Introduction

Vaccination represents one of the most powerful public health interventions, extending its benefits far beyond the prevention of acute infectious diseases [

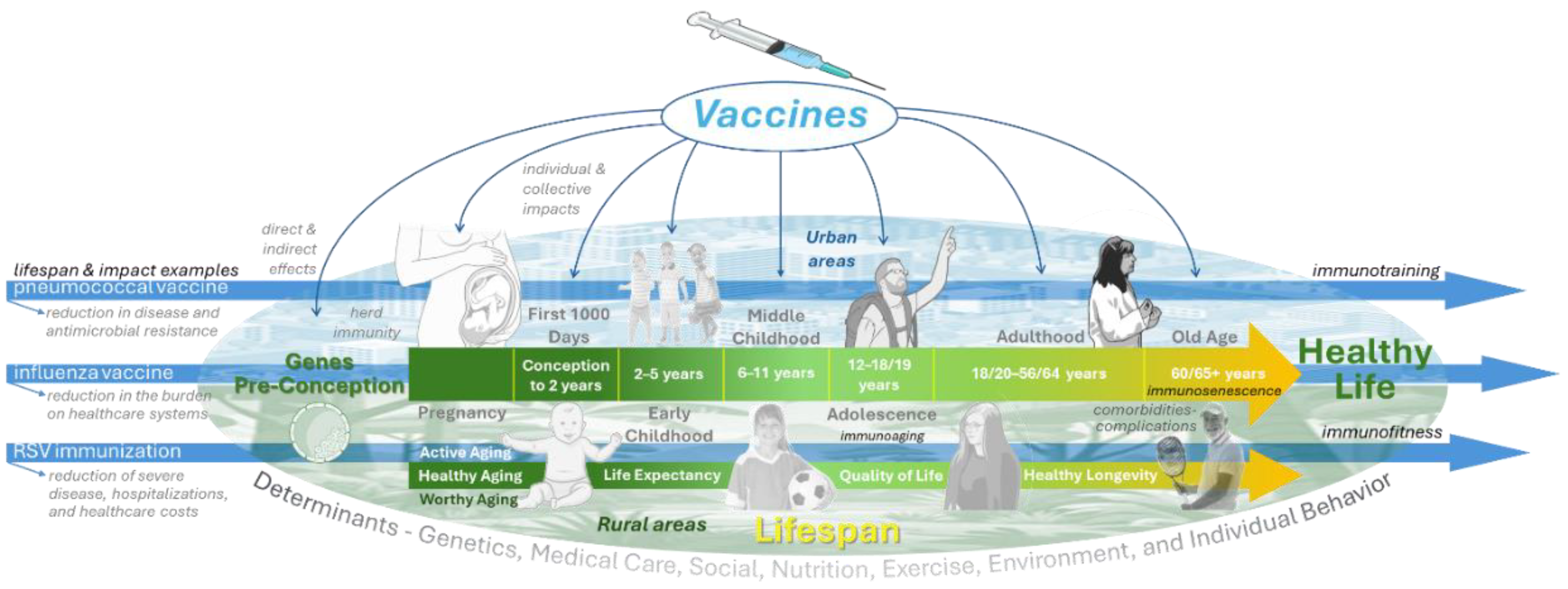

1]. In this second part review, we focused on the broader life-course impact of vaccines and their capacity to extend both lifespan and healthspan (

Figure 1).

From the very beginning of life, vaccines play a critical role in shaping health trajectories. The first 1000 days, spanning from conception to early childhood, represent a window of exceptional vulnerability and opportunity. Immunization during this period not only prevents life-threatening infections but also reduces long-term risks of severe disease, disability, and developmental impairment [

2]. Similarly, vaccines against human papillomavirus (HPV) and hepatitis B virus exemplify how immunization contributes to cancer prevention, while emerging evidence links vaccines to reduced cardiovascular events and protection against other chronic comorbidities [

3].

Vaccines also exert late effects that influence health in adulthood and old age, underscoring their capacity to modify disease risk well beyond the immediate period of administration [

4,

5]. This expanding understanding reinforces the need for proposed immunization schemes that are comprehensive, adaptive, and lifelong, integrating pediatric, adolescent, adult, and older adult vaccination into a coherent continuum of care [

6].

By examining vaccines that extend life, protect during the critical first 1000 days, prevent severe infectious and chronic diseases, and promote long-term resilience, this second part of our review advances the argument that immunization is not only a medical intervention but also a strategy for sustainable health across generations [

7,

8].

These challenges and opportunities are particularly relevant in the Americas, where rapid population aging, persistent inequities, and heterogeneous immunization coverage coexist.

Vaccines That Extend Life

Vaccines are among the few medical interventions clearly associated with gains in lifespan and with potential benefits for healthspan (

Figure 1). By preventing fatal infections and reducing the long-term burden of disease, they contribute to sustained gains in survival across populations [

9,

10]. Historical and contemporary data show that widespread immunization against diseases such as smallpox, measles, pertussis, influenza, and pneumococcal infections has added years to average life expectancy [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Beyond immediate protection, vaccines also reduce complications that accelerate aging, frailty, and the progression of chronic diseases [

16,

17]. Thus, immunization must be understood not only as a means of infection control but also as a cornerstone of longevity and healthy aging strategies [

18].

Impact of Vaccines in the 1000 Days of Life

The first 1000 days of life, spanning from conception through the first two years, constitute a critical window that shapes survival, growth, and long-term health [

19]. During this period, rapid development of the brain and immune system occurs alongside heightened vulnerability to infections, nutritional deficits, and adverse environmental exposures [

20]. In low- and middle-income countries, these challenges translate into high rates of maternal and infant mortality, significant morbidity, and long-term health consequences. Preventive strategies during this window are therefore pivotal, and vaccination stands as one of the most effective and impactful interventions [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Vaccination as a Pillar of Early Survival

Since the inception of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) more than five decades ago, vaccines have prevented an estimated 154 million deaths globally, with the majority of lives saved among children under five years of age [

22,

23,

24]. This represents approximately 40% of the global reduction in child mortality observed in recent decades. Each life saved through immunization yields decades of healthy life, underscoring vaccination as both a survival intervention and an investment in human capital [

25].

Vaccination during pregnancy further enhances this impact by conferring passive protection to the newborn via transplacental antibody transfer [

26]. Pertussis, influenza, and COVID-19 [

27,

28], and, more recently, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines administered to mothers protect both mother and infant [

29,

30], substantially reducing the burden of early-life infections [

31]. Evidence indicates that maternal Tdap vaccination prevents 70–90% of pertussis cases in newborns, whereas influenza immunization during pregnancy can reduce influenza illness in infants by more than 60%. RSV prevention through maternal vaccination or monoclonal antibodies has also proven highly effective in reducing severe respiratory disease and mortality in the neonatal period [

32,

33].

