2. Introduction

2.1. Background and Emerging Reports

Beginning in early 2021, licensed embalmers and clinicians in several countries reported the recurrent removal of coherent, white, rubber-elastic intravascular casts during routine postmortem care (Haviland, 2023, 2024; Hirschman, 2022). These structures conform to the vascular lumens, extend through natural vascular bifurcations, and exhibit a tensile, elastic resistance unlike the friable, gelatinous material typical of ordinary postmortem clots. Survey data suggest that these observations are widespread, with many embalmers describing an abrupt increase in their frequency following 2021 (Worldwide Embalmer Blood Clot Survey, 2023; Haviland, 2024).

Figure 1.

Representative anomalous intravascular casts (“AIC clots” collected during routine postmortem care.[1].

Figure 1.

Representative anomalous intravascular casts (“AIC clots” collected during routine postmortem care.[1].

Although these field reports initially emerged outside peer-reviewed pathology literature, their internal consistency raised a fundamental question: do these casts represent a recognised postmortem artifact, or are they indicative of a discrete pathological entity? Their unusual gross appearance, firm cohesion, and fibre-rich architecture differ materially from the characteristics of canonical thrombi described in standard haemostasis and forensic pathology texts. More recently, clinically documented examples have appeared in living patients, including fibre-rich white material collected from post-operative lymphatic drainage systems where red-cell content is minimal, suggesting that these structures are not limited to postmortem settings, not just the normal blood stream.

Figure 2.

White AICs in axillary drainage tube collected in a bowl by the patient.

Figure 2.

White AICs in axillary drainage tube collected in a bowl by the patient.

Together, these observations underscore the need for systematic study rather than informal dismissal.

2.2. Rationale for Focused Structural Analysis

Before biochemical or mechanistic interpretations can be meaningfully pursued, the foundational question concerns structure: what are these casts made of, and how do their macro- and micro-architectures compare to recognised thrombotic and postmortem materials? Gross morphology determines whether the material behaves as a coherent, lumen-filling matrix with unusual elasticity, branching, or tensile strength. Histology reveals whether classical features of thrombus formation—such as laminated fibrin structure, enmeshed red blood cells, platelet aggregates, or inflammatory infiltrates—are preserved, reduced, or absent.

A morphology- and histology-first analysis is justified for three reasons:

-

1.

Classification: establishing whether anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) correspond to any known pathological category.

-

2.

Differentiation: identifying structural features that distinguish AICs from ordinary postmortem clots or antemortem thrombi.

-

3.

Foundation: providing a structural baseline necessary for interpreting subsequent elemental and proteomic analyses reported in companion papers.

Because public and clinical discussion has preceded formal laboratory characterisation, a blinded, multi-site structural analysis is essential for establishing evidence-based classification.

2.3. Aim of the Study

The aim of this first paper is:

To characterize the gross morphological and histological architecture of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) using blinded, multi-site analyses, and to determine whether they represent a discrete structural phenomenon distinct from ordinary postmortem or thrombotic clots.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Acquisition and Coding

White, rubber-elastic intravascular casts were obtained from the waste streams of licensed embalmers and pathologists in routine postmortem settings between 2022 and 2024. Samples were collected using sterile forceps and placed directly into clean, labelled containers with 10% buffered formalin for preservation and transportation. All contributors provided written attestations confirming the circumstances of collection, and a chain-of-custody log was maintained from the point of retrieval to laboratory receipt.

Upon arrival at the analytical site, each specimen was assigned a random alphanumeric code to ensure full anonymisation. All morphological and histological assessments were performed under blinded conditions, with laboratory personnel unaware of tissue type, donor identity, geographic origin, embalmer narratives, or any clinical background associated with the decedent. All analytic procedures and evaluation criteria were pre-specified prior to sample processing to minimise bias and ensure methodological consistency across laboratories.

3.2. Gross Morphological Assessment

Each coded sample underwent standardised gross examination under controlled lighting on a sterile dissection surface. High-resolution photographs were taken using a DSLR imaging system with a fixed macro lens, colour-calibrated reference card, and metric scale.

Measurements included:

Dry weight (g)

Total length (cm)

Maximum and minimum diameter (mm)

Lumen conformity and branching geometry

Surface texture and sheen

Mechanical properties were assessed qualitatively but consistently across samples. Analysts recorded:

Elasticity (degree of stretch without fracture)

Cutting resistance (including the characteristic “squeak” reported by laboratory staff)

Tensile behaviour when traction was applied along the longitudinal axis

Fragmentation behaviour (friable vs cohesive)

These descriptors were chosen because they reliably differentiate the reported casts from canonical postmortem thrombi, which are typically gelatinous, friable, and non-elastic (Hirschman, 2022; Worldwide Embalmer Blood Clot Survey, 2023).

3.3. Histological Processing

Representative sections from each specimen were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24–48 hours, thereafter processed through graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin using standard clinical histopathology protocols (Bancroft, 2019).

Blocks were sectioned at 4–5 µm on a rotary microtome and sections mounted onto glass slides. All sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), selected for its ability to demonstrate fibrin, cellular inclusions, vascular organisation, and architectural layering.

Slides were imaged using a calibrated digital microscopy system equipped with:

Bright-field illumination;

High wattage tungsten lamp;

Blue colour correction filter;

Plan achromat objectives;

4×, 10×, 40× objectives;

High-resolution CMOS sensor.

Images were stored in a central database under their coded identifiers.

3.4. Histological Evaluation Criteria

Histological evaluation followed a predefined scoring framework to reduce interpretive bias. Each slide was reviewed independently by two blinded analysts, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Inter-observer agreement was high across laboratories, with evaluators independently identifying the same core architectural features. Standardised scoring criteria and predefined morphological descriptors were used to minimise interpretive variability.

Criteria included the presence, absence, or prominence of:

-

1.

Fibrinous lamination — concentric or layered fibrin architecture typical of organised thrombi.

-

2.

