Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

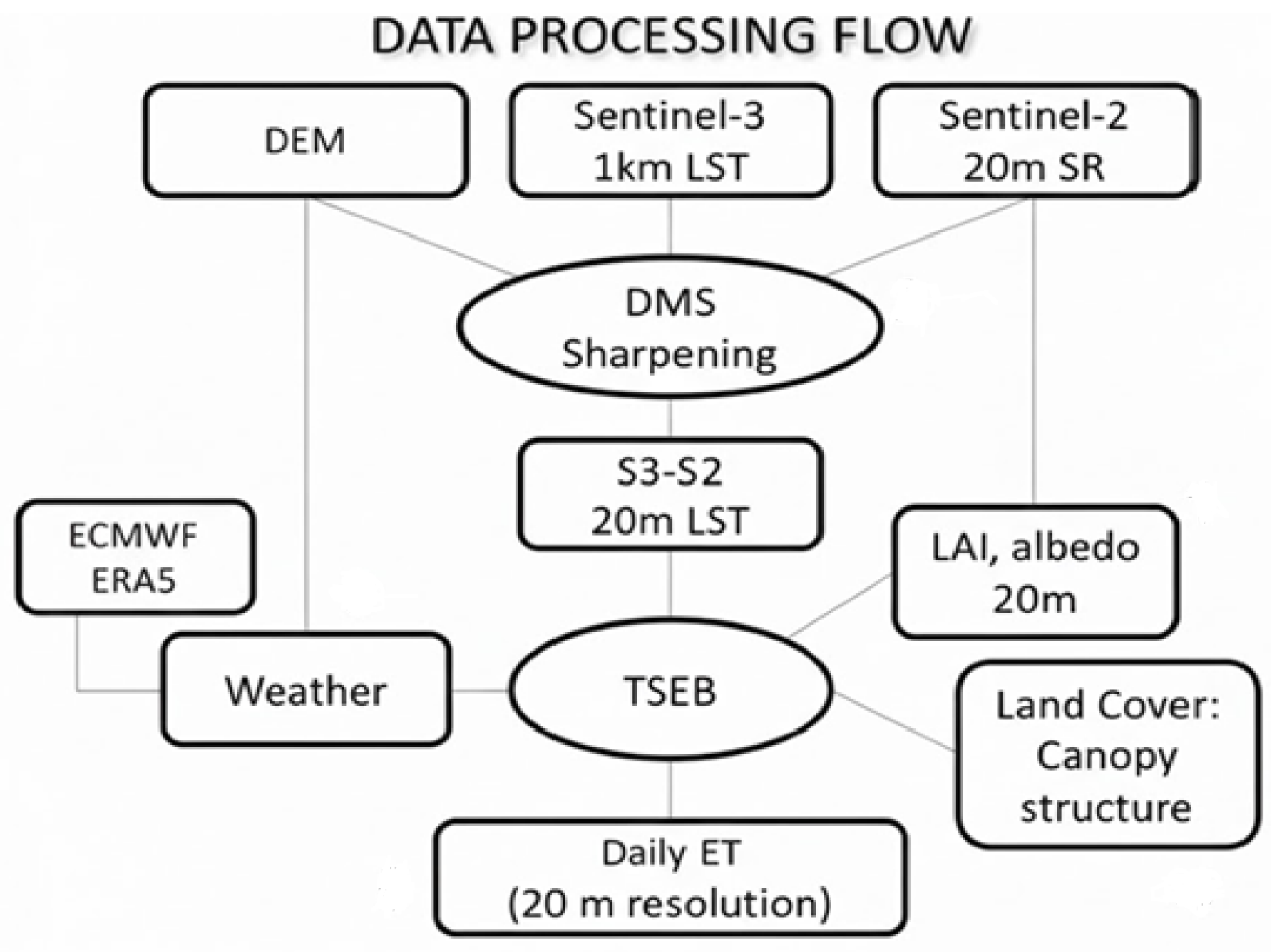

2.1. SEN-ET (Copernicus)

2.2. Use of WRF

2.3. Validation with the Use of Large Weighing Lysimeter ET Measurements

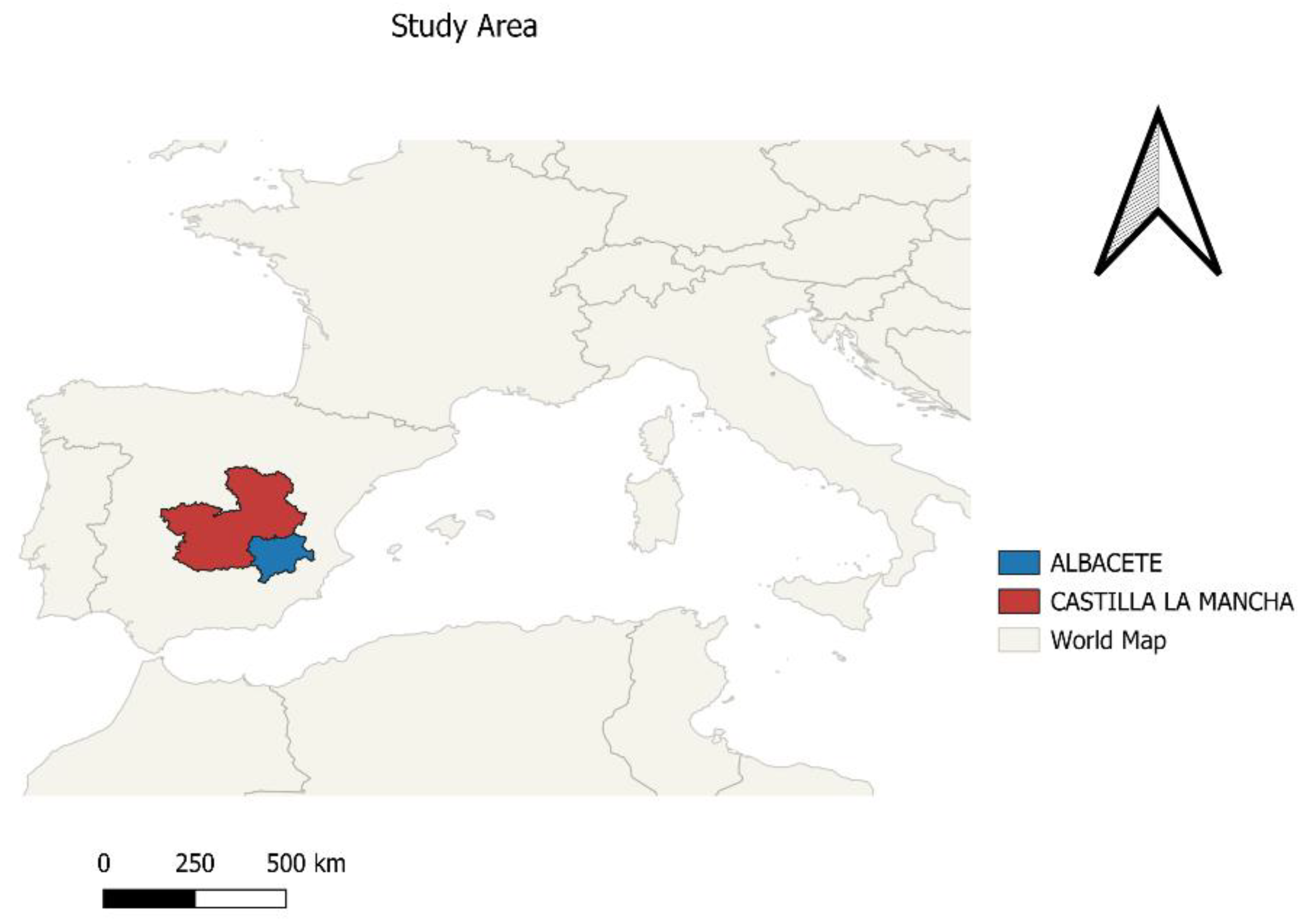

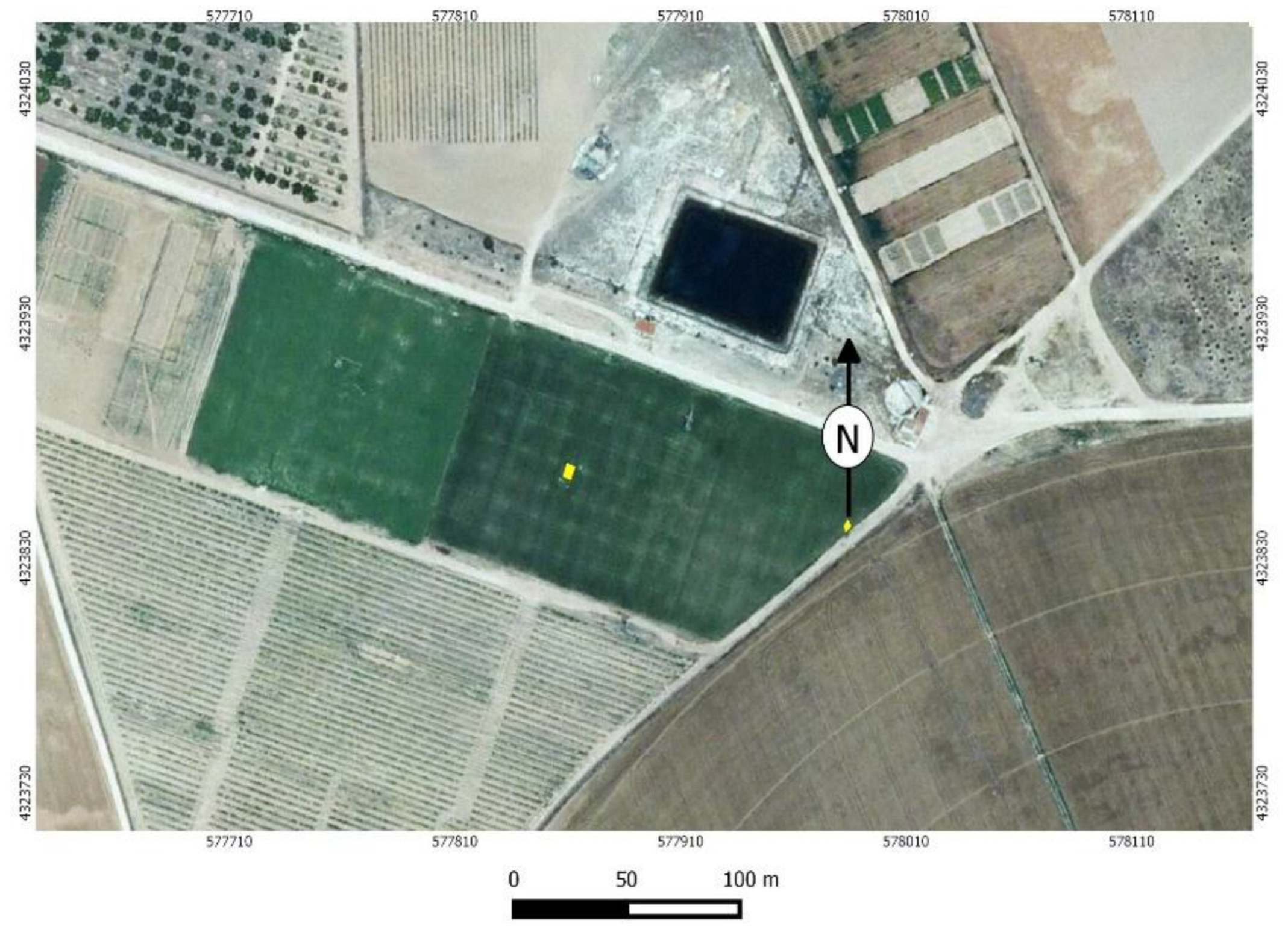

3. Study Area

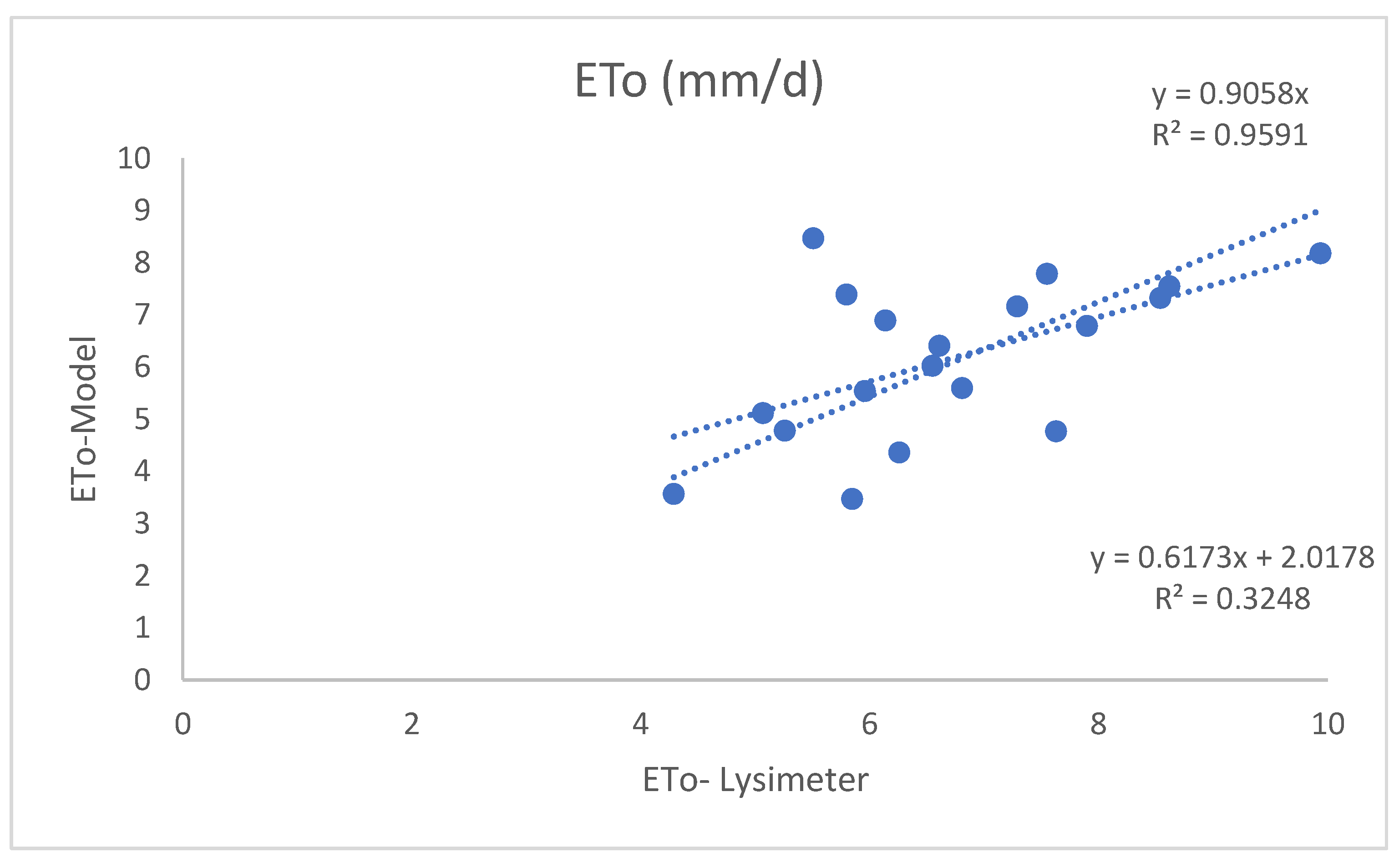

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calera, A.; Campos, I.; Osann, A.; D’Urso, G.; Menenti, M. Remote Sensing for Crop Water Management: From ET Modelling to Services for the End Users. Sensors (Switzerland) 2017, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, P.H.; Chavez, J.L.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Evett, S.R.; Howell, T.A.; Tolk, J.A. ET Mapping for Agricultural Water Management: Present Status and Challenges. Irrig. Sci. 2008, 26, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Rodríguez, B.A.; Ontiveros-Capurata, R.E.; González-Sánchez, A.; Ruíz-Álvarez, O. Comparative Analysis of Actual Evapotranspiration Values Estimated by METRIC Model Using LOCAL Data and EEFlux for an Irrigated Area in Northern Sinaloa, Mexico. Heliyon 2024, e34767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, P.H.; Chävez, J.; Howell, T.A.; Marek, T.H.; New, L.L. Surface Energy Balance Based Evapotranspiration Mapping in the