1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is increasingly recognized as a disease driven not only by lipid accumulation but also by complex paracrine and intracrine signals within the vascular wall. Although VD has been linked to cardiovascular health, its mechanistic role in vascular biology remains unclear, and clinical studies have yielded inconsistent results. A largely overlooked factor is the considerable interindividual variability in biological responsiveness to VD, which may influence endothelial function, vascular smooth muscle cell behavior, and calcification independently of serum 25(OH)D₃ levels. There is also evidence suggesting that dysregulated VD signaling may influence sterol metabolism, potentially contributing to lipid abnormalities observed in individuals with impaired CYP24A1 activity. This review synthesizes current evidence on how altered VD metabolism—particularly hypersensitivity associated with impaired CYP24A1-mediated catabolism—may act as a modifier of vascular phenotype and calcification. By integrating vascular cell biology with emerging concepts of VD responsiveness, we propose a unifying mechanism that may help explain the heterogeneity of cardiovascular responses to VD exposure.

Observational studies have consistently associated low VD status with increased cardiovascular risk, whereas interventional and Mendelian randomization trials have failed to establish causality. This discrepancy reflects, at least in part, the weak correlation between circulating VD metabolites and tissue-specific biological activity. Two factors may therefore be essential for interpreting cardiovascular outcomes: marked variability in VD responsiveness and the potential importance of local, intracrine VD activation within vascular tissues. Considering these mechanisms may help refine interpretations of prior studies, improve mechanistic understanding of VD-related vascular effects, and guide more individualized clinical approaches.

Atherosclerosis and Its Vascular Complications

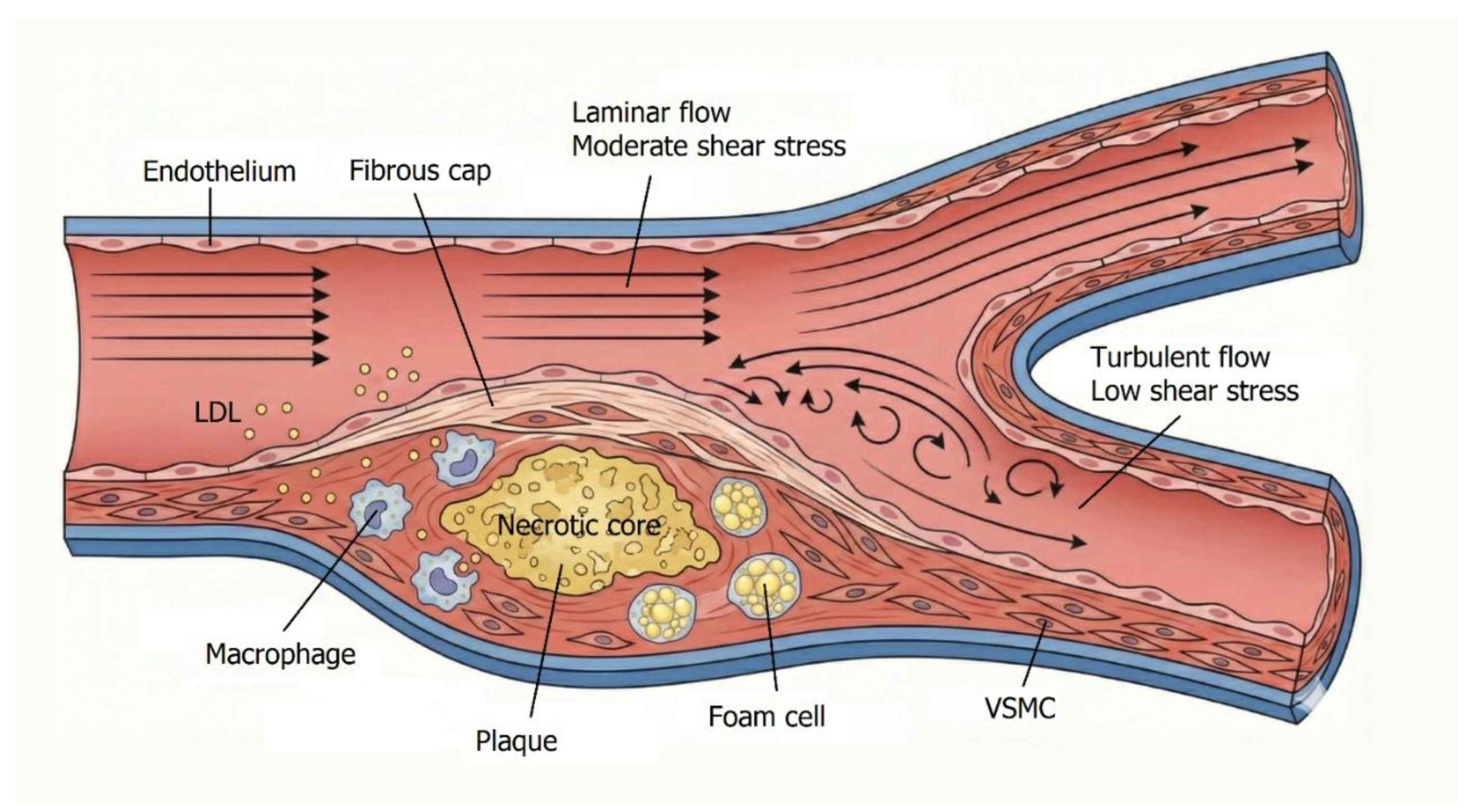

Atherosclerotic diseases, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, remain the leading causes of death worldwide. Atherosclerosis is a multifactorial condition influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, with clinical manifestations developing gradually over decades. Major risk factors include hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking. However, increasing evidence supports the view that atherosclerosis represents a chronic inflammatory process initiated by endothelial injury and perpetuated by metabolic and hemodynamic stressors. Vascular endothelium, a monolayer of endothelial cells (ECs) lining the entire vascular system, serves as a critical regulatory interface between blood and tissues. In large and medium-sized arteries, ECs are in direct contact with the tunica media, composed of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), elastic fibers, and collagen, which is surrounded by the connective tissue–rich tunica adventitia. [

1]

Mechanical forces acting on the vessel wall include circumferential tensile stress from blood pressure and wall shear stress (WSS), the tangential frictional force generated by blood flow. Low or oscillatory WSS occurs in areas of disturbed flow, such as arterial bifurcations, which are particularly prone to atherosclerotic plaque formation. Hemodynamic stress alters endothelial signaling and promotes a proinflammatory phenotype, creating a permissive environment for lesion development. [

