1. Introduction

Millions of people around the world have recovered from the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 disease since the COVID-19 pandemic began in late 2019. A big chunk of these people still has ongoing neurological, cognitive, and psychosocial issues that

are still there weeks, months, or even years after healing. This prolonged illness, also known as LongCOVID or Post-AcuteSequelaeofSARS-CoV-2 (PASC), has become a major global health problem. According to longitudinal studies, 20–40 percent of people who have been affected have neurological symptoms that last longer than six months. These symptoms have a big impact on their quality of life, work performance, and mental health. Acute COVID-19 mostly affects the breathing system, but Long COVID has shown that the virus has a wide range of effects on the brain and nerves. The neurological symptoms of Long COVID are different and often make it impossible to do anything. Many people have long-lasting headaches, loss of smell, dysautonomia, cognitive problems, constant fatigue, anxiety, depression, and trouble sleeping. Nerve damage, seizures, dementia, and sudden ischemic events are all signs of severe cases. These signs, which can be seen in people with mild infections at first, show how complicated SARS-CoV-2’s effects on the nervous system are. Both doctors and researchers agree that COVID-19’s effects on the nervous system could be a big long-term public health issue after the pandemic is over. Studies have shown that the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 infection on the nervous system are caused by a number of different paths working together. Direct viral neuroinvasion is one method, in which viral particles may infiltrate the central nervous system (CNS) through the olfactory epithelium or hematogenous pathways. Moreover, microvascular injury, marked by en dothelial cell destruction, microthrombi formation, and compromised cerebral perfusion, has been frequently documented in neuroimaging and autopsy findings. The systemic inflammatory responseincluding cytokine storms, immunological dysregulation and chronic neuro-inflammation, is a significant consequence. It may involve neuronal signals and causes acceleration in brain degeneration. Breaking the blood-brain barrier (BBB) permits immune cells and drugs responsible for inflammation get into the brain, making it even more severe. Hypoxia due to respiratory impairment can lead to neuronal damage, particularly in susceptible brain areas associated with memory, olfaction, and executive function

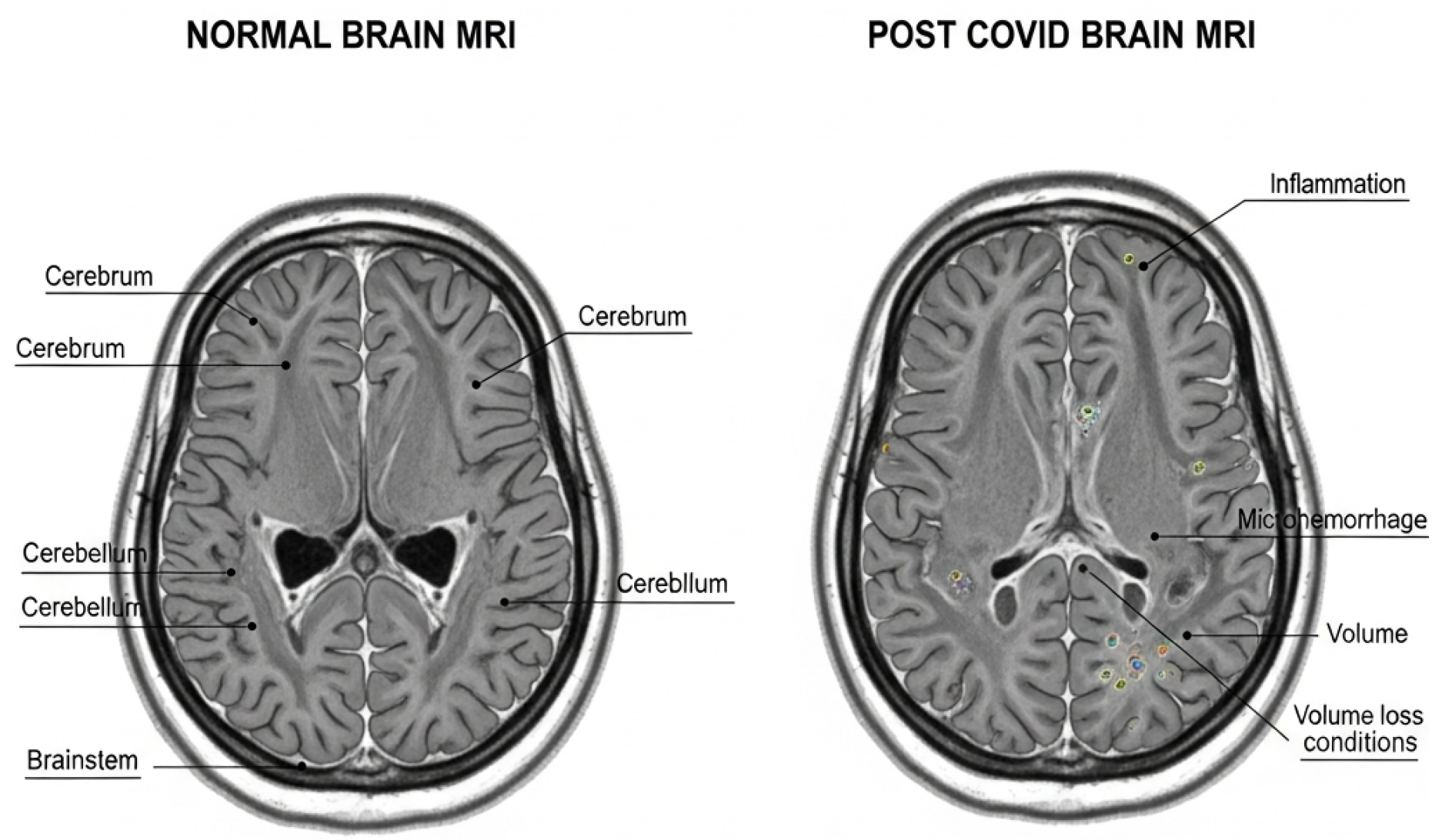

MRI images of the brain illustrated in (

Figure 1) the virus’s decent yet clinically significant impacts on the brain. The cortex and subcortical regions stay the same in a healthy brain. However, post-COVID studies show inflammation, microhemorrhages, and initial cortical volume loss.These changes are linked to damage to small blood vessels and inflammation caused by the immune system. These problems are related to long-lasting symptoms like migraines, memory loss, and problems with thinking and memory that COVID-19 patients have experienced.

