Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

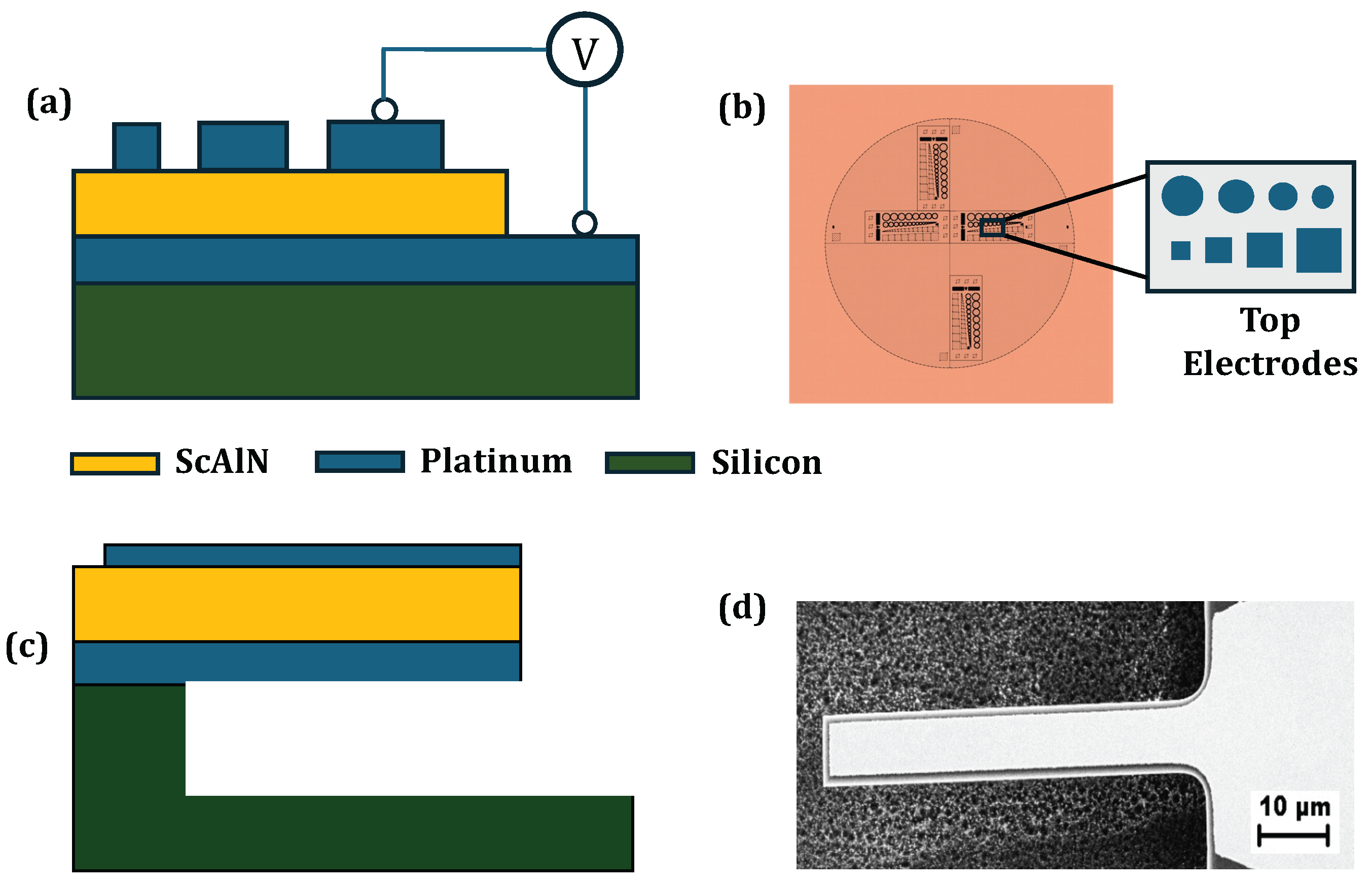

2. Deposition & Characterization Procedure

3. Results

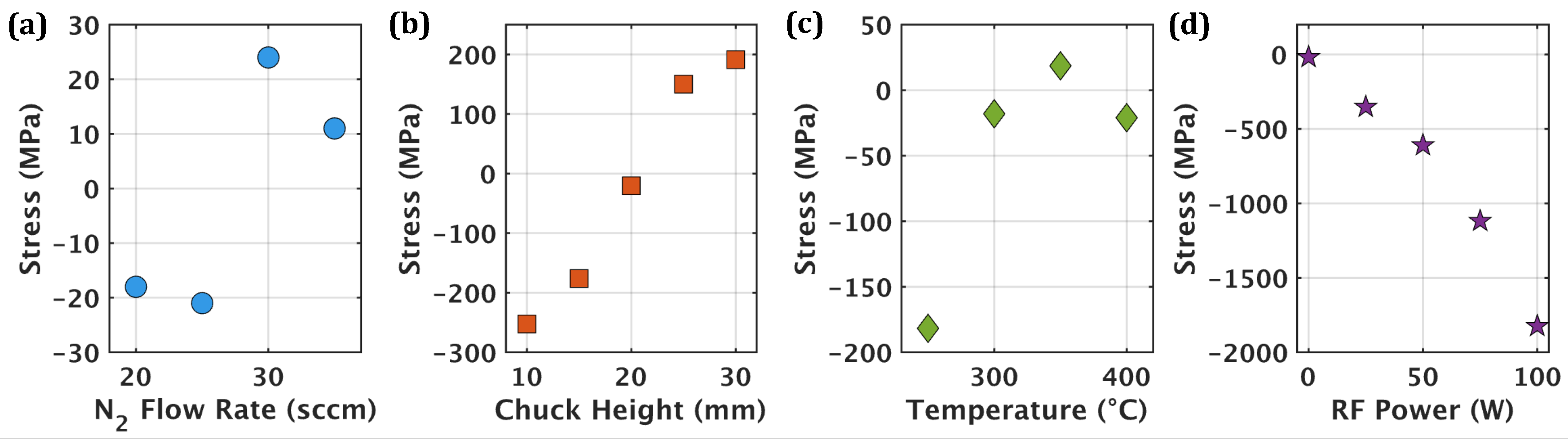

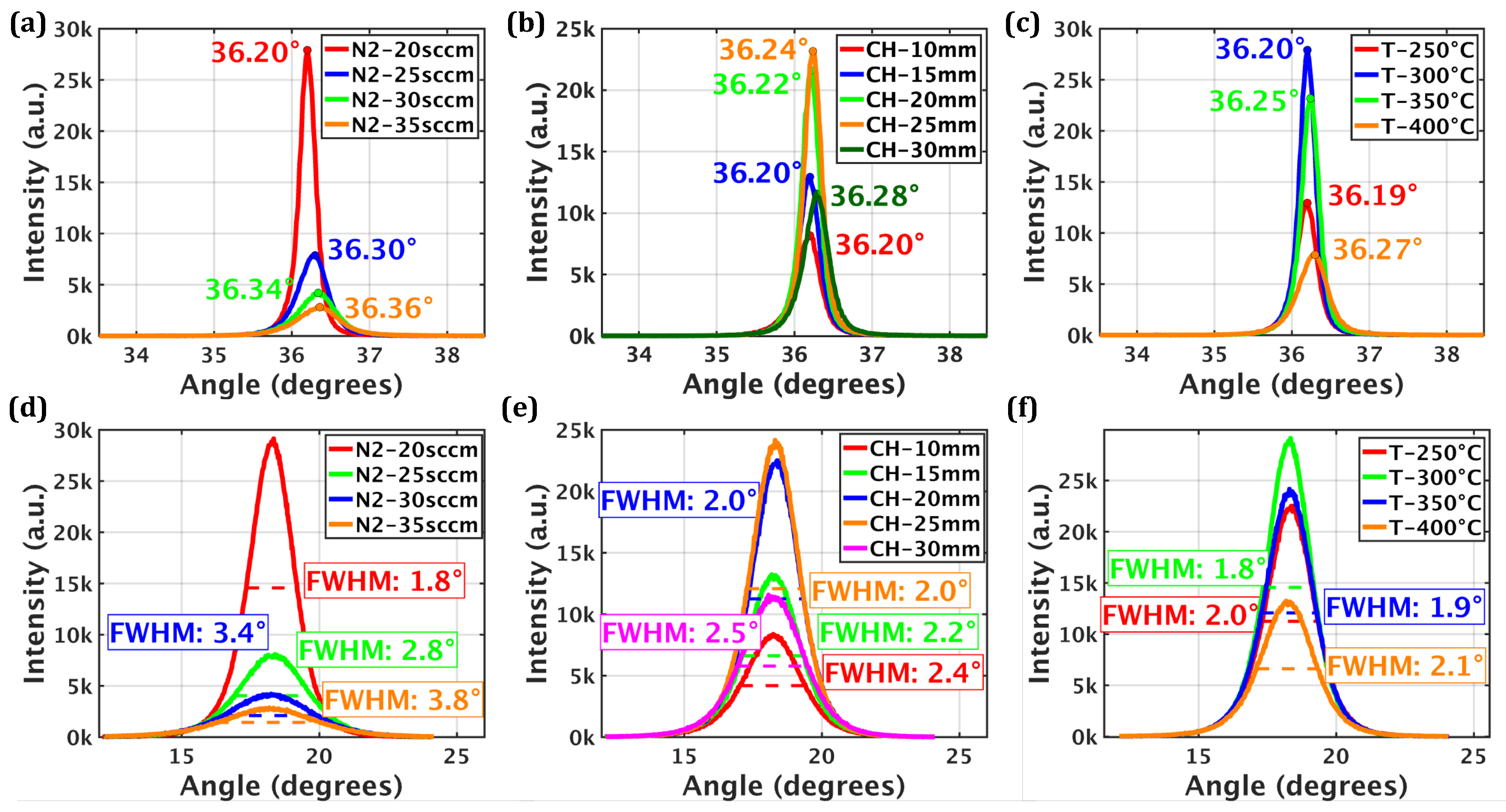

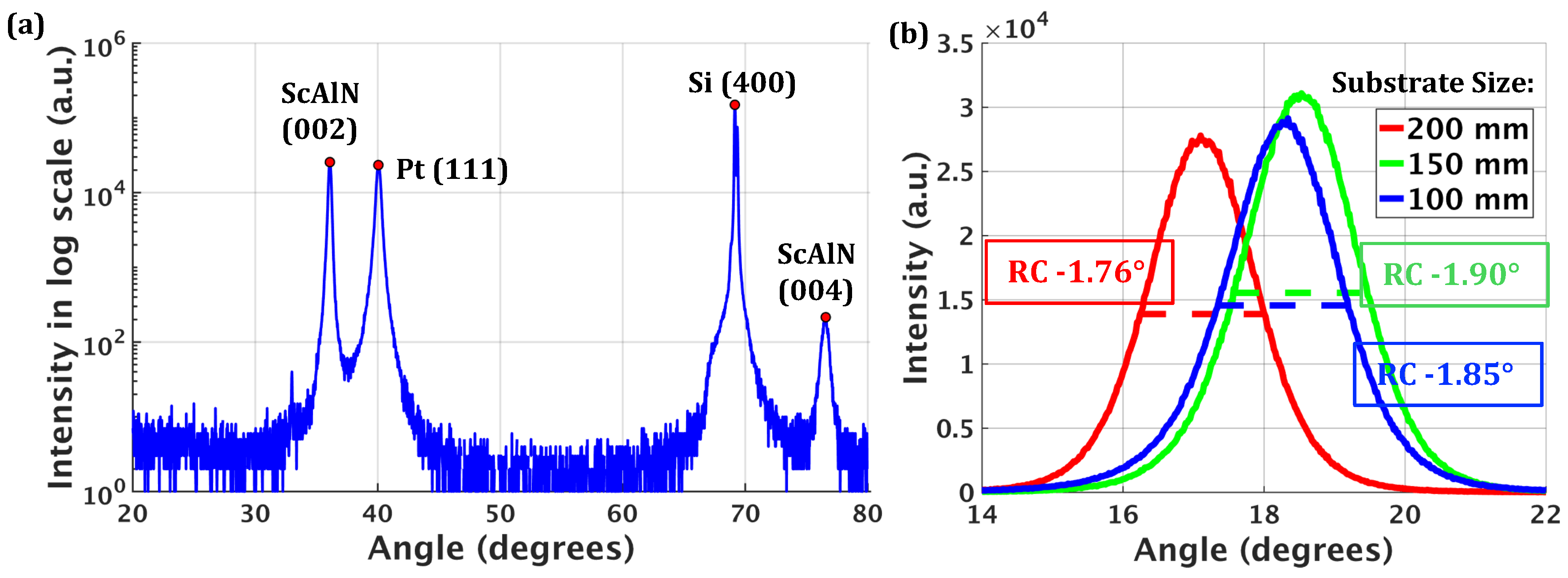

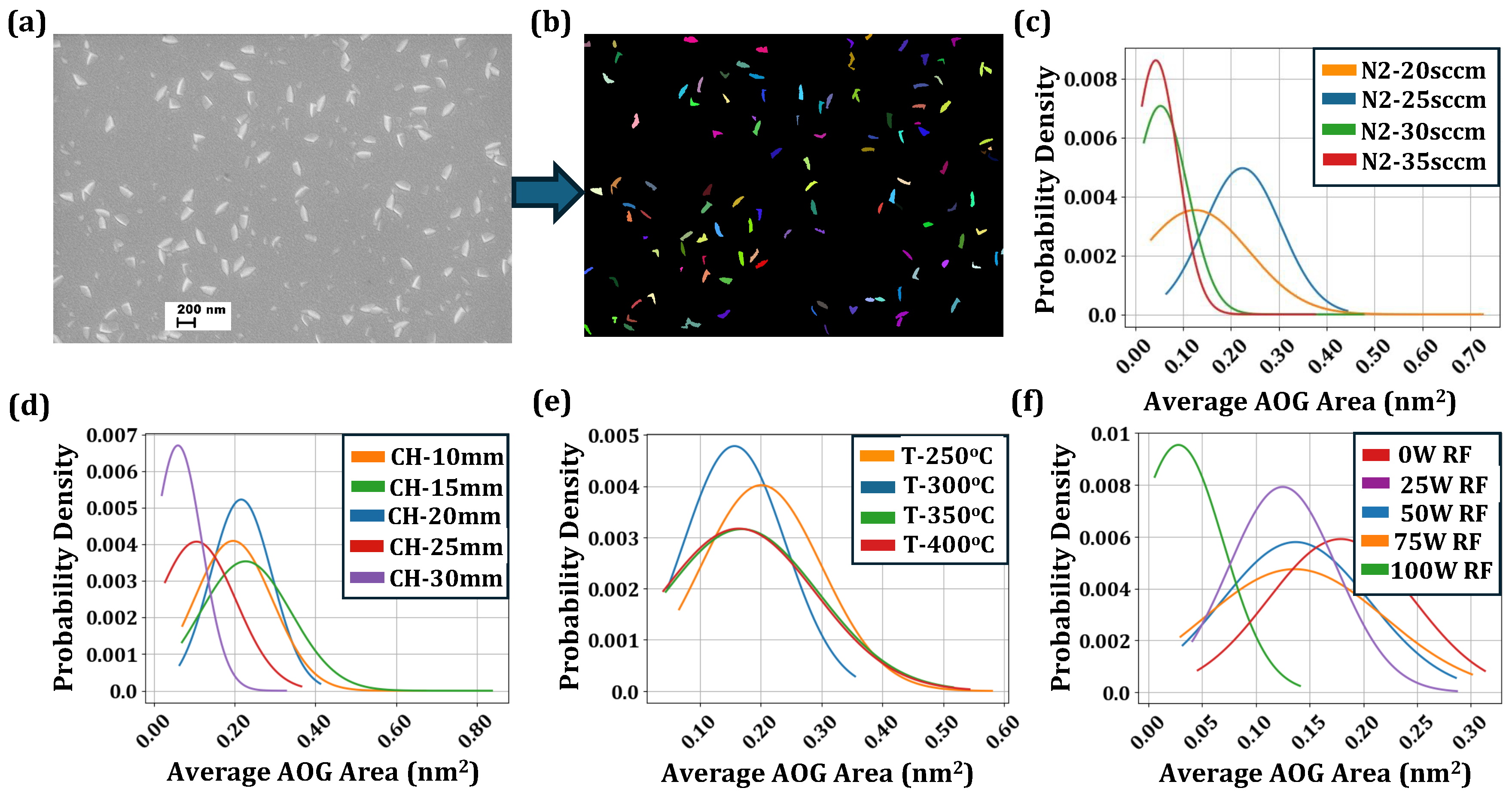

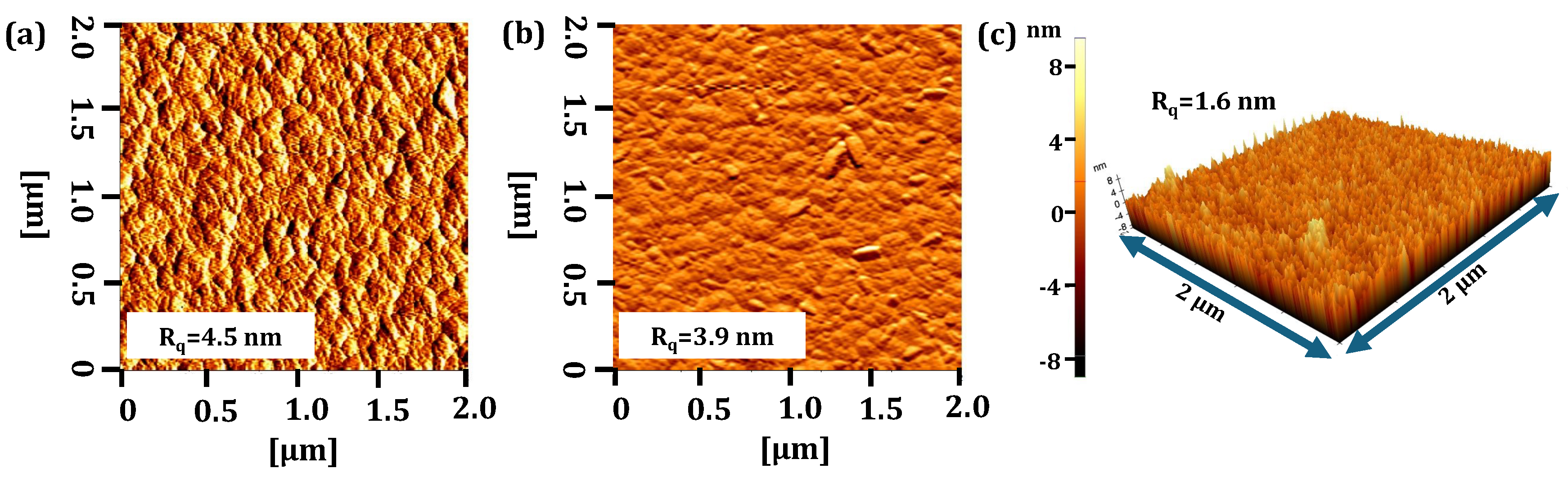

3.1. Process Optimization

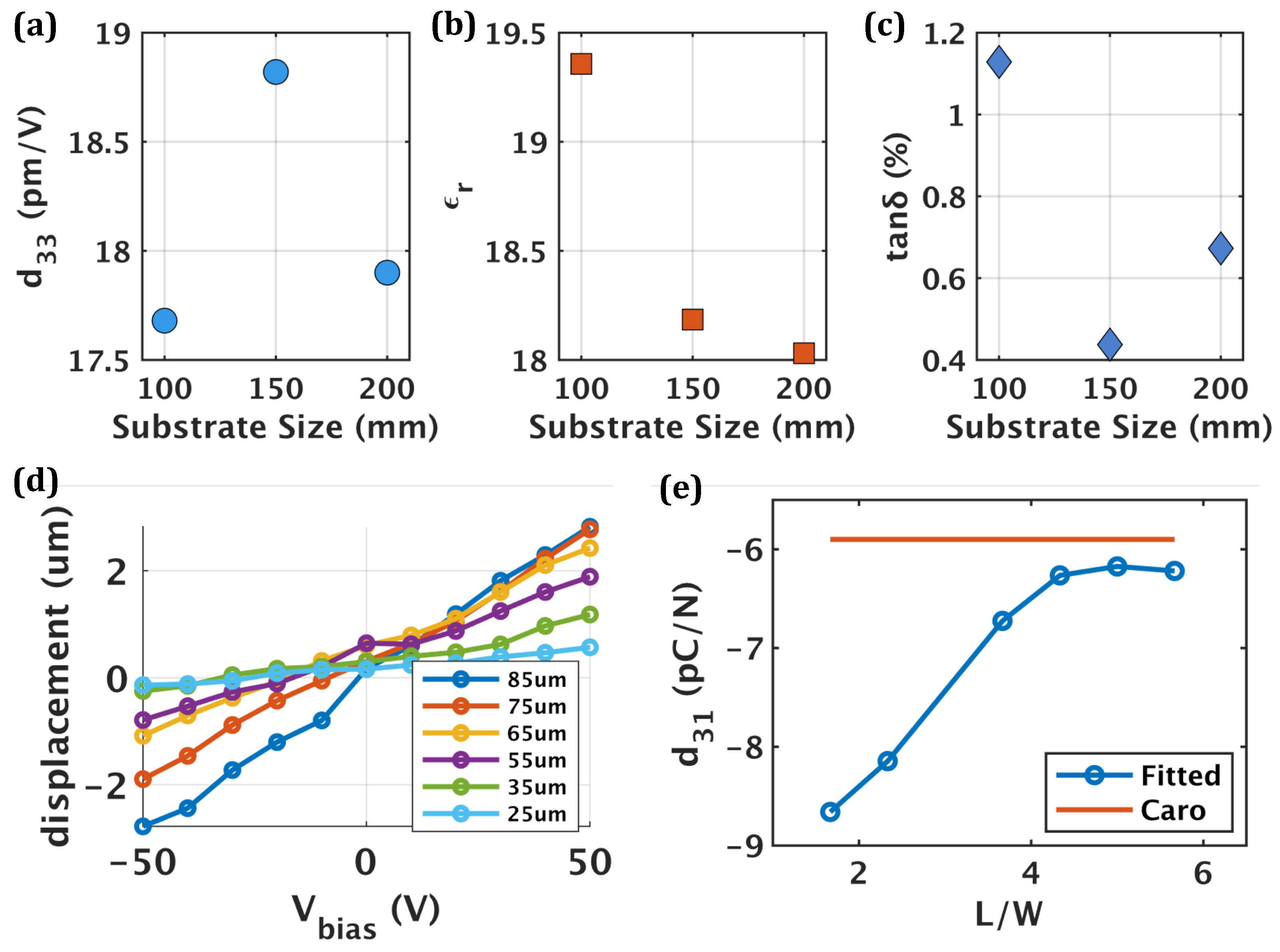

3.2. Dielectric Properties

3.3. Measurement of Piezoelectric Strain Coefficients

3.3.1. Longitudinal Piezoelectric Coefficient ()

3.3.2. Transverse Piezoelectric Coefficient ()

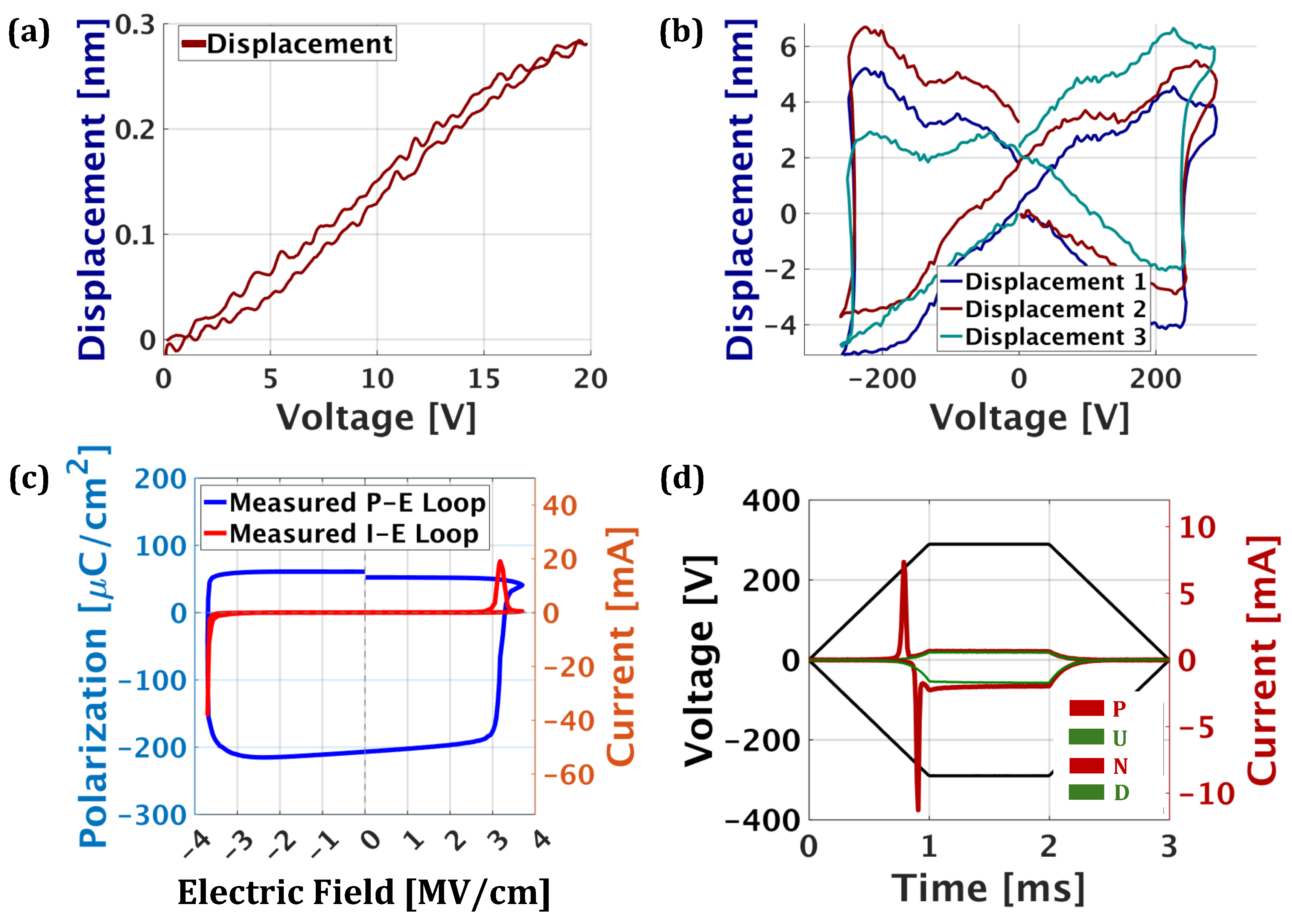

3.4. Ferroelectric Properties

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muralt, P.; Polcawich, R.G.; Trolier-McKinstry, S. Piezoelectric Thin Films for Sensors, Actuators, and Energy Harvesting. MRS Bulletin 2009, 34, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, A.; Zhang, M. Piezoelectric Thin Film Materials for Acoustic MEMS Devices. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Advanced Control Circuits and Systems (ACCS) & 2019 5th International Conference on New Paradigms in Electronics & information Technology (PEIT), 2019; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed, F.B.; Giribaldi, G.; Venditti, A.; Saha, K.; Simeoni, P.; Qian, Z.; Rinaldi, M. Enhanced