1. Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) is a common complication of cancer therapy, affecting up to one third of patients with solid tumours and nearly half of those with haematological malignancies, depending on cancer type and regimen [

1,

2]. According to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, CIT is considered to occur when platelet count falls below 100×10

9/L [

3]. Patients with CIT often require platelet transfusions and are at significant risk of severe bleeding [

1,

4]. CIT increases morbidity, prolongs hospitalisation and, importantly, disrupts anticancer treatment through dose delays or reductions, lowering relative dose intensity (RDI) and potentially compromising survival outcomes [

5]. As anticipated, platelet transfusion is currently the gold standard for managing CIT, particularly in severe cases [

6]. This procedure is costly, resource-intensive, and carries risks such as alloimmunisation [

1,

7]. Despite the prevalence of CIT, no specific therapy beyond platelet transfusion has been approved for its prevention or management.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) are a class of drugs that mimic the action of thrombopoietin to stimulate platelet production. TPO-RAs are currently indicated to treat immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), aplastic anaemia, and liver disease-related thrombocytopenia [

8,

9,

10]. Experience with TPO-RAs in the CIT scenario is limited and predominantly focused on solid tumours (reviewed by Al-Samkari) [

5]. Nevertheless, a recent expert review stated that the current body of evidence strongly supports the use of TPO-RAs for managing persistent CIT [

11].

Avatrombopag (AVA) is the most recently developed TPO-RA. AVA is administered orally and does not have known interactions with foods or drinks. For this reason, its use has been increasing steadily in recent years [

12]. The literature addressing the use of AVA for managing CIT is encouraging but scarce, with reports focusing predominantly on solid tumours [

13,

14,

15]. In the field of haematological malignancy, studies regarding the role of AVA have been conducted in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, post-chemotherapy aplasia, and post-allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), often consisting of case reports or case series with a limited number of patients [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] In any case, the aforementioned studies suggest that AVA presents a favourable efficacy and safety profile for managing CIT. With this background, we sought to share the experience of our centre with AVA used for managing haematological patients with persistent CIT secondary to intensive chemotherapy, allo-HSCT-related and chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy-related procedures. Response to AVA in terms of platelet count recovery, subsequent avoidance of transfusion, maintenance of scheduled chemotherapy, and safety outcomes is reported.