Long-Term Benefits Across the Life Course

The benefits of immunization during the first 1000 days extend far beyond childhood. By preventing infections and their sequelae, vaccines reduce the risk of chronic disease, disability, and premature mortality in adulthood. For instance, avoiding neonatal hepatitis B infection reduces the lifetime risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer [

40,

41]. Preventing severe respiratory infections in infancy preserves lung function, reducing the likelihood of chronic respiratory diseases later in life. Similarly, eliminating measles not only prevents immediate illness but also protects against the long-term immunosuppression that predisposes children to other infections for years after recovery [

42].

In addition, vaccines lower systemic inflammation, protecting developing organs from damage that could predispose individuals to cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disorders in later life. These mechanisms demonstrate that early-life vaccination contributes to healthier trajectories across decades, directly supporting the concept of vaccines as investments in lifelong health and longevity [

43,

44,

45].

Population and Societal Impact

At the population level, early-life immunization has been central to increases in life expectancy. By preventing early childhood mortality and disabling sequelae, vaccines support educational attainment, productivity, and economic development. Cohort studies show that vaccinated children are more likely to reach adulthood and contribute productively to society, making vaccination a cornerstone of both public health and sustainable development [

46].

The first 1000 days of life are critical for long-term individual and population health. Vaccination during this period protects survival, prevents severe infections and disability, and shapes healthier life-course trajectories. By protecting mothers and infants, early immunization builds resilience to immediate threats while influencing lifelong health. Sustaining these benefits requires high coverage, equitable access, and public trust, positioning early-life vaccination as a strategic investment in healthy aging, societal resilience, and intergenerational well-being. [

47].

Prevention of Severe Disease

Vaccination is one of the most effective public health strategies to prevent severe disease, disability, and death across the lifespan (

Figure 1). Beyond preventing infection, vaccines reduce complications, hospitalizations, and long-term sequelae. Influenza, pneumococcal disease, and herpes zoster disproportionately affect adults and older populations, and their prevention through immunization protects individual health, reduces healthcare burden, preserves functional capacity, and supports healthy aging [

48,

49].

Influenza: Preventing Severe Respiratory and Systemic Outcomes

Influenza is a significant cause of seasonal morbidity and mortality, particularly among older adults, pregnant women, young children, and individuals with chronic conditions. Annually, it results in millions of hospitalizations and hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide, with severe cases often complicated by pneumonia, sepsis, cardiovascular events, and exacerbation of underlying comorbidities [

50].

Influenza vaccination significantly reduces severe outcomes, including intensive care admission and death, despite seasonal variability in effectiveness. It is also associated with fewer major cardiovascular events, especially in individuals with heart disease, likely by reducing systemic inflammation and preventing atherosclerotic plaque destabilization [

51].

Influenza vaccines provide benefits across age groups. In pregnant women, vaccination protects both mothers and newborns through passive immunity, whereas in older adults, high-dose, adjuvanted formulations enhance responses despite immunosenescence. Consequently, annual influenza vaccination remains a cornerstone of strategies to reduce global disease burden [

52].

Pneumococcal Disease: Preventing Pneumonia, Invasive Infections, and Complications

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia, invasive disease, and death among adults, particularly in those over 60 years and in patients with comorbidities such as chronic respiratory or cardiovascular conditions. Despite widespread pediatric vaccination programs, significant disease burden persists in adults due to circulating serotypes not fully covered by childhood immunization [

53].

Pneumococcal vaccination protects against pneumonia and invasive disease while reducing systemic complications. Severe pneumococcal infections are linked to acute cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, likely driven by inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, and possible molecular mimicry that may accelerate atherosclerosis [

54].

By preventing pneumococcal infections, vaccines reduce not only respiratory disease but also extrapulmonary complications and associated mortality. Recent conjugate vaccines such as PCV20 and V116 represent significant advances. PCV20 expands coverage to seven additional serotypes beyond PCV13, whereas V116 was explicitly designed for adults and includes unique serotypes that drive disease burden in this group. Both vaccines demonstrate robust immunogenicity, even in older adults with immunosenescence, and simplify immunization schedules by eliminating the need for sequential administration. Vaccination in adulthood, therefore, has broad benefits: reducing hospitalizations, preserving functional capacity, reducing antibiotic use, and contributing to the control of antimicrobial resistance [

55].

Herpes Zoster: Preventing Chronic Pain and Disability

Herpes zoster (shingles), caused by reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus, affects up to one-third of the population during their lifetime, with incidence rising sharply after age 50. The most feared complication, post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), results in chronic pain that may persist for months or years, profoundly impairing quality of life. Other severe outcomes include ocular involvement leading to vision loss, neurological complications such as meningitis or stroke, and disseminated disease in immunocompromised individuals [

56].

The recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) has significantly modified the prevention of zoster. Unlike the live-attenuated vaccine, RZV provides durable and high efficacy—above 85% across all age groups, including those over 80 and immunocompromised patients (

Table 1). By overcoming immune senescence through a potent adjuvant system, RZV elicits robust humoral and cellular immune responses, thereby ensuring long-lasting protection [

57].

Beyond preventing acute shingles, vaccination significantly reduces the incidence of PHN, thereby preserving physical functioning and quality of life (

Table 2). Clinical trials have shown approximately a 90% reduction in PHN incidence, fewer severe pain episodes, and faster symptom resolution in breakthrough cases. Psychological benefits include reduced anxiety and depression associated with shingles, while socioeconomic benefits include fewer missed workdays, reduced caregiver burden, and decreased healthcare costs. Vaccination against herpes zoster is therefore an essential intervention for healthy aging and maintaining independence in older adults [

58].

Integrating Vaccination into Strategies for Preventing Severe Disease

The examples of influenza, pneumococcal disease, and herpes zoster illustrate how vaccines extend beyond infection prevention to avert severe complications, disability, and premature death. They reduce systemic inflammation, protect against secondary cardiovascular and neurological outcomes, and mitigate long-term sequelae. Significantly, their benefits extend to both individual and population levels: preserving functional ability, reducing strain on the healthcare system, and supporting economic productivity [

49,

59].

However, challenges remain. Vaccine uptake in adults is suboptimal worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where access is limited, and awareness is low. Overcoming these barriers requires policies that prioritize adult immunization, integrate vaccination into chronic disease management, and address vaccine hesitancy. In the context of aging populations and increasing comorbidity burdens, the role of vaccines in preventing severe disease must be recognized as central to strategies for promoting longevity and healthy aging [

60].

