Submitted:

17 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

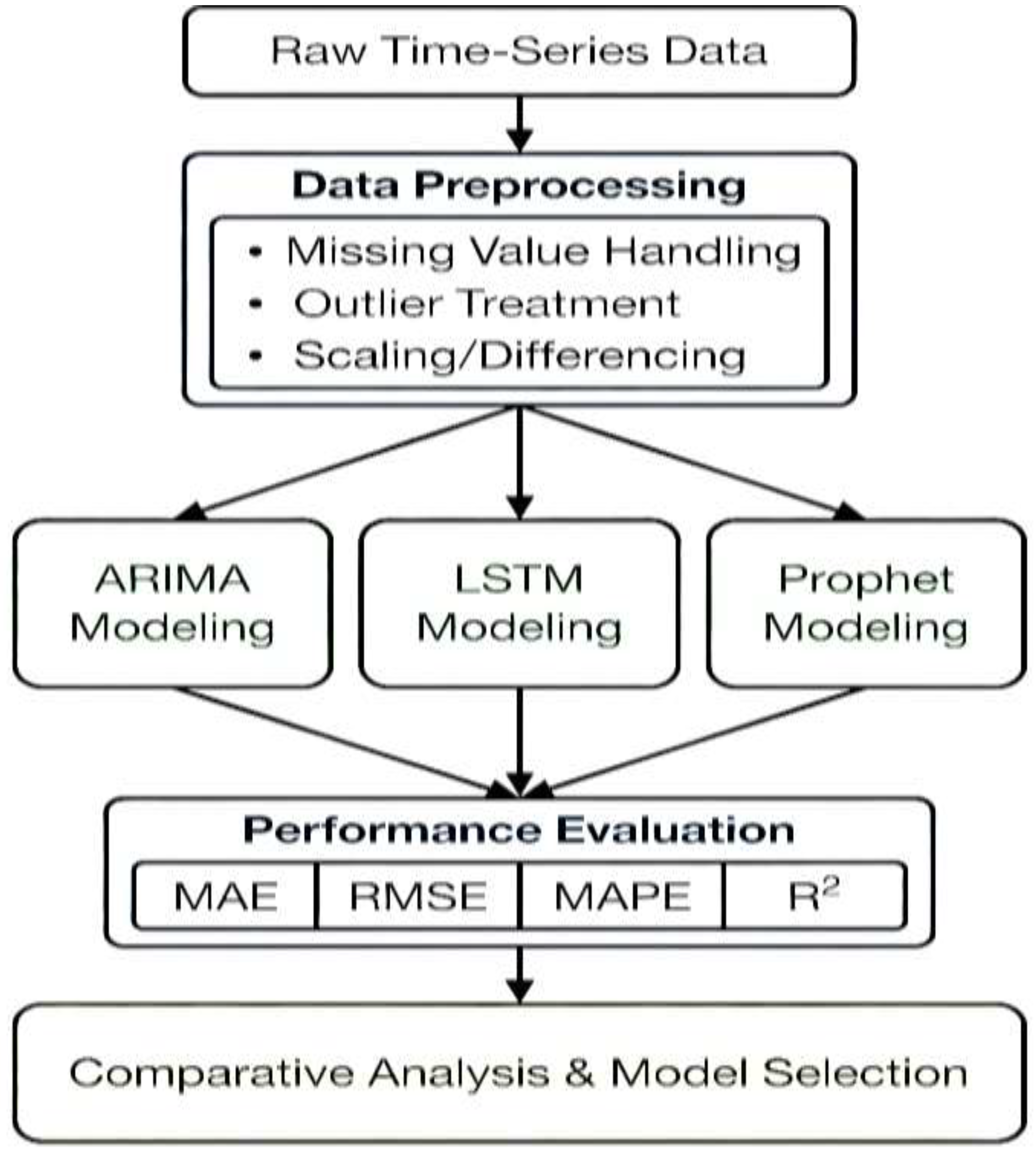

2. Theoretical Framework

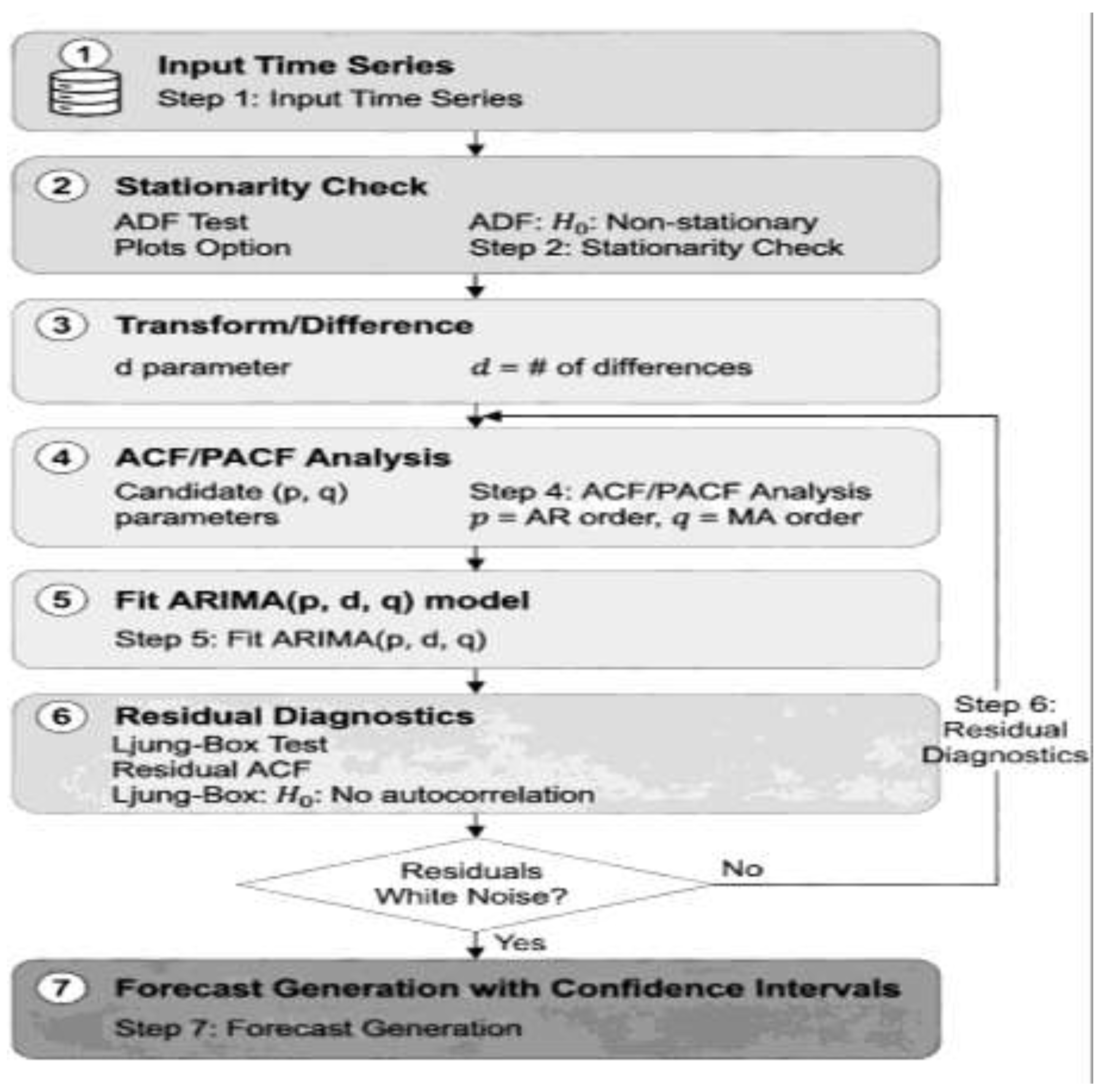

2.1. ARIMA: Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average

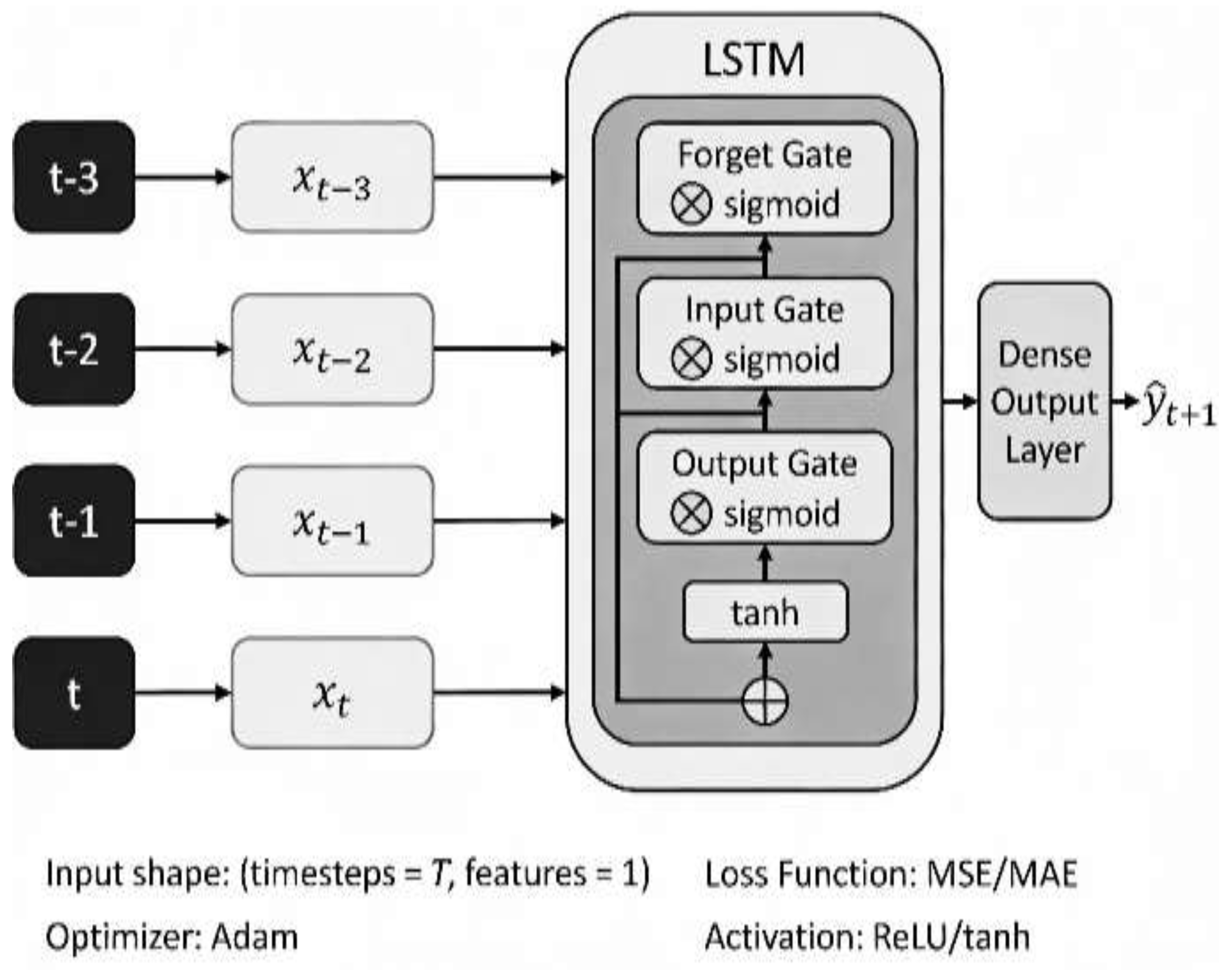

2.2. LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory Networks

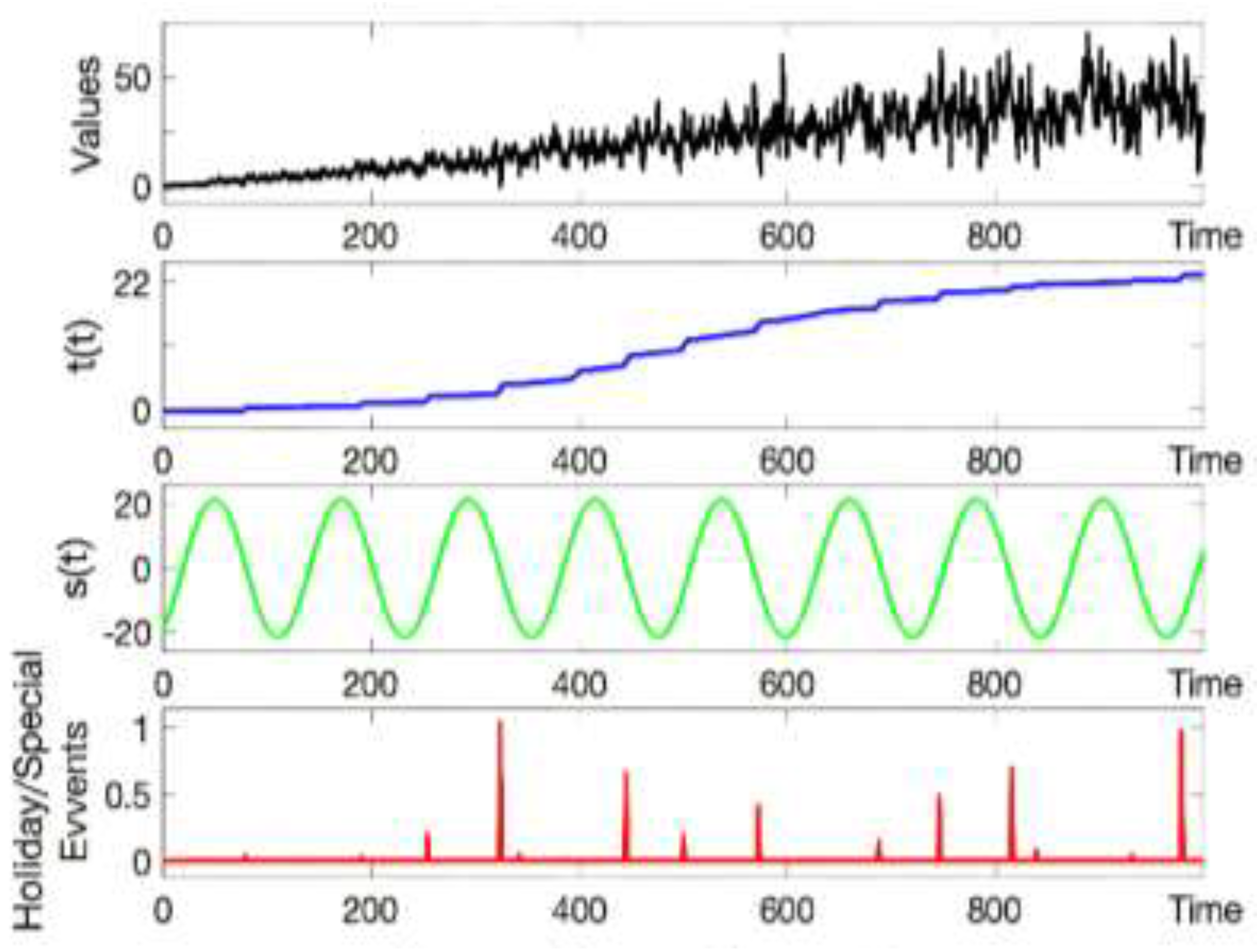

2.3. Prophet: Automated Forecasting Procedure

3. Literature Review

3.1. Performance Metrics and Empirical Studies

3.2. Domain-Specific Applications

- Financial Forecasting: Comparative studies on financial datasets demonstrate significant performance variations [4,35,51,56]. LSTM achieved 84–87% reduction in error rates compared to ARIMA [1,35,51,56], with MAPE values of 4.06–26.02% for hourly predictions versus ARIMA’s 7.21–43.48% [35,51,56]. ARIMA maintained consistent performance (MAPE 3.20–13.60%) for daily and longer forecasts [35,51]. Stock price prediction studies show LSTM achieved R² = 0.96–0.97 on test datasets [51,56], while hybrid models achieved R² = 0.98–0.99 on complex stock data [39,62].

- Energy and Environmental Applications: Renewable energy forecasting reveals LSTM demonstrated R² = 0.986 on wind power prediction [37], while hybrid GRU-attention models achieved 75% error reduction over traditional methods [63]. Prophet proved effective for solar power with clear daily patterns (MAPE < 10%) [5,32,37], and SARIMA remained comparable to LSTM on seasonal energy data (MAPE 6–8%) [48,50]. CNN-LSTM combinations improved accuracy by 20–30% on multi-step forecasting [37,64]. Air quality forecasting shows LSTM outperformed ARIMA by 15–25% on PM2.5 prediction [5,65], with ensemble methods combining ARIMA, LSTM, and Prophet achieving best performance [66].

- Healthcare and Disease Prediction: COVID-19 case forecasting demonstrates hybrid ARIMA-LSTM achieved lowest errors (MSE = 2,501,541; MAPE = 6.43%) [8,41], while LSTM outperformed ARIMA by 30–40% on pandemic data [7,8,41]. Prophet handled holiday effects well but struggled with volatile spikes [7,8], and ensemble models combining all three approaches improved predictions 15–20% [7,42].

- Traffic and Retail Applications: Traffic prediction studies show LSTM outperformed ARIMA for short-term traffic prediction [6,34,68], while ARIMA maintained competitive performance for daily aggregates (MAPE 2.9%) [34,51]. Hybrid LSTM-GRU models achieved 85–92% accuracy on hourly traffic [68]. For sales forecasting, daily forecasting shows ARIMA (MAPE 2.9–13.6%), Prophet (MAPE 2.2–24.2%), and LSTM (MAPE 6.6–20.8%) [35,51], while Prophet excels for retail with strong weekly/yearly seasonality [2,31,32,35].

