Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Literature

3. Theoretical Model: An Endogenous Framework for Sustainable Economic Growth

4. Empirical Methodology and Results

4.1. Unit Root Test Results

| Level/Difference | Break Years | Test Statistic (τ) | Stationary | |

| ly | Level | 1987, 1994 | -4.10*** | I(0) with break |

| lA | 1st difference | 2001,2009 | -5.96*** | I(1) with break |

| lH | Level | 1991, 1998 | -8.02*** | I(0) with break |

| lkd | 1st difference | 1980, 2015 | -9.82*** | I(1) with break |

| lfdistock | Level | 2005 | -7.07*** | I(0) with break |

4.2. ARDL Long- and Short-Run Estimates

4.3. Robustness Checks: FMOLS, DOLS and CCR

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARDL | Auto Regressive Distributed Lag |

| CCR | Canonical Cointegrating Regression |

| DOLS | Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares |

| EU | European Union |

| FDI | Foreign Direct Investment |

| FMOLS | Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares |

| GCF | Gross Capital Formation |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GVC | Global Value Chain |

| PIM | Perpetual Inventory Method |

| WDI | World Development Indicators |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Harrison, M.J. Can Corrupt Countries Attract Foreign Direct Investment? A Comparison Of FDI Inflows Between Corrupt And Non-Corrupt Countries. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 2011, 2. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.-J. QUALITY OF INSTITUTIONS AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: CAUSALITY TESTS FOR CROSS-COUNTRY PANELS. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2006, 7, 103–110. [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. J. Politi- Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The quarterly journal of economics, 107(2), 407-437.

- De Mello Jr, L. R. (1997). Foreign direct investment in developing countries and growth: A selective survey. The journal of development studies, 34(1), 1-34.

- Akinlo, A. Foreign direct investment and growth in NigeriaAn empirical investigation. J. Policy Model. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Iamsiraroj, S. The foreign direct investment–economic growth nexus. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2016, 42, 116–133. [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J. H. (1973). The determinants of international production. Oxford economic papers, 25(3), 289-336.

- Borensztein, E.; De Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.-W. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? J. Int. Econ. 1998, 45, 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Javorcik, B.S. Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 605–627. [CrossRef]

- Yimer, A. The effects of FDI on economic growth in Africa. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2022, 32, 2–36. [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H. Explaining the international direct investment position of countries: Towards a dynamic or developmental approach. Rev. World Econ. 1981, 117, 30–64. [CrossRef]

- Görg, H., & Greenaway, D. (2001). Foreign direct investment and intra-industry spillovers: a review of the literature.

- Amighini, A.; McMillan, M.; Sanfilippo, M. (2017). FDI and capital formation in developing economies: new evidence from industry-level data (No. w23049). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Simionescu, M., & Naroş, M. S. (2019). The role of foreign direct investment in human capital formation for a competitive labour market. Management Research and Practice, 11(1), 5-14.

- Ramirez, M.D. Is foreign direct investment beneficial for Mexico? An empirical analysis, 1960–2001. World Dev. 2006, 34, 802–817. [CrossRef]

- Arısoy, İ. The Impact Of Foreign Direct Investment On Total Factor Productivity And Economic Growth In Turkey. J. Dev. Areas 2012, 46, 17–29. [CrossRef]

- Iamsiraroj, S.; Ulubaşoğlu, M.A. Foreign direct investment and economic growth: A real relationship or wishful thinking?. Econ. Model. 2015, 51, 200–213. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.L.; Cipollina, M. A meta-analysis of the indirect impact of foreign direct investment in old and new EU member states: Understanding productivity spillovers. World Econ. 2017, 41, 1342–1377. [CrossRef]

- Pintilie, N., Cicea, C., & Marinescu, C. (2020, November). A bibliometric study of environmental protection and economic development: revealing links and dynamics. In Proceedings of the 14th International Management Conference: Managing Sustainable Organizations, 5th-6th November, Bucharest, Romania (pp. 335-345).

- De Gregorio, J. (1992). Economic growth in latin america. Journal of development economics, 39(1), 59-84.