2. Methods

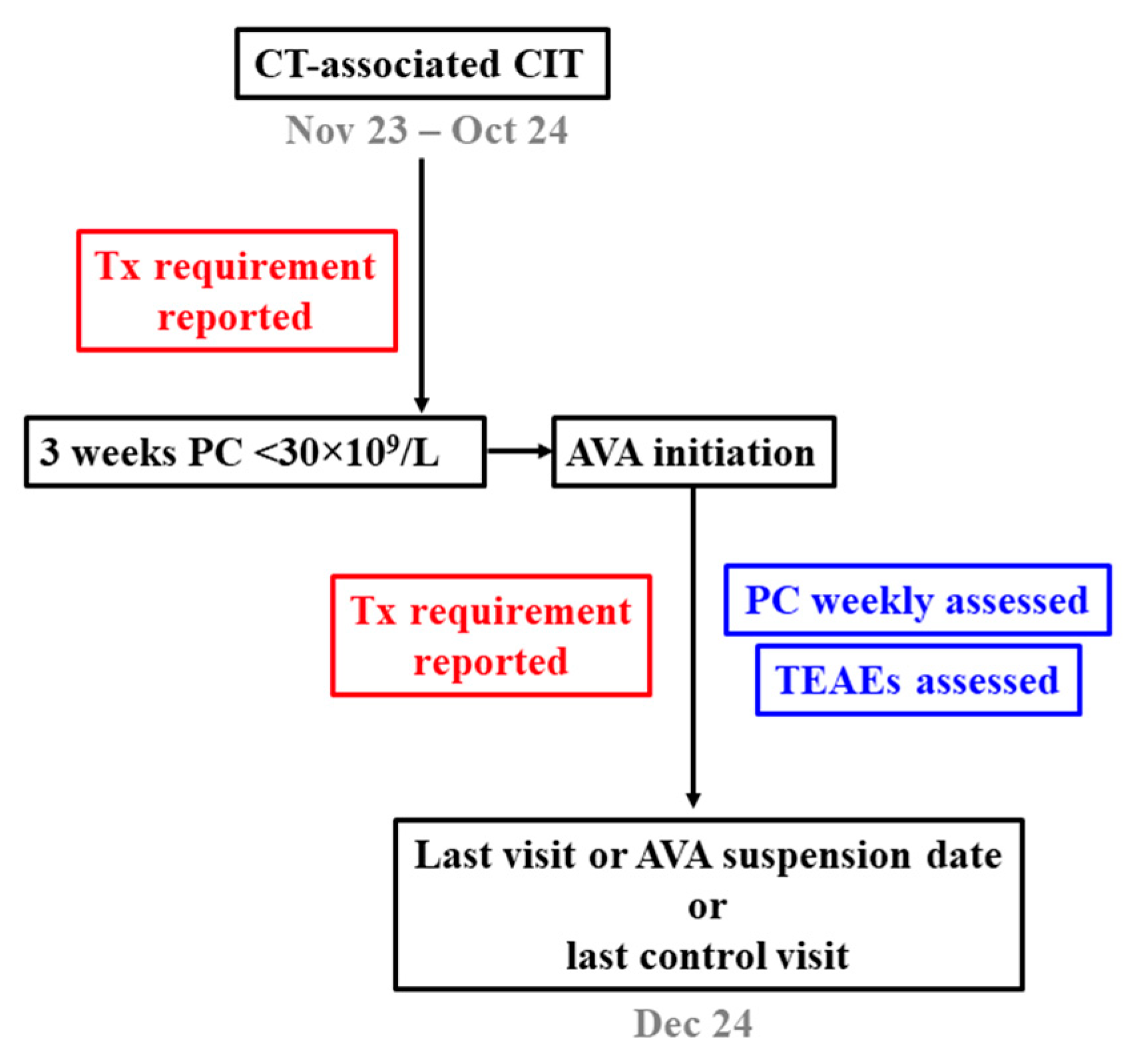

2.1. Patients, Design and Aims of the Study

A retrospective, observational, single-centre study was designed by researchers of the Son Espases University Hospital (Palma de Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain). The different steps are shown in the flowchart diagram (

Figure 1). The primary aims were the comparison of platelet transfusion requirement in oncohaematological patients diagnosed with CIT in the periods before and after starting therapy with AVA, response to AVA in terms of platelet count recovery, and assessment of safety and tolerability while treatment was being administered.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, a diagnosis of haematological cancer regardless of cell lineage, onset of CIT secondary to either intensive chemotherapy or any procedure associated with allo-HSCT or CAR-T cell therapy, persistence of thrombocytopenia for three weeks, and a decision to initiate AVA therapy after this period to restore platelet counts. Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of other disorders known to influence platelet counts, a recent history of cardiovascular disease or arterial or venous thrombosis, and previous exposure to any TPO-RA.

2.3. Treatment, Response Criteria and Safety Assessment

AVA therapy was always initiated at a daily dose of 20 mg. Doses would be escalated to 40 mg/day in the event that platelet counts remained <30×109/L after 14 days. Response was defined as partial (PR) or complete (CR) when platelet counts increased to ≥30×109/L or ≥100×109/L, respectively, with no platelet transfusion requirement for at least 7 days. Platelet counts were monitored for a minimum of one month after the first dose of AVA was administered. In order to assess the safety profile of the treatment, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported while patients remained on AVA therapy. Platelet transfusion requirement was assessed before and after the start of the treatment.

2.4. Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Son Espases University Hospital and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were represented by median (interquartile range [IQR]), and qualitative variables were summarised as numbers and percentages. The two-tailed Wilcoxon test and the two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare paired and unpaired quantitative variables, respectively. The two-tailed Fisher’s exact test and the chi-square test were used to compare dichotomous or polytomous variables, respectively. The two-tailed Spearman’s rho test was used to assess correlations between quantitative and qualitative variables. Statistical significance was established at P <0.05, and GraphPad Prism 5 software was used for calculations.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Features of the Cohort

Patient demographic and baseline characteristics are outlined in

Table 1. Twenty-three patients were recruited between November 2023 and October 2024. Among them, 61% were male, and 48% of the total were diagnosed with lymphoproliferative disorders. Although more than half of the patients received intensive chemotherapy, up to 35% underwent allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. The median (IQR) follow-up period from the onset of CIT to study end was 68 (47–120) days.

