Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

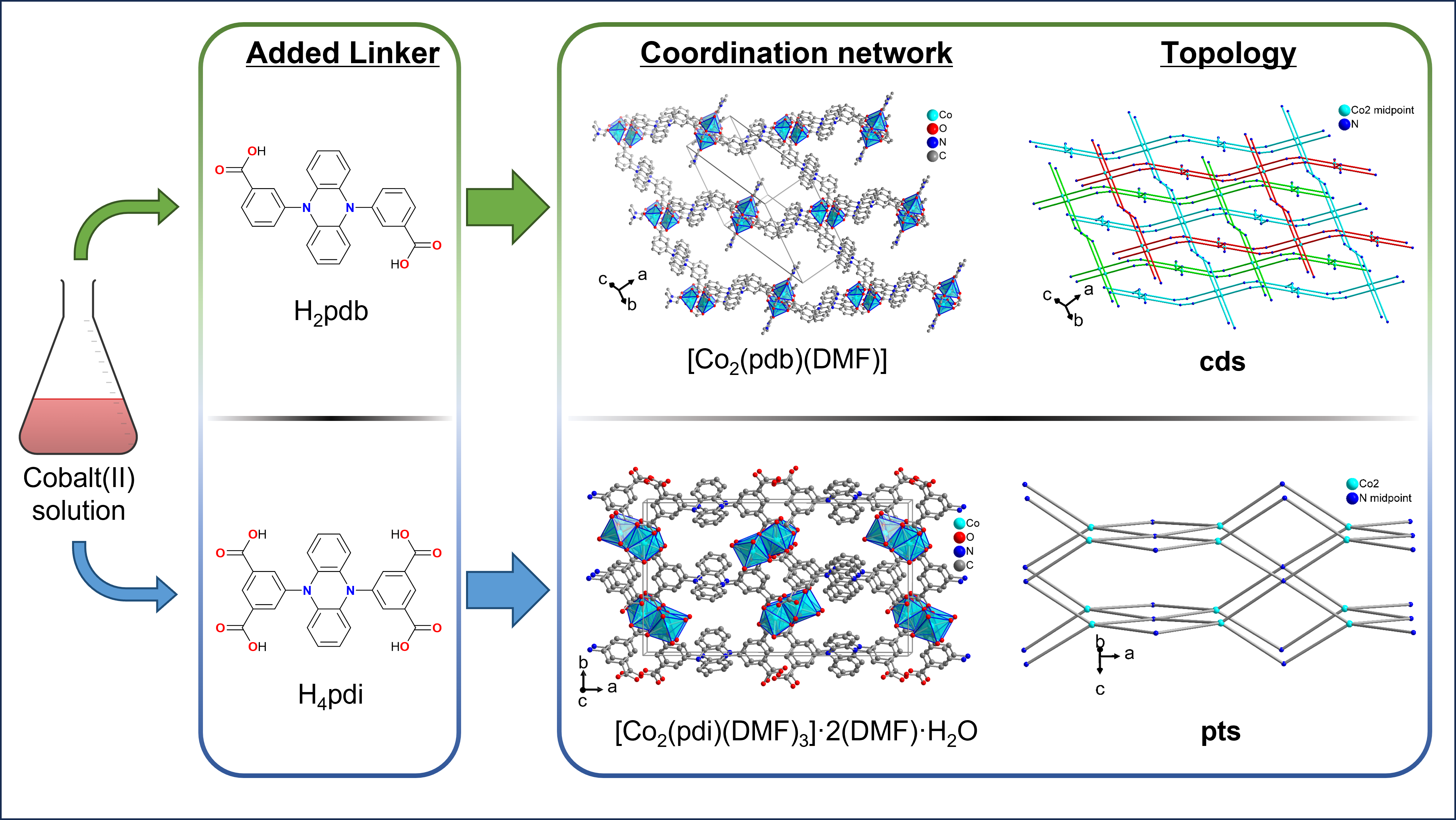

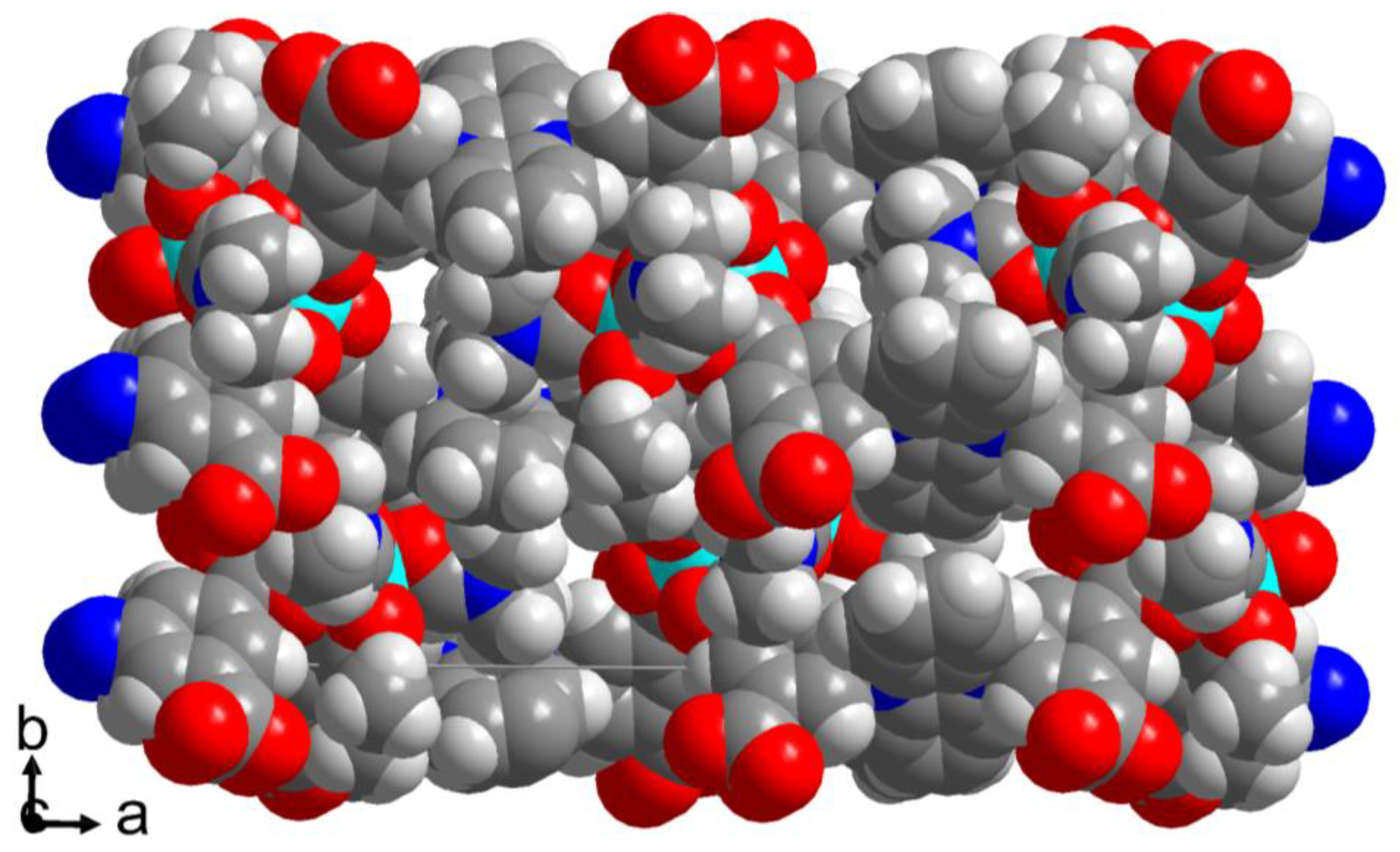

The crystal structures of the cobalt(II) metal-organic frameworks or coordination networks [Co(pdb)(DMF)] and [Co2(pdi)(DMF)3]·2(DMF)·H2O (H2pdb = 3,3′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)dibenzoic acid, H4pdi = 5,5′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)diisophthalic acid, DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide) were synthesized solvothermally from cobalt(II) nitrate and the free acid of the linker in DMF. In catena-[(N,N-dimethylformamide)-μ4-3,3′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)dibenzoate-cobalt(II)], [Co(pdb)(DMF)], the Co2 handles as secondary building units are surrounded by four carboxylate groups from four linkers in a paddle-wheel arrangement giving a three-dimensional (3D) network with cds (or CdSO4) topology in which the wide openings are filled by two symmetry related nets to a threefold interpenetrated structure. In catena-[tris(N,N-dimethylformamide)-μ8-5,5′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)diisophthalate-dicobalt(II)] bis(N,N-dimethylformamide) hydrate, [Co2(pdi)(DMF)3]·2(DMF)·H2O, there are two different Co atoms from which only Co2 is connected to each of the four carboxyl