- Blomström, M.; Kokko, A.; Zejan, M. Host country competition, labor skills, and technology transfer by multinationals. Rev. World Econ. 1994, 130, 521–533. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanyam, V.N.; Salisu, M.; Sapsford, D. Foreign Direct Investment and Growth in EP and is Countries. Econ. J. 1996, 106, 92. [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Chakraborty, C.; Reagle, D. Liberalization, FDI, and Growth in Developing Countries: A Panel Cointegration Approach. Econ. Inq. 2003, 41, 510–516. [CrossRef]

- Baharumshah, A.Z.; Almasaied, S.W. Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth in Malaysia: Interactions with Human Capital and Financial Deepening. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2009, 45, 90–102. [CrossRef]

- Jude, C. Does FDI crowd out domestic investment in transition countries?. Econ. Transit. Institutional Chang. 2018, 27, 163–200. [CrossRef]

- Bénétrix, A.; Pallan, H.; Panizza, U. The Elusive Link between FDI and Economic Growth; World Bank: Washington, DC, United States, 2023; ISBN: .

- Baldwin, R. E. (2006). Globalisation: the great unbundling (s).

- Hermes, N.; Lensink, R. Foreign direct investment, financial development and economic growth. J. Dev. Stud. 2003, 40, 142–163. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L.; Chanda, A.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Sayek, S. FDI and economic growth: the role of local financial markets. J. Int. Econ. 2004, 64, 89–112. [CrossRef]

- Azman-Saini, W.; Law, S.H.; Ahmad, A.H. FDI and economic growth: New evidence on the role of financial markets. Econ. Lett. 2010, 107, 211–213. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L.; Chanda, A.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Sayek, S. Does foreign direct investment promote growth? Exploring the role of financial markets on linkages. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 91, 242–256. [CrossRef]

- Osei, M.J.; Kim, J. Foreign direct investment and economic growth: Is more financial development better?. Econ. Model. 2020, 93, 154–161. [CrossRef]

- Durham, J. Absorptive capacity and the effects of foreign direct investment and equity foreign portfolio investment on economic growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2004, 48, 285–306. [CrossRef]

- Jude, C.; Levieuge, G. Growth Effect of Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Economies: The Role of Institutional Quality. World Econ. 2016, 40, 715–742. [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, L., Kubatko, O., & Pysarenko, S. (2014). The impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth: case of post communism transition economies. Problems and perspectives in Management, (12, Iss. 1), 17-24.

- Ciftci, C.; Durusu-Ciftci, D. Economic freedom, foreign direct investment, and economic growth: The role of sub-components of freedom. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2021, 31, 233–254. [CrossRef]

- Carkovic, M., & Levine, R. (2005). Does foreign direct investment accelerate economic growth. Does foreign direct investment promote development, 195, 220.

- Mišun, J.; Tomšík, V. Foreign direct investment in central europe - does it crowd in domestic investment?. Prague Econ. Pap. 2002, 11, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Herzer, D.; Klasen, S.; D., F.N.-L. In search of FDI-led growth in developing countries: The way forward. Econ. Model. 2008, 25, 793–810. [CrossRef]

- Markusen, J.R.; Venables, A.J. Multinational firms and the new trade theory. J. Int. Econ. 1998, 46, 183–203. [CrossRef]

- Easterly, W. How much do distortions affect growth?. J. Monetary Econ. 1993, 32, 187–212. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, I.; Tokunaga, M. Macroeconomic Impacts of FDI in Transition Economies: A Meta-Analysis. World Dev. 2014, 61, 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M. Foreign Direct Investment in Mexico: A Cointegration Analysis. J. Dev. Stud. 2000, 37, 138–162. [CrossRef]

- Fry, M. J. (1999, January). Financing economic reform: mobilising domestic resources and attracting the right kind of external resources. In Growth and Competition in the New Global Economy (p. 59). OECD Publishing.

