1. Introduction

The fovea, being the central part of the macula, possesses a unique microstructure. The characteristic pit, formed by the displacement of the inner retinal layers, the maximal density of cone photoreceptors, and minimal light scattering provide optimal conditions for photopic (daylight) vision [

1,

2]. Individual variations in foveal pit morphology are common in the normal population [

3], making an accurate understanding of its normative, non-pathological aging trajectories crucial for differential diagnosis from early-stage disease.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has become the standard for in vivo visualization of retinal microstructure. Aging is known to be associated with progressive thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer, the ganglion cell complex, as well as choroidal atrophy [

4]. However, data on the sensitivity of fine foveal parameters, such as pit configuration, foveal thickness, and the integrity of the photoreceptor outer segments, to age-related changes remain inconsistent.

Of particular interest is the foveal bulge-a convex configuration of the photoreceptor outer segment and ellipsoid zone complex at the center of the foveola [

5]. Its presence is considered an indicator of structural photoreceptor integrity and correlates with better functional outcomes in various macular pathologies [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Despite its potential clinical significance, population data on the age-related dynamics of this feature's prevalence are limited.

Traditionally, modeling retinal aging has been based on chronological age [

10]. Recently, the concept of biological age has been proposed as a more accurate reflection of cumulative physiological wear and tear and tissue-specific processes [

11]. Since photoreceptors, especially the cones of the foveola, have extremely high metabolic demands [

12], their microstructure may be particularly sensitive to systemic markers of biological aging, such as oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.

One of the most validated measures of biological age is PhenoAge—an algorithm that integrates information from 9 clinical and biochemical markers along with chronological age, and has proven its prognostic value for mortality and age-associated diseases [

13]. Hypothetically, PhenoAge could capture subtle changes in the metabolically active fovea earlier or more accurately than chronological age.

Rather than assuming the superiority of biological age over chronological age, this study aims to test the extent to which foveolar microstructure follows systemic biological aging versus chronological time in healthy adults. Identifying parameters that deviate from chronological synchrony may provide insights into retinal resilience and vulnerability to age-related remodeling.

The aim of this study is to conduct a comparative analysis of the associations between a comprehensive set of OCT-derived parameters of the foveola and both biological (PhenoAge) and chronological age in a cohort of healthy adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

This cross-sectional analysis utilized data collected as part of the RussAge research project. The sample consisted of 154 healthy Caucasian volunteers (308 eyes) aged 22 to 89 years. The study was conducted at the M.M. Krasnov Research Institute of Eye Diseases in collaboration with the Russian Gerontological Research and Clinical Center, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University (RNRMU). The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (protocol No. 59 from 13 September 2022). All participants provided written informed consent, and the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria were: age ≥18 years, ability to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were applied to establish a cohort healthy in terms of retinal and systemic status:

Any current or past ophthalmic pathology: refractive errors exceeding ±3.0 diopters, best-corrected visual acuity of 0.8 (Snellen) or worse, cataract, glaucoma, uveitis, diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, retinal vascular occlusion, optic neuropathy.

History of intraocular surgery (except for uncomplicated cataract surgery performed more than 6 months prior).

Systemic diseases potentially affecting the retina or metabolism: diabetes mellitus of any type, autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus), active oncological disease or a history of chemotherapy, diagnosed dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination score < 24) or severe psychiatric disorders.

Poor-quality OCT scans (image quality < 90%, motion artifacts, improper centration).

2.2. OCT Imaging and Image Analysis

All participants underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination, including visometry, autorefractometry, and slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the anterior segment and fundus.

Scanning Protocol: Macular imaging was performed by a single operator using the same device, the swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) with a high-definition raster (‘HD Raster’) scan protocol (Triton DRI OCT, Topcon, Japan). All scans were performed through undilated pupils under mesopic lighting conditions using the internal fixation target.