groups of the tetracarboxyl linker and, thus, is responsible for the 3D network formation. The network topology in [Co2(pdi)(DMF)3] is pts (or platinum(II) sulfide) when taking the Co2 atom as a tetrahedral and the linker as a square-planar fourfold node which is, however, inverse from the common square-planar metal and tetrahedral linker nodes in PtS and most pts topologies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of 5,10-dihydrophenazine (Scheme S1)

2.2. Synthesis of dimethyl 3,3′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)dibenzoate (Scheme S2)

2.3. Synthesis of 3,3′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)dibenzoic acid (H2pdb) (Scheme S3)

2.4. Synthesis of Tetramethyl 5,5′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)diisophthalate (Scheme S4)

2.5. Synthesis of 5,5′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)diisophthalic acid (H4pdi) (Scheme S5)

2.6. Synthesis of Catena-[(N,N-dimethylformamide)-μ4-3,3′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)dibenzoate-cobalt(II)], [Co(pdb)(DMF)]

2.6. Synthesis of Catena-[tris(N,N-dimethylformamide)-μ8-5,5′-(phenazine-5,10-diyl)diisophthalate-dicobalt(II)] bis(N,N-dimethylformamide) hydrate [Co2(pdi)(DMF)3]·2(DMF)·H2O

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structures of [Co(pdb)(DMF)]