Texas High Plains. Sensors 2008, 8, 5186–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.G.; Tasumi, M.; Morse, A.; Trezza, R.; Wright, J.L.; Bastiaanssen, W.; Kramber, W.; Lorite, I.; Robison, C.W. Satellite-Based Energy Balance for Mapping Evapotranspiration with Internalized Calibration (METRIC)—Applications. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 2007, 133, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Allen, R.G.; Smith, M.; Raes, D. Crop Evapotranspiration Estimation with FAO56: Past and Future. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 147, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sehgal, V.K.; Dhakar, R.; Neale, C.M.U.; Goncalves, I.Z.; Rani, A.; Jha, P.K.; Das, D.K.; Mukherjee, J.; Khanna, M.; et al. Estimation of ET and Crop Water Productivity in a Semi-Arid Region Using a Large Aperture Scintillometer and Remote Sensing-Based SETMI Model. Water (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.K. Estimating Actual Evapotranspiration from Widely Available Meteorological Data with a Hybrid CNN–LSTM. Agric. Water Manag. 2026, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibbi, L.; Chiesi, M.; Pieri, M.; Bartolini, G.; Grifoni, D.; Gozzini, B.; Maselli, F. Assessment of Three Remote Sensing Methods for Estimating Actual Evapotranspiration in a Mediterranean Region. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2026, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Allen, R.G.; Morse, A.; Kustas, W.P. Use of Landsat Thermal Imagery in Monitoring Evapotranspiration and Managing Water Resources. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.A.; Mantovani, E.C.; Bufon, V.B.; Fernandes-Filho, E.I. Improving Actual Evapotranspiration Estimates through an Integrated Remote Sensing and Cutting-Edge Machine Learning Approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pang, Z.; Xue, F.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, T.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, J. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Variations in Evapotranspiration and Its Driving Factors Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study of the Heihe River Basin. Remote Sens. (Basel). 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Ning, J.; Yu, R.; Fan, J.; Kan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; et al. Satellite-Based PT-SinRH Evapotranspiration Model: Development and Validation from AmeriFlux Data. Remote Sens. (Basel). 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Li, C.; He, Y.; Tan, J.; Niu, W.; Cui, Y.; Yang, H. PML_30: A High Resolution (30 m) Estimates of Evapotranspiration Based on Remote Sensing Model with Application in an Arid Region. J. Hydrol. (Amst). 2024, 131862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, W.S.; Paredes, P.; Basto, J.; Pôças, I.; Pacheco, C.A.; Paço, T.A. Estimating Evapotranspiration of Rainfed Winegrapes Combining Remote Sensing and the SIMDualKc Soil Water Balance Model. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Kiss, N.É.; Buday-Bódi, E.; Magyar, T.; Cavazza, F.; Gentile, S.L.; Abdullah, H.; Tamás, J.; Fehér, Z.Z. Precision Estimation of Crop Coefficient for Maize Cultivation Using High-Resolution Satellite Imagery to Enhance Evapotranspiration Assessment in Agriculture. Plants 2024, 13, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, B.; Nielsen, K. Validation of Sentinel-6MF Based Lake Levels—An Assessment with in Situ Data and Other Satellite Altimetry Data. Advances in Space Research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, N.; Bargaoui, Z.; Jaafar, A. Ben; Mannaerts, C.M. Comparison of Actual Evapotranspiration Assessment by Satellite-Based Model SEBS and Hydrological Model BBH in Northern Tunisia; 2024; pp. 471–476. [Google Scholar]

- Zipper, A.S.; Kastens, J.; Foster, T.; Wilson, B.; Melton, F. Estimating Irrigation Water Use from Remotely Sensed Evapotranspiration Data: Accuracy and Uncertainties across Spatial Scales 2024, 1–52.