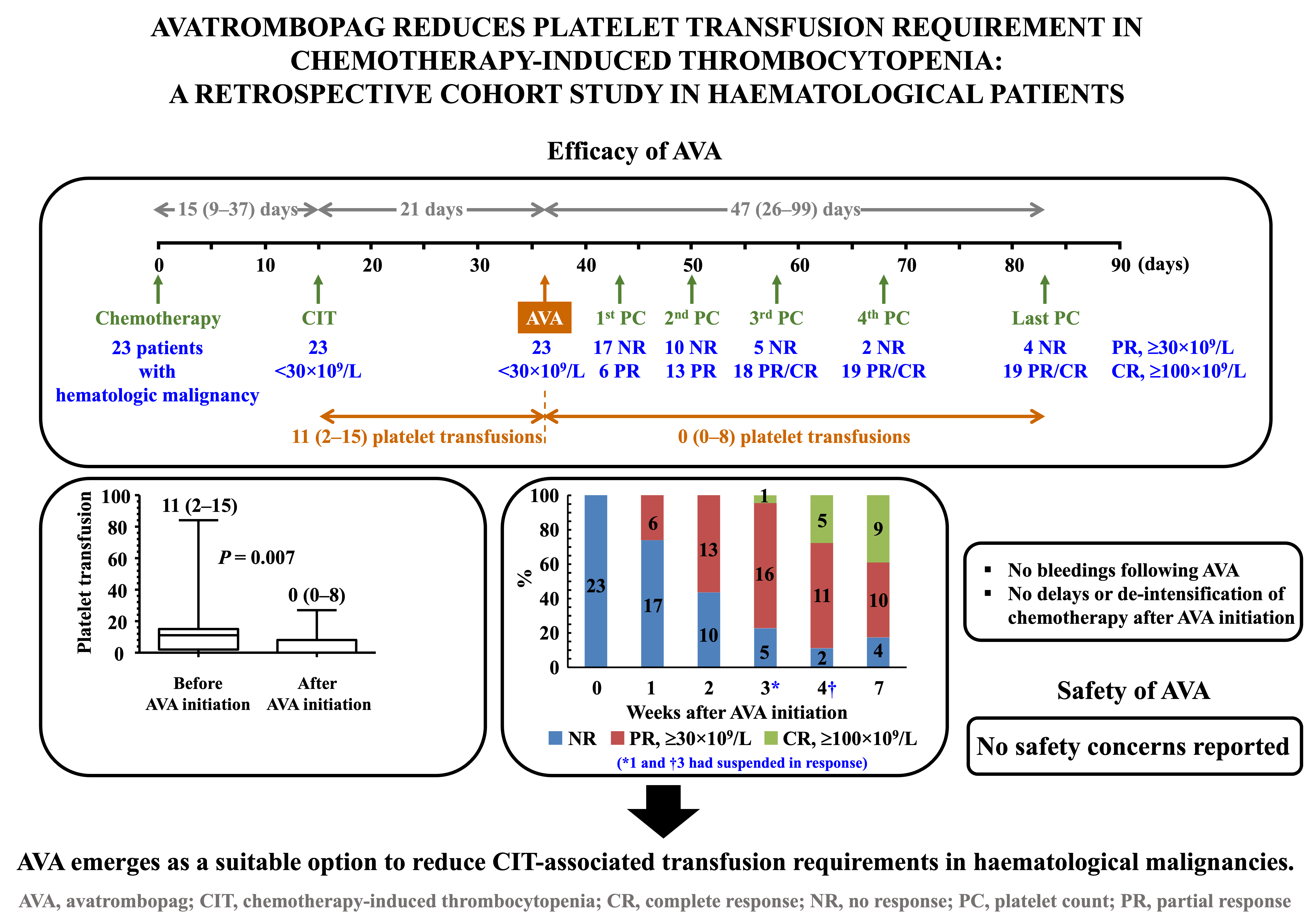

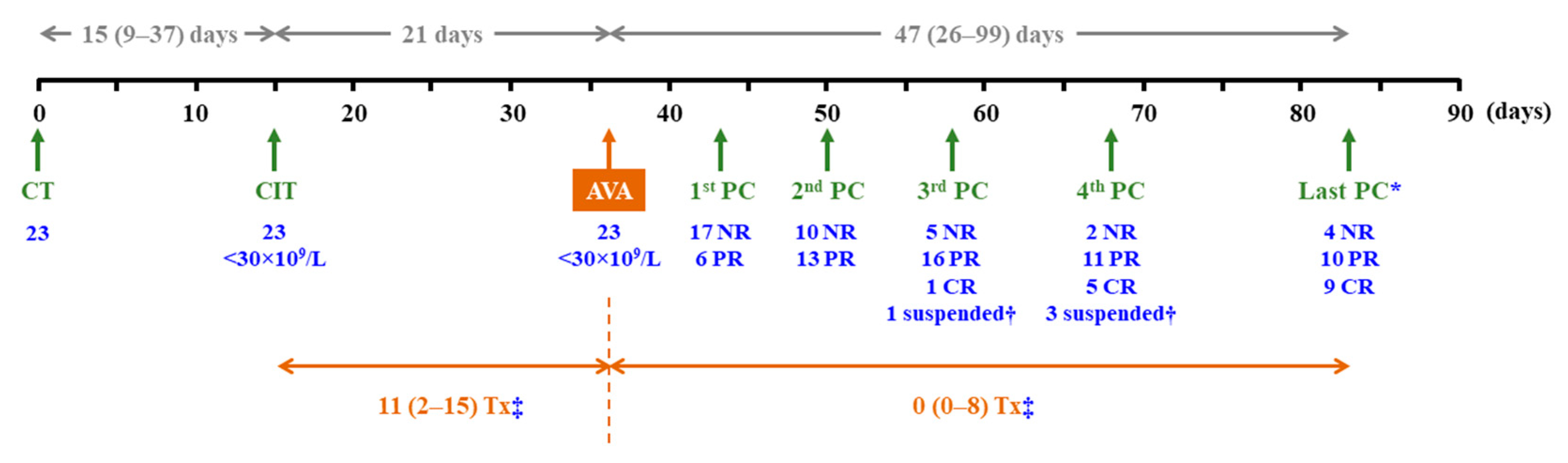

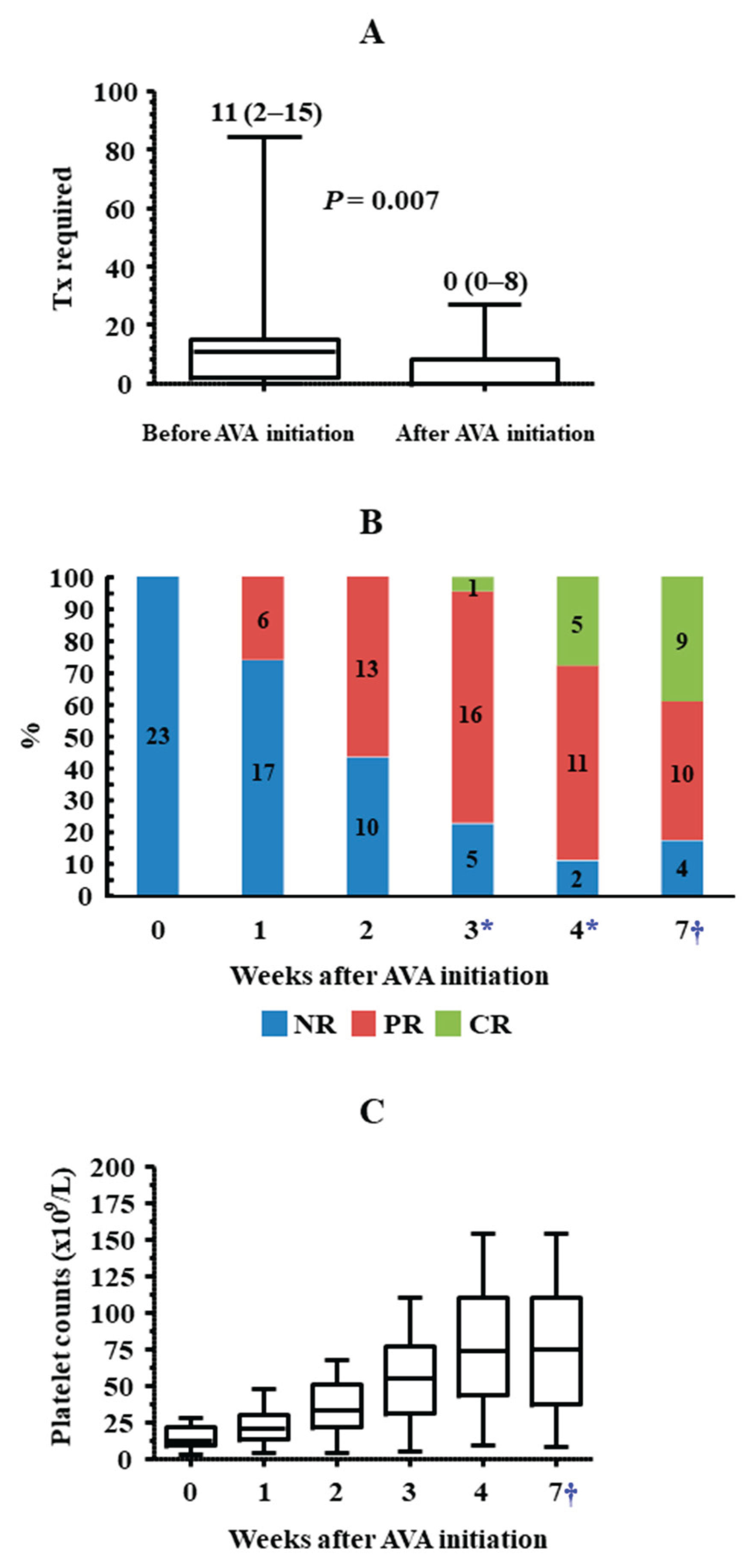

3.2. Time from Onset of Thrombocytopenia to Initiation of AVA Therapy

Figure 2 summarises the main findings of the study. Thrombocytopenia, with platelet counts <30×10

9/L, occurred after a median (IQR) period of 15 (9–37) days following the start of chemotherapy. During the subsequent three weeks, when platelet counts remained persistently <30×10

9/L, the median (IQR) number of platelet transfusions was 11 (2–15) (

Figure 3A). Only 4 out of 23 patients did not receive transfusions during this period, and none experienced bleeding episodes. Up to nine patients presented with haemorrhagic symptoms, most of them mild (cutaneous or gingival bleeding, epistaxis), although two grade 2 upper gastrointestinal bleeding episodes were also reported.

