Submitted:

23 January 2026

Posted:

26 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

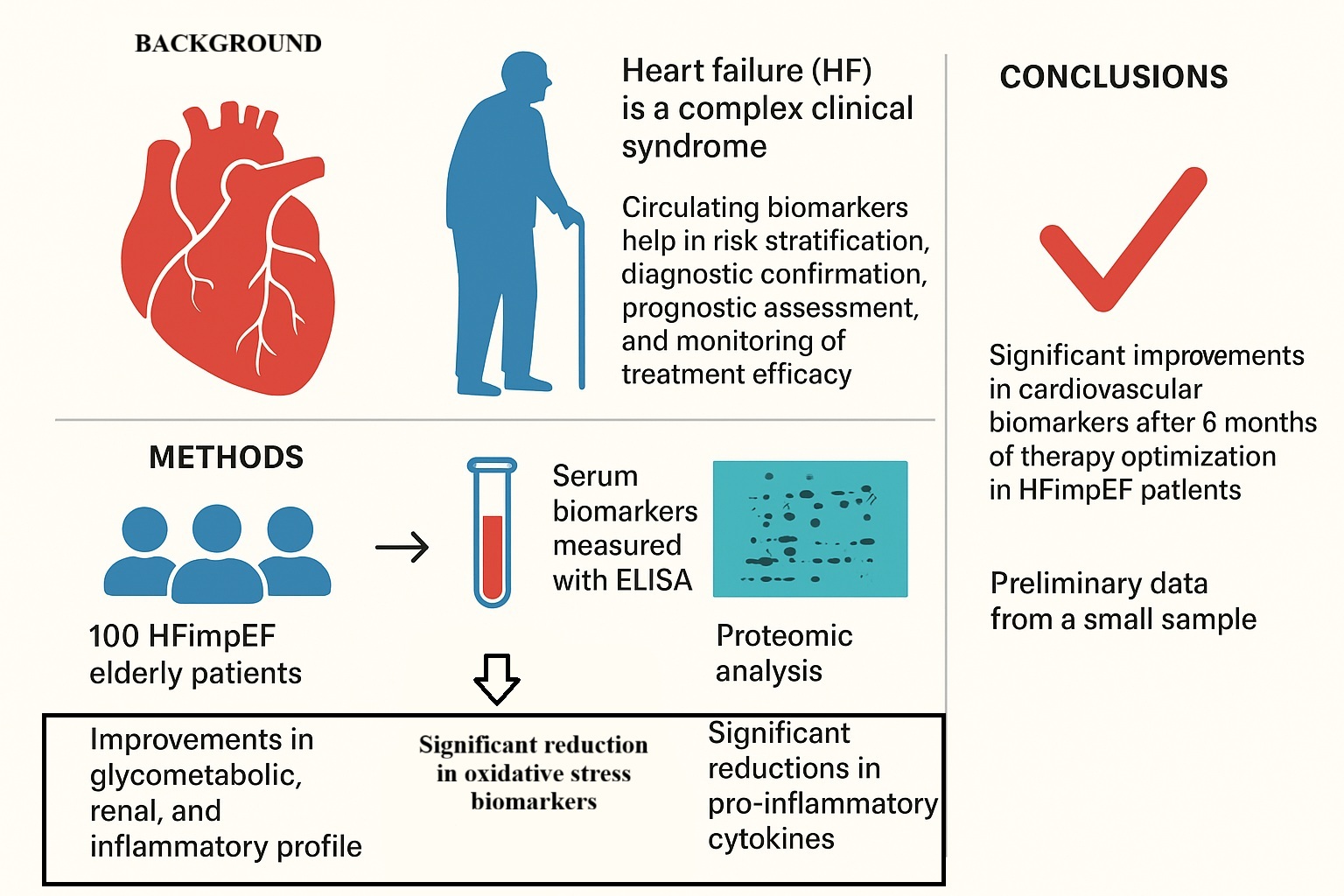

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Procedures

2.3. Echocardiographic Parameters

2.4. Laboratory Determinations

2.5. Circulating Biomarkers Evaluation

2.6. Proteomic Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Population Characteristics

3.2. Follow-Up Evaluation

3.3. Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

3.4. Proteomic Biomarkers Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclosures

List of Abbreviation

| e-GFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| DTT | dithiothreitol |

