1. Introduction

Climate change and the associated rise in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have become critical challenges for the global construction industry. The built environment contributes nearly 40% of global CO₂ emissions when material production, construction activities, and energy use are considered (IPCC, 2021) [

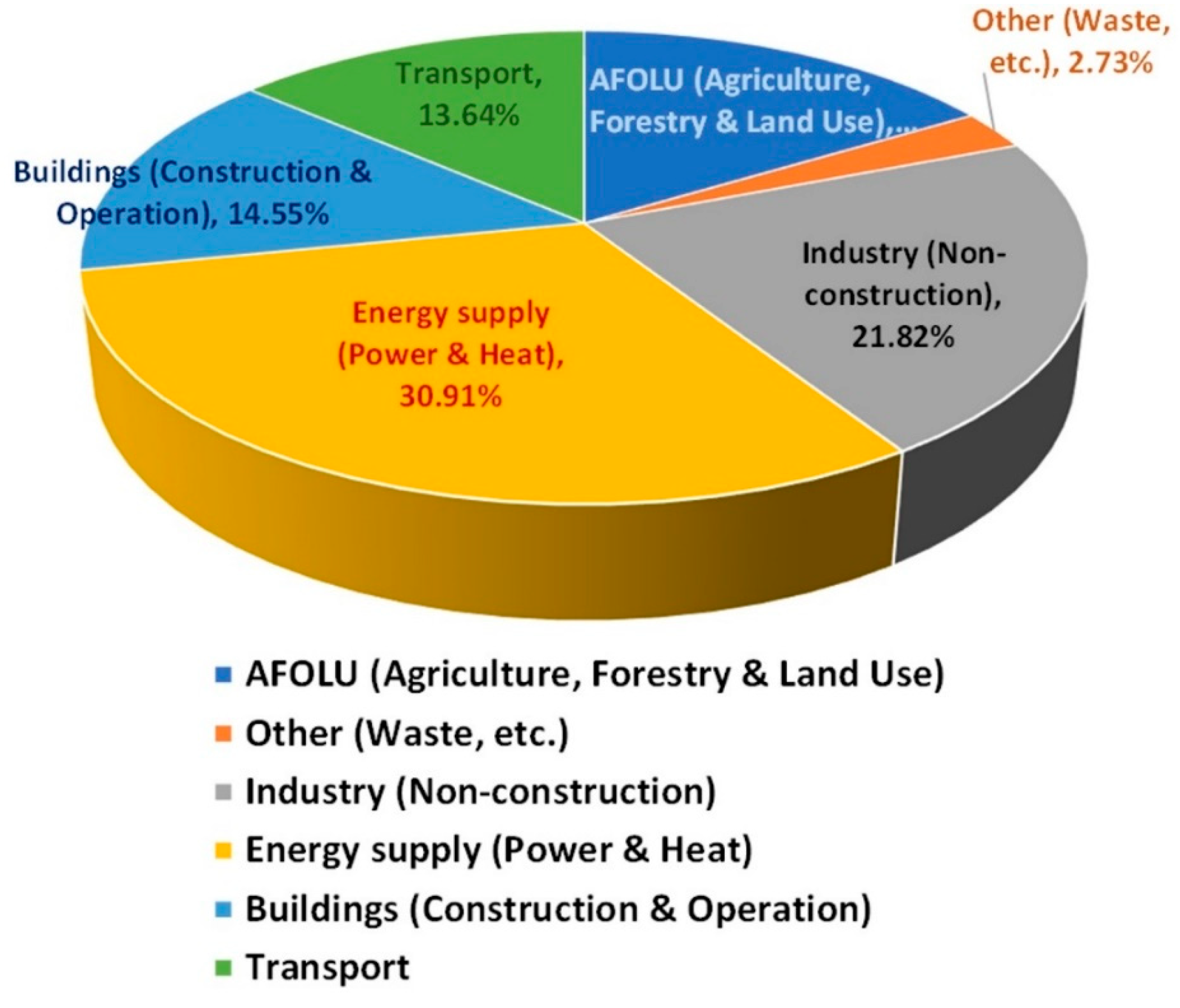

1]. Infrastructure projects represent a significant portion of this impact due to their large scale and intensive use of construction materials. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the construction sector accounts for a substantial share of global GHG emissions, underscoring the importance of material-related mitigation strategies.

Long-span bridges are among the most material-intensive infrastructure systems, requiring large quantities of cementitious materials, reinforcing steel, and structural steel to satisfy structural safety, durability, and serviceability requirements (Xiao et al., 2025) [

2]. Among these materials, structural steel plays a central role in modern bridge engineering. Owing to its high strength-to-weight ratio, excellent ductility, and predictable mechanical behavior, steel enables efficient structural systems capable of spanning long distances with reduced self-weight. These properties allow for slimmer structural members, lower foundation demands, and improved seismic performance.

In addition to its mechanical advantages, steel offers significant constructability benefits. Steel components can be prefabricated off-site with high dimensional accuracy, allowing modular assembly and rapid erection. Such construction methods shorten project duration, enhance quality control, and reduce on-site environmental disturbance. Steel structures are also highly adaptable to complex geometries, making them particularly suitable for cable-stayed and truss bridge systems. Furthermore, steel exhibits superior recyclability, with high recovery rates at the end of service life, supporting circular construction practices.

Bridges also serve important social, cultural, and symbolic roles beyond their functional purpose.

Table 1 presents representative iconic bridges worldwide, highlighting their spans, primary functions, and cultural significance. Many of these landmark structures rely heavily on steel or steel–concrete composite systems, reflecting the long-standing importance of steel as a construction material for large-span applications. In Taiwan, projects such as the Gaoping River Bridge and the Suhua Highway Improvement Project similarly demonstrate how steel-intensive bridge construction supports both engineering performance and national infrastructure development.

Despite these advantages, steel production is energy-intensive and associated with relatively high embodied carbon, particularly in regions where blast furnace–basic oxygen furnace processes dominate manufacturing (Zhao et al., 2025) [

6]; (Huang et al., 2023) [

7]. Previous studies indicate that construction materials typically account for 70–90% of total embodied carbon in bridge projects, with structural steel and reinforcing steel being the dominant contributors [

6,

7]. Consequently, understanding the carbon implications of steel use—while recognizing its structural and constructional benefits—is essential for advancing sustainable bridge engineering.

