar TV1 model), representative of engines widely used in agricultural and small-scale industrial applications. The detailed technical specifications of the engine are provided in

Table 1. The engine was rigidly mounted on a sturdy test bed and coupled to an eddy current dynamometer (Schenck W230). The dynamometer served the dual purpose of applying a controlled braking load to the engine and measuring the resulting output torque with high accuracy (±0.2 Nm). Engine speed was measured using a magnetic pickup sensor coupled to a digital tachometer.

Figure 1.

Schematic of experimental setup.

Figure 1.

Schematic of experimental setup.

A comprehensive suite of instruments was integrated for data acquisition:

Fuel Measurement: An AVL 733S gravimetric fuel flow meter was used to measure fuel consumption with high accuracy by measuring the time taken to consume a fixed mass of fuel.

Air Flow Measurement: Air consumption was measured using a calibrated laminar flow element (LFE) connected to a differential pressure transmitter and temperature sensor.

Combustion Analysis: In-cylinder pressure was captured using a piezoelectric pressure transducer (Kistler 6125B) mounted flush with the cylinder head. The signal was conditioned by a Kistler 5018 charge amplifier. A high-resolution crank angle encoder (AVL 365) with 1° crank angle (CA) resolution provided the timing reference. This setup allowed for the calculation of key combustion parameters like heat release rate (HRR) and ignition delay.

Emission Measurement: Exhaust gases were analyzed using a state-of-the-art AVL DIGAS 444 five-gas analyzer. This device measured the concentrations of Carbon Monoxide (CO), Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), Unburnt Hydrocarbons (HC, as n-hexane equivalent), Nitrogen Oxides (NOx, as NO), and Oxygen (O₂). The analyzer was calibrated before each test session using standard calibration gases.

Smoke Measurement: Smoke opacity, an indicator of particulate matter or soot, was measured using an AVL 415S variable sampling smoke meter, which reports Filter Smoke Number (FSN).

Temperature Measurement: K-type thermocouples were installed at strategic locations: intake manifold, exhaust pipe (upstream of the analyzer), engine coolant inlet/outlet, and lubricating oil sump to monitor thermal states.

Data Acquisition: All analog and digital signals from the sensors were fed into a National Instruments Compact data acquisition system. A custom-developed interface in LabVIEW software was used for real-time data logging, visualization, and subsequent offline analysis.

The accuracy and uncertainty associated with each primary measuring instrument are critical for result reliability. These values, determined from calibration certificates and repeated measurements, are summarized in

Table 2, adhering to standard engineering uncertainty analysis protocols [

27].

2.4. Test Procedure and Data Analysis

A rigorous and systematic test procedure was followed to ensure data consistency and repeatability. The engine was first started and operated on neat diesel (B0) until it reached a stable thermal condition, indicated by a constant coolant temperature of 80 ± 5 °C. This warm-up period typically lasted 30-45 minutes. The experimental matrix covered four distinct engine load conditions: 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the maximum rated load (where 100% load corresponds to the maximum torque at the governed speed). The engine speed was not fixed but varied naturally with load, typically ranging from approximately 1000 rpm at 25% load to about 2900 rpm at full load, simulating real-world operating behavior.

For each test condition, the following protocol was executed: (1) The desired load was set on the dynamometer controller. (2) The engine was allowed to stabilize under this new load for a period of 10 minutes to ensure steady-state temperatures and operating parameters. (3) Once stable, data acquisition was initiated and all parameters (speeds, temperatures, pressures, fuel flow, emissions) were logged continuously over a period of 3 minutes. (4) The average values from this 3-minute window were computed and recorded as the representative data point for that condition. (5) This entire process was repeated three times for each fuel blend (B0, B5, B10, B15, B20, B25, and B20 with different nanoparticle additions) to establish repeatability and account for random variations. The test sequence for different fuels was randomized to eliminate any potential systematic drift in instrument readings.

The recorded raw data was processed to calculate the key performance metrics:

i. Brake Power (BP):

BP(kW)

Where:

T = Torque (Nm),

N = Speed (rpm)

a. Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE):

BTE = 100 (%)

Where:

LHV = Lower heating value (MJ/kg)

ṁf = Fuel mass flow rate (kg/h)

ii. Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC):

BSFC = (kg/kWh)

Where:

BP = Brake Power

ṁf = Fuel mass flow rate (kg/h)

Emission Reduction = ×100

Where:

E baseline =Emission from baseline fuel (e.g. dieselB0 or neat B20)

E modified = Emission from modified fuel (e.g. B20 with nanoparticles)

Emission results for the modified fuels biodiesel blends with were compared to the baseline diesel (B0) to calculate percentage reduction or increase. A comprehensive uncertainty analysis for the derived parameters (BTE, BSFC) was performed by propagating the individual instrumental uncertainties listed in

Table 2 using the root-sum-square (RSS) method. The total experimental uncertainty for all reported results was maintained below ±2.5%, which is considered acceptable for engineering experiments of this nature.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fuel Properties Characterization

The fundamental properties of a fuel dictate its behavior during storage, handling, injection, and combustion. A thorough characterization of the prepared blends is therefore essential.

Table 3 presents the key physicochemical properties of the diesel–biodiesel blends, all containing the combined nanoparticle additive (150 ppm Al₂O₃ + 50 ppm CeO₂). The trends observed are classic for biodiesel-diesel mixtures. Density increases linearly with the percentage of biodiesel. This is because biodiesel molecules (FAME) are generally heavier than typical hydrocarbon chains in diesel. The density rose from 832.5 kg/m³ for neat diesel (B0) to 849.4 kg/m³ for B25. Kinematic viscosity, a critical property affecting atomization, also shows a consistent increase with biodiesel content, from 2.89 mm²/s for B0 to 3.21 mm²/s for B25. The higher viscosity of biodiesel is due to its larger molecular size and polarity.

