Introduction: Shifting the Classical/Quantum Boundary

For a century, quantum mechanics has been perceived as a major conceptual break with classical physics (e.g. Omnès, 2000). However, in the context we are considering here, that of the construction of space and time to be understood within classical physics itself, we can see the situation differently: careful examination of the criteria traditionally used to mark the break reveals their partially contingent or derivative nature. Thus, discretization or quantification, non-commutativity, indeterminacy and indeterminism (with the widespread use of probabilities), superposition, the use of complex numbers, or even the use of specific functional spaces do not, taken in isolation, constitute irreducible conceptual boundaries. The microscopic/macroscopic distinction is also not a good criterion for separation: there are macroscopic quantum behaviors, and entanglement itself is now observed between systems separated by several hundred kilometers.

In a recent article, written prior to this text (Guy, 2026, where numerous references can be found

1), we presented a number of the above points in a technical manner, at the risk of losing sight of the overall logic. We now wish to present a condensed version of the conceptual thread of our approach, adding that the irreducible distinction between classical and quantum physics must be shifted to a more fundamental level than the one we had previously presented. Drawing on the relational epistemology of the co-construction of space and time, we show that the decisive question is

whether events can be considered independent. This possibility, far from being trivial, depends on a prior spatio-temporal and causal structuring. When this structuring is not yet established, the classical composition of probabilities loses its justification, and a nonlinear rule—of which Born's rule (1926) is the simplest form—becomes necessary.

We will follow the following plan. In the first part, we will present a minimal relational axiomatic system underlying the construction of space and time; in the second part, we will focus on the question of independence or dependence between events. Then (in the third part), we will take a more general look at the relationships between quantum and classical physics, as they arise from the previous developments. In the fourth part, we will revisit a number of characteristics that are supposed to be specific to quantum theory. We will conclude (in the fifth part) with a few words of conclusion. Our text is intended primarily as a contribution to the interpretation of quantum physics

2, without claiming to examine all relevant points, particularly those related to the functioning of mathematical formalism, measurements, and experiments. By the adjective

minimal, which we associate with the relational epistemology or axiomatics that we are developing, we mean that it offers a sufficiently general framework to allow a new look at the usual notions of quantum physics. The disadvantage of this approach is that it still seems imprecise: this article should be seen as a seed for future in-depth study, bearing in mind that a number of concrete applications have already been given in our works (see, for example, Guy, 2024, 2025).

1. A Minimal Relational Epistemology

The starting point for our quest for knowledge lies in what could be called a relational proto-physics, where physical quantities are not defined in relation to a given space and time, but on the basis of relationships between systems. The most primitive physical laws concern comparisons of movements

3, and not evolutions in a pre-existing spatio-temporal frame. From this perspective, space and time are co-constructed: they emerge as structures that allow these dynamic relationships to be organized, stabilized, and compared. As we have explained in our works, this emergence is as much a moment of choice (that of dividing between what changes and what does not change, depending on what interests us or what we are able to observe/measure), based on conventions (such as that of a decided standard of movement).

An important consequence of this approach is that no quantity has meaning in isolation. Minimal physical descriptions relate to

pairs of quantities (e.g., position–time; field–current; amplitude–probability flux; energy–duration, etc.), with the space–time pair enjoying no privileged ontological status. The minimal treatment of such conjugate pairs stems from the relational necessity, when expressing change, to rely simultaneously on a condition of fixity (which we associate with space) and a condition of mobility (which we associate with time), as neither can be affirmed alone without the other

4. In relativity theory, the treatment of four-vectors, or pairs of three-dimensional vectors, is one way of expressing this requirement. In the well-known pair {electric field - magnetic field}, the first field expresses a spatial point of view (we are situated in relation to

fixed electric charges) as opposed to the second, which is temporal (

moving charges), with both points of view only making sense in combination with each other (fixity is only a lesser form of mobility). Such conceptual symmetry prevents us from attributing

a priori to space or time a fundamental role separate from the other and paves the way for their joint construction. Some authors, such as Barbour (1999), have spoken of time as emerging from configurations; we present here a probabilistic and quantum extension of this, knowing that treating time separately from space does not correspond to our approach. The two quantities are on the same level, and the corresponding pair is equal to the other pairs in physics. The relational aspect of quantum mechanics as presented by certain authors (e.g., Rovelli, 1996) seems unsatisfactory to us, as space and time do not fulfill the above conditions

5.

