Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

23 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Digital Twins

International Digital Twin Case Studies

3. Data Exchange

3.1. Metadata

- Data format (syntactic)—is the data JSON, XML, etc.?

- What is this data? e.g. Temperature in degrees Celsius.

- Timestamp—when was the data recorded/apply to?

- ID—which device/sensor produced this data?

- Location—where was this data recorded? Important for georeferencing.

3.2. Comparisons Between Data Exchange Formats: JSON Vs XML

3.3. Internet-of-Things (IoT)

- Interoperability—there are a plethora of communication protocols and data formats that make it difficult for devices to collaborate.

- Security—due to the connected nature of IoT devices they are exposed to possible cyberattacks.

- Privacy—IoT devices often collect personal and sensitive data.

- Scalability—as the number of IoT devices in the system increases, there is additional device management, network traffic and data to be processed.

- Data Management—IoT devices may generate large amounts of data that need to be processed, stored and analysed.

4. Data Exchange for Digital Twins

5. Data Governance

- Data Security: Protect sensitive information from unauthorised access, breaches, and tampering.

- Data Privacy: Comply with regulations (e.g., GDPR) to protect individuals’ data and ensure lawful data handling.

- Data Integrity: Ensure that data exchanged among DTs is accurate, consistent, and reliable.

- Transparency and Accountability: Define clear roles and responsibilities for data ownership, processing, and oversight.

- Interoperability and Standards: Establish protocols and standards to enable seamless data exchange between heterogeneous systems.

- Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): a fundamental mechanism that ensures only authorised users or systems can access specific data. It enforces access rules based on predefined roles and responsibilities.

- Blockchain for Security and Traceability: provides tamper-proof, decentralised ledger capabilities to enhance trust and security in data transactions.

- Data Quality Management: Ensuring high-quality data is critical for the effectiveness of DTs. Poor-quality data can lead to flawed decision-making and loss of stakeholder trust.

- Privacy Preserving Mechanisms: FDTs often handle sensitive personal or operational data, making privacy a top priority.

- Interoperability and Standardisation: For a federated system to function effectively, it must facilitate data exchange among DTs, each potentially operating on different standards and formats.

- Data Encryption: ensures that data remains secure during transmission and storage.

- Data Life Cycle Management: Governance policies should address how data is created, shared, stored, archived, and ultimately deleted.

- Monitoring and Auditing: Continuous monitoring ensures the platform remains compliant and secure.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Training: The success of data governance relies on informed and engaged stakeholders.

5.1. Governance Recommendations

- Data Sovereignty Compliance: Ensure all governance policies align with UK-specific regulations on data sovereignty and public sector data sharing.

- Regular Review and Updates: Establish a governance review cycle to adapt to emerging technologies, regulations, and city needs.

- Transparency with Citizens: Develop public-facing documentation to explain how data is collected, used, and protected, fostering trust in the system.

5.2. Role-Based Access Levels for the FDT Platform

6. Interoperability for Digital Twins

| Level | Type | Description | Common Premise |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Conceptual | Interoperating systems at this level are completely aware of each others information, processes, contexts, and modeling assumptions. | conceptual model |

| 5 | Dynamic | Interoperating systems are able to re-orient information production and consumption based on understood changes to meaning, due to changing context as time increases. | execution model |

| 4 | Pragmatic | Interoperating systems will be aware of the context (system states and processes) and meaning of information being exchanged. | workflow model |

| 3 | Semantic | Interoperating systems are exchanging a set of terms that they can semantically parse. | reference model |

| 2 | Syntactic | Have an agreed protocol to exchange the right forms of data in the right order, but the meaning of data elements is not established. | data structure |

| 1 | Technical | Have technical connection(s) and can exchange data between systems | communication protocol |

| 0 | None | N/A | N/A |

- What level of interoperability do we require?

- What information on the data from a DT (i.e., metadata) do we require for the required level?

- Does that metadata need to be in the data exchange format for discoverability?

6.1. OASC MIMs

6.2. Semantic Interoperability

6.2.1. Semantic Annotation

6.2.2. Semantic Queries and Reasoning

6.2.3. Limitations of Ontologies for Smart Cities

7. Approaches to Semantic Interoperability

- i)

- reusing standard ontologies, e.g., SOSA/SSN6 for sensor networks and actuators

- ii)

- defining their own monolithic smart-city ontology, e.g., STAR-CITY, CityPulse.