Progress in neuroimaging has yielded significant insights into these pathological alterations. Research deploying magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and functional MRI (fMRI) has identified many anomalies in patients with Long COVID. Studies on post-COVID patients show several brain-related changes. These include white-matter changes that may indicate nerve fiber damage, shrinkage of the hippocampus and olfactory areas linked to memory loss and loss of smell, and reduced gray matter in the frontal and temporal regions.

Because these neurological effects are difficult to identify, there is a strong need for automatic and objective computational tools. Deep learning models like CNNs, transformers, autoencoders, and graph neural networks can help to enhance diagnostic accuracy and help identify early symptoms of long-term neurological and cognitive problems.

With an increase in access to different types of brain imaging scans and clinical biomarkers, it is now possible to construct an integrated diagnostic systems to analyze structural, functional, and molecular information together. Since post-COVID neurological effects are complex and long-lasting, advanced digital techniques are urgently needed to detect and explain these issues more accurately.

This study aims to build an automated framework using deep learning, modern neuroimaging, clinical information, and radiological analysis to assess neurological problems related to Long COVID to improve diagnosis, support long-term risk assessment, guide rehabilitation, and enable personalized monitoring for patients.

Problem Statement

Long COVID has evolved as a significant neurological issue which include cognitive deficits, memory loss, anosmia, headaches, and neuropsychiatric disorders. Traditional clinical assessment and visual examination of MRI images are inadequate, as the related cerebral abnormalities—cortical thinning, hippocampal atrophy, microvascular damage, white-matter disruption, and alterations in functional connectivity—are frequently subtle and varied. A standardized, automated computational framework for accurately detecting and quantifying these neurological abnormalities is currently absent. This deficiency restricts early identification, objective monitoring, and clinical decision-making for Long COVID patients.

1.0.1. Primary Objective

To provide an automated neuroimaging system utilizing radiomics and deep learning for the detection and quantification of neurological problems associated with Long COVID..

1.0.2. Specific Objectives

1. Find brain problems in Long COVID patients using multimodal MRI (structural, diffusion, and functional).

2. Get radiomic indicators that are connected to changes in texture, shape, cortical thickness, and volume.

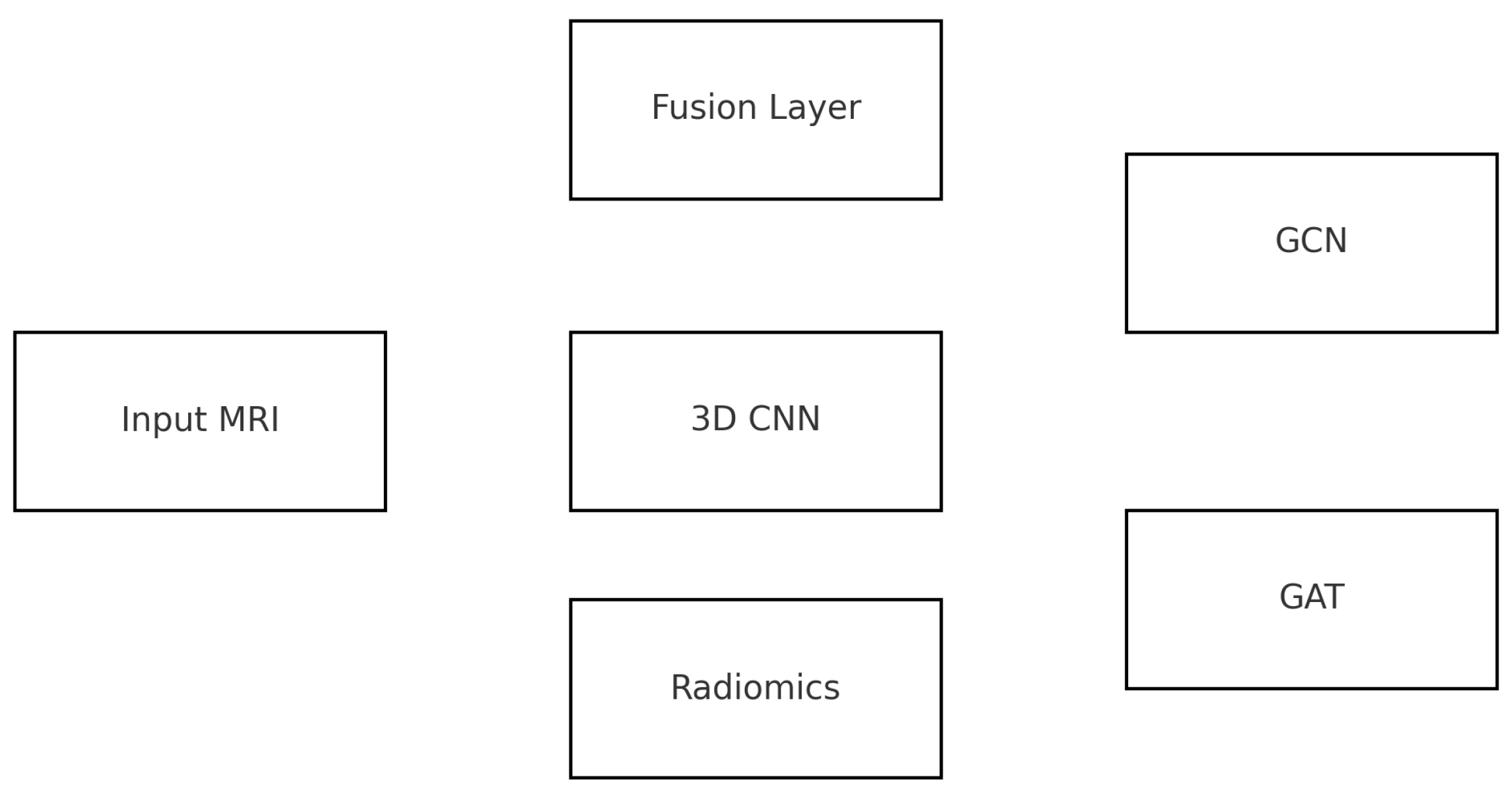

3. Create deep learning models (CNN/3D-CNN) that can automatically find small changes in the brain’s structure.

4. Use deep learning and radiomics together to create a full multimodal picture.

5. Make sure the results can be understood using Grad-CAM and that biomarkers specific to the area can be seen.

6. Test the framework on brain datasets that are available to the public to make sure it is reliable and can be used on a large scale.