- Findlay, R. Relative Backwardness, Direct Foreign Investment, and the Transfer of Technology: A Simple Dynamic Model. Q. J. Econ. 1978, 92. [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.B.; Noy, I. Sectoral analysis of foreign direct investment and growth in the developed countries. J. Int. Financial Mark. Institutions Money 2009, 19, 402–413. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Nagarajan, S.; Aggarwal, P.; Gupta, V.; Tomar, R.; Garg; Sahoo; Sarkar, A.; Chopra, U.; Sarma, K.S.; et al. Effect of mulching on soil and plant water status, and the growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in a semi-arid environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2008, 95, 1323–1334. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Manufacturing FDI and economic growth: evidence from Asian economies. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 991–1002. [CrossRef]

- Aykut, D., & Sayek, S. (2007). The role of the sectoral composition of foreign direct investment on growth. Do multinationals feed local development and growth, 22, 35-62.

- Haini, H.; Tan, P. Re-examining the impact of sectoral- and industrial-level FDI on growth: Does institutional quality, education levels and trade openness matter?. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2022, 61, 410–435. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Luo, R.; Ali, K.; Irfan, M. How does the sectoral composition of FDI induce economic growth in developing countries? The key role of business regulations. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2022, 36. [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A.; Khalid, A.M.; Tariq, F. Does technology shape the relationship between FDI and growth? A panel data analysis. Appl. Econ. 2023, 56, 2544–2567. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.H.; Song, S. Promoting exports: the role of inward FDI in China. China Econ. Rev. 2001, 11, 385–396. [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, S.S.; Ajmi, A.N. Causality relationship between energy consumption, economic growth, FDI, and globalization in SSA countries: a symbolic transfer entropy analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44623–44628. [CrossRef]

- Kokko, A. O. (1994). Foreign direct investment, host country characteristics, and spillovers.

- Ciobanu, M. (2015). Foreign direct investments and processing industry competitiveness in the Republic of Moldova. Meridian Ingineresc, (4), 50-57.

- Ayanwale, A. B. (2007). FDI and economic growth: Evidence from Nigeria.

- Kechagia, P.; Metaxas, T. Sixty Years of FDI Empirical Research: Review, Comparison and Critique. J. Dev. Areas 2018, 52, 169–181. [CrossRef]

- Kostoulis, D. FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT AND GROWTH: A LITERATURE REVIEW FROM 1990 TO DATE. Eur. J. Econ. Financial Res. 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, M.; Sanchez-Robles, B. Foreign direct investment, economic freedom and growth: new evidence from Latin America. Eur. J. Politi- Econ. 2003, 19, 529–545. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Chaudhry, N., Mehmood, A., & Saqib Mehmood, M. (2013). Empirical relationship between foreign direct investment and economic growth: An ARDL co-integration approach for China. China Finance Review International, 3(1), 26-41.

- Chowdhury, R. A., Abdullah, M. N., & Tooheen, R. B. (2017). FDI-based business: the case of Bangladesh. World, 7(2), 1-8.

- Bergougui, B.; Murshed, S.M. Spillover effects of FDI inflows on output growth: An analysis of aggregate and disaggregated FDI inflows of 13 MENA economies. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2023, 62, 668–692. [CrossRef]

- Bildirici, M., Aykaç-Alp, E., & Kayıkçı, F. (2010, November). Effects of Foreign Direct Investment on Growth in Türkiye. In International Conference on Eurasian Economies, Istanbul, November (pp. 4-5).

- Ilgun, E., Karl-Josef, K. O. C. H., & Orhan, M. (2010). How Do Foreign Direct Investment And Growth Interact In Türkiye?. Eurasian Journal Of Business And Economics, 3(6), 41-55.

- Ekinci, A. (2011). Doğrudan yabancı yatırımların ekonomik büyüme ve istihdama etkisi: Türkiye uygulaması (1980-2010). Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi İİBF Dergisi, 6(2), 71-96.

- Aga, A. A. K. (2014). The impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth: A case study of Türkiye 1980–2012. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 6(7), 71-84.

- Cambazoglu, B., & Simay Karaalp, H. (2014). Does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? The case of Türkiye. International Journal of Social Economics, 41(6), 434-449.

