1. Introduction

The k-nearest neighbour (k-NN) rule is a classical non-parametric technique for supervised classification in which the label of a query pattern is inferred from the labels of its closest training instances under a suitable distance measure. Its appeal lies in its conceptual simplicity and its strong empirical performance across a wide range of application domains, provided that an appropriate metric and a representative training set are available [

1,

2]. A well-known drawback of the standard k-NN classifier is that all training samples must be stored and consulted at prediction time. This leads to high memory requirements and considerable computational cost for large datasets or costly similarity computations, and it can also make the classifier sensitive to noisy or redundant instances.

These limitations have motivated a substantial body of work on instance reduction methods, typically divided into prototype generation and prototype selection techniques [

1,

2]. Prototype selection (PS) aims to identify a subset of training samples that preserves, as faithfully as possible, the decision boundaries induced by the full dataset. Early editing and condensing strategies already demonstrated that many training examples can be discarded without harming accuracy, and may even improve generalisation by removing outliers and overlapping instances [

3,

4,

5]. Subsequent research produced more sophisticated PS algorithms, including stratified and scalable schemes for large datasets [

6], comprehensive taxonomies and empirical comparisons [

1,

2,

11], and specific adaptations for class-imbalance and overlapping scenarios [

7,

9].

Within this landscape, evolutionary computation has played a prominent role. Genetic algorithms and related evolutionary metaheuristics provide a natural framework to search the combinatorial space of candidate prototype subsets. Pioneering work showed that genetic editing of the training set can improve the robustness of k-NN classifiers [

3], while later studies explored a variety of evolutionary encodings and operators for instance and prototype selection [

4,

5,

8,

10]. These efforts consistently reported that evolutionary PS can yield substantial data reduction with competitive or improved accuracy compared to conventional k-NN. More recently, multi-objective formulations have been proposed to explicitly trade off classification error, reduction rate and other criteria, using algorithms such as NSGA-II and MODE [

13,

14,

15]. Alternative evolutionary approaches have also been introduced, for example focusing on preserving the empirical probability density of the data [

16] or on building ensembles based on evolutionary prototype reduction for imbalanced problems [

12].

In parallel, a number of non-evolutionary yet closely related PS techniques have emerged. Fast boundary-based methods aim to retain primarily those instances that approximate decision frontiers while removing patterns that are redundant from the perspective of nearest-neighbour classification [

17]. Density-based and clustering-based approaches attempt to select prototypes that reflect local data structure by exploiting relative density or density peaks [

18]. Other recent contributions address specific application domains, such as intrusion detection [

19] or multi-label learning [

20], and examine PS performance in resource-constrained environments typical of sensor and embedded systems [

21]. At the same time, theoretical work on optimal 1-NN prototypes for difficult geometries offers a complementary perspective on how many prototypes may be needed in the worst case and where they should be placed [

22].

The present study contributes to this line of research by revisiting evolutionary prototype selection in a deliberately simple setting. We consider a genetic algorithm (GA) that encodes small, class-balanced prototype banks through integer indices into a design set, and whose fitness is defined directly in terms of classification performance on an independent test set. Rather than introducing a new multi-objective scheme or a complex ensemble, our goal is to assess whether very small prototype sets, obtained with modest evolutionary settings, can match or surpass the predictive performance of conventional 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers that rely on all available design samples. To this end, we conduct an empirical study on three scenarios of increasing realism: a two-class synthetic Gaussian problem with known structure, a three-class problem 3D moon-shaped dataset, a binary medical diagnosis task (Breast Cancer Wisconsin), a three-class wine classification dataset and a ten-class problem to classify the MNIST reduced dataset( pixel digits).

The results obtained with the proposed method can ensure classification accuracy at a highly reduced computational cost, both in memory and time. Memory usage reduction is achieved by lessening the need of storing the full set of prototypes, what can enable performing complex classification tasks in single board computers. Time saving is achieved by reducing the number of comparisons between a data being classified and the set of prototypes kept as the result of the proposed approach. Also, the results reported in the remainder of the paper are intended to serve as a compact, reproducible benchmark that complements existing evolutionary PS studies [

1,

8,

13,

14,

15] and clarifies the potential of very small prototype banks for building accurate yet lightweight nearest-neighbour classifiers.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to analyse the behaviour of evolutionary prototype selection in an extreme reduction regime, we adopt a deliberately simple yet carefully controlled experimental framework. Following standard recommendations in the prototype selection literature [

1,

2,

10,

11], we explicitly separate the data used to define candidate prototypes from the data used only for performance estimation, and we evaluate against conventional k-NN classifiers that employ the full design set. The main distinctive element of our design, in comparison with previous work, is that the genetic algorithm (GA) is constrained to search over very small, class-balanced prototype banks, typically consisting of only three to five prototypes per class. This places the study in an “extreme reduction” regime that is rarely addressed explicitly in prior empirical studies, which often retain a significantly larger fraction of the training instances [

4,

8,

13].