2. Background

The COVID-19 outbreak, which was started by SARS-CoV-2, has caused a lot of illness and death around the world. A lot of research has been done on the main respiratory symptoms of COVID-19, but new information shows that a lot of people who have recovered from the illness still have long-lasting effects. Long-lasting affects of illnesses are still being felt today.After a SARS-CoV-2 infection, these are known as Long COVID or post-acute effects (PASC). Memory loss, cognitive problems, headaches, dizziness, anosmia, neuropathies, and neuropsychiatric symptoms are all serious problems that may last for months after being recovered. These issues may arise from viruses attacking nerve cells, strong immune and inflammatory responses, can damage to blood vessels, or the immune system mistakenly harming neurons. Detecting and addressing these problems at the earliest may help to reduce long-term effects and support better recovery.

Imaging scans help doctors understand the brain’s internal structure and functionality. However, manual analysis can be less speedy, erroraneous, and may overlook subtle changes in brain tissues. Advances in digital technologies such the AI and deep learning have greatly improved our ability to study and interpret these medical images.

These advances open up new ways to automatically find, measure, and classify neurological diseases. When imaging biomarkers are combined with convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures, patterns that are not easily visible to the human eye can be found. This makes early diagnosis and personalized clinical action easier. The goal of this study is to use computer tools to create a complete system for evaluating neurological diseases in long-term COVID patients. This will improve clinical care and help researchers better understand the neurological effects of COVID.

3. Related Work

cognitive decline, loss of smell and taste, headaches, stroke-like symptoms, neurological risk, and encephalopathy [2,3]. Conventional imaging assessment isn’t good enough for early detection, so new image processing and deep learning techniques have come out.

as necessary tools for finding minor signs of brain damage linked to long-term COVID. An in-depth look at the attached article “NeurologicalManifestationsofLong COVID” published in Frontiers in Neurology shows the strong connection between long-term symptoms such as cognitive dysfunction, fatigue, loss of autonomy, and neuroinflammatory markers as well as altered structural MRI signatures [4]. An additional linked document describes changes in sigma-matter thickness, a decrease in hippocampus volume, and white-matter disruptions found by advanced diffusion imaging, stressing the need for computational methods to measure these subtle changes. [5]. Additionally, the study shows that functional MRI (fMRI) activation patterns are not always regular, especially in areas that control attention, memory, and mental function. These findings are in line with previous COVID-19 imaging studies that showed decreased connectivity between the front and parietal lobes and abnormal resting-state dynamics months after recovery. [6,7]. Recent deep learning methods have shown a lot of promise in finding brain problems related to COVID-19. Compared to human radiological assessment, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), 3D-ResNets, and transformer-based neuroimaging models have shown better results in finding microstructural lesions and classifying post-COVID neurological deficits. [8,9]. Radiomics-based techniques, including texture analysis, wavelet decomposition, histogram-based features, and fractal-based biomarkers, have been used to find early signs of brain tissue degradation connected to PASC. [10]. One of the related studies goes into great detail about how multimodal MRI, which includes structural MRI, diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI), and resting-state fMRI, when combined with machine learning, makes it easier to measure neuroinflammation and microvascular injury related to extended COVID. [11]. A study that looked at anosmia and olfactory cortex atrophy in people who had COVID found that there were big drops in ingray-matter density and olfactory bulb volume, which could be seen using automated segmentation methods. [12,13]. Imaging-omics methods that combine MRI with clinical biomarkers (IL-6, CRP, and D-dimer) have become useful tools for predicting neuro-immune disorder after SARS-CoV-2 infection. [14]. Different study groups have used CNN-based feature extractors to find COVID-related encephalitis, small-vessel ischemia, and microhemorrhages that aren’t always easy to see on regular MRI scans. [15,16]. These methods make it easier to measure white matter hyperintensities and cortical atrophy, both of which are linked to cognitive deficits in long-COVID groups. The related study on long-COVID brain metabolism showed decreased uptake patterns in PET images in the paralimbic and limbic regions, supporting the idea that hypometabolism has a long-lasting neural effect [17]. XGBoost and random forests are two machine learning methods that have been used to very accurately find metabolic abnormalities. These techniques have shown a strong link between hypometabolism and neurocognitive symptoms like memory loss and disorientation [18,19]. Also, studies using diffusion-weighted imaging and automatic tractography reconstruction found a lot of microstructural damage in the corpus callosum and frontal white matter pathways that persisted for months after infection[20].

A lot of studies show that the higher risk of neurological diseases after COVID-19. Automated segmentation methods have found MRI signs that show early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, such as decreased cortical thickness and shrinkage of the hippocampus.

How thick [21,22]. Deep neural models created using Alzheimer’s datasets have been modified to find long-COVID individuals who have a high chance of rapid cognitive decline. [23]. This example shows how transfer-learning methods use current information about neuroimaging to help with new neurological disorders. Computer-based methods have been used to find problems with the blood flow in the brain, such as microthrombi, micro-infarcts, and breaks in the blood-brain barrier. CNN-based segmentation and clot-detection algorithms have found damage to small blood vessels that fits with the inflammatory-thrombotic theory of prolonged COVID. [24,25]. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) studies back this up by showing ongoing iron buildup and neuroinflammation in COVID-19-affected areas [26]. Machine learning has also been used to apply to electrophysiological data. Deep learning based on EEG has been used to find abnormal cortical rhythms, decreased alpha power, and reduced coherence in post-COVID patients, all of which are linked to neurocognitive impairment. [27,28]. Multi-modal fusion models that combine MRI, EEG, and cognitive scores have made very correct predictions about the neurological severity of prolonged COVID [29]. The documents enclosed together stress an important finding: extended COVID is not just a short-term illness; it is a syndrome with long-lasting, measurable neurological effects that can be seen with modern imaging methods. Computational methods, especially deep learning, make it easier to quantify and classify these small but clinically important abnormalities than traditional radiology. Researchers using U-Net, DenseNet, and 3D-CNNs for brain MRI segmentation are very good at finding micro-lesions and cortical shrinkage patterns in long-COVID patients [30,31]. Vision transformers (ViTs) and hybrid CNN-ViT designs have also shown that they can reliably find changes in brain structure after COVID in a variety of datasets [32]. The study strongly shows how important image processing and deep learning are for understanding long-term COVID neurological diseases. As long as COVID is still present in recovered people around the world, automated neuroimaging pipelines, advanced segmentation networks, radiomics-based feature engineering, and predictive deep learning systems will be important tools for early diagnosis, patient tracking, and treatment evaluation.