While this can be a drawback, all values remained well within the ASTM D975 specification range for diesel fuel (1.9–4.1 mm²/s), indicating acceptable flow characteristics. The most significant impact is on the calorific value. Biodiesel has a lower energy content per unit mass due to the presence of oxygen in its molecular structure. Consequently, the calorific value decreased progressively from 45.50 MJ/kg for B0 to 42.00 MJ/kg for B25, representing an energy deficit of approximately 7.7% for the B25 blend. This lower energy density is the primary reason for the increased fuel consumption observed with biodiesel. The cetane number, an indicator of ignition quality (a higher number means shorter ignition delay), showed a slight improvement with increasing biodiesel fraction. This is a beneficial effect of biodiesel, contributing to smoother combustion. The flash point increased significantly with biodiesel content, from 68 °C for diesel to 84 °C for B25, greatly improving the safety of fuel handling and storage. The addition of nanoparticles caused negligible changes to density and calorific value (<0.5%) but resulted in a very slight increase in viscosity (1-3%) due to the suspension of solid particles. More notably, the nanoparticles, especially CeO₂, contributed to a marginal improvement in the cetane number, enhancing ignition quality [

28,

29]. The successful dispersion and stability of the nanoparticles were confirmed, with no sedimentation observed over 72 hours, validating the preparation methodology [

30,

31].

3.2. Engine Performance Analysis

3.2.1. Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE)

Brake thermal efficiency is the ultimate measure of an engine’s effectiveness in converting the chemical energy of fuel into useful mechanical work. The variation of BTE with engine load for all tested fuels illustrates a universal trend: BTE increases with load for all fuels. This is attributed to the reduced relative importance of engine friction and heat losses at higher loads, coupled with improved combustion efficiency due to higher in-cylinder temperatures and turbulence. The performance of neat biodiesel blends (without nanoparticles) reveals their inherent limitation. Across the entire load spectrum, B5, B10, B15, B20, and B25 blends showed a consistent 2–5% lower BTE compared to baseline diesel (B0). This efficiency penalty is a direct consequence of biodiesel’s two main characteristics: (1) its lower calorific value, meaning more fuel mass must be burned for the same energy input, and (2) its higher viscosity, which can lead to slightly poorer atomization and slower mixing, resulting in marginally less complete combustion.

The transformative effect of nanoparticle additives is clearly demonstrated. While individual nanoparticles (Al₂O₃ or CeO₂ alone) improved BTE over neat B20, the most striking result came from their combination. The B20 blend with combined Al₂O₃ and CeO₂ nanoparticles achieved a peak BTE of 34.1% at full load (100%). This not only surpassed the efficiency of neat B20 but also exceeded that of conventional diesel, which recorded 32.5% under the same condition. This represents a 4.9% improvement over diesel and a 7.9% improvement over neat B20. This significant enhancement is a testament to synergistic action. Al₂O₃ nanoparticles, with their high thermal conductivity, act as micro-heat carriers. They facilitate faster heat transfer from the burning gases to the incoming fuel spray, promoting more rapid vaporization and better preparation of the air-fuel mixture. CeO₂ nanoparticles, functioning as a catalytic oxygen donor, ensure that this better-prepared mixture undergoes more complete and faster oxidation. The combined effect is a combustion process that is both more vigorous and more thorough, extracting more work from each unit of fuel energy despite its lower inherent calorific value [

32,

33,

34,

35]. This finding is pivotal as it demonstrates that the efficiency penalty of biodiesel can be not just mitigated but completely reversed.

Figure 2.

BTE vs load for All Blends with Nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

BTE vs load for All Blends with Nanoparticles.