Lines of Zahn — alternating platelet/fibrin and erythrocyte/leucocyte layers indicating formation under pulsatile flow (antemortem).

-

3.

Fiber architecture — thickness, orientation, bundling, and interweaving pattern of fibrin-like fibres.

-

4.

Cellular inclusions — erythrocytes, leukocytes, endothelial cells, or platelets entrapped within the matrix.

-

5.

Matrix homogeneity vs heterogeneity — uniform vs patchy composition; abrupt transitions between fibrillar and non-fibrillar zones.

-

6.

Vacuolation or voids — structural gaps suggestive of liquefaction, degradation, or gas artefact.

These criteria were selected because they differentiate antemortem thrombi, postmortem clots, protein-dense casts, and non-canonical fibrillar materials (Bancroft, 2019; Haviland, 2024).

3.5. Ethical Considerations

All specimens were postmortem waste-stream biological materials collected in accordance with local jurisdictional standards for embalmer handling. No living individuals were involved, no identifiable personal data were accessed, and no intervention or clinical procedure was performed for research purposes. According to prevailing ethics-board guidelines, research on anonymised, discarded postmortem materials does not constitute human subject research and does not require institutional review (NZ National Ethics Advisory Committee, 2021).

4. Results

4.1. Gross Morphology

Canonical postmortem clot morphology (context for comparison)

For reference, typical postmortem clots present as either “currant-jelly” or “chicken-fat” coagula (Bancroft, 2019). Currant-jelly clots are dark red, gelatinous, non-adherent masses dominated by loosely organised erythrocytes. Chicken-fat clots are pale yellow to tan, friable, and result from postmortem plasma–cell separation. Both forms lack tensile strength, display no laminations or Lines of Zahn, and readily wash out of the vasculature.

Figure 3.

Canonical postmortem clots: chicken-fat (pale yellow) and currant-jelly (dark red/black).

Figure 3.

Canonical postmortem clots: chicken-fat (pale yellow) and currant-jelly (dark red/black).

These reference standards provide a baseline for differentiating anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) from physiologically expected postmortem material.

Gross morphology of anomalous intravascular casts (AICs)

The collected AIC specimens displayed striking deviations from this canonical morphology. Samples ranged from a few millimetres to >25 cm in length and were cream to opaque white with minimal red discolouration, usually restricted to focal points where casts had adhered to vascular endothelium.

Many specimens exhibited multiple, anatomically plausible bifurcations, indicating that the material had conformed to branching vascular lumens rather than forming amorphous postmortem aggregates (Haviland, 2023, 2024; Hirschman, 2022).

Heterogeneity was also observed: some regions were enriched with entrapped leucocytes and areas of lysed erythrocytes, whereas others were entirely white and fibrous.

Figure 4.

Raw AIC samples from a single donor.

Figure 4.

Raw AIC samples from a single donor.

To improve reproducibility, each sample was dried, subdivided into ~5 g aliquots, and distributed to multiple laboratories for replicated analysis. Importantly, these specimens were not preselected for pathological features; they were obtained as part of routine mortuary workflow, minimising selection bias.

Figure 5.

Representative sample segment processed for histology.

Figure 5.

Representative sample segment processed for histology.

Mechanical behaviour and acoustic emission

Cutting behaviour differed markedly from ordinary clots. Whereas postmortem clots shear silently and fragment easily, AICs consistently produced a distinct “squeak” upon scalpel transection.

This phenomenon is consistent with stick–slip friction and elastic recoil, mechanisms known to produce acoustic emissions when dense elastic materials (e.g., vulcanised rubber) are cut (Cai et al., 2023). Such behaviour implies a tension-bearing, cross-linked microstructure rather than the gelatinous coagulum of conventional postmortem clots.

While elastic behaviour in biological clots is generally associated with cross-linked fibrin, the acoustic findings further indicate a cohesive, mechanically resilient architecture that differs fundamentally from postmortem coagula.

These observations are inconsistent with the physical properties of conventional postmortem clots.

4.2. Histological Features

Sample processing overview

Figure 6.

Raw clot samples as received in 10% buffered formalin.

Figure 6.

Raw clot samples as received in 10% buffered formalin.

A representative specimen from an anonymised male donor in his 70s underwent: formalin fixation, paraffin embedding, 5 µm sectioning, and H&E staining in an independent histopathology laboratory.

Five slide sets from two subsamples were distributed to independent laboratories for replicated evaluation in different countries.

To provide an integrated visual overview of the specimen

’s architectural features across magnifications, a composite micrograph (

Figure 7) illustrates the progression from low-power morphology to high-resolution fibrillar organisation.

