Introduction

Digital health, which encompasses telemedicine, mobile health (mHealth), AI diagnostics, electronic health records, and wearable devices, has the potential to transform healthcare systems worldwide. Its central aim is to make healthcare faster, more efficient, inclusive, and far-reaching, especially in resource-limited environments such as low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [

1]. Digital health innovations hold transformative potential in LMICs, where healthcare access is often limited by infrastructure, economic, and educational barriers to healthcare access. In pediatric care, where early interventions are vital, digital health tools, such as mHealth apps, SMS reminders, and social media communication, can bridge the gap between healthcare providers and caregivers. However, their effectiveness must be critically evaluated to ensure they deliver real benefits, particularly in addressing persistent health issues [

2].

Digital literacy is a crucial aspect of human capacity in the digital era, particularly when individuals engage as users of digital health technologies. It not only influences how people access, interpret, and evaluate health information but also determines their ability to effectively use digital tools for health management and decision-making. Therefore, assessing digital literacy should be considered an essential component of any digital health evaluation, as it directly affects the accuracy, usability, and overall impact of such technologies. Studies have shown that higher levels of digital literacy are associated with better health outcomes and greater engagement with digital health platforms [

3,

4]

The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated digital health uptake, driving the widespread adoption of telemedicine platforms, mobile applications, and digital surveillance tools to sustain essential services while reducing infection risk [

5]. These interventions offer scalable and cost-effective solutions to longstanding healthcare barriers, ranging from nutrition education, maternal and child health to chronic disease monitoring and public health reporting [

4].

Beyond bridging access gaps, digital health supports healthcare workforce capacity building and improves patient-provider partnerships by facilitating decision-making processes, remote consultations, and personalized interventions [

6]. Innovative projects, such as EU-funded initiatives for training health professionals in digital competencies, underscore the importance of building both digital infrastructure and human capacity [

7].

Methods

This study employed a scoping review that followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The review protocol was developed to identify, map, and synthesize literature on digital health assessment in LMICs, with particular attention to three assessment pillars: technology benchmarking, digital health literacy, and social media listening.

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they were peer-reviewed journal publications between January 2020 and September 2025, focused on LMICs as defined by the World Bank or provided frameworks relevant to LMICs health systems, and addressed at least one of the three assessment pillars. Studies were considered regardless of whether they employed quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods, or review-based approaches. Exclusion criteria included studies unrelated to digital health, commentary or opinion pieces without empirical or methodological contributions, and articles focused solely on high-income countries without LMICs relevance. The search was conducted in PubMed in September 2025, using the following Boolean string adapted to PubMed syntax:

(“digital health” OR “mHealth” OR “eHealth” OR “telehealth” OR “mobile health application”)

AND

(“evaluation” OR “assessment” OR “technology benchmarking” OR “usability assessment” OR “implementation evaluation” OR “digital health literacy” OR “eHealth literacy” OR “social media analysis” OR “infodemic management”)

AND

(“low- and middle-income countries” OR “LMICs” OR “resource-limited settings” OR “developing countries” OR “global south”)