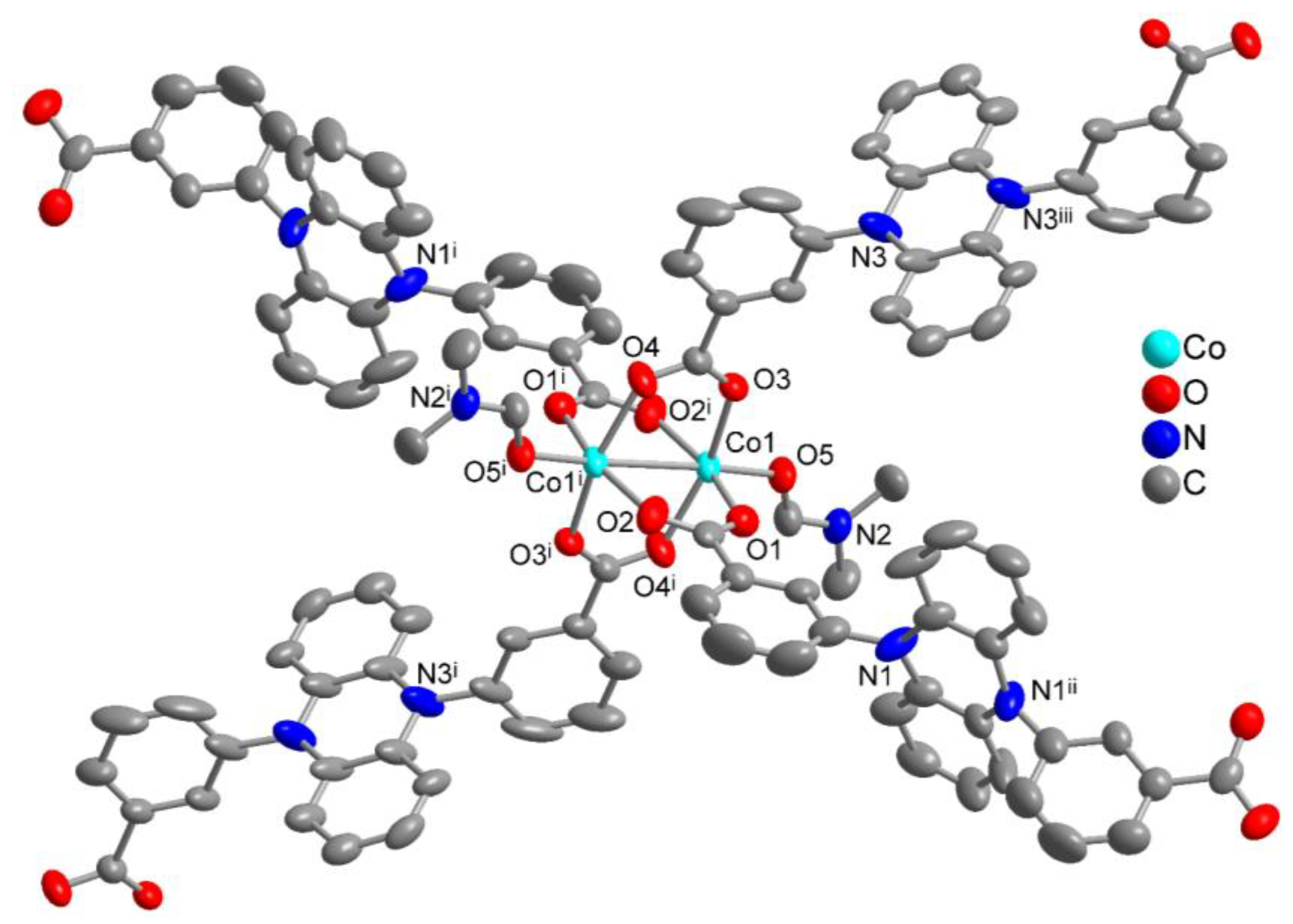

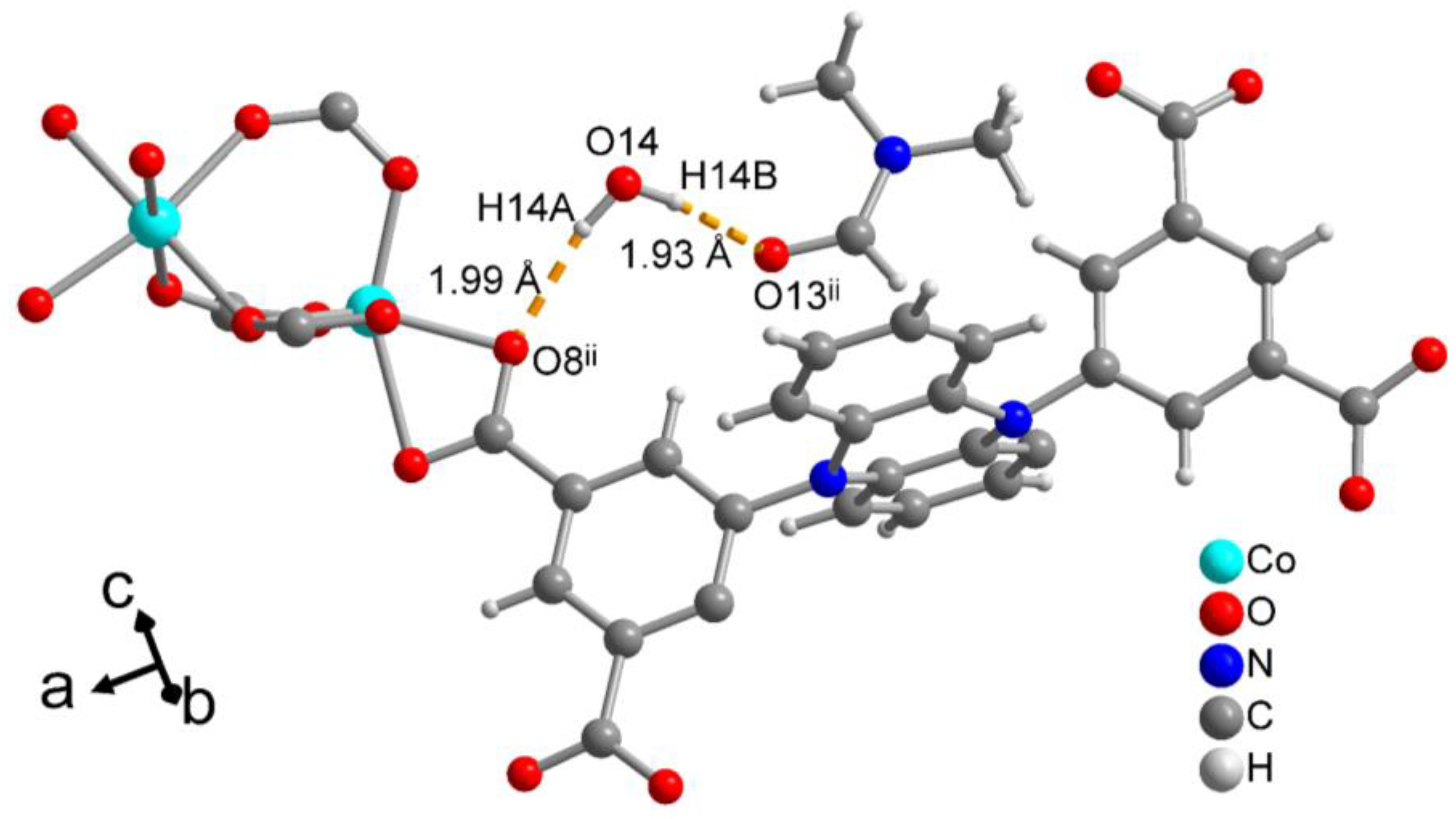

3.2. Crystal Structure of [Co2(pdi)(DMF)3]·2(DMF)·H2O

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, S.; Wang, L.; Tian, L.; Liu, Y.; Hu, K.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Hua, J. Leveraging phenazine and dihydrophenazine redox dynamics in conjugated microporous polymers for high-efficiency overall photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 11972–11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.; Solomon, M.B.; Leong, C.F.; D’Alessandro, D.M. Redox-active ligands: Recent advances towards their incorporation into coordination polymers and metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 439, 213891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.-Q.; Shen, J.-Q.; Zhang, J.-P. Metal–organic frameworks for electrocatalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 373, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.M. Exploiting redox activity in metal–organic frameworks: concepts, trends and perspectives. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 8957–8971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shizu, K.; Tanaka, H.; Nakanotani, H.; Yasuda, T.; Kaji, H.; Adachi, C. Controlled emission colors and singlet–triplet energy gaps of dihydrophenazine-based thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 2175–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulov, D.A.; Bogdanov, A.V.; Dorofeev, S.G.; Magdesieva, T.V. N,N0 -Diaryldihydrophenazines as a Sustainable and Cost-Effective Alternative to Precious Metal Complexes in the PhotoredoxCatalyzed Alkylation of Aryl Alkyl Ketones. Molecules 2023, 28, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, D.A.; McCarthy, B.G.; van de Lindt, Z.; Miyake, G.M. Radical Cations of Phenoxazine and Dihydrophenazine Photoredox Catalysts and Their Role as Deactivators in Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 4726–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Takeda, T.; Kuratsu, M.; Kozaki, M.; Sato, K.; Shiomi, D.; Takui, T.; Okada, K. Pyrene-dihydrophenazine bis(radical cation) in a singlet ground state. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2816–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unglaube, F.; Hünemörder, P.; Guo, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, D.; Mejía, E. Phenazine Radical Cations as Efficient Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysts for the Cross-Dehydrogenative Aza-Henry Reaction. Helv. Chim. Acta 2020, 103, e2000184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, T.; Li, F.; Sung, H.H.-Y.M.; Williams, I.; Quan, Y. Metal-organic framework boosts heterogeneous electron donor–acceptor catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.-Y.; Huang, B.; Wu, M.-X.; Xu, L.; Zhao, X.-L.; Shi, X.; Yang, H.-B. Redox-Active Dihydrophenazine-Based Macrocycle: Synthesis, Conformation-Adaptive Behavior and Host-Guest Complexation with Tetracyanoquinodimethane. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 1895–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theriot, J. C.; Lim, C.-H.; Yang, H.; Ryan, M. D.; Musgrave, C. B.; Miyake, G. M. Organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization driven by visible light. Science 2016, 352, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.-X.; Liu, C.-H.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Lin, W. Diaryl Dihydrophenazine-Based Porous Organic Polymers Enhance Synergistic Catalysis in Visible-Light-Driven Organic Transformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202310470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, D.A.; Puffer, K.O.; Chism, K.A.; Cole, J.P.; Theriot, J.C.; McCarthy, B.G.; Buss, B.L.; Lim, C.-H.; Lincoln, S.R.; Newell, B.S.; Miyake, G.M. Radical Addition to N,N-Diaryl Dihydrophenazine Photoredox Catalysts and Implications in Photoinduced Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromol. 2021, 54, 10, 4507–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J. P.; Federico, C. R.; Lim, C.-H.; Miyake, G. M. Photoinduced organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization using low ppm catalyst loading. Macromol. 