Image Analysis and Segmentation: Automatic segmentation of all retinal layers was performed using the device's built-in software (version: IMAGEnet 6 Version 1.32.18683). The quality of segmentation and centration for each scan was manually verified by two independent graders masked to participant age. In cases of incorrect automatic segmentation (less than 3% of scans), manual boundary correction was performed, followed by consensus. The method was preliminarily validated by comparing its results with those from fully manual segmentation performed by five retinal experts, showing a high degree of agreement (coefficient of intraclass correlation >0.95 for all analyzed thicknesses).

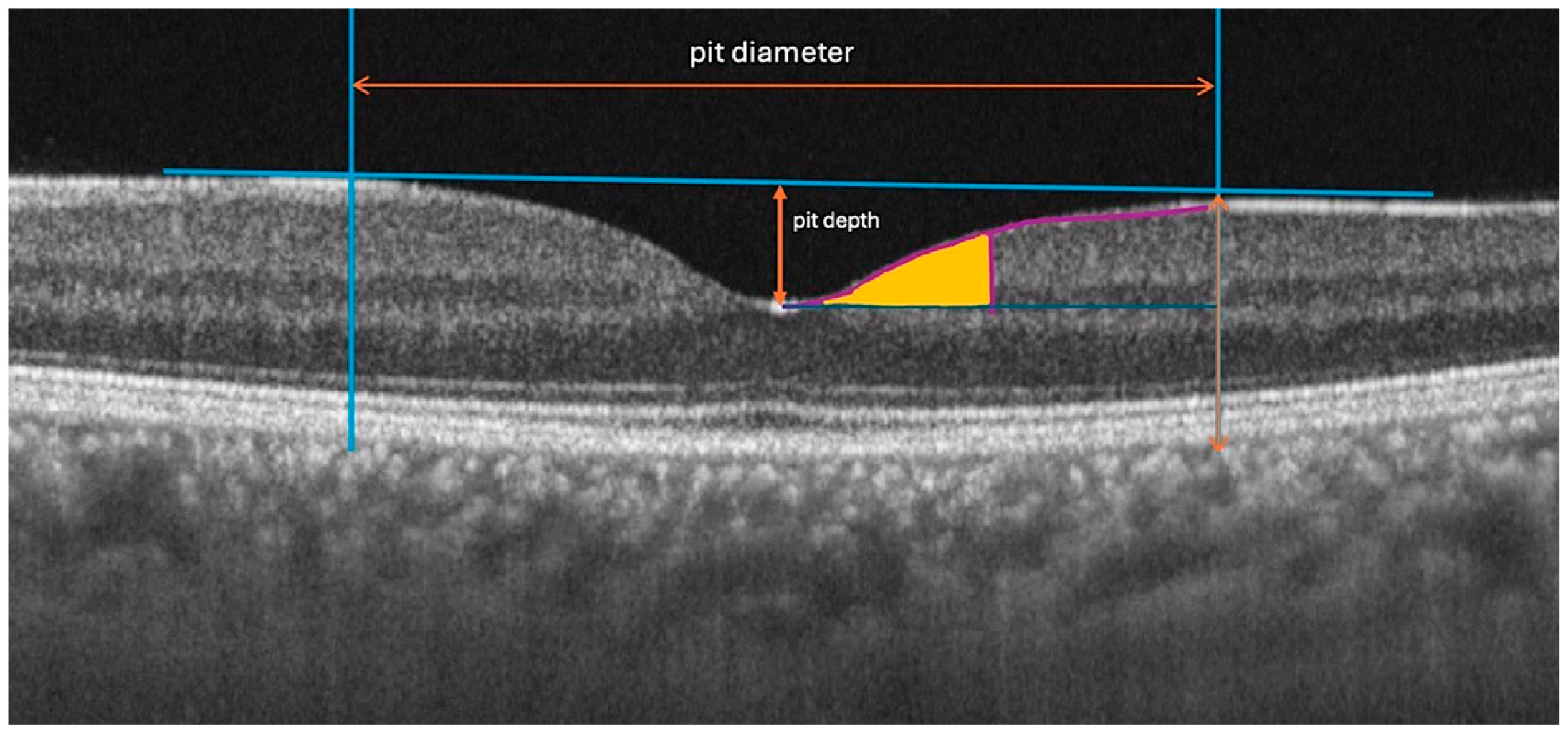

The following quantitative and qualitative parameters were derived from the scan data, defined relative to the anatomical center of the fovea (

Figure 1):

Central Foveal Thickness (CFT): The average retinal thickness within the central 1-mm diameter circle.