Infrared Sensing With 30Acoustic Delay Lines Integrated with Metamaterial Absorbers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control Joint Symposium (UFFC-JS), 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.Y. Acoustic wave devices based on piezoelectric/ferroelectric thin films for high-frequency communication systems and sensing applications. Ceramics International The 13th Asian Meeting on Ferroelectrics jointly with the 13th Asian Meeting on Electroceramics, 2024; 50, pp. 52051–52058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.; Barrera, O.; Ravi, N.; Matto, L.; Saha, K.; Dasgupta, S.; Campbell, J.; Kramer, J.; Kwon, E.; Hsu, T.H.; et al. Solidly Mounted Scandium Aluminum Nitride on Acoustic Bragg Reflector Platforms at 14–20 GHz. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2025, 72, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, O.; Ravi, N.; Saha, K.; Dasgupta, S.; Campbell, J.; Kramer, J.; Kwon, E.; Hsu, T.H.; Cho, S.; Anderson, I.; et al. 18 GHz Solidly Mounted Resonator in Scandium Aluminum Nitride on SiO2/Ta2O5 Bragg Reflector. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2024, 33, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littrell, R.; Grosh, K. Modeling and Characterization of Cantilever-Based MEMS Piezoelectric Sensors and Actuators. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2012, 21, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralt, P. Recent Progress in Materials Issues for Piezoelectric MEMS. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2008, 91, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnaminy, A.F.; Ou, M.; Mansour, R.R. PCM-Based Reconfigurable Acoustic Resonators and Filters: For Potential Use in RF Front-End Applications. IEEE Microwave Magazine 2024, 25, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, L.; Saha, K.; Simeoni, P.; Colombo, L.; Rinaldi, M. 18 GHz Filters based on Cross-Sectional Lamé Mode Resonators (CLMRs). In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), 2025; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizian, R.; Rais-Zadeh, M.; Ayazi, F. Effect of phonon interactions on limiting the f.Q product of micromechanical resonators. In Proceedings of the TRANSDUCERS 2009 - 2009 International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference, 2009; pp. 2131–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.T.; Shah, M.A.; Lee, D.G.; Hur, S. A Review of the Recent Applications of Aluminum Nitride-Based Piezoelectric Devices. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 58779–58795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.; Talley, K.R.; Gorai, P.; Mangum, J.S.; Zakutayev, A.; Brennecka, G.L.; Stevanović, V.; Ciobanu, C.V. Enhanced piezoelectric response of aln via crn alloying. Physical Review Applied 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingqvist, G.; Tasnádi, F.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Birch, J.; Arwin, H.; Hultman, L. Increased electromechanical coupling in w - scxal1-xn. Applied Physics Letters 2010, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matloub, R.; Hadad, M.; Mazzalai, A.; Chidambaram, N.; Moulard, G.; Sandu, C.S.; Metzger, T.H.; Muralt, P. Piezoelectric al1-xscxn thin films: a semiconductor compatible solution for mechanical energy harvesting and sensors. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, R.H.; Tang, Z.; D’Agati, M. Doping of aluminum nitride and the impact on thin film piezoelectric and ferroelectric device performance. 2020 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startt, J.; Quazi, M.; Sharma, P.; Vazquez, I.; Poudyal, A.; Jackson, N.; Dingreville, R. Unlocking AlN Piezoelectric Performance with Earth-Abundant Dopants. Advanced Electronic Materials 2023, 9, 2201187. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/aelm.202201187. [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.; Tabaru, T.; Nishikubo, K.; Teshigahara, A.; Kano, K. Preparation of scandium