International sustainability frameworks such as the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015) [

3], ISO 14067 (ISO, 2018) [

4], and PAS 2050 (BSI, 2011) [

5] provide standardized methodologies for carbon footprint quantification. Taiwan has adopted these principles through Environmental Protection Administration guidelines for public construction projects [

10]. While life-cycle assessment approaches are widely applied to buildings and infrastructure (Gabriel, 2014) [

9], construction-stage emissions deserve particular attention because material selection, fabrication, transportation, and erection methods are largely determined at this phase and offer immediate opportunities for emission reduction.

Existing research in Taiwan has primarily focused on highways, tunnels, and earth-retaining structures, where concrete dominates material use (Shau, 2019) [

8]; (Liu et al., 2023) [

11]. Comparatively fewer studies have examined long-span bridge projects characterized by extensive use of structural steel, stay cables, and prefabricated steel components. In such projects, construction-stage decisions related to material sourcing, steel fabrication, erection sequencing, and temporary works can significantly influence embodied carbon while also affecting safety, quality, and constructability.

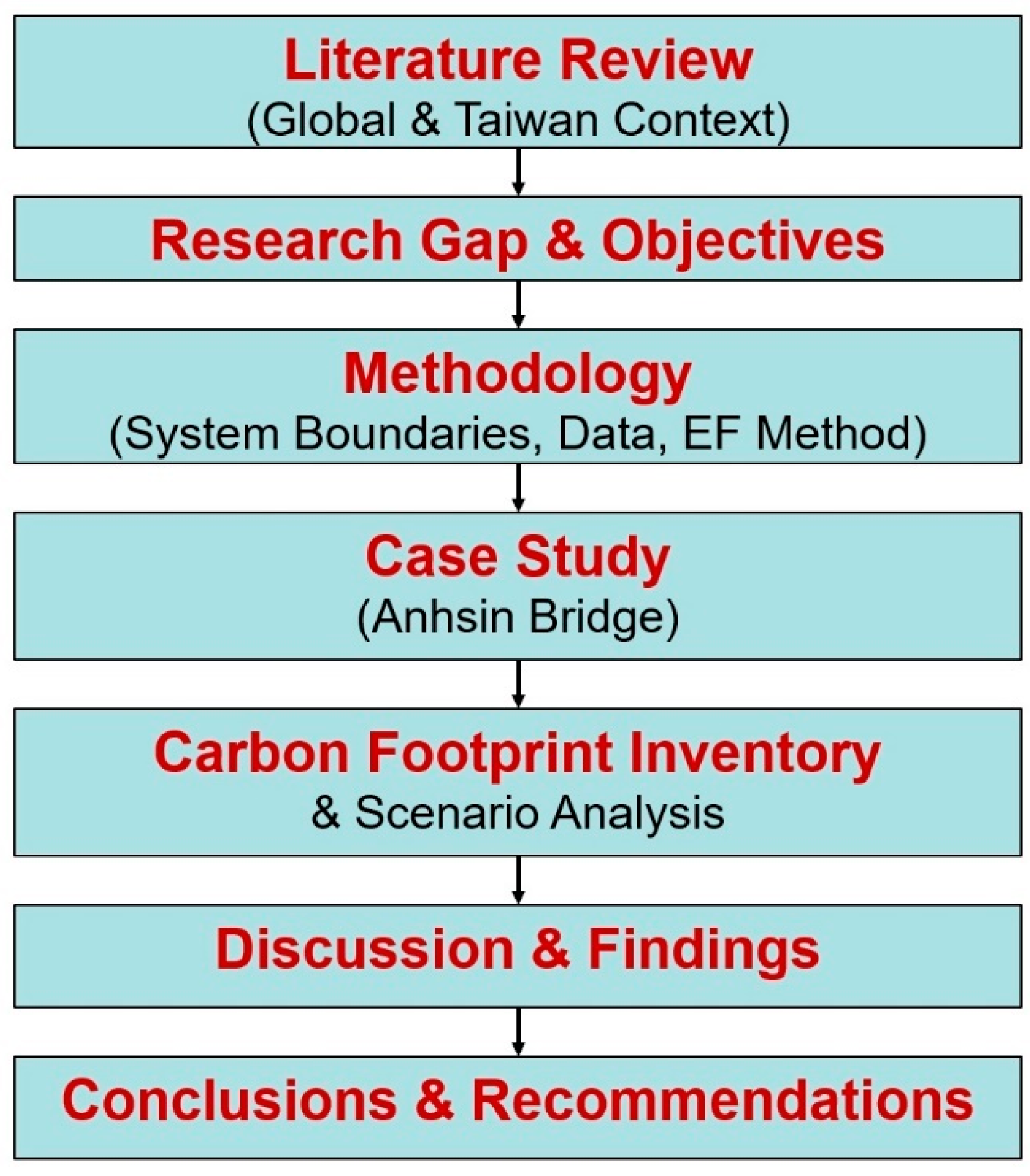

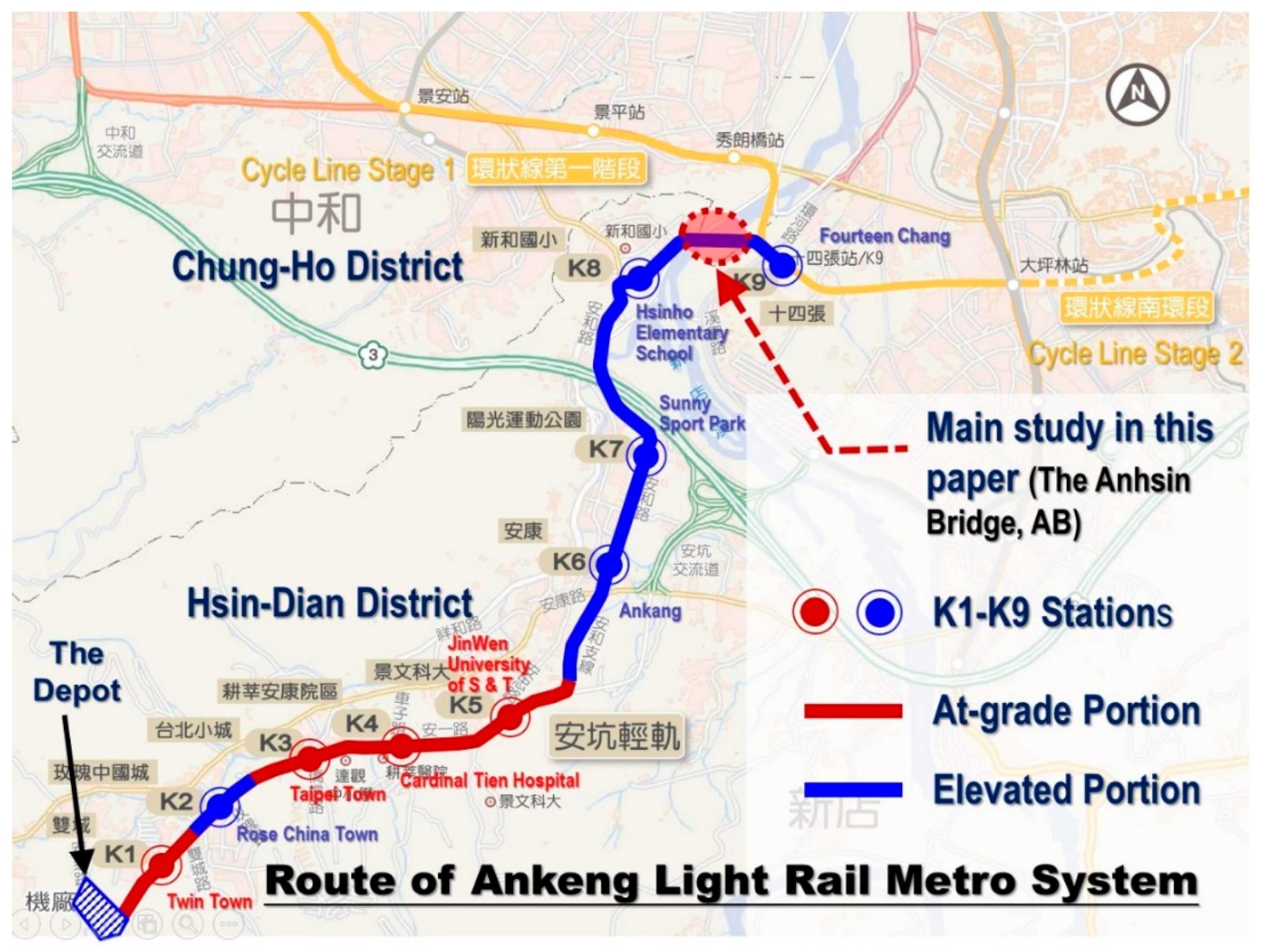

The Anhsin Bridge, a single-pylon asymmetric cable-stayed steel truss bridge constructed as part of the Ankeng Light Rail Metro system in New Taipei City, Taiwan, provides a representative case for investigating the material-driven carbon footprint of long-span bridge construction. The bridge incorporates large quantities of structural steel, reinforcing steel, composite deck systems, and temporary steel works, making it particularly relevant to research at the intersection of construction materials and sustainability. The overall research framework adopted in this study is presented in

Figure 2, outlining the systematic process used to quantify emissions and evaluate mitigation strategies.