2019, 52, 747−754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Jessop, P. G.; Cunningham, M. F. Versatility of organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization and CO2- switching for preparing both hydrophobic and hydrophilic polymers with the recycling of a photocatalyst. Macromol. 2019, 52, 6725− 6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Sartor, S.; Cole, J.; Damrauer, N.; Miyake, G. M. Solvent effects and side reactions in organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization for enabling the controlled polymerization of acrylates catalyzed by diaryl dihydrophenazines. Macromol. 2020, 53, 9208−9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Kang, X.; Yuan, C.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y. Porous 2D and 3D Covalent Organic Frameworks with Dimensionality-Dependent Photocatalytic Activity in Promoting Radical Ring-Opening Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 19466–19476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochetygov, I.; Roth, J.; Espín, J.; Pache, S.; Justin, A.; Schertenleib, T.; Taheri, N.; Chernyshov, D.; Queen, W. L. A Simple, Transition Metal Catalyst-Free Method for the Design of Complex Organic Building Blocks Used to Construct Porous Metal-Organic-Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202215595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, X.-F.; Yang, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Xi, C.; Zheng, L.; Miao, Z. Phenazine-functionalized Zn-based metal organic framework for efficient visible light photocatalytic sulfides. J. Solid State Chem. 2025, 351, 125525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. L.; Huang, B.; Zhao, X. L.; Shi, X.; Yang, H. B. Strong halide anion binding within the cavity of a conformation-adaptive phenazine-based Pd2L4 cage. Chem. 2023, 9, 2655–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tanga, X.; Gu, C. Dihydrophenazine linked porous organic polymers for high capacitance and energy density pseudocapacitive electrodes and devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 4984–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaku, E.; Gannett, C.N.; Carpenter, K.L.; Shen, L.; Abruna, H.D.; Dichtel, W.R. Phenazine- Based Covalent Organic Framework Cathode Materials with High Energy and Power Densities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16−20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-X.; Hong, Q.