7.1. Semantic Technologies Useful in the Smart City Context

7.1.1. JSON

7.1.2. RDF

7.1.3. Linked Data

7.1.4. JSON-LD

7.1.5. GeoJSON

7.1.6. CityGML

7.1.7. Other OGC Standards

7.1.8. Smart Data Models10

7.1.9. DTDL

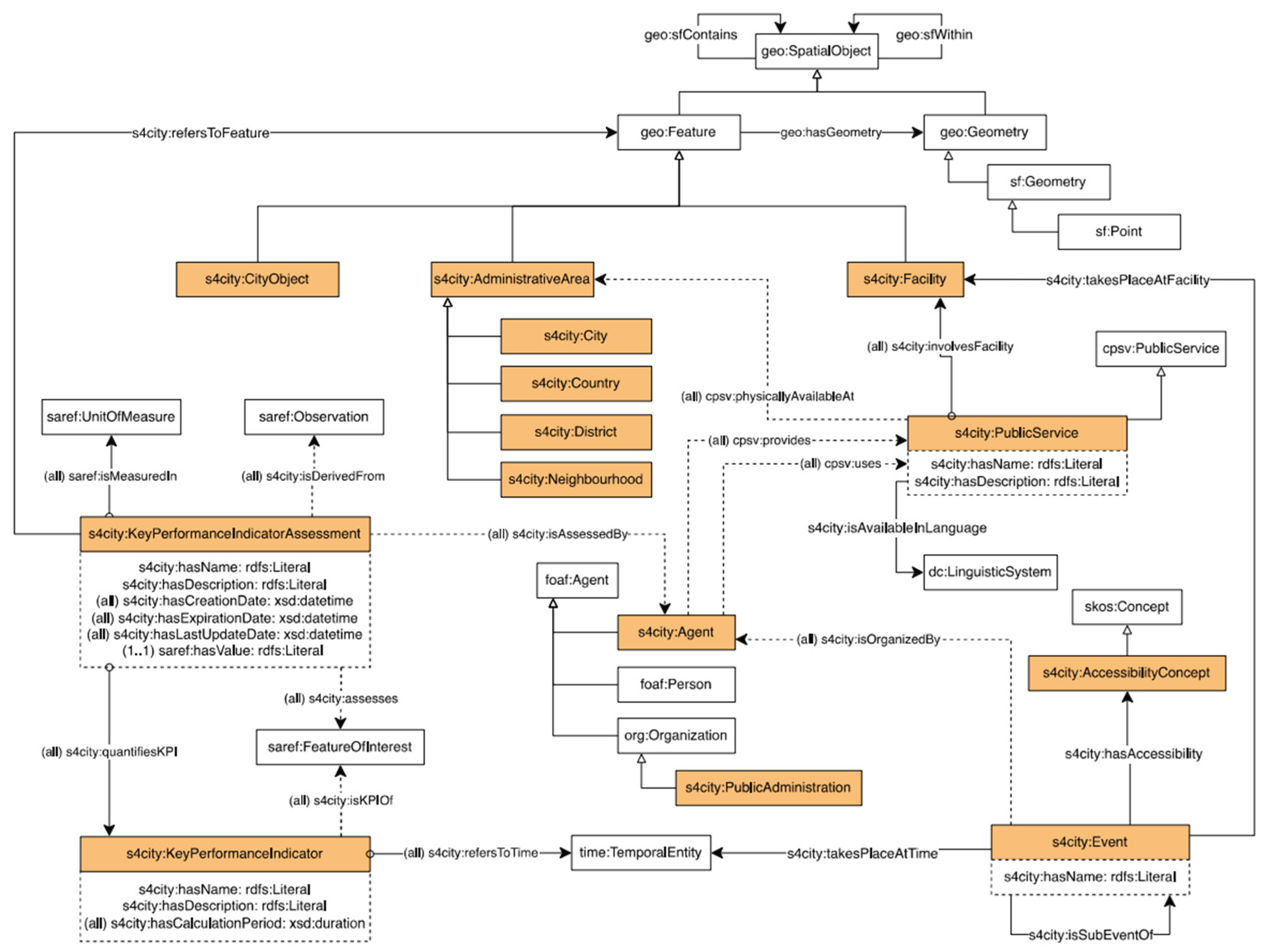

7.1.10. Smart City Ontologies

| Ontology | Description | Integrated Ontology |

|---|---|---|

| oneM2M ontology | Ontology for IoT and machine to machine interoperability. | SAREF |

| W3C SKOS ontology | Represents knowledge organisation systems. | SAREF |

| OGC and W3C SOSA/SSN ontology | Describes sensors and their observations. | SAREF, Km4City |

| OGC and W3C Time ontology | Describes temporal concepts. | SAREF |

| OGC GeoSPARQL vocabulary | Ontology for geographic information representation | SAREF, Km4City |

7.1.11. Next Generation Service Interface-Linked Data (NGSI-LD)

8. DIATOMIC Digital Twin Use Cases

|

|

9. System Architecture for a Federated Data Exchange Platform in Smart Cities

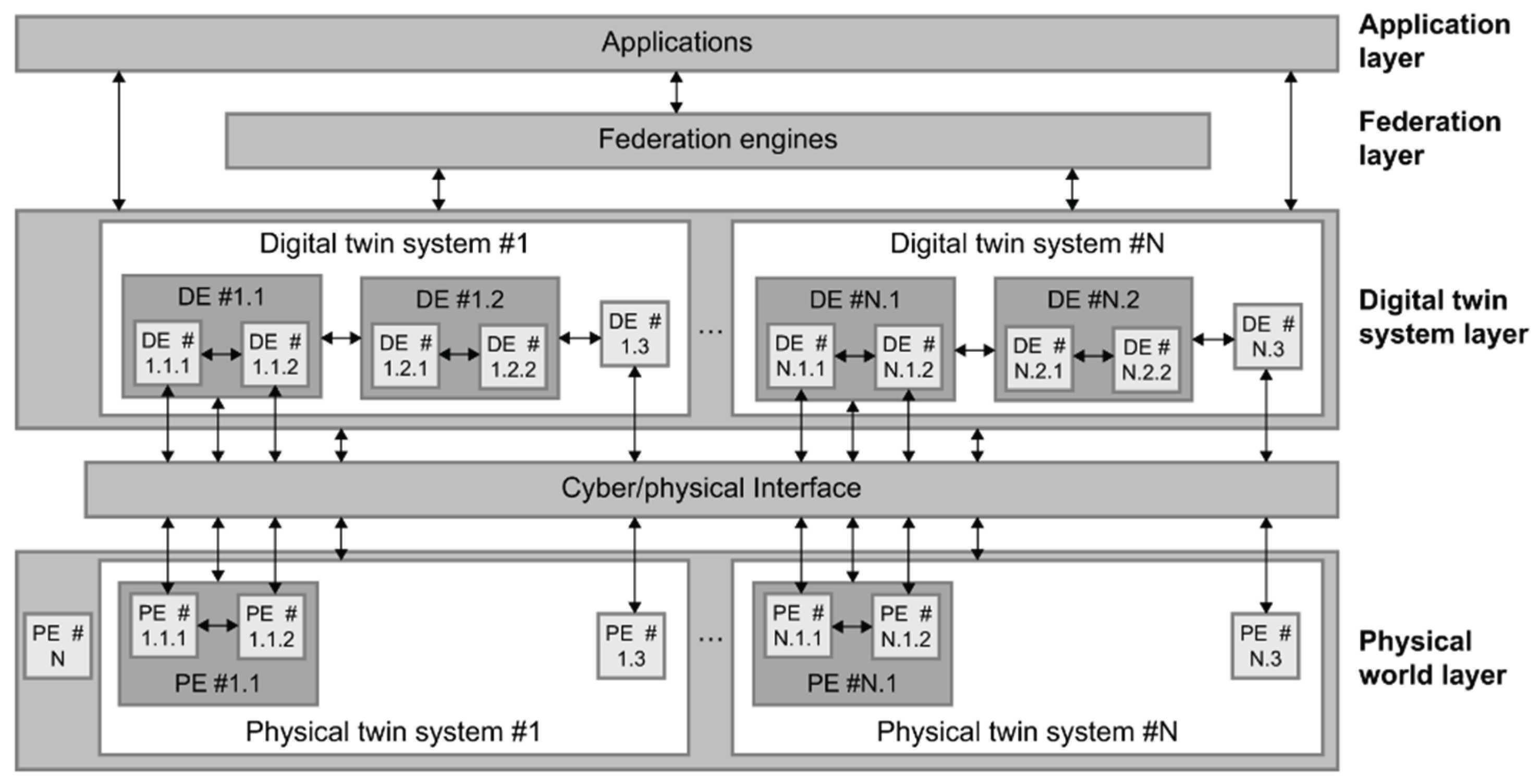

9.1. Layered Federated Digital Twin Architecture

- Data sources and physical system layer,

- Middleware and Integration Layer,

- Data Layer,

- Enablement Layer,

- DT Layer,

- Federation Layer, and

- Application Layer.