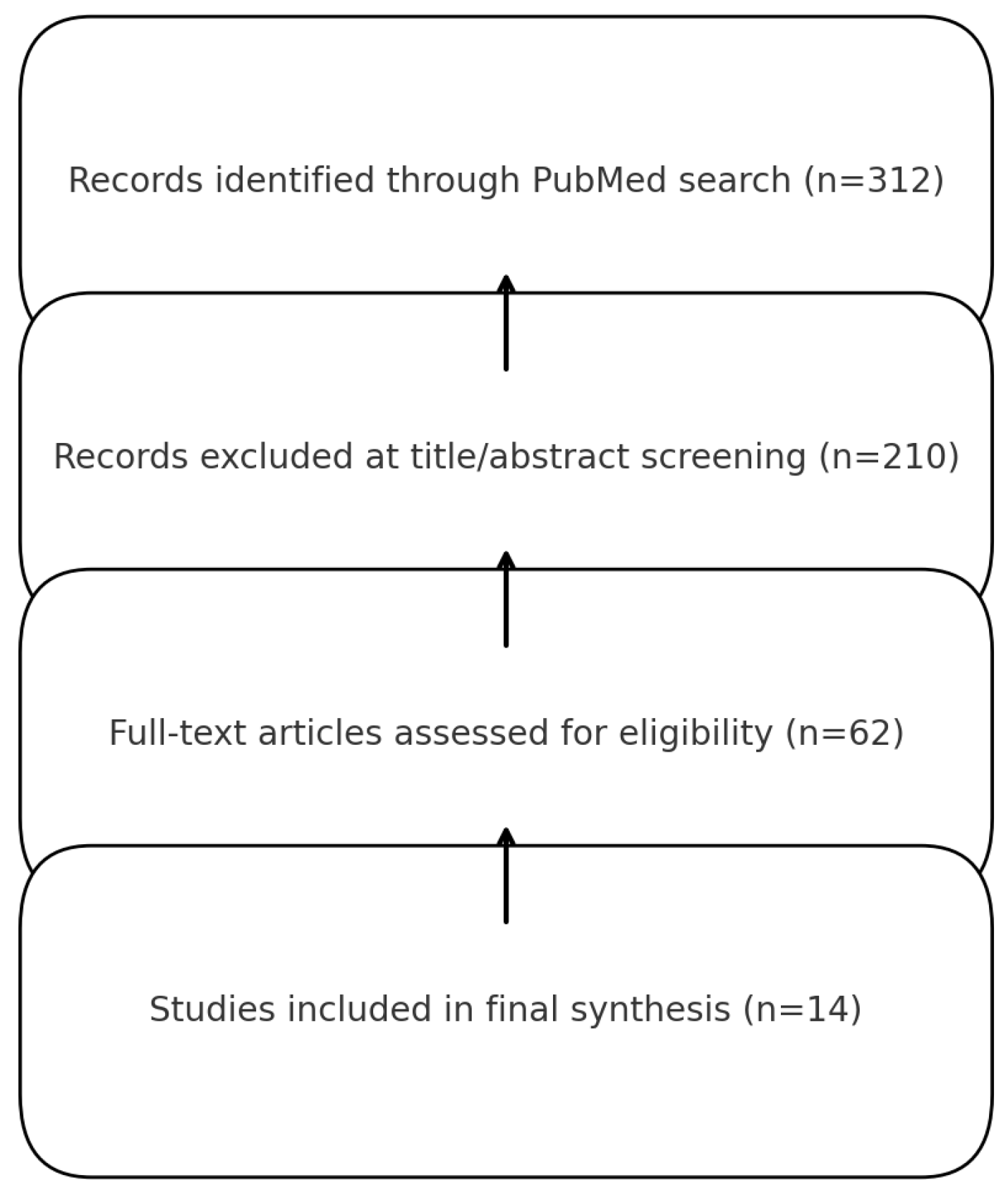

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (AS and BD). Full texts were then assessed against the predefined eligibility criteria, and any discrepancies were resolved in consultation with a third reviewer (EG). This process resulted in the inclusion of fourteen articles in the final synthesis. Data were charted using a standardized extraction template that recorded study citation and year, LMICs focus or study setting, study design and objectives, the assessment pillar or pillars addressed, and the main contributions and findings. The results were synthesized descriptively and organized according to the three pillars of assessment. Articles with cross-cutting relevance, such as frameworks applicable to multiple pillars, were categorized separately. Owing to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes, no meta-analysis was attempted.

Results

The scoping review identified 14 studies (see

Figure 1) published between 2020 and 2025 that examined aspects of digital health assessment in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The studies covered three thematic pillars:

Technology Benchmarking (n=4) – focused on benchmarking diagnostics, registries, infrastructure assessment, and health technology assessment (HTA) frameworks.

Digital Health Literacy (n=4) – included interventions for low-literacy populations, scoping reviews of digital literacy determinants, and frameworks for workforce competency.

Social Media Listening (n=3) – focused on infodemic monitoring, big data surveillance, and methodological insights for using social media platforms for public health.

Cross-Cutting Analyses (n=3) – provided overviews of digital health implementation in LMICs and classification approaches for health technology tiers.

These studies represented a growing emphasis on holistic assessment approaches in LMICs, integrating infrastructure benchmarking, end-user literacy evaluation, and population-level surveillance methods.

The results from the 14 studies summarized in

Table 1 were systematically analyzed and organized into four main categories. These categories were derived based on recurring themes and methodological approaches identified across the studies. Each category represents a distinct dimension of the findings, allowing for a more structured interpretation and comparison. The categories are explained in detail below.

1. Technology Benchmarking

Four studies explored approaches to benchmarking digital health tools and infrastructure in LMICs [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Yadav quantified diagnostic availability across ten LMICs using standardized Service Provision Assessment indicators, providing crucial data for policy and planning [

8]. Waqar highlighted the value of perioperative registries as tools for benchmarking surgical quality, demonstrating their potential to improve outcomes in resource-limited settings [

9]. Patel introduced a district-level model in India to identify barriers to scaling digital infrastructure, offering methods that could be applied to other LMICs [

10]. Finally, Leckenby proposed a “sandbox approach” for regulatory and health technology assessment innovation, aimed at evaluating emerging digital health technologies [

11]. These studies collectively contribute to efforts in establishing benchmarks for digital health infrastructure in LMICs. Each approach provides essential insights for enhancing the effectiveness of digital health tools in improving healthcare quality and access in resource-constrained settings.

2. Digital Health Literacy

Four studies investigated digital health literacy (DHL) among vulnerable populations and health worker [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Salim piloted a mobile app tailored to low-literacy adults with asthma, evidence showed that mobile applications tailored for individuals with limited literacy can be feasible and effective in LMICs-like contexts [

12]. Choukou reviewed digital literacy interventions during COVID-19, emphasized the crucial role of digital literacy in countering infodemics and promoting reliable health information [

13]. Nazeha introduced digital competency frameworks have also been developed to define digital competencies for health professionals, ensuring that skills are standardized and measurable [

14]. While Shi et al. (2024) synthesized determinants of DHL among older adults, revealing critical equity gaps that are especially pronounced in low-resource settings [

15].