3.3. Forecasting Horizon and Data Characteristics

3.4. Research Gap and Problem Statement

3.5. Hybrid and Ensemble Approaches

3.6. Methodology and Research Design

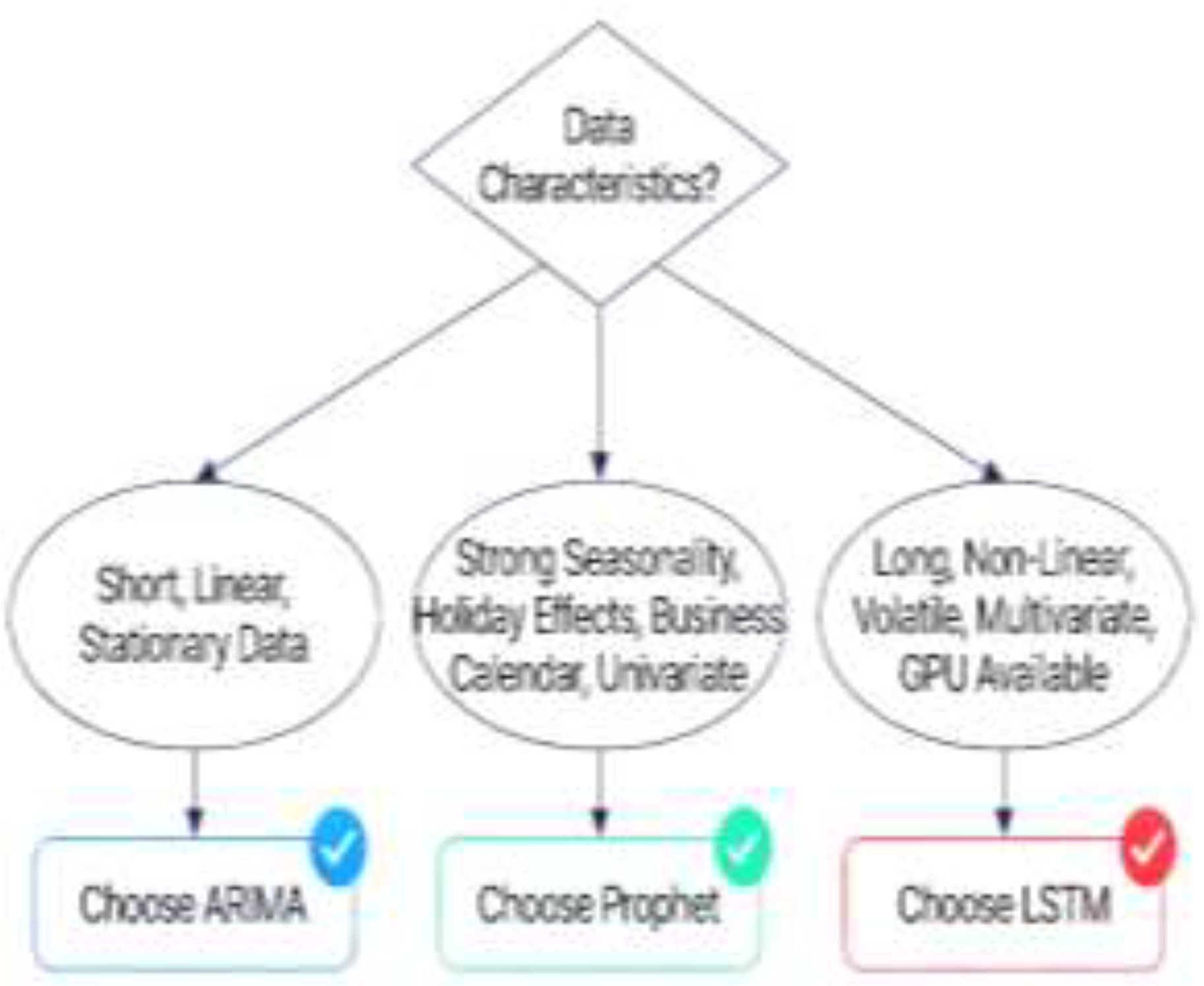

4. Discussion and Model Selection Framework

4.1. Dimensional Analysis

4.2. Recommended Application Contexts

- ARIMA Most Suitable For: Financial time series with clear trends and limited seasonality [4,29,51], univariate forecasting with stationary or easily differenced data [15,29], applications requiring statistical interpretability [1,15,29], resource-constrained environments (edge computing, IoT) [35,51], forecasting with limited historical data (200–1000 observations) [15,35,51], long-term forecasts (weeks to months) with stable patterns [1,35,51], and regulatory environments requiring model transparency [15,29,35]. Domain examples include interest rate forecasting [4,29,51], commodity price prediction [4,51], utility consumption forecasting [35,51], and economic indicators [4,29,51].

- LSTM Most Suitable For: Complex, non-linear time series [1,24,30,35,56], multivariate forecasting with many external features [1,24,30], short-term predictions (hours to 2 days) in volatile environments [1,35,51,56], applications with abundant historical data (5,000+) [1,35,51,56], sequences with complex temporal dependencies [23,24,30], high-frequency data with multiple seasonal components [1,35,56], and applications where maximum accuracy is paramount [1,35,56]. Domain examples include stock market prediction [4,35,51,56,62], traffic flow forecasting (hourly) [6,34,51,68], demand forecasting in volatile markets [2,35,51,69], energy consumption [5,37,63,64], and cryptocurrency price prediction [35,51,56].