| IAA | iodoacetamide |

| ACT | acetonitrile |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

| DDA 1-5 | 5 data dependent acquisition |

| SD | standard deviation |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| ICH | ischemic heart disease |

| SAS | Sleep apnoea syndrome |

| AF | atrial fibrillation |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| NOACs | Novel oral anticoagulants |

| FPG | fasting plasma glucose |

| IL6RB | interleukin-6 signal transducer |

| THRB | coagulation factor II |

| ADIPO | adiponectin |

| MMP2 | matrix metalloproteinase 2 |

| MMP9 | matrix metalloproteinases 9 |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| HFimEF | Heart Failure with improved ejection fraction |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| IBP4 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 4 |

| TSP4 | Thrombospondin-4 |

| ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| SDC4 | Syndecan-4 |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| GCP | Good clinical practice |

| MAGIC-HF | MAgna GraecIa evaluation of Comorbidities in patients with Heart Failure |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| PP | Pulse pressure |

| LVM | Left ventricular mass |

| BSA | body surface area |

| CI | Cardiac Index |

| RVOT | Right ventricular outflow tract |

| RAA | Right atrium area |

| TAPSE | Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

References

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.S.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition O. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global Burden of Heart Failure: A Comprehensive and Updated Review of Epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Čelutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, M.; Pabon, M.A.; Bhatt, A.S.; Savarese, G.; Metra, M.; Volterrani, M.; Lombardi, C.M.; Vaduganathan, M.; Solomon, S.D.; Vardeny, O.; et al. Heart Failure With Improved Ejection Fraction: Definitions, Epidemiology, and Management. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 2401–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulot, J.S.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Halliday, B.P.; Metra, M.; Moura, B.; Petrie, M.C.; Savarese, G.; Senni, M.; Van Linhout, S.; et al. Heart Failure Improvement, Remission, and Recovery: A European Journal of Heart Failure Expert Consensus Document. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 27, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januzzi, J.L.; Camargo, C.A.; Anwaruddin, S.; Baggish, A.L.; Chen, A.A.; Krauser, D.G.; Tung, R.; Cameron, R.; Nagurney, J.T.; Chae, C.U.; et al. The N-Terminal Pro-BNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) Study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 95, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.S. Serial Natriuretic Peptide Measurements Are Not Useful in Heart Failure Management: The Art of Medicine Remains Long. Circulation 2013, 127, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaguida, P.L.; Don-Wauchope, A.C.; Oremus, M.; McKelvie, R.; Ali, U.; Hill, S.A.; Balion, C.; Booth, R.A.; Brown, J.A.; Bustamam, A.; et al. BNP and NT-ProBNP as Prognostic Markers in Persons with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Heart Fail. Rev. 2014, 19, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhene, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Acheampong, E.; Zhengcan, Z.; Xiaoyan, Q.; Yunsheng, X.; et al. Biomarkers in Heart Failure: The Past, Current and Future. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimo, A.; Januzzi, J.L.; Vergaro, G.G.V.; Ripoli, A.; Latini, R.; Masson, S.; Magnoli, M.; Anand, I.S.; Cohn, J.N.; Tavazzi, L.; et al. Prognostic Value of High-Sensitivity Troponin T in Chronic Heart Failure an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2018, 137, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.; Coca, A.; De Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Blood Press. 