Submitted:

17 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

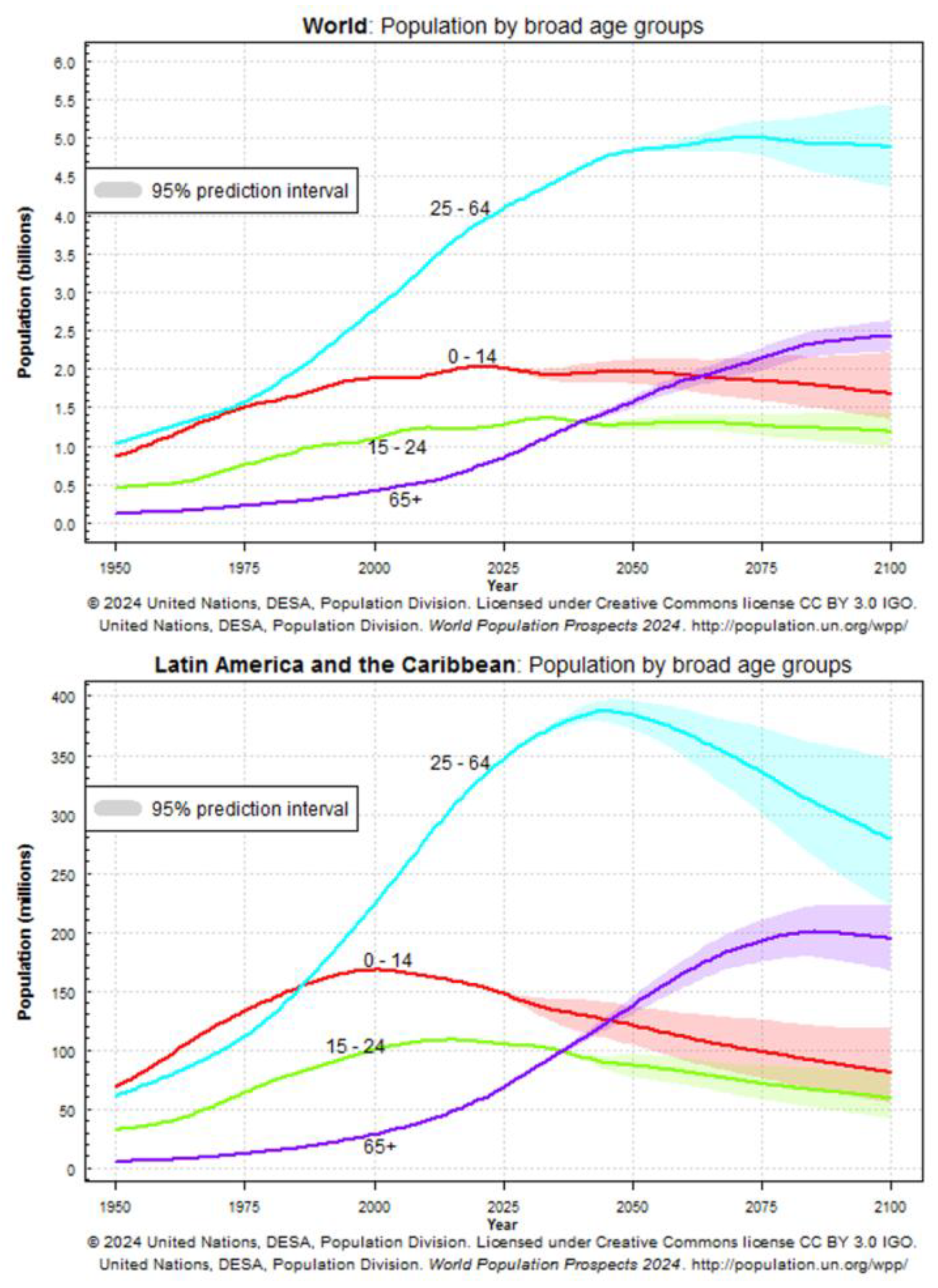

Introduction

Aging and the Immune System

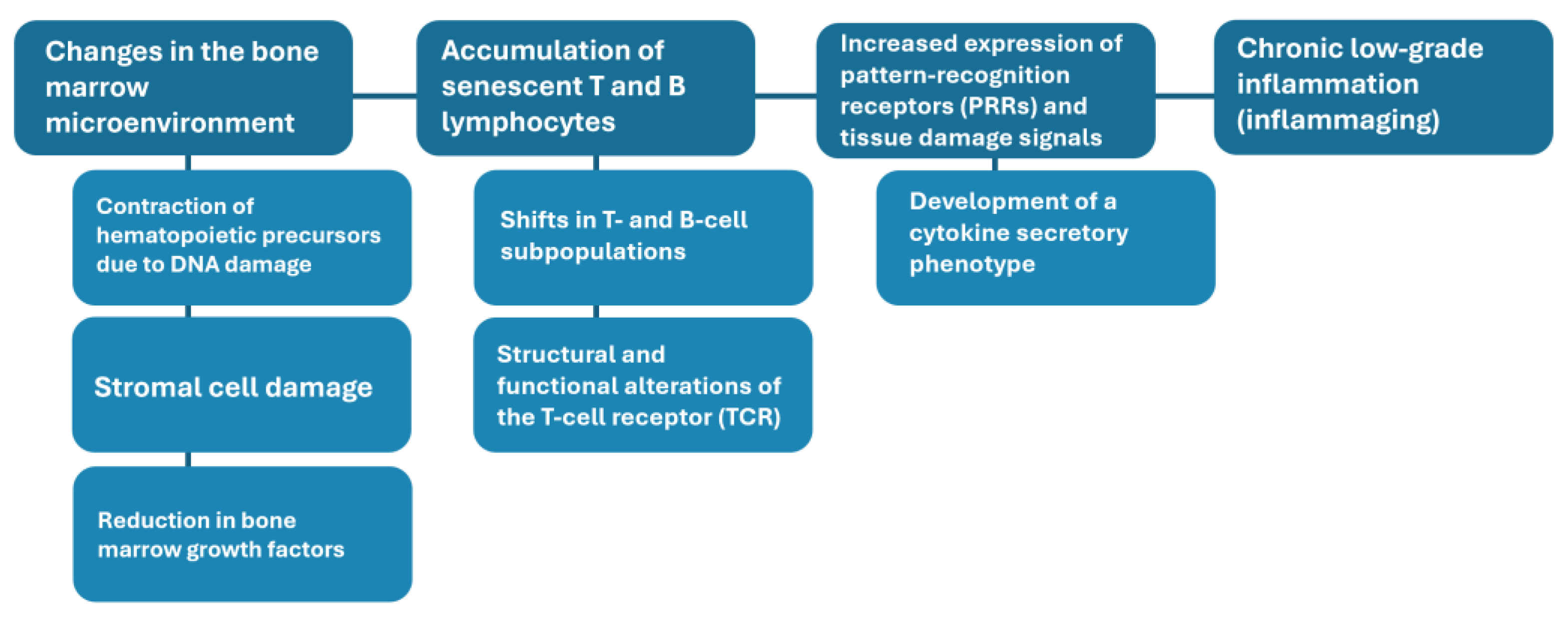

Biological Foundations of Immunosenescence

Remodeling of Innate and Adaptive Immunity