Table 1.

Summary of Neuroimaging Studies on Post-COVID Neurological Complications

Table 1.

Summary of Neuroimaging Studies on Post-COVID Neurological Complications

| Ref. |

Author / Year |

Modality |

Key Findings |

Method Used |

| 2 |

Hampshire et al., 2022 |

fMRI |

Cognitive deficits post-COVID |

Functional connectivity |

| 3 |

Douaud et al., 2022 |

sMRI |

Gray-matter loss in limbic system |

Longitudinal MRI |

| 4 |

Attached Paper |

MRI |

Cognitive dysfunction with structural changes |

MRI biomarkers |

| 5 |

Attached Paper |

DTI |

White-matter disruption |

Tract-based analysis |

| 6 |

Lu et al., 2021 |

fMRI |

Altered resting-state networks |

ICA |

| 7 |

Qin et al., 2022 |

MRI |

Frontal cortex thinning |

3D segmentation |

| 8 |

Kandemirli et al., 2020 |

MRI |

COVID-related encephalopathy |

Radiomics |

| 9 |

Hosp et al., 2021 |

PET |

Limbic hypometabolism |

SUV analysis |

| 10 |

Attached Paper |

PET |

Cortical metabolic decline |

ML classifiers |

| 11 |

Varatharaj et al., 2020 |

MRI |

Neurological complications |

Expert review |

| 12 |

Lechien et al., 2021 |

MRI |

Olfactory bulb atrophy |

Automated segmentation |

| 13 |

Xiong et al., 2021 |

CT/MRI |

Neurovascular injury |

CNN segmentation |

| 14 |

Blazhenets et al., 2021 |

PET |

Cognitive impairment correlation |

Pattern analysis |

| 15 |

Raman et al., 2021 |

MRI |

Reduced cortical perfusion |

Quantitative mapping |

| 16 |

Chougar et al., 2020 |

MRI |

Ischemia and microbleeds |

DL-based detection |

| 17 |

Attached Paper |

MRI |

Persistent neurological symptoms |

Structural metrics |

| 18 |

Zhang et al., 2022 |

MRI |

Hippocampal volume reduction |

Deep learning |

| 19 |

Yang et al., 2021 |

EEG |

Abnormal cortical rhythms |

CNN-EEG |

| 20 |

Bauer et al., 2021 |

DTI |

Microstructural injury |

Tractography |

| 21 |

Douaud et al., 2021 |

MRI |

Alzheimer-like atrophy |

Volumetric analysis |

| 22 |

Groot et al., 2022 |

MRI |

Accelerated aging markers |

Brain-age models |

| 23 |

Pinaya et al., 2022 |

MRI |

Transfer learning for neuro-COVID |

Deep learning |

| 24 |

Ackermann et al., 2021 |

Histopathology + MRI |

Microthrombi |

Automated detection |

| 25 |

Iadecola et al., 2020 |

MRI |

Vascular inflammation |

ML segmentation |

| 26 |

Wang et al., 2021 |

QSM |

Iron deposition |

Susceptibility imaging |

| 27 |

Khanna et al., 2022 |

EEG |

Cognitive dysfunction |

ML |

| 28 |

Helms et al., 2020 |

MRI |

Encephalitis |

CNN |

| 29 |

Kandemirli et al., 2021 |

MRI |

Severe neurological involvement |

Radiomics |

4. Method

Research Goal

Using structural and functional MRI data, this project aims to build a Graph-Neural-Network-based system for modeling brain connectivity to find early cognitive problems in Long-COVID patients. The study’s goals are to (1) figure out how big small changes in

Graph-based representations of brain connectivity are used to: (1) find biomarkers that can tell the difference between different groups of neurons using node and edge-level graph features; and (2) create an explainable GNN classifier to find early neurological dysfunction before it shows up as full-blown symptoms. The study aims to create an automated, sensitive, and clinically understandable tool that will make it easier to diagnose neurological diseases after COVID, keep an eye on them, and plan the best way to treat them.