1]

Atherosclerosis begins with endothelial dysfunction, characterized by increased permeability, leukocyte adhesion, and prothrombotic changes at the endothelial surface [

1]. Retention and modification of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) within the intima constitute a pivotal early event. Modified LDL particles activate ECs and recruit monocytes, which differentiate into macrophages. These macrophages, along with VSMCs, engulf LDL and transform into foam cells, forming the fatty streak—the earliest visible lesion of atherosclerosis. As foam cells accumulate, they release cytokines and growth factors that recruit additional inflammatory cells and stimulate VSMC proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition. This process leads to plaque growth and the formation of a necrotic core rich in lipids and cellular debris, surrounded by a fibrous cap composed of collagen and VSMCs. The cap stabilizes the lesion; however, persistent inflammation weakens it, predisposing it to rupture. Hemodynamic factors further exacerbate this process—turbulent flow sustains inflammation and facilitates LDL infiltration by prolonging residence time and disrupting endothelial integrity. [

1]

In advanced stages, plaque calcification occurs, mimicking bone formation. VSMCs and pericytes may transdifferentiate into osteoblast-like cells, depositing calcium within the lesion. Microcalcifications may coalesce into macrocalcifications, stiffening the vessel wall and contributing to plaque instability. [

1] (

Figure 1).

Plaque rupture represents a critical event in acute cardiovascular syndromes. Exposure of thrombogenic material to the bloodstream triggers platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Vessel occlusion can result in myocardial infarction or stroke, while embolization may cause ischemia in distal tissues. The progression from subclinical lesions to symptomatic disease underscores the importance of plaque stability. Stable plaques, characterized by thick fibrous caps and limited inflammation, often remain clinically silent, whereas unstable plaques with thin caps and active inflammation are prone to rupture. Even without complete occlusion, enlarging plaques may reduce coronary perfusion, leading to chronic ischemic conditions such as angina pectoris or heart failure [

2].

Atherosclerosis is a complex, multifactorial disease driven by endothelial dysfunction, lipid accumulation, chronic inflammation, and hemodynamic stress. It progresses from initial fatty streaks to advanced, calcified plaques that may rupture and precipitate life-threatening cardiovascular events. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular and biomechanical mechanisms underlying these processes is essential for developing effective preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Recent evidence suggests that VD may influence several of these pathophysiological pathways, particularly those involving endothelial function, inflammation, and vascular calcification (See paragraph 3). These observations have stimulated growing interest in the potential role of VD as a modulator of vascular health and disease.

2. Endocrinology of Vitamin D

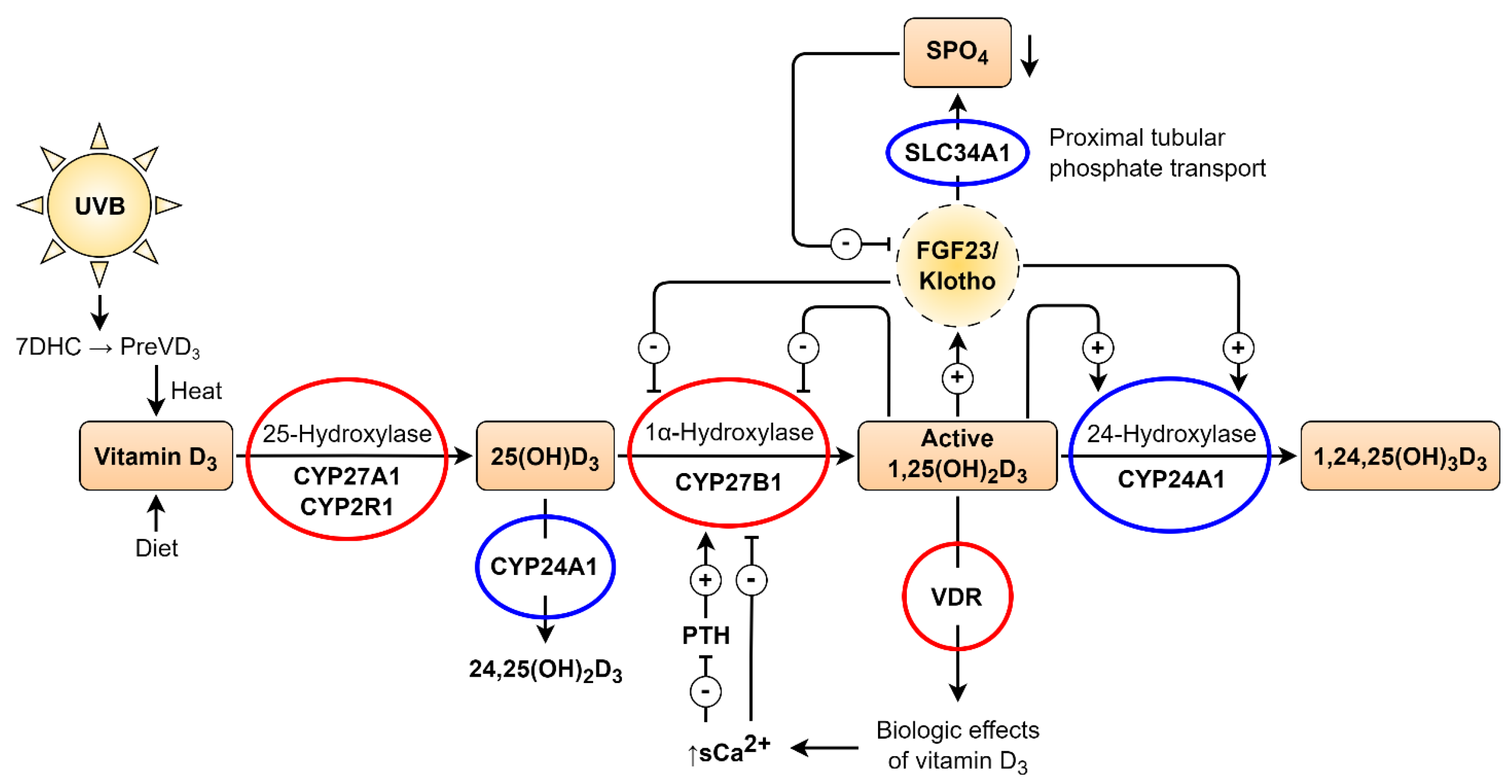

VD is a secosteroid hormone that can be synthesized de novo in the skin through ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure, which converts 7-dehydrocholesterol (7DHC) into cholecalciferol, or obtained from dietary sources. Once absorbed or synthesized, cholecalciferol binds to the VD-binding protein (VDBP) and is transported to the liver. Hepatic enzymes CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 (25-hydroxylases) convert VD to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], which has a relatively long half-life and serves as the principal circulating biomarker of VD status. [