Accordingly, this study aims to quantify the construction-stage carbon footprint of a steel-intensive bridge, identify material-related emission hotspots, and assess practical reduction strategies compatible with current construction practice. By focusing on construction materials—particularly the performance, constructability, and recyclability of steel—this research provides empirical evidence to support more sustainable use of steel and composite materials in long-span bridge engineering.

2. Literature Review and Methodology

Over the past two decades, carbon management in civil infrastructure has become a central research and policy concern. The IPCC (2021) [

1] identifies the built environment as a major contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with infrastructure projects—bridges, highways, and tunnels—accounting for substantial embodied carbon (Xiao et al., 2025) [

2]. Global initiatives such as the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015) [

3] and ISO 14067 (2018) [

4] have established international standards, while Taiwan has committed to net-zero by 2050 through EPA guidelines (2010) [

10].

Recent studies provide practical insights. Bechtel Ltd. (2021) [

12] emphasized how contractors integrate sustainability into performance strategies. Hao et al. (2020) [

13] showed that BIM-based prefabrication can cut material-stage emissions, while Juenger et al. (2019) [

14] highlighted the potential of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). Bai et al. (2024) [

15] and Cao et al. (2024) [

16] confirmed that bridges are especially carbon-intensive, with Bannazadeh et al. (2012) [

17] reporting significant reductions in an EU cable-stayed bridge through material substitution. Heenkenda et al. (2022) [

18] stressed innovation capacity, Ricchiuti et al. (2024) [

19] reviewed adoption barriers, and Tu et al. (2020) [

20] proposed market instruments such as tradable green certificates. At the national level, MOTC (2022) [

21] highlighted the integration of carbon metrics into infrastructure statistics, while Taiwan’s Comprehensive Carbon Reduction Action Plan (National Development, 2025) [

22] set sectoral strategies for the 2050 net-zero target.

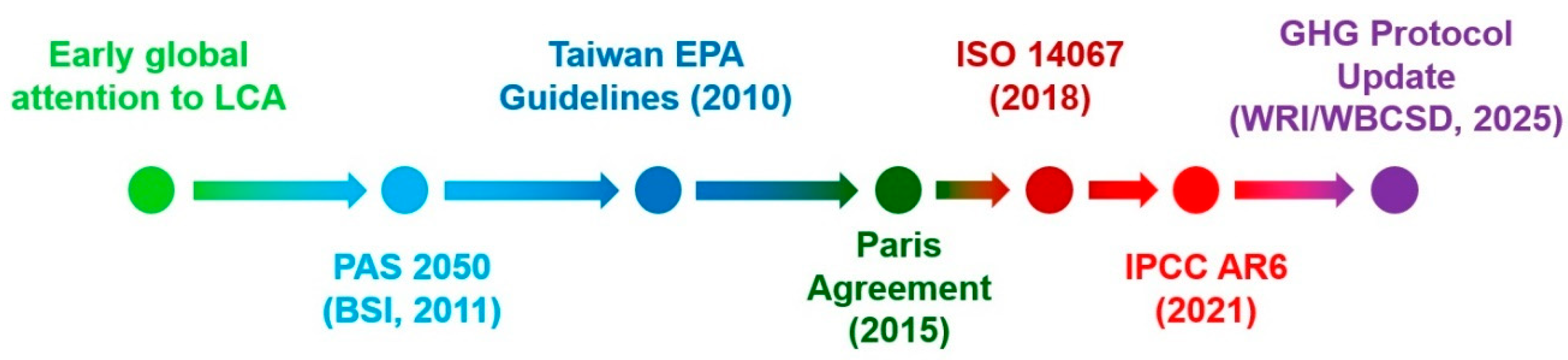

Figure 3 shows the evolution of carbon management initiatives since 2000.