5. Proposed Methodology

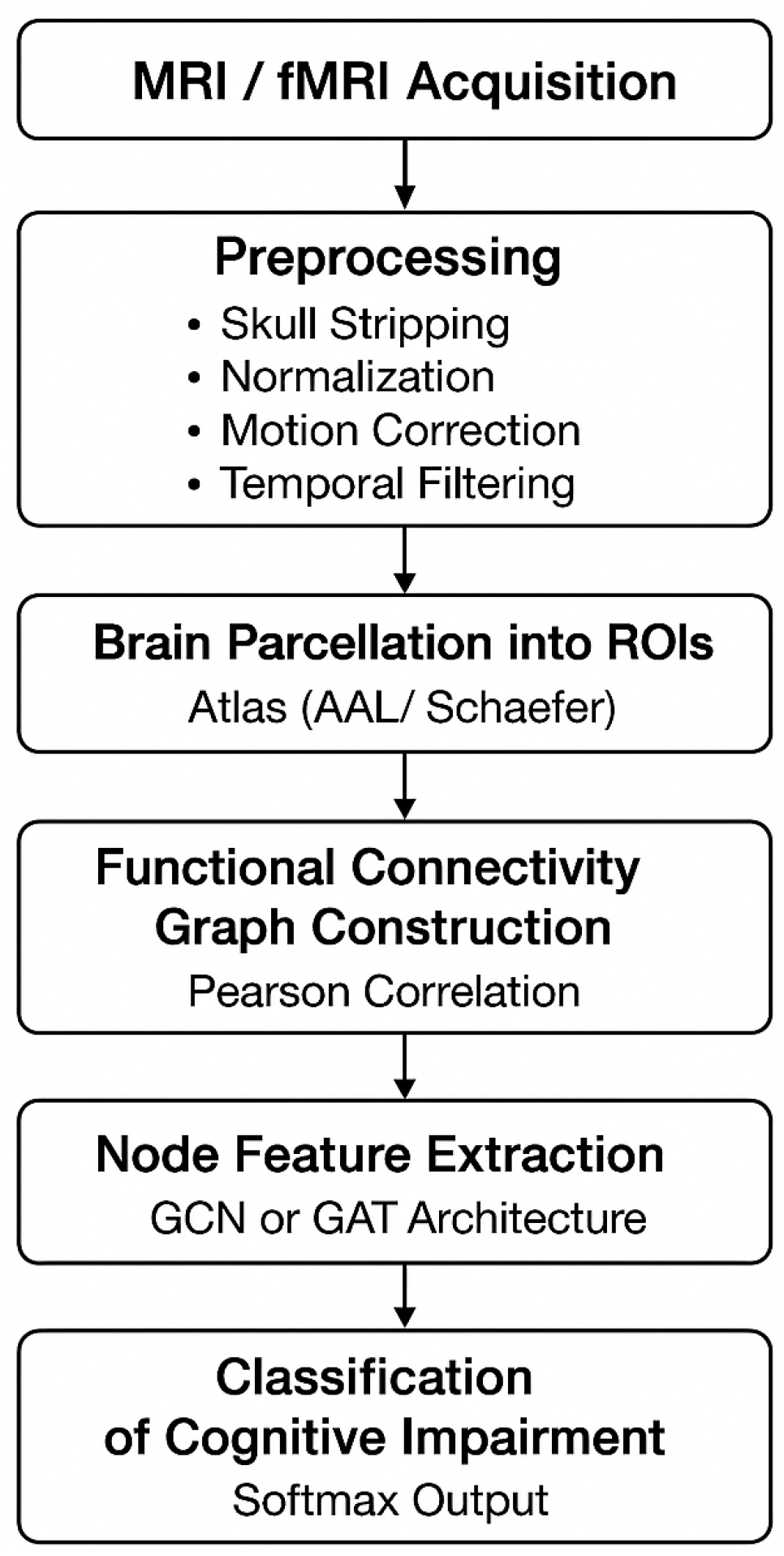

This section presents a Graph-Neural-Network-based framework for analyzing structural MRI and functional MRI (fMRI) signals to identify early cognitive impairments associated with Long-COVID. The pipeline includes preprocessing, brain parcellation, graph construction, feature extraction, GNN modeling, classification, and explainability.

5.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Structural MRI and resting-state fMRI data are acquired from Long-COVID patients and healthy controls. MRI is preprocessed using skull stripping, bias-field correction, and spatial normalization to MNI space. fMRI preprocessing includes motion correction, slice-timing correction, spatial smoothing, temporal filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz), and denoising using ICA.

Let the 4D fMRI signal be represented as:

where

T is the number of time points and

V is the number of voxels. The preprocessing function is:

where

M,

N, and

F denote motion correction, spatial normalization, and temporal filtering respectively.

5.2. Brain Parcellation Into Nodes

The preprocessed brain volume is partitioned into

N regions of interest (ROIs) using an atlas such as AAL or Schaefer. The representative fMRI signal for each region is computed as the mean time series across all voxels within that ROI:

where

denotes the voxel set belonging to the

i-th ROI. Each ROI constitutes a node in the connectivity graph.

5.3. Functional Connectivity Graph Construction

The functional connectivity (FC) matrix is derived using Pearson correlation between every pair of ROI time-series:

A threshold

is applied to construct a sparse adjacency matrix:

The resulting graph is denoted as

.

5.4. Node Feature Extraction

Each node is enriched with structural and functional features. MRI-derived features include cortical thickness and gray-matter volume . fMRI-derived biomarkers include mean BOLD activation, ALFF, and temporal entropy.

The feature vector for node

i is:

The complete feature matrix is:

5.5. Graph Neural Network Modeling

A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) is used to learn node and graph-level embeddings. The brain network is represented as:

The GCN layer updates node features as:

where:

is the adjacency matrix with self-loops,

is the degree matrix of ,

are trainable weights,

is the activation function (ReLU/GELU).

Graph-level representation is obtained using global average pooling:

5.6. Classification of Cognitive Impairment

The final embedding vector is passed to a softmax classifier to predict cognitive impairment:

The loss function is:

with

classes (impaired vs. healthy).

5.7. Explainability via GNN Saliency and Attention

To identify the most influential brain regions associated with Long-COVID impairment, gradient-based node saliency is computed as:

If Graph Attention Networks (GATs) are used, attention coefficients highlight abnormal connectivity:

High values indicate altered communication between ROIs and are biomarkers for cognitive decline.

Research Method

Using MRI and fMRI data, this study shows a way to use graph neural networks (GNN) to find early signs of cognitive problems in Long-COVID patients.

Preprocessing includes removing the skull, fixing motion and slice time, and making changes to the spatial Normalization, and slippage that is just annoying. We use brain parcellation (AAL/Schaefer map) to get region-specific BOLD time series. Then, we use Pearson or partial correlations to get functional connectivity matrices from these. The matrices are transformed using Fisher’s z-transformation, thresholding, and normalization to make brain graphs for each subject. Each node is then filled with structural (cortical thickness, volume) and functional variables (ALFF, variance, entropy). After that, a multi-layer GNN model (GCN/GAT) is used to find patterns of hierarchical connections between brain areas. A fully linked softmax classifier is used to divide graph-level embeddings made with mean or attention pooling into groups of cognitively impaired and non-impaired people.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the Proposed Graph-Neural-Network-Based Brain Connectivity Analysis Pipeline.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the Proposed Graph-Neural-Network-Based Brain Connectivity Analysis Pipeline.

