1. Introduction

The central cord syndrome (CCS) accounts for approximately 30% [

1] to 70% [

2] of all cases of incomplete tetraplegia in mixed-age cohorts. Particularly in young people, represents about 20% of incomplete spinal cord injuries (SCI), with high-energy trauma being the most common cause [

3]. CCS is typically characterized by disproportionately greater motor impairment in the upper than in the lower extremities, frequently accompanied by deficits in fine motor control, impairments in postural stability and balance, disturbances in somatosensory perception, sphincter dysfunction, and neuropathic symptoms such as paresthesia, burning pain, or diffuse discomfort, depending on lesion extent and severity [

4,

5]. A retrospective study found significant weakness in the distal upper limbs in 36% and in the lower limbs in 41% of the examined cohort. [

6].

Although CCS has been associated with a relatively favorable prognosis, current longitudinal analyses indicate that neurological and functional recovery tends to plateau within the first one to two years post-injury, often leaving persistent distal motor and sensory deficits that significantly influence autonomy, participation, and overall quality of life [

7]. These residual impairments contribute to increased dependency and impose substantial demands on rehabilitative services, thereby emphasizing the need for therapeutic strategies that enhance functional restoration [

8,

9].

In recent years, transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (tSCS) has emerged as a non-invasive neuromodulation approach to augment motor, sensory, and autonomic recovery following SCI [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This technique involves the placement of surface electrodes over the skin to deliver electrical currents that activate large-diameter afferent fibers within the dorsal roots, thereby modulating segmental and suprasegmental spinal circuits [

17,

18]. Multiple investigations have demonstrated that tSCS can enhance spinal excitability, facilitate the re-engagement of dormant or partially preserved pathways, and potentiate voluntary motor output, even in subjects diagnosed with motor-complete or sensory-complete spinal cord injury [

19].

Although case series and case reports have included individuals classified as D according to the American Spinal Cord Injury Impairment scale (AIS), the literature has not clarified whether these studies included subjects with CCS, a distinction that is clinically relevant due to the unique anatomical and functional characteristics of this syndrome. Additionally, interventions combining tSCS with structured physical therapy (PT) programs have demonstrated synergistic effects, particularly when paired with task-oriented upper-limb training [

12,

14,

16] or gait rehabilitation [

10,

13,

15]. Despite the inclusion of AIS-D participants across studies, it remains uncertain whether individuals with CCS have been specifically represented. This knowledge gap reinforces the importance of characterizing injury syndromes and the motor and sensory evolution of both upper and lower limbs, as well as gait progression, in response to combined tSCS and rehabilitation protocols, critical outcomes addressed in the present report.

2. Materials and Methods

This case report describes a 20-year-old male diagnosed with CCS at the C7 level following a motor vehicle accident in February 2024. As a result of the injury, a cervical interbody cage was placed, and a predominant distal motor impairment in both hands and feet resulted. At hospital discharge, the subject was classified as AIS-D. Post-discharge, the patient underwent therapy at a private rehabilitation facility focused on gait re-education and training of both fine and gross grasp functions. The participant reported no use of medication for spasticity, pain, sleep disturbances, or other conditions during this period. At this stage of recovery, the individual required the use of a cane for ambulation. Twelve months after the SCI, the subject was enrolled in the study “Effect of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation and Functional Rehabilitation on Motor Control in Individuals with Paraplegia due to Spinal Cord Injury,” approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Anáhuac México (approval number 202307; approval date: August 23, 2023). After providing informed consent, the participant initiated a 12-week intervention consisting of two sessions per week, combining tSCS with PT (tSCS+PT). Given that the participant identified improvement in gait as a priority due to mobility-related needs, the placement of the tSCS electrodes at the lumbar enlargement was selected in order to promote motor activation of the lower limbs [

20,

21]. The tSCS was delivered using two 2.5-cm round electrodes placed at the T11-12 and T12–L1 levels (cathodes) and 4 × 8 cm rectangular electrodes placed over the iliac crests (anodes).