3]

The second hydroxylation step occurs in the kidneys, where 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) converts 25(OH)D into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D₃ [1,25(OH)₂D₃], the biologically active form, within the proximal renal tubule. The active hormone is released into the bloodstream, where it binds to VDBP and exerts its effects through the VD receptor (VDR). The VDR is a ligand-activated transcription factor expressed in nearly all tissues. As a lipophilic hormone, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ readily crosses cell membranes and binds to cytoplasmic or nuclear VDR in target cells. Genome-wide analyses have identified thousands of VDR binding sites regulating the expression of hundreds of genes involved in calcium and phosphate homeostasis, immunity, inflammation, and cardiovascular function. This extensive genomic activity underlies the pleiotropic effects of VD. [

3]

VD metabolism is tightly regulated by calcium, phosphate, fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), and parathyroid hormone (PTH). FGF23 suppresses CYP27B1 expression, reducing 1,25(OH)₂D₃ synthesis and promoting its catabolism. [

4] In contrast, PTH stimulates CYP27B1 activity, increasing 1,25(OH)₂D₃ production. Elevated ionized calcium levels inhibit PTH secretion in the parathyroid glands, thereby reducing renal 1,25(OH)₂D₃ synthesis. Hyperphosphatemia also inhibits CYP27B1 activity in the kidney. When present in excess, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ induces negative feedback by downregulating CYP27B1 expression in the kidney, repressing PTH gene transcription in the parathyroid glands, and enhancing FGF23 secretion in bone. These feedback loops maintain circulating 1,25(OH)₂D₃ concentrations within narrow physiological limits, even under conditions of severe VD deficiency characterized by markedly reduced 25(OH)D levels. [

3]

Beyond its classical renal pathway, VD can also be activated extra-renally in tissues expressing CYP27B1 [

5]. In such sites, circulating 25(OH)D serves as a substrate for local 1,25(OH)₂D₃ synthesis. Locally produced 1,25(OH)₂D₃ may exert autocrine and paracrine effects in cells that express the VDR. Consequently, the biological activity of VD signaling in VDR-expressing target cells depends on both circulating and locally synthesized 1,25(OH)₂D₃. This means that serum 25(OH)D levels—routinely used to assess VD status—do not directly reflect the magnitude of VD signaling within individual tissues. [

6]

VD is essential for the survival of most vertebrates. To ensure homeostasis, evolution has produced robust regulatory mechanisms that maintain circulating concentrations of active 1,25(OH)₂D₃ within narrow limits, despite wide fluctuations in precursor 25(OH)D levels. However, relatively little is known about the regulation of local 1,25(OH)₂D₃ synthesis within cardiovascular target cells. From a biological standpoint, the functional activity of VD signaling likely depends primarily on the local intracellular concentration of 1,25(OH)₂D₃, regardless of its systemic or regional origin. [

6]

Figure 2.

Vitamin D, metabolism, and genetic regulation. Two-step hydroxylation converts Vitamin D (VD) into its active hormonal form 1,25(OH)₂D₃. The VD–VDR complex regulates calcium and phosphate homeostasis. FGF23–Klotho signaling and SLC34A1-mediated phosphate transport modulate VD catabolism. Red circles: genes whose mutations cause rickets or autoimmune conditions; blue circles: mutations causing nephrolithiasis, hypercalcemia, or low PTH.

Adapted by Kristian Järvelin from Glenville Jones et al. [

7]

and Ulla Järvelin et al. [

8]

(Open Access, CC BY).

Figure 2.

Vitamin D, metabolism, and genetic regulation. Two-step hydroxylation converts Vitamin D (VD) into its active hormonal form 1,25(OH)₂D₃. The VD–VDR complex regulates calcium and phosphate homeostasis. FGF23–Klotho signaling and SLC34A1-mediated phosphate transport modulate VD catabolism. Red circles: genes whose mutations cause rickets or autoimmune conditions; blue circles: mutations causing nephrolithiasis, hypercalcemia, or low PTH.

Adapted by Kristian Järvelin from Glenville Jones et al. [

7]

and Ulla Järvelin et al. [

8]

(Open Access, CC BY).

3. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Diseases

VD exerts several regulatory effects on the cardiovascular system, mediated primarily through the VD receptor (VDR). In the heart, VDR expression has been demonstrated in both ventricular cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts. Additional studies have identified VDR expression in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells and in the endothelial lining of the rat aorta. Moreover, CYP27B1 expression has been detected in

vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), where it catalyzes the conversion of 25(OH)D₃ into the active metabolite 1,25(OH)₂D₃. [

6]

These findings indicate that cardiac and vascular tissues are not only responsive to VD but also capable of locally activating it. Indeed, in vitro studies have demonstrated local conversion of 25(OH)D₃ to 1,25(OH)₂D₃ in both endothelial cells and VSMCs, supporting the existence of an intrinsic VD signaling system within cardiovascular tissues. [

6]

Epidemiological evidence has consistently linked low serum 25(OH)D₃ levels with increased cardiovascular risk, including ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality [

9].

Despite these associations, large randomized controlled trials have generally failed to demonstrate a consistent cardiovascular benefit from VD supplementation. Landmark studies such as VITAL, ViDA, and DO-HEALTH, which employed long-term, high-dose VD regimens, did not show significant reductions in coronary events or cardiovascular mortality. [

10]

In addition, Mendelian randomization studies—designed to minimize residual confounding and reverse causation—have yielded null results on a causal link between VD status and cardiovascular disease [

11].

These discrepancies between observational and interventional data suggest that the cardiovascular effects of VD may not be uniform across all individuals.

Taken together, the current evidence underscores the need for a more refined approach to VD research in cardiovascular medicine. Rather than assuming a universal response to supplementation, future studies should focus on interindividual differences in VD sensitivity, metabolism, and genetic background. In particular, VD resistance and hypersensitivity may act as key modulators of cardiovascular outcomes, potentially explaining the heterogeneity observed across clinical trials and population studies.