Foveal Pit Depth: The vertical distance between the pit's floor (the point of minimum thickness of the internal limiting membrane, ILM) and a reference plane connecting its edges. The edges were defined as the points where the first derivative of the ILM profile reached 50% of the maximum slope value.

Foveal Pit Diameter: The horizontal distance between the two edges defined above.

Mean Foveal Pit Slope: The mean absolute angle of the pit walls between its edge and floor as described in previous studies [

1,

14].

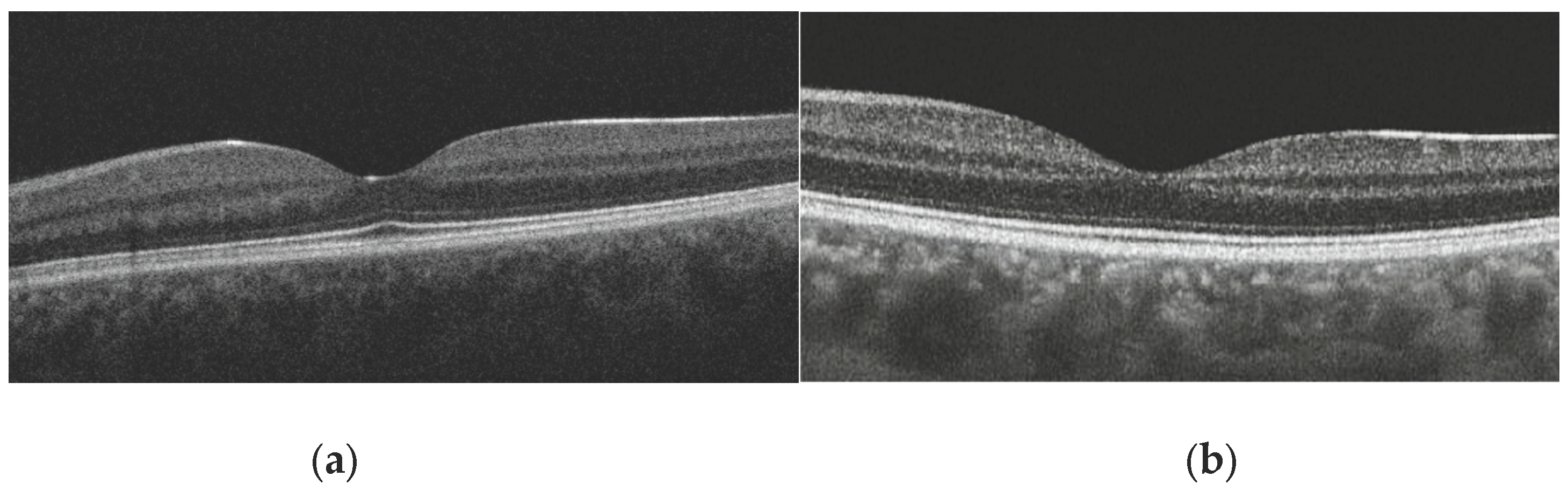

Presence of Foveal Bulge: This was assessed visually by two independent graders on magnified B-scan tomograms passing through the foveal center (

Figure 2a,b). The bulge was defined as a visible convexity (towards the vitreous) of the ellipsoid zone (EZ) line or the EZ-outer photoreceptor segment complex. In cases of disagreement (<2 % of cases), a joint discussion with a third senior expert was held for a final decision.