3.3. Efficacy of AVA

Up to 19 out of 23 (82.6%) patients responded to AVA, nine (39.1%) of whom achieved CR. Six (26.1%), twelve (52.2%) and seventeen (73.9%) patients achieved at least PR after 1, 2 and 3 weeks of treatment, respectively. The median (IQR) treatment duration was 47 (26–99) days. AVA had been suspended in seventeen cases by the end of follow-up, with ineffectiveness being the cause of withdrawal in only four patients (17.4%). After a median (IQR) follow-up period of 47 (26–99) days since the initiation of AVA therapy, PR and CR were reported in ten (43.5%) and nine (39.1%) patients, respectively (

Figure 2,

Figure 3B,

Figure S1). In the overall cohort, median platelet counts exceeded 30×10

9/L by the second week after the initiation of AVA therapy and increased progressively until the end of the study (

Figure 3C,

Figure S2).

In the overall cohort, there was a significant inverse correlation between platelet counts immediately before the administration of the first dose of AVA and the number of platelet transfusions required: two-tailed Spearman’s rho = -0.725,

p <0.001. Nevertheless, the number of platelet transfusions required was remarkably and significantly lower once patients started treatment with AVA than in the previous period. The median (IQR) number of transfusions was 0 (0–8), and up to 13 patients never required this procedure, even though this phase lasted more than twice the time from the onset of thrombocytopenia to the first administration of AVA (

Figure 2,

Figure 3A). When stratifying patients according to whether they underwent intensive chemotherapy (n = 12) or allo-HSCT (n = 8), the transfusion requirement since AVA initiation was significantly reduced in both groups (not shown). Finally, when transfusion requirement was studied in those patients who had platelet counts <10×10

9/L when AVA was started (n = 8), a smaller, non-statistically significant decrease was observed upon treatment use [13 (11–24) vs. 10 (2–14) transfusions before and after AVA initiation, respectively,

p = 0.250]. In the overall cohort, no bleeding episodes were reported since AVA was started, except for an intracranial haemorrhage secondary to head trauma, which required 27 platelet transfusions to maintain a safe platelet count threshold.

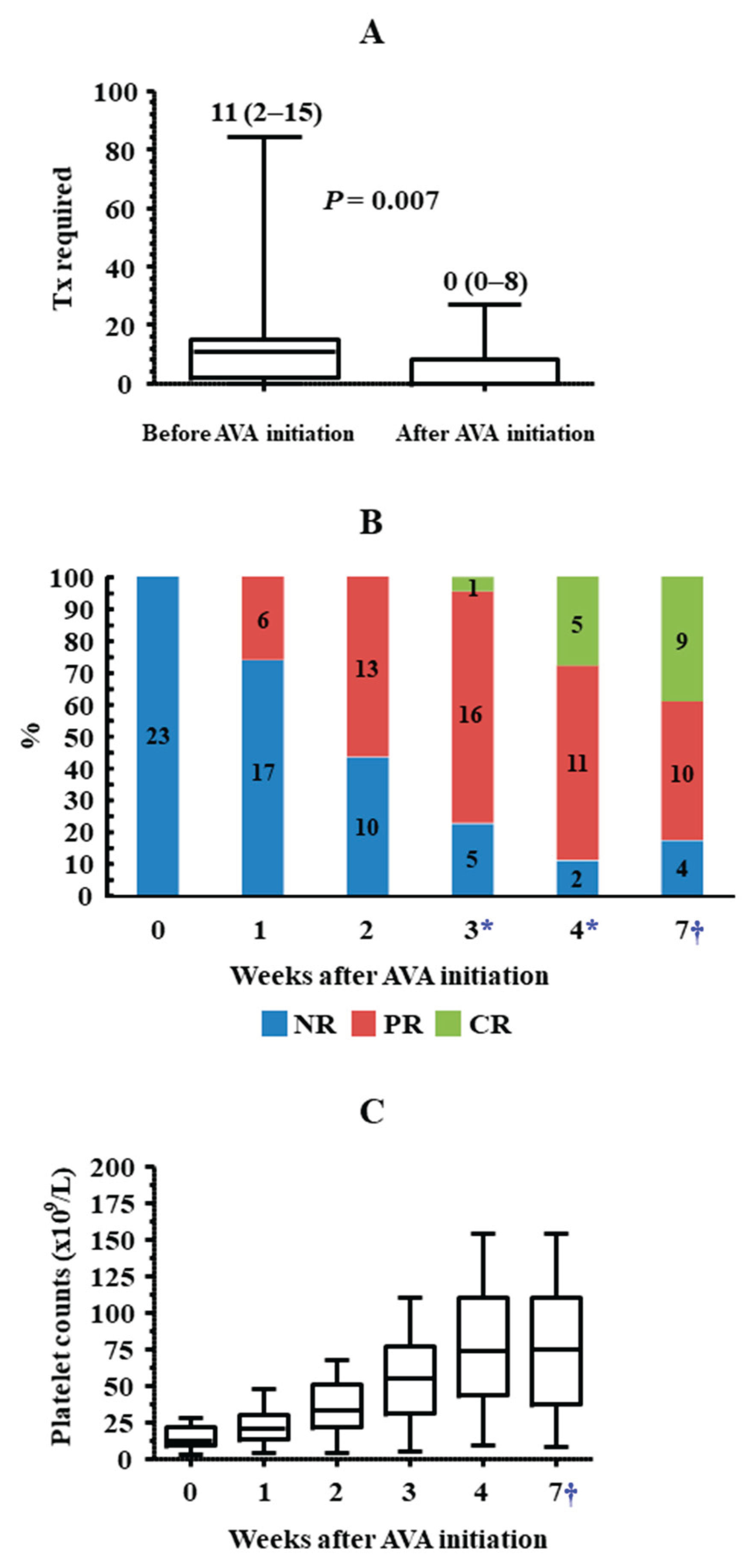

Figure 3.