-Y.; Li, M.; Jiang, W.-L.; Huang, B.; Lu, S.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.-B.; Zhao, X.-L.; Shi, X. Self-assembly of conformation-adaptive dihydrophenazine-based coordination cages. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 1184–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.-g. Integrating p-type phenazine into covalent triazine framework to achieve co-storage of cations and anions for quasi-solid-state dual-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xu, Y.; Jin, S.; Chen, L.; Kaji, T.; Honsho, Y.; Addicoat, M.A.; Kim, J.; Saeki, A.; Ihee, H.; Seki, S.; Irle, S.; Hiramoto, M.; Gao, J.; Jiang, D. Conjugated organic framework with three-dimensionally ordered stable structure and delocalized π clouds. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Ji, H.; Qiao, D.; Xu, Y.; Qu, X.; Qi, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, R.; Dong, B. Vinylene-linked covalent organic frameworks based on phenanthroline for visible-light-driven bifunctional photocatalytic water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.-L.; Huang, B.; Wu, M.-X.; Zhu, Y.-K.; Zhao, X.-L.; Shi, X.; Yang, H.-B. Post-Synthetic Modification of Metal-Organic Frameworks Bearing Phenazine Radical Cations for aza-Diels-Alder Reactions. Chem. Asian. J. 2021, 16, 3985–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püschel, D.; Nau, M.; Assahub, N.; Beglau, T.H.Y.; Hufnagel, N.; Jordan, D.; Heinen, T.; Strothmann, T.; Suta, M.; Winter, R.F.; Janiak, C. Zinc and Cobalt Coordination Polymers Based on the Redox-Active Linker 4,4′-(Phenazine-5,10-diyl)dibenzoate: Structures and Electrochemical Properties. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 28, e202500270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K. Diamond, Version 5.0.0; Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization, Crystal Impact; K. Brandenburg & H. Putz Gbr: Bonn, Germany, 1997–2023.