aluminum nitride thin films by using scandium aluminum alloy sputtering target and design of experiments. Journal of the Ceramic Society of Japan 2010, 118, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, N.; Ding, A.; Urban, D.F.; Lu, Y.; Kirste, L.; Feil, N.M.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Ambacher, O. Experimental determination of the electro-acoustic properties of thin film AlScN using surface acoustic wave resonators. Journal of Applied Physics 2019, 126, 075106. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.5094611/15232477/075106_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Beaucejour, R.; Roebisch, V.; Kochhar, A.; Moe, C.G.; Hodge, M.D.; Olsson, R.H. Controlling Residual Stress and Suppression of Anomalous Grains in Aluminum Scandium Nitride Films Grown Directly on Silicon. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2022, 31, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnádi, F.; Alling, B.; Höglund, C.; Wingqvist, G.; Birch, J.; Hultman, L.; Abrikosov, I.A. Origin of the Anomalous Piezoelectric Response in Wurtzite ScxAl1-xN Alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 137601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, M.A.; Zhang, S.; Riekkinen, T.; Ylilammi, M.; Moram, M.A.; Lopez-Acevedo, O.; Molarius, J.; Laurila, T. Piezoelectric coefficients and spontaneous polarization of ScAlN. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2015, 27, 245901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.; Kano, K.; Teshigahara, A. Influence of growth temperature and scandium concentration on piezoelectric response of scandium aluminum nitride alloy thin films. Applied Physics Letters 2009, 95, 162107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Reusch, M.; Kurz, N.; Ding, A.; Christoph, T.; Kirste, L.; Lebedev, V.; Žukauskaitė, A. Surface Morphology and Microstructure of Pulsed DC Magnetron Sputtered Piezoelectric AlN and AlScN Thin Films. physica status solidi (a) 2018, 215, 1700559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, K.; Niitsu, K.; Anggraini, S.A.; Kageura, T.; Uehara, M.; Yamada, H.; Akiyama, M. Enhancing the piezoelectric performance of nitride thin films through interfacial engineering. Materials Today 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.; Kamohara, T.; Kano, K.; Teshigahara, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kawahara, N. Enhancement of Piezoelectric Response in Scandium Aluminum Nitride Alloy Thin Films Prepared by Dual Reactive Cosputtering. Advanced Materials 2009, 21, 593–596. Available online: https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/adma.200802611. [CrossRef]