Inflammaging and Its Clinical Consequences

Heterogeneity of Immune Aging

Public Health Implications

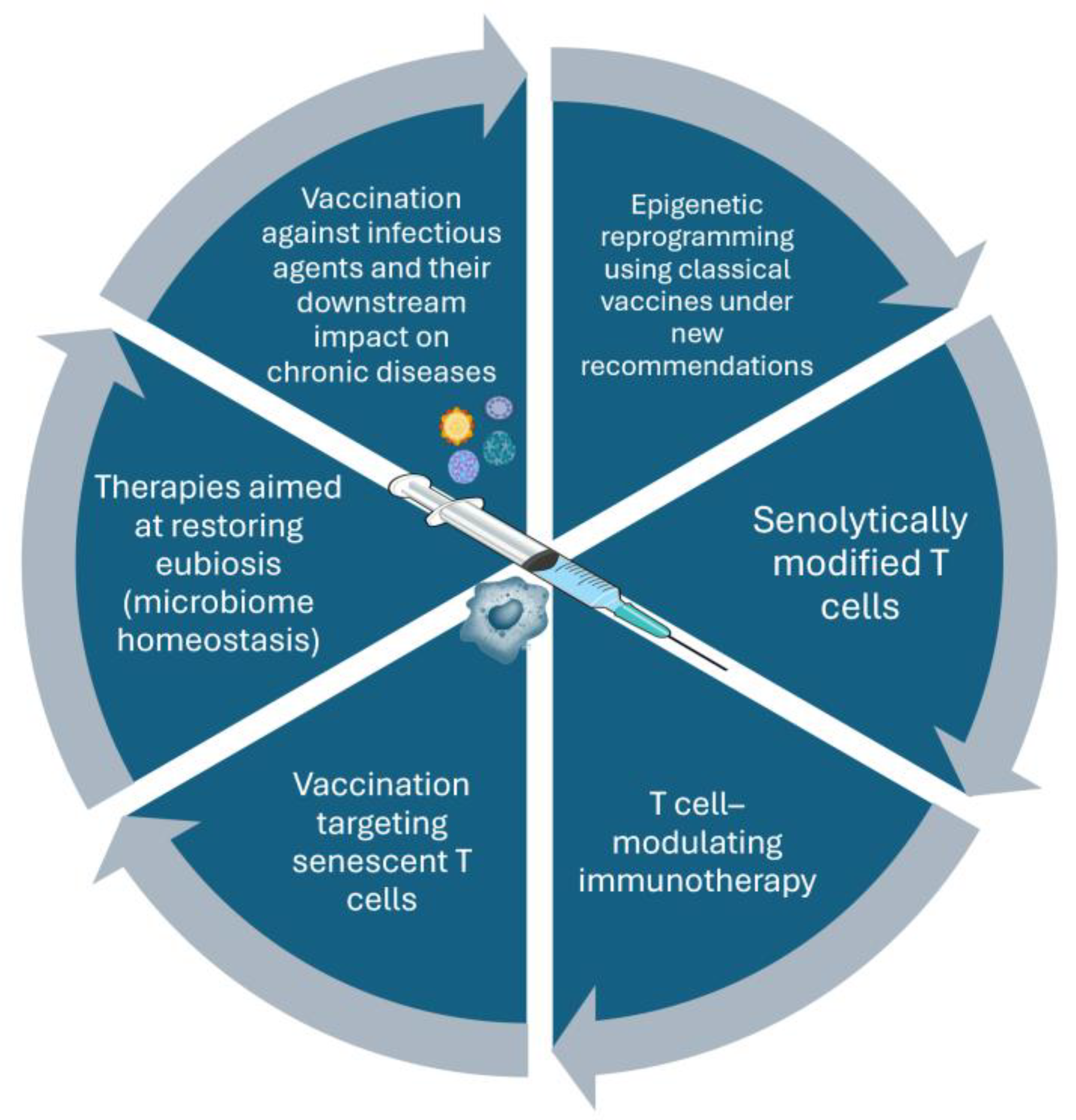

Vaccine-mediated Immunomodulation

From Simple Protection to Systemic Effects

Vaccines and the Inflammatory Burden

Immunobiography and Heterogeneity of Responses

Trained Immunity and Epigenetic Reprogramming

Innovative Approaches to Enhance Vaccine Responses

- Adjuvants: Modern adjuvants such as MF59 and AS01 enhance antigen presentation and promote stronger T and B cell responses. Their inclusion in vaccines for older adults has demonstrated improved immunogenicity.