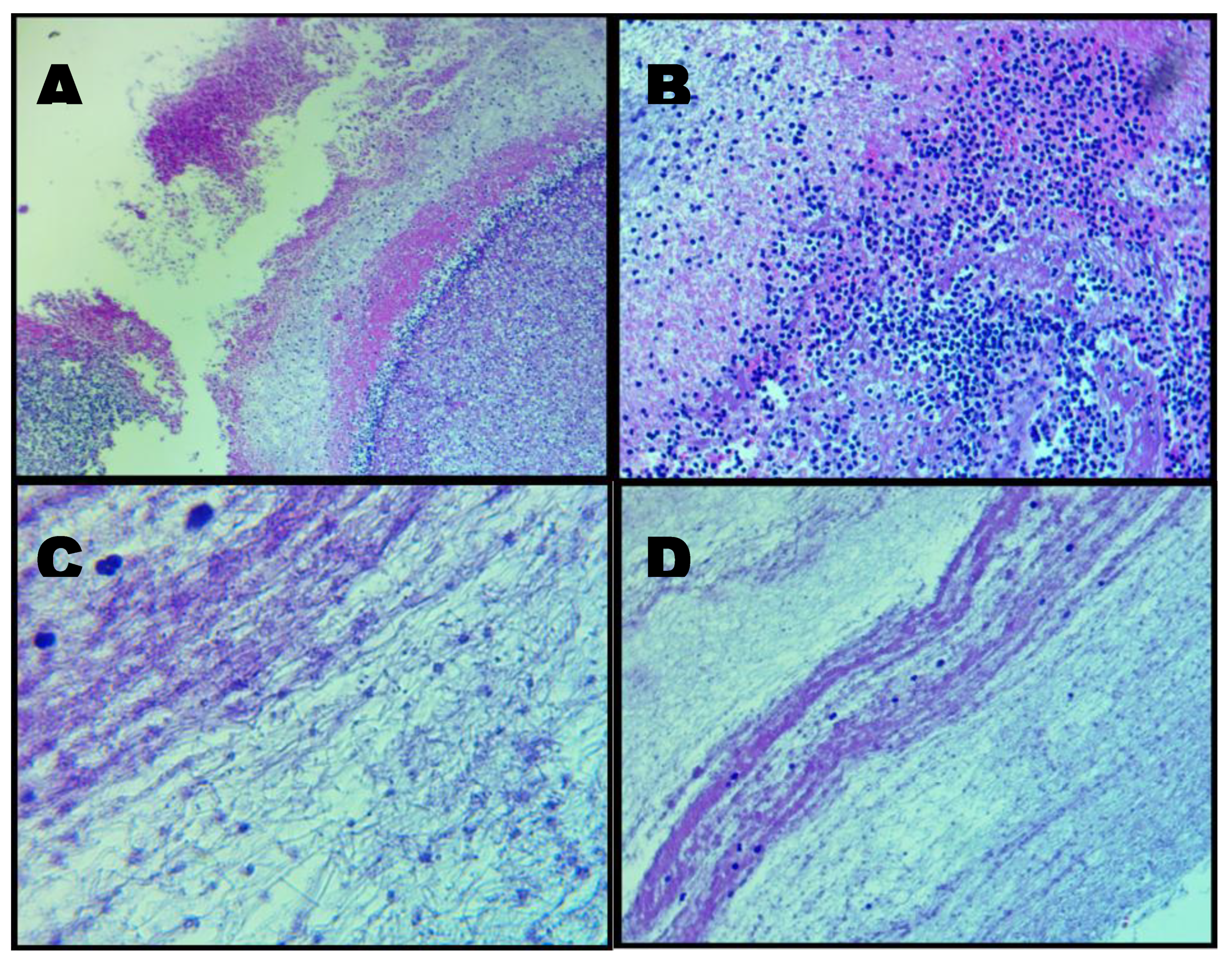

Figure 7.

Composite micrographs: Panel A. Low-magnification (40×) H&E overview demonstrating the heterogeneous architecture of the AIC specimen. Large paraffin-filled voids reflect internal channels or loss of unsupported material during microtomy, while surrounding regions show an irregular fibrinous matrix with variable cellular density. Panel B. Intermediate magnification (100×) highlighting heterogeneous distribution of cellular elements within a fibrin-dominant matrix. Hematoxylin-positive nuclei are scattered irregularly, and fine fibrillar strands support the sparse cellular content, indicating non-uniform microstructural organisation. Panel C. High-magnification (400×) micrograph showing densely interwoven fibrin bundles interspersed with distorted leukocytes exhibiting ruptured membranes and nuclear extrusion. Hemoglobin streaking is visible in regions of erythrocyte lysis, consistent with the absence of intact red blood cells. Panel D. High-magnification (400×) field illustrating non-homogeneous fibrin organisation, including banded zones reminiscent of partial Lines of Zahn. Cellular inclusion is minimal, and fibrin fibres display directional alignment suggestive of formation under variable shear conditions.

Figure 7.

Composite micrographs: Panel A. Low-magnification (40×) H&E overview demonstrating the heterogeneous architecture of the AIC specimen. Large paraffin-filled voids reflect internal channels or loss of unsupported material during microtomy, while surrounding regions show an irregular fibrinous matrix with variable cellular density. Panel B. Intermediate magnification (100×) highlighting heterogeneous distribution of cellular elements within a fibrin-dominant matrix. Hematoxylin-positive nuclei are scattered irregularly, and fine fibrillar strands support the sparse cellular content, indicating non-uniform microstructural organisation. Panel C. High-magnification (400×) micrograph showing densely interwoven fibrin bundles interspersed with distorted leukocytes exhibiting ruptured membranes and nuclear extrusion. Hemoglobin streaking is visible in regions of erythrocyte lysis, consistent with the absence of intact red blood cells. Panel D. High-magnification (400×) field illustrating non-homogeneous fibrin organisation, including banded zones reminiscent of partial Lines of Zahn. Cellular inclusion is minimal, and fibrin fibres display directional alignment suggestive of formation under variable shear conditions.