Cancer Prevention

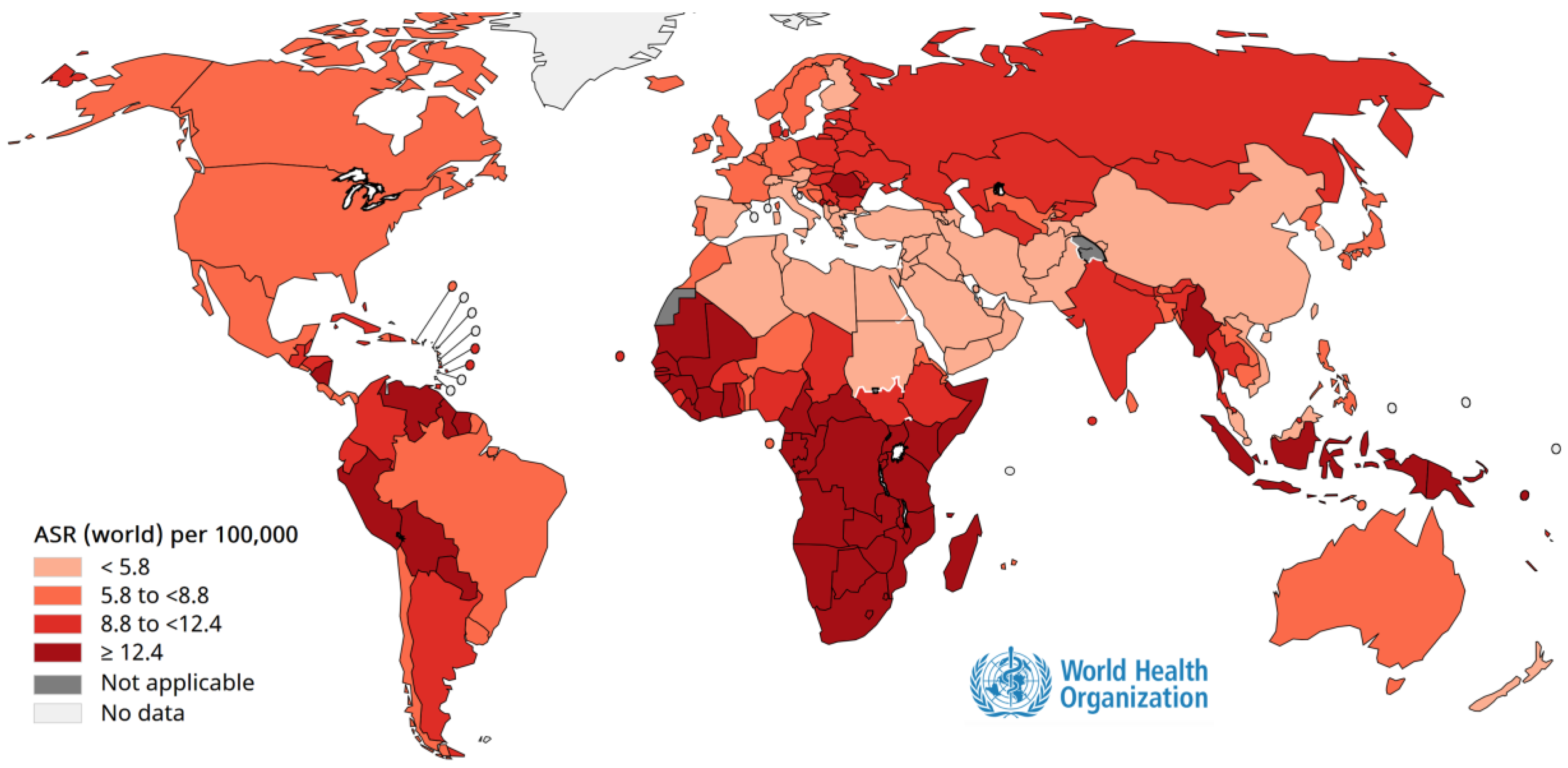

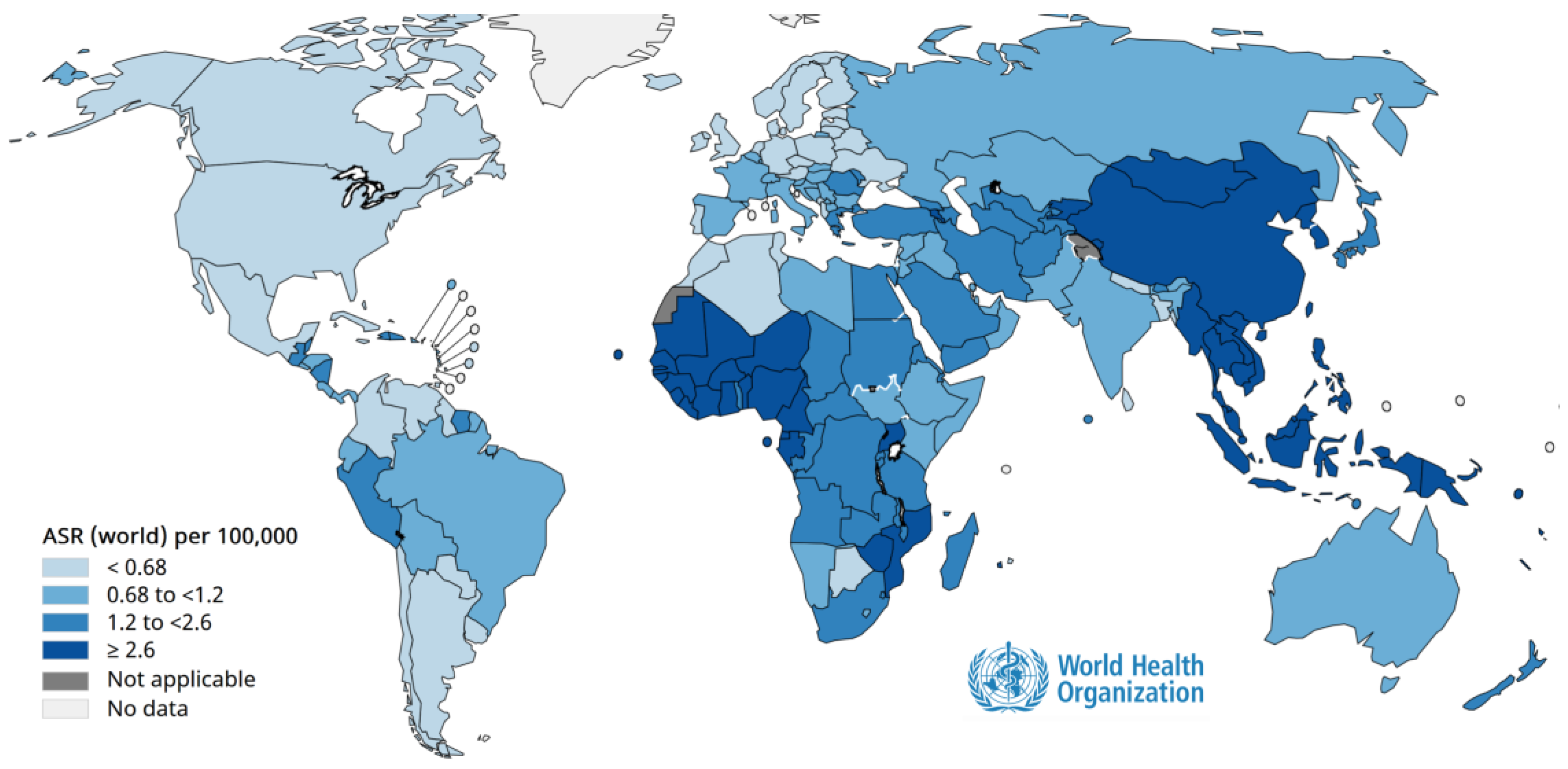

Cancer prevention through vaccination is one of the most remarkable achievements of modern medicine. Persistent infection with oncogenic viruses such as human papillomavirus (HPV) (

Figure 2) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) (

Figure 3) is responsible for a large proportion of cervical, anogenital, and hepatocellular carcinomas worldwide [

61]. Immunization against these viruses not only prevents infection but also interrupts the cascade of cellular changes leading to malignancy [

61]. Population-based programs have demonstrated dramatic declines in cancer incidence in areas with high vaccination coverage, highlighting vaccines as powerful tools for primary cancer prevention and essential components of comprehensive public health strategies [

62].