- Demirsel, M. T., Adem, Ö., & Mucuk, M. (2014, October). The effect of foreign direct investment on economic growth: the case of Türkiye. In Proceedings of International Academic Conferences (No. 0702081). International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

- Gokmen, O. (2021). The relationship between foreign direct investment and economic growth: A case of Türkiye. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.08144.

- Kurul, Z. (2021). Türkiye’de doğrudan yabancı yatırım girişleri ve yurtiçi yatırım ilişkisi: Doğrusal olmayan ARDL yaklaşımı. Sosyoekonomi, 29(49), 271-292.

- Saglam, B. B., & Yalta, A. Y. (2011). Dynamic linkages among foreign direct investment, public investment and private investment: Evidence from Türkiye. Applied Econometrics and International Development, 11(2), 71-82.

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The quarterly journal of economics, 70(1), 65-94.

- Lucas Jr, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of monetary economics, 22(1), 3-42.

- Barro, R. J. (2001). Human capital and growth. American economic review, 91(2), 12-17.

- Neuhaus, M. (2006). The impact of FDI on economic growth: an analysis for the transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD.

- Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Convergence. Journal of political Economy, 100(2), 223-251.

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. Handbook of economic growth, 1, 385-472.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University.

- Hall, R.E.; Jones, C.I. Why do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker than Others?. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 83–116. [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Lee, J.W. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 104, 184–198. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. & Shin, Y. (1999) An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis ,In: S. Strom (ed.), Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium, 1999, Ch. 11. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Narayan, P.K. The saving and investment nexus for China: evidence from cointegration tests. Appl. Econ. 2005, 37, 1979–1990. [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B. (2004). Modelling the long run determinants of private investment in Senegal (No. 04/05). Credit Research Paper.

- MacKinnon, J. G. (1996). Numerical distribution functions for unit root and cointegration tests. Journal of applied econometrics, 11(6), 601-618.

- Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P. C., Schmidt, P., & Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? Journal of econometrics, 54(1-3), 159-178.

- Lee, J.; Strazicich, M.C. Minimum Lagrange Multiplier Unit Root Test with Two Structural Breaks. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2003, 85, 1082–1089. [CrossRef]

- Easterly, W.; Kremer, M.; Pritchett, L.; Summers, L.H. Good policy or good luck?. J. Monetary Econ. 1993, 32, 459–483. [CrossRef]

- Singer, H. W. (1950). The Distribution of Gains between Investing and Borrowing Countries. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings.

- Acemoglu, D.; Naidu, S.; Restrepo, P.; Robinson, J.A. Democracy Does Cause Growth. J. Politi- Econ. 2019, 127, 47–100. [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D.; Subramanian, A.; Trebbi, F. Institutions Rule: The Primacy of Institutions Over Geography and Integration in Economic Development. J. Econ. Growth 2004, 9, 131–165. [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.; Woessmann, L. (2009). Schooling, cognitive skills, and the Latin American growth puzzle (No. w15066). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Docquier, F.; Rapoport, H. Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development. J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 681–730. [CrossRef]

- Bakış, O., & Acar, U. (2021). Türkiye ekonomisinde toplam faktör verimliliği: 1980-2019. Journal of Research in Economics, 5(1), 1-27.

| Data Coverage | Sample | Dependent variable | FDI Stocks/ Flows | Methodology | Main Findings (+/-) | |

| Balabsubrmanyam et. al. (1994) [23] | 1970-85 | 46 countries | Real DGP growth | Flow | Cross-section regression (OLS) | + |

| Borenzstein et al. (1996) [9] | 1970-89 | 69 developing countries | Real GDP Growth | Flow | Cross-country regression | + |

| De Mello (1999) [5] | 1970-90 | 32 OECD and non OECD countries | Per capita real GDP, TFP | Flow | Panel and country specific cointegration | + |

| Zhang and Song (2001) [54] | 1984-98 | China provinces | Real GDP growth | Flow | Cross- section Panel data (OLS) | + |