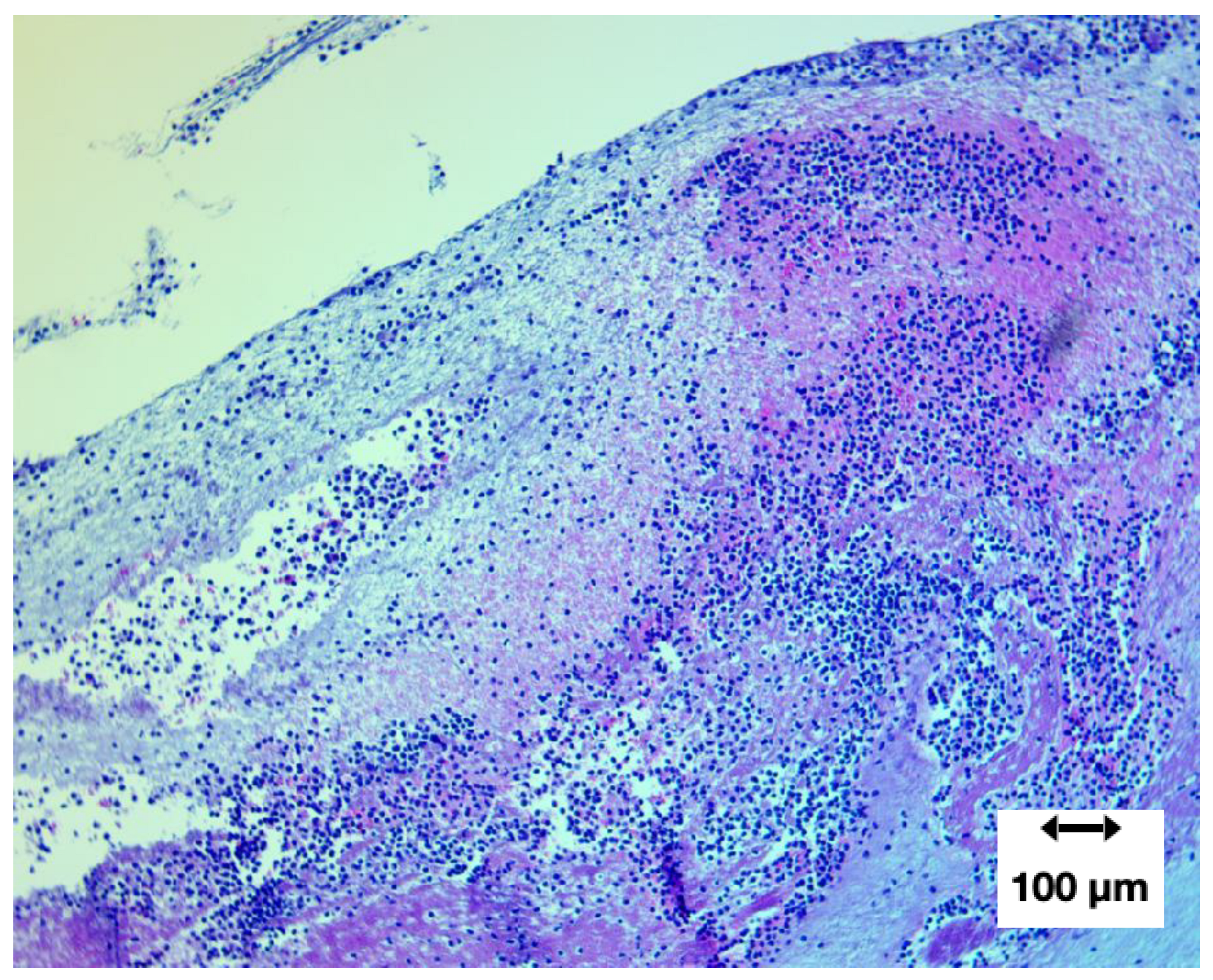

Low-magnification architecture (40×)

At 40× magnification, large void regions were evident, representing paraffin-filled gaps where the original material contained internal channels or where microtome sampling removed unsupported areas. Such paraffin voids are a routine artefact of FFPE processing and do not indicate loss of tissue or structural alteration within the clot itself.

A prominent curvilinear band of basophilic material—interpreted as densely aggregated cellular structures—was visible against a background of amorphous eosinophilic fibres.

Figure 8.

H&E-stained transverse section at 40× showing heterogeneous fibrinous architecture with variable cellular density.

Figure 8.

H&E-stained transverse section at 40× showing heterogeneous fibrinous architecture with variable cellular density.

Crimson-pink staining indicated extracellular hemoglobin released from lysed erythrocytes.