We summarize this framework with the following axioms (named with the letter R, for relational):

The physical description primarily concerns

relations of change between systems, and not objects located in a pre-existing space and time frame. Physical relations are primary, with quantities being defined relative to these relations

6.

Any relevant physical quantity is defined at least by a pair of conjugate variables (f, g) representing, respectively, a relational configuration and an associated flow of change.

No pair of quantities (in particular the position-time pair) defines an a priori frame; all pairs are on the same ontological level and acquire a referential role only in relation to others.

The pairs (f, g) satisfy conservation laws expressing the overall consistency of relations (generalized continuity equations). Another way of expressing this consistency is to talk about composition between relational configurations

7 .

Space, time, causality, and locality emerge as stable structures resulting from the organization of relations and regimes of composition. Space and time are decided on the basis of comparisons of movements and do not constitute an a priori background.

This seems to us to be the conceptual framework of our approach, illustrated by concrete examples in all our work (see, for example, a recent summary concerning the "refreshment" of the theory of relativity, Guy, 2024).

2. Independence of Events and Causal Structure

We would like to emphasize a point here that we have not sufficiently addressed in our research: it concerns the residual separation (after the previous clarification) between quantum physics and classical physics. It is based on the notion

of independent events, which is rarely explicitly questioned in classical physics. It assumes several conditions: the possibility of individualizing events within relationships, determining their causal connections, and asserting the absence of mutual influence. However, these conditions are all based on the existence of a stabilized spatio-temporal composition. Relativity has shown that the independence of events is relative to a causal structure defined by light cones. This lesson is generalized here:

without a constructed space-time, the independence of events cannot be defined8.

When independence is accepted, probabilities add up. This rule, central to classical physics, is not a universal logical truth but a direct consequence of the postulate of independence. On the other hand, when this independence cannot be established, possible events can no longer be treated as mutually exclusive alternatives. The probabilistic composition necessarily becomes non-linear.

As we did above in relational axiomatics, we think it is interesting to formulate an axiomatic system of dependence/independence. Here it is, with axioms designated by the letter D (for dependence).

The physical description primarily concerns possible relationships between systems, prior to any construction of space, time, and localized events.

The notion of independent

9 events can only be defined on the basis of a reference structure (space, time, standard of motion) that allows domains of causality to be distinguished.

- -

When the independence of events is accepted, probabilities are added together (classical regime).

- -

When independence cannot be defined, the possibilities are combined before probabilistic evaluation, according to a nonlinear rule whose simplest form is quadratic (quantum regime, Born's rule, 1926).

Thus, this axiomatics clarifies axiom R1 above (through axiom D1, which refers to localized events), and also relates to axiom R5, which it must precede (axioms D2 and D3). Note the distinction between possibility (expressed before the definition of a space-time) and probability (expressed in a regime of causality)

10. Axiom D3 will be revisited and detailed in

Appendix A.

3. Epistemological Discussion: The Distinction Between Classical Physics and Quantum Physics

Within the framework thus constructed, the distinction between classical physics and quantum physics can be reformulated in a unified manner.

Classical physics: a regime in which space and time are constructed, causality cones are defined, and the possible independence of events is postulated; probabilities are added together. In classical physics, events are implicitly assumed to be independent as long as they are appropriately separated in space or time. This independence is mathematically expressed by the additivity of probabilities: the probability of an alternative is the sum of the probabilities of the exclusive cases. This structure is based on two assumptions: - events can be individualized, - their possible mutual influence can be evaluated from a given causal structure. However, these assumptions are precisely those that are not yet available in a relational framework prior to space-time.