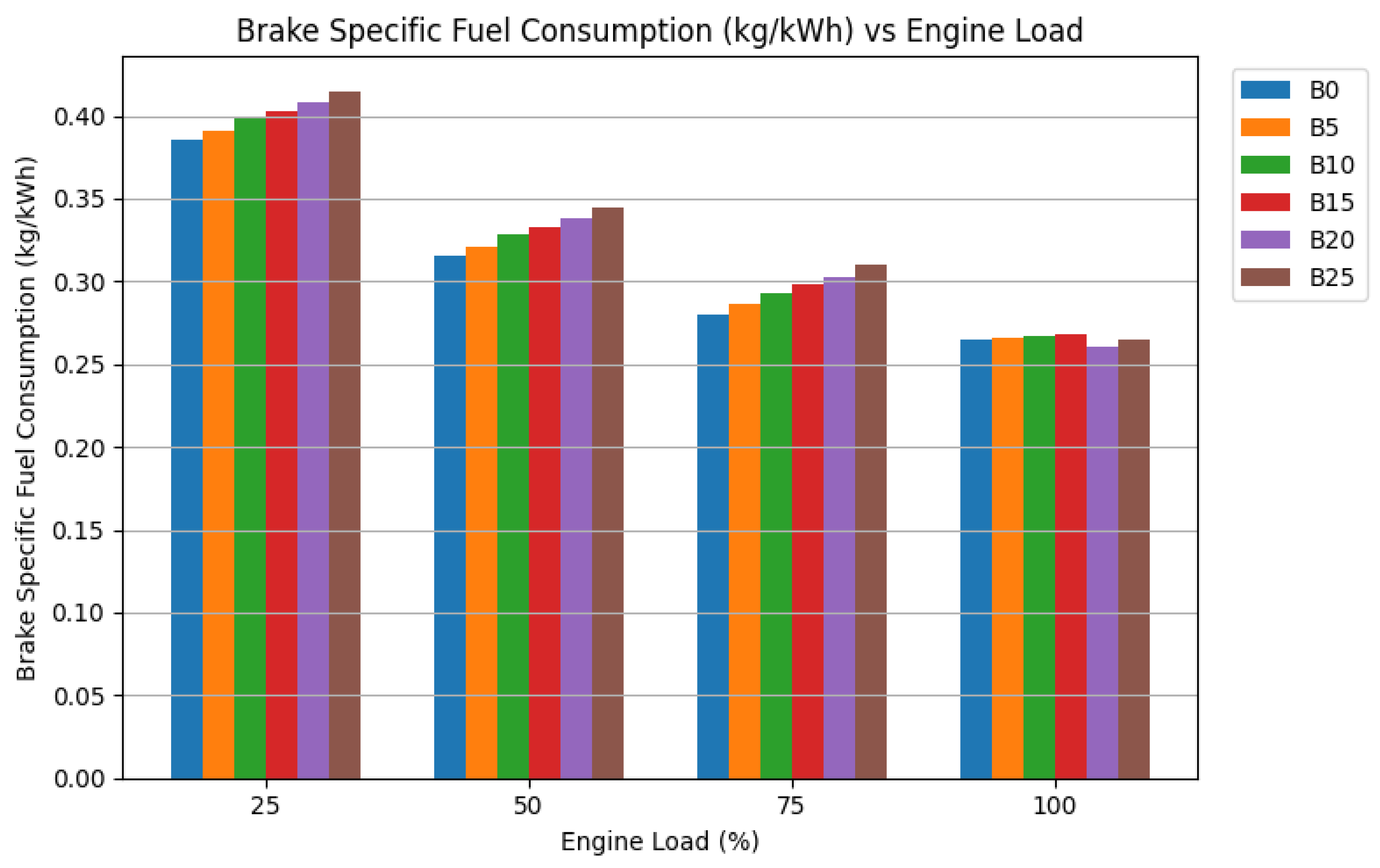

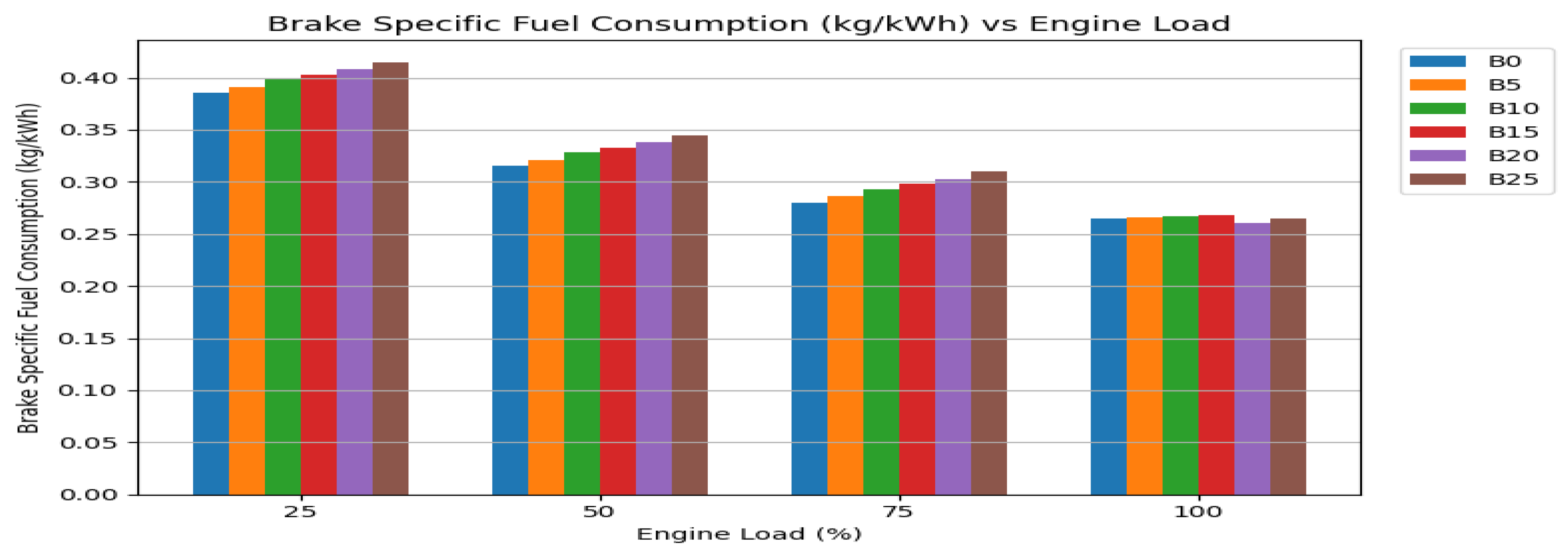

3.2.2. Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC)

Brake-specific fuel consumption is the inverse indicator of efficiency; a lower BSFC means less fuel is needed to produce a unit of power. The trend of BSFC with load follows the expected pattern: BSFC decreases as load increases, reflecting the engine’s improving efficiency at higher operating points. The data for neat biodiesel blends confirm the fuel consumption penalty: they exhibited higher BSFC than diesel across all loads, particularly at lower loads. This is the direct operational cost of their lower energy density—more fuel volume is physically required to deliver the same power.

The influence of nanoparticles becomes most pronounced at the high-load condition, where combustion is most intense. At full load, the BSFC for the B20 blend with combined nanoparticles was recorded at 0.260 kg/kWh. This is marginally lower than the BSFC of diesel (0.265 kg/kWh) and represents an approximate 5-6% reduction compared to neat B20. This convergence of BSFC values between the optimized nano-biodiesel and conventional diesel is a critical result. It indicates that the combustion-enhancing effects of the nanoparticles are so effective that they fully compensate for biodiesel’s lower energy content. The engine consumes virtually the same mass of the nano-fuel as it would of diesel to produce the same power output. The mechanisms are the same as for BTE improvement: enhanced atomization from Al₂O₃ and micro-explosions, and promoted oxidation from CeO₂ lead to a more complete release of the available chemical energy [

36,

37,

38,

39]. For practical applications, this means that switching to this nano-enhanced B20 fuel would not result in a mileage penalty for the operator—a major practical concern addressed.

Figure 3.

Brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC).

Figure 3.

Brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC).