- cang Yang, J.; qin Meng, X.; tao Yang, C.; jun Fu, W. Influence of N2/Ar-flow ratio on crystal quality and electrical properties of ScAlN thin film prepared by DC reactive magnetron sputtering. Applied Surface Science 2013, 282, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, L.; Qu, Y.; Gu, X.; Luo, T.; Xie, Y.; Wei, M.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, C. Preparation, Characterization, and Application of AlN/ScAlN Composite Thin Films. Micromachines 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X.; Qin, X.; Wang, F.; Tang, Y.; Yeoh, K.H.; Chew, K.H.; Sun, X. Deposition, Characterization, and Modeling of Scandium-Doped Aluminum Nitride Thin Film for Piezoelectric Devices. Materials 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Corkovic, S.; Dorey, R.; Whatmore, R.W. Comparative measurements of piezoelectric coefficient of PZT films by berlincourt, interferometer, and vibrometer methods. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2006, 53, 2287–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Mardilovich, P.; Mason, A.; Roelofs, A.; Schmitz-Kempen, T.; Tiedke, S. Electrode size dependence of piezoelectric response of lead zirconate titanate thin films measured by double beam laser interferometry. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 103, 132904. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.4821948/14283000/132904_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Mardilovich, P.; Schmitz-Kempen, T.; Tiedke, S. Concurrent wafer-level measurement of longitudinal and transverse effective piezoelectric coefficients (d33,f and e31,f) by double beam laser interferometry. Journal of Applied Physics 2018, 123, 014103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Varghese, B.; Liu, P.P.; Lin, H.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y. Measurement and Analysis of Longitudinal and Transversal Effective Piezoelectric Coefficients (d33,f and e31,f) in 100 nm-500 nm Sc0.3Al0.7N films. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), sep 2023; pp. 1–4, ISSN 1948-5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, K.; Hirata, K.; Anggraini, S.A.; Akiyama, M.; Uehara, M.; Yamada, H. First-principles calculations of spontaneous polarization in ScAlN. Journal of Applied Physics 2021, 130, 024104. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0051557/13587437/024104_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, S.; Wolff, N.; Lofink, F.; Kienle, L.; Wagner, B. AlScN: A III-V semiconductor based ferroelectric. Journal of Applied Physics 2019, 125, 114103. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.5084945/15224058/114103_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.P.; Tang, X.G.; Sun, Q.J.; Chen, J.Y.; Jiang, Y.P.; Zhang, D.; Dong, H.F. Emerging ferroelectric materials ScAlN: applications and prospects in memristors. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 2802–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrich, R.; Bartsch, H.; Tonisch, K.; Jaekel, K.; Barth, S.; Bartzsch, H.; Glöß, D.; Delan, A.; Krischok, S.; Strehle, S.; et al. Investigation of ScAlN for piezoelectric and ferroelectric applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd European Microelectronics and Packaging Conference & Exhibition (EMPC), 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, D.; Musavigharavi, P.; Stach, E.A.; Olsson; Roy, I.; Jariwala, D. Aluminum scandium nitride-based metal–ferroelectric–metal diode memory devices with high on/off ratios. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 118, 202901. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0051940/13793378/202901_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Gund, V.; Davaji, B.; Lee, H.; Casamento, J.; Xing, H.G.; Jena, D.; Lal, A. Towards Realizing the Low-Coercive Field Operation of Sputtered Ferroelectric ScxAl1-xN. In Proceedings of the 2021 21st International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (Transducers), 2021; pp. 1064–1067, ISSN 2167-0021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D. Doping effects on the ferroelectric properties of wurtzite nitrides. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 122, 122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, P.; Wu, Y.; Hu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Mohanty, S.; Ma, T.; Ahmadi, E.; Mi, Z. Reconfigurable self-powered deep UV photodetectors based on ultrawide bandgap ferroelectric ScAlN. APL Materials 2022, 10, 121101. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apm/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0122943/16490925/121101_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Mu, S.; Xie, H.; Wang, T.; He, C.; Shen, M.; Liu, M.; Van de Walle, C.G.; Tang, H.X. Unveiling the Pockels coefficient of ferroelectric nitride ScAlN. 15, 9538. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.J.; Lee, J.S. Ferroelectric Transistors for Memory and Neuromorphic Device Applications. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2206864. Available online: https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/adma.202206864. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, K. CHARACTERIZATION OF SCANDIUM-DOPED ALUMINUM NITRIDE THIN FILMS FOR BULK ACOUSTIC WAVE RESONATORS; laurea: Politecnico di Torino, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stoney, G.G. The tension of metallic films deposited by electrolysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 1909, 82, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholander, C.; Tasnádi, F.; Abrikosov, I.A.; Hultman, L.; Birch, J.; Alling, B. Large piezoelectric response of quarternary wurtzite nitride alloys and its physical origin from first principles. Physical Review B 2015, 92, 174119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, M.; Boschker, H.; van Zalk, M.; Nguyen, M.; Nazeer, H.; Houwman, E.; Rijnders, G. The significance of the piezoelectric coefficient d31,eff determined from cantilever structures. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2012, 23, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S. Criterion for material selection in design of bulk piezoelectric energy harvesters. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control 2010, 57, 2610–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hake, A.E.; Kitsopoulos, P.; Grosh, K. Design of Piezoelectric Dual-Bandwidth Accelerometers for Completely Implantable Auditory Prostheses. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 13957–13965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirro, M.; Zhao, X.; Herrera, B.; Simeoni, P.; Rinaldi, M. Effect of Substrate-RF on Sub-200 nm Al0.7Sc0.3N Thin Films. Micromachines 2022, 13, 877. Number: 6; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Sinusía Lozano, M.; Pérez-Campos, A.; Reusch, M.; Kirste, L.; Fuchs, T.; Žukauskaitė, A.; Chen, Z.; Iriarte, G.F. Piezoelectric characterization of Sc0.26Al0.74N layers on Si (001) substrates. Materials Research Express 2018, 5, 036407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, S.; Wolff, N.; Krishnamurthy, G.; Petraru, A.; Bohse, S.; Lofink, F.; Chemnitz, S.; Kohlstedt, H.; Kienle, L.; Wagner, B. Identifying and overcoming the interface originating c-axis instability in highly Sc enhanced AlN for piezoelectric micro-electromechanical systems. Journal of Applied Physics 2017, 122, 035301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylbekova, M. Aluminum Nitride and Scandium-Doped Aluminum Nitride Materials and Devices for Beyond 6 GHz Communication. PhD thesis, Last updated. Copyright - Database copyright ProQuest LLC, 2022. ProQuest does not claim copyright in the individual underlying works. [Google Scholar]