4. Vitamin D Responsiveness Range

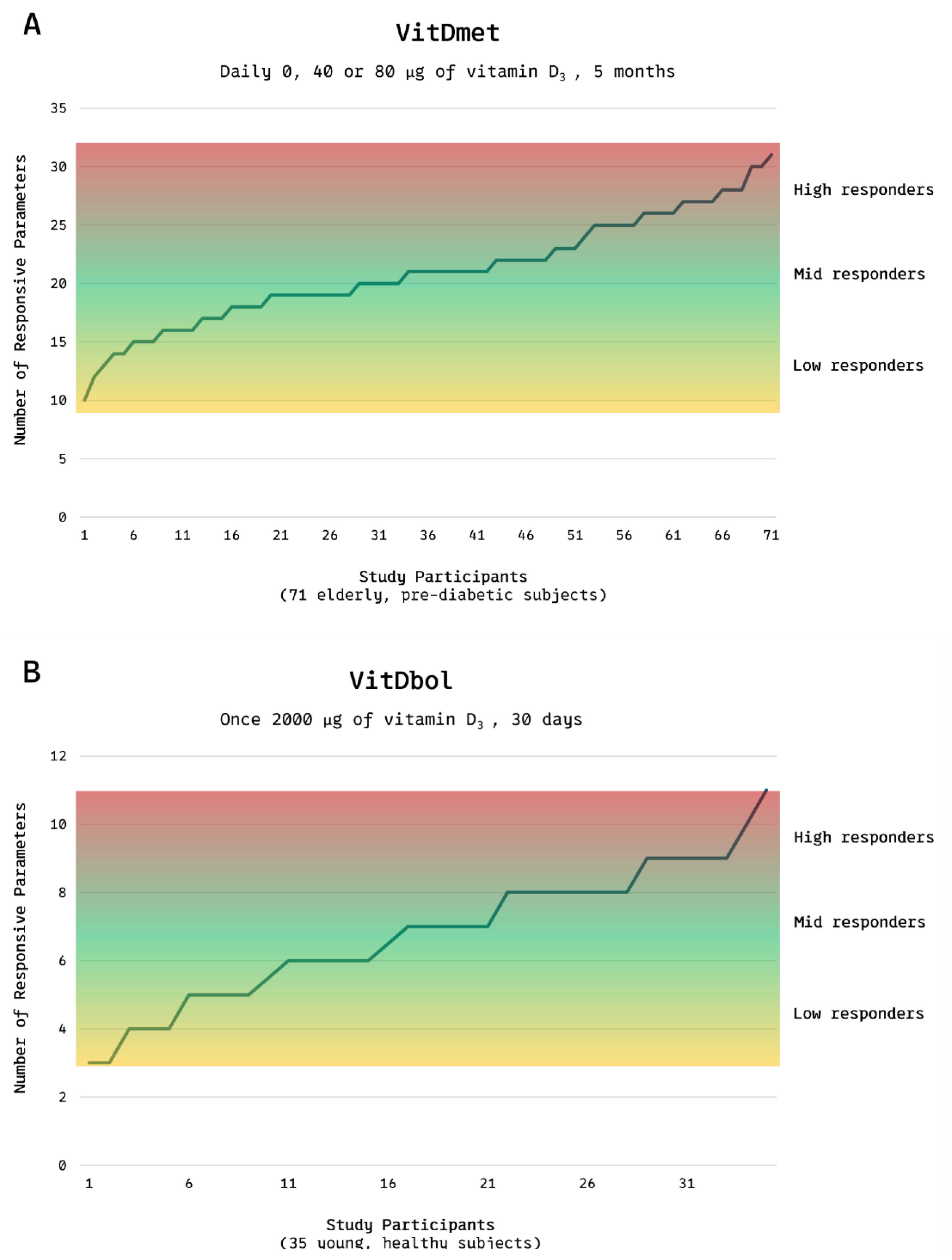

Research led by Carsten Carlberg and colleagues has revealed substantial interindividual variability in the physiological and molecular responses to VD supplementation. In the VitDmet study, conducted in Finland during the winter of 2015, 71 elderly participants with prediabetes received daily doses of 0, 1,600, or 3,200 IU of VD. The investigators monitored changes in the expression of 12 VD-responsive genes and several biochemical biomarkers. Remarkably, even at the highest dose, approximately 25% of participants showed minimal or no transcriptional or biochemical response, indicating low responsiveness to supplementation. Based on the magnitude of response, participants were categorized into low responders (24%), mid responders (51%), and high responders (25%) (

Figure 3A) [

12].

This classification was subsequently confirmed in the VitDbol study (2017) (

Figure 3B), in which healthy young adults received a single oral bolus of 80,000 IU VD [

13]. The distribution of responsiveness mirrored that observed in the earlier trial, suggesting that VD responsiveness is an intrinsic biological trait rather than a phenomenon primarily determined by age, metabolic status, or baseline VD levels.

Figure 3.

(A,B). Vitamin D responsiveness range. Distribution of low, mid, and high responders to vitamin D₃ supplementation in the VitDmet study (elderly, pre-diabetic subjects; 0, 1,600, or 3,200 IU daily for 5 months) and the VitDbol study (healthy adults; single 80,000 IU bolus). Roughly one quarter of participants showed minimal and one quarter maximal responses, despite identical VD intake.

Adapted from Carlberg C, Haq A. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018;175:12–17. © 2018 Elsevier. Adaptation by Kristian Järvelin. [

15].

Figure 3.

(A,B). Vitamin D responsiveness range. Distribution of low, mid, and high responders to vitamin D₃ supplementation in the VitDmet study (elderly, pre-diabetic subjects; 0, 1,600, or 3,200 IU daily for 5 months) and the VitDbol study (healthy adults; single 80,000 IU bolus). Roughly one quarter of participants showed minimal and one quarter maximal responses, despite identical VD intake.

Adapted from Carlberg C, Haq A. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018;175:12–17. © 2018 Elsevier. Adaptation by Kristian Järvelin. [

15].