| Basu et. al. (2003) [24] | 1978-96 | 23 developing countries | Real GDP | Flow | Panel Cointegration | + |

| Bengoa and Sanchez-Robbles (2003) [62] | 1970-1999 | 18 developing countries | Real GDP per capita growth | Flow | Panel cointegration | + depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Hermes and Lensink (2003) [29] | 1975-1995 | 67 Developing countries | Real GDP growth per capita | Flow | Panel data (OLS) | + depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Akinlo(2004) [6] | 1970-2001 | Nigeria | Real GDP | Stock | Country specific, ECM | - (only + with a considerable lag) |

| Alfaro et. al. (2004) [30] | 1975-1995 | 71 countries | Real GDP per capita | Flow | Cross sectional analysis | + depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Carkovic and Levine (2005) [38] | 1960-1995 | 79 developed and developing countries | Real per capita GDP growth | Flow | Panel data (GMM) | - |

| Aykut and Sayek (2008) [50] | 1990-2003 | 39 countries | Real GDP per capita growth | Flow | Cross sectional analysis | + (manufacturing sector) |

| Herzer et. al. (2008) [40] | 1970-2003 | 28 developing countries | Real GDP | Flow | Country specific cointegration | Some + some – depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Azman-Saini et. al. (2010) [31] | 1976-2004 | 85 countries | Real GDP per capita | Flow | Panel data (GMM) | + depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Iqbal Chaudhry et al. (2013) [62] | 1985-2009 | China | GDP (USD) | Flow | Cointegration- ARDL | + |

| Iamsiraroj& Ulubaşoğlu (2015) [18] | 1970-2009 | 140 developed and developing countries | Real GDP per capita | Flow | Dynamic panel data | + |

| Chaudry et al. (2017) [63] | 1990-2014 | 25 developing countries | Real GDP | Flow | Panel data cointegration (FMOLS) | + |

| Ciobanu (2020) [57] | 1991-2018 | Romania | Real GDP | Flow | ARDL | + |

| Benetrix et. al. (2023) [27] | 1970-2017 (different samples) | 96 countries | Real GDP growth | Flow | Cross-country and panel regression | + depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Bergougui and Murshed (2023) [64] | 2000-2020 | 13 MENA countries | Real GDP per capita/ sectoral real GDP per capita | Flow | Dynamic panel GMM | + (manufacturing sector) |

| Osei and Kim (2023) [33] | 1990-2009 | 75 countries | Real GDP | Flow | Threshold non-linear dynamic panel | + depending on the absorptive characteristics |

| Yimer (2023) [11] | 1990-2016 | 46 African countries classified as fragile, investment driven and factor driven | Real GDP | Stock | Panel data cointegration (CCE estimator) | + in investment driven in, + in factor driven only in the long run, - in fragile states |

| Morasco et.al. (2024) [53] | 1989-2019 | 48countries | Real GDP per capita growth | Flow | Dynamic Panel (GMM) | + (in high-tech and low tech, - in medium tech sectors) |

| Empirical Literature related to Türkiye | ||||||

| Bildirici et. al. (2010) [65] | 1992-2008 | Türkiye | Industrial Production | Flow | Treshold cointegration | + |

| İlgün et. al. (2010) [66] | 1980-2004 | Türkiye | Real GDP growth | Flow | VAR and causality tests | + |

| Ekinci (2011) [67] | 1980-2010 | Türkiye | Real GDP | Flow | Cointegration analysis | + |

| Arısoy (2012) [17] | 1960-2005 | Türkiye | Real GDP growth | Flow | Cointegration analysis | + |

| Aga (2014) [68] | 1980-2012 | Türkiye | GDP per capita (USD) | Flow | Cointegration analysis | + |

| Cambazoğlu and Karaalp (2014) [69] | 1980-2010 | Türkiye | Real GDP growth | Flow | VAR analysis | + |

| Demirsel et. al. (2014) [70] | 2002-2014 | Türkiye | Real GDP | Flow | Cointegration analysis | No significant relationship |

| Gökmen (2021) [71] | 1970-2019 | Türkiye | Real GDP | Flow | Cointegration analysis | No significant relationship |