- Saxena, D. Uncorrected Proof Spatiotemporal Trends and Evapotranspiration Estimation Using an Improvised SEBAL Convergence Method for the Semi-Arid Region of Western Rajasthan, India. 2024, 00, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Peng, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, L.; et al. Remote Sensing of Environment Spatial-Temporal Patterns of Land Surface Evapotranspiration from Global Products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 304, 114066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Song, L.; Zhao, L.; Tao, S. A Comparison of Different Machine Learning Methods to Reconstruct Daily Evapotranspiration Time Series Estimated by Thermal–Infrared Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. (Basel). 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, H.; Alsenjar, O.; Scholar, G. Developing a New ANN Model to Estimate Daily Actual Evapotranspiration Using Limited Climatic Data and Remote Sensing Techniques. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jia, L.; Lu, J.; Jiang, M. A New Evapotranspiration-Based Drought Index for Flash Drought Identification and Monitoring; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tasumi, M. Estimating Evapotranspiration Using METRIC Model and Landsat Data for Better Understandings of Regional Hydrology in the Western Urmia Lake Basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 226, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Resources Research. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 1969, 5, 2–2. [CrossRef]

- Zamani Losgedaragh, S.; Rahimzadegan, M. Evaluation of SEBS, SEBAL, and METRIC Models in Estimation of the Evaporation from the Freshwater Lakes (Case Study: Amirkabir Dam, Iran). J. Hydrol. (Amst). 2018, 561, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Meneti, M.; Feddes, R.A.; Holtslag, a a M. A Remote Sensing Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL){{}{{}{}}{{}{$}{}}{{}{}}{}}\backslashbackslashbackslashbackslashbackslash{\{}\backslash{\{}{\}}\backslashbackslash{\{}\backslash{\{}{\}}{\{}\backslash{\}}{\}}\backslashbackslashbackslash{\{. J. Hydrol. 1998, 212–213, 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaanssen, W.; Pelgrum, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Moreno, J.F. A Remote Sensing Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL).: Part 2: Validation. J. Hydrol. (Amst). 1998, 212, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z. The Surface Energy Balance System (SEBS) for Estimation of Turbulent Heat Fluxes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2002, 6, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliotopoulos, M.; Holden, N.M.; Loukas, A. Mapping Evapotranspiration Coefficients in a Temperate Maritime Climate Using the Metric Model and Landsat TM. Water (Switzerland) 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Trezza, R.; Kilic, A.; Tasumi, M.; Li, H. Sensitivity of Landsat-Scale Energy Balance to Aerodynamic Variability in Mountains and Complex Terrain. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madugundu, R.; Al-Gaadi, K.A.; Tola, E.K.; Hassaballa, A.A.; Patil, V.C. Performance of the METRIC Model in Estimating Evapotranspiration Fluxes over an Irrigated Field in Saudi Arabia Using Landsat-8 Images. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 6135–6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.M.; Kustas, W.P.; Humes, K.S. Source Approach for Estimating Soil and Vegetation Energy Fluxes in Observations of Directional Radiometric Surface Temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 77, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Kustas, W.P.; Norman, J.M.; Diak, G.T.; Hain, C.R.; Gao, F.; Yang, Y.; Knipper, K.R.; Xue, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. A Brief History of the Thermal IR-Based Two-Source Energy Balance (TSEB) Model—Diagnosing Evapotranspiration from Plant to Global Scales. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, T.; Fischer, M.; Nieto, H.; Kowalska, N.; Jocher, G.; Homolová, L.; Burchard-Levine, V.; Žalud, Z.; Trnka, M. Evaluation of the METRIC and TSEB Remote Sensing Evapotranspiration Models in the Floodplain Area of the Thaya and Morava Rivers. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliotopoulos, M.; Loukas, A. Hybrid Methodology for the Estimation of Crop Coefficients Based on Satellite Imagery and Ground-Based Measurements. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-González, A.; Kjaersgaard, J.; Trooien, T.; Hay, C.; Ahiablame, L. Estimation of Crop Evapotranspiration Using Satellite Remote Sensing-Based Vegetation Index. Advances in Meteorology 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCEE A RTIFICIAL NEURAL N ETWORKS IN HYDROLOGY. By the ASCE Task Committee on Application of Artificial Neural Networks in Hydrology. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2000, 5, 124–137. [CrossRef]