5. Vitamin D Resistance (VDRES)

VD resistance (VDRES) represents the lower end of the responsiveness continuum, in which standard or even high doses of VD fail to elicit the expected physiological or molecular effects. This condition may arise from genetic or acquired defects that impair VD signaling. Mutations in the VDR can diminish receptor function, whereas alterations in CYP27A1 or CYP27B1 may interfere with VD synthesis. Such genetic abnormalities have been implicated in autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders, some of which may partially respond to high-dose VD protocols. [

14]

The phenomenon of VD resistance was first described in 1937 in children with rickets unresponsive to VD therapy. Subsequent studies identified hereditary defects in CYP27B1 or VDR as the cause of congenital VDRES—a rare disorder characterized by hypocalcemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and severe rickets. [

16]

More commonly, however, acquired VDRES develops over time due to environmental, metabolic, or immunological stressors. Viral infections such as

Epstein–Barr virus and

cytomegalovirus can disrupt VDR function, either through direct receptor interference or by downregulating VDR gene expression. Inflammatory mediators and caspase-3 have also been shown to inhibit VDR signaling. Moreover, glucocorticoid therapy can suppress VDR transcription and downstream gene activation. [

14]

Aging further exacerbates VD resistance by impairing multiple steps of VD metabolism. It decreases intestinal absorption of cholecalciferol, reduces cutaneous VD synthesis, and diminishes hepatic and renal hydroxylation efficiency. [

14]

Among these factors, the VDR itself appears to be the most vulnerable link in the pathway. Mutations and polymorphisms affecting VDR structure or expression have been associated with autoimmune diseases and with reduced VD signaling despite normal serum 25(OH)D levels. [

17]

In summary, individuals with VDRES either fail to activate VD efficiently or cannot utilize it effectively at the tissue level. In such cases, conventional supplementation may be inadequate, and personalized or high-dose regimens may be required to overcome receptor or enzymatic resistance.

6. Vitamin D Hypersensitivity (VDHY)

Compared with VDRES, VD hypersensitivity (VDHY) represents the opposite, less well-understood end of the VD responsiveness spectrum. In individuals with VDHY, either excess active VD accumulates in the body or target tissues exhibit heightened sensitivity to it. Consequently, physiological effects occur at VD exposures below average, and supplementation may be unnecessary—or even harmful. Under such conditions, regular sun exposure or standard therapeutic doses can lead to excessive calcium absorption, bone resorption, and hypercalcemia.

VDHY can be categorized into two etiological forms: exogenous and endogenous.

Exogenous VDHY results from excessive intake of pharmaceutical VD, often through prolonged or high-dose supplementation.

Endogenous VDHY, by contrast, involves an exaggerated biological response to normal or low levels of VD, driven by intrinsic metabolic or genetic abnormalities. [

18]

Historical accounts of endogenous VDHY date back over 70 years, beginning with children treated with high-dose vitamin D for rickets who developed hypercalcemia. These incidents were recorded in Great Britain during the early 1950s [

19], in Poland in the 1970s [

20], and in East Germany in the 1980s [

21]. In some cases, long-term moderate supplementation (around 500 IU per day) resulted in delayed toxicity, while a single large dose of 600,000 IU caused acute symptoms within days. Clinical signs included hypercalcemia, high cholesterol, heart murmurs, high blood pressure, neurological issues, and kidney problems. In the most severe cases, children died; autopsies showed extensive calcification in the heart muscle, valves, and blood vessels, with findings such as left ventricular hypertrophy and breakdown of arterial elastic tissue. [

22]

Contemporary research has shown that endogenous VDHY is multifactorial. One mechanism involves ectopic synthesis of 1,25(OH)₂D₃ in granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, lymphomas, and certain fungal infections [

18]. During pregnancy, the placenta can also produce 1,25(OH)₂D₃ [

23]. Another important mechanism is genetic mutation affecting VD metabolism—particularly in CYP24A1 and SLC34A1—which disrupts the degradation or regulation of active VD. Besides, other, as yet unknown, mutations affecting VD metabolism have been identified [

24]. These mutations cause accumulation of 1,25(OH)₂D₃ and persistent hypercalcemia, even under modest sunlight exposure or prophylactic supplementation. Such inherited defects may present as idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia in neonates or remain subclinical until triggered by environmental factors. [

18]

The so-called “gene-dose effect” is well established. Individuals with biallelic mutations typically develop severe, early-onset disease characterized by hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, vascular calcification, suppressed PTH levels, and hypercalciuria. In contrast, monoallelic mutation carriers may remain asymptomatic unless exposed to physiological or environmental triggers such as pregnancy, high-dose VD supplementation, or prolonged sun exposure. In such individuals, even standard VD prophylaxis can precipitate toxicity. [

25]

Importantly, VDHY may persist into adulthood, particularly in monoallelic mutation carriers. These individuals constitute a genetic risk group who may appear healthy until exposed to otherwise safe levels of VD. This underscores the importance of tailoring VD dosing and monitoring based on individual metabolic sensitivity.

7. Cholesterol Metabolism and CYP24A1 Mutation

Beyond its well-established role in calcium and phosphate homeostasis, VD metabolism appears to intersect with lipid regulation—an emerging and underexplored field. Notably, patients carrying CYP24A1 mutations, which impair the catabolism of 1,25(OH)₂D₃, have occasionally been reported to exhibit abnormalities in lipid metabolism, including hypercholesterolemia. Historical case reports of idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia also documented a co-occurrence of hypercholesterolemia and vascular lesions [

22]. These observations raise the intriguing possibility that dysregulated VD signaling may disturb cholesterol homeostasis through metabolic cross-talk or feedback mechanisms.

To explore this hypothesis, researchers developed transgenic rats that constitutively overexpressed the CYP24A1 gene. These animals displayed markedly reduced circulating levels of 24,25(OH)₂D₃, reflecting enhanced catabolic activity. Interestingly, after weaning, the rats developed albuminuria and hyperlipidemia, with lipid profiling revealing elevations across all lipoprotein fractions. Histological analysis demonstrated atherosclerotic changes in the aorta, which were further aggravated by a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet. [

26] Despite producing opposite biochemical effects on vitamin D turnover, both CYP24A1 overexpression and loss-of-function mutations disrupt the homeostatic balance of vitamin D metabolites. This disruption, rather than the direction of the metabolic shift itself, may underlie the lipid and vascular abnormalities observed in both settings. From a biochemical perspective, 7-dehydrocholesterol (7DHC) occupies a pivotal position as a shared precursor for both cholesterol and VD synthesis. In the skin, 7DHC undergoes photochemical conversion to pre-vitamin D₃ under UVB radiation. [

3] This dual role makes it a potential site of metabolic competition or feedback regulation between VD and cholesterol biosynthetic pathways. Excessive 1,25(OH)₂D₃—whether due to ectopic production or impaired degradation secondary to CYP24A1 mutations—could alter substrate flux or modulate gene expression, thereby shifting the balance between these pathways. The enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) catalyzes the reduction of 7DHC to cholesterol, representing a possible regulatory “switch”. Experimental evidence supports a reciprocal relationship between these pathways. DHCR7 activity decreases when intracellular cholesterol accumulates, accelerating DHCR7 degradation via end-product inhibition and consequently redirecting 7DHC toward VD synthesis. [

27]

In keratinocyte models, cholecalciferol rapidly suppressed DHCR7 activity without increasing 7DHC accumulation, whereas 25(OH)D₃ caused only mild suppression, and 1,25(OH)₂D₃ showed no effect—suggesting that this feedback occurs independently of VDR-mediated transcription [

28].