Robust methodologies are critical for consistent assessment. Internationally, PAS 2050 (BSI, 2011) [

5], the GHG Protocol (WRI/WBCSD, 2025) [

23], and ISO 14067 (2018) [

4] dominate, while Taiwan localized them through EPA guidelines (2010) [

10]. These rely on the emission factor method, where the carbon footprint is expressed as:

Here, ADi represents activity data and EFi the emission factor. Process-based life-cycle assessment (LCA) is widely used for precision, though hybrid input–output models can capture upstream emissions (Gabriel, 2014) [

9]. For bridge projects, process-based methods remain most practical (Huang et al., 2023) [

7].

Table 2 summarizes major standards for carbon footprint studies.

Research has examined highways, tunnels, slopes, and bridges. Zhao et al. (2025) [

6] found material emissions represented over 80% of highway totals, while Shau (2019) [

8] showed concrete and reinforcing steel dominated Taiwan’s Suhua Highway Improvement Project. Liu et al. (2023) [

11] demonstrated that alternative retaining methods can reduce emissions and costs. For bridges, Xiao et al. (2025) [

2] showed higher embodied emissions than road projects due to steel and cables, while Huang et al. (2023) [

7] reported 10–20% reductions through material substitution and equipment optimization. Despite these advances, gaps remain: few studies isolate the construction stage, evaluate cost implications, or address Taiwan’s landmark bridges.

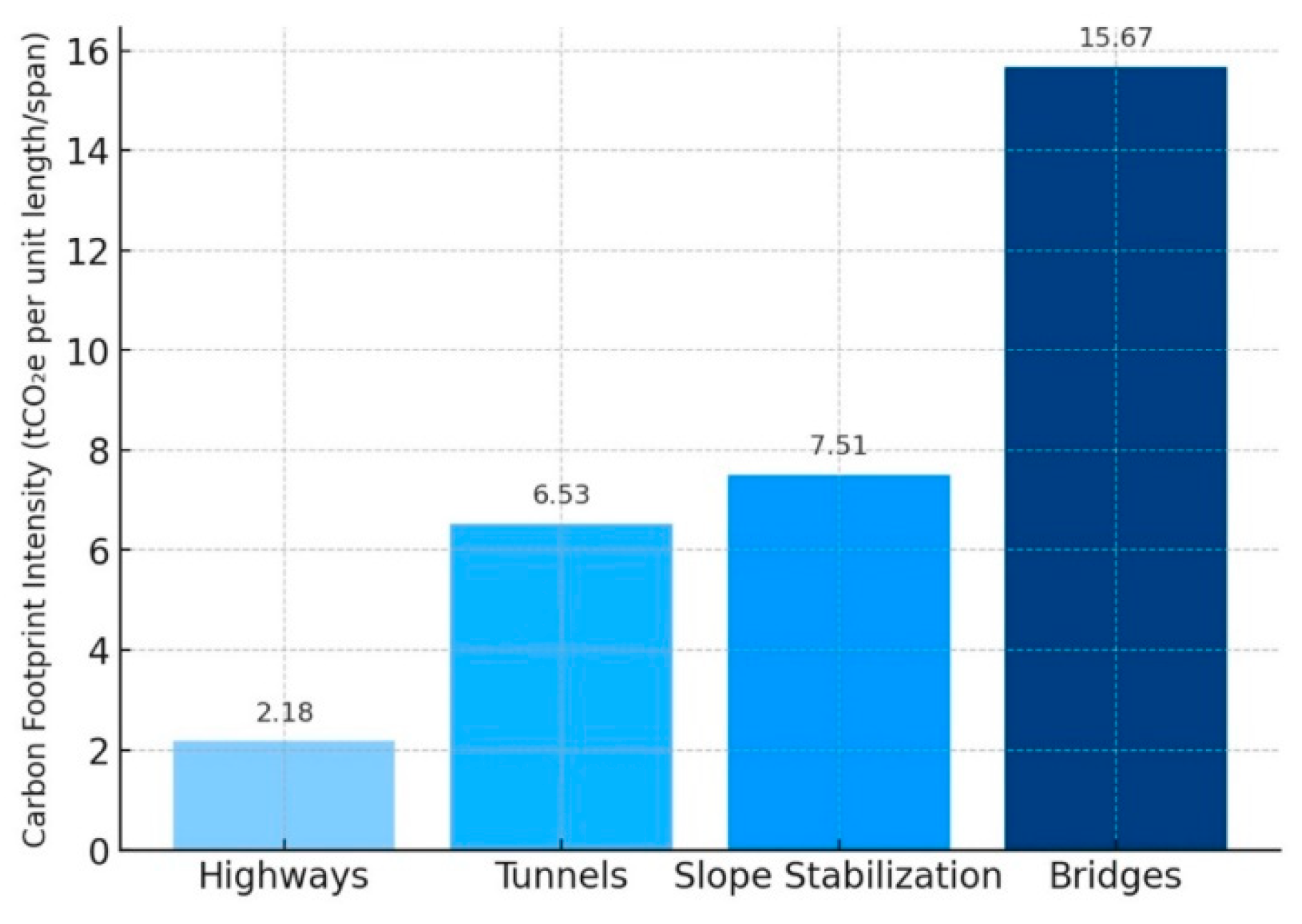

Figure 4 compares selected infrastructure studies, showing the disproportionately high emissions of bridges [

8,

10,

15,

23].

This study applies the emission factor method to assess the Anhsin Bridge construction stage. The system boundary is cradle-to-gate, covering material production, transport, processes, temporary works, and equipment, while excluding operation, maintenance, and end-of-life. The functional unit is one completed bridge. Activity data include cement, aggregates, SCMs, reinforcing steel, structural steel, cables, paint, diesel, and electricity, sourced from project documentation and contractor records. Emission factors were drawn from Taiwan EPA (2010) [

10] and CCRAP (2025) [

22], supplemented with international data.