- ASCE Task Committee on Application of Artificial Neural Networks in Hydrology. Task Committee on Application of Artificial Neural Networks in Hydrology, Artificial Neural Networks in Hydrology. II:Hydrologic Application. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2000, 5, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Raghuwanshi, N.S.; Singh, R. Artificial Neural Networks Approach in Evapotranspiration Modeling: A Review. Irrig. Sci. 2011, 29, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzinski, R.; Nieto, H.; Sandholt, I.; Karamitilios, G. Modelling High-Resolution Actual Evapotranspiration through Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Data Fusion. Remote Sens. (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruescas, A.B.; Peters, M. SNAP-S3TBX Collocation Tutorial. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guzinski, R.; Nieto, H. Evaluating the Feasibility of Using Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Satellites for High-Resolution Evapotranspiration Estimations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 221, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlon, C.; Berruti, B.; Buongiorno, A.; Ferreira, M.H.; Féménias, P.; Frerick, J.; Goryl, P.; Klein, U.; Laur, H.; Mavrocordatos, C.; et al. The Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) Sentinel-3 Mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintala, S.; Harmya, T.S.; Kambhammettu, B.V.N.P.; Moharana, S.; Duvvuri, S. Modelling High-Resolution Evapotranspiration in Fragmented Croplands from the Constellation of Sentinels. Remote Sens. Appl. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Kustas, W.P.; Anderson, M.C. A Data Mining Approach for Sharpening Thermal Satellite Imagery over Land. Remote Sens. (Basel). 2012, 4, 3287–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, D.; D’Amato, C.; Bartkowiak, P.; Azimi, S.; Castelli, M.; Rigon, R.; Massari, C. Evaluation of Remotely-Sensed Evapotranspiration Datasets at Different Spatial and Temporal Scales at Forest and Grassland Sites in Italy. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry, MetroAgriFor 2022—Proceedings, 2022; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; pp. 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Guzinski, R.; Nieto, H.; Ramo Sánchez, R.; Sánchez, J.M.; Jomaa, I.; Zitouna-Chebbi, R.; Roupsard, O.; López-Urrea, R. Improving Field-Scale Crop Actual Evapotranspiration Monitoring with Sentinel-3, Sentinel-2, and Landsat Data Fusion. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzinski, R.; Nieto, H.; Sanchez, J.M.; Lopez-Urrea, R.; Boujnah, D.M.; Boulet, G. Utility of Copernicus-Based Inputs for Actual Evapotranspiration Modeling in Support of Sustainable Water Use in Agriculture. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 11466–11484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duzenli, E.; Yucel, I.; Pilatin, H.; Yilmaz, M.T. Evaluating the Performance of a WRF Initial and Physics Ensemble over Eastern Black Sea and Mediterranean Regions in Turkey. Atmos. Res. 2021, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solbakken, K.; Birkelund, Y.; Samuelsen, E.M. Evaluation of Surface Wind Using WRF in Complex Terrain: Atmospheric Input Data and Grid Spacing. Environmental Modelling and Software 2021, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Hu, X.; Shi, L.; Min, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y. Evapotranspiration Partitioning by Integrating Eddy Covariance, Micro-Lysimeter and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Observations: A Case Study in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.N.; Hunsaker, D.J.; Sanchez, C.A.; Saber, M.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Anderson, R. Satellite-Based NDVI Crop Coefficients and Evapotranspiration with Eddy Covariance Validation for Multiple Durum Wheat Fields in the US Southwest. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 239, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martí, P.; González-Altozano, P.; López-Urrea, R.; Mancha, L.A.; Shiri, J. Modeling Reference Evapotranspiration with Calculated Targets. Assessment and Implications. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 149, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Urrea, R.; Martínez-Molina, L.; de la Cruz, F.; Montoro, A.; González-Piqueras, J.; Odi-Lara, M.; Sánchez, J.M. Evapotranspiration and Crop Coefficients of Irrigated Biomass Sorghum for Energy Production. Irrig. Sci. 2016, 34, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Urrea, R.; Sánchez, J.M.; de la Cruz, F.; González-Piqueras, J.; Chávez, J.L. Evapotranspiration and Crop Coefficients from Lysimeter Measurements for Sprinkler-Irrigated Canola. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercas, N.; Tziatzios, G.A.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Sarchani, S.; Faraslis, I.; Belaud, G.; Daudin, K.; Spiliotopoulos, M.; Sakellariou, S.; Alpanakis, N.; et al. Monitoring Satellite-Based Crop Irrigation Water Requirements for Maize, Cotton and Hay in Distinct Mediterranean Regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.M.; Galve, J.M.; Nieto, H.; Guzinski, R. Assessment of High-Resolution LST Derived from the Synergy of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 in Agricultural Areas. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps | Description |

| 1 | Sentinel imagery Acquisition (Sentinel-2–Sentinel-3) |

| 2 | Image pre-processing—Sentinel-3 resampling |

| 3 | Retrieval of Digital Elevation Model (DEM) |

| 4 | Land use/land cover maps generation |

| 5 | Leaf reflection and green vegetation fraction estimation |

| 6 | Aerodynamic roughness assessment |

| 7 | Land Surface Temperature (LST) estimation |

| 8 | WRF meteorological data acquisition |

| 9 | WRF adaptation to the study area |

| 10 | Long-wave irradiance Estimation |

| 11 | Net shortwave radiation estimation using biophysical parameters and meteorological data |