Quantum physics: this is a priori a regime in which space and time are not yet fully stabilized; the independence of events cannot be asserted, and probabilities result from a nonlinear composition of possibilities. If we refuse to postulate the independence of events—not on metaphysical grounds, but because there is no structure that allows us to define it—then the classical additivity of probabilities is no longer justified. Possibilities can no longer be treated as mutually exclusive alternatives; they must be composed before any probabilistic evaluation can be made. It is in this context that quantum mechanics appears naturally, not as an ontological break but as a descriptive regime prior to spatio-temporal stabilization allowing causal independence (we will then refer to it as pre-quantum physics, see below). Born's rule, according to which probability is given by the square of the modulus of an amplitude resulting from the sum of possibilities, can be interpreted as the simplest form of probabilistic composition in the absence of event independence. It does not express vagueness or ignorance, but a structural dependence between possibilities. Thus, the characteristic non-linearity of quantum probability is not a mysterious addition, but the direct consequence of the rejection of causal independence at a more fundamental level. Gleason (1957) shows that the quadratic rule is not arbitrary once a projective and non-contextual structure is imposed.

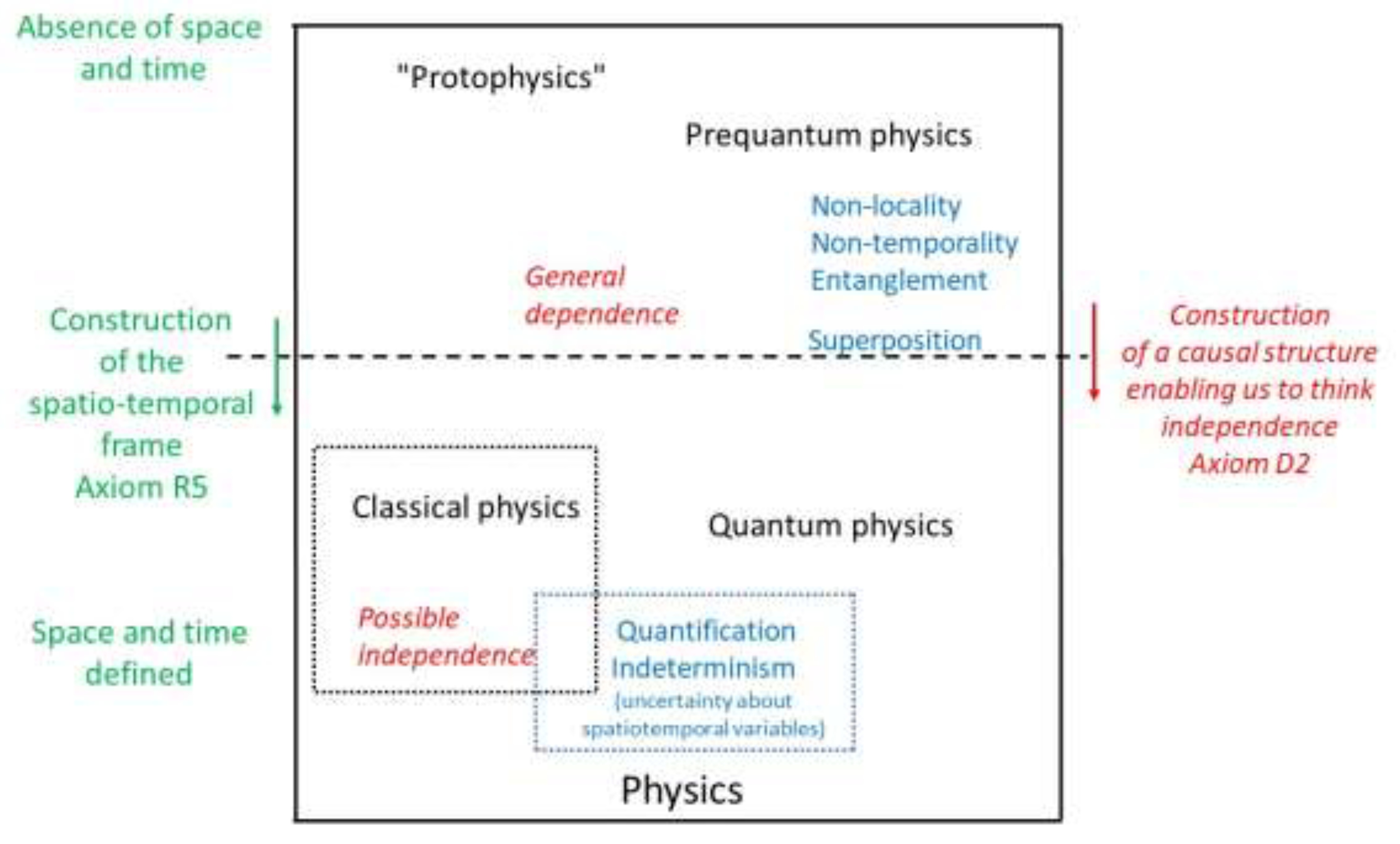

Graphical representation. We need to refine the previous distinction. Quantum physics does not remain completely prior to the construction of space-time; it needs it in order to express itself and its formalism. But it has put us on the path to an upstream stage that it continues to inhabit, unlike classical physics, which remains isolated from it. Thus, it encompasses classical physics while communicating with a non-local and non-temporal physics. We represent this topology graphically (

Figure A1). The different domains of physics are positioned relative to each other within a vast territory. The vertical dimension represents the "progression" of the axioms we have stated (from top to bottom); it is separated in two by the break (dotted horizontal line) marking the construction of a space-time (axiom R5), or equivalently a causal structure allowing us to think of the independence of events (axiom D2). Above this line, we can speak of a proto-physics or pre-quantum physics preceding the construction of space and time