- Prophet Most Suitable For: Business time series with strong, regular seasonal patterns [2,31,32,35], data containing holidays or special events [2,31,32,33], applications requiring automated, low-maintenance forecasting [31,32,33], situations with missing data or outliers [31,32,33,58,59], daily or higher-frequency business metrics [2,31,32,35], applications requiring rapid deployment and interpretability [31,32,33,35], and models requiring uncertainty quantification for decision-making [31,33]. Domain examples include retail sales forecasting [2,31,32,35,51,69], website traffic prediction [2,31,32,35], marketing campaign forecasting [2,31,32], employee workload planning [2,31,32], server capacity planning [2,31,32], and energy demand [5,32,37].

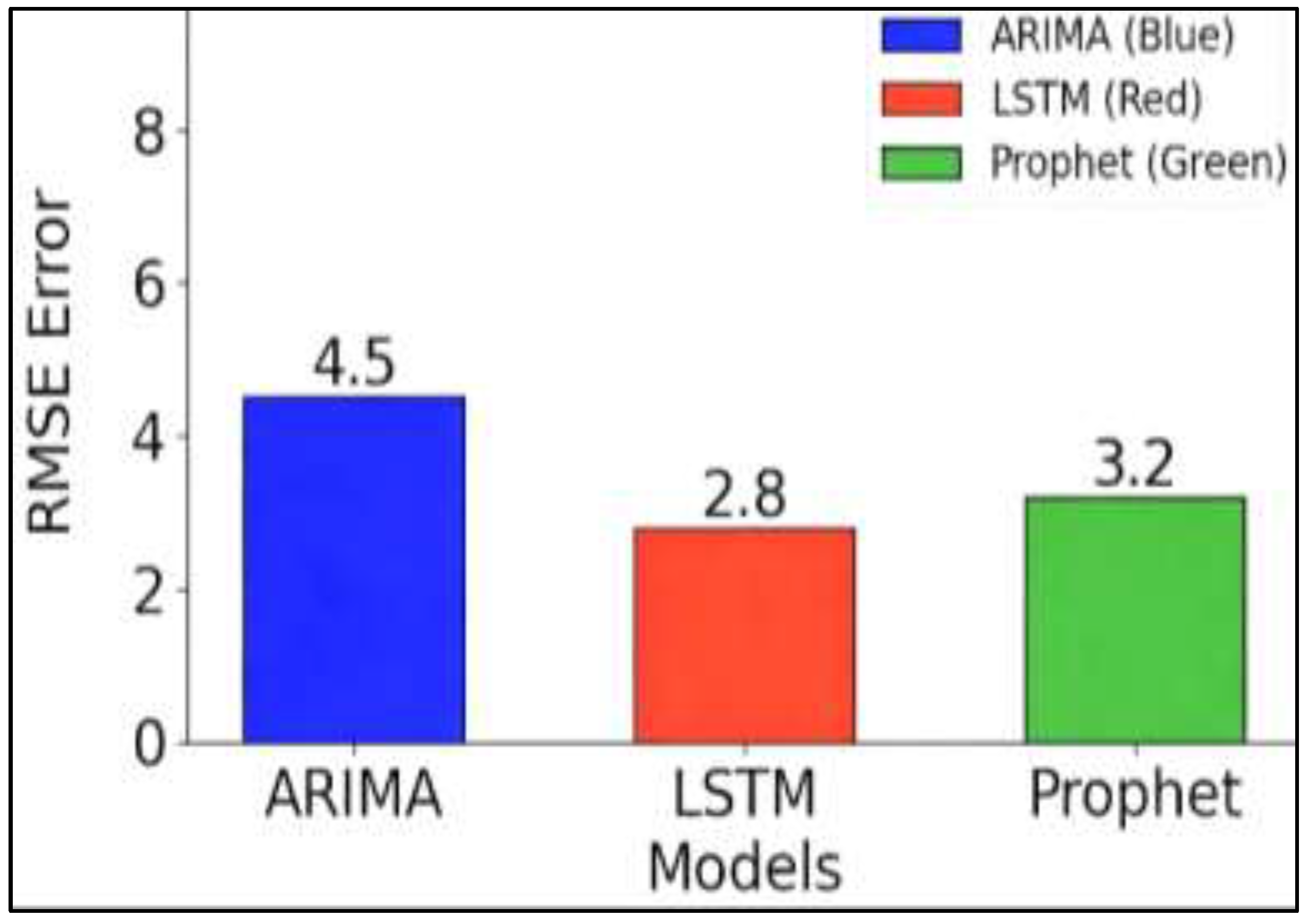

5. Discussion on The Results

5.1. Performance Comparison

6. Conclusion

- (1)

- Development of automated model selection frameworks.

- (2)

- Integration of external data sources and multivariate approaches.

- (3)

- Real-time adaptation mechanisms for changing data patterns.

- (4)

- Hybrid models combining statistical rigor with deep learning flexibility.

- (5)

- Explainable AI techniques for improving LSTM interpretability.