| 12 | Land surface energy fluxes estimation |

| 13 | Final ET values computation |

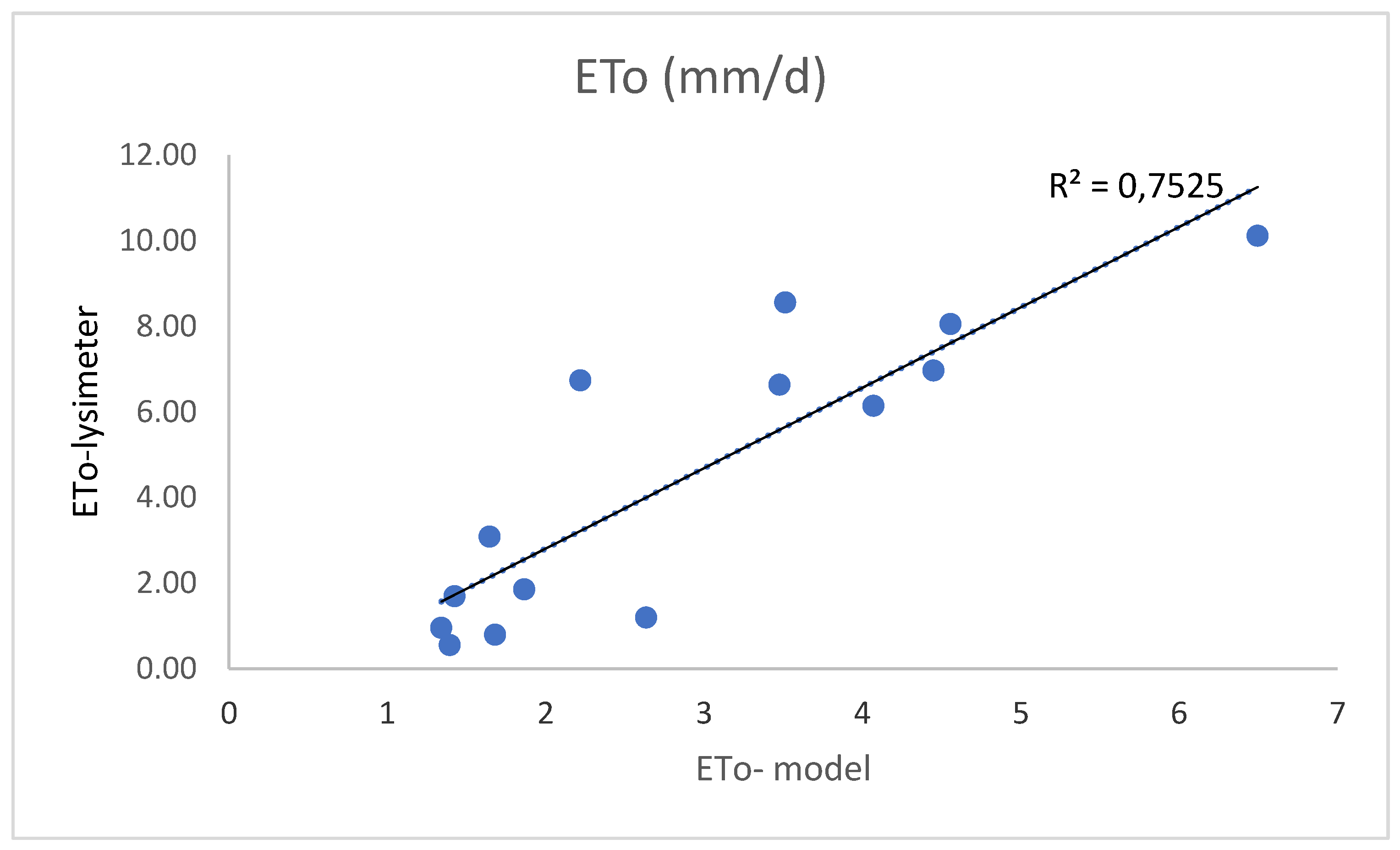

| Date | Year |

ET0 proposed (mm/d) |

ET0 Lysimeter (mm/d) |

ET0 FAO PM (mm/d) |

| 13-05 | 2021 | 4,78 | 5,26 | 5,00 |

| 18-05 | 2021 | 5,54 | 5,96 | 5,75 |

| 02-06 | 2021 | 6,89 | 6,14 | 5,80 |

| 27-06 | 2021 | 7,39 | 5,80 | 5,61 |

| 02-07 | 2021 | 7,16 | 7,29 | 6,89 |

| 07-07 | 2021 | 7,78 | 7,55 | 7,70 |

| 12-07 | 2021 | 4,76 | 7,63 | 7,23 |

| 17-07 | 2021 | 6,40 | 6,61 | 6,73 |

| 22-07 | 2021 | 8,18 | 9,94 | 9,97 |

| 27-07 | 2021 | 6,02 | 6,55 | 6,82 |

| 01-08 | 2021 | 7,54 | 8,62 | 8,57 |

| 06-08 | 2021 | 3,47 | 5,85 | 6,25 |

| 16-08 | 2021 | 8,46 | 5,51 | 5,41 |

| 21-08 | 2021 | 7,32 | 8,54 | 8,32 |

| 31-08 | 2021 | 6,78 | 7,90 | 7,76 |

| 05-09 | 2021 | 5,59 | 6,81 | 6,94 |

| 20-09 | 2021 | 4,36 | 6,26 | 5,81 |

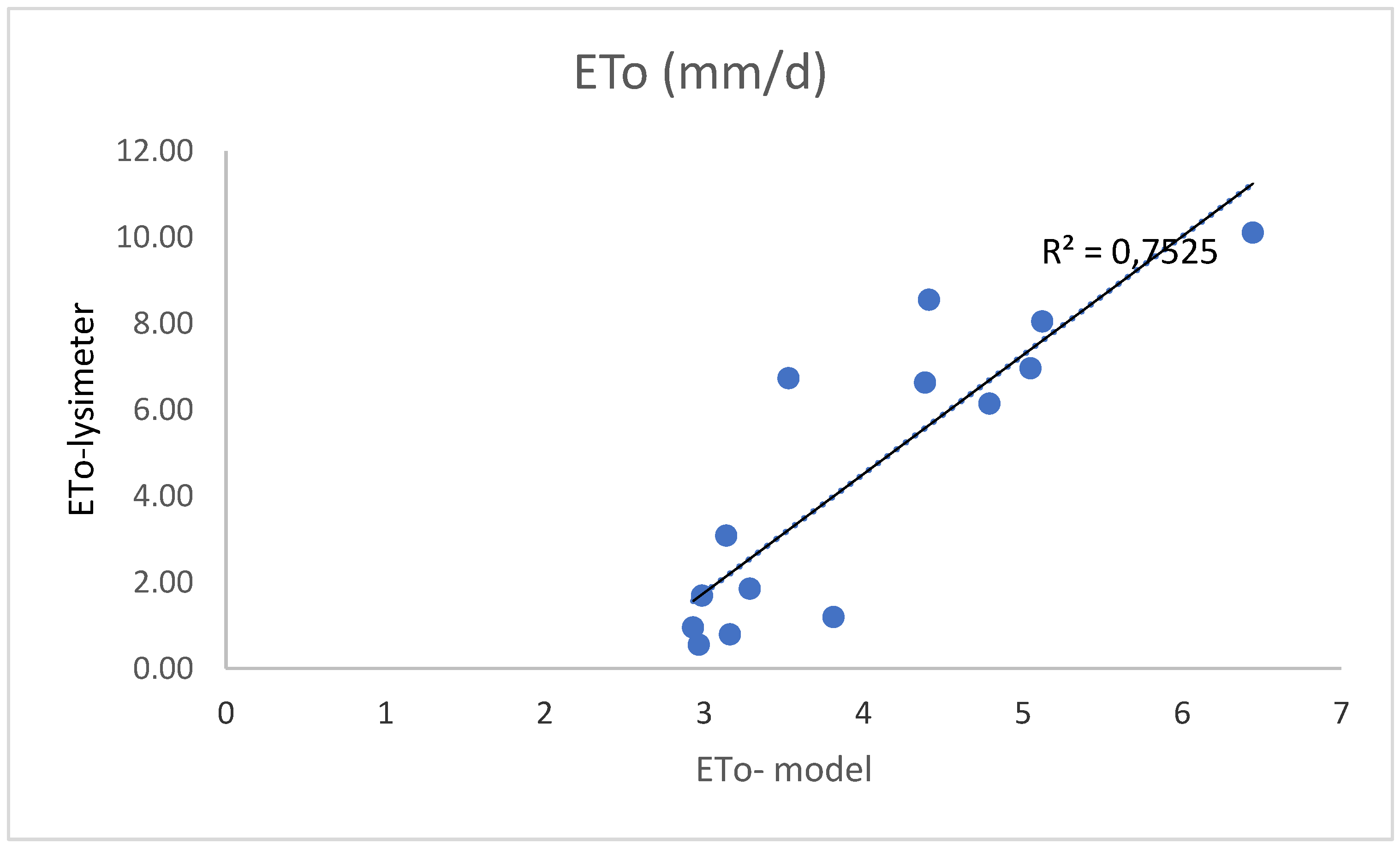