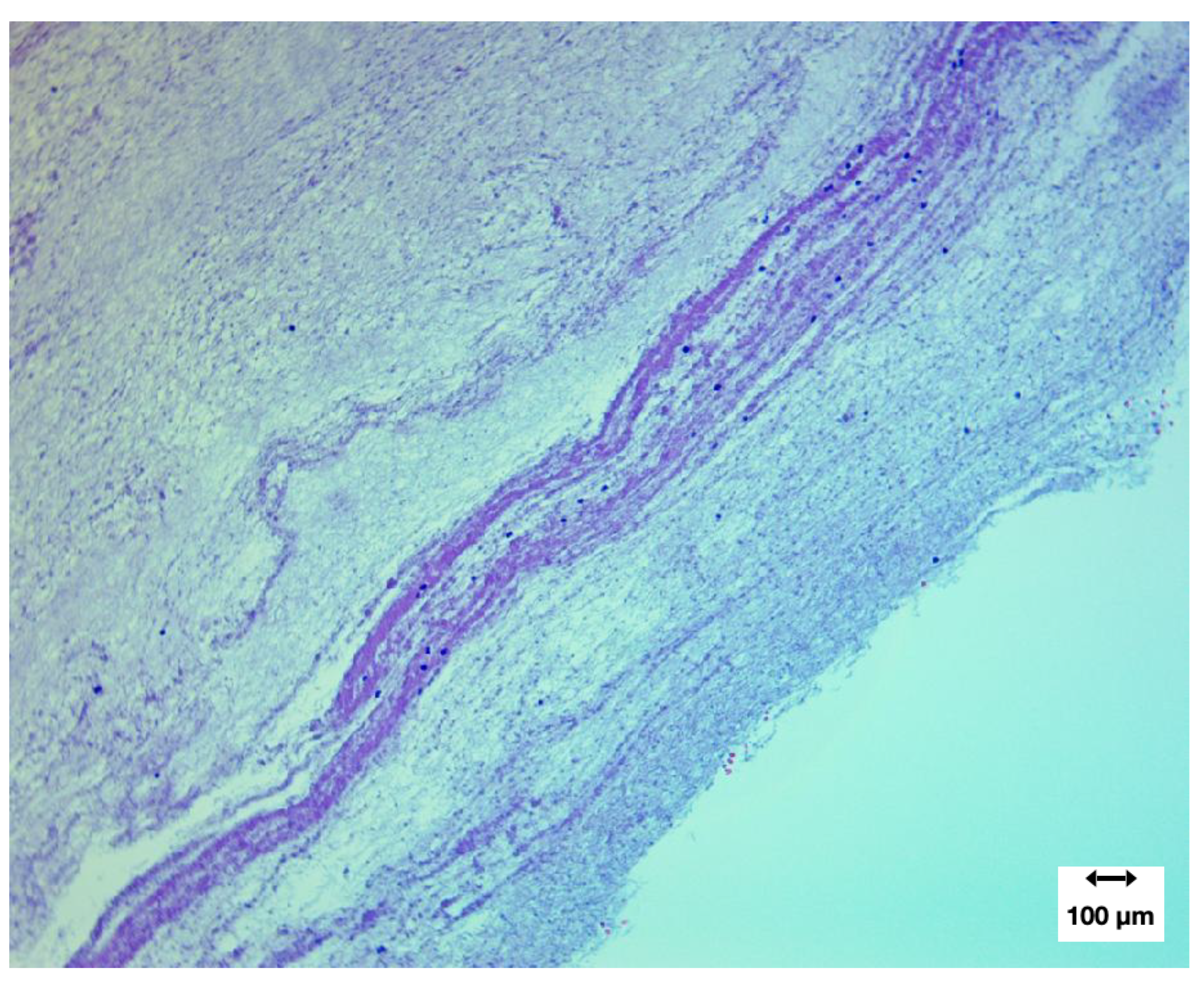

Intermediate magnification (100×)

At 100× magnification, heterogeneous cellular distribution became more apparent. Hematoxylin-positive nuclei were irregularly dispersed, with some regions densely cellular and others largely acellular.

A network of fine fibrillar strands spanned the tissue, supporting and anchoring cellular components. Variation in fibre density reflected differences in local cell abundance, not the absence of fibrin.

Figure 9.

H&E at 100× showing cellular heterogeneity within a fibrillar matrix.

Figure 9.

H&E at 100× showing cellular heterogeneity within a fibrillar matrix.

Lines of Zahn: presence and diagnostic significance

A defining feature of the specimen was the presence of Lines of Zahn—alternating pale (platelet/fibrin-rich) and darker (erythrocyte-rich) laminations formed under active blood flow and shear (Bancroft, 2019).

Their presence distinguishes antemortem thrombus formation from passive postmortem coagulation.

Figure 10.

H&E at 100× showing clear Lines of Zahn, confirming formation during active circulation (antemortem).

Figure 10.

H&E at 100× showing clear Lines of Zahn, confirming formation during active circulation (antemortem).

While Lines of Zahn appeared regionally limited rather than uniform, their presence provides strong evidence that these structures formed in vivo, at least in part, under flowing blood conditions.

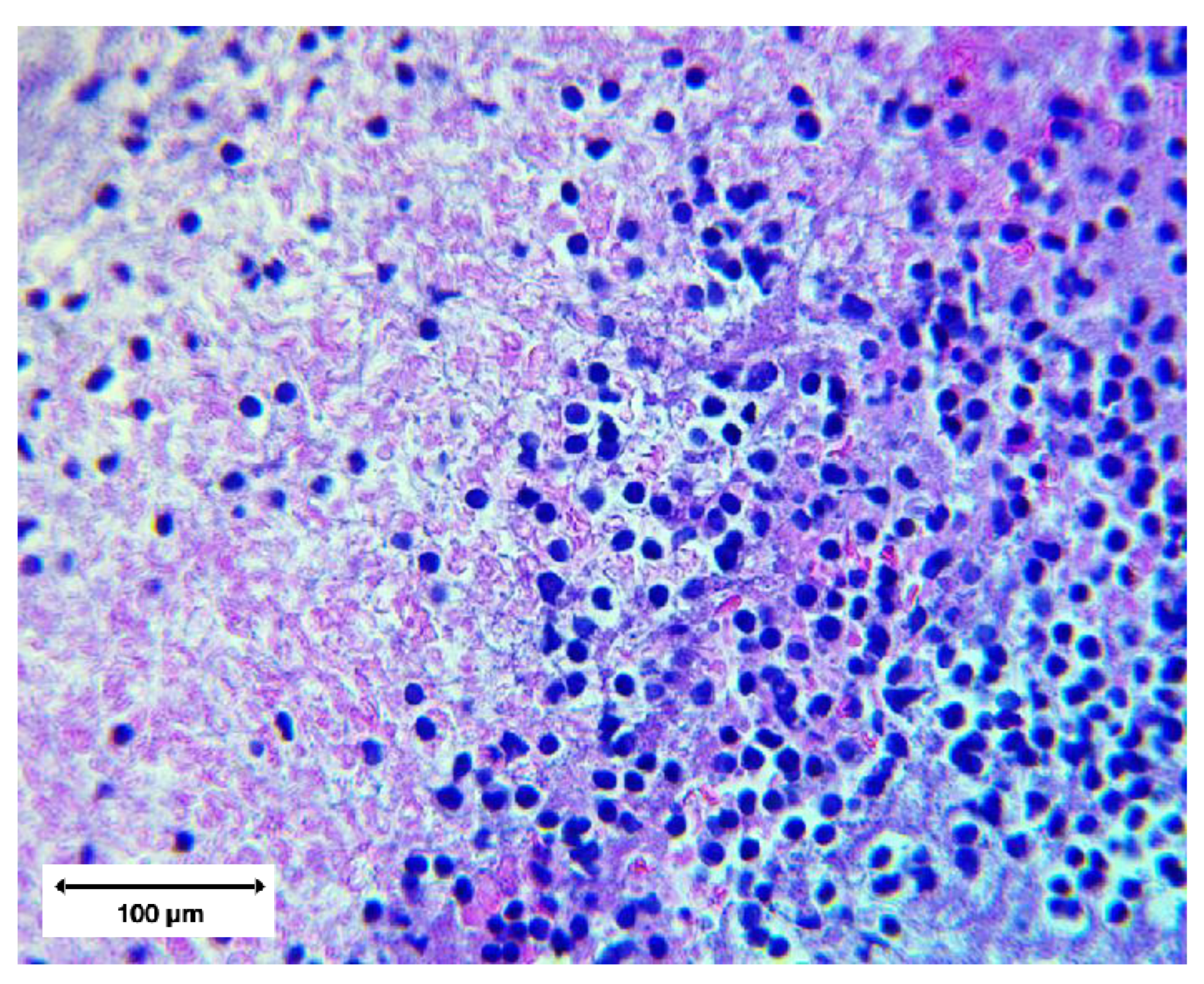

High magnification microstructure (400×)