3.3. Emission Characteristics

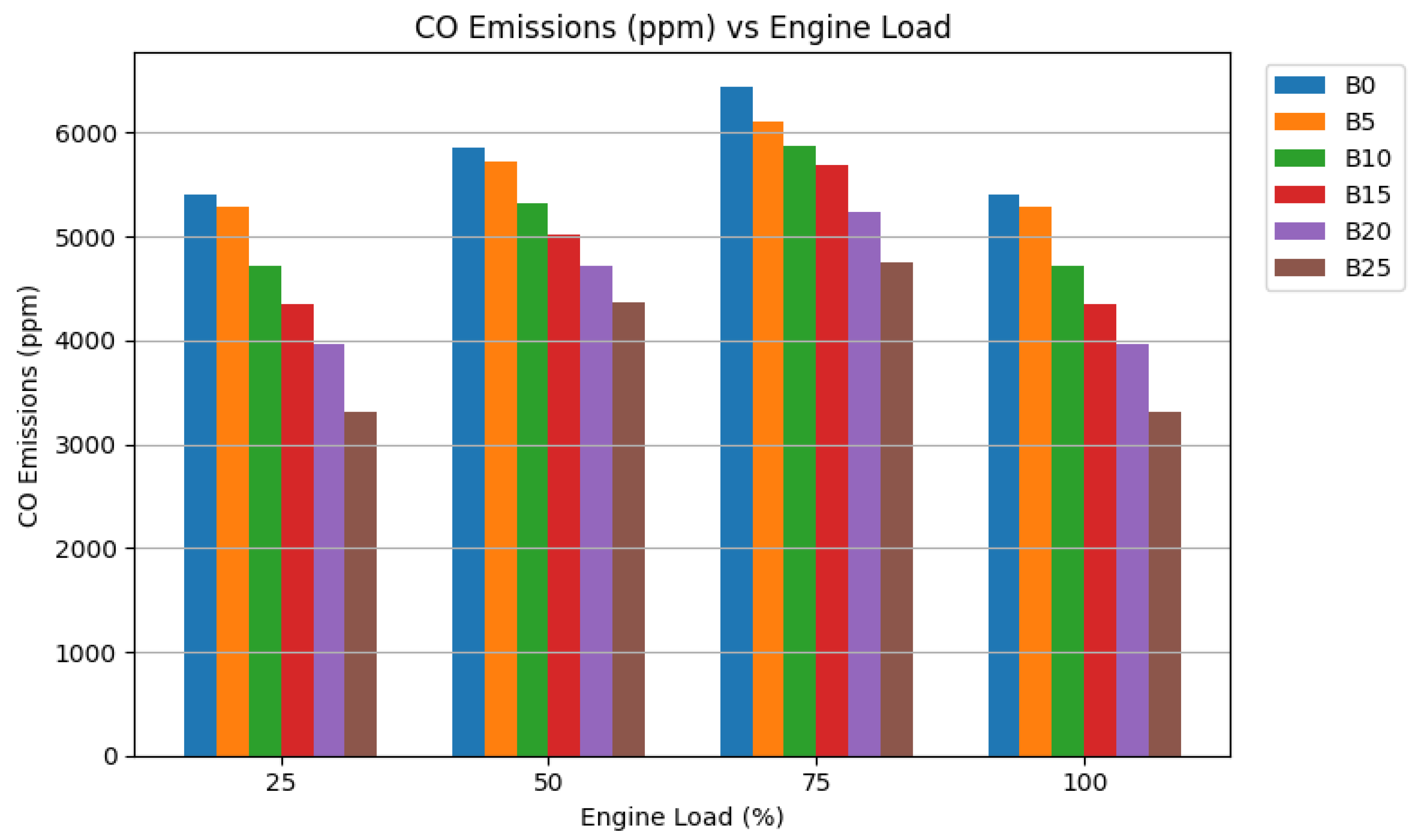

3.3.1. Carbon Monoxide (CO) and Unburnt Hydrocarbon (HC) Emissions

Carbon monoxide and unburnt hydrocarbons are primary products of incomplete combustion, resulting from insufficient oxygen, low temperatures, or poor air-fuel mixing in regions of the combustion chamber. A consistent and well-established benefit of biodiesel is immediately apparent: all biodiesel blends, even without additives, produced lower CO and HC emissions than diesel across the entire load range. This is a direct result of biodiesel’s intrinsic oxygen content (typically 10-12% by weight), which provides additional oxygen molecules within the fuel itself, promoting more complete oxidation of carbon and hydrogen to CO₂ and H₂O, even in locally fuel-rich zones [

40].

Figure 4.

CO Emissions at different Load.

Figure 4.

CO Emissions at different Load.

The addition of nanoparticles, however, dramatically amplifies this advantage. CeO₂ nanoparticles are particularly potent oxidation catalysts. The B20 blend with combined nanoparticles achieved reductions of 55.3% in CO and 33.8% in HC compared to baseline diesel at full load. These are substantial improvements. The mechanism involves the Ce⁴⁺/Ce³⁺ redox cycle. During combustion, CeO₂ releases active oxygen species (O⁻) from its crystal lattice.

These highly reactive species attack and oxidize CO molecules to CO₂ and fragment unburnt HC molecules, initiating their oxidation pathway at lower temperatures than would otherwise be possible. Al₂O₃ contributes by improving the overall combustion environment (better mixing, higher local temperatures), ensuring that these catalytic reactions proceed to completion. The result is a near-total minimization of incomplete combustion products [

41,

42].