2.3. Biological Age Assessment (PhenoAge)

The biological age for each participant was calculated using the PhenoAge (phenotypic age) algorithm, as described by Levine et al. (2018) [

13]. The following nine clinical-laboratory biomarkers, measured as part of a general clinical check-up in a single certified laboratory, were included in the analysis: albumin, creatinine, glucose, C-reactive protein, lymphocyte percentage, mean red cell volume, red cell distribution width, alkaline phosphatase, and white blood cell count. Chronological age was also included in the formula. The calculation was performed using the published regression coefficients. The resulting PhenoAge value is expressed in years and can be either lower or higher than the chronological age, reflecting decelerated or accelerated biological aging, respectively.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Data Description and Group Comparison

Quantitative variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges: Me (Q1; Q3). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test (W) was used to compare parameters between the right and left eyes. Categorical variables are described with frequency and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences between age groups were assessed using the chi-square test.

2.3.2. Modeling Age-Related Variables

Age-related patterns of retinal parameters were analyzed using a stepwise approach, with the optimal model selected based on the Akaike information criterion. For each parameter and two types of age (chronological and biological), three models were tested:

Constant model (null hypothesis) — no age dependence: y = β0

Linear regression — monotonic age dependence: y = β0 + β1 × age

Generalized additive models (GAM) — nonlinear dependence: y = β0 + s (age, k), where k is the dimension of the spline basis (values of 5, 10, 15, and 20 were tested)

Based on the selected model, the predicted mean values (fit) were calculated for each age in 1-year increments (for the constant model, this is the overall mean for the sample; for the linear model, this is the value on the straight line; for the GAM, this is the value on the spline curve). To assess accuracy, 95% confidence intervals and 95% predictive intervals (PIs) were calculated (defining the expected range of values, which can be considered as the age-specific reference range). CIs and PIs were calculated using the t-distribution and residual degrees of freedom (df = N-1 for the constant model, df = N-2 for the linear model, df ≈ N - edf for the GAM, where edf is the effective degrees of freedom of the spline).

For clinical interpretation, the results were grouped into four age categories. Mean values for each group were obtained by averaging the model predictions across all integer ages in the group.

The statistical significance of age-related relationships was assessed using the p-value (for GAM, the p-value of the smoothing term of the spline; for the linear model, the p-value of the β1 coefficient; for the constant model, the p-value of the F-test of the ANOVA when compared with the linear model).

2.3.3. Correlation Analysis

For parameters with a linear age-related relationship, the Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) was additionally calculated to assess the strength of the relationship. The Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons.

Effects were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. P values in the range of 0.05–0.1 were interpreted as indicating a tendency toward the presence of an effect. Statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language (version 4.4.2; R Development Core Team, 2012; Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

Data from 154 participants (right eyes) were included in the final analysis. Demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The age distribution was uniform, covering young, middle-aged, and older adults. The mean chronological age was 49.5 years (SD ±15.8), and the mean biological age (PhenoAge) was 45.9 years (SD ±13.2). A strong correlation between the two-age metrics (r = 0.92, p < 0.001) confirmed overall consistency, yet the observed scatter (PhenoAgeAccel, the difference between PhenoAge and chronological age) indicates individual variations in the rate of aging within the patient sample.

No statistically significant differences between the right and left eye were found for any of the key structural foveolar parameters (p > 0.05 for all comparisons using the Wilcoxon test) (

Table 2). The exception was the average macular thickness, which was not a primary parameter in this study. Based on this finding, only data from the right eye were used for all subsequent analyses to maintain the independence of observations.

Analysis using constant, linear, and nonlinear (GAM) models showed that the primary parameters describing the geometry of the foveal pit had no significant age-related dependence (

Table 3). For all four parameters (thickness, depth, diameter, slope) and for both age measures (chronological and biological), the optimal model based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) was the constant model (p > 0.1 for all linear and nonlinear terms). This indicates the structural stability of the core foveal architecture throughout adulthood in the studied sample of healthy participants.