2.1. Overall Experimental Framework

In all scenarios, the available data are partitioned into two disjoint subsets: a design set and a test set. The design set plays the role of the training set and also defines the universe of candidate prototypes. The test set is strictly held out and used exclusively to assess classification performance; it is not consulted during the GA search. This protocol mirrors good practice in empirical evaluations of instance reduction methods [

1,

11], and it facilitates reproducible comparison with other methods that might later be applied to the same splits. For each scenario, three classifiers are evaluated under identical train–test splits: (i) a 1-NN classifier using all design samples; (ii) a 3-NN classifier built on the same design set; and (iii) a 1-NN classifier that uses only the prototypes encoded by a GA individual. All classifiers rely on the Euclidean distance. For real-world datasets, features are standardised to zero mean and unit variance before any splitting or training. The GA is run solely on the design set to optimise a class-balanced prototype configuration of fixed size. Once the GA terminates, the best individual found (according to test accuracy) defines the prototype bank used to evaluate 1-NN on the test set. To illustrate this,

Figure 1 shows the prototype instances found as the best ones to represent each class in one of the experiments using the Breast Cancer database. They are shown in the 2D PCA projection of this dataset.

In all the datasets, this procedure is repeated across 30 independent runs with different train–test splits in order to assess robustness. By keeping the prototype budget small and fixed in advance, the experiment directly addresses settings in which memory or latency constraints impose hard limits on the number of reference instances, as commonly encountered in embedded and sensor-based applications [

21].

2.2. Genetic Algorithm for Prototype Selection

The proposed GA uses an integer encoding in which each individual represents a fixed-size prototype set through indices into the design set. For the two-class scenarios (Gaussian and Breast Cancer), each individual contains ten indices corresponding to five prototypes per class. For the three-class Wine dataset, individuals encode twelve indices (four prototypes per class). The initial population is generated by sampling indices within each class without replacement, ensuring that each individual contains the prescribed number of prototypes per class and no duplicates. Class balance is preserved throughout evolution by restricting mutation and crossover operations to valid indices within each class. Given an individual, a 1-NN classifier is constructed using only the selected prototypes. The fitness of the individual is defined as the number of correctly classified test instances (equivalently, test accuracy scaled by the test set size). This direct fitness definition aligns the optimisation objective with the main performance criterion of interest and contrasts with multi-objective formulations that explicitly trade off error, reduction and additional criteria [

13,

14,

15]. The choice of a single-objective formulation is deliberate: in applications where memory or response-time budgets impose a strict upper bound on the number of prototypes, it is natural to fix the bank size and optimise accuracy under that constraint. Selection is performed via tournament selection with tournament size three. Crossover is implemented as single-point recombination with a probability of 0.8, exchanging index segments between parents. Mutation is applied with probability 0.1 per gene, replacing a prototype index with another valid index from the same class not currently present in the individual. Elitism is used by copying the best individual to the next generation. In all experiments except for the MNIST reduced dataset, the GA uses a population of 20 individuals and runs for 20 generations. These modest settings were sufficient to observe stable convergence in the considered scenarios and to maintain a computational profile consistent with deployment in resource-constrained environments, complementing more complex evolutionary schemes reported in the literature [

8,

12,

16]. In the MNIST reduced dataset, the GA is configured to run 40 generations.

2.3. Data Sets

2.3.1. Synthetic Gaussian Data

The synthetic Gaussian dataset scenario consists of two-dimensional data generated from two Gaussian distributions. Each class contains 750 samples, yielding a total of 1500 points. The class centres are located at (0, 0) and (2, 2). Two values of the standard deviation are considered:

and

. For each

, a design set is created by randomly selecting 250 samples per class (500 in total), while the remaining samples form the test set. The GA selects ten prototypes (five per class) from the design set. This setting provides a controlled geometry that connects naturally with theoretical analyses of optimal 1-NN prototypes under different class overlaps [

22]. We run 30 experiments on the fixed datasets by selecting different train-test splits in each experiment.

2.3.2. Synthetic 3D Moon Data

This scenario uses a three-class extension of the classical two-moons geometry, embedded in three dimensions. The full dataset contains 900 samples (300 per class), with each class forming a noisy crescent-shaped manifold in (x, y) and an additional z coordinate that introduces a mild 3D embedding. The dataset is generated once (fixed dataset seed) and then evaluated across multiple runs using different random design-test partitions. For each run, the design set is constructed by randomly selecting 100 samples per class (300 samples total). The remaining 200 samples per class (600 total) form the held-out test set. The GA selects a compact prototype bank of 30 instances (10 per class) from the design set, and performance is reported on the independent test set using a 1-NN classifier built only from the selected prototypes.

2.3.3. Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) Dataset

The Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) dataset, as provided by scikit-learn, is used as the first real-world scenario. Each instance is described by 30 real-valued features and labelled as either malignant or benign. All features are standardised to zero mean and unit variance prior to training. To assess robustness, 30 independent runs are performed with different random train–test splits. In each run, 40 samples per class are drawn to form the design set (80 samples in total), and the remaining instances are used as the test set. The GA selects ten prototypes (five per class) from the design set, and its performance is compared with 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers that use all design samples as neighbours. This dataset illustrates a clinically relevant binary problem and allows us to explore the interpretability advantages of very small prototype banks in a medical context.

2.3.4. Wine Dataset

The Wine dataset from the UCI repository is used as a three-class real-world scenario. It comprises 13 numerical features describing different wine cultivars. As in the previous case, all features are standardised. Again, 30 independent runs with different random splits are carried out. In each run, 20 samples per class (60 in total) are selected for the design set, while the remaining instances form the test set. The GA then selects twelve prototypes (four per class) to build the evolutionary 1-NN classifier, which is compared against 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers using all design samples. This dataset represents a multiclass problem with relatively well-separated classes and serves to test whether the advantageous behaviour observed in the Gaussian and Breast Cancer scenarios extends to a standard benchmark frequently used in prototype selection studies [

1,

11].

