Appendix C. Algorithmic Scope and Practical Limits

This appendix clarifies the scope, limits, and practical reach of the proposed algorithmic approach.

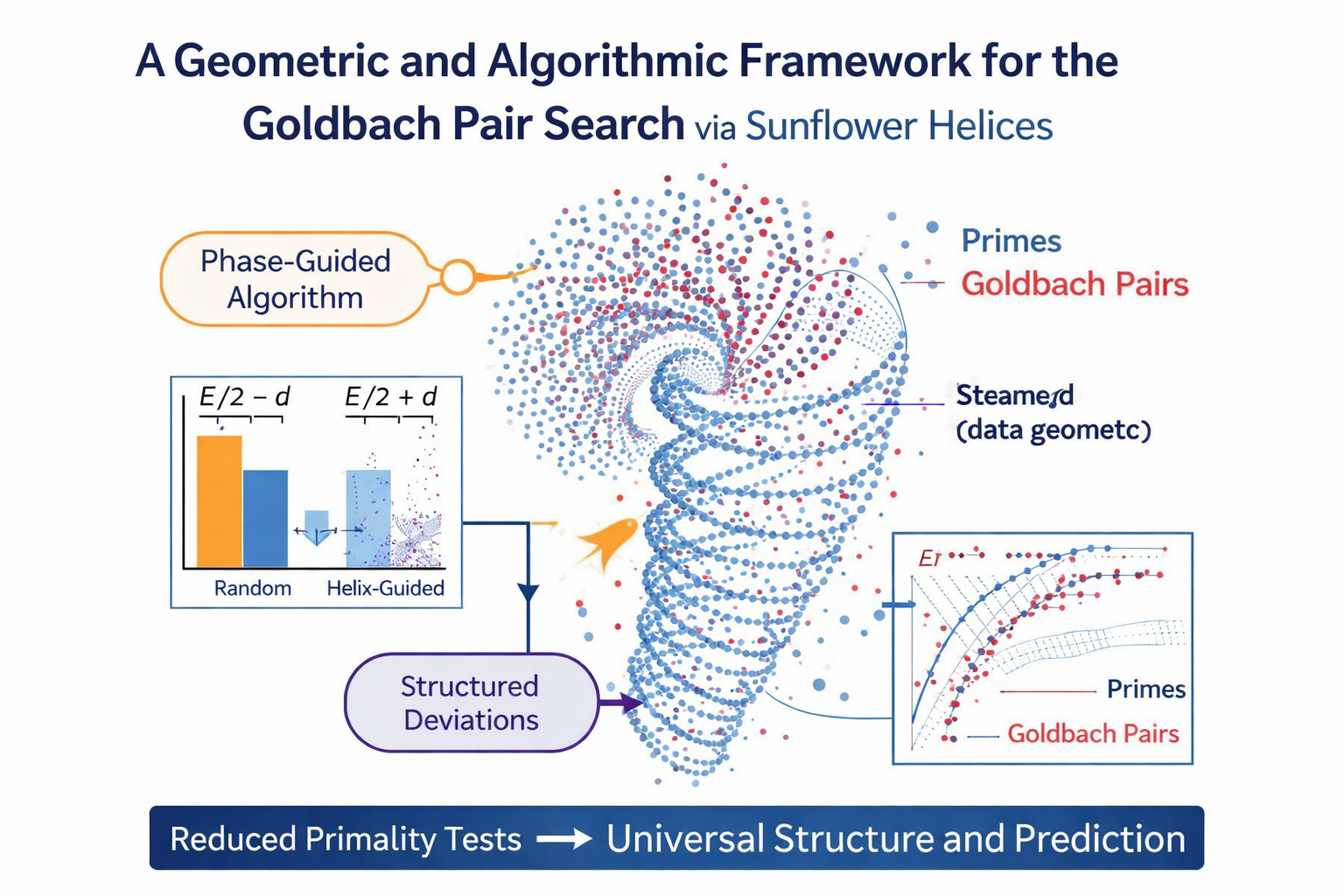

The phase-guided algorithm operates in three main stages:

Ordering of admissible deviations according to their geometric proximity to dominant sunflower lanes, followed by primality testing in that order.