In contrast to the geometric parameters, the prevalence of the foveal bulge demonstrated a pronounced negative age-related dependence. Logistic Regression: Each year of increase in chronological age was associated with a 4% reduction in the odds of the bulge being present (OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94 – 0.98, p < 0.001). A similar, but slightly stronger, association was observed for the biological age PhenoAge (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93 – 0.97, p < 0.001).

When divided into age quartiles, the prevalence of the bulge decreased from 80.8% in the youngest group (lowest quartile, ≤44 years) to 53.0% in the group over 60 years for chronological age. For PhenoAge, the trend was even more pronounced: from 80.7% in the group with the lowest PhenoAge to 0% in the group with the highest PhenoAge (>74 conditional years), although the latter estimate is based on a small subgroup (n=3).

The predicted age-related trajectories for all parameters, derived from models using chronological age and PhenoAge, were practically identical (see overlapping confidence intervals in

Table 3). The correlation between the predicted parameter values for the two age types exceeded 0.99 for all continuous variables. In logistic regression for the foveal bulge, models with different age types showed comparable explanatory power (AIC differed by less than 2 units). Thus, in this sample, biological age (PhenoAge) did not reveal fundamentally different or stronger associations with the structural parameters of the foveola compared to chronological age.

4. Discussion

The present study provides a nuanced view of retinal aging by demonstrating that, in healthy adults, most geometric features of the foveal pit remain remarkably stable and closely synchronized with chronological time. Importantly, the absence of added predictive value of biological age does not diminish the relevance of the findings but instead highlights the robustness of foveal architecture under physiological aging conditions.

The main results revealed two divergent patterns: structural conservation of the main geometric characteristics of the foveal pit and pronounced age-related sensitivity of a qualitative feature such as the foveal bulge. At the same time, contrary to the initial hypothesis, biological age assessed by the PhenoAge algorithm did not demonstrate a significant advantage over chronological age in predicting these changes.

With respect to age-related changes in retinal thickness, previous studies have reported heterogeneous findings. Some authors have described a significant age-associated thinning of the total retina and nerve fiber layer [

15], whereas others found no relationship between age and macular thickness in healthy eyes [

16]. Regional analyses have further suggested that age-related thinning predominantly affects parafoveal and peripheral regions, while foveal thickness remains relatively preserved [

17].

In another study, analysis was intentionally restricted to the foveal pit region, and no significant age-related dependence was detected for central foveal thickness or other geometric parameters [

3,

18]. These findings support the notion that the core architecture of the foveal pit demonstrates substantial structural resilience to physiological aging, in contrast to more peripheral retinal regions that may exhibit greater age sensitivity.

The analysis data showed that foveal thickness, foveal pit depth and diameter, and the steepness of its slope remain unchanged throughout adult life (from 22 to 89 years). This stability in a healthy cohort supports the concept that the basic architecture of the fovea, formed during development, is a highly resilient structure, minimally susceptible to involutional changes. It can be assumed that such stability serves as a mechanism for maintaining the optical quality of the central pit as the "visual window," ensuring a constant retinal image at the photoreceptor level even against the backdrop of age-related changes occurring in other layers. Thus, the revealed robustness of the main geometric parameters allows them to be considered reliable, age-independent references in clinical practice.

The most significant result of the work was the clear, monotonic decline in the prevalence of the foveal bulge with age, confirmed by both age models. The 4-5% reduction in the odds of its presence per year (OR ~0.95-0.96) translates into an almost twofold drop in prevalence between the youngest (<45 years) and oldest (>60 years) groups. Studies in healthy adults have shown that the prevalence and height of the foveal bulge decrease with age, consistent with age-related changes in outer retinal structure [

19]. Importantly, our findings establish the first normative age-related trajectory for foveal bulge prevalence in a healthy population, supporting its use as an age-adjusted qualitative biomarker of outer retinal aging in clinical OCT interpretation.