Three scenarios were evaluated against the baseline: (1) 40% substitution of cement with SCMs, (2) optimized erection methods to reduce temporary works, and (3) enhanced formwork reuse.

Table 3 presents the emission factors applied in this study.

This methodology ensures comparability with international studies while reflecting Taiwan’s local context, enabling a robust evaluation of mitigation strategies for sustainable bridge construction.

3. Methodology

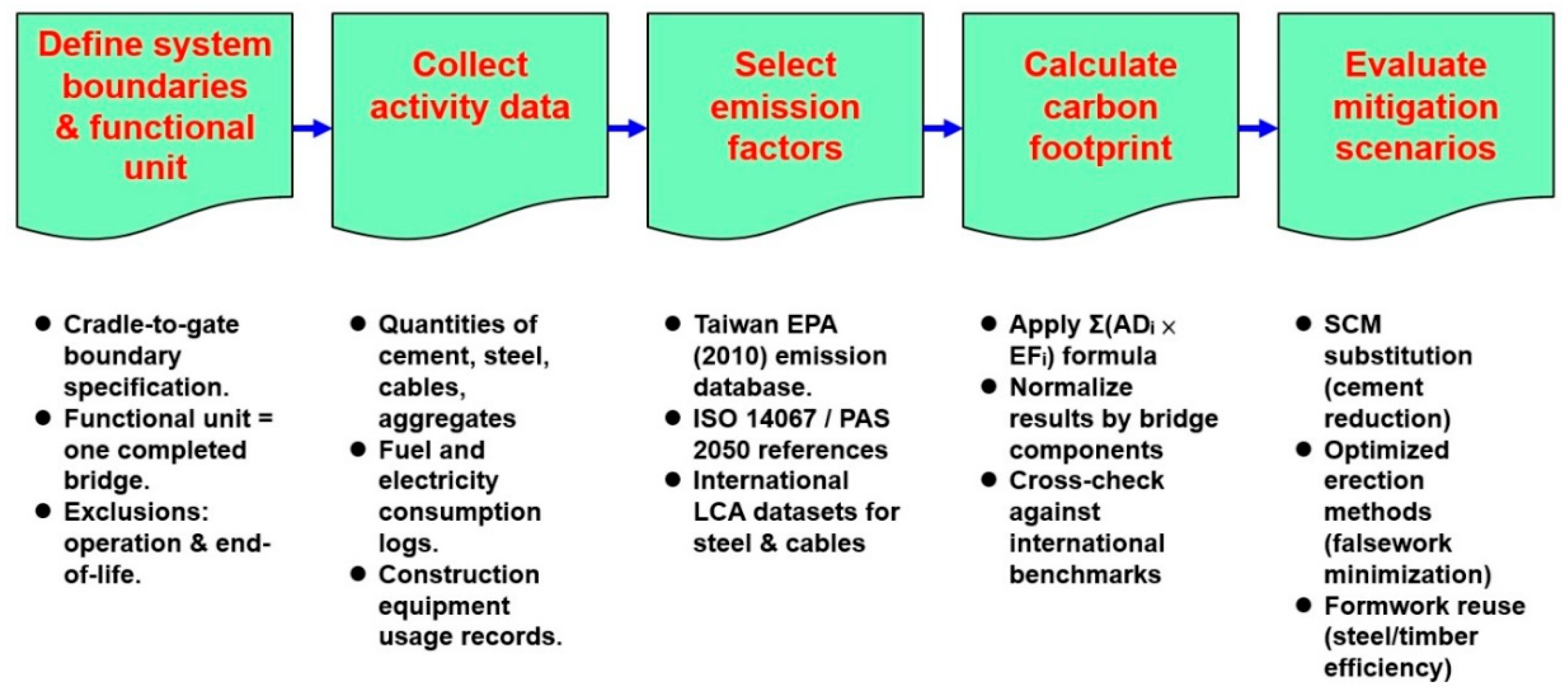

This study employed a structured methodology to quantify the carbon footprint of the Anhsin Bridge during the construction stage, integrating ISO 14067, PAS 2050, the GHG Protocol (2025), and Taiwan EPA guidelines to ensure both comparability and policy relevance. The process followed five tasks: define boundaries and functional unit, collect activity data, select emission factors, calculate emissions, and evaluate mitigation scenarios.

Figure 5 presents the overall methodological flow and sub-activities.

The boundary was defined as cradle-to-gate, including raw material production, transport, and all construction activities. Excluded were operation, maintenance, and end-of-life phases, focusing on construction-phase mitigation. Inclusions covered cement, aggregates, SCMs, reinforcing and structural steel, cables, asphalt, equipment use, temporary works, and site energy. The functional unit was the entire Anhsin Bridge.

Table 4 summarizes boundary inclusions and exclusions.

Data were sourced from project records (BOQ, procurement logs, contractor reports) [

24], on-site measurements of fuel and electricity, and supplier data for cement, steel, and cables, adjusted to Taiwan’s manufacturing processes. Cross-checking invoices and daily logs improved accuracy. Key inputs included about 92,000 m³ of concrete, 17,500 tons of reinforcing steel, 6,800 tons of structural steel, 1,200 tons of cables, 0.9 million liters of diesel, and 1.6 million kWh of electricity.

The emission factor method (Equation 1) was used, combining activity data with recognized emission factors. Sources included Taiwan EPA (2010) [

10], CCRAP (2025) [

22], and international databases. Materials assessed included cement, concrete, reinforcing steel, structural steel, stay cables, and paint, as well as diesel and electricity. The complete set of factors is shown in

Table 3.