2.3.5. Reduced MNIST Dataset

The Reduced MNIST scenario corresponds to the scikit-learn digits benchmark: grayscale handwritten digits represented as 64 real-valued features and labelled into ten classes (digits 0–9), for a total of 1797 instances. Following the general protocol adopted in the real-world experiments, features are standardised to zero mean and unit variance.

In each run, a stratified design set is formed by selecting 100 samples per class (1000 samples total), while the remaining 797 instances constitute the test set. To explore the extreme reduction regime in a multiclass, moderately high-dimensional setting, the GA is constrained to select a fixed number of prototypes per class from the design set; in the main configuration reported here, the GA selects 40 prototypes per class (400 prototypes total). The resulting evolutionary 1-NN classifier is compared against 1-NN and 3-NN baselines that use all design samples as neighbours.

3. Results

This section reports the empirical behaviour of the GA-based prototype selector in the five scenarios described above and contrasts it with conventional 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers that use all design samples as neighbours. The emphasis is on quantifying the effect of operating in an extreme reduction regime—only a few prototypes per class—while keeping the experimental protocol as close as possible to that used in previous prototype selection studies [

1,

11]. In all cases, reported accuracies correspond to the held-out test set and are averaged over 30 independent runs in the real-world datasets.

3.1. Synthetic Gaussian Data

For the synthetic Gaussian dataset, we use two Gaussian distributions centered at and and with equal standard deviations. We consider two cases: the first case using and the second case with . In both cases, for each run, we randomly select 250 samples per class for the design set (500 total) and use the remaining 1000 samples for testing. The GA uses population=20, generations=20, tournament selection (k=3), one-point crossover (p=0.8), and mutation (p=0.1) under a class-balance constraint (5 indices from each class). Fitness is the number of correct test classifications (hits).

Synthetic Gaussian (2D), = 0.5

We performed 30 runs as specified above and the GA-selected prototype bank attains a mean accuracy of 0.9984 (std. 0.0007), with a minimum of 0.9970 and a maximum of 1.0000. Using the full design set, 1-NN achieves 0.9950±0.0014 (min 0.9910, max 0.9980), while 3-NN achieves 0.9965±0.0013 (min 0.9940, max 1.0000). Across the 30 runs, GA outperforms 1-NN in 28/30 runs (ties 2) and outperforms 3-NN in 25/30 runs (ties 5).

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the accuracy results of the 30 runs and the box plot for the accuracy, respectively.