Transfusions required and platelet counts before and after starting AVA treatment in the overall cohort. (A) Whisker plots show the transfusions required after the onset of CIT, according to whether patients were on AVA treatment or not. The median (IQR) number of transfusions is indicated for each period. (B) Response to AVA treatment in the four weeks after treatment initiation and at the last control visit is shown. (C) Whisker plots show the platelet counts immediately before AVA treatment, in the subsequent weeks, and at the last control visit, which corresponded to definitive AVA suspension in 16 cases. *A total of four patients were excluded from these calculations: one who had suspended AVA by week 3 and three who had suspended AVA by week 4 after treatment initiation because they had responded. †The last platelet count control was performed in the overall cohort. The assessment date corresponded either to the last control visit or to AVA suspension and varied among patients. The median (IQR) time between this date and AVA initiation in the overall cohort was 6.7 (3.7–14.1) weeks.

Figure 3.

Transfusions required and platelet counts before and after starting AVA treatment in the overall cohort. (A) Whisker plots show the transfusions required after the onset of CIT, according to whether patients were on AVA treatment or not. The median (IQR) number of transfusions is indicated for each period. (B) Response to AVA treatment in the four weeks after treatment initiation and at the last control visit is shown. (C) Whisker plots show the platelet counts immediately before AVA treatment, in the subsequent weeks, and at the last control visit, which corresponded to definitive AVA suspension in 16 cases. *A total of four patients were excluded from these calculations: one who had suspended AVA by week 3 and three who had suspended AVA by week 4 after treatment initiation because they had responded. †The last platelet count control was performed in the overall cohort. The assessment date corresponded either to the last control visit or to AVA suspension and varied among patients. The median (IQR) time between this date and AVA initiation in the overall cohort was 6.7 (3.7–14.1) weeks.

Response to AVA was studied in two fragile subgroups, which consisted of patients with either platelet counts <10×10

9/L regardless of bleeding status or platelet counts between 10×10

9/L and 30×10

9/L with bleeding symptoms (

Table 2). In both cases, response (PR or CR) was above 70% and was maintained until the end of the study. Nevertheless, patients with baseline platelet counts <10×10

9/L never reached CR. Conversely, none of those with baseline platelet counts between 10×10

9/L and 30×10

9/L required platelet transfusions.

Finally, response to AVA was compared according to the procedure undergone by patients: intensive chemotherapy (n = 12) or allo-HSCT (n = 8). All patients in the first subgroup and 6 out of 8 in the second responded to treatment. However, only 1 out of 8 (12.5%) patients who underwent allo-HSCT reached CR, whereas 7 out of 12 (58.3%) patients in the first subgroup achieved CR. Accordingly, the number of transfusions required once AVA therapy started was higher in allo-HSCT patients: 2 (0–10) vs. 0 (0–1) in patients receiving chemotherapy (

Table S1).

3.4. AVA Dosing Throughout the Study

The initial avatrombopag dose was established at 20 mg/day in all cases. In the 19 patients who responded to treatment, this dose was sufficient to achieve at least PR in 12 (63.2%) cases. AVA dose was increased to 40 mg/day in eight (34.8%) patients. Nevertheless, the median dose was maintained at 20 mg/day throughout the study (

Table S2).

Regarding AVA doses in the aforementioned fragile subgroups, only 1 of the 5 patients with baseline platelet counts <10×10

9/L who responded to treatment required an increase to 40 mg/day to achieve PR. The remaining responses were obtained with daily doses of 20 mg that were not increased throughout the study. In the five AVA responders who had baseline bleeding symptoms and baseline counts ≥10×10

9/L, the AVA dose of 20 mg/day was sufficient to achieve PR in all patients and CR in three cases. Increasing the AVA dose to 40 mg/day allowed the remaining two patients to reach CR (

Table 2).

3.5. Safety

AVA was well tolerated by all patients, with no occurrence of serious TEAEs, bleeding complications, or thromboembolic events. Only five (21.7%) patients experienced mild TEAEs. All five had asthenia, accompanied by nausea and vomiting in two cases. Twelve (52.2%) patients were managed without the need for hospital admission. Importantly, there was no need to delay anticancer procedures or reduce chemotherapy drug doses.