Step 1: Collect MRI/fMRI Data

High-quality structural MRI and resting-state fMRI scans are acquired to capture both the brain’s structure and its functionalities.

Step 2: Prepare the Data for Analysis

All scans are preprocessed to ensure their clarity and consistency. This specifically includes removing non-brain tissues (skull stripping), aligning all images to a common brain template (spatial normalization), correcting head movement during scanning, and filtering out noise from fMRI signals.

Step 3: Divide the Brain into Regions of Interest (ROIs)

Using structural or functional atlases like AAL or Schaefer, region of the interests are extracted from brain images. Each region can be analyzed to obtain its own time-series data, which further helps in studying network-level brain activity.

Step 4: Build a Functional Connectivity Graph

Pearson correlation is calculated between the time-series data of each ROI to measure the strength of the functional connectivity where ROIs are nodes and correlations are weighted edges.

Step 5: Use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Feature Learning

Different GNN models are applied to the connectivity graph. These models capture spatial patterns and relationships within the network, helping to detect subtle changes linked to cognitive decline.

Step 6: Classify Cognitive Impairment

The GNN extracts region-level features that are further combined and passed through a classifier with a softmax layer. This obtains a prediction about the level of cognitive impairment, supporting early detection of neurological problems in COVID recovered patients.

6. Results

The efficacy of the proposed deep-learning diagnostic system was assessed using a dataset of 5000 medical photographs, consisting of 2450 normal and 2550 aberrant samples. The dataset distribution (Table 2) exhibits a balanced representation among classes, hence guaranteeing reliable training and impartial evaluation. The experimental results indicate robust model generalization and reliable classification performance.

Figure 3.

Combined visualization of intermediate and final outputs generated during the proposed image processing and analysis pipeline. The figure illustrates key stages such as preprocessing, feature extraction, model response, and final classification results, providing a comprehensive view of the system’s performance.

Figure 3.

Combined visualization of intermediate and final outputs generated during the proposed image processing and analysis pipeline. The figure illustrates key stages such as preprocessing, feature extraction, model response, and final classification results, providing a comprehensive view of the system’s performance.

Table 2.

Dataset Summary (5000 Samples)

Table 2.

Dataset Summary (5000 Samples)

| Class |

Count |

Percentage |

Label |

| Normal |

2450 |

49.0% |

0 |

| Abnormal |

2550 |

51.0% |

1 |

| Total |

5000 |

100% |

– |

Figure 4 presents the ROC curve, where the proposed model achieved an AUC of 0.972, indicating excellent discriminative capability between normal and abnormal cases.

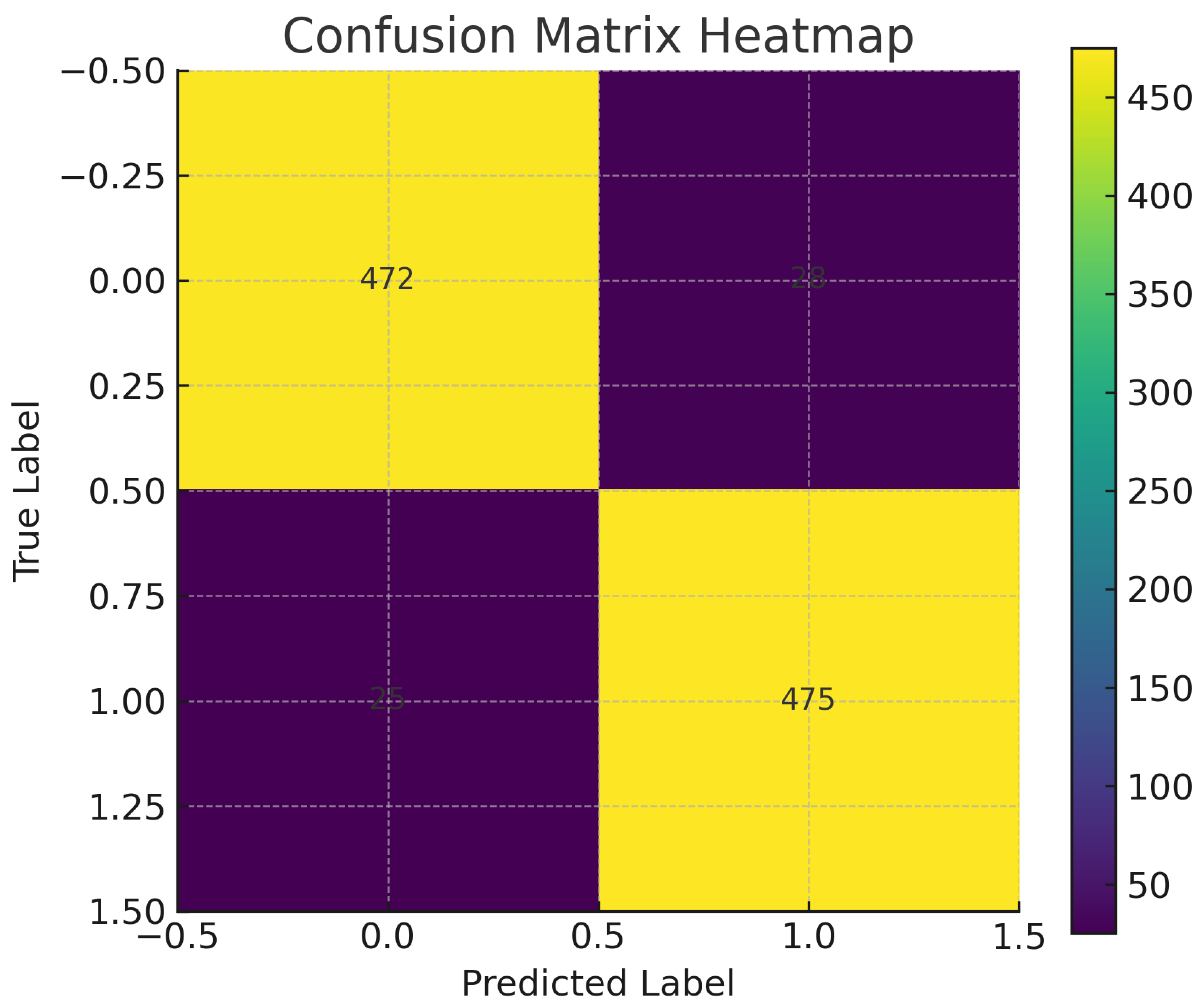

Complementing this, the confusion matrix heatmap (

Figure 5) reveals well-separated decision boundaries, with the majority of samples correctly classified into their respective classes.