HPV

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is among the most common viral infections worldwide. It represents the leading cause of cervical cancer, as well as a substantial proportion of anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers. More than 200 HPV genotypes have been identified, of which at least 14 are considered high-risk due to their oncogenic potential. Persistent infection with these high-risk strains, particularly HPV 16 and 18, is responsible for nearly 70% of cervical cancer cases globally. The burden of HPV-related disease underscores the importance of prevention through vaccination as a primary public health strategy [

63].

HPV vaccines represent a landmark achievement in cancer prevention. The first-generation vaccines targeted HPV types 16 and 18, while subsequent formulations expanded coverage to include types 6 and 11 (which cause most genital warts) and additional oncogenic types such as 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. The nonavalent vaccine currently in use provides the broadest protection, covering approximately 90% of HPV types associated with cervical cancer and offering significant protection against other HPV-related malignancies [

64].

The effectiveness of HPV vaccination has been demonstrated in multiple populations worldwide. Countries with high coverage rates have reported dramatic reductions in HPV prevalence, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer incidence among young women. In addition, herd immunity benefits have been observed, with declines in genital warts and HPV-related disease among unvaccinated individuals, including men. These outcomes highlight the potential of vaccination not only to protect individuals but also to shift population-level disease dynamics, moving toward the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem [

65].

Vaccination is most effective when administered before the onset of sexual activity, typically during early adolescence. However, evidence supports extending vaccination to older adolescents and young adults, as many remain unexposed to high-risk HPV strains. Increasingly, public health strategies also emphasize vaccination in boys and men. While cervical cancer prevention remains the primary goal, vaccinating males broadens protection against anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers and further strengthens herd immunity [

3,

62,

65].

Despite the proven effectiveness of HPV vaccination, significant challenges remain. Global coverage is uneven, with wide disparities between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. Barriers include limited resources, lack of awareness, social and cultural resistance, and logistical difficulties in delivering vaccines to adolescents. Addressing these challenges requires concerted international efforts, including support for vaccine affordability, education campaigns to build public confidence, and integration of HPV vaccination into broader reproductive and adolescent health programs [

61,

63,

64].

HPV vaccination is not a replacement for screening but complements it. Cervical cancer screening remains essential, particularly in older women who may not have been vaccinated. The integration of vaccination with screening programs offers a comprehensive approach that maximizes prevention, ensuring both immediate and long-term reductions in HPV-related disease burden [

3,

62,

63,

65].

In summary, HPV vaccination is a transformative intervention that directly prevents infection with oncogenic HPV types, reduces the incidence of precancerous lesions, and ultimately decreases cancer risk. By extending coverage to both sexes and ensuring equitable access worldwide, HPV immunization has the potential to eliminate cervical cancer and significantly reduce the global burden of HPV-associated malignancies [

3,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains one of the most important causes of chronic liver disease and cancer worldwide. It is estimated that nearly 300 million people are living with chronic HBV infection, with more than 800,000 deaths each year attributed to complications such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. HBV is a highly transmissible virus, spreading through blood and bodily fluids, and infection acquired early in life is particularly concerning due to its high likelihood of progressing to chronic disease. Infants infected perinatally have a 90% risk of developing chronic infection, compared to less than 10% in adults. This underscores the importance of early prevention through vaccination as a crucial public health priority [

34].

The introduction of hepatitis B vaccination has transformed the epidemiology of HBV. Universal vaccination programs, particularly those including a birth dose, have drastically reduced HBV prevalence in children and young adults. In countries that implemented widespread vaccination in the 1980s and 1990s, the rates of chronic infection in children under five have dropped to less than 1%. Perhaps most importantly, long-term studies have shown substantial declines in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma among vaccinated cohorts, making HBV vaccination one of the most successful examples of cancer prevention through immunization [

34,

35,

41].

The hepatitis B vaccine is a recombinant subunit vaccine containing the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). It induces protective antibody responses in more than 95% of healthy infants, children, and young adults. Protection is long-lasting, with immunity persisting for at least 30 years in most individuals, and booster doses are generally not required for immunocompetent persons. For optimal impact, the World Health Organization recommends a birth dose within 24 hours of delivery, followed by completion of the primary vaccine series. This strategy effectively interrupts mother-to-child transmission, which is the predominant route of infection in endemic regions [

5,

31,

36,

40].

Beyond preventing perinatal and early childhood infection, hepatitis B vaccination protects individuals later in life from sexual, injection-related, and occupational exposure. It is vital for healthcare workers, immunocompromised patients, and people in high-endemicity regions. Adolescent and adult immunization complements infant programs by closing immunity gaps and reducing transmission [

5,

31,

34,

35,

36,

40,

41].

Despite remarkable progress, challenges remain in achieving universal HBV control. Global coverage with the three-dose infant series has reached approximately 80%, whereas birth-dose coverage remains at around 50%, with significant regional disparities. Barriers include home births without immediate access to healthcare, limited cold-chain capacity, and insufficient awareness of the importance of the birth dose. Expanding timely access, particularly in low-resource settings, is critical to eliminating HBV transmission [

66].

The long-term benefits of HBV vaccination extend far beyond infection control. By preventing chronic hepatitis and liver cancer, vaccination reduces healthcare costs, improves quality of life, and lessens the socioeconomic burden on families and health systems (

Table 3). In the context of global cancer prevention, hepatitis B immunization stands as a model of success, demonstrating how targeted vaccination programs can achieve measurable reductions in cancer incidence and mortality [

31,

41,

66].

In summary, hepatitis B vaccination is a cornerstone of global health and cancer prevention. It protects individuals from one of the most lethal infectious carcinogens, prevents mother-to-child transmission, reduces chronic liver disease (

Table 3), and has been proven to lower hepatocellular carcinoma incidence at the population level. Achieving universal access to timely vaccination, especially the birth dose, is essential for progressing toward the elimination of HBV as a public health threat and securing healthier futures for generations to come [

31,

34,

40,

41,

66].

Impact on Cardiovascular Diseases and Other Comorbidities

The relationship among infectious diseases, inflammation, and chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease, has gained increasing recognition in recent decades. Infections act as acute stressors that can destabilize vulnerable physiological systems, particularly in older adults or individuals with comorbidities. Vaccination, by preventing these infections, not only reduces the incidence of acute illness but also lowers the risk of secondary complications, thereby contributing to healthier aging and a lower mortality rate [

43,

54].