| Kurul (2021) [72] | 1984-2018 | Türkiye | Real GDP growth | Flow | Non-linear ARDL | + |

| ADF Test Results | PP Test Results | KPSS Test Results | |||||

| Level | 1st difference | Level | 1st difference | Level | 1st difference | Result | |

| ly | 0.03 | -8.84*** | -0.06 | -8.94*** | 1.46 | 0.05 | I(1) |

| lA | -1.34 | -6.55*** | -1.76 | -4.43*** | 0.28 | 0.08 | I(1) |

| lH | -0.96 | -3.76*** | -0.31 | -2.98** | 1.45 | 0.10 | I(1) |

| lkd | 1.11 | -6.53*** | -2.70* | -15.09*** | 1.23 | 0.25 | I(1) |

| lfdistock | -2.02 | -8.54*** | -4.22 | -16.44*** | 1.28 | 0.03 | I(1) |

| Bounds Critical Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (no cointegration) | |||

| k=4 | I(0) | I(1) | |

| Calculated F Statistics: 10.33*** | 10% | 3.21 | 4.29 |

| 5% | 3.79 | 4.99 | |

| 1% | 5.11 | 6.49 | |

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t-statistic | Probability | ||

| Dependent Variable: ly (GDP per worker) | |||||

| Panel A: Long-Run Coefficients | |||||

| lA | 0.13** | 0.07 | 1.99 | 0.05 | |

| lH | -2.19*** | 0.41 | -5.39 | 0.00 | |

| lkd | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.28 | 0.78 | |

| lfdistock | -0.05*** | 0.01 | -3.79 | 0.00 | |

| Panel B: Short-Run Coefficients | |||||

| ∆ lA | 0.24*** | 0.08 | 2.88 | 0.00 | |

| ∆ lH | -9.59*** | 2.77 | -3.46 | 0.00 | |

| ∆ lH (-1) | 6.84** | 2.77 | 2.47 | 0.02 | |

| ∆ lfdistock | -0.02*** | 0.01 | -3.91 | 0.00 | |

| ∆ lfdistock (-1) | 0.01** | 0.01 | 2.09 | 0.04 | |

| DUM1994 | -0.11*** | 0.02 | -5.31 | 0.00 | |

| DUM2001 | -0.07** | 0.03 | -2.56 | 0.01 | |

| DUM2009 | -0.05* | 0.03 | -1.92 | 0.06 | |

| C | 8.68*** | 1.14 | 7.58 | 0.00 | |

| TREND | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 7.70 | 0.00 | |

| ECM | -0.75*** | 0.01 | -7.56 | 0.00 | |

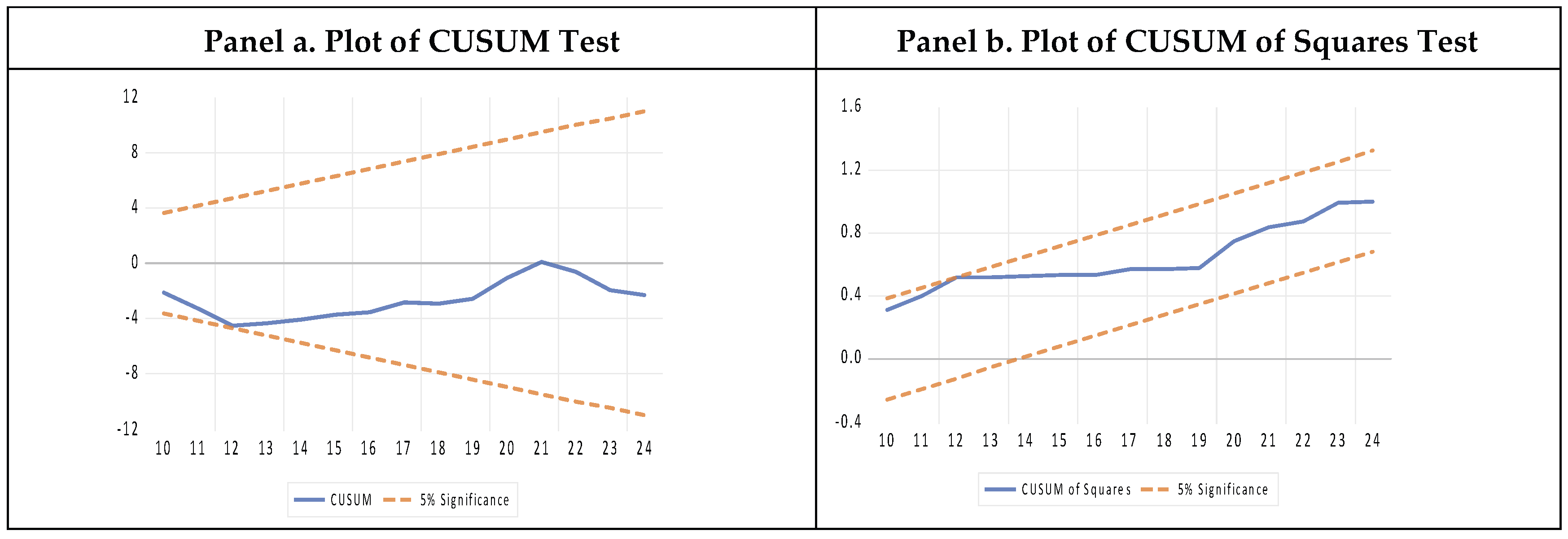

| Panel C: Diagnostic Test Results | |||||

| Test Results | Probability | ||||

| Serial Correlation (Breusch-Godfrey) | F = 0.08 | 0.89 | |||

| Heteroskedasticity (Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey) | F = 20.02 | 0.13 | |||

| Model Specification (Ramsey RESET) | F = 0.19 | 0.67 | |||

| Normality of Residuals (Jarque-Bera) | JB = 1.60 | 0.44 | |||

| ARDL | FMOLS | DOLS | CCR | |

|

Dependent Variable: ly (GDP per worker) | ||||

| lA | 0.13** (0.05) |