| Date | Year |

ET0 proposed (mm/d) |

ET0 Lysimeter (mm/d) |

ET0 FAO PM (mm/d) |

| 17-06 | 2022 | 7,17 | 10,11 | 9,39 |

| 07-07 | 2022 | 2,45 | 6,73 | 7,13 |

| 17-17 | 2022 | 5,03 | 8,05 | 8,16 |

| 22-07 | 2022 | 4,71 | 8,28 | 8,28 |

| 29-07 | 2022 | 4,50 | 6,14 | 6,33 |

| 30-09 | 2022 | 1,59 | 3,08 | 3,16 |

| 23-01 | 2023 | 1,48 | 0,95 | 1,37 |

| 28-01 | 2023 | 1,86 | 0,79 | 0,87 |

| 02-02 | 2023 | 1,54 | 0,55 | 0,93 |

| 17-02 | 2023 | 2,06 | 1,85 | 1,87 |

| 22-02 | 2023 | 2,91 | 1,19 | 1,64 |

| 04-03 | 2023 | 1,57 | 1,69 | 1,50 |

| 01-08 | 2023 | 3,88 | 8,55 | 8,14 |

| 03-08 | 2023 | 3,84 | 6,63 | 6,76 |

| 06-08 | 2023 | 4,91 | 6,96 | 6,84 |

| Statistical Indices | R2 | MBE (mm/d) |

RMSE (mm/d)2 |

| 0.75 | -1,61 | 2,64 |

| Statistical Indices | R2 | MBE (mm/d) |

RMSE (mm/d)2 |

| 0.75 | -0,52 | 2,48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).