Vaccination and Cardiovascular Health

Respiratory infections, including influenza and pneumococcal disease, are strongly linked to acute cardiovascular events. The risk of myocardial infarction increases up to sixfold shortly after influenza infection, particularly in older adults and those with coronary disease. Influenza vaccination significantly lowers this risk, with meta-analyses showing a 30–36% reduction in myocardial infarction and randomized trials demonstrating fewer major cardiovascular events and deaths after acute myocardial infarction. Consequently, major cardiology societies recommend annual influenza vaccination as part of routine cardiovascular care [

43,

44,

51,

54].

Pneumococcal vaccination provides complementary protection by reducing systemic inflammation and the risk of pneumonia-related cardiovascular complications. Severe pneumococcal infections can trigger vascular endothelial dysfunction, accelerate atherosclerosis, and increase the likelihood of stroke or myocardial infarction. Vaccines that cover a broader spectrum of pneumococcal serotypes, therefore, contribute to cardiovascular prevention alongside their primary role in reducing invasive pneumococcal disease [

39,

43,

44,

45,

51,

54].

Role in Other Chronic Conditions

Beyond cardiovascular health, vaccination also confers protection in individuals with chronic diseases, including diabetes, chronic respiratory conditions, and renal disease. People with diabetes, for example, are two to six times more likely to experience complications or die from influenza compared to the general population. Vaccination in this group reduces hospitalizations, pneumonia, and cardiovascular events, ultimately leading to a lower all-cause mortality rate. Similarly, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma experience fewer exacerbations and reduced hospital admissions when protected against influenza and pneumococcal infections [

18,

51,

59,

67].

Emerging evidence also indicates that vaccination reduces the systemic inflammatory burden that drives many chronic diseases. Chronic low-grade inflammation—often termed “inflammaging”—is linked not only to cardiovascular disease but also to neurodegenerative and autoimmune conditions. By preventing infections that exacerbate inflammatory cascades, vaccines help preserve immune resilience and mitigate progression of these comorbidities [

68].

COVID-19 and Post-Infectious Complications

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the complex interplay between infection and chronic disease. SARS-CoV-2 infection significantly increases the risk of long-term cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, thromboembolic events, and heart failure, even months after recovery. Vaccination has been shown to reduce both acute severe outcomes and the risk of post-infectious complications (e.g. long COVID), underscoring the broader cardiovascular benefits of immunization [

69]. Vaccination reduces the risk of developing long COVID. These benefits have been observed in multiple international studies [

70,

71].

Toward Integrated Prevention

Vaccination should be recognized not only as an intervention for infectious diseases but also as a preventive strategy for chronic non-communicable diseases. By lowering systemic inflammation, reducing hospitalization, and preventing decompensation of underlying conditions, vaccines align with strategies aimed at improving population longevity and quality of life. Integration of adult immunization into cardiovascular and chronic disease management is, therefore, a public health priority [

72].

Long-Term Benefits of Vaccination

Vaccines are often viewed through the lens of their immediate benefits, including protection against infection and reduced transmission. However, growing evidence highlights their long-term impact on health, longevity, and functional capacity. These late effects extend well beyond the prevention of acute illness, shaping trajectories of chronic disease, quality of life, and sustainable aging [

73].

One of the central mechanisms underlying these benefits involves the modulation of chronic inflammation. With advancing age, the immune system often enters a state of low-grade, persistent activation known as inflammaging. This process contributes to the development of chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and neurodegenerative disorders. By preventing infections that exacerbate systemic inflammation, vaccines help limit inflammatory burden and reduce the acceleration of age-related decline. Some vaccines may also enhance anti-inflammatory pathways, supporting immune regulation in older adults [

18,

43,

44,

45,

68].

The benefits are not only biological but also functional. Infections in older adults frequently lead to long-term dependency, reduced mobility, and increased need for institutional care. By preventing these infections, vaccines preserve independence, decrease demand for long-term care services, and protect families and societies from the economic and emotional strain of chronic disability [

49].

There is also clear evidence of vaccines preventing long-term sequelae of infection that directly cause cancer and cardiovascular disease. Hepatitis B and human papillomavirus vaccines reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and cervical cancer, respectively, providing a powerful demonstration of how immunization translates into cancer prevention. Similarly, preventing influenza, pneumococcal disease, and herpes zoster reduces cardiovascular complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke, conditions that frequently follow severe infections and contribute substantially to morbidity in older populations [

3,

43,

55].

Beyond health outcomes, vaccination has broad societal and economic long-term effects. By reducing chronic disease and disability, vaccines lower healthcare costs and enhance the sustainability of health systems. This creates space for resources to be allocated to other pressing needs, while simultaneously promoting healthier, more productive aging populations [

34,

41,

49].

Vaccines are not solely a defense against immediate infection; they are long-term investments in human health. By reducing chronic inflammation, preventing secondary complications, and lowering the risk of cancers and cardiovascular disease, vaccines contribute to healthier aging and extended life expectancy. These late effects underscore the necessity of adopting a life-course approach to immunization, ensuring protection across all ages to maximize both individual and societal benefits [

74].

Proposed Immunization Schemes

A life-course approach to immunization has become a central principle in modern public health (

Figure 1). Proposed schemes integrate vaccination across childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and older age to maximize protection and minimize gaps. Early-life schedules include hexavalent and updated pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, complemented by maternal immunization. Adolescents benefit from HPV vaccination and booster doses of Tdap and meningococcal vaccines. In adults, annual influenza and COVID-19 boosters, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, zoster vaccines, and hepatitis vaccines are recommended based on individual risk. For older adults, high-dose or adjuvanted influenza vaccines, along with RSV and zoster vaccines, address immunosenescence. Overall, these schemes represent a shift toward continuous, life-course protection that supports healthy aging and reduces morbidity (

Figure 1).

Limitations

This second part of the review has important limitations. It is a narrative, perspective-based synthesis without a systematic search strategy or formal quality assessment, resulting in variable strength of evidence across topics. While vaccine effectiveness in preventing infections, hospitalizations, and mortality is well established, evidence for broader benefits, such as reduced cardiovascular events, mitigation of comorbidities, functional decline, or preservation of independence, largely comes from observational studies and biological plausibility and should be viewed as associative rather than causal.

Much of the available evidence derives from high-income countries, limiting generalizability to Latin America and the Caribbean, where vaccination coverage, health systems, and disease burden vary widely. The immunization schemes proposed are conceptual frameworks, not prescriptive recommendations, and should be adapted to local contexts and national priorities. As with all narrative reviews, publication bias cannot be excluded, and emerging findings should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions

Vaccination is one of the most transformative public health achievements, with benefits extending well beyond the prevention of acute infectious diseases. As shown in this review, vaccines not only save lives early in life and prevent severe illness at all ages, but also contribute to cancer prevention, reduce cardiovascular complications, and mitigate comorbidities, with long-term benefits for healthy aging, disability reduction, and quality of life, largely supported by observational evidence.