At 400× magnification, the clot architecture revealed:

Interwoven fibrin strands forming dense, directionally aligned networks;

Distorted leukocytes with ruptured membranes, nuclear extrusion, and cytoplasmic leakage;

Hemoglobin streaking in regions of erythrocyte lysis, no intact erythrocytes were observed;

Marked regional variability across adjacent microscopic fields.

Figure 11.

H&E at 400× showing distorted leukocytes embedded in a dense fibrillar network.

Figure 11.

H&E at 400× showing distorted leukocytes embedded in a dense fibrillar network.

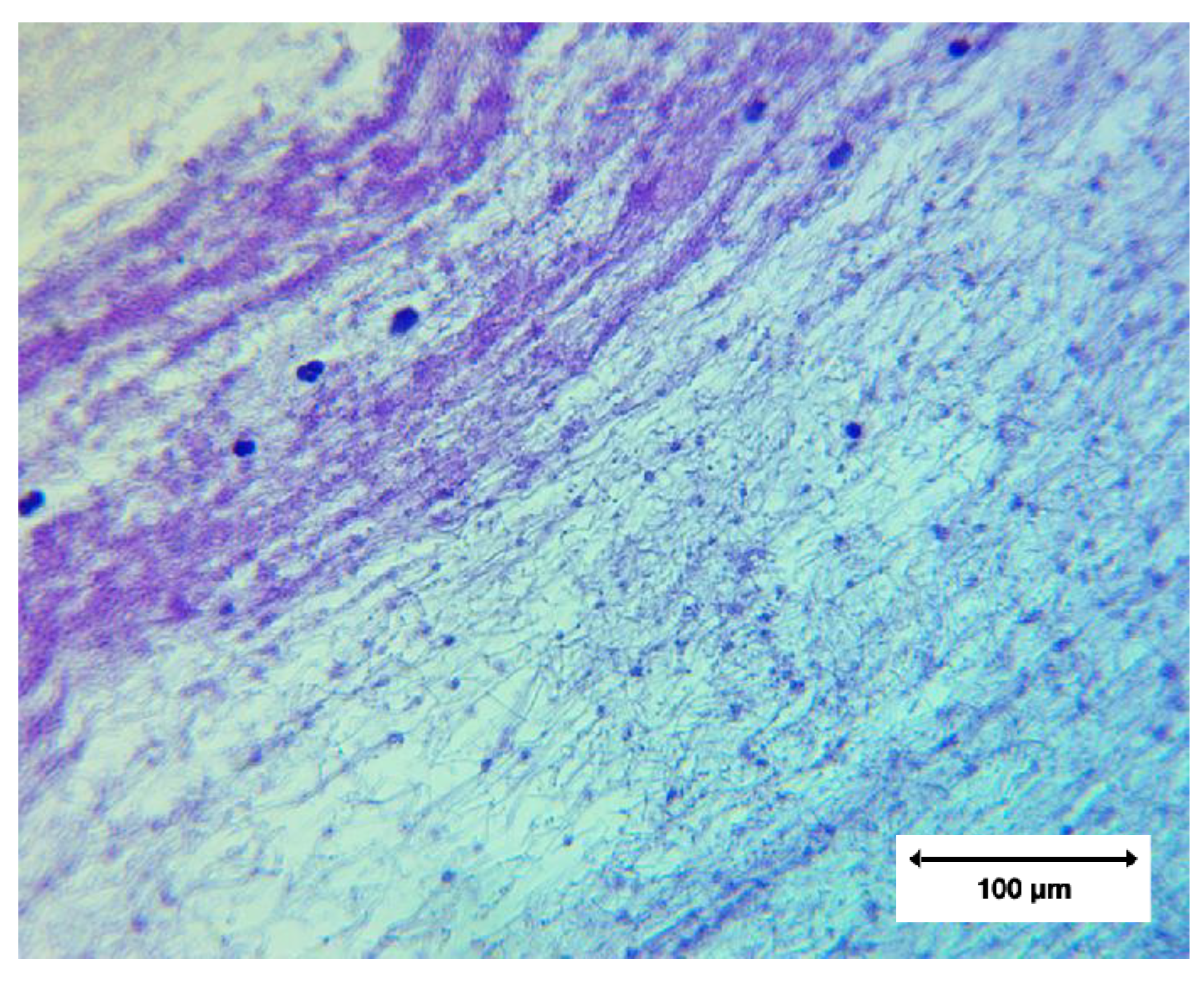

A separate field demonstrated banded fibrin architecture reminiscent of the Lines of Zahn but with decreasing fibre density outside the central laminated zones of fibrin protofibrils. (Fibrils were confirmed as fibrinoid by the third paper in this series which covers proteomics).

Figure 12.

H&E at 400× showing non-homogeneous fibrin organisation with minimal cellular inclusion.

Figure 12.

H&E at 400× showing non-homogeneous fibrin organisation with minimal cellular inclusion.

These high-magnification features collectively indicate:

Non-uniform fibrin assembly,

Heterogeneous shear conditions, and

Cellular stress or deformation during formation.

4.3. Summary of Morphological–Histological Phenotype

Across all analyses, AICs displayed a distinctive and internally consistent phenotype.