Stimulation parameters included a biphasic current with a pulse width of 280 μs per phase and a frequency of 30 Hz, delivered via a DS8R constant-current stimulator (Digitimer™) controlled through LabChart software (AdInstruments™). The stimulation intensity was increased in steps of 0.5 mA from 0 mA at 0.2 Hz and recorded in lower limb muscles bilaterally, including rectus femoris (RF), hamstrings (HM), tibialis anterior (TA), and lateral gastrocnemius (LG). The stimulus intensity that produced Spinal Cord Motor Evoked Potentials (SCMEPs) in any muscle was subtracted by 10% and used as the reference tSCS current for the rest of the protocol (subthreshold intensity). The average applied current was 40 mA. In case of abdominal contractions or discomfort for the participant, the current was decreased. Impedance was monitored during sessions and kept > 2 kHz.

Outcome measures were collected at baseline and at the end of the 12-week intervention. Assessments included the following scales and tests: AIS, Penn, and Spasm Frequency Scale (PSFS), Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS), and handgrip strength (J00105 Hand Dynamometer Lafayette Instrument™). Fine-motor performance was evaluated with the 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT) and the Box and Block Test (BBT). Gait assessments included the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) and the 3-Meter Walk Test (3MWT). Surface Electromyography (sEMG) recordings were digitized at 2 kHz (bandpass 20-500 Hz, PowerLab AdInstruments™) and stored for offline analysis. The same muscles used for the SCMEPs procedure were monitored during treadmill stepping at 3.2 km/h. sEMG analysis included the root-mean-square (RMS) and area under the curve (AUC). For the RMS analysis, the gait episode was segmented into cycles using the RF as the reference muscle, and the step duration was obtained. The RMS was calculated during steeping for each burst of each muscle, and the mean and standard deviation values were calculated. A total of 11 cycles were analyzed at baseline and at 12 weeks. The AUC was obtained from the total duration of the gait trial at both time points, yielding one value per muscle. All analyses were performed in MATLAB R2023b using custom-made scripts.