Part 1 outlined the biological basis of immunosenescence, trained immunity, and vaccine-mediated immune modulation across the lifespan, while Part 2 emphasized vaccines as tools to extend life and healthspan, prevent chronic sequelae, and enhance societal resilience. Together, these findings reinforce immunization as a life-course strategy rather than a childhood-only intervention.

Looking ahead, vaccine policies must emphasize integration, equity, and innovation. Expanding research, ensuring access across all ages, and embedding vaccination into health system planning are essential to maximize its contribution to healthier and more resilient populations across generations.

Funding

This document received the grant support of MSD for its development.

Declaration of competing interest

Alfonso J. Rodriguez-Morales has been a speaker and consultant for the following industries involved in dengue and arbovirus vaccines over the last decade: Sanofi Pasteur, Takeda, Abbott, MSD, Moderna, Valneva, and Bavarian Nordic. Maria L. Avila-Aguero has been a speaker and consultant for the following industries involved in vaccines over the last decade: Sanofi Pasteur, Takeda, MSD, Pfizer. Rest, none.

Acknowledgments

This article has been registered in the Research Proposal Registration of the Coordination of Scientific Integrity and Surveillance of Universidad Cientifica del Sur, Lima, Peru.

References

- Boccalini, S. Value of Vaccinations: A Fundamental Public Health Priority to Be Fully Evaluated. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.E.; Yousafzai, A.K.; McCoy, D.C.; Cuartas, J.; Obradović, J.; Bhopal, S.; Fisher, J.; Jeong, J.; Klingberg, S.; Milner, K., et al. The next 1000 days: building on early investments for the health and development of young children. Lancet 2024, 404, 2094-2116. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Feregrino, R.; Romero-Cabello, R.; Romero-Feregrino, R.; Vilchis-Mora, P.; Muñoz-Cordero, B.; Rodríguez-León, M.A. Sixteen Years of HPV Vaccination in Mexico: Report of the Coverage, Procurement, and Program Performance (2008-2023). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2025, 22. [CrossRef]

- Privor-Dumm, L.A.; Poland, G.A.; Barratt, J.; Durrheim, D.N.; Deloria Knoll, M.; Vasudevan, P.; Jit, M.; Bonvehí, P.E.; Bonanni, P. A global agenda for older adult immunization in the COVID-19 era: A roadmap for action. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5240-5250. [CrossRef]

- Roses, M.; Bonvehí, P.E. Vaccines in adults. Medicina (B Aires) 2019, 79, 552-558.

- da Silva, A.L.; Marinho, A.; Santos, A.L.F.; Maia, A.F.; Roteli-Martins, C.M.; Fernandes, C.E.; Fridman, F.Z.; Lajos, G.J.; Ballalai, I.; Cunha, J., et al. Immunization in women's lives: present and future. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2024, 46. [CrossRef]

- Domachowske, J.B. New and Emerging Passive Immunization Strategies for the Prevention of RSV Infection During Infancy. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2024, 13, S115-s124. [CrossRef]

- Langel, S.N.; Blasi, M.; Permar, S.R. Maternal immune protection against infectious diseases. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 660-674. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Puerta-Arias, M.C.; Husni, R.; Montenegro-Idrogo, J.J.; Escalera-Antezana, J.P.; Alvarado-Arnez, L.E.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Camacho-Moreno, G.; Mendoza, H.; Rodriguez-Sabogal, I.A., et al. Infectious diseases prevention and vaccination in migrants in Latin America: The challenges of transit through the treacherous Darien gap, Panama. Travel Med Infect Dis 2025, 65, 102839. [CrossRef]

- Domingues, C.; Safadi, M.A.P.; Espinal, C.; Trejo Varon, R.; Becerra-Posada, F.; Ospina-Henao, S. Strategies for expanding childhood vaccination in the Americas following the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2024, 48, e29. [CrossRef]

- Avila-Aguero, M.L.; Betancourt-Cravioto, M.; Trejo Varon, R.; Torres, J.P.; Lucas, A.G.; Becerra-Posada, F.; Espinal, C. Impact of acellular immunization against pertussis; comparative experience of four countries in North, Central and South America. Expert Rev Vaccines 2025, 24, 834-839. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Feregrino, R.; Romero-Feregrino, R.; Romero-Cabello, R.; Muñoz-Cordero, B.; Madrigal-Alonso, B.; Rocha-Rocha, V.M. Nineteen-Year Evidence on Measles-Mumps-Rubella Immunization in Mexico: Programmatic Lessons and Policy Implications. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Feregrino, R.; Romero-Cabello, R.; Rodríguez-León, M.A.; Rocha-Rocha, V.M.; Romero-Feregrino, R.; Muñoz-Cordero, B. Report of the Influenza Vaccination Program in Mexico (2006-2022) and Proposals for Its Improvement. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Guilarte, L.; Méndez, C.; Reyes, A.; Rios, M.; Román, F.; Moreno-Tapia, D.; Cabrera, A.; Rivera, D.B.; Gutiérrez-Vera, C.; Palacios, P.A., et al. Influenza vaccines promote humoral and cellular immune responses: a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Nat Commun 2025, 10.1038/s41467-025-67102-y. [CrossRef]

- Mezones-Holguín, E.; Bolaños-Díaz, R.; Fiestas, V.; Sanabria, C.; Gutiérrez-Aguado, A.; Fiestas, F.; Suárez, V.J.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Hernández, A.V. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in preventing pneumonia in Peruvian children. J Infect Dev Ctries 2014, 8, 1552-1562. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.E.; Lynfield, R.; Losso, M.H.; Davey, R.T.; Cozzi-Lepri, A.; Wentworth, D.; Uyeki, T.M.; Gordin, F.; Angus, B.; Qvist, T., et al. Comparison of the Outcomes of Individuals With Medically Attended Influenza A and B Virus Infections Enrolled in 2 International Cohort Studies Over a 6-Year Period: 2009-2015. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017, 4, ofx212. [CrossRef]

- Brenol, C.V.; Azevedo, V.F.; Bonvehi, P.E.; Coral-Alvarado, P.X.; Granados, J.; Muñoz-Louis, R.; Pineda, C.; Vizzotti, C. Vaccination Recommendations for Adults With Autoimmune Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases in Latin America. J Clin Rheumatol 2018, 24, 138-147. [CrossRef]

- Garmany, A.; Yamada, S.; Terzic, A. Longevity leap: mind the healthspan gap. NPJ Regen Med 2021, 6, 57. [CrossRef]

- Debbag, R.; Torres, J.R.; Falleiros-Arlant, L.H.; Avila-Aguero, M.L.; Brea-Del Castillo, J.; Gentile, A.; Saez-Llorens, X.; Mascarenas, A.; Munoz, F.M.; Torres, J.P., et al. Are the first 1,000 days of life a neglected vital period to prevent the impact on maternal and infant morbimortality of infectious diseases in Latin America? Proceedings of a workshop of experts from the Latin American Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, SLIPE. Front Pediatr 2023, 11, 1297177. [CrossRef]