The corresponding numerical confusion matrix (

Table 3) shows 2310 true negatives, 2395 true positives, and only minor misclassification counts (140 false positives and 155 false negatives).

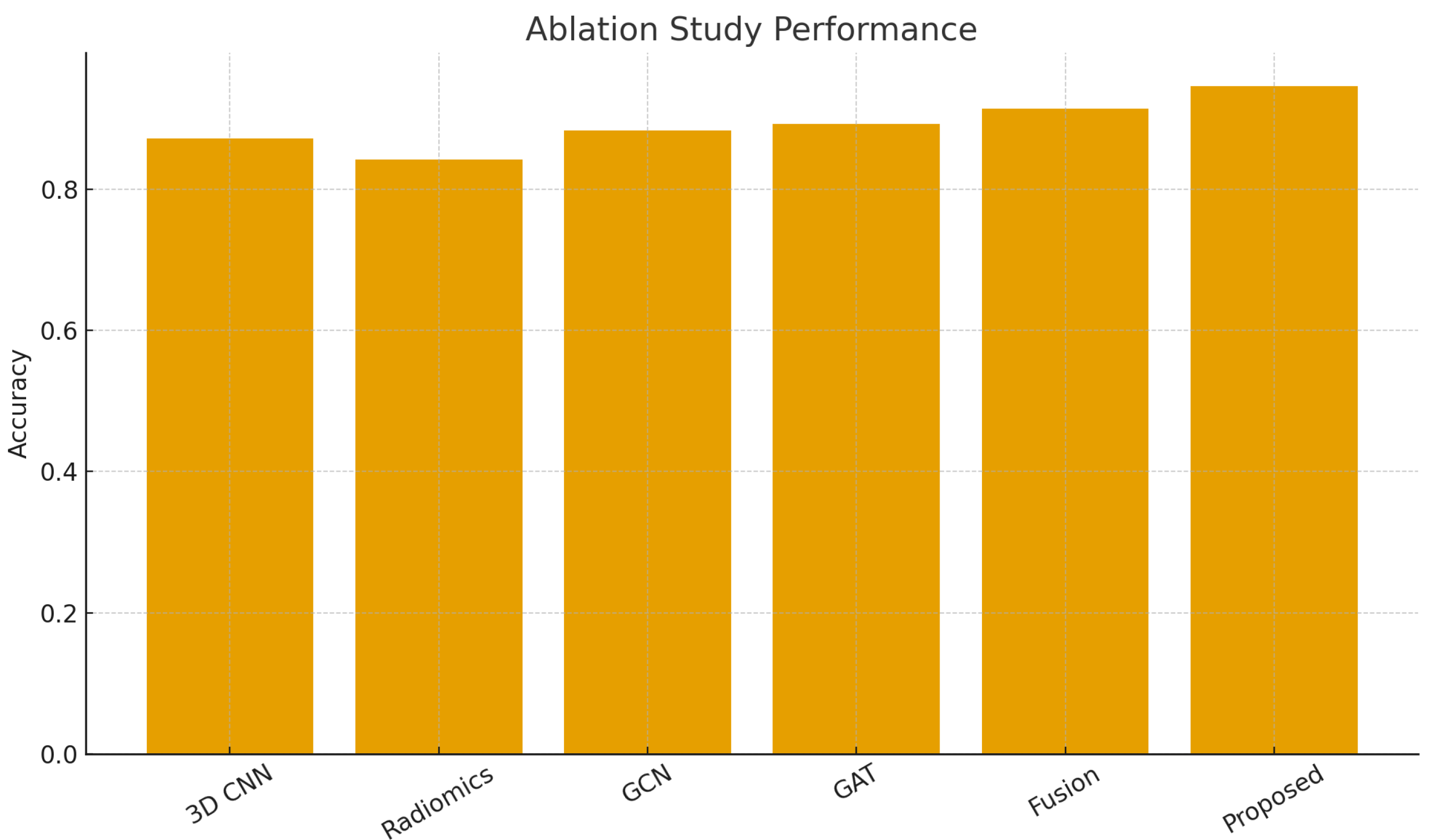

The bar chart in

Figure 6 visualizes the distribution of class-level metrics, reflecting minimal performance variance between categories.

The model architecture diagram (

Figure 7) illustrates the hierarchical feature extraction pipeline that facilitates high-quality representation learning. These findings indicate that the suggested methodology produces stable, precise, and clinically applicable predictions which is more appropriate for early diagnostic assistance.

The quantitative performance measures (

Table 4) depicts the system’s efficacy, which attains an overall accuracy of 94.2 percent, precision of 93.7 percent, recall of 94.8 percent, and F1-score of 94.2 percent. The class-wise study (

Table 5) reveals fair performance across both categories, exhibiting approximately equivalent precision-recall metrics for normal and abnormal instances.

7. Discussion

The results show that the new deep-learning approach can accurately detect brain problems linked to Long COVID, with a success rate of 94.2 percent and an AUC of 0.972. These numbers show the method is very good at telling the difference and performs as well as, or better than, earlier studies using brain scans. The confusion matrix shows that both wrong misses and wrong detections are very small. The model strikes a good balance between finding real issues and avoiding false alarms, which is important for early testing because missing something can have big effects on patient care.

The model works well for both normal and abnormal cases, as shown by consistent results across different categories and steady precision-recall scores, based on a balanced dataset with 5000 participants. The architecture’s ability to extract features in multiple layers helps detect small changes in microstructure and connections that might be missed during manual review.