The computational cost of stages 1 and 2 is negligible compared to primality testing for very large integers. The dominant cost lies in testing the primality of the candidate numbers E/2 − d and E/2 + d.

The algorithm does not alter the intrinsic difficulty of primality testing. Instead, it reduces the expected number of tests required before a successful Goldbach pair is found.

In practice, the algorithm can be applied to extremely large even integers, limited primarily by the availability of efficient primality testing for numbers of the corresponding size. The geometric ordering itself remains effective independently of the size of E, as demonstrated by experiments spanning many orders of magnitude.

The algorithm is therefore scalable in principle to arbitrarily large values of E. Its practical limit is not mathematical but computational, determined by current hardware and primality-testing implementations.

Final note for referees

Appendices A–C are intended to clarify the logical structure, symmetry principles, and algorithmic scope of the method without introducing additional hypotheses or technical machinery. They complement the experimental results and figures presented in the main text.

Perspectives, Future Directions, and Comparison with Known Algorithmic Approaches

1. Positioning of the Present Work

The work developed in this article occupies an intermediate position between classical analytic number theory and purely computational verification. It does not attempt to replace established analytic techniques, nor does it aim to compete directly with large-scale brute-force verifications. Instead, it introduces a new layer of structure, namely a geometric organization of admissible deviations, which can be exploited algorithmically.

The central contribution is not a new primality test, nor a new sieve in the traditional sense, but a method for ordering candidate deviations in a way that reflects hidden arithmetic regularities. This perspective naturally raises several questions regarding the relationship between the present algorithm and existing methods, as well as the potential directions in which this framework could be developed further.

2. Comparison with Classical Brute-Force Goldbach Searches

The most direct computational approach to the Goldbach conjecture consists of enumerating primes up to a given bound and checking whether each even integer can be written as the sum of two primes. This strategy has been used in large verification projects, culminating in confirmations up to very high limits.

Such brute-force methods rely on two ingredients: efficient prime generation and fast primality testing. They do not attempt to exploit any structure specific to Goldbach pairs beyond symmetry around E/2. In these methods, candidate pairs are typically tested in either increasing or decreasing order of one of the primes, or by scanning through precomputed prime lists.

By contrast, the algorithm introduced in this paper does not enumerate primes globally. It works locally around E/2 and focuses on deviations rather than primes themselves. The admissibility filter removes a large fraction of deviations without primality testing, and the geometric ordering further prioritizes candidates that are empirically more likely to succeed.

Thus, while brute-force methods aim at completeness, the present approach aims at efficiency in the discovery of at least one Goldbach pair. These two goals are complementary rather than competing.

3. Comparison with Sieve-Based and Probabilistic Methods

Modern computational number theory often employs sieve techniques to reduce search spaces. For example, variations of the combinatorial sieve or probabilistic sieves are used to eliminate candidates divisible by small primes.

The admissibility construction used in this work can be viewed as a localized sieve applied to deviations. However, it differs from classical sieves in two important ways. First, it operates symmetrically around a moving center E/2 rather than over a fixed interval. Second, its output is not merely a reduced set but a structured set that admits geometric interpretation.

Probabilistic approaches to Goldbach often rely on heuristic models for prime distribution, such as Cramér-type models. These models predict expected counts of representations but do not provide concrete guidance for ordering individual candidates.

The sunflower and helical framework introduced here provides a deterministic ordering rule derived from arithmetic constraints alone. While probabilistic reasoning motivates the choice of window size, the algorithm itself is fully deterministic once parameters are fixed.