- Higher antigen doses: High-dose influenza vaccines provide greater antigen exposure, compensating for the reduced responsiveness of aging immune systems and improving clinical protection.

- Conjugate vaccines: By linking polysaccharides to protein carriers, conjugate vaccines recruit T cell help and generate stronger, longer-lasting antibody responses.

- Pattern recognition receptor agonists: Incorporating molecular motifs that mimic microbial signals enhances the activation of dendritic cells and other antigen-presenting cells.

- Epigenetic modulation: Experimental approaches aim to deliberately induce beneficial epigenetic changes, effectively “resetting” immune cells to a more functional state.

Lifelong Immunomodulation

Future Directions

Conceptual Implications

Limitations

Conclusions

| Mechanism | Potential application | Proposed mechanism of action | Expected outcome | Unresolved issues/gaps |

| Vaccine-induced epigenetic modifications via trained immunity | Novel immunomodulatory indications for BCG and measles vaccines, including enhancement of responses to unrelated pathogens and vaccines | Induction of trained immunity through pattern-recognition receptor signaling pathways (e.g., NOD2), histone H3 modification, and metabolic reprogramming of hematopoietic stem cells toward progeny with a protective immunophenotype | Modulation of metabolic pathways with increased production of trained myeloid cells and monocytes; positive heterologous effects on overall mortality, cognitive development, and cancer incidence | Additional clinical studies are required to support recommendations beyond pediatric populations |

| Implementation of novel correlates of protection | Improved assessment of immunogenicity of inactivated influenza vaccines in older adults | Measurement of IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios, granzyme B levels, and functional antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assays | Improved correlation between immune markers and vaccine effectiveness in older adults | Challenges in biomarker standardization and implementation across laboratories |

| Incorporation of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) as PRR ligands in vaccine formulations | Use of advanced adjuvants to enhance cellular immune responses | Use of adjuvants such as monophosphoryl lipid A and synthetic glucopyranosyl lipid derivatives to promote cross-presentation and cytotoxic T-cell activation | Induction of strong cellular effector immune responses | Further research is required before routine clinical use |