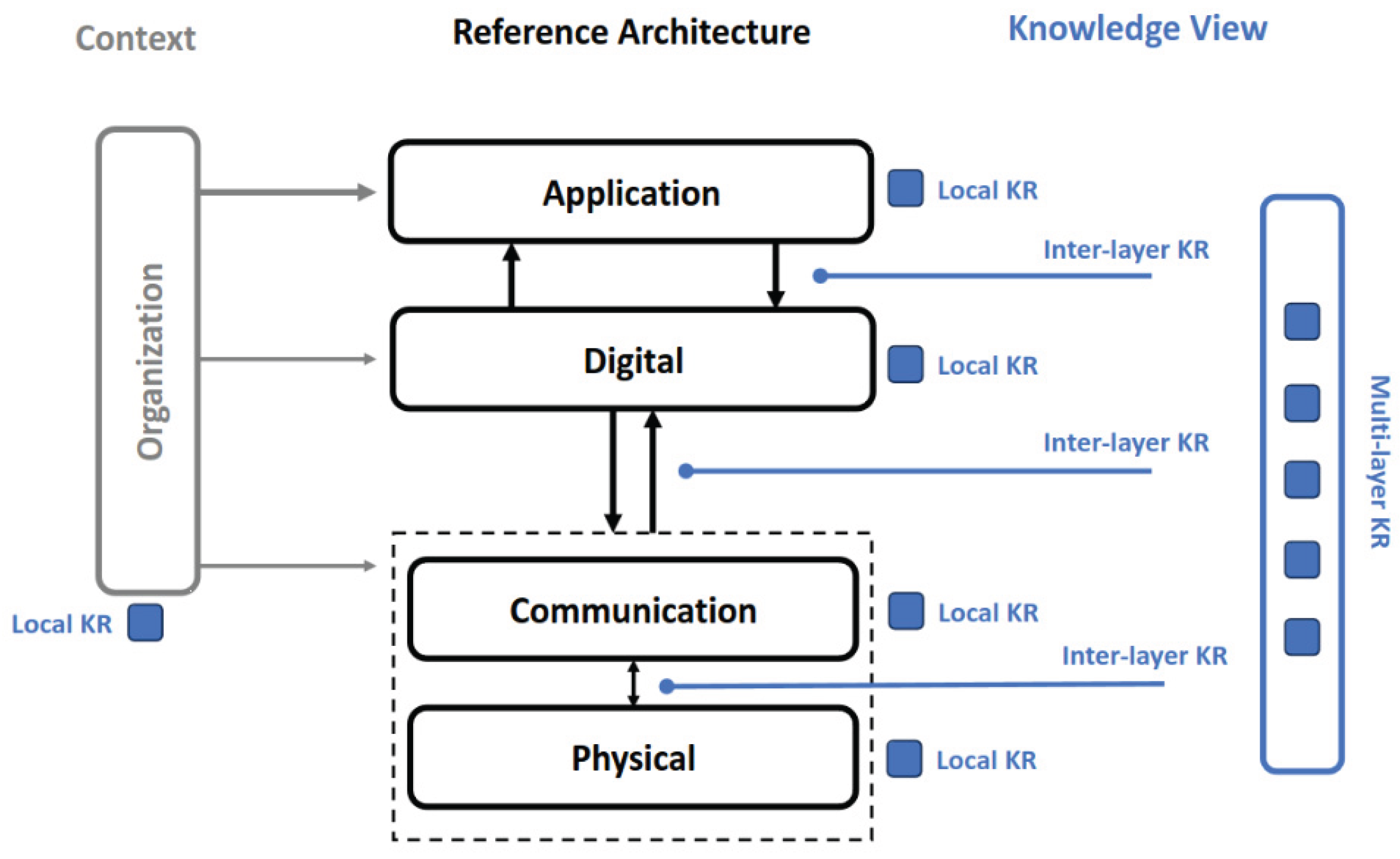

9.2. Composable Federated Digital Twin Architecture

9.3. Comparison of Architectures

9.4. Implementation of a Federated Digital Twin Platform

Architectural Considerations for Semantic Interoperability

10. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

| 1 | Consumer-centric protocols not listed. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 |

References

- Ferko, E.; Bucaioni, A.; Behnam, M. Architecting digital twins. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 50335–50350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M. PLM Initiatives [Powerpoint Slides]. Paper Presented at the Product Lifecycle Management Special Meeting, University of Michigan Lurie Engineering Center. Virtually Intelligent Product Systems: Digital and Physical Twins. 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334599683_Virtually_Intelligent_Product_Systems_Digital_and_Physical_Twins (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Baek, M.-S. Digital Twin Federation and Data Validation Method. In Proceedings of the 2022 27th Asia Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 19–21 October 2022; pp. 445–446. [Google Scholar]

- Parri, J.; Patara, F.; Sampietro, S.; Vicario, E. JARVIS, A Hardware/Software Framework for Resilient Industry 4.0 Systems. In Software Engineering for Resilient Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, P.; Sivabalan, A.S. A generic tri-model-based approach for product-level digital twin development in a smart manufacturing environment. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 64, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, G.N.; Steinmetz, C.; Rodrigues, R.N.; Henriques, R.V.B.; Rettberg, A.; Pereira, C. A Methodology for Digital Twin Modeling and Deployment for Industry 4.0. Proc. IEEE 2020, 109, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavotta, M.; Alge, M.; Menato, S.; Rovere, D.; Pedrazzoli, P. A Microservice-based Middleware for the Digital Factory. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Vera, D.A.; Ahmad, A. A Connective Framework to Support the Lifecycle of Cyber–Physical Production Systems. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C.; Bahsoon, R.; Theodoropoulos, G.; Yanez, W.; Tziritas, N. Federated Digital Twin. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 27th International Symposium on Distributed Simulation and Real Time Applications (DS-RT), Singapore, 4–5 October 2023; pp. 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmehzangi, A.; Ardakani, S.P. Embracing the Digital Twin Paradigm for Urban Sustainability. In Digital Twin Computing for Urban Intelligence; Ardakani, S.P., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, H.; Doost Mohammadian, M.R. Fusion of Digital Twin, Internet-of-Things and Artificial Intelligence for Urban Intelligence. In Digital Twin Computing for Urban Intelligence; Ardakani, S.P., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 2888.3-2024; IEEE Standard for Orchestration of Digital Synchronization Between Cyber and Physical Worlds. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes. Virtual Singapore: Building the World’s First 3D Digital Twin of a Nation. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/insights/customer-stories/virtual-singapore.

- Tech.gov.sg. 5 Things to Know About Virtual Singapore. Available online: https://www.tech.gov.sg/media/technews/5-things-to-know-about-virtual-singapore.

- National Research Foundation Singapore. Virtual Singapore. Available online: https://www.nrf.gov.sg/programmes/virtual-singapore.

- VentureBeat. How Singapore Created the First Country-Scale Digital Twin. 2020. Available online: https://venturebeat.com/business/how-singapore-created-the-first-country-scale-digital-twin/.

- Hämäläinen, M. Urban development with dynamic digital twins in Helsinki city. IET Smart Cities 2021, 3, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Helsinki. Smart Kalasatama—Smart City District of Helsinki. Available online: https://fiksukalasatama.fi/en/smart-city/.

- Forum Virium Helsinki. The Final Report on Smart Kalasatama. 2023. Available online: https://forumvirium.fi/en/publication/smartkalasatama-final-report/.

- Amsterdam Smart City. Home—Amsterdam Smart City. Available online: https://amsterdamsmartcity.com.

- Nelen & Schuurmans. Flood Early Warning in a 3D Digital Twin. Available online: https://nelen-schuurmans.nl/en/case/flood-early-warning-in-a-3d-digital-twin/.

- Bee Smart City. Amsterdam Smart City: A World Leader in Smart City Development. 2022. Available online: https://www.beesmart.city/en/smart-city-blog/smart-city-portrait-amsterdam.

- Via Smart Cities®. Smart City Amsterdam. 2021. Available online: https://www.viasmartcities.com/amsterdam-smart-city/.

- Adlershof Technology Park. Digital Twins in Adlershof: Optimising Urban Systems. Available online: https://www.adlershof.de/en/news/digital-twins.

- Siemens Sustainability Magazine. Siemensstadt Square: Building a Digital Twin for Sustainable Urban Development. 2022. Available online: https://sustainabilitymag.com/articles/siemens-a-glimpse-of-the-sustainable-city-of-the-future.

- TU Berlin. Digital Twin Applications in Transportation: Predicting Wheel Wear in Rolling Stock. Available online: https://www.tu.berlin/en/schienenfzg/research/research-projects/digital-twin.

- Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin. Digital Twin as a Key Component in Smart Environments: International Summer School Programme. Available online: https://www.htw-berlin.de/en/international/intercultural-exchange/international-summer-schools/digital-twin-as-a-key-component-in-smart-environments.

- Dubai Municipality. Dubai Here: Comprehensive Geospatial Information and Maps. 2020. Available online: https://www.dm.gov.ae/2020/06/28/dubai-municipality-launches-e-system-dubai-here-for-comprehensive-geospatial-information-and-maps/.