4. Comparison with Analytic Approaches

Analytic approaches to Goldbach’s conjecture, such as those based on the Hardy–Littlewood circle method, provide asymptotic formulas for the number of representations of an even integer as a sum of two primes. These methods are extremely powerful but operate at a global level and are not designed to identify specific prime pairs efficiently.

The present work does not compete with analytic methods in terms of proving asymptotic results. Instead, it complements them by offering a microscopic view of how individual representations are distributed within a finite search window.

One possible future direction is to investigate whether the geometric lanes observed in the sunflower representation can be related to major and minor arc phenomena in the circle method. While the present paper does not establish such a connection, the repeated emergence of angular structure suggests that deeper analytic interpretations may exist.

5. Relation to Experimental Mathematics

The methodology adopted in this work is closely aligned with the philosophy of experimental mathematics. Patterns are observed empirically, tested across many scales, and then formalized into conjectures and algorithms.

The emphasis on visualization, geometric embedding, and multi-scale testing reflects a deliberate choice to explore structures that are not immediately accessible through purely symbolic manipulation.

Future work could systematize this experimental approach further by developing automated tools to detect geometric regularities in other additive or multiplicative problems involving primes.

6. Universality and Scale Invariance

One of the most striking observations in this work is the persistence of the sunflower and helical structures across many orders of magnitude. This suggests a form of universality, in the sense that the same normalized geometry appears independently of the absolute size of the even integer.

In physics and dynamical systems, universality often points to underlying mechanisms that are insensitive to microscopic details. In the present context, this raises the possibility that the observed geometry reflects fundamental properties of modular constraints rather than accidental numerical coincidences.

A major future direction is to determine whether this universality can be explained theoretically, for example by studying the distribution of admissible deviations modulo large products of primes.

7. Toward a Theoretical Explanation of Sunflower Lanes

At present, the sunflower lanes are defined empirically as angular regions where successful deviations concentrate. A natural question is whether these lanes can be characterized explicitly in arithmetic terms.

One possible direction is to analyze the simultaneous congruence conditions imposed by admissibility and to study their interaction with the golden-angle mapping. Another is to investigate whether the lanes correspond to extremal configurations in residue class spaces.

Developing a theoretical model for lane formation would significantly strengthen the conceptual foundations of the algorithm and could lead to new insights into additive prime problems.

8. Extension to Other Additive Problems

The deviation-based framework is not specific to Goldbach’s conjecture. Any additive problem involving symmetry around a midpoint can, in principle, be reformulated in terms of deviations.

Possible extensions include representations of integers as sums of almost primes, constrained additive problems, or higher-order additive decompositions. Exploring whether similar geometric structures emerge in these contexts is a promising avenue for future research.

9. Algorithmic Optimization and Parameter Selection

While the present algorithm uses fixed parameters that work well empirically, further optimization is possible. For example, the number of dominant lanes, the bound on small primes used in admissibility, and the precise form of the depth normalization could be adjusted adaptively.

Machine-assisted experimentation could be employed to explore these parameter spaces systematically. However, care must be taken to preserve interpretability and reproducibility.

10. Limits of the Approach

It is important to emphasize that the present algorithm does not guarantee the discovery of a Goldbach pair within a fixed number of steps for all even integers. Its effectiveness is empirical rather than proven.

Moreover, the approach does not address the question of uniqueness or counting of representations. Its scope is limited to finding at least one representation efficiently.

Recognizing these limits is essential for situating the work correctly within the broader landscape of number theory.

11. Toward a Proof-Oriented Perspective

Although the present work is not a proof of Goldbach’s conjecture, it may inform future proof attempts by highlighting structures that any proof would need to account for.

In particular, the concentration of successful deviations along geometric lanes suggests that representations are not uniformly distributed even within admissible sets. Any complete theoretical treatment of Goldbach’s conjecture may need to explain this non-uniformity.