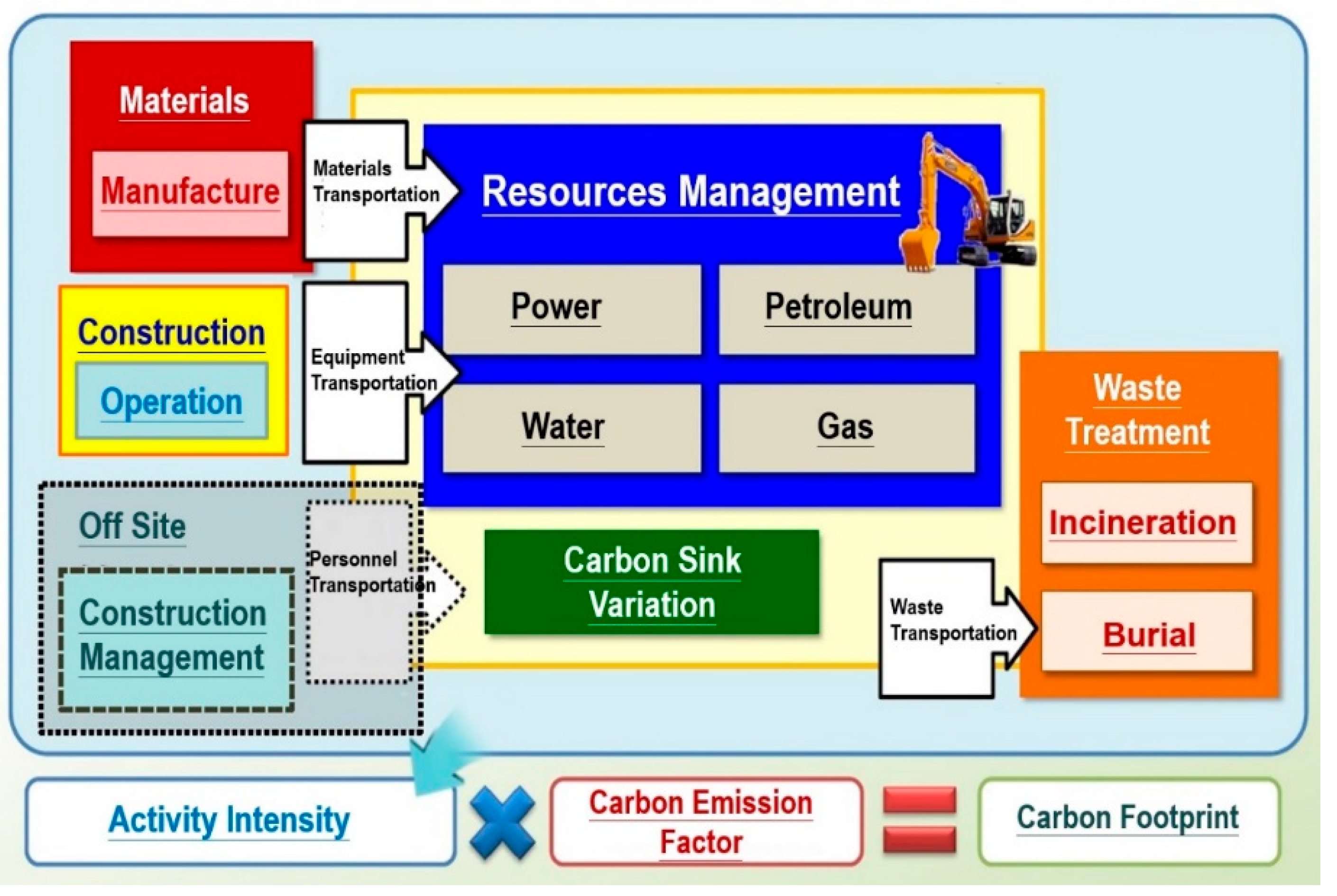

Figure 6 illustrates the integration of activity data and emission factors [

4,

8,

10].

Three reduction scenarios were evaluated. The SCM Substitution Scenario applied a 40% replacement of Portland cement with fly ash and slag. The Optimized Construction Scenario employed barge-mounted cranes to reduce temporary falsework and cofferdams. The Formwork Reuse Scenario increased reuse frequency of steel and timber formwork. Scenarios were modeled by adjusting activity data across multiple sectors and recalculating emissions. They were contextualized within Taiwan’s broader governance framework, including sectoral allocation of reduction responsibilities, progressive verification of 2030 targets, and institutional innovations such as carbon pricing.

Figure 7 shows projected carbon emissions in Taiwan by sector, highlighting the 27% reduction target for 2030 and the pathway toward net-zero by 2050 [

10,

22].