3. Results

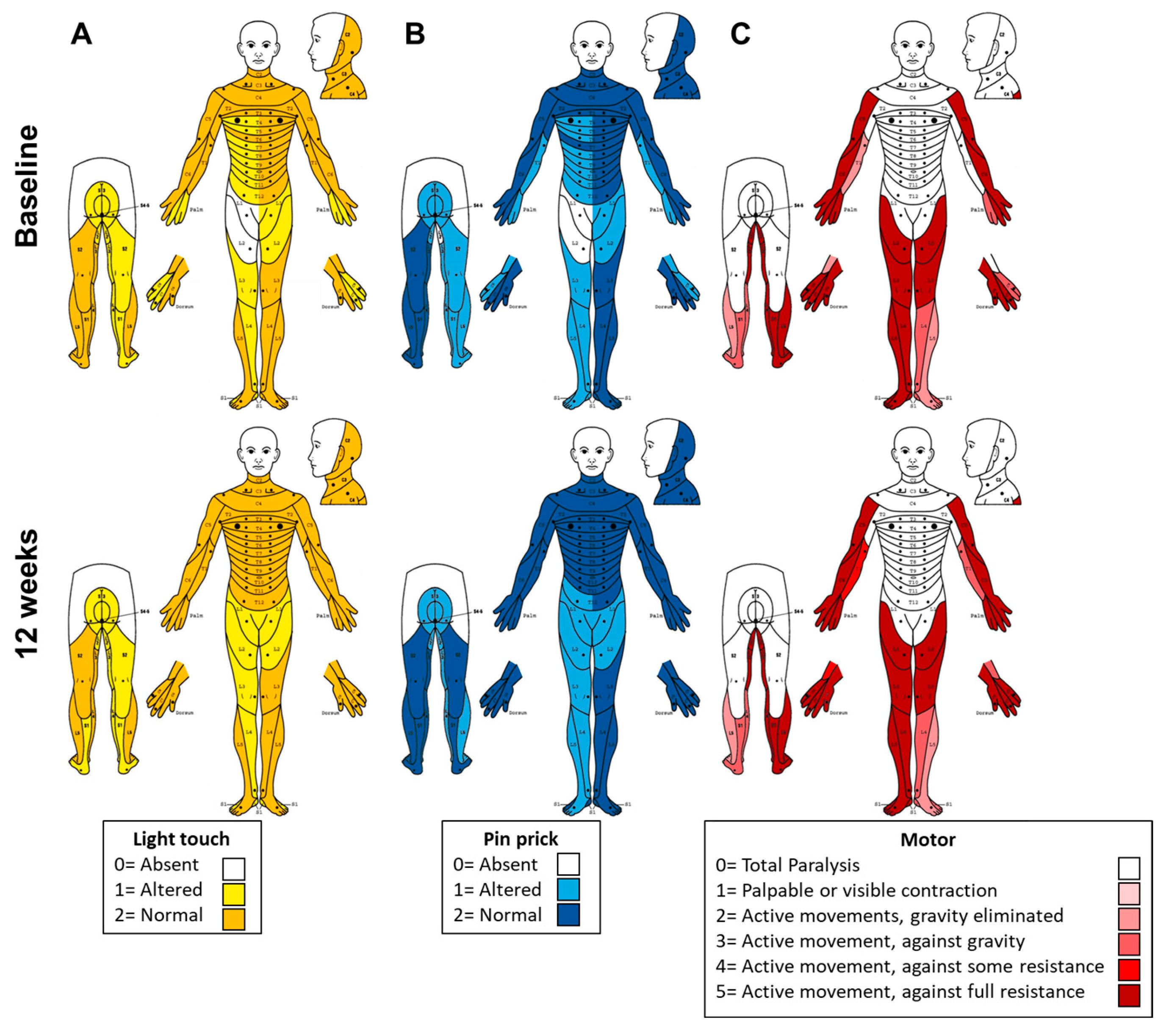

Following 12 weeks of combined tSCS+PT, several clinically relevant changes were observed when compared with baseline assessments. The AIS-ASIA upper extremity motor score (UEMS) improved from 40 to 47 pts, while light touch sensation increased from 86 to 100 pts, and pinprick sensation from 85 to 98 pts. The lower extremity motor score (LEMS) remained unchanged at 43 pts. These findings are summarized in

Figure 1.

Regarding the PSFS, spasm frequency decreased from 4 (spontaneous spasms occurring more than 10 times per hour) to 1 (spasms induced only by tactile stimulation). Severity, interference with function, and the presence of painful spasms remained at 0 at both time points. Clonus persisted at a score of 2 (sustained), and the plantar stimulation response remained at 1 (slight movement/extensor response). Deep tendon reflexes decreased from 2 (average/normal) to 1 (slightly decreased). These findings are detailed in

Table 1. Spasticity was present only in the hands, being the left hand more affected. According to the MAS, the following improvements were observed: in the left hand, finger extension decreased from 1 to 0; thumb flexion decreased from 4 to 1. In the right hand, finger flexion, and finger extension decreased from 1 to 0. The total MAS sum score for each hand is reported in

Table 1.

The upper extremity motor function showed meaningful changes. In the BBT, performance improved from baseline (left hand: 26 blocks/min; right hand: 30 blocks/43 s) to 12 weeks (left hand: 30 blocks/min; right hand: 30 blocks/40 s). In the 9HPT, completion time improved from baseline (left hand: 2.43 min; right hand: 20 s) to 12 weeks (left hand: 1.28 min; right hand: 17 s). The left hand demonstrated the greatest improvement, reducing completion time by 1 min 15 s. Grip strength increased by 2 kg in the right hand (from 32 kg to 34 kg), with no change in the left hand (8 kg). Upper extremity evaluations are shown in

Table 1.