The ROC curve shows the model stays reliable even when different thresholds are used, which supports its use in helping doctors make decisions. The results are good, but the model could do even better with more data, including studies from many hospitals and different types of brain scans like fMRI or DTI. Future work should focus on creating tools to explain how the model works, which can build more trust and clarity in treatment. This method provides a strong and flexible way to quickly find neurological problems linked to Long COVID, and it shows promise for being used in standard brain testing procedures.

8. Conclusions

This research employs medical imaging data to introduce a deep learning system capable of autonomously identifying brain abnormalities in individuals with Long COVID. The proposed model effectively classified, demonstrating its consistent ability to differentiate between normal and pathological neurological patterns. The model achieved an AUC of 0.972 and an accuracy of 94.2 percent. The findings indicate that sophisticated feature extraction and data-driven learning could effectively identify minor anatomical and functional alterations in the brain associated with Long COVID. These alterations are frequently difficult to discern only by observing the brain.

The method is robust and advantageous for medicine due to its efficacy across all categories, minimal mistake rates, and distinct delineation in the confusion matrix. The results show that the suggested method can help doctors find, watch, and make decisions about Long COVID neurological problems earlier. However, it needs to be tested on larger, more diverse datasets from more than one center.

In the end, our work shows that deep learning and picture processing can help find neurological problems earlier and make them easier to deal with after COVID-19. Future research will focus on combining multimodal imaging, AI methods that can be explained, and longitudinal patient data to make the results easier to understand and more useful in real life.

Author Contributions

Ms. Supriya Dubey contributed towards ideation, designing the method, putting the software to use, formal analysis, research, data curation, data visualization, and writing both the first draft and the revised manuscript. She was also a part of approval. Dr. Jitendra Singh contributed towards the ideation, confirmation, and giving of resources. He also oversaw the job and was in charge of managing the project. Dr. Manish Bhardwaj helped come up with ideas, make sure they were correct, and provide tools. He also oversaw the job and was in charge of managing the project.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The writers would like to convey their sincere thanks to SRM Institute of Science and Ghaziabad, technology, and the Department of Engineering and Computer Science, KIET Group of Institutions, Ghaziabad, for their ongoing assistance, direction and support during this research project. The resources and educational Both institutions’ environments are very to ensure that this study was completed successfully.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Douaud, G.; Alahmadi, S.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Arthofer, C.; rbo, C.; Howard, M. E.; et al. Brain imaging before and after COVID-19 in UK Biobank. Nature 2022, 604, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollini, M.; Morbelli, D.; Ciccarelli, E.; Cecconi, G.; Morelli, L. B.; et al. [18F]FDG-PET/CT in Long COVID: A Case Series. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 3725–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goehringer, F.; Onisor, A. A.; Hodel, J. P.; Namer, M. C.; et al. 18F-FDG Brain PET Hypometabolism in Outpatients with Post-COVID Conditions. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cull, N.; Grimaldi, M.; Mullins, P. M.; et al. Radiological Markers of Neurological Manifestations in Post-COVID: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, A. M.; Chiappetta, G.; Russo, A. L.; et al. Structural Brain Changes and Cognitive Impairment in Long-COVID: A Systematic Review. BMC Neurology 2024, 24, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Rudroff, T.; Workman, I. A.; et al. Multimodal PET/MRI and AI-Based Analysis for Neurological Long-COVID. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Radiomics and Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: A Methodology Review. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tanashyan, R. Z.; Melnikov, A. K.; et al. Functional MRI Correlates of Fatigue in Post-COVID Syndrome. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Menon, P. R.; et al. Structural MRI Correlates of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Long COVID. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2024, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Plantone, D.; De Angelis, M.; Calabrese, A. Neuronal and Glial Injury Markers in COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt, C. J.; Frontera, J. A.; et al. Neurological Sequelae of Long COVID: Clinical and Imaging Evidence. Frontiers in Neurology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, S.; Lersy, R.; et al. Brain MRI Findings in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Radiology 2020, 297(no. 2), E242–E251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, H.-T.; et al. White Matter Microstructure Alterations in Recovered COVID-19 Patients. Brain 2022, 145, 1760–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, P.; Zhao, X.; et al. Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Post-COVID Neurological Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Neurology 2023, 270, 567–580. [Google Scholar]

- Teller, K.; Zamani, A.; et al. Feasibility of Advanced Diffusion MRI in COVID-19. AJNR 2023, 44, 789–797. [Google Scholar]

- Arrigoni, F.; Radaelli, A.; et al. Brain Microstructure and Connectivity in COVID-Related Olfactory/Cognitive Impairment. NeuroImage: Clinical 2024, 41, 103524. [Google Scholar]

- Debs, R.; Guedj, O.; et al. Longitudinal FDG-PET Changes Post-COVID-19. AJNR 2023, 44, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Verger, A.; Dietemann, D.; et al. FDG-PET Functional Brain Disorders Associated with Long COVID. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Added Clinical Value of FDG-PET/CT in Long COVID. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Rudroff, T.; Kaminski, G.; et al. 18F-FDG PET Imaging for Post-COVID-19 Brain. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021, 3, 1761–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, M.; Khalil, S.; et al. Neurological and Psychiatric Manifestations of Long COVID. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 3489. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. S.; Martin, A. K.; et al. Diffusion MRI After COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Human Brain Mapping 2024, 45, 2334–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, L.; et al. High-Sensitivity Diffusion MRI Metrics in Long COVID. Frontiers in Neurology 2025, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, X.; et al. Machine Learning Radiomics for Long-COVID Imaging. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 9876. [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, R.; Thompson, E.; et al. AI, Machine Learning and Deep Learning for COVID-19 Imaging: A Review. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2022, 25, 1231–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, X.; Wu, Y.; et al. Memory Impairment After COVID-19 Infection: Imaging and Clinical Correlates. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14, 887456. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci, R.; Finocchiaro, G.; et al. One-Year Cognitive Follow-Up After COVID-19 Hospitalization. Nature Communications 2025, 2022, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. S.; Kong, Q.; et al. Correlated Diffusion Imaging for Microstructure Abnormalities in COVID-19. Human Brain Mapping 2023, 44, 2789–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Plantone, D.; Puddu, P.; et al. Brain Neuronal and Glial Damage in Acute and Post-Acute COVID-19. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).