11. Below, classical and quantum physics share the map (and are positioned next to each other along the horizontal dimension). Quantum physics encompasses classical physics: it has a classical layer using space and time variables, but continues, in an underlying layer, to accommodate a possible generalized dependence between events. In this respect, it communicates with the top of the plane. Non-locality and non-temporality are primary, although we need space and time to describe them. There is no clear boundary between the two types of physics. As will be reiterated, quantification and indeterminacy are not specific to quantum physics and are indicated as straddling the latter and classical physics.

4. A New Look at the Characteristics Usually Associated with Quantum Physics

In this very general scheme, we can revisit and situate a number of physical characteristics that were discussed in our first article (Guy, 2026). We list them in

Figure A1. By re-reading them in light of the previous axioms, we place ourselves at their foundations. For each of them, we will repeat like a refrain their change of status during the stabilization of a space-time reference frame (axioms R5/D2).

4.1. Quantification and Indeterminacy: Effects Derived from the Stabilization of Space and Time

Two characteristics are often presented as specific to quantum mechanics: quantization (or discretization) and indeterminacy (as well as the associated indeterminism).

Quantization: neither a fundamental criterion nor exclusive to quantum mechanics. The discretization of certain physical quantities is historically associated with the birth of quantum mechanics, particularly through the quantization condition introduced by Planck. However, from a formal point of view, the appearance of discrete spectra is by no means unique to quantum theory. It is already present in many contexts of classical physics, particularly in the solutions of partial differential equations subject to boundary conditions (vibrating strings, electromagnetic cavities, eigenmodes of constrained systems; hyperbolic systems, as discussed in our first article). In the framework proposed here, this observation is given a unified interpretation: quantization appears when a sufficiently stabilized global structure imposes compatibility constraints on physical processes. It is therefore linked to the existence of a domain, boundaries, or more generally, large-scale coherence conditions. In this sense, quantization is an effect of structural stabilization, not a primitive ontological feature.