Gait outcomes also improved. On the 6MWT, the patient increased the distance walked by 70.8 m (baseline: 224.4 m; 12 weeks: 295.2 m). In the 3MWT, the execution time decreased by 1.32 s (baseline: 7.96 s; 12 weeks: 6.64 s). These results are summarized in

Table 1.

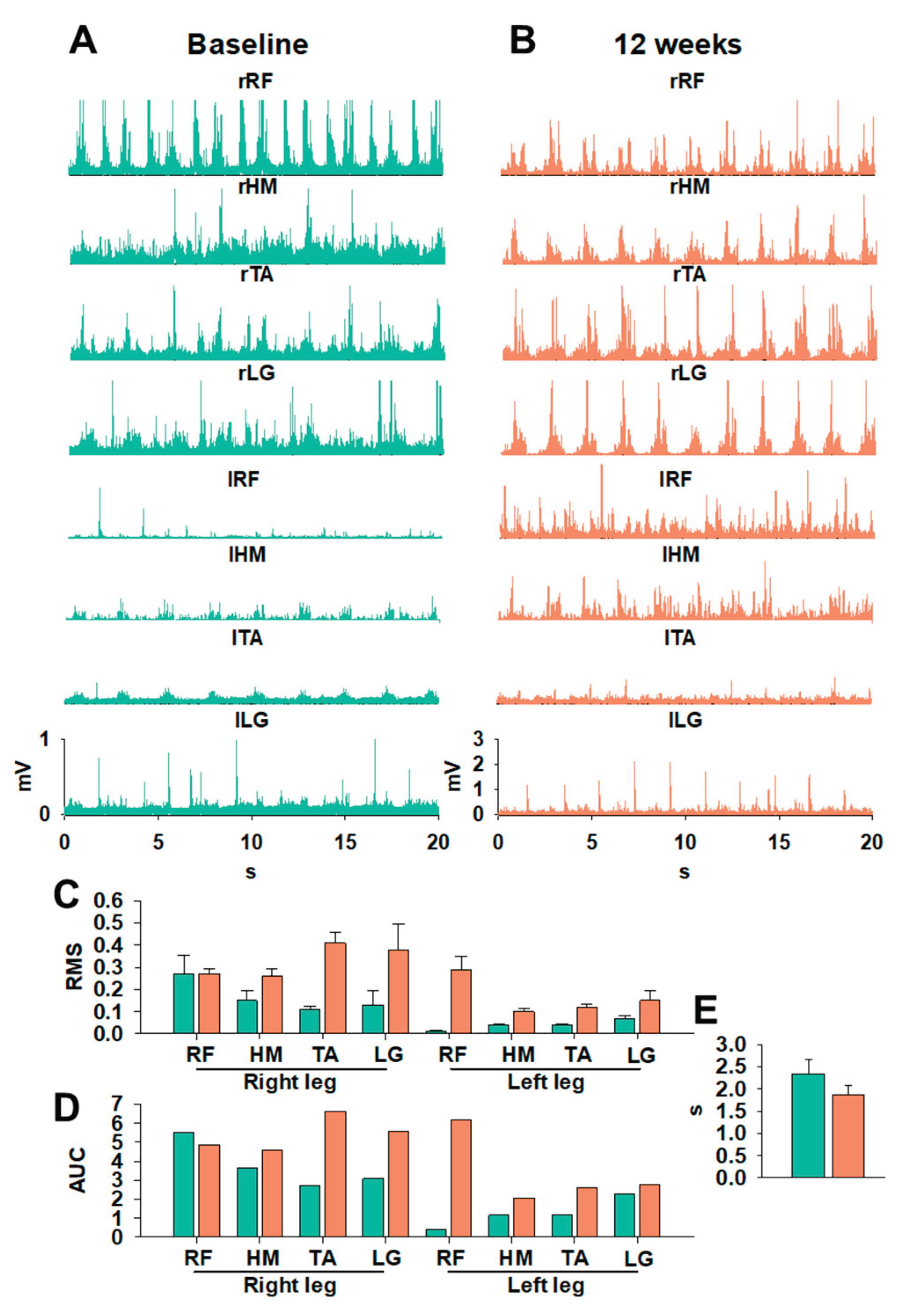

sEMG analysis revealed significant changes in neuromuscular organization during gait at Baseline vs. 12 weeks, as shown in