5. Discussion and Findings

5.1. Interpretation of Carbon Footprint Results

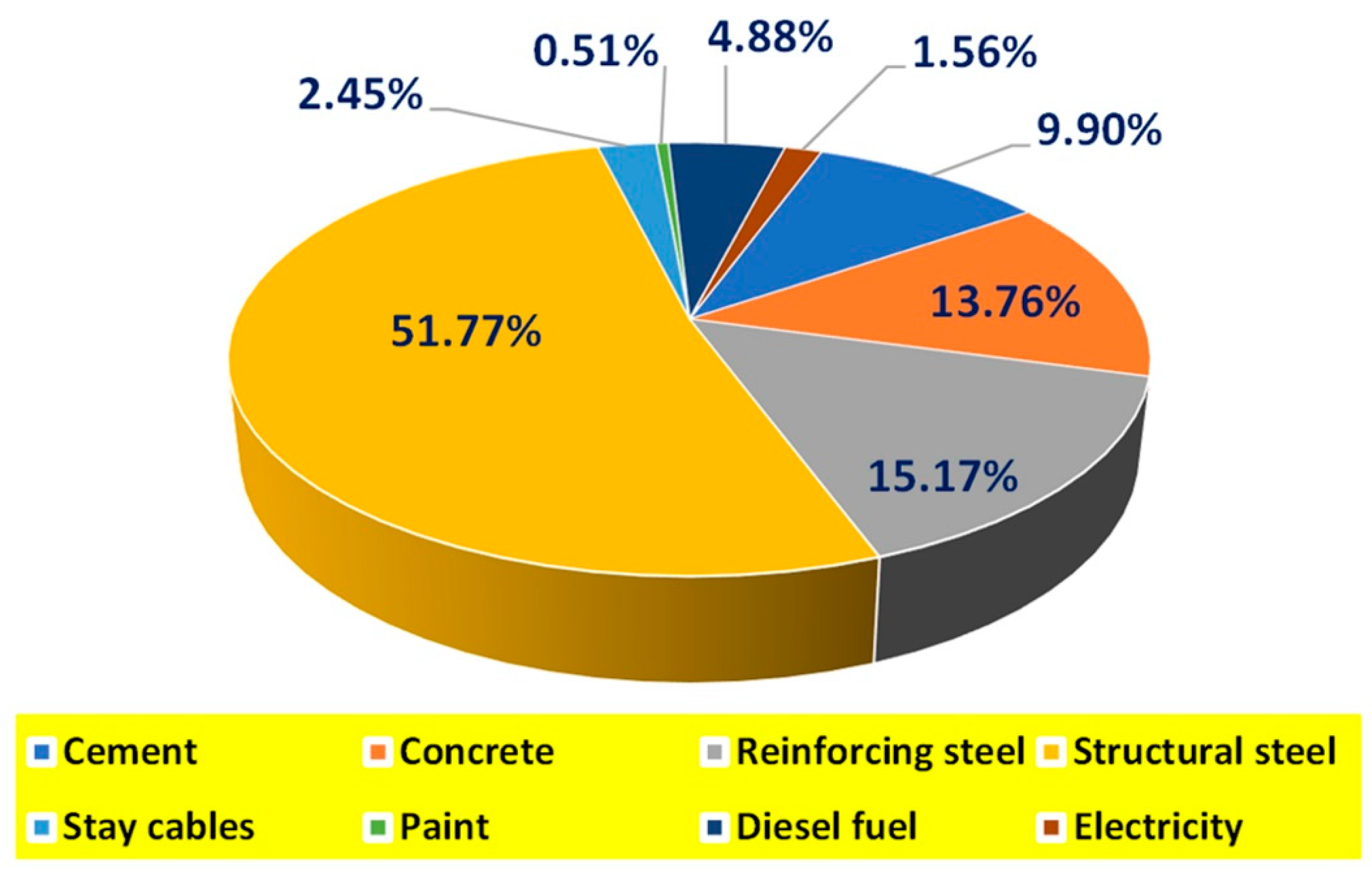

The inventory in

Section 4 showed total construction-stage emissions of 55,349 tCO₂e for the Anhsin Bridge. Materials dominated, with structural steel the largest contributor (51.77%), followed by reinforcing steel (15.17%), concrete (13.76%), and cement (9.90%). Together, these accounted for over 90% of emissions. Stay cables (2.45%) and paint (0.51%) added smaller shares.

Equipment and energy use contributed modestly: diesel fuel 4.88% and electricity 1.56%. While relatively small, these categories point to opportunities for logistics efficiency and equipment electrification.

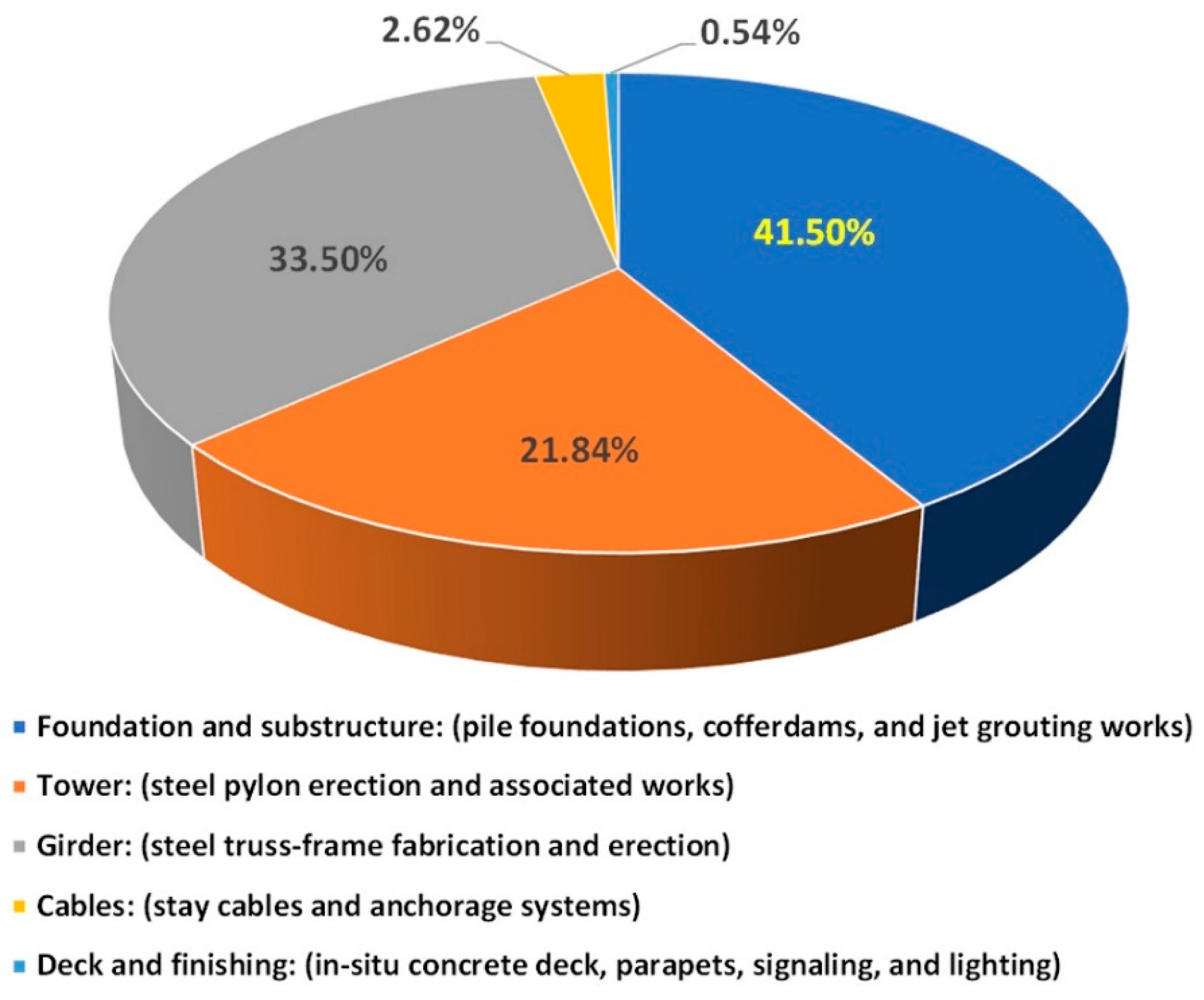

At the component level, foundations and substructure (41.50%) and the truss girder (33.50%) accounted for most emissions, while the tower (21.84%), cables (2.62%), and deck (0.55%) were minor. This confirms that steel-intensive elements largely shape embodied carbon.