- Sandu, C.S.; Parsapour, F.; Mertin, S.; Pashchenko, V.; Matloub, R.; LaGrange, T.; Heinz, B.; Muralt, P. Abnormal Grain Growth in AlScN Thin Films Induced by Complexion Formation at Crystallite Interfaces. physica status solidi (a) 2019, 216, 1800569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, B.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, N. Evaluation of the Impact of Abnormally Orientated Grains on the Performance of ScAlN-based Laterally Coupled Alternating Thickness (LCAT) Mode Resonators and Lamb Wave Mode Resonators. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), 2020; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, L.; Colombo, L.; Gubinelli, W.; Saha, K.; Simeoni, P.; Rinaldi, M. An Image Recognition Technique for The Quantitative Analysis of Abnormally Oriented Grains in Advanced Piezoelectric Material. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control Joint Symposium (UFFC-JS), 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Feng, B.; Dong, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Ren, T.; Luo, J.; Wang, D. Influence of Substrate Temperature on Structural Properties and Deposition Rate of AlN Thin Film Deposited by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Journal of Electronic Materials 2012, 41, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Li, W. Ferroelectricity and ferromagnetism of m-type lead hexaferrite. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2015, 98, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ting, J.; He, Y.; Fiagbenu, M.M.A.; Zheng, J.; Wang, D.; Frost, J.; Musavigharavi, P.; Esteves, G.; Kisslinger, K.; et al. Reconfigurable Compute-In-Memory on Field-Programmable Ferroelectric Diodes. Nano Letters 2022, 22, 7690–7698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassine, M.; Nair, A.; Fammels, J.; Wade, E.; Fu, Z.; Yassine, A.; Kirste, L.; Ambacher, O. Influence of structural properties on the ferroelectric behavior of hexagonal AlScN. Journal of Applied Physics 2022, 132, 114101. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0103578/19808540/114101_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Muralt, P.; Dubois, M.A.; Pezous, A. Thickness dependence of the properties of highly c-axis textured AlN thin films. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A 2004, 22, 361–365. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/avs/jva/article-pdf/22/2/361/8187840/361_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, N.; Muralt, P.; Baborowski, J.; Gentil, S.; Mukati, K.; Cantoni, M.; Seifert, A.; Setter, N. 1 0 0-Textured, piezoelectric Pb(Zrx, Ti1-x)O3 thin films for MEMS: integration, deposition and properties. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2003, 105, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Ryu, J.; Yoon, W.H.; Choi, J.J.; Hahn, B.D.; Kim, J.W.; Park, D.S.; Ahn, C.W.; Priya, S.; Jeong, D.Y. Stress-controlled Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 thick films by thermal expansion mismatch between substrate and Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 film. Journal of Applied Physics 2011, 110, 124101. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.3669384/14807602/124101_1_online.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Quaresima, S.; Casilli, N.; Badran, S.; Kaya, O.; Petrov, V.; Colombo, L.; Davaji, B.; Jornet, J.M.; Cassella, C. Monolithic Integration of a Dual-Mode On-Chip Antenna with a Ferroelectric Hafnium Zirconium Oxide Varactor for Reprogrammable Radio-Frequency Front Ends. Preprints 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; Simeoni, P.; Colombo, L.; Rinaldi, M. Piezoelectric and ferroelectric measurements on casted target-deposited Al0.45Sc0.45B0.1N thin films. In Frontiers in Materials; Frontiers, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Optimum Value | Range Investigated |

|---|---|---|

| N2 flow rate (sccm) | 20 | 20 − 35 (step 5) |

| Chuck height (mm) | 20 | 10 − 30 (step 5) |

| Temperature (°C) | 300 | 250 − 400 (step 50) |

| Target power (kW) | 5 | − |

| Substrate RF power (W) | 0 | 0 − 100 (step 25) |

| Film | Piezoelectric [, ] | Dielectric [avg. , min. ] | Ferroelectric [, ] | FOM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc0.3Al0.7N[This work] | 18 pm/V, pC/N | 18, 0.4% | 3.5 MV/cm,260 C/cm2 | 5.4 |

| AlN [61] | 5.15 pm/V, pm/V | 10.2, 0.1% | −, − | 6.6 |

| PZT[62] | − , pm/V | 935, 3.6% | −, − | 3.6 |

| PZT[63] | 26.4 pm/V,− | 1026, 2.5% | 0.052 MV/cm,17 C/cm2 | − |

| HZO[64] | 26.4 pm/V,− | 42, − | 0.75 MV/cm,24 C/cm2 | − |

| AlScBN[65] | 25 pm/V,− | −, − | 2.0 MV/cm,140 C/cm2 | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).