Figure 2A and 2 B, respectively. Subjectively, prior to the intervention (

Figure 2A), sEMG signals were irregular, with poorly defined peaks and limited differentiation between gait-cycle phase patterns typically associated with CCS involvement and impaired intermuscular coordination [

22]. After tSCS+PT (

Figure 2B), most of the lower-limb muscle groups demonstrated increased amplitude, improved peak definition, and enhanced rhythmic organization. The quantitative analysis of stepping in

Figure 2 C-E shows substantial neuromuscular improvements following 12 weeks of tSCS+PT, as reflected by changes in RMS, AUC, and step cycle duration (

Figure 2 C-E). In the right leg, RMS values increased at 12 weeks across all recorded muscles, including RF, HM, TA, and LG, indicating enhanced motor unit recruitment and a more robust activation profile during stepping. Similar but smaller magnitude changes were observed in the left leg, where RMS amplitudes also increased at 12 weeks, although baseline values were lower, particularly for RF, suggesting initial asymmetry consistent with CCS involvement (

Figure 2C). The AUC analysis further highlights these improvements: all muscles in both legs showed increased AUC values after 12 weeks (

Figure 2D), reflecting not only higher peak activation but also prolonged, more integrated muscle engagement across the stepping cycle. TA and LG showed particularly marked bilateral increases, supporting the interpretation of enhanced distal motor control and suggesting improved contributions to swing-phase dorsiflexion and stance-phase plantarflexion, respectively. In parallel, a decrease in cycle duration from Baseline to 12 weeks was found (

Figure 2E). The findings above are represented in in Supplementary Video 1 (Video S1). The speed of the treadmill was set at 3.2 km/h (≈2 mph). After 12 weeks, gait improvements suggest a more efficient execution of stepping, likely due to improved intermuscular coordination and reduced delays between activation bursts. Collectively, these findings corroborate the sEMG improvements and demonstrate that tSCS+PT facilitated locomotor output, reflected in higher amplitude, temporal integration, and rhythm of neuromuscular activity. Supplementary video 1 shows improvements in after 12 weeks of tSCS+PT compared to Baseline.

4. Discussion

This case report describes a 12-week program combining tSCS+PT applied at thoraco-lumbar level (T11-L1) that produced meaningful improvements in motor, sensory, and functional performance in an individual with CCS. Prior to recruitment, the participant was undergoing conventional PT similar to that used in combination with tSCS in this study, suggesting that the changes reported in this case are attributable to the effects of noninvasive neuromodulation. The placement of the stimulation electrodes (thoracolumbar) was decided jointly with the participant, as his priority was to improve gait in order to facilitate mobility and activities of daily living.

The gains in upper-limb motor strength, light touch and pinprick sensation, hand dexterity, gait endurance, and neuromuscular coordination suggest that tSCS may effectively engage propriospinal and descending pathways that remain partially functional in CCS. These findings are consistent with recent evidence indicating that tSCS enhances spinal excitability and facilitates reactivation of dormant neural circuits in motor-incomplete SCI populations (10,12–16). Improvements in upper-extremity function have been documented, particularly when cervical stimulation facilitates dorsal root afferent recruitment, thereby enhancing segmental and multisegmental integration [

12]. Interestingly, our results support the finding that neuromodulation applied at T11-L1 could impact cervical spinal circuits involved in upper limb function. In this context, the motor and sensory improvements observed in this case study align with previous reports demonstrating that tSCS can modulate ascending inputs and enhance motor and somatosensory processing (13,15,16). Future studies using larger samples should systematically examine whether thoracolumbar stimulation affects upper limb function, particularly in cervical injuries common to different spinal cord injury syndromes [

4]. In this context, thoracolumbar rather than cervical stimulation may be preferable in an initial phase for patients with less severe cervical injuries who present sphincter control dysfunction [

23], as improvements in this domain significantly enhance quality of life, facilitate physical activity, and increase patient confidence.