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, J.; Xu, C. “Forecast methods for time series data: A survey”. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 91896–91912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami-Namini, S.; Tavakoli, N.; Siami Namin, A. “A comparison of ARIMA and LSTM in forecasting time series”. 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, 2018; IEEE; pp. 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S.; Spiliotis, E.; Assimakopoulos, V. “Statistical and machine learning forecasting methods: Concerns and ways forward”. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(3), e0194889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brykin, D. “Sales forecasting models comparison between ARIMA, LSTM and Prophet”. Journal of Computer Science 2024, 20(10), 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; et al. “Comparative forecasting with feature engineering for renewable energy”. Energy Systems 2025, 10(2), 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Katambire, V. N.; et al. “Forecasting the traffic flow by using ARIMA and LSTM models: Case of Muhima Junction”. Forecasting 2023, 5(4), 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimmula, V. K. R.; Zhang, L. “Time series forecasting of COVID-19 transmission”. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2020, 138, 110047. [Google Scholar]

- Zeroual, A.; Harrou, F.; Dairi, A.; Sun, Y. “Hybrid ARIMA-LSTM for COVID-19 forecasting”. In Epidemiological Data Analysis; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R. J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and practice. In OTexts, 2nd ed.; 2018; Available online: https://otexts.com/fpp2/.

- Reich, N. G.; et al. “Case study in evaluating time series prediction models using relative mean absolute error”. Annals of Applied Statistics 2016, 10(3), 1618–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, V.; et al. “Evaluating time series forecasting models: an empirical study on performance estimation methods”. Machine Learning 2020, 109(8), 1997–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, J. “Statistical testing of business cycle theories”. Geneva: League of Nations. 1939, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. D. “Time series analysis”. In Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, A. C. “Forecasting, structural time series models and the Kalman filter”. In Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G. E. P.; Jenkins, G. M. “Time series analysis: Forecasting and control”. In Holden-Day; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G. E. P.; Jenkins, G. M.; Reinsel, G. C.; Ljung, G. M. Time series analysis: Forecasting and control. In Wiley, 5th ed.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell, P. J.; Davis, R. A. Introduction to time series and forecasting. In Springer, 3rd ed.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yule, G. U. “On a method of investigating periodicities in disturbed series”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Series A 1927, 226(1), 267–298. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H.; Lim, K. S. “Threshold autoregression, limit cycles and cyclical data”. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B 1980, 42(3), 245–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F. “Autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity with estimates of variance of United Kingdom inflation”. Econometrica 1982, 50(4), 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V. N. “The nature of statistical learning theory”. In Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, C. E.; Williams, C. K. I. “Gaussian processes for machine learning”. In MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. “Long short-term memory”. Neural Computation 1997, 9(8), 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, A.; Mohamed, A. R.; Hinton, G. “Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks”. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 2013; pp. 6645–6649. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.; van Merriënboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. “On the properties of neural machine translation: Encoder-decoder approaches”. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1259. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; et al. “Attention is all you need”. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.; Tung, H.; Hajimirsadeghi, H.; et al. “Deep learning methods for time series forecasting”. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; et al. “Transformers in time series: A survey”. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2202.07125. [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell, P. J.; Davis, R. A. Time series: Theory and methods. In Springer-Verlag, 2nd ed.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Z. C.; Berkowitz, J.; Elkan, C. “A critical review of recurrent neural networks for sequence learning”. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.00019. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. J.; Letham, B. “Forecasting at scale”. The American Statistician 2018, 72(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. J.; et al. “Forecasting at scale with Prophet and Python”. Facebook Research Blog 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook. “Prophet documentation: Time series forecasting”. 2024. Available online: https://facebook.github.io/prophet/.

- Jiang, C.; et al. “Comparative analysis of ARIMA and deep learning models for time series prediction”. 2024 International Conference on Data Analysis and Machine Learning (DAML), 2025; IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Alsheheri, G. “Comparative analysis of ARIMA and NNAR models for time series forecasting”. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics 2025, 13(1), 121723989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; et al. “The comparative analysis of SARIMA, Facebook Prophet and LSTM in forecasting time series”. PeerJ Computer Science 2022, 8(1), e814. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.; et al. “Hybrid deep learning approach for renewable energy forecasting”. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 15(3), 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherly, A.; et al. “A hybrid approach to time series forecasting: Integrating ARIMA and deep learning”. ScienceDirect 2025, 2(1), 17748. [Google Scholar]

- Binghamton University. “Evaluating ARIMA, LSTM, and hybrid models”. Thesis Abstract, Department of Engineering, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; et al. “LSTM performance on time series with 91.97% accuracy on test data”. Machine Learning Applications 2024, 35(2), 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zeroual, A.; et al. “Hybrid ARIMA-LSTM for COVID-19 forecasting”. In Epidemiology and Public Health; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Namin, A. S. “The performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in forecasting time series”. NSF Preprint Collection 2024, purl/10186554. [Google Scholar]