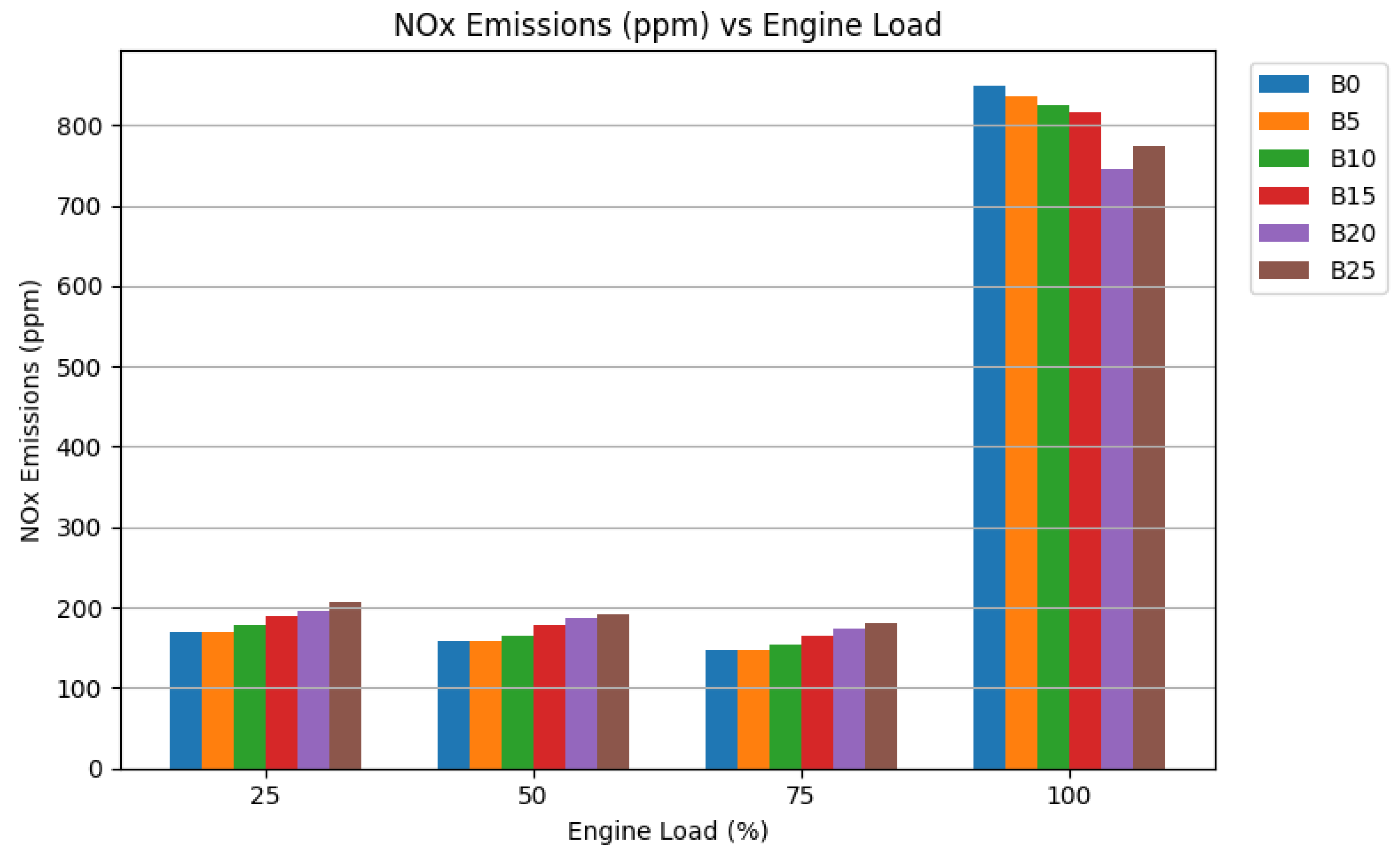

3.3.2. Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) Emissions

Nitrogen oxide emissions, primarily NO and NO₂, form through high-temperature reactions between atmospheric nitrogen and oxygen (thermal NOx) and are the most challenging aspect of biodiesel combustion. The data confirms the “biodiesel NOx penalty”: neat B20 produced higher NOx emissions than diesel across most loads, especially at medium to high loads where combustion temperatures peak.

The behavior of the nanoparticle additives here is nuanced and reveals their distinct modes of action. The addition of Al₂O₃ nanoparticles alone to B20 resulted in a slight further increase in NOx. This is logically consistent: by improving heat transfer and combustion efficiency, Al₂O₃ can raise the average in-cylinder temperature, exacerbating the thermal NOx formation mechanism. In stark contrast, the addition of CeO₂ nanoparticles alone led to a significant decrease in NOx. This is the key finding that addresses the major drawback of biodiesel. The B20 blend with combined nanoparticles emitted 745 ppm of NOx at full load, which is 12.4% lower than diesel (850 ppm) and 19% lower than neat B20.

This reduction is attributed to the unique oxygen buffering capacity of CeO₂. While it supplies oxygen for oxidizing CO and HC, it also acts as an oxygen “scavenger” or moderator during the high-temperature post-flame period. By reversibly storing and releasing oxygen, CeO₂ prevents local oxygen concentrations from reaching the very high levels that drive the Zeldovich (thermal) NOx mechanism. It effectively “smooths out” the oxygen availability, lowering the peak flame temperature the most critical factor for NOx formation. The combined nanoparticle blend thus achieves an optimal compromise: it harnesses the thermal benefits of Al₂O₃ for efficiency while employing CeO₂ to actively suppress the resulting NOx tendency, delivering performance without the pollution trade-off [

15,

16,

43,

44].