2018, 27, 314–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Victor, M.A.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereux, R.B.; Alonso, D.R.; Lutas, E.M.; Gottlieb, G.J.; Campo, E.; Sachs, I.; Reichek, N. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: Comparison to Necropsy Findings. Am. J. Cardiol. 1986, 57, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galo, J.; Celli, D.; Colombo, R. Effect of Sacubitril/Valsartan on Neurocognitive Function: Current Status and Future Directions. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2021, 21, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altiok, E.; Neizel, M.; Tiemann, S.; Krass, V.; Kuhr, K.; Becker, M.; Zwicker, C.; Koos, R.; Lehmacher, W.; Kelm, M.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of Endocardial and Epicardial Left Ventricular Myocardial Deformation - Comparison of Strain-Encoded Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2012, 25, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Castro, A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, V.; Miceli, S.; Armentaro, G.; Mannino, G.C.; Fiorentino, V.T.; Perticone, M.; Succurro, E.; Hribal, M.L.; Andreozzi, F.; Perticone, F.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Left Ventricular Performance in Patients with Different Glycometabolic Phenotypes. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurno, M.; Cassano, V.; Maruca, F.; Pastura, C.A.; Divino, M.; Fazio, F.; Severini, G.; Clausi, E.; Armentaro, G.; Miceli, S.; et al. Effects of SGLT2-Inhibitors on Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress, and Platelet Activation in Elderly Diabetic Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saotome, M.; Ikoma, T.; Hasan, P.; Maekawa, Y. Cardiac Insulin Resistance in Heart Failure: The Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, C.E.; Zhang, M.; Cave, A.C.; Shah, A.M. NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Redox Signalling in Cardiac Hypertrophy, Remodelling and Failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 71, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, T.; Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Utsumi, H.; Kang, D.; Hattori, N.; Uchida, K.; Arimura, K.I.; Egashira, K.; Takeshita, A. Mitochondrial Electron Transport Complex I Is a Potential Source of Oxygen Free Radicals in the Failing Myocardium. Circ. Res. 1999, 85, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T.J.; Mussa, S.; Gastaldi, D.; Sadowski, J.; Ratnatunga, C.; Pillai, R.; Channon, K.M. Mechanisms of Increased Vascular Superoxide Production in Human Diabetes Mellitus: Role of NAD(P)H Oxidase and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Circulation 2002, 105, 1656–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Matsushima, S. Oxidative Stress and Heart Failure. Am. J. Physiol. - Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawaz, M.; Langer, H.; May, A.E. Platelets in Inflammation and Atherogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 3378–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.; Lip, G.Y.H. Platelets and Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massberg, S.; Gawaz, M.; Grüner, S.; Schulte, V.; Konrad, I.; Zohlnhöfer, D.; Heinzmann, U.; Nieswandt, B. A Crucial Role of Glycoprotein VI for Platelet Recruitment to the Injured Arterial Wall in Vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.J.; Shrestha, K.; Sheehey, B.; Li, X.S.; Guggilam, A.; Wu, Y.; Finucan, M.; Gabi, A.; Medert, C.M.; Westfall, K.; et al. Elevated Plasma Marinobufagenin, An Endogenous Cardiotonic Steroid, Is Associated With Right Ventricular Dysfunction and Nitrative Stress in Heart Failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2015, 8, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagrov, A.Y.; Fedorova, O. V. Effects of Two Putative Endogenous Digitalis-like Factors, Marinobufagenin and Ouabain, on the Na+,K+-Pump in Human Mesenteric Arteries. Proceedings of the Journal of Hypertension 1998, Vol. 16, 1953–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagrov, A.Y.; Shapiro, J.I.; Fedorova, O. V. Endogenous Cardiotonic Steroids: Physiology, Pharmacology, and Novel Therapeutic Targets. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009, 61, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacoby, J.J.; Kalinowski, A.; Liu, M.G.; Zhang, S.S.M.; Gao, Q.; Chai, G.X.; Ji, L.; Iwamoto, Y.; Li, E.; Schneider, M.; et al. Cardiomyocyte-Restricted Knockout of STAT3 Results in Higher Sensitivity to Inflammation, Cardiac Fibrosis, and Heart Failure with Advanced Age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 12929–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, A.; Rampoldi, A.; Chao, M.; Li, D.; Armand, L.; Hwang, H.; Liu, R.; Jha, R.; Fu, H.; Maxwell, J.T.; et al. Functional and Molecular Effects of TNF-α on Human IPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, S.A.; Epelman, S. Chronic Heart Failure and Inflammation. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Xu, Q. Roles of Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Binding Proteins in Regulating IGF Actions. Proceedings of the General and Comparative Endocrinology 2005, Vol. 142, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungbauer, C.G.; Riedlinger, J.; Block, D.; Stadler, S.; Birner, C.; Buesing, M.; König, W.; Riegger, G.; Maier, L.; Luchner, A. Panel of Emerging Cardiac Biomarkers Contributes for Prognosis Rather than Diagnosis in Chronic Heart Failure. Biomark. Med. 2014, 8, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellings, M.W.M.; Van Almen, G.C.; Sage, E.H.; Heymans, S. Thrombospondins in the Heart: Potential Functions in Cardiac Remodeling. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2009, 3, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.M.; Maillet, M.; Vanhoutte, D.; Schloemer, A.; Sargent, M.A.; Blair, N.S.; Lynch, K.A.; Okada, T.; Aronow, B.J.; Osinska, H.; et al. A Thrombospondin-Dependent Pathway for a Protective ER Stress Response. Cell 2012, 149, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, E.G.; Sopko, N.; Blech, L.; Popović, Z.B.; Li, J.; Vasanji, A.; Drumm, C.; Krukovets, I.; Jain, M.K.; Penn, M.S.; et al. Thrombospondin-4 Regulates Fibrosis and Remodeling of the Myocardium in Response to Pressure Overload. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 2363–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigkou, V.; Oikonomou, E.; Anastasiou, A.; Lampsas, S.; Zakynthinos, G.E.; Kalogeras, K.; Katsioupa, M.; Kapsali, M.; Kourampi, I.; Pesiridis, T.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Heart Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.; Wolf, S. ICAM-1 Signaling in Endothelial Cells. Proceedings of the Pharmacological Reports 2009, Vol. 61, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, K.; Welsh, P.; Docherty, K.F.; Morrow, D.A.; Jhund, P.S.; De Boer, R.A.; O’Meara, E.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; et al. Cellular Adhesion Molecules and Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure: Findings from the DAPA-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwahara, F.; Kai, H.; Tokuda, K.; Niiyama, H.; Tahara, N.; Kusaba, K.; Takemiya, K.; Jalalidin, A.; Koga, M.; Nagata, T.; et al. Roles of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 in Hypertensive Cardiac Remodeling. Proceedings of the Hypertension 2003, Vol. 41, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.R.; Humphries, M.J.; Bass, M.D. Synergistic Control of Cell Adhesion by Integrins and Syndecans. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnath, R.D.; Butler, M.J.; Newman, G.; Desideri, S.; Russell, A.; Lay, A.C.; Neal, C.R.; Qiu, Y.; Fawaz, S.; Onions, K.L.; et al. Blocking Matrix Metalloproteinase-Mediated Syndecan-4 Shedding Restores the Endothelial Glycocalyx and Glomerular Filtration Barrier Function in Early Diabetic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Whole population (n.100) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 87 (87%) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 66.7 | ||