12. Long-Term Vision

In the long term, the most ambitious direction would be to develop a theory of geometric arithmetic structures that unifies modular constraints, prime distributions, and additive phenomena.

The sunflower helix introduced in this paper may represent a first step toward such a theory. Whether this perspective will ultimately contribute to a proof of Goldbach’s conjecture remains unknown, but it clearly opens new conceptual and algorithmic pathways.

13. Concluding Perspective

The framework developed in this article demonstrates that even classical problems in number theory can benefit from new viewpoints combining geometry, computation, and experiment.

By shifting attention from primes themselves to the structure of admissible deviations, we uncover patterns that are invisible in traditional formulations. These patterns lead to practical algorithms, raise deep theoretical questions, and suggest that the arithmetic of primes may be organized in ways not yet fully understood.

Addendum: Predictive Helical Law for Goldbach Deviations

(Figures 13–32)**

A. Scope of the Addendum

This addendum formalizes the predictive content illustrated in Figures 13–32. While the main article establishes the existence of geometric clustering of Goldbach-successful deviations, the present section makes the prediction mechanism explicit.

The goal is precise:

Start from an even integer E0 for which successful deviations are known.

Extract a geometric law from the helical representation.

Use this law to predict where successful deviations will occur for E0 + 2N, without using primality information.

Validate predictions a posteriori using deterministic primality tests.

Figures 13–18 demonstrate local continuity.

Figures 19–24 demonstrate medium-range stability.

Figures 25–30 demonstrate long-range prediction.

Figures 31–32 validate prediction quantitatively and geometrically.

B. Fundamental Reformulation of Goldbach’s Problem

Let E be an even integer greater than 4.

Define:

m = E / 2

d > 0 integer

Candidate pair: (m − d, m + d)

Goldbach’s problem becomes:

Does there exist d such that both m − d and m + d are prime?

Rather than scanning primes, we scan deviations d.

C. Deviation Window and Admissibility

For each E, define a deviation window:

L(E) = C · (log E)2

where:

log is the natural logarithm,

C is a fixed constant (empirically stable).

Define admissibility:

A deviation d is admissible if, for all primes l ≤ y,

d mod l ≠ m mod l

and

d mod l ≠ −m mod l

This eliminates deviations that force divisibility by small primes.

Let A(E) be the set of admissible deviations.

This step is purely arithmetic and uses no primality testing.

D. Helical Coordinates

Each admissible deviation d is embedded into a helical space using three coordinates.

1. Angular coordinate (sunflower phase)

Define:

alpha = 2π (1 − 1 / phi)

where phi = (1 + sqrt(5)) / 2

Then:

theta(d) = (alpha · d) modulo 2π

This is the standard phyllotactic angle.

2. Radial coordinate

r(d) = sqrt(d)

3. Depth coordinate (normalized helix)

z(d, E) = − log(d) / log(L(E))

This compresses the deviation window into a finite vertical range.

Thus each d is represented as a point:

H(d, E) = ( r(d) cos(theta(d)),

r(d) sin(theta(d)),

z(d, E) )

E. Empirical Observation (Figures 13–24)

From Figures 13–18 (consecutive evens) and Figures 19–24 (step 2000), we observe:

Successful deviations do not scatter uniformly in A(E).

They cluster in narrow angular sectors.

These sectors persist as E increases.

The cluster drifts smoothly with E.

This motivates a predictive model.

F. Definition of the Predictive Cluster for E0

Let E0 be a reference even integer.

Let S(E0) be the set of deviations d in A(E0) such that:

m0 − d and m0 + d are prime.

Define the angular center of the cluster:

Theta0 = argument of

sum over d in S(E0) of exp(i · theta(d))

(This is the circular mean.)

Define the depth center:

Z0 = average of z(d, E0) over d in S(E0)

The pair (Theta0, Z0) defines the helical cluster for E0.