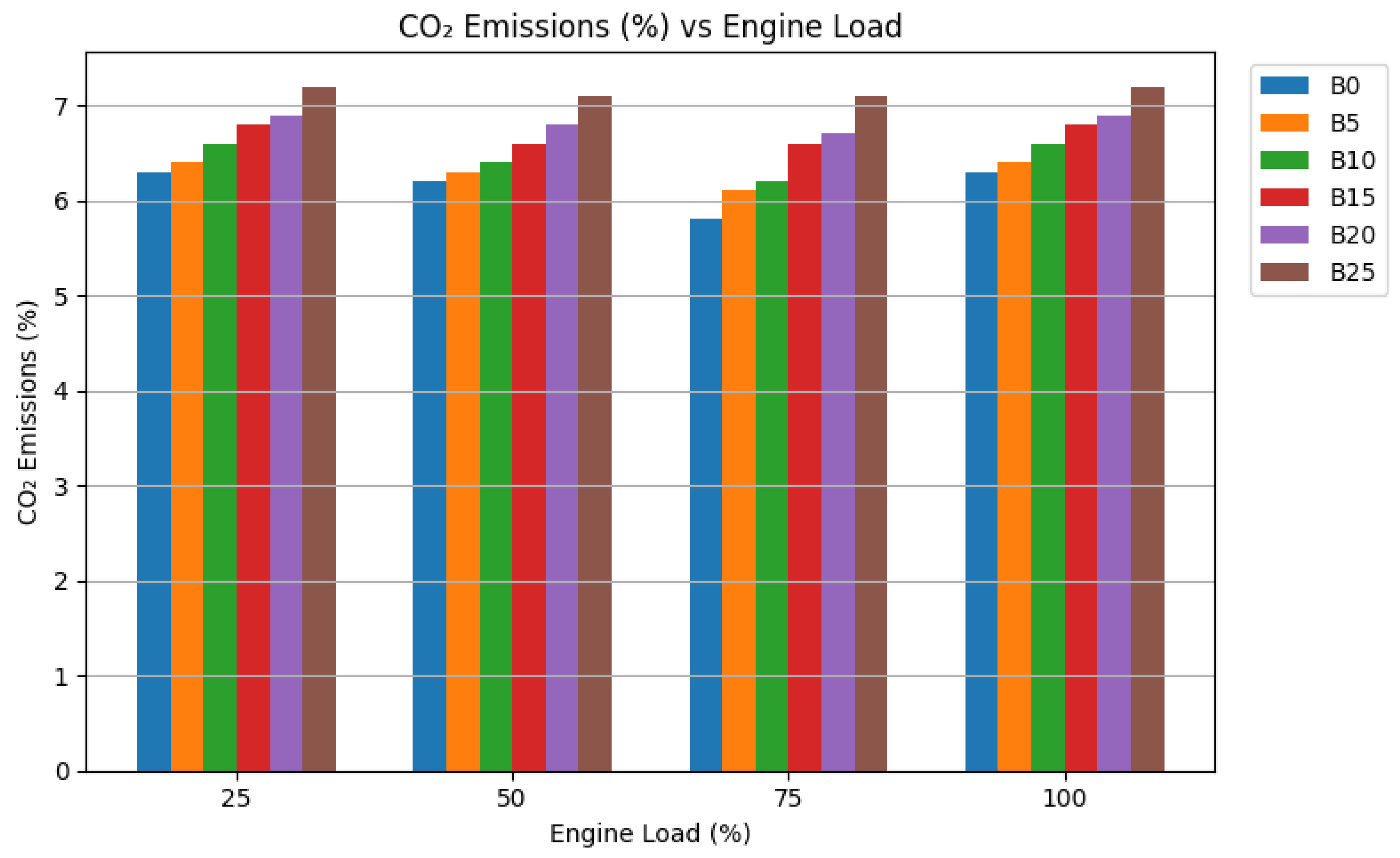

3.3.3. Smoke Opacity and Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Emissions

Smoke opacity, measured as Filter Smoke Number (FSN), is a strong indicator of soot or particulate matter formation, which occurs in fuel-rich, high-temperature zones during the diffusion combustion phase. Biodiesel’s oxygen content inherently reduces soot formation by promoting more complete oxidation of carbon. The data shows that all biodiesel blends had lower smoke than diesel. Nanoparticle addition pushed this reduction further. The optimal B20+nano blend showed a 31% reduction in smoke opacity versus diesel. CeO₂ is a known soot oxidation catalyst; it lowers the activation energy for soot burnout, enabling more complete oxidation of carbon particles both within the cylinder and in the exhaust stream [

45].

CO₂ emissions showed a marginal increase with biodiesel content and nanoparticle addition. It is crucial to interpret this correctly. CO₂ is the final product of complete combustion of carbon. A slight rise in CO₂ concentration, when accompanied by large decreases in CO, HC, and smoke, is not an environmental drawback in this context. Instead, it is a positive indicator of superior combustion completeness. It confirms that a greater fraction of the fuel’s carbon is being fully oxidized to CO₂, rather than being emitted as harmful incomplete combustion products. The overall carbon output per unit of work done (g CO₂/kWh) showed minimal variation, indicating that the fuel’s renewable carbon cycle (from plant growth) is the dominant factor, not a decrease in combustion efficiency [

35,

46].

Figure 6.

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Emissions at different Load.

Figure 6.

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Emissions at different Load.

3.4. Determination of the Optimal Blend and Discussion of Synergy

To objectively identify the best-performing fuel formulation, a multi-criteria decision analysis was performed. A scoring system assigned weights of 40% to Performance (BTE, BSFC), 40% to Emissions (CO, HC, NOx, Smoke), and 20% to Practicality (stability, cost implication, safety). The B20 blend doped with 150 ppm Al₂O₃ and 50 ppm CeO₂ consistently achieved the highest total score. It provided the optimal balance: the highest thermal efficiency, fuel economy on par with diesel, the deepest cuts in CO, HC, and smoke, and effective control over the biodiesel NOx penalty, all while demonstrating excellent fuel stability.

A quantitative assessment of synergy was conducted. A synergy factor (SF) was calculated for key parameters as: SF = (Actual Combined Effect) / (Expected Additive Effect), where the expected effect is the sum of improvements from individual nanoparticles. For BTE, SF was 1.18 (18% synergy). For CO reduction, SF was 1.25 (25% synergy). An SF > 1 confirms a positive synergistic interaction, meaning the combination works better than the sum of its parts.

This synergy likely stems from the complementary roles: Al₂O₃ creates conditions for efficient combustion (heat, mixing), while CeO₂ capitalizes on these conditions to maximize oxidation and temper its side-effects (NOx). This validates the core hypothesis of the study and explains why the combined formulation outperforms all others [

47,

48].