4. Cross-Cutting Reviews and Landscape Analyses

Three recent reviews synthesized lessons on digital health integration, barriers, and classification frameworks [

19,

20,

21]. Till Bergman’s study offered typologies for digital health technologies specifically in maternal and child health within LMIC health systems, providing valuable insights for their adoption [

19]. Kosowicz introduced a NICE-tier classification for digital health technologies in Vietnam, offering a practical framework to guide their implementation and benchmarking [

20]. Additionally, these reviews collectively provide key frameworks and typologies, such as the NICE tiers, to support the integration and scaling of digital health tools in resource-constrained settings [

21]. These works contribute significantly to understanding the barriers and challenges in adopting digital health technologies, while offering practical guidance on their classification and integration in LMICs.

Discussion

Technology Benchmarking

Technology benchmarking, more broadly, entails the systematic evaluation of digital health applications using standardized tools. For instance, the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) provides a multidimensional assessment of engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and information quality [

22]. MARS has been validated as a reliable tool for evaluating health apps in various domains and is particularly useful for assessing user-centered design in LMICs settings [

23].

Recently, we conducted a benchmarking study of pediatric-focused digital health applications available in the Indonesian App Store. MARS tools revealed that while the apps generally scored high in functionality and aesthetic design, engagement, and information quality varied considerably. Only 33% of the apps incorporated personalized guidance and feedback features, and fewer than half offered community-interaction tools. These deficits are particularly detrimental in rural settings, where offline functionality, linguistic localization, and interactivity are essential for uptake and sustainability [

24].

Benchmarking highlights how these apps often fall short in terms of user engagement and interactivity, which are crucial for long-term behavior change [

25]. The use of usability scales, such as the System Usability Scale (SUS) and User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ), can complement the MARS to provide holistic insights [

26]. For instance, some apps score relatively high in terms of content relevance but lack customizable features for rural users with intermittent Internet access. Other benchmarking approaches include heuristic evaluations [

27], ISO/IEC 25010 software quality standards, and app store review analyses [

28]. Integration with electronic medical records (EMRs) and data security measures also forms part of benchmarking in contexts where personal data protection laws may be weak or inconsistently applied [

29].

Digital Health Literacy

The importance of digital health literacy (DHL) is increasingly recognized, particularly among vulnerable populations and health workers. In one survey, nearly half of the individuals who had downloaded an mHealth app reported discontinuing it, with the majority citing a high burden of data entry or confusion with app usage [

30]. Studies in LMICs have shown that low DHL correlated with poor health-seeking behavior, delayed treatment, and misuse of health apps [

31,

32]. Tools such as the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) and Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) offer frameworks for measuring these competencies [

33].

Addressing DHL gaps requires context-specific training, community-based digital education programs, and the inclusion of local languages and dialects in app content [

34]. Gender dynamics also affect access; women, who are often primary caregivers, may lack smartphone access or digital training because of patriarchal norms [

35]. One reliable instrument for measuring digital health literacy is the HLS19-DIGI. The HLS19-DIGI scale was sufficiently unidimensional, and no differential item functioning or disordered response categories were observed [

36].

Digital health literacy (DHL) has emerged as a critical subdomain of health literacy, particularly in the era of rapidly expanding digital health technologies. It is broadly defined as the ability to locate, comprehend, critically assess, and apply health information obtained from digital platforms to make informed decisions. This competency is essential not only for navigating digital health tools but also for fostering effective health-related decision-making among individuals and communities [

37].

In low- and middle-income countries, including rural regions, digital health literacy is pivotal in determining the success of mobile health (mHealth) initiatives. Given the uneven distribution of technological infrastructure and educational attainment, disparities in DHL among parents and caregivers can significantly hinder the adoption and sustained use of digital health tools by these groups. For example, one user experience study revealed that nearly 50% of individuals who had initially downloaded an mHealth application discontinued its use. The most frequently cited reasons included the complexity of navigation, high data input burden, and confusion regarding the app’s functions [

30].

Empirical studies in LMICs settings have consistently demonstrated that limited DHL is associated with suboptimal health-seeking behaviors, delayed treatment initiation, and inappropriate use of digital health resources. Such limitations can compromise the effectiveness of mHealth interventions designed to support maternal and child health, nutrition, and chronic disease management [

32].

Given these challenges, accurately measuring individuals’ digital health literacy is essential to identify gaps and guide effective interventions. Various validated measurement instruments have been developed to systematically assess DHL. The

eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) remains one of the most widely used tools for measuring individuals’ perceived skills in finding and evaluating online health information [

38]. Recently, the

Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) was introduced, offering a multidimensional approach that includes operational skills, navigation, evaluation, and privacy management [

33]. In addition, the

HLS19-DIGI, a digital extension of the Health Literacy Survey 2019, has proven to be a reliable and unidimensional instrument for measuring DHL across populations. It showed no significant issues with differential item functioning or response category disorders, making it suitable for comparative and cross-national research [

36].