Collectively, these findings position DHCR7 as a potential regulatory node linking VD and cholesterol metabolism. The complex interplay between these pathways warrants further investigation, particularly under conditions of VD hypersensitivity (VDHY), where excessive active VD could perturb lipid homeostasis and contribute to hypercholesterolemia or vascular pathology.

8. Vascular Calcification and CYP24A1 Mutation

Mutations in the CYP24A1 gene, which impair the degradation of active VD metabolites, have been implicated not only in systemic hypercalcemia but also in vascular pathology. Elevated levels of 1,25(OH)₂D₃ and hypercalcemia can lead to cardiovascular complications. Both acute and chronic hypercalcemia increase blood pressure primarily through direct effects on VSMC contractility [

29]. Hypercalcemia can also lead to arterial vasoconstriction [

30] and arterial and coronary calcification [

31]. Recent genetic studies have reported associations between

CYP24A1 variants and an increased burden of coronary artery calcification in independent populations [

32,

33], suggesting – but not yet proving - a causal role of dysregulated VD metabolism in coronary atherosclerosis. This link is clinically relevant because coronary artery calcification is a well-established predictor of coronary heart disease and future cardiovascular events [

34].

Although serum 25(OH)D₃ is commonly used as a biomarker of VD status, it is the active metabolite 1,25(OH)₂D₃ that mediates the most potent biological effects. Importantly, circulating 25(OH)D₃ levels may not accurately reflect tissue-specific VD activity, particularly under pathological conditions. In vascular tissues, extra-renal synthesis of 1,25(OH)₂D₃ can occur via CYP27B1 activity in endothelial and immune cells. This local synthesis plays a direct role in atherosclerosis and plaque calcification, functioning independently of systemic VD concentrations. [

35]

The atherosclerotic plaque microenvironment provides an optimal setting for such “non-classical” VD activity. Within the plaque, the full complement of enzymes required for VD and VDR activation is expressed, enabling intracrine, autocrine, and paracrine signaling. Under certain conditions—such as

CYP24A1 mutations or ectopic VD synthesis—local VD metabolism becomes dysregulated, leading to elevated intraplaque 1,25(OH)₂D₃ concentrations that may remain undetectable in serum but promote vascular injury. [

6,

35]

Vascular calcification, especially within atherosclerotic lesions, is now recognized as an active, regulated process that closely resembles osteogenesis. In animal models, calcified plaques contain bone-associated morphogens and matrix proteins such as osteopontin (OPN), osteonectin, and osteocalcin, reflecting a shared osteogenic phenotype. In vitro studies using vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) have shown that alkaline phosphatase (ALP) mediates vascular mineralization and that OPN is implicated in this process. [

37] Calcium-regulating hormones further modulate this process. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) inhibits vascular calcification by downregulating ALP activity [

38], whereas 1,25(OH)₂D₃ stimulates calcium influx [

39], modulates VSMC growth [

40], and reduces PTHrP expression [

36,

37,

38], thereby removing a natural brake on mineral deposition. Excess VD—whether due to high dietary intake, ectopic VD synthesis, or impaired catabolism—has been shown to induce vascular calcification in both animal models and cell culture systems [

41,

42,

43].

Taken together, these findings support the view that CYP24A1 mutations or ectopic VD synthesis may promote vascular calcification by sustaining elevated local 1,25(OH)₂D₃ levels and suppressing PTHrP-mediated inhibition, thereby contributing to the formation of unstable, calcified atherosclerotic plaques

9. Prevalence of VDRES and VDHY and Their Epidemiological Context

According to limited population data from Carlberg and colleagues, approximately 50% of individuals display normal VD responsiveness, 25% exhibit low responsiveness (VDRES), and 25% exhibit high responsiveness (VDHY) [

12,

13]. Inherited VDRES, resulting from mutations or defects in the

VDR gene or in enzymes responsible for VD synthesis and activation, is rare. In contrast, acquired VDRES appears more common and has been associated with autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammatory diseases. It is estimated that roughly 10% of the world’s population is affected by autoimmune diseases, and the burden of autoimmune diseases is growing. [

44] Acquired VDRES likely arises from epigenetic modifications or somatic mutations that occur with aging or environmental exposures, leading to impaired VD signaling [

8,

14].

Inherited VDHY is also uncommon. In a Polish population study, biallelic variants in

CYP24A1 and

SLC34A1 were identified in approximately 1 in 32,465 births [

20]. Notably,

biallelic CYP24A1 abnormalities have been reported in 4–20% of patients with calcium nephrolithiasis [

45]. Moreover, granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis can lead to VDHY by ectopic production of 1,25(OH)₂D₃. The incidence of sarcoidosis varies widely by region, from 1–5 cases per 100,000 in East Asia (South Korea, Japan, Taiwan) to 140–160 cases per 100,000 in northern countries such as Sweden and Canada [

46]. From a cardiovascular perspective, granulomatous diseases like sarcoidosis [

48] and tuberculosis [

49] have been associated with increased coronary artery calcification, and genetic variants in CYP24A1 have been linked to a greater coronary artery calcification burden across multiple populations [

32,

33].

VDHY may first present in adulthood, particularly in monoallelic carriers, and can be triggered by high sun exposure, VD–rich diets, or supplementation. In such cases, increased 1,25(OH)₂D₃ synthesis can lead to hypercalcemia and vascular calcification even at otherwise safe exposure levels [

18].

Despite these emerging observations, the true global prevalence of both VDRES and VDHY remains unknown, underscoring the need for large-scale, ethnically diverse studies to define their distribution and clinical significance.

10. Future Research

Emerging data suggest that up to half of individuals may display altered responsiveness to VD, ranging from heightened sensitivity to relative resistance. However, these estimates are based on small, largely homogeneous study populations. To clarify the true prevalence and public health implications, larger, multiethnic cohort studies are required.