The results are in strong agreement with the broader literature on nanoparticle additives while advancing it through the demonstration of synergy in Jatropha biodiesel. The magnitude of improvement in BTE and NOx reduction is at the higher end of reported values, which can be attributed to the optimized dosage, effective dispersion via ultrasonication, and the use of a surfactant for stability factors not always rigorously controlled in earlier studies [

49,

50,

51,

52].

4. Conclusions

This comprehensive experimental investigation yields the following definitive conclusions:

Performance Transformation: The synergistic addition of aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃, 150 ppm) and cerium oxide (CeO₂, 50 ppm) nanoparticles effectively overcomes the fundamental performance limitations of Jatropha biodiesel. The B20 nano-fuel blend achieved a superior brake thermal efficiency of 34.1% at full load, outperforming both conventional diesel (32.5%) and neat B20. Its brake-specific fuel consumption of 0.260 kg/kWh was comparable to diesel, demonstrating that the nanoparticle-enhanced combustion fully compensates for biodiesel’s lower calorific value.

Comprehensive Emission Reduction: The nano-additives induced profound and broad-spectrum emission benefits. The optimal B20 blend with combined nanoparticles achieved dramatic reductions relative to diesel: carbon monoxide by 55.3%, unburnt hydrocarbons by 33.8%, and smoke opacity by 31%. Most significantly, the typically elevated NOx emissions from biodiesel were not merely controlled but actively reduced by 12.4% compared to diesel, directly addressing the most persistent barrier to biodiesel adoption.

Technical Viability and Synergy Confirmed: The B20 blend with combined Al₂O₃ and CeO₂ nanoparticles is identified as the optimal formulation. It requires no engine modification, utilizes a locally available, non-edible feedstock, and demonstrates excellent fuel stability. The study provides quantitative evidence (synergy factor >1) confirming a positive synergistic interaction between the nanoparticle types, where Al₂O₃ enhances combustion completeness and CeO₂ acts as a multifunctional emissions moderator.

Contribution to Sustainable Energy: This work presents a technically sound, immediately applicable, and sustainable pathway for clean energy. It aligns with circular economy and sustainable development goals by valorizing a non-food crop for fuel, reducing dependence on imported fossil fuels, significantly lowering criteria pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions, and offering potential socioeconomic benefits through local biodiesel production and rural job creation.

5. Recommendations

Based on the compelling evidence from this research, the following recommendations are proposed to translate these findings into practical impact and guide future work:

Pilot-Scale Implementation: To validate real-world feasibility and economic benefits, pilot-scale demonstration projects should be initiated in key sectors within Ethiopia and similar regions. Ideal candidates include public transport fleets (buses, minibuses) and stationary agricultural machinery (tractors, irrigation pumps). These projects should monitor long-term engine health, fuel stability in storage, and overall cost-effectiveness.

Standardization and Quality Assurance: For widespread adoption, it is crucial to develop national or regional fuel standards and standardized preparation protocols for nanoparticle-enhanced biodiesel. These protocols must specify key parameters: nanoparticle size and purity, concentration ranges, type and concentration of surfactant (e.g., Tween-80 at 1% v/v), ultrasonication energy and duration, and stability testing criteria. This will ensure consistent fuel quality, performance, and safety in the market.

Future Research Directions: To build upon this work, subsequent studies should focus on:

Long-Term Durability: Conduct extended engine endurance tests (e.g., 500-1000 hours) to comprehensively assess wear characteristics of critical components (fuel injectors, piston rings, cylinder liners), nanoparticle accumulation in lubricating oil, and any potential for deposit formation.

Lifecycle and Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA): Perform a full lifecycle assessment (LCA) to quantify the net environmental benefits from well-to-wheel. A detailed TEA is needed to evaluate the economic viability of large-scale production, including costs of nanoparticle synthesis/import, blending infrastructure, and compare it with the savings from reduced fuel consumption and potential carbon credits.

Advanced Formulations: Explore the effects of other promising nanoparticle combinations (e.g., CeO₂ with TiO₂, SiO₂), different morphologies (nanorods, nanotubes), or surface functionalization to further enhance performance or reduce costs.

Policy and Stakeholder Engagement: Successful adoption requires supportive frameworks. Policymakers should consider:

Introducing targeted subsidies, tax incentives, or green-fuel credits for blends containing sustainable biofuels with emission-reducing additives.

Funding the establishment of local supply chains for biodiesel production and, if feasible, nanoparticle synthesis or responsible import mechanisms.

Fostering collaborative partnerships between universities, fuel producers, agricultural cooperatives, and government agencies to build local technical capacity, raise awareness, and provide training for mechanics and fuel handlers on the new technology.

By following these recommendations, the promising technology demonstrated in this study can be effectively integrated into national energy strategies, promoting energy independence, environmental protection, and sustainable rural development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

E.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing. M.D.: Supervision, Review.

Data Availability

Data available upon request.