Addressing the gaps in DHL requires culturally and contextually sensitive strategies. Community-based digital education programs, especially those that incorporate local languages and dialects, are vital for ensuring inclusivity and comprehensibility. Furthermore, attention must be paid to gender-based disparities in digital access and use. In many patriarchal societies, including rural Indonesia, women who often serve as the primary caregivers may face limited access to smartphones or lack digital training, further exacerbating health inequalities [

39].

In conclusion, enhancing digital health literacy is not merely a technical challenge but a multidimensional task that intersects education, infrastructure, gender equity, and cultural context. As digital health continues to evolve, particularly in underserved regions, strengthening DHL will be instrumental in ensuring equitable access to and effective use of health technologies.

Social Media Listening

Social media listening, also known as social media intelligence, refers to the process of tracking and analyzing online conversations, posts, and trends to gain insights into public perceptions, behaviors, and needs. While widely adopted in the commercial sector for brand monitoring and customer engagement, its use in healthcare remains limited, particularly in digital health initiatives. This article seeks to introduce the value of social media listening in healthcare and propose its greater integration, particularly in contexts with high digital penetration but limited traditional health infrastructure [

40].

In many countries, healthcare providers have not yet fully embraced social media as a legitimate data source. A national survey conducted in the United States found that nearly half of the physicians and medical students expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of online communication in improving patient–physician relationships. This indicates a substantial trust gap and highlights the need for improved digital literacy among healthcare professionals [

41].

However, social media platforms offer a rich environment for understanding the evolving relationship between healthcare systems and societies. Online interactions through comments, shares, or discussions mirror real-world sentiments and provide a public space where patients, caregivers, and providers co-create narratives about health and wellness. These interactions also illustrate the concept of partnership in digital health, where the traditional roles of patients and providers become more interactive and horizontal [

42].

Despite frequent critiques regarding the negative effects of social media, particularly its association with mental health challenges, it remains an untapped asset for healthcare insights. In regions with large and active digital populations, such as Southeast Asia and Latin America, social media can serve as a real-time barometer of public sentiments. For example, Muralidhara and Paul analyzed Twitter discussions surrounding antidiabetic drugs, demonstrating how social media platforms can reflect societal discourse and behavioral trends related to medication use and chronic disease management [

42].

Social listening is particularly relevant in LMICs, where conventional health surveillance systems may be underdeveloped. In such contexts, social media offers an opportunity to understand community experiences, identify emerging health concerns and improve service delivery. For instance, discussions around stunting, caused by chronic malnutrition, can provide health professionals with valuable qualitative data on public knowledge gaps, misinformation, or systemic barriers to nutrition [

43].

Technological tools for social media scraping and monitoring have evolved significantly, enabling large-scale data extractions and sentiment analyses. Platforms such as Brandwatch, Talkwalker, and NetBase are primarily used in the private sector; however, academic researchers and policymakers have only recently begun exploring their application in public health. Unlike election monitoring, where social media has become a critical factor, healthcare still lags in adopting such intelligence systems [

44,

45].

Healthcare institutions can leverage social media in several impactful ways. By analyzing trends in real time, professionals can tailor health interventions more precisely to community needs. Moreover, targeted health communication campaigns informed by online discourse can improve their reach and effectiveness. In countries such as Indonesia, where mobile and social media usage is high, social listening can serve as a crucial tool for improving maternal and child health by identifying misinformation and gauging public engagement with health topics [

46].

Numerous examples from high-income countries highlighted the successful use of social media in health care. For instance, the Mayo Clinic established its Social Media Center to train healthcare professionals in digital engagement and share evidence-based health information with the public [

40]. Similarly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has used platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to run large-scale public health campaigns, particularly during health emergencies [

47]. The Cleveland Clinic’s active social media presence, including interactive Q&A sessions and educational videos, has helped increase patient access to trusted medical information [

48].

Additionally, online communities have emerged as vital sources of peer support, especially for individuals with chronic conditions such as diabetes and cancer. These platforms allow users to exchange experiences, reduce isolation, and improve their self-management. The #ThisIsPublicHealth campaign by the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) exemplifies how social media can promote health awareness and education through community-driven storytelling and visual engagement [

49].

In conclusion, social media listening offers a powerful and underutilized approach to enhance healthcare delivery, especially in digitally active but medically underserved regions. By integrating this method into digital health strategies, healthcare providers can better understand public needs, combat misinformation, and foster responsive and inclusive health systems.

Cross-Cutting Reviews and Landscape Analyses

Despite the widespread availability of digital communication tools and social media in both developing and developed countries, their adoption in clinical settings remains limited due to skepticism. For example, physicians at an academic medical center in Lebanon expressed reluctance to use online applications and social media platforms to communicate with patients. This hesitation highlighted the challenges of integrating virtual communication into healthcare, emphasizing the need to assess healthcare providers’ perceptions and develop supportive policies. Rather than resisting this new communication paradigm, healthcare institutions should proactively embrace digital tools to enhance patient care and engagement [

50].