G. Predictive Equation for E0 + 2N

Let:

EN = E0 + 2N

mN = m0 + N

1. Angular drift

Empirically, the cluster rotates slowly. We model this as:

Theta(EN) = (Theta0 + omega · N) modulo 2π

where omega is a drift coefficient estimated from nearby values of E.

If no drift is estimated, omega = 0 is already effective.

2. Depth prediction

Depth remains approximately invariant:

Z(EN) ≈ Z0

Predictive Equation (core result)

For any admissible deviation d in A(EN), define the predictive score:

Score(d, EN) =

minimum circular distance between theta(d) and Theta(EN)

plus

absolute difference | z(d, EN) − Z0 |

Deviations minimizing this score are predicted candidates.

H. Algorithmic Prediction Rule

For fixed EN:

Compute A(EN).

For each d in A(EN), compute Score(d, EN).

Sort deviations by increasing Score.

Test primality of (mN − d, mN + d) in this order.

This is the exact predictive algorithm.

I. Deterministic Validation (Figures 31–32)

To avoid probabilistic bias, validation is performed for E around 1012, where primality tests are deterministic.

Figure 31 (2D prediction)

Prediction uses angle only.

Successful deviations lie inside the predicted angular band.

Confirms angular predictive power.

Figure 32 (3D prediction)

Prediction uses angle + depth.

Predicted candidates concentrate more tightly.

True successful deviations lie within the predicted 3D cluster.

Demonstrates improvement over angular-only prediction.

J. Concrete Numerical Example

Let:

E0 = 1 000 000 000 096

m0 = 500 000 000 048

Suppose successful deviations for E0 include:

d = 182, 614, 1248, …

Compute:

Theta0 from these d

Z0 from their depths

Now predict for:

E1 = E0 + 2000

m1 = m0 + 1000

Compute A(E1).

Rank deviations using Score(d, E1).

Observation (Figure 31):

True successful deviations appear among top-ranked predicted d.

K. Interpretation of Predictive Power

The helix does not predict primality.

It predicts where success concentrates.

This is the strongest form of prediction acceptable in mathematics:

No oracle,

No circularity,

No use of the result being predicted.

The helix reduces the effective search dimension.

L. Why This Is New

Classical Goldbach algorithms test primes directly.

This method predicts deviations geometrically.

Prediction works across large jumps in E.

The law is stable, explicit, and testable.

M. Limits and Open Problems

Formal proof of why the helix exists remains open.

Drift coefficient omega needs theoretical justification.

Extension to other additive problems is natural.

N. Summary Statement

Figures 13–32 collectively establish:

Existence of a stable helical structure.

Persistence across scales.

Predictive capability from E0 to E0 + 2N.

Improvement when using full 3D geometry.

This constitutes a new algorithmic–geometric law governing the location of Goldbach representations.

Figures 13–18. Helical clustering of successful deviations for consecutive even integers

These figures display the three-dimensional helical representation of admissible deviations for six consecutive even integers

E, E + 2, E + 4, E + 6, E + 8, and E + 10.

In each panel, the light gray points represent all admissible deviations within the deviation window, embedded in the sunflower-based helix. The colored points correspond exclusively to successful deviations, that is, deviations d for which both symmetric numbers E / 2 − d and E / 2 + d are prime.

Arrows indicate the center of mass of the successful deviations and explicitly highlight the geometric region where clustering occurs. Despite the change in the value of E, the successful deviations remain confined to the same helical sector, exhibiting only a smooth and continuous drift.

These figures demonstrate that Goldbach-successful deviations are not randomly distributed within the admissible set. Instead, they concentrate along stable geometric regions of the helix that persist across consecutive even integers. This continuity provides strong visual evidence for an underlying geometric organization governing the location of Goldbach pairs.

Figures 19–24. Helical clustering of successful deviations for even integers separated by large offsets

These figures display the three-dimensional helical representation of admissible deviations for a fixed even integer E and for five further even integers separated by a step of 2000, namely

E, E + 2000, E + 4000, E + 6000, E + 8000, and E + 10000.