Further in vitro and in vivo research should explore how VD—especially in excess—impacts PTHrP expression and vascular calcification. Additionally, the observed link between CYP24A1 dysfunction and cholesterol metabolism calls for more detailed mechanistic studies, ideally combining transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling. An in vivo study could also compare VD sensitivity between two populations: one with hypercholesterolemia and another with normal cholesterol levels.

Ultimately, developing a clinical assay to quantify individual VD responsiveness would enable safer and more effective supplementation strategies. Such a tool could help clinicians identify those at risk for either inadequate response or toxicity, thereby minimizing adverse outcomes such as atherosclerosis, hypercalcemia, or hypercholesterolemia.

11. Discussion

VD exerts a broad spectrum of biological actions that extend far beyond its classical role in mineral metabolism. It modulates inflammation, immune regulation, and vascular integrity. This review emphasizes that interindividual variability in VD responsiveness—arising from genetic variation, environmental exposure, or comorbid disease—represents a critical but underrecognized determinant of cardiovascular outcomes.

In VDRES, impaired responsiveness may sustain chronic inflammation, autoimmune activation, and vascular dysfunction. In contrast, VDHY—whether due to CYP24A1 mutations, ectopic synthesis, or defective catabolism—can promote pathological vascular calcification even under ordinary supplementation or sunlight exposure.

Importantly, serum 25(OH)D concentrations do not necessarily reflect actual VD activity at the tissue level. This is particularly relevant in VSMCs and macrophages, which can locally synthesize 1,25(OH)₂D₃ via CYP27B1. Dysregulated VD metabolism within these cells may directly contribute to vascular mineralization and also affect cholesterol biosynthesis, given the shared metabolic intermediates between the VD and sterol pathways.

Taken together, these findings challenge the traditional concept of a universal “optimal” VD threshold. They support a shift toward personalized VD therapy, guided by molecular diagnostics, genetic screening, and patient-specific metabolic profiling.

12. Conclusions

VD supplementation is neither universally beneficial nor inherently harmful. The cardiovascular impact of VD supplementation depends on individual biological responsiveness. In VDRES, supplementation may help restore immune and vascular balance. In VDHY, even modest doses may provoke hypercalcemia, vascular calcification, or lipid disturbances. Recognizing and quantifying these divergent responses will be essential for optimizing VD use in cardiovascular prevention and therapy.

Table 1.

Key differences between vitamin D resistance (VDRES) and vitamin D hypersensitivity (VDHY). The table summarizes etiological, diagnostic, and clinical distinctions, along with associated diseases and therapeutic considerations, derived from published studies.

Table 1.

Key differences between vitamin D resistance (VDRES) and vitamin D hypersensitivity (VDHY). The table summarizes etiological, diagnostic, and clinical distinctions, along with associated diseases and therapeutic considerations, derived from published studies.

| |

Vitamin D resistance (VDRES) |

Vitamin D hypersensitivity (VDHY) |

| Etiology |

Mutations in genes involved in VD signaling (VDR), synthesis (CYP27A1, CYP2R1, CYP27B1), or transport (vitamin D-binding protein, DBP). Environmental factors such as pathogens, glucocorticoids, toxins, aging, or insufficient sunlight exposure. [14] |

Inactivating mutations of CYP24A1 and SLC34A1 [18], or mutations in yet-unknown genes affecting VD catabolism [24], granulomatous diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis, tuberculosis) or lymphomas [18]; pregnancy [47]; excessive VD intake (exogenous VD hypersensitivity) [18] |

| Diagnosis / Laboratory findings |

Elevated PTH; normal or low 25(OH)D₃ and calcium [14] |

Depressed PTH; hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria. Increased 25(OH)D₃ → exogenous hypersensitivity; increased 1,25(OH)₂D₃ → endogenous hypersensitivity. |

| 25(OH)D₃:24,25(OH)₂D₃ ratio > 80 (normal < 30). Genetic confirmation (CYP24A1, SLC34A1). [18] |

| Associated diseases |

Autoimmune disorders, rickets [14] |

Hypercalcemia of pregnancy [47], calcifications in the vascular system [32] and kidneys [18], leading to atherosclerosis, nephrolithiasis, and pregnancy complications |

| Therapeutic approach |

High-dose VD supplementation (under close monitoring). [14] |

Discontinuation of VD supplementation and avoidance of excessive sunlight. Hydration [18] |

| Low-calcium diet, Azole drugs [18] |

| Prevalence |

Unknown [14] |

Unknown [18]. |

Author Contributions

Sole author; all sections of the manuscript were prepared independently.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

During the preparation of this work, the author used AI to write the text and collect data. AI-assisted tools were also used for schematic figure generation, not for data analysis or result interpretation. After using these tools, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Acknowledgments

Kristian Järvelin: IT support, Figures, Table.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CVD, |

