Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Scope

2.2. Experimental Design and Scenario Setup

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulation

3. Results and Discussion

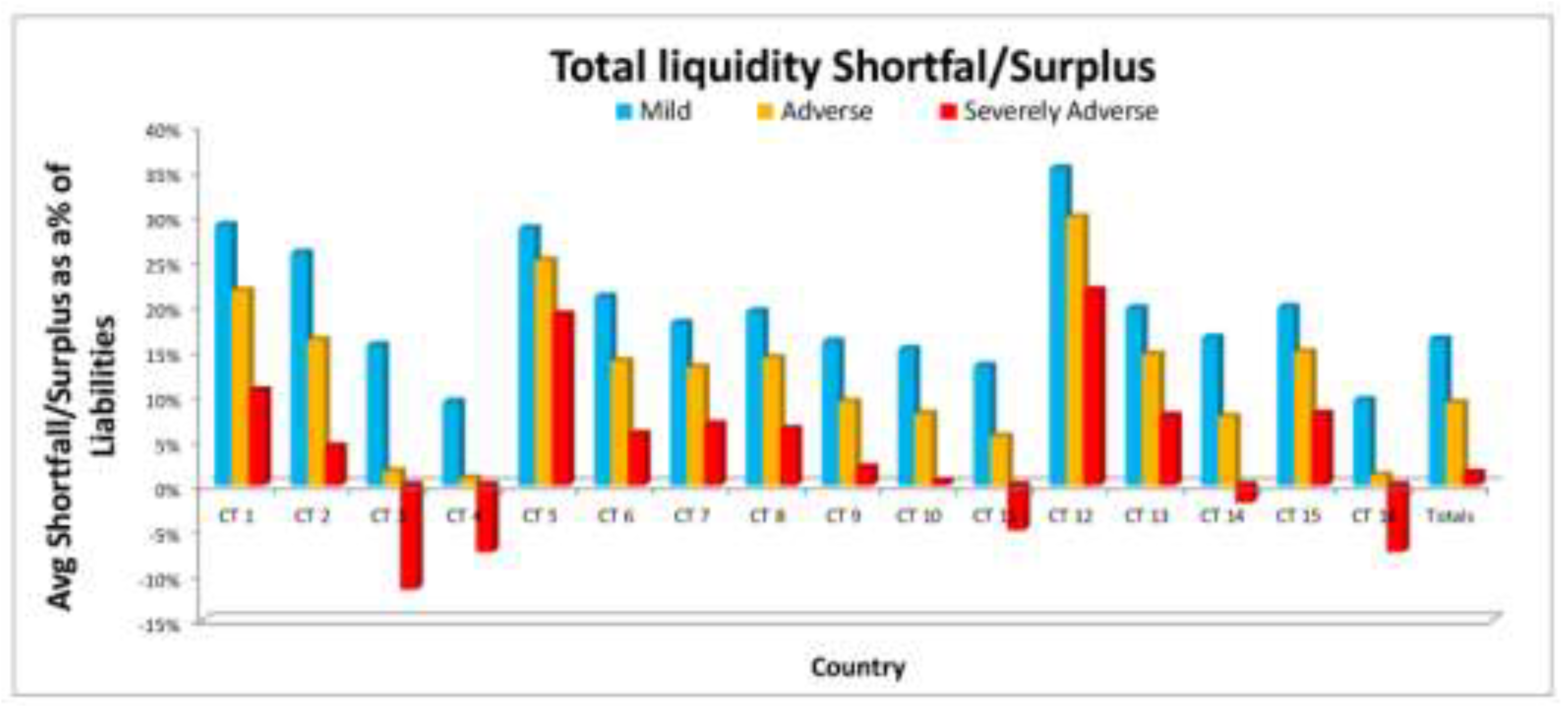

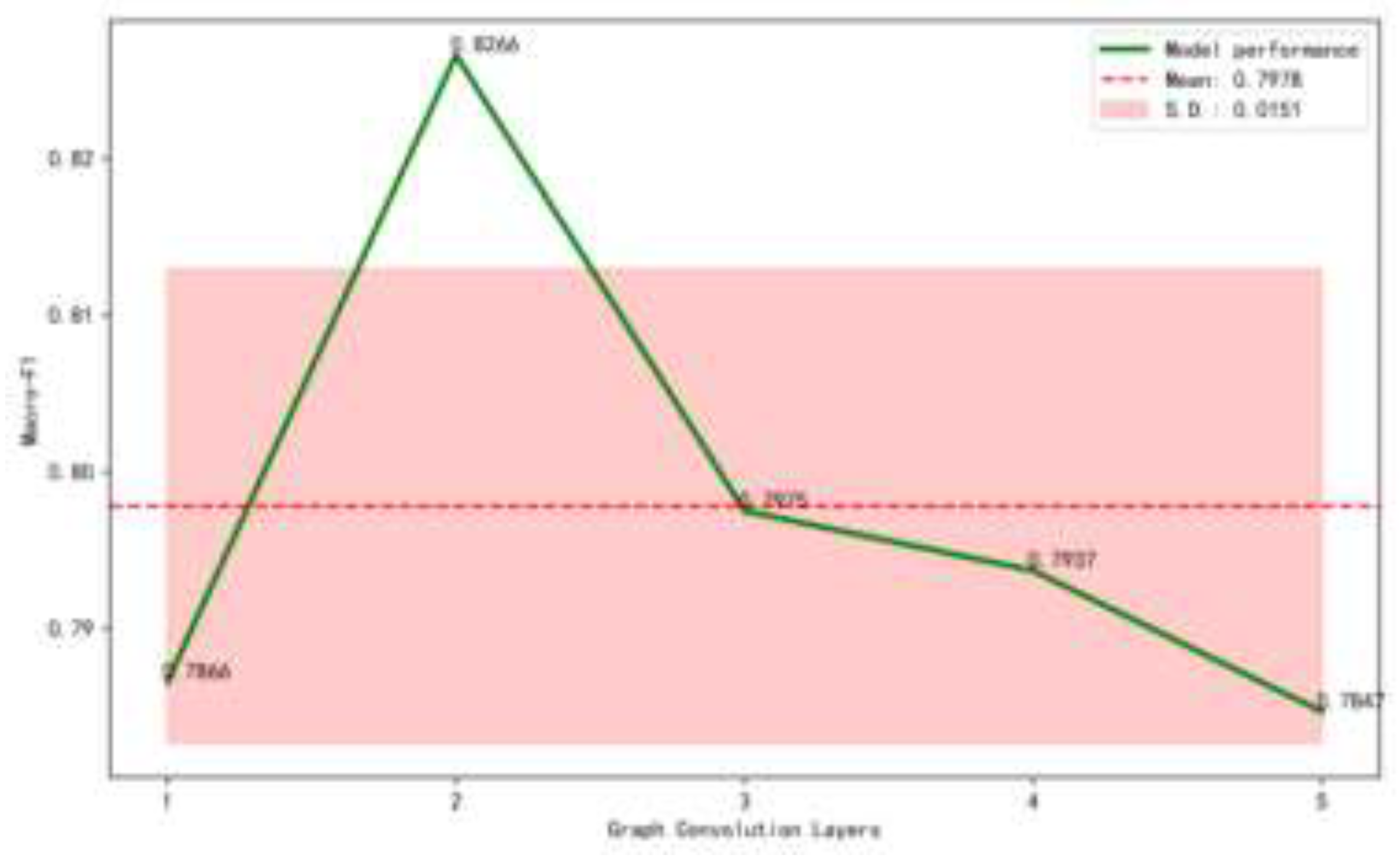

3.1. Baseline AML Performance and Liquidity Conditions

3.2. Threshold Tightening: Improvement in Detection and Reduction in Liquidity

3.3. Balanced Monitoring: Moderate Detection Gains with Limited Liquidity Impact

3.4. Robustness Checks and Policy Implications

4. Conclusion

References

- Koffi, B.A. Strengthening financial risk governance and compliance in the US: a roadmap for ensuring economic stability. The Edge Review Journal 2024, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, H. Multi-Task Temporal Fusion Transformer for Joint Sales and Inventory Forecasting in Amazon E-Commerce Supply Chain. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2512.00370. [Google Scholar]

- Kiettikunwong, N.; Sangsarapun, W. G-Token implications and risks for the financial system under state-issued digital instruments in Thailand. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2025, 18, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, M.; Corona, E.A.; Daniel, B.; Leuze, C.; Baik, F. VR MRI Training for Adolescents: A Comparative Study of Gamified VR, Passive VR, 360 Video, and Traditional Educational Video. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.09955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akartuna, E.A.; Johnson, S.D.; Thornton, A. A holistic network analysis of the money laundering threat landscape: Assessing criminal typologies, resilience and implications for disruption. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 2025, 41, 173–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsan, R.; Crawford, C. External validity and model validity: a conceptual approach for systematic review methodology. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014, 2014, 694804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, M. Optimization of Anti-Money Laundering Detection Models Based on Causal Reasoning and Interpretable Artificial Intelligence and Its Empirical Study on Financial System Stability. Optimization 2025, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, J.C. A comparative study of several classification metrics and their performances on data. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2023, 8, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Y. Research on Credit Risk Forecasting and Stress Testing for Consumer Finance Portfolios Based on Macroeconomic Scenarios. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, D.; Petersen, K.; Telep, C.W.; Fay, S.A. Can increasing preventive patrol in large geographic areas reduce crime? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Criminology & Public Policy 2024, 23, 721–743. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Hong, E.; Liu, S. Organizational Development in High-Growth Biopharmaceutical Companies: A Data-Driven Approach to Talent Pipeline and Competency Modeling. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, C.; Lelyveld, I.V.; Zymek, R. Banks’ liquidity buffers and the role of liquidity regulation. Journal of Financial Services Research 2015, 48, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yao, Y.; Yang, J. Real-Time Risk Control Effects of Digital Compliance Dashboards: An Empirical Study Across Multiple Enterprises Using Process Mining, Anomaly Detection, and Interrupt Time Series. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, R. Financial Statements, Banks’ Operations, and Systemic Risk. In The Green Banking Transition Manual: Navigating the Sustainable Finance Landscape; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 7–123. [Google Scholar]

- Aiyar, S.; Calomiris, C.W.; Wieladek, T. Bank capital regulation: Theory, empirics, and policy. IMF Economic review 2015, 63, 955–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W. Phishing website detection based on machine learning algorithm. 2020 International Conference on Computing and Data Science (CDS), 2020, August; ieee; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gourneni, S.R. Causal Machine Learning for Intervention Analysis in AML Systems: Beyond Correlation to Causation in Financial Crime Detection. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies 2025, 7, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yao, Y.; Yang, J. Optimizing Financial Risk Control for Multinational Projects: A Joint Framework Based on CVaR-Robust Optimization and Panel Quantile Regression. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pattabhiramaiah, A.; Sridhar, S.; Kanuri, V. Return on AI: A Decision Framework for Customers, Firms, and Society. In Firms, and Society; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, D.; Hsu, C.; Lively, C.; Morgan, J.; Schuermann, T.; Sekeris, E. Stress testing for commercial, investment and custody banks. Handbook of Financial Stress Testing 2022, 247. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).