References

- Sundar, Shanmuga Sundaram Padmanaba; et al. An experimental approach on the utilization of palm oil biodiesel. Energy Reports 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesha, Pijakala; et al. Impact of alumina and cerium oxide nanoparticles on performance and emission characteristics of diesel engine. Fuel 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benti, Natei Ermias. Biodiesel production in Ethiopia: Current status and future prospects. Renewable Energy 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vellaiyan, Suresh. Effect of cerium oxide nano additive on the working characteristics of water emulsified biodiesel fueled diesel engine: An Experimental Study. Fuel 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Mines and Energy. The Biofuel Development and Utilization Strategy of Ethiopia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K. Srinivasa; et al. Effects of Cerium Oxide Nano Particles Addition in Diesel and Bio Diesel on the Performance and Emission Analysis of CI Engine. Journal of Engineering 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Pushparaj; Mishra, Vineeta. Experimental investigation on the influence of cerium oxide nanofluid on emission pattern of biodiesel in a diesel engine. Energy Conversion and Management 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, Dhiraj S. Experimental investigation of effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on biodiesel-diesel blends. International Journal of Engineering Research 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gebru, Hadish Teklehaimanot; et al. Investigation of the Performance and Emission Characteristics of Biodiesel-Diesel Blends in Direct Injection Diesel Engines. Energies 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, T Srinivasa; et al. Effect of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Additive Blended in Palm Biodiesel on Performance and Emission Characteristics. Fuel 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Allasi, Haiter Lenin; et al. Influence of synthesized (green) cerium oxide nanoparticle on biodiesel properties and engine performance. Fuel 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Parawira, Wilson. Biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas: A review. Scientific Research and Essays 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, Vimal Chandra; et al. Jatropha curcas: A potential biofuel plant for sustainable environmental development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riayatsyah, T. M. I.; et al. Current Progress of Jatropha Cureas Commoditization as Biodiesel Feedstock: A Comprehensive Review. Fuel 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, Joon Ching; et al. Biodiesel production from jatropha oil by catalytic and non-catalytic approaches. Bioresource Technology 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, May Ying; Idaty, Tinia; Ghazi, Mohd. A review of biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas L. oil. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartika, Amalia; et al. Biodiesel production from jatropha seeds: Solvent extraction and in situ transesterification. Fuel 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Debella, Hailu Abebe; et al. Production, optimization, and characterization of Ethiopian Jatropha biodiesel. Fuel 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, Dena A.; et al. Smart utilization of jatropha (Jatropha curcas Linnaeus) seeds for biodiesel production. Fuel 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A.; Prabu, R.B. Emission control strategy by adding alumina and cerium oxide nano particle in biodiesel. Fuel 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vellaiyan, S.; et al. Combustion, performance and emission analysis of diesel engine fueled with water biodiesel emulsion fuel and nano additive. Fuel 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tamrat, Samuel; et al. Emission and performance characteristics of nanoparticle-doped biodiesel. Energy Reports 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Abul Kalam Hossain, Abdul. Impact of Nano additives on the Performance and Emission Characteristics of Diesel Engine. Fuel 2019.

- Prabu, A.; et al. An assessment on the nanoparticles-dispersed aloe vera biodiesel blends on the performance, combustion and emission characteristics of a DI diesel engine. Fuel 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; et al. Effective utilization of waste cooking oil in a single-cylinder diesel engine using alumina nanoparticles. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Soudagar, M. E. M.; et al. An investigation on the influence of aluminum oxide nano-additive and hinge oil methyl ester on engine performance, combustion and emission characteristics. Renewable Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; et al. Combined effect of oxygenated liquid and metal oxide nanoparticle fuel additives on the combustion characteristics of a biodiesel engine. Fuel 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ranaware, A. A.; Satpute, S. T. Correlation between effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles and ferrofluid on the performance and emission characteristics of a CI Engine. Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Selvan, V. Arul Mozhi; et al. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticle addition in biodiesel. Fuel 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Udayakumar, M.; et al. Cerium oxide as an additive in biodiesel/diesel fueled internal combustion engines: a concise review. Fuel 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elgharbawy, Abdallah Sayed. Revealing the superior effect of using prepared nano additives for biodiesel. Fuel 2024.

- Mahgoub, Bahaaddein K.M. Effect of nano-biodiesel blends on CI engine performance. Fuel 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, R.; et al. Effect of different metal oxide nano additives in jatropha biodiesel. Fuel 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ergen, Gokhan. Comprehensive analysis of the effects of alternative fuels on diesel engine performance and emissions. Fuel 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesha, P.; et al. Effects of particle size of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the combustion behavior and exhaust emissions of a diesel engine. Fuel 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Raj; et al. Performance and Emission Analysis of Waste Cooking Oil Biodiesel with Nanoparticle Additives. Fuel 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hussien, Ahmed M.; et al. Enhancement of diesel engine performance and emissions burning biodiesel with cerium oxide nanoparticles additive. Fuel 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, Muhamad Sharul Nizam; et al. Carbon nanotube as effective enhancer for performance and emission characteristics of biodiesel. Fuel 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, E. P.; et al. Performance and emission reduction characteristics of cerium oxide nanoparticle-water emulsion biofuel in diesel engine. Fuel 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M. V.; et al. Influence of metal-based cerium oxide nanoparticle additive on performance, combustion, and emissions with biodiesel in diesel engine. Fuel 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, Abdulfatah Abdu; et al. The effect of biodiesel and CeO2 nanoparticle blends on CRDI diesel engine performance. Fuel 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gumus, S.; et al. Aluminum Oxide and Copper Oxide Nanodoesel Fuel Properties and Usage in a Compression Ignition Engine. Fuel 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, Abdul; et al. Production, optimization, and characterization of biodiesel from Jatropha curcas. Fuel 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Balaji, et al. Performance and emission characteristics of ci engine fueled with jatropha biodiesel. Fuel 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S. H.; et al. Effect of added alumina as nano-catalyst to diesel-biodiesel blends on performance and emission characteristics of CI engine. Fuel 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gada, M.S.; Jayaraj, S. A comparative study on the effect of nano-additives on the performance and emission characteristics of biodiesel. Fuel 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy; Ministry of Mines. The Biofuel Development and Utilization Strategy of Ethiopia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, Vimal Chandra; et al. Jatropha curcas: A potential biofuel plant for sustainable environmental development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riayatsyah, T. M. I.; et al. Current Progress of Jatropha Cureas Commoditization as Biodiesel Feedstock: A Comprehensive Review. Fuel 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, Joon Ching; et al. Biodiesel production from jatropha oil by catalytic and non-catalytic approaches. Bioresource Technology 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, May Ying; Idaty, Tinia; Ghazi, Mohd. A review of biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas L. oil. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartika, Amalia; et al. Biodiesel production from jatropha seeds: Solvent extraction and in situ transesterification. Fuel 2013. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).