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; He, Y.; Niu, Z.; He, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H. A Dual-Ion Organic Symmetric Battery Constructed from Phenazine-Based Artificial Bipolar Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9902–9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, D.; Dale, H.J.A.; Orr-Ewing, A.J. Ultrafast Observation of a Photoredox Reaction Mechanism: Photoinitiation in Organocatalyzed Atom-Transfer Radical Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Friedrichs, O.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Three-periodic nets and tilings: edge-transitive binodal structures. Acta Cryst. 2006, A62, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xue, Y.-S.; Liang, L.-L.; Ren, S.-B.; Li, Y.-Z.; Du, H.-B.; You, X.-Z. Porous Coordination Polymers of Transition Metal Sulfides with PtS Topology Built on a Semirigid Tetrahedral Linker. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 7685–7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.-H.; Lu, R.-Q.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.-Z. Three unique two-fold interpenetrated three-dimensional networks with PtS-type topology constructed from [M(CN)4] 2 (M ¼ Ni, Pd, Pt) as ‘‘square-planar’’ building blocks. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 1382–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.J.; D’Alessandro, D.M.; Kepert, C.J. A porous Mn(V) coordination framework with PtS topology: assessment of the influence of a terminal nitride on CO2 sorption. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 13308–13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrichs, O.D.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The CdSO4, rutile, cooperite and quartz dual nets: Interpenetration and catenation. Solid State Sci. 2003, 5, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, O.D.; O’Keeffe, M. Three-periodic tilings and nets: Face-transitive tilings and edge-transitive nets revisited. Acta Cryst. A 2007, 63, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, B.; Abourahma, H.; Bradner, M.W.; Lu, J.; McManus, G.J.; Zaworotko, M.J. A new 65.8 topology and a distorted 65.8 CdSO4 topology: Two new supramolecular isomers of [M2(bdc)2(L)2]n coordination polymers. Chem. Commun. 2003, 1342–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortín-Rubio, B.; Rostoll-Berenguer, J.; Vila, C.; Proserpio, D.M.; Guillerm, V.; Juanhuix, J.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D. Net-clipping as a top-down approach for the prediction of topologies of MOFs built from reduced-symmetry linkers. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12984–12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Lou, X. H., Li, Q. T., Du, W. J., & Xu, C. (2015). Three-Fold Interpenetrated CdSO4 Topology in a Co(II) Coordination Polymer Constructed From Pamoic Acid and N-Containing Auxiliary Ligand. Synthesis and Reactivity in Inorganic, Metal-Organic, and Nano-Metal Chemistry 2015, 45, 865–868. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.-B.; Ji, Z.; Qin, Y.-Y.; Yao, Y.-G. A rare twofold interpenetrated cds topology in a Zn-organic polymer [Zn2(BDC)(BPP)Cl2]n. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2006, 9, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, G.J.; LaDuca, R.L. Poly[[[μ-1,4-bis(pyridin-4-ylmethyl)piperazine][μ-4-(2-carboxylatoethyl)benzoato]copper(II)] monohydrate], a coordination polymer with twofold interpenetrated cds topology networks. IUCrData 2023, 8, x230855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-J.; Liao, K.-S.; Wu, J.-Y. A Water-Stable 2-Fold Interpenetrating cds Net as a Bifunctional Fluorescence-Responsive Sensor for Selective Detection of Cr(III) and Cr(VI) Ions. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostaki, G., E.; Casella, L.; Hadjiliadis, N.; Monzani, E.; Kourkoumelis, N.; Plakatouras, J., C. Interpenetrated networks from a novel nanometer-sized pseudopeptidic ligand, bridging water, and transition metal ions with cds topology. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3859–3861. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.-C.; Wang, X.; Drozd, V.; Raptis, R.G. A Foldable Metal–Organic Framework with cds Topology Assembled via Four-Connected Square-Planar Single Ni2+-Ion Nodes and Linear Bidentate Linkers. Crystals 2024, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [Co(pdb)(DMF)] | [Co2(pdi)(DMF)3]·2(DMF)·H2O | |

| empirical formula | C29H23CoN3O5 | C43H51Co2N7O14 |

| mol wt (g mol–1) | 552.43 | 1007.76 |

| temperature (K) | 150 | 150 |

| crystal system | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| space group | I2/a | Pna21 |