- Dubai Municipality. Geospatial Maps for Smarter Urban Planning. 2024. Available online: https://www.dm.gov.ae/dubai_more/geospatial-maps-for-smarter-urban-planning-and-building/.

- Asite. 5 Mega Projects in the Middle East Making the Most of Digital Twins. 2021. Available online: https://www.asite.com/blogs/5-mega-projects-in-the-middle-east-making-the-most-of-digital-twins.

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y. Digital Twin Networks: A Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 13789–13804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, X.; Xiao, S.; Hu, L. A review of the technology standards for enabling digital twin. Digital Twin 2022, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, G.; Singh, K.; Ramkumar, K.R. A detailed analysis of data consistency concepts in data exchange formats (JSON & XML). In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 5–6 May 2017; pp. 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navani, D.; Jain, S.; Nehra, M.S. The Internet of Things (IoT): A Study of Architectural Elements. In Proceedings of the 2017 13th International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems (SITIS), Jaipur, India, 4–7 December 2017; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, Z.; Khan, Z.; Ghafoor, A.; Soomro, K. SIGNED: Smart cIty diGital twiN vErifiable Data Framework. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 29430–29446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. A Review of Urban Digital Twins Integration, Challenges, and Future Directions in Smart City Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Agamy, R.F.; Sayed, H.A.; ALAkhatatneh, A.M.; Aljohani, M.; Elhosseini, M. Comprehensive analysis of digital twins in smart cities: A 4200-paper bibliometric study. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferko, E.; Bucaioni, A.; Pelliccione, P.; Behnam, M. Analysing Interoperability in Digital Twin Software Architectures for Manufacturing. In Software Architecture; Tekinerdogan, B., Trubiani, C., Tibermacine, C., Scandurra, P., Cuesta, C.E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tolk, A.; Wang, W. The Levels of Conceptual Interoperability Model: Applying Systems Engineering Principles to M&S. arXiv 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferko, E.; Bucaioni, A.; Pelliccione, P.; Behnam, M. Standardisation in Digital Twin Architectures in Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Software Architecture (ICSA), L’Aquila, Italy, 13–17 March 2023; pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliatsios, A.; Kotis, K.; Goumopoulos, C. A systematic review on semantic interoperability in the IoE-enabled smart cities. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uschold, M. Ontology and database schema: What’s the difference? Appl. Ontol. 2015, 10, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, E.; Pileggi, S.F.; Groth, P.; Degeler, V. Ontologies in digital twins: A systematic literature review. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 153, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 2888.1-2023; IEEE Standard for Specification of Sensor Interface for Cyber and Physical Worlds. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–143. [CrossRef]

- Gyrard, A.; Serrano, M.; Jares, J.B.; Datta, S.K.; Ali, M.I. Sensor-based Linked Open Rules (S-LOR): An Automated Rule Discovery Approach for IoT Applications and its use in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.; Daly, M.; Doyle, A.; Gillies, S.; Hagen, S.; Schaub, T. RFC 7946: The GeoJSON Format. USA: RFC Editor. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vinasco-Alvarez, D.; Samuel, J.; Servigne, S.; Gesquière, G. Towards an Automated Transformation of an nD Urban Data Model to a Computational Ontology Network: From UML to OWL, From CityGML 3.0 to “CityOWL”. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2024, X-4-W4-2024, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, M.; Usländer, T. Digital Twin and Internet of Things—Current Standards Landscape. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TS 103 410-4—V2.1.1—SmartM2M; Extension to SAREF; Part 4: Smart Cities Domain, n.d.

- GR CIM 020—V1.1.1—Context Information Management (CIM); NGSI-LD; Guidelines for the deployment of Smart City and Communities data platforms, n.d.

- Beyer, A.; Chernikova, K.; Panfilis, G.D.; Korneev, O.; Sapia, T.; Tejado, Á. FIWARE4CITIES, 6th ed.; FIWARE Foundation e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- MIM7—Places|OASC MIMs 2024. Available online: https://mims.oascities.org/mims/oasc-mim7-places (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- De Nicola, A.; Villani, M.L. Smart City Ontologies and Their Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