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gianfredi, V.; Nucci, D.; Pennisi, F.; Maggi, S.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P. Aging, longevity, and healthy aging: the public health approach. Aging Clin Exp Res 2025, 37, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geard, N.; Glass, K.; McCaw, J.M.; McBryde, E.S.; Korb, K.B.; Keeling, M.J.; McVernon, J. The effects of demographic change on disease transmission and vaccine impact in a household-structured population. Epidemics 2015, 13, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; Gayo, E.M.; Estay, S.A.; Gurruchaga, A.; Robinson, E.; Freeman, J.; Latorre, C.; Bird, D. Positive feedbacks in deep-time transitions of human populations. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2024, 379, 20220256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, S. Perspectives on Aging and Quality of Life. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, S.; Kerr, C.; Oktay, K.; Racowsky, C. The Implications of Reproductive Aging for the Health, Vitality, and Economic Welfare of Human Societies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 3821–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya-Ito, R.; Iwarsson, S.; Slaug, B. Environmental Challenges in the Home for Ageing Societies: a Comparison of Sweden and Japan. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2019, 34, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; MacGregor, H.; Scoones, I.; Wilkinson, A. Post-pandemic transformations: How and why COVID-19 requires us to rethink development. World Dev 2021, 138, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risquez, A.; Echezuria, L.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Epidemiological transition in Venezuela: relationships between infectious diarrheas, ischemic heart diseases and motor vehicles accidents mortalities and the Human Development Index (HDI) in Venezuela, 2005-2007. J Infect Public Health 2010, 3, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, T.; Rayner, G. Beyond the Golden Era of public health: charting a path from sanitarianism to ecological public health. Public Health 2015, 129, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheung, K.S.L.; Yip, P.S.F. Are We Living Longer and Healthier? J Aging Health 2020, 32, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyasi, R.M.; Phillips, D.R. Aging and the Rising Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa and other Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Call for Holistic Action. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Peña, J.I.; Fernández-Ramos, M.C.; Garayeta, A. Cost-Free LTC Model Incorporated into Private Pension Schemes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. The longevity society. Lancet Healthy Longev 2021, 2, e820–e827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Y.; Murayama, H.; Hasebe, M.; Yamaguchi, J.; Fujiwara, Y. The impact of intergenerational programs on social capital in Japan: a randomized population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bárrios, M.J.; Fernandes, A.A.; Fonseca, A.M. Identifying Priorities for Aging Policies in Two Portuguese Communities. J Aging Soc Policy 2018, 30, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global age-sex-specific all-cause mortality and life expectancy estimates for 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1950-2023: a demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1731–1810. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Castañeda-Hernández, D.M. Relationships between morbidity and mortality from tuberculosis and the human development index (HDI) in Venezuela, 1998-2008. Int J Infect Dis 2012, 16, e704–e705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Herrera, D.; González-Ocampo, D.; Restrepo-Montoya, V.; Gómez-Guevara, J.E.; Alvear-Villacorte, N.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J. Relationship between malaria epidemiology and the human development index in Colombia and Latin America. Infez Med 2018, 26, 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A.; Weinberger, B. Vaccines to Prevent Infectious Diseases in the Older Population: Immunological Challenges and Future Perspectives. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B. Vaccination of older adults: Influenza, pneumococcal disease, herpes zoster, COVID-19 and beyond. Immun Ageing 2021, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Maciel, J.; Del Valle, E.; Lutz, C. Health Predictions in Latin America. J Insur Med 2024, 51, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.V.; Ghosh, R.; Coll, K.; Chun, C.; Yousefzadeh, M.J. The 3 I's of immunity and aging: immunosenescence, inflammaging, and immune resilience. Front Aging 2024, 5, 1490302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Guo, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Q.; Luo, P.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X. Immunosenescence: molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Z.; Huang, S.T.; Wen, Y.W.; Chen, L.K.; Hsiao, F.Y. Combined Effects of Frailty and Polypharmacy on Health Outcomes in Older Adults: Frailty Outweighs Polypharmacy. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, e607–e606-606.e618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debbag, R.; Gallo, J.; Ávila-Agüero, M.L.; Beltran, C.; Brea-Del Castillo, J.; Puentes, A.; Enrique, S. Rebuilding vaccine confidence in Latin America and the Caribbean: strategies for the post-pandemic era. Expert Rev Vaccines 2025, 24, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, P.P.; Data, K.; Strzelec, B.; Farzaneh, M.; Anbiyaiee, A.; Zaheer, U.; Uddin, S.; Sheykhi-Sabzehpoush, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Zabel, M.; et al. Human Aging and Age-Related Diseases: From Underlying Mechanisms to Pro-Longevity Interventions. Aging Dis 2024, 16, 1853–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Pecetta, S.; Scorza, F.B.; Carfi, A.; Carleton, B.; Cipriano, M.; Edwards, K.; Gasperini, G.; Malley, R.; Nandi, A.; et al. Vaccination for healthy aging. Sci Transl Med 2024, 16, eadm9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addario, A.; Célarier, T.; Bongue, B.; Barth, N.; Gavazzi, G.