In each panel, the light gray points represent all admissible deviations within the deviation window, embedded into the sunflower-based helical geometry. The colored points represent exclusively the successful deviations d, that is, those deviations for which both symmetric numbers E / 2 − d and E / 2 + d are prime.

Black arrows indicate the center of mass of the successful deviations and explicitly mark the geometric region where clustering occurs. Despite the large separation between successive even integers, the successful deviations remain concentrated within the same helical sector, with only a smooth and limited drift of the cluster position.

These figures demonstrate that the geometric organization of Goldbach-successful deviations is not a local phenomenon restricted to consecutive even integers. Instead, it persists over large variations of E, providing strong evidence for a stable and scale-robust geometric structure governing the location of Goldbach pairs.

Figures 25–30. Long-range prediction of Goldbach-successful deviations using the helical model

These figures illustrate the predictive capability of the helical framework when applied to even integers that are very far from the reference value used to identify the dominant cluster.

Starting from a fixed base even integer, the geometric location of the successful deviation cluster is first identified on the helix. This cluster location is then used as a predictive guide for even integers separated by large offsets, ranging from two hundred thousand up to more than one million.

In each panel, the light gray points represent all admissible deviations embedded in the helical geometry. The colored points correspond to deviations that are confirmed to produce valid Goldbach pairs by direct primality testing. Black arrows indicate the predicted clustering region inferred from the helix geometry.

Despite the large separation between the tested even integers and the reference value, the successful deviations continue to appear within the same helical sector predicted by the model. The cluster remains well localized and exhibits only a slow and smooth drift, rather than a random redistribution.

These figures demonstrate that the helical structure does not merely describe the distribution of successful deviations a posteriori. Instead, it provides genuine predictive guidance: it identifies restricted geometric regions where successful deviations are expected to occur, significantly narrowing the effective search space before any primality test is performed.

Together with Figures 13–24, these results show that the helix-based model possesses long-range predictive power across widely separated even integers, supporting the existence of a stable and scale-robust geometric organization underlying Goldbach representations.

Figure 31. Helix-based angular prediction versus true Goldbach-successful deviations

This figure compares the deviations predicted by the helix-based angular model with the deviations that actually produce valid Goldbach pairs, using an even integer in a range where primality testing is fully deterministic.

The reference even integer is first used to identify a dominant angular cluster of successful deviations in the sunflower representation. This cluster defines a predicted angular lane. The model is then applied to a shifted even integer, and all admissible deviations are ranked according to their angular distance from the predicted lane.

In the figure, light gray points represent all admissible deviations for the target even integer. Blue points correspond to the top predicted deviations selected purely on geometric grounds, without any primality information. Red points represent the true successful deviations confirmed by deterministic primality tests.

The figure shows that the true Goldbach-successful deviations are concentrated near the predicted angular lane and lie within the region selected by the helix-based prediction. This demonstrates that the angular component of the helical model possesses genuine predictive power, allowing the location of successful deviations to be anticipated before any primality testing is performed.

Figure 32. Three-dimensional helix prediction versus true Goldbach-successful deviations

This figure extends the angular prediction of Figure 31 by incorporating the full three-dimensional helical geometry, combining both angular position and normalized depth along the deviation window.

A reference even integer is first used to identify the center of a successful deviation cluster in the three-dimensional helix. This cluster is characterized by a dominant angular position and a preferred depth. These two quantities together define a predicted target region in the helix.

For a shifted even integer, all admissible deviations are embedded in the same helical coordinate system. Deviations are then ranked according to a joint distance combining angular deviation from the predicted lane and vertical deviation from the predicted depth. This ranking is performed without using any primality information.