Since the foveal bulge morphologically represents a convexity formed by the cone outer segments and the ellipsoid zone, its disappearance likely reflects complex remodeling processes in the outer retinal layers. These processes may include: shortening and altered orientation of cone outer segments, decreased cone density, atrophic changes in the perifoveal RPE zone, and subtle shifts in the contact zone between photoreceptors and the RPE [

20]. Given its anatomical correspondence to the cone outer segment and ellipsoid zone complex, the foveal bulge likely reflects subtle remodeling of photoreceptor integrity rather than gross retinal architecture. This interpretation is consistent with previous reports linking the presence of the bulge to superior visual outcomes in various macular disorders [

5,

8,

21].

Although biological age is conceptually designed to capture cumulative physiological stress, several factors may explain why PhenoAge did not outperform chronological age in predicting foveal structural parameters in this healthy cohort.

First, PhenoAge incorporates chronological age as an integral component of its algorithm, which inherently limits its independence as a predictor. In populations with low systemic disease burden, such as the present cohort of carefully screened healthy volunteers, biological and chronological aging processes may remain highly synchronized.

Second, the neurosensory retina, particularly the fovea, may follow a tightly regulated aging trajectory that is less susceptible to systemic metabolic variation in the absence of overt pathology [

22]. This interpretation is supported by the near-identical age-related trajectories observed for both age metrics and the extremely high correlation between model predictions.

Finally, biological age biomarkers such as PhenoAge may demonstrate greater discriminative power in populations with accelerated or heterogeneous aging, including individuals with metabolic, cardiovascular, or neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, the lack of added predictive value of PhenoAge in the present study should not be interpreted as a limitation of the concept of biological aging itself, but rather as evidence of structural resilience and temporal synchrony of foveolar aging in healthy adults.

Our findings stand in contrast to recent studies on “retinal age” derived from fundus photography. While deep learning models can predict systemic biological age from retinal vasculature and optic disc features, our study suggests that the foveal microstructure itself is structurally resilient and does not mirror these systemic shifts [

23,

24,

25]. This dissociates the "neurosensory" aging of the fovea from the "vascular" aging captured by retinal clocks.

The study limitations are associated with several factors. The cross-sectional design allows for the identification of age-related associations but does not permit the establishment of true longitudinal “dynamics” or causal relationships between systemic biological aging and retinal remodeling. The small size of the oldest subgroup (>75 years), especially in the PhenoAge analysis, makes estimates for this age range less precise. The homogeneity of the sample (healthy volunteers) limits the generalizability of the results to populations with comorbid conditions, where the discrepancy between biological and chronological age may be significant.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that, in healthy adults, the basic geometric parameters of the foveal pit remain structurally stable throughout adulthood, supporting their reliability as age-independent anatomical references. In contrast, the foveal bulge emerged as a highly sensitive and clinically relevant feature, whose prevalence progressively declines with age, likely reflecting subtle remodeling of the photoreceptor and retinal pigment epithelial complex. Importantly, biological age estimated by PhenoAge did not show greater predictive power than chronological age for any of the analyzed OCT parameters, indicating a high degree of synchrony between foveal structural aging and calendar time under physiological conditions. Clinically, these findings highlight the importance of accounting for patient age when interpreting the presence or absence of the foveal bulge to distinguish normal aging from early pathological changes. Future studies should focus on longitudinal validation of these trajectories, functional correlates of foveal bulge loss, and their behavior in populations with accelerated biological aging or systemic disease, where discrepancies between biological and chronological age may have greater prognostic relevance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.K., Y.Y., L.V.M., I.D.S.; methodology, Kh.Kh.A., A.A.M.; software, L.V.M.; validation, Kh.Kh.A. and A.A.M.; formal analysis, A.S.K.; investigation, A.S.K., L.V.M., Kh.Kh.A., A.A.M.; resources, Y.Y., I.D.S.; data curation, Kh.Kh.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.K.; writing—review and editing, L.V.M.; visualization, Kh.Kh.A.; supervision, I.D.S.; project administration, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, I.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Ethics Committee (protocol No. 59 from 13 September 2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions and ethical considerations regarding participant data.