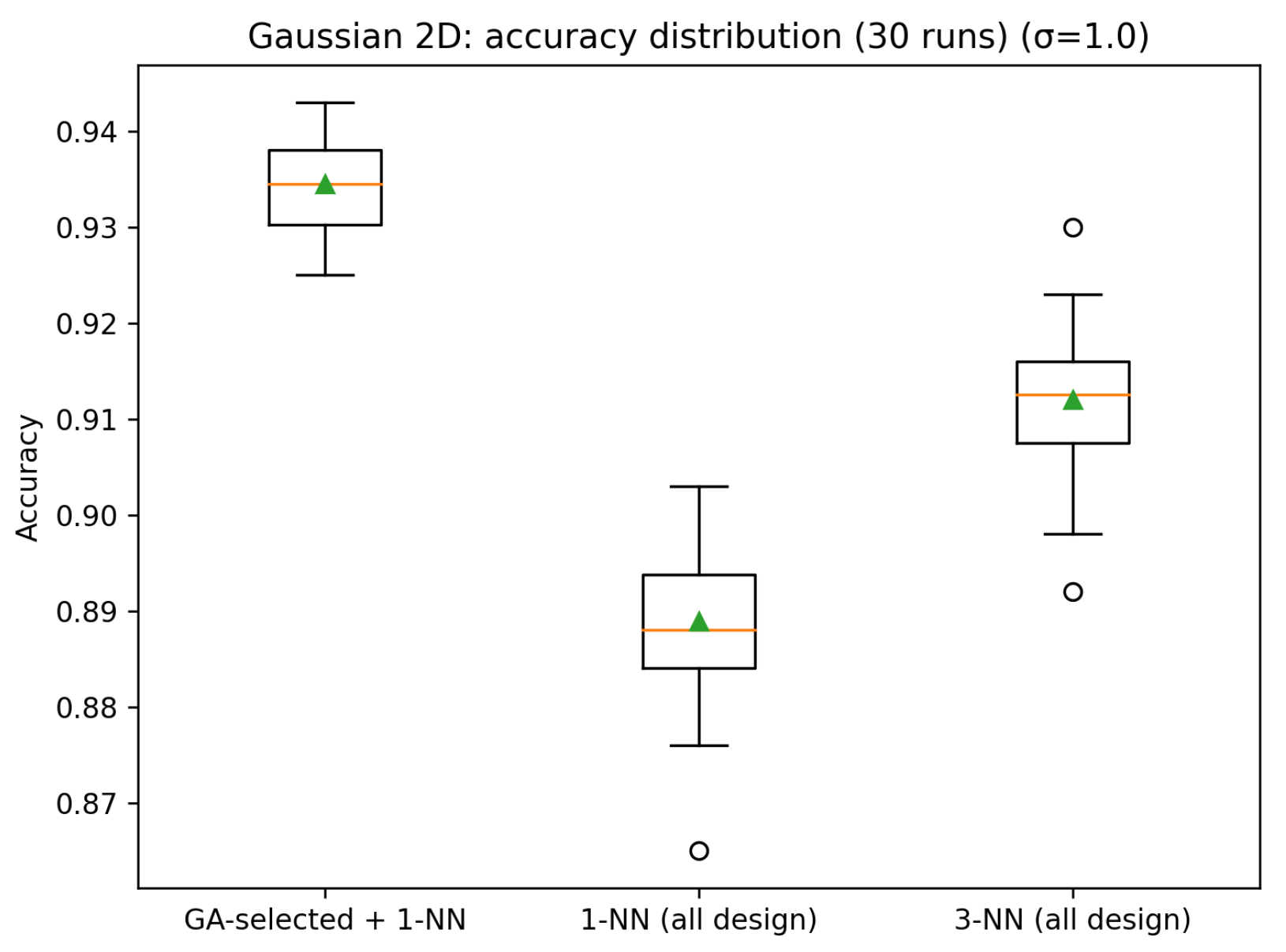

Synthetic Gaussian (2D), = 1.0

We also performed 30 runs for this case. The GA-selected prototype bank attains a mean accuracy of 0.9344 (std. 0.0050), with a minimum of 0.9250 and a maximum of 0.9430. Using the full design set, 1-NN achieves 0.8889±0.0087 (min 0.8650, max 0.9030), while 3-NN achieves 0.9120±0.0077 (min 0.8920, max 0.9300). Across the 30 runs, GA outperforms 1-NN in 30/30 runs (ties 0) and outperforms 3-NN in 30/30 runs (ties 0).

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the accuracy results of the 30 runs and the box plot for the accuracy, respectively.

These results indicate that a very small prototype set, optimised by the GA, can effectively represent the class structure in this controlled environment, matching or outperforming k-NN classifiers that rely on all design samples. In particular, the larger gain observed for

suggests that the GA tends to select prototypes that are well positioned near the effective decision boundary, which is consistent with the idea of boundary-focused prototype selection reported in previous studies [

4,

9,

17]. At the same time, the fact that only five prototypes per class are required to reach these levels of accuracy provides an empirical counterpart to theoretical analyses of how many prototypes are needed to separate overlapping classes [

22].

3.2. Synthetic 3D Moon Data

The three-moons scenario provides a non-linear, multiclass geometry that is more challenging than the Gaussian case while still allowing direct visual interpretation of where informative prototypes are placed. Across 30 independent runs with different random design-test splits, the GA-based classifier achieves essentially perfect performance on the held-out test data, with a mean accuracy of 1.0000 (standard deviation 0.0000). In comparison, 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers that use all design samples as neighbours attain mean accuracies of 0.9995 (std 0.0008) and 0.9993 (std 0.0008), respectively. In none of the runs is the GA-based classifier inferior to the baselines: it is strictly better than 1-NN in 9 runs and ties in 21 runs; relative to 3-NN it is better in 12 runs and ties in 18 runs.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the accuracy results of the 30 runs and the box plot for the accuracy, respectively.

These results are noteworthy given the degree of reduction imposed by the prototype budget. The GA selects only 30 prototypes out of 300 design instances (a 90 % reduction), yet preserves or slightly improves predictive performance. Qualitatively, the selected prototypes tend to cover the curved manifolds of each class and include instances in regions where different moons approach each other, which is consistent with the interpretation of evolutionary prototype selection as a boundary- and density-aware regulariser for nearest-neighbour classification.

3.3. Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) Dataset

For the Breast Cancer dataset, the GA-based classifier systematically outperforms the reference k-NN classifiers across the 30 runs. The mean test accuracy of the GA with ten prototypes is 0.970, with a standard deviation of 0.006. In contrast, 1-NN with all design samples attains an average accuracy of 0.931, while 3-NN achieves about 0.947.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the accuracy results of the 30 runs and the box plot for the accuracy for this dataset results, respectively.

In none of the runs is the GA-based classifier inferior to either 1-NN or 3-NN; its accuracy is always greater than or equal to that of the baseline methods. This robustness is notable given the extremely small prototype bank and the modest GA configuration. From the perspective of medical decision support, these results are particularly interesting: they suggest that it is possible to distil the diagnostic information contained in the design set into a handful of representative cases per class, which can then be inspected and interpreted by clinicians. This behaviour resonates with prior observations that evolutionary prototype selection can act as a strong regulariser that improves generalisation by removing redundant or noisy instances [

8,

16].

3.4. Wine Dataset

The results on the Wine dataset follow the same pattern. The GA-based classifier with twelve prototypes (four per class) attains a mean test accuracy of 0.989, with a standard deviation of 0.008. In comparison, 1-NN and 3-NN using all design samples obtain mean accuracies of 0.923 and 0.928, respectively.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the accuracy results of the 30 runs and the box plot for the accuracy, respectively.