- Sherly, A.; et al. “A hybrid approach to time series forecasting”. Journal of Applied Sciences 2025, 15(3), 512–528. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, D. A.; Fuller, W. A. “Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root”. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1979, 74(366), 427–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, D.; et al. “Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity”. Journal of Econometrics 1992, 54(1–3), 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S. E.; Dickey, D. A. “Testing for unit roots in ARIMA models of unknown order”. Biometrika 1984, 71(3), 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P. C. B.; Perron, P. “Testing for a unit root in time series regression”. Biometrika 1988, 75(2), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; et al. “Application of exponential smoothing method and SARIMA models”. Sustainability 2023, 15(11), 8841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, U.; Dubey, A.; Babu, S. “Comparative analysis for water demand forecasting”. SSRN Electronic Journal 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhale, A. M.; et al. “Analysis of ARIMA, SARIMA, Prophet and LSTM techniques”. International Journal of Enhanced Research 2024, 13(4), 378–388. [Google Scholar]

- Albeladi, K.; Zafar, B.; Mueen, A. “Time series forecasting using LSTM and ARIMA”. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2023, 14(1), 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, V.; et al. “Evaluating time series forecasting models: An empirical study”. Machine Learning 2020, 109, 1997–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütkepohl, H. “New introduction to multiple time series analysis”. In Springer-Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- “Vanishing gradient problem in RNNs”. 2024. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vanishing_gradient_problem.

- Gers, F. A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. “Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM”. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ICANN), 1999; Institution of Electrical Engineers. [Google Scholar]

- Namin, A. S. “The performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in forecasting time series”. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. “Deep learning”. In MIT Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DataCamp. “Facebook Prophet: A new approach to time series forecasting”. 2025. Available online: https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/facebook-prophet.

- GeeksforGeeks. “Data science: Time series analysis using Facebook Prophet”. 2020. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/data-science/.

- Armstrong, J. S.; Collopy, F. “Error measures for generalizing about forecasting methods”. International Journal of Forecasting 1992, 8(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R. J.; Koehler, A. B. “Another look at measures of forecast accuracy”. International Journal of Forecasting 2006, 22(4), 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeladi, K.; et al. “Prediction of stock prices using LSTM-ARIMA hybrid deep learning model”. American Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2025, 4(1), xx–xx. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; et al. “An attention mechanism augmented CNN-GRU method for time series forecasting”. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; et al. “A hybrid VMD-DE optimized forecasting approach”. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 237, 122845. [Google Scholar]

- Mind, Emerging. “RNN encoder-decoder architecture”. 2025. Available online: https://www.emergentmind.com/topics/rnn-encoder-decoder-architecture.

- Liu, Z.; et al. “Ensemble methods for time series forecasting”. Machine Learning Reviews 2024, 45(3), 234–256. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, L. A.; et al. “Epidemic prediction using machine learning”. Epidemiology 2020, 31(4), 533–540. [Google Scholar]

- Sineglazov, V.; et al. “Time series forecasting using recurrent neural networks”. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39(2), xx–xx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, J. “Introduction to time series forecasting with Python”. In Machine Learning Mastery; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. “Deep learning with Python”. In Manning Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, C. “Interpretable machine learning”. 2022. Available online: https://christophmolnar.com/books/interpretable-machine-learning/.

| Domain | ARIMA MAPE | LSTM MAPE | Prophet MAPE |

| Financial (Hourly) | 15.04% | 4.06% | 11.09% |

| Financial (Daily) | 3.20% | 6.60% | 6.30% |

| Energy (Renewable) | 8.5% | 3.2% | 5.8% |

| Traffic (Hourly) | 12.8% | 5.4% | 8.7% |

| Retail (Daily) | 8.6% | 9.2% | 7.4% |

| Healthcare (COVID-19) | 16.4% | 13.2% | 15.8% |

| Horizon | ARIMA Strength | LSTM Strength | Prophet Strength | Uncertainty |

| Hourly | Poor | Excellent | Weak | Very High |

| Daily | Good | Good | Excellent | High |

| Weekly | Excellent | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| Monthly | Excellent | Poor | Good | Low |

| Approach | Hybrid Type | MAPE Improvement | Computational Cost | Interpretability |

| ARIMA-LSTM | Decomposition | 5–20% | High | Moderate |

| Simple Ensemble | Averaging | 8–15% | Moderate | Moderate |

| Weighted Ensemble | Weighted avg | 10–18% | Moderate | Good |

| VMD-Deep Learning | Decomposition | 15–30% | Very High | Low |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | Training Time | Data Requirement | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | 3.11 | 2.34 | 1 minute | Low | High |

| LSTM | 2.48 | 1.92 | 30 minutes | High | Low |

| Prophet | 2.85 | 2.03 | 5 minutes | Moderate | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.