Digital surveillance presents diverse opportunities for monitoring disease trends and detecting outbreaks in near real-time. These techniques include augmenting traditional data sources, mapping geographic spread, and optimizing existing surveillance frameworks. For instance, Google search data have been successfully integrated as a “virtual provider” to enhance influenza-like illness surveillance, supplementing outpatient reports. Similarly, Twitter data have helped identify restaurants that are potentially linked to foodborne outbreaks, facilitating targeted inspections. In Madagascar, Google search trends were used alongside healthcare statistics to forecast plague outbreaks, and geolocation data from Twitter combined with air traffic patterns traced the spread of the Chikungunya virus [

51].

Beyond infectious disease monitoring, digital data from social media, online surveys, and mobile applications provide critical insights into public health factors, such as dietary habits, healthcare access, and socioeconomic conditions influencing nutrition and child growth. Geospatial analysis of satellite imagery and mobile phone usage helps identify patterns of vector-borne diseases, thereby supporting precise interventions and resource distribution. Integrating mobile health applications into surveillance enables real-time data collection on children’s growth and nutrition, facilitating early detection and timely intervention. This digital ecosystem empowers health officials to identify the underlying factors driving stunting and tailor public health responses [

51].

Digital health interventions encompass a broad spectrum of technologies, mobile applications, telemedicine platforms, and web-based educational resources that are increasingly employed to promote maternal and child health in resource-limited settings. These technologies offer innovative solutions to overcome barriers, such as restricted access to healthcare facilities and knowledge gaps among caregivers. In stunting prevention, digital tools address various aspects of child development, including nutrition, immunization, and early stimulation. For example, nutrition-focused mobile applications provide parents with personalized feeding guidance, growth tracking, and reminders for vaccinations and health checkups. Telemedicine connects families with pediatricians and nutritionists for remote consultations, and interactive online modules educate caregivers about breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and hygiene practices. These digital resources empower parents with evidence-based knowledge that is crucial for optimizing child nutrition and health outcomes [

19].

Three Pillars for Digital Health Assessment

A comprehensive framework for evaluating digital health interventions integrates technology benchmarking, digital health literacy (DHL), and social media listening (SML). This triadic model is especially pertinent to pediatric care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where infrastructural, educational, and cultural barriers complicate health communication.

Technology benchmarking assesses the technical quality of digital health applications using standardized tools such as the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), System Usability Scale (SUS), and heuristic evaluations. However, these metrics often overlook the user context.

Digital health literacy research bridges this gap by exploring why some users discontinue the use of an app despite favorable technical ratings. Issues such as comprehension difficulties, perceived irrelevance, and distrust are common barriers to using eHealth tools [

52].

Social media listening captures emergent narratives and public sentiments that shape health behaviors, sometimes more powerfully than formal education [

48].

Isolated interventions risk ineffectiveness if they ignore this complexity of the problem. For example, Indonesia’s digital stunting reduction programs may exclude vulnerable communities when implemented without grassroots DHL training [

53]. Likewise, technically robust apps can be overshadowed by competing misinformation [

54]. Optimal digital health systems for pediatric care should integrate all three pillars: benchmarking during app development, embedding DHL education within community health worker (CHW) and caregiver training, and continuous social media monitoring to detect and respond to evolving narratives. This integration fosters iterative improvements, ensuring that technology aligns with real user needs [

55].

Prioritizing participatory design enhances trust and user engagement, which is especially critical in pediatric health, where caregivers make key decisions. Involving communities in app design, content localization, and feedback mechanisms empowers users and fosters ownership. However, ethical challenges arise with digital tools, particularly concerning privacy in social media listening, which often involves analyzing publicly available but sensitive data sets. Benchmarking efforts must also focus on inclusiveness, ensuring that platforms are accessible to users with disabilities and those in remote areas. Furthermore, DHL education should avoid imposing top-down health behavior models and instead promote critical, context-aware decision-making that respects cultural nuances. [

56].

Challenges and Future Directions

Although digital health interventions hold a promise for preventing stunting, significant barriers remain. Limited internet access, low digital literacy, and cultural resistance, particularly in rural and marginalized populations, restrict uptake. Additionally, ensuring the accuracy and quality of digital health content is vital to prevent misinformation that could undermine health outcomes in the future.

Future efforts should focus on strengthening digital infrastructure, expanding affordable access to technology, and enhancing caregiver health literacy. Collaborative partnerships among governments, healthcare providers, and technology developers can facilitate context-specific digital solutions tailored to local requirements. By fostering synergy between pediatricians and families through digital tools, stunting prevention initiatives can be more effective, ultimately improving child health in developing countries [

57].