In a pre-spatio-temporal regime, where neither space nor time are yet constituted as stable frames of reference, there are no boundary conditions in the classical sense. Possible processes are not organized into discrete modes, but form a continuous set of potential relationships. Quantification only appears when space-time emerges as a structure sufficiently coherent to select certain stable modes over others.

This interpretation also allows us to relativize approaches that postulate the existence of minimal quanta of space or time. Such a hypothesis amounts to prematurely reifying an emerging structure and poses serious conceptual difficulties, particularly with regard to relativity and its effects of dilation and contraction. In the relational framework adopted here,

space and time have no fundamental granularity12 ; any possible discretization is effective and contextual.

Indeterminacy: from structural indefiniteness to uncertainty relations. Indeterminacy is another emblematic feature of quantum mechanics, often embodied by Heisenberg's relations. These are generally interpreted as expressing a fundamental limit to the simultaneous knowledge of certain pairs of quantities, such as position and momentum.

We have given an initial interpretation of this by broadening the perspective in the form of

relations of a-certainty (Guy, 2014), in which the Lorentz transformation plays a key role. Aspects of indeterminacy and probability are encountered on the classical side as soon as we consider a certain degree of uncertainty about the variables of space and time, as these two parameters may be subject to poor knowledge. Because of this commonly understood indeterminacy, the

representation of physical quantities in a spread-out rather than point-like

manner (as would be the case for a position x

0 marked by a Dirac δ(x – x

0)) leads us to a property such as

superposition, where a given quantity can be understood as having several values. The quality of superposition straddles the horizontal boundary of

Figure A1 insofar as the probability regime associated with it does not necessarily accommodate independent events.

In the framework developed here, this interpretation can be refined. In a regime prior to the emergence of space and time, there are not yet any well-defined variables to which precise values can be assigned. Indeterminacy should therefore not be understood as a blurring of existing quantities, but as a structural indefiniteness: the very impossibility of simultaneously defining certain distinctions.

When space and time stabilize, physical quantities become definable, and some of them naturally appear in conjugate pairs. The non-commutativity of the operations associated with these quantities then becomes operative (see section 4.2. below), and indeterminacy takes the precise form of uncertainty relations. These are not primary, but constitute the formalized trace of the previous regime of relational indefiniteness.

Indeterminism and the emergence of events. Quantum indeterminism is often perceived as a radical break with classical determinism. From the perspective adopted here, it appears rather as a consequence of the mode of emergence of events. As long as space and time are not stabilized, there are no individualized events that can be causally ordered or predicted. There is therefore no point in talking about determined trajectories or outcomes. When events become definable, their selection nevertheless retains traces of the initial non-independence of possible processes. Quantum indeterminism is therefore not the expression of a fundamental arbitrary randomness, but the residue of a regime in which the possibilities were not yet separable. In this sense, it is post-eventual, not primordial.

4.2. Non-Commutativity of Observables and Independence of Events

The non-commutativity of observables is often presented as a fundamental distinctive feature of quantum mechanics. In the standard formulation, it manifests itself in relations of the type, leading to uncertainty relations and the impossibility of simultaneously defining certain quantities. In the relational framework adopted here, this non-commutativity is not considered a first principle, but rather a deeper structural consequence. It expresses the fact that physical operations (preparation, evolution, comparison) cannot be treated as independent events when the spatio-temporal and causal structure has not yet stabilized.

In classical physics, the commutativity of observables implicitly reflects the postulate that quantities coexist in a given space-time, and that measurement operations can be ordered without mutual influence. Quantum non-commutativity, on the contrary, signals the failure of this postulate: the order of operations matters because they themselves participate in the process described. Understood in this way, non-commutativity appears as a symptom, rather than the primary cause, of quantum behavior. It is the operational expression of the non-independence of events, which is also manifested by the need to combine possibilities before any probabilistic evaluation, in accordance with Born's rule.