Key distinguishing features vs postmortem clots

Compared with chicken-fat and currant-jelly clots, AICs showed:

Persistent elasticity and tensile strength

Resistance to fragmentation/fibrinolysis

White/cream colour rather than red/yellow

Luminal conformity and branching

Absence of gelatinous texture

Partial but genuine Lines of Zahn

Structured fibrin networks with sparse cellular inclusion

No specimen resembled classical postmortem coagula.

Key distinguishing features vs antemortem thrombi

Relative to canonical antemortem thrombi, AICs showed:

Only partial Lines of Zahn (not continuous)

Very low cellular content (complete absence of intact erythrocytes)

Dense, homogeneous fibrin strands without normal layering

Coexistence of laminated and non-laminated zones

Atypical mechanical resilience

5. Discussion

5.1. Relation to Known Clot Types

Comparison with classical antemortem thrombi

The anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) documented in this study differ in several fundamental respects from recognised antemortem thrombi. Classical arterial or venous thrombi typically demonstrate prominent Lines of Zahn, extensive cellular entrapment, and a laminated structure reflecting repeated cycles of fibrin deposition and cellular incorporation under pulsatile flow (Bancroft, 2019). In contrast, the AIC specimens showed only partial or regionally restricted Lines of Zahn, and cellular inclusions were sparse, with many areas nearly acellular. Additionally, the AICs exhibited an unusual mechanical elasticity and tensile coherence not characteristic of fibrin-dominant thrombi.

Although the presence of partial lamination implies some formation under active circulation, the structural uniformity of the fibrin bundles, the minimal entrapment of erythrocytes and leukocytes, and the predominance of dense, homogeneous fibre networks collectively distinguish these casts from the classical thrombus phenotype.

Comparison with canonical postmortem clots

The differences between AICs and postmortem coagula were even more pronounced. Postmortem clots—whether “currant-jelly” or “chicken fat”—are gelatinous, friable, non-adherent, and lack flow-derived structures such as Lines of Zahn. They readily conform to the shape of the cavity in which they settle and commonly wash out during dissection. Because postmortem coagula lack cross-linked fibrin architecture and undergo passive sedimentation rather than active polymerisation, they cannot develop the elastic, tension-bearing properties observed in AICs. Importantly, no known postmortem interval changes or decomposition processes generate elastic, laminated, lumen-conforming structures, indicating that the features observed here cannot plausibly arise as postmortem artefacts. In sharp contrast, AICs were cohesive, elastic, lumen-conforming, and branched, retaining the geometry of the vascular tree. Their cutting resistance and documented acoustic emissions are incompatible with the physical properties of postmortem coagula.

Taken together, the morphological and histological evidence indicates that AICs do not fit within existing pathological descriptions of either antemortem thrombi or postmortem clots.

5.2. Biological Plausibility

Interpretation of lamination and fibre organisation

The presence of partial Lines of Zahn, even if regionally confined, provides evidence of at least some formation in vivo under flowing blood conditions. The fact that these laminations coexist with regions of dense, homogenised fibrin suggests that the formation environment may have included variable shear forces, intermittent flow, or localized stasis, producing a hybrid phenotype that departs from classical thrombotic evolution.

Sparse cellular content and implications for clot genesis

The consistently low density of entrapped erythrocytes and leukocytes is atypical for both arterial and venous thrombi, where cells are normally incorporated into the fibrin network as it forms. Such sparse cellularity may indicate:

Alterations in the availability or behaviour of circulating cells during clot formation,

Fibrin assembly occurring in an environment where cell adhesion or entrapment was reduced, or

Formation of a matrix dominated by polymerised protein with minimal cellular contribution.

The marked paucity of cellular elements also argues against a mechanism driven solely by ordinary in vivo thrombus occlusion, which typically generates markedly higher erythrocyte and leukocyte incorporation.

Although mechanistic conclusions cannot be drawn from morphology alone, the combination of elastic mechanical behaviour, dense fibrinous microarchitecture, and minimal cellular inclusion is biologically plausible as a distinct formation mode that differs from recognised thrombotic pathways.

Atypical hemodynamic conditions

The structural heterogeneity—alternating laminated, dense, and void-containing regions—suggests that AIC formation may involve non-canonical rheological conditions, potentially including localised turbulence, disrupted shear gradients, or a biochemical environment favouring atypical fibrin polymerisation.

While these hypotheses require biochemical validation, the observed morphology offers a consistent structural narrative compatible with formation under altered hemodynamic or biochemical states.

5.3. Limitations

Non-random sample sources

Samples analysed in this study were obtained from a waste stream and donated voluntarily by embalmers reporting unusual findings. As such, they do not represent a random or epidemiologically structured sample of the general population. The prevalence or distribution of AICs cannot be inferred from these data.

Retrospective and postmortem constraints

Because all specimens were obtained in postmortem settings, temporal information regarding the time of formation, location within the vasculature, and antecedent clinical conditions is unavailable. Although morphological indicators support antemortem formation for at least some portions of the casts, retrospective interpretation carries inherent limitations.

Restricted analytic modalities within this paper

The present study is limited to gross morphology and histology. Elemental composition and proteomic characterisation—essential for determining molecular mechanisms—are addressed in companion papers within this series.

Imaging and sampling artefacts

As with any histological study, voids and irregularities may reflect microtome interaction with heterogeneous or incompletely supported material. However, the consistency of observed architectural patterns across multiple laboratories mitigates this concern.

5.4. Implications and Future Research

Need for biochemical and mechanistic studies

The morphology–histology phenotype identified here—elastic, lumen-conforming, partially laminated, cellularly sparse, and mechanically resilient—infers important questions regarding the:

Biochemical composition of the fibrillar matrix,

presence or absence of ancillary proteins involved in clot stabilisation,

role of inorganic or trace elements in fibre structure, and

formation pathways that give rise to this unusual phenotype.

These questions are addressed directly in the elemental (Paper 2) and proteomic (Paper 3) companion studies.