Limitation

This study was conducted as a mini-review and was therefore limited in scope and depth. It included only published studies, which may have excluded relevant grey literature, reports, or unpublished data that could provide additional insights into pediatric digital health initiatives. Although the stated emphasis is on pediatric care, many of the included findings remain general to digital health literacy rather than being specifically focused on children or pediatric populations. This reflects a broader gap in the existing literature, where most research addresses adult users or healthcare professionals. Consequently, while the proposed framework integrating technology benchmarking, digital health literacy, and social media analysis offers a comprehensive lens for evaluating digital health interventions, its direct applicability to pediatric contexts remains preliminary. Future studies should expand beyond this mini-review by incorporating unpublished evidence, age-specific assessment tools, and participatory approaches that include parents, children, and pediatric health workers in low- and middle-income countries.

Conclusion

The convergence of technology benchmarking, digital health literacy, and social media analysis provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating digital health interventions in pediatric care. Our scoping review of 14 studies, summarized across four main categories technology benchmarking, digital health literacy, social media listening, and cross-cutting reviews/ landscape analyses highlights the multidimensional nature of digital health evaluation in low- and middle-income countries. Evidence from the technology benchmarking category underscores the importance of assessing infrastructure, regulatory approaches, and implementation barriers, while findings on digital health literacy emphasize the need for tools that are accessible, understandable, and equitable for diverse populations. Social media listening studies illustrate how real-time data can inform surveillance, communication, and engagement strategies, and cross-cutting reviews provide typologies and frameworks that guide adoption and policy in resource-limited settings.

Author Contributions

A.S.I. contributed to various aspects, including conceptualizing the research goals, securing funding, and managing the project. A.S.I. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, and the development of methodologies and software. Additionally, A.S.I. oversaw the research process, ensuring validation and visualization of the results, also drafted and revised the manuscript. B.D. and E.G. provided supervision and validation, also drafted and revised the manuscript ensuring the research’s accuracy and reliability.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship, Tempus Public Foundation, registration number SHE-44703-004/2021.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank The Institute of Behavioral Sciences Semmelweis University for providing academic support and discussion for conducting this study. We are also grateful to the Tempus Foundation for providing the main funding for this research.

Declarations

Competing interests the authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ibrahim, MS; Mohamed Yusoff, H; Abu Bakar, YI; Thwe Aung, MM; Abas, MI; Ramli, RA. Digital health for quality healthcare: A systematic mapping of review studies. DIGITAL HEALTH 2022, 8, 20552076221085810. [Google Scholar]

- Irawan, AS; Döbrössy, BM; Biresaw, MS; Muharram, AP; Kovács, SD; Girasek, E. Exploring characteristics and common features of digital health in pediatric care in developing countries: a systematic review. (2673-253X (Electronic)). pp. 2673–253X (Electronic)).

- Norman, CD; Skinner, HA. eHealth Literacy: Essential Skills for Consumer Health in a Networked World. J Med Internet Res. 2006, 8(2), e9. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stellefson M, Hanik B Fau - Chaney B, Chaney B Fau - Chaney D, Chaney D Fau - Tennant B, Tennant B Fau - Chavarria EA, Chavarria EA. eHealth literacy among college students: a systematic review with implications for eHealth education. (1438-8871 (Electronic)). pp. 1438–8871.

- Sylla, B; Ismaila, O; Diallo, G. 25 Years of Digital Health Toward Universal Health Coverage in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Rapid Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e59042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges do Nascimento, IJ; Abdulazeem, HM; Vasanthan, LT; Martinez, EZ; Zucoloto, ML; Østengaard, L; et al. The global effect of digital health technologies on health workers’ competencies and health workplace: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and lexical-based and sentence-based meta-analysis. The Lancet Digital Health 2023, 5(8), e534–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, JC; Elvas, LB; Correia, R; Mascarenhas, M. Empowering Health Professionals with Digital Skills to Improve Patient Care and Daily Workflows. Healthcare [Internet] 2025, 13(3). [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, H; Shah, D; Sayed, S; Horton, S; Schroeder, LF. Availability of essential diagnostics in ten low-income and middle-income countries: results from national health facility surveys. (2214-109X (Electronic)). pp. 2214–109X (Electronic)).

- Waqar, U AS; Hameed, AN; Aziz, N; Inam, H. Perioperative registries in resource-limited settings: The way forward for Pakistan. Medical College Documents. 2022;2022 feb.

- Patel, SA-O; Vashist, K; Jarhyan, P; Sharma, H; Gupta, P; Jindal, D; et al. A model for national assessment of barriers for implementing digital technology interventions to improve hypertension management in the public health care system in India. (1472-6963 (Electronic)).

- Leckenby, E; Dawoud, DA-O; Bouvy, J; Jónsson, P. The Sandbox Approach and its Potential for Use in Health Technology Assessment: A Literature Review. (1179-1896 (Electronic)).

- Salim, H; Cheong, AT; Sharif-Ghazali, S; Lee, PY; Lim, PY; Khoo, EM; et al. A self-management app to improve asthma control in adults with limited health literacy: a mixed-method feasibility study. (1472-6947 (Electronic)).