| a (Å) | 9.5099 (6) | 26.9491 (5) |

| b (Å) | 18.7609 (15) | 15.5325 (3) |

| c (Å) | 27.3129 (19) | 11.4627 (2) |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 91.587 (6) | 90 |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| Volume, V (Å3) | 4871.1 (6) | 4798.14 (15) |

| Z, Z′ | 8, 1 | 4, 1 |

| Dcalc (g/cm3) | 1.507 | 1.395 |

| μ (mm–1) | 5.922 | 6.02 |

| F(000) | 2280 | 2096 |

| crystal size [mm3] | 0.09 × 0.05 × 0.04 | 0.1 × 0.07 × 0.05 |

| wavelength (Å) | 1.54184 | 1.54184 |

| No. of unique reflections | 4840 | 8579 |

| No. of total reflections | 27266 | 64849 |

| No. of parameters | 349 | 608 |

| Rint | 0.1268 | 0.0715 |

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)] (a) | 0.0632 | 0.0445 |

| wR[F2 > 2σ(F2)] (a) | 0.1270 | 0.1091 |

| R, wR(F2) [all data] (a) | 0.1248, 0.1523 | 0.0494, 0.1116 |

| S [all data] (a) | 1.073 | 1.041 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e·Å−3) (b) | 0.678, −0.471 | 0.722, −0.365 |

| CCDC no. | 2522790 | 2522791 |

| Co1—O1 | 2.006 (4) | O1—Co1—O5 | 98.90 (15) |

| Co1—O2i | 2.023 (4) | O1—Co1—O2i | 163.69 (16) |

| Co1—O3 | 2.023 (3) | O2i—Co1—O4i | 89.53 (15) |

| Co1—O4i | 2.081 (3) | O2i—Co1—O5 | 97.18 (15) |

| Co1—O5 | 2.027 (3) | O3—Co1—O4i | 163.52 (13) |

| Co1···Co1i | 2.8068 (14) | O3—Co1—O5 | 100.55 (13) |

| O3—Co1—O2i | 89.66 (13) | ||

| O1—Co1—O3 | 90.06 (13) | O5—Co1—O4i | 95.88 (13) |

| O1—Co1—O4i | 86.15 (14) |

| Co1—O1 | 2.072 (3) | O10—Co1—O5i | 91.01 (16) |

| Co1—O3ii | 2.040 (3) | O10—Co1—O11 | 91.32 (16) |

| Co1—O5i | 2.105 (3) | O10—Co1—O1 | 89.36 (16) |

| Co1—O9 | 2.128 (4) | O10—Co1—O9 | 91.85 (17) |

| Co1—O10 | 2.069 (4) | O11—Co1—O5i | 93.69 (14) |

| Co1—O11 | 2.097 (3) | O11—Co1—O9 | 86.46 (15) |

| Co2—O2 | 1.993 (3) | ||

| Co2—O4ii | 2.037 (3) | O2—Co2—O5i | 106.59 (15) |

| Co2—O5i | 2.105 (3) | O2—Co2—O4ii | 94.93 (15) |

| Co2—O6i | 2.270 (4) | O2—Co2—O7iii | 153.89 (13) |

| Co2—O7iii | 2.265 (4) | O2—Co2—O8iii | 93.13 (14) |

| Co2—O8iii | 2.050 (3) | O2—Co2—O6i | 94.23 (15) |

| O4ii—Co2—O5i | 100.40 (13) | ||

| O1—Co1—O5i | 97.97 (13) | O4ii—Co2—O7iii | 95.87 (14) |

| O1—Co1—O11 | 168.31 (14) | O4ii—Co2—O8iii | 108.82 (15) |

| O1—Co1—O9 | 81.86 (14) | O4ii—Co2—O6i | 160.17 (13) |

| O3ii—Co1—O5i | 86.19 (14) | O5i—Co2—O7iii | 94.72 (13) |

| O3ii—Co1—O11 | 88.10 (15) | O5i—Co2—O6i | 60.06 (12) |

| O3ii—Co1—O1 | 91.80 (15) | O8iii—Co2—O5i | 143.07 (13) |

| O3ii—Co1—O9 | 90.95 (15) | O8iii—Co2—O7iii | 60.87 (13) |

| O3ii—Co1—O10 | 177.10 (16) | O8iii—Co2—O6i | 88.18 (14) |

| Co1—Co2 | 3.368 (1) | Co2iv—O5—Co1iv | 106.27 (14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).