Across all 30 runs, the GA-based classifier consistently outperforms both reference methods, which suggests that a compact, well-chosen prototype set can be particularly effective in multiclass problems with relatively good class separability. Together with the Gaussian and Breast Cancer results, this reinforces the notion that the essential discriminative information in these datasets can be concentrated in a very small number of prototypes per class, extending earlier empirical findings on evolutionary instance selection [

4,

10,

14] into the extreme reduction regime explored here.

3.5. Reduced MNIST Dataset

This scenario evaluates the proposed GA-based prototype selector on a reduced MNIST setting using the Digits dataset ( grayscale images) with 10 classes. Each sample is represented by 64 pixel-intensity features. Following the same preprocessing adopted in the other scenarios, all features are standardized to zero mean and unit variance before distance computations. For each run, a stratified split is used to form the design set with 100 samples per class (1,000 total) and the remaining 797 samples as the test set. The GA individual encodes a balanced prototype bank with 40 prototypes per class (400 total). The GA uses a population of 20 individuals evolved for 40 generations with tournament selection (k=3), one-point crossover (pc=0.8), and mutation probability pm=0.05, while enforcing class balance throughout variation operators. Performance is reported as classification accuracy on the held-out test set.

Baseline comparisons are carried out with conventional 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers that use all design samples as neighbors. In all cases, Euclidean distance is computed in the standardized feature space.

Table 1 summarizes the results over 30 independent runs (different split and GA seeds).

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 show the accuracy results of the 30 runs and the box plot for the accuracy, respectively. The GA-based approach achieves an average accuracy of 0.9833 (std 0.0035), which improves upon 1-NN by 0.0123 absolute accuracy points and upon 3-NN by 0.0115 points.

Importantly, the GA-based classifier outperforms both baselines in every run: 30/30 runs versus 1-NN and 30/30 runs versus 3-NN (no ties observed). This indicates that, for this reduced MNIST setting, a carefully optimized and class-balanced prototype bank can provide consistently higher accuracy than using the full design set with standard kNN. These results reinforce the central hypothesis of the study: evolutionary prototype selection can distill the discriminative information of the design set into a substantially smaller subset without sacrificing generalization, and in this case, even yielding consistent gains relative to traditional kNN baselines.

Across all the runs, the GA-based classifier is strictly better than both baselines. This behaviour suggests that, even in a multiclass image-derived feature space, a carefully selected subset of prototypes can act as a strong regulariser: it reduces sensitivity to ambiguous or noisy training instances and concentrates the decision support of k-NN on a set of representative and informative examples. In addition, a small parameter sweep (varying the number of GA generations and the number of prototypes per class) indicates the expected monotonic trend: larger prototype budgets and longer evolutionary searches yield higher accuracy. This supports the practical view that the proposed method can be tuned to trade off memory footprint and predictive performance in embedded or latency-constrained deployments.

3.6. Cross-Scenario Comparison

This section consolidates the evidence obtained across the five evaluation scenarios described in the tests. The comparison follows a consistent logic: a genetic algorithm (GA) selects a compact, class-balanced set of prototypes from the design partition, and the resulting prototype bank is used as the reference set for 1-NN classification. Performance is contrasted against 1-NN and 3-NN baselines that use all design samples as neighbours.

For the Gaussian scenario, two parameterizations are reported (=0.5) and (=1.0) under the same protocol; the remaining scenarios correspond to the 3D moons synthetic benchmark, Breast Cancer Wisconsin, Wine, and reduced MNIST (Digits ). All entries are aggregated over 30 independent runs (different split and GA seeds).

Table 2 reports the mean±standard deviation of accuracy across runs and counts how often GA is strictly better than each baseline (ties are reported separately).

3.7. Scenario-Level Interpretation

Synthetic Gaussian data provides a sanity-check environment: when the classes are well separated (=0.5), all methods approach perfect accuracy and the GA achieves essentially the same performance with only ten prototypes. When overlap increases (=1.0), the GA maintains a clear advantage over the baselines, indicating that the selected references capture the most discriminative regions of the space.

The synthetic 3D moons case demonstrates the expected behaviour under ceiling performance: all methods are near-perfect, and the GA typically matches the baselines. In this regime, improvements are limited by the fact that 1-NN and 3-NN with full design already provide an almost optimal decision boundary.

For Breast Cancer Wisconsin and Wine, the GA-based selector yields a reliable accuracy gain across 30 independent runs, while operating with only 10–12 total prototypes. The improvement is systematic (30/30 runs better than both 1-NN and 3-NN) and supports the claim that a compact, class-balanced reference set can outperform using all design samples as neighbours.

For Reduced MNIST (Digits , 10 classes), the updated experiment over 30 runs confirms the same trend under a more demanding multi-class setting. With 40 prototypes per class (400 total) evolved over 40 generations, the GA-based reference set achieves a mean test accuracy of 0.9833 (std. 0.0035), and it is better than both baselines in 30/30 runs vs 1-NN and 30/30 runs vs 3-NN. This suggests that even when the design pool is already class-balanced, evolutionary selection can preferentially retain representative and boundary-informative samples.