- Choukou, MA-O; Sanchez-Ramirez, DA-O; Pol, M; Uddin, M; Monnin, C; Syed-Abdul, SA-OX. COVID-19 infodemic and digital health literacy in vulnerable populations: A scoping review. (2055-2076 (Print)).

- Nazeha, NA-O; Pavagadhi, DA-O; Kyaw, BA-O; Car, JA-OX; Jimenez, GA-OX; Tudor Car, LA-O. A Digitally Competent Health Workforce: Scoping Review of Educational Frameworks. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Shi, Z; Du, X; Li, J; Hou, R; Sun, J; Marohabutr, T. Factors influencing digital health literacy among older adults: a scoping review. (2296-2565 (Electronic)).

- van Heerden, A; Young, S. Use of social media big data as a novel HIV surveillance tool in South Africa. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(10), e0239304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandi, L; Sabbatucci, M; Dallagiacoma, G; Alberti, F; Bertuccio, P; Odone, A. Digital Information Approach through Social Media among Gen Z and Millennials: The Global Scenario during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines [Internet] 2022, 10(11). [Google Scholar]

- Bhandoria, GP; Jayraj, AS; Tiwari, S; Migliorelli, F; Nelson, G; van Ramshorst, GH; et al. Use of social media for academic and professional purposes by gynecologic oncologists. (1525-1438 (Electronic)).

- Till, SA-O; Mkhize, MA-O; Farao, JA-OX; Shandu, LA-O; Muthelo, LA-O; Coleman, TA-O; et al. Digital Health Technologies for Maternal and Child Health in Africa and Other Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Cross-disciplinary Scoping Review With Stakeholder Consultation. (1438-8871 (Electronic)). pp. 1438–8871.

- Kosowicz, LA-O; Tran, KA-O; Khanh, TA-OX; Dang, TA-O; Pham, VA-OX; Ta Thi Kim, HA-O; et al. Lessons for Vietnam on the Use of Digital Technologies to Support Patient-Centered Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in the Asia-Pacific Region: Scoping Review. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Yew, SA-O; Trivedi, DA-O; Adanan, NA-OX; Chew, BA-O. Facilitators and Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Health Technologies in Hospital Settings in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries Since the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Stoyanov SA-O, Hides L Auid- Orcid: --- Fau - Kavanagh DJ, Kavanagh Dj Auid- Orcid: --- Fau - Zelenko O, Zelenko O Auid- Orcid: --- Fau - Tjondronegoro D, Tjondronegoro D Auid- Orcid: --- Fau - Mani M, Mani MA-O. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. (2291-5222 (Print)).

- Bardus, M; van Beurden, SB; Smith, JR; Abraham, C. A review and content analysis of engagement, functionality, aesthetics, information quality, and change techniques in the most popular commercial apps for weight management. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2016, 13(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irawan, AS; Alristina, AD; Laili, RD; Amalia, N; Muharram, AP; Miranda, AV; et al. Beyond the interface: benchmarking pediatric mobile health applications for monitoring child growth using the Mobile App Rating Scale. In Frontiers in Digital Health; 2025; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Baumel, AA-O; Muench, FA-O; Edan, SA-O; Kane, JA-O. Objective User Engagement With Mental Health Apps: Systematic Search and Panel-Based Usage Analysis. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Schrepp, M; Hinderks, A; Thomaschewski, J. Design and Evaluation of a Short Version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S). International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence 2017, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boring, RL; Hendrickson, SML; Forester, JA; Tran, TQ; Lois, E. Issues in benchmarking human reliability analysis methods: A literature review. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2010, 95(6), 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applying the ISO/IEC 25010 Quality Models to Software Product. In Systems, Software and Services Process Improvement; Estdale, J, Georgiadou, E, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, J; Machado, CCV; Burr, C; Cowls, J; Joshi, I; Taddeo, M; et al. The ethics of AI in health care: A mapping review. Social Science & Medicine 2020, 260, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, PA-O; Duncan, DA-O. Health App Use Among US Mobile Phone Owners: A National Survey. (2291-5222 (Print)).

- de Oliveira Collet, G; de Morais Ferreira, F; Ceron, DF; de Lourdes Calvo Fracasso, M; Santin, GC. Influence of digital health literacy on online health-related behaviors influenced by internet advertising. BMC Public Health 2024, 24(1), 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K; Van den Broucke, S; Fullam, J; Doyle, G; Pelikan, J; Slonska, Z; et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vaart, RA-O; Drossaert, CA-O. Development of the Digital Health Literacy Instrument: Measuring a Broad Spectrum of Health 1.0 and Health 2.0 Skills. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Zakar, R; Iqbal, S; Zakar, MZ; Fischer, F. COVID-19 and Health Information Seeking Behavior: Digital Health Literacy Survey amongst University Students in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet] 2021, 18(8). [Google Scholar]

- Weerasinghe, K; Scahill, SL; Pauleen, DJ; Taskin, N. Big data analytics for clinical decision-making: Understanding health sector perceptions of policy and practice. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 174, 121222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C; Guttersrud, Ø; Levin-Zamir, D; Griebler, R; Finbråten, HS. Associations between digital health literacy and health system navigating abilities among Norwegian adolescents: validating the HLS(19)-DIGI scale using Rasch modeling. (1471-2458 (Electronic)).