Two key insights emerge: (1) structural form strongly affects emissions, as the asymmetrical cable-stayed truss increased steel demand, raising intensity; (2) incremental material and method improvements, including SCM substitution and extended reuse of temporary works, offer meaningful reductions. These findings are consistent with life-cycle assessment advances emphasizing robust inventories and methodological clarity (Finnveden et al., 2009) [

27].

5.2. Comparative Insights with International Bridge Projects

Benchmarking shows that the Anhsin Bridge’s emissions align with international cases. Bai et al. (2024) [

15] reported 70,000–95,000 tCO₂e for Japanese bridges, while Hao et al. (2020) [

13] identified 8–15% reductions via material substitution in Asian projects. Bannazadeh et al. (2012) [

17] documented ~20% reductions in a European bridge through high SCM substitution and recycled reinforcing steel.

Taiwan’s outcomes were constrained by limited recycled steel and higher emission factors from domestic blast-furnace production, despite established guidelines (EPA, 2010) [

10]. This highlights a gap between policy and practice.

Table 7 compares bridge projects internationally. With 55,349 tCO₂e and a main span of 180 m, the Anhsin Bridge records 307 tCO₂e/m, lower than an earlier estimate (433), and closer to peers such as the Tatara Bridge (327) and EU case (357), though still higher than Korea’s Incheon Bridge (393).

5.3. Evaluation of Reduction Scenarios

Three scenarios were analyzed against the baseline of 55,349 tCO₂e.

SCM substitution reduced 2,458 tCO₂e (−4.4%), the most impactful strategy. This mirrors global evidence, but wider adoption faces supply constraints and conservative construction practices.

Optimized erection methods cut 1,281 tCO₂e (−2.3%). Benefits extended beyond carbon savings, including reduced hydrological disturbance, shorter duration, and better safety, though costs increased slightly.

Formwork reuse avoided 309 tCO₂e (−0.6%). Though small in effect, it is cost-neutral and supports circular practices.

Together, the three measures achieved 4,048 tCO₂e (−7.3%), a modest share of the total but significant in targeting high-emission categories like cement and diesel. These results illustrate that even incremental measures can set foundations for broader adoption of sustainable practices.

5.4. Policy and Practical Implications

The findings hold implications for both policy and practice in Taiwan.

Policy. (1) Innovation capacity should be strengthened through government support for SCMs, low-carbon steelmaking, and electrified equipment. (2) Performance-based specifications should replace prescriptive standards to allow greater flexibility in sustainable materials. (3) Supply chains for SCMs, recycled steel, and alternative fuels need investment. (4) Public works should integrate sustainability metrics into MOTC’s statistical framework, aligning projects with Taiwan’s 2030 and 2050 goals.

Practice. (1) Design choices should explicitly include embodied carbon alongside cost and safety. (2) Construction logistics, including optimized erection and reduced temporary works, can enhance efficiency. (3) Lessons from the Anhsin Bridge should be codified into guidelines for wider dissemination.

Broader lessons. Achievable reductions (~7.3%) remain insufficient to align with net-zero goals. Deeper change requires systemic innovation in material production (e.g., green steel, alternative binders), expanded SCM supply, and stronger integration of carbon accounting into procurement. This is consistent with research highlighting the role of innovation, construction-phase sustainability, and policy instruments in enabling sectoral transition.

Figure 14 illustrates a progressive pathway to carbon neutrality, combining project-level strategies with sector-wide transformations in materials, electrification, and policy [

22,

27].

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

This study presented a detailed construction-stage carbon footprint assessment of the Anhsin Bridge, focusing on the role of construction materials in shaping embodied greenhouse gas emissions. Total emissions were estimated at 55,349 tCO₂e, confirming that material production dominates the carbon profile of long-span bridge construction. Structural steel was the largest contributor, accounting for more than half of the total emissions, while reinforcing steel, concrete, and cement together contributed approximately 39%. These findings are consistent with international observations that steel-intensive bridge systems are inherently material-driven in terms of embodied carbon.

Despite its high emission intensity during production, structural steel demonstrated substantial advantages from a construction materials perspective. Its high strength-to-weight ratio enabled efficient structural forms and reduced foundation demands, while excellent ductility and fatigue resistance supported safety and durability requirements. The extensive use of prefabricated steel components facilitated modular construction, shortened erection time, improved quality control, and reduced on-site environmental disturbance. Moreover, the high recyclability of steel provides a strong foundation for circular construction practices and future integration of low-carbon or green steel technologies.

The evaluation of mitigation strategies showed that material-oriented and construction-stage interventions can deliver meaningful emission reductions. Supplementary cementitious material substitution achieved the largest single reduction, while optimized steel erection methods and increased formwork reuse further reduced emissions associated with temporary works and equipment use. The combined reduction of 7.3% demonstrates that incremental, technically feasible measures can effectively target high-emission materials without compromising structural performance or constructability.

Comparative analysis indicates that the emission intensity of the Anhsin Bridge is within the range of comparable international steel bridge projects, though still influenced by reliance on virgin steel and conventional production routes. This highlights the importance of advancing low-carbon steel supply chains, promoting recycled steel use, and adopting performance-based material specifications in public infrastructure projects.

From the perspective of Construction Materials, the findings underscore that achieving substantial carbon reductions in steel-intensive infrastructure will require both project-level optimization and systemic innovation in material production, recycling, and procurement. Future research should extend the analysis to full life-cycle stages, investigate the application of recycled and green steel, and develop localized emission factors for construction materials. Such efforts will be essential to support the transition toward low-carbon, high-performance steel bridge construction aligned with long-term climate targets.

6.2. Recommendations

Policy. Implement performance-based material specifications, strengthen SCM supply chains, incentivize low-carbon steelmaking, and mandate embodied carbon disclosure for public works to enhance transparency.

Practice. Incorporate carbon metrics into design and tender evaluations, improve construction logistics through advanced erection planning, and institutionalize material reuse to foster circularity.

Research. Develop localized emission factors for higher accuracy, investigate green steel and alternative binders, and expand multi-project datasets for robust benchmarking.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study assessed only the construction stage. While transparent, the emission factor method remains sensitive to database assumptions and material sourcing. Future work should expand to full life-cycle assessments, evaluate prefabrication and equipment electrification, and compare results across bridge types and regions. Such efforts would strengthen empirical benchmarks and support Taiwan’s pathway to its 2030 and 2050 net-zero commitments.