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Impact of influenza, herpes zoster, and pneumococcal vaccinations on the incidence of cardiovascular events in subjects aged over 65 years: a systematic review. Geroscience 2023, 45, 3419–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict Kpozehouen, E.; Raina Macintyre, C.; Tan, T.C. Coverage of influenza, pneumococcal and zoster vaccination and determinants of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination among adults with cardiovascular diseases in community. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soegiarto, G.; Purnomosari, D. Challenges in the Vaccination of the Elderly and Strategies for Improvement. Pathophysiology 2023, 30, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.P.; Goldberg, J. Education, Healthy Ageing and Vaccine Literacy. J Nutr Health Aging 2021, 25, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.N.; Trivedi, N.; Baur, C. Re-Prioritizing Digital Health and Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030 to Affect Health Equity. Health Commun 2021, 36, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stancu, A.; Khan, A.; Barratt, J. Driving the life course approach to vaccination through the lens of key global agendas. Front Aging 2023, 4, 1200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindyapina, A.V.; Zenin, A.A.; Tarkhov, A.E.; Santesmasses, D.; Fedichev, P.O.; Gladyshev, V.N. Germline burden of rare damaging variants negatively affects human healthspan and lifespan. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zábó, V.; Lehoczki, A.; Buda, A.; Varga, P.; Fekete, M.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Moizs, M.; Giovannetti, G.; Loscalzo, Y.; Giannini, M.; et al. The role of burnout prevention in promoting healthy aging: frameworks for the Semmelweis Study and Semmelweis-EUniWell Workplace Health Promotion Program. Geroscience 2025, 47, 6377–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S.N.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. Immunosenescence and human vaccine immune responses. Immun Ageing 2019, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.J.; Rapp, S.; Klenerman, P.; Simon, A.K. Understanding and improving vaccine efficacy in older adults. Nat Aging 2025, 5, 1455–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mao, Z.; Tang, W.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; You, Y. Immunosenescence in aging and neurodegenerative diseases: evidence, key hallmarks, and therapeutic implications. Transl Neurodegener 2025, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.; Lee, X.E.; Ng, P.Y.; Lee, Y.; Dreesen, O. The role of cellular senescence in skin aging and age-related skin pathologies. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1297637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, X.; Wang, F.; Geng, X. Telomere and its role in the aging pathways: telomere shortening, cell senescence and mitochondria dysfunction. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanesan, S.; Chang, E.; Howell, M.D.; Rajadas, J. Amyloid protein aggregates: new clients for mitochondrial energy production in the brain? Febs j 2020, 287, 3386–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, L.; Hajdu, K.L.; Ho, P.C. Meta-epigenetic shifts in T cell aging and aging-related dysfunction. J Biomed Sci 2025, 32, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.; Law, S.F.; Pignolo, R.J. Changing landscape of hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells and their interactions during aging and in age-related skeletal pathologies. Mech Ageing Dev 2025, 225, 112059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, H.R.; Chtanova, T. The lymph node neutrophil. Semin Immunol 2016, 28, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazzi, L.; Weinberger, B. T cells, aging and senescence. Exp Gerontol 2020, 134, 110887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banić, M.; Pleško, S.; Urek, M.; Babić, Ž.; Kardum, D. Immunosenescence, Inflammaging and Resilience: An Evolutionary Perspective of Adaptation in the Light of COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatr Danub 2021, 33, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. The role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) in the inflammaging process. Ageing Res Rev 2018, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ruiz, Y.G.; Lopatynsky-Reyes, E.Z.; Ulloa-Gutierrez, R.; Avila-Agüero, M.L.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Basa, J.E.; Nikiema, F.W.; Chacon-Cruz, E. 100-Day Mission for Future Pandemic Vaccines, Viewed Through the Lens of Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosio, B.; Rossi, P.D.; Ferri, E.; Consorti, E.; Ciccone, S.; Lucchi, T.A.; Montano, N. The inflammatory profiling in a cohort of older patients suffering from cognitive decline and dementia. Exp Gerontol 2025, 201, 112692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezuș, E.; Cardoneanu, A.; Burlui, A.; Luca, A.; Codreanu, C.; Tamba, B.I.; Stanciu, G.D.; Dima, N.; Bădescu, C.; Rezuș, C. The Link Between Inflammaging and Degenerative Joint Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, S.; Caspi, A.; Barnes, J.C.; Brennan, G.; Poulton, R.; Purdy, S.C.; Ramrakha, S.; Tanksley, P.T.; Thorne, P.R.; Wilson, G.; et al. Life-Course Persistent Antisocial Behavior and Accelerated Biological Aging in a Longitudinal Birth Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Khelghati, N.; Alemi, F.; Bazdar, M.; Asemi, Z.; Majidinia, M.; Sadeghpoor, A.; Mahmoodpoor, A.; Jadidi-Niaragh, F.; Targhazeh, N.; et al. Stabilization of telomere by the antioxidant property of polyphenols: Anti-aging potential. Life Sci 2020, 259, 118341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Conejero, L.; Netea, M.G.; Sancho, D.; Palomares, Ó.; Subiza, J.L. Trained Immunity-Based Vaccines: A New Paradigm for the Development of Broad-Spectrum Anti-infectious Formulations. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, M. Immune Resilience: Rewriting the Rules of Healthy Aging. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka-Tojo, M.; Tojo, T. Herpes Zoster and Cardiovascular Disease: Exploring Associations and Preventive Measures through Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidecker, B.; Libby, P.; Vassiliou, V.S.; Roubille, F.; Vardeny, O.; Hassager, C.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Cooper, L.T.; Schoenrath, F.; et al. Vaccination as a new form of cardiovascular prevention: a European Society of Cardiology clinical consensus statement. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 3518–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomirchy, M.; Bommer, C.; Pradella, F.; Michalik, F.; Peters, R.; Geldsetzer, P. Herpes Zoster Vaccination and Dementia Occurrence. Jama 2025, 333, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, E.; Ray, I.; Arnold, B.F.; Acharya, N.R. Recombinant zoster vaccine and the risk of dementia. Vaccine 2025, 46, 126673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Deng, J.; Liu, J. The association between herpes zoster vaccination and the decreased risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Alzheimers Dis 2025, 106, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, S.; Fulöp, T.; De Vita, E.; Limongi, F.; Pizzol, D.; Di Gennaro, F.; Veronese, N. Association between vaccinations and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2025, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleve, A.; Motta, F.; Durante, B.; Pandolfo, C.; Selmi, C.; Sica, A. Immunosenescence, Inflammaging, and Frailty: Role of Myeloid Cells in Age-Related Diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2023, 64, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Raza, U.; Song, J.; Lu, J.; Yao, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, S. Systemic aging fuels heart failure: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic avenues. ESC Heart Fail 2025, 12, 1059–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehar-Belaid, D.; Sokolowski, M.; Ravichandran, S.; Banchereau, J.; Chaussabel, D.; Ucar, D. Baseline immune states (BIS) associated with vaccine responsiveness and factors that shape the BIS. Semin Immunol 2023, 70, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassopoulou, C.; Ferous, S.; Medić, S.; Siafakas, N.; Boufidou, F.; Gioula, G.; Tsakris, A. Vaccines for the Elderly and Vaccination Programs in Europe and the United States. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Madsen, J.C.; Netea, M.G.; Duivenvoorden, R. Trained immunity - basic concepts and contributions to immunopathology. Nat Rev Nephrol 2023, 19, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkering, S.; Domínguez-Andrés, J.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Riksen, N.P.; Netea, M.G. Trained Immunity: Reprogramming Innate Immunity in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2021, 39, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, K.; Siddiqui, A.; Nugent, K. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Vaccine and Nonspecific Immunity. Am J Med Sci 2021, 361, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covián, C.; Fernández-Fierro, A.; Retamal-Díaz, A.; Díaz, F.E.; Vasquez, A.E.; Lay, M.K.; Riedel, C.A.; González, P.A.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. BCG-Induced Cross-Protection and Development of Trained Immunity: Implication for Vaccine Design. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, F.Z.; Skwarczynski, M.; Toth, I. Developments in Vaccine Adjuvants. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2412, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B. Adjuvant strategies to improve vaccination of the elderly population. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018, 41, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerarathna, I.N.; Doelakeh, E.S.; Kiwanuka, L.; Kumar, P.; Arora, S. Prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine development: advancements and challenges. Mol Biomed 2024, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gomensoro, E.; Del Giudice, G.; Doherty, T.M. Challenges in adult vaccination. Ann Med 2018, 50, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, M.; Biundo, E.; Chicoye, A.; Devlin, N.; Mark Doherty, T.; Garcia-Ruiz, A.J.; Jaros, P.; Sheikh, S.; Toumi, M.; Wasem, J.; et al. Capturing the value of vaccination within health technology assessment and health economics: Country analysis and priority value concepts. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3999–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polisky, V.; Littmann, M.; Triastcyn, A.; Horn, M.; Georgiou, A.; Widenmaier, R.; Anspach, B.; Tahrat, H.; Kumar, S.; Buser-Doepner, C.; et al. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation and the risk of dementia. Nat Med 2025, 31, 4172–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-Aguero, M.L.; Brea-del Castillo, J.; Falleiros-Arlant, L.H. Vaccines without borders to Latin America. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013, 12, 1239–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phenomenon | Origin of the phenomenon | Related outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Increased serum TNF-alpha, IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-6 | Dysfunction of monocytes and macrophages and overexpression of PRRs | Cognitive dysfunction and deterioration of cardiovascular health |