4.3. Superposition, Entanglement, and Non-Factorization: A Minimal Formal Reading

The notions of superposition and entanglement are compatible with the relational epistemology adopted in this article and independent of any prior spatio-temporal interpretation.

States, composition, and non-factorization. Let us consider a space for describing possible processes. In a pre-spatio-temporal regime, states do not represent localized configurations, but

possible global relationships. The essential structure of

is that of a vector (or projective) space, allowing for the linear composition of possibilities. A general state is then written as a combination

where the

do not yet correspond to exclusive events, but to partial relational contributions, along which

coordinates are defined. This linear structure does not imply any immediate probabilistic interpretation; it only encodes the possibility of composing processes. It should not be taken in a strictly mathematical sense; its meaning is symbolic, a way of writing relations between phenomena in a compact form that prefigures the mathematical relations written in a defined space-time.

Superposition as primitive composition. In this context, superposition is not an exceptional phenomenon, but the normal form of description. It expresses the fact that possible processes are not separable before the constitution of a causal structure. At this stage, therefore, there is no privileged basis for interpreting the decomposition of as an exclusive alternative between states. Superposition is thus interpreted as modal non-separability: several relational contributions jointly participate in the description of the overall process.

Entanglement and non-factorization. Consider an abstract decomposition of the system into substructures

and

. A state is said to be factorizable if

where the symbol

denotes the tensor product, which takes its place before the spatiotemporal regime. In the latter, such factorization is generally not possible. Generic states are

non-factorizable, which corresponds to what quantum mechanics calls entanglement. In this reading, entanglement does not describe a correlation between spatially separated systems, but rather the structural impossibility of decomposing the global relational description into independent descriptions.

Spatio-temporal stabilization and emergence of observables. When space and time emerge as stabilized structures, certain decompositions become physically relevant. Subsystems can be defined, privileged bases appear, and factorization becomes approximately possible. In short, superposition and entanglement formally persist, but their effects become partially unobservable, in particular through the erasure of interference and decoherence. In the context just described, superposition and entanglement appear to be specific properties of quantum mechanics, whereas in reality they are structural residues of a more fundamental regime of non-separability.

4.4. On the Notion of Probability Before and After the Emergence of Space and Time

The nonlinear regime of probabilities is rooted in the pre-quantum part of our representation: the notion of fundamental randomness is a way of talking about this space connected before space-time. Probability plays a central role in both classical physics and quantum mechanics, but its conceptual status is profoundly different in each. We can distinguish between two regimes for defining probability: one prior to the emergence of space and time, and one subsequent to it, in which these structures are stabilized.

Probability and events: an often implicit assumption. In the classical presentation, probability is generally defined as a measure on a set of events. It is then interpreted either as a limit frequency or as a measure of ignorance concerning well-defined facts. This conception implicitly rests on several presupposed assumptions: the existence of individualizable events, their possible independence, and a spatio-temporal structure that allows them to be ordered and repeated.

However, these assumptions are not universal. They are only fully justified in a framework where space and time are already constructed, and where a causal structure makes it possible to distinguish between domains of influence and non-influence. Classical event probability thus appears as a derived notion, dependent on a prior organization of the physical world.

Probability in a pre-spatio-temporal regime. In a regime prior to the emergence of space and time, such as that envisaged in relational epistemology, events in the classical sense do not yet exist. Physical possibilities

13 are not separated into exclusive alternatives, and it is not possible to postulate their independence. In this context, probability cannot be understood as a frequency or as a direct measurement of events. It must be interpreted as a

weighting of possibilities, or more precisely as a measure of the relative weight of potential processes before their individualization. Probability is therefore structural or processual in nature: it qualifies possibilities that are still intertwined, rather than results that have already been distinguished.