Acknowledgments

not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OCT |

Optical coherence tomography |

| EZ |

Ellipsoid zone |

| CFT |

Central foveal thickness |

| ILM |

Internal limiting membrane |

| GAM |

Generalized additive models |

| AIC |

Akaike information criterion |

References

- Tick, S.; Rossant, F.; Ghrbel, I.; Gaudric, A.; Sahel, J.A.; Chaumet-Riffaud, P.; et al. Foveal shape and structure in a normal population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 5105–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringmann, A.; Syrbe, S.; Görner, K.; Kacza, J.; Francke, M.; Wiedemann, P.; et al. The primate fovea: Structure, function and development. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 66, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.T.; Ma, I.H.; Hsieh, Y.T. Gender- and age-related differences in foveal pit morphology. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, S37–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; Simms, A.G.; Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Gameiro, G.R.; et al. Age-related focal thinning of the ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer in a healthy population. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 3034–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Ueda, T.; Okamoto, M.; Ogata, N. Presence of foveal bulge in optical coherence tomographic images in eyes with macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 390–396.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haddad, C.E.; El Mollayess, G.M.; Mahfoud, Z.R.; Jaafar, D.F.; Bashshur, Z.F. Macular ultrastructural features in amblyopia using high-definition optical coherence tomography. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 97, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.G.; Kumar, A.; Mohammad, S.; Proudlock, F.A.; Engle, E.C.; Andrews, C.; et al. Structural grading of foveal hypoplasia using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography as a predictor of visual acuity. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Ueda, T.; Okamoto, M.; Ogata, N. Relationship between presence of foveal bulge in optical coherence tomographic images and visual acuity after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Retina 2014, 34, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Scholl, H.P.; Birch, D.G.; Iwata, T.; Miller, N.R.; Goldberg, M.F. Characterizing the phenotype and genotype of a family with occult macular dystrophy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2012, 130, 1554–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, R.; Gui, P.; et al. A cross population study of retinal aging biomarkers with longitudinal pre-training and label distribution learning. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimbly, M.J.; Koopowitz, S.M.; Chen, R.; et al. Estimating biological age from retinal imaging: A scoping review. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024, 9, e001794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, N.T.; Fain, G.L.; Sampath, A.P. Elevated energy requirement of cone photoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 19599–19603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubis, A.M.; McAllister, J.T.; Carroll, J. Reconstructing foveal pit morphology from optical coherence tomography imaging. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 93, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamouti, B.; Funk, J. Retinal thickness decreases with age: An OCT study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhi, M.; Aziz, S.; Muhammad, K.; Adhi, M.I. Macular thickness by age and gender in healthy eyes using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qu, Y. Assessment of the effect of age on macular layer thickness in a healthy Chinese cohort using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Bascones, D.; et al. Spatial characterization of age and sex effects on macular layer thicknesses and foveal pit morphology. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0278925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, K.; Roy, R.; Sharma, P.; et al. Age-related changes in the foveal bulge in healthy eyes. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 24, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domdei, N.; Ameln, J.; Gutnikov, A.; et al. Cone density is correlated to outer segment length and retinal thickness in the human foveola. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, S.A.; Ali, M.; Sharma, A.; et al. The impact of the foveal bulge on visual acuity in resolved diabetic macular edema and retinal vein occlusions. Cureus 2024, 16, e75543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesmith, B.L.; Gupta, A.; Strange, T.; Schaal, Y.; Schaal, S. Mathematical analysis of the normal anatomy of the aging fovea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 5962–5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusinovici, S.; Rim, T.H.; Yu, M.; et al. Retinal photograph-based deep learning predicts biological age and stratifies morbidity and mortality risk. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadi, S.; Wilson, K.A.; Babenko, B.; et al. Longitudinal fundus imaging and its genome-wide association analysis provide evidence for a human retinal aging clock. eLife 2023, 12, e82364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusinovici, S.; Rim, T.H.; Li, H.; et al. Application of a deep-learning marker for morbidity and mortality prediction derived from retinal photographs. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, e700–e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).