- Mertens, A.; Benjamin-Chung, J.; Colford, J.M., Jr.; Coyle, J.; van der Laan, M.J.; Hubbard, A.E.; Rosete, S.; Malenica, I.; Hejazi, N.; Sofrygin, O., et al. Causes and consequences of child growth faltering in low-resource settings. Nature 2023, 621, 568-576. [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, S.; Verweij, E.J.J.; Beijers, R.; Bijma, H.H.; Been, J.V.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.M.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Steegers, E.A.P. The Impact of Maternal Prenatal Stress Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic during the First 1000 Days: A Historical Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Tregnaghi, P.; Ospina-Henao, S.; Maldonado Oliva, C.; Bocanegra, C.L.; Toledo, C.; Aldaz, C.; Pérez, G.; Díaz Ortega, J.L.; Castelli, J.M.; Aguilar, L., et al. Innovation and immunization program management: traceability and quality in Latin America and the Caribbean, laying the groundwork for a regional action plan. Expert Rev Vaccines 2022, 21, 1023-1028. [CrossRef]

- Evans-Gilbert, T.; Figueroa, J.P.; Bonvehí, P.; Melgar, M.; Stecher, D.; Kfouri, R.; Munoz, G.; Bansie, R.; Valenzuela, R.; Verne, E., et al. Establishing priorities to strengthen National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2310-2316. [CrossRef]

- Panero, M.S.; Khuri-Bulos, N.; Biscayart, C.; Bonvehí, P.; Hayajneh, W.; Madhi, S.A. The role of National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAG) in strengthening health system governance: Lessons from three middle-income countries-Argentina, Jordan, and South Africa (2017-2018). Vaccine 2020, 38, 7118-7128. [CrossRef]

- Hoest, C.; Seidman, J.C.; Lee, G.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Ali, A.; Olortegui, M.P.; Bessong, P.; Chandyo, R.; Babji, S.; Mohan, V.R., et al. Vaccine coverage and adherence to EPI schedules in eight resource poor settings in the MAL-ED cohort study. Vaccine 2017, 35, 443-451. [CrossRef]

- Sáfadi, M.A.P.; Asturias, E.J.; Colomar, M.; Gentile, A.; Miranda, J.; Sáez-Llorens, X.; Torres, J.P.; Ulloa Gutierrez, R.; Avila-Agüero, M.L.; Munoz, F.M. Identifying Gaps and Opportunities for Maternal and Neonatal Immunization Research and Implementation in Latin America. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2025, 44, S18-s22. [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Agüero, M.L.; Debbag, R.; Brenes-Chacón, H.; Brea-Del Castillo, J.; Falleiros-Arlant, L.H.; Soriano-Fallas, A.; Torres Martínez, C.N.; Dueñas, L.; Mascareñas-de Los Santos, A.H.; Lopez, P., et al. Advancing Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) prevention in Latin America: updated recommendations from the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society of Latin America (SLIPE) expert group on RSV prevention. Expert Rev Vaccines 2025, 24, 578-580. [CrossRef]

- Avila-Aguero, M.L.; Falleiros-Arlant, L.H.; Brea, J.; Espinal, C.; Muñoz, F. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention in infants and equity in Latin America and the Caribbean: from evidence to action. Lancet Reg Health Am 2025, 52, 101316. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; León-Figueroa, D.A.; Romaní, L.; McHugh, T.D.; Leblebicioglu, H. Vaccination of children against COVID-19: the experience in Latin America. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2022, 21, 14. [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.A.; Melo-González, F.; Gutierrez-Vera, C.; Schultz, B.M.; Berríos-Rojas, R.V.; Rivera-Pérez, D.; Piña-Iturbe, A.; Hoppe-Elsholz, G.; Duarte, L.F.; Vázquez, Y., et al. Inactivated Vaccine-Induced SARS-CoV-2 Variant-Specific Immunity in Children. mBio 2022, 13, e0131122. [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Widmer, M.; Coomarasamy, A.; Goudar, S.S.; Berrueta, M.; Coutinho, E.; Gaaloul, M.E.; Faden, R.R.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Justus Hofmeyr, G., et al. Advancing maternal and perinatal health through clinical trials: key insights from a WHO global consultation. Lancet Glob Health 2025, 13, e740-e748. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, G.; Villena, R.; Cabrera, C.; Albornoz, J.; Hueichao, N.; Guerra, C.; Torres, J.P. Safety of timely immunization with nirsevimab in hospitalized preterm infants. Vaccine 2025, 63, 127591. [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.P.; Sauré, D.; Goic, M.; Thraves, C.; Pacheco, J.; Burgos, J.; Trigo, N.; Del Solar, F.; Neira, I.; Díaz, G., et al. Effectiveness and impact of nirsevimab in Chile during the first season of a national immunisation strategy against RSV (NIRSE-CL): a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2025, 25, 1189-1198. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.E.; Toy, P.; Kamili, S.; Taylor, P.E.; Tong, M.J.; Xia, G.L.; Vyas, G.N. Eradicating hepatitis B virus: The critical role of preventing perinatal transmission. Biologicals 2017, 50, 3-19. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.H.; Chen, C.J.; Lai, M.S.; Hsu, H.M.; Wu, T.C.; Kong, M.S.; Liang, D.C.; Shau, W.Y.; Chen, D.S. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997, 336, 1855-1859. [CrossRef]

- Sabbatucci, M.; Odone, A.; Signorelli, C.; Siddu, A.; Maraglino, F.; Rezza, G. Improved Temporal Trends of Vaccination Coverage Rates in Childhood after the Mandatory Vaccination Act, Italy 2014-2019. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Rodríguez, G.L.; Salazar-Loor, J.; Rivas-Condo, J.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Navarro, J.C.; Ramírez-Iglesias, J.R. Routine Immunization Programs for Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ecuador, 2020-Hidden Effects, Predictable Consequences. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Castrejon, M.M.; Leal, I.; de Jesus Pereira Pinto, T.; Guzmán-Holst, A. The impact of COVID-19 and catch-up strategies on routine childhood vaccine coverage trends in Latin America: A systematic literature review and database analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18, 2102353. [CrossRef]

- Global, regional, and national trends in routine childhood vaccination coverage from 1980 to 2023 with forecasts to 2030: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 235-260. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mukandavire, C.; Cucunubá, Z.M.; Echeverria Londono, S.; Abbas, K.; Clapham, H.E.; Jit, M.; Johnson, H.L.; Papadopoulos, T.; Vynnycky, E., et al. Estimating the health impact of vaccination against ten pathogens in 98 low-income and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2030: a modelling study. Lancet 2021, 397, 398-408. [CrossRef]

- Seto, W.K.; Lo, Y.R.; Pawlotsky, J.M.; Yuen, M.F. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 2018, 392, 2313-2324. [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Cilloniz, C.; Aldea, M.; Mena, G.; Miró, J.M.; Trilla, A.; Vilella, A.; Menéndez, R. Adult vaccinations against respiratory infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2025, 23, 135-147. [CrossRef]