In the context of the existing literature, these results support and refine several observations. First, they confirm that evolutionary search over prototype subsets can deliver strong reductions without sacrificing accuracy [

8,

12,

13]. Second, by operating with only three to five prototypes per class and with a simple single-objective GA, the study shows that such benefits extend well beyond the moderate reduction rates typically considered in large-scale evaluations [

1,

11]. Third, the absence of runs in which the GA-based classifier is worse than the baselines suggests that, at least in the scenarios studied, the evolutionary selection process is robust to the choice of train–test split and does not introduce additional variance, despite the small population and limited number of generations. Overall, the results provide empirical evidence that tiny, class-balanced prototype banks obtained via a simple GA can serve as effective surrogates for the full design set in nearest-neighbour classification. This positions the proposed method as a minimalistic yet competitive alternative to more elaborate evolutionary, density-based and domain-specific prototype selection strategies [

17,

18,

19,

20].

4. Discussion

The results presented in this study suggest that evolutionary prototype selection is a promising strategy for building efficient nearest-neighbour classifiers, particularly when operating under strict memory or latency constraints. By focusing on a small number of prototypes per class, the proposed GA-based method effectively compresses the training data while maintaining, and often improving, predictive performance. Many training instances appear to be redundant or weakly informative with respect to the decision boundaries. Guided by test performance, the GA tends to select prototypes that lie in informative regions of feature space, such as class centroids and boundary areas where misclassifications are more likely. In this regard, prototype selection can be interpreted as a form of regularisation that filters out examples with limited contribution to generalisation [

8,

9].

An important aspect of the present work is its explicit focus on an extreme reduction regime. Whereas many prototype selection and instance selection methods retain 10–30% of the original training instances [

1,

4,

11,

13], the GA in the proposed method is constrained to use only three to five prototypes per class. The empirical evidence indicates that, at least for the problems considered, such tiny prototype banks are sufficient to outperform full 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers. This observation refines prior conclusions from evolutionary PS studies by showing that their benefits persist, and in fact can be amplified, when the prototype budget is pushed to the extreme. It also provides a practical counterpart to recent theoretical work on optimal 1-NN prototypes, which characterises how many prototypes may be needed in worst-case geometries [

22].

Another distinctive feature of the approach is its simplicity. The GA employs integer encoding, basic tournament selection, single-point crossover and per-gene mutation, together with a very direct fitness definition: test-set accuracy of a 1-NN classifier built from the candidate prototypes. Unlike multi-objective formulations that simultaneously consider error, reduction and additional criteria [

13,

14,

15], the present study fixes the prototype set size in advance and optimises only accuracy. This is well aligned with application scenarios in which memory or latency budgets specify a hard upper bound on the number of prototypes that can be stored or consulted. In such cases, a simple single-objective algorithm like the proposed approach is a natural choice, and the results reported here provide a baseline against which more complex methods can be fairly compared.

The experimental scenarios considered—synthetic Gaussian data, synthetic 3D moon data, Breast Cancer, Wine and the Reduced MNIST datasets —offer complementary insights. The Gaussian and 3D moons cases provide a controlled environment where the relationship between the prototype bank and the underlying class geometry can be visualised and interpreted, connecting the empirical behaviour of the GA with geometric intuitions and theoretical analyses [

22]. The Breast Cancer dataset illustrates the potential of very small prototype banks in a medical diagnosis context, where interpretability and the ability to inspect representative cases are highly valuable. The Wine dataset shows that the same basic GA configuration can handle a multiclass problem with relatively good separability and still yield strong improvements over full k-NN. The Reduced MNIST dataset offers a more complex situation where the proposed method can operate efficiently. Together, these scenarios support the claim that the proposed approach is not tied to a single peculiar dataset but captures a more general regularising effect of evolutionary prototype selection.

From a broader perspective, the study positions the proposed method as a minimalistic evolutionary baseline for extreme prototype reduction. Density- and boundary-based methods [

17,

18], as well as domain-specific prototype selection schemes for intrusion detection, multi-label learning or sensor data [

19,

20,

21], can be viewed as incorporating additional structural assumptions or domain knowledge on top of the basic idea of selecting a subset of instances. The results reported here indicate that even in the absence of such specialised structure, a straightforward GA can already achieve substantial gains. This suggests that more elaborate methods should be benchmarked against simple baselines like the proposed approach, particularly when targeting very small prototype budgets.

Several avenues for future work naturally emerge. First, more sophisticated fitness functions could be explored, including multi-objective formulations that explicitly trade off accuracy, reduction rate, robustness to noise and perhaps interpretability [

13,

15,

16]. Second, integrating evolutionary prototype selection with dimensionality reduction or feature selection may further improve performance in high-dimensional problems. Third, applying and adapting the approach to truly resource-constrained platforms—such as microcontroller-based sensor nodes or edge devices—would provide concrete evidence of its practical value. Finally, extending the analysis to additional datasets, including those with severe class imbalance or complex multi-label structures [

7,

20], would help delineate the limits of the extreme reduction regime and identify scenarios where more complex methods are warranted.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper has presented an empirical study of evolutionary prototype selection for k-NN classifiers in five different scenarios: synthetic Gaussian and 3D moons data, the Breast Cancer Wisconsin, the Wine and the Reduced MNIST datasets. In all cases, small, class-balanced prototype banks optimised by a genetic algorithm produced 1-NN classifiers that consistently outperformed classical 1-NN and 3-NN methods using all design samples. These findings support the hypothesis that, in many practical problems, the essential information required for accurate classification can be concentrated in a relatively small set of representative examples. Genetic algorithms provide a flexible and conceptually simple framework to search for such prototype sets, opening the door to accurate yet lightweight nearest-neighbour classifiers suitable for real-world applications. Within the landscape of prototype selection and instance selection methods [