Mild spasticity was limited to the hands, particularly the left hand (non-dominant), as shown in

Table 1. The reduction in spasm frequency and improvements in spasticity are also consistent with emerging data showing that tSCS enhances both pre- and postsynaptic inhibitory control, modulating hyperexcitable reflex arcs commonly observed in incomplete SCI [

24]. Gait performance notably improved, as reflected by increased distance on the 6MWT and reduced completion time on the 3MWT. These functional gains are supported by sEMG lower limb recordings demonstrating increased amplitude, better-defined muscle activation peaks, and improved rhythmicity during the gait cycle (

Figure 2), a pattern consistent with the reinforcement of central pattern generator activity described in recent locomotor neuromodulation studies with tSCS [

13,

15,

25]. Distal musculature, particularly tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius, showed the most pronounced improvements (

Figure 2C-D), consistent with prior work showing that tSCS can enhance swing-phase dorsiflexion and push-off mechanics [

15]. Overall, the pre-intervention gait cycle was characterized by rhythmic irregularity, poor limb alternation, and non-functional coactivation. Post-intervention recordings suggest more organized cycles, consistent activation peaks, and improved intermuscular coordination (

Figure 2), suggesting functional modulation of spinal locomotor circuits. These neuromuscular changes align with the expected preservation of locomotor pathways and spinal plasticity in CCS. At the end of the intervention, the participant reported subjective improvements in finger control and gait, leading to discontinuation of cane use during ambulation at home.

Collectively, our results indicate functionally relevant reorganization of rhythmic and sequential neuromuscular patterns, suggesting that tSCS may facilitate enhanced modulation of spinal circuits to improve gait expression in individuals with CCS. Importantly, the neuromuscular reorganization observed post-intervention suggests that, even in CCS, where disproportionate upper-limb impairment is typical, spinal networks retain the capacity for adaptive plasticity when appropriately stimulated. This is consistent with previous evidence of functional recovery beyond expected natural plateaus when neuromodulation is integrated with task-specific training (12–15). However, this study has limitations inherent to a single-case design. The absence of a control condition limits causal inference, and the stimulation parameter for this participant may not generalize to all individuals with CCS. Additionally, while no adverse events occurred, recent studies suggest that tSCS may modulate autonomic circuits in variable ways, underscoring the need for careful monitoring beyond sensory and motor function in future work [

11,

26].

Current evidence does not allow a definitive determination of whether individuals with CCS have been included in tSCS studies. The broad eligibility criteria, particularly those requiring incomplete cervical injuries and preserved ambulation, align with clinical features of CCS, suggesting that some participants may have been included unintentionally. This gap is significant, as CCS represents a considerable proportion of cervical spinal cord injuries [

4] and may exhibit distinct responses to neuromodulation due to its disproportionate impact on upper versus lower extremity function.

5. Conclusions

This case report shows that a 12-week program combining tSCS and PT can enhance motor, sensory, and functional performance in the upper and lower limbs in a young adult with CCS. Thoracolumbar electrical stimulation produced meaningful improvements in gait endurance and neuromuscular coordination in the lower limbs, as revealed by sEMG, with more organized, phase-appropriate activation patterns following the intervention. These findings were accompanied by reductions in spasticity and spasm frequency. Importantly, improvements also positively impacted upper-limb strength, fine motor control, and sensory scores. Overall, our results suggest a favorable neuromodulation effect on spinal circuitry and residual descending pathways.