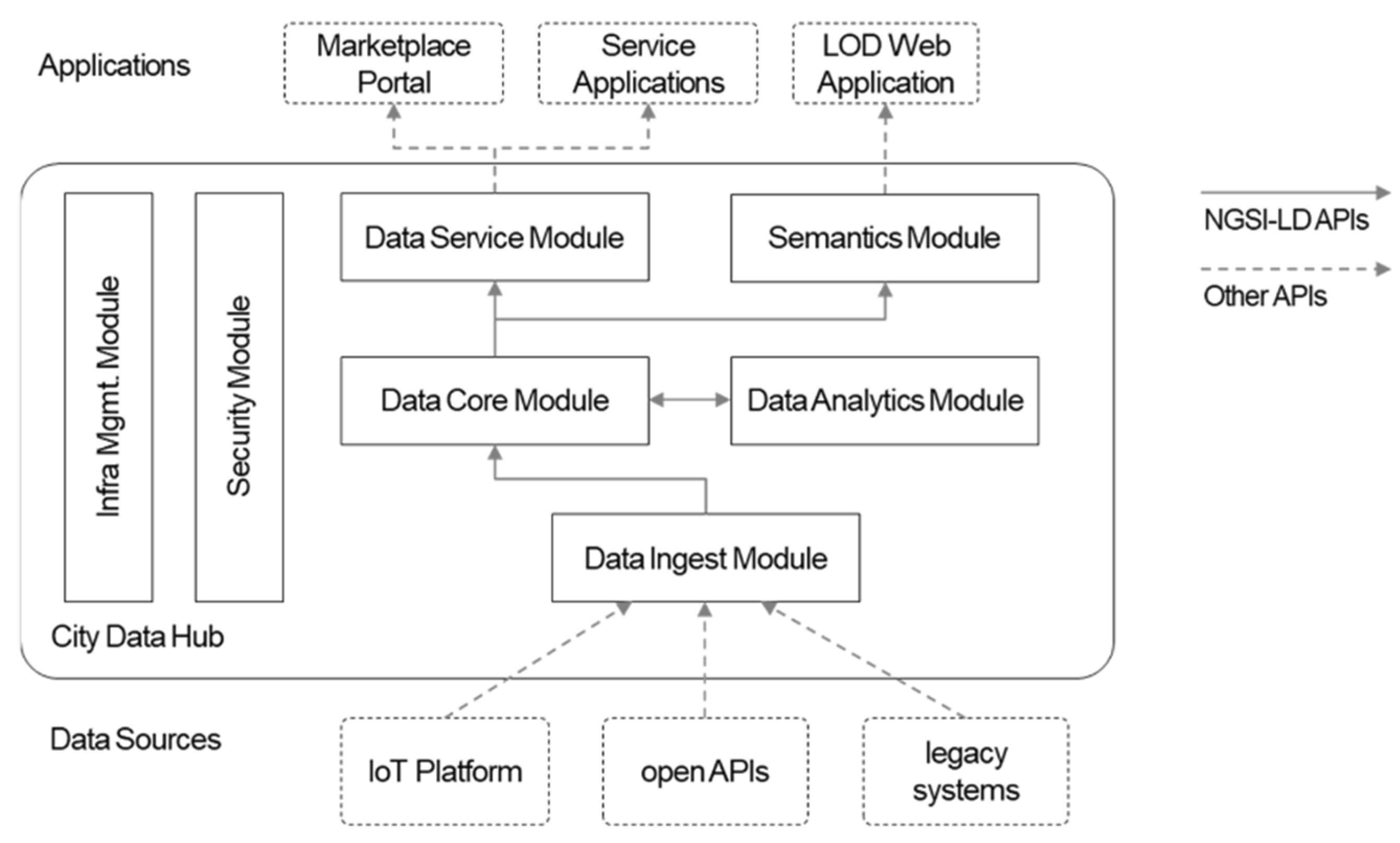

- Jeong, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, J. City Data Hub: Implementation of Standard-Based Smart City Data Platform for Interoperability. Sensors 2020, 20, 7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowlatabadi, J.Z.; Nasri, S.; Kavakli, M. NEXUS (Networked EXchange of Unified Systems) for Data Exchange in a Federated Smart City Digital Twin: A Case Study on Twin Cities. In Proceedings of the 23rd IEEE International Conference on Smart City, Exeter, UK, 13–15 August 2025; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kavakli-Thorne, M. Comparative Analysis of System Architectures for Federated Data Exchange. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Workshop on Intelligent Systems (IWIS), Ulsan, Republic of Korea, 21–24 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavakli, M.; Dowlatabadi, J.Z. System Architectures for Data Exchange in a Regional Federated Digital Twin: A Case Study on Birmingham Smart City. In Proceedings of the ICVARS 2025, 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Virtual & Augmented Reality Simulations (ICVARS), Birmingham, UK, 25–27 July 2025; pp. 43–49. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Dubai | Singapore | Helsinki | Amsterdam | Berlin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | IoT sensors, drones, GIS, BIM, satellite imagery | IoT devices, GIS, BIM, real-time sensors, 3DEXPERIENCE platform | IoT sensors, GIS, CityGML, GeoJSON | IoT sensors, LiDAR, GIS, environmental monitoring systems | IoT devices, BIM, CityGML, industrial datasets |

| Data Standards | CityGML, BIM, ISO/TC 211 standards | OGC standards, BIM, proprietary 3DEXPERIENCE formats | CityGML for semantic 3D modelling, GeoJSON for real-time data | CityGML, INSPIRE directive for environmental data, GeoJSON | CityGML, BIM, proprietary predictive models |

| Processing Framework | Cloud and edge computing; real-time IoT data integration | Hybrid cloud-edge architecture for real-time and historical data analysis | Distributed edge computing processes local IoT data with cloud-based aggregation | Edge computing for real-time processing; cloud systems for predictive simulations | Federated architecture; cloud systems for large-scale dataset processing |

| Integration Approach | Centralized data hub via Dubai Here platform; multi-agency collaboration | Federated model integrating data across agencies; geospatial and cross-domain interoperability | Open data portals and APIs for multi-stakeholder access | Real-time data fusion from sensors, APIs, and standardised formats | Secure federated systems with industrial and urban planning integration |

| AI and Analytics | Predictive maintenance, dynamic traffic flow optimization | AI-driven disaster modelling and urban energy demand forecasting | AI for demand-response energy management and urban layout optimisation | AI-powered traffic optimisation; advanced flood risk modelling | AI-enhanced predictive maintenance for transport and industrial systems |

| Citizen Engagement Tools | Participatory planning dashboards and AR/VR integration | Public platforms for viewing and commenting on urban developments | Open Cities Planner for visualisation and participatory design | Interactive geospatial platforms for city-wide projects | Innovation labs involving community-focused applications |

| Data Exchange Mechanisms | APIs for integration with private sector tools and external data providers | Dashboards for cross-agency data sharing; federated geospatial systems | APIs and open standards promote public-private collaboration | APIs and INSPIRE-compliant data formats for environmental and transport data exchange | APIs and secure channels for industrial-to-urban data exchange |

| Applications | Infrastructure monitoring, traffic optimization, Expo 2020 metaverse integration | Disaster preparedness, integrated urban planning, transport network optimization | Energy monitoring, urban heat island mitigation, real-time public feedback | Flood risk modelling, multimodal traffic control, urban sustainability | Predictive rail maintenance, transport logistics, Siemensstadt industrial optimisation |

| Key Achievements | Real-time traffic flow adjustments; Expo 2020 operational efficiency | Unified city-scale model for urban governance and disaster resilience | 10% energy savings in Kalasatama; congestion reduction through demand management | 15% congestion reduction; improved flood resilience | Reduced infrastructure downtime; energy-efficient urban industrial projects |

| Challenges | Scalability to city-wide systems; ensuring IoT data privacy and security | Balancing data privacy with public accessibility; expanding AI capabilities | High costs of real-time data collection; scaling digital twins city-wide | Handling diverse datasets from environmental, transport, and water systems | Harmonising industrial and urban datasets; enhancing predictive analytics |

| Future Directions | Integration with metaverse for immersive urban experiences; climate adaptation | Expanding autonomous vehicle testing; improving AI for decision-making | Scaling renewable energy integration; improving heat island mitigation | Advanced climate adaptation models; autonomous public transport | Extending Siemensstadt’s industrial digital twin to broader urban applications |

| XML | JSON |

|---|---|

| Relatively difficult for machines to parse. | Relatively easy for machines to parse. |

| Tags are used to define data which results in increased payload size. | Key value pairs are used to define data which amounts to lesser payload size and better indexing. |

| Moderate performance in data exchange in web service applications | High performance. |

| XML does not support data types and arrays. | JSON includes data types and arrays. |

| Not as light and fast as JSON | Faster and lighter than XML |

| XML being document oriented focusses on the structural component of data (lots of tags). | JSON being data oriented is the lightweight version of XML. |

| Level | Layer | Description | Example formats/Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perception/Physical | This is the foundation of IoT systems, consisting of sensors, actuators, and devices that collect data or execute commands. It is the interface of the physical and the digital. | JSON, XML, CSV, CBOR, various binary formats |

| 2 | Network/Transport | This layer connects the perception layer to the middleware layer. Usually, via the internet. | IPv6, UDP, TCP |

| 3 | Middleware/Processing | This layer processes the raw data from the perception layer, e.g., filtering or preprocessing. The aim is usually to reduce the volume of data. | |

| 4 | Applications | This layer defines the applications that uses the processed data. These applications may provide insights or control. Examples are smart homes, smart cities, smart health, etc. | HTTP, MQTT, Websocket, AMQP, CoAP, LwM2M, XMPP, DDS (Data Distribution service), SMS/SMPP, SSI (Simple Sensor Interface), OCPP (Open Charge Point Protocol), IEC 62056-21, OBD2/CAN, OPC-UA, Wireless M-bus1 |

| 5 | Business | This layer acts as a manager for IoT system and is focused on strategic decision-making. |

| Solution | Description |

|---|---|

| Keycloak | Identity and access management for RBAC. |

| Hyperledger Fabric | Blockchain framework for secure and traceable data sharing. |

| Apache Atlas | Data governance and metadata management. |

| IBM Guardium | Comprehensive data protection and encryption solution. |

| User Type | Responsibilities | Access Level | Restrictions |

|---|---|---|---|

| DT Owners | • Manage the development, data input, and maintenance of their DTs (e.g., traffic, air quality, energy). • Ensure data quality, security, and compliance with FDT governance policies. • Share relevant data with the FDT platform for aggregated insights and decision-making. • Define access permissions and data-sharing agreements for their DT. |

• Full access to their DT’s raw and processed data. • Permission to manage connections between their DT and the FDT. • Limited access to aggregated insights from other DTs. |