4. Discussion

Platelet transfusions remain the standard treatment for CIT, but their benefit is transient, with inconsistent platelet recovery and risks of transfusion reactions or refractoriness. Consequently, transfusions are impractical for sustained platelet maintenance and are recommended only for active bleeding or severe thrombocytopenia, with platelet counts < 10×10

9/L [

7]. Thus, the current context of CIT in clinical practice presents significant challenges, and alternative options are urgently required to fill this gap. The use of TPO-RAs for managing CIT is supported by increasing evidence [

21] and, as aforementioned, is encouraged by experts [

11]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis endorse the off-label use of romiplostim, a subcutaneously injected TPO-RA, in selected patients with CIT [

7,

22]. However, the use of oral TPO-RAs in CIT has yet to reach full consensus. Furthermore, experience in haematological malignancy is limited despite its high transfusion burden, and studies focused on AVA are almost unavailable in this field. Our findings are in line with those reported by others when AVA was used for managing CIT secondary to allo-HSCT or chemotherapy in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. More than 80% of patients achieved platelet counts of at least ≥30×10

9/L, half of them by the second week of treatment and most by the third week. Although the AVA dose was occasionally increased to 40 mg/day, the median dose was 20 mg/day throughout the study, thus not higher than the initial dose recommended for managing ITP [

23]. Response was maintained during a median follow-up period of 47 days, after which roughly 40% of patients maintained CR. Although response appeared slightly better in patients undergoing chemotherapy than in those receiving allo-HSCT, 75% of the latter had platelet counts ≥30×10

9/L at the end of the study.

Importantly, the number of transfusions required since AVA initiation was markedly lower, both in the overall cohort and when patients were grouped according to whether they underwent intensive chemotherapy, allo-HSCT, or CAR-T cell therapy. More than half of the patients did not require platelet transfusion support throughout the treatment period, which means that AVA can be a useful tool to reduce transfusion burden and thereby mitigate transfusion-related risks while lowering healthcare costs [

1,

7]. Although results regarding transfusion requirement while on AVA treatment were less unequivocal in patients with platelet counts <10×10

9/L at the time the first dose of the TPO-RA was administered, the median number of transfusions in this subgroup was ten over a median follow-up of 59 days of therapy. The exact number of transfusions required to maintain platelet counts above 10×10

9/L depends on the severity of bone-marrow suppression and other individual hallmarks, but it may increase up to eight per chemotherapy cycle [

24,

25,

26]. Therefore, AVA may also be useful for this purpose in severe conditions. Conversely, most patients with bleeding symptoms and platelet counts ≥10×10

9/L at AVA initiation did not require platelet transfusions thereafter. It must be remarked that no bleeding episodes were reported in the overall cohort while on AVA and, when applicable, in the post-AVA period.

No safety concerns were reported in any patients while on AVA treatment. Thromboembolic events (TEVs) have been described occasionally in ITP patients treated with TPO-Ras [

27]. No TEVs were documented in our cohort or in previous studies addressing the role of AVA in CIT in haematological malignancy [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Nevertheless, studies covering longer treatment periods are required to assess long-term safety more accurately.

Our study has limitations. The heterogeneity of haematological diseases and the size of the cohort preclude drawing robust conclusions, as well as focusing on chemotherapy procedures or specific pathologies. The duration of the study does not allow assessment of the long-term effectiveness of AVA and, therefore, whether it can be useful for chemotherapy programmes of longer duration or for long-term management of thrombocytopenia in the context of allo-HSCT or CAR-T cell therapy, where prolonged thrombocytopenia has been described [

28,

29]. Platelet transfusions may have occasionally influenced platelet counts. Nevertheless, the number of transfusions, and therefore the risk of overestimating counts, was markedly higher in the pre-AVA period.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study supports the notion that AVA may serve as a safe and effective treatment option for managing persistent CIT in haematological patients. AVA appears to increase platelet counts and lessen the need for transfusions, potentially lowering bleeding risks, shortening hospital stays, and reducing costs. Additional research is needed to confirm these findings in specific conditions and to establish optimal treatment durations and dosing regimens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

AAC and MC designed the study, provided patients and wrote the paper. ML and APa managed access to chemotherapy drugs and avatrombopag and reviewed critically the manuscript. MJ, SP, LGM, JMS, LB, AN, APe, CB, AG, GP, BG and AS provided patients and reviewed critically the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Son Espases University Hospital.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to corresponding author.

Novelty Statement: We present the experience of our hospital regarding the use of Avatrombopag (AVA) to treat chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) in haematological malignancy. Our results are encouraging enough to stimulate others to further explore the role of AVA in the management of CIT in haematological malignancy, with the ultimate aim of finding a safe alternative to platelet transfusion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Allo-HSCT |

Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| AVA |

Avatrombopag |

| CAR-T |

Chimeric antigen receptor T |

| CIT |

Chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia |

| CR |

Complete response |

| CT |

Chemotherapy |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| ITP |

Immune thrombocytopenia |

| NR |

No response |

| PC |

Platelet counts |

| PLT |

Platelets |

| PR |

Partial response |

| RDI |

Relative dose intensity |

| TEAEs |

Treatment-emergent adverse events |

| TEVs |

Thromboembolic events |

| TPO-RAs |

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists |

| Tx |

Transfusion |

References

- Kuter, D.J. Managing thrombocytopenia associated with cancer chemotherapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 2015, 29, 282–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, D. Chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia: literature review. Discov Oncol. 2023, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version, 5.0, Published: November 27 2017, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/. 23th October 2025. Available online: https://dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-5x7.pdf.