These findings provide preliminary evidence that tSCS may serve as a valuable adjunct to conventional rehabilitation for individuals with mild, incomplete spinal cord injuries, including the CCS population, for whom targeted neuromodulation has not been explicitly reported. The absence of adverse effects further supports the safety and feasibility of integrating tSCS into multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Video S1: Stepping on treadmill.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R., and C.A.R; methodology, F.R, A.I. and C.A.C.; software, C.A.C.; validation, F.R., A.I. and C.A.C; formal analysis, F.R., C.P., A.C., L.V., and C.A.C; investigation, F.R. C.P and C.A.C; resources, A.I. and C.A.C ; data curation, F.R., C.P., A.C. and L.V; writing—original draft preparation, F.R., C.P and C.A.C; writing—review and editing, F.R., C.P., A.I., and C.A.C; visualization, F.R., and C.A.C; supervision, C.A.C; project administration, C.A.C.; funding acquisition, A.I. and C.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Anáhuac México, through the Research Office.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Universidad Anáhuac México (protocol code 202307 and date of approval: August 23, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participant. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the participant and his family. We also thank Alejandra Mendez for his support during physical therapy sessions. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCS |

Central Cord Syndrome |

| tSCS |

Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation |

| SCI |

Spinal Cord Injury |

| PT |

Physical Therapy |

| AIS |

American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale |

| ASIA |

American Spinal Injury Association |

| MAS |

Modified Ashworth Scale |

| PSFS |

Penn and Spasm Frequency Scale |

| 3MWT |

Three-Meter Walk Test |

| 6MWT |

Six-Minute Walk Test |

| 9HPT |

Nine-Hole Peg Test |

| BBT |

Box and Block Test |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| RF |

Rectus Femoris |

| HM |

Hamstrings |

| TA |

Tibialis Anterior |

| LG |

Lateral Gastrocnemius |

| SCMEPs |

Spinal Cord Motor Evoked Potentials |

| sEMG |

Surface Electromyography |

| RMS |

Root Mean Square |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| UEMS |

Upper Extremity Motor Score |

| LEMS |

Lower Extremity Motor Score |

References

- Engel-Haber, E.; Botticello, A.; Snider, B.; Kirshblum, S. Incomplete Spinal Cord Syndromes: Current Incidence and Quantifiable Criteria for Classification. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, AA; Wong, JYH; Pillay, R; Nolan, CP; Ling, JM. Treatment of acute traumatic central cord syndrome: a score-based approach based on the literature. Eur Spine J 2023, 32(5), 1575–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.; Mutch, J.; Parent, S.; Mac-Thiong, J.-M. The changing demographics of traumatic spinal cord injury: An 11-year study of 831 patients. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2013, 38, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel-Haber, E.; Snider, B.; Kirshblum, S. Central cord syndrome definitions, variations and limitations. Spinal Cord 2023, 61, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, MA; Tessler, J; Munakomi, S; Gillis, CC. Central Cord Syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025; Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441932/.