cardiovascular disease |

| CYP27B1 |

1-hydroxylase |

| CYP24A1 |

, 24-hydroxylase |

| PTH |

Parathyroid hormone |

| 7DHC |

7-dehydrocholesterol |

| VD |

Vitamin D |

| VDHY |

Vitamin D hypersensitivity |

| VDR |

Vitamin D receptor |

| VDRES |

Vitamin D resistance |

| VSMC |

Vascular smooth muscle cell |

References

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J.R.; Alloza, I.; Vandenbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virmani, R.; Burke, A.P.; Farb, A.; Kolodgie, F.D. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C13–C18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; David, V.; Quarles, L.D. Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D.; Patzek, S.; Wang, Y. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of extrarenal CYP27B1: Case report and review. Bone Rep. 2018, 8, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latic, N.; Erben, R.G. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease, with emphasis on hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. 100 years of vitamin D: Historical aspects of vitamin D. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelin, U.M.; Järvelin, J.M. Significance of vitamin D responsiveness on the etiology of vitamin D-related diseases. Steroids 2024, 207, 109437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brøndum-Jacobsen, P.; Benn, M.; Jensen, G.B.; Nordestgaard, B.G. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and early death: Population-based study and meta-analyses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 2794–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Manousaki, D.; Rosen, C.; Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F.; Richards, J.B. The health effects of vitamin D supplementation: Evidence from human studies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; LeBoff, M.S.; Neale, R.E. Health effects of vitamin D supplementation: Lessons learned from randomized controlled trials and Mendelian randomization studies. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2023, 38, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksa, N.; Neme, A.; Ryynänen, J.; Uusitupa, M.; de Mello, V.D.; Voutilainen, S.; et al. Dissecting high from low responders in a vitamin D3 intervention study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 148, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuter, S.; Virtanen, J.K.; Nurmi, T.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Mursu, J.; Voutilainen, S.; et al. Molecular evaluation of vitamin D responsiveness of healthy young adults. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 174, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, D.; Klement, R.J.; Schweiger, F.; Schweiger, B.; Spitz, J. Vitamin D resistance as a possible cause of autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 655739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C.; Haq, A. The concept of the personal vitamin D response index. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, F.; Butler, A.M.; Bloomberg, E. Rickets resistant to vitamin D therapy. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1937, 54, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliardi, C.; Guerini, F.R.; Bolognesi, E.; Zanzottera, M.; Clerici, M. VDR gene SNPs and autoimmunity: A narrative review. Biology 2023, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebben, P.J.; Singh, R.J.; Kumar, R. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia: Mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, H.S. Infantile hypercalcaemia, nutritional rickets, and infantile scurvy in Great Britain. Br. Med. J. 1964, 1, 1659–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronicka, E.; Ciara, E.; Halat, P.; Janiec, A.; Wójcik, M.; Rowińska, E. Biallelic mutations in CYP24A1 or SLC34A1 in infantile idiopathic hypercalcemia. J. Appl. Genet. 2017, 58, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misselwitz, J.; Hesse, V.; Markestad, T. Nephrocalcinosis, hypercalciuria and high 1,25(OH)2D in children. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1990, 79, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.N.; Schlesinger, B.E.; et al. Infantile hypercalcemia and cardiovascular lesions. Arch. Dis. Child. 1965, 40, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Cohen, W.R.; Silva, P.; Epstein, F.H. Elevated 1,25(OH)2D in pregnancy and lactation. J. Clin. Invest. 1979, 63, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, E.; Levi, S.; Borovitz, Y.; Alfandary, H.; Ganon, L.; Dinour, D.; et al. Childhood hypercalciuric hypercalcemia with elevated vitamin D. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 752312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, D.T.; Tebben, P.J.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R.J.; Wu, Y.; Wermers, R.A. CYP24A1 mutations: Evidence of gene dose effect. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 3121–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, H.; Hosogane, N.; Matsuoka, K.; Mori, I.; Sakura, Y.; Shimakawa, K.; et al. Transgenic rats expressing vitamin D-24-hydroxylase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 297, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, A.V.; Luu, W.; Sharpe, L.J.; Brown, A.J. Cholesterol-mediated degradation of 7-DHC reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 8363–8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Porter, T.D. Suppression of 7-DHC reductase by vitamin D. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 148, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campese, V.M. Calcium, parathyroid hormone, and blood pressure. Am. J. Hypertens. 1989, 2, 34S–44S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-H.; Huang, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-F.; Chen, W.-H.; Lai, S.-L. Hypercalcemia-induced seizures via vasoconstriction. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, T.; Takemoto, Y.; Uchida, J.; Nakatani, T.; Kabata, D.; Shintani, A. Hypercalcemia and aortic calcification progression. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2019, 44, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Bielak, L.F.; Ferguson, J.F.; Streeten, E.A.; Yerges-Armstrong, L.M.; Liu, J.; et al. CYP24A1 and coronary artery calcification. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 2648–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, P.; Cao, X.; Xu, X.; Duan, M.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, G. CYP24A1 variants in coronary heart disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detrano, R.; Guerci, A.D.; Carr, J.J.; Bild, D.E.; Burke, G.; Folsom, A.R.; Liu, K.; Shea, S.; Szklo, M.; Bluemke, D.A.; O’Leary, D.H.; Tracy, R.; Watson, K.; Wong, N.D.; Kronmal, R.A. Coronary calcium predicting events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Liberale, L.; Libby, P.; Montecucco, F. Vitamin D in atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2078–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jono, S.; Nishizawa, Y.; Shioi, A.; Morii, H. Vitamin D and vascular calcification. Circulation 1998, 98, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shioi, A.; Nishizawa, Y.; Jono, S.; Koyama, H.; Hosoi, M.; Morii, H. β-glycerophosphate and vascular calcification. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1995, 15, 2003–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jono, S.; Nishizawa, Y.; Shioi, A.; Morii, H. PTHrP in vascular calcification regulation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Kawashima, H. Vitamin D–stimulated Ca2+ uptake in VSMCs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 152, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthy, E.P.; Yamashita, W.; Hsu, A.; Ooi, B.S. Vitamin D and VSMC growth. Hypertension 1989, 13, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, G.S.; Morrison, L.M.; Ershoff, B.H. Hypervitaminosis D and atherosclerosis in rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 1971, 138, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, T.G.; Jacobson, N.L.; Beitz, D.C.; Littledike, E.T. Calcium, vitamin D and atherosclerosis in goats. J. Nutr. 1985, 115, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederhoffer, N.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Lartaud-Idjouadiene, I.; Giummelly, P.; Atkinson, J. Aortic calcification from vitamin D3 plus nicotine. J. Vasc. Res. 1997, 34, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, N.; Misra, S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G.; Taylor, P.N.; Mason, J.; McMurray, J.J.V.; McInnes, I.B.; Khunti, K.; Cambridge, G. Autoimmune disorders incidence and co-occurrence. Lancet 2023, 401, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterova, G.; Malicdan, M.C.; Yasuda, K.; Sakaki, T.; Vilboux, T.; Ciccone, C.; Horst, R.; Huang, Y.; Golas, G.; Introne, W.; Huizing, M.; David Adams, D.; Boerkoel, C.F.; Collins, M.T.; Gahl, W.A. CYP24A1 deficiency and nephrolithiasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkema, E.V.; Cozier, Y.C. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: Incidence, prevalence, risk factors. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; Theiler-Schwetz, V.; Pludowski, P.; Zelzer, S.; Meinitzer, A.; Karras, S.N.; Misiorowski, W.; Zittermann, A.; März, W.; Trummer, T. Hypercalcemia in pregnancy due to CYP24A1 mutations. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, C.; Drent, M.; Nunes, H.; Kouranos, V.; Cinetto, F.; Jessurun, N.T.; Spagnolo, P. Comorbidities of sarcoidosis. Ann Med. 2022, 54(1), 1014–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefuye, M.A.; Manjunatha, N.; Ganduri, V.; Rajasekaran, K.; Duraiyarasan, S.; Adefuye, B.O. Tuberculosis and Cardiovascular Complications: An Overview. Cureus 2022, 14(8), E28268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |