1. Introduction

The emergence of quantum computing poses a material risk of cryptographic compromise to current public-key cryptographic systems. Shor’s algorithm [

26] enables polynomial-time attacks on integer factorization and discrete logarithms, rendering RSA, elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), and finite-field Diffie-Hellman vulnerable. This threat has driven U.S. Government direction—through NSM-10 [

6] and OMB M-23-02 [

12]—to inventory and migrate vulnerable cryptography toward post-quantum standards. Broken or risky cryptography is also a recognized weakness class [

1]. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) finalized its first post-quantum cryptography standards in August 2024, including ML-KEM for key encapsulation and ML-DSA for digital signatures [

20,

21,

22]. International guidance from ENISA [

4], CISA [

14], the UK NCSC [

15], ETSI [

16], and the EU NIS 2 Directive [

35] reinforces the urgency of PQC migration. However, the transition from current cryptographic algorithms to quantum-resistant alternatives requires organizations to first understand their existing cryptographic posture—a process known as Cryptographic Asset Discovery and Inventory (CADI).

Recent market analyses, including the TNO report commissioned by the Dutch government [

5], have established frameworks for CADI tooling evaluation in enterprise IT environments. These frameworks address network scanning, application analysis, and certificate enumeration with reasonable effectiveness for conventional computing infrastructure. However, the TNO report explicitly acknowledges that operational technology (OT)—as defined in NIST SP 800-82 [

3]—represents a significant gap (i.e., a “blind spot”) where none of the interviewed CADI providers had meaningful experience, and one provider indicated no commercial interest in addressing this domain.

This gap is particularly consequential for defense applications. The Department of Defense (DoD) operates extensive embedded system deployments across weapons platforms, tactical communications, command and control systems, and critical infrastructure. NSM-10 directs action to mitigate quantum risk to vulnerable cryptographic systems [

6], and OMB M-23-02 establishes concrete agency planning and inventory timelines [

12], yet the foundational discovery capability required to scope this migration remains underdeveloped for embedded environments. The collision between quantum-risk timelines (often framed as within 10–15 years) and the decade-scale lifecycle of major embedded platforms creates urgency for inventory, prioritization, and migration planning now [

11].

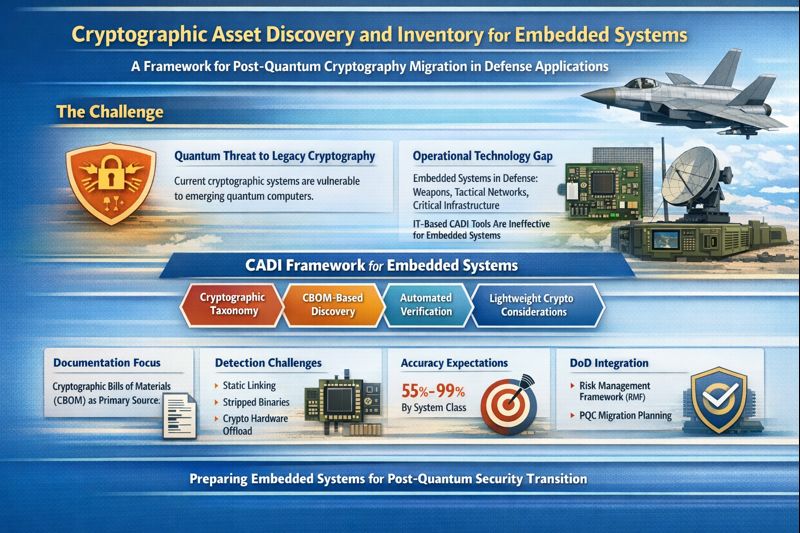

This paper addresses this gap by presenting a comprehensive framework for embedded systems-specific CADI. We establish why IT-centric approaches are largely ineffective for embedded systems, propose a taxonomy of embedded system classes based on cryptographic characteristics and discovery feasibility, detail detection methodologies appropriate to each class, address lightweight cryptography considerations for constrained devices, examine lifecycle and certification constraints, establish realistic accuracy expectations, and provide integration guidance for DoD Risk Management Framework (RMF) processes and PQC migration planning.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards

Cryptographic agility is the capability to replace and adapt cryptographic algorithms across protocols, applications, software, hardware, firmware, and operational infrastructures while preserving security and continuity of operations [

2]. NIST finalized its first three post-quantum cryptography (PQC) standards—FIPS 203 (ML-KEM), FIPS 204 (ML-DSA), and FIPS 205 (SLH-DSA)—on 13 August 2024, establishing the initial standardized baseline for quantum-resistant key establishment and digital signatures [

20,

21,

22,

28]. A fourth standard, FIPS 206 (FN-DSA, derived from FALCON), remains under development [

25]. In March 2025, NIST selected Hamming Quasi-Cyclic (HQC) as a diversity backup for key encapsulation [

13], providing a code-based alternative to the lattice-based ML-KEM and demonstrating the government’s commitment to algorithmic diversity as a hedge against potential mathematical breakthroughs. However, HQC keys and ciphertexts are generally larger than ML-KEM equivalents [

13], further constraining deployment options for resource-limited embedded systems. Reference implementations of these algorithms are available through the Open Quantum Safe project [

7].

While these finalized algorithms provide standardized quantum-resistant primitives, their deployment in embedded systems is frequently constrained by artifact size (public keys, ciphertexts, and signatures), compute cost, memory footprint, and interoperability/encoding overhead (e.g., certificate and update-package encapsulations) [

20,

21,

22]. These constraints directly motivate the need for accurate cryptographic asset discovery and inventory (CADI) and crypto-agile planning, so systems can prioritize where PQC migration is feasible, where hybrid mechanisms are required, and where architectural mitigations are necessary [

2,

5,

8,

12,

14,

15,

16].

2.2. Existing CADI Frameworks and Their Limitations

The TNO report [

5] establishes requirements for CADI tooling, including scanning frequency, deployment location, agent utilization, CBOM import capability, logging, scope, accuracy, and integration. The report proposes an effort-accuracy model with nine levels ranging from reusing existing security tool information to performing static firmware analysis. Based on the TNO qualitative maturity levels, we derive indicative planning targets of

accuracy for an ideal tool and

for a minimum viable product (MVP) in IT environments; these figures represent our interpretation for planning purposes rather than explicit TNO quantitative findings.

However, the TNO report’s treatment of embedded systems is limited to acknowledging their existence as a challenge. The report notes that OT environments may have extraordinarily limited computational power and memory; that agent deployment may be difficult due to intellectual property restrictions and operational constraints; that legacy systems predominate with varied protocols and cryptography; and that active cryptographic asset detection may be impractical in many OT settings. None of the three CADI providers interviewed had experience in the OT domain, and one explicitly stated that OT was not part of their objectives due to insufficient commercial incentive.

NIST Interagency Report (IR) 8547 [

8] provides draft guidance for migration to post-quantum cryptography in enterprise environments, including discovery considerations. However, this enterprise-focused guidance does not address embedded systems or provide National Security Systems (NSS) governance direction, limiting its direct applicability to defense applications.

3. Fundamental Constraints of Embedded Systems

Before proposing detection methodologies, it is essential to understand why IT-centric CADI approaches encounter systemic barriers in embedded systems. These constraints are not merely quantitative differences but represent qualitative barriers that require substantially different discovery paradigms.

3.1. Resource Constraints

Enterprise IT systems operate with gigabytes of RAM and multi-gigahertz processors; embedded systems often operate with kilobytes of RAM and megahertz-class processors.

Table 1 illustrates representative resource profiles across embedded system classes.

CADI agents require memory allocation for code execution, buffer space for scan results, and CPU cycles for cryptographic artifact analysis. Even “lightweight” agents typically require tens of megabytes of RAM once runtime, buffers, and telemetry queues are included. For systems with 1 MB total RAM operating under real-time constraints, agent deployment is infeasible—available memory is insufficient for agent overhead.

3.2. The Availability Imperative

Enterprise IT security prioritizes the CIA triad in order: Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability. Embedded systems, particularly in defense and industrial contexts, invert this priority: Availability dominates, followed by Integrity, with Confidentiality often a distant third. A fire control system that experiences a 100-millisecond latency spike during cryptographic scanning may miss an engagement window. A power grid controller that pauses for inventory analysis may cause cascading failures.

This availability imperative has profound implications for CADI. Active scanning techniques that inject test traffic or probe endpoints are frequently prohibited—not merely undesirable but explicitly forbidden by operational policy. Network-connected industrial systems often operate on “air-gapped” networks where any unauthorized traffic triggers safety interlocks. Weapons systems undergo extensive electromagnetic compatibility testing; introducing scanning traffic may violate type certification.

The TNO report’s recommendation for “continuous passive and active scanning” assumes availability can be temporarily degraded for security visibility. For embedded systems controlling physical processes, this assumption is often invalid.

3.3. Certification and Modification Constraints

Safety-critical embedded systems undergo rigorous certification processes that constrain post-deployment modification.

Table 2 summarizes relevant certification frameworks [

17,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] and their implications for CADI.

Installing a CADI agent on a DO-178C DAL-A certified flight control computer would invalidate its certification, requiring extensive reverification—a process measured in years and millions of dollars. Even passive monitoring may be prohibited if it requires any software modification to enable traffic mirroring. These constraints are not bureaucratic obstacles but reflect genuine safety considerations: the certification process validates that the software behaves deterministically under all conditions, and any modification invalidates that validation.

3.4. Architectural Barriers to Detection

Even when resource and certification constraints permit scanning, architectural characteristics of embedded systems defeat standard detection techniques:

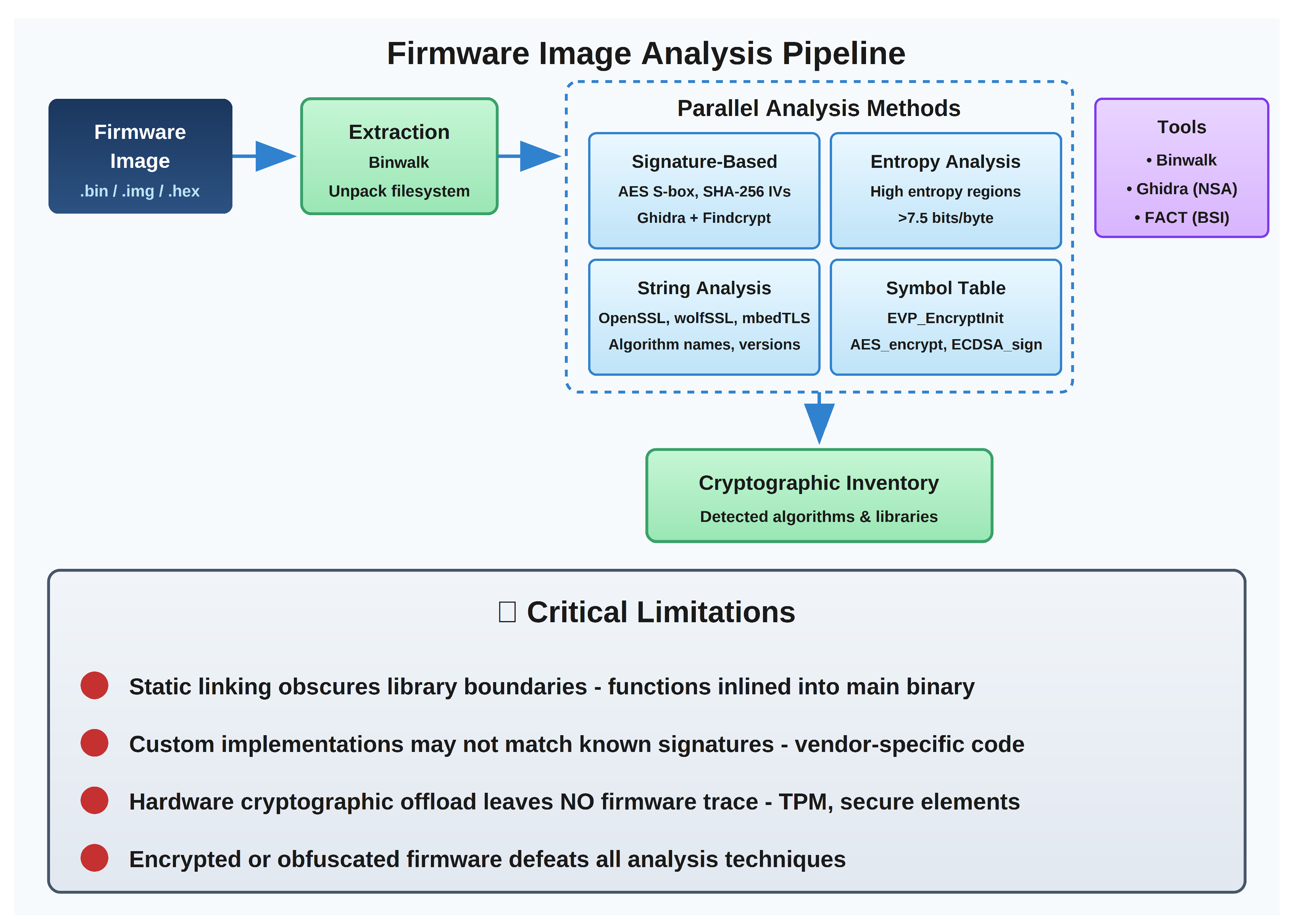

Static Linking: IT applications typically dynamically link cryptographic libraries, creating identifiable library calls that CADI tools intercept. Embedded systems frequently statically link cryptographic code directly into monolithic binaries, eliminating the library boundary signatures that detection tools rely upon.

Stripped Binaries: Production embedded firmware typically has symbol tables removed to reduce size and protect intellectual property. Without symbols, function identification requires pattern matching against known cryptographic constants, a technique with high false-positive rates and an inability to detect custom implementations.

Hardware Cryptographic Offload: Many embedded systems delegate cryptographic operations to dedicated hardware: secure elements, TPMs, cryptographic accelerators, or purpose-built ASICs. When AES encryption occurs in a hardware accelerator, no software trace exists for CADI tools to detect. The main processor simply writes plaintext to a memory-mapped register and reads ciphertext from another.

Proprietary RTOS Environments: Commercial CADI tools assume Linux or Windows execution environments with standardized cryptographic interfaces such as the W3C Web Cryptography API [

18]. Embedded systems run VxWorks, QNX, INTEGRITY, ThreadX, FreeRTOS, or bare-metal configurations with substantially different memory models, system call interfaces, and execution patterns.

Proprietary Implementations: Vendors frequently implement cryptographic primitives without using standard libraries, either for performance optimization, size reduction, or intellectual property differentiation. A custom AES implementation may not contain the standard S-box lookup table that signature-based detection relies upon.

These barriers are not edge cases but the norm for embedded systems. The assumption that cryptographic implementations can be detected through software analysis is valid for IT environments where standardized libraries predominate; it fails systematically for embedded systems.

For Class E and Class F systems where cryptography is implemented in ASICs or burned into FPGAs to meet size, weight, and power (SWaP) constraints, “crypto agility” is a misnomer—algorithm updates require hardware recapitalization, not software patches. The PQC transition will therefore trigger a hardware replacement cycle for these classes, with cost implications orders of magnitude higher than software updates. CADI must identify not only which algorithms are in use but whether implementations are software-updatable or hardware-bound; this distinction fundamentally determines remediation cost and timeline.

3.5. Migration Failure Modes from Incomplete Discovery

Beyond the technical challenges of cryptographic discovery, incomplete or inaccurate inventory creates substantial operational risk during PQC migration execution. Defense embedded systems operate within complex interdependency networks where cryptographic compatibility failures can cascade across platforms, communications links, and command hierarchies. Key failure modes include:

Protocol Version Mismatch Cascades: Consider a tactical communications network where ground stations migrate to ML-KEM for key encapsulation while airborne platforms remain on ECDH due to certification constraints. If protocol negotiation fails to establish a common algorithm, the key exchange fails entirely, creating fragmented communication enclaves.

Certificate Chain Validation Failures: If a root CA migrates to ML-DSA signatures while subordinate CAs or end-entity certificates remain on ECDSA, signature validation fails across the trust hierarchy.

Hardware Cryptographic Boundary Incompatibilities: Key fill devices (DS-101, DS-102 interfaces) that cannot load ML-KEM or ML-DSA keys render endpoint PQC support operationally useless.

Bandwidth and Timing Constraint Violations: ML-KEM-768 public keys (1,184 bytes) are 18 times larger than P-256 ECDH keys (64 bytes). Real-time systems with deterministic timing requirements may miss deadlines during signature verification.

For mission-critical systems where a single uncoordinated migration can cascade into network-wide communication failure, discovery accuracy is not merely a compliance metric but an operational safety requirement.

4. Embedded System Classification for CADI

Given the fundamental constraints established in

Section 3, we propose a six-class taxonomy for DoD-relevant embedded systems based on cryptographic characteristics and discovery feasibility. Unlike the TNO report’s monolithic “OT” category, this classification enables targeted detection methodology selection.

4.1. Classification Taxonomy

Table 3 defines the embedded system classes used throughout this framework.

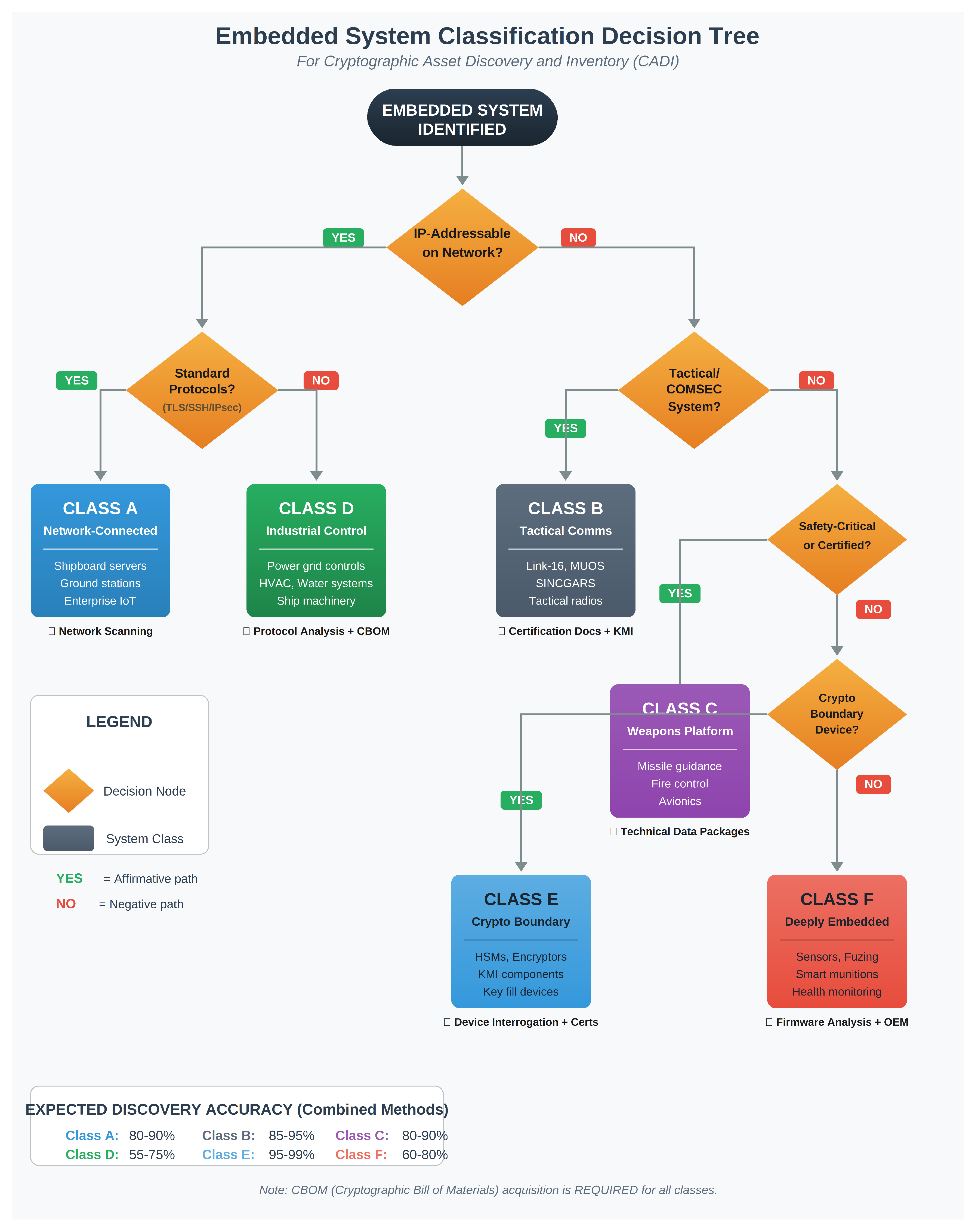

Figure 1 presents a decision tree for classifying embedded systems encountered during CADI operations. The tree guides practitioners through a series of questions to determine the appropriate class and corresponding discovery methodology.

4.2. Class-Specific Characteristics and Discovery Implications

Class A (Network-Connected Embedded): These systems are most amenable to conventional CADI approaches. They use standard protocols with well-documented cryptographic negotiation (TLS ClientHello, SSH key exchange). Expected discovery accuracy: 80–90% with combined scanning and documentation.

Class B (Tactical Communications): These systems use classified cryptographic algorithms (NSA Suite A) and specialized waveforms that commercial CADI tools cannot analyze. Discovery relies entirely on classified technical documentation and KMI/EKMS records. Illustrative coverage: 85–95% through documentation.

Class C (Weapons Platform): Certification constraints prohibit software modification, and proprietary implementations defeat signature-based detection. CBOM acquisition through contractual mechanisms is the primary viable approach. Illustrative coverage: 70–85%, dependent on vendor cooperation.

Class D (Industrial Control): Legacy protocols (Modbus, DNP3, BACnet) often predate modern cryptographic integration. Illustrative coverage: 55–75%, limited by protocol diversity.

Class E (Cryptographic Boundary): The most crypto-intensive devices are the easiest to inventory because cryptography is their primary function. Device interrogation through standard interfaces (PKCS#11, KMIP) reveals supported algorithms. Illustrative coverage: 95–99%.

Class F (Deeply Embedded): These systems present the greatest discovery challenge. Resources are insufficient for any agent deployment, and firmware is often encrypted or inaccessible. Illustrative coverage: 60–80%, heavily dependent on vendor cooperation.

4.3. Detection Methodology Selection Matrix

Table 4 presents a methodology selection matrix mapping detection approaches to system classes.

5. The CBOM Imperative: Documentation as Primary Discovery

The TNO report treats CBOM acquisition as one methodology among many—step 2 in a nine-step effort-accuracy model. For embedded systems, we argue this ordering should be inverted: vendor-provided Cryptographic Bills of Materials should serve as the primary discovery mechanism, with scanning serving only for verification and gap identification. This inversion is most critical for Classes D, E, and F—safety-certified systems (DO-178C avionics, IEC 62443 industrial controllers), cryptographic boundary devices (HSMs, encryptors), and deeply embedded platforms (ASIC/FPGA-based systems, smart munitions)—where agent deployment is infeasible and firmware access is restricted. For Class A and B systems (network-connected embedded Linux endpoints, real-time industrial systems with standard interfaces), scanning and firmware extraction remain viable supplemental methods, though CBOM documentation still provides authoritative baseline coverage.

5.1. Why CBOM Primacy Is Necessary

The constraints established in

Section 3 demonstrate that scanning-based discovery is significantly constrained for embedded systems. Hardware-accelerated cryptography leaves no software trace. Proprietary implementations evade signature detection. Static linking obscures library boundaries. Certification constraints prohibit agent installation. Resource limitations prevent runtime analysis.

The vendor, by contrast, has complete knowledge of the cryptographic implementation. They selected the algorithms, implemented or integrated the code, configured the parameters, and documented the design. A CBOM that captures this vendor knowledge provides more accurate and complete coverage than any external discovery technique.

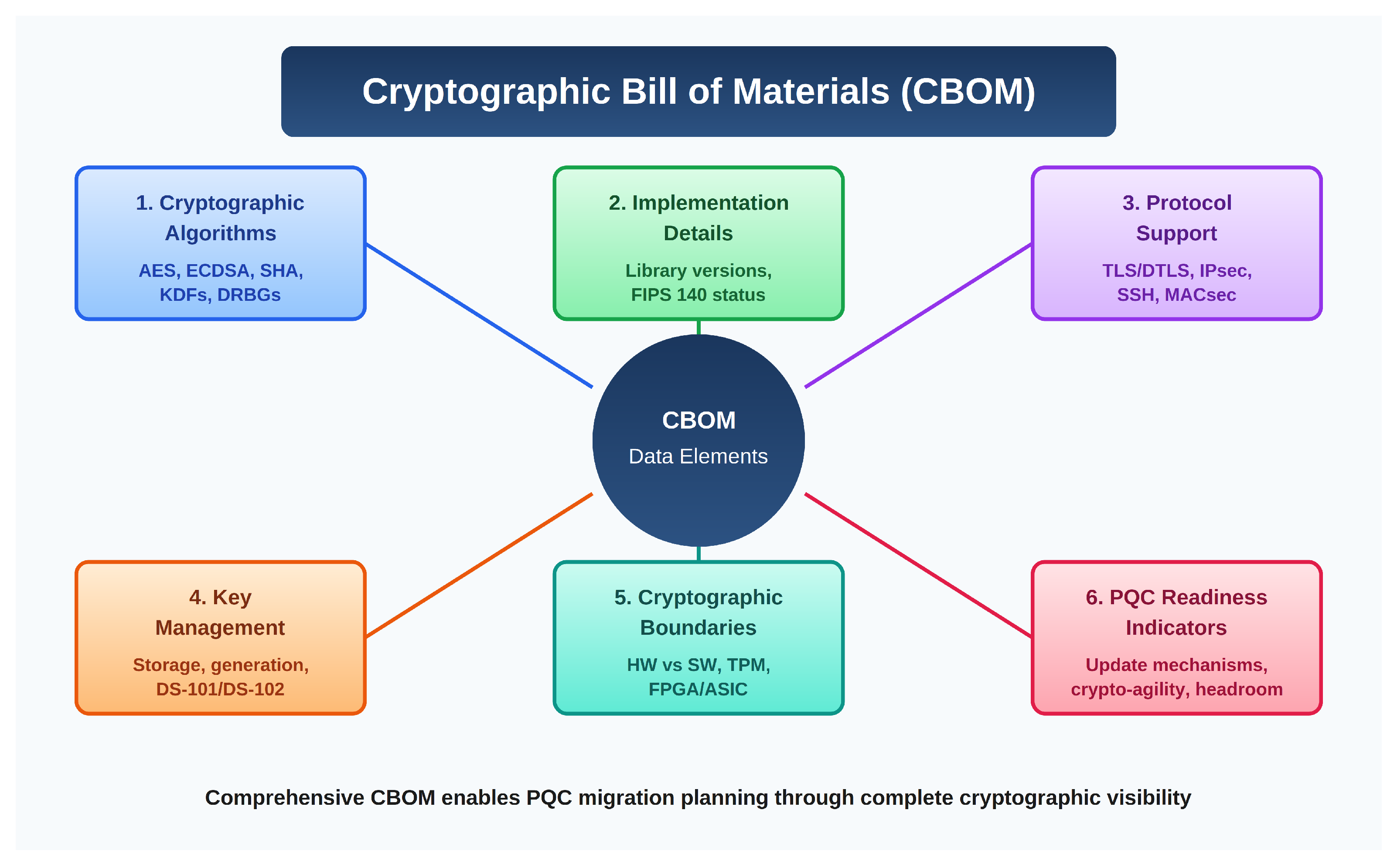

5.2. CBOM Data Element Requirements

A comprehensive CBOM for PQC migration planning should include:

Cryptographic Algorithms: Symmetric algorithms with modes and key sizes (e.g., AES-256-GCM); asymmetric algorithms with curve/parameter sets (e.g., ECDSA P-384); hash functions; key derivation functions; random number generation methods.

Implementation Details: Library name and version (e.g., wolfSSL 5.6.0); FIPS 140-2/3 validation status with certificate number; Common Criteria certification if applicable; custom implementation identification.

Protocol Support: TLS/DTLS versions with supported cipher suites; IPsec/IKE profiles; SSH versions and algorithms; domain-specific protocols (MACsec, WPA3, proprietary).

Key Management: Key storage mechanism (software, TPM, secure element); key generation location (on-device, external); key lifetime and rotation capabilities; key fill/load interfaces (DS-101, DS-102, proprietary).

Cryptographic Boundaries: Hardware vs. software implementation delineation; cryptographic accelerator utilization; secure element/TPM integration; FPGA/ASIC cryptographic functions.

PQC Readiness Indicators: Firmware update mechanism and constraints; cryptographic agility architecture assessment; memory and performance headroom for PQC algorithms; vendor PQC migration roadmap and timeline.

Figure 2 summarizes these CBOM data-element categories and their structural relationship to the cryptographic documentation needed for migration planning.

We recommend adoption of machine-readable CBOM formats. The OWASP CycloneDX CBOM extension [

9] provides a suitable schema. Standardization enables aggregation across system portfolios and automated compliance checking against CNSSP-15 requirements [

38,

39].

5.3. Contractual Mechanisms for CBOM Acquisition

New Acquisitions: CBOM requirements should be incorporated into Statements of Work (SOW) as data deliverables, specified in Contract Data Requirements Lists (CDRLs), and included in technical data package specifications. DFARS 252.204-7012 (Safeguarding Covered Defense Information and Cyber Incident Reporting) establishes baseline safeguarding and reporting obligations for covered defense information, but cryptographic disclosure and CBOM delivery should be explicitly specified as contractual data deliverables [

36].

Existing Systems: For fielded systems without CBOM deliverables, engineering change proposals (ECPs), technology refresh contracts, and sustainment agreements provide vehicles for CBOM acquisition.

6. Detection Methodologies

While CBOM acquisition should be primary, supplemental detection methodologies provide verification and gap coverage.

6.1. Network Traffic Analysis

Methodology: Passive capture of network traffic at aggregation points, analysis of protocol negotiations (TLS ClientHello, SSH key exchange, IKE proposals), extraction of supported cipher suites and algorithm preferences.

Applicability: Class A (primary), Class B (limited—encrypted waveforms), Class D (where IP connectivity exists).

Limitations: Cannot detect cryptography that does not traverse monitored network segments; misses internal storage encryption, local authentication, offline operations.

Tool Recommendations: Zeek (formerly Bro) provides excellent protocol parsing with scriptable analysis.

6.2. Firmware Analysis

Methodology: Extraction of firmware images from devices or vendor sources, static analysis for cryptographic signatures, string searches for algorithm identifiers, binary analysis for known cryptographic constants.

Applicability: Class D (primary), Class F (primary), Class B/C (supplemental).

Critical Limitations: Static linking obscures library boundaries; custom implementations may not match known signatures; obfuscated or encrypted firmware defeats analysis entirely; hardware cryptographic offload leaves no firmware trace.

Tool Recommendations: Binwalk for firmware extraction; Ghidra for binary reverse engineering; custom YARA rules for cryptographic constant detection.

Figure 3 illustrates the end-to-end firmware analysis workflow and its critical limitations for embedded system CADI.

6.3. Device Interrogation

Methodology: Query devices through management interfaces (SNMP, NETCONF, proprietary CLIs) or cryptographic interfaces (PKCS#11, KMIP) to enumerate supported algorithms and current configurations.

Applicability: Class B (primary), Class C (primary), Class E (primary).

Limitations: Requires interface access and credentials; may not reveal algorithms available but not currently configured.

6.4. Negative Testing

Methodology: Attempt connections using specific algorithm sets to verify device behavior, supplementing passive observation with active probing where operationally permitted. Deliberately attempting connections with deprecated mechanisms (e.g., TLS 1.0/1.1, SHA-1 signatures, 1024-bit RSA) [

40,

41,

42] verifies they are properly rejected.

Limitations: Requires operational permission; may trigger security alerts; limited applicability in availability-critical environments.

7. Lightweight Cryptography Considerations

The TNO report does not address lightweight cryptography, yet this domain is critical for embedded systems that cannot accommodate standard PQC algorithm sizes.

7.1. Ascon and the Symmetric Cryptography Standard

NIST selected the Ascon family in 2023 and standardized it in SP 800-232 (published August 2025) [

10] for constrained devices. Ascon provides authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD) and hashing functionality optimized for constrained environments.

However, Ascon addresses symmetric cryptography only (AEAD and hashing). Critically, the NIST lightweight cryptography competition did not address public-key operations, and no standardized lightweight post-quantum asymmetric algorithm currently exists. This creates a fundamental gap: Class F devices that currently use ECC (e.g., P-256) for secure boot verification, key exchange, or digital signatures have no drop-in PQC migration path. Standard ML-KEM and ML-DSA are too large for many constrained devices, HQC is even larger, and Ascon cannot replace public-key functionality. For these systems, “migration” is a misnomer—they require architectural redesign, potentially removing asymmetric cryptography at the edge in favor of pre-shared symmetric keys or gateway-based security architectures.

7.2. Size Constraints and PQC Feasibility

Table 5 compares cryptographic artifact sizes between classical, PQC, and lightweight algorithms [

20,

21,

22].

A Class F deeply embedded sensor with 64 KB total storage cannot accommodate ML-KEM-768 keys (3.5 KB) for multiple peer devices while maintaining application functionality. For many such devices, no drop-in PQC replacement currently exists: HQC (code-based) is even larger than ML-KEM [

13], and no standardized lightweight PQC asymmetric algorithm is available. Such systems require architectural redesign—removing asymmetric cryptography at the edge in favor of pre-shared symmetric keys, gateway-based security architectures, or acceptance of residual risk during transition—rather than simple algorithm substitution. CADI must identify these constraints to inform migration architecture decisions and flag systems requiring capital investment rather than software updates.

8. Accuracy Expectations and Validation

The planning targets derived from the TNO maturity model (

ideal,

MVP for IT) [

5] are not achievable for embedded systems through scanning alone.

Table 6 presents calibrated accuracy expectations based on system classification and discovery methodology. These figures represent engineering planning assumptions derived from feasibility constraints and our interpretation of the TNO effort-accuracy model, not empirically validated measurements or direct TNO quantitative findings.

9. DoD Framework Integration

9.1. Risk Management Framework Integration

Embedded system CADI feeds directly into Risk Management Framework processes [

37]. Security control identifiers referenced below follow NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5 [

43]. During Step 2 (Select Security Controls), CADI results inform SC-8 (Transmission Confidentiality and Integrity), SC-12 (Cryptographic Key Establishment and Management), and SC-13 (Cryptographic Protection) implementation. During Step 4 (Assess Security Controls), CADI provides evidence for assessment of SC-13 compliance with CNSSP-15 requirements [

38,

39] and IA-7 (Cryptographic Module Authentication).

9.2. CNSSP-15 Compliance Verification

Committee on National Security Systems Policy 15 (CNSSP-15) (published 20 October 2016; update noted 4 March 2025) [

27,

38,

39] requires use of National Manager–approved algorithms for protecting classified information. CADI results must map to CNSSP-15 algorithm categories, identifying systems using non-compliant cryptography that require remediation, with transition guidance aligned to CNSA 2.0 and NIST PQC standards [

8,

24].

9.3. PQC Migration Planning Integration

CADI outputs feed directly into PQC migration planning through risk prioritization (systems processing data with long confidentiality requirements warrant earlier migration), capability assessment (systems that cannot accommodate PQC algorithms require architectural mitigation), and sequencing constraints (key management infrastructure must migrate before endpoints).

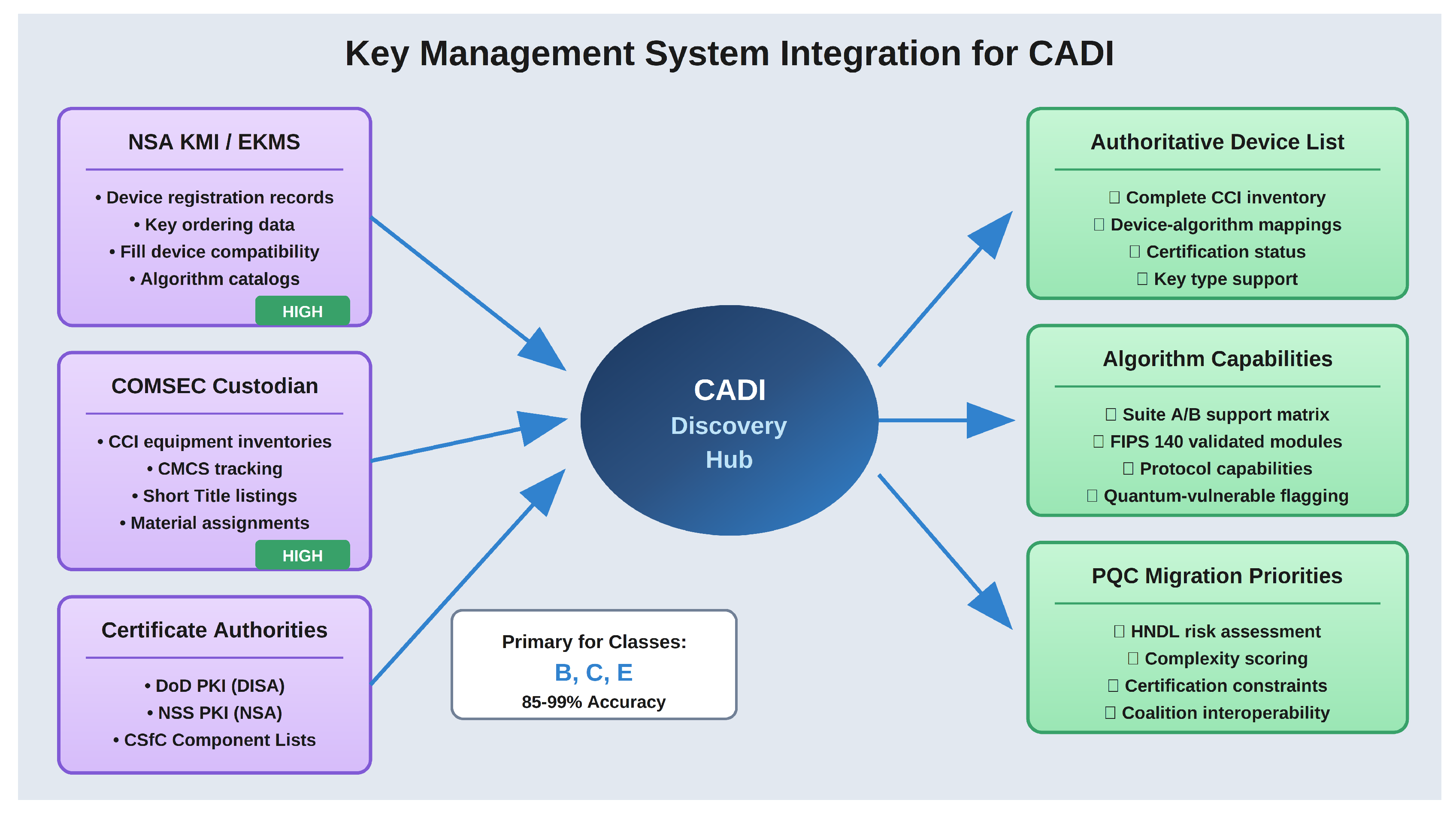

Figure 4 depicts the CADI-to-key-management integration model and shows how discovery results flow into migration planning processes.

10. Implementation Roadmap

Organizations initiating embedded system CADI should follow a phased approach:

Phase 1 (Months 1–3): Documentation Baseline. Compile existing technical data packages; issue CBOM requests to vendors through appropriate contractual mechanisms; extract cryptographic data from certification documentation (FIPS 140, Common Criteria); integrate with KMI/EKMS records for classified systems. Output: documentation-based inventory achieving 60–70% coverage.

Phase 2 (Months 3–6): Supplemental Scanning. Deploy network traffic analysis at aggregation points; conduct firmware analysis for Class D/F systems; perform device interrogation for Class E systems. Output: scanning-based supplemental data achieving 20–40% additional coverage depending on system class mix.

Phase 3 (Month 6): Reconciliation and Gap Analysis. Cross-reference scanning results with documentation; identify discrepancies for investigation; flag systems with insufficient coverage for enhanced vendor engagement.

Phase 4 (Month 6+): Continuous Monitoring Integration. Integrate CADI outputs with SIEM/SOC operations following network integrity best practices [

19]; establish change detection baselines; automate compliance reporting.

11. Discussion

This framework addresses a critical gap in PQC migration readiness. The commercial CADI market, as documented in the TNO report, has not meaningfully addressed embedded systems—one provider explicitly stated no commercial interest in the domain. Yet embedded systems dominate defense computing environments, and their extended migration timelines (10–15+ years for major platforms) create the most acute collision with quantum threat emergence.

The lightweight cryptography gap—standard PQC algorithms (including HQC, which is larger than ML-KEM [

13]) are infeasible for constrained devices while no lightweight PQC asymmetric alternatives are standardized—requires attention beyond the scope of this paper. Systems identified through CADI as unable to accommodate ML-KEM or ML-DSA require architectural review to determine whether gateway-based approaches, pre-shared symmetric keys, hybrid schemes, or acceptance of residual risk is appropriate.

Finally, we note that this framework addresses discovery only, not remediation. The identified cryptographic assets must feed into migration planning processes that account for the certification, lifecycle, and resource constraints detailed in

Section 3. Discovery that identifies a quantum-vulnerable implementation in a DO-178C DAL-A certified system has identified a problem; it has not solved it.

12. Conclusions

Embedded systems represent the most challenging domain for cryptographic asset discovery and simultaneously the domain of greatest consequence for DoD PQC migration. The commercial CADI market remains predominantly enterprise-IT focused; coverage for deeply embedded and mission-constrained platforms is limited, and the fundamental constraints of embedded systems—resource limitations, availability imperatives, certification requirements, and architectural barriers—mean that IT-centric approaches do not readily extend.

This paper contributes: (1) analysis of why embedded systems defeat standard CADI approaches; (2) a six-class taxonomy for embedded system CADI with class-specific methodology guidance; (3) the CBOM imperative establishing documentation as primary discovery mechanism; (4) detailed detection methodologies with explicit capabilities and limitations; (5) lightweight cryptography considerations for constrained devices; (6) lifecycle and certification constraint analysis; (7) realistic accuracy expectations calibrated to embedded system realities; and (8) integration pathways for DoD RMF and PQC migration processes.

The fundamental insight is that for most embedded system classes, vendor-provided CBOMs should serve as the primary discovery mechanism, with automated scanning providing supplemental verification rather than foundational coverage. Organizations that develop embedded-specific CADI capabilities now—and establish contractual mechanisms for CBOM acquisition—will be better positioned for PQC migration execution when the timeline demands action. Given that cryptographic migrations in embedded systems require years to decades depending on system class, the urgency for capability development cannot be overstated.