• Cannot access raw data from other DTs. • Must adhere to federation standards for data sharing and interoperability. |

| DT Developers | • Develop and maintain DT infrastructure, APIs, and data exchange mechanisms. • Implement predictive models and analytics tools to enhance DT functionalities. • Test and validate DT integrations within the FDT. |

• Access to testing environments and anonymised or simulated datasets. • No direct access to live or sensitive data unless explicitly authorised. |

• Limited to development environments. • No access to operational data without explicit authorisation. |

| FDT Council Administrators | • Define and enforce federation-wide data governance policies. • Oversee data-sharing agreements and ensure compliance with regulations (e.g., GDPR). • Manage access permissions and monitor system performance. |

• Full access to aggregated data and administrative tools. • Limited access to individual DTs’ raw data, permitted only during emergencies. |

• Cannot modify individual DTs without coordination. • Access limited to aggregated outputs. |

| Service Providers | • Utilise processed insights for operational improvements (e.g., route planning, energy grid adjustments). • Provide data to the FDT while ensuring quality and compliance with security standards. |

• Access to domain-specific processed insights. • No access to sensitive or raw data from other DTs. |

• Limited to operational insights. • Restricted from accessing raw data from other domains. |

| Academic Researchers | • Use anonymised datasets to conduct research and build models. • Collaborate with DT owners for access to specific datasets when needed. • Publish findings that align with smart city initiatives. |

• Read-only access to anonymised historical and processed datasets. • No access to real-time or sensitive data without explicit approval. |

• Restricted to non-sensitive data. • Access must comply with ethical and regulatory standards. |

| Public Users | • Use publicly available data to plan routes, monitor pollution, or make other personal decisions. • Provide feedback on public tools and services. |

• Read-only access to aggregated, pre-approved data (e.g., traffic maps, air quality indexes). • No access to backend systems or raw data. |

• Limited to aggregated, non-sensitive data. • No interaction with the FDT backend. |

| Cross-Domain Users | • Harmonise data from multiple DTs for simulations and city-wide optimisations. • Use aggregated insights to predict and manage cross-domain scenarios. |

• Access to aggregated, harmonised data from multiple DTs. • Restricted access to raw data, authorised only for specific use cases. |

• Limited to aggregated cross-domain insights. • Heavily restricted access to raw data. |

| Issue | Description | Potential Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Coverage | existing ontologies may not cover all relevant concepts and areas, and may not be able to accurately represent the complexity and diversity of urban systems | It may be required to use a combination of ontologies, or extend ontologies to cover required concepts. |

| Lack of Standardisation | different ontologies for smart cities may use different terminologies, concepts, and relationships, making it difficult to share and integrate data between different systems and stakeholders | To select standard ontologies, or when not possible, the most commonly used ontologies in the domain. |

| Lack of maintenance | existing ontologies (schema) may not be able to handle large amounts of data (instances), or adapt to new data sources and technologies, or incorporate new concepts and relationships as urban systems evolve | To select ontologies that are both suitable for large amounts of data and sufficiently flexible to future-proofed and are being maintained or are open to maintenance by us. Centralised governance at the city-level will ensure that ontologies are updated responsibly. |

| Lack of Scalability | existing ontologies may not be kept up-to-date with the most recent changes and developments in the city, leading to outdated information |

Centralised governance at the city-level will ensure that ontologies are updated responsibly. |

| Inadequate representation of context | existing ontologies may not be able to represent the context in various situations, such as social and cultural dimensions of a city in ontologies that focus solely on physical and technological aspects, or ignoring the interdependencies and relationships between different domains and systems in the city, such as transportation, energy, and environmental sustainability | Initially physical and technological aspects will be the focus of the Digital Twin program. However, this could be extended to socio-economic aspects in the future. The intention is to model the interactions between the domains and systems in the city, hence the desire for semantic interoperability. |

| Lack of privacy and security measures | existing ontologies may not have adequate measures to protect sensitive information and ensure that data is only shared with authorized parties | Use of data will be governed by stringent Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). |

| Data Formats | Description |

|---|---|

| Web Map Service (WMS) | Serves raster maps via web applications |

| Web Feature Service (WFS) | Enables access to vector geospatial data. (OGC recommends using the OGC API—Features, instead |

| Web Coverage Service (WCS) | Supports retrieval of large geospatial datasets |

| Sensor Things API | Standard for integrating IoT sensor data with digital twins |

| DT 1 | Aston University Fuel Cell Digital Twin | |

|---|---|---|

| This DT aims at improving the operational performance, efficiency, and durability of hydrogen fuel cells (HFC). The Fuel Cell DT addresses challenges in fuel cell maintenance, degradation, and real-time performance management, providing a comprehensive solution for condition-based monitoring and predictive maintenance. A predictive maintenance model estimates data for each component and degradation, repair and maintenance processes are simulated (Amaitik et al., 2024). | ||

| 3D Visualisation | 3D visualization supports real-time performance management and monitoring of the Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles as they move through the city. Visual tools and reporting features help users analyse performance trends over time, supporting decision-making for maintenance scheduling, fleet management, and resource allocation. | |

| Asset Management | The DT enhances asset management by improving the durability and operational efficiency of HFC. | |

| Predictive Analytics | Utilising predictive analytics, the system detects early signs of performance issues, enabling operators to carry out timely maintenance, reduce unexpected breakdowns, and lower overall maintenance costs. | |

| Artificial Intelligence | An integrated optimisation tool within the twin dynamically adjusts operational parameters based on real-time data, mitigating issues like overheating or water imbalances to enhance fuel cell performance and longevity. | |

| Machine Learning | Machine learning algorithms help the DT predict maintenance needs and monitor hydrogen fuel cell conditions in real-time. | |

| Authorisation Methods | Authorisation methods ensure secure access to DT systems monitoring HFC performance. | |

| Access Control | Access control mechanisms protect sensitive data and functionalities within HFC DT platform. | |

| API | APIs allow integration of the DT with other systems for monitoring and predictive maintenance of hydrogen fuel cells. The digital twin is hosted on an online platform that enables remote access, real-time monitoring, and data sharing across teams and stakeholders. | |

| Sensors | Sensors collect real-time data for the DT to monitor HFC conditions and support predictive maintenance. | |

| DT 2 | Birmingham University Digital Twin (Tyseley Park DT) | |

| The Birmingham University’s Tyseley Park DT has been designed to support Birmingham’s ambitions as a leading digital city. It aims to integrate real-time sensor data, data visualisation, and predictive analytics to enhance urban planning, energy and emissions management, traffic control, and other smart city applications. | ||

| 3D Visualisation | A 3D rendered model of the district was created to allow for the overlay of data, supporting data-driven urban planning and smart city development. Visualisation based on Cesium and the Unreal Engine. | |

| Asset Management | The DT enhances asset management by optimizing energy and urban infrastructure, systems and usage. | |

| Predictive Analytics | Predictive analytics in the DT enables proactive decision-making for traffic control, energy management, and city planning. | |

| Artificial Intelligence | Artificial Intelligence powers the DT to enhance smart city applications like energy optimization and traffic regulation. | |

| Machine Learning | Machine learning helps the DT analyse real-time sensor data for improved urban planning and predictive management. | |

| Authorisation Methods | Authorisation methods ensure secure access to the DT for managing smart city infrastructure. | |

| Access Control | Access control mechanisms safeguard critical data within the DT to protect smart city operations. | |

| API | APIs facilitate the integration of the DT with various urban management systems for data exchange. | |

| Sensors | Sensors provide real-time data to the DT, enabling enhanced monitoring and optimization of smart city functions. | |

| DT 3 | DT 3: Birmingham City University’s Traffic and Air Quality Digital Twin (TAQ-DT) | |

| This project combines AI, machine learning, and IoT to provide real-time insights, predictive analytics, and decision-making tools for city planners and operators. The TAQ-DT operates across different DT levels, from basic descriptive models to comprehensive, predictive systems. It aims to support Birmingham’s Clean Air Zone (CAZ) initiative by tracking and managing traffic and air quality in real-time. | ||