- Heidecker, B.; Libby, P.; Vassiliou, V.S.; Roubille, F.; Vardeny, O.; Hassager, C.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Cooper, L.T.; Schoenrath, F., et al. Vaccination as a new form of cardiovascular prevention: a European Society of Cardiology clinical consensus statement. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 3518-3531. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gonzalez, M.A.; Ortega-Rivera, O.A.; Steinmetz, N.F. Two decades of vaccine development against atherosclerosis. Nano Today 2023, 50. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Hansson, G.K. Vaccination Strategies and Immune Modulation of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2020, 126, 1281-1296. [CrossRef]

- Carrico, J.; La, E.M.; Talbird, S.E.; Chen, Y.T.; Nyaku, M.K.; Carias, C.; Mellott, C.E.; Marshall, G.S.; Roberts, C.S. Value of the Immunization Program for Children in the 2017 US Birth Cohort. Pediatrics 2022, 150. [CrossRef]

- Philip, R.K.; Attwell, K.; Breuer, T.; Di Pasquale, A.; Lopalco, P.L. Life-course immunization as a gateway to health. Expert Rev Vaccines 2018, 17, 851-864. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B. Adjuvant strategies to improve vaccination of the elderly population. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018, 41, 34-41. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B. Vaccination of older adults: Influenza, pneumococcal disease, herpes zoster, COVID-19 and beyond. Immun Ageing 2021, 18, 38. [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.J.; Doyle, J.D.; Uyeki, T.M. Influenza virus-related critical illness: prevention, diagnosis, treatment. Crit Care 2019, 23, 214. [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, A.; Abou Farah, J.; Saade, E. Is Influenza Vaccination Our Best 'Shot' at Preventing MACE? Review of Current Evidence, Underlying Mechanisms, and Future Directions. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, W.; Chen, W.H.; Hopkins, R.H.; Neuzil, K. Effective Immunization of Older Adults Against Seasonal Influenza. Am J Med 2018, 131, 865-873. [CrossRef]

- Flem, E.; Mouawad, C.; Palmu, A.A.; Platt, H.; Johnson, K.D.; McIntosh, E.D.; Abadi, J.; Buchwald, U.K.; Feemster, K. Indirect protection in adults ≥18 years of age from pediatric pneumococcal vaccination: a review. Expert Rev Vaccines 2024, 23, 997-1010. [CrossRef]

- Fountoulaki, K.; Tsiodras, S.; Polyzogopoulou, E.; Olympios, C.; Parissis, J. Beneficial Effects of Vaccination on Cardiovascular Events: Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, Heart Failure. Cardiology 2018, 141, 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Janssens, E.; Flamaing, J.; Vandermeulen, C.; Peetermans, W.E.; Desmet, S.; De Munter, P. The 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20): expected added value. Acta Clin Belg 2023, 78, 78-86. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.G.E. The Spectrum of Neurological Manifestations of Varicella-Zoster Virus Reactivation. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.J.; Weinberg, A. Immune responses to zoster vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019, 15, 772-777. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, I.; Lu, X.; Dawson, H.; Bricout, H.; O'Hanlon, H.; Yu, E.; Nozad, B. Assessing the effectiveness of zoster vaccine live: A retrospective cohort study using primary care data in the United Kingdom. Vaccine 2018, 36, 7105-7111. [CrossRef]

- Addario, A.; Célarier, T.; Bongue, B.; Barth, N.; Gavazzi, G.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Impact of influenza, herpes zoster, and pneumococcal vaccinations on the incidence of cardiovascular events in subjects aged over 65 years: a systematic review. Geroscience 2023, 45, 3419-3447. [CrossRef]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Ramzan, I.; Weekes, L.; Kayser, V. Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.R.; Palefsky, J.M.; Goldstone, S.E.; Bornstein, J.; De Coster, I.; Guevara, A.M.; Mogensen, O.; Schilling, A.; Van Damme, P.; Vandermeulen, C., et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-valent human papillomavirus vaccine: Post hoc analysis from five phase 3 studies. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2025, 21, 2425146. [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, M.T.; Araya, A.X.; Gajardo, M.; Chepo, M.; Torres, R.; Schilling, A. Acceptability of HPV Vaccines: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Summary. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kiamba, E.W.; Goodier, M.R.; Clarke, E. Immune responses to human papillomavirus infection and vaccination. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1591297. [CrossRef]

- Joura, E.A.; Pils, S. Vaccines against human papillomavirus infections: protection against cancer, genital warts or both? Clin Microbiol Infect 2016, 22 Suppl 5, S125-s127. [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.; Brotherton, J.M.; Pillsbury, A.; Jayasinghe, S.; Donovan, B.; Macartney, K.; Marshall, H. The impact of 10 years of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Australia: what additional disease burden will a nonavalent vaccine prevent? Euro Surveill 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Sun, M.; Yang, H.; Du, S.; Sun, L.; Mao, Y. 2024 latest report on hepatitis B virus epidemiology in China: current status, changing trajectory, and challenges. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2025, 14, 66-77. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, W.C.; Lung, D.C.; Tam, T.C.; Yap, D.Y.; Ma, T.F.; Tsui, C.K.; Zhang, R.; Lam, D.C.; Ip, M.S.; Ho, J.C. Protective Effects from Prior Pneumococcal Vaccination in Patients with Chronic Airway Diseases during Hospitalization for Influenza-A Territory-Wide Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Motta, F.; Barone, E.; Sica, A.; Selmi, C. Inflammaging and Osteoarthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2023, 64, 222-238. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Lopez-Echeverri, M.C.; Perez-Raga, M.F.; Quintero-Romero, V.; Valencia-Gallego, V.; Galindo-Herrera, N.; López-Alzate, S.; Sánchez-Vinasco, J.D.; Gutiérrez-Vargas, J.J.; Mayta-Tristan, P., et al. The global challenges of the long COVID-19 in adults and children. Travel Med Infect Dis 2023, 54, 102606. [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Kulzhabayeva, D.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Gill, H.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Lui, L.M.W.; Cao, B.; Mansur, R.B.; Ho, R.C., et al. COVID-19 vaccination for the prevention and treatment of long COVID: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2023, 111, 211-229. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, K.T.; Cormier, L.E.; Pontus, C.; Bergman, A.; Webley, W. Long COVID's Impact on Patients, Workers, & Society: A review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e37502. [CrossRef]

- Micheletto, C.; Aliberti, S.; Andreoni, M.; Blasi, F.; Di Marco, F.; Di Matteo, R.; Gabutti, G.; Harari, S.; Gentile, I.; Parrella, R., et al. Vaccination Strategies in Respiratory Diseases: Recommendation from AIPO-ITS/ETS, SIMIT, SIP/IRS, and SItI. Respiration 2025, 104, 556-574. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Jang, Y.H.; Seo, S.U.; Chang, J.; Seong, B.L. Non-specific Effect of Vaccines: Immediate Protection against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection by a Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 83. [CrossRef]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Triolo, F.; Maggi, S.; Malley, R.; Jackson, T.A.; Poscia, A.; Bernabei, R.; Ferrucci, L.; Fratiglioni, L. Fostering healthy aging: The interdependency of infections, immunity and frailty. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 69, 101351. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).