Role of amplitudes and composition of possibilities. The lack of independence of possibilities in this regime imposes a rule of prior composition. The contributions of the various possible processes cannot be directly added together at the probabilistic level. This is why the description involves amplitudes, mathematical objects that allow for a coherent composition of possibilities before any probabilistic evaluation. Born's rule then acts as a transition principle: it provides a prescription for associating a probability with a composite process. Probability is not primary; it is obtained after the composition of amplitudes, as a normalized measure of all compatible possibilities. From this perspective, quantum probability does not express ignorance about the hidden events, but rather the very structure of possible relationships in a regime where event independence is not yet definable.

A significant body of literature is devoted to the question of probabilities in quantum physics. We refer to a few works that partly overlap with our own intuitions. Primas (1990) analyzes the role of mathematical structures in the interpretation of physical probabilities. Reichenbach (1956) analyzes the link between causality, temporal order, and probabilities (the independence of events presupposes a prior temporal structure). Gell-Mann and Hartle (1993) share our approach in that they believe probability is linked to global dynamic structures. Wigner (1932) understands probabilities as projections of invariant measures, particularly in the semi-classical limit. von Neumann (1932) proposes a spectral formulation of observables and quantum probabilities that makes possible a non-psychological interpretation of probability. The present work offers a dynamic and transversal reading of this. Schnirelman (1974) shows that quantum spatial densities can be understood as statistical manifestations of classical invariant measures, reinforcing the idea of structural rather than spatial probability.

Probability after the emergence of space and time. When space and time emerge as stabilized structures resulting from comparisons of movements, events can be individualized and located relative to one another. Causal cones then make it possible to define, at least approximately, independent events. In this regime, probability changes status. It becomes a measure on a set of exclusive events, additive for independent alternatives, and susceptible to a frequency interpretation. The classical rule of adding probabilities regains its validity, not as a universal law, but as a consequence of the postulate of independence made possible by spatio-temporal structuring.

Conceptual continuity between the two regimes. There is no opposition, but rather conceptual continuity between these two notions of probability. Quantum probability can be understood as a probability

before events, while classical probability is a probability

on events. The transition from one to the other corresponds to the emergence of causal independence, the effective elimination of the non-commutativity of operations, and the observable disappearance of interferences. In

Appendix A, we propose a succinct axiomatic system to express this, where we emphasize aspects of invariance not mentioned here.

Space and probability. The probabilistic link between aspects of quantification and space/time is another way of describing the previous approach. We are led down the path of probability by comparing the spatial distributions occupied by a given quantity in relation to the entire space, whether when solving Schrödinger's equation or problems governed by hyperbolic partial differential equation systems, as discussed in Guy (2017, 2026

14). For his part, Zusman (2021) refers to a random space.

4.5. On the Problem of Measurement and Decoherence

In the standard formulation of quantum mechanics, the measurement problem is generally presented as a break between two heterogeneous regimes: on the one hand, a unitary, linear, and reversible evolution of states (e.g., described by Schrödinger's equation), and on the other hand, an irreversible measurement process leading to the selection of a single result. This break is often interpreted as a conceptual flaw in the theory or as evidence of a missing physical mechanism.

In the relational framework proposed here, this difficulty is naturally reformulated. The unitary regime is no longer interpreted as the evolution of a system already located in a given space-time, but as the dynamics of the composition of possibilities in a pre-eventual regime, prior to the stabilization of space and time. At this level, superpositions do not describe a multiplicity of coexisting realities, but the very absence of separation between alternatives that are not yet individualized.

The measure then corresponds not to a dynamic break within the theory, but to a change in the descriptive regime: the emergence of individualized events made possible by the stabilization of a spatio-temporal and causal framework. The irreversible selection of a result no longer appears as a violation of unitarity, but as the condition for the emergence of the regime in which the very notion of result, event, and additive probability makes sense.