0.16*** (0.00) |

0.24* (0.09) |

0.12*** (0.00) |

| lH | -2.19*** (0.00) |

-1.60*** (0.00) |

-3.22*** (0.00) |

-1.46*** (0.00) |

| lkd | -0.01 (0.77) |

-0.01** (0.04) |

0.01 (0.85) |

-0.02*** (0.00) |

| lfdistock | -0.05*** (0.00) |

-0.01** (0.03) |

-0.14*** (0.00) |

-0.01** (0.03) |

| 1 | Foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to an investment in which an investor from one country acquires at least 10 per cent of the voting rights in an enterprise located in another country, with the intention of establishing a lasting interest and exerting significant influence over its management. FDI also serves as the backbone of multinational enterprises (MNEs), enabling them to establish and maintain control over operations across multiple countries. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Dutch disease refers to the negative economic consequences that may arise when large inflows of foreign currency (e.g., from natural resources or capital inflows) lead to an appreciation of the domestic currency. This appreciation makes tradable sectors, particularly manufacturing and exports, less competitive, thereby shifting resources toward non-tradable sectors and potentially harming long-term growth. See Findlay (1978) |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Sağlam and Yalta (2011) [73], searched for the effects of FDI on private and public investments as these are important determinants of economic growth between 1970 and 2009. They could not find a long-run significant relationship between FDI and investment. |

| 6 | For convenience, variables in logarithmic form are denoted with an ‘l’ prefix (e.g. ly = log(y)) |

| 7 | The Crash Model (Model A) is specifically selected as it allows for structural breaks in the intercept, reflecting sudden and permanent shifts in the level of the macroeconomic series. Given the economic history of Türkiye, major shocks—such as the 1980 liberalization reforms, the 1994 and 2001 financial crises—typically cause abrupt level shifts (intercept) rather than fundamental changes in the long-run growth rate (slope). By focusing on intercept shifts, Model A maintains greater parsimony and statistical power, avoiding the risk of over-parameterization. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.