Author Contributions

R.E.C. conceived the research, developed the framework, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- MITRE. CWE-327: Use of a Broken or Risky Cryptographic Algorithm. Common Weakness Enumeration, 2024. Available online: https://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/327.html (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Cryptographic Agility Considerations for Migrating to Post-Quantum Cryptographic Algorithms; NIST Cybersecurity White Paper (CSWP) 39; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/cswp/39/cryptographic-agility-considerations-for-migrating/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security; NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-82 Rev. 3; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/82/r3/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA). Post-Quantum Cryptography: Current State and Quantum Mitigation, 2021. Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/post-quantum-cryptography-current-state-and-quantum-mitigation (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- TNO (Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research). Cryptographic Inventory Tools: A Market Analysis; Report P11921; TNO: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2025. Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34643323/MaijgV/TNO-2025-P11921.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- The White House. National Security Memorandum on Promoting United States Leadership in Quantum Computing While Mitigating Risks to Vulnerable Cryptographic Systems (NSM-10), 2022. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/04/national-security-memorandum-on-promoting-united-states-leadership-in-quantum-computing-while-mitigating-risks-to-vulnerable-cryptographic-systems/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Open Quantum Safe Project. liboqs: C Library for Quantum-Safe Cryptographic Algorithms. GitHub Repository, 2024. Available online: https://github.com/open-quantum-safe/liboqs (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Moody, D.; Perlner, R.; Regenscheid, A.; Robinson, A.; Cooper, D. Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards; NIST Internal Report (IR) 8547 Initial Public Draft (ipd); National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/ir/8547/ipd (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- OWASP CycloneDX. Cryptographic Bill of Materials (CBOM) Capability, 2024. Available online: https://cyclonedx.org/capabilities/cbom/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Lightweight Cryptography Standardization Process; NIST SP 800-232 (Final); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/232/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD). Final Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography, 2024. Available online: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Final-Report-on-Post-Quantum-Cryptography.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Memorandum M-23-02: Migrating to Post-Quantum Cryptography, 2022. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/M-23-02-M-Migrating-to-Post-Quantum-Cryptography.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Moody, D.; Alagic, G.; Apon, D.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Kelsey, J.; Liu, Y.-K.; Miller, C.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Robinson, A.; Smith-Tone, D. Status Report on the Fourth Round of the NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process; NIST IR 8545 (Final); National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/ir/8545/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC), 2024. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/quantum (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). Preparing for Post-Quantum Cryptography, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/guidance/preparing-for-post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). Quantum-Safe Cryptography, 2024. Available online: https://www.etsi.org/technologies/quantum-safe-cryptography (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC 62443: Industrial Communication Networks—Network and System Security (specifically IEC 62443-3-3: System Security Requirements and Security Levels; IEC 62443-4-2: Technical Security Requirements for IACS Components), 2024. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/publication/33615 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Web Cryptography API (Recommendation), 2017. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WebCryptoAPI/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (NCCoE). Network Integrity Project, 2024. Available online: https://www.nccoe.nist.gov/projects/network-integrity (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard; FIPS PUB 203; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/203/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard; FIPS PUB 204; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/204/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard; FIPS PUB 205; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/205/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Standards for Efficient Cryptography Group (SECG). SEC 1: Elliptic Curve Cryptography; Version 2.0, 2009. Available online: https://www.secg.org/sec1-v2.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Security Agency (NSA). CNSA 2.0: Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0—FAQ, 2022. Available online: https://media.defense.gov/2022/Sep/07/2003071834/-1/-1/0/CSI_CNSA_2.0_FAQ.PDF (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Perlner, R. FIPS 206 (FN-DSA/Falcon) Status Update (Presentation PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/csrc/media/presentations/2025/fips-206-fn-dsa-(falcon)/images-media/fips_206-perlner_2.1.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer. SIAM J. Comput. 1997, 26, 1484–1509. [CrossRef]

- National Security Agency (NSA). Post-Quantum Cybersecurity Resources; Committee on National Security Systems (CNSS) Policy 15, 2024. Available online: https://www.nsa.gov/Cybersecurity/Post-Quantum-Cybersecurity-Resources/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST Releases First 3 Finalized Post-Quantum Encryption Standards (Press Release/News). 13 August 2024. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2024/08/nist-releases-first-3-finalized-post-quantum-encryption-standards (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Advisory Circular (AC) 20-115D: Airborne Software Development Assurance Using RTCA DO-178C and DO-278A, 2023. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_20-115D.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- RTCA. DO-178C Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification (Overview/Reference Page), 2011. Available online: https://www.rtca.org/do-178/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Common Criteria Recognition Arrangement (CCRA). Common Criteria Portal (ISO/IEC 15408), 2024. Available online: https://www.commoncriteriaportal.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- CCRA. Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation (CC:2022), Part 1: Introduction and General Model, 2022. Available online: https://www.commoncriteriaportal.org/files/ccfiles/CC-2022-Part1-Introduction_and_general_model.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Department of Defense (DoD). System Safety; MIL-STD-882E; via ASSIST QuickSearch (current controlled copy), 2012. Available online: https://quicksearch.dla.mil/qsDocDetails.aspx?ident_number=36027 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions, 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cybersecurity-medical-devices-quality-system-considerations-and-content-premarket-submissions (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2555 (NIS 2 Directive): Measures for a High Common Level of Cybersecurity across the Union, 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2555/2022-12-27/eng (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Defense Acquisition Regulations System (DARS). DFARS Clause 252.204-7012, Safeguarding Covered Defense Information and Cyber Incident Reporting (MAY 2024), 2024. Available online: https://www.acquisition.gov/dfars/252.204-7012-safeguarding-covered-defense-information-and-cyber-incident-reporting (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Department of Defense (DoD). DoD Instruction 8510.01: Risk Management Framework (RMF) for DoD Systems; 19 July 2022. Available online: https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/851001p.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Committee on National Security Systems (CNSS). CNSS Policy (CNSSP) No. 15: Use of Public Standards for Secure Information Sharing; 20 October 2016 (superseded by 4 March 2025 revision per [39]; 2016 version cited as last publicly available baseline). Available online: https://www.cnss.gov/CNSS/issuances/Policies.cfm (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Cyber Security and Information Systems Information Analysis Center (CSIAC). Changelog for the DoD Cybersecurity Policy Chart (entry: CNSSP-15 release date 4 March 2025; supersedes prior CNSSP 15 published 20 October 2016), 2025. Available online: https://csiac.dtic.mil/resources/the-dod-cybersecurity-policy-chart/changelog/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Moriarty, K.; Farrell, S. Deprecating TLS 1.0 and TLS 1.1; Request for Comments (RFC) 8996; Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF): 2021. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8996.html (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- McKay, K.; Cooper, D. Guidelines for the Selection, Configuration, and Use of Transport Layer Security (TLS) Implementations; NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-52 Rev. 2; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/52/r2/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Barker, E. Transitioning the Use of Cryptographic Algorithms and Key Lengths; NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-131A Rev. 2; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/131/a/r2/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Joint Task Force. Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations; NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-53 Rev. 5 (Upd. 1); National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/53/r5/upd1/final (accessed on 16 January 2026).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).