Understood in this way, the question of measurement requires neither additional postulates nor ad hoc mechanisms. It is a natural consequence of the transition from a relational regime without independent events to an event-based regime, which largely dissolves the traditional opposition between unitary evolution and wave packet reduction.

The theory of decoherence rigorously accounts for the effective erasure of interference and the stabilization of classical behavior when quantum systems are coupled to a macroscopic environment. However, it operates within a framework where space and time, as well as the distinction between system and environment, are already assumed to be established. Decoherence does not select a singular event and does not, on its own, constitute a complete solution to the measurement problem. In the relational framework proposed here, it appears as a secondary mechanism for consolidating the event regime, intervening after the stabilization of the spatio-temporal framework, and not as the fundamental principle of the transition from quantum to classical.

4.6. The Question of Thermodynamic Irreversibility

This question deserves to be placed in a relational perspective. The statement of the second law, according to which the entropy of an isolated system can only increase until equilibrium is reached, presupposes not only the existence of a state of equilibrium, but also an effective process leading to it. However, quantum mechanics reminds us that, in practice, there is no such thing as a strictly isolated system: any effective description implies couplings, even weak ones, with an environment (see Gemmer et al. 2004). In this context, the irreversible evolution towards equilibrium should not be interpreted as a mysterious property of microscopic dynamics itself, but as the result of external perturbations, uncontrolled correlations, and information losses related to these couplings (see also Guy, 2020). The duality between reversible microscopic dynamics (classical or quantum) and irreversible macroscopic evolution thus finds a unified interpretation: irreversibility is not primary, but emerges from a relational description in which the complete independence of the system is an idealization. Irreversibility is rooted in the pre-quantum domain, but it can only be expressed in words in the zone where space and time are stabilized. We can then speak of reversibility, which will allow us, by negation, to name irreversibility. This interpretation brings together the understanding of the second law in classical physics and quantum physics, without invoking any additional conceptual break. Thermodynamic irreversibility appears to be one of the conditions that makes the emergence of time itself possible. The arrow of time is formed when irreversible interactions and environmental couplings make an effective order of evolution possible. The growth of entropy does not therefore presuppose a pre-existing time; on the contrary, it marks the stabilization of a temporal regime.

4.7. Choice of Representation Bodies (C) and Functional Spaces

The choice of the body ℂ. The use of complex numbers is often presented as a specificity of quantum mechanics, linked to phase, interference, and superposition. But this mixes two levels: the structural level (which is conceptually irreducible) and the representational level (how this structure is encoded). In our approach, what is irreducible is not ℂ, but the need to compose possibilities before associating them with a probability. In other words, we need a structure that allows for addition, composition, and the presence of relative information (orientation, phase, order). Complex numbers are the simplest way to meet this requirement, but they are not the only one. In our framework before space and time, processes are not ordered, but their composition depends on their mutual relationship. Phase is an internal relational variable that encodes the compatibility or incompatibility of possible contributions. Classical physics can be written on ℂ (complex waves, analytical mechanics, Fourier transforms), but in classical physics, phase is redundant; it has no probabilistic role, as events are already independent. Writing classical physics on ℂ does not introduce Born's rule, probabilistic interference, or significant operational non-commutativity. ℂ is not sufficient for quantum physics, and is not necessary for classical physics.

Functional spaces: continuity, Dirac, distributions. A classical "point" state corresponds to a Dirac distribution, a quantum state corresponds to a spread-out function (we discussed this in section 4.1.), but this distinction is mathematical, not ontological. What is not fundamental are the oppositions between continuous/discontinuous, function/distribution, and regularity of the functional space. All of this relates to the regime of description, the degree of stabilization, and the operational approximation. What is fundamental, on the other hand, is whether or not states can be superimposed before any event-based interpretation. However, a Dirac distribution does not superimpose in a physically meaningful way, whereas an amplitude does. Here again, it is not regularity that counts, but linearity interpreted at the level of possibilities, not events.