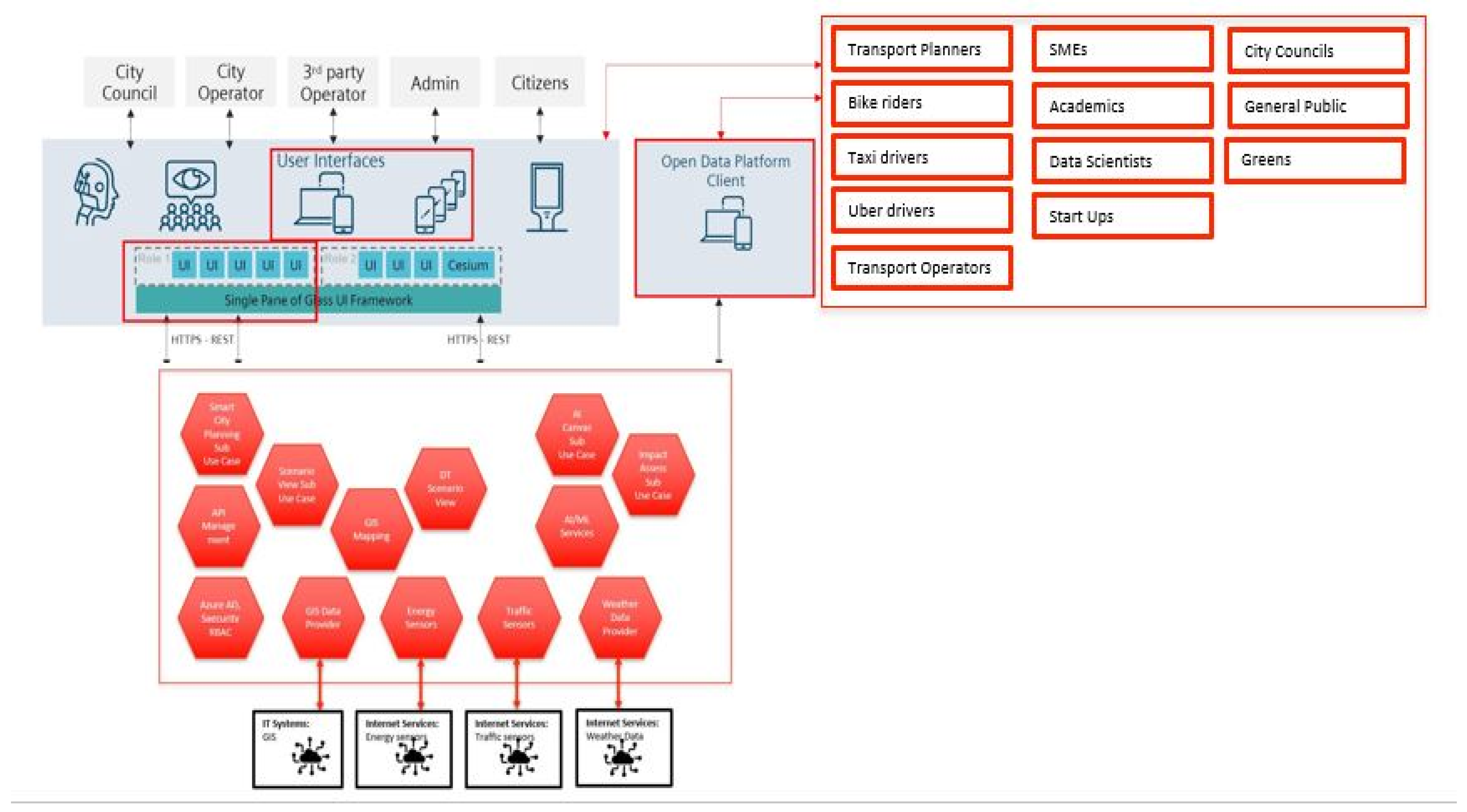

| 3D Visualisation | “Single Pane of Glass” UI framework helps city planners analyse traffic and air quality data for better decision-making. | |

| Asset Management | The TAQ-DT enhances asset management by optimizing urban resources to support Birmingham’s Clean Air Zone initiative. | |

| Predictive Analytics | Predictive analytics in the TAQ-DT enables real-time forecasting of traffic patterns and air quality levels. | |

| Artificial Intelligence | Employs AI to support real-time monitoring, decision-making, predictive analytics, and traffic flow optimisation. | |

| Machine Learning | Machine learning in the TAQ-DT refines predictive models to enhance traffic flow and air quality management. | |

| Authorisation Methods | Authorisation methods ensure secure access to real-time insights and predictive tools within the TAQ-DT. | |

| Access Control | Access control mechanisms protect sensitive traffic and environmental data processed by the TAQ-DT. | |

| API | APIs enable integration of the TAQ-DT with city planning and environmental monitoring systems. | |

| Sensors | Integrates data from multiple sources, including traffic and air quality sensors, GIS, and IoT devices | |

| DT 4 | Ulsan University’s Traffic Simulation Digital Twin | |

| Ulsan Traffic Simulation DT collects real human driving data using cameras and develops a learning-based driving model. By integrating learning-based model into a driving simulator, this project overcome the issue of the traditional rule-based models, which fail to imitate human-driving behaviour. | ||

| 3D Visualisation | 3D visualization in the Ulsan Traffic Simulation DT enhances traffic simulations by visually representing real-world driving behaviours. | |

| Asset Management | The DT can be used to optimize traffic management assets and fleet management for e.g., public transport vehicles. | |

| Predictive Analytics | Predictive analytics in the DT helps forecast driving behaviours and traffic patterns to enhance autonomous vehicle development. | |

| Artificial Intelligence | Artificial Intelligence enables the DT to model real-world driving behaviours, overcoming limitations of traditional rule-based driving simulations. | |

| Machine Learning | Machine learning in the DT allows for the development of learning-based driving models trained on real human driving datasets. | |

| Authorisation Methods | Authorisation methods ensure secure access to the DT’s simulation models and driving data. | |

| Access Control | Access control mechanisms protect sensitive datasets, including vehicle trajectories and sensor outputs, within the DT. | |

| API | APIs facilitate the integration of the DT with driving simulators, enabling real-time data exchange. | |

| Sensors | Camera, LiDAR, GPS, Accelerometers, steering, braking, etc. provide real-world driving data. | |

| DT 5 | Aston University’s Smart Campus Digital Twin | |

| This project aims to develop a Smart Campus at Aston University using drones to obtain data for visualisation. Aston University’s Smart Campus Digital Twin specifically targets campus-wide decarbonization, traffic monitoring and congestion management, maintenance, and disaster preparedness and emergency response. Drones were used to create high-resolution geospatial mappings and 3D modelling of buildings. | ||

| 3D Visualisation | The Smart Campus DT at Aston University utilizes drone-based high-resolution geospatial mapping and 3D modelling for campus visualization. | |

| Asset Management | The DT enhances asset management by using drones to monitor and maintain campus infrastructure, detecting issues before they become critical. | |

| Predictive Analytics | Predictive analytics in the DT helps forecast maintenance needs and potential infrastructure failures using real-time drone data. Dynamic simulations of disaster scenarios can be used to prepare and train first-responders. | |

| Artificial Intelligence | AI processes drone-collected data to improve infrastructure maintenance, disaster preparedness, and congestion management. | |

| Machine Learning | Machine learning models analyse drone sensor data to detect structural deformations, cracks, and temperature variations in campus infrastructure. | |

| Authorisation Methods | Authorisation methods ensure secure access to geospatial data and predictive analytics in the Smart Campus DT. | |

| Access Control | Access control mechanisms protect sensitive drone-captured data, such as real-time traffic monitoring and 3D building models. | |

| API | APIs enable integration of drone-generated data with the Smart Campus DT for real-time visualization and analysis. | |

| Sensors | Sensors, including cameras, LiDAR, and multi-spectral sensors, collect high-resolution data for accurate 3D campus modelling and analysis. | |

| Layer | Description |

|---|---|

| Data Sources and Physical Systems | This is composed of i) the wide range of sensors and IoT devices capable of collecting real-time data deployed in the smart city or acting in response to commands. ii) the data from Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) systems (such as industrial control systems). |

| Middleware and Integration | The middleware and integration layer facilitates data processing workflows, ensuring real-time updates and secure data transmission. Acting as an intermediary, this layer manages protocol translation, data synchronization, and secure data exchange between the platform layers (Lu et al., 2021; O’Connell et al., 2023). |

| Data | The Data Layer incorporates several key services to ensure that incoming data from IoT sensors, middleware processes, and DTs is properly, transformed, and stored for effective processing and decision-making. |

| Enablement | Acts as the driving force behind FDTs, extending their core functionalities by integrating advanced computational techniques, AI-driven intelligence, and decision-support capabilities. This layer is built upon the Data Layer, leveraging validated and transformed data to enhance optimization, analytics, predictive modelling, and intelligent automation within the FDT ecosystem. |

| DTs | The Birmingham City DTs. These DTs operate independently but collectively contribute to a federated system, enabling data sharing, insights generation, and informed decision-making. |

| Federation | This layer governs the management of the entire federated ecosystem, ensuring collaboration and effective decision-making among interconnected DTs. It facilitates the continuous updating of shared virtual models while preserving the confidentiality of data generated by individual DTs. |

| Application | The application layer consists of components that distribute processed data to external applications and stakeholders. Specifically, this layer utilizes the processed data and insights from DTs for monitoring, analysis, and decision-making across various smart city domains. This is served to the user through dashboards, reports, APIs, etc. |

| Data Governance and Security | In the proposed data exchange the data governance layer consists of microservices that handle authentication, authorization, and data encryption to ensure secure data sharing. These microservices these are but not limited to: Role-based access control (RBAC), Blockchain security microservice, and Encryption microservice. |

| Architecture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feature | Layered | Composable (microservices) |

| Modularity | There is separability of concerns by layers. The layers also have internal modules/services. | Very high. Uses independent reusable components. |

| Flexibility & Customisation | Limited by layers. Layers may use vendor-specific technologies, limiting scope to replace/modify them. Layers may be tightly-coupled with changes to one layer impacting others. | Should be higher as components are smaller and interacting through APIs. However, there are more opportunities for issues due to larger numbers of components and APIs. |

| Scalability & Distributed Load | Cloud-based microservices within layers can shift load. However, communication must go through layers, which can introduce overhead. | Cloud-based microservice components can easily distribute loads as required. |

| Security & Data Governance | As access is controlled through the layers, the attack surface is lower. Communication between layers is simpler to understand and therefore easier to secure. | Larger attack surface, due to the larger number of interacting components all with web interfaces. This may be mitigated through Zero-Trust Architecture (ZTA). The complexity of the possible interactions between components may make understanding the security context difficult. However, modularity may prevent security breach in one module affecting others (Kuruppuarachchi, Rea and McGibney, 2023). |

| Integration | The focus is generally on APIs between layers, reducing the complexity of system integration. | Due to the larger number of interacting components the complexity of the system is higher, with increased governance requirements to ensure adherence to APIs and standards. |

| No. | Layer | Siemens Solution | Application in the Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Physical System Layer | Siemens Industrial Edge | Connects to smart city infrastructure (e.g., sensors, traffic lights, power grids). |

| 2 | Communication Layer | MindConnect | Ensures secure IoT connectivity, supporting multiple protocols (MQTT, OPC-UA, 5G). |

| 3 | Digital Twins Layer | COMOS | Manages digital twin lifecycle and modeling for city infrastructure. |

| 4 | Middleware + Integration Layer | MindSphere, Simatic IT UA, Opcenter | Ensures standardized data formats, API integration, and security mechanisms. |

| 5 | Federation Layer | MindSphere AI, Mendix | Manages AI-driven decision-making and federated learning. |

| 6 | Application Layer | MindSphere Dashboards, Mendix | Provides real-time dashboards and analytics for smart city management. |

| No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | •Using a composable architecture will enable high flexibility, customisability and scalability. •To avoid vendor lock-in, there is a need to explore other FDT and DT solutions. |

||

| Data Exchange and Interoperability | •Use international standards for data exchange where available, to facilitate data exchange and promote interoperability. oJSON is specified as a sensor interface by IEEE 2888.3-2024. oStandardised APIs should be used for data exchange. •Non-repudiability of data once shared. This enables the data to be verified after it has been used. oBlockchain technology can enable this. •The aim of data Exchange in the FDT system is to enable semantic interoperability. It is therefore necessary to provide data with semantic information. •Following the OASC MIMs [52] recommendations for smart city interoperability where defined. •ETSI NGSI-LD for as information model capable of representing ontologies and recommended in MIM1. oMIM1 recommended alternatives for sensor data include OGC SensorThings API and LDES. •OGC’s CityGML is recommended as the most established data format and semantic model for 3D urban objects. •OGC’s CityGML and GeoJSON for geospatial encodings as these are standard formats and recommended in MIM7. •Data should be labelled with metadata, which follows a schema and uses a controlled vocabulary of standard terms. •Ontologies should be preferred for specifying data models, as these are more expressive than schemas and enable cross-domain interoperability and semantic reasoning. •Reusing open standard ontologies mitigate many of the limitations of using and maintaining ontologies and is preferable to developing a custom monolithic ontology (duplicating effort). •Aligning ontologies to minimize overlap for efficient data sharing and integration. •The SAREF and SAREF4City ontologies are recommended as they reuse standard open ontologies and are standardised by ETSI and part of the Rolling Plan for ICT standardisation in Europe: Data Interoperability (RP2025). It is also recommended for MIM2. MIM2 recommended alternatives: oNGSI-LD compliant city data models, e.g., from Smart Data Model initiative. oDTDL ontologies for smart cities and buildings are recommended by MIM2 as they are supported in Azure (and are also based on Smart Data Models). oISO/IEC 5087 City Data Model (in development) could be a suitable ontology. oCore vocabularies of former ISA2 (now Interoperable Europe) |

||

| Data Governance | •Data Sovereignty Compliance: Ensure all governance policies align with UK-specific regulations on data sovereignty and public sector data sharing. •Regular Review and Updates: Establish a governance review cycle to adapt to emerging technologies, regulations, and city needs. •Transparency with Citizens: Develop public-facing documentation to explain how data is collected, used, and protected, fostering trust in the system. •Implementation of stringent Role-based Access Control (RBAC) based around the 7 roles in Table 5. |

||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).