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 60 (60%) | ||

| AF, n (%) | 34 (34%) | ||

| Dislipidemia, n (%) | 48 (48%) | ||

| SAS, n (%) | 42 (42%) | ||

| IHD, n (%) | 65 (65%) | ||

| Obesity, n (%) | 23 (23%) | ||

| VHD, n (%) | 42 (42%) | ||

| CKD, n (%) | 26 (26%) | ||

| COPD, n (%) | 20 (20) | ||

| T2DM, n (%) | 51 (51%) | ||

| Smokers, n (%) | 20 (20%) | ||

| NYHA class | |||

| NYHA class II | 70 | ||

| NYHA class III | 30 | ||

| Baseline FU | |||

| β-blockers, n | 85 84 | ||

| ACEi/ARBs, n | 44 38 | ||

| SGLT2i, n | 43 80 | ||

| MRAs, n | 30 80 | ||

| ARNI, n | 42 50 | ||

| GLP-1RA, n | 13 16 | ||

| Insulin, n | 10 11 | ||

| Statins, n | 83 85 | ||

| Diuretics, n | 65 70 | ||

| Antiplatelets drug, n | 84 84 | ||

| VKAs, n | 12 3 | ||

| NOACs, n | 27 34 |

| Baseline | Follow up | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.0±5.6 | 30.1±4.8 | 0.823 |

| SBP, mmHg | 124.5±13.9 | 123.9±14.5 | 0.595 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74.1±9.0 | 74.4±8.5 | 0.695 |

| Na, mmol/l | 141.0±2.6 | 141.0±2.8 | 0.934 |

| K, mmol/l | 4.5±0.4 | 4.5±0.4 | 0.801 |

| FPG, mg/dl | 110.0±34.8 | 104.0±25.0 | 0.017 |

| FPI, μU/ml | 26.0±11.3 | 23.8±8.8 | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c, (%) | 6.5±0.9 | 6.3±0.8 | 0.019 |

| Albumin, mg/dl | 4.0±0.6 | 4.0±0.7 | 0.817 |

| Vitamin D, ng/ml | 27.5±8.9 | 29.7±8.6 | 0.027 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.1±0.3 | 1.0±0.2 | 0.022 |

| eGFR, ml/min | 74.0±5.9 | 76.5±8.6 | 0.046 |

| PLT, 103/mm3 | 208.8±48.6 | 201.4±45.2 | 0.052 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 66.0±29.2 | 63.8±24.0 | 0.443 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 45.8±10.3 | 46.0±9.5 | 0.948 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 113.6±39.8 | 115.6±36.5 | 0.533 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 4.1±1.4 | 3.0±1.2 | <0.0001 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 7.5±0.7 | 5.3±1.3 | 0.427 |

| NT-pro-BNP (pg/ml) | 2175.4±648.4 | 1785.7±521.3 | <0.0001 |

| Baseline | Follow up | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAVi, ml/m2 | 44.1±11.5 | 44.0±12.6 | 0.933 |

| LVESV/BSA, ml/m² | 82.2±16.0 | 79.8±14.3 | 0.058 |

| LVEF, % | 45.4±9.3 | 48.9±6.3 | <0.0001 |

| CI, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 1883.7±192.2 | 1906.3±237.6 | 0.181 |

| E/A | 1.1±0.5 | 1.1±0.4 | 0.232 |

| E/e’ | 14.9±4.7 | 14.3±4.2 | 0.028 |

| GLS, % | -11.5±1.6 | -12.4±2.2 | <0.0001 |

| RVOTp, m/s | 2.8±0.5 | 2.7±0.5 | 0.195 |

| TAPSE, mm | 19.3±4.0 | 19.8±3.6 | 0.047 |

| s-PAP, mmHg | 39.6±12.5 | 37.4±10.3 | 0.048 |

| IVC, mm | 19.2±3.0 | 18.3±2.3 | <0.0001 |

| TAPSE/s-PAP, mm/mmHg | 0.6±0.2 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.310 |

| Baseline | Follow up | p | Δ(T0T6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 2.7±0.6 | 2.4±0.5 | <0.0001 | -11.1% |

| TNF-α | 29.0±6.7 | 24.7±5.7 | <0.0001 | -14.8% |

| MRBG | 1.2±0.2 | 1.0±0.1 | <0.0001 | -16.7% |

| Nox-2 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 | <0.0001 | -28.6% |