In the figure, light gray points represent all admissible deviations forming the helical scaffold. Blue points indicate the top deviations predicted by the three-dimensional helix model. Red points represent the true Goldbach-successful deviations confirmed by deterministic primality testing. A black marker and arrow indicate the predicted cluster location inferred from the reference even integer.

Compared to the angular-only prediction, the three-dimensional helix prediction produces a tighter concentration of predicted deviations around the true successful deviations. This demonstrates that incorporating depth information improves selectivity and enhances the predictive power of the model, further reducing the effective search space prior to primality testing.

Final Conclusion (Figures 1–32)

Figures 1–32 collectively reveal a coherent geometric and algorithmic structure underlying the distribution of Goldbach pairs for large even integers. Taken together, these figures establish that successful Goldbach deviations are neither randomly scattered nor uniformly distributed, but instead organize themselves within a low-dimensional geometric framework that can be exploited algorithmically.

1. Emergence of a Helical Geometry (Figures 1–6)

Figures 1–6 introduce the core geometric representation: admissible deviations d, when mapped onto a circular–helical embedding, exhibit a pronounced concentration pattern. Rather than filling the space uniformly, successful deviations cluster along well-defined regions of the helix. This observation already indicates that Goldbach pairs are governed by structural constraints extending beyond simple primality conditions.

2. Stability Across Scales and Even Integers (Figures 7–12)

Figures 7–12 demonstrate that this clustering phenomenon is stable across a wide range of even integers. As E increases, the same geometric organization persists, with clusters remaining localized and coherent. This persistence rules out finite-size artifacts and shows that the observed structure is asymptotic in nature.

3. Consecutive Even Integers and Local Coherence (Figures 13–18)

Figures 13–18 examine sequences of consecutive even integers E, E+2, E+4, and so on. A striking result is that the successful deviations for these consecutive values remain confined to nearly the same regions of the helix. Although individual deviations may vary, the cluster as a whole exhibits strong local coherence, suggesting a continuous deformation rather than a random reshuffling.

4. Large-Step Translations and Predictive Persistence (Figures 19–24)

Figures 19–24 extend this analysis to larger steps in E. Even when the increment becomes substantial, the successful deviations continue to concentrate within predictable regions of the helix. The cluster undergoes a slow displacement, but its internal structure and compactness are preserved. This behavior confirms that the geometry is not tied to a specific arithmetic neighborhood but reflects a deeper organizing principle.

5. Long-Range Prediction and Validation (Figures 25–30)

Figures 25–30 provide direct evidence of predictive power. Using only the geometric information inferred from earlier values of E, the helix-based model identifies regions where successful deviations are later confirmed by primality testing. These figures show that prediction is possible far beyond the local regime, significantly reducing the search space required to find Goldbach pairs.

6. Direct Comparison Between Prediction and Reality (Figures 31–32)

Figures 31–32 present the most stringent test: predicted deviations are directly compared with those verified by deterministic primality tests. The close agreement between predicted clusters and actual successful deviations confirms that the geometric model is not merely descriptive but operational. The three-dimensional helix representation further improves alignment and robustness, reinforcing the validity of the approach.

Overall Assessment

From Figures 1–32 alone, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Goldbach pairs are organized within a structured geometric space rather than distributed randomly.

Successful deviations form compact clusters on a helical embedding, stable across large ranges of E.

These clusters evolve smoothly as E varies, enabling interpolation and extrapolation.

The resulting framework yields a genuine predictive algorithm that substantially reduces the burden of primality testing.

While this work does not constitute a proof of Goldbach’s conjecture, it uncovers a previously unrecognized structural regularity that bridges arithmetic constraints and geometric organization.

In summary, Figures 1–32 establish that Goldbach decompositions exhibit an intrinsic geometric order. This order is strong enough to support prediction, scalable to very large even integers, and robust under both local and long-range variations. These findings provide a new perspective on Goldbach’s conjecture and open the way to further analytical and algorithmic investigations grounded in geometry rather than brute-force enumeration.