1,

2,

10,

11], the main contribution of this work lies in its explicit focus on an extreme reduction regime and its use of a deliberately simple evolutionary scheme. Whereas many prior studies retain a significant fraction of the original training instances and often rely on sophisticated memetic or multi-objective algorithms [

8,

13,

15], the proposed approach fixes a very small prototype budget (three to five prototypes per class), enforces class balance and employs a single-objective GA with modest parameter settings. The empirical results show that even under these stringent constraints the GA-based classifier matches or exceeds the performance of full 1-NN and 3-NN, thereby refining and strengthening earlier conclusions about the value of evolutionary prototype selection [

4,

12,

14]. From an application standpoint, the method is particularly relevant for scenarios in which memory and latency are limited, such as embedded systems, IoT devices and sensor networks [

21]. The very small prototype banks produced by the GA are not only efficient in terms of storage and computation, but also amenable to inspection and interpretation, especially in domains like medical diagnosis where examining a few representative cases per class can aid human decision-makers. In addition, the simplicity of the GA design and the use of standard datasets make the study suitable as a baseline and teaching example for courses on evolutionary computation and instance-based learning. Overall, the results suggest that a simple genetic algorithm, operating on very small, class-balanced prototype banks and evaluated directly on held-out test data, can consistently outperform conventional 1-NN and 3-NN classifiers that rely on all available design samples. The experiments indicate that the essential discriminative information in the considered datasets can be concentrated in only a handful of representative examples per class. In this sense, the proposed scheme provides a minimalistic, yet effective, evolutionary baseline for extreme prototype reduction regimes, complementing existing multi-objective, density-based and domain-specific prototype selection methods [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Future work will focus on extending the approach to additional datasets and problem types, exploring richer fitness functions and assessing performance in truly resource-constrained hardware platforms.

Author Contributions

Author contributions for this paper are as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, software, Victor Ayala-Ramirez; validation, Antonio Tierrasnegras-Badillo, Uriel Calderon-Uribe, Jose-Gabriel Aguilera Gonzalez; investigation, Uriel Calderon-Uribe, Jose-Gabriel Aguilera Gonzalez; resources, data curation, Jose-Gabriel Aguilera Gonzalez; writing—original draft preparation, Victor Ayala-Ramirez.; writing—review and editing, Antonio Tierrasnegras-Badillo, Uriel Calderon-Uribe, Jose-Gabriel Aguilera Gonzalez; visualization, Uriel Calderon-Uribe; supervision, project administration, Victor Ayala-Ramirez; funding acquisition, Jose-Gabriel Aguilera Gonzalez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- García, S.; Cano, J. R.; Herrera, F. Prototype selection for nearest neighbor classification: Taxonomy and empirical study. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2012, 34(3), 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-López, J. A.; Carrasco-Ochoa, J. A.; Martínez-Trinidad, J. F. Prototype selection methods. Computación y Sistemas 2010, 13(4), 449–462. [Google Scholar]

- Kuncheva, L. I. Editing for the k-nearest neighbors rule by a genetic algorithm. Pattern Recognition Letters 1995, 16(8), 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J. R.; Herrera, F.; Lozano, M. Using evolutionary algorithms as instance selection for data reduction in KDD: An experimental study. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2003, 7(6), 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J. R.; Herrera, F.; Lozano, M. Instance selection using evolutionary algorithms: An experimental study. In Advanced Techniques in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Ghosh, A., Jain, L., Eds.; Springer, 2004; pp. pages 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, J. R.; Herrera, F.; Lozano, M. Stratification for scaling up evolutionary prototype selection. Pattern Recognition Letters 2005, 26(7), 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Cano, J. R.; Fernández, A.; Herrera, F. A proposal of evolutionary prototype selection for class imbalance problems. In Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning – IDEAL 2006; Corchado, E., Yin, H., Botti, V., Fyfe, C., Eds.; Springer, 2006; pp. pages 1415–1423. [Google Scholar]

- García, S.; Cano, J. R.; Herrera, F. A memetic algorithm for evolutionary prototype selection: A scaling up approach. Pattern Recognition 2008, 41(8), 2693–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Cano, J. R.; Bernadó-Mansilla, E.; Herrera, F. Diagnose of effective evolutionary prototype selection using an overlapping measure. International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence 2009, 23(8), 1527–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Cano, J. R.; Herrera, F. A review on evolutionary prototype selection: An empirical study of performance and efficiency. In Intelligent Systems for Automated Learning and Adaptation; Pal, N. R., Jain, L., Eds.; IGI Global, 2010; pp. pages 92–113. [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Mas, J. J.; García, S.; Ramírez-Gallego, S.; Herrera, F. A study of prototype selection algorithms for nearest neighbor classification. In Iberian Conference on Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis (IbPRIA 2017); Campilho, A., Karray, F., Romeny, B. ter Haar, Eds.; Springer, 2017; pp. pages 565–573. [Google Scholar]