| 8-isoprostane | 73.4±10.8 | 55.6±10.1 | <0.0001 | -24.2% |

| Sp-selectin | 121.8±19.7 | 98.3±15.7 | <0.0001 | -19.3% |

| GPVI | 59.5±12.0 | 45.5±11.1 | <0.0001 | -23.5% |

| ProteinName | UniProtID | Gene | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAH2 | P00918 | CA2 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 |

| IBP4 | P22692 | IGFBP4 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 |

| B1AHL2 | B1AHL2 | FBLN1 | Fibulin-1 |

|

CD59 glycoprotein |

P13987 | CD59 | CD59 glycoprotein |

| TSP4 | P35443 | THBS4 | Thrombospondin-4 |

| CNTN1 | Q12860 | CNTN1 | Contactin-1 |

| LG3BP | Q08380 | LGALS3BP | Galectin-3-binding protein |

| IL6RB | P40189 | IL6ST | Interleukin-6 receptor subunit beta |

| THRB | P00734 | F2 | Prothrombin |

| PERM | P05164 | MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| ADIPO | Q15848 | Adipoq | Adiponectin |

| MMP2 | P08253 | MMP2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| MMP9 | P14780 | MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| TIMP1 | P01033 | TIMP | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 |

| IGF1 | P05019 | IGF1 | Insulin-like growth factor I |

| ICAM1 | P05362 | ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| VCAM1 | P19320 | VCAM1 | Vascular cell adhesion protein 1 |

| SDC4 | P31431 | SDC4 | Syndecan-4 |

| CYTC | P01034 | CST3 | Cystatin-C |

| Protein name | Baseline | Follow up | p | Δlog2 (T0-T6) | %Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAH2 | 15.3±1.2 | 14.4±1.8 | 0.226 | -0.9 | -46.4% |

| IBP4 | 14.6±0.4 | 14.2±0.3 | 0.012 | -0.4 | -24.2% |

| B1AHL2 | 14.7±0.7 | 14.4±0.6 | 0.338 | -0.3 | -18.8% |

| CD59 glycoprotein | 14.4±0.9 | 13.7±0.9 | 0.067 | -0.7 | -38.4% |

| TSP4 | 9.8±1.1 | 7.1±3.8 | 0.028 | -2.7 | -84.6% |

| CNTN1 | 13.5±0.6 | 13.4±0.5 | 0.564 | -0.1 | -6.7% |

| LG3BP | 18.6±0.5 | 18.5±0.5 | 0.814 | -0.1 | -6.7% |

| IL6RB | 12.6±0.4 | 12.4±0.3 | 0.057 | -0.2 | -12.9% |

| THRB | 18.1±0.9 | 17.6±0.6 | 0.124 | -0.5 | -29.3% |

| PERM | 12.7±0.9 | 12.4±1.0 | 0.517 | -0.3 | -18.8% |

| ADIPO | 16.9±0.7 | 17.4±0.9 | 0.137 | +0.5 | +41.4% |

| MMP2 | 13.4±0.6 | 13.2±0.4 | 0.304 | -0.2 | -12.9% |

| MMP9 | 14.1±0.6 | 13.8±1.0 | 0.456 | -0.3 | -18.8% |

| TIMP1 | 13.6±0.5 | 13.4±0.7 | 0.211 | -0.2 | -12.9% |

| IGF1 | 13.6±0.7 | 14.0±0.7 | 0.107 | +0.4 | +31.9% |

| ICAM1 | 12.6±0.5 | 12.2±0.5 | 0.030 | -0.4 | -24.2% |

| VCAM1 | 14.4±0.5 | 14.3±0.4 | 0.689 | -0.1 | -6.7% |

| SDC4 | 10.6±0.5 | 10.1±0.6 | 0.005 | -0.5 | -29.3% |

| CYTC | 16.9±0.6 | 16.6±0.4 | 0.070 | -0.3 | -18.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).