Diagnostic and clinical relevance

If further validated, the structural features described here may prove diagnostically meaningful for distinguishing AICs from both postmortem clots and conventional thrombi. Such differentiation may be relevant for forensic analysis, pathological classification, and understanding atypical clotting phenomena observed in selected clinical reports.

Need for prospective studies

Prospective sampling—including intraoperative or intravascular retrieval when ethically feasible—would allow correlation of structural findings with clinical context, timing, and biochemical milieu. Controlled comparisons between AICs, classical thrombi, and postmortem coagula would further clarify their classification.

5.5. Potential Clinical and Public-Health Significance

The following considerations are exploratory and intended to frame hypotheses for future investigation rather than to assert population-level risk. The structural characteristics documented in these anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) raise important considerations for clinical medicine, pathology, and broader public health. While the present study does not investigate causation, the consistent morphology, mechanical resilience, and antemortem features observed across multiple independently processed samples indicate that AICs may represent a previously uncharacterised intravascular entity. Recognition of such an entity carries several implications.

Clinical relevance and differential diagnosis

If AICs occur during life—as suggested by the presence of partial Lines of Zahn and contemporary reports from surgical and catheterisation procedures—their physical properties could plausibly contribute to vascular obstruction, altered hemodynamics, or impaired tissue perfusion. Their elasticity, lumen conforming shape, and resistance to fragmentation imply that they may persist within the vasculature in ways not typical of ordinary thrombi. From a diagnostic perspective, distinguishing AICs from classic thrombi may prove important for:

Interpreting imaging or surgical findings,

guiding clinical decision-making when unexpected intraluminal material is encountered, and

understanding atypical clot presentations in patients with otherwise unexplained vascular compromise.

As awareness grows, clinicians and pathologists may need updated criteria to recognise and document these structures reliably.

Pathological classification and nosology

Current thrombus classifications—arterial, venous, septic, tumoural, or postmortem—do not accommodate the combined phenotype observed here: elastic, homogeneous, fibrous, low in cellular content, partially laminated, and organ-shaped. Establishing whether AICs reflect an extreme variant of fibrin-dominant thrombi or constitute a distinct pathological class is, therefore, a priority for future study.

The identification of a potential new clot type carries significant nosological value, as it may refine the taxonomy of intravascular pathology and encourage systematic reporting in forensic and medical settings.

Surveillance and epidemiological considerations

Because the samples analysed were contributed by embalmers and pathologists specifically reporting unusual findings, no prevalence estimates can be inferred. Nonetheless, the geographic breadth of such reports (Haviland, 2023, 2024; Worldwide Embalmer Blood Clot Survey, 2023) suggests the need for:

Prospective surveillance protocols,

standardised photographic and histological documentation, and

integration of AIC recognition into forensic guidelines.

Understanding when, where, and how often these structures occur will be essential for determining their population-level significance.

Implications for public health and biomedical science

The existence of a coherent, replicable morphological–histological phenotype not accounted for in existing thrombus models raises broader issues relevant to public health:

Are these casts associated with specific clinical syndromes, comorbidities, or physiological conditions?

Do they form rapidly or slowly, and under what biochemical milieu?

How could they not contribute to unexplained cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or microvascular events?

How may they be treated and prevented intros suffering or at-risk?

Addressing such questions requires interdisciplinary collaboration across pathology, haematology, biophysics, and epidemiology. The present findings argue for caution in dismissing field reports and for strengthening partnerships between frontline mortuary sciences, laboratory pathology and public health.

A framework for next-phase investigation

Given the limitations inherent in morphology and histology alone, a full understanding of AICs requires integration of:

Elemental composition (Paper 2);

proteomic architecture (Paper 3); and

clinical context from prospective case documentation.

Only with these components can the medical community determine whether AICs represent a:

Variant of known clotting phenomena;

new subtype of fibrin-dominant obstruction, or

distinct pathological entity with implications for vascular biology and public health.

6. Conclusion

The anomalous intravascular casts (AICs) characterized in this study exhibit a consistent set of morphological and histological features that distinguish them from both classical antemortem thrombi and postmortem coagula. Their elasticity, lumen-conforming geometry, cohesive fibre networks, sparse cellular composition, and partial but genuine Lines of Zahn collectively indicate a formation process that does not align with established thrombotic pathways. While morphology alone cannot determine causation, these reproducible features suggest that AICs may represent a previously unclassified intravascular entity.

6.1. Clinical and Diagnostic Significance

If AICs arise during life—as suggested by laminated regions and antemortem flow signatures—their unusual physical properties may influence vascular obstruction, hemodynamics, tissue perfusion and resistance to thrombolysis. Distinguishing these structures from ordinary thrombi could become clinically important when unexpected intraluminal material is encountered in surgical, catheterisation, or imaging contexts.

6.2. Pathological Relevance and Nosological Considerations

Traditional clot classifications do not account for the phenotype described here. The combination of elasticity, structural uniformity, dense fibrin networks, and minimal entrapped cells falls outside canonical descriptions of postmortem clots or mature thrombi. Recognition of this phenotype may warrant refinement of intravascular pathology frameworks and encourage systematic documentation in clinical and forensic settings.

6.3. Public-Health Implications

Although this study does not attempt to estimate prevalence, the global consistency of field reports underscores the need for structured surveillance and prospective documentation. Understanding the frequency, clinical associations, and potential risk factors for AIC formation will require collaboration between pathologists, clinicians, and public-health researchers.

6.4. Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Defining the biochemical composition and molecular architecture of AICs is essential for determining whether they reflect:

An extreme variant of fibrin-dominant thrombi,

a novel subtype of proteinaceous intravascular obstruction, or

a distinct pathological class with unique clinical implications.

These questions are addressed in the companion studies of this trilogy: Paper 2 (Elemental Composition) and Paper 3 (Proteomic Architecture).

Together, these investigations aim to build a comprehensive framework for understanding AICs, clarifying their pathophysiological significance, and guiding future diagnostic and research efforts in vascular biology and public health.