| Chronic antigenic stimulation derived from pathogens | Chronic antigenic stimulation derived from pathogens. Induction of inflammation driven by pathogen-associated antigenic diversity. | Chronic inflammation and accumulation of visceral fat |

| Dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability | Dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability. Loss of microbiota resilience and impairment of intestinal barrier function. | Chronic inflammation and accumulation of visceral fat |

| Chronic activation of the inflammasome | Chronic activation of the inflammasome. Proteostasis and loss of inflammasome regulation. | Chronic inflammation and accumulation of visceral fat |

| Microbial translocation and an increase in tissue damage molecules | Microbial translocation and an increase in tissue damage molecules. Increased exposure to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. | Cognitive dysfunction and deterioration of cardiovascular health |

| Alteration in liver function, synthesis of inflammatory proteins, and toxicity to the brain, kidney, and muscle | Alteration in liver function, synthesis of inflammatory proteins, and toxicity to the brain, kidney, and muscle. Loss of the capacity to regulate innate inflammation. | Cognitive dysfunction and deterioration of cardiovascular health |

| Senescent cytokine secretion pattern from the adaptive immune system | Modification of T and B cell subpopulations with structural and functional alterations of the TCR | Loss of vaccine responsiveness, vulnerability to infection, and increased risk of cancer and autoimmunity |

| Strategy or platform | Vaccine, technique, or component | Expected benefit | Clinical impact | Limitations/areas for improvement |

| mRNA platforms | COVID-19 vaccines | Induction of robust T-cell and B-cell immune responses. | Prevention of severe disease and reduction of infection-related hyperinflammation. | The immune response wanes relatively rapidly, necessitating booster doses. |

| High-dose antigen formulations | Influenza vaccines, live-attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine. | Increased antigen visibility, leading to higher antibody titers. | Improved antibody titers and enhanced pathogen-specific cellular immunity; superior prevention of hospitalization and mortality compared with standard-dose vaccines. | Higher cost and limited antigen availability; waning efficacy over time; dose-dependent association with cardiovascular events reported for influenza vaccines. |

| Protein conjugation of pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides | PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, PCV21 | Enhanced induction of memory B cells and higher antibody concentrations compared with non-conjugated polysaccharide vaccines. | Reduction in hospitalizations and mortality from invasive pneumococcal disease and community-acquired pneumonia. | Not all conjugate vaccines are available for older adults in national immunization programs across all countries. |

| Use of novel adjuvants | MF59, AS01B | Increased local cytokine production at the injection site, improving recruitment and activation of innate immune cells and antigen presentation. | Enhanced humoral and antigen-specific cellular immune responses. | May be associated with increased local reactogenicity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).