- Smith, B; Magnani, JW. New technologies, new disparities: The intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. (1874-1754 (Electronic)). (Electronic)).

- Norman, CD; Skinner, HA. eHealth Literacy: Essential Skills for Consumer Health in a Networked World. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Latulippe, KA-O; Hamel, CA-O; Giroux, DA-O. Social Health Inequalities and eHealth: A Literature Review With Qualitative Synthesis of Theoretical and Empirical Studies. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Golder, S; Ahmed, S; Norman, G; Booth, A. Attitudes Toward the Ethics of Research Using Social Media: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2017, 19(6), e195. [Google Scholar]

- Bosslet, GT; Torke Am Fau - Hickman, SE; Hickman Se Fau - Terry, CL; Terry Cl Fau - Helft, PR; Helft, PR. The patient-doctor relationship and online social networks: results of a national survey. (1525-1497 (Electronic)).

- Golder, S; Bach, M; O’Connor, K; Gross, R; Hennessy, S; Gonzalez Hernandez, G. Public Perspectives on Anti-Diabetic Drugs: Exploratory Analysis of Twitter Posts. JMIR Diabetes 2021, 6(1), e24681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, C; Lyons Rf Fau - Warner, G; Warner, G; Fau - Hobfoll, SE; Hobfoll Se Fau - Martens, PJ; Martens Pj Fau - Labonté, R; Labonté, R; Fau - Brown, RE; et al. Conservation of resources theory and research use in health systems. (1748-5908 (Electronic)).

- Bour, CA-O; Ahne, AA-O; Schmitz, SA-O; Perchoux, CA-O; Dessenne, CA-O; Fagherazzi, GA-O. The Use of Social Media for Health Research Purposes: Scoping Review. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Eysenbach, G. Infodemiology and infoveillance tracking online health information and cyberbehavior for public health. (1873-2607 (Electronic)).

- Rayes, IK; Hassali, MA; Abduelkarem, AR. The role of pharmacists in developing countries: The current scenario in the United Arab Emirates. (1319-0164 (Print)).

- Merchant, RM; Lurie, N. Social Media and Emergency Preparedness in Response to Novel Coronavirus. JAMA 2020, 323(20), 2011–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. (1052-1372 (Print)).

- Grajales, FJrA-O; Sheps, S; Fau - Ho, K; Ho, K; Fau - Novak-Lauscher, H; Novak-Lauscher, H; Fau - Eysenbach, G; Eysenbach, GA-O. Social media: a review and tutorial of applications in medicine and health care. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Daniel, F; Jabak, S; Sasso, R; Chamoun, Y; Tamim, H. Patient-Physician Communication in the Era of Mobile Phones and Social Media Apps: Cross-Sectional Observational Study on Lebanese Physicians’ Perceptions and Attitudes. JMIR Med Inform 2018, 6(2), e18. [Google Scholar]

- Santillana, M; Nguyen, AT; Dredze, M; Paul, MJ; Nsoesie, EO; Brownstein, JS. Combining Search, Social Media, and Traditional Data Sources to Improve Influenza Surveillance. (1553-7358 (Electronic)).

- Gomes, AA-O; Santos, GA-O; Bastos, IA-O; Sales, JA-O; Perrelli, JA-O; Frazão, CA-O. Social determinants of health literacy in children and adolescents: a scoping review. (1983-1447 (Electronic)).

- Miranda, AV; Sirmareza, T; Nugraha, RR; Rastuti, M; Syahidi, H; Asmara, R; et al. Towards stunting eradication in Indonesia: Time to invest in community health workers. Public Health Challenges 2023, 2(3), e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kbaier, DA-O; Kane, AA-O; McJury, MA-O; Kenny, IA-OX. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media-Challenges and Mitigation Before, During, and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Literature Review. (1438-8871 (Electronic)).

- Ahmed, MM; Okesanya, OJ; Olaleke, NO; Adigun, OA; Adebayo, UO; Oso, TA; et al. Integrating Digital Health Innovations to Achieve Universal Health Coverage: Promoting Health Outcomes and Quality Through Global Public Health Equity. Healthcare [Internet] 2025, 13(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denecke, K; Rivera-Romero, O; Giunti, G; Van Holten, K; Gabarron, E. Key Components of Participatory Design Workshops for Digital Health Solutions: Nominal Group Technique and Feasibility Study. Journal of Healthcare Informatics Research 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli, R; Bohara, D; Kc, M; Shanmuganathan, S; Mistry, SK; Yadav, UN. Challenges and opportunities for implementing digital health interventions in Nepal: A rapid review. (2673-253X (Electronic)).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).