- Al-Samkari, H.; Soff, G.A. Clinical challenges and promising therapies for chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2021, 14, 437–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Samkari, H. Optimal management of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia with thrombopoietin receptor agonists. Blood Rev. 2024, 63, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Stanworth, S.J.; Murphy, M.F. Different Platelet Count Thresholds to Guide Use of Prophylactic Platelet Transfusions for Patients With Hematological Disorders After Myelosuppressive Chemotherapy or Stem Cell Transplantation. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1091–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soff, G.; Leader, A.; Al-Samkari, H.; Falanga, A.; Maraveyas, A.; Sanfilippo, K.; et al. Management of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia: guidance from the ISTH Subcommittee on Hemostasis and Malignancy. J Thromb Haemost. 2024, 22, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.B.; Al-Samkari, H. Emerging data on thrombopoietin receptor agonists for management of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2023, 16, 373–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. Avatrombopag: first global approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1163–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cai, R. Avatrombopag for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic liver disease. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2019, 12, 859–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H. Should thrombopoietin receptor agonists be used for chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia? Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2025, 9, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, A. Avatrombopag: A Review in Thrombocytopenia. Drugs 2021, 81, 1905–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H.; Kolb-Sielecki, J.; Safina, S.Z.; Xue, X.; Jamieson, B.D. Avatrombopag for chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia in patients with non-haematological malignancies: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e179-89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; Shao, K.; Ye, B.; et al. Effect of avatrombopag in the management of severe and refractory chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia (CIT) in patients with solid tumors. Platelets 2022, 33, 1024–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galamaga, R.; Johnson, S.; Acosta, C. Avatrombopag for the treatment of patients with chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia: a case series. Br J Haematol. 2025, 206, 272–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, J.; Kong, P.; Gao, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; et al. Analysis of the efficacy and safety of avatrombopag combined with MSCs for the treatment of thrombocytopenia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 910893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Cao, W.; Luo, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Avatrombopag for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in children’s patients following allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a pilot study. Front Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1099372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Qi, J.; Gu, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; et al. Avatrombopag for the treatment of thrombocytopenia post hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022, 13, 20406207221127532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Gao, J.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fang, R.; Zhang, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Avatrombopag in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a single-center retrospective study. Ther Adv Hematol. 2024, 15, 20406207241304300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, E.J.; Citta, A.; Alford, C.; Ligon, J.A.; Dalal, M.; Castillo, P.; et al. Avatrombopag for severe refractory thrombocytopenia in a pediatric patient with ALL following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a case report. Leuk Res Rep. 2024, 22, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumurthy, G.; Kisiel, F.; Gurumurthy, S.; Gurumurthy, J. Role of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia: A meta-analysis. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2025, 31, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Hematopoietic Growth Factors. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2022. 2022. 24th October 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/growthfactors.pdf.

- Labanca, C.; Vigna, E.; Martino, E.A.; Bruzzese, A.; Mendicino, F.; Caridà, G.; et al. Avatrombopag for the Treatment of Immune Thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol. 2025, 114, 733–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Stanworth, S.; Doree, C.; Trivella, M.; Hopewell, S.; Blanco, P.; et al. Different doses of prophylactic platelet transfusion for preventing bleeding in people with haematological disorders after myelosuppressive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 2015, CD010984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodnough, L.T.; Levy, J.H.; Murphy, M.F. Concepts of blood transfusion in adults. Lancet 2013, 381, 1845–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, R.A.; Nahirniak, S.; Guyatt, G.; Bathla, A.; White, S.K.; Al-Riyami, A.Z.; et al. Platelet Transfusion: 2025 AABB and ICTMG International Clinical Practice Guidelines. JAMA 2025, 334, 606–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liao, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yu, L. Relationship between thromboembolic events and thrombopoietin receptor agonists: a pharmacovigilance analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System and the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report. BMJ Open. 2025, 15, e099153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, A.; Karimizadeh, Z.; Jafari, L.; Behfar, M.; Hamidieh, A.A. Thrombocytopenia after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Pediatrics and Adults: A Narrative Review Including Etiology, Management, Monitoring, and Novel Therapies. In Semin Thromb Hemost; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, S.J.; Murphree, C.; Raess, P.W.; Schachter, L.; Chen, A.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; et al. Prolonged hematologic toxicity following treatment with chimeric antigen receptor T cells in patients with hematologic malignancies. Am J Hematol. 2021, 96, 455–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).