- ROTH, E.; LAWLER, M.; YARKONY, G. TRAUMATIC CENTRAL CORD SYNDROME - CLINICAL-FEATURES AND FUNCTIONAL OUTCOMES. 1990, 71, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, SZ; Marra, A; Jenis, LG; Patel, AA. Current Concepts: Central Cord Syndrome. Clin Spine Surg Spine Publ. 2018, 31(10), 407–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirshblum, S.; Snider, B.; Eren, F.; Guest, J. Characterizing Natural Recovery after Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasetti, G.; Pavese, C.; Maier, D.D.; Weidner, N.; Rupp, R.; Abel, R.; Yorck, B.K.; Jiri, K.; Curt, A.; Molinari, M.; et al. Comparison of outcomes between people with and without central cord syndrome. Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Hofstoetter, U.S.; Hubli, M.; Hassani, R.H.; Rinaldo, C.; Curt, A.; Bolliger, M. Immediate Effects of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation on Motor Function in Chronic, Sensorimotor Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejima, S.; Shackleton, C.; Malik, R.N.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Rempel, L.; Phan, A.-D.; Williams, A.; Nightingale, T.; Ghuman, A.; Elliott, S.; et al. Multi-system benefits of non-invasive spinal cord stimulation following cervical spinal cord injury: a case study. Bioelectron. Med. 2025, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Oh, J.; Bedoy, E.; Chetty, N.; Steele, A.G.; Park, S.J.; Guerrero, J.R.; Faraji, A.H.; Weber, D.; Sayenko, D.G. Transcutaneous stimulation of the cervical spinal cord facilitates motoneuron firing and improves hand-motor function after spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2025, 134, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumru, H.; Ros-Alsina, A.; Alén, L.G.; Vidal, J.; Gerasimenko, Y.; Hernandez, A.; Wrigth, M. Improvement in Motor and Walking Capacity during Multisegmental Transcutaneous Spinal Stimulation in Individuals with Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Bhagat, N.A.; Ramdeo, R.; Ebrahimi, S.; Sharma, P.D.; Griffin, D.G.; Stein, A.; Harkema, S.J.; Bouton, C.E. Targeted transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation promotes persistent recovery of upper limb strength and tactile sensation in spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1210328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharu, N.S.; Wong, A.Y.L.; Zheng, Y.-P. Transcutaneous Electrical Spinal Cord Stimulation Increased Target-Specific Muscle Strength and Locomotion in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanici, F.; Brighton, L.N.; Samejima, S.; Hofstetter, C.P.; Moritz, C.T. Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation Restores Hand and Arm Function After Spinal Cord Injury. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 2021, 29, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladenbauer, J.; Minassian, K.; Hofstoetter, U.S.; Dimitrijevic, M.R.; Rattay, F. Stimulation of the Human Lumbar Spinal Cord With Implanted and Surface Electrodes: A Computer Simulation Study. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 2010, 18, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstoetter, U.S.; Freundl, B.; Binder, H.; Minassian, K. Common neural structures activated by epidural and transcutaneous lumbar spinal cord stimulation: Elicitation of posterior root-muscle reflexes. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0192013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.M.; Serrano-Muñoz, D.; Taylor, J.; Avendaño-Coy, J.; Gómez-Soriano, J. Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation and Motor Rehabilitation in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2019, 34, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minassian, K.; Persy, I.; Rattay, F.; Dimitrijevic, M.R.; Hofer, C.; Kern, H. Posterior root–muscle reflexes elicited by transcutaneous stimulation of the human lumbosacral cord. Muscle Nerve 2006, 35, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, L.V.; Miller, A.A.; Leech, K.A.; Salorio, C.; Martin, R.H. Feasibility and utility of transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation combined with walking-based therapy for people with motor incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2020, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeeva, N.; Broton, J.G.; Suys, S.; Calancie, B. Central Cord Syndrome of Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: Widespread Changes in Muscle Recruitment Studied by Voluntary Contractions and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Exp. Neurol. 1997, 148, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samejima, S.; Shackleton, C.; Malik, R.N.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Rempel, L.; Phan, A.-D.; Williams, A.; Nightingale, T.; Ghuman, A.; Elliott, S.; et al. Multi-system benefits of non-invasive spinal cord stimulation following cervical spinal cord injury: a case study. Bioelectron. Med. 2025, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minassian, K.; Freundl, B.; Lackner, P.; Hofstoetter, U.S. Transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation neuromodulates pre- and postsynaptic inhibition in the control of spinal spasticity. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjaria, M.; Momeni, K.; Ravi, M.; Bheemreddy, A.; Zhang, F.; Forrest, G. Improved Gait symmetry with spinal cord transcutaneous stimulation in individuals with spinal cord injury. 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC); LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, AustraliaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–4.

- Solinsky, R.; Burns, K.; Tuthill, C.; Hamner, J.W.; Taylor, J.A. Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation and its Impact on Cardiovascular Autonomic Regulation after Spinal Cord Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2023, 326, H116–H122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).