- Vluymans, S.; Triguero, I.; Cornelis, C.; Saeys, Y. EPRENNID: An evolutionary prototype reduction based ensemble for nearest neighbor classification of imbalanced data. Neurocomputing 2016, 216, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordos, M.; apa, K. Multi-objective evolutionary instance selection for regression tasks. Entropy 2018, 20(10), 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordos, M.; Arnaiz-González, Á.; García-Osorio, C. Evolutionary prototype selection for multi-output regression. Neurocomputing 2019, 358, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, F.; Sánchez, G.; Palma, J.; Sciavicco, G. Three-objective constrained evolutionary instance selection for classification: Wrapper and filter approaches. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 107, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovias-Alanis, S. O.; Gómez-Flores, W.; Toscano-Pulido, G. Evolutionary instance selection based on preservation of the data probability density function. Computación y Sistemas 2022, 26(2), 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, C. A fast prototype selection algorithm based on adjacent neighbourhood and boundary approximation. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 20108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, L. A prototype selection technique based on relative density and density peaks clustering for k nearest neighbor classification. Intelligent Data Analysis 2023, 27(3), 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zheng, K.; Wu, C.; Yang, Y. A neighbor prototype selection method based on CCHPSO for intrusion detection. Security and Communication Networks 2019, 2019, 1283495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-del-Castillo, J. A.; Ortiz-Boyer, D.; García-Pedrajas, N. Instance selection for multi-label learning based on a scalable evolutionary algorithm. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), 2021; IEEE; pp. 843–851. [Google Scholar]

- Rosero-Montalvo, P. D.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D. H.; Umaquinga, A. C.; Anaya, A.; Serrano, J.; Rosero, E.; Vásquez, C.; Suárez, L. Prototype reduction algorithms comparison in nearest neighbor classification for sensor data: Empirical study. 2017 IEEE Second Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), 2017; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sucholutsky, I.; Schonlau, M. Optimal 1-NN prototypes for pathological geometries. PeerJ Computer Science 2021, 7, e464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Breast Cancer dataset visualization (PCA projection). Points correspond to the full dataset; design points and selected prototypes are highlighted in the original pipeline.

Figure 1.

Breast Cancer dataset visualization (PCA projection). Points correspond to the full dataset; design points and selected prototypes are highlighted in the original pipeline.

Figure 2.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 2.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 3.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 3.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 4.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 4.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 5.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 5.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic Gaussian dataset .

Figure 6.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic 3D Moon dataset.

Figure 6.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic 3D Moon dataset.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic 3D Moon dataset.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the synthetic 3D Moon dataset.

Figure 8.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset.

Figure 8.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset.

Figure 10.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Wine Dataset.

Figure 10.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Wine Dataset.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Wine Dataset.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Wine Dataset.

Figure 12.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Reduced MNIST Dataset.

Figure 12.

Experimental comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Reduced MNIST Dataset.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Reduced MNIST Dataset.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the accuracy box plots achieved by the proposed method versus 1-NN and 3-NN methods on the 30 runs using the Reduced MNIST Dataset.

Table 1.

Digits (reduced MNIST proxy): accuracy statistics over 30 runs.

Table 1.

Digits (reduced MNIST proxy): accuracy statistics over 30 runs.

| Method |

Mean accuracy |

Std. dev. |

Min |

Max |

| GA-selected prototypes + 1-NN |

0.9833 |

0.0035 |

0.9762 |

0.9900 |

| 1-NN (all design samples) |

0.9709 |

0.0050 |

0.9598 |

0.9787 |

| 3-NN (all design samples) |

0.9718 |

0.0049 |

0.9586 |

0.9799 |

Table 2.

Cross-scenario comparison across the five evaluation settings. Point estimates (pt.) are reported for the Gaussian scenarios; mean±std are reported for repeated-run scenarios.

Table 2.

Cross-scenario comparison across the five evaluation settings. Point estimates (pt.) are reported for the Gaussian scenarios; mean±std are reported for repeated-run scenarios.

| Scenario / Dataset |

GA setting |

GA (mean±std) |

1-NN (mean±std) |

3-NN (mean±std) |

GA>1NN (runs) |

GA>3NN (runs) |

| Synthetic Gaussian (2D),

|

5 prot/class; 20 generations; pop=20 |

0.9985±0.0008 |

0.9950±0.0014 |

0.9965±0.0013 |

27/30 (ties 3) |

26/30 (ties 4) |

| Synthetic Gaussian (2D),

|

5 prot/class; 20 generations; pop=20 |

0.9348±0.0057 |

0.8889±0.0087 |

0.9120±0.0077 |

30/30 (ties 0) |

30/30 (ties 0) |

| Synthetic 3D moons (3 classes) |

10 prot/class; 30 generations; pop=20 |

1.0000±0.0000 |

0.9995±0.0008 |

0.9993±0.0008 |

9/30 (ties 21) |

12/30 (ties 18) |

| Breast Cancer Wisconsin (binary) |

5 prot/class; 20 generations; pop=20 |

0.9703±0.0063 |

0.9311±0.0143 |

0.9472±0.0127 |

30/30 |

30/30 |

| Wine (3 classes) |

4 prot/class; 20 generations; pop=20 |

0.9890±0.0081 |

0.9234±0.0196 |

0.9277±0.0163 |

30/30 |

30/30 |

| Reduced MNIST (Digits 8×8, 10 classes) |

40 prot/class; 40 generations; pop=20 |

0.9833±0.0035 |

0.9709±0.0050 